Abstract

Sensors for environmental perception are nowadays applied in numerous vehicles and are expected to be used in even higher quantities for future autonomous driving. This leads to an increasing amount of observation data that must be processed reliably and accurately very quickly. For this purpose, recursive approaches are particularly suitable in terms of their efficiency when powerful CPUs and GPUs are uneconomical, too large, or too heavy for certain applications. If explicit functional relationships between the available observations and the requested parameters are used to process and adjust the observation data, complementary approaches exist. The situation is different for implicit relationships, which could not be considered recursively for a long time but only in the context of batch adjustments. In this contribution, a recursive Gauss-Helmert model is presented that can handle explicit and implicit equations and thus allows high flexibility. This recursive estimator is based on a Kalman filter for implicit measurement equations, which has already been used for georeferencing kinematic multi-sensor systems (MSS) in urban environments. Furthermore, different methods for introducing additional information using constraints and the resulting added value are shown. Practical application of the methodology is given by an example for the calibration of a laser scanner for a MSS.

1 Introduction

The usage of high-resolution sensor technologies (such as laser scanners (LS) or cameras) has steadily increased over the last years as part of applications such as mobile mapping or autonomous driving [65]. This trend is particularly favoured by the availability of precise sensors with a steadily improved price/performance ratio. In particular, several automotive LS already exist, which are relatively cheap compared to their remarkable uncertainty level [27], [45], [60]. At the same time, the resolution, range and density of these three-dimensional (3D) sensors are also increasing. As a result, individual sensors, such as LS with a measurement rate of up to 500,000 scan points per second generate a multitude of observational information to be taken into account within a very short time. Furthermore, in so-called multi-sensor systems (MSS), several different sensor types are often used simultaneously [37], [49], which has a corresponding additional effect on the available data volumes [12], [40], [48]. For this reason, the terminology of ‘big data’ is applicable in this context. However, such a combination of multiple sensors results in further advantages that are helpful for an improved and more reliable environmental perception or localization.

Increasingly, the acquired sensor data is processed directly within the framework of adjustment or filtering approaches. The purpose of this can be the identification and segmentation of different objects in the environment, or also the contribution to the localisation task [64]. In the context of the huge amounts of data, efficient algorithms are becoming essential for applying appropriate methods. It also counts whether the data are timely independent or whether they are available in the context of several individual epochs. If all observations to be taken into account are available at once, a so-called batch approach is generally recommended [39], [66]. However, if all acquired data is used within one big adjustment, this batch processing quickly reaches its limits with such vast amounts of data. Even though such batch methods deliver reliable results, in general, they need to be performed on powerful computers in post-processing [3], [31]. This contradicts the requirements for online approaches (e. g., in the case of autonomous vehicles). Such applications require recursive approaches that process only a certain subset of the data when it is available. Therefore, for applications where the sensors or an entire MSS moves kinematically within a certain environment over time, a recursive approach is advisable in contrast to an overall adjustment [24], [61]. In addition, a recursive approach can also be useful when all data is available at the same time. This enables shorter computing times to be realised and larger amounts of data to be taken into account at all [26], [50]. Alternative techniques, such as data reduction by down-sampling [8], [57] or octrees [12], can thus be avoided.

In general, the theory of parameter estimation provides a comprehensive framework to solve overdetermined systems of equations for both batch processing [28], [32], [35], [39], [66] and recursive approaches [30], [39], [41], [66]. However, the applicability of these two categories depends on the mathematical relationship, called the functional model, between the observation vector

using both batch processing and recursive approaches. Here,

previously existed only for batch approaches. The first recursive estimation approach for efficient epoch-wise estimation was initially mentioned in [64] and has also been applied to the georeferencing of different kinematic MSSs in urban environments.

For this reason, the realisation for such a recursive GHM approach, using an iterated extended Kalman filter (IEKF), is presented in this paper in detail and analysed more thoroughly. The versatility of the new procedure should be emphasised, as this recursive GHM is also directly applicable for explicit equations, since every explicit relationship (cf. Equation (1)) can be transformed into an implicit relationship according to

As an additional novelty, different methods for the consideration of equality constraints and the related gain from this additional information are described.

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section, a standard batch processing method and an extension for consideration of equality constraints are presented. The recursive GHM is introduced in section 3 and also extended by different constraint methods. The methodology is applied to a system calibration task of an LS-based MSS using simulated and real data in section 4. Results and their discussion are presented in section 5. The paper ends with a conclusion in section 6.

2 Batch processing

2.1 Gauss-Helmert model

In general, the use of a suitable estimator is required to perform parameter estimation. In the context of batch processing, least-squares can be applied. For this estimator the optimisation criterion is to minimize the sum of the squared residuals

The residuals

where

Since the adjustment approach requires linear functional models, Taylor series expansion is performed to linearise

where

Using the utility matrix

the solution of the objective function

Here

The estimate of the requested parameter vector

The residuals

As this is an iterative process, the approximate values

2.2 Gauss-Helmert model with equality constraints

If reliable and suitable prior knowledge about the parameters is available, it is always advisable to integrate this additional information into the estimation process [4], [47], [51]. Any mathematical definitions, physical laws, geometric constraints or other practical or logical specifications can be taken into account. An extension of the GHM by equality constraints (referred to as constrained GHM (C-GHM)) is therefore introduced in [22], [36], [44], [46], [55] according to

where

which must be linearised by a first-order Taylor expansion to obtain Equation (18) according to

In order to find the minimum of the objective function

The cofactor matrix

with the regular auxiliary matrix

The estimated residuals

According to [22], the aforementioned substitution can be used to reduce the normal equation system by eliminating the Lagrange multiplier

which means that

Using this substitution the simplified normal equation system consists of the following

Even though the normal equation system has already been set up in Equation (28) and contains the solution for the requested parameters, the advantage of Equation (34) is that it is less dimensional, which can have a positive effect on the run time with regard to big data. Furthermore, the application to the data set presented in section 4 has indicated that in individual cases the solution via Equation (34) is numerically more stable and therefore more reliable depending on the geometric configuration. This relates directly to the number of constraints to be considered, which affects the condition of the normal equation matrix due to multiple zero elements. Again, several iterations for repeated linearisation are required to obtain the parameters requested by the inverse of the normal equation matrix

3 Recursive estimation

The batch processing methods presented in section 2 are suitable if all observations to be considered are available as a whole and have no temporal relationship. However, if new observations are available epoch by epoch, recursive estimation of the requested parameters should be used instead [30], [41]. Such an approach is particularly recommended when evaluating mass data. Otherwise it can happen that the normal equation systems in Equation (12), (28) and (34) become so large that numerical instabilities occur or no solution is possible without extensive computing power. For this reason, a recursive estimation can be worthwhile for the necessary computing time, even if the observations are not available epoch by epoch but as a whole without a temporal reference. In the following, an approach is presented that enables recursive estimation also for functional relationships with reference to a GHM. The basic idea for this recursive GHM is already presented in [64] and is a special case of an IEKF for implicit measurement equations, originally introduced in [5], [6]. In general, there are only very few contributions to such implicit filter approaches. While [53], [54] also use an IEKF for implicit relations, [14] consider linear implicit relations through a KF. The consideration of non-linear relationships, but without an iteratively improved linearisation, is done in [15], [52]. Except for [64], all these approaches mentioned do not consider state constraints at all. We first briefly introduce this filtering approach of the IEKF with an implicit measurement equation.

