Young learners’ receptive L2 English vocabulary knowledge in relation to extramural English exposure at the onset of formal instruction in Norway

Abstract

Some young foreign/second language (L2) learners of English hardly know a single English word when starting school instruction. Others know many thanks to extensive English use outside of school, extramural English (EE). By investigating young L2 learners’ vocabulary knowledge at the onset of formal instruction, we can explore what roles EE may have for incidental learning prior to instruction. To date, research has shown that music, digital games, and TV are important EE sources and also indicated gender-related differences in EE use, but few studies have targeted very young learners. In this study, we collected data from 61 1st-grade learners (aged 5–6) in Norway. We used a shortened version of the Picture Vocabulary Size Test, a learner questionnaire, a parental questionnaire, a week-long language diary, and learner interviews (n = 8). The participants had an average receptive meaning recognition vocabulary of approximately 850 word families, but individual variation was considerable. Gender significantly predicted vocabulary size (boys > girls). Time spent watching TV and total EE time correlated most strongly with vocabulary scores. Whereas EE activities reported in the learner questionnaire were not correlated with vocabulary scores, EE activities in the Parental questionnaire were. Interview data revealed that learners viewed English as a lingua franca, but many showed limited grasp of English as a language and concept.

1 Introduction

Several studies on the relationship between young people’s engagement in extramural English activities on the one hand and learning English as a foreign/second language (L2) on the other have revealed positive results (for research overviews, see Kusyk et al. 2025; Zhang et al. 2021). However, this connection between extramural English (EE, Sundqvist 2009) and various aspects of L2 English proficiency, such as vocabulary knowledge, is less researched among very young learners in preschool or primary school, even though children as young as 5 years have been observed to consistently use L2 English in everyday communication with their peers during sessions of play (reported in Larsson et al. 2023, a study set in Sweden). The fact that children speak English with one another instead of using a shared L1 and/or the majority language is a very interesting phenomenon from a L2 learning perspective. It adds to already existing knowledge of the omnipresence of English in young people’s lives, including small children, and how English clearly impacts their daily life (see, e.g., Enever 2011; Hannibal Jensen 2017; Kuppens 2010; Unsworth et al. 2015). The review by Kusyk et al. (2025) reveals that most studies on the informal learning of L2 English through engagement in EE activities, such as listening to music or playing video games in English, originate from three clusters (Sweden and Finland; Germany and France; and Chinese mainland and Hong Kong), whereas research from Norway, the setting for the present study, is missing.

In Norway, the start of English instruction was lowered from the fourth grade to the first in 1997 (Ministry of Church Affairs Education and Research 1996). As regards the total number of hours for English instruction, the current curriculum implemented in 2020 stipulates that the total number should be 588 (138 h in grades 1–4; 228 in grades 5–7; and 222 in grades 8–10) (Norwegian Directorate for Edcuation and Training 2024).[1] This means that in grade 1 (age 6–7), which is the school year targeted here, students receive approximately 45 min of English per week. This formal intentional learning of English is complemented with informal (typically incidental) learning in the home in a technologically-advanced society such as Norway, where 24 % of 4–5-year-olds even have access to their own tablet (Norwegian Media Authority 2020), having English just a click away. In light of these circumstances, Sundqvist (2024) argues that the conditions for learning English have changed dramatically, and in a relatively short period of time. She refers to these circumstances as a structural change, and claims that in many parts of the world, and especially in contexts such as Norway, children’s own voluntary use of EE in their spare time has replaced English lessons in school as “the starting point for and foundation of learning English” (Sundqvist 2024: 1).

With this as a backdrop, an important observation is that previous research has shown that there is great individual variation as regards young people’s degree of engagement in various EE activities prior to instruction (De Wilde et al. 2020a; Puimège and Peters 2019). Thus, it is essential to uncover what role children’s informal learning of L2 English prior to schooling may play in terms of language development, and to learn more about the details regarding the level of proficiency amongst children at the very onset of formal instruction. Considering that vocabulary is “the bedrock of L2” (Ellis 1994: 11) and that words can be picked up incidentally through exposure, the aim of this study is to investigate the vocabulary knowledge amongst first-graders and to detect what roles EE and the young learners’ perception of the English language may have.

2 Extramural English exposure and L2 vocabulary knowledge

2.1 Definitions of key concepts

Several terms are used in the literature to refer to the informal learning of L2 English outside educational institutions. In the present study, we adopt the term extramural (‘outside the walls’) English as defined in Sundqvist and Sylvén (2016). EE involves voluntary learner-initiated (typically interest-driven) informal activities that are not connected with school(ing). EE activities can be both digital and non-digital and may encompass both incidental and intentional learning, but the former is much more common. Another important concept here is engagement, since learners themselves choose whether to engage in EE or not. There appears to be relatively strong agreement on a definition given in Fredricks et al. (2004), which says that engagement comprises three interrelated dimensions (or aspects), having to do with behavior, cognition, and affect/emotion (see, e.g., Mercer 2019, for an insightful discussion). Some suggest adding a social dimension to the concept (e.g. Svalberg 2009), whereas others, like Mercer (2019: 646), “take a situated view of learners meaning all aspects of cognition and affect are socially situated and behavior typically involves others in social settings”.

