Abstract

This paper focuses on the visual depiction of children venturing into space in China during the late 20th century. I investigate how children are portrayed in Chinese posters and their space exploration themes by comparing them with similar art forms in the Soviet Union and the United States during the 1950s–1980s. Moreover, the study examines how these posters both shaped and reflected the political, social, and gender discourses of the period and served as means of reinforcing the reproductive future while interacting with Chinese historical myths. The study also considers the motivations for including chubby babies in Chinese posters, noting that this primarily resulted from Chinese moral beliefs. By historicizing the meaning-making process behind the “space babies” in Chinese posters, I argue that the depiction of children venturing into space helped in two distinct ways. First, it helped shift traditional immortality ideology into new forms of living and delimit the Chinese’s vision of the reproductive future: a desire to create better futures for our children/humanity by participating in politics. Furthermore, these visualizations apply the form of children as citizens to represent the mother country’s wishes while reflecting the corresponding Chinese national policy and fear of anthropic population expansion.

Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see. (Postman, 1994)

That figural Child alone embodies the citizen as an ideal, entitled to claim full rights to its

future share in the nation’s good, though always at the cost of limiting the right ‘real’ citizen are

allowed. (Edelman, 2004)

1 Introduction

On December 11, 2022, NASA’s Orion spacecraft splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, returning with it data intended to help NASA with its future mission of sending astronauts to the moon’s orbit and surface—something not done since Apollo 11 first landed on the moon in 1961 (Chang, 2022). Interestingly, less than 2 weeks before the Orion spacecraft’s return, China launched a rocket sending three astronauts to its newly completed space station as part of the country’s Shenzhou 15 mission (Bradsher, 2022). Although there has been a recent resurgence in space exploration at the international level, China’s space program propagation began as early as the 1950s through various visual images.

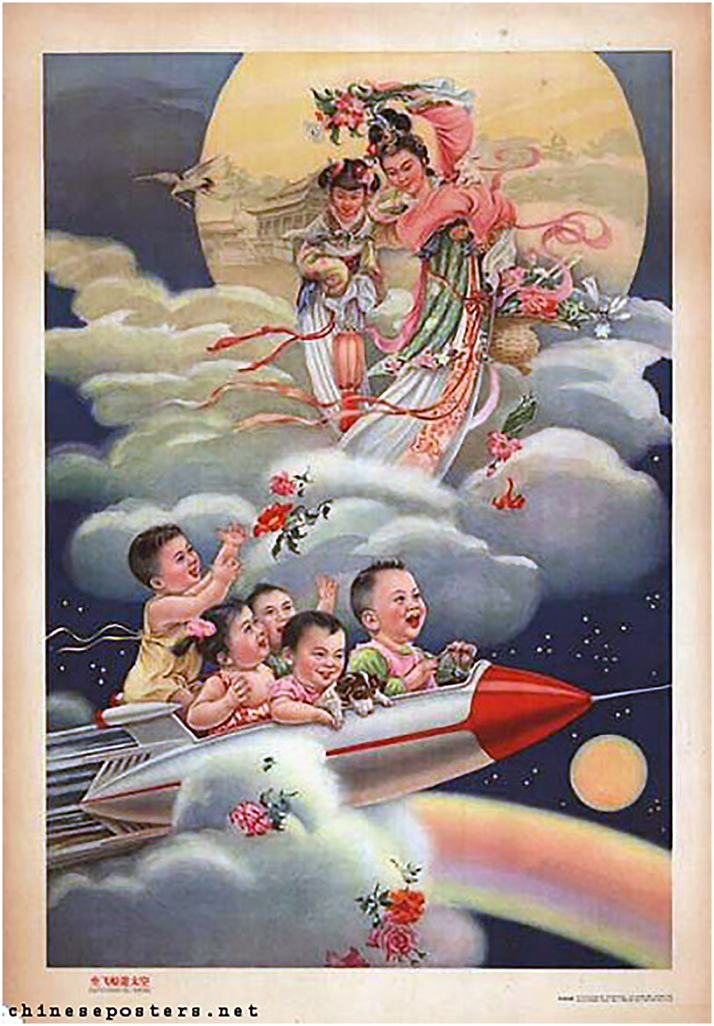

This paper examines visual depictions of children venturing into space during the late twentieth century in China (Figure 1). More specifically, it focuses on the period when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) adopted a comprehensive framework for the modernization of science and technology—the foundation for China’s current massive investment in space. By historicizing the meaning-making process behind the “space babies” in Chinese posters, I argue that the depiction of children venturing into space assisted the state in two distinct ways. First, it helped shift traditional immortality ideology into new forms of living and, in turn, delimit the Chinese’s vision of the reproductive future: a desire to create better futures for our children/humanity by participating in politics. Second, these visualizations apply the form of children as citizens to represent the mother nation’s wishes while reflecting the corresponding Chinese gender ideology and fear of anthropic population expansion.

