Toward trustworthy AI with integrative explainable AI frameworks

-

Bettina Finzel

Abstract

As artificial intelligence (AI) increasingly permeates high-stakes domains such as healthcare, transportation, and law enforcement, ensuring its trustworthiness has become a critical challenge. This article proposes an integrative Explainable AI (XAI) framework to address the challenges of interpretability, explainability, interactivity, and robustness. By combining XAI methods, incorporating human-AI interaction and using suitable evaluation techniques, the implementation of this framework serves as a holistic XAI approach. The article discusses the framework’s contribution to trustworthy AI and gives an outlook on open challenges related to interdisciplinary collaboration, AI generalization and AI evaluation.

1 Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly shaping various aspects of society, necessitating regulatory measures to ensure its safe and ethical deployment. One of the latest regulatory efforts in this regard is the European AI Act, which entered into force in August 2024 [1]. The EU AI Act provides a legal framework for AI systems, categorizing them based on risk levels and imposing strict requirements on high-stakes AI applications such as healthcare, transportation and law enforcement [2].

As AI systems become more embedded in high-stakes domains, the concept of trustworthy AI has gained prominence [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]. In general, trustworthy AI refers to systems that possess characteristics considered worth to be relied on. For example, according to a survey by Ali et al. [3], trustworthy AI refers to AI systems that are transparent, fair and responsible, meaning they are accountable.

In this context, transparency refers to the explicit disclosure and availability of access to AI’s internal decision-making mechanisms. Fair systems are designed to be free from societal or technically induced biases, thereby preventing unjustified disadvantages and failures [8]. Transparency and fairness are, in turn, fundamental prerequisites for the responsible deployment of AI systems in accordance with ethical principles, societal norms, and legal requirements. Furthermore, trustworthy AI is based on interpretable, explainable, interactive and robust systems [3] that can be understood, controlled and relied on.

Interpretability of trustworthy AI refers to the self-explanatory nature of AI systems [9], including machine-learned models and their decisions. Interpretability is given, whenever the meaning of internal processes in models, their constituents, and their outputs is inherently clear and comprehensible. Explainability, on the other hand, denotes the ability to provide explanations for decisions made by complex and opaque “black-box” models, such as deep neural networks, to make them understandable to humans. This includes both data-centered explanations [3] and mechanistic explainability [10]. Both explainability and interpretability benefit from interactivity [11], meaning that AI models, their decisions, and generated explanations can be iteratively explored and revised by humans [12]. Through guidance, AI systems shall become not only more comprehensible [13] but also more controllable [14].

Ultimately, the development of trustworthy AI aims for stakeholder satisfaction and acceptance [3], addressing needs of regulators, developers, experts and non-experts as well as affected end-users [12], while promoting and ensuring justified trust [15]. Trustworthy AI is therefore a broad field that requires interdisciplinary collaboration among stakeholders, depending on the specific challenge addressed [3], [4], [5], [6], [7].

From the multitude of mentioned aspects, this article aims to specifically address the challenges of interpretability, explainability, interactivity, and robustness in trustworthy AI, and to demonstrate how these can be integrated into a technically feasible framework.

Overall, this article seeks to promote and define an integrative XAI framework, illustrate its realization for machine learning in digital healthcare, and to demonstrate how it can contribute to AI evaluation and generalization to advance trustworthy AI in complex and critical application domains.

The article is structured as follows. In Section 2, the article emphasizes on the contribution of XAI and integrative frameworks to solving challenges in making AI trustworthy. As a foundation, the necessary terminology for defining and implementing integrative XAI frameworks is introduced, along with application examples from digital healthcare. Additionally, suitable XAI-based model evaluation methods are briefly introduced. After a short summary of XAI’s contribution to trustworthy AI, the proposed integrative XAI framework is introduced in Section 3. The article gives an original definition and names the key components for integrative XAI frameworks. Next, an existing implementation of the proposed integrative XAI framework is described and illustrated in Section 4. First, an overview of the framework’s architectural realization is provided followed by a brief introduction of methods suitable for implementing the framework’s individual constituents and explanatory approaches. Based on a unified perspective on integrative XAI frameworks, the interdisciplinary nature, theoretical foundation in reasoning and contribution of the proposed solution to AI evaluation is discussed in Section 5. The article synthesizes the key contributions and limitations of the proposed framework toward trustworthy AI in comparison to specialized XAI methods in Section 6 and concludes with an outlook on open challenges related to generalization and socio-technical aspects.

2 The role of explainable AI (XAI) in trustworthy AI

The principal dimensions of trustworthy AI as introduced in Ali et al. [3] are illustrated in Figure 1. Here, the challenges associated with the development of trustworthy AI are grouped into two distinct but interrelated categories: (1) technical and cognitive challenges in trustworthy AI, and (2) socio-technical challenges in trustworthy AI. While robustness, explainability, interpretability and interactivity are considered to be mainly concerned with the technical development and testing of AI software and with cognitively-inspired human-AI interaction, transparency, fairness, responsibility and satisfaction are considered to be of socio-technical nature, involving regulatory, societal as well as ethical aspects.[1]

![Figure 1:

Key aspects of trustworthy AI as introduced by Ali et al. [3], covering interpretability, explainability, interactivity and robustness of AI (considered as technical or cognitive challenges in trustworthy AI development and evaluation here) as well as transparency, fairness, responsibility and satisfaction (considered as socio-technical challenges here).](/document/doi/10.1515/itit-2025-0007/asset/graphic/j_itit-2025-0007_fig_001.jpg)

Key aspects of trustworthy AI as introduced by Ali et al. [3], covering interpretability, explainability, interactivity and robustness of AI (considered as technical or cognitive challenges in trustworthy AI development and evaluation here) as well as transparency, fairness, responsibility and satisfaction (considered as socio-technical challenges here).

A major driver in the implementation of trustworthy AI is research in the field of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) [16]. One of its primary objectives is to contribute to trustworthy AI by developing techniques that allow users to understand and trust AI decisions [3]. Over the past years, the XAI community has proposed a variety of theoretical frameworks, methodologies, metrics, and experimental approaches to develop interpretable, explainable, interactive and robust AI methods [16]. The following section introduces key terminology necessary to understand how the combination of various XAI methods can contribute to an integrative framework and, consequently, to trustworthy AI.

2.1 XAI terminology and examples from digital healthcare

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) is a research field dedicated to developing methods that either provide inherent interpretability within machine learning models or make opaque “black box” models, such as neural networks, explainable [17]. XAI aims to bridge the gap between the complexity of advanced AI models and the need for human stakeholders to comprehend, control and ultimately trust these models. For that purpose a multitude of methods has been developed so far with distinct characteristics and specialized terminology describing them (see for example [3], [16], [18] for a detailed overview).

The concept of explanation is at the core of XAI research. The word explanation is etymologically derived from the Latin verb explanare, containing the adjective

In the context of XAI, the term explainer refers to a tool or method used to generate explanations for the decisions made by an AI model. An explainer works by analyzing the model’s inputs, processes or outputs to provide insights that help humans (the explainees) understand the reasons behind a specific prediction or behavior [12], [16]. Explainees may be experts, non-experts or developers that each have a unique information need [12]. In general, they are stakeholders of explanation outcomes. For example, in digital healthcare, explainees may be regulators in medical law, clinicians and medical experts, non-experts like insurers as well as affected end-users, the patients.

The main purpose of an explanation is seen in the literature as answering “Why?” and “How?” questions [23]. These go beyond asking “What is this? What does this do?” (for example, the answer “rain” to the question “What is that falling from the sky?” would not be considered an explanation). Instead, the question “Why does it fall from the sky?” could be explained with a reference to the formation of clouds in the atmosphere and gravity as reasons for rain, while the question “How does rain form?” could be answered with an explanation of the chemistry and physics of cloud formation and gravity, that is how rain works. The question “Why do you take an umbrella?” asks for a different explanation than the question “How do you open an umbrella?”. While the first question asks for a reason as in the rain example (here an intent or a motivation rather than a mechanical cause), the second question is about instructions (how to open an umbrella). In general, humans tend to ask for reasons in explanations by posing the “Why?” question [22] in order to gain an understanding about the explanandum’s purpose (which is referred to as functional understanding [10]). Explanations to the question “How?” depend on whether it is a request for how something works (mechanistic understanding [10]) or whether it is a question of how something is done (instructional explanations [20]). The following tabular overview introduces the key terms characterizing explanation methods and gives examples for the domain of digital healthcare (see Tables 1–3).

