Abstract

Context

The United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) is not required for osteopathic students to match into postgraduate programs; however, it is unknown if taking the test improves their chances of matching.

Objectives

Our objective was to determine the association between taking the USMLE Step 1 and matching into the applicant’s preferred specialty for senior osteopathic students applying to the 10 specialties to which students applied most in 2020.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of the free and publicly available 2020 National Residency Match Program (NRMP) published match report for senior osteopathic students. First, we determined the number of senior osteopathic students that matched into their preferred specialty vs those that did not and stratified them by reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 within each specialty. Next, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) within each specialty for senior osteopathic students matching into their preferred specialty with and without the USMLE Step 1 utilizing the Fisher’s exact test. Finally, we repeated the analysis with only senior osteopathic students who had reported USMLE Step 1 scores in ranges including or below the mean for those who matched in their specialty.

Results

For senior osteopathic students, reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 was associated with matching for those who applied to Internal Medicine (OR 3.3 [95% confidence interval 2.07 to 5.48]), Emergency Medicine (2.1 [1.35 to 3.17]), Pediatrics (4.4 [1.38 to 18.63]), Psychiatry (2.5 [1.34 to 4.98]), Anesthesiology (3.4 [1.57 to 7.32]), and General Surgery (3.1 [1.56 to 6.14]). After repeating the analysis with only senior osteopathic students who reported low USMLE Step 1 scores, the association remained significant for those who applied to Internal Medicine (2.5 [1.49 to 4.28]), Anesthesiology (2.6 [1.17 to 5.54]), and General Surgery (2.5 [1.24 to 5.04]).

Conclusions

In 2020, reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 by senior osteopathic students was associated with matching for those who applied to Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, Anesthesiology, and General Surgery. In addition, reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 with a low score was associated with matching for those who applied to Internal Medicine, Anesthesiology, and General Surgery.

The United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), similar to the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination (COMLEX-USA), is a series of board tests that allopathic medical students must pass to transition to postgraduate medical education training programs and medical licensure [1]. While osteopathic medical students are eligible to take the USMLE, it is not required to match into postgraduate programs [2].

Although taking the USMLE is not required for osteopathic students to match, it may improve their chances of matching for a couple of reasons. First, although USMLE and COMLEX-USA scores correlate [3], [4], [5], many postgraduate programs are unfamiliar with COMLEX-USA scores, and conversion formulas predicting USMLE scores from COMLEX-USA scores may underestimate the USMLE scores [5]. Therefore, senior osteopathic students without USMLE scores may appear less competitive to postgraduate programs that utilize these formulas. Second, many senior osteopathic students report discrimination for not taking the USMLE and encounter postgraduate programs that specifically require the USMLE [6]. Therefore, although programs have been encouraged to accept the COMLEX-USA [7, 8], not taking the USMLE may still limit the opportunities available for senior osteopathic students.

It is unknown whether completing the USMLE improves the match outcomes for most senior osteopathic students. Therefore, our objective was to determine the association between taking the USMLE Step 1 and matching into the senior osteopathic student’s preferred specialty in 2020.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of specialty-level match data of the published match results from the 2020 National Residency Match Program (NRMP) for senior osteopathic students; the report is free and publicly available online [9]. This study does not meet the 2018 Revised Common Rule criteria for human subjects research because the data were not specifically collected for our study, and no one on our study team had access to any subject identifiers [10].

To mitigate any bias that more competitive specialties and those with fewer applicants would impose on the results, we restricted our analysis to the 10 specialties to which students applied most (i.e., those with the most applicants). The NRMP determined an applicant’s preferred specialty by their first-ranked program, and match success was defined as matching into the preferred specialty [9]. Because there is no incentive for withholding a failure or poor score from the NRMP on the optional research form, we assumed that senior osteopathic students who did not report taking the USMLE Step 1 did not take it. However, we also assumed that senior osteopathic students who did not report taking the COMLEX-USA Level 1 would not report taking the USMLE Step 1. Because these students were likely true nonreporters rather than individuals who did not take the USMLE Step 1, we subtracted the number of COMLEX-USA Level 1 nonreporters from the number of USMLE Step 1 nonreporters within each specialty. The remaining senior osteopathic students who did not report taking the USMLE Step 1 were assumed to have not taken the test.