Related to self-regulated vocabulary learning, Schmitt (2008) emphasizes that any engagement that leads to being exposed to words, paying attention to or manipulating them, are beneficial for learning, and there are two key factors that will affect vocabulary learning: repetition (number of encounters with a word) and the quality of attention at each encounter (Webb and Nation 2017). To shed light on these key factors, Uchihara et al. (2019) have shown that incidental word learning is an incremental process which necessitates several encounters for creating a mapping of word form and meaning, but exactly how many encounters are needed is difficult to establish; a range of 8–10 encounters has been suggested in studies predominantly investigating learning from reading (see, e.g., Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt 2010; Webb 2007). However, some words are likely learned through considerably fewer repetitions, by being salient in some way to the learner. Conversely, some words may require many more repetitions, due to a host of factors. A further caveat is that different aspects of word knowledge may require different numbers of encounters (e.g., receptive versus productive skills).

It is assumed in vocabulary research that vocabulary consists of three dimensions: Vocabulary size/breadth, vocabulary depth, and vocabulary fluency/activation (Gyllstad 2013). Meara (1996) has argued that the basic dimension is size/breadth, and that learners with large vocabularies are more proficient in a wide range of language skills. Regarding L2 vocabulary, it is generally agreed that learning can happen through two main processes. Words may be learnt intentionally, through deliberate study of the form, meaning and use aspects of words and lexical phrases. As mentioned, vocabulary learning can also happen incidentally by sheer exposure to words and phrases whilst the focus of the learner is on comprehension, for example, when listening to the radio. Thus, incidental learning is a by-product of repeated exposure to language input. It stands to reason that a learner heavily engaged in EE is predicted to develop a larger vocabulary in comparison to a learner with a markedly more restricted exposure, on the assumption that no intentional word learning takes place. In line with these ideas, it follows that Sundqvist and Sylvén (2016) and other EE scholars (e.g., Liu et al. 2024) have advocated the benefits of engagement in EE for learning, suggesting that EE activities can be a means of increasing learners’ L2 vocabulary in particular (Peters et al. 2019; Webb 2015) “because of their potential for incidental learning” (Puimège and Peters 2019: 945). While a scoping review covering 206 informal L2 learning studies published between 2000 and 2020 shows that vocabulary is a preferred research objective, it also reveals that young learners (<10 years) are clearly the least investigated learner group (Kusyk et al. 2025). Thus, the present study contributes to filling that gap.

Next, we first present EE research involving young learners, defined as age 12 and younger. Whereas some of the studies cover connections between EE and several aspects of L2 English proficiency, our focus is specifically on findings that concern EE and L2 English vocabulary learning. We then present our research questions.

2.2 The connection between EE engagement and L2 English vocabulary knowledge

Young learner EE research generally reveals positive findings related to L2 English, in particular in technologically-advanced settings where children have easy access to the internet and the target language (English) through various digital devices. A review of the literature shows that these studies are all European; we present them here starting with the youngest learners and ending with those at the end of primary school (age 11/12).

In the Netherlands, L2 learning (English, French, or German) can be introduced early in the first grade when children are 4 years old. Most schools offer English. In this context, Unsworth and colleagues (2015) investigated factors that affect L2 English learning: formal instruction, input quantity and teachers’ language proficiency, and EE. They compared 168 learners divided into three groups receiving early instruction (<60 min/week, 60–120 min/week, or > 120 min/week) and a control group with no instruction. To measure vocabulary skills, the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 4, PPVTTM-4 (Dunn and Douglas 2007) was used, and for EE (“Out-of-school exposure”), a parental questionnaire. The EE variable did not correlate with vocabulary scores in the first post-test administered after 1 year of instruction, but did so in a second post-test after 2 years of instruction (PPVT mean scores ranged from about 10 to 32). However, EE was not a significant predictor in a regression analysis with children’s vocabulary scores as outcome variable. The return rate of the parental questionnaire was low (67 %), which might explain this finding, and the authors also suggest the participants might have been too young for EE to be a significant predictor of their English skills.

In Sweden, Sylvén (2022) used the same vocabulary test when investigating 7 children in kindergarten and 13 in first grade (exact ages undisclosed, but Swedish 1st-graders are aged 6–7). The purpose was to explore EE and proficiency, and to evaluate research instruments. The results showed a very large individual variation as regards both EE and vocabulary knowledge. On average, the 1st-graders spent 317 min/week on EE (SD = 265), ranging from 75 min/week to 983. The mean for the PPVTTM-4 (Dunn and Douglas 2007) in grade 1 was 59 (SD = 30.4). Notably, the participant reporting the highest engagement in EE scored at a level equivalent to that of a native speaker aged 14–16. A recent study from Spain which also involved 1st-grade learners (N = 176) adopted the same vocabulary test (Soto-Corominas et al. 2024). The focus here was on the effects of (a) a content and language integrated learning (CLIL) approach and (b) different sources of individual difference (including EE) on learners’ receptive and productive L2 English skills. The findings showed that participants who reported more engagement in EE activities and participants with more educated mothers performed better; the median vocabulary test score at the end of first grade was 25 (CLIL learners) and 27 (non-CLIL).

An early EE study from Iceland found that 7- and 8-year-olds (N = 182) picked up a great deal of English incidentally (Lefever 2010). These children had not had any formal English instruction in school and reading, listening, and conversational skills (a subsample, n = 51) were examined. It is noted that some children were “capable of spontaneous interaction and had a strong desire to express themselves [in English]” (p. 92) and while there were no gender-differences for reading and listening, the boys scored significantly higher than the girls on conversational skills (the effect size was large: phi = 0.44). The author interviewed the parents of 10 children and found that some children used English words with one another during play, others were frequent gamers, and all were frequently exposed to English through media.