Part I of the overview on common XAI terminology with definitions and example use cases, primarily from digital healthcare scenarios. Part I presents the basic terminology to characterize XAI methods.

| Term | Definition | Example usage in digital healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent interpretability | Denotes the characteristic of a model to be naturally interpretable without needing external explanation methods. Interpretability is a core feature, allowing users to understand the reasoning behind predictions directly from the model’s structure or behavior [9], [16], [25]. | In digital pathology, a rule-based model that directly maps patient features (such as the presence of tumor tissue in other tissues) to invasion depth and severity of cancer would be inherently interpretable, as its decision path is considered clear and understandable to the human recipient [24], [26]. |

| Post-hoc explanation | Refers to explanations generated after a model’s prediction, usually applied to “black-box” models like deep neural networks. These explanations attempt to reveal the decision-making logic of the model or data-specific features that influenced the model’s output [3], [16], [18]. | In digital pathology, a post-hoc explanation might clarify why a model predicted a certain tissue being present in a sample by highlighting the most relevant features in the tissue’s morphology, even if the internal workings of the model are not inherently interpretable [27]. |

| Global explanation | Refers to an explanation that describes the overall behavior of a model. This type of explanation helps to understand the general decision-making process of a model across all possible inputs [3], [16], [18], [28], [29]. | In digital pathology, a global explanation might reveal how a model diagnoses tumor tissue across all given samples based on general factors such as the occurrence of tumor cells, specific tissue textures or the localization and spatial constellation of relevant areas in tissue samples [12], [24], [26], [30]. |

| Local explanation | Focuses on explaining individual predictions made by a model. It seeks to explicate why the model produced a particular output for a given input [3], [16], [18], [28], [29]. | In the context of digital pathology, if an AI model predicts that a patient has a tumor of certain severity, a local explanation can highlight the specific factors, such as tumor cells detected in a specific tissue sample, that influenced the prediction for this patient [27]. It may also explicate the spatial constellation of different tissues, for example, to explain the resulting invasion depth of a tumor for a specific patient [26], [31]. |

| Model-agnostic explanation | Refers to techniques that can be applied to any model, regardless of its underlying architecture. These methods are independent of the model’s internal workings and provide insights based on the input-output behavior of the model [3], [16], [18]. | In malaria diagnostics, model-agnostic explanations may explicate which areas in blood smear images are considered relevant for the detection of infected cells, regardless of the model in use [32]. Similarly, they can be used for explainable (clinical) facial expression recognition, although they may not be sufficiently fine-grained [33]. |

| Model-specific explanation | Describes methods designed for specific types of models, such as deep neural networks. These techniques leverage the architectural characteristics and internal workings of a model to provide insights into its decision making [3], [16], [18]. | In clinical facial expression recognition, model-specific explanations may explicate what facial characteristics a model has considered relevant to predict certain states in patients such as pain [34]. Compared to model-agnostic approaches, they may provide more fine-grained explanations [33] as well as the means to generate explanations from different layers of an architecturally complex model, such as demonstrated for digital pathology [27]. |

| Example-based explanation | Summarizes methods that provide insights into a model’s decision by comparing the model’s behavior and output for a given instance with that of similar or dissimilar examples. | Several approaches fall under this category: Contrastive explanations [35], [36], prototype-based explanations [18], [37], [38], [39], [40] and case-based reasoning approaches [40], [41]. Their application in AI-driven digital healthcare is mentioned in the respective rows of Table 2. |

Part II of the overview on common XAI terminology with definitions and example use cases, primarily from digital healthcare scenarios. Part II presents explanation approaches that may cover various characteristics as introduced in Part I of the overview (see Table 1).

| Term | Definition | Example usage in digital healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Contrastive explanation | Refers to approaches which emphasize the differences between an instance of one category being explained in contrast to other similar instances from another category, showing what features in the examples led to the prediction being different [35], [36]. | In clinical facial expression recognition, a contrastive explanation could show why a patient, who cannot articulate their subjective sensation, shows a facial expression of pain (e.g., after a surgery) rather than the very similar facial expression of disgust, highlighting the key changes in the patient’s facial features influencing the model’s decision [42], [43]. |

| Prototype-based explanation | Helps in understanding which representative characteristics in the data lead to a prediction by comparing an instance to typical or prototypical cases that the model has learned [37], [38], [44], [45]. Prototypes offer an aggregated view on model decisions and provide relatable examples [18], [39], [40], [46], [47], [48]. | In clinical facial expression recognition, prototypes can be derived from clusters over sequences of similar facial expressions detected by a model [46]. They can be used to illustrate typical facial expressions of pain or of other emotional states that have led to the model’s decision [46]. Prototypes can be selected from the input data [31], [49] or generated based on identified general, representative key features important to the model [40], [42], [46]. |

| Case-based reasoning | Involves explaining a model’s decision by referring to previously seen, similar cases [40], [41], [42]. | If a patient’s mammography is predicted as possibly indicative of breast cancer, the model’s prediction can be explained by pointing to a similar historical case where the patient’s symptoms and imaging features closely matched the current case [50]. |

| Attribution-based explanation | Focuses on identifying and quantifying the contribution of each feature or input to the model’s prediction. They usually visually highlight the most influential features or inputs for improved interpretability of attributions [3], [16], [18]. | For clinical facial expression recognition based on analyzing images from video records in patient surveillance, the contribution of individual pixels to detecting real facial expressions can be made transparent. This is performed by explicating and visualizing the relevance a model has computed for all pixels in the form of heatmaps [34]. |

| Concept-based explanation | Aims for explaining model decisions by relating learned features to higher-level, human-understandable concepts or categories, rather than raw data or abstract properties [30], [51]. | In digital pathology, mapping human-understandable concepts onto attributions computed by a model, e.g., for features that represent morphological structures [12], [27], can help to explain and evaluate a model’s output in a domain-specific way [30]. |

| Rule-based explanation | Describes or approximates a model’s decision-making process through a set of logical rules. These rules often take the form of ”if-then” statements that reflect the conditions under which a model produced its output [16], [52], [53]. The goal is either to explicate individual decision steps of a model or to uncover complex, relational patterns in the data that influenced the model’s output [3], [30]. | In digital pathology, rule-based explanations can reveal, whether a model (either interpretable or opaque) has learned valid generalizations from input data. For example, for the purpose of cancer invasion depth classification, learned rules can be evaluated against established medical classification systems that define spatial relations between cancerous and other tissue types [12], [26]. In clinical facial expression recognition, rule-based explanations can add a layer of expressiveness by considering the occurrence of facial expressions and their temporal relatedness [42], [43]. |

| Probabilistic explanation | Denotes explanations that provide insights into the uncertainty or likelihood of a model’s prediction, rather than offering deterministic outputs [54], [55], [56]. | In cognitive impairment diagnostics, a bayesian network could explain the risk for developing dementia dependent of risk factors such as the age of a person or existing brain injuries [57]. Similarly, probabilistic rules could express uncertainty in tumor invasion depth computation [30]. |

Part III of the overview on common XAI terminology with definitions and example use cases, primarily from digital healthcare scenarios. Part III presents explanation approaches that usually combine characteristics and methods as introduced in Part I and Part II of the overview (see Table 1 and Table 2).

| Term | Definition | Example usage in digital healthcare |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodal explanation | Refers to approaches that integrate multiple types of information (e.g., text, visualizations, or sensor data) to provide a more comprehensive and multifaceted explanation [58]. | In digital pathology, a multimodal explanation, for example, based on verbalized rules for invasion depth and visual explanations for highlighting morphological structures, supports a more holistic understanding of a model’s decision making in experts as well as non-experts [12], [30], [31]. |

| Multiscope explanation | Combines local and global explanations [28], either as complementary units [12], [59] or by taking a glocal perspective [60], which can be achieved by aggregating local explanations [30], [46] or by leveraging local explanations that are representative on a global scale [60]. | In digital pathology, explaining the tumor invasion depth either for individual tissue samples or with respect to the overall (global) set of classification rules, provides complementary, multiscope explanations [31]. In clinical facial expression recognition, glocal explanations can be derived from clustering local explanations computed for individual facial expressions (e.g., prototypes [46]). |

| Explanatory dialogue | Refers to an interactive explanation process [49], where humans and AI engage in a conversation to receive, clarify and refine the explanations provided [21], [26], [61]. This iterative process allows the human to ask follow-up questions or request further details, making the explanation more comprehensive and tailored to the explainee’s information need [12], [61], [62]. Explanatory dialogues may benefit from integrating multimodal, multiscope and different example-based explanations [12], [61]. | In digital pathology, a medical expert or non-expert can engage in an explanatory dialogue with a model through an integrative explanation interface, for example, to learn about a model’s tumor invasion depth classification outcomes [12], [31]. The explainee may ask for a global explanation about the model’s overall classification or for a local explanation to explicate the reasons behind the invasion depth classification for a specific tissue sample. The explainee may also request more detailed explanations (e.g., by navigating logic proofs for the model’s reasoning steps [31], [49]). These may be complemented by example-based explanations such as prototypical tissue samples [31]. Medical experts as well as non-experts can guide the explanation process and may thus achieve a better understanding of and trust in the model [12], [31], [49]. |

| Corrective feedback | Refers to a change initiated and performed by the explainee in order to adapt a model, an explanation or the input itself (with the goal to correct and possibly improve the model) [63]. Corrective feedback enables explanatory interactive machine learning [64]. | In digital pathology, balanced annotated data is often unavailable, may be noisy, sparse or prone to limited reliability as well as validity [12], [65], [66] leading to false model outcomes. For example, in invasion depth classification, corrective feedback can help to adapt a model by introducing constraints in subsequent model updates and may uncover noisy example to be re-labeled [12], [26]. |

The aim of all these explanation methods is to provide the human explainee with a tool to explore AI models and have them explained in order to increase understanding of the model and its decisions. Another goal is to make transparent how models can be adapted and possibly improved in terms of performance, interpretability and robustness. However, providing explanations is not enough for model evaluation. Models should be scrutinized using XAI-based evaluation methods.

