Abstract

Courts require royalty rate calculations based on rigorous economic foundations. The licensing literature provides limited guidance for royalty rate determination, leaving appraisal report readers wanting a more tangible and objective lens through which to judge the credibility of royalty rate analyses. This article develops the standard, core model for calculating market royalty rates for intangible asset licenses where royalty rates are determined ex ante in the actual market, or ex post in a hypothetical market under a Market Value Standard. The model forms a consistent basis for performing and evaluating licensing royalty appraisals. Not being distracted with the question of how to combine the input values when calculating a royalty rate, the court can focus on understanding and verifying an appraiser’s calculations of the input variable values.

References

Andriessen, D.2004. Making Sense of Intellectual Capital: Designing a Method for the Valuation of Intangibles. Burlington, MA: Elsevier.10.4324/9780080510712Suche in Google Scholar

Anson, W., and D.Suchy. 2005. Fundamentals of Intellectual Property Valuation: A Primer for Identifying and Determining Value. Chicago: The American Bar Association, Section of Intellectual Property Law.Suche in Google Scholar

Bensen, E. E., and D. M.White. 2008. “Using Apportionment to Rein in the Georgia-Pacific Factors.” The Columbia Science and Technology Law ReviewIX:1–40.10.2139/ssrn.982897Suche in Google Scholar

Beutel, P. A.2005. “Valuation of Nonpatent Intellectual Property: Common Themes and Notable Differences.” In Economic Approaches to Intellectual Property Policy, Litigation, and Management, edited by G. K.Leonard and L. J.Stiroh, chapter 6, 95–107. White Plains, NY: NERA Economic Consulting.Suche in Google Scholar

Brickley, J. A.2002. “Royalty Rates and Upfront Fees in Share Contracts: Evidence from Franchising.” Journal of Law, Economics and Organization18:511–35.10.1093/jleo/18.2.511Suche in Google Scholar

Choi, W. S., and D.Stein. 2011. “Economics Gains from Licensing as an Estimate of the Reasonable Royalty.” March 30, 2011 paper presented at the 27th Annual Intellectual Property Law Conference of the American Bar Association, Section of Intellectual Property Law.Suche in Google Scholar

Choi, W., and R.Weinstein. 2001. “An Analytical Solution to Reasonable Royalty Rate Calculations.” IDEA – The Journal of Law and Technology41:49–64.Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, J. A.2005. Intangible Assets: Valuation and Economic Benefit. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Contractor, F. J.2001. “Intangible Assets and Principles for Their Valuation.” In Valuation of Intangible Assets in Global Operations, edited by F. J.Contractor, 1–24. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Corbett, M., M.Rao, and D.Teeces. 2006. “A Primer on Trademarks and Trademark Valuation.” In Economic Damages in Intellectual Property: A Hands-on Guide to Litigation, edited by D.Slottje. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Dawson, P. C.2010. The Economics of Business Valuation Discounts and the Competitive Risk-Return Paradigm. Ridgefield, CT: Peter C. Dawson Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Epstein, R. J., and A. J.Marcus. 2003. “Economic Analysis of the Reasonable Royalty: Simplification and Extension of the Georgia-Pacific Factors.” Journal of the Patent and Trademark Office Society85:555–83.Suche in Google Scholar

Fosfuri, A., and E.Roca. 2004. “Optimal Licensing Strategy: Royalty or Fixed Fee?” International Journal of Business and Economics3:13–19.Suche in Google Scholar

Jarosz, J. C., and M. J.Chapman. 2006. “Application of Game Theory to Intellectual Property Royalty Negotiations.” In Licensing Best Practices: Strategic, Territorial, and Technology Issues, edited by R.Goldscheider and A. H.Gordon, 241–65. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, H. E.2001. “Establishing Royalty Rates in Licensing Agreements.” CMA Management75(1):16–19. (Society of Management Accountants of Canada).Suche in Google Scholar

Kamien, M. I., and Y.Tauman. 1986. “Fees Versus Royalties and the Private Value of a Patent.” Quarterly Journal of Economics101:471–93.10.2307/1885693Suche in Google Scholar

Kopits, G. F.1976. “Intra-Firm Royalties Crossing Frontiers and Transfer Pricing Behavior.” Economic Journal86:791–805.10.2307/2231453Suche in Google Scholar

Layne-Farrar, A., A., J.Padilla, and R.Schmalensee. 2007. “Pricing Patents for Licensing in Standard-Setting Organizations: Making Sense of Frand Commitments.” Antitrust Law Journal74:671–706.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, E. S.2009. “Historical Perspectives on Reasonable Royalty Patent Damages and Current Congressional Efforts for Reform.” UCLA Journal of Law and Technology13:1–58.Suche in Google Scholar