In Denmark, Hannibal Jensen (2017) researched young learners (8–10 years, N = 107) to map EE activities (language diary, parentally guided) and vocabulary knowledge. Seven EE-activities were listed in the diary: gaming, listening to music, reading, talking, watching television, writing, and other. The most time was spent on gaming (rank 3 for girls, rank 1 for boys), music (rank 1 for girls, rank 3 for boys), and watching television (rank 2 for both genders). No significant difference was observed between boys’ and girls’ vocabulary scores. However, playing digital games with both oral and written English input and gaming with only written English input were significantly related to vocabulary scores, as measured by the PPVTTM-4 (Dunn and Douglas 2007), and especially so for boys (Hannibal Jensen 2017).

Hubbe Emilsson (2021) also studied learners aged 8–10 years (N = 24), but in Sweden. Information on EE activities was gathered using a learner and a parent questionnaire. Vocabulary knowledge was assessed through the Picture Vocabulary Size Test (PVST, Anthony and Nation 2017). Top-reported activities were gaming, watching YouTube, and watching English-speaking films. Correlations at 0.64–0.80 were found for reported EE activities and PVST scores. No significant gender difference was found for vocabulary.

In another study from Spain targeting English CLIL programs in primary school, the aim was to analyze the impact of CLIL on the four language skills alongside three more factors: EE, socioeconomic status, and non-verbal intelligence (Lázaro-Ibarrola 2024). The participants (N = 171, aged 10–11) were divided into two groups depending on the intensity of the CLIL program (High or Low). The results revealed that engagement in EE was very frequent in both groups, but more so in the High Intensity group (mean: 8.4 h/week). Music was the most popular activity. In addition, there were several positive associations between EE and learners’ scores, and speaking appeared to be particularly influenced by EE.

In a large-scale project focusing on early language learning in Europe (ELLiE), data were drawn from more than 1,400 children from Croatia, England, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden, all with an early introduction of formal English instruction (Enever 2011). A sub-study of ELLiE examined the effect of out-of-school variables on participants’ listening and reading skills when in the fourth year of English instruction (N = 865, age 10–11) (Lindgren and Muñoz 2013). The results showed that cognate linguistic distance was the strongest predictor for both listening and reading, but this was followed closely by EE. Parents’ educational levels had an effect, but only on reading scores. Viewing films in English was the most predictive EE activity.

In a Swedish study including 11- and 12-year-olds (N = 86), the researchers examined the relationship between EE gaming on the one hand and vocabulary knowledge, listening comprehension, and reading comprehension on the other (Sylvén and Sundqvist 2012). The Young Learner Vocabulary Assessment Test (Sylvén and Sundqvist 2016) was used and a comparison of the vocabulary scores for three ‘gamer groups’ showed that the frequent gamers (cut off: ≥ 5 h/week) scored higher than the moderate gamers, who outperformed the non-gamers (the same pattern was found also for the other tests). None of the examined background variables could explain the between-group differences, so gaming turned out to be an important EE variable. It was also the most popular EE activity, followed by watching TV, and listening to music. A one-week language diary with 7 predetermined activities and one open option was used.

In Flanders, the Dutch speaking part of Belgium, French is introduced in the 5th grade whereas English instruction starts late, in the 7th or 8th grade. Three large-scale studies carried out in the 6th grade (De Wilde et al. 2020a, 2020b; Puimège and Peters 2019) provide overwhelming evidence that these young learners (age 10–12) know a lot of English, despite never having had a single lesson in school. For example, results showed that they know more than 3,000 English word families (Puimège and Peters 2019) and many performed at the A2 level (according to the Common European Framework of Reference, Council of Europe 2020) for listening, speaking, reading and writing (De Wilde et al. 2020a).

Summing up, there is without a doubt a connection between young learners’ EE engagement and L2 English vocabulary learning. The affordances of multimodal input through audio-visual materials are prominent in all reviewed studies and YouTube, launched in 2005, has grown increasingly popular over time and almost seems to have turned into an EE activity of its own (see also Kusyk et al. 2025; Sundqvist 2024).

2.3 Research questions

The following research questions (RQs) were postulated for the present study:

RQ1:

What is young Norwegian learners’ receptive English word meaning recognition knowledge at the onset of formal instruction in the English subject?

RQ2:

To what extent is there a relation between children’s self-reported EE activities, parents’ reported EE activity for their child, and the child’s English word meaning recognition?

RQ3:

What characterizes young Norwegian learners’ perceptions about English and English language learning?

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

Sixty-one first grade children participated in the study, as shown in Table 1. They came from five classes from two schools (denoted S02 and S04) in Norway. School S04 was located in a city (>100,000 inhabitants), and School S02 in a small town (<10,000 inhabitants). In Norway, the Norwegian Directorate for Education publishes statistics about all schools. As part of this, a so-called school contributor index (SCI) can be computed. In general terms, it signifies the difference between how students at a school perform and how they are expected to perform whilst controlling for certain conditions (previous school results, parents’ education level, household income and immigration background). If the performance matches the expectations, the school has the same index as the mean for all schools in Norway, which is 0. If the index is positive, the school’s contribution is above average for the country, and if negative, it is below average. Based on the SCIs for 2021/2022, School S02 was associated with a SCI of −0.3 whereas School S04’s SCI was 3.5.