2.2 XAI-based model evaluation methods

XAI-based model evaluation can be performed based on methods and techniques that assess the efficiency, effectiveness, reliability, and trustworthiness of explanations generated for given models [3], [67], [68]. The goal is to ensure that the explanations provided for AI models are not only understandable but also meaningful and aligned with human expectations and technical requirements [12], [16], [68], [69]. In the following paragraphs, a selection of methods is introduced that support human-centered evaluation as well as the assessment of a model’s robustness.

2.2.1 Human study

The term human study is an umbrella term for all studies that involve a human person, being either an evaluator or interaction partner. Human studies aim for gaining evidence for the quality of and trust in models and explanations [67], [69], [70]. They may include expert interviews and questionnaires [69] as well as controlled and randomized experiments with experts and end-users [66], [67], [71]. The overall goal is to measure how explanations are perceived, understood and used by explainees [12], [71]. Surprisingly, although the human plays a crucial role in evaluating the quality of XAI methods, a recent review by Suh et al. [72] revealed that less than 1 % of works from a surveyed collection of 8254 XAI papers validate explainability with the help of human studies.

2.2.2 Evaluation metrics

In the aforementioned human studies as well as in technical experiments, metrics help to measure the quality of the model, the explanations and the interaction within a human-AI system. Doshi-Velez and Kim [73] distinguish three categories of metrics based on the level of human involvement and technical or application maturity. They refer to functionally-grounded metrics, when a human judgment is not involved, to human-grounded metrics, when subjective judgments, alignment with human knowledge, or human behavioral patterns are measured), and to application-grounded metrics, when a model and explanations are evaluated against application-specific requirements or when the performance or the full human-AI-system is evaluated in a real-world setting [16]. Examples for functionally grounded metrics are fidelity, compactness or stability of an explanation [68]. Typical human-grounded metrics are the degree of alignment with human knowledge (e.g., the match between the content of an explanation and human expert knowledge [38], [74]) and the degree of understanding usually measured by a proxy task to be solved by the human [12], [16]. Application-grounded metrics may be criteria such as the end-user satisfaction, costs and performance of human-AI systems [16], [68].

2.2.3 Data augmentation and adversarial attacks

These techniques involve modifying the input data to test how the model and its explanations behave under various conditions. Data augmentation introduces slight variations in the input data, while adversarial attacks generate subtle but intentional perturbations to test the model’s and the explanations’ robustness [68]. The evaluation focuses on whether the model’s predictions and explanations improve [42] or remain consistent and robust despite these changes [75].

2.2.4 Constrained loss functions

This approach modifies the training process of a model by incorporating constraints into the loss function to regularize the model toward generating more general, accurate or explainable outcomes [64], [76]. For example, a constrained loss function can penalize the model for making decisions that do not adhere to feature or class correlations present in the given ground truth. Correlation losses may thus improve the model’s performance and resulting explanations, whenever they are based on valid expert knowledge [12], [77].

2.2.5 Constrained feature extraction

In this approach, the model is designed to only extract features that satisfy given constraints and are considered important for the model’s decision-making process [26], [64]. After guiding the model toward these key features during the training process, the evaluation step measures whether the model performs well in comparison to the unconstrained predecessor and whether generated explanations highlight the most relevant and interpretable features, accordingly [26], [30].

2.2.6 Concept suppression and ablation studies

These methods involve systematically removing or “suppressing” certain features, concepts or architectural components in the model to evaluate how each of them contributes to the model’s decision-making process [58]. Ablation studies help identify which relevant building blocks most influenced the model’s predictions [58] and whether the explanations refer to these important factors [30]. Suppressing irrelevant features or concepts can be considered constrained feature extraction as described above. Gradual or repeated applications of such techniques can help to assess the robustness of the model or explanations.

2.3 How XAI is contributing to trustworthy AI

To summarize the previous paragraphs, XAI methods encompass the aspects of trustworthy AI, namely interpretability, explainability, interactivity, and robustness, by leveraging a diverse range of techniques. Interpretability is given under the use of inherently interpretable models. Explainability is supported by explanations of varying scope (local to global), model-specificity (agnostic or specific), modality, complexity (attribution-based, concept-based or relational information), determinism (probabilistic or not), with different kinds of example-based explanations available. Interaction is covered through different interaction modes (explanatory dialogues and corrective feedback) and robustness can be assessed through specific evaluation and improvement techniques (mostly based on constraints imposed on the model and adaptions to the input data).

Fusing these aspects and complementary XAI methods is the goal of integrative XAI frameworks, which will be introduced subsequently.

3 Integrative XAI frameworks

The following subsections shortly introduce the concept and constituents of integrative XAI frameworks in advance to describing an actual implementation.

3.1 Definition

Integrative XAI frameworks combine multiple XAI techniques to provide a holistic understanding and evaluation of AI models. They aim to improve the trustworthiness of AI by leveraging a broad spectrum of complementary explanation methods and XAI-based evaluation techniques while aiming for human-centeredness and possibly the combination of symbolic and subsymbolic AI methods for complex models and knowledge domains [12], [59], [62], [78]. Their constituents provide interpretability, explainability, interactivity as well as robustness by integrating methods and evaluation procedures with characteristics that support these aspects.

3.2 Constituents

An integrative XAI framework cannot be based on a single XAI method. It benefits most from a combination of techniques that complement each other rather than introducing redundancy for the sake of comprehensiveness in exchange of expressiveness and interoperability. The constituents are therefore chosen such that they each address the distinct technical and cognitive trustworthy AI aspects.

3.2.1 Interpretable base model and Ad-hoc explanation generation

This constituent trains or applies an inherently interpretable model on given data to provide explanations generated directly from the model’s reasoning process. It is considered as a base model as long as it is applied directly on the given data.

3.2.2 Opaque base model and post-hoc explanation

This constituent trains or applies an opaque and possibly complex model, such as a deep neural network, on given data. Explainability can only be achieved by combining it with an explainer that provides post-hoc explanations for predictions of the model on the given data.

3.2.3 Opaque base model and interpretable surrogate model

An opaque base model can be approximated using an interpretable surrogate approach to explanation. The interpretable surrogate model is not applied to the original data. The inputs it gets stem from the opaque base model’s internals or post-hoc explainer outputs that serve as intermediate representations suitable to be processed and integrated into subsequent explanations by the chosen interpretable surrogate model. Intermediate representations may be derived from attributions, human-understandable concepts, relational information and possibly probabilities.

3.2.4 Example-based explanation

Example-based explanation supports explainability through the comparison of representative examples, that illustrate model behavior, with examples the predictive behavior was exhibited on. These methods can include contrastive explanations, prototype-based explanations as well as explanations derived from case-based reasoning as constituents of a framework. By presenting concrete instances rather than abstract reasoning processes and outputs, example-based explanations relate a model’s predictive behavior to real-world features.

3.2.5 Unimodal and multimodal explanation

Unimodal explanation as a constituent focuses on a single modality, whereas multimodal explanation provides multifaceted insights into a model’s decision-making process and outputs by utilizing various modalities. Combining unimodal as well as multimodal explanation approaches as framework constituents offers the possibility to tailor the explanation generation to varying information needs of human recipients.

3.2.6 Corrective feedback and constraints

Corrective feedback and constraints as constituents provide the means to the base model’s as well as surrogate model’s evaluation. They can serve as tools for model improvement, explanation adaption as well as user feedback. They may target input data, model parameters, predictive features as well as explanations.

3.2.7 Explanatory dialogue

The explanatory dialogue serves as a crucial constituent in integrative XAI frameworks enabling human users to engage in interactive conversations with AI models. It supports inquiries about different explanations, revision of explanations as well as providing feedback and corrections, such as constraints, to the model.

4 Implementation of integrative XAI frameworks

As motivated earlier, critical applications that require trustworthy AI could benefit from the implementation of more integrative XAI frameworks. Example applications include digital healthcare [66], [79], [80] and service robotics for object recognition and object manipulation in care centers [81], both illustrated in Figure 2.

