Abstract

Background

Biotinidase deficiency (BD) is an autosomal recessively inherited disorder of biotin recycling. It is classified into two levels based on the biotinidase enzyme activity: partial deficiency (10%–30% enzyme activity) and profound deficiency (0%–10% enzyme activity). The aims of this study were to evaluate our patients with BD, identify the spectrum of biotinidase (BTD) gene mutations in Turkish patients and to determine the clinical and laboratory findings of our patients and their follow-up period.

Methods

A total of 259 patients who were diagnosed with BD were enrolled in the study. One hundred and forty-eight patients were male (57.1%), and 111 patients were female (42.9%).

Results

The number of patients detected by newborn screening was 221 (85.3%). By family screening, 31 (12%) patients were diagnosed with BD. Seven patients (2.7%) had different initial complaints and were diagnosed with BD. Partial BD was detected in 186 (71.8%) patients, and the profound deficiency was detected in 73 (28.2%) patients. Most of our patients were asymptomatic. The most commonly found variants were p.D444H, p.R157H, c.98_104delinsTCC. The novel mutations which were detected in this study are p.D401N(c.1201G>A), p.A82G (c.245C>G), p.F128S(c.383T>C), c617_619del/TTG (p.Val207del), p.A287T(c.859G>A), p.S491H(c.1471A>G). The most common mutation was p.R157H in profound BD and p.D444H in partial BD. All diagnosed patients were treated with biotin.

Conclusions

The diagnosis of BD should be based on plasma biotinidase activity and molecular analysis. We determined the clinical and genetic spectra of a large group of patients with BD from Western Turkey. The frequent mutations in our study were similar to the literature. In this study, six novel mutations were described.

Introduction

Biotin is a water-soluble vitamin that plays an essential role in carboxylation reactions. It is a cofactor for pyruvate carboxylase, propionyl-CoA carboxylase, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase and two of the isoforms of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC-1 and ACC-2) that have a role in amino acid catabolism, gluconeogenesis, tricarboxylic acid cycle and fatty acid synthesis [1], [2]. Biotinidase (EC 3.5.1.12) is the enzyme that recycles the vitamin biotin [3], [4].

Biotinidase deficiency (BD) (OMIM 253260), the major cause of late-onset biotin-responsive multiple carboxylase deficiency is an autosomal recessively inherited disorder [5], [6]. Individuals with profound deficiency have less than 10% of mean normal biotinidase activity, whereas those with partial BD have between 10% and 30% mean normal enzyme activity [7]. The symptoms of the disorder can be successfully treated or prevented by administering pharmacological doses of biotin [7].

The clinical features of the symptomatic children with profound BD include hypotonia, lethargy, seizures, ataxia, optic atrophy, hearing loss and cognitive deficits, which if untreated can progress to coma or death. The cutaneous findings include eczematous skin rash, alopecia and conjunctivitis. If optic atrophy, hearing loss and cognitive deficits develope, they are generally irreversible. Respiratory problems, such as hyperventilation, laryngeal stridor and apnea can occur. Also, untreated patients with BD can develop lactic acidosis, ketosis and hyperammonemia. Patients with untreated partial deficiency may have milder symptoms [7]. The first newborn screening for BD was started in Virginia in 1984 [8]. The patients with BD who are treated with biotin before they have developed symptoms, appear to have normal development [7].

The gene for biotinidase is located on chromosome 3q25 [9]. The human BTD gene contains four exons with sizes 79 bp, 265 bp, 150 bp and 1502 bp [10]. By sequencing of the BTD gene over 150 different mutations have been identified [11].

The aims of this study were to evaluate our patients with BD, identify the spectrum of BTD gene mutations in Turkish patients and to determine the clinical and laboratory findings of our patients and their follow-up.

Materials and methods

All patients with BD followed at the Ege University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Metabolism and Nutrition were enrolled in this study. The patients who were diagnosed with BD from the National Newborn Screening Program or family screening or referred to the outpatient clinic due to symptoms were recorded. The diagnosis is confirmed by enzyme activity and BTD gene analysis for all patients. Detailed clinical and laboratory findings (such as blood gas, lactic acid, urine organic acid analysis and spot blood carnitine profiles) were recorded.

Biotinidase activity measurement

In order to confirm the diagnosis of BD, all patients’ serum biotinidase activity was determined quantitatively at the Ege University Faculty of Medicine, Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory by the colorimetric method (reference: 4.4–12 nmol/min/mL). The method uses biotinyl-p-aminobenzoic acid (B-PABA) as substrate. Biotinidase in serum cleaves the amide bond of B-PABA forming free biotin and p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA). The released PABA is then converted to a purple azo dye and quantitated spectrophotometrically at 546 nm. Enzyme activity is expressed as the released PABA in nmol⋅min−1⋅mL−1 of serum and % of mean normal serum activity. To test for the presence of interfering substances a substrate-free blank and also a positive control was included with each set of reference individuals’ samples [6], [12]. All patients’ enzyme activity had been measured at least twice.

Molecular analysis

Biotinidase mutation analysis was performed by sequencing of the coding exons and the exon-intron boundaries of the genes. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood cells with a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (cat# 51104 QIAGEN, Germantown, MA, USA) according to the protocol provided with the kit. To amplify the exons, BTD gene primers were used as listed in Table 1. Sequencing was performed with Sanger sequencing or next generation sequencing (NGS). In Sanger sequencing, polymerase chain reaction products were sequenced by the dye termination method using a DNA sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Foster, CA, USA) and analyzed using the ABI Prism 3100 sequence analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA). The NGS sequencing was performed with a MiSeq Reagent Kits v2 on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, Foster, CA, USA). The analysis was performed with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software using BTD transcript NM_000060. IGV is freely available at https://www.igv.org.