The sample size, age and school of the study participants.

| Gender | N | Age | School | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | n from school S02 | n from school S04 | ||

| Boys | 32 | 5.81 | 0.40 | 25 | 7 |

| Girls | 29 | 5.82 | 0.39 | 21 | 8 |

| Total | 61 | 5.82 | 0.39 | 46 | 15 |

The language situation in the home of the participants is provided in Table 2. All except two of the care-takers of the children reported using predominantly Norwegian with their child. Specifically, one third stated that Norwegian was the only language used, and another 20 % reported use of Norwegian and another language (not English).

Languages used by parents in the home when communicating with child.

| Group | N | Example of languages |

|---|---|---|

| Only Norwegian | 22 | |

| Norwegian + other language(s) | 15 | Arabic, Dari, Somali, Swedish, Urdu |

| Norwegian + English + other language | 9 | |

| Norwegian + English | 9 | |

| Only other language | 2 | Arabic, Macedonian |

| Not reported | 4 | |

| TOT | 61 |

English was used in combination with Norwegian or another language by one third of the participants.

3.2 Data collection instruments

The study made use of a mixed-methods approach, whereby predominantly quantitative test and questionnaire data were complemented with qualitative diary and interview data. In total, five instruments were used: A learner questionnaire of extramural English activities (EEQ), a parental questionnaire (PQ), a shortened version (PVST-S) of the Picture Vocabulary Size Test (PVST) (Anthony and Nation 2017), a Language Diary (LD), and Student Interviews (SI). These instruments are described below.

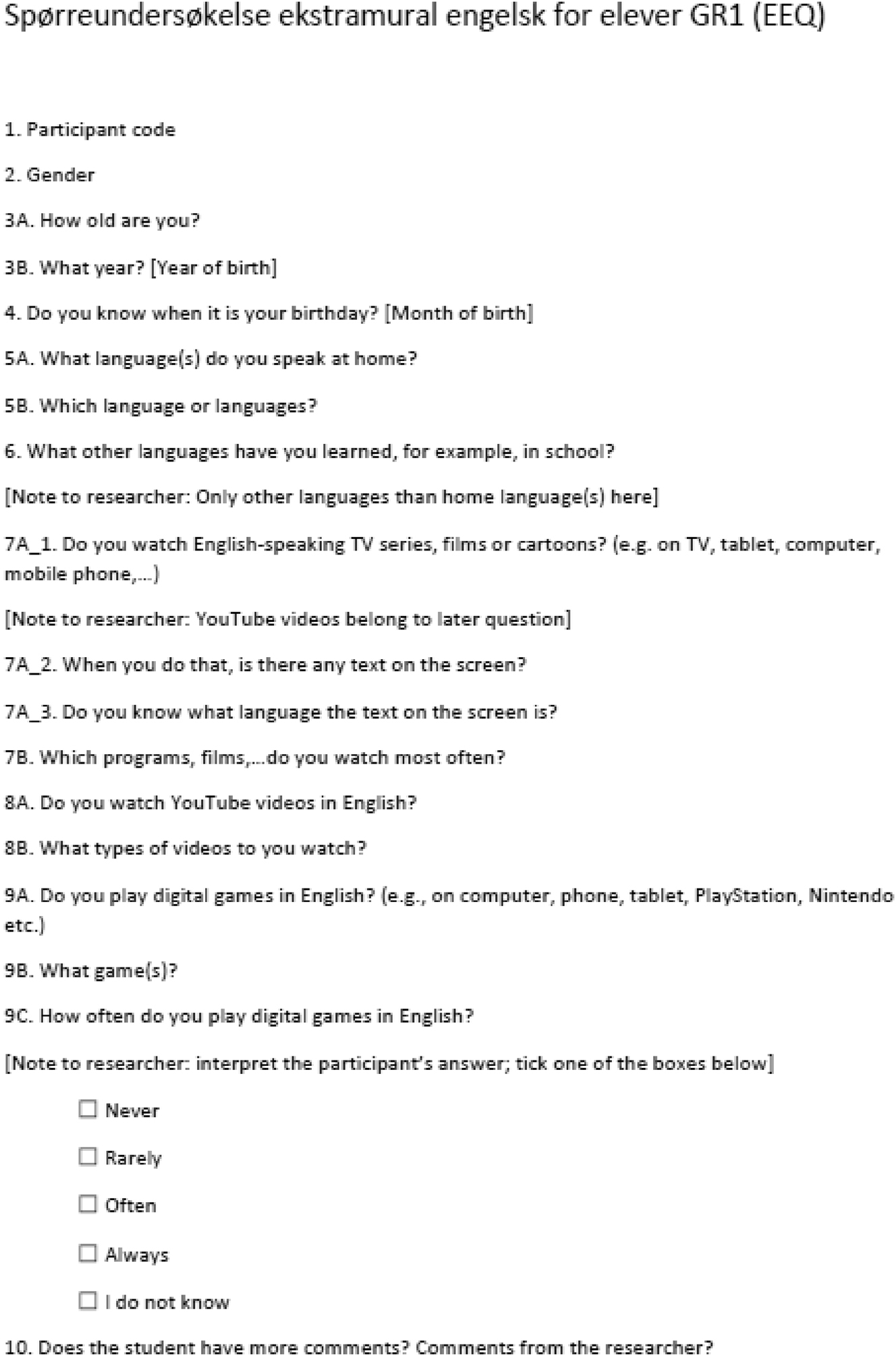

3.2.1 Extramural English learner questionnaire (EEQ)

We used a short oral questionnaire to gather information about EE directly from the child (the Extramural English Questionnaire, EEQ, see Appendix B). We asked about watching English-speaking TV series, films, or cartoons (with follow-up questions about possible text on the screen), YouTube, and gaming (including types of games and frequency). The EEQ also served the purpose of eliciting information about the participant’s birthdate, languages spoken in the home, and possible languages (other than English) learnt in school. The coding of the EEQ entailed giving the participants a score of 0, 0.33, 0.67 or 1 according to their answers to three questions in the EEQ: Do you watch English-speaking TV series, films or cartoons?; Do you watch YouTube videos in English?; Do you play digital games in English? For each question answered affirmatively, they received an 0.33 increment, and the resulting score was used as an EEQ index.