Little guests in the Moon Palace, Designer unknown, 1972, Landsberger Collection.

I investigate how children are portrayed in Chinese posters and their space exploration themes by comparing them with similar art forms in the Soviet Union and the United States. The study also considers the motivations for interacting with Chinese historical myths and the inclusion of chubby babies in Chinese posters, noting that this primarily resulted from traditional moral beliefs. Moreover, the study examines how the posters both shaped and reflected the political, social, and gender discourses of the era and served as means of reinforcing the reproductive future. This paper is based on an analysis of 20 Chinese posters on “space babies” produced from the mid-1950s to the late-1980s. These posters were obtained from the Landsberger collection at Chienseposter.net and other social media sources. It is not an exhaustive list of posters, but they represent their thematic and periodic distribution.

2 Contextualizing Chinese Posters

Posters produced for diffusion do not necessarily reflect reality; they are merely sanitized versions of it or even glimpses into an idealized future that may have taken place in the past (Henriot & Yeh, 2012). The use of posters for spread is not exclusive after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. Before 1949, posters had played a supportive role in promoting the Communist revolutionary story during the Yan’an era. At first, posters were used only within the Communist Party. However, they slowly shifted to public use and attained their highest peak during the 1960s and 1970s Cultural Revolution. The broad themes of the poster included various political, economic, and social subjects such as birth control, traffic safety, national policy, and the promotion of political events. Likewise, posters were used as a marshaling strategy in the United States and Britain during the world wars to recruit soldiers (particularly women, minorities, and children; Nelson, 2015).

Chinese posters are closely tied to the aim of politics. At the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art in 1942, while discussing Chinese art’s future pathway, Mao Zedong rejected the notion of “art for the art’s sake,” that is, rejecting any notion of art above class or art independent of politics. He summed up his expectations of revolutionary literature and art by stating, “What we demand is a unity of politics and art, a unity of content and form, a unity of revolutionary political content and the perfect artistic form possible” (McDougall & Mao, 1980).

In the period covered by this study, the 1950s–1980s, poster production reached its height, which was important for three reasons. First, it occurred during the early stages of the PCR’s nation-building process, and posters were primarily used to support this effort. Second, the 1950s marked a period when China began developing its space program with the assistance of the Soviet Union. Finally, the Chinese media was transitioning between printed matter and electronic media during this time.

The posters in the study are typically measured 21–30 inches, sometimes including a white margin around the image. Most posters supply the names of the artists, the publisher, the printer, and the distributor, as well as the number of the prints (from a few thousand to two or three million) and the publication date (Landsberger, 1998). They were usually sold in local bookstores and could be hung in domestic or public spaces. Whether time makes a difference to these “space babies” posters is difficult to determine. Many of these depicted children share similar characteristics: strange smiles, chubby and fat, and frequently travel in groups on spacecraft.

The effectiveness of this visual printed matter was closely associated with Chinese literacy at that time and its traditional belief in the potency of imperceptible inculcation. The popularity of the posters was synchronized with the campaign to eradicate illiteracy, one of the most successful outcomes of Chinese educational policy since 1949. Some of the posters were picture-based with text as a supplement. Even though the percentage of illiterate Chinese dropped from over 80 % before 1949 to 20.6 % in 1987, despite wide-ranging fluctuations in policy, posters still served as a significant means for educational purposes (Peterson, 1992). The Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE) presents the concept of the “malleability of man,” believing that persuasion and education are more effective than punishment or force in creating a state of harmony in society (Landsberger, 1998). Mencius (372–289 BCE) similarly believed that when presented with examples of impeccable moral qualities, human beings are inherently inclined to modify their behavior.

Therefore, posters provided societal role modeling of responsible citizens under socialism. The apparatuses translate and develop the ideas promoted by the CCP into appropriate images based on the learning objects created. Setting up a model has become a “method of leadership” for the Chinese government (Landsberger, 1998). According to Confucius, a model’s greatest reward should be the respect of those who emulate him (Landsberger, 1998). As a result, everyone wanted to be a model, and posters with the nature of a model became stimuli for people to develop new behaviors.