3.1 Recursive state-space filtering

In contrast to parameter estimation, recursive state-space filtering uses additional system information besides the measurement information. This makes it possible to consider suitable physical models that mathematically describe the temporal and spatial dynamics of the requested state parameters. Thus, both measurements and physical properties are considered. In general, an IEKF is an advancement of the linear Kalman filter (KF) and enables the possibility to consider non-linear relationships [7]. Both are applied by means of a recursive two-step procedure for state estimation over a theoretically unlimited amount of epochs. Arbitrary types of state parameters

During the update step, the predicted state parameters are corrected using the latest sensor observations

To distinguish between the predicted and updated state parameters,

Consideration of this implicit measurement equation during the update step is done by the objective function

where

where

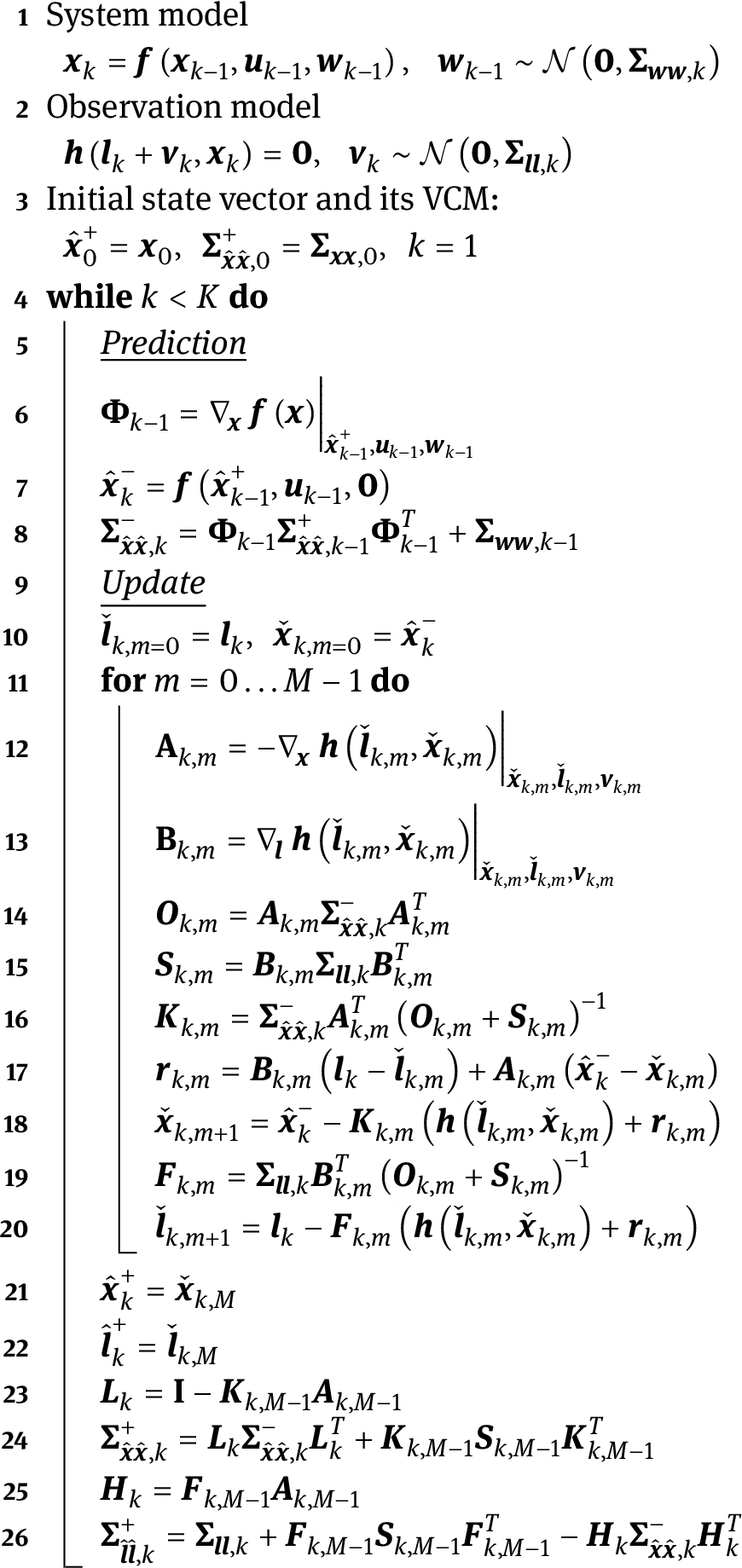

![Figure 1

Flowchart of the versatile recursive state-space filter based on an IEKF for non-linear implicit and explicit measurement equations with predicted states (solid box) and updated states & observations (dotted box) according to [64].](/document/doi/10.1515/jag-2021-0026/asset/graphic/j_jag-2021-0026_fig_001.jpg)

Flowchart of the versatile recursive state-space filter based on an IEKF for non-linear implicit and explicit measurement equations with predicted states (solid box) and updated states & observations (dotted box) according to [64].

The filtered observations and states can be obtained by the inverse of the normal equation matrix

In this context, it should also be mentioned that there are also corresponding uncertainty information in the form of the VCM

Versatile recursive state-space filter based on an IEKF for non-linear implicit and explicit measurement equations.

3.2 Recursive Gauss-Helmert model

The IEKF, described in Algorithm 1, is open towards different physical motion and measurement models. In contrast to the vast majority of existing IEKF realisations, both implicit and explicit relations can be applied (cf. Equation (3)). This is a crucial advantage and allows more flexibility regarding new applications. Furthermore, a recursive GHM can be introduced on the basis of this IEKF, which did not exist before. This new method was first introduced in [64] and enables the possibility to receive state estimates on an epoch-wise basis. As already motivated in section 1, such a recursive approach is particularly suitable for more efficient processing of big data. The main difference between the recursive parameter estimation and the recursive state estimation is the consideration of a dynamic model within the prediction step (cf. Equation (35)), if a filter approach is used.

Therefore, to realise such a recursive GHM, the prediction step and related system model of the IEKF are disregarded. In this case, the predicted state

3.3 Recursive Gauss-Helmert model with equality constraints

Consideration of suitable state constraints for arbitrary linear and non-linear KF approaches with explicit measurement equation are well-practised [18], [50], [51]. However, the combination of Kalman filtering with implicit measurement equations and state constraints is almost non-existing. A first approach is given by [62], where non-linear equality constraints are considered by means of a projection method. An extension regarding non-linear inequality state constraints using probability density function (PDF) truncation is given in [63]. However, both projection and PDF truncation in terms of implicit relations will lead to unfulfilled contradictions. This issue is stated in [63] and occurs due to the subsequent constraint step between the update and prediction step. Only the states are affected during the constraint step for the projection or PDF truncation method, while observations remain unaffected. For this reason, we present two methods for consideration of equality constraints, which overcome this issue and were initially introduced in [64]. As these state constraints can be applied by the IEKF for implicit measurement equation, introduced at the beginning of section 3, they are also applicable for the recursive GHM (cf. section 3.2). This will be referred to as recursive C-GHM with reference to the respective constraint method.

3.3.1 Constraint objective function (COF)

As also applied for the GHM with equality constraints in the batch processing (cf. section 2.2) the objective function of the recursive GHM (cf. Equation (39)) can be extended by an equality constraint according to Equation (18), following

Here,

By considering the constraints, the dimension of the normal equation system has increased accordingly compared to Equation (42). The basic calculation procedure of the IEKF, as well as the calculation of

3.3.2 Perfect measurements (PM)

In terms of explicit measurement equations, consideration of equality constraints by means of so-called perfect measurements (PM) is commonly used. Each single equality constraints is treated as an additional PM with zero measurement noise [42], [50], [51]. This idea can also be adapted for implicit relations. The available number of measurement equations is extended by artificial equations for the consideration pseudo-observations

where the measurement noise

with

This extension leads to additional rows in the extended design matrix

4 Efficient calibration of laser scanner-based multi-sensor systems

Multi-sensor systems (MSS) are characterised by the fact that they consist of several individual sensors, which support each other optimally and ensure redundancy to fulfil the respective task. The realisation of such an MSS requires the assurance of precise synchronisation and knowledge of the spatial relationships between the individual sensors. In general, this process is referred to as calibration and connects the respective local sensor own coordinate systems (SOCS) with a fixed superordinate platform coordinate system (PCS). Mathematically this is described by a 3D Helmert transformation with 6 degrees of freedom (DoF) for each sensor. A high precision and accuracy of these parameters are crucial since all subsequent calculation and processing tasks are based on the correctness of these values [11], [20], [23], [58]. For example, an angular deviation of about 0.1 ° already leads to a deviation of 1.7 cm on the object at a distance of 10 m.

In general, it is recommended to determine the corresponding calibration parameters in advance in a laboratory under controllable conditions and with a high-precision reference sensor. Furthermore, it is also possible to determine the necessary DoF on-the-fly during the actual measurement process. However, this requires higher demands on the necessary computing times since real-time applications (such as autonomous driving) are becoming increasingly important. Especially when using 3D LS, this can become a challenge due to the continuously increasing amount of measurement data. For this reason, recursive approaches are indispensable in this context.

Nevertheless, even if there are no real-time requirements and a calibration can be performed in advance, recursive approaches can be helpful as well. Depending on the available observations, the normal equation systems of common batch adjustments can quickly reach high dimensions, which leads to long computation times or higher demands on the computation power. More often, available observations have to be omitted through homogeneous or random subsampling, such that a calculation with the available computing capacities can be performed at all [2], [43]. Therefore, a transfer to recursive approaches is advisable, which allows to consider significantly more information. However, it is important to keep in mind that even if the integration of more observational data can positively impact the redundancy and uncertainty of the estimation results, this is not automatically advantageous or even always necessary. More observations do not necessarily contribute additional information content. For example, additional point observations of a plane do not provide directly any significant added value if a multitude of observations homogeneously covered the plane. Furthermore, recursive estimation can be beneficial when a suitable data reduction is not straightforward or does not exist.

