Abstract

Explicitation is a key concept in translation studies referring to turning what is implicitly narrated in a source text into explicit narration in a target text; it has been widely studied from different aspects across language pairs and genres. However, while most previous studies investigate explicitation through a few indicators of explicitness, most of which are specific logical links and connectives, textual explicitness encompasses far beyond these. To date, little attention has been paid, especially in literary translation, to semantic explicitation, which is realized through cohesive chains in textual development. Since cohesive chains represent the development of events and characters throughout the text, it is assumed the more there are of them, the more tangible a text is in realizing its meaning within its context. This research, therefore, sets out to investigate the cohesive chains in a Chinese classic novel, Hong Lou Meng, and in its two English translations, The Dream of the Red Mansions and A Story of the Stone, with an emphasis on how the texts are manifested as narratives in the respective contexts with different readers. It has found a trend of explicitation in translation from Chinese source text to English target texts in terms of the numbers of cohesive chains and the lexical items forming the chains. It has also found differences in the distribution of different types of cohesive chains (identity chains and similarity chains), which represent distinctive patterns of realizing the context in each text. The interpretation of these different stylistic features in narrative reflects both typological differences and translators’ choices.

1 Cohesive chains

Readers understand the new content of a text through the context created by what has been narrated before (Widdowson 2007: 46). Along this reading process, they are guided by deictic expressions to follow the character or narrator’s perspective (Stockwell 2002: 47). These deictic expressions are “one of the most important characteristics of literary discourse” in the form of “cohesion” (Traugott and Pratt 2008: 41). Cohesion accounts for the essential semantic relations that enable a text to be defined as a whole (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 13). When it comes to cohesion in translated text, Newmark (1987: 295) went so far as to argue that cohesion “has always appeared to [be] the most useful constituent of discourse analysis or text linguistics applicable to translation”. Patterns of cohesion are mainly manifested in the form of cohesive chains in the text (Baker 1997; Hatim and Mason 1990). These cohesive chains serve as straightforward devices “for tracking the semantic connectedness between words in a text” (Butt et al. 2010: 272). By relating cohesive devices across sentences to make “a semantic unit” of a text, cohesive chains contribute to its “unity of meaning in context” (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 293). In other words, as a text is created in its socio-cultural context (Halliday 1973; Halliday and Hasan 1989 [1985]), the way the meaning of the text is realized within its context can be investigated through the cohesive chains.

Hasan (1984) defines two types of cohesive chain: identity chain and similarity chain (205–206). Identity chain (IC) is one in which each item refers to the same referent (Hasan 1984: 205). It comprises “all the references to a key character in a text, including names, lexical expressions and pronouns” (Emmott 2002: 92), for instance, a specific character named Baoyu (宝玉 Bǎoyù) in the present data analysed. An IC is text-bound and is traceable only within the text, so it is the realization of the context of situation of the specific text. The IC is indispensable for textual construction because the repeated mention of the events, entities and circumstances needs to be made specific (Hasan 1984: 205–206). For example, in the present data certain characters of the story being repetitively mentioned by simple repetitions of names and demonstrative references throughout the narration, can be traced by ICs. On the other hand, a similarity chain (SC) is formed out of the relation of either substantive or elliptical cohesion (i.e. substitution and ellipsis) or lexical cohesive categories, such as repetition, synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy and meronymy (Hasan 1984: 206). Essentially, an SC refers to entities or events in the same category or class, but not necessarily identical items, and therefore it is not text-bound and can be traced in any text (Hasan 1984: 206). For example, a group of synonymous English words in the present corpus – cry, sob, lament – can form a similarity chain of a human behavior that is commonly considered to be a manifestation of sadness in any text by English readers. Thus, SCs can be viewed as the realization of the context of culture.

Cohesive chains relate clauses through experiential meaning[1] (Cloran et al. 2005: 651), and they can indicate the development of events and characters throughout the text, thus serving as textual strings concerning the “context-construing work” (Halliday and Hasan 1989 [1985]: 115) of a text. The more there are of them, the more tangible a text is in realizing its meaning within its context. Thus, the explicitation of cohesive chains to be investigated through their numbers and patterns is of vital importance, as it reflects how a translation realizes its context as well as how it is designed to guide the readers through the narrative.

2 Explicitation in translation

Cohesive chains can be used as parameters of narration in translation. Readers draw on their familiarity with seemingly similar narrative experiences and other background knowledge that the previous text provides to enrich the explicit textual evidence and to predict how the story goes (Toolan 2009). Therefore, the explicitness of cohesive chains that represent the characters or events in the narrative can reveal the different expectations of readership in an original text and a translation. Cohesive explicitness falls under a key issue in translation studies: ‘explicitation’, which is “an overall tendency to spell things out rather than leave them implicit” (Baker 1996: 180). Explicitation was first introduced by Vinay and Darbelnet (1958: 9) as a method in translation by introducing into the target language (TL) what are implicit, but clear in the context of situation, in the source language (SL). Blum-Kulka (1986) subsequently proposed explicitation as an inherent result of the translation process. Despite some scepticism about the inherent nature of explicitation in translation (cf. Becher 2010), the phenomenon of explicitation has been observed in corpus-based translation studies across different languages and genres (cf. Baker 1996; Hansen-Schirra et al. 2007; Jiménez-Crespo 2011; Marco 2012).

Explicitation in translation has been examined with different focuses across languages, such as connectives in German (Becher 2011), causal connectives in English and French (Zufferey and Cartoni 2014), logical links from Russian to Swedish (Dimitrova 2005), clausal relations in Finnish and English (Puurtinen 2004), and conjunctions from Chinese to English (Chen 2004). These studies have largely focused on explicitation manifested in the form of explicit cohesive connectives or conjunctions in translation; however, we argue that the cohesive explicitness extends far beyond logical links and connectives. In the current research, explicitness is measured by cohesive chains and relevant tokens that form those chains. The numbers of cohesive chains and relevant tokens will be compared and contrasted to determine whether explicitation occurs in translation as well as its type and extent.

Despite the rich studies of explicitation in translation, there remains a gap between explicitation and the semantic realization of cohesive chains. As far as the present authors are aware of, there have been only a few studies investigating the cohesive chains in Chinese texts (cf. Wu and Lai 2011). Moreover, despite the cohesive chains being a significant indicator of semantic explicitness, there have been no studies on the explicitation of cohesive chains in literary translation.

This article, therefore, provides an empirical study on cohesive chains in translation from Chinese to English. It extends the current translation studies on explicitation by investigating how cohesive chains are manifested in the translation of an eighteenth century classical Chinese masterpiece, Hong Lou Meng (Cao 1982) (红楼梦 Hóng Lóu Mèng, written by Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹 Cáo Xueqín), into two contemporary English versions, A Dream of Red Mansions (Cao 1978) and The Story of the Stone (Cao 1973), and whether the cohesive chains reveal a trend of explicitation in both translations in terms of semantic realization. It also seeks to explore some linguistic and cultural considerations behind the observed explicitation.