Although the posters prominently depict children, the subject matter itself does not only pertain to modern China. Previously, children were occasionally and randomly depicted in Chinese art, but they have become increasingly prominent since the Song period (960–1279). Throughout China, child imagery has been exceptionally meaningful to generations of people at all levels of society (Wicks, 2002). However, the poster depicted distinct children as astronauts flying into outer space in Chinese art history for the first time.

Viewing such images from a contemporary perspective, even though Lee Edelman presents the utilization of child images as a sign of heteronormality, Edelman calls our attention to how powerfully all political visions of the future are invested in “the imaginary form of the child.” Following Lauren Berlant, Edelman identifies this new era in “the fascism of the baby’s face” (Edelman, 2004). The children’s smiles indicate an optimistic attitude about the future. However, at the same time, they are so similar and rigid that it is a bit frightening as if this “happiness” is achieved through passive political means.

In the 1950s, when China began to develop its space program with the assistance of the Soviet Union, posters featuring an outer space theme gradually emerged. Even though some posters only depict outer space settings, most depict children traveling to outer space. Later on, the decline of posters in the late 1980s was propelled by the shift in focus to economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping, which directly led to television’s popularization.

3 “Space Babies” Posters During the Cold War

“Space babies” are best understood as iconographic images in Chinese posters in the context of Cold War politics. In the years following World War II and until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989, the Cold War involved a half-century-long conflict between capitalism (represented by the United States and Western Europe) and socialism (represented by the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba; Immerman & Goedde, 2013). The so-called Space Race was regarded as a battleground between two superpowers, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Moscow and Washington boldly announced their scientific developments, particularly on space-related topics, such as satellite launches. China had a complex role as a side player in the Cold War.

After the establishment of China in 1949, the country pursued a “one-sided” foreign policy and moved closer to socialism. The bilateral treaty Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance was signed between China and the Soviet Union in 1950, which ensured the Soviet Union provided China with a great deal of technical assistance for scientific development. The relationship between China and the Soviet Union deteriorated in 1958 when Mao discovered that the Soviet Union was making unreasonable demands and attempting to control China militarily. Khrushchev later recalled the scientists who had remained in China and revoked various agreements relating to economic and technical cooperation between the two countries 1 year after (Shen & Xia, 2012). Until 1980, China and the Soviet Union had poor relations. Therefore, during this period, the Chinese space program developed independently, and the “space babies” posters became prevalent along with it.

It is worth asking whether there are any particular reasons for China’s interest in space exploration other than an attempt to gain a strong face and compete with the two large global powers at the time. The history of China reveals that the pursuit of similar grandiosities has always dominated its development. The following examples illustrate this peculiar feature: The royal garden of the Emperor Wu of Han (156–87 BCE) contained hundreds of architectural elements and more than 3000 species of rare plants from every corner of China, aiming to offer a reproduction of the emperor’s kingdom; Yungang and Longmen Grottoes of the following Wei dynasty (386–535) are renowned for their technical capacity and religious grandeur; the majestic capital city of the Tang Dynasty (618–907), Chang’an; the 980 buildings forming the Forbidden City, built through the mobilization of one million workers immediately after the establishment of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644); the contemporary hydroelectric gravity dam Three Gorges Dam (Aliberti, 2015). As with the construction of China’s ancient capital 2000 years ago, the outer space project may prove to be one more grand undertaking and a symbol of collective self-esteem, thus representing the nation, its unity, and its reproductive future.

