Abstract

This contribution on Léon de Rosny 羅尼 (1837–1914), the founder of modern Japanese Studies in France, deals with the trajectory of his formation and track record in Chinese and Japanese Studies. It highlights the role and significance his training in Chinese Studies under the guidance of Stanislas Julien played in his scholarly development and orientation, both as a sinologist and a japanologist. A self-taught student of the Japanese language, he pioneered the development of teaching material for Japanese language and literature, while also producing scholarly translations of classical literature, both Chinese and Japanese. We clearly discern a trajectory: the initial focus is on the study of Chinese, it subsequently shifts towards Japanese Studies from the 1850s on, to reach its apogee in the 1870s, while from the late 1870s on it appears to tilt towards Chinese Studies again. We conclude by an assessment of the merits and demerits of his scholarly production in these two areas of what was called “Oriental Studies” in the France of his time.

1 Introduction

This contribution assesses the scholarly formation of Léon de Rosny, the first incumbent of a chair of Japanese Studies in France. Although he is mainly known as a japanologist, this study also stresses his solid grounding in Classical Chinese under the guidance of Stanislas Julien. Unlike for Chinese, he had to rely on self-study for the acquisition of Japanese. While this made him a pioneer in the field, it also brought with it some manifest limitations to his scholarly achievements. For his study of Japanese, he relied primarily on Shogen jikō 書言字考, a Japanese-Chinese dictionary brought back from Japan to Leiden by von Siebold. Although it liberated him from the earlier missionary lexicography, he did not quite succeed in compiling a more modern dictionary himself. Likewise, in grammar, he was unable to completely outgrow the imprint left by João Rodriguez’s Arte da lingoa de Iapam. His limited proficiency in the vernacular was borne out during his exchanges with the members of the first Tokugawa mission in 1862. His anthology of Japanese poetry, although garnering a wide readership among the general public, was equally limited in scope and philological rigour.

Léon de Rosny 羅尼 (1837–1914) has been hailed as the founder of modern Japanese Studies in France. Although he was undeniably the first incumbent of a university chair of Japanese, he was much more than that. He was an “Orientalist,” an ethnologist, a historian of religions, a journalist, indeed his studies ranged over many fields. In 1863 he started teaching Japanese language and civilization at the École spéciale des langues orientales (東洋言語専門学校), and in 1868 he was formally appointed professor of Japanese at the said institution. The apex of his career was probably his organisation of the first international conference of Orientalists in Paris in 1873. In his wide-ranging approach he was an eminent representative of what was then commonly called in France Orientalism. Kick-started by Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian expedition, it included a group of disciplines covering all languages and civilizations between the Eastern Mediterranean and Japan, and even beyond, as far as Oceania.

Various aspects of the wide-ranging and multifaceted scholarship of Rosny have been studied in articles and monographs. A recent synthetic study that covers most aspects of his scholarship is the book entitled Léon de Rosny. De l’Orient à l’Amérique, which was edited by Fabre-Muller, Leboulleux, and Rothstein (2014). This contribution is devoted to his achievements in two of the disciplines Rosny is most commonly associated with, i.e. the fields of Japanese and Chinese Studies. The main emphasis, however, will be on his significance as a specialist of Japan, or, as it was called in his day, a “japonisant”. Although his biography has yet to be written, many data can be found in the various studies that have been devoted to one or other aspect of his scholarship, and the book mentioned above contains a handy and useful overview of the most important dates in his life. Biographical references will therefore be limited to the most essential data.

2 Stanislas Julien

In the history of the study of the Far East in France, Jean-Pierre Abel Rémusat (1788–1832) and Stanislas Julien (1799–1873) stand out as pioneers of modern Sinology. Unlike them, Rosny’s scholarship combined both Japanese and Chinese Studies, and indeed he published many books on the subject of Chinese classics, ranging from the Daode jing 道德經 to the Shanhai jing 山海經. Joseph Hoffmann (1805–1878), the first professor of Oriental Studies in the Netherlands, learned Chinese from a Chinese named Guo Chengzhang 郭成章, while at the same time receiving the cooperation of Tsuda Mamichi 津田真道 (1829–1903) and Nishi Amane 西周 (1829–1897) in compiling an introductory manual into the Japanese language based on the Japanese version of the Chinese classic Daxue 大學. Since Rosny learned Japanese by himself, there was inevitably a limit to his proficiency, and it is safe to assume that he was less proficient than Hoffmann in the spoken language. The pioneers of modern Japanese Studies in Europe at that time could be counted on the fingers of one most prominent ones were Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866) (Netherlands, Germany), Johann Joseph Hoffmann (1805–1878) (German naturalized in the Netherlands) and August Pfizmaier (1808–1887) (Austria).

Rosny’s meeting with and studying under the guidance of Stanislas Julien was of major significance in shaping Rosny’s scholarship both as a japanologist and a sinologist. Rosny started taking lessons in Classical Chinese from 1852 on. By general recognition Julien was a brilliant scholar, who put French sinology on an entirely novel footing. While it is unclear whether he had mastered spoken Chinese, given the fact that he never set foot on Chinese soil, there is no doubt that his mastery and understanding of the written language, in various registers and of various epochs, by far surpassed that of most of his contemporary colleagues in Europe.

Julien prided himself on having been the first westerner to have cracked the “code” of versified Chinese (Julien, 1842). None of his predecessors, including Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat had been able to properly translate Chinese poetry, and Julien had found out that even literate Chinese with a certain level of literary education were unable to properly analyse and understand Chinese poetry. He translated all verses in the Zhao-shi gu-er 趙氏孤兒, a Yuan dynasty play by Ji Junxiang 紀君祥, translated as Orphelin de la Chine, which the previous translator Prémare had been unable to do, made it possible for his student Bazin to translate four plays of the Yuan period as well as the comedy Pi-pa-ki 琵琶記 (Pipaji, Histoire du Luth), likewise a mixture of prose and verse (Walravens, 2014: 270) Julien taught two semesters of Tang poetry, thus enabling his student Marquis Léon d’Hervey-Saint-Denys to publish an anthology of Tang poetry (Walravens, 2014: 270).

Moreover, Julien was allegedly the first to overcome a major obstacle inherent in Chinese texts of Buddhist content. In these texts the Indian words were phonetically rendered in Chinese characters, but in the process their pronunciation had been altered to the point of being unrecognizable, baffling the early Western translators of Buddhist texts. Julien decided to translate a few travel accounts by Chinese pilgrims to India, especially those by the famous Xuanzang (Hiouen-thsang [玄奘, c. 602–664]) (Walravens, 2014: 272).

After several unsuccessful requests for help from Indologists, he realized early on that, in order to correctly “reconstruct” the Sanskrit names found in large numbers in the records he was studying, it was imperative that he master both Chinese and Sanskrit. Consequently, he devoted himself to the study of the latter language, not with a view to translating Indian manuscripts, but to be able to decipher the Sanskrit words that were written in Chinese characters and were thus only phonetically reproduced without their meaning. He also began to study two Buddhist dictionaries containing a significant number of Indian words in phonetic transcription, followed by a Chinese gloss. This allowed him, on the basis of his knowledge of Sanskrit, to find out the exact orthography of each Indian word. After dissecting all these Indian words whose single syllables yielded a letter of the Devanāgarī alphabet, he compiled a list of some 1,100 Chinese characters whose phonetic value was undeniable. This work of daily excerpting occupied him for 12 years. In 1853, he applied the method of transcription he had devised in Histoire de la vie de Hiouen-thsang et de ses voyages dans l’Inde, his translation of Huili’s 慧立and Yancong’s 彦悰 account of the famous Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang’s journey to India from 629 to 645. In the following years, Julien worked on his translation of Xuanzang’s own account of his pilgrimage to India, whose text is riddled with Indian words in phonetic spelling (Walravens, 2014: 273). In 1861 Julien published his system of reconstruction the Sanskrit words in Méthode pour déchiffrer et transcrire les noms sanscrits.

We may safely assume that by taking lessons with Julien, Rosny acquired much of the linguistic and philological skills Julien had developed for himself. His training gave him first and foremost self-confidence in Classical Chinese and its Japanese variant kanbun. In his later writings it is not hard to notice the ease with which he uses Classical Chinese, also with regard to Japanese literature. This stood him in good stead, given the relative weight of Classical Chinese in Japan’s literary and scholarly tradition.

A scholar of extreme rigour and meticulous care, Julien must have inculcated in Rosny a sense of close reading and in-depth philological analysis. Julien’s approach was novel and exceptional, since French sinology was still beholden to the speculative and intuitive approach inherited from the Jesuits. He was a no-nonsense, matter-of-fact student of Chinese, rigorously clinging to linguistic analysis and philological discipline, whereas many of his contemporaries were amateurs dabbling in things oriental or at best proto-sinologists. He explained his approach in several publications, including the Exercices pratiques d’analyse, de syntaxe et de lexicographie chinoise. Ouvrage où les sinologues trouveront la confirmation des principes fondamentaux, et où les personnes les plus étrangères aux études orientales puiseront des idées exactes sur les procédés et le mécanisme de la langue chinoise.

Julien was proud of having found what he called the mechanisms of the Chinese language and especially of versification, as well as the mechanisms of transliterating Indian words in Chinese characters. Abundantly conscious of his own scholarly prowess, he appears to have had an unreserved self-esteem, although admittedly, it was not unwarranted. In 1867 an anonymous essay that tells a lot about Julien’s personality was published in Paris. Titled “Langue et littérature chinoises” it was included in a publication entitled Progrès des études relatives à l’Egypte et à l’Orient. [1] Hartmut Walravens has identified the author of this essay as none other than Julien himself, which ironically makes it an anonymous autobiography. Although it is mainly devoted to showering praise on his own achievements, talking about himself in the third person to be sure, it nevertheless gives an interesting insight into his career and his scientific methods. Considering Julien nearly synonymous with French sinology, the anonymous author spares limited space on recognizing the merits of other scholars. Nevertheless, he deigns a number of his (former) pupils worthy of mentioning, and one of them is Rosny, the only japanologist in the list. Julien briefly describes him as someone with a solid knowledge of Chinese and Japanese, adding that Japanese is a learned and very difficult language (Walravens, 2014: 276). Below we shall have occasion to find out to what extent Rosny could be live up to his teacher’s esteem.