Lev, B.2001. Intangibles: Management, Measurement, and Reporting. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Meyer, C., and B.Ray. 2005. “A Critique of Noneconomic Methods of Reasonable Royalty Calculation.” In Economic Approaches to Intellectual Property Policy, Litigation, and Management, edited by G. K.Leonard and L. J.Stiroh, chapter 5, 83–93. White Plains, NY: NERA Economic Consulting.Suche in Google Scholar

Moizel, M.2006. “Administration and Auditing of License Agreements to Promote Control and Harmony.” In Licensing Best Practices: Strategic, Territorial, and Technology Issues, edited by R.Goldscheider and A. H.Gordon, 267–72. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Parr, R. L.2007. Royalty Rates for Licensing Intellectual Property. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Pavri, Z.1999. “Valuation of Intellectual Property Assets: The Foundation for Risk Management and Financing.” Paper presented at an INSIGHT conference titled “Negotiating License Agreements: Maximize the Value of Your Intellectual Property Assets,” Toronto, ON, April 29–30, 1999. Accessed March 21, 2011. http://www.sristi.org/material/11.1valuation%20%20of%20intellectual%20property%20assets.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Poltorak, A. I., and P. J.Lerner. 2004. Essentials of Licensing Intellectual Property. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Porter, S. D.2008. “Estimating Hypothetically Negotiated Royalty Rates after MedIMMUNE, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., et al.” Journal of Legal Economics14:43–52.Suche in Google Scholar

Rabe, J. G.2004. “Licensing of Intellectual Property Case Study.” In The Handbook of Business Valuation and Intellectual Property Analysis, edited by R. F.Reilly and R. P.Schweihs, 503–34. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies.Suche in Google Scholar

Razgaitis, R.1999. Early Stage Technologies: Valuation and Pricing. New York: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Razgaitis, R.2003. Valuation and Pricing of Technology-Based Intellectual Property. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Reilly, R. F.2008. “The Relief from Royalty Method of Intellectual Property Valuation.” Insights. Autumn 2008, 20–43. Accessed March 21, 2011. http://www.willamette.com/insights/autumn2008.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Rocket, K.1990. “The Quality of the Licensed Technology.” International Journal of Industrial Organization8:559–74.10.1016/0167-7187(90)90030-5Suche in Google Scholar

Seaman, C. B.2010. “Reconsidering the Georgia-Pacific Standard for Reasonable Royalty Patent Damages.” BYU Law Review2010:1661–728.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, G. V., R. D.Lorence, and P. H.Prentiss. 1996. “Why the Cost Sharing Regulations Are Unworkable.” Tax Management Transfer Pricing Report4:738–43.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, G. V., and R. L.Parr. 2005. Intellectual Property: Valuation, Exploitation, and Infringement Damages. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, G. V., and R. L.Parr. 2010. Intellectual Property: Valuation, Exploitation, and Infringement Damages 2010 Cumulative Supplement. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.Suche in Google Scholar

Subramanian, S.2007. “Different Rules for Different Owners: Does a Non-Competing Patentee Have a Right to Exclude? A Study of Post-eBay Cases.” Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Competition Policy and Norwich Law School Working Paper 07-18. Accessed March 21, 2011. http://econpapers.repec.org/paper/ccpwpaper/wp07-18.htm.10.2139/ssrn.1022057Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, X. H.1998. “Fee Versus Royalty Licensing in a Cournot Duopoly Model.” Economics Letters60:55–62.10.1016/S0165-1765(98)00092-5Suche in Google Scholar

- 1

Panduit Corp. v. Stahlin Bros. Fibre Works, Inc., 575F2d 1152, 197 USPQ 726 (6th Cir. 1978).

- 2

If the four Panduit test factors cannot be proven, “the patent holder is not able to get damages in the form of lost profits and is only entitled to damages in the form of a reasonable royalty” (Smith and Parr 2005, 623).

- 3

Georgia-Pacific Corp. v. United States Plywood Corp., 318 F. Supp. 1116 (S.D.N.Y. 1970), modified, 446 F.2d 295 (2d Cir. 1970), cert. denied, 404 U.S. 870 (1971).

- 4

“The Georgia-Pacific factors are fundamental to establishing a reasonable royalty rate… [and] these 15 factors are the traditional starting point for royalty rate-based damages” (Smith and Parr 2005, 654).

- 5

Lee (2009) continues by pointing out that U.S. “Senate committee reports accompanying the most recent [legislative] proposals for patent [law] reform specifically noted that ‘juries (and perhaps judges) … lack adequate legal guidance to assess the harm to the patent holder caused by patent infringement,’ and [that this] formed a major focal point of the problem the Committee sought to address” (p. 36).