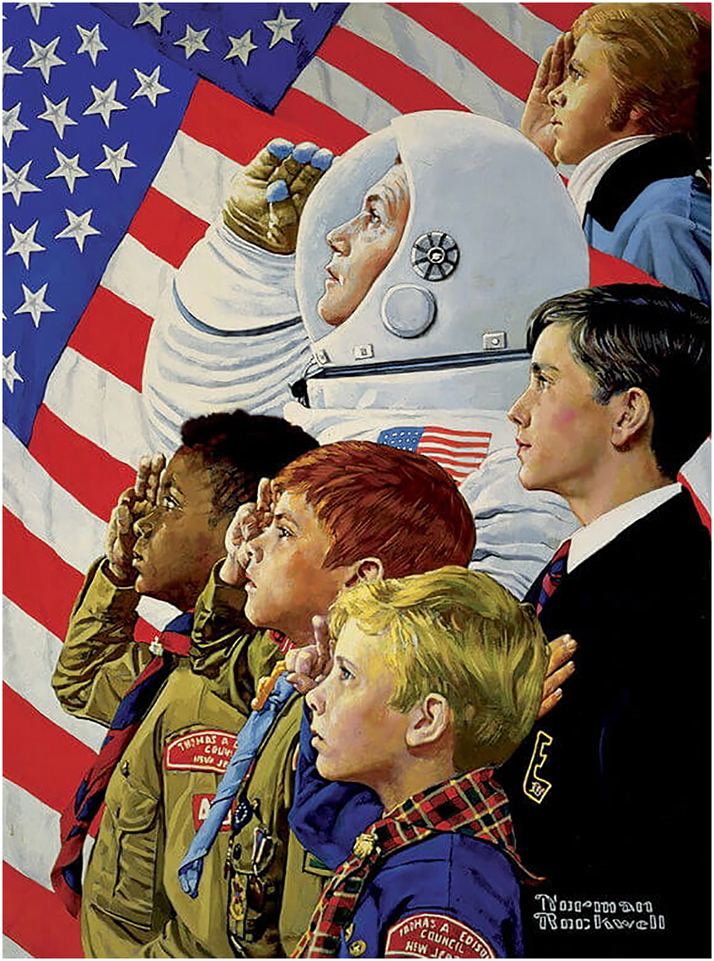

The USSR and the United States offer differing cosmological altitudes regarding children depicted visually during the Cold War. For the Soviet Union, children of the 1960s did not dream of becoming doctors and lawyers but cosmonauts (Figure 2; Bartos & Boym, 2001). The cosmonauts and the children in the posters represented not just one self’s personality but the entire Soviet population. The child cosmonauts’ facial features were barely discernible. Therefore, the MASS was represented. In the United States, after President Kennedy’s speech on space in 1961, NASA started to work harder in the Space Race to send Americans to the moon (Figure 3; Garber, 2013). American posters depict astronauts as ready to fight and the children are depicted as soldiers as well. Man is seen as part of the totality and represents a metaphor for his nation. Therefore, individuality is emphasized more strongly. Yet, in the case of the USSR and the US, children depicted in visual posters in outer space were not a prevailing and distinctive theme during the Cold War. Most of the space themes they depict are imaginary space scenes and adult astronauts.

Young Technician, R. Avotin, 1968, the Moscow Design Museum.

From Concord to Tranquility, Norman Rockwell, 1971.

However, even though the USSR did not depict children in outer space much, the Chinese and Soviet posters are more similar in terms of depicting children in outer space than in the United States. Due to both historical and political factors, they were more concerned with collective identity during that period. Historically, paintings depicting a group of children playing together were an established theme during the Song dynasty (960–1279; Wicks, 2002). Many of them were named “baizitu” (百子图, which means “pictures of a hundred boys”), depicting boys playing in a garden outside. Furthermore, China has been allied with the Soviet Union since its founding and has promoted Marxism-Leninism as the guiding ideology of the Chinese Communist Party.

Overall, the use of posters of “space babies” as a theme for promoting the space program is unique to China and started to become prevalent when China broke up with the USSR during the Cold War. Collective characteristics are evident in them, related to the traditional Chinese belief that “the collective can achieve greater productivity.” The ability to regenerate serial is also emphasized when collective characteristics are placed in children’s facial features, enacting a logic repetition that fixes identity through identification with the future of social order (Edelman, 2004).

4 “State of Being Immortal”: Myth and Future Utopianism

Among the most evident differences between Chinese posters and others is the representation of mythology, often depicting the Chinese aspiration to become immortal. As a result of the combination of this traditional mythological theme with the futuristic Space Project, these “space babies” posters redefine Chinese conceptions of immortality into new forms of living and define the Chinese vision of the reproductive future.

In traditional Chinese ideology, human physical bodies are regarded as the sole mode of survival and replicas of the cosmos, originally indestructible and replicating the universe. An early classical passage on this understanding of eternal life can be found in the words of Guang Chengzi in Zhuangzi. This famous book contains stories and anecdotes illustrating the carefree attitude of the ideal Taoist sage:

Let there be no seeing, no hearing; enfold the spirit in quietude, and the body will right itself. Be still, be pure, do not labor your body, do not churn up your essence, and then you can live a long life. When the eye does not see, and the ear does not hear, your spirit will protect the body, and the body will enjoy long life … You only have to take care and guard your own body; the other things will grow sturdy. As for myself, I guard the One, abide in harmony, have kept myself alive for twelve hundred years, and never has my body suffered any decay. (Zhuangzi, 1969)

