Abstract

Communities have a vital role to play in managing the risks associated with natural disasters. As such, their strengths, weaknesses, and priority concerns must be factored into policy decisions to ensure local recovery efforts reflect community needs. Regular engagement with community members provides opportunities for emergency managers and first responders to tap into a reservoir of local knowledge to build a shared understanding of how to foster local preparedness and help communities reduce the impact of a disaster. Not all communities are alike; needs can differ for a variety of reasons and can help determine the best ways to galvanize an appropriate response. The methods of engagement should also be tailored to ensure communities are willing and able to participate in the types of interactions emergency managers wish to initiate. In this paper, we used a mixed method approach to examine several different community engagement and data collection strategies conducted, observed or examined by our research team during six months of post-Hurricane Maria recovery efforts in Puerto Rico from February to July 2018. The aim of this study is to assess whether different outreach approaches used illuminated different perceptions about disaster preparedness and recovery and to identify what works and what does not work when engaging communities in emergency preparedness and recovery activities.

1 Introduction: Why Community Engagement?

Communities have a vital role to play in managing the risks associated with natural disasters. As such, their strengths, weaknesses, and priority concerns must be factored into decisions about building resiliency to ensure that policies and programs appropriately leverage local capacities and reflect community needs. Regular engagement with community members provides opportunities for emergency managers and first responders to tap into a reservoir of local knowledge to build a shared understanding of how to foster local preparedness and help communities reduce the impact of a disaster. Not all communities are alike; needs can differ for a variety of reasons (geography, demographics, religion, languages spoken, political affiliations, etc.) and can help determine the best ways to galvanize an appropriate response. The methods of engagement should also be tailored to ensure communities are willing and able to participate in the types of interactions emergency managers wish to initiate (Table 1).[1]

Puerto Rico (PR) municipalities and locations where resident focus groups, outmigrant focus groups, community member and SME interviews and community walk-throughs were conducted between April and July 2018.

| PR municipality/location | No. of PR resident focus groups | No. of PR resident individual interviews | No. of outmigrant focus groups | No. of SME interviews | No. of community walk-throughs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miami, FL | 2 | ||||

| Orlando, FL | 2 | ||||

| New York | 1 | ||||

| Texas | 1 | ||||

| Manchester, UK | 1 | ||||

| Corozal | 1 | 1 | |||

| Luquillo | 1 | 3 | |||

| Guayama | 1 | 1 | |||

| Naranjito | 1 | 3 | |||

| Peñuelas | 1 | ||||

| Maricao | 1 | ||||

| Orocovis | 1 | ||||

| Loíza | 1 | 1 | |||

| Utuado | 1 | 2 | |||

| Aguas Buenas | 2 | ||||

| Río Grande | 1 | 1 | |||

| Lares | 1 | ||||

| Barranquitas | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | |

| Yabucoa | 1 | 1 | |||

| Cayey | 1 | 2 | |||

| Las Marias | 1 | ||||

| Maunabo | 1 | 2 | |||

| Patillas | 1 | 2 | |||

| Lajas | 1 | ||||

| San Juan | 2 | 6 | |||

| Carolina | 1 | ||||

| Ponce | 1 | 3 | |||

| Yauco | 2 | ||||

| Culebra | 3 | ||||

| Aguadilla | 1 | ||||

| Caguas | 1 | ||||

| Humacao | 1 | ||||

| Hormigueros | 1 | ||||

| Tibes | 1 | ||||

| Mayaguez | 1 | 1 | |||

| Comerio | 5 | ||||

| Toa Baja | 3 | ||||

| Arecibo | 1 | 11 |

-

For PR resident focus groups, PR resident individual interviews, outmigrant focus groups, and SME interviews, the number indicates the number of focus groups and interviews conducted in each municipality. For community walk-throughs, the number indicates the number of participants in each municipality.

In this paper, we used a mixed method approach to examine several different community engagement and data collection strategies conducted, observed or examined by our research team during six months of post-Hurricane Maria recovery efforts in Puerto Rico from February to July 2018.[2] The community engagements were part of a broader effort by over 150 researchers, NGO staff and subject matter experts who conducted extensive assessments of Puerto Rico’s hurricane damage and associated needs to assist in informing Puerto Rico’s vision for disaster recovery.[3]

The aim of this study is to assess whether different outreach approaches used during this period of research illuminated different perceptions about disaster preparedness and recovery and to identify what works and what does not work when engaging communities in emergency preparedness and recovery activities. We also conducted a literature review to compare how outreach efforts in Puerto Rico measure up to recognized best practices from a variety of fields related to disaster management. We sought a breadth of perspectives, both domestic and international, governmental and non-governmental, within the fields of public health, safety, and emergency management. This research allowed us to identify commonly cited practices regarding the who, why, when, and how to conduct community engagements.

While many common threads emerged, there seems a paucity of research measuring the nature and quality of participant feedback collected during disaster and emergency recovery-centric outreach initiatives.[4] This paper seeks to address that gap.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Who to Engage and Who Should Do the Engaging?

Studies highlight the importance of community inclusivity and frequently note the value of leveraging input from a wide range of local partners to foster shared understanding and co-benefits for both researchers and the community alike.[5] When identifying a target community for engagement, researchers often cast a wide net to look beyond the context of a physical setting to include spatially distant outmigrant diasporas, or self-identified communities of interest that may form around commonalities such as religion and ethnic affiliations, recreational activities, or online networks. Thus, community engagement can have a global reach that captures an expansive set of perspectives and allows disaster practitioners an opportunity to leverage these bonds to inform recovery efforts and identify sources of support located outside the physical disaster area.[6]

Who is conducting the engagement is as important as the target of engagement. Studies have observed that racial/ethnic tensions and cultural divides can sometimes exist between outside researchers and minority communities. They assert that real or perceived power differentials between outside researchers and historically oppressed populations can stunt trust building and information sharing opportunities.[7] A lack of trust in government institutions is a common theme cited as a barrier to effective community engagement, “due to past social injustices, persisting inequities, and fear of government control, or deportation….a lot of them have felt at some points that they’ve been taken advantage of, or they feel mistreated and have frustration with the system.”[8] Consequently, research has shown considerable interest in establishing community-based participatory research partnerships to pool the expertise of academia, local knowledge, and other sources within the community of interest to apply a multi-lensed view from which to examine disparities within communities (Schultz, Israel, and Lantz 2002). Kelly, Mock, and Tandon (2001) highlights the importance of “adapting the research enterprise to the culture and context of the participants.”[9] Wright et al. (2011) [10] expands on this notion, examining the quality of community-researcher relationships that form during successive community engagements. Goodman et al. (2016) nods to the value of community input and develops metrics to measure the extent to which researchers have incorporated community members into the research project design and implementation. Such approaches have sought to increase understanding of how to build trust between researchers and prospective community participants.