In the existing research literature on Rosny, we do not find much about the way Julien conducted his courses. It is probably safe to surmise that he continued in the line of Abel-Rémusat, having students take turns in preparing selected passages of original texts and having them present their findings, interpretations and translations to the assembled class. Be that as it may, we read that after some time, Julien gave Rosny the advice to try his hand at the study of Japanese, a language he himself had shied away from in spite of his voracious study of many other languages. It is not clear whether Julien gave Rosny this advice in a bid to shield a favourite pupil of his from a possible future challenge by the brilliant Rosny. Anyway, it was sound advice in as much as Japanese Studies was still a virgin field. The field was indeed so virgin that Rosny had no one to turn to who could become his teacher. He had to rely on self-study. In his own testimony, he started to study Japanese in 1852, presumably very soon after starting to take lessons with Julien. (de Rosny, 1887: XII)

France did indeed not have any japanologist. The last one of note, although it is questionable whether he knew Japanese was Pierre François-Xavier Charlevoix (1682–1761), author of Histoire de l’Établissement, des Progrès et de la Décadence du Christianisme dans l’Empire du Japon. Rosny had to turn to handbooks, grammatical manuals and dictionaries, but they were very rare. The grammars and dictionaries that had been compiled by the Christian missionaries dated back to the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, and were very hard to come by. These materials embodied a tradition of linguistic study that had been effectively interrupted. After the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire, it fell to the early orientalists of the Restoration period to reconnect with the old tradition, and transform it into a stepping stone towards the shaping of a modern scholarship on Japan and its language. The history of modern Far Eastern Studies in France started in 1816, when King Louis XVIII appointed Abel-Rémusat to the chair of Chinese and Manchu Studies at the Collège de France.[2] Rémusat constitutes the link between the missionary sinology and modern scientific sinology. He transformed Prémare’s Notitia Linguae Sinicae, a primer on mandarin (guanhua 官話) into the first systematic grammar of Chinese entitled Elémens de la grammaire chinoise (1822), and was to some extent connected with the transformation of the Japanese grammar of João Rodriguez into the first systematic grammar of Japanese by Landresse.[3] Both grammars, called élémen(t)s were still quite defective but nevertheless, they were the first step towards a more modern type of grammars.

Prémare’s work Notitia Linguae Sinicae was not a systematic grammar, but a textbook containing 12,000 examples of usage. Joseph de Prémare SJ (1666–1736), who stayed in China from 1698 until his death in 1736, insisted that one should learn a language by memorizing many examples, not theory or grammar. He was the first Western scholar to make a clear distinction between modern and Classical Chinese. He sent a manuscript of Notitia Linguae Sinicae to Étienne Fourmont (1683–1745) in France in 1728. It was shelved unpublished in the Royal Library, and remained sleeping there for many years, while in the meantime Fourmont compiled and published his own flawed and often misleading grammar book. Julius Klaproth was later to find out that Fourmont’s grammar book was nothing more than a reworking of Notitia Linguae Sinicae, shy of plagiarism. Rémusat discovered the sleeping Prémare manuscript, transcribed it, and used it as study material for learning Chinese. Rémusat’s copy was once again copied by his student Stanislas Julien, and sent to Malacca, where it was printed by the Anglo-Chinese College in 1831, blotting out its Roman Catholic origin. Rémusat compiled the first systematic Chinese grammar Elémens de la grammaire chinoise (published in 1822) on the basis of Prémare’s Notitia Linguae Sinicae.

If Abel-Rémusat was the founder of modern French sinology, he was also the midwife of modern Japanology. In 1820 he edited and published Titsingh’s translation of Nihon Ōdai Ichiran 日本王代一覧 under the title Mémoires et anecdotes sur la dynastie régnante des Djogoun, souverains du Japon. Although this was not a linguistic handbook, it may have elicited renewed interest in Japan. More importantly, he was involved in the edition and re-publication of Rodriguez’ grammar by de Landresse in 1825, and authored its preface. Ernest Clerc de Landresse (1800–1862) reworked and translated Rodriguez’grammars Arte Grande and Arte Breve into French under the title Elemens (sic) de la Grammaire Japonaise, par le P. Rodriguez, traduits du portugais sur le Manuscrit de la Bibliothèque du Roi, et soigneusement collationnes avec la Grammaire publiée par l’auteur à Nagasaki en 1604.

3 Self-Taught Japanese

Of the existence of the Portuguese and Latin dictionaries of Japanese, Rosny was aware, but he claimed to not have found them very useful. He allegedly did not reconnect with the Jesuit tradition, but turned north towards the Netherlands, where notably Philipp Franz von Siebold had imported some hitherto unknown materials, which were being transformed into usable tools by his assistants Hoffmann and Guo Chengzhang.[4] In the preface to his Introduction à l’étude de la langue japonaise (1856), Rosny declares that the grammar of João Rodriguez, published in French in 1825, failed to meet the great expectations of the orientalist scholars and was of little use. The Fonds Léon de Rosny in the Municipal Library of Lille includes a copy of this grammar. In the first hundred pages or so, we come across many pages where Rosny has noted down kanji and their katakana pronunciation in the margin, to represent transcribed Japanese words in the running text. In some places he has even added in the margin printer proof corrections of faulty transliterations of Japanese words in the text. Judging from the multitude of faulted transliterations (e.g. de Landresse, 1825: 103) in this French version of Rodriguez’s grammar, it is understandable that Rosny complains about its inadequacy, but Rosny too sometimes makes mistakes, as when he adds the characters 漢文 above Rodriguez’s word “kanwon” which corresponds to present-day kan-on 漢音 (de Landresse, 1825: 104).

Meanwhile, he did profit from the documents collected in Japan by Philipp Franz von Siebold and reproduced in the latter’s Bibliotheca japonica (Siebold & de et Hoffmann 1833–1838), featuring in lithography the text in Guo Chengzhang’s calligraphy. In particular, he found Siebold’s edition of the Japanese-Chinese thesaurus Shogen jikō (Syo-gen-ziko in Rosny’ transcription) very useful.[5] Rosny writes,

“It is, in fact, thanks to M. von Siebold’s lithographed works, and to some original works donated by him to the major public libraries in Europe, that Holland and Austria now are each home to an orientalist capable of dealing with Japanese texts, whose extreme difficulty had discouraged the well-known scholars of the first third of this century” (de Rosny, 1856: VII).

He carries on:

“Myself, having greatly lost my time learning the Japanese grammar mentioned above, I resolved to study Syo-gen-ziko (M. von Siebold’s edition), and restore in a simple and alphabetical order, on cards, the Japanese words which, in the aforementioned work, are arranged under 13 rubrics, in such a way that they cannot be found without a deplorable loss of time. I also noted the words that I found here and there in the works of travellers, and especially in the vocabularies published by the old missionaries in Japan; then, with the help of the Syo-gen-ziko, I was able to check their accuracy or to correct the errors. Finally, I undertook the study of the Japanese texts that I had at my disposal with the tools that I had devised and with the help provided me by the Chinese-Japanese collection of the Imperial Library in Paris. Thus, proceeding from the known to the unknown, I succeeded in reconstructing on a new basis and for my use a Japanese grammar, of which the following Introduction presents an abstract. The fine publications of my learned friend Mr. J. Hoffmann, of Leiden, and those of M. Aug. Pfizmaier, of Vienna, who have followed one another in recent years, have also contributed to improving this work relating to an idiom that is still barely known, and about which I wanted to facilitate my country’s understanding when the need would make itself felt” (de Rosny, 1856: VIII).

This is a somewhat disingenuous text, since he finds fault with Rodriguez’ grammar and then has recourse to a dictionary. The vocabularies printed in Nagasaki by the Society of Jesus and some Chinese and Japanese works preserved in the Imperial Library were no doubt useful, but neither the Shogen jikō nor the other works were grammars.

Incidentally, the title page of Introduction à l’étude de la langue japonaise (1856) is designed to emulate that of a Chinese book, a detail that no doubt reflects his sinological training. It flaunts his expertise in Chinese presenting his name in Chinese as 囉尼小儒輯著 (“compiled by the humble scholar Rosny”), translating its title as 日本語考 (“An inquiry into the Japanese language”), transcribing “Paris” in Chinese characters 巴理城 (Paris) and even transcribing in Chinese characters the name of the printer Imprimerie de Marius Nicolas 尼-科-蝲聚-珍房印and the name of the publishing bookshop Maisonneuve 墨-頌-訥-佛書肆發客 (sic).

After barely one year of study with Julien, Rosny already publishes his first booklet on Chinese and Japanese. This was to become a pattern. As soon as he had acquired a new skill or made some progress, he tended to wrap it up and rush it through the press, thus often exposing himself to easy criticism of immature or premature publishing. Indeed, as early as 1853, he published Évangile de saint Jean en japonais, Yoannesu no tayori yorokobi . Having been trained as an apprentice in bookbinding and typography, he showed a strong interest in the writing systems of languages. Hence also his particular attention to the kana syllabary and Chinese characters. In 1854 he published a Notice sur l’écriture chinoise et les principales phases de son histoire (de Rosny, 1854). We also see his fascination for the writing system in another work of his, equally published in 1854 under the title Calligraphie chinoise, a booklet that according to its full title offers models for practising calligraphy of Chinese characters (de Rosny 1854-b; Kornicki, 1994). His most important publication in 1856 was no doubt his Introduction à l’étude de la langue japonaise. Résumé des principales connaissances nécessaires pour l’étude de la langue japonaise.