In the following, we present a state of the art approach for the calibration of an LS-based MSS using geometric object space information. The recursive estimation (recursive C-GHM) is compared and discussed based on simulated data and real data with the results from the classical batch solution (C-GHM).

4.1 Experimental setup

For the sake of clarity, only a simplified representation of an MSS is given below. Nevertheless, the basic procedure can be transferred directly to any MSS with an LS to be calibrated. In particular, the SOCS of a Velodyne Puck VLP-16 is to be calibrated with respect to a specific PCS. The platform for mounting the LS has drilling holes that define the PCS (cf. Figure 2(a)). By using these drilling holes, the joint adaptation can be applied universally on any other platform. The spatial relationship to the SOCS of the LS can then be established via the drilling holes and the calibration parameters. The platform with the LS is shown in Figure 2 together with both PCS and SOCS. The 6-DoF calibration parameters between these two coordinate systems are thus to be determined. The used LS measures with 16 individual scan lines, which are almost perpendicular to its vertical axis and have an angular resolution of around

![Figure 2

LS-based MSS with Velodyne Puck VLP-16 LS on a platform with numbered drilling holes (a) and schematic representation of the MSS with the red PCS and the blue SOCS of the LS (b), according to [64].](/document/doi/10.1515/jag-2021-0026/asset/graphic/j_jag-2021-0026_fig_003.jpg)

LS-based MSS with Velodyne Puck VLP-16 LS on a platform with numbered drilling holes (a) and schematic representation of the MSS with the red PCS and the blue SOCS of the LS (b), according to [64].

To determine the calibration parameters between the SOCS of the LS and the PCS, multiple reference planes are arranged in the field of view of the LS within the 3D-Laboratory of the Geodetic Institute of the Leibniz University Hannover. There are 12 planes in the field of view of the LS, which differ in their distance to the MSS and their respective size. A detailed description of the reference planes used regarding their spatial distribution and orientation is given in [21]. Attention must be paid to a versatile alignment of the individual planes in order to ensure high sensitivity and quality for the individual coordinate axes [21], [23]. In this context, it should be noted that only a few (but at least two) of all 16 scan lines per reference plane will capture them at all. This results from the distance and size of the reference planes. In order to obtain known nominal values for the reference planes, they must be determined and mathematically described with a sensor of superordinate accuracy. This can be done with a terrestrial LS or a total station, for example. For the investigations shown here, a highly-accurate Leica Absolute Tracker AT960 was used which, according to [25], has an maximum permissible error (MPE) of

![Figure 3

Visualisation of the LS-based MSS (centre) during its calibration. The reference planes (left) are captured by individual scan lines (red dots) and measured (green dots) by the laser tracker (right). In addition, the drilling holes on the platform (yellow stars) are measured with the laser tracker (right). Due to the perspective, the PCS can only be displayed to a limited extent. Further arranged planes are located outside the shown part of the image. Modified according to [64].](/document/doi/10.1515/jag-2021-0026/asset/graphic/j_jag-2021-0026_fig_004.jpg)

Visualisation of the LS-based MSS (centre) during its calibration. The reference planes (left) are captured by individual scan lines (red dots) and measured (green dots) by the laser tracker (right). In addition, the drilling holes on the platform (yellow stars) are measured with the laser tracker (right). Due to the perspective, the PCS can only be displayed to a limited extent. Further arranged planes are located outside the shown part of the image. Modified according to [64].

A rotation speed of

4.2 State-of-the-art calibration approach

As a state-of-the-art approach, the calibration procedure for LS-based MSS using reference geometries (RFG) from [56] is used, which is inspired by the work of [44] and [17]. This methodical approach states that the distances between the observed reference planes and the measured 3D point observations of the LS to be calibrated should be minimal. To describe this condition in a functional model, two similarity transformations are needed to transform the SOCS via the PCS to the WCS. Therefore all

where

where

and

In order to estimate these parameters, the approach of [56] solves the calibration task by constraining the distances

The first three elements describe the 3×1 unit normal vector

where

where

In [19], [56], the application of this method is based on the assumption that the transformation parameters between WCS and PCS and the plane parameters themselves are error-free quantities (deterministic) that are known and constant. This is justified by using a reference sensor with superordinate accuracy in relation to the uncertainty level of the LS. However, in the context of this paper, these parameters shall be considered as stochastic quantities. This is reasonable since using a 3D Velodyne VLP-16 with multiple scan lines allows estimation of the individual reference planes. In [19], [56], this was not possible due to the respective use of a 2D profile LS. To enable a more general approach, the parameter vector here results as follows

Since the plane parameters

For the consideration of this additional information in the batch approach, the C-GHM from section 2.2 has to be applied.

The concatenated transformations with the inclusion of rotations bring challenges for adjustment. As already mentioned in section 2.1, suitable approximate values are required for the solution of the C-GHM to converge. These can be based on rough dimensions and can be updated after a successful adjustment, if necessary.

As a further extension to [19], [56], it can be reasonable for the quality of the calibration parameters to perform the acquisition process of the static reference geometries by the MSS from multiple different positions. In [13], it was shown that this allowed the individual transformation parameters to be decorrelated. As long as the planes are constant over time between the individual measurements, a better distribution of the measuring points on the planes could be realised. The use of multiple viewpoints may also allow certain planes that do not have geometrically sufficient coverage from a single viewpoint to be considered at all. For the adjustment approach this means that one set of 6-DoF transformation parameters between PCS and WCS (cf. Equation (61)) must be considered per calibration position s as follows

and accordingly, further measurement equations must be included. The plane parameters

4.3 Novel recursive and constrained calibration approach

In order to obtain the 6-DoF calibration parameters given in Equations (60) and (61), a recursive estimation can be performed in addition to the batch approach from section 4.2, thus achieving a higher efficiency. However, this requires a transition to discrete epochs. For this purpose, the available LS observations of all reference planes are subdivided into

where

The basic workflow for the PCL processing is shown schematically in Figure 4. In this context, the allocation of the entire PCL (for each position s) with regard to the individual reference planes as well as the individual epochs is described.

Basic workflow of the PCL processing. The original PCLs are assigned to the individual reference planes, which provides the basis for the batch approach. For the recursive approach, the observations are additionally subdivided into individual epochs k.

Compared with the parameter vector in Equation (69), the estimation of the state vector

Furthermore, the non-linear constraint regarding the plane parameters according to equation (67) has to be considered, which is also done epoch by epoch

The techniques (namely COF and PM) described in section 3.3 are applied to account for these constraints within the recursive C-GHM. A comparison of the results among each other and in relation to the batch C-GHM follows in section 5.

The results include a comparison to another special method for considering the constraints, which was initially shown in [13]. This approach is based on a modified functional model and is not directly transferable to other application examples. Here, the idea is to supplement the functional relationship according to equation (62) by a normalisation (norm) of the plane parameters

However, in general, the techniques from section 3.3 offer greater flexibility towards other applications.

Just like the C-GHM in batch processing, the recursive C-GHM also requires sufficiently accurate approximate values for the state vector

As already mentioned in section 3.2, the process noise

4.4 Simulated calibration environment

Since the state-of-the-art calibration procedure using the batch approach from section 4.2 cannot necessarily be regarded as the superior reference, another reliable validation option for the new calibration approach based on the recursive C-GHM with equality constraints (cf. section 4.3) is required. This enables an independent comparison between the two approaches. For this reason, the experimental setup from section 4.1 is additionally realised as a virtual simulation. The arrangement of the reference planes is reproduced faithfully with respect to their respective size, position, and orientation in relation to each other and the SOCS of the LS. All this information can be derived from the original measurements and generated based on the manufacturer’s specifications of the Velodyne VLP-16. A significant weak point of the simulation is the implementation of the realistic stochastic model of the LS. This model is unknown and can be very complex. As already mentioned, the manufacturer only refers to a range accuracy of typically up to