Unlike the previous translation studies of cohesive explicitation, most of which examine a small set of specific connectives in large corpora, this research moves beyond the surface indicators of explicitness to conduct a more in-depth analysis of semantic threads as indicators of explicitness in translation. In doing so, we propose a new methodology to investigate the phenomenon of explicitation in translation via cohesive chains.

3 Data and methodology

The study is conducted by analysing a classical Chinese novel Hong Lou Meng (Cao 1982) (People’s Literature Publishing House version), hereinafter referred to as Source Text (ST) or HLM, and its two most famous contemporary translated English versions: A Dream of Red Mansions by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang in 1978, and The Story of the Stone by David Hawkes in 1973, hereinafter referred to as Target Text 1 (TT1) and Target Text 2 (TT2) respectively.

HLM is one of the Four Great Classical Novels (四大名著 sì dà míngzhù) of Chinese literature. One of its uniqueness and innovativeness lies in the huge cast of characters and vivid narrative skills (Cao 1978: vii). Written in the eighteenth century, it demonstrates the author’s mastery of Chinese language at an excellent level; even after over 200 years, HLM continues to attract specialised scholarly attention to itself in the name of a scholarly field called Redology (红学 hóngxué) – the academic study of Hong Lou Meng, and to provide rich resources for new linguistic studies of modern Chinese (cf. Wang 1985 [1959]). The two English translations were both produced in the 1970s; the TT1 was translated by Yang Xianyi, a native Chinese speaker, and his wife Gladys Yang, who is a native speaker of English, whereas the TT2 was translated by a native English speaker. This difference presents interesting contrasts in terms of translator background since the target language was not the first language (L1) of Yang Xianyi of TT1 but was the L1 for the translator of TT2. Both versions stand out for their high literary value (Li et al. 2011), attracting much attention from translation scholars, sinologists and Redologists. The numerous comparisons of Yangs’ and Hawkes’ versions (cf. Liu 2010, 2012; Zhang and Liu 2016) have been conducted from aesthetic, literary and linguistic perspectives, but rarely from a narrative, stylistic perspective.

Due to the perceived temporal, spatial, linguistic and cultural gaps between the ST and the two TTs, cohesive chains, as semantic threads of a text, have presumably been necessarily explicitated to bridge such gaps to bring the ST closer to TT readers. The stylistic patterns of cohesive chains in each text contribute to the readers’ understanding of the story.

As for data selection in this analysis, to strike a balance between representativeness and in-depth textual analysis, three chapters (i.e. Chapter 1, Chapter 2 and Chapter 39) from each of the three versions have been analysed. The first two Chapters introduce the background of how the story will develop, and Chapter 39 includes most of the important characters in the novel. The selected ST and TTs altogether constitute a sizeable corpus of 13,055 Chinese words[2] and 33,686 English words.

The analysis was conducted in two steps: 1) to identify cohesive chains by linking cohesive devices in the texts, and 2) to analyse and compare the cohesive chains in different texts. Based on these steps, this research aims to answer the questions as to whether explicitation has occurred in both translations, how cohesive chains may exhibit explicitation in translation, what the differences of explicitation in translations may imply, and whether some cultural and stylistic explanations can be provided for the potential explicitation in translation and differences between translations.

3.1 Cohesive chains investigated in a small pilot study

To illustrate explicit analysis of cohesive chains formation in the ST and TTs, a small extract from Chapter 1 has been provided and analysed below.

Extract 1

Note: taken from Chapter One of the novel, Extract 1 provides a mythical account of the origin of a precious stone, which is essential in driving the development of the story, as the stone descends to the human world and bears witness to the life of the main character, Baoyu, throughout the story. The Chinese ST has been tabulated below and divided into clauses, each supplemented with Latin transliteration using Pinyin[3]; an English translation is provided by the first author of this article. The parallel TT1 and TT2 are provided afterwards.

| ST | |||||

| 1 | 原来 | 女娲氏 | 炼石 | 补天 | 之时, |

| Yuánlái | nǚwāshì | liànshí | bǔtiān | zhīshí, | |

| Literal translation (LT): When the Goddess Nüwa was repairing the sky, | |||||

| 2 | (女娲氏) 4 于大荒山无稽崖 炼成 高经十二丈、 | |

| Yúdàhuāngshānwújīyá liànchéng Gāojīngshí’èrzhàng, | ||

| 方经二十四丈顽石 | 三万六千五百零一块。 | |

| fāngjīngèrshísìzhàngwánshí | sānwànliùqiānwǔbǎilíngyīkuài. | |

| LT: at the Baseless cliff of The Great [4]Waste Mountain, (she) tempered thirty six thousand five hundred and one blocks of stone, each one hundred third feet high and two hundred sixty feet square. | ||

| 3 | 娲皇氏 | 只用了 | 三万六千五百块, | |

| Wāhuángshì | zhǐyòngle | sānwànliùqiānwǔbǎikuài | ||

| LT: The Goddess Nüwa only used thirty six thousand five hundred blocks, | ||||

| 4 | 单单 | 剩了 | 一块 | 未用, |

| Dāndān | shèngle | yíkuài | wèiyòng, | |

| LT: leaving only one block unused, | ||||

| 5 | 弃在 | 青埂峰下。 | ||

| Qìzài | qīnggěngfēngxià | |||

| LT: and (she) threw it at the foot of the Blue Ridge Peak. | ||||

| 6 | 谁知 | 此石 | 自经煅炼之后, | |

| Shuízhī | cǐshí | zìjīng duànliàn zhīhòu | ||

| LT: Who would have known that this stone after being tempered, | ||||

| 7 | (此石)灵性 | 已通, | ||

| Língxìng | yǐtōng | |||

| LT: has possessed magical power. | ||||

| 8 | (此石)因见 | 众石 | 俱得 | 补天, |

| Yīnjiàn | zhòngshí | jùdé | bǔtiān | |

| LT: Seeing that all the other blocks of stone are used to repair the sky, | ||||

| 9 | 独自己 | 无材 | 不堪入选, | |

| Dúzìjǐ | wúcai | bùkānrùxuǎn | ||

| LT: only itself was not chosen for lack of talent, | ||||

| 10 | (此石)遂 | 自怨 | 自叹, | |

| Suì | zìyuàn | zìtàn | ||

| LT: it grumbled and sighed, | ||||

| 11 | (此石)日夜 | 悲号 | 惭愧。 | |

| Rìyè | bēiháo | cánkuì | ||

| LT: lamenting day and night. | ||||

| TT1 | ||||

| 1 | When the goddess Nu Wa melted down rocks | |||

| 2 | to repair the sky, | |||

| 3 | at Baseless Cliff in the Great Waste Mountain she made thirty-six thousand five hundred and one blocks of stone, each a hundred and twenty feet high and two hundred and forty feet square. | |||