3.1 Introduction à l’étude de la langue japonaise … (1856)

Although his Résumé des principales connaissances nécessaires pour l’étude de la langue japonaise (de Rosny 1854-c) has been described by Dubois, Kornicki and Le Nestour as “une première esquisse en français de la langue japonaise”[6], it was obviously a provisional work. It actually consisted only of eight autographed pages. Significantly, it bears no mention of place of publication and editor, and there is only one copy extant.[7] His first real handbook in the true sense of the term was published in 1856, under the title Introduction à l’étude de la langue japonaise. Résumé des principales connaissances nécessaires pour l’étude de la langue japonaise. It was received with critical acclaim, by some scholars in France and Germany, as is testified by the two following quotes:

À l’époque où parut cet ouvrage, la langue japonaise était complètement inconnue des orientalistes européens à la seule exception de J. Hoffmann, de Leide et de M. Aug. Pfizmaier, de Vienne. Pour la première fois dans ce travail, l’auteur cherchait à enseigner les éléments de l’idiome littéraire de l’Extrême-Orient, en s’appuyant sur la connaissance de l’écriture si compliquée usitée au Japon. Dans cette grammaire, l’auteur traite brièvement mais avec beaucoup de clarté, des formes grammaticales du japonais, et s’étend avec soin sur un système d’écriture qui, par sa nature syllabique, par l’emploi de formes cursives et l’étrange mélange de chinois qu’il admet, est une des plus compliquées qui existent, et forme à l’entrée de cette étude, un obstacle qui, au premier moment paraît insurmontable. M de Rosny nous fait connaître tous les systèmes d’écritures usités au Japon, les analyse et en montre l’application et la lecture par des planches extrêmement bien exécutées. C’est le premier et jusqu’ici le seul travail de ce genre qui ait paru, et il doit faciliter puissamment l’intelligence de la langue japonaise (Jules Mohl, in le Journal asiatique).

Joseph Hoffmann wrote, more as a friend than as a reviewer, it would seem: “C’est avec une satisfaction très vive que nous avons vu paraître l’Introduction à l’étude de la langue japonaise de M. Rosny. Après avoir examiné le livre, nous devons témoigner à l’auteur notre approbation sympathique pour ses travaux” (Fabre-Muller et al., 2014: 343).

However, there were also more critical voices, like that of Fr. Kaulen, a German orientalist. Kaulen starts his review of Rosny’s Introduction by referring to the traditionally well-known primers for the study of the languages of the Far East, i.e. the printed grammar of Rodriguez for Japanese, the one of Prémare for Chinese and the one of Gerbillon for Manchu. However, Kaulen notes, they were intended only for missionaries who can learn from and practice with native speakers, but they lack the scientific form that grammars of such difficult and distant languages require. Kaulen praises Rosny’s work because it brings light and clarity into the chaos of forms and notes found in Elémens de la grammaire Japonaise, Landresse’s revised edition of Rodriguez’ grammars of 1604 and 1620. However, he does not believe that Rosny has taken the treatment of the language any step further. It is only through the introduction of the book that we can make use of the rich content of Rodriguez’s long and almost useless book, he argues. Rosny lacks the deeper knowledge of linguistic principles, which are regarded as completely normal by German Orientalists, is the rather severe judgment of Kaulen (Kaulen, 1858: 351).

Kaulen does not understand why Rosny deals with “langue et littérature sinico-japonaise,” separately, while he feels that he should have included this topic in Chapter II, which is devoted to the use of Chinese characters in Japan. That is a debatable argument, to say the least. Kaulen also gives a brief overview of the morphology of Japanese, and points to the importance of what he calls the afformatives (Kaulen, 2014: 353). He deplores that Rosny has paid insufficient attention to this very important aspect of the Japanese language and goes on to state that further insight into the afformatives is the next major problem to be tackled in the linguistic study of Japanese. He also deals with the importance of Japanese kundoku techniques for a better understanding of Chinese Classical writings. He points out the frequent use of kanbunchō for Japanese writings, and notes that this is what Rodriguez called “koye” (Kaulen, 2014: 353).

The contents of this primer are as follows.

Origin of the Japanese language

Use of kanji in Japan

Japanese notation/syllable table

Japanese grammar (nouns, substantives, adjectives, verbs adverbs, postpositions, conjunctions, interjections)

Sino-Japanese Language and Literature

Japanese books

Exercises on how to read katakana and hiragana

The cursive script

He has a strong interest in the writing system and devotes a lot of space to explanations about it. This must not surprise, given that Rosny, trained as a bookbinder and typographer, had a life-long interest in writings systems.

More surprising is the fact that Rosny has added an index of Sanskrit words to his primer. This may seem unusual in an introductory course of the Japanese language. It must be noted however, that he compiled this primer while he was also studying Chinese with Julien, and that, as already noted, at this junction Julien was completing a glossary of Chinese transcriptions of Sanskrit words, many of which have found their way into Japanese through the Buddhist vocabulary of Chinese origin. Given that this primer was more geared to the Classical than to the colloquial language, he no doubt felt the index could serve a useful purpose.

3.2 Remarques sur quelques dictionnaires japonais et sur la nature des explications/observations qu’ils renferment (1858)[8]

In Rosny’s wording, this booklet presents some observations on the nature and the organisation of the dictionaries published by the Japanese, with the intention of facilitating their use for those interested in the Japanese language and literature. He notes that Japanese dictionaries, as far as he knows them, are bilingual, that is, Japanese and Chinese. They are divided into two categories: the first contains vocabularies of Japanese words, arranged according to their initial syllable; they are intended to teach the Japanese scholars, who often write in Chinese, the different ideographs that correspond to the Japanese words. The second category is that of the Chinese-Japanese lexicons, which include the explanation of the Chinese ideographs by their equivalents in Japanese. Rosny offers the reader a user’s manual for three bilingual Japanese-Chinese dictionaries i.e. Shogen jikō (transcribed by Rosny as Syo-gen-ziko, “A study of words and characters found in books”), 手引節用集大全 (transcribed by Rosny as Te-fiki-sets-yô-sïou-daïzen, “A handy general compendium”), and 文翰節用通寶藏 (transcribed by Rosny as Boun-kan sets-yô-tsoû-bô-zô, “A treasury for writing”); and two Chinese-Japanese dictionaries, i.e. 會玉篇大全 (transcribed by Rosny as Kwai Gyok-ben dai-zen, “A precious general repertory”) and 新増字林玉篇 (transcribed by Rosny as Sin-sô Zi-rin gyok-ben, “Precious tome of a collection of characters, newly augmented”).