![Figure 2:

Applications in complex knowledge domains such as digital healthcare and service robotics can benefit from integrative XAI frameworks. Local (possibly concept-based) explanations can help to validate a models output (e.g., the correct recognition of mucosa tissue [27], of a facial action like brow raisers [46], and of object parts like handles and spouts on teapots [30]). Rule-based global explanations can put these concepts into context (if a small mucosa region is surrounded by tumor tissue, it is probably part of the cancerous area and should add to it in quantity [12], [27]). Contrastive explanations can contribute to distinguishing similar cases (e.g., a handle and a spout can be present both in teapots and vases, however, more often the spout is right of the handle in teapots oriented to the right compared to vases [30]). Prototypes can help to find or generate representative instances that allow for information aggregation and comparison based on typical characteristics (e.g., raising the brows and parting the lips is a process in facial expression that is typical for surprise and temporal prototypes can explicate this change, for example, visually with aggregated attributions [46]). The combination of multiscope (global and local) explanations as well as multiple modalities (e.g., visualizations and verbal explanations) within a human-AI dialogue allows for bi-directional, more expressive and comprehensible interaction in these application areas [12], [31], [49].](/document/doi/10.1515/itit-2025-0007/asset/graphic/j_itit-2025-0007_fig_002.jpg)

Applications in complex knowledge domains such as digital healthcare and service robotics can benefit from integrative XAI frameworks. Local (possibly concept-based) explanations can help to validate a models output (e.g., the correct recognition of mucosa tissue [27], of a facial action like brow raisers [46], and of object parts like handles and spouts on teapots [30]). Rule-based global explanations can put these concepts into context (if a small mucosa region is surrounded by tumor tissue, it is probably part of the cancerous area and should add to it in quantity [12], [27]). Contrastive explanations can contribute to distinguishing similar cases (e.g., a handle and a spout can be present both in teapots and vases, however, more often the spout is right of the handle in teapots oriented to the right compared to vases [30]). Prototypes can help to find or generate representative instances that allow for information aggregation and comparison based on typical characteristics (e.g., raising the brows and parting the lips is a process in facial expression that is typical for surprise and temporal prototypes can explicate this change, for example, visually with aggregated attributions [46]). The combination of multiscope (global and local) explanations as well as multiple modalities (e.g., visualizations and verbal explanations) within a human-AI dialogue allows for bi-directional, more expressive and comprehensible interaction in these application areas [12], [31], [49].

![Figure 3:

Part I of the architectural overview for the proposed integrative XAI framework. Path A: Combination of an opaque base model, such as a neural network, support vector machine or other non-linear model with a post-hoc explanation method such as relevance propagation, probabilistic models, or clustering among others. Path B: Combining an opaque base model with an interpretable surrogate model, such as a decision tree, inductive logic programming or other rule-based models. Also path B: Providing an interpretable base model. Path C: Enhancing path B by computation of probabilities for concepts, their occurrences as well as relations in interpretable models. Illustrated for the teapot versus vase classification problem adapted from Finzel et al. [30], where attributions may be translated by a human or automated agent into concepts like “lid” (c1) and “flower” (c2) and where relations may be computed by an expressive interpretable model. Such relations may express spatial constellations like “the lid is on top of the pot” as a means to characterize a teapot in contrast to a vase. Probabilistic methods may account for heterogeneity in objects of a target class that may share characteristics with objects in the contrastive class (e.g., a teapot may not have a lid, which also holds for a vase). The combination of different constituents is denoted by a logic or (∨) and reasoning that takes place in constituents of the framework is expressed by implication (←) and logical entailment (⊧) as well as logical connectives (∧, ∨). Relations are denoted by upper case R indexed to distinguish different relations in logical expressions. Similarly, concepts are denoted by lower case c indexed to distinguish different concepts in logical expressions. Probabilities are expressed by the parameter θ.](/document/doi/10.1515/itit-2025-0007/asset/graphic/j_itit-2025-0007_fig_003.jpg)

Part I of the architectural overview for the proposed integrative XAI framework. Path A: Combination of an opaque base model, such as a neural network, support vector machine or other non-linear model with a post-hoc explanation method such as relevance propagation, probabilistic models, or clustering among others. Path B: Combining an opaque base model with an interpretable surrogate model, such as a decision tree, inductive logic programming or other rule-based models. Also path B: Providing an interpretable base model. Path C: Enhancing path B by computation of probabilities for concepts, their occurrences as well as relations in interpretable models. Illustrated for the teapot versus vase classification problem adapted from Finzel et al. [30], where attributions may be translated by a human or automated agent into concepts like “lid” (c1) and “flower” (c2) and where relations may be computed by an expressive interpretable model. Such relations may express spatial constellations like “the lid is on top of the pot” as a means to characterize a teapot in contrast to a vase. Probabilistic methods may account for heterogeneity in objects of a target class that may share characteristics with objects in the contrastive class (e.g., a teapot may not have a lid, which also holds for a vase). The combination of different constituents is denoted by a logic or (∨) and reasoning that takes place in constituents of the framework is expressed by implication (←) and logical entailment (⊧) as well as logical connectives (∧, ∨). Relations are denoted by upper case R indexed to distinguish different relations in logical expressions. Similarly, concepts are denoted by lower case c indexed to distinguish different concepts in logical expressions. Probabilities are expressed by the parameter θ.

These applications have in common that models need to undergo rigorous evaluation in advance to deployment and that the data used to train and test models may stem from a complex knowledge domain [82]. In complex knowledge domains, data is highly interrelated, meaning that knowledge is not expressed by individual, independent concepts but rather through manifold relationships between concepts [82]. Models trained on tasks such as tumor classification based on spatial tissue relations, pain assessment based on dynamic facial expressions, object classification based on composed object parts and context understanding from possibly ambiguous real-world scenarios, require expressive explanatory and evaluation approaches. In tumor classification, healthy tissue invaded and surrounded by cancerous tissue may be considered as part of the tumor, while still resembling normal healthy tissue [83]. Without consideration of spatial relations, like containment and proximity (healthy tissue mixed up with cancerous tissue) such classification would be limited [27]. In pain assessment, distinguishing similar individual facial expressions based on temporal sequences of certain muscle movements may be the key to separability compared to mere consideration of occurrences of expressions [43], [46]. In object classification performed, for example, by a service robot, expressing spatial relations between concepts can provide the means for distinguishing similar object classes. For example, teapots and vases can be considered similar objects from a cognitive perspective [84]. The occurrence of flowers in the presence of a bowl shaped vessel may not be sufficient to distinguish a vase from a teapot. It may make a difference, whether the flowers are located as ornaments on a teapot’s vessel or placed inside a vase [30]. Similarly, for teapots oriented to the right it usually holds that the majority of cases has a handle right of the spout compared to vases that may also have a handle and a spout, however, in different spatial constellation [30]. The characteristics of instances from different subgroups can be compared to instances from contrastive classes [30], [42], [43]. They also can be aggregated in the form of prototypical, concept-based and rule-based (relational) explanations for increased usefulness and comprehensibility of model decisions [30], [46]. Integrating uncertainty, e.g., in the form of probabilities, can provide the means to more nuanced and realistic explanations [30], [85].

This is especially important for the assessment of risks resulting from the usage of an AI system. The consequences of mistakes such as false diagnostic decisions or incorrect object manipulations (imagine a service robot bringing the vase instead of the teapot to fill a cup) could be fatal [8]. Although, no AI system is allowed to make critical decisions on behalf of humans [1], a holistic approach to evaluation is needed to avoid, for example, human confirmation bias [12], [29], [66] and biased models or “Clever Hans” learning [86], [87] interfering with trustworthiness. Expressive explanations and rigorous evaluation as intended by the design of integrative XAI frameworks can act as countermeasures.

4.1 Architectural overview

Figure 3 presents part I of the architectural overview, focusing on different types of models and explainers in integrative XAI frameworks. The architecture proposes three different integration paths. Path A illustrates the approach of combining an opaque base model with a post-hoc explainer, e.g., an attribution-based explanation method that highlights features relevant to a model’s predictive behavior (red if representative for a class, blue otherwise). Path B illustrates the approach of using either an interpretable base model or by combining an opaque base model with an interpretable surrogate model, e.g., a rule-based method capable to express relational information. In addition, path C illustrates an approach that complements explainability and interpretability by expressing probabilities for the occurrence of concepts and consequently relations computed based on top of extracted concepts.