Identifying community liaisons and building trusted relationships with community leaders can help to establish a partnered approach that fosters a collaborative environment. Pre-established relationships can also save emergency managers valuable time in the event of a disaster, when responsiveness can be the difference between life and death. FEMA recognizes the importance and aims to enhance local-level access to federal support. For example, at a 2018 speech presented at the National Association of Counties, FEMA Administrator, Brock Long, described his intentions to embed FEMA personnel in community-level organizations on a regular basis. “We’re going to start changing. I want the relationship now rather than when disaster strikes.”[11]

2.2 Why Engage?

Sullivan (2003) notes that community involvement facilitates physical and mental recovery as disaster survivors gain a sense of self-determination in shaping their own futures. Incorporating community perspectives into post-disaster recovery decisions “alters their status from passive pawns in the process, to once again active and contributing directors of their own destiny.”[12] The United Nations recognizes the importance of elevating the voices of vulnerable populations noting that, “too often, the less organized voices of the survivors are not heard, and … is given second-priority at best.”[13]

The International Red Cross Code of Conduct for Disaster Relief highlights the need to “strive to achieve full community participation in relief and rehabilitation programs;”[14] The United Nations captured lessons learned from post-tsunami recovery efforts in the Asia Pacific islands in 2004. A subsequent 2006 report recognized that “a disaster’s survivors are best placed to design the recovery strategy that best meets their needs. And they should be the ultimate judges of a recovery effort’s success or failure.”13

Disaster response and recovery approaches in the U.S. take a similar view. The National Response Framework outlines roles and responsibilities for individuals and communities in disaster preparedness, response and recovery.[15] FEMA emphasizes that “all disasters are local;” A 2011 report by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) describes its “Whole Community” approach to disaster management acknowledging the limited reach of government capabilities and the importance of “engaging with members of the community as collaborative resources to enhance the resiliency and security of our nation.”[16]

2.3 When to Engage?

Knowing when to engage is as important as knowing who is involved in the engagement. The long-term recovery process can take a significant physical and mental toll on survivors. Rural planning and development research suggest communities need time to process and grieve their losses. “Having just gone through a major disaster, one ought to be sensitive to the loss the community has experienced, and recognize that there may need to be a healing process that takes place either before or concurrently with the community re-building.”[17] Additionally, disaster recovery studies have shown that eliciting feedback on long-term recovery goals is difficult to accomplish when disaster victims are worried about meeting immediate basic needs. “In many communities, they are already facing their rainy day. Preparing for tomorrow is a luxury they can’t afford.”[18] Communities will have their own priorities and concerns, which will impact the effectiveness of an engagement activity. “In disaster research, relatively few people living in disaster impacted communities want to spend time being counted so that lessons can be learned and applied to inform future circumstances.” Research suggests those planning to conduct community engagements should look for timing cues that might signal a community’s receptivity, for example, when community members begin proactively approaching the government requesting action or submitting ideas for recovery that extend beyond immediate disaster needs.

2.4 How to Engage?

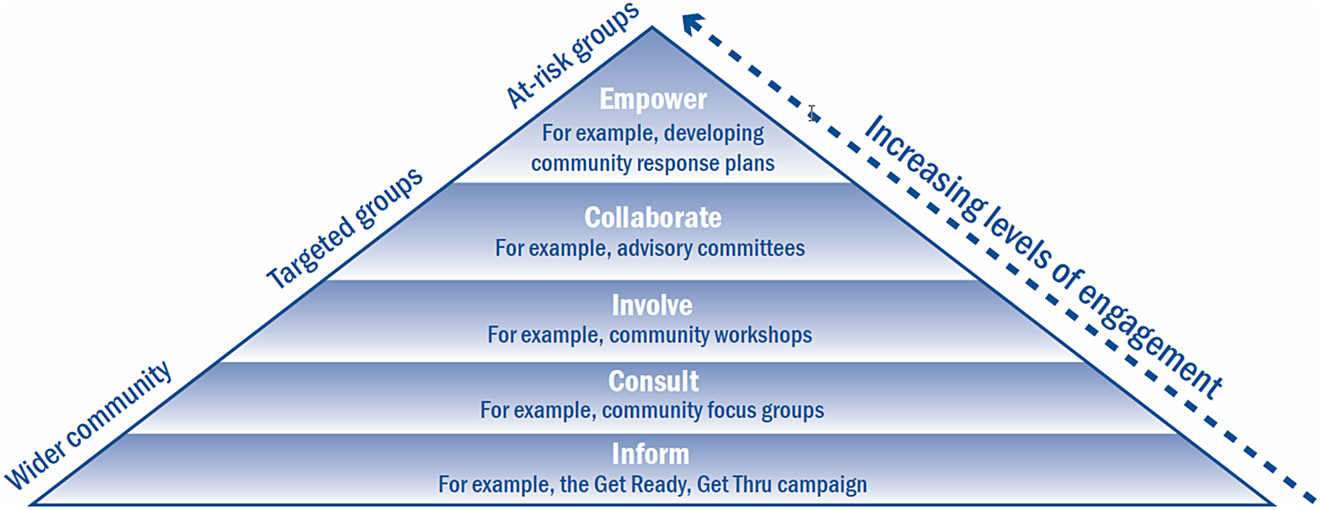

Different formats of engagement activities can also influence outcomes. The International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) notes how the goals of public participation initiatives may warrant different levels of community engagement.[19] The association developed a ‘Spectrum of Public Participation’ to describe the scope, intent, advantages and disadvantages of various types of interactions with the community (Figure 1).

Levels of engagement.

Source: Community Engagement in the CDEM context Civil Defence Emergency Management: best practice guide, p.19: https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/publications/bpg-04-10-community-engagement.pdf.

Applying this to the disaster management context, in low level engagements, the purpose may be to inform as wide a population as possible of critical disaster preparedness, response or recovery details. Emergency managers might disseminate information through mass media campaigns, websites and information meetings. These strategies are one-way communication platforms seeking to provide information rather than eliciting feedback from the targeted audience. At the opposite end of the spectrum, high-level engagements consist of those activities that offer the promise of directly involving the public in the decision-making process. Developing collaborative partnerships and establishing advisory committees with a small, select number of community leaders are ways of engaging at this level and offer the chance to empower local communities to play an integral role in the decisions that affect their lives.

A number of community engagement strategies lie in between these types to include the areas of focus in this study: focus groups, community walk-throughs, and stakeholder interviews. Each approach has its benefits and drawbacks. Focus groups provide opportunities to capture more context behind participant views than other data collection methods can typically illuminate. They might also generate discussions that raise latent issues not considered in the design of the original protocol. Focus group settings can provide more ‘bang for the buck’ leveraging one forum to collect data from multiple participants.[20] However, without strong facilitators, there is a risk of group think;[21] vocal participants may dominate the conversation or the discussion can easily stray off topic. Additionally, the time and resources needed to schedule, coordinate, facilitate and analyze the data collected from these forums can pose significant constraints on emergency managers eager to acquire information before the next disaster hits.