Diagnostic details of the patients with BD.

| Diagnosed by | Number of patients | Female/male | Mean±SD Age, years (min-max) | Mean±SD Age at diagnosis (min-max) (months) | Mean±SD Biotinidase enzyme levels, nmol/dk/mL (min-max)a % activity (min-max) | Patients with partial BD | Patients with profound BD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn screening | 221 | 90/131 | 3.50±2.58 (4 months– 11.5 years) | 1.20±0.60 (0.4–5) | 1.23±0.66 (0.04–3.0) 16.73±8.85 (1–42) | 162 | 59 |

| Family screening | 31 | 17/14 | 15.63±9.52 (4–43) years | 136.50±136.00 (0.5–516) | 1.15±0.72 (0.05–2.96) 16.12±10.23 (1–42) | 20 | 11 |

| Symptomatic | 7 | 4/3 | 13.52±6.90 (6–25) years | 115.00±96.90 (4–252) | 1.19±0.93 (0.08–2.73) 16.85±13.00 (1–38) | 4 | 3 |

aReference: 4.4–12.

Primers used for the sequencing of the coding region of BTD gene were;

BTD-1F TGCAAAGCAGGTAAGAAGCC

BTD-1R CGCCCTTACCACACCCCCTC

BTD-2F GCAGGATTCTTTATTCAGCTG

BTD-2R GCAATCTGCTCTGTATGAGAG

BTD-3F CCTGCCATCTGATAACAGAC

BTD-3R CTGACTTAGATCACCTCTGTG

BTD-4AF TCAATCTCCTGACCTCATG

BTD-4AR GGTTCCATTATTGCTGAACACGAC

BTD-4BF CAGTTCAACACAAATGTC

BTD-4BR CATGCTTCACCTTGTAGTCTC

BTD-4CF GAGACTACAAGGTGAAGCATG

BTD-4CR GGTCCGTTTCACCTGTTGCA

BTD-4DF AACGGACCCATCCCATAGT

BTD-4DR GTAAGTGCCATGTACTGT

BTD-4EF CACAGTACATGGCACTTAC

BTD-4ER TCAACATGATGGCCAGAGTC

A total of 259 patients with low enzyme activity and/or with mutations (in two alleles) BTD gene analysis, were enrolled in the study. The patients with low enzyme activity were measured in nmol/min/mL (lower than 4.4) and pathogenic mutations in the BTD gene were enrolled in the study even if enzyme activity is greater than 30%. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Ege University Faculty of Medicine.

Results

In this study total, 259 patients with BD were evaluated for their clinical, laboratory findings and BTD gene analysis. One hundred and forty-eight patients were male (57.1%), and 111 patients were female (42.9%). The number of patients detected by newborn screening was 221 (85.3%). By family screening, 31 (12%) patients were diagnosed with BD. Seven patients (2.7%) had different initial complaints and were diagnosed with BD. Partial BD was detected in 186 (71.8%) patients, and the profound deficiency was detected in 73 (28.2%) patients. Details of the patients during diagnostic approach are given in Table 1.

The consanguinity rate (86 patients, 33.2%) was high in our study. We detected 31 patients with BD by family screening. Twenty of these patients had partial BD, 11 patients had a profound deficiency. Fifteen of them were parents (six profound BD, nine partial BD) of the index cases. One mother complained about hair loss and the rest of them were asymptomatic. Sixty-nine (26.6%) patients had relatives with BD deficiency. Patient 232 who had profound deficiency had six relatives (parents and four siblings) with profound deficiency. They all had homozygote p.R157H mutations.

Most of our patients (95.6%) were asymptomatic. In total 12 patients (4.6%) had clinical symptoms. Four of them were diagnosed by newborn screening, one of them was diagnosed by family screening. Ketoacidosis was detected in three patients. Hypoglycemia was observed in two patients. Two patients had hearing loss at the time of diagnosis. Patient 192, diagnosed by newborn screening at the age of 17 days, had hearing loss. He was also under investigation for inherited hearing loss disorder. Late-onset BD was detected in one patient, and the case was reported in the literature by Yilmaz et al. [13]. A 14-year-old boy presented with progressive vision loss and upper limb weakness. Steroid therapy was initiated with a preliminary diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder due to the craniospinal imaging findings demonstrating optic nerve, brainstem and longitudinally extensive spinal cord involvement. He had profound BD and BTD gene analysis revealed c.98-104delinsTCC/p.V457M and complete regression detected after biotin therapy. By family screening, his brother was diagnosed with profound BD and was treated with biotin. One patient had autism spectrum disorder and was diagnosed with partial BD. One patient with partial BD with homozygous pD44H mutation visited our department due to a tic disorder. A 19-year-old girl was diagnosed with partial BD at the age of 16 years. She had recurrent hypoglycemia and ketoacidosis attacks. Her biotinidase enzyme level was 1.1 nmol/mL/min (15.5%). Biotinidase gene analysis revealed c.98-104delinsTCC/p.D444H mutation and after biotin therapy, she had no hypoglycemia nor ketoacidosis attacks. Details of the symptomatic patients are given in Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory findings of the symptomatic patients with BD.

| Patient no (sex) | Age (age at diagnosis) | Consanguinity | Clinical findings | Enzyme levels, nmol/dk/mLc (% activity) | BTD gene analysis | Biotine dose, mg/day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (F)a | 25 years (3 months) | First degree cousin | Ketoacidosis | 0.05 (1) | NA | 20 |

| 2 (M) | 10 years (2 years) | First degree cousin | Motor mental retardation | 0.40 (6) | NA | 20 |

| 4 (M) | 15 years (14 years) | First degree cousin | Neuromyelitis optica | 0.55 (8) | c.98-104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) p.V457M(c.1369G>A) | 20 |

| 7 (M) | 12.5 years (2.5 months) | Absent | Seziure, hypoglycemia, ketoacidosis, dermatitis | 0.08 (1) | c.617_619delTTG(p.Val207del) c.617_619delTTG(p.Val207del) | 20 |

| 43 (M)a | 9 years (4 months) | First degree cousin | Developmental delay, hearing loss | 0.21 (3) | c.98_104delinsTCC/(p.C33Ffs*36) c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | 20 |

| 75 (M) | 6 years (3 years) | First degree cousin | Motor mental retardation, seziure | 1.90 (27) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 10 |

| 76 (F) | 19 years (17 years) | Second degree cousin | Hypoglycemia, ketoacidosis | 1.90 (17) | c.98-104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 10 |

| 77 (F)b | 7 years (4 years) | Absent | Seziure hypotyroidism | 2.73 (38) | c.1320delG(p.L440Lfsx61) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 5 |

| 82 (M) | 6.5 years (4.5 years) | First degree cousin | Otism spectrum disorder | 2.96 (42) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 5 |

| 90 (F) | 4 years (2 years) | Absent | Developmental retardation | 1.12 (16) | p.A171T (c. 511G>A) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 10 |

| 139 (M)a | 2 years (15 days) | Absent | Severe diaper dermatitis | 2.06 (29) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 5 |

| 216 (M)a | 2 years (17 days) | Absent | Hearing loss | 2.05 (25) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 5 |

aNewborn screening; bFamily screening; cReference: 4.4–12.