| 4 | She used only thirty-six thousand five hundred of these | |||

| 5 | and (she) threw the remaining block down at the foot of Blue Ridge Peak. | |||

| 6 | Strange to relate, this block of stone after tempering had acquired spiritual understanding. | |||

| 7 | Because all its fellow blocks had been chosen to mend the sky | |||

| 8 | and it alone rejected, | |||

| 9 | it lamented day and night in distress and shame. | |||

| TT2 | ||||

| 1 | Long ago, when the goddess Nu-wa was repairing the sky, | |||

| 2 | she melted down a great quantity of rock | |||

| 3 | and, on the Incredible Crags of the Great Fable Mountains, (she) moulded the amalgam into thirty-six thousand, five hundred and one large building blocks, | |||

| 4 | each measuring seventy-two feet by a hundred and forty-four feet square. | |||

| 5 | She used thirty-six thousand five hundred of these blocks in the course of her building operations, | |||

| 6 | leaving a single odd block unused, | |||

| 7 | which lay, all on its own, at the foot of Greensickness Peak in the aforementioned mountains. | |||

| 8 | Now this block of stone, <clause 9> possessed magic powers. | |||

| 9 | having undergone the melting and moulding of a goddess, | |||

| 10 | It could move about at will | |||

| 11 | and (it) could grow or shrink to any size it wanted. | |||

| 12 | Observing that [[all the other blocks had been used for celestial repairs and that it was the only one to have been rejected as unworthy]],[5] | |||