Community walk-throughs, which consist of informal, door-to-door interactions within a given neighborhood, afford the opportunity to access particularly hard to reach populations such as the elderly, infirm, family caregivers and socially excluded groups who may not otherwise have their voices heard. Excluding the travel required to reach these populations, they are also far less resource-intensive than focus groups. But community walk-throughs have their own risks, as the ad hoc nature of the engagement strategy offers no guarantee people will be home, much less, willing to engage. It might also be more difficult to maintain a structured format during the engagement as individuals come and go during the conversations and the demographics of participation are not easily controlled. Working with a community liaison can help avoid some of these challenges, though the informal nature of the method still leaves room for uncertainty.[22]

Interviews allow for a more controlled, personal approach and can offer opportunities for people to raise unique or sensitive issues that may not be captured in other forms of data collection.[23] However, interviews can be time and labor-intensive, and may not generate as many data points.[24] The nature of these kinds of data collection opportunities also requires limiting participation to a small sample of the community. Ensuring the participants are representative of the community is critical to capture responses that effectively reflect the population of interest.

In sum, several basic guiding principles for community engagement emerged in our literature review:

Know who you want to engage and who should engage: Are target communities vulnerable? Distrustful of outsiders? Difficult to reach? Establishing engagement teams that include individuals from the community can help ease introductions and establish the basis for trust.

Know why you want to engage: Is it to inform? to be informed by local knowledge? The outcomes of community engagement strategies will differ depending on the purpose of the effort. A partner-minded design can encourage a more inclusive, collaborative approach to recovery.

Know when to engage: What signals or cues exist to demonstrate the public is ready to reflect beyond their immediate needs? Few victims are prepared to reflect about recovery when still in immediate need. Participant views will likely evolve over time.

Know how to engage: Are participants more receptive to group settings? Might participants share more sensitive information in one-on-one interactions? Different engagement approaches may achieve different outcomes depending on the topic.

With these best practices in hand, the next section seeks to contribute to the literature by analyzing the outcomes of several different approaches to community engagement conducted in post-Maria Puerto Rico.

3 Community Engagement Approaches in Puerto Rico

We examined several community engagement activities that occurred during the recovery phase of Hurricane Maria to include focus groups and community and SME interviews and community walk-throughs. The next section describes each research design.

3.1 Focus Groups

Our study team hired two nonprofits with direct links to Puerto Rican communities to conduct 17 focus groups (n = 8–12 in each focus group) in different municipalities and four separate focus groups conducted with diaspora population in Miami during the months of April and May 2018. The nonprofits helped select the location of the focus groups and residents based on community characteristics and a desire to reach a diverse sample of residents (i.e. location on island, urban/rural, and socioeconomic conditions). The purpose of the focus groups was to gain insight into the experiences of residents and their thoughts on challenges and potential solutions during the recovery process. The focus groups took place during morning weekday hours, were conducted in Spanish and ranged in length from 60–90 min. All participants were over 18 years of age. The topics touched on three broad categories: (1) pre-hurricane preparation/hazard mitigation, (2) hurricane impact and (3) hurricane recovery. Results of these focus groups helped to inform research published in***. It also infomred a more comprehensive effort to support the development of the Governor of Puerto Rico’s Long-Term Recovery Plan.[25]*

We expanded our analysis to examine a similar series of focus groups conducted by Reimagina Puerto Rico, an NGO-based initiative established to identify opportunities for philanthropic organizations to contribute to Puerto Rico’s recovery. The organization conducted seven community focus groups of over 170 individuals in San Juan, Humacao, Arecibo, Caguas, Ponce, and Mayagüez. The aim was to “to obtain an Islandwide perspective on recovery and resilience” and to document unmet needs before, during and after Hurricane Maria. Interviews were conducted in Spanish. The feedback was incorporated into a final report intended to produce “an actionable and timely set of recommendations to guide the use of philanthropic, local government and federal recovery funds to help rebuild Puerto Rico in a way that makes the Island stronger – physically, economically, and socially – and better prepared to confront future challenges.”[26]

3.2 Interview Approach

From March to July 2018, our study team leveraged local NGO’s to identify and conduct interviews with community leaders (social activists, religious leaders, government officials) subject matter experts (SMEs) and business professionals (municipal social and emergency service providers, law enforcement, legal services, education, staff from NGOs targeting vulnerable populations) and other community members. Thirty-one interviews were with community residents that took place in 18 municipalities across the island; An additional 13 interviews were conducted with disaster response/recovery experts located in six municipalities. An additional three interviews were conducted telephonically with experts located in New York, Texas, and Manchester, U.K. The aim was to understand the challenges associated with disaster preparedness, impact and recovery from a wide range of expertise. To identify participants, we reached out to several NGOs to collect relevant information and then used snowball sampling techniques to identify others. Subject matter experts were identified through literature reviews and networking contacts. Interviews were conducted in either Spanish or English (whichever the participant preferred), typically lasted an hour and took place at a time and location of their convenience.

3.3 Community Walks

From March to July 2018 HSOAC conducted four community walks accompanied bya Puerto Rican community activist who encourages and teaches local empowerment practices to compensate for the government’s inability to fully meet community needs in the times of crisis. The study team relied on personal networks to identify the local community activist who specializes in working with Puerto Rico’s most vulnerable communities.[27] We provided the community activist the initial list of municipalities of interest[28] and requested he select specific locations where we could approach everyday residents in their own environments. The goal was to reach individuals who would otherwise be inhibited from engaging during other more formal settings for a variety of reasons (lack of transportation, physical impairments, family obligations such as child-rearing or caring for the sick or elderly, intimidation in large groups, a sense of complacency, etc.). These community walks took place in the following municipalities: Comerio, Barranquitas, Arecibo, and Toa Baja. The activist accepted no payment for his effort.

Part of the study team accompanied the community activist on these informal walks. In this approach, the activist (and study team members) encountered individuals in the streets, on their porches, at local ‘watering holes’ or other community gathering places. As with the other formats, individuals were asked to provide thoughts on disaster preparedness, impact and recovery from Hurricane Maria. The conversations took place during morning and afternoon hours, were informal, held in Spanish, and often drew the attention of other residents in the area who noticed our presence and also wanted to share their views. Conversations typically lasted an hour. Approximately 25 people participated in these engagements to include single mothers, elderly, shopkeepers, unemployed men, and disabled citizens among others.

While the engagement types differed, roughly the same semi-structured interview guide was used in each setting, in the language of preference, during the same duration. This allowed us to make some general comparisons among engagement types. There are some important limitations to this post hoc analysis of community engagement strategies, however, including the unequal number of participants recruited between research designs and a lack of consistent documentation on participant demographics (i.e. age, gender, employment). This presented some methodological challenges when drawing comparisons among groups.

To address these issues, we used Dedoose[29], a qualitative text analysis software, to organize and normalize participant feedback collected during focus groups, interviews and community walk-throughs. While demographic descriptors were limited to “community leader,” “community member” and “professional,” the analytical platform did allow us to code equally for the type of engagement and search for trends within a number of key themes incorporated into the coding scheme. All told, the team coded 81 engagements and examined attitudes about government performance in hurricane-related issues, preparedness, vulnerability, community resilience/resignation and optimism or pessimism about the future.