The diagnosis was confirmed with biotinidase enzyme activities in all patients and with BTD gene analysis in 226 (87.2%) patients. The mean biotinidase enzyme activity of the patients was 1.22±0.68 nmol/mL/min (0.04–3.0) and % 16.66±9.11 (% 1–% 42). The mean lactic acid level at the time of diagnosis was 12.8 mg/dL (range: 5.4–38.8). The highest lactic acid level during follow-up was 62 mg/dL. Blood spotfree carnitine and acyl carnitine analyses were normal. Only two patients’ urine organic acid analysis revealed methylcitrate elevation.

The biotinidase enzyme levels of 14 patients were below 3 nmol/min/mL (reference: 4.4–12). They had >30% enzyme activity and they also all had pathogenic mutations in both alleles of the BTD gene. Ten of them had the homozygous p.D444H mutation; two patients had compound heterozygous p.D444H/c1324delG mutations. Details of these patients are given in Table 3.

The patients with >30% enzyme activity and had mutations in both BTD gene alleles.

| Patient no. (sex) | Age/age at diagnosis | Biotinidase enzyme levels, nmol/dk/mLa (activity %) | BTD gene analysis, 1 allele, 2 allele | Clinical findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 77 (M) | 7 years/4 months | 2.73 (38) | c1324delG(p.V442Sfs*59) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Seziure, hypotyroidism |

| 82 (M) | 6.5 years/4.5 years | 2.96 (42) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Otism spectrum disorder |

| 153 (F) | 1 year/1 month | 2.61 (37) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymptomatic |

| 161 (M) | 2.5 years/15 days | 2.36 (33) | c.1324delG(p.V442Sfs*59) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymtomatic |

| 162 (F) | 10 months/15 days | 2.34 (33) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Kongenital anomelia imperfore anus |

| 167 (M) | 9 months/1 month | 2.63 (37) | p.R157H(c.470G>A) p.G45R (c.133G>A) | Asymptomatic |

| 169 (M) | 11 months/1 month | 2.27 (32) | c.1324delG(p.V442Sfs*59) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymptomatic |

| 179 (M) | 1.5 years/1 month | 2.80 (40) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymptomatic |

| 198 (F) | 2 years/21 days | 2.84 (40) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Severe diaper dermatitis |

| 213 (M) | 2 years/24 days | 2.35 (33) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymptomatic |

| 234 (M) | 1.5 years/24 days | 2.20 (32) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymptomatic |

| 248 (F) | 5.5 years/1.5 months | 2.43 (34) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymptomatic |

| 257 (F) | 2 years/1.5 months | 2.30 (32) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Seboraic dermatitis |

| 261 (F) | 9 months/1.5 months | 2.23 (31) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | Asymptomatic |

aReference: 4.4–12.

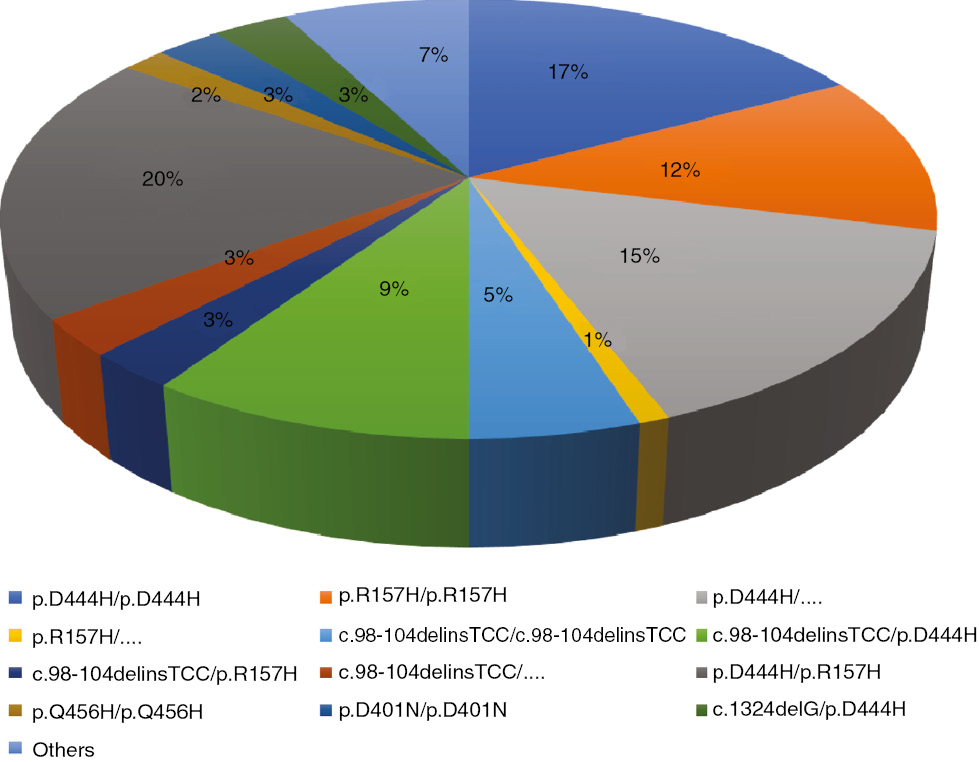

Biotinidase gene analysis was performed in 226 (87.2%) patients. Ninety-seven (42.9%) patients had homozygous mutations, and 125 (55.3%) patients had the compound heterozygous mutation. Four patients had partial BD and had the heterozygous mutation. The most common mutation was p.R157H/p.D444H (44 patients; 19.4%), the second most common mutation was compound heterozygote mutations with p.D444H (41 patients; 16%). Thirty-eight (16.8%) patients had homozygote p.D444H mutation and homozygote p.R157H mutation was found in 26 (11.5%) patients. Six patients’ BTD gene analysis revealed a homozygous p.D401N mutation. To the best of our knowledge this mutation is a novel mutation in BD patients. Details of the BTD gene analysis of the patients are given in Figure 1.