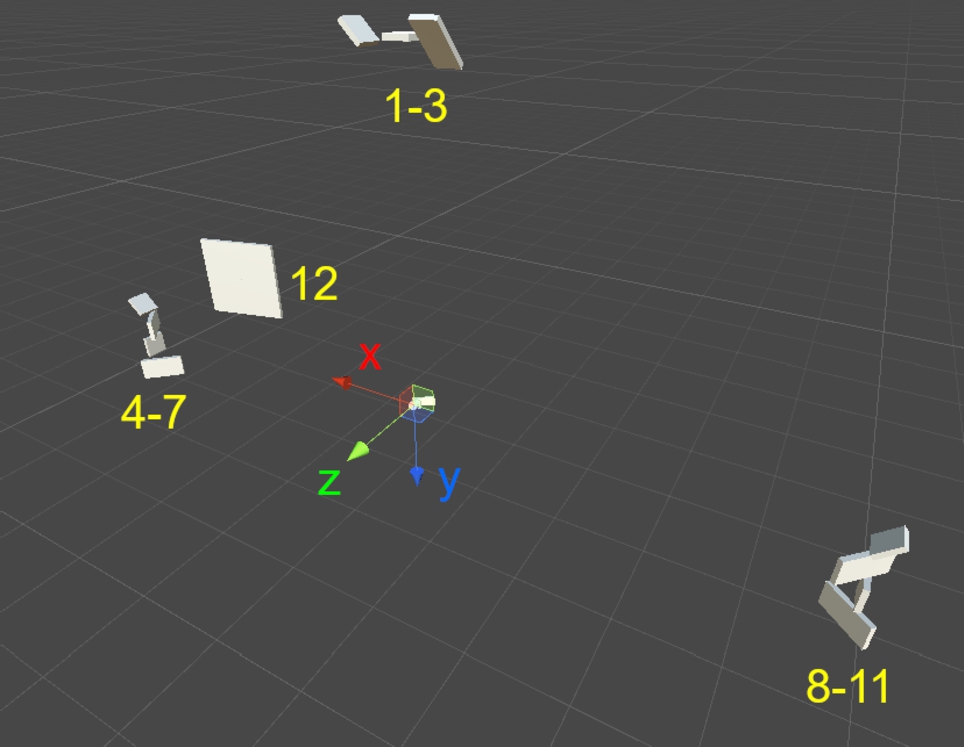

Overview for the simulated constellation of the reference geometries (grey planes) and the SOCS of the LS (RGB coordinate system) with respect to the actual experimental setup from section 4.1. The numbers indicate the

5 Results

The results shown in the following refer in section 5.1 to the measurement data of the simulated calibration environment (already introduced in section 4.4) and in section 5.2 to the real measurement data (already introduced in section 4.1). The applied methodological approach is identical in both cases and refers to the batch approach from section 4.2 and the novel recursive approach from section 4.3. Depending on the respective data source, the results are presented in different ways, which are briefly introduced and explained at the beginning of each subsection.

For practical reasons, all the results are based on 15 rotations of the LS only, which corresponds to a total measuring time of 1.5 seconds. One full rotation corresponds to one epoch k. In addition, to ensure comparability, only five LS point observations

5.1 Simulated calibration data

The realisation and usage of simulated observations for the calibration of the LS with respect to the PCS allow statistical comparisons against the true nominal values. No large outliers were simulated within the model, but rather controlled conditions were established that correspond to the character of a well-controllable laboratory calibration. In order to make statistically verifiable statements, a closed-loop MC simulation (cf. [34]) is applied. Thus, a variety of slightly different realisations can be achieved. For this purpose, after simulating perfect 3D PCLs for both positions of the LS and assigning them to the individual e reference planes per epoch k, random subsampling is performed. As an additional variation, random normally distributed observation noise with a fixed value of

At first, the required run time should be discussed, which is shown in Table 1 using the mean value over all

Run times of the different methods with respect to the mean and the standard deviation (std) based on

| Method | mean [s] | std [s] |

| batch C-GHM | 184.9 | 27.5 |

| recursive C-GHM (PM) | 5.2 | 0.9 |

| recursive C-GHM (COF) | 4.5 | 0.8 |

| recursive GHM (norm) | 3.9 | 0.7 |

In addition to the necessary run time, the actual calibration parameters are of interest. By knowing the true nominal values within the simulation, the root mean squared error (RMSE) serve as a statistical measure for comparing the different methods. The RMSE can be estimated within every S realisations for each epoch k according to

using the differences between the nominal values

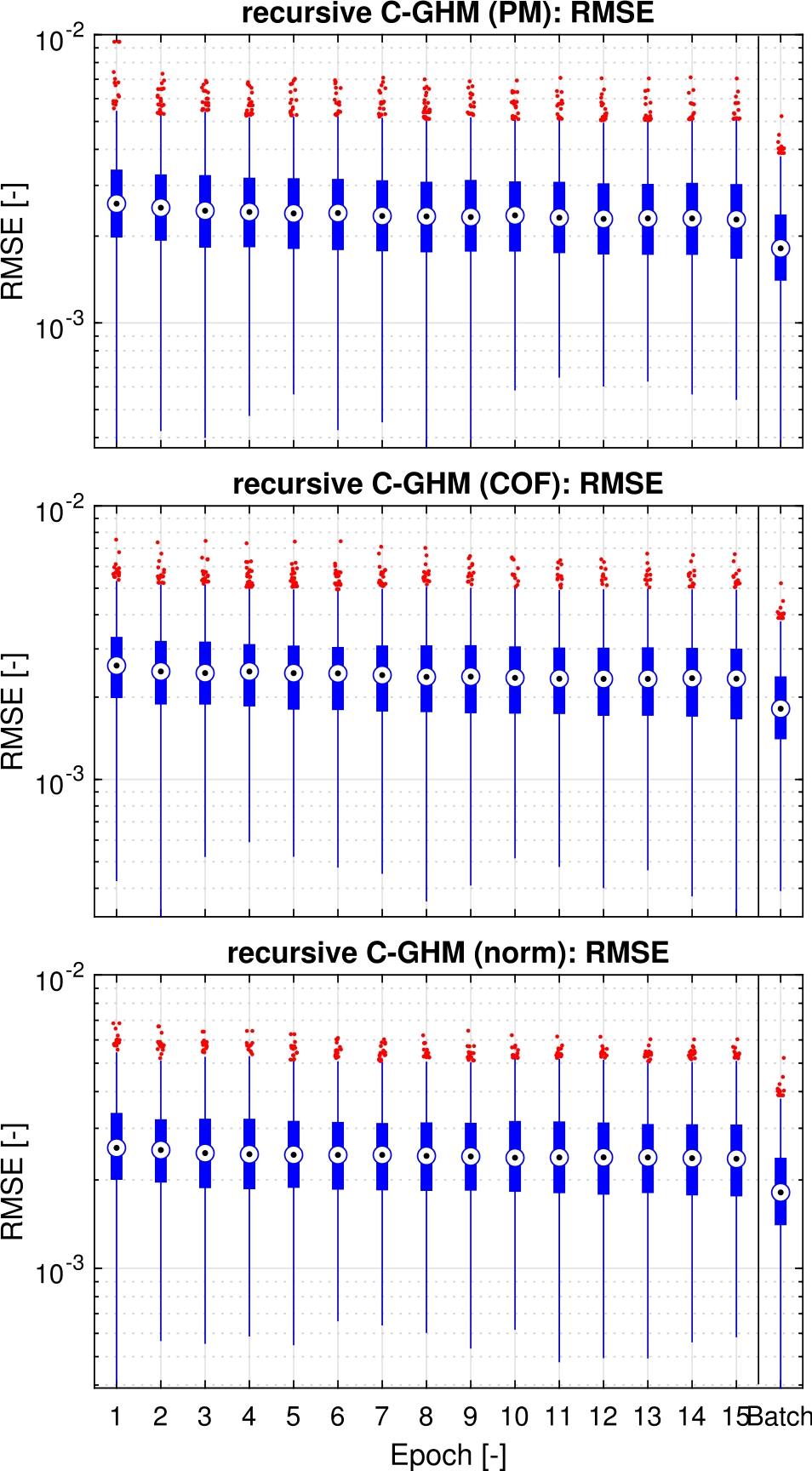

The results of the RMSE are presented in box plots grouped by the individual epochs. This is useful to show the whole set of results for all S realisations and reduces the impact of single failed runs or outliers at the same time. In a box plot, the circle indicates the median value, and the box describes all values between the 25th and 75th percentile. The whiskers span across all values in the range of 1.5 times the box interval. All other values are marked as outliers (red dots) but may only represent the tail end of the distribution. Due to the spread of resulting values, the vertical axis is scaled logarithmically. A comparison with the batch approach can be made by also calculating the RMSE for the estimated parameters and giving them independently of the epochs.

Figure 6 shows the results when the RMSE is based on the 6-DoF calibration parameters only. All recursive methods show comparable results since the median is almost identical. Therefore, there are no major improvements over the epochs in the recursive procedures. This indicates that additional observations have no significant influence on the parameters. It is noticeable, that the batch solution (last column) has a slightly smaller RMSE value, which is due to the entirety of observations taken into account at the same time.