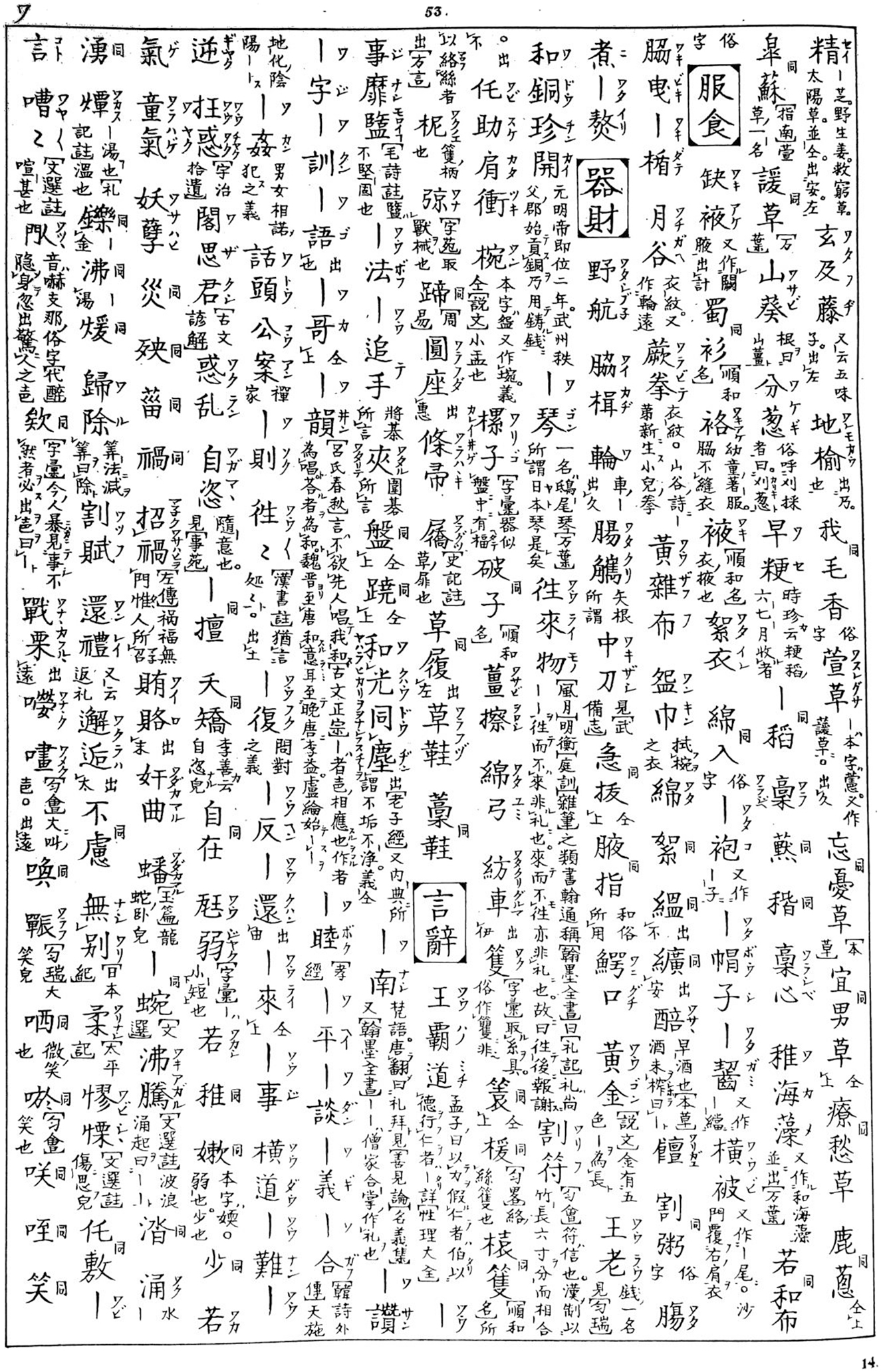

Most of the space in the booklet is devoted to the Shogen jikō, or in his sometimes not entirely uniform transcription Syo-gen-ziko or Cho gen-ji kô, because as already mentioned, it is a dictionary he found particularly useful. Indeed, he had been copying the entries of the dictionary onto cards, which he then could arrange in a simple alphabetical order (Ôhashi & Yanaura, 1994:132). His lengthy explanation of its organisation was no doubt meant as a kind of guideline equally usable with other dictionaries that have a similar organisation. The copy of Shogen jikō he is referring to, is not the original Japanese edition, but the lithographic edition by the “calligrapher Ko Tching-tchang, under the direction of M. Ph. Fr. Von Siebold (Leyde, 1835), in-fol” (de Rosny, 1858: 10, n. 2) (Figure 1)

Page from Siebold’s (Guo Chengzhang’s) lithograph version of the Shogen jikō (Bibliothèque municipale de Lille, Fonds Léon de Rosny, ROS 206).

. Incidentally, the Fonds Léon de Rosny in the Municipal Library of Lille does indeed include a copy of this publication, as well as of the Japanese original by Makinoshima Terutake (Figure 2).

Page from the original Japanese version of the Shogen jikō (Bibliothèque municipale de Lille, Fonds Lèon de Rosny, ROS 186).

The Shogen jikō, translated by Rosny as Examens des mots et des caractères (Examination of words and characters [which are found in books]), consists of 10 volumes in-8, compiled by Makinoshima Terutake 槙島照武. The preface of the dictionary is dated Yedo, the 11th year of Genroku (1698 AD). It is arranged in 45 main sections, corresponding to the letters of what Rosny calls the “irofa [iroha] or Japanese syllabary.” Below this level, the arrangement is no longer based on the alphabetical order, the words being attributed to one of 13 rubrics, called “mon” 門or “gates”. This is an arrangement typical for Japanese dictionaries of the format known as setsuyōshū 節用集, a type of encyclopaedic dictionaries that came in vogue in the Muromachi period, and combined two ordering principles: systematic rubrics and the iroha alphabet, but, as Rosny rightly points out, rather bewildering for the Western student of the Japanese language.

To illustrate the use of this particular arrangement, he takes two examples: the Japanese words sora 空 and mouma (i.e. uma 馬 horse). The first step in the process of looking these words up, is referring to the section of the dictionary that corresponds to the initial syllable of the word in question, in the case of the example, the syllables so and mou for the words sora and mouma. Below each of the primordial alphabetically arranged sections, we find 13 semantic subdivisions (gates), each relating to a particular group of words, e.g. words relating to heaven and earth, words relative to time, words relative to deities, to man, etc. Thus sora will have to be found in the “gate” of heaven and earth (Ken-kon mon 乾坤門), while mouma in that of animated beings (Ki-gyo mon 氣形門).

Rosny also goes through the trouble of enumerating the 13 semantic rubrics or “gates.” His rather erratic transcription at any rate reflects a propensity for go-on 呉音 readings rather than the kan-on readings of present-day parlance:

Ken-kon mon 乾坤門: the gate (which leads) to heaven and earth. It includes the words that designate the sky, next the names of the celestial bodies and everything related to heaven. Then come those which relate to the earth and earthly things: definitions of physical geography, geographical names, terms relating to agriculture, architecture, etc.

Si-ko mon 時候門: gate or section of time and its divisions, including everything related to the calendar.

Sin-gi mon 神祇門: section of celestial and terrestrial deities and spirits. It includes the words relating to “the worship of spirits,” called sin-tô by Rosny, and Buddhism, called but-tô by him.

Kwan-i mon 官位門: section of officials and ranks, all functions and titles of Japan and China.

Zin-li mon (sic) 人倫門: section of man and the various members of the family. It lists the names of the most illustrious princes, grandees, and men, priests and warriors, scholars and artisans, including a short biographical note. At the end follow the different names of the social classes, and, where appropriate, Japanese pronouns.

Si-tai mon 肢体門: section of the human body, including the anatomical terms and the names of the faculties of the mind, as well as the names of diseases.

Ki-gyo mon 氣形門: section of animate beings, in which is included the entire zoological system, more or less in the order adopted in the West.

Syô-syok mon 生植門: section of plants and trees. Woody plants are first listed, then follow all the names of the herbaceous plants with explanatory notes extracted, for the most part, from Li Chi-tchin’s Pèn-tsào. Here Rosny obviously means the Bencao gangmu 本草綱目 by Li Shizhen 李時珍, the famous book of herbology, whose first draft was completed in 1578.

Fan-syok mon (sic) 服食門: section on clothing and food.

Ki-sai mon 器財門: section on utensils and precious things, such as household utensils, instruments and weapons.

Gon-Zimon 言辞門: section of words. It contains compounds, phrases, proverbs and idiomatic expressions; furthermore verbs, adjectives, adverbs and particles.

Syou-ryo mon 数量門: section on numbers and measures.

Zyô-si mon 姓氏門: section on Japanese clan and family names.

Rosny comments on this lexicographical arrangement, which he finds awkward, and the cause of much loss of time. It is easy to guess, for example, that we must refer to the first section, that of heaven and earth, when we come across geographical names, to which quite often words such as yama 山 (mountain), kawa 川 (river), tera 寺 (temple), basi 橋 (-bashi: bridge), and others of the same kind are attached. The words kami, or sin 神 (deity), mikoto 尊 (august), yasiro 社 (temple), easily conjure up the section on celestial and terrestrial deities, while the presence of the generic names tori (bird), iwo 魚 or ouwo (fish), mousi 虫 (worm) etc. easily point one in the direction of the section on animate beings, just as ki 木 (tree), kousa 草 (plant), and fana 花 (flower), lead one to the section on plants. But not all sections are as straightforward, like e.g. the section designated by the vague name of “words”. Here we find all the Japanese verbs, which it is easy to recognize at first sight by their grammatical forms, i.e. their endings. Adjectives and adverbs are easily distinguished by their written and spoken form.

The syllabary used in the Shogen jikō is katakana, which consists of 47 different syllables. However, it should be noted that there are only 44 sections of initial syllables in the dictionary.[9] Several vowels are interchangeable without affecting the phonetic value or meaning of the words concerned. They are: “i”イ and “yi” or “wi” 井, “wo”ヲ and “o”オ, and “ye” ヱand “e” エ.

The words explained in the Shogen jikō are either purely Japanese or Sino-Japanese, i.e. Chinese of origin and adopted into the Japanese language in the course of time. In the case of a Sino-Japanese word, we often find added after the Chinese synonyms, a reference to the purely Japanese word that corresponds to the Sino-Japanese word. For example, in the case of the expression ten-tsi 天地 (heaven and earth) (Syogzk, p. 140, col. 13), after a series of Chinese synonyms, the reader is referred to the section of the syllable A by the expression 出安 (a ni deru, see under A). Indeed, in the corresponding “gate” under the syllable A, we find the two Chinese ideographs with their purely Japanese pronunciation Ame-tsoutsi.

Rosny also remarks that the manner of noting the works cited in the dictionary is identical with that of the Chinese, i.e. by enclosing the titles in a kind of cartridge formed by a simple net, or even by a simple line separating them from the rest of the explanations or passages mentioned. Here again he shows his familiarity with the Chinese literary tradition.

The different meanings of the Japanese words are usually indicated by synonyms or Chinese equivalents, using, as in the dictionaries of China, a particular set of particles, most often “nari” 也. But in addition to these interpretations, the author of the Syo gen-ziko also gives the different Chinese characters used to represent each Japanese word; and, from these same Chinese characters one can infer the various meanings of the Japanese word. To make this clear Rosny takes as an example the definition of the word fazime (hajime). In the Shogen jikō (p. 22, c ii) it is defined with the following kanji: “初、始、元、甫、肇「説文」始也、首、權與 (計に出る)、濫觴 (良に出る)、草創 (左に出る)、果、終、畢”.

In the paragraph on “translation and explanation” he explains this as follows: fazime means the figure one 一, that is, the principle 根源, as one is the principle 元of numbers 数字; origin 初; beginning 始; the first cause 元; the beginning 甫; beginning 肇, which according to Chouě−wen (Shuo-wen) 説文 means “beginning”; head 首; beginning 權與; principle, beginning 濫觴; draft 草創; truly 果; end 終; beginning 畢.

It would be wrong, however, to take these Chinese words as synonyms of each other; they are so many readings of the word fazime, but nothing more. If we are not careful, we would be inclined to take Chinese tchoung 終 “end” to be a synonym of chi 始 “beginning.” These two opposites may be understood in Japanese, as the English word end, for example, which means both the beginning and the end in this expression: the end of a string. This explanation demonstrates that Rosny had familiarized himself thoroughly with dictionaries.