The coding team coded transcripts focused on the following themes:

Psychological and Physical Trauma

Employment and Jobs

Issues Related to the Economy

Personal Housing and Property

Infrastructure and Services

Vulnerable Populations (elderly, children, women, disabled)

Informal Housing

Outmigrants

Undocumented Persons

Isolated Communities

Government capacity

Perceptions of government (trust/distrust)

Outlook of the future (optimistic/pessimistic, resignation/complacency)

Effectiveness of community engagements

We then extracted specific excerpts to provide richer context to better understand and interpret the results.

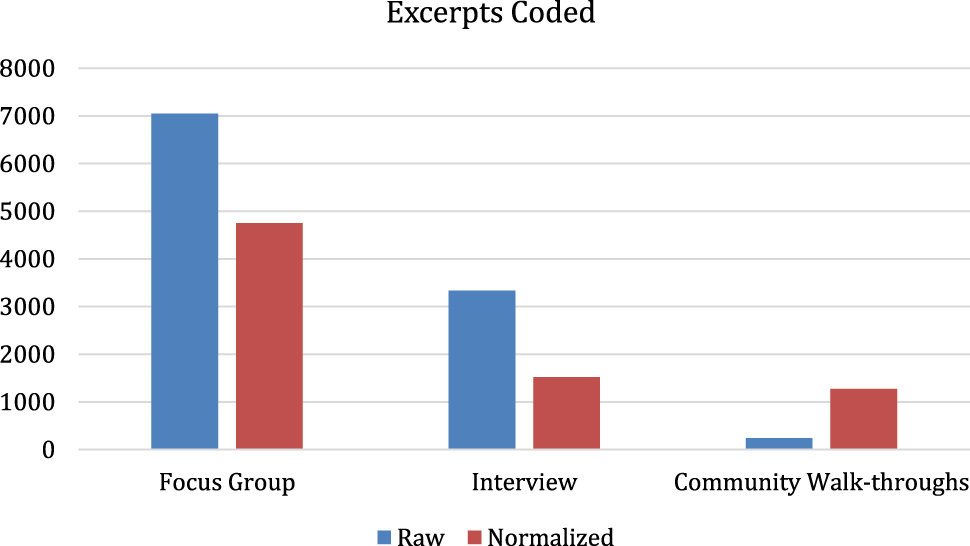

3.4 Analysis of Total Responses

Figure 2 illustrates the total number of excerpts coded from focus groups, interviews and community walks. Not surprisingly, focus groups provided the largest number of data. This corresponds to the higher number of individuals who participated, approximately 300 attendees compared to 47 interviews, and 25 residents encountered during walks through vulnerable communities. Considering the unequal balance of responses, we normalized the data in subsequent analysis to somewhat level the playing field.

Total number of excerpts coded.

3.5 Community Cues Suggest Residents Not Yet in Recovery Mode

The community engagements examined in this research all occurred between 6 and 10 months after Hurricane Maria in April to July of 2018. This limits the ability to assess whether variability in response outcomes occurred based on different engagements timeframes. We did discover, however, that when asked questions equally about all disaster phases (pre, response, and recovery) hurricane survivors were still most interested in discussing the response phase and the immediate impact of the storm to include critical infrastructure damage, physical and psychological harm, how it impacted the island’s most vulnerable, the lack of preparation, and the lack of government capacity to adequately address residents’ needs. Figure 3 highlights immediate response-related themes in red below and recovery centric themes in blue.

Key themes.

These findings suggest residents continue to struggle obtaining reliable basic essential services. This seems to support the literature that timing matters; disaster survivors need a considerable amount of time to heal—both practically and emotionally—from the devastating impact of a natural disaster and tend to be less prepared to, or interested in, talking about reimagining recovery when immediate needs remain unfilled.

We found consistency in views among community engagement participants on some of the most pressing recovery challenges. We wanted to explore the data further to determine where perceptions regarding the hurricane experience might diverge based on how respondents were engaged. Some interesting trends emerged.

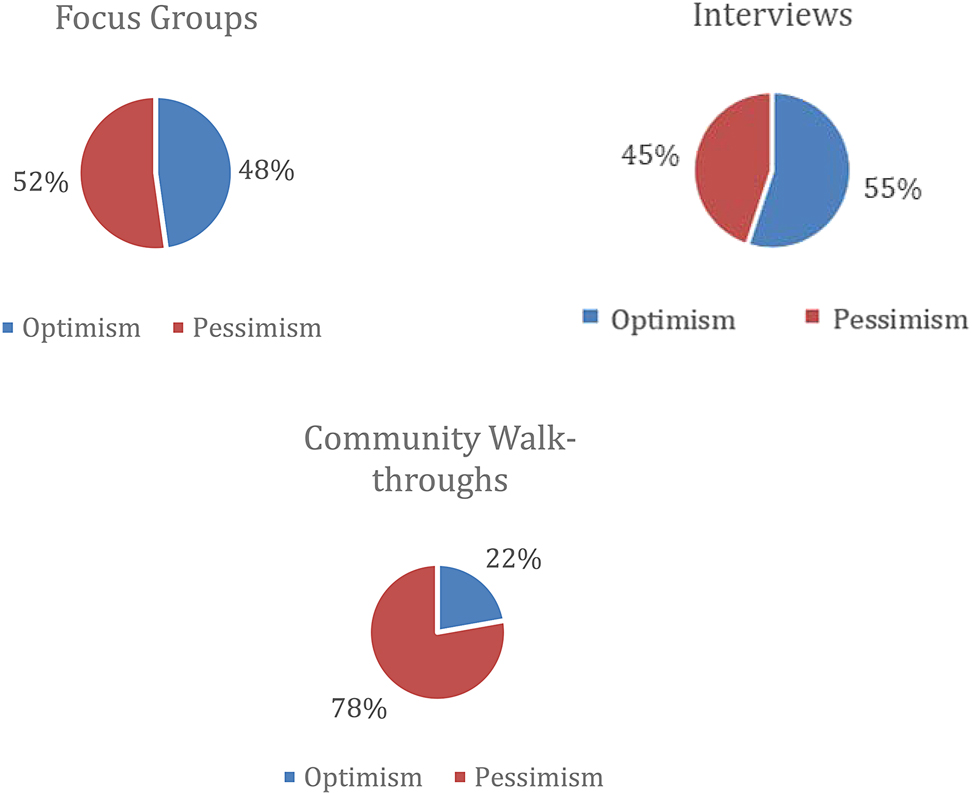

3.6 Responses About Perceptions of the Future Vary by Engagement Type

On whole, focus group members and interviewees views about the future were roughly just as optimistic as pessimistic. Community walk-throughs revealed a higher percentage of pessimistic views than optimistic (Figure 4).

Perception about the future by engagement type.

We examined what lay behind these views and found that roughly 42 percent of focus group responses coded as optimistic came from discussions with outmigrants describing their hopes for a better life on the mainland. The following excerpts indicate outmigrant’s reasons positive outlook centered on high hopes for better jobs, health care and education to be found outside Puerto Rico.