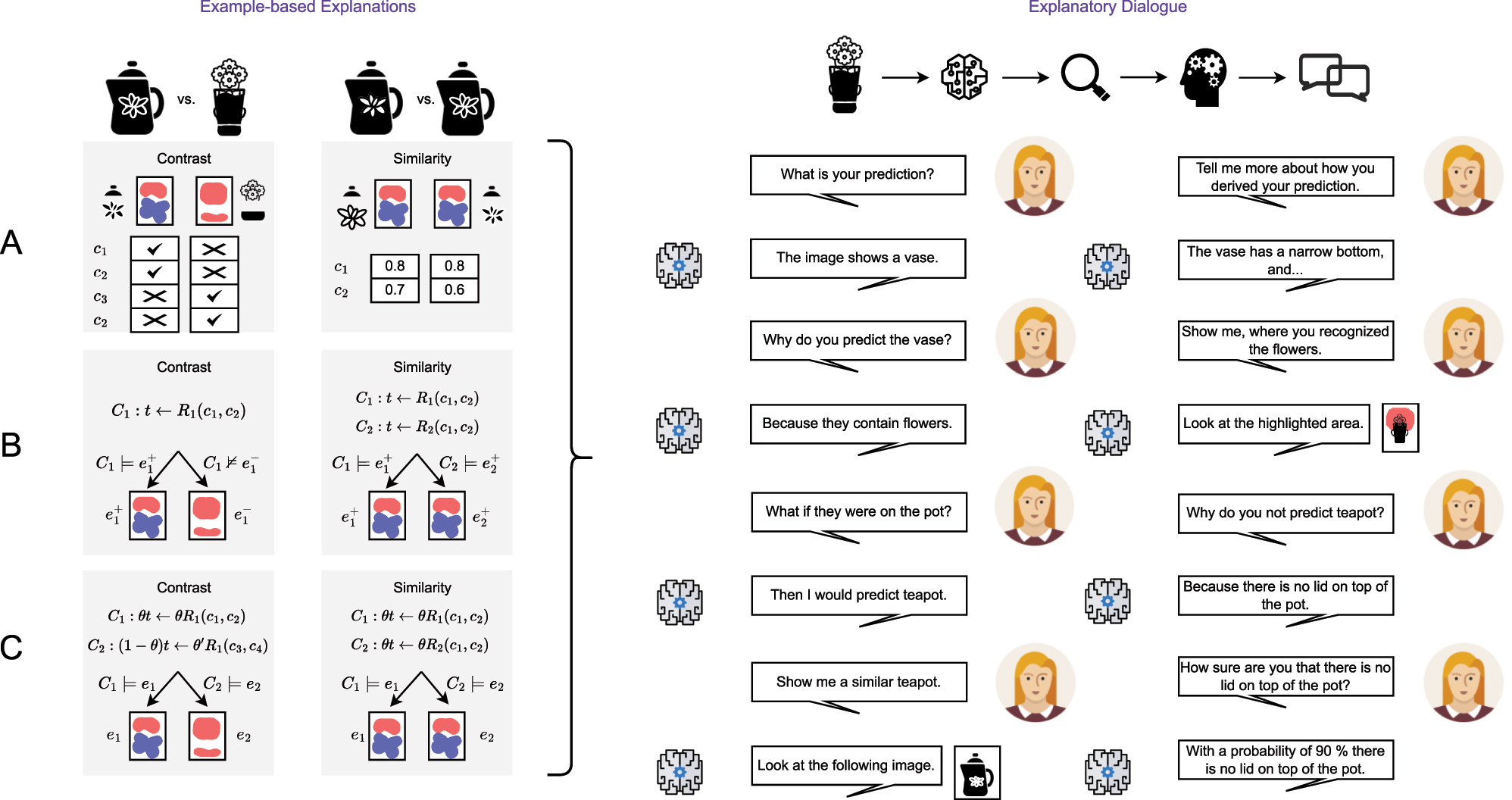

Figure 4 presents part II of the architectural overview. On the left, it is illustrating example-based explanations, in particular contrastive and similarity-based explanations, for all proposed integration paths as introduced in Figure 3. On the right, it is illustrating an explanatory dialogue that provides explainability, interpretability as well as interaction in the form of a conversation between the AI system and a human.

Part II of the architectural overview for the proposed integrative XAI framework. All three proposed integration paths from Figure 3 can be enhanced by example-based explanations (left side) and explanatory dialogues (right side) build on top. Contrastive explanations may primarily serve the comparison of different instances (e.g., teapots and vases in object classification tasks). Constrasts can be generated based on attributions (red if representative for a class, blue otherwise), concepts extracted from attributions and rules generated on top of concepts. Likewise, similarity-based explanations, e.g., prototype-based explanations, can be generated based on attributions, concepts and relations present in similar instances (e.g., two teapots and with similar features). Reasoning that takes place in constituents of the framework is expressed by implication (←) and logical entailment (⊧). In the logical expressions, instances from different classes are denoted as e+ and e−, whereas instances from same classes are both denoted as e+. Probabilities are expressed by the parameter θ. Relations are denoted by upper case R indexed to distinguish different relations in logical expressions. Similarly, concepts are denoted by lower case c indexed to distinguish different concepts in logical expressions. Logic rules are denoted by upper case C indexed to distinguish alternative rules. The dialogue is built on top of the pipeline (instances are classified by a model, the model’s predictive behavior gets explained and prepared for being interpreted by a human, who is then involved in conversation with an explanation interface built on top of the AI system). The conversational interaction includes inquiries about the prediction (What), requests for reasons behind a prediction (Why) and the reasoning leading to that prediction (How) as well as requests for example-based explanations (prototype-based, contrastive). The explanatory dialogue provides verbal interaction as well as pictorial illustrations showing instances and attributions of concepts upon request (multimodal explanations). In principle, such an explanatory dialogue can provide global as well as local insights for model-specific as well as model-agnostic explainers, making it a focal point of integrative XAI frameworks.

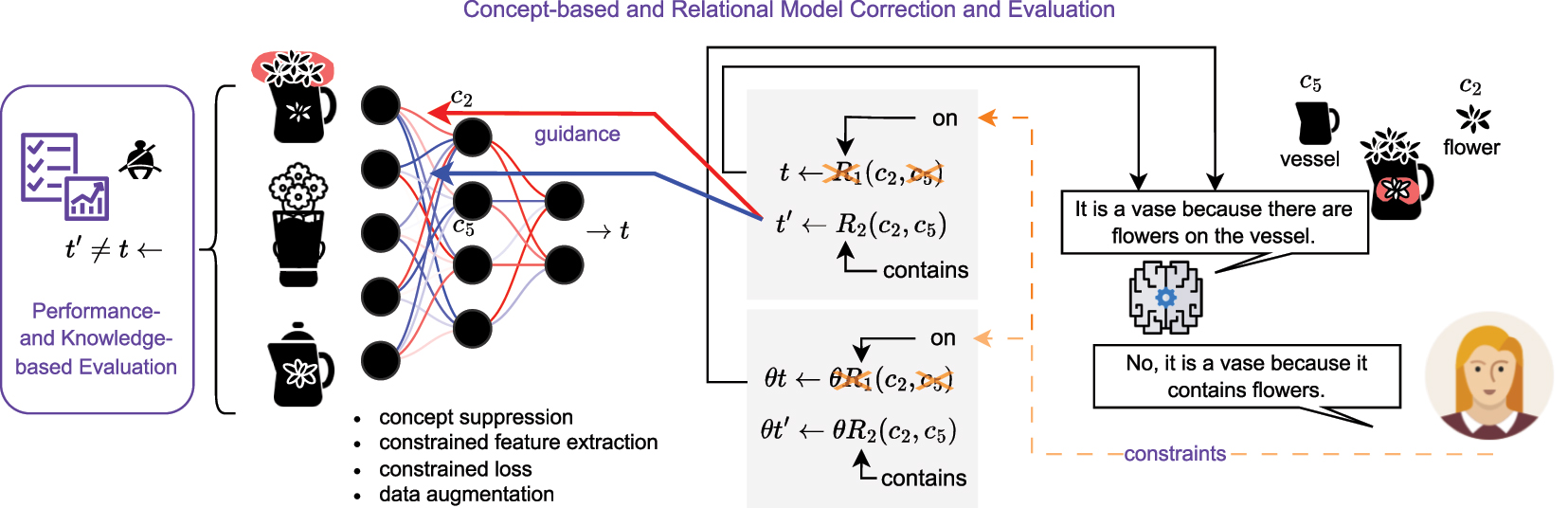

Figure 5 presents part III of the architectural overview. It primarily illustrates the aspects of evaluation and human control inside integrative XAI frameworks denoted as concept-based and relational model correction and evaluation here.

Part III of the architectural overview for the proposed integrative XAI framework. The explanatory dialogue can be enhanced by constrained-based correction and evaluation of concepts and relations utilized by the AI model in its decision-making process or as generated by integrated explainers. The AI model may base its decision (e.g., the classification of an object as a vase) on wrong reasons (e.g., it considers flowers painted on the vessel as relevant to the target class). The human may provide corrective feedback to change the model’s reasons for a decision (e.g., by stating that the spatial relation of flowers being contained by the vessel is the relevant information that has to be considered by the model). This feedback may be translated into constraints or augmentation measures to improve the model and its outcomes (here, the correction is transformed into logic constraints, which are propagated through an interpretable surrogate model that adapts it decision first, before providing guidance to the underlying opaque base model). The opaque base mode (e.g., a neural network) may receive the guidance as a form of concept suppression, constrained feature extraction, constrained loss or may be enhanced through data augmentation. The ultimate goal of this process is, to adapt the model’s decision process and output t, such that a new version t′ results from provided human feedback. This may result in reclassification of instances (e.g., the vase is now recognized as a teapot) or a different attribution of concepts (e.g., the flowers inside the vase are more relevant than the flowers painted on the vase’s vessel). This performance- and knowledge-based evaluation may result in more robust AI systems by mitigating false and inconsistent model decisions. It thus contributes to another important aspect of trustworthy AI complementing the explanatory dialogue as introduced in part II of the integrative XAI framework. Note that reasoning that takes place in constituents of the framework is expressed by implication (←) here. Probabilities are expressed by the parameter θ. Relations are denoted by upper case R indexed to distinguish different relations in logical expressions. Similarly, concepts are denoted by lower case c indexed to distinguish different concepts in logical expressions.

As mentioned before, model quality may be harmed by bias, leading to mistakes in predictive outcomes. In classification tasks, this may include misclassification of examples or classifications for the wrong reasons (false concepts, false relations and false probabilities in particular, leading to false explanations [88]). The human decision-maker (usually a domain expert, for example, a doctor) may introduce constraints in the opaque base model, possibly through the interface and integration of an interpretable surrogate model. As introduced earlier, such corrective feedback may include countermeasures like concept suppression in ablation studies, constrained feature extraction, constraining the loss(es) of involved model(s) as well as broadening the feature basis through data augmentation. In general, corrective feedback in the form of constraints provides guidance to the base model by weakening undesired and strengthening desired concepts and relations. Consequently, guidance provides the means to explore and change model decisions and explanations [89], [90]. Spanning the evaluation over opaque base models integrated with post-hoc explainers and interpretable surrogate models, extends performance-based evaluation by knowledge-based evaluation.