3.2.2 Parental questionnaire (PQ)

We developed a questionnaire for the parents/guardians to take into account the possible influence of their educational level and language background (see Appendix C). The PQ also included a multi-item question asking about how often their child engaged in five different EE activities: watching TV or videos, using the internet, gaming, listening to music, and “other hobbies in English” (with space for adding details). Following Puimège and Peters (2019), we used a 5-grade Likert scale: (Almost) never; Every month; Every week; A few days a week; Every day. The return rate was 100 %. The coding of the PQ entailed computing an index based on an average of the Likert scores for each child.

3.2.3 A shortened version of the Picture Vocabulary Size Test (PVST)

The original PVST (Anthony and Nation 2017) is a 96-item multiple-choice test of receptive vocabulary meaning-recognition, intended for young pre-literate native speakers up to eight years old and young non-native speakers of English. Each item comes with a set of 4 images (A–D), where the correct answer image appears together with 3 distractors. Test-takers’ scores can be extrapolated into how many words they know in the target language out of the most frequent 6,000-word families of English. We created a short version of this test (named PVST-S) by selecting 31 items (see Appendix A) of the original 96. This was done as administering all 96 items was deemed too demanding for the targeted age group of non-native speakers (5–6 years old). On the assumption that each item required 20 s, amounting to over 30 min for the original whole test version, we aimed at a test length of 10–12 min. This corresponded to roughly a third of the original items. The use of at least 30 items for a test measuring a test-taker’s vocabulary size has been recommended by vocabulary experts (Nation 2016: 180). The items for the short version were chosen based on information from a database indicating the age at which the words were learned, Age of Acquisition (AoA), by native speakers of English (Kuperman et al. 2012). The 31 words were all words known by 6-year-old first-language (L1) English speakers. In addition to the four answer alternatives in each item, the PVST-S also included a “I don’t know” option (IDK).

The PVST-S meaning recognition test was scored by awarding 1 point for each correctly answered item. Scores of 0 were awarded for incorrect answers, IDK answers, as well as blanks. The maximum score was 31.