Q. Do you plan on staying here in Florida?

1 – yes, I have nothing else to look for over there, whatever was left there is gone. Professionally, in our profession it doesn’t compare, we make three times the amount we made there. Also our son is getting some health studies done here, he came out positive in one and just came out positive in another. So they are running some tests, and here the treatment is covered completely, over there it’s 5 k a months and it was an odyssey to have to ask for referrals, fighting with the doctors so they will give me referrals. One time we had to collect donations at my job to get his medications.

We want to be well, live well because it’s possible here. Here there is a future for children and for us. It is clear we need help from the government but we don’t want to depend on it. Puerto Ricans are known because we are hardworking and we are proud because we want things to be our own and were not people expecting handouts its moving forward.

But I said mami, I am leaving, bought a ticket to Orlando. A few days later I find out that a university here is offering help. They offered me acceptance at St. Thomas university they offered me 2500 dollars room and board and all included to the university eh, I am studying here, I love it they include us in everything. They have treated us super good, super, too good I cannot ask for anything more because here they have given me everything. The fact is that I did not think that they were going to treat us so well … We are trying to help and try to move ahead because that is what we are in search of and at least we want to achieve our future and to contribute a grain of what we can to the society.

Focus group members remaining on the island also expressed optimism, though tended to highlight the smaller things in life:

I also believe that the hurricane left in us a sensation of enjoying the good things in life: a conversation, to listen to the radio, to eat with the family, and to not be as distracted by technology. I believe I benefited from the hurricane in the sense that everybody would meet in my house every Sunday and we’d have that sharing moment.

But it was amazing to see how the earth has renewed. My pumpkins usually come out small but this year they are very big, like three times the size. I think for agriculture it has been good, we have to take advantage, because my dad would always say, we have to find a positive to the negative.

Many of these resident focus group members sought refuge in notions of community resilience and in a sense of unity that emerged in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane:

At least in my community, it’s been more united. People have been more united and we’ve gone out on the streets to visit people, to find out what the problems and the needs are. Me personally, 19 days after the hurricane, or earlier than that, I went out onto the streets with my colleagues and there were lots of needs, but the community has been more united. Those people weren’t talking about grudges…

Well, apart from all of the negatives that it might have brought, this hurricane has brought lots of positives. We’ve learned to give a helping hand, to show solidarity to one another. We’ve learned not to see others as enemies, as strangers, rather as brothers, my neighbor, and, “Let’s work together. Let’s go and clear the roads. Let’s go and clear the rubble. Let’s go and help.” I saw a lot of solidarity. I saw a lot of togetherness. I saw a lot of acceptance.

The varied responses can inform emergency managers and recovery experts in important ways. For one, aspirations of obtaining better health and economic prosperity compelled some residents to look beyond Puerto Rico for their futures. If Puerto Rico considers the return of its citizens to the island a priority for long-term recovery, solutions warrant investments that improve the socio-economic well-being of the population. Residents who remained after the hurricane derived optimistic outlooks from the strong community bonds that formed or were fortified in the wake of the storm—a reminder for disaster practitioners to tap into these networks so that community resources can be effectively integrated into recovery.

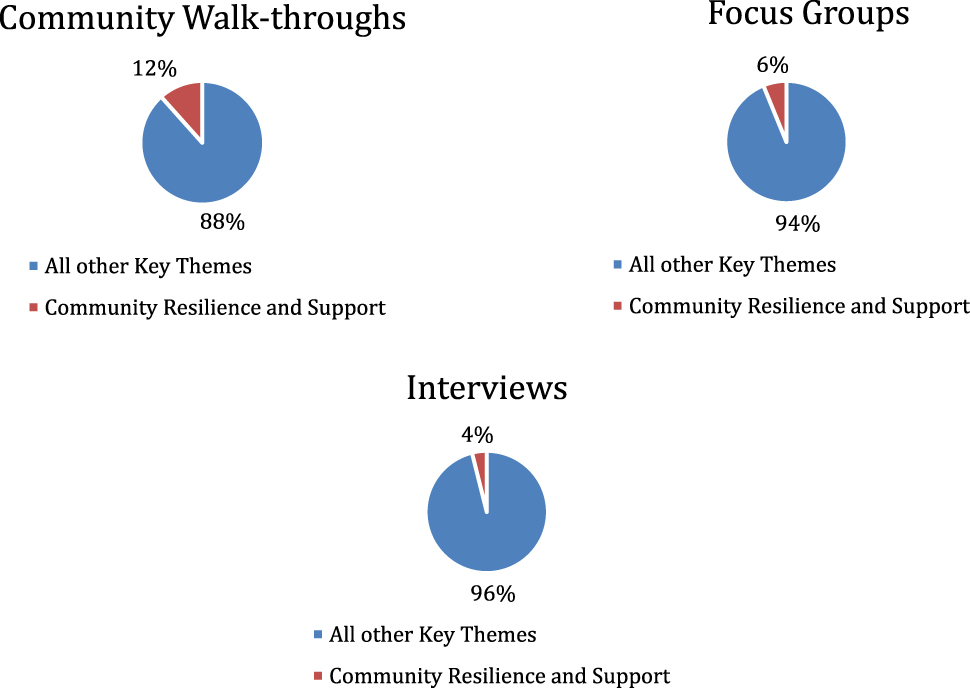

3.7 Group Settings Might Encourage More Group-Minded Solutions

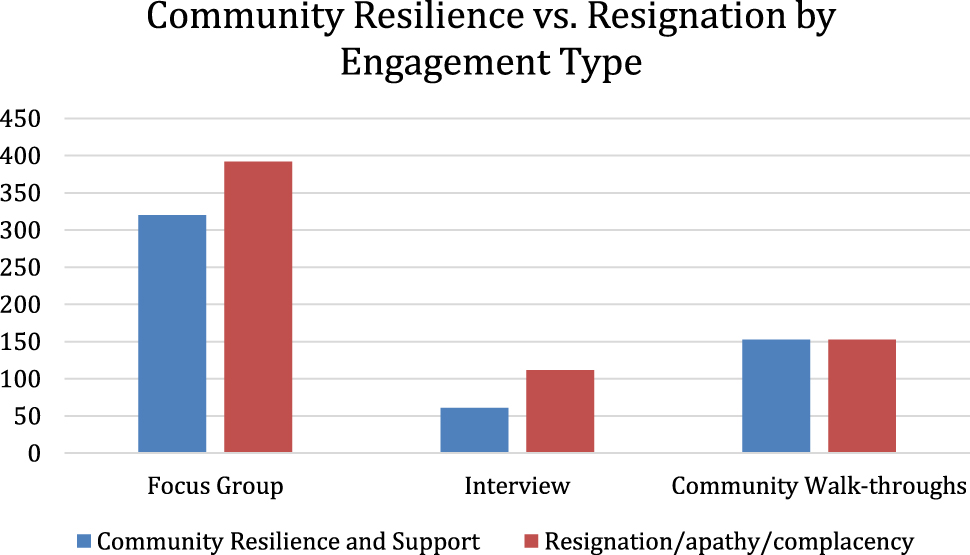

Figure 5 indicates that as a percentage of all key themes, the theme of community resilience was more prevalent in community walk-throughs, followed by focus groups, and least so in interviews.