Details of biotinidase gene analysis of the patients.

Of the 73 patients with profound BD, 59 (80.8%) of them had BTD gene analysis. None of the patients with profound deficiency had homozygote p.D444H mutation. Two patients who had p.D444H mutation had a profound deficiency and mutations in the second alleles of the patients’ were p.A287T and p.Q456H. The most common mutation was homozygote p.R157H mutation in profound BD patients. Twenty patients (33.8%) had homozygote p.R157H mutation. The mutation analysis of patients with profound BD are summarized in Table 4.

BTD gene analysis of the patients with profound biotinidase.

| Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| p.R157H(c.470G>A) | p.R157H(c.470G>A) | 20 |

| c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | 9 |

| c.98-104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | p.R157H(c.470G>A) | 6 |

| p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | 3 |

| p.C186Y(c.557G>A) | p.C186Y(c.557G>A) | 2 |

| c.98-104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | p.D444H (c.1330G>C) | 2 |

| p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | p.A287T(c.859G>A) | 1 |

| p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | 1 |

| c.98_104delinsTCC (p.C33Ffs*36) | p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | 1 |

| c98-104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | p.V457M(c.1369G>A) | 1 |

| c.98-104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | p.Y454C (c.1361A>G) | 1 |

| c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | p.S319F(c.956C>T) | 1 |

| p.E64K (c.190G>A) | p.E64K(c.190G>A) | 1 |

| p.R79C(c.235C>T) | p.R79C(c.235C>T) | 1 |

| c.617-619delTTG(p.Val207del) | c.617_619delTTG(p.Val207del) | 1 |

| p.V199M(c.595G>A) | p.V199M(c.595G>A) | 1 |

| p.F128S(c.383T>C) | p.F128S(c.383T>C) | 1 |

| p.T532M(c.1595C>T) | p.T532M(c.1595C>T) | 1 |

| p.V457M(c.1369G>A) | p.V457M(c.1369G>A) | 1 |

| c.617-619delTTG(p.Val207del) | c.617-619delTTG(p.Val207del) | 1 |

| c.1324delG(p.V442Sfs*59) and D444H(c.1330G>C) | p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | 1 |

| p.T532M(c.1595C>T) | c407-408insA (V137Gfs*15) | 1 |

| p.C143F (c.428 G>T) | p.T532M(c.1595C>T) | 1 |

Of the 186 patients with partial BD, 167 (89.7%) of them had BTD gene analysis. The most common mutations are p.R157H/p.D444H (44 patients, 26.3%) and homozygote p.D444H mutations (38 patients, 22.7%). The patients having the novel mutations p.D401N were all partial BD. Also, the patients having c.1324delG/p.D444H compound heterozygote mutation were all partial BD. The mutation analysis of these patients are summarized in Table 5.

BTD gene analysis of the patients with partial biotinidase deficiency.

| Mutation 1 | Mutation 2 | Number of patients |

|---|---|---|

| p.R157H(c.470G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 44 |

| p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 38 |

| p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | 20 |

| p.D401N (c.1201G>A) | pD401N(c.1201G>A) | 6 |

| c1324delG(p.V442Sfs*59) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 6 |

| p.R157H(c.470G>A) | p.R157H(c.470G>A) | 6 |

| p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 6 |

| p.A171T(c. 511G>A) and p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 3 |

| p.T532M(c.1595C>T) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 2 |

| p.N214S (c.641A>G) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 2 |

| p.C186Y(c.557G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 2 |

| p.V199M(c.595G>A) | p.V199M(c.595G>A) | 2 |

| c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | 2 |

| p.R157H(c.470G>A) | NA | 2 |

| p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | 1 |

| c1324delG(p.V442Sfs*59) and p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| c.407-408insA(V137Gfs*15) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| c617-619del/TTG(p.Val207del) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| c617-619del/TGG(p.Val207del) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.A171T(c. 511G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.A287T(c.859G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.R79C(c.235C>T) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.V457M(c.1369G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.V457M(c.1369G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.T532M(c.1595C>T) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.S319F (c.956C>T) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.R211C (c.631 C>T) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| c1320delG (p.L440Lfsx61) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.P73L (c.218C>T) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.F128S(c.383T>C) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.E64K (c.190G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.P497S (c.1489C>T) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.D401N(c.1201G>A) | p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | 1 |

| p.R79C(c.235C>T) | p.Q511E (c.1531C>G) | 1 |

| p.S491G(c.1471A>G) | p.Q456H(c.1368A>C) | 1 |

| c.98_104delinsTCC(p.C33Ffs*36) | p.A82G (c.245C>G) | 1 |

| p.R157H(c.470G>A) | p.V199M(c.595G>A) | 1 |

| p.R157H(c.470G>A) | p.G45R (c.133G>A) | 1 |

| p.F128S(c.383T>C) and p.P391S (c.1171C>T) | NA | 1 |

| p.D444H(c.1330G>C) | NA | 1 |

Four (1.7%) patients had a heterozygote mutation. All of these patients had partial BD with enzyme activities of 14%, 15%, 21%, 23% and with the mutations p.F128S and p.P391S (cis position), p.R157H, p.R157H, and p.D444H and, respectively.