The relative ease with which he handles the Chinese glosses in this Japanese dictionary has to be credited to his firm grounding in Chinese under the guidance of Julien. Again, no doubt also reflecting the influence of Stanislas Julien, is Rosny’s interest in the vocabulary of Indian (Sanskrit) origin. He is keen to note that the Shogen jikō contains a number of expressions of Indian origin, introduced in Japan along with Buddhism. He gives a few examples of words that are phonetic transliterations of Sanskrit words into Chinese character combinations, and as a result still reflect to a greater or lesser extent the original Indian pronunciation. Thus Bodhisattva becomes bosatsu 菩薩 in Japanese. As transliterations such kind of Japanese words still reflect to some extent the pronunciation of the original Sanskrit. On the other hand, there are cases like 如来, which is a Chinese translation of the original Indian word Tathāgata, and therefore in no way reflects the original pronunciation. He further notes that these Sanskrit notions were introduced in Japan together with Buddhism via China. When giving some examples of Sanskrit, Rosny even adds the Devanāgarī spelling, testifying to his strong interest in writing systems, but also perhaps to a pedantic trait in his character. Secondly he gives a few examples of words that are Chinese translations of the original Indian word. He warns that the second category are not Japanese renditions of the Sanskrit words, but Sino-Japanese, which is not surprising since the doctrines of the Buddha have passed from India through China, to arrive in Japan.

Natural history holds a rather important place in the Shogen jikō; it comprises two large “gates” under each syllable. In the first, that of animals, we find, first of all, mammals, at least those commonly known as beasts (quadrupeds, including monkeys, etc.), then birds, fish and cetaceans, amphibians, insects and worms. The second section, that of botany, is even richer than the previous one, but it is not arranged more logically. Starting with trees, it goes on to fruits, then fana 花flowers, kousa 草 herbaceous plants, etc. Most of these plant names are accompanied by small explanatory notes, in which their dimensions, the colour of their flowers, the shape of their foliage, and various useful other data are given in both descriptive and practical terms. This is how Chinese and Japanese sometimes indicate the uses to which these plants are adapted. Surprisingly, Rosny inserts here a trenchant remark. He regrets to find in these explanations frequent extracts from Chinese herbology sources, instead of Japanese sources, in spite of the fact that the Japanese possess many treatises on natural history, and especially on botany, that are eminently superior to the Chinese herbology sources. This critical attitude may have been inspired by the training he had had in botany. We know that from an early age he had a passion for botany, and that he spent his holidays with Adrien de Jussieu at the Jardin botanique of the Muséum d’Histoire naturelle (Fabre-Muller et al., 2014: 36). Nevertheless, it is quite remarkable to see him at this early age voice the deliberate judgment that the Japanese books on natural history had outdone their Chinese predecessors. This insight had been reached by some Japanese natural historians during the Edo period, and probably by some Western botanists such as Siebold as well, but it was only much later that this was generally recognized.[10]

Rosny points out that most of the technical names in the Shogen jikō are accompanied by several equivalent Chinese translations, which greatly facilitates the identification with the Latin counterparts used in Western science. He takes the trouble to remind the reader that the Chinese technical names, among the Japanese, play the same role as the Latin names in Europe. They constitute the scientific nomenclature, while the purely Japanese names are only considered “vulgar terms”, not unlike the vernacular names used in the various European countries.

The section on words Gon-Zimon is the most considerable one of all “gates” under each of the syllables of the irofa or Japanese syllabary. It includes not only most of the expressions which form the material of the language, but also idioms, proverbs and sayings. The verbs, which hold an important place in it, are given in the absolute form, i.e. in the infinitive; their radicals generally do not appear here, except in combination with other words to form compound phrases. Adjectives are ordinarily found in the shi ending. Finally, the section includes a series of particles in the strict sense, which correspond to the category of hiu-tze (xüzi) 虚字 “empty words” in Chinese grammar, except that Japanese pronouns are included in the section on man Zin-li mon, instead of being included in the series of particles in general. Here again, he refers to his sinological training, as a means to “proceed from the known to the unknown,” as he put it.

The Syou-ryo mon number section, put at the end of the Shogen jikō, deserves special attention, because it contains a vocabulary of numerical expressions, such as “TWO close relatives” (the father and the mother), the FOUR seasons, the FIVE elements, the SIX liberal arts, the SEVEN passions, the NINE skies, etc. all stereotype phrases based on traditional numerical categories, whose knowledge is indispensable for a good understanding of literature.

Finally and importantly, it must be noted that the arrangement in Siebold’s lithographic edition, described by Rosny, is different from that in the Japanese original by Makinoshita Terutake. In the latter work the “gates” constitute the primary arrangement, and within each gate the entries are listed according to the iroha syllabary. In the Leiden lithographic edition the arrangement is the other way round: first the iroha syllabary, and then within each syllable the various “gates” (See illustration).

4 The First Tokugawa Mission to Europe

The first Tokugawa mission to Europe left Japan on the 22nd January 1862 (Bunkyū 01/12/23)[11] and returned home on 29th January 1863 (Bunkyū 02/12/10)[12] and was led by Takenouchi Yasunori 竹內保德, Shimotsuke no kami 下野守. In the research dealing with Rosny much attention has gone into his contacts with the Bakufu mission that visited Paris in 1862. This is invariably described as an important event in his career, and most authors parrot one another in stating that he was the interpreter of the mission, although some at least qualify their statement by adding the word “volunteer” or “non official”. According to some studies (Fabre-Muller et al., 2014: 65), it is the minister of Foreign Affairs, who, at the behest of the emperor, charges him with the task of interpreting for the mission. Aware about his poor mastery of the spoken language, he at first declines the assignment, but in the end gives in “à titre gracieux.” In other texts he is described as the “officieux” interpreter. Even more surprising is that the minister, to thank him for his services, promises to send him on a mission, i.e. to accompany the Japanese emissaries to Russia. Strangely enough, in the end he does not accompany the Japanese to Russia, but departs after they have left, in the hope of catching up with them. He does not appear to have been informed of their schedule, for he travels to Berlin, only to find out there that they have already left for Saint-Petersburg, and decides to follow them to the Russian capital. All this suggests that he undertook the trip at his own initiative and expense.

I do not know whether there is any document that corroborates the claim that the French government had commissioned him to act as interpreter. It would seem that the main source for this information is Rosny himself. We find an account about his meeting with the Japanese visitors in an article “La première ambassade japonaise en Europe”, published in 1862, in the Revue orientale et américaine [13] of the Société d’ethnographie (founded by Rosny in 1859). Although ostensibly written by someone else, it is clear that the source is Rosny. I quote the original text:

“On voit par ce qui précède, que le gouvernement a dû se passer d’interprète dans cette audience, par la seule raison qu’il avait négligé de prendre des mesures en conséquence. Avertis le jour même de ce qu’on attendait d’eux, les orientalistes qui auraient pu accepter cette lourde tâche, (…) ont hésité à engager l’honneur de leur pays en se présentant, dans une circonstance solennelle, comme interprètes d’une langue qui n’avait pas encore été parlé (sic) en Occident. MM. Hoffmann et de Rosny furent toutefois invités officieusement à se tenir auprès de l’ambassade, et à différentes reprises ils ont vu avec plaisir que la voie dans laquelle ils avaient dirigé leurs études était solide, et que s’il leur manquait encore la pratique, qui ne peut s’acquérir complètement en deux ou trois semaines, ils avaient du moins la satisfaction de se faire comprendre et estimer de ceux-là même qui n’entendaient rien d’aucune langue européenne.”[14]

This passage has decidedly an undertone of both apology and self-praise.

In that same article, but on the preceding page (p. 14) the author relates: “Son Excellence Takeno-outsi-Simo-dzouké-no Kami a adressé à l’empereur le discours suivant, dont il a été donné lecture en français, et lui a remis les lettres écrites par le Taï-koun à sa Majesté …”[15] This is a rather enigmatic statement. The Japanese emissary will no doubt have read his message in Japanese. His speech will have been followed immediately by its French translation, either extemporized on the spot by someone on hand, or prepared beforehand, in which case anyone can have read the French text from a paper. Since in the following page he takes issue with the lack of preparation of the French government in regard of the interpretation, and the fact that he together with Hoffmann had been summoned on the day itself, it is not natural that he fails to mention the reading of the French translation of the Japanese emissary’s speech, as if he wants to gloss something over.

Beasley is the only author I have come across so far who explicitly denies the claim that Rosny was the non-official interpreter. He notes that the French missionary Girard was the official interpreter of the mission (Beasley, 1995: 89). Meant is Fr. Prudence Séraphin-Barthélemy Girard (1821–1867) of the Missions Étrangères de Paris, a missionary based in Japan. He was an interpreter of the French Consul-general Duchesne de Bellecourt in Edo. He seems to have been in France at the time of the mission’s visit. Girard may have been the man who read the French translation of the Japanese emissary’s speech.