| 13 | it became filled with shame and resentment | |||

| 14 | and (it) passed its days in sorrow and lamentation. | |||

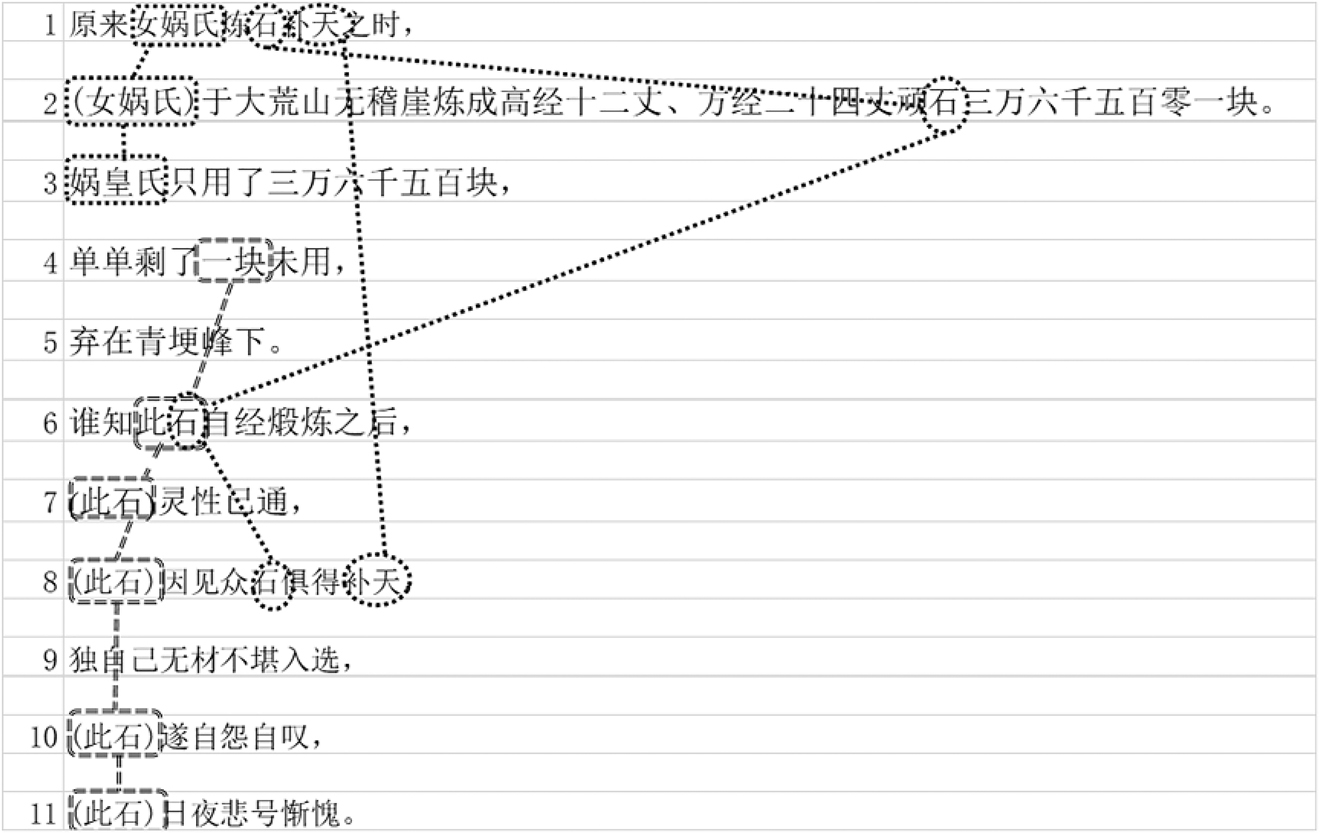

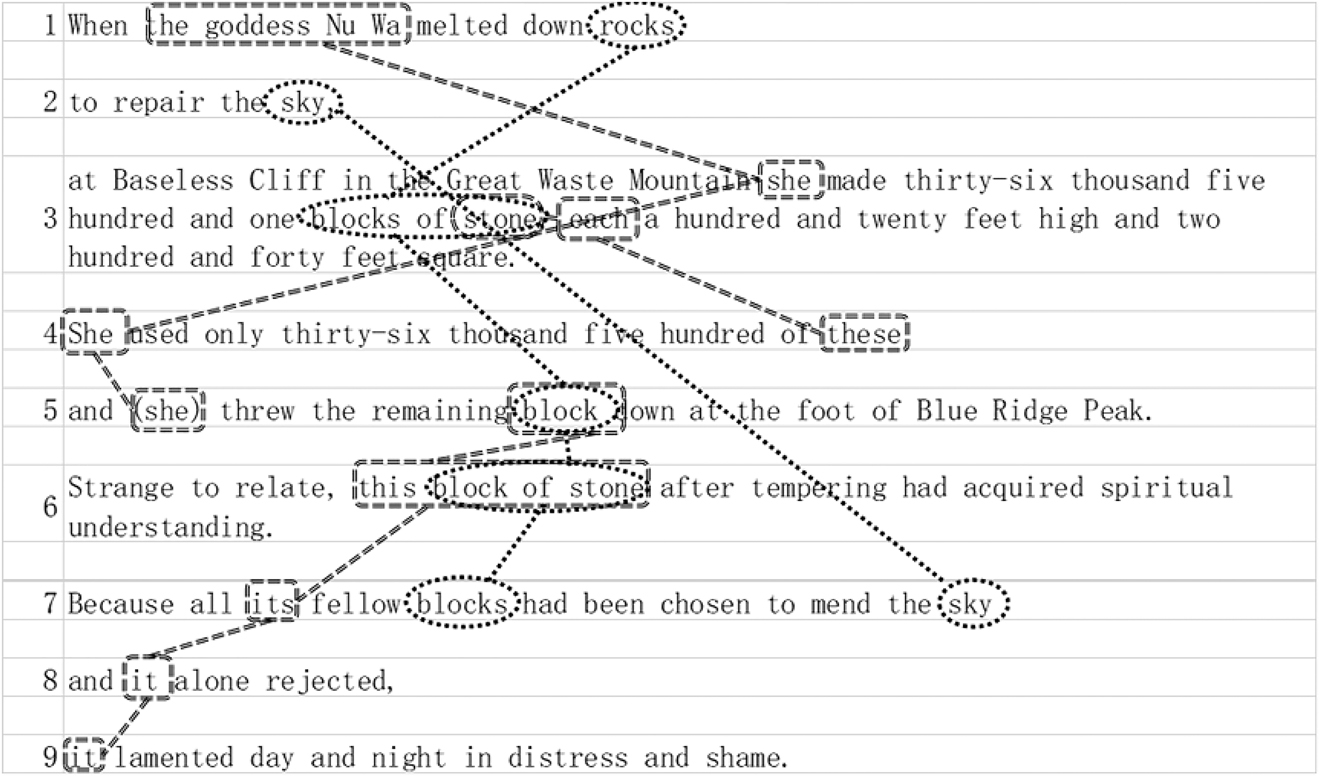

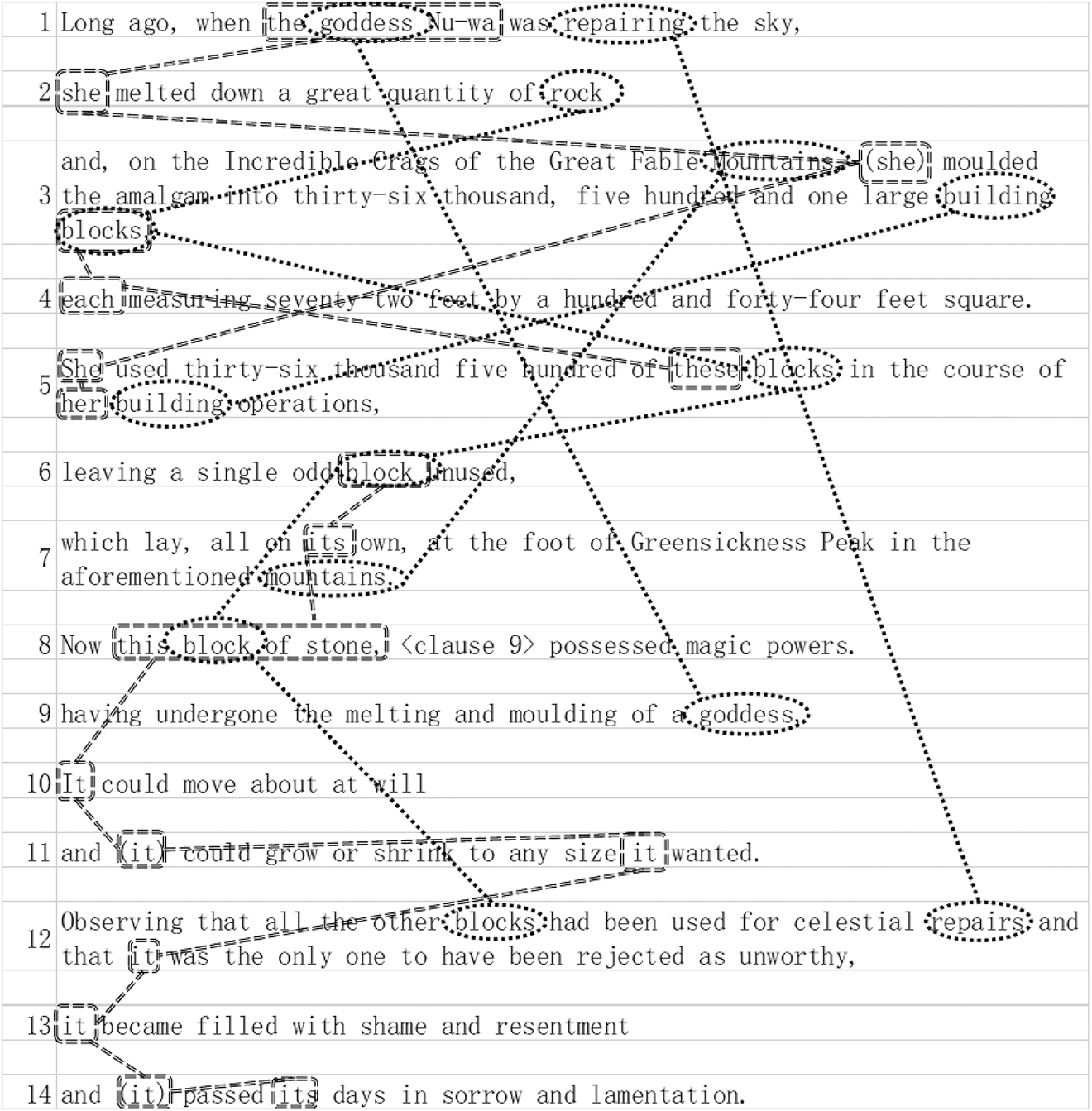

By tying the cohesive devices and their interpretative sources, i.e. the referent of a cohesive device (Hasan 1984: 190), or by linking similar lexical items, cohesive chains are identified and visualised throughout the text, as shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3 below. To be specific, the pronominal references such as the definite article the and demonstratives such as this and that all refer to specific characters, entities, events and so on alike in the text, therefore, they form identity chains that are the realization of “topical” unity of a text through those pronominal references (Hasan 1984: 184). On the other hand, similarity chains “are a realization of particular portions of semantic fields [;…] they reflect the generic status of the text, and […] contribute to its individuality” (Hasan 1984: 206). In Extract 1, some references and semantically equivalent items form identity chains by referring to the same referent, whereas some other items from the same category or class form similarity chains, which represent the generic features of the text and associate the text with its context of culture. In Figures 1, 2, and 3, the identity chains are visualised in —, while the similarity chains are visualised in ……

Cohesive chains analysis of the ST.

Cohesive chains analysis of the TT1.

Cohesive chains analysis of the STT2.