We then determined the total number of senior osteopathic students that matched vs those that did not and stratified them by reported USMLE Step 1 completion within each specialty. Next, we reported the proportions matched with and without the USMLE Step 1. Then, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) for senior osteopathic students matching with the USMLE Step 1 compared to those without utilizing the Fisher’s exact test. Lastly, because students may not take the USMLE due to fear of performing poorly, we repeated the analysis with only senior osteopathic students who had reported USMLE Step 1 scores in ranges including or below the mean for their preferred specialty (Table 1). ORs with confidence intervals that did not include one were considered significant and all analyses were performed in RStudio® (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, Version 2021.09.0+351).

USMLE Step 1 low-score thresholds.

| Specialty | USMLE low-score thresholda |

|---|---|

| Internal medicine | 230 |

| Family medicine | 220 |

| Emergency medicine | 230 |

| Pediatrics | 230 |

| Psychiatry | 230 |

| Anesthesiology | 240 |

| General surgery | 240 |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 230 |

| Diagnostic radiology | 240 |

| Orthopedic surgery | 250 |

-

USMLE, United States Medical Licensing Examination. aThe upper limit of the National Residency Match Program (NRMP) reported a USMLE Step 1 score range that includes the mean for those who matched in the given specialty.

Results

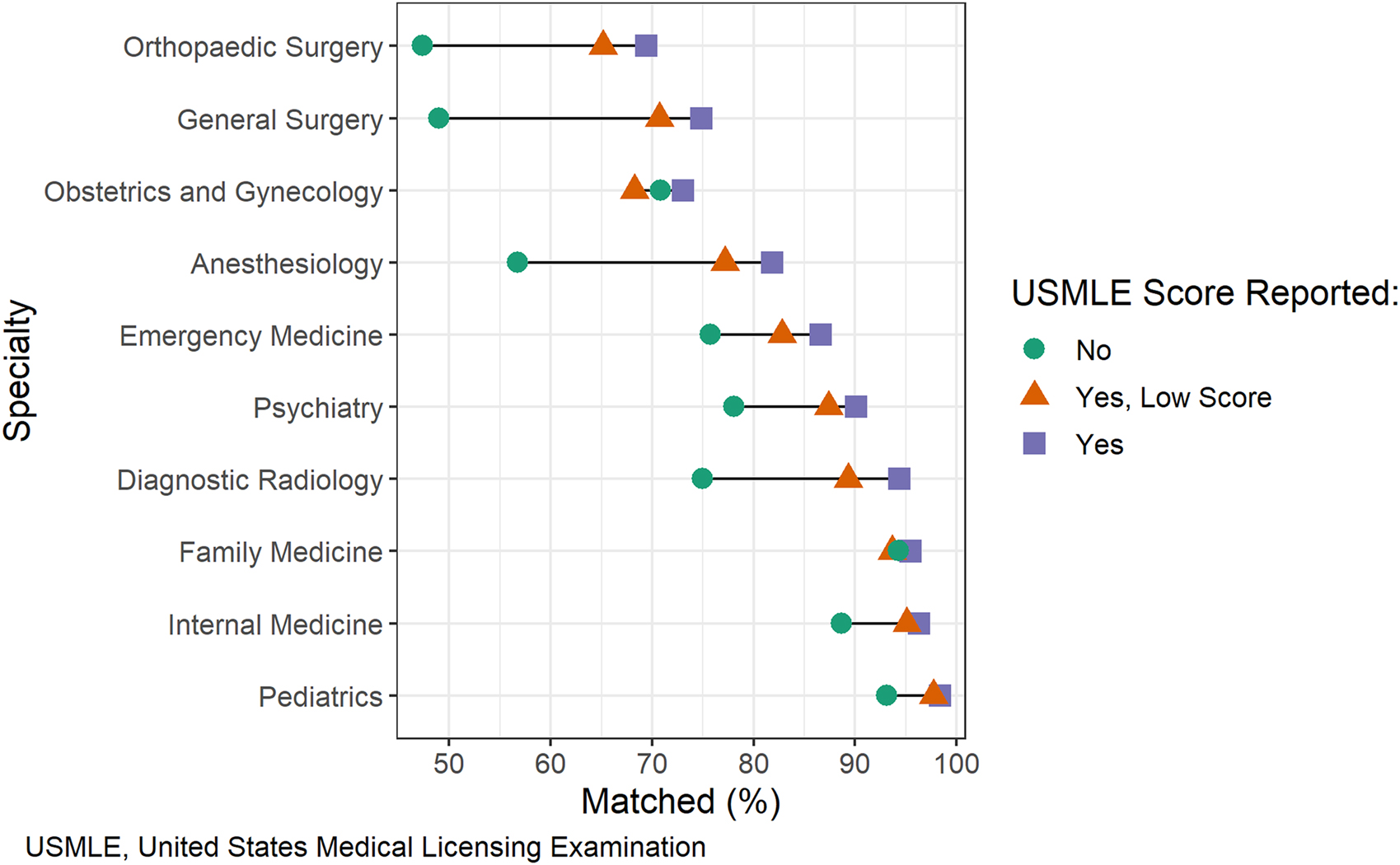

In 2020, 6,581 senior osteopathic students submitted rank order lists. A total of 6,055 (92%) of them gave consent for NRMP research [9]. The 10 specialties to which students applied most were Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, Emergency Medicine, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, Anesthesiology, General Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Diagnostic Radiology, and Orthopedic Surgery. The proportion of senior osteopathic students who reported taking the USMLE Step 1 ranged from 30.8 to 92.3% across the examined specialties (Table 2). The proportion of matched