What can the official assignment as interpreter have meant, if official assignment there was? Did it mean acting as the interpreter for the emperor at the official audience of the Japanese with the imperial couple at the Tuileries palace? The abovementioned passage seems to exclude that. Did it mean that he had to accompany the Japanese and interpret whenever there was need to? At any rate, the mission had its own interpreters, young yōgakusha, such as Fukuzawa Yukichi, who befriended Léon de Rosny (Taniguchi, 1992: 69) and Matsuki Kōan. Beasley remarks that Rosny had originally been trained in Chinese (Beasley, 1995: 89), but had subsequently studied Japanese on his own. No wonder then that his written Japanese was much better than his spoken one. He was definitely handicapped in spoken Japanese. It seems that for their conversation they used English mixed with Japanese, and when necessary resorted to hitsudan 筆談 (so-called brush conversation, i.e. carrying on a talk by writing on paper what one wants to say). Rosny asked Fukuzawa all kinds of questions about Japanese. Rosny not only travelled to Holland to meet them, but he also appeared in St Petersburg. Since French was widely spoken among Russia’s élite, his services may have stood the Japanese in good stead there, so Beasley surmises (Beasley, 1995: 89), but it is more likely that his main purpose was to learn from them, rather than to serve them as interpreter. It did give him the opportunity to test his knowledge with literate Japanese, such as Fukuzawa Yukichi, Kurimoto Joun, Fukuchi Gen’ichirō and others. Later Kurimoto Joun would reminisce about Rosny’s pronunciation as muddled (kikkutsu 詰屈), and as him not understanding the use of particles (joshi 助詞) ( Matsubara, 1986: 20).

Fukuzawa Yukichi maintained an ongoing correspondence with Léon De Rosny during his tour through Europe. When he was staying in The Hague, Rosny visited him there. The letters Fukuzawa addressed to Rosny in Japanese are written in a rather stilted bungotai and all kanji have rubi. This was evidently done in an effort to adapt the text to Rosny’s level of Japanese. In concluding he uses an English word (“Sorry”) and the address is written in Dutch (Miyanaga, 1989: 126). When the mission headed by Shibata Takenaka 柴田剛中 was staying in Paris in 1865, it often received the visit of Léon de Rosny. About his spoken Japanese, Fukuchi commented that he did not understand more than 30% (Beasley, 1995: 101). To all intents and purposes, Rosny would not have been able to adequately act as interpreter. Simultaneous interpretation did not exist in those days, but even consecutive interpretation would have been too tall an order. His knowledge of Japanese was inevitably bookish, moreover heavily slanted toward the written language. It is very hard to gauge the actual level of active spoken Japanese he would have mastered.

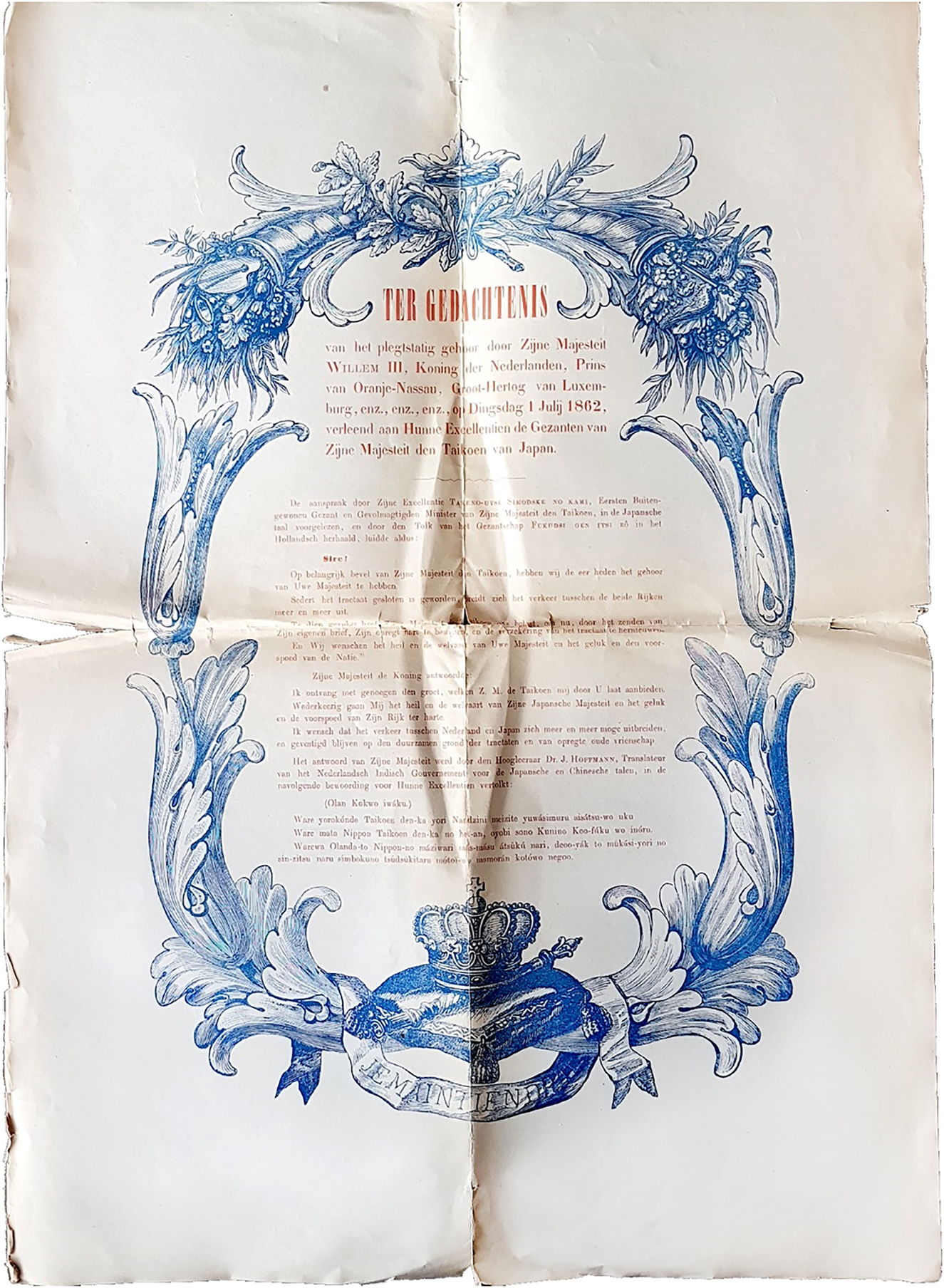

As already mentioned, when the first Tokugawa mission led by Takenouchi was staying in Paris, he invited Hoffmann from Leiden to join him. Was he hoping to get some assistance from his colleague? Hoffmann did act as commissioned interpreter for the Dutch king when the same mission visited the Netherlands. We have a testimony of his intervention during the official audience with the Dutch king. It is a printed one-leaf testimonial commemorating the audience, and preserved in Hoffmann’s inheritance (see Figure 3). That document quotes (in abbreviated form?) the speech by Takenouchi, translated from Japanese into Dutch by Fukuchi Gen’ichirō, and the reply by the Dutch king translated from Dutch into Japanese by Hoffmann. Hoffmann’s translation reads (converted in the Hepburn-style modern romaji): Oran koku ō iwaku: Ware yorokonde Taikun denka yoir Nanji ni meijite yuwashimuru aisatsu zo uku. Ware mata Nippon Taikun denka no heian oyobi sono Kuni no Kōfuku wo inoru. Ware wa Oranda to Nippon no majiwari masumasu atsuku nari, jōyaku to mukashi yori no shinjitsu naru shinboku no tsuzukitaru motoi wo mamoran koto wo negau.

Testimonial of the audience given by the Dutch King Willem III to the Japanese embassy led by Takenouchi Yasunori, explicitly mentioning Hoffmann's intervention as interpreter.

(Central Library of Leiden University, J.J. Hoffmann Collection, BPL 2186).

This text does not seem to have been edited by a native speaker of Japanese. Although admittedly Hoffmann may have polished it in view of reproducing it in the testimonial, it is no doubt a fairly accurate reflection of his actual level of Japanese, clearly bespeaking his kundoku 訓讀 training and background. Most probably he had a better active mastery of spoken Japanese than Rosny.

5 Si-ka-zen-yō 詩歌撰葉 Anthologie japonaise (1871)

Rosny had a strong interest in Japanese literature and poetry. He translated parts of the Manyōshū 万葉集 and the Kojiki 古事記, but his most widely read book was undoubtedly his Si-ka-zen-yō Anthologie japonaise. Poésies anciennes et modernes des insulaires du Nippon (de Rosny, 1871a). Published in 1871, the Anthologie came in for some criticism from the scholar William Aston (1841–1911), well-known for his acclaimed Japanese grammar (Aston, 1869), in The Phoenix of February 1872, but it was highly praised by Stanislas Julien (Fabre-Muller et al., 2014: 358). Although August Pfizmaier, author of a Japanese-German dictionary (Pfizmaier, 1851), had already published a partial translation of the Manyōshū in German in 1852, Anthologie de la poésie japonaise was the first translation-interpretation in French of a sizable selection of poems. Rosny was in particular charmed by the Hyakunin isshu 百人一首 and would use it abundantly in teaching the Japanese language to his students. According to Fabre-Muller the anthology includes 112 poems written for the most part between the seventh and sixteenth centuries. Among them are some 15 poems taken from the Manyōshū, more than 50 poems from the Hyakunin isshu, as well as eight kanshi 漢詩 (Japanese poems in Chinese). Personally I counted 12 poems from the Manyōshū, and 30 from the Hyakunin isshu.

In a scrapbook of Rosny that bears the title “Notes et Documents sur le Japon et la Littérature Japonaise” (Fonds Léon de Rosny in the Municipal Library of Lille, BML Ros 164, possibly dating from 1858), we find a list of the collections of poems from which the anthology Si-ka-zen-yō Anthologie japonaise was excerpted. Although the anthology itself does not include any haikai 俳諧 poem, the bibliographical list itself includes a host of haikai collections. In total the list contains no less than 160 titles, which is a number way beyond the number of 112 poems (in Fabre-Muller’s counting) that eventually were selected for the anthology. Philippe Rothstein mentions that the Anthologie includes “La Bibliographie poétique japonaise (pp. 181–195)” (Rothstein, 2014: 256), which is none other than the list in the scrapbook. However, while the scrapbook list also includes the kanji of the titles, in the anthology they have been left out, which makes the latter list effectively of little practical use. On p. 182 Rosny explains that he has drawn up this list on the basis of catalogues of major libraries, including the Musée japonais de Leyde, which had a published catalogue: the Catalogus librorum et manuscriptorum a Ph. Fr. de Siebold collectorum.