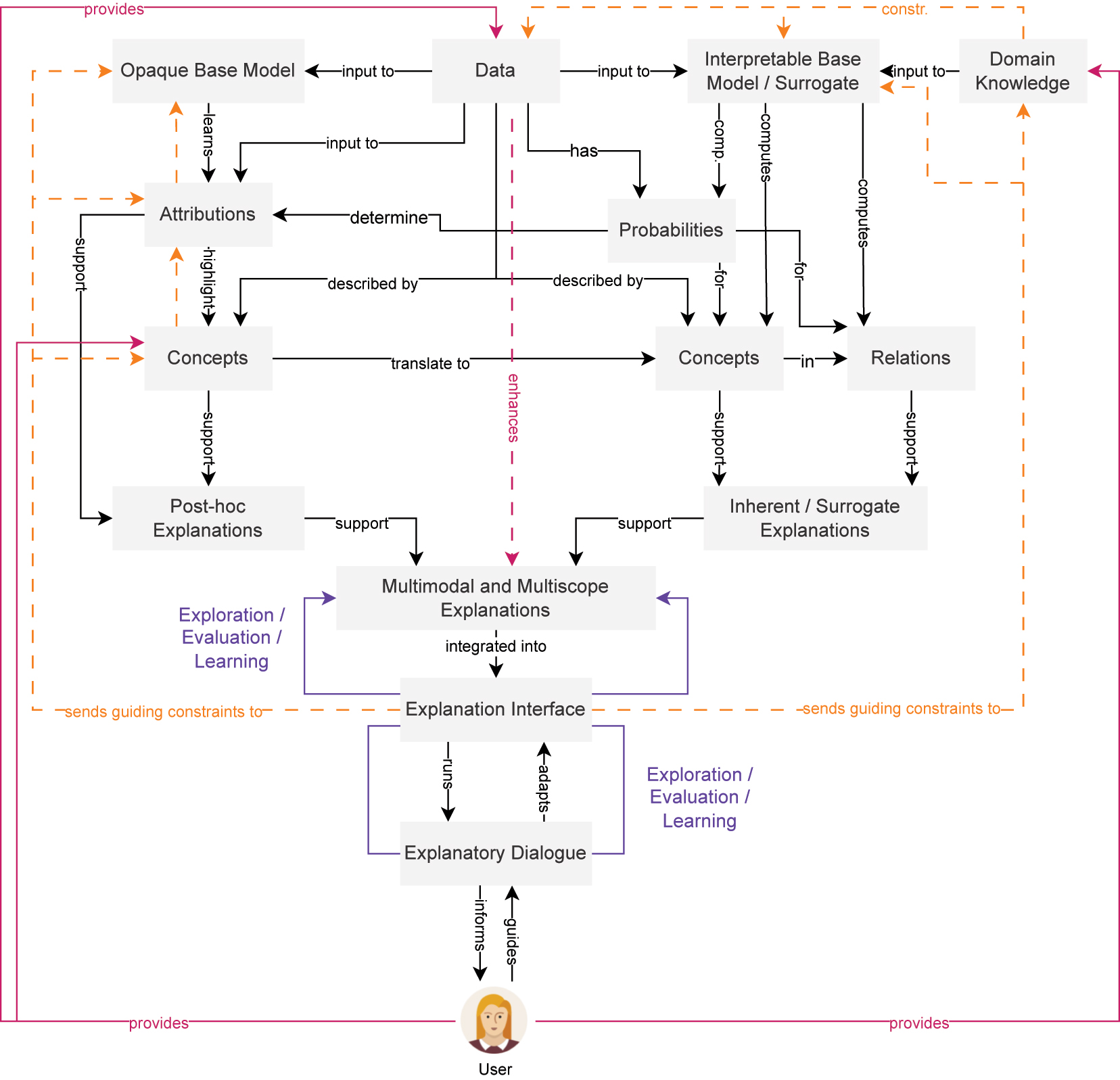

An overall illustration of the information flow between the human user and the AI system as well as within the integrative XAI framework is provided in Figure 6. Emphasis is put on the aspect that the human can explore, evaluate and may even learn from model decisions. This may be especially supported by multimodal and multiscope explanations gathered from post-hoc explanations and inherent or surrogate explanations [30], [71]. The human is furthermore empowered to provide constraints in the form of domain knowledge to the interpretable base or surrogate model and in the form of various constraints and augmentations, as introduced earlier, to adapt the opaque base model, its attributions and concepts, respectively. The information flow also illustrates the role of data as input to the model, to attribution computation and visualization and as a basis for probability computation that determines attribution and that serves as a basis for expressing the likelihood of concepts and relations in interpretable models. The information flow also illustrates that integrative XAI frameworks provide the means to inject human knowledge at different parts of the process (in the form of concepts, domain knowledge or data).

An overview of the information flow in the proposed integrative XAI framework, connecting the human with the AI system via an explanation interface that provides an explanatory dialogue and the means for constraint-based model correction and evaluation.

4.2 Methods

Individual building blocks of the proposed integrative XAI framework have already been implemented for realistic and real-world data. The realization has partially taken place within two related research projects, the Transparent Medical Expert Companion and the PainFaceReader as introduced by Schmid & Finzel [26] and reported by Finzel [12]. Experiments and evaluations have been conducted in collaboration with different research groups and medical institutes. Tissue samples for the use case of digital pathology were collected and curated at the University Hospital Erlangen (collaboration with Dr. med. Carol Geppert, Dr. med. Markus Eckstein, and Prof. Dr. Arndt Hartmann, institute of pathology) and partially analyzed at Fraunhofer IIS with the help of deep learning models (in collaboration with Dr. Volker Bruns, Dr. Michaela Benz, research group for medical image analysis). Explanatory approaches, opaque base models and interpretable models were developed and applied at the University of Bamberg (the author of this article under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Ute Schmid, chair of Cognitive Systems). Records for clinical facial expression recognition were provided by Prof. Dr. Stefan Lautenbacher (chair of Physiological Psychology at the University of Bamberg) and Prof. Dr. Miriam Kunz (chair of Medical Psychology and Sociology at the University of Augsburg). Explanatory approaches for facial expression recognition were developed and applied in collaboration with Fraunhofer IIS (Jens Garbas, Smart Sensing and Electronics). Outside of the scope of the two research projects, benchmarks for (human) concept learning were reviewed and tested in collaboration with BOKU University (Prof. Dr. Andreas Holzinger, head of HCAI Lab).[2]

In this article, the underlying XAI framework is developed, conceptualized, extended and described as part of a dissertation by the first author of this work. The methods characterized in the following paragraphs have been combined to realize individual constituents of the proposed framework and to answer related research questions. Detailed results can be found in the referenced works.

4.2.1 Inductive logic programming (ILP) for inherent and surrogate explanation

ILP is a machine learning approach that generates inherently interpretable models from input examples using symbolic first-order-logic expressions [13], [93], [94], [95]. Due to its expressiveness and safety properties [96] it is well-suited for learning and explaining models in complex knowledge domains. ILP’s inherent interpretability stems not only from its declarative programming paradigm but also from the fact that input examples, background knowledge describing them, learned theories (rules) and ILP algorithms are altogether based on first-order logic [24], [26], [93], [94]. This integrative nature supports comprehensibility as demonstrated in human studies [13], [30] and allows for traceable and verifiable reasoning [49], [96].

Critical decision scenarios requiring high interpretability, such as medicine [13], [24], may benefit from this property. For example, in digital pathology, ILP can clarify the conditions under which certain tissue structures are classified, using relational rules that are easy for domain experts to verify [12], [26] and easy to understand by non-experts [12], [13], [71].

Although the birth year of ILP dates back to 1991, interest in the formal properties and interpretability of this approach has not waned. In the course of research into neuro-symbolic AI and explainability, it is enjoying renewed popularity [93], [97], [98]. State-of-the-art implementations provide libraries and extensions in other programming languages such as Python [30], [99], [100]. This makes it easy to couple ILP with neural networks [26], [30], [100], [101].

In an integrative XAI framework, ILP can serve as an interpretable base model or as a surrogate model to opaque base models. The surrogate model can either be used to imitate and approximate the base model’s behavior [102] or to analyze an opaque base model’s output from the perspective of conceptual and relational information with the purpose of data and domain-specific explainability [3], [24], [26], [30], [101].

This approach provides both local and global explanations and can be integrated with other techniques, such as multimodal explanations, example-based explanations and explanatory dialogues [30], [31], [42], [49] and constraints to refine model behavior [26], [30], [42]. For example, in digital pathology, experts can use constraints to help the model distinguish between closely related tissue types more accurately, especially when the data contains noise. Such constraints can improve model performance but require some form of quality control to avoid biases in adaptation [26].

It is further suitable for generating either deterministic or probabilistic concept-based as well as relation-based explanations [30]. ILP is available in different variants, for example, as probabilistic ILP [101], [103], [104] as well as in frameworks providing abductive reasoning for explanation besides induction [105]. It further supports constraint-based corrective feedback [26], [105]. ILP is therefore a suitable method to cover many important aspects of integrative XAI frameworks, provided that input data is available in corresponding logical representations.