senior osteopathic students who reported taking the USMLE Step 1 was greater than the proportion who matched without the test across all 10 specialties (Table 2 and Figure 1). In addition, the proportion of matched senior osteopathic students who reported low USMLE Step 1 scores was greater than the proportion who matched without the test for all specialties except for Family Medicine and for Obstetrics and Gynecology (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Percent of senior osteopathic students matching with and without the USMLE Step 1 in 2020.

| Specialty | Reported taking the USMLE/applied, %a | Reported taking the USMLE | Reported a low USMLE scoreb | No reported USMLE score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matched/total, % | Matched/total, % | Matched/total, % | ||

| Internal medicine | 814/1308 (62.2) | 784/814 (96.3) | 468/492 (95.1) | 438/494 (88.7) |

| Family medicine | 375/1219 (30.8) | 358/375 (95.5) | 208/222 (93.7) | 796/844 (94.3) |

| Emergency medicine | 561/759 (73.9) | 486/561 (86.6) | 279/337 (82.8) | 150/198 (75.8) |

| Pediatrics | 247/467 (52.9) | 243/247 (98.4) | 173/177 (97.7) | 205/220 (93.2) |

| Psychiatry | 182/351 (51.9) | 164/182 (90.1) | 104/119 (87.4) | 132/169 (78.1) |

| Anesthesiology | 341/378 (90.2) | 279/341 (81.8) | 203/263 (77.2) | 21/37 (56.8) |

| General surgery | 199/250 (79.6) | 149/199 (74.9) | 111/157 (70.7) | 25/51 (49.0) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 215/287 (74.9) | 157/215 (73.0) | 86/126 (68.3) | 51/72 (70.8) |

| Diagnostic radiology | 143/155 (92.3) | 135/143 (94.4) | 67/75 (89.3) | 9/12 (75.0) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 144/163 (88.3) | 100/144 (69.4) | 71/109 (65.1) | 9/19 (47.4) |

-

USMLE, United States Medical Licensing Examination. aTotal applied derived from the number of applicants to each specialty who provided consent for National Residency Match Program (NRMP) research and excludes those who did not report taking the Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination (COMLEX-USA) Level 1. bSenior osteopathic students in the NRMP reported USMLE Step 1 score ranges including or below the mean for their specialty.