The process of chain formation can be shown with a few examples. In the ST, the —— identity chain 11e [6] –10e–8e–7e–6–4s refers to a stone which can be traced back from the elliptical subject of 此石 cǐshí ‘this stone’ in clause 11 to the same subject ellipsis in clause 10, 8 and 7, to 此石cǐshí ‘this stone’ in clause 6 and to 一块 yīkuài ‘one stone’ in clause 4. Elliptical Subjects had been recovered prior to the chain formation for visualization. All the cohesive devices in these clauses form an IC, referring to 顽石 wánshí ‘one block of stone’ in the text.

In the TT1, the specific block of stone has been referred to as the block in clause 5, as the demonstrative this in clause 6, as the pronominal its in clause 7, and as it in clauses 8 and 9, thus forming an IC 9–8–7–6–5. Apart from this specific block, there are other stones mentioned in the TT1 in chain 4–3–3, referred to as these in clause 4, each in clause 3 and blocks of stone in clause 3. Moreover, the reference of goddess can be traced from the elliptical subject in clause 5 to she in clause 4 and 3, and then to the goddess Nu Wa in clause 1, forming another IC 5e–4–3–1.

Similarly, in the TT2, the block in clause 6 is referred to throughout the text using pronouns and demonstrative reference, from its in clause 7, to this in clause 8, to it in clause 10, and subject ellipsis of it in clause 11, to it in clause 11, 12, 13 and another subject ellipsis in clause 14 till the pronominal its in clause 14. This chain is represented as 14–14e–13–12–11e–10–8–7–6. The goddess in the TT2 is referred to in the chain 5–5–3e–2–1 with pronominal reference she and possessive reference her.

All these identity chains form strings that concern specific entities in the text, the topical development of which contributes to the unity of a text. The investigation of whether these ICs are maintained or shifted in translation will thus be indicative of the development of the general topics in different texts, and of readership design in the translations.

On the other hand, formed out of lexical cohesive categories, similarity chains can also be traced within Extract 1. For instance, in the ST, 石 shí ‘stone’ in clauses 1, 2, 6, 8 are linked via the relation of semblance, referring to the general solid mineral material of stone, not necessarily to the specific blocks used for repairing the sky or the leftover block in this context. In the TT1, the simple repetitions of the sky in clause 2 and 7 refer to the same sky, which is applicable in any text. In the TT2, Green sickness Peak and mountains in clause 7 are related to the Incredible Crags of the Great Fable Mountains in clause 3 via meronymy.

Referring respectively to the same entity within a specific text or a similar entity within a specific genre, these identity and similarity chains together construct the “logical skeleton” (Butt et al. 2010: 273) of meanings within a text. By connecting cohesive devices, cohesive chains can link items of any size at any distance (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014: 607)”. The implicitness or explicitness of this logical skeleton shows the way in which the text realizes its meaning. The denser these links, the more explicit a text is. Considering typological differences between Chinese and English, we measure the density of cohesive chains per clause rather than per certain number of words. Impressionistically, Figures 1, 2, and 3 show denser chain formation in the TTs. This has been confirmed in Table 1 below. First, both TTs have more cohesive chains than the ST. Second, both TTs display higher numbers of chains per clause. They suggest a trend of explicitation in translation.

The use of cohesive chains in Extract 1.

| No. of chains | ST | TT1 | TT2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity chain (IC) | 1 | 25% | 3 | 60% | 3 | 37.5% |

| Similarity chain (SC) | 3 | 75% | 2 | 40% | 5 | 62.5% |

| Total | 4 | 100% | 5 | 100% | 8 | 100% |

| No. of clause | 11 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Chain per clause | 0.36 | 0.56 | 0.57 | |||

3.2 Relevant tokens

Apart from the number of cohesive chains, which does not reflect the length of chains, the explicitness of each text is also reflected by the number of cohesive devices that form cohesive chains. According to Halliday and Hasan (1989 [1985]: 93), “all tokens that enter into identity or similarity chains” are defined as relevant tokens (hereafter referred as RT). For example, in Figure 2, there are four RTs that form the IC of the goddess: the goddess Nu Wa, she, she, (she). The RTs in chain formation serve as “patterns that gradually appear in the course of the unfolding” (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014: 601) of a text can be viewed as explicitness indicators dotted throughout the text. They contribute to readers’ perception and interpretation of the text (Morris and Hirst 2006: 41). The more RTs there are, the more explicit the text can be considered. As text sizes vary, the ratio of RTs to the number of words and clauses in a text will be considered a direct exhibition of the explicitness of cohesive chains.

Take ICs in Figures 1, 2, and 3 as an example. In Figure 1, the IC 11e [7] –10e–8e–7e–6–4s referring to “the stone” contains 6 relevant tokens in driving “the development of the content of the text” (Hasan 1984: 199). In Figure 2, the referents to “the stone” form an IC 9–8–7–6–5, which contains 5 relevant tokens: block in clause 5, this in clause 6, its in clause 7, and it in clause 8 and 9. In Figure 3, the referents to “the stone” make an IC 14–14e–13–12–11e–10–8–7–6, with altogether 9 relevant tokens: block in clause 6, its in clause 7, this block of stone in clause 8, It in clause 10, (it) and it in clause 11, it in clause 12, it in clause 13 and (it) and its in clause 14. The different numbers of relevant tokens in the ICs referring to the stone shows that TT2 here has a higher degree of explicitness than the ST and TT1.

The total numbers of RTs in the three texts are shown in Table 2 below, which shows higher numbers of RT in both translations than in the ST.

Number and ratio of relevant tokens in Extract 1.

| ST | TT1 | TT2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant tokens (RT) | 15 | 19 | 32 |

| No. of clause | 11 | 9 | 14 |

| RT per clause | 1.36 | 2.11 | 2.28 |

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the different degrees of explicitness of cohesive chains in the ST and TTs may suggest that there is a trend of explicitation in translation. This is tested in the larger corpus in the next section.

4 Results

4.1 Cohesive chains in the texts

To compare how cohesive chains are manifested in the translations, all identity and similarity chains are identified in ST and TTs to examine how different texts realize their semantic meanings, as shown in Table 3.

The use of cohesive chains in the texts.

| No. of chains | ST | TT1 | TT2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity chain (IC) | 351 | 52.31% | 474 | 59.03% | 564 | 58.26% |

| Similarity chain (SC) | 320 | 47.69% | 329 | 40.97% | 404 | 41.74% |

| Total | 671 | 100% | 803 | 100% | 968 | 100% |

| No. of clauses | 808 | 677 | 719 | |||

| Chain per clause | 0.83 | 1.19 | 1.35 | |||

The numbers of ICs and SCs in the texts exhibit clear differences between the Chinese source text and the two English target texts as well as between the two target texts. The ST has the least overall number (671) of cohesive chains as well as IC (351) and SC (320). Firstly, while supposedly conveying the same ideational meaning as do the ST, both TTs have more cohesive chains than does the ST: 803 cohesive chains in the TT1 and 968 in the TT2 respectively. Accordingly, the three texts also show discrepancies in the percentages of the two types of cohesive chains. The ST has the lowest percentage of ICs, whereas the TT1 has the highest. This demonstrates that the ST has the strongest preference for SCs over ICs in developing semantic sequence, whereas the TT1 has the weakest. The two TTs show only less than 1% discrepancy in the ratio of ICs to SCs, but both differ considerably from the ST in the ratio. Secondly, the clauses that are linked by cohesive chains also show a trend of explicitation. From Table 3, we see that each chain on average connects 0.83 clause in the ST, while this number is 1.19 and 1.35 clauses respectively in TT1 and TT2. The explicitness displayed by the connection among clauses through cohesive chains in the three texts is in accordance with the different degrees of explicitness shown by the number of cohesive chains.