Box plot of the epoch wise RMSE for the LS pose of recursive C-GHM with perfect measurements (PM) and the constrained objective function (COF) and the recursive GHM with extended functional model (norm), all compared to the result of the batch processing in the last column. Vertical axis units are a combination of translations in meters and rotations in radians.

If the RMSE is determined on the basis of the entire state parameters, box plots as shown in Figure 7 are obtained. There is a slight increase in the RMSE values across all methods compared to Figure 6. In addition, all the investigated approaches behave identically and there is no change over the individual epochs. The previously occurring advantage of the batch approach is no longer present when the entire parameter vector is taken into account.

Box plot of the epoch wise RMSE for all parameters of recursive C-GHM with perfect measurements (PM) and the constrained objective function (COF) and the recursive GHM with extended functional model (norm), all compared to the result of the batch processing in the last column. Vertical axis units are a combination of translations in meters, rotations in radians and the plane parameters (normal vectors and distances in meters).

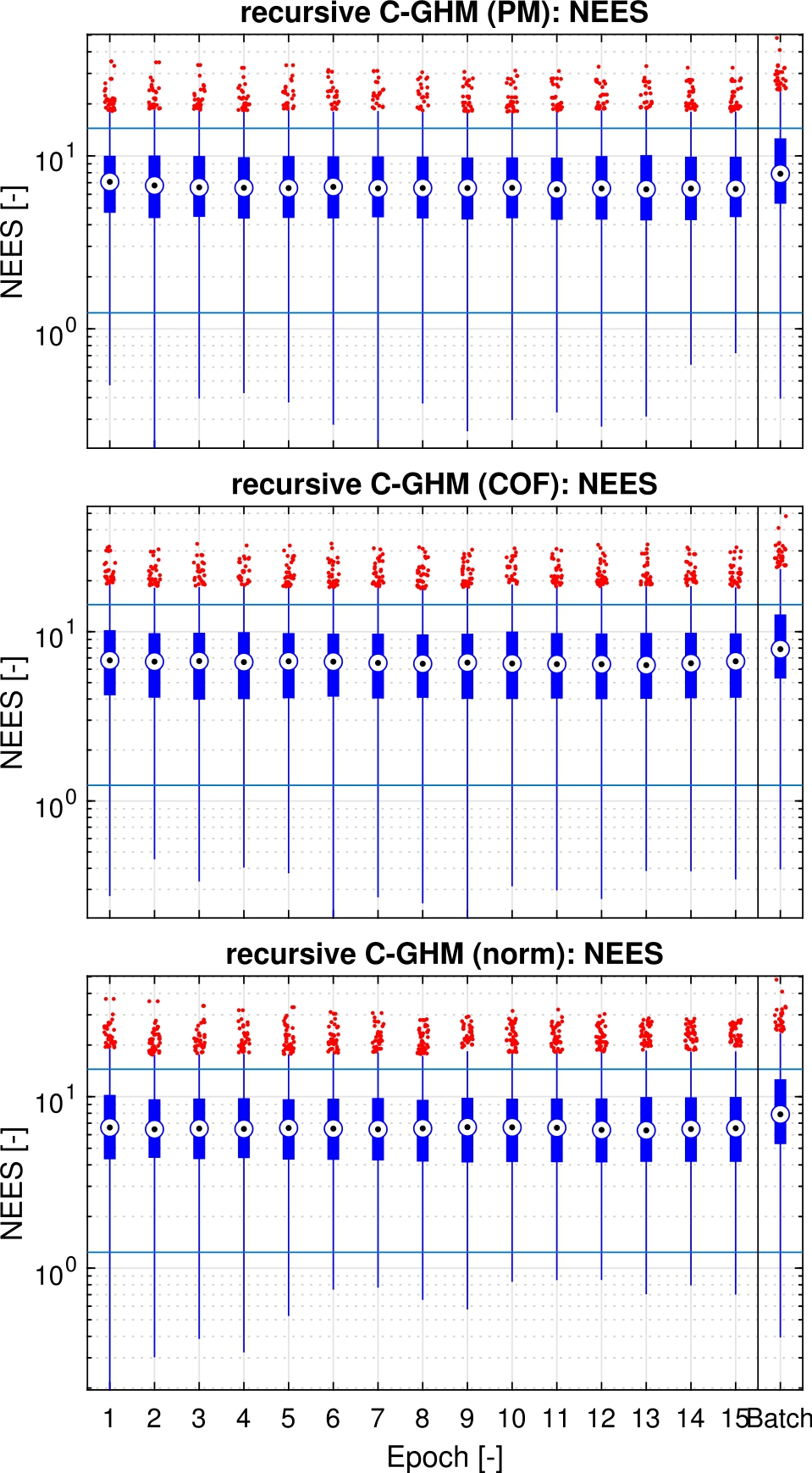

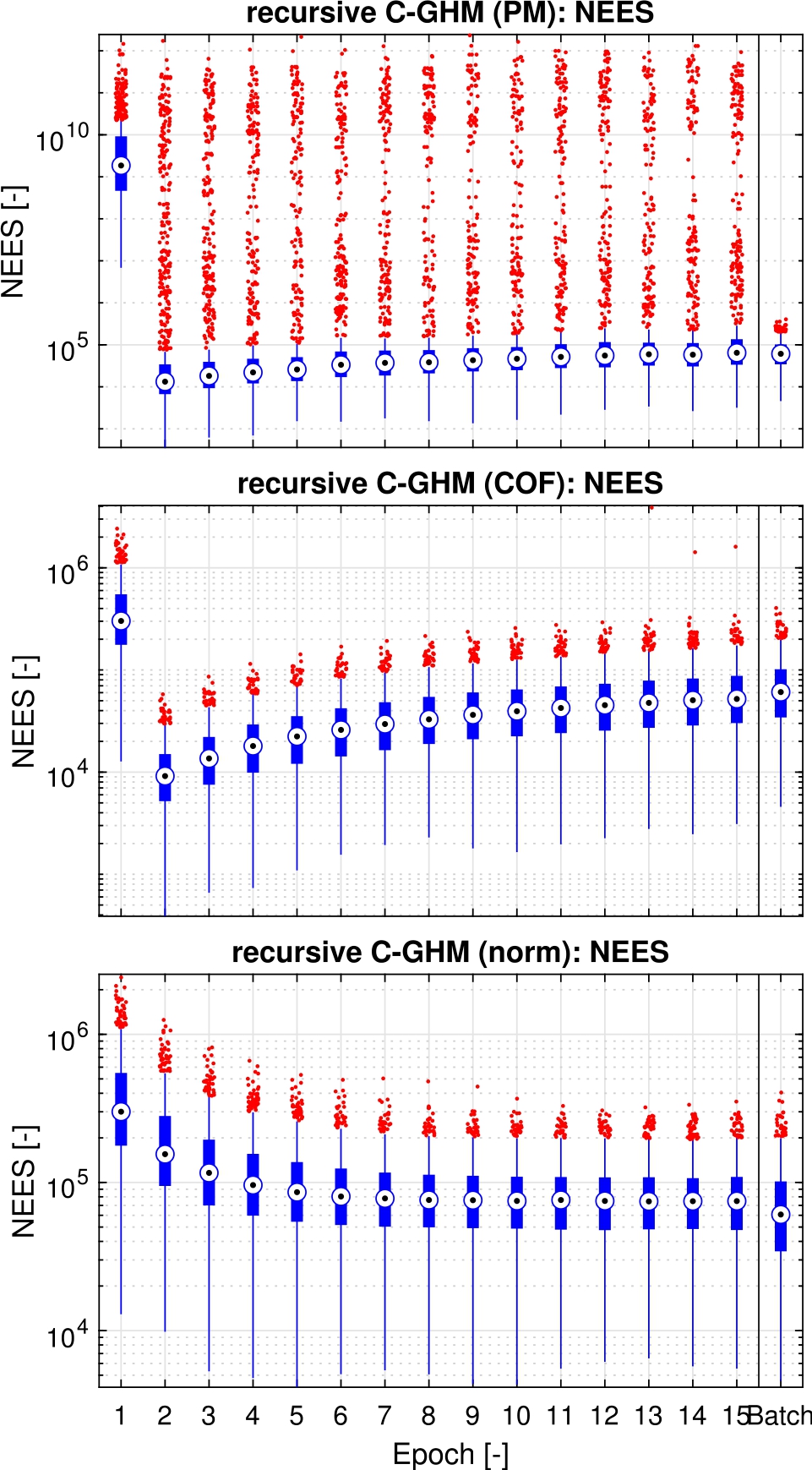

Furthermore, it is advisable to check consistency of the recursive filter approaches, which forms the basis for the recursive GHM. A state estimator is consistent if the estimates converge to the true value. Possible reasons why this is not the case are modeling, numerical or programming errors. A statistical test to verify the filter consistency is introduced in [1]. Since the true nominal values are known within the framework of this simulation, this verification is recommended. For this, the Normalized (state) estimation error squared (NEES)

where the differences between true state

is fulfilled. In case of a significance level of

Figure 8 shows the NEES for the first six parameters. Generally, the behaviour is similar to that shown in Figure 6 when using the RMSE. The only difference is that the NEES value for the batch solution deviates slightly from the recursive values, but apart from the outliers it is always within the limits. The same applies to the recursive approaches. Also here, no changes can be detected over the individual epochs.