A dumbbell plot comparing the proportions of matched senior osteopathic students by reported USMLE Step 1 completion status stratified by specialty.

Nevertheless, reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 was associated with matching for those who applied to Internal Medicine (OR 3.3 [95% confidence interval 2.07 to 5.48]), Emergency Medicine (2.1 [1.35 to 3.17]), Pediatrics (4.4 [1.38 to 18.63]), Psychiatry (2.5 [1.34 to 4.98]), Anesthesiology (3.4 [1.57 to 7.32]), and General Surgery (3.1 [1.56 to 6.14]) (Table 3). After repeating the analysis with only senior osteopathic students who reported low USMLE Step 1 scores, the association remained significant for those who applied to Internal Medicine (2.5 [1.49 to 4.28]), Anesthesiology (2.6 [1.17 to 5.54]), and General Surgery (2.5 [1.24 to 5.04]) (Table 3).

Odds ratios for matching as a senior osteopathic student who reported taking vs did not report taking the USMLE Step 1 in 2020.

| Specialty | Reported taking the USMLE | Reported a low USMLE score |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI)a | |

| Internal medicine | 3.3 (2.07–5.48) | 2.5 (1.49–4.28) |

| Family medicine | 1.3 (0.71–2.39) | 0.9 (0.47–1.8) |

| Emergency medicine | 2.1 (1.35–3.17) | 1.5 (0.98–2.42) |

| Pediatrics | 4.4 (1.38–18.63) | 3.2 (0.98–13.31) |

| Psychiatry | 2.5 (1.34–4.98) | 1.9 (0.98–4.02) |

| Anesthesiology | 3.4 (1.57–7.32) | 2.6 (1.17–5.54) |

| General surgery | 3.1 (1.56–6.14) | 2.5 (1.24–5.04) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 1.1 (0.58–2.08) | 0.9 (0.44–1.74) |

| Diagnostic radiology | 5.5 (0.81–28.85) | 2.7 (0.40–14.55) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 2.5 (0.85–7.52) | 2.1 (0.69–6.29) |

-

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; USMLE, United States Medical Licensing Examination. aSenior osteopathic students in the National Residency Match Program (NRMP) reported USMLE Step 1 score ranges including or below the mean for their specialty. BOLD = Confidence interval does not include one.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of published 2020 NRMP match results for senior osteopathic students who applied to the 10 most popular specialties, we found that reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 was associated with matching for those who applied to Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, Anesthesiology, and General Surgery. Furthermore, after limiting the analysis to those with low USMLE Step 1 scores, this association remained significant for those who applied to Internal Medicine, Anesthesiology, and General Surgery (Table 3).

These results are consistent with previous work. In a study of 350 osteopathic applicants to emergency medicine residency programs from the 2010 to 2011 application season, those who took the USMLE were more likely to match than those who did not take it, 126/208 (61%) vs 55/142 (39%), respectively [11]. In addition, performance on the USMLE Step 1 has been associated with matching into preferred specialties for osteopathic applicants [12].

Interestingly, the association between taking the USMLE Step 1 with matching was inconsistent between specialties (Table 3). For example, reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 was not associated with matching for those who applied to Family Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Diagnostic Radiology, and Orthopedic Surgery (Table 3). Therefore, completing the USMLE Step 1 may not improve match outcomes among all specialties. However, reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 did not appear to harm match outcomes across the examined specialties, even with a low score (Table 3). Since most students change their specialty pursuits during medical school [13, 14], the association between completion of the USMLE Step 1 and matching for multiple specialties may outweigh the risk of performing poorly on the test for many osteopathic students.