As an anthology Si-ka-zen-yō Anthologie japonaise is a hybrid compilation. Its preface by Eduouard Laboulaye starts with a quote from a French translation by Hervey-Saint-Denys, a pupil of Stanislas Julien’s, of a Chinese Tang era poem. This is followed by a long preface (“avertissement”), and then an introduction, dealing with among other things prosody. He selected some 12 poems from the Manyōshū (Section 1), and some 30 from the Hyakunin isshu (Section 2). In the commentary on the last poem taken from the Hyakunin isshu he indulges in erudite explanation, even going to the length of printing in devanāgarī the Sanskrit words some of the Japanese words he wants to explain are etymologically derived from. Unfortunately in the process he commits a number of errors, transcribing e.g. the Japanese name of the Buddha Yakushi 藥師 hypercorrectly as Hyaku-si (native speakers of French have difficulty pronouncing the “hy”), and stating that Fudōson 不動尊 is derived from the Sanskrit Akṣobhya, whereas it is derived from Acala(nātha) (p. 83). Both Sanskrit terms mean “unmovable”, so merging of the two terms does happen, but Akṣobhya is a Buddha, whereas Fudō is one of the five wisdom kings. As already pointed out, this interest in Sanskrit is no doubt a reflection of the influence of Julien’s lessons, and Rosny’s interest in Buddhism. In Section 3 entitled “zakka” 雑歌 (miscellaneous) he includes various types of poems, usually of a more recent date and of a less dignified inspiration. Interestingly, this section concludes with a tanka composition by Rosny himself, which he presents as “un premier essai de versification japonaise tenté par un Européen” (de Rosny, 1871: 117–118).

In Section 4 he includes some specimens from the Ha-uta keikobon 端唄稽古本 (he transcribes the name as Ha-uta keikohon), a collection of popular and erotic songs in the vernacular (yet still using some Classical verb and adjective endings). The section starts with a song put in the mouth of a courtesan, who laments the imminent departure of her lover/customer. She curses the palanquin bearers who will soon come to pick her customer up, leaving her alone to long for the next meeting. Rosny here adds a note in Latin about the bell on the mountain mentioned in the song, which, he points out, is a synecdoche for “the most famous pleasure district in Edo.” (de Rosny, 1871: 122). Another poem is equally set in the licensed quarter, and it alludes to a typical practice in such places, which Rosny again explains in Latin, adding in a footnote a Japanese explanation in transliteration. He alludes to the custom that the courtesan has to report to ‘the procurer’ in the morning, detailing what she has done during the night in order to claim her fee and a pack of sanitary paper.

The fifth section contains a selection of eight Chinese poems (kanshi). One of them is taken from Tōsō renju shikaku 唐宋連珠詩格; four are taken from Wakan sansai zue 和漢三才圖會; for the other three poems he simply refers to his own Si-ka‐zen-yō (see below).

The sixth chapter is intriguing. It includes two specimens of what he calls Sinico-Japanese songs (no doubt recited in kundoku style, and transcribed as such by Rosny in the Anthologie) that were popular in Edo’s pleasure quarter Shin Yoshiwara or in Nagasaki’s pleasure quarter. These two Sinico-Japanese songs are preceded by what he calls a “boutade”, a fairly long, facetious text in the vernacular, reproduced entirely in hiragana (with the exception of two characters), and followed by its transcription in romaji. Entitled “l’Étude des fleurs à Yoshiwara” (The study of flowers in Yoshiwara), it describes in a humorous, slapstick manner a Westerner’s visit to the pleasure quarter. Throughout the story of the “boutade”, the courtesan is described as “professeur” using the grammatical masculine gender, camouflaging the real purport of the text for too prudish souls. It is a choice of text that has little to do with poetry. The second sinico-Japanese song is a quatrain (zekku 絶句), allegedly attributed to a courtesan of Nagasaki, and according to Rosny known by heart by all Japanese. He even adds the musical scores of one of the airs to which this quatrain is usually sung. In that regard it may be a rare record of an air sung in the licensed quarters during the late Tokugawa period.

In the appendix of the Anthologie he informs the reader that he has done some research about the prosody of Japanese poetry, and that the most instructive resource in this respect has been the Wakan sansai zue.

He notes in the introduction of Si-ka-zen-yō Anthologie japonaise (de Rosny, 1871: XXX) that the Japanese version of the poems has been printed by lithography, most often as facsimiles of the original edition.

In the section zakka (miscellaneous), he does not hesitate to reproduce some poems by his friends or acquaintances, poems of a topical nature, or written for a social occasion, somewhat incongruous in an anthology that features many of the canonical poems of Japanese literary history. On p. 109 he reproduces a poem by Kurimoto Teijirō 栗本貞次郎 (1839–1881), at one time his assistant for colloquial Japanese, while on p. 110 he reproduces a poem by Matsuki Kōan 松木弘安 (Terashima Munenori 寺島宗則, 1832–1893), adding some topical information about his political career, data hardly relevant for understanding the poem quoted, and rather incongruous in the context of an anthology.

On p. 111 he falls completely into the anecdotal, when he relates how Matsuki one day had taken photography lessons, which inspired him to jot down in a notebook of his the following definition of photography: 写真術ハ造物者の画にして光輝ハ其筆なり. Strangely enough, Rosny transcribes this erroneously as “sinsya zitsu-va butsu-zo-sya no gwa ni site, kwô-ki-va sono fude nari,” inverting the order of the components that make up the words shashin and zôbutsu. Elsewhere he reproduces the two character compounds in the correct word order (de Rosny, 1863: 142). Why did he include these poems, which were hardly canonical? In a sense he may have had a didactic purpose in mind, for indeed, a student of Japanese in those days was more likely to encounter a poem composed by a visitor than a classical one. On the other hand, he may have been motivated by expediency as well. If the poem was presented by someone in person, he had the opportunity to ask and ascertain its intended meaning directly from the author.

Si-ka-zen-yō Anthologie japonaise does not seem to have been composed on the basis of some concept about literary or poetical canon, but appears rather as a random selection of poems he had come across in the process of his research, teaching, correspondence or meetings with Japanese. There is no apparent effort at presenting a balanced overview of genres, or periods, nor a narrative that binds the various sections or poems together. Moreover, as often with Rosny, errors betray a certain sloppiness or hastiness in the production process, a recurring characteristic throughout his career, due to the fact that he was spreading himself too thin.

The book we are dealing with here did not come out in a single uniform format. It was published in two versions. One version appeared under the main title Si-ka-zen-yō and the subtitle Feuilles choisies de poësies japonaises (歌 uta) et de poësies sinico-japonaises (詩 shi) “for use by the students of the École spéciale des langues orientales.” It simply includes the original text of the poems and the corresponding vocabularies. In it, all text, both the Japanese poems and the French text of the title page, the “avertissement” etc., are in handwritten style and lithographed by Charles Chauvin, Paris. This version is defined in the “avertissement” as part 20 of Rosny’s Cours pratique de japonais, more specifically the third part of the “enseignement supérieur.” This what I will call the “Japanese” version was subsequently given a new title page printed in movable type, by Maisonneuve, which defined it as the companion volume to the Anthologie japonaise: poésies anciennes et modernes. The latter is none other than the well-known Anthologie japonaise: Poésies anciennes et modernes des insulaires du Nippon, which for convenience’s sake we will call the “French” version. The students thus had at their disposal both the Japanese originals, the Japanese vocabularies, and the French translations. In its notes the “French” version (adding the mention “des insulaires du Nippon” in its title) systematically refers to the “Japanese” version, except when the poem in question is lacking in Si-ka-zen-yō.

In addition, adding one more format, a few bibliophile copies were made, richly illustrated with watercolours by Goseda Yoshimatsu 五姓田義松 (1855–1915). The Bibliothèque nationale de France owns two such copies, which were apparently donated by the Fondation Smith-Lesouëf (Réserve 10477 and Réserve 10384). Although both illustrated by Goseda, they are not identical copies. The watercolours often deal with similar themes but are executed differently, or placed in a different spot on the page. The copy bearing the number 10477 is a refined and finished specimen, whereas the one bearing the number 10384 appears to include galley proofs, and use paper of a lesser quality. These two bibliophile copies were custom-made at the order of Lesouëf in 1885 (Briot, 2018: 18–29). They include the original poems in the same calligraphic hands as the ones featured in the lithographic “Japanese” version, and are equally printed by lithographic technique on 72 sheets of coloured paper heightened with designs of flowers and other traditional decorative elements, reminiscent of the style found later in Samuel Bing’s le Japon artistique. These bibliophile copies thus constitute in actual fact a kind of merger of what I have dubbed the “Japanese” and the “French” version. The copy owned by the descendants of Rosny appears equally to include these calligraphies (71 by their own count), suggesting that it is one of a few bibliophile copies. Apart from one calligraphy by Rosny himself, the names of the other calligraphers are allegedly unknown (Fabre-Muller et al., 2014: 100). However, in the “avertissement” to the “Japanese” version, Rosny claims that they were reproduced in facsimile from the original editions. Elsewhere he reiterates the principle that an uta is generally reproduced in facsimile in the handwriting of the person who has composed it (de Rosny, 1903: 289). He makes that statement in connection with the reproduction of a tanka he has composed himself. Hence, one may assume that the facsimiles of older poems were made from Japanese published editions, whereas those of contemporaries Rosny had contact with, are in the hand of those friends or correspondents. Such is at least the case with a tanka written by Matsuki Kōan (Usu-zumi de kaku tamazusa to miru kana …), the well-known tanka written by Fukuzawa Yukichi (Uete miyo hana no sodatanu sato wa nashi …), and a poem about bidding farewell (Nazuminishi kai koso nakere …), dedicated to Rosny, and probably calligraphied by Fukuzawa Yukichi (de Rosny, 1871: appendix 47).