Community resilience by engagement type.

This could suggest that isolated populations that do not typically participate in civic engagements may be more accustomed to relying on local ingenuity to address unique challenges specific to their communities. Community walk-throughs also drew out some creative (though not always optimal) ideas that were not mentioned in any other data sources examined:

The water eventually came back on, but the community was still without power most of the time. The electric company eventually came but they only dropped off the poles and didn’t come back for months. The community grew so frustrated that they all pooled their resources and hired a private electric company to install the poles in the ground.

The community should identify needs and plan. For example, a volunteer to read to illiterate people how to cook MREs … and a mechanism for the community to take photos and provide “pins” to downed poles or other issues needed to be reported.

But they need to organize within the community that people volunteer to get the food and take it up to those who are not mobile. They would figure out a way to deliver it to the last step. The govt. only goes to one point. It’s understandable, but still not enough.

The data supports past studies that advocate for casting a wide net to harvest ideas from a diverse range of stakeholders. Emergency managers and recovery practitioners can use information collected during community walk-throughs to develop tailored approaches to recovery, especially when access is limited, and resources are constrained or otherwise overwhelmed. Additionally, group dynamics in both focus groups and community walk-throughs can be persuasive. By designing a format that gathered people together to think collectively about recovery solutions, views may have veered more toward community-minded needs and actions. To this point, one-on-one interviews also mentioned community resilience, but views tended to be more individualistic in nature and often emphasized the importance of identifying local leaders to guide communities out of despair:

Question: Any help you consider pertinent for the preparation of future hurricanes?

There are many innate leaders to help organize and prepare a community plan.

Activate, work and enrich the community leaders, which is important, in my opinion. Without them, Conexion Caribe wouldn’t have been able to do anything right, because we do not belong to the communities. You have to activate them and offer leadership, preparation, resources, workshops, and make them the protagonists, because these people will offer us the information when we need it, they will save lives and will help support. The communities that were actively working on the emergency were those who had strong leaders. We must help them and create a program so that all community leaders can meet every month and create strategies. We must fortify them and offer tools to improve their leadership.

We should try to take the message to our community, that there is not just one community leader, but we are all leaders. We should be in charge, not just the agencies. We are all leaders.

Basically, thanks to God, the communities count on religious leaders, as well as institutions…

Taking in consideration the example of Hurricane Maria, if I may answer it like this, we realized how many leaders live in the community. Maybe because they are known, or we have heard of them on the radio, but the reality is that I am no one without the people who are leaders in the community. Those whom I saw made paths in midst the hurricane, got families out of their houses and took them to their own because the houses were going to fly, so in those ways one could identify the leaders who, in moments of crisis, act at a level in which they forget their own families and just work for the community.

Reducing the impact of natural disasters requires both local leaders and action-oriented communities to play a role. Discussions that took place in different engagement types highlighted the value of both.

While thoughts about community resiliency were present in all forums, Figure 6 shows that pessimistic viewpoints also emerged. Feelings of resignation, apathy and complacency were readily expressed in each engagement type. However, the reasons behind some of these negative views differed to some degree.

Comparison of community resiliency and pessimistic themes.

For example, interviewees tended to express frustration with apathetic communities. In an interview with emergency responders operating in the mountainous region of Barranquitas, the conversation turned toward community members disinterested in getting involved in hazard mitigation efforts.

“Community emergency training existed before Maria. PREMA did this. Also community emergency response teams fielded by FEMA go out and conduct community emergency training. But the community has to request it and coordinate the training event which are typically held in local schools or churches over a three-day period. Few communities put out the effort to seek this resource.”

A government official interviewed noted a sense of public apathy regarding the recovery process:

These community forums are for Puerto Rico, the Boys and Girls club requested for us to organize these forums at their centers, available to the public, to receive comments … but at the most we had 20 participants in a meeting, sometimes only one. An issue as important as receiving $20 B assistance should receive more attention from the local communities, NGOs and small businesses … For the last six days, we led town hall meetings in Bayamon, Cidra, Caguas, Mayaguez and Arecibo to orient the population and organizations. We need to know if the plan is conclusive and approaches all our needs. But [] feedback is necessary. Only three people attended today’s meeting. But we are still criticizing the government’s approach.

It is noteworthy that no one who participated in a focus group or community walk-through mentioned these hazard mitigation and recovery opportunities. This might point to a lack of awareness among communities about the resources at their disposal, suggesting emergency managers should find ways to better advertise different disaster resiliency-building opportunities.

The data also indicates that communities bear some responsibility. Some focus group participants acknowledged they could do more to become proactive contributors to island resiliency:

We prepared like previous years. Like she said, we lived through Georges. The difference with Georges is that it didn’t hit the entire island. Everything happened so fast and we had forgotten. Every year it was the same thing. People would wait, and wait, and wait, and it would never hit us. Even though we tried to prepare, or not, we would have never been prepared for a hurricane of this magnitude because we’ve never lived through something like this.

In this country, we are accustomed for everything to be given to us … In the sense that, when eventualities such as this happen, there are people who sit back to wait for the municipal county to come and pick up the debris, and for them to give them the support to cover the house or to tie it up. If someone brings me supplies, then I don’t have to go out to buy them. I understand that, yes, there are people who are designed to give and that there are people who are designed to receive, but if I start to awaken the survival instinct in those people who lie down to simply wait for everything to be given to them, they’re not going to be a burden.

Q. Do you know which is your evacuation site in a hurricane?

1 – no that’s a problem, you have to go find a list.

M – right that’s why.

1 – yes on that list provided by the municipality but the person has to go to them, they don’t come to you.

Above all, we have a responsibility as individuals. It’s not that the government has to give to me. No, because we know that the government has its own crisis and its own problems. Therefore, we have to be able to cope with situations and handle them as individuals … I wouldn’t wait on FEMA or other people to come to my aid. I think the responsibility is of each and every one of us. We have to work towards that; I believe that’s how it is.

Hurricanes are disruptive, destructive, and can test the limits of all parts of society. The larger point, and the one we seek to underscore in this study, is that different modes of engagements can illuminate different aspects of recovery challenges and opportunities. That said, our analysis also suggests that some views are cross-cutting no matter the engagement type.