The novel mutations which were detected in this study are p.D401N(c.1201G>A), p.A82G(c.245C>G), p.F128S(c.383T>C), c617_619del/TTG(p.Val207del), p.A287T(c.859G>A), p.S491H(c.1471A>G). The p.D401N (in one or both alleles), p.A82G (in one allele), pP391S (in one allele) mutations were detected in partial BD. Homozygote p.F128S mutation was detected in one profound BD patient. Also, p.F128S was found in one allele of a patient with partial BD.

All patients were treated with biotin; 5–10 mg/day in patients with partial BD and 10–20 mg/day in patients with profound BD. The mean follow-up period was 3.4±2.7 (6 months–17.9 years). During follow-up, one patient who had been diagnosed with partial BD by newborn screening with a compound heterozygous mutation p.A171T/p.D444H had a mild developmental delay at the age of 3.5 years. The examinations of other systems were normal and a cranial magnetic resonance imaging was normal.

During follow-up, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder was detected in five patients. Three of them had partial BD; two patients had profound BD. The BTD gene analysis of these patients revealed p.A171T/p.D444H, c1324delG and p.D444H/p.D444H, c.407-408insA/p.D444H and homozygous p.R157H, homozygous c.98-104 delinsTCC, respectively.

Four patients had a diagnosis of a different disease coincidentally during follow-up. Three of them (Patient nos. 173, 235, 25) had partial BD and were treated with biotin (5–10 mg/day) therapy. Patient 58 had a profound deficiency and was treated with 20 mg/day biotin. A 6-year-old boy with partial BD, had a complaint of dark-colored urine after the age of 18 months. Urine organic acid analysis revealed high homogentisic acid levels; 1534 nmol/mol creatine (N: 0). He has normal growth and development. An eye examination, hearing test, echocardiography and urine protein analysis were normal. Creatine kinase elevation was detected in one patient, who had low α-glycosidase enzyme activity, and GAA gene analysis revealed compound heterozygous IVS1041G>T (c.1551+G>T)/p.T653N (c.1958C>A) mutation and was diagnosed with Pompe disease. His echocardiography was normal. Patient 58 had direct bilirubinemia and was diagnosed with Gilbert’s syndrome. Patient 51 had hemolytic anemia and was diagnosed with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD). The details of the patient with coincidental second diseases are given in Table 6.

The patients with co-incidental diseases which were detected during follow-up of patients.

| Patient no. | Age/age at diagnosis | Consanguinity | Biotinidase enzyme levels, nmol/dk/mLa (activity %) | BTD gene analysis | Co-incidental disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58 (M) | 6 years/1.5 months | First degree cousin marriage | 0.40 (6) | p.F128S/p.F128S | Gilbert disease |

| 173 (M) | 1 year/1 month | None | 1.30 (18) | p.R157H/p.D444H | Alkaptonuria |

| 235 (M) | 1 year/21 days | First degree cousin marriage | 1.94 (27) | p.D444H/p.D444H | Pompe disease |

| 251 (M) | 4.2 years/24 days | None | 2.10 (30) | p.D444H/p.D444H | G6PD deficiency |

aReference: 4.4–12.

Iron deficiency anemia was detected in 30 (11.5%) patients, and vitamin B12 deficiency was detected in three (1.5%) patients. Two (0.7%) patients had benign transient alkaline phosphatase elevation.

Discussion

BD is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by the deficiency of the enzyme biotinidase. Clinical signs include vomiting, hypotonia, seizures, development delay, optic atrophy, lactic acidosis, ketosis, skin rash, alopecia, hearing loss, hyperammonemia and respiratory problems [5], [6], [7]. The incidence of BD is 1:40,000–1:60,000 births in the world according to previous studies; however, in some countries, this prevalence is higher due to high rates of consanguinity [14]. Based on the data published by the Turkish Ministry of Health, the incidence of BD is approximately 1:7116 [15]. BD is a common disorder in Turkey [16]. In our study, the consanguinity rate was detected in 33.2% of the patients, which was high.

Children with profound deficiency usually presented with neurological involvement in the first years of life [14]. Symptoms of untreated profound BD usually appear between the ages of 1 week and 10 years with a mean age of 3.5 months [7]. Some patients with profound BD do not exhibit symptoms until adolescence or adulthood [7]. In this study total, 12 patients had symptoms, and five of them had profound BD. Two parents were diagnosed with profound BD and they were also asymptomatic.

Wolf [17] demonstrated the clinical findings of patients with delayed-onset BD. These older children and adolescents exhibited neurological features that included para- or tetraparesis with vision loss or scotomas. These patients who first presented with symptoms as older children and adolescents had profound BD [17]. In our study, a patient with profound BD had sudden loss of vision and muscular weakness and was treated with steroids before the diagnosis. Especially for those patients who were born before the newborn screening program, BD should be considered as the differential diagnosis according to the clinical symptoms and signs.

Having sufficient residual enzyme activity may be the reason for the presence of the asymptomatic patients. When stressed with a severe infection, they may develop symptoms. The presence of epigenetic factors or dietary differences in biotin intake that protect some patients from developing symptoms has also been reported [18]. Similarly, in our study, a 19-year-old-girl was diagnosed with partial BD at the age of 16 years. She had recurrent hypoglycemia and ketoacidosis attacks usually during upper airway tract infections. She had a partial deficiency and had the c98-104delinsTCC/p.D444H compound heterozygote mutation. After starting biotin therapy, she became asymptomatic.

In the literature, there are some reports about asymptomatic adult relatives and siblings of symptomatic children or the patients who were diagnosed by newborn screening and remained asymptomatic without therapy [19], [20]. Although they may still be at risk for having symptoms the absence of suggested symptoms may be due to epigenetic factors that protect some enzyme-deficient patients from developing symptoms [14]. In this study, 15 parents were diagnosed with BD and they were all asymptomatic. A group of children with less than 1% activity did not develop symptoms and in a group of patients with 1%–10% mean normal activity the patients developed symptoms during the first few months of life. The recommendation is to treat all children with profound BD [14]. In our study, most of the patients were asymptomatic, and it may be the result of the detection of patients by the newborn screening program and have been treated in early ages.