The considerably larger numbers of cohesive chains and chain per clause ratio in the two TTs show a trend of explicitation in both translations. As stated before, explicitation in this research is measured in terms of the explicit semantic strings, that is, the cohesive chains. However, the two translations also vary in the degree of explicitation. In general, the Chinese source text is the most implicit one, while Hawkes’ translation (TT2) is the most explicit one, and Yang’s version (TT1) is in between the ST and TT2 in terms of the instances of cohesive chains.

4.2 Relevant tokens in the texts

Cohesive chains reflect degrees of explicit semantic realization in translation, while the RTs that form these chains also contribute to this trend of explicitation. Table 4 below shows that the ST has the least number of RTs while the TT2 has the most.

Number of relevant tokens in the texts.

| ST | TT1 | TT2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant tokens (RT) | 2,667 | 3,105 | 4,058 |

| Word count | 13,055 | 14,512 | 18,174 |

| RT-word ratio | 20.41% | 21.40% | 22.33% |

| Clauses | 808 | 677 | 719 |

| RT per clause | 3.30 | 4.59 | 5.64 |

In accordance with the increasing numbers of RTs from the ST to the TTs, the percentages of them also show a slight increase from 20.41% in the ST to 21.40% in the TT1 and 22.33% in the TT2. By linking the RTs into a network, these cohesive chains form a “grid” (Hasan 1984: 210), which entails the textual coherence of a text. In addition, as the size of texts vary, these RTs are further measured per clause. In the ST, every clause contains the least RTs, 3.3, while the TT2 contains the most RTs per clause, 5.64, and TT1 falls in between, with 4.59 relevant tokens per clause. Thus, the number of RTs per clause also displays a trend of explicitation from the ST to the TT2. If we view the connections among RTs as a measurement of textual structure, the Chinese ST is looser in structure; while the two English TTs are tighter, with more threads of meaning concerning the topical development.

5 Discussion

When understanding a text, we need to know “who the text-producer is, what the intended audience is, what the time and place of text production and reception are, […] and the purpose or function of the text in the speech community in which it has been created” (Georgakopoulou and Goutsos 2004 [1997]: 16). As stated before, the ST and TTs were created under different temporal and spatial circumstances, and this cultural distance brings about a possible disjunction between the context of the source text and that of its interpretation (Hasan 1985: 46); in this study, the latter refers to the interpretation of the contemporary English TTs. According to Bernaerts et al. (2014), narrative theorists often assume that the translation process does not affect the narrative structure of text, however our study has found clear translation shifts in narration through cohesive chains, which may be attributed to factors such as place and time which vary from source to target texts (204). The explicitation of cohesive chains in translation thus sheds light on the interpretation of narrative texts with different readerships as well as in different contexts.

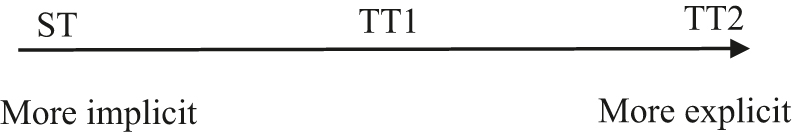

5.1 Cline of explicitation

As stated in the above sections, the use of cohesive chains and relevant tokens in the three texts shows varied degrees of explicitness in translation, with the ST displaying the most implicit patterns of cohesive chains, while the TT2 the most explicit ones, and the TT1 falls in between. The varied degrees of explicitness and explicitation in the process of translation from Chinese into English can be visualized as a cline of explicitation (see Figure 4).

Cline of explicitation of cohesive chains.

This cline of explicitation implies that the Chinese ST and the English TTs display different preferences in creating semantic continuity in the text, as cohesive chains are parameters of the realization of semantic meaning. In translation from ST to the two TTs, more explicit cohesive devices and chains are required in reconstructing the semantic meaning of the original text and construing the context of situation in the target language.

The varied extents of explicitness suggest differences in the socio-cultural backgrounds of each text and the translators’ personal styles. Kieras (1980) argues that highly cohesive texts are easier to process, in that one may say that it is easier for the TT2 readers to perceive the text and its meaning due to the highest extent of cohesive explicitness displayed.

The trend of explicitation from Chinese to English may reflect the “writer and reader’s responsibility” of different languages for effective communication (Hinds 1987: 146). In writer responsibility languages, “it is the writer’s task to provide appropriate transition statements so that the reader can piece together the thread of the writer’s logic which binds the composition together” (Hinds 1987: 146). In comparison, in reader responsibility languages, the readers need to play “a more active role” in determining the textual relationships (Hinds 1987: 146). From the ST to the TTs, English translations display a higher degree of writer’s responsibility while the comprehension of the Chinese text relies more on readers.

5.2 Cohesive chains and the context

Explicitation reduces the possibility of the target text from being ambiguous and makes more tangible the relation between the target text and the context, as a text “construes a context of situation, in which cultural norms and assumptions are in play” (Lukin 2013: 527). Context of situation can be described from contextual configurations, which consist of field (what the text is about), tenor (the interpersonal relationship involved), and mode (the particular part the language is playing: written or spoken) (Halliday and Hasan 1989 [1985]; Hasan 2009).

In the case of translation, where a ST and a TT are expected to be identical in terms of field, it is mode and tenor that reveal more differences, as the texts are produced by different authors targeting new readers. The Chinese ST initially targeted its contemporary Chinese readers in the eighteenth century, although it has, since then, been read by generations of Chinese readers as a classical novel. On the other hand, both English translations target Anglophone readers after the mid-1970s. Therefore, the translators would have taken into consideration not only the linguistic and cultural gaps between Chinese and English but also the considerable temporal gaps. Moreover, the two translations can be said to have been created with slightly different readership design. The Yang couple worked for the Beijing Foreign Languages Press, which is in charge of promoting Chinese culture in the world by publishing books and journals in non-Chinese languages; their translation is more suitable for readers with high cultural attainments in Chinese. In comparison, Hawkes, a sinologist, translated the novel out of his interest, and his version targets more general Anglophone readers (Cao 1973: 18). This difference suggests that Hawkes may have adopted the explicitation of cohesive devices more actively as a strategy to reduce the “responsibility” for his readers who may be less informed about Chinese culture.