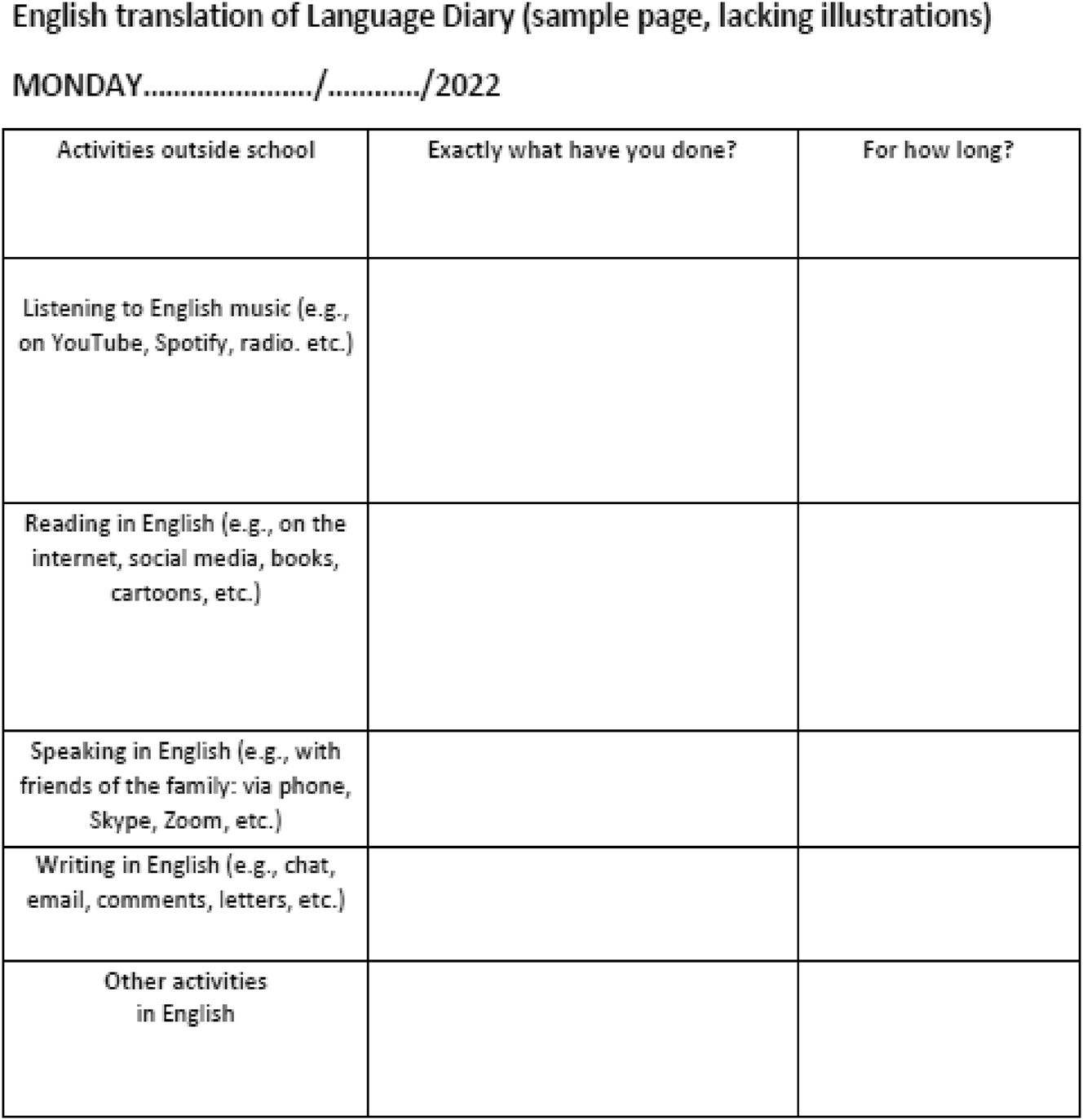

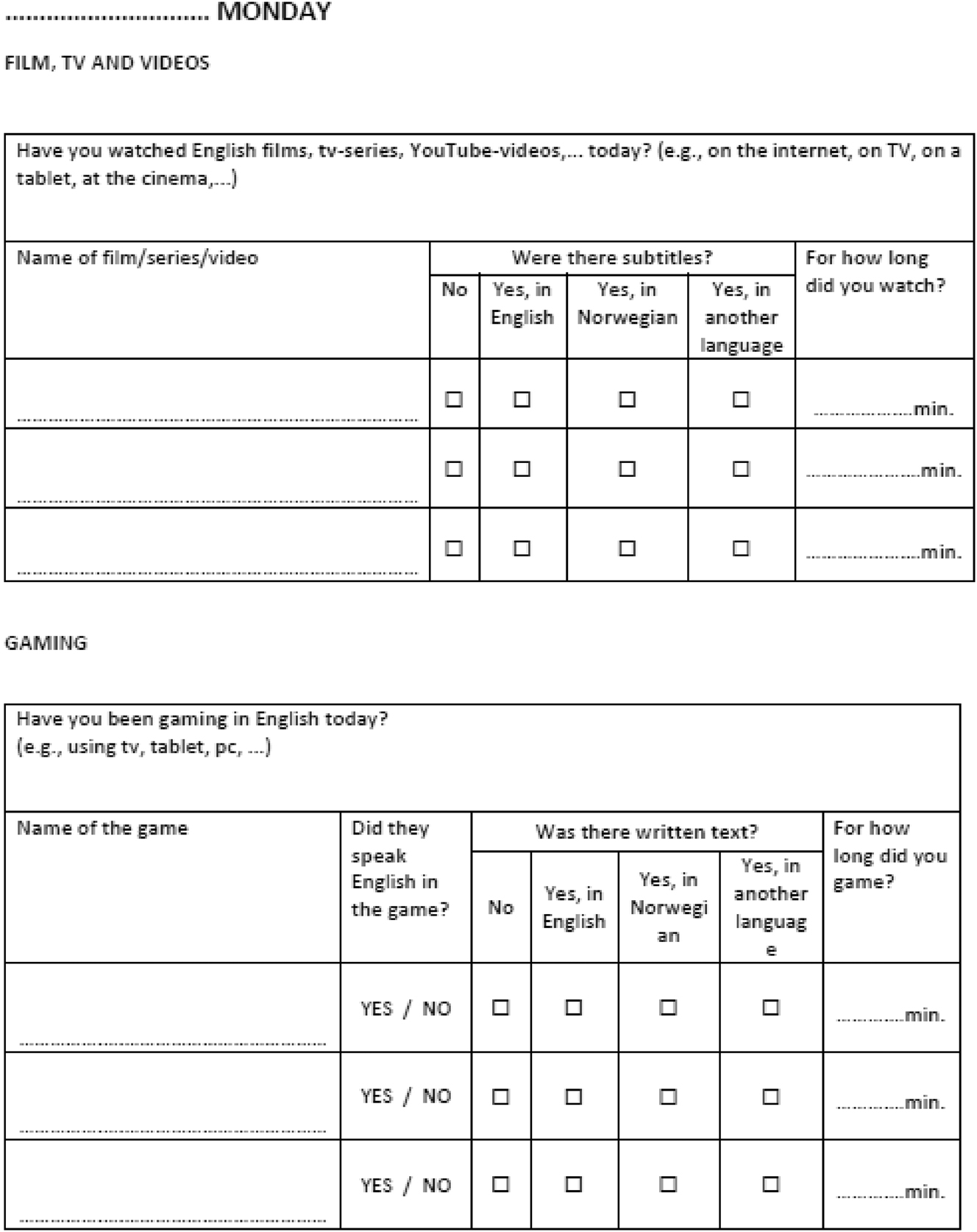

3.2.4 Language diaries

Inspired by Hannibal Jensen (2017), we developed a Language Diary (LD) which was filled out with parental help in the home for one week. It covered six EE activities (listening to music, reading, speaking, writing, watching, and gaming), with accompanying specifications about, for example, the names of all chosen activities and estimates for how long each activity lasted (see Appendix D). The return rate was 66 %. The LDs were used for quantitative analysis as well as artifacts in the learner interviews.