Untreated children may exhibit metabolic ketoacidosis, lactic acidosis and/or hyperammonemia. BD is associated with typical organic aciduria including elevated excretion of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid, 3-methylcrotonylglycine, methylcitrate and lactate which can be an important clue for the diagnosis. As the brain becomes biotin deficient earlier and effects the liver or the kidney more severely, patients may present with the serious neurological disease without showing clear abnormalities of organic acid excretion. 3-Hydroxy-isovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) levels may also be elevated in some patients [21], [22]. In our study, lactate levels were elevated in some patients. As most of our patients were detected by newborn screening and were treated in early ages, all of our patients’ C5-OH carnitine levels were normal, and only two of them revealed methylcitrate elevation in the urinary organic acid analysis.

Genc et al. [23] from Turkey demonstrated that during the years when the BD was not included in the newborn screening program, sensorineural hearing loss occured in approximately 55% of the patients with BD. In the follow-up, there were no differences in the audiograms compared to those of initial tests [23]. In our study, only two (0.7%) of the patients had hearing loss, and during follow-up no changes were detected in their audiograms.

In our study, 14 (5.4%) patients had low enzyme activity (< 3 nmol/min/mL) and had mutations in both alleles of the BTD gene. Ten of these patients had homozygote p.D444H. Although, patients 198 had 40% enzyme activity she had severe diaper dermatitis which responded to biotin treatment.

It was shown that the p.D444H mutation alone is a “milder” mutation and combined with a mutation for profound BD on the other allele results in partial BD whereas in the cis allele with A171T as the double mutant p.A171T:D444H; results in a profound BD [24]. We found three patients who had the mutation p.A171T:p.D444H/ p.D444H and they all had partial BD.

The children homozygous for p.D444H allele have about 50% of mean normal serum activity which is similar to that of individuals who are heterozygous for a single profound BD allele. This mutation is relatively frequent with an estimated frequency of 0.039 in the general population of Virginia [21], [25]. Similarly, in our study homozygote p.D444H mutation was frequent and this mutation was not detected in profound BD patients.

The mutations c.1324delG and p.S319F were recently reported by Seker Yilmaz et al. [26] as a novel mutation. In our study, six patients with partial deficiency had c.1324delG/p.D444H mutations, and two patients had p.S319F mutation combined with p.D444H and c98_104delinsTCC. The mutation c1320delG was also reported as a novel mutation by Sivri et al. [27]. One of our patients had this mutation with a partial deficiency. Pomponio et al. [28] reported the novel mutation R79C in the Turkish population, and Liu et al. [29] reported this mutation as a wild-type mutation. In this study, p.R79C/p.R79C mutation results in profound BD and this mutation results in a partial deficiency when combined with the p.D444H or Q511E mutation. The mutation p.C143F was described as a novel mutation by Karaca et al. [30]. We also detected this mutation combined with T532M in a profound BD patient.

Mikati et al. [31] reported the novel mutation p.E64K with partial BD, in our study, homozygote p.E64K mutation presented with profound BD and a compound heterozygote mutation p.E64K/p.D444H found in partial BD. In the literature, the p.P497S mutation frequently found in Somali patients who were detected with profound BD by newborn screening in Minnesota [32]. One patient had this mutation (p.P497S/p.D444H) with partial BD.

According to the literature, the mutations p.R157H, p.C186Y, p.T532M, p.Q456H were related with profound deficiency [33]. Also, we found these mutations in more than half of our patients with profound BD.

The novel mutations which were detected in this study are p.D401N, p.A82G, p.F128S, c617_619del/TTG, p.A287T, p.S491H. Genotype-phenotype correlations are not well established in BD. Deletions, insertions or nonsense mutations generally result in the complete absence of biotinidase activity [7]. Although genotype-phenotype correlation is not established, Sivri et al. [27] reported that all children with symptoms and with hearing loss were homozygous for null mutations whereas the children with symptoms but with normal hearing were all homozygous for missense mutations.

Reports from multiple countries provided awareness of children with partial BD who were not treated with biotin, but developed symptoms such as hypotonia, skin rashes and loss of hair when they had an infectious disease or moderately severe gastroenteritis [34]. In our study, three (1.6%) patients were symptomatic although they had partial BD. Two of these patients had severe diaper dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis which had a response to biotin therapy although they had biotinidase activity of 32% and 40%, respectively. We think that many issues are unclear in BD. We treated all the patients with profound deficiency and partial deficiency. Patient 75 (the patient was diagnosed at 3 years of age) had partial BD with the homozygote mutation p.D444H and had motor mental retardation and seizures. As the BTD activity could be affected by both genetic and non-genetic factors such as age, prematurity, neonatal jaundice, the temperature of the sample during storage or transport, the BD genotype and biochemical phenotype (profound BD, partial BD or heterozygous activity) is not always consistent. Therefore, the diagnosis of BD should be based on more than one measurement of plasma biotinidase activity, and the highest enzyme activity result should be used for the classification [35].

Children with profound BD are treated with pharmacologic doses of biotin (5–20 mg daily). Monitoring of urinary organic acids may be the only useful method for ascertaining whether the biotin dosage is sufficient [14]. We are using organic acid analysis for monitoring the blood lactate levels. Under biotin therapy, usually blood lactate levels were decreased in our study, and organic acid analysis returned to normal in the patients who were diagnosed by newborn screening. In our study, biotin treatment dose in patients with profound BD was 10–20 mg/day and 5–10 mg/day in partial BD patients. The only concern about using an optimal dose of biotin comes from the reports of several females who lose their hair during the pubertal period. Increasing the dose of biotin stopped their hair loss [14]. In our study, one mother with partial BD reported that hair loss decreased with biotin treatment.

Regular follow-up of our patients gave us a chance to detect the co-incidental diseases such as alkaptonuria, Pompe, G6PD and Gilbert’s syndrome. To the best of our knowledge, these co-incidental diseases which were detected in our study were not reported in the literature of patients with BD. We thought that the patients with inherited metabolic disorders might have a second inherited disorder especially in countries which have a high rate of consanguineous marriage.