Box plot of the epoch wise NEES for the scanner pose of recursive C-GHM with perfect measurements and the constrained objective function and the recursive GHM with an extended functional model, all compared to the result of the batch processing in the last column, vertical axis units are a combination of translations in meters and rotations in radians. The borders of the acceptance intervals for the NEES are shown as horizontal lines.

Significantly different results are shown when the entire state vector for the NEES is considered. The results in this case are shown in Figure 9. Considering the complete state vector for the NEES leads to a significant increase in all the random variables, whereas for the RMSE, the change is only about one order of magnitude. Therefore, all test values are larger than the

Box plot of the epoch wise NEES for all parameters of recursive C-GHM with perfect measurements and the constrained objective function and the recursive GHM with an extended functional model, all compared to the result of the batch processing in the last column. The vertical axis units combine translations in meters, rotations in radians and the plane parameters (normal vectors and distances in meters). The borders of the acceptance intervals for the NEES are shown as horizontal lines. Due to the logarithmic scale, these are no longer visible separately.

5.2 Real calibration data

In contrast to the simulated observation data in section 5.1, the nominal 6-DoF calibration parameters for the real observations are unknown. Furthermore, no reference values can be realised on the basis of a sensor of superior accuracy and precision since high-precision sensor technology, and state-of-the-art methods are already in use. As already mentioned above, the use of an MC simulation is therefore advisable. Thereby, many different data sets are realised, which differ exclusively based on the random subsampling of the LS observations. This enables an analysis of the scatter of the estimated parameters and a comparison between the individual methods.

The actual comparison at the level of the parameters is done exclusively for the translation

Results of real data processing compared (mean and standard deviation) for the values between the 0.5% and the 99.5% quantile.

| Method | ||

| batch C-GHM | 15.45 ± 0.29 | 0.151 ± 0.027 |

| recursive C-GHM (PM) | 13.76 ± 0.31 | 0.153 ± 0.053 |

| recursive C-GHM (COF) | 13.77 ± 0.31 | 0.155 ± 0.053 |

| recursive GHM (norm) | 13.78 ± 0.31 | 0.153 ± 0.055 |

The comparison of the different adjustment techniques in Table 2 is based on a variety of different subsampled realisations. However, this also provides insufficient insight into which approach best fits the true values. Thus, only conclusions regarding the precision of the individual approaches can be stated. Another possibility for a statistically verifiable analysis of the different methods without known nominal values is the application of a (

The resulting large amount of observations prohibits timely processing with the batch C-GHM, so it is omitted and the investigations are only done between the recursive approaches. Instead, a recursive GHM without constraints is applied, whereas the referencing observations from the laser tracker are treated as deterministic variables. This can again indicate the added value of using geometric constraints. The histograms of all contradictions for the corresponding four recursive methods are shown in Figure 10. The contradictions of the recursive GHM without taking constraints into account show the most extensive spread in the results. In addition, a multimodal distribution and a slight bias can be identified for this approach. This is assumed to be caused by the LT observations, which were only considered as deterministic quantities in this specific approach. This behaviour thus illustrates the significance of estimating the additional parameters within the other methods, although this needs to be analysed in more detail in further investigations. Also, some of the contradictions are beyond the value range of

Histograms of the contradictions for the recursive approaches of the GHM, each with different consideration of constraints. The data is based on 100 independent 10-fold cross-validations for each approach.

5.3 Discussion

Based on the simulated and the real calibrations, the following findings can be made. In general, both the batch and the different recursive approaches do not differ significantly in terms of the 6-DoF calibration parameters. However, the required computation time is significantly lower with the recursive approach. This is a significant advantage, especially concerning larger data sets. In addition, it is shown that for the recursive calculation already one or two epochs can be sufficient for accurate calibration parameters. This can positively affect the required run time since additional observations do not necessarily lead to a steady improvement, at least in the application presented here. In this context, however, it is necessary to investigate in the future also for the batch approach to what extent the number of observations affects the quality of the parameters and the required computation times.

For the consideration of the constraints in the recursive approaches, it is noticeable that numerical instabilities in the PM method may cause wrong parameters conspicuously often. Consideration using the COF method and the normalized functional relationship are more reliable in this respect. The latter is characterized by the lowest overall run times but leads to less accurate estimates of the plane parameters. It has to be noted that the comparison of the plane parameters to the nominal values technically is not possible when using the normalized functional relationship. Because of the missing constraint, the parameters can just be scaled in comparison to the true values. However, the parameters of the reference geometries are consistently inaccurate with all applied methods. A reason for this behaviour could not be found. This situation is also shown because the calculated co-variances of the plane parameters are too optimistic and lead to an inconsistent estimation. However, if only the 6-DoF calibration parameters are considered, the consistency of the recursive estimator based on the

The general advantage of using constraints when calibrating with reference geometries is shown in the context of cross-validation. If the plane parameters are introduced as deterministic quantities, this leads to a significantly wider dispersion of the contradictions. The specific method by which the constraints are taken into account is of secondary importance. The accuracy and precision with respect to the pure 6-DoF calibration parameters are similar overall, although there are relevant differences with respect to the numerical stability.

The major advantage of the recursive C-GHM is the significant run time improvement compared with a batch approach. This can be of particular relevance for potential real-time applications or steadily increasing data sets. With respect to the calibration of an LS, for example, this may be the case if the sensor has multiple scan lines (e. g. Velodyne HDL-64 [59]), the calibration setup uses more individual reference geometries (for higher redundancy) or multiple individual positions (for decorrelation) for a more reliable estimation are used.

6 Conclusion

The steadily increasing application of high-resolution sensors for environment acquisition and the simultaneous combination of multiple individual sensors as MSSs results in increasingly large amounts of data. In this paper, a recursive GHM was presented, allowing more efficient processing of mass data than existing batch methods with unchanged uncertainty characteristics. The basis for this is an IEKF, which can take implicit observation functions into account. Depending on the respective application of this new methodology, it is necessary to select suitable approximation values and a suitable process noise to avoid numerical instabilities. To consider additional information, various possibilities for introducing appropriate constraints and their corresponding added value have also been pointed out. This additional information is currently limited to equality constraints, although the transition to inequality constraints opens up further possibilities and should therefore be aimed for. In contrast, the consideration of soft constraints is possible without further effort, although numerical issues may arise and were therefore not investigated here.

As a practical application example for the methodology, the determination of calibration parameters of a 3D LS concerning a fixed PCS was presented. This is a mandatory procedure for the precise operation of any MSS. Especially for mobile mapping applications or autonomous driving, the novel recursive calculation offers new possibilities (e. g. in-situ calibration). However, this requires robustification of the approach against the influence of outliers and the automatic detection and assignment of suitable geometric primitives in object space. With respect to the actual 6-DoF calibration parameters, there were no significant differences, but the recursive computations were significantly faster than the batch approach. However, methodologically induced numerical instabilities may appear when the constraints were considered as PM. For this particular application example, further investigations into the joint estimation of more than two positions are foreseen in the future to achieve an improved decorrelation of the calibration parameters.

In addition, the recursive C-GHM methodology is also transferable to any other application where efficient adjustment of epoch-wise observations or mass data is required. To further validate the methodology, it is recommended to use applications that enable an independent and higher-level reference solution.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: RTG 2159

Funding statement: This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the Research Training Group i.c.sens [RTG 2159]. Furthermore, parts of the computations were performed by the compute cluster, which is funded by the Leibniz Universität Hannover, the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture (MWK) and DFG.