4.2.2 Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) as opaque base models

Computer vision and image classification in particular, are important areas of research in digital healthcare due to the growing amount of image data as a foundation to visual diagnostics [12]. The proposed integrative XAI framework was therefore mainly tested for image classification (for opaque base models) and related use cases (for interpretable models).

CNNs are a type of artificial neural network designed for deep learning-based image classification tasks (computer vision). They learn in a multi-layered fashion due to their architecture consisting of a backbone with multiple subsequent convolutional layers combined with an additional classification head. Each layer in the backbone provides a collection of convolutional filters. These filters perform abstraction on the input to derive features of various complexity and expressiveness (ranging from simple concepts like dots or lines to rather complex shapes like cell structures). These features are assigned more or less relevance during a training procedure using learnable weights and activation functions. The occurrence of features and their relevance ultimately determines the classification of an input image in the end. The foundations of Convolutional Neural Networks were introduced by LeCun et al. [106].

In an integrative XAI framework, a CNN takes the role of the opaque base model due to its model complexity. It is suitable for end-to-end learning (requiring no or less feature engineering compared to traditional machine learning approaches, while showing high classification performances) and has excelled in many computer vision tasks, including the digital healthcare use cases, presented in this work. Still, as outlined earlier, there remains a need for explainability to trust in the models outputs for the right reasons.

4.2.3 Gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) for local post-hoc explanations

Grad-CAM computes and visualizes which image areas have been considered important in an classification task by a CNN. Grad-CAM generates class-specific activation maps by computing the gradient of the target class score with respect to a CNN’s feature maps derived from convolution filter operations. These gradients indicate pixel-wise contributions to the class score. Spatially averaging the gradients yields weights, which are used to linearly combine feature maps and to produce the final activation map (a heatmap) for the respective target class [107].

In an integrative XAI framework, Grad-CAM can provide local, attribution-based, post-hoc explanations for opaque base model CNNs. While Grad-CAM is only applicable to CNNs (model-specific), its advantage is that it provides class-specific visual explanations (expressing positive relevance) across different convolutional layers of a CNN. Furthermore, the activation information can be aggregated across individual layers of a CNN, to derive the most influencial layers for a specific classification task such as tissue classification [27]. This allows for an approximate, layer-wise relevance analysis with class-specific importance scores. Grad-CAM can be combined with ILP [100] to realize a neuro-symbolic system. A concept-based variant of Grad-CAM uses pooled concept activation vector values as weights instead of the globally averaged gradients to produce human-understandable explanations [108].

In pathology, visual explanations generated with Grad-CAM can be evaluated by pathologists to see how different model layers see relevant morphological structures in tissue classification [27]. By showing experts which tissue areas in the image are most influential for the model’s decision, Grad-CAM helps practitioners better understand the significance of various tissue structures in the model’s classification and to evaluate its correctness, accordingly [27].

4.2.4 Relevance propagation for local and concept-based post-hoc explanations

In general, relevance propagation methods assign relevance scores to input features (e.g., individual pixels) by propagating a model’s prediction backward through its layers, following structured redistribution rules. These relevance scores, visualized as heatmaps, quantify each feature’s contribution to the output. The most prominent method to date is Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) [109]. Its advantage is that it conserves total relevance across layers to ensure faithful attribution. It distinguishes positive relevance (supporting the target output) from negative relevance (contradicting it). Being model-specific, LRP directly leverages the network’s structure and parameters, enhancing fidelity but reducing flexibility compared to model-agnostic methods. A concept-level extension to LRP, called Concept Relevance Propagation (CRP), allows for the approximation of human-understandable concepts in learned features [110], [111].

In integrative XAI frameworks relevance propagation can serve as a local, attribution-based, post-hoc explanation technique for opaque base models and is applicable to a large variety of tasks (rather model-specific for non-linear learning approaches like deep learning; not limited to CNNs). Similar to Grad-CAM it allows for a multi-layer insight into a model’s learned representations. Its concept-based variant CRP, that tests for semantic, human-understandable concepts, has been combined with ILP in a recent work to realize a neuro-symbolic approach to concept-based and relational explanation [30]. A human study with experts supports the findings that the combined, multimodal explanations are superior in usefulness in comparison to unimodal explanations (heatmaps or rules) for the complex knowledge domain of ornithology [30].

4.2.5 t-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) for global post-hoc explanations

The method t-SNE provides visualizations for a set of high-dimensional data points, by mapping them into a 2D or 3D space that preserves local neighborhoods (pairwise similarities in the data), meaning that points that are close in the high-dimensional space tend to remain close in the lower-dimensional representation [112]. It was introduced by van der Maaten and Hinton [112]. t-SNE can be used to derive more global explanations by aggregating local explanations such as done by the Spectral Relevance Analysis (SpRAy) technique. SpRAy identifies overall patterns in a model’s attributions by clustering relevance maps.

In integrative XAI frameworks t-SNE and SpRAy can be used to detect potentially misleading “Clever Hans” effects [113] in models. Furthermore t-SNE applied to local explanations serves the purpose of aggregating information and reducing the information load for human explainees [12]. For example, in facial expression classification, clustering attributions with the help of t-SNE can reveal that a model has learned certain subgroups of expressions that are representative of a certain emotion. This way, prototypes can be derived as introduced earlier [46]. t-SNE may also help to identify small clusters (potentially anomalies or samples underrepresented in the data). This is especially of interest, if the model may be heavily weighting random, irrelevant image features that do not correlate with actual facial expressions (such as the background) [12], [46].

4.3 Explanatory approaches

4.3.1 Contrastive explanations as an example-based approach

This approach compares similar instances with distinct classifications to clarify boundaries between categories, usually based on minimal differences [42], [114].

The implemented integrative XAI framework leveraged contrastive explanations, for example, in distinguishing facial expressions of pain and disgust, using both attribute-based and relational near-miss and far-miss examples for explaining an ILP model’s decision [43]. Near misses are instances that are most similar to an example that is to be explained, but belong to the opposite class [114]. Far misses are the most dissimilar contrastive examples. The underlying explanation is based on a request like “Why is this pain and not disgust?” (see also the request presented in Figure 4).

Experimental results showed that contrastive explanations were generally shorter than exhaustive ones for all experimental settings, focusing only on the most critical distinguishing features [43]. This supports interpretability and improves efficiency, making them particularly useful in classification tasks with subtle differences. The experimental evaluation further highlighted the role of near misses, which shared many similarities with explained instances but differed in key attributes, for generating shorter explanations compared to far misses. The findings suggest that contrastive explanations, especially near misses, are helpful when structural differences need to be emphasized for highly similar instances [42], [43].

Another implementation of contrastive explanations within the integrative XAI framework based on concept-based and relational explanations (CoReX) combining CRP and ILP [30] aimed for explaining misclassifications instead of obtaining the shortest possible explanations (which could, however, also be integrated as formalized in [42]). The CoReX approach showed that contrastive explanations for ILP-based surrogate models can reveal which concepts have not been sufficiently assigned with relevance by a CNN. This insufficiency was logically proven by tracing the background knowledge of a misclassified example and finding insufficient support as a cause for not fulfilling the rules of the interpretable surrogate model [30].

4.3.2 Prototype-based explanations as an example-based approach

As motivated earlier, prototypes can be helpful, where data is highly complex and cannot be generalized into one single rule, function or even model [12]. Prototype-based explanations can provide a more global view on the model’s decision behavior compared to other example-based explanations, especially if they are based on aggregating most influential features [46].

In the integrative XAI framework, prototype-based explanations were used to aggregate local explanations to reduce the information load put on explainees. In particular, local explanation aggregation for deriving prototypes from temporal sequences of video frames was successfully applied for facial expression recognition [46]. Respective temporal prototypes were extracted from t-SNE (SpRAy) clusters generated based on local explanations of similar video frames. The temporal prototypes further enhanced interpretability by illustrating typical changes in facial expressions over time for different emotional states, e.g., surprise, while achieving a considerable information compression [46].

In another experiment, prototype-based explanations were derived from clustering ILP rules to identify structures in concepts learned by the model that could be generalized from individual example subsets [30]. The qualitative analysis revealed that examples covered by such prototypical rule sets may exhibit a biased distribution of features (e.g., smiling faces and long hair in female persons [30]).

4.3.3 Concept-based and relational explanations as a hybrid and human-centered approach

Concept-based and relational explanations provide a novel approach to explaining opaque base models. They can combine local and global explainability, may be realized in a model-specific or model-agnostic way and provide multimodal and possibly also example-based explanations to explainees.

For the proposed integrative XAI framework, a relevance propagation method, CRP in particular, was used as a concept extractor and combined with ILP to derive expressive concept-based and relational explanations for CNNs applied to complex knowledge domains [30].