- 6

Dawson (2010) provides a detailed discussion of the FMVS, including its competitive asset market assumptions and their implications.

- 7

By contrast, Smith and Parr (2005) view the ALS to be more-or-less equivalent to the FMVS: “An arm’s-length standard is defined in words almost identical to those we use to describe market value” (p. 118), and “Our fair market value definition … captures the essence of an arm’s-length transaction” (p. 122).

- 8

The present author assumes that a reasonable royalty is equivalent to a market royalty. Later, he will discuss the fact that a reasonable royalty rate need not necessarily equal a market royalty rate due to the legal construction of the Reasonable Royalty Doctrine (i.e. it is intended to fully compensate the patent owner for his loss, to make him “whole”).

- 9

The quotations within this quote are from Lucent, 580 F.3rd at 1324.

- 10

“As a general rule, cost does not equal value” (Smith and Parr 2005, 165). “The problem with the cost approach is that in many cases cost is not a good indication of value. Many of the most important factors that drive value are not reflected in this approach”, which include the expected economic benefits of the license and the anticipated risk of achieving those benefits (Andriessen 2004, 92).

- 11

“In some cases, the profits of the infringer are considered as an indicator of the profits that the patent holder would have earned had there been no infringement” (Smith and Parr 2005, 617).

- 12

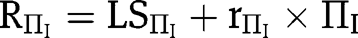

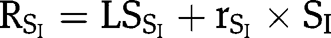

“r” is the royalty rate,

is licensee incremental profit (or benefit, or income, or earnings), and

is licensee incremental profit (or benefit, or income, or earnings), and  is licensee incremental sales revenue.

is licensee incremental sales revenue. - 13

TWM Mfg. Co. v. Dura Corp., 789 F.2d 895 (Fed. Cir. 1986).

- 14

Parr (2007) reiterates: “The analytical approach is a profit differential calculation, where the profits derived from use of the technology are subtracted from the profits that would be expected without access to the technology. The difference is attributed to the technology, and is considered by some as an indication of a royalty” (p. 125).

- 15

Smith and Parr (2005) suggest that the basic Analytical Approach is deficient in that it does not consider “the amount of complementary assets required for exploitation of the subject intellectual property” (p. 356 and p. 657), when the analysis does not include proper adjustments for complementary assets. “Business enterprises consist of monetary assets, tangible assets, intangible assets, and intellectual property. Economic benefits are generated from the integrated employment of these complementary assets” (Smith and Parr 2005, 197). They recommend the use of a “More Comprehensive Analytical Approach” in which financial statements would be adjusted to reflect “complementary assets, in the form of working capital and tangible assets, [that] typically are combined into a business enterprise along with intangible assets, all of which support intellectual property commercialization” (p.196). The profit margin calculations should also include an adjustment to the income statement for “all of the variable, fixed, selling, administrative, and overhead expenses that are required to exploit intellectual property. Omission of any of these expenses overstates the level of economic benefit that ultimately may be allocated to the intellectual property” (p. 197).

- 16

See also Smith and Parr (2005, 661–6) for a description of this type of DCF method.

- 17

“Lost-profit damages are based on an analysis of the additional amount of profits that the patent holder would have made but for the infringement. If the patent holder can show that absent the infringement, it would have made the sales made by the infringer, then it is entitled to the profits that it would have made on those additional sales” (Smith and Parr 2005, 618).

- 18

NPV is net present value.

- 19

FMV is fair market value.

- 20

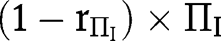

is the portion of the incremental profit retained by the licensee.

is the portion of the incremental profit retained by the licensee. - 21

“20% of all the deals discovered included running royalties and up-front license fees as part of the compensation terms to licensors. Up-front payments included: cash only, a combination of cash and stock, and stock only. The vast majority of up-front licensee fees (82%) were cash only” (Smith and Parr 2010, p. 110).

- 22

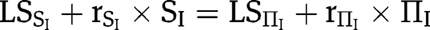

If one wishes to assume that the parties agree to a lump-sum (LS), up-front payment as part of the total royalty payment structure, then

and

and  . Since the present value of a lump-sum payment is the same whether incremental profit or sales revenue is the royalty base,

. Since the present value of a lump-sum payment is the same whether incremental profit or sales revenue is the royalty base,  , such that these lump-sum up-front payment variables drop out of the

, such that these lump-sum up-front payment variables drop out of the  equation. Therefore, the royalty rate eq. [D3] remains the same.

equation. Therefore, the royalty rate eq. [D3] remains the same. - 23

In the wake of Ebay Inc. v. MercExchange L.L.C., 126 S.Ct. 1837 (2006), there occurred a fundamental shift in the licensing environment that, in general, is believed to have reduced patentee/licensor bargaining strength, thus reducing

, ceteris paribus: “in eBay v. MercExchange (2006) the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the Federal Court order granting permanent injunction against eBay for willfully infringing patents of MercExchange. In doing so, the Supreme Court struck down the long standing rule that Courts will generally issue permanent injunctions against infringement of a patent…”, where “Denial of injunctive relief results in judicially-instituted compulsory licensing of patents which dramatically scales down the bargaining power of the patentee during licensing fee negotiations” (Subramanian 2007, 4 and Abstract; emphasis original).