Conclusions

After the inclusion of BD in the newborn screening program, the number of patients has increased. We determined the clinical and genetic spectrum of a large group of patients with BD from the western part of Turkey. The frequent mutations in our study were similar to the literature. We found six novel mutations. Due to the high rate of consanguinity, we also detected some co-incidental inherited disorders during follow-up of our patients. Most of our patients were asymptomatic in this study. We would like to emphasize the importance of late-onset symptomatic disease which responds to biotin treatment.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Zempleni J, Kuroishi T. Biotin. Adv Nutr 2012;3:213–4.10.3945/an.111.001305Search in Google Scholar

2. Wolf B. The neurology of biotinidase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2011;104:27–34.10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.06.001Search in Google Scholar

3. Pispa J. Animal biotinidase. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenn 1965;43:1–39.Search in Google Scholar

4. Wolf B, Feldman GL. The biotin-dependent carboxylase deficiencies. Am J Hum Genet 1982;34:699–716.Search in Google Scholar

5. Wolf B, Grier RE, Secor McVoy JR, Heard GS. Biotinidase deficiency: a novel vitamin recycling defect. J Inherit Metab Dis 1985;8:53–8.10.1007/978-94-011-8019-1_10Search in Google Scholar

6. Wolf B, Grier RE, Allen RJ, Goodman SI, Kien CL. Biotinidase deficiency: the enzymatic defect in late-onset multiple carboxylase deficiency. Clin Chim Acta 1983;131:273–81.10.1016/0009-8981(83)90096-7Search in Google Scholar

7. Wolf B. Biotinidase deficiency: “if you have to have an inherited metabolic disease, this is the one to have.” Genet Med 2012;14:565–75.10.1038/gim.2011.6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Wolf B, Heard GS, Jefferson LG, Proud VK, Nance WE, et al. Clinical findings in four children with biotinidase deficiency detected through a statewide neonatal screening program. N Engl J Med 1985;313:16–9.10.1056/NEJM198507043130104Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Cole H, Weremowicz S, Morton CC, Wolf B. Localization of serum biotinidase (BTD) to human chromosome 3 in band p25. Genomics 1994;22:662–3.10.1006/geno.1994.1449Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Knight HC, Reynolds TR, Meyers GA, Pomponio RJ, Buck GA, et al. Structure of the human biotinidase gene. Mamm Genome 1998;9:327–30.10.1007/s003359900760Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Wolf B. Biotinidase deficiency and our champagne legacy. Gene 2016;589:142–50.10.1016/j.gene.2015.10.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Knappe J, Brommer W, Brederbick K. Reinigung und Eigenschaften der Biotinidase aus Schweinenieren und Lactobacillus casei. Biochem Z 1963;338:599–613.Search in Google Scholar

13. Yilmaz S, Serin M, Canda E, Eraslan C, Tekin H, et al. A treatable cause of myelopathy and vision loss mimicking neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: late-onset biotinidase deficiency. Metab Brain Dis 2017;32:675–8.10.1007/s11011-017-9984-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Wolf B. Clinical issues and frequent questions about biotinidase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 2010;100:6–13.10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.01.003Search in Google Scholar

15. Anonymous (2011) Newborn screening program in Turkey. Ministry of Health of mother-child and family planning general management. Ankara, Turkey: Ministry of Health of Mother-Chilld and Family Planning.Search in Google Scholar

16. Baykal T, Hüner G, Sarbat G, Demirkol M. Incidence of biotinidase deficiency in Turkish newborns. Acta Paediatr 1998;87:1102–3.10.1080/080352598750031518Search in Google Scholar

17. Wolf B. Biotinidase deficiency should be considered in individuals exhibiting myelopathy with or without and vision loss. Mol Genet Metab 2015;116:113–8.10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.08.012Search in Google Scholar

18. Pindolia K, Jordan M, Wolf B. Analysis of mutations causing biotinidase deficiency. Hum Mutat 2010;31:983–91.10.1002/humu.21303Search in Google Scholar

19. Wolf B, Norrgard K, Pomponio RJ, Mock DM, McVoy JR, et al. Profound biotinidase deficiency in two asymptomatic adults. Am J Med Genet 1997;73:5–9.10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19971128)73:1<5::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-USearch in Google Scholar

20. Baykal T, Gokcay G, Gokdemir Y, Demir F, Seckin Y, et al. Asymptomatic adults and older siblings with biotinidase deficiency ascertained by family studies of index cases. J Inherit Metab Dis 2005;28:903–12.10.1007/s10545-005-0161-3Search in Google Scholar

21. Cowan TM, Blitzer MG, Wolf B; Working Group of the American College of Medical Genetics Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Technical standards and guidelines for the diagnosis of biotinidase deficiency. Genet Med 2010;12:464–70.10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181e4cc0fSearch in Google Scholar

22. Chalmers RA, Roe CR, Stacey TE, Hoppel CL. Urinary excretion of l-carnitine and acylcarnitines by patients with disorders of organic acid metabolism: evidence for secondary insufficiency of l-carnitine. Pediatr Res 1984;18:1325–8.10.1203/00006450-198412000-00021Search in Google Scholar

23. Genc GA, Sivri-Kalkanoğlu HS, Dursun A, Aydin HI, Tokatli A, et al. Audiologic findings in children with biotinidase deficiency in Turkey. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2007;71:333–9.10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.11.001Search in Google Scholar

24. Hymes J, Stanley CM, Wolf B. Mutations in BTD causing biotinidase deficiency. Hum Mutat 2001;18:375–81.10.1002/humu.1208Search in Google Scholar

25. Swango KL, Demirkol M, Hüner G, Pronicka E, Sykut-Cegielska J, et al. Partial biotinidase deficiency is usually due to the D444H mutation in the biotinidase gene. Hum Genet 1998;102:571–5.10.1007/s004390050742Search in Google Scholar

26. Seker Yilmaz B, Mungan NO, Kor D, Bulut D, Seydaoglu G, et al. Twenty-seven mutations with three novel pathologenic variants causing biotinidase deficiency: a report of 203 patients from the southeastern part of Turkey. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2018;31:339–43.10.1515/jpem-2017-0406Search in Google Scholar