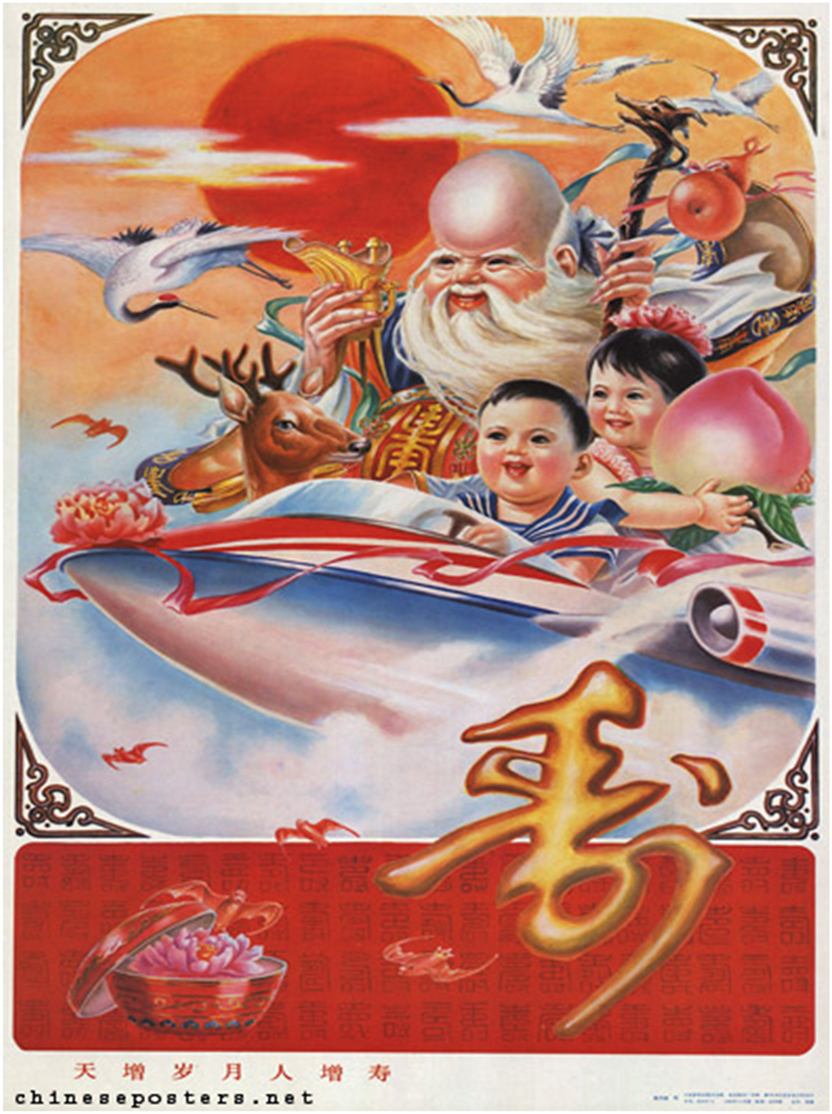

Although Buddhism and Confucianism both were popular in China, these mythology stories in the posters originated from Taoism, which claims the nature of immortality and transcendence. In the poster “Heaven Increases the Years, Man Gets Older” (1989) (Figure 4), the long-lived immortal and transcendental being Pengzu is depicted (Birrell, 1999). He is seated on the back of a deer holding a glass of wine in his right hand and a cane in his left hand. Two young children (one girl and one boy) ride the spacecraft in the front ground. The symbol “ ” is embroidered in gold on the front of his clothes, indicating longevity. Around them are red-crowned cranes, which symbolize long life, and flying bats, which represent good luck and happiness. The parallel relationship between the immortal and the children indicates that the children might also live eternally.

” is embroidered in gold on the front of his clothes, indicating longevity. Around them are red-crowned cranes, which symbolize long life, and flying bats, which represent good luck and happiness. The parallel relationship between the immortal and the children indicates that the children might also live eternally.

Heaven Increases the Years, Man Gets Older, Chen Nai’liang, 1989, Landsberger Collection.

The Chinese character for hsien, “immortal” or “transcendent,” can be written either 仚 or 仙: both graphs depict a man (人) on a mountain (山; Kohn, 1990). In the “space babies” posters, the spatial relationship between the top and bottom between the immortal (the man) and the ground is also indicated. For example, in the poster “Soar, Youth of the New China! On the Rocket – China’s Youth No. 1” (Figure 5), the scene of the ancient legend of a Chinese goddess residing on the Moon is illustrated.

Soar, Youth of the New China! On the Rocket – China’s Youth No. 1, Designer and date unknown.