, ceteris paribus: “in eBay v. MercExchange (2006) the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the Federal Court order granting permanent injunction against eBay for willfully infringing patents of MercExchange. In doing so, the Supreme Court struck down the long standing rule that Courts will generally issue permanent injunctions against infringement of a patent…”, where “Denial of injunctive relief results in judicially-instituted compulsory licensing of patents which dramatically scales down the bargaining power of the patentee during licensing fee negotiations” (Subramanian 2007, 4 and Abstract; emphasis original). - 24

Johnson (2001) provides an overview of royalty rate determination.

- 25

In rare cases, the expected incremental profit-to-incremental sales revenue ratio may not be expected to be stable during the license term. For an expected, and verifiable, fundamental shift in the incremental profit-to-incremental sales revenue ratio during the license term, the parties might agree to a license contract that includes an adjustable royalty rate schedule or formula (which would be triggered by a reliable indicator of a fundamental shift in the ratio).

- 26

“In the senior author’s experience of more than 30 years as a valuation consultant[,] it is extremely rare for unrelated parties dealing at arm’s length to negotiate a royalty rate that is not set at the outset of the license, either a fixed amount or rate, or at a rate determinable under a formula. At most, there might be a ‘window’ during which the parties could renegotiate compensation, but even this is unusual and annual adjustment simply never happens. In practice, then, a potential licensor or licensee must agree to a royalty rate for a newly developed (and often largely untested) item of intangible property and live with the bargain it strikes at the outset” (Smith, Lorence and Prentiss 1996, 739).

- 27

In situations where the licensee’s non-license scenario is characterized as the licensee having zero sales of the (similar) product, the licensee’s incremental sales revenue,

, would equal the with-license scenario sales revenue,

, would equal the with-license scenario sales revenue,  , and therefore,

, and therefore,  . When the parties expect

. When the parties expect  , eq. [D5] is equivalent to eq. [D3].

, eq. [D5] is equivalent to eq. [D3]. - 28

, and therefore

, and therefore  .

. - 29

Subscripts for the profit variables include 1 and 2 to distinguish between firm 1 and firm 2. Choi and Weinstein (2001) assume the licensee is a monopoly; here, the nature of the licensee’s competitive position is generalized, such that Choi and Weinstein’s (2001)

and

and  . The licensor’s/firm 1’s “disagreement payoff”, or disagreement profit, is

. The licensor’s/firm 1’s “disagreement payoff”, or disagreement profit, is  (p. 57). The licensee’s/firm 2’s “disagreement payoff” is

(p. 57). The licensee’s/firm 2’s “disagreement payoff” is  (p. 58), which “is the loss of return from not manufacturing [the product that uses] the invention” (p. 57) or the “profits lost to disagreement with the licensor” (p. 56).

(p. 58), which “is the loss of return from not manufacturing [the product that uses] the invention” (p. 57) or the “profits lost to disagreement with the licensor” (p. 56).

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin / Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Risk-Based New Venture Valuation Technique: Win-Win for Entrepreneur and Investor

- What Influences the Discount Applied to the Valuation for Controlling Interests in Private Companies? (An Analysis Based on the Acquisition Approach for Comparable Transactions of European Private and Public Target Companies)

- Guideline Public Company Valuation and Control Premiums: An Economic Analysis

- Valuing Installment Loan Receivables

- Firm Valuation with Bankruptcy Risk

- Royalty Rate Determination

- The Valuation of Tax Loss Carryforwards

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Risk-Based New Venture Valuation Technique: Win-Win for Entrepreneur and Investor

- What Influences the Discount Applied to the Valuation for Controlling Interests in Private Companies? (An Analysis Based on the Acquisition Approach for Comparable Transactions of European Private and Public Target Companies)

- Guideline Public Company Valuation and Control Premiums: An Economic Analysis

- Valuing Installment Loan Receivables

- Firm Valuation with Bankruptcy Risk

- Royalty Rate Determination

- The Valuation of Tax Loss Carryforwards