27. Sivri HS, Genç GA, Tokatli A, Dursun A, Coşkun T, et al. Hearing loss in biotinidase deficiency: genotype-phenotype correlation. J Pediatr 2007;150:439–42.10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.036Search in Google Scholar

28. Pomponio RJ, Coskun T, Demirkol M, Tokatli A, Ozalp I, et al. Novel mutations cause biotinidase deficiency in Turkish children. J Inherit Metab Dis 2000;23:120–8.10.1023/A:1005609614443Search in Google Scholar

29. Liu Z, Zhao X, Sheng H, Cai Y, Yin X, et al. Clinical features, BTD gene mutations, and their functional studies of eight symptomatic patients with biotinidase deficiency from Southern China. Am J Med Genet A 2018;176:589–96.10.1002/ajmg.a.38601Search in Google Scholar

30. Karaca M, Özgül RK, Ünal Ö, Yücel-Yılmaz D, Kılıç M, et al. Detection of biotinidase gene mutations in Turkish patients ascertained by newborn and family screening. Eur J Pediatr 2015;174:1077–84.10.1007/s00431-015-2509-5Search in Google Scholar

31. Mikati MA, Zalloua P, Karam P, Habbal MZ, Rahi AC. Novel mutation causing partial biotinidase deficiency in a Syrian boy with infantile spasms and retardation. J Child Neurol 2006;21:978–81.10.1177/08830738060210110301Search in Google Scholar

32. Sarafoglou K, Bentler K, Gaviglio A, Redlinger-Grosse K, Anderson C, et al. High incidence of profound biotinidase deficiency detected in newborn screening blood spots in the Somalian population in Minnesota. J Inherit Metab Dis 2009;32:169–73.10.1007/s10545-009-1135-7Search in Google Scholar

33. Thodi G, Schulpis KH, Molou E, Georgiou V, Loukas YL, et al. High incidence of partial biotinidase deficiency cases in newborns of Greek origin. Gene 2013;524:361–2.10.1016/j.gene.2013.04.059Search in Google Scholar

34. McVoy JR, Levy HL, Lawler M, Schmidt MA, Ebers DD, et al. Partial biotinidase deficiency: clinical and biochemical features. J Pediatr 1990;116:78–83.10.1016/S0022-3476(05)81649-XSearch in Google Scholar

35. Borsatto T, Sperb-Ludwig F, Lima SE, Carvalho MR, Fonseca PA, et al. Biotinidase deficiency: genotype-biochemical phenotype association in Brazilian patients. PLoS One 2017;12:0177503.10.1371/journal.pone.0177503Search in Google Scholar

©2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Urinary bisphenol-A levels in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus

- The relationship between metabolic syndrome, cytokines and physical activity in obese youth with and without Prader-Willi syndrome

- Association of anthropometric measures and cardio-metabolic risk factors in normal-weight children and adolescents: the CASPIAN-V study

- The effect of obesity and insulin resistance on macular choroidal thickness in a pediatric population as assessed by enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography

- Hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets (HVDRR): clinical heterogeneity and long-term efficacious management of eight patients from four unrelated Arab families with a loss of function VDR mutation

- Long-term thyroid disorders in pediatric survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after chemotherapy-only conditioning

- Screening for autoimmune thyroiditis and celiac disease in minority children with type 1 diabetes

- Resistance exercise alone improves muscle strength in growth hormone deficient males in the transition phase

- Sequential measurements of IGF-I serum concentrations in adolescents with Laron syndrome treated with recombinant human IGF-I (rhIGF-I)

- Symptomatic Rathke cleft cyst in paediatric patients – clinical presentations, surgical treatment and postoperative outcomes – an analysis of 38 cases

- Molecular genetics of tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency in Chinese patients

- Single center experience of biotinidase deficiency: 259 patients and six novel mutations

- Next-generation sequencing as a second-tier diagnostic test for newborn screening

- Case Reports

- Thyroid storm after choking

- Three new Brazilian cases of 17α-hydroxylase deficiency: clinical, molecular, hormonal, and treatment features

- Diazoxide toxicity in a child with persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy: mixed hyperglycemic hyperosmolar coma and ketoacidosis

- Refractory hypoglycemia in a pediatric patient with desmoplastic small round cell tumor

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Urinary bisphenol-A levels in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus

- The relationship between metabolic syndrome, cytokines and physical activity in obese youth with and without Prader-Willi syndrome

- Association of anthropometric measures and cardio-metabolic risk factors in normal-weight children and adolescents: the CASPIAN-V study

- The effect of obesity and insulin resistance on macular choroidal thickness in a pediatric population as assessed by enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography

- Hereditary 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-resistant rickets (HVDRR): clinical heterogeneity and long-term efficacious management of eight patients from four unrelated Arab families with a loss of function VDR mutation

- Long-term thyroid disorders in pediatric survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after chemotherapy-only conditioning

- Screening for autoimmune thyroiditis and celiac disease in minority children with type 1 diabetes

- Resistance exercise alone improves muscle strength in growth hormone deficient males in the transition phase

- Sequential measurements of IGF-I serum concentrations in adolescents with Laron syndrome treated with recombinant human IGF-I (rhIGF-I)

- Symptomatic Rathke cleft cyst in paediatric patients – clinical presentations, surgical treatment and postoperative outcomes – an analysis of 38 cases

- Molecular genetics of tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency in Chinese patients

- Single center experience of biotinidase deficiency: 259 patients and six novel mutations

- Next-generation sequencing as a second-tier diagnostic test for newborn screening

- Case Reports

- Thyroid storm after choking

- Three new Brazilian cases of 17α-hydroxylase deficiency: clinical, molecular, hormonal, and treatment features

- Diazoxide toxicity in a child with persistent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia of infancy: mixed hyperglycemic hyperosmolar coma and ketoacidosis

- Refractory hypoglycemia in a pediatric patient with desmoplastic small round cell tumor