References

[1] Y. Bar-Shalom, X.-R. Li and T. Kirubarajan, Estimation with Applications to Tracking and Navigation: Theory, Algorithms and Software, Wiley, New York, NY, 2001.10.1002/0471221279Suche in Google Scholar

[2] W. Błaszczak-Bąk, Z. Koppanyi and C. Toth, Reduction Method for Mobile Laser Scanning Data, in: ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf., 7(7), pp. 1–13, 2018.10.3390/ijgi7070285Suche in Google Scholar

[3] J. M. Brockmann and W.-D. Schuh, Computational Aspects of High-resolution Global Gravity Field Determination–Numbering Schemes and Reordering, in: NIC Symposium 2016, No. FZJ-2016-02087, John von Neumann-Institut für Computing, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Y.-T. Chiang, L.-S. Wang and F.-R. Chang, Filtering Method for Nonlinear Systems with Constraints, in: IEEE Proceedings – Control Theory and Applications, 149(6), pp. 525–531, 2002.10.1049/ip-cta:20020799Suche in Google Scholar

[5] T. Dang, Kontinuierliche Selbstkalibrierung von Stereokameras, Ph. D. Thesis, Schriftenreihe / Institut für Mess- und Regelungstechnik, KIT, Univ.-Verl. Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] T. Dang, An Iterative Parameter Estimation Method for Observation Models with Nonlinear Constraints, in: Metrology and Measurement Systems, 15(4), pp. 421–432, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] W. F. Denham and S. Pines, Sequential Estimation When Measurement Function Nonlinearity Is Comparable to Measurement Error, in: AIAA Journal, 4(6), pp. 1071–1076, 1966.10.2514/6.1965-1220Suche in Google Scholar

[8] X. Du and Y. Zhuo, A Point Cloud Data Reduction Method Based on Curvature, in: 2009 IEEE 10th International Conference on Computer-Aided Industrial Design & Conceptual Design, pp. 914–918, 2009.10.1109/CAIDCD.2009.5375038Suche in Google Scholar

[9] B. Efron and R. Tibshirani, An Introduction to the Bootstrap, Chapman & Hall, New York, 1993.10.1007/978-1-4899-4541-9Suche in Google Scholar

[10] B. Efron and T. Hastie, Computer Age Statistical Inference: Algorithms, Evidence, and Data Science, Institute of Mathematical Statistics monographs, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2016.10.1017/CBO9781316576533Suche in Google Scholar

[11] J. Elseberg, D. Borrmann and A. Nüchter, Algorithmic Solutions for Computing Precise Maximum Likelihood 3d Point Clouds from Mobile Laser Scanning Platforms, in: Remote Sensing, 5(11), pp. 5871–5906, 2013.10.3390/rs5115871Suche in Google Scholar

[12] J. Elseberg, D. Borrmann and A. Nüchter, One Billion Points in the Cloud – an Octree for Efficient Processing of 3D Laser Scans, in: ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 76, pp. 76–88, 2013.10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2012.10.004Suche in Google Scholar

[13] D. Ernst, Objektraumbasierte Kalibrierung und Georeferenzierung eines Unmanned Aerial Systems, Bachelor Thesis (unpublished), Leibniz Universität Hannover, Hanover, 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] A. Ettlinger, H. Neuner and T. Burgess, Development of a Kalman Filter in the Gauss-helmert Model for Reliability Analysis in Orientation Determination with Smartphone Sensors, in: Sensors, 18(2), 414, pp. 1–21, 2018.10.3390/s18020414Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] N. Garcia-Fernandez, H. Alkhatib and S. Schön, Collaborative Navigation Simulation Tool Using Kalman Filter with Implicit Constraints, in: ISPRS Annals of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, IV-2/W5, pp. 559–566, 2019.10.5194/isprs-annals-IV-2-W5-559-2019Suche in Google Scholar

[16] J. de Geeter, H. van Brussel, J. de Schutter and M. Decreton, A Smoothly Constrained Kalman Filter, in: IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 19(10), pp. 1171–1177, 1997.10.1109/34.625129Suche in Google Scholar

[17] G. Gräfe, Kinematische Anwendungen von Laserscannern im Straßenraum, Ph. D. Thesis, Issue 84, Universität der Bundeswehr München, Fakultät für Bauingenieur- und Vermessungswesen, Neubiberg, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] N. Gupta and R. Hauser, Kalman Filtering with Equality and Inequality State Constraints, https://arxiv.org/abs/0709.2791, Accessed: 2019-10-05, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] J. Hartmann, J.-A. Paffenholz, T. Strübing and I. Neumann, Determination of Position and Orientation of Lidar Sensors on Multisensor Platforms, in: Journal of Surveying Engineering, 143(4), pp. 1–11, 2017.10.1061/(ASCE)SU.1943-5428.0000226Suche in Google Scholar

[20] J. Hartmann, P. Trusheim, H. Alkhatib, J.-A. Paffenholz, D. Diener and I. Neumann, High Accurate Pointwise (Geo-)Referencing of a k-TLS Based Multi-sensor-system, in: ISPRS Annals of Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, IV-4, pp. 81–88, 2018.10.5194/isprs-annals-IV-4-81-2018Suche in Google Scholar

[21] J. Hartmann, I. von Gösseln, N. Schild, A. Dorndorf, J.-A. Paffenholz and I. Neumann, Optimisation of the Calibration Process of a k-TLS Based Multi-sensor-system by Genetic Algorithms, in: ISPRS – International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII-2/W13, pp. 1655–1662, 2019.10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-2-W13-1655-2019Suche in Google Scholar

[22] A. Heiker, Mutual Validation of Earth Orientation Parameters, Geophysical Excitation Functions and Second Degree Gravity Field Coefficients, Ph. D. Thesis, DGK, Reihe C, 697, Munich, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] E. Heinz, C. Holst, H. Kuhlmann and L. Klingbeil, Design and Evaluation of a Permanently Installed Plane-based Calibration Field for Mobile Laser Scanning Systems, in: Remote Sensing, 12(3), pp. 1–29, 2020.10.3390/rs12030555Suche in Google Scholar

[24] C. Hesse, Hochauflösende kinematische Objekterfassung mit terrestrischen Laserscannern, Ph. D. Thesis, DGK, Reihe C, 608, Munich, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Hexagone Metrology, Leica Absolute Tracker AT960 (Product Brochure): Absolute Portability. Absolute Speed. Absolute Accuracy, https://w3.leica-geosystems.com/downloads123/m1/metrology/general/brochures/leica%20at960%20brochure_en.pdf, Accessed: 2020-02-05.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] G. H. Hostetter, Recursive Estimation, in: Handbook of Digital Signal Processing, Academic Press, pp. 899–940, 1987.10.1016/B978-0-08-050780-4.50018-7Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Ibeo Automotive Systems, ibeoNEXT Generic 4D Solid State LiDAR: Die Zukunft des autonomen Fahrens!, https://www.ibeo-as.com/de/produkte/sensoren/ibeoNEXTgeneric, 2020, Accessed: 2020-02-06.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] R. Jäger, T. Müller, H. Saler and R. Schwäble, Klassische und robuste Ausgleichungsverfahren: Ein Leitfaden für Ausbildung und Praxis von Geodäten und Geoinformatikern, Wichmann, Heidelberg, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] G. James, D. Witten, T. Hastie and R. Tibshirani, An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R, Springer, New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London, 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] R. E. Kalman and R. S. Bucy, New Results in Linear Filtering and Prediction Theory, in: Journal of Basic Engineering, 83(1), pp. 95–108, 1961.10.1115/1.3658902Suche in Google Scholar

[31] R. Klees, P. Ditmar and J. Kusche, Numerical Techniques for Large Least-squares Problems with Applications to Goce, in: V Hotine-Marussi Symposium on Mathematical Geodesy, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 12–21, 2004.10.1007/978-3-662-10735-5_3Suche in Google Scholar

[32] K.-R. Koch, Parameter Estimation and Hypothesis Testing in Linear Models, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1999.10.1007/978-3-662-03976-2Suche in Google Scholar

[33] K.-R. Koch, Robust estimations for the nonlinear Gauss Helmert model by the expectation maximization algorithm, in: Journal of Geodesy, 88(3), pp. 263–271, 2014.10.1007/s00190-013-0681-9Suche in Google Scholar

[34] D. P. Kroese, T. Taimre and Z. I. Botev, Handbook of Monte Carlo Methods, John Wiley & Sons, 2011.10.1002/9781118014967Suche in Google Scholar

[35] L. Lenzmann and E. Lenzmann, Strenge Auswertung des nichtlinearen Gauß-Helmert-Modells, in: AVN (Allgemeine Vermessungs-Nachrichten), 111(2), pp. 68–73, 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