The goddess Chang’e is one of the most celebrated figures of Chinese mythology and popular culture, and every year her story is remembered at the well-attended Moon Festival. Several variations of the legend exist, but according to the most popular version, Chang’e was a beautiful woman who, after stealing the elixir of immortality from her husband, the great hero Yi, became immortal and flew to the moon, where she lives forever with Yutu, a Jade Rabbit (Birrell, 1999). It is important to note that this up-and-down spatial relationship in the posters is not only determined by the position of the goddess and the children but also by the replicas of terrestrial architecture visible in the sky (Figure 1). Paradise was modeled on the brilliance of the earthly imperial courts, emphasizing palace architectural features (Birrell, 1999). Therefore, it implies that all life’s necessities on earth will also exist in the sky. People will be able to raise their children in heaven/outer space so kids can grow up and reproduce, and humanity will then be able to expand beyond the earth in the future.

However, the parents or other adults, usually serving as protective power for the children, were absent from any of the “space babies” posters in this collection. Although more often, children are portrayed in an idealized and timeless plane where all adults are absent in Chinese art history, sometimes children are portrayed with their mothers (Wicks, 2002). Hence, the lack of parenting protection in the Chinese posters is unusual. Possibly, since outer space is an external setting, family life is not depicted, as Craig Clunas and Richard Vinograd have demonstrated: perhaps artists and their audiences viewed family and family life as private and therefore shielded from public scrutiny (Wicks, 2002). So, in this case, on the one hand, the children might be depicted as a group that cares for one another. On the other hand, their rhetorical parent might be the nation that sent them into space, the Motherland-China.

Moreover, the absence of parents contributes to understanding the concept of a “prodigy.” The children are portrayed as prodigies who can drive aircraft and do things that children of this age cannot accomplish. According to Julia K. Murray, Chinese paintings have traditionally depicted prodigies, usually divided into three categories: god, sage, and scholar-official (Wicks, 2002). I claim that the Chinese poster depicts “space babies” as a fourth modern prodigy, a superhuman with a scientific dream, and children have become China’s means in the face of the Space Race. “Space babies” are used to demonstrate China’s scientific and political strength and hint at the future reproductive development and demographic expansion of human civilization.

These “space babies” have quite different superpowers than the “baby Jesus” paintings from the Midlevel Period, who had a strong muscular physique and resembled miniature human beings (Figure 6). In the case of the “space babies,” their superpower is reflected in the things they are unable to do at their age, such as flying a spacecraft. Even though the children are described as possessing superpowers, they still resemble chubby children around the age of three. One explanation from Richard Barnhart and Catherine Barnhart’s Images of Children in Song Painting and Poetry, featuring the chubbiness, indicates that the lightly clothed and chubby babies appear to have begun in China at the height of the Tang dynasty in Xi’an, the great Chinese city at the eastern terminus of the Silk Road (Wicks, 2002). The Silk Road connects the old Roman empire’s textiles, ceramics, jewelry, and gold and silver vessels of many kinds bearing decorative motifs from the Greco-Roman traditions. Therefore, it is possible that the Chinese artesian learned the chubby form from western paintings and sculptural deco depicting the image of chubby angels. However, in Chinese culture, there has been a widespread belief that excess body fat represents health and prosperity for men, women, and children since the Tang dynasty (Wu, 2006). Besides, infants are generally fatter than older children and adults, revealing a good health state. Hence, the origin of chubbiness remains questionable. Still, it is undeniable that chubby babies symbolize health and prosperity, which could be important factors for children to survive in outer space and contribute to their future reproductive potential.

Madonna and Child Enthroned, Domenico di Bartolo, 1436, Princeton University Art Museum.

5 Discourse of Gender

“Space babies” in Chinese posters effectively demonstrate the gender dynamics in China from the 1950s to the 1980s. The arrangement of the babies reveals it, the number of girls and boys, and the responsibility of each child. A subtle message is conveyed to the audience throughout this printed material that “a girl is the same as a boy.” It should be noted, however, that traditional Chinese ideologies of gender are barely marginalized.

Earlier in the paper, I noted that “baizitu” is a commonly used art form in Chinese art history. It is named after the “picture of a hundred boys,” developed from the basic wish for male progeny (Wicks, 2002). In order to symbolize male progeny, the baizi theme was used to decorate any object with a wish for a large number of children, particularly items for the bridal chamber, such as quilt covers, curtains, and valances. As a result of modernization, such images have become detached from functional objects, and printed matter has grown into the prevalent form for propagandizing the idea of patriarchy.

However, in modern Chinese posters, in addition to depicting boys, there will also be posters depicting girls individually or within a group. A major factor in the emergence of this novel and the groundbreaking phenomenon was the implementation of the one-child policy during this period, attempting to convince people that female offspring can have the same emotional value as male offspring. It was around 1950 when the Chinese government first began discussing the advantages of having one child in various meetings, which would facilitate the accumulation of capital and the employment of labor in the country. It was not until after 1979 that China implemented the strict one-child policy.