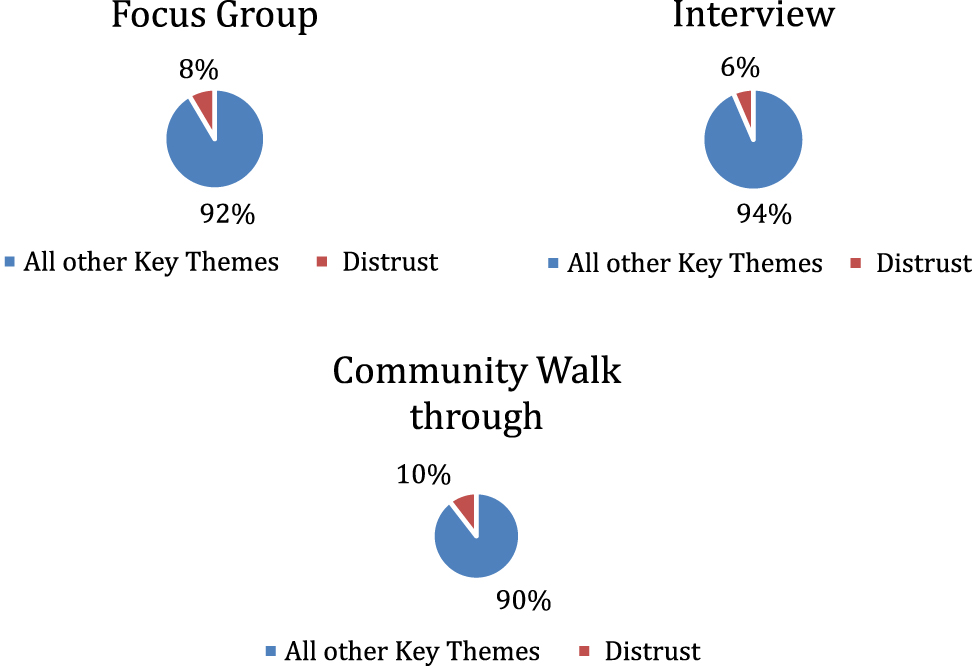

3.8 Distrust in Government Performance Prevails in All Engagement Types

We coded for one potentially controversial theme: public distrust in the government. We hypothesized that people might feel more comfortable discussing negative views of the government in one-on-one interview settings. Instead, participants discussed distrust in government performance in all three settings and in similar percentages (Figure 7). Several factors might be at play: (1) the universally destructive nature of Hurricane Maria made it such that no topic was off limits. (2) Participants might have felt an adequate level of trust in the local NGOs who facilitated these engagements or (3) expressing negative views of the government is simply not as delicate issue as we presumed.

Perceptions of distrust by engagement type.

Participants cited many reasons for feeling distrustful of the government. Frustration with slow-moving recovery and a lack of transparency in government decisions were two common themes mentioned in all engagement types. Yet another reason cited was the lack of sincere government efforts to reach out to communities in need. For example, one subject matter expert interview noted:

The key is engagement, that’s a very long and slow process. There is mistrust between some groups of residents and governmental response organizations like FEMA. FEMA says disaster response uses whole community approach – but in marginalized communities many feel saying “whole community” excludes them. Need engagement with marginalized communities in planning process.

In a focus group in an isolated community in the mountains, one prospective participant chose to leave prior to the start of the discussion after sharing his skepticism that his comments would make a difference. Another gentleman who chose to stay had the opposite reaction:

I think, in fact, I know why I’m here today. I hoped to start this process. I was really surprised by this with the Rand Corporation and Homeland Security and I think that’s why the gentleman left like that, because to be honest … I came here for two reasons: one, to meet my responsibility towards you and the other to see if we can do something, right? Or if there’s going to be something here between us, because you’re the people who are going to help with the next hurricanes. That’s right, isn’t it? It’s you…

During a community walk-through in an isolated part of Arecibo, one woman caring for her two children and bedridden husband expressed gratitude that our research team visited her community to gain an appreciation for the challenges they face.

They should come out and see what’s really happening to the people. Like what you’re doing today. Go out and see the people. To be closer to the people to see what the real problems are. There are neighbors who still don’t have water. My husband needs, diapers, a wheel chair, etc. and luckily the community has come together to do a donation for him to raise money for medical needs. It’s the people of this neighborhood. It’s not the govt. that helps.

In each type of engagement type, participants emphasized the value of reaching into the community to establish trust and gain a better understanding of conditions on the ground.

4 Conclusion: A Multifaceted Strategy for Improving Community Engagement

Engaging communities in meaningful conversations about local risks and the personal actions that can help mitigate against those risks is an essential part of disaster preparedness and recovery. So, what types of information are best collected using what kinds of methods? We found that no single approach will independently capture all perspectives. Rather, the evidence shows that different community engagement formats shed light on distinct aspects of recovery concerns, needs, hopes and aspirations. Focus groups can foster lively discussions that produce a significant number of data points in a relatively short period of time. The group dynamic might also fortify community bonds and encourage civic-minded solutions to address future disasters. Community walk-throughs offer opportunities to elevate the voices of the most vulnerable populations to ensure that future response and recovery efforts factor in their unique needs. Interviews reinforced the notion that community actors can’t act alone; they need individual leaders to help guide and manage a successful recovery. The varied engagement approaches and subsequent responses suggest emergency managers and first responders should aim to launch a multi-faceted engagement strategy to illuminate alternative narratives regarding the disaster experience, while encouraging communities to actively participate in the decisions that most affect their lives.

References

Abraham, M., A. Eckert, J. Isaac, J. Logan, L. Amy, E. Marr, M. I. Shannon, J. Medeiros, K. Procter, R. Sissons, and W. Adam. 2007. Guidelines for Engaging the Public Post-disaster. School of Environmental Design and Rural Development Program University of Guelph. Also available at http://www.waynecaldwell.ca/Students/Projects/PublicEngagement_FINAL1.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Agar, M., and J. MacDonald. 1995. “Focus Groups and Ethnography.” Human Organization 54: 78–86. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.54.1.x102372362631282.Suche in Google Scholar

Albrecht, T., G. Johnson, and J. Walther. 1993. “Understanding Communications Processes in Focus Groups.” In Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the State of the Art, edited by D. Morgan, 51–64. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.10.4135/9781483349008.n4Suche in Google Scholar

Aldag, L., and A. Tinsley. 1994. “A Comparison of Focus Group Interviews to In-Depth Interviews in Determining Food Choice Influences.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Information 2: 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1300/J108v02n03_11.Suche in Google Scholar

Barton, M. A. 2018. FEMA Hopes to Embed Staff in Local Communities. NACO.org. Also available at https://www.naco.org/articles/fema-hopes-embed-staff-local-communities.Suche in Google Scholar

Boateng, W. 2012. “Evaluating the Efficacy of Focus Group Discussion (FGD) in Qualitative Social Research.” International Journal of Business and Social Science 3 (7): 54–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Clinton, W. J. 2006. “Key Propositions for Building Back Better, Lessons Learned from Tsunami Recovery,” A Report by the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for Tsunami Recovery, p. 4. Also available at https://www.preventionweb.net/files/2054_VL108301.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Coenen, M., T. A. Stamm, G. Stucki, and A. Cieza. 2012. “Individual Interviews and Focus Groups in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Comparison of Two Qualitative Methods.” Quality of Life Research 21: 359–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9943-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Couzos, S., T. Lea, R. Murray, and M. Culbong. 2005. ““We are Not Just Participants–We are in Charge”: The NACCHO Ear Trial and the Process for Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Research.” Ethnic Health 10: 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850500071038.Suche in Google Scholar

Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management. 2010. Community Engagement in the CDEM Context Civil Defence Emergency Management: Best Practice Guide [bpg/10]. New Zealand: Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management. Also available at https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/publications/bpg-04-10-community-engagement.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Edwards, K., C. Lund, S. Mitchell, and N. Andersson. 2008. “Trust the Process: Community-Based Researcher Partnerships.” Pimatisiwin 6 (2): 186–99.Suche in Google Scholar