Experiments showed that for the opaque base model CNNs, fine-tuned on binary classification tasks, ablating concepts in CNNs that have been integrated into rules by an ILP-based surrogate model, supports the concepts’ importance as well as the fidelity of the ILP model by considerable drops in each CNN’s performance. The experiments showed that concept-based ablation studies allow for a clearer understanding of how relevant and irrelevant concepts influence CNN predictions and that relational information may be superior to absolute relevance in concepts. Furthermore, a human study, particularly involving experts from ornithology, showed that combined, multimodal explanations (concept-based visualizations and verbalized relational rules) were considered more useful than purely visual or verbal explanations for distinguishing similar birds. The human evaluation also showed that descriptions from experts themselves may still be perceived as more useful than explanations from the proposed CoReX approach. The CoReX approach was also provided with user-defined constraints allowing for adaptation of ablations as well as exploration and control of model and explanation outputs [30].[3]

4.3.4 Multimodal, multiscope and example-based explanations in Human-AI dialogues

At the heart of every integrative XAI framework is the explanatory dialogue (see Figure 6). This is where all components flow together bi-directionally via an explanatory interface (from the AI model to the human and back) [26], [49]. As motivated earlier, integrating multimodal, multiscope and example-based explanations into explanatory dialogues, enables explainees to explore different aspects of a model’s decision-making process and outputs by benefiting from multifaceted views and intuitive interaction [12], [21], [71].

For the particular integrative XAI framework, an explanatory dialogue was implemented for digital pathology [31] with the functionality to answer requests from explainees about classification outcomes and to provide typical examples of healthy and diseased tissues as prototypes.

4.4 Summary

In summary, the methods used for the implementation of the integrative XAI frameworks were found to provide varying levels of transparency, complementing each other rather than producing redundant explanations. They have been evaluated as beneficial for validating and improving interpretable as well as opaque models and their decisions in complex knowledge domains, such as digital healthcare. Integrating such methods for explanations may facilitate the use of AI-assisted systems in other healthcare scenarios and beyond, while strengthening user trust [3], [12], [70].

5 Interdisciplinary collaboration, combined reasoning and AI evaluation as drivers of integrative XAI frameworks

A major lesson learned from the development of the proposed integrative XAI framework was, that it benefits from being based on a strong interdisciplinary collaboration. This surely holds for future integrative frameworks. Experts from the research fields of explainable artificial intelligence, cognitive science, human-computer interaction, ethics and the respective application domain (e.g., medicine) should work together to ensure that these frameworks are not only technically reliable but also intuitively comprehensible and usable for humans [21]. Computer scientists contribute technical expertise, while domain experts use their knowledge to ensure that model decisions and explanations are relevant and helpful for the application context. Cognitive and interaction insights are particularly helpful for the design of human-centered explanations to address the varying requirements of experts and non-experts [12], [71]. The inclusion of ethical considerations contributes to beneficial and trustworthy AI solutions, covering socio-technical aspects besides purely technical and cognitive ones [3].

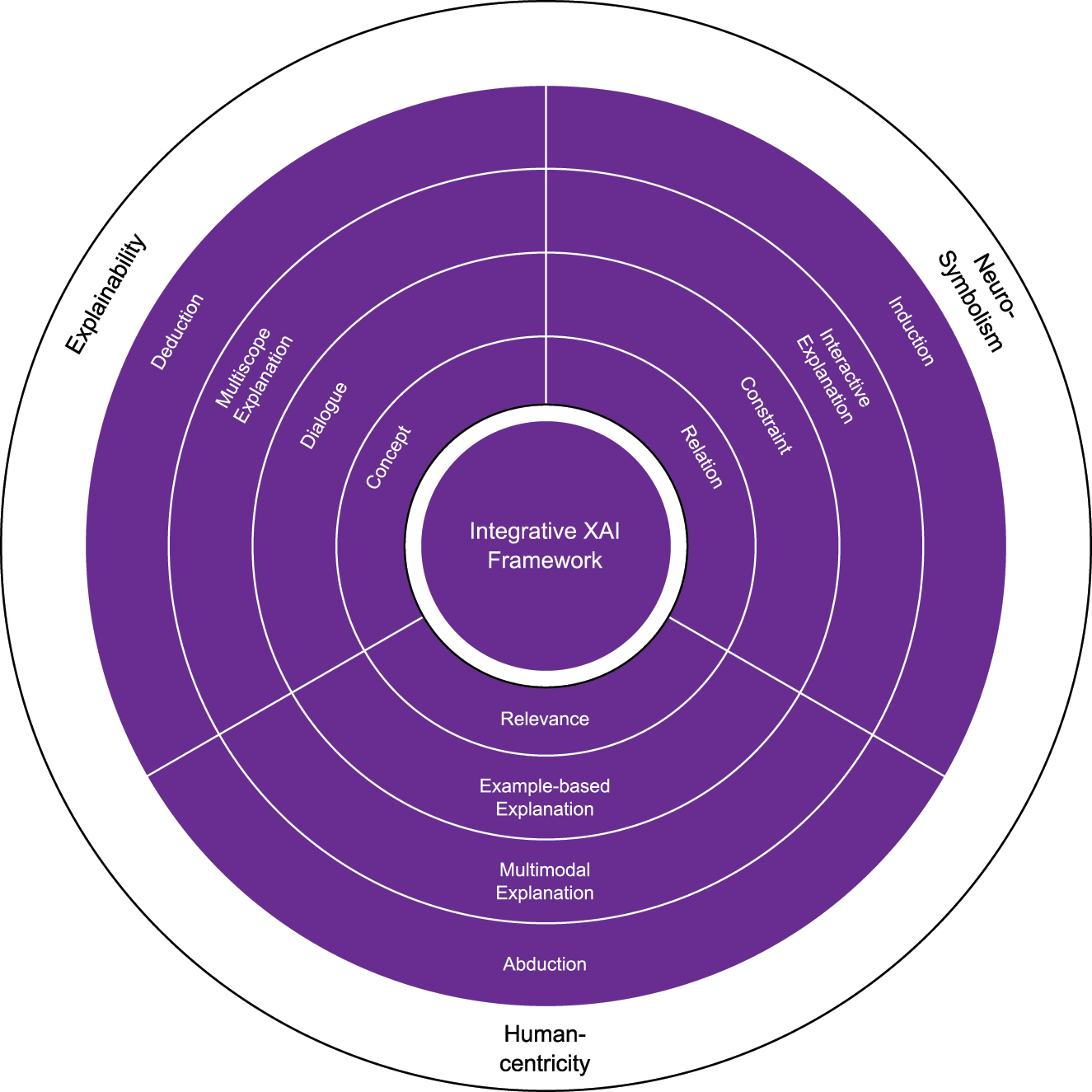

An aspect not discussed in detail in this work is the fact that integrative XAI frameworks combine different reasoning approaches, either in models or in human explainees. In particular, they integrate abductive, deductive and inductive explanation processes that together may support the iterative achievement of better generalization capabilities in human-AI collaboration [115], [116], [117]. In such processes abduction can foster discovery (e.g., of preliminary hypotheses to be tested), deduction can provide confirmation (e.g., by automated proofs) while induction supports generalization from observations for the purpose of explanation (e.g., based on representative concepts and relations found in model outputs [118]), leading to an integration of exploration, evaluation (optimization) and learning in an overall reasoning framework (see Figure 7). Such approaches are considered to be contributing to trustworthy AI [119].

![Figure 7:

Integrative XAI frameworks should integrate abductive, deductive as well as inductive explanation processes. This way they could fuse knowledge discovery, confirmation and generalization as introduced by Pierce [117]. Ultimately, the goal is, to integrate exploration, evaluation (optimization) and learning to create holistic frameworks.](/document/doi/10.1515/itit-2025-0007/asset/graphic/j_itit-2025-0007_fig_007.jpg)

Integrative XAI frameworks should integrate abductive, deductive as well as inductive explanation processes. This way they could fuse knowledge discovery, confirmation and generalization as introduced by Pierce [117]. Ultimately, the goal is, to integrate exploration, evaluation (optimization) and learning to create holistic frameworks.

For the technical part, integrative XAI frameworks as the one proposed and implemented, are developed at the intersection of three major research areas: explainability research (XAI), neuro-symbolic AI and human-centered research. A synthesis of all aspects relevant to realizing integrative XAI frameworks is illustrated in Figure 8 summarizing the contribution of the approach proposed, described and discussed in this work.

The proposed integrative XAI framework heavily relies on concepts and methods from the field of explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), abbreviated as explainability, from neuro-symbolic AI as well as human-centered AI research. Integrative XAI frameworks fuse abductive, deductive and inductive explanation processes. They provide multimodal explanations, multiscope explanations (also called multilevel explanations), they combine example-based explanations with explanatory dialogues and constraint-based guidance. The building blocks of explanations are concepts, relations and relevance (such as probabilities).

Under the hood, abduction, deduction and induction is supported by various functionalities and methods. Multimodal and multiscope explanations offer different perspectives on the system facilitating the creation, confirmation or revision of hypotheses about an AI model’s behavior. Interactive explanations allow for control and guidance during the process. Both, control and guidance can be implemented through explanatory dialogues and constraints, possibly complemented by example-based explanations that map abstract reasoning artifacts or attributions to concrete and realistic cases. This may include contrastive explanations, prototypes or case-based reasoning. The basic building blocks of such integrative XAI frameworks, especially for complex knowledge domains, are concepts, relations and relevance information (either in the form of attribution or probability [120]).