As the poster “Studying for the Mother Country” (1986) (Figure 7) shows, the girl is studying science, which was not a typical subject matter a girl would study in the 80s in China. The girl, however, could be glorified in the poster when she appeared independently, becoming known as an enthusiast of science or culture. In the poster titled “Productive Labor is the Most Glorious, Women can Also Become Heroes, Giving Birth to Boys or Girls is all the Same, Transform Social Conditions to Create New Customs” (same as the text written at the bottom of the poster in translation) (Figure 8), the artist portray the child being held by the mother and the child standing next to her as a female in an effort to reduce the perceived patriarchal nature of society. As a result, the presence of girls and the decline of boys demonstrates the Chinese government’s challenge to the popular belief that boys are superior to girls.

Studying for the Mother Country, Li Kong’an, 1986, Landsberger Collection.

Productive Labor is the Most Glorious, Women can Also Become Heroes, Giving Birth to Boys or Girls is all the Same, Transform Social Conditions to Create New Customs, Designer unknown, 1972, Landsberger Collection.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, Chinese posters emphasized the importance of having a girl within the one-child policy’s structure while displaying various female models in keeping with the changing environment of the country. Generally, the posters paid great attention to the productive roles that women could play, featuring women engaging in “male” pursuits in production as “iron women,” working in the service trade, and later engaging in activities related to the welfare of children and the elderly (Landsberger, 1998). In posters that feature both genders, the male’s relative superiority of status over the female is not expressed in any difference in size: men and women stand equally tall (Landsberger, 1998). Therefore, there appears to be an emerging “woman power” in China generally.

Nevertheless, although “space babies” posters usually contain a group of children, including both girls and boys, the number of girls is relatively low compared to boys, and they always become companions of the other boy travelers. In “Roaming Outer Space in an Airship” (1962) (Figure 9), there is only one girl among four boys, and the boy is the one responsible for operating the aircraft’s engine. The artist may not have considered who was allowed to fly the plane when he designed it, and it may have just become a matter of default or unconsciousness for that generation. Thus, on the one hand, the Chinese “space baby” posters encourage girls to develop independently. Yet, on the other hand, they cannot abandon the traditional ideology of patriarchal social order.

Roaming Outer Space in an Airship, Designer unknown, 1962, Landsberger Collection.

Chinese slang says that the work becomes lighter with boys and girls together. According to this quote, productivity can be enhanced through a cooperative mechanism between men and women. Human reproduction relies on this mechanism as well, which is the most basic mechanism in biological science, as Lee Edelman claims that a heterosexual relationship is a guarantee of future (re)production (2004). It is inconceivable that any culture will forget that it needs to reproduce itself (Postman, 1994). Therefore, when we discern imageries of both boys and girls in China’s “space babies” posters, a well-established political means of reproductive futurism through heterosexual unions have been developed and implemented.

6 Conclusions

How “space babies” is portrayed historically in China has implications for how the space project is viewed and perceived today as a political means, a specific sociocultural pursuit, and a reproductive tool for the future. The purpose of this study is to analyze visual depictions of children flying to outer space in posters during the late twentieth century in China, claiming that the Chinese promote reproductive futurism and place all future hope upon children through the political practice of “space babies” posters from the 1950s to the 1970s.

The imagery associated with this variety of children closely related to China’s cooperation and division with the Soviet Union during the Cold War. It is characterized by the collectivism and repetition of figurative images that the Chinese have revered since ancient times. Not only is the “space babies” poster an imaginary vision of outer space, but it also takes us back in time, combining the immortality and transcendence of traditional Chinese mythology. In addition, the poster depicts children flying into space to convey the complexity of gender issues in China subtly, which portrays the Chinese people’s desire to develop their “woman power” at a time when traditional patriarchal ideologies still dominated, and only in collaboration with heterosexuality was reproductive futurism possible.

In the late 1980s, posters gradually disappeared in local bookstores. The main explanation for it can be found in the fact that the popular ownership of electronic media increased as a result of modernity and higher standards of living. The state also switched to using television and film cameras for diffusion purposes in the late 80s and 90s (Landsberger, 1998). Interestingly, the theme of children venturing into outer space still existed in the form of photography following the posters. The updated spaceship props were made of painted cardboard, and the outer space universe became the background in the photo studio.