The anthology seems to have had a wide circulation, perhaps partly due to its attractive design and layout, which must have resonated with the taste for Japonisme, in vogue at the time of publication. We may note that it was in 1872 that the art critic Philippe Burty, one of the early enthusiasts and collectors of Japanese artefacts, coined the term “Japonisme” in an article in the periodical Renaissance littéraire et artistique. Rosny’s anthology came just in time to ride the crest of the Japonisme wave.

6 Rosny’s Reputation

As already pointed out, evaluations of Rosny’s scholarship are divided. Although he was no doubt a multi-talented scholar, he lacked thoroughness, spreading himself too thinly over too many areas. Oda Yorozu 織田萬 has recorded a story about Rosny in his Minzoku no Ben 民族の弁. Looking back on his stint of study in France, Oda writes: “The facilities of the Japanese language department at the School of Oriental Languages in Paris were truly timeless, unique and bizarre.” He lodges a severe criticism at Rosny’s proficiency in Japanese, or lack thereof, and his teaching style. Not only was Rosny’s proficiency in Japanese poor, but the teaching materials he had adopted, such as Jitsugokyō 實語教, were helplessly outdated. Conversation textbooks included outdated conversational examples such as 「侍ガ奉行ノ前ニ呼出サレマシタ」(Samurai ga Bugyō no mae ni yobidasaremasita) and 「ココカラ江戸マデ何里アリマス」(Koko kara Edo made nanri arimasu) (Oda, 1940: 135–136). This strongly suggests that the fragments of conversation he had collected here and there around the end of the Edo period, were recycled and reused until the last years of his teaching career. Rosny’s mastery of the modern spoken language was no doubt defective. Besides, his interests lay mainly in writing systems, varieties of writing style and fonts, excerpting representative texts from ancient times to the modern era, and using them as reading material in classes. Conversation practice he entrusted to a native speaker. That was essentially his teaching method.

As already mentioned, the organisation of the first international conference of Orientalists, which he hosted in Paris in 1873, and which spanned a wide range of geographical and academic fields, and in which even Naonobu Sameshima 鮫島尚信 chaired a session, was probably the crowning achievement of his life as a scholar. He was also the founder and initiator of an academic society initially named “Société des Etudes Japonaises, Chinoises, Tartares et Indo-chinoises,” and likewise established in 1873. Famous members of the association included Samuel Bing, Émile Burnouf (1801–1852),[16] Philippe Burty, Joseph Edkins, Émile Guimet, Imamura Warō 今村和郎, who was a Japanese language instructor at the School of Oriental Languages, Auguste Pfizmaier, Naonobu Sameshima, and others.

According to Oda, Rosny was originally a sinologist rather than a japonologist. He writes begrudgingly: “I do not know where he learned it, but he could read Chinese texts to some extent. Although that too was an indifferent affair, it was at least better than his (understanding of) Japanese texts,” (Oda, 1940: 135–136), but this is not a fair evaluation. Rosny was no doubt “pedantic,” as Oda writes, but Oda seems to ignore Rosny’s training in written Chinese under the guidance of Stanislas Julien, nor does he seem to have read the annotations in Chinese Rosny had attached to his French translation of the Nihonshoki 日本書紀. Surely, Rosny could not speak Chinese, but if the annotations in Chinese were really composed by him, we must recognize that his mastery of written Chinese was outstanding for his time. That being said, Oda may have been right in claiming that he was a sinologist rather than a japanologist. No matter how much he devoted himself to Japanese Studies, Rosny never abandoned his strong interest in Classical Chinese Studies, and after the death of Stanislas Julien in 1873, his interest in Chinese culture seems to have been reignited, having received the bequest of his teacher’s collection of Chinese-related books.

After 1873 we see indeed, other than a few papers on Japanese cultural history and religion, no publications reflecting the results of original research on Japanese, while at the same time the number of students taking Japanese at the School of Oriental Languages was dwindling. The fact that the conversation textbooks used in 1897 still included the wording and expressions of the late Tokugawa period seems to support the impression that he had lost interest. On the other hand, he published manuals of Chinese language, French translations of Chinese classics, such as Shanghai jing (Chan-Haï King, 1891) and Xiaojing 孝經 (Hiao-King, 1889), and other Chinese-related papers and academic books. Luc Chailleu (Chailleu, 1986: 16) has suggested that the bequest of the collection from his teacher may have been an indirect cause of Rosny’s waning interest in Japanese and increased interest in Chinese.

That said, in the 1880s, Rosny did translate the Kojiki (de Rosny, 1883) and part of the Nihonshoki (de Rosny, 1887) into French, adding learned annotations in Chinese and French. He somewhat pedantically notes that the purpose of adding the annotations in Chinese was to elicit comments and remarks from Japanese scholars in order that they may suggest corrections. Even more astonishing is the fact that he also added the original Japanese text transliterated into shinji 神字 and into devanāgarī. Shinji are the writing system that allegedly existed in Japan before the introduction of kanji, in the so-called age of the gods (kami-yo 神代). The addition of transliterations in shinji and devanāgarī does bespeak his penchant for pedantry, if not a certain lack of scientific critique. Even so, the French translation of Nihonshoki earned some praise. Matsunami Masanobu, who was a Japanese instructor under Rosny for a while, and called himself a French translator of Manyōshū, contributed a favourable book review in Revue de l’histoire des religions in 1885. Written by someone who was his employee, the review may be lacking in objectivity, but winning the prize of the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres in 1887 for his translation was an undeniable academic accolade for Rosny.

It is a fact that Rosny, who never visited Japan, was not well-versed in the spoken language, because he learned it through books and self-education. The focus of his interest was on the study of the literature. However, as far as Japanese written language, especially literary language, was concerned, his proficiency was high, judging by contemporary standards. His interest in Sinology was enduring and unwavering throughout his life. The addition of Chinese annotations to the French translations of Kojiki and Nihonshoki certainly confirms this claim, but the most straightforward proof is his application to the position of professor of Chinese at the Collège de France, which had become vacant in 1893. His application was turned down, and his dream to one day succeed his teacher, was shattered. This caused a great sense of frustration unhappiness in his waning years.

References

Aston, W. G. M. A. (1869). A short grammar of the Japanese Spoken Language. Nagasaki: F. Walsh. Second edition: Belfast, 1871; third edition: London, 1873; fourth edition: Crawford, 1888.Search in Google Scholar

Beasley, W. G. (1995). Japan encounters the barbarian: Japanese travellers in America and Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Briot, A. B. (2018–2019). « Les amitiés japonaises de Léon de Rosny à travers son anthologie de 1871 ». In Le (Vol. 139, pp. 18–29). Paris: Association franco-japonaise.Search in Google Scholar

Chailleu, L. (1986). Léon de Rosny (1837–1914) : première figure des études japonaises en France. Éléments de bio-bibliographie. Mémoire de maîtrise de sociologie, Université Paris VIII-Vincennes à Saint-Denis (unpublished MA dissertation).Search in Google Scholar

Évangile de saint Jean en japonais, Yoannesu no tayori yorokobi [fragment spécimen, contenant les chapitres I et II, suivi de la deuxième épître de saint Jean; publié par Léon de Rosny. Conservé à la Bibliothèque Impériale de Paris, spécimen suivi de l’alphabet kata-kana avec lequel le texte est imprimé]. Paris, [s.n.] 8°.Search in Google Scholar

Fabre-Muller, B., Leboulleux, P., & Rothstein, P. (2014). Léon de Rosny: De l’Orient à l’Amérique. Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses universitaires du Septentrion.Search in Google Scholar

Julien, S. (1842). Exercices pratiques d’analyse, de syntaxe et de lexicographie chinoise. Ouvrage où les sinologues trouveront la confirmation des principes fondamentaux, et où les personnes les plus étrangères aux études orientales puiseront des idées exactes sur les procédés et le mécanisme de la langue chinoise, par Stanislas Julien, membre de l’Institut et professeur au Collège royal de France. Paris: Benjamin Duprat. XXIV.Search in Google Scholar

Julien, S. (1867). « Langue et littérature chinoises ». In Progrès des études relatives à l’Egypte et à l’Orient. Publication faite sous les auspices du ministère de l’Instruction publique (Vol. XII, p. 213). Paris: Imprimerie impériale, pp. 177–189. (Recueil de rapports sur le progrès des lettres et des sciences en France. Sciences historiques et philologiques).Search in Google Scholar

Kaulen, F. (1858). Review of Introduction à l’étude de la langue Japonaise, par L. Léon de Rosny. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 12(2), 350–354.Search in Google Scholar

Kornicki, P. (1994). La bibliothèque japonaise de Léon de Rosny, français-japonais, avec une introduction et des commentaires de Joseph Dubois et Patrick Le Nestour. Lille: Bibliothèque municipale de Lille.Search in Google Scholar

de Landresse, E. C. (1825). Élémens (sic) de la Grammaire Japonaise, par le P. Rodriguez, traduits du portugais sur le Manuscrit de la Bibliothèque du Roi, et soigneusement collationnés avec la Grammaire publiée par l’auteur à Nagasaki en 1604. Paris: Société Asiatique.Search in Google Scholar

Matsubara, H. 松原秀一. “Reon de Ronî ryakuden「レオン・ド・ロニ略伝」” Kindai Nihon Kenkyū『近代日本研究』Keiō gijuku Fukuzawa kenkyū sentā 慶應義塾福沢研究センター、 1986.Search in Google Scholar