The factor under mode that makes a difference across the texts is Medium, which refers to the “patterning the wordings themselves” (Halliday and Hasan 1989 [1985]: 58). The use of cohesive chains construes the patterns in different texts by driving text development through the narrative existents (characters, events, and subject), which remain the same from one event to the next in a narrative structure (Chatman 1980: 30). As ICs are text-bound, they contribute to the creation of the context of situation of each text. The higher percentages of ICs than those of SCs in both English TTs than in the ST indicate that the perceptions of the TTs rely more on the context of situation. On the other hand, as the SCs are not text-bound, they relate the text with its context of culture. According to Table 3, the two TTs use fewer SCs than the ST, which suggests that the perception of the ST relies more on the context of culture. In short, as the target text readers are temporally and spatially distant from the source context of culture, the explicitation of cohesive chains and the increased use of ICs in translation help the TT readers understand the source context of culture within the target context of situation.

6 Conclusion

Through an exploration of cohesive chains in the texts, this study has revealed a trend of explicitation in the realisation of the topical development from the Chinese ST to its English TTs. Readers’ judgement of coherence relies much on these cohesive chains that function as covert signals for the readers to assess the text as “relevant and informative” in the context of the specific text (Toolan 2013: 65). The more explicit the cohesive chains, the less demanding readers’ judgement of textual coherence will be. Thus, the trend of explicitation in translation from ST to the TTs reveals a lighter task for readers’ perception of the text.

Meaning in literary texts is not only derived from the connotation of linguistic items but also the relation between these linguistic items and the context (Widdowson 2014 [1983]: 46). The explicitation of cohesive chains in translation indicates the change of relation between text and its context in different cultures. Firstly, the explicitation from the ST to the TTs shows that the English texts are more explicitly manifested in driving the development of plot with cohesive chains. This may be because the translators felt a need to use more explicit cohesive devices to guide English target readers more gently through the book since there are considerable temporal and cultural gaps between the ST creation and the TT reception. While this observed explicitation might point to the hypothesis of explicitation as being inherent in translation (Blum-Kulka 1986), which is beyond the scope of this study focusing on the Chinese–English pair, we consider that the identified explicitation from Chinese to English is influenced mainly by the higher tendency of English texts to be writer responsible, while the Chinese text is more reader responsible. Thus, the English text-producers may have had to provide more covert clues for the connection among the existents to help enhance readers’ perception of the text. Secondly, though all the texts show higher percentages of ICs than of SCs, the preference of ICs over SCs is more pronounced in the two English TTs than in the ST. This is likely a result of the change of language. In translation from Chinese into English, the bond between the text and its context of culture has been weakened, and accordingly, the relationship between the target text and its context of situation has been strengthened with higher percentages of identity chains. Thirdly, TT1 displays features in between the ST and TT2; this highlights translators’ choices despite some inherent linguistic and cultural differences. Given that the English TTs are more explicit in cohesive chains and topical development, the difference between the two TTs are presumably a result of the combined influence of the differences in the first language, translators’ personal styles and different translation purposes.

The significance of this research lies firstly in the examination of explicitation in the English translations of Hou Lou Meng, and secondly the proposal of a new perspective to expand current studies of explicitation in translation. The latter has been achieved by investigating semantic development in narrative in translation through the explicitation of cohesive chains. It is hoped that the methodology of this research will inspire future translation research to explore explicitation from the perspective of cohesive chains and textual development.

References

Baker, Mona. 1996. Corpus-based translation studies: The challenges that lie ahead. Benjamins Translation Library 18. 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.18.17bak.Suche in Google Scholar

Baker, Mona. 1997. In other words: A coursebook on translation. London and New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Becher, Viktor. 2010. Abandoning the notion of “translation-inherent” explicitation: Against a dogma of translation studies. Across Languages and Cultures 11(1). 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.11.2010.1.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Becher, Viktor. 2011. Explicitation and implicitation in translation: A corpus-based study of English–German and German–English translations of business texts. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg Dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Bernaerts, Lars, Liesbeth de Bleeker & July de Wilde. 2014. Narration and translation. Language and Literature 23(3). 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947014536504.Suche in Google Scholar

Blum-Kulka, Shoshana. 1986. Shifts of cohesion and coherence in translation. In Juliane House & Shoshana Blum-Kulka (eds.), Interlingual and intercultural communication, 298–313. Trubingen: Gunter Narr.Suche in Google Scholar

Butt, David, Alison Moore, Caroline Henderson-Brooks, Meares Russell & Joan Haliburn. 2010. Dissociation, relatedness, and ‘cohesive harmony’: A linguistic measure of degrees of ‘fragmentation’? Linguistics and the Human Sciences 3(3). 263–293. https://doi.org/10.1558/lhs.v3i3.263.Suche in Google Scholar

Cao, Xueqin. 1973. The story of the stone (Hawkes David, trans.), vol. 1. London: Penguin.Suche in Google Scholar

Cao, Xueqin. 1978. A dream of red mansions (Yang Xianyi & Yang Gladys, trans.). Beijing: People’s Literature Publishing House.Suche in Google Scholar

Cao, Xueqin. 1982. 红楼梦 [A dream of red mansions]. 北京 [Beijing]: 人民文学出版社 [People’s Literature Publishing House].Suche in Google Scholar

Chatman, Seymour. 1980. Story and discourse: Narrative structure in fiction and film. New York: Cornell University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, Wallace. 2004. Inuestigating explicitation of conjunctions in translated Chinese: A corpus-based study. Language Matters 35(1). 295–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228190408566218.Suche in Google Scholar

Cloran, Carmel, Virginia Stuart-Smith & Lynne Young. 2005. Models of discourse. In Ruqaiya Hasan, Christian Matthiessen & Jonathan Webster (eds.), Continuing discourse on language: A functional perspective, 647–670. London and Oakville: Equinox Publishing Ltd.Suche in Google Scholar

Dimitrova, Birgitta. 2005. Expertise and explicitation in the translation process. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/btl.64Suche in Google Scholar

Emmott, Catherine. 2002. Responding to style. Cohesion, foregrounding and thematic interpretation. In Max Louwerse & Willie van Peer (eds.), Thematics. Interdisciplinary studies, 91–117. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/celcr.3.10emmSuche in Google Scholar

Georgakopoulou, Alexandra & Dionysis Goutsos. 2004 [1997]. Discourse analysis: An introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP.10.3366/edinburgh/9780748620456.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1973. Explorations in the functions of language. London: Edward Arnold.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood. 1977. Text as semantic choice in social contexts. In A. van Dijk & J. Petӧfi (eds.), Grammars and descriptions. Berlin: de Gruyter.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Christian Matthias Ingemar Martin Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. London and New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203783771Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London and New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood & Ruqaiya Hasan. 1989 [1985]. Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hansen-Schirra, Silvia, Stella Neumann & Erich Steiner. 2007. Cohesive explicitness and explicitation in an English–German translation corpus. Languages in Contrast 7(2). 241–266. https://doi.org/10.1075/lic.7.2.09han.Suche in Google Scholar

Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1984. Coherence and cohesive harmony. In James Flood (ed.), Understanding reading comprehension: Cognition, language and the structure of prose, 181–219. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.Suche in Google Scholar

Hasan, Ruqaiya. 1985. Linguistics, langauge and verval art. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Hasan, Ruqaiya. 2009. The place of context in a systemic functional model. In Michael Halliday & Jonathan Webster (eds.), Continuum companion to systemic functional linguistics, 166–189. London & New York: Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Hatim, Basil & Ian Mason. 1990. Discourse and the translator. London and New York: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Hinds, John. 1987. Reader versus writer responsibility: A new typology. In Ulla Connor & Robert Kaplan (eds.), Writing across languages: Analysis of L2 text, 141–152. Mass: Addison-Wesley.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiménez-Crespo, Maquel A. 2011. The future of general tendencies in translation: Explicitation in web localization. Target. International Journal of Translation Studies 23(1). 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.23.1.01jim.Suche in Google Scholar

Kieras, David.. 1980. Initial mention as a signal to thematic content in technical passages. Memory & Cognition 8(4). 345–353. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03198274.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Defeng, Chunling Zhang & Kanglong Liu. 2011. Translation style and ideology: A corpus-assisted analysis of two English translations of Hongloumeng. Literary and Linguistic Computing 26(2). 153–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqr001.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Xiaolin. 2010. 评价系统视域中的翻译研究-以《 红楼梦》 两个译本对比为例 [Translation study: an appraisal perspective—a case on comparative study of two English versions of Hong Lou Meng]. 外語學刊 [Foreign Language Research] 2010(3). 161–163.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Yingjiao. 2012. 《红楼梦》英全译本译者主体性对比研究 [A comparative study of translator’s subjectivity of the story of the stone]. 外国语文 [Foreign Language and Literature] 28(01). 111–115.Suche in Google Scholar

Lukin, Annabelle. 2013. What do texts do? The context-construing work of news. Text & Talk 33(4–5). 523–551. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2013-0024.Suche in Google Scholar

Marco, Josep. 2012. An analysis of explicitation in the COVALT corpus: The case of the substituting pronoun one (s) and its translation into Catalan. Across Languages and Cultures 13(2). 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1556/acr.13.2012.2.6.Suche in Google Scholar

McEnery, Tony & Richard Xiao. 2004. The Lancaster Corpus of Mandarin Chinese (LCMC). Lancaster: Lancaster University. Available at: http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/corpus/LCMC/.Suche in Google Scholar

Morris, Jane & Graeme Hirst. 2006. The subjectivity of lexical cohesion in text. Computing attitude and affect in text: Theory and applications, 41–47. Dordrecht: Springer.10.1007/1-4020-4102-0_5Suche in Google Scholar

Newmark, Peter. 1987. The use of systemic linguistics in translation analysis and criticism. In Ross Steele & Threadgold Terry (eds.), Language topics: Essays in Honor of Michael Halliday, 293–304. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.lt1.27newSuche in Google Scholar

Puurtinen, Tiina. 2004. Explicitation of clausal relations: A corpus-based analysis of clause connectives in translated and non-translated Finnish children’s literature. In Mauranen Anna & Pekka Kujamäki (eds.), Translation universals: Do they exist?, 165–176. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/btl.48.13puuSuche in Google Scholar

Stockwell, Peter. 2002. Cognitive poetics: An introduction. London and New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Toolan, Michael. 2009. Narrative progression in the short story: A corpus linguistic approach. Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/lal.6Suche in Google Scholar

Toolan, Michael. 2013. Coherence. In Hühn Peter, Christoph Meister Jan, John Pier & Wolf Schmid (eds.), The living handbook of narratology, 2nd edn, vol. 1, 65–83. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110316469.65Suche in Google Scholar

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs & Mary Louise Pratt. 2008. Language, linguistics and literary analysis. In Carter Ronald & Stockwell Peter (eds.), The language and literature reader, 39–48. London and New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781003060789-6Suche in Google Scholar

Vinay, Jean-Paul & Darbelnet Jean. 1958. Stylistique comparée de l’anglais et du français [Comparative stylistics of French and English: A methodology for translation]. Paris: Montréal: Didier/Beauchemin.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Li. 1985 [1959]. 中国现代语法 [Chinese modern grammar]. 北京: 商务印书馆 [Beijing: The Commercial Press].Suche in Google Scholar

Widdowson, Henry. 2007. Discourse analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Widdowson, Henry. 2014 [1983]. Stylistics and the teaching of literature. London and New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315835990Suche in Google Scholar

Wu, Kerong & Lai Peng. 2011. 论失语症患者语篇的衔接 [On textual cohesion of the aphasiac’s texts]. 华南师范大学学报(社会科学版) [Journal of South China Normal University (Social Science Edition)] 6. 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-21347-2_11.Suche in Google Scholar

Zufferey, Sandrine & Cartoni Bruno. 2014. A multifactorial analysis of explicitation in translation. Target: International Journal of Translation Studies 26(3). 361–384. https://doi.org/10.1075/target.26.3.02zuf.Suche in Google Scholar

Zhang, Dandan & Zequan Liu. 2016. 基于语境的《红楼梦》报道动词翻译显化研究— —以王熙凤的话语为例 [A contextualized investigation of the explicitation of reporting verbs in the English translations of Hong Lou Meng: With reference to Wang Xifeng’s utterences ]. 外语与外语教学 [Foreign Languages and their Teaching] 2016(04). 124–134, 151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2016.08.017.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Xi Li and Long Li, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Embodiment is not the answer to meaning: a discussion of the theory underlying the article by Carina Rasse and Raymond W. Gibbs, Jr. in JLS 50(1)

- Subjective time, place, and language in Lisa Gorton’s The Life of Houses

- Locating stylistics in the discipline of English studies: a case study analysis of A.E. Housman’s ‘From Far, from Eve and Morning’

- Reframed narrativity in literary translation: an investigation of the explicitation of cohesive chains

- Book Review

- Poetry in the Mind: The Cognition of Contemporary Poetic Style

- Contemporary French and Francophone Narratology

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Embodiment is not the answer to meaning: a discussion of the theory underlying the article by Carina Rasse and Raymond W. Gibbs, Jr. in JLS 50(1)

- Subjective time, place, and language in Lisa Gorton’s The Life of Houses

- Locating stylistics in the discipline of English studies: a case study analysis of A.E. Housman’s ‘From Far, from Eve and Morning’

- Reframed narrativity in literary translation: an investigation of the explicitation of cohesive chains

- Book Review

- Poetry in the Mind: The Cognition of Contemporary Poetic Style

- Contemporary French and Francophone Narratology