3.2.5 Learner interviews

Eight first-grade learners participated in semi-structured interviews, based on information collected from the instruments used in the study (EEQ, PQ, LDs and PVST-S), as well as informal conversations with their teachers. Participants were interviewed in pairs during school hours. Interviews lasted 14–27 min, and participants were asked to report and reflect on their EE activities and incidental and formal learning of English. Participants coloured smileys to consent to participation, and continued colouring or drawing throughout the interview. Pictures of the word “English” and of technological devices (Nintendo Switch, PlayStation consoles, smart phones) as well as participants’ LDs were used as artifacts during interviews.

3.3 Procedures

The collection of data took place in the first semester of the school year, in October-November, preceded by researcher participation in parental meetings in June and August of the same year. During these meetings, parents were informed about the project aims and the implications for their children’s participation. Parental consent and the PQ were collected during these meetings.

Data collection involving the children commenced with an in-class introduction of the researchers, an age-appropriate account of the project, and information about what it meant for participants to participate (10–15 min). Data were collected one-on-one with each participant, while the rest of the class continued with their regular lessons.

The researcher escorted each participant to a separate data collection room. The participant was given the choice to sign a consent form by coloring a pre-printed smiling face (consent) or a frowning face (no consent) on a sheet of paper. All children consented, and the researcher commenced with the data collection.

Each participant first sat the PVST-S. The PVST-S items were shown on slides on a computer. For each item, the researcher read the target word out loud twice. Participants were then asked to point at the picture out of four that best represented the meaning of the word. Participants also had the option to say that they did not know the answer, by pointing at the image of a question mark (see example of item slide in Appendix E, which was used as a practice item).

For the EEQ, the researcher presented each question in an age-appropriate way, for example by breaking it down into shorter questions. The goal was to simulate a conversation with the participants, creating a more natural environment for them, since young learners are particularly vulnerable in assessment situations (McKay 2006). The researchers filled out the online form on the spot according to the participants’ answers.

Each participant spent approximately 30 min with a researcher. After completion, participants received a Language Diary with their names written on it. Participants were reminded to hand over the diaries to their parents, who had been asked beforehand to fill them out with their child once per day for a week.

4 Results

4.1 Vocabulary scores

The scores from the PVST-S are presented in Table 3. The total mean score was just over 12 (out of 31). The reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for the PVST-S data was an acceptable 0.79. As a benchmark, Hubbe Emilsson (2021) reported a reliability of 0.85 for the full 96-item test. As longer tests (more items) typically lead to a higher reliability, having a slightly lower value with only 1/3 of the items is a positive outcome. The sampling ratio of 16:1,000 in the original PVST would have afforded an extrapolation by multiplying a score by 62.5 for the most frequent 6,000 words (Anthony and Nation 2017). However, our use of a modified, shorter version resulted in a lower sampling rate (see Gyllstad et al. 2015). As a majority of words came from the 1–2 K bands (see Appendix A), we have also reported the mean score for these 20 high frequency words in Table 3. The sample ratio 20:2,000 thus rendered a multiplication value of 100, and an extrapolated mean vocabulary level of 862 words.

Descriptive statistics for PVST-S scores by gender and in total.

| Gender | N | PVST-S score All words (k = 31) |

PVST-S score 1–2 K words (k = 20) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 95 %CI | Mean | SD | 95 %CI | ||

| Boys | 32 | 12.88 | 5.36 | [11.53, 14.22] | 8.84 | 3.86 | [7.88, 9.81] |

| Girls | 29 | 11.38 | 4.63 | [10.22, 12.54] | 8.38 | 3.85 | [7.41, 9.34] |

| Totala | 61 | 12.16 | 5.12 | [10.87, 13.44] | 8.62 | 3.83 | [7.66, 9.58] |

-

Note. aCronbach’s Alpha reliability: 0.79.

The Item facility (IF) values of the 31 words are visualized in Figure 1. The items varied between 0.89 and 0.07 (89 % and 7 %, respectively, of the testtakers who answered correctly). The easiest item was cream and the most difficult canary. To find out whether the frequency of the word was related to the IFs, the IFs for the words were plotted against the frequency band number that the words were taken from. Figure 2 visualizes the level of the correlation (−0.357).

Item facility values for the 31 items in PVST-S (N = 61).

Item facility values (IFs) (Y-axis) as a function of frequency band (X-axis) for the 31 Items in PVST-S (N = 61).

Trend-wise, Figure 2 shows how a lower frequency band rank for a word corresponds to a lower IF. It should be noted, though, that words from frequency band 1 displayed a wide range of IFs.

One factor known to affect L2 vocabulary knowledge is cognateness between the target language and a learner’s first language. Cognates, defined as translation equivalents with high orthographic overlap, can be identical or similar. There were 12 cognate words (indicated in Appendix A), none of them identical, only similar. The mean IF value for the cognates was 0.44 (SD = 0.22) compared to 0.36 (SD = 0.20) for the non-cognates, and a t-test comparison of these means yielded a non-significant result (mean difference = 0.073, t = 0.951, p = 0.359). The Levenshtein distance (Levenshtein 1966) metric can be used to indicate how close two words are orthographically, by counting the minimal number of substitutions, insertions, and deletions to edit one string of letters into another of any length. As comparing the phonetic representations would be more ecologically valid for young learners who are not yet literate (see De Wilde et al. 2020a), we also computed values for the phonetic representations. Correlations were then run between the Levenhstein distance values and the IF values to see if degree of similarity affected the IF, using Kendall’s Tau for small data sets and many tied ranks. The correlation for orthographic form was τ = −0.112, p = 0.625, whereas it was τ = −0.148, p = 0.536 for the phonetic form. Consequently, the similarity between the cognate words did not have any statistically significant effect on how easy they were for the learner group.