However, the USMLE Step 1 and COMLEX-USA Level 1 are transitioning to pass/fail score reports [15, 16]. It is unknown how this change will alter the value of other aspects of the medical student application [17, 18]. However, osteopathic students will likely benefit from this change because it removes the necessity to obtain a competitive score on the USMLE Step 1, therefore lowering the threshold to take the test. Furthermore, as our results suggest, senior osteopathic students who reported taking the USMLE Step 1 were more likely to match into several specialties regardless of score (Table 2).

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations. First, it is a secondary analysis of published match data at the specialty level. Therefore, we could not adjust for confounding variables at the applicant level. For example, COMLEX-USA scores may be higher in osteopathic students who take the USMLE [4]. Therefore, applicants who take the USMLE Step 1 may be more competitive than those who do not take the test, which might confound our results. Second, these data are self-reported by applicants; however, the NRMP verified 89% of USMLE Step 1 scores with the osteopathic medical schools [9]. Third, specialties like Diagnostic Radiology and Orthopedic Surgery had few applicants who did not report taking the USMLE Step 1, and these small numbers may have biased the results for those specialties (Table 2). Lastly, the value of taking the USMLE varies between applicants. Many factors determine a successful match, including nonobjective variables like letters of recommendation and interpersonal relationships. Each senior osteopathic student should consider their whole application when determining their competitiveness.

Conclusions

Among senior osteopathic students who applied to the 10 most popular specialties in the 2020 NRMP Match, reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 was associated with matching for those who applied to Internal Medicine, Emergency Medicine, Pediatrics, Psychiatry, Anesthesiology, and General Surgery. After limiting the analysis to senior osteopathic students with low USMLE Step 1 scores, this association remained significant for those who applied to Internal Medicine, Anesthesiology, and General Surgery.

-

Research funding: None reported.

-

Author contributions: D.A.N. and K.M.B. provided substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; all authors drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version of the article to be published; and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

-

Competing interests: None reported.

References

1. State specific requirements for initial medical licensure. Federation of State Medical Boards. https://www.fsmb.org/step-3/state-licensure/ [Accessed 13 Dec 2021].Search in Google Scholar

2. Myths and misconceptions - match 2020. NBOME. https://www.nbome.org/editorial/myths-and-misconceptions-match-2020/ [Accessed 12 Sep 2021].Search in Google Scholar

3. Kane, KE, Yenser, D, Weaver, KR, Barr, GCJr, Goyke, TE, Quinn, SM, et al.. Correlation between United States medical licensing examination and comprehensive osteopathic medical licensing examination scores for applicants to a dually approved emergency medicine residency. J Emerg Med 2017;52:216–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.060.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Smith, T, Kauffman, M, Carmody, JB, Gnarra, J. Predicting osteopathic medical students’ performance on the United States medical licensing examination from results of the comprehensive osteopathic medical licensing examination. Cureus 2021;13: e14288. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.14288.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Lee, AS, Chang, L, Feng, E, Helf, S. Reliability and validity of conversion formulas between comprehensive osteopathic medical licensing examination of the United States level 1 and United States medical licensing examination step 1. J Grad Med Educ 2014;6:280–3. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-13-00302.1.Search in Google Scholar

6. Hasty, RT, Snyder, S, Suciu, GP, Moskow, JM. Graduating osteopathic medical students’ perceptions and recommendations on the decision to take the United States Medical Licensing Examination. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2012;112:83–9.Search in Google Scholar

7. The grading policy for medical licensure examinations H-275.953. American Medical Association (AMA). https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/H-275.953?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-1931.xml [Accessed 06 Apr 2021].Search in Google Scholar