FEMA. A Whole Community Approach to Emergency Management: Principles, Themes, and Pathways for Action FDOC 104-008-1/December 2011, p. 2. Also available at https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1813-25045-3330/whole_community_dec2011__2_.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Gamboa-Maldonado, T., H. H. Marshak, R. Sinclair, S. Montgomery, and D. T. Dyjack. 2012. “Building Capacity for Community Disaster Preparedness: A Call for Collaboration between Public Environmental Health and Emergency Preparedness and Response Programs.” Journal of Environmental Health 75 (2): 24–9.Suche in Google Scholar

Goodman, M. S., V. L. Sanders Thompson, C. A. Johnson, R. Gennarelli, B. F. Drake, P. Bajwa, M. Witherspoon, and D. Bowen. 2016. “Evaluating Community Engagement in Research: Quantitative Measure Development.” Journal of Community Psychology 45 (1): 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21828.Suche in Google Scholar

Greenbaum, T. 2003. “The Gold Standard? Why the Focus Group Deserves to be the Most Respected of All Qualitative Research Tools.” Quirk’s Marketing Research Review 17: 22–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Guest, G., E. Namey, J. Taylor, N. Eley, and K. McKenna. 2017. “Comparing Focus Groups and Individual Interviews: Findings from a Randomized Study.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 20: 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1281601.Suche in Google Scholar

Heary, C., and E. Hennessy. 2006. “Focus Groups Versus Individual Interviews with Children: A Comparison of Data.” The Irish Journal of Psychology 27 (1): 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/03033910.2006.10446228.Suche in Google Scholar

IAP2 International Federation. 2014. IAP2’s Public Participation Spectrum. Also available at https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/foundations_course/IAP2_P2_Spectrum_FINAL.pdf; “Community Planning Toolkit” Community Places, BIG Lottery Fund, 2014: www.communityplanningtoolkit.org.Suche in Google Scholar

IFRC. 1994. The Red Cross Code of Conduct for Disaster Relief. Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaplowitz, M. 2000. “Statistical Analysis of Sensitive Topics in Group and Individual Interviews.” Quality & Quantity 34: 419–31. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004844425448.10.1023/A:1004844425448Suche in Google Scholar

Kaplowitz, M., and J. Hoehn. 2001. “Do Focus Groups and Individual Interviews Reveal the Same Information for Natural Resource Valuation?” Ecological Economics 36: 237–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00226-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Kelly, J. G., L. O. Mock, and D. S. Tandon. 2001. “Collaborative Inquiry with African-American Community Leaders: Comments on a Participatory Action Research Process.” In Handbook of Action Research, edited by P. Reason, and H. Bradbury, 368. London: Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Kidd, P., and M. Parshall. 2000. “Getting the Focus and the Group: Enhancing Analytical Rigor in Focus Group Research.” Qualitative Health Research 10: 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973200129118453.Suche in Google Scholar

Minkler, M. 2004. “Ethical Challenges for the “Outside” Researcher in Community-Based Participatory Research.” Health Education Behavior 31: 684–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104269566.Suche in Google Scholar

National Response Framework. 2013, 2nd ed. Department of Homeland Security.Suche in Google Scholar

Office of the Governor of Puerto Rico. 2018. Transformation and Innovation in the Wake of Devastation: An Economic and Disaster Recovery Plan for Puerto Rico. Also available at https://recovery.pr/documents/pr-transformation-innovation-plan-congressional-submission-080818.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Ramsbottom, A., E. O’Brien, L. Ciotti, and J. Takacs. 2017. “Enablers and Barriers to Community Engagement in Public Health Emergency Preparedness: A Literature Review.” Journal of Community Health 43 (2): 412–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0415-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Reimagina Puerto Rico Report. 2018. Resilient Puerto Rico Advisory Commission, San Juan, Puerto Rico. Also available at http://www.resilientpuertorico.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/RePR_GENERALREPORT_WEB_ENG_10022018.pdf. 99.Suche in Google Scholar

Roe, K. M., M. Minkler, and F. F. Saunders. 1995. “Combining Research, Advocacy and Education: The Methods of the Grandparent Caregiving Study.” Health Education Quarterly 22 (4): 458–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819502200404.Suche in Google Scholar

Schulz, A. J., B. A. Israel, and P. Lantz. 2003. “Instrument for Evaluating Dimensions of Group Dynamics within Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships.” Evaluation and Program Planning 26: 249–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-7189(03)00029-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Sullivan, M. 2003. “Integrated Recovery Management: A New Way of Looking at a Delicate Process.” The Australian Journal of Emergency Management 18 (2): 4–27.Suche in Google Scholar

Towe, V. L., L. Elizabeth, P. Sayers, E. W. Chan, A. Y. Kim, A. Tom, W. Y. Chan, J. P. Marquis, M. W. Robbins, L. Saum-Manning, M. M. Weden, and L. A. Payne. 2020. Community Planning and Capacity Building in Puerto Rico After Hurricane Maria: Predisaster Conditions, Hurricane Damage, and Courses of Action. Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center operated by the RAND Corporation. Also available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2598.html.10.7249/RR2598Suche in Google Scholar

Wells, K. B., B. F. Springgate, E. Lizaola, F. Jones, and A. Plough. 2013. “Community Engagement in Disaster Preparedness and Recovery: a Tale of Two Cities--Los Angeles and New Orleans.” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 36 (3): 451–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2013.05.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Wight, D. 1994. “Boys’ Thoughts and Talk about Sex in a Working Class Locality of Glasgow.” Sociological Review 42: 703–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954x.1994.tb00107.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Wright, K. N., P. Williams, S. Wright, E. Lieber, S. R. Carrasco, and H. Gedjeyan. 2011. “Ties That Bind Creating and Sustaining Community Academic Partnerships.” Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement 4: 83–99. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v4i0.1784.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Best Practices and Lessons Learned from Community Engagement and Data Collection Strategies in Post-Hurricane Maria Puerto Rico

- Stochastic Modeling of Non-linear Terrorism Dynamics

- Opioid Crisis Response and Resilience: Results and Perspectives from a Multi-Agency Tabletop Exercise at the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency

- Access and Inclusion in Emergency Management Online Education: Challenges Exposed by the COVID-19 Pivot

- Opinion

- What COVID Teaches Us About Homeland Security: How Not to be the Mouse

- Reframing Risk in the Wake of COVID-19

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Best Practices and Lessons Learned from Community Engagement and Data Collection Strategies in Post-Hurricane Maria Puerto Rico

- Stochastic Modeling of Non-linear Terrorism Dynamics

- Opioid Crisis Response and Resilience: Results and Perspectives from a Multi-Agency Tabletop Exercise at the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency

- Access and Inclusion in Emergency Management Online Education: Challenges Exposed by the COVID-19 Pivot

- Opinion

- What COVID Teaches Us About Homeland Security: How Not to be the Mouse

- Reframing Risk in the Wake of COVID-19