“Landing on the moon and landing on Mars is very significant progress in the development of human civilization,” said Zhou Jianping, the current chief designer of China’s crewed space program (Bradsher, 2022). The strength China nowadays represents and its ambition to achieve a demanding endeavor such as a crewed lunar landing never changed. However, the effectiveness of diffusion, in general, appears to be diminishing. During the modernization and globalization process, many people were liberated intellectually, leading to a belief that individuals were subjected to endless government hyperbole designed to paint an unrealistic, overly optimistic picture of reality. Meanwhile, the visual representation of “space babies” has changed dramatically from printed matter to the screen, from static images to moving images, and from national to international.

References

Aliberti, M. (2015). When China goes to the moon… (1st ed.). Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-19473-8_9Search in Google Scholar

Bartos, A., & Boym, S. (2001). Kosmos: A portrait of the Russian space age (1st ed.). Princeton Architectural Press.Search in Google Scholar

Birrell, A. (1999). Chinese mythology: An introduction. Johns Hopkins University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Bradsher, K. (2022). China launches astronauts to newly completed space station. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/29/world/asia/china-space-launch-astronauts.htmlSearch in Google Scholar

Chang, K. (2022). Artemis II, Artemis III and beyond. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/11/science/artemis-ii-astronauts-moon.htmlSearch in Google Scholar

Edelman, L. (2004). No future: Queer theory and the death drive (Series Q). Duke University Press.10.2307/j.ctv11hpkppSearch in Google Scholar

Garber, S. (2013). The decision to go to the moon: President John F. Kennedy’s May 25, 1961 speech before a joint session of congress. NASA. https://history.nasa.gov/moondec.htmlSearch in Google Scholar

Henriot, C., & Yeh, W. (Eds.). (2012). Visualising China, 1845–1965: Life/still images in historical narratives (pp. 379–406). Brill.10.1163/9789004233751Search in Google Scholar

Immerman, R. H., & Goedde, P. (Eds.). (2013). The Oxford handbook of the Cold War (1st ed.). Oxford Handbooks. Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199236961.013.0001Search in Google Scholar

Kohn, L. (1990). Eternal life in Taoist mysticism. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 110(4), 622–640. https://doi.org/10.2307/602892Search in Google Scholar

Landsberger, S. (1998). Chinese propaganda posters: From revolution to modernization. Pepin Press.Search in Google Scholar

McDougall, B. S., & Mao, Z. (1980). Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art”: A translation of the 1943 text with commentary. Michigan Papers in Chinese Studies, no. 39. Center for Chinese Studies; University of Michigan.10.3998/mpub.19066Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, D. (2015). Posters that won the war: The production, recruitment and war bond posters of WWII. Crestline.Search in Google Scholar

Peterson, G. (1992). The Chinese struggle for literacy: Villagers and the state in Guangdong, 1949–1976 [Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia]. University of British Columbia Library.Search in Google Scholar

Postman, N. (1994). The disappearance of childhood. Vintage Books.Search in Google Scholar

Shen, Z., & Xia, Y. (2012). Between aid and restriction: The Soviet Union’s changing policies on China’s nuclear weapons program, 1954–1960. Asian Perspective, 36(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1353/apr.2012.0003Search in Google Scholar

Wicks, A. B. (Ed.). (2002). Children in Chinese art. University of Hawai’i Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqr69Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Y. (2006). Overweight and obesity in China. BMJ, 333(7564), 362–363. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.333.7564.362Search in Google Scholar

Zhuangzi. (1969). The complete works of Chuang Tzu (B. Watson, Trans.). UNESCO Collection of Representative Works 80. Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Emergence of a Global Knowledge Network

- From Leibniz via Hegel to Jaspers: Paradigm Shift of German Thinkers’ Conception of China

- How did Laotse Transform Heidegger: The Generation of a New Philosophical Grammar

- The Reproductive Future: “Space Babies” in Chinese Posters 1950s–1980s

- Book Review

- Li Xuetao: S. Weber (Trans), Dialog des Missverständnisses—Die hermeneutische Relevanz der deutschen Sinologie für die chinesische Wissenschaft

- Introduction

- International Knowledge Hub: The Center for the Study of Chinese Characters in South Korea

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Emergence of a Global Knowledge Network

- From Leibniz via Hegel to Jaspers: Paradigm Shift of German Thinkers’ Conception of China

- How did Laotse Transform Heidegger: The Generation of a New Philosophical Grammar

- The Reproductive Future: “Space Babies” in Chinese Posters 1950s–1980s

- Book Review

- Li Xuetao: S. Weber (Trans), Dialog des Missverständnisses—Die hermeneutische Relevanz der deutschen Sinologie für die chinesische Wissenschaft

- Introduction

- International Knowledge Hub: The Center for the Study of Chinese Characters in South Korea