[36] M. Lösler and M. Nitschke, Bestimmung der Parameter einer Regressionsellipse in allgemeiner Raumlage, in: AVN (Allgemeine Vermessungs-Nachrichten), 117(3), pp. 113–117, 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] R. P. Lutter and T. Olson, Multi-Sensor System, US 6771208 B2, https://patents.google.com/patent/US6771208, 2004, Accessed: 2020-02-06.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] J. E. Mulquiney, J. P. Norton, A. J. Jakeman and J. A. Taylor, Random Walks in the Kalman Filter: Implications for Greenhouse Gas Flux Deductions, in: Environmetrics, 6(5), pp. 473–478, 1995.10.1002/env.3170060509Suche in Google Scholar

[39] W. Niemeier, Ausgleichungsrechnung: Statistische Auswertemethoden, De Gruyter, Berlin, 2008.10.1515/9783110206784Suche in Google Scholar

[40] T. Peters and C. Brenner, Conditional Adversarial Networks for Multimodal Photo-realistic Point Cloud Rendering, in: M. Raubal, S. Wang, M. Guo, D. Jonietz, and P. Kiefer, Editors, Spatial Big Data and Machine Learning in GIScience, GIScience Workshop 2018, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 48–53, 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] R. L. Plackett, Some Theorems in Least Squares, in: Biometrika, 37(1/2), pp. 149–157, 1950.10.1093/biomet/37.1-2.149Suche in Google Scholar

[42] J. Porrill, Optimal Combination and Constraints for Geometrical Sensor Data, in: The International Journal of Robotics Research, 7(6), pp. 66–77, 1988.10.1177/027836498800700606Suche in Google Scholar

[43] E. Puttonen, M. Lehtomäki, H. Kaartinen, L. Zhu, A. Kukko and A. Jaakkola, Improved Sampling for Terrestrial and Mobile Laser Scanner Point Cloud Data, in: Remote Sensing, 5(4), pp. 1754–1773, 2013.10.3390/rs5041754Suche in Google Scholar

[44] A. Rietdorf, Automatisierte Auswertung und Kalibrierung von scannenden Messsystemen mit tachymetrischem Messprinzip, Ph. D. Thesis, DGK, Reihe C, 582, Munich, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Robosense, RS-LiDAR-32, https://www.robosense.ai/rslidar/rs-lidar-32, 2020, Accessed: 2020-02-06.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] L. R. Roese-Koerner, Convex Optimization for Inequality Constrained Adjustment Problems, Ph. D. Thesis, DGK, Reihe C, 759, Munich, 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[47] L. R. Roese-Koerner, B. Devaraju, W.-D. Schuh and N. Sneeuw, Describing the Quality of Inequality Constrained Estimates, in: The 1st International Workshop on the Quality of Geodetic Observation and Monitoring Systems (QuGOMS’11), pp. 15–20, 2015.10.1007/978-3-319-10828-5_3Suche in Google Scholar

[48] S. Schön, C. Brenner, H. Alkhatib, M. Coenen, H. Dbouk, N. Garcia-Fernandez, C. Fischer, C. Heipke, K. Lohmann, I. Neumann, U. Nguyen, J.-A. Paffenholz, T. Peters, F. Rottensteiner, J. Schachtschneider, M. Sester, L. Sun, S. Vogel, R. Voges and B. Wagner, Integrity and Collaboration in Dynamic Sensor Networks, in: Sensors, 18(7), pp. 1–21, 2018.10.3390/s18072400Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] K. P. Schwarz and N. El-Sheimy, Kinematic Multi-sensor Systems For Close Range Digital Imaging, in: ISPRS International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XXXI-5/W3, pp. 774–784, 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

[50] D. Simon, Optimal State Estimation, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2006.10.1002/0470045345Suche in Google Scholar

[51] D. Simon, Kalman Filtering with State Constraints: A Survey of Linear and Nonlinear Algorithms, in: IET Control Theory & Applications, 4(8), pp. 1303–1318, 2010.10.1049/iet-cta.2009.0032Suche in Google Scholar

[52] S. Soatto, R. Frezza and P. Perona, Motion Estimation on the Essential Manifold, in: Computer vision – ECCV’94, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 801, pp. 60–72, Springer, Berlin, 1994.10.1007/BFb0028335Suche in Google Scholar

[53] R. Steffen and C. Beder, Recursive Estimation with Implicit Constraints, in: F. A. Hamprecht, C. Schnörr and B. Jähne, Editors, Pattern Recognition, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 4713, pp. 194–203, Springer, Berlin, 2007.10.1007/978-3-540-74936-3_20Suche in Google Scholar

[54] R. Steffen, A Robust Iterative Kalman Filter Based On Implicit Measurement Equations, in: Photogrammetrie – Fernerkundung – Geoinformation, pp. 323–332, 2013.10.1127/1432-8364/2013/0180Suche in Google Scholar

[55] R. Steffen, Visual Slam from Image Sequences Acquired by Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Ph. D. Thesis, DGK, Reihe C, 709, Munich, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[56] T. Strübing and I. Neumann, Positions- und Orientierungsschätzung von LIDAR-Sensoren auf Multisensorplattformen, in: Zeitschrift für Geodäsie, Geoinformation und Landmanagement, 138(3), pp. 210–221, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

[57] C. Suchocki and W. Blaszczak-Bak, Down-sampling of Point Clouds for the Technical Diagnostics of Buildings and Structures, in: Geosciences, 9(2), 2019.10.3390/geosciences9020070Suche in Google Scholar

[58] J. Underwood, A. Hill and S. Scheding, Calibration of Range Sensor Pose on Mobile Platforms, in: IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Piscataway, NJ, pp. 3866–3871, 2007.10.1109/IROS.2007.4398971Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Velodyne LiDAR, Datasheet: HDL-64E: High Definition Real-time 3D Lidar, https://velodynelidar.com/products/hdl-64e/, 2018, Accessed: 2020-02-06.Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Velodyne LiDAR, Datasheet: Velodyne LiDAR Puck: Real-Time 3D LiDAR Sensor, https://velodynelidar.com/vlp-16.html, 2018, Assessed: 2019-12-12.Suche in Google Scholar

[61] H. Vennegeerts, Objektraumgestützte kinematische Georeferenzierung für Mobile-Mapping-Systeme, Ph. D. Thesis, DGK, Reihe C, 657, Munich, 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

[62] S. Vogel, H. Alkhatib and I. Neumann, Iterated Extended Kalman Filter with Implicit Measurement Equation and Nonlinear Constraints for Information-based Georeferencing, in: 21st IEEE International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), Cambridge, United Kingdom, pp. 1209–1216, 2018.10.23919/ICIF.2018.8455258Suche in Google Scholar

[63] S. Vogel, H. Alkhatib, J. Bureick, R. Moftizadeh and I. Neumann, Georeferencing of Laser Scanner-based Kinematic Multi-sensor Systems in the Context of Iterated Extended Kalman Filters Using Geometrical Constraints, in: Sensors, 19(10), pp. 1–22, 2019.10.3390/s19102280Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[64] S. Vogel, Kalman Filtering with State Constraints Applied to Multi-sensor Systems and Georeferencing, Ph. D. Thesis, DGK, Reihe C, 856, Munich, 2020.Suche in Google Scholar

[65] Y. Wang, Q. Chen, Q. Zhu, L. Liu, C. Li and D. Zheng, A Survey of Mobile Laser Scanning Applications and Key Techniques over Urban Areas, in: Remote Sensing, 11(13), pp. 1–20, 2019.10.3390/rs11131540Suche in Google Scholar

[66] K. Wichmann, Auswertung von Messdaten: Statistische Methoden für Geo- und Ingenieurwissenschaften, De Gruyter, Munich, 2007.10.1524/9783486844184Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Vogel et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Multiple incompatible datum points identification in vertical control network for high-speed railway based on likelihood ratio test

- Empirical influence functions and their non-standard applications

- Multi-frequency quadrifilar helix antennas for cm-accurate GNSS positioning

- Recursive Gauss-Helmert model with equality constraints applied to the efficient system calibration of a 3D laser scanner

- Artificial neural network for improving the estimation of weighted mean temperature in Egypt

- Automated near-field deformation detection from mobile laser scanning for the 2014 Mw 6.0 South Napa earthquake

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Multiple incompatible datum points identification in vertical control network for high-speed railway based on likelihood ratio test

- Empirical influence functions and their non-standard applications

- Multi-frequency quadrifilar helix antennas for cm-accurate GNSS positioning

- Recursive Gauss-Helmert model with equality constraints applied to the efficient system calibration of a 3D laser scanner

- Artificial neural network for improving the estimation of weighted mean temperature in Egypt

- Automated near-field deformation detection from mobile laser scanning for the 2014 Mw 6.0 South Napa earthquake