8. Turner, M. Advocacy to improve access to training opportunities for DO students. The DO. https://thedo.osteopathic.org/2021/07/advocacy-to-improve-access-to-training-opportunities-for-do-students/ [Accessed 13 Dec 2021].Search in Google Scholar

9. National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: senior students of U.S. DO medical schools, 2020. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

10. 45 CFR 46. HHS Office for Human Research Protections. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html [Accessed 13 Dec 2021].Search in Google Scholar

11. Weizberg, M, Kass, D, Husain, A, Cohen, J, Hahn, B. Should osteopathic students applying to allopathic emergency medicine programs take the USMLE Exam? West J Emerg Med 2014;15:101–6. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2013.8.16169.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Mitsouras, K, Dong, F, Safaoui, MN, Helf, SC. Student academic performance factors affecting matching into first-choice residency and competitive specialties. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1669-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Parzuchowski, A. Right before match day, I changed specialties. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/right-match-day-i-changed-specialties [Accessed 13 Dec 2021].Search in Google Scholar

14. Compton, MT, Frank, E, Elon, L, Carrera, J. Changes in U.S. medical students’ specialty interests over the course of medical school. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1095–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0579-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Chaudhry, HJ, Katsufrakis, PJ, Tallia, AF. The USMLE step 1 decision: an opportunity for medical education and training. JAMA 2020;323:2017–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. COMLEX-USA level 1 to eliminate numeric scores. NBOME. https://www.nbome.org/news/comlex-usa-level-1-to-eliminate-numeric-scores/ [Accessed 07 Oct 2021].Search in Google Scholar

17. Bennett, WC, Parton, TK, Beck Dallaghan, GL. The necessity of uniform USMLE step 1 Pass/fail score reporting. Acad Med 2021;96:163. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003805.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Cangialosi, PT, Chung, BC, Thielhelm, TP, Camarda, ND, Eiger, DS. Medical students’ reflections on the recent changes to the USMLE step exams. Acad Med 2021;96:343–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003847.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Dhimitri A. Nikolla et al., published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Behavioral Health

- Commentary

- Overcoming reward deficiency syndrome by the induction of “dopamine homeostasis” instead of opioids for addiction: illusion or reality?

- General

- Original Article

- The association between operating margin and surgical diversity at Critical Access Hospitals

- Medical Education

- Brief Report

- Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020

- Commentary

- Addressing disparities in medicine through medical curriculum change: a student perspective

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Original Article

- Cervical cancer screening among women with comorbidities: a cross-sectional examination of disparities from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Review Article

- Review of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder

- Clinical Image

- Idiopathic linear IgA bullous dermatosis with mucosal involvement

- Letters to the Editor

- Standardization of osteopathic manipulative treatment in telehealth settings to maximize patient outcomes and minimize adverse effects

- Response to “Standardization of osteopathic manipulative treatment in telehealth settings to maximize patient outcomes and minimize adverse effects”

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Behavioral Health

- Commentary

- Overcoming reward deficiency syndrome by the induction of “dopamine homeostasis” instead of opioids for addiction: illusion or reality?

- General

- Original Article

- The association between operating margin and surgical diversity at Critical Access Hospitals

- Medical Education

- Brief Report

- Reported completion of the USMLE Step 1 and match outcomes among senior osteopathic students in 2020

- Commentary

- Addressing disparities in medicine through medical curriculum change: a student perspective

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Original Article

- Cervical cancer screening among women with comorbidities: a cross-sectional examination of disparities from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- Public Health and Primary Care

- Review Article

- Review of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder

- Clinical Image

- Idiopathic linear IgA bullous dermatosis with mucosal involvement

- Letters to the Editor

- Standardization of osteopathic manipulative treatment in telehealth settings to maximize patient outcomes and minimize adverse effects

- Response to “Standardization of osteopathic manipulative treatment in telehealth settings to maximize patient outcomes and minimize adverse effects”