4.2 The relation between extramural English and vocabulary knowledge

Figure 3 shows the participants’ self-reported exposure to the sources in the EEQ: English-speaking TV, English material on YouTube, and English videogames. Eleven children reported exposure to no sources (18 %), 15 to one source (25 %), 18 to two sources (30 %) and 14 to all three sources (23 %). Data was not available for three students.

Children’s self-reported number of EE sources exposed to (N = 58).

Out of the 61 participating learners, 38 submitted their language diary. The reported time spent on EE overall was tallied and correlated with the PVST-S scores (see Table 4). All activities except Writing (no time reported) showed positive relations to the PVST-S scores. Two correlations were statistically significant: time spent watching TV and total time spent on EE activities.

Correlations (rho) between PVST-S scores and reported time on EE activities during a week (LD Data).

| Reported time spent on EE activities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Music | Reading | Speaking | Writing | Other | TV | Gaming | Total | |

| Mean | 89 | 9 | 80 | 0 | 12 | 95 | 28 | 313 |

| SD | 98 | 24 | 422 | 0 | 46 | 107 | 49 | 528 |

| PVST-S | 0.181 | 0.154 | 0.220 | n.a. | 0.028 | 0.424a | 0.099 | 0.426a |

| Score corr (sig.) | 0.277 | 0.356 | 0.183 | n.a. | 0.868 | 0.008 | 0.553 | 0.008 |

-

Note. Mean times and SDs are in minutes; Spearman’s rho correlations. aSignificant at p = < 0.01.

The activities that most learners engaged in were Listening to music and Watching TV. The large standard deviations illustrate substantial variation in time reported. For many learners, no time was reported on many activities, mainly Reading and Other.

To further address RQ2, a mixed-effects model (MEM) based on the whole participant sample was used. MEM provides many advantages over traditional analysis of variance, such as accounting for random variation in items and participants in one analysis, being robust against violations of homoscedasticity and sphericity, and combining random and fixed effects in the same analysis (Linck and Cunnings 2015). We used R version 4.4.0 (R Core Team 2021) together with R Studio (Version: 2023.12.1). We employed a mixed effects logistic regression model. The model used item score on the PVST-S as the binary dependent variable (correct = 1, incorrect = 0) using the glmer function with a binomial family under the lme4 package (Version 1.1–35.1; Bates et al. 2015). The optimizer ‘bobyqa’ was used.

Table 5 reports the MEM and its parameters. The model included the EEQ index, the PQ index and gender as the primary fixed effects. We also included maternal education level, word AoA, and word frequency band as covariates. These were included as previous research has indicated that they are relevant factors (De Wilde et al. 2020b; Soto-Corominas et al. 2024). Random intercepts were specified for items and participants, and participants were nested in Class and School. Further specification of the random-effects structure led to a failure to converge.

Mixed effects logistic regression model for scores on the 31-item PVST-S (N = 61).

| Parameter | β | SE | z | p (>|z|) | Exp (β)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| (Intercept) | 1.024 | 1.030 | 0.994 | 0.320 | 2.784 | |

| EEQ | −0.091 | 0.327 | −0.279 | 0.780 | 0.913 | |

| PQ | 0.380 | 0.115 | 3.298 | < 0.001 | *** | 1.462 |

| AoA | −0.328 | 0.155 | −2.117 | 0.034 | * | 0.720 |

| Gender girl | −0.537 | 0.239 | −2.251 | 0.024 | * | 0.584 |

| Mother_Education | 0.309 | 0.242 | 1.273 | 0.203 | 1.362 | |

| Item_freq_band | −0.259 | 0.113 | −2.303 | 0.021 | * | 0.772 |

|

|

||||||

| Variance | SD | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Random effects | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| School:class:stud_code | 0.530 | 0.728 | ||||

| Word | 0.856 | 0.925 | ||||

-

Note. Estimation method: maximum likelihood (Laplace Approximation) [’glmerMod’]. aOdds ratio calculated based on log odds estimates (β); R 2 marginal = 0.10; R 2 conditional = 0.36. *** = Sig. at p < .001, * = Sig. at p < .05.

Estimates are on the log-odds scale, but exponentiated values (Exp β) are also reported in the right-most column in Table 5. As to the fixed effects, the children’s own EEQ index failed to reach significance. However, there was a statistically significant effect for the PQ index of parents’ reported child EE activity on the children’s vocabulary score. The estimate of 0.380 for PQ means that a 1 unit increase in PQ index is associated with a 0.380 increase in the log-odds of an item score being 1, compared to it being 0.

If exponentiated this number yields the odds ratio (Exp β) of 1.462, as seen in Table 5. Additional significant effects were observed for gender, whereby the odds of answering a PVST-S item correctly were 42 % lower for girls compared to boys, if keeping all other variables constant (given an odds ratio of Exp (−0.537) = 0.584). Thus, gender had an effect on the participants’ receptive word knowledge. Equally significant was the co-variate of AoA (i.e., the age at which native speakers of English are estimated to have acquired a word). Word frequency was also a negative estimate, indicating a lower score on the PVST-S as an effect of decreased word frequency.

4.3 The learners’ perceptions about English and English language learning

A final analysis was based on the interview data. The interviews served two purposes. One purpose was to shed light on the learners’ perceptions about English and their own learning and use of English through a thematic analysis. Another purpose was to further shed light on the relationship between amount of EE and word meaning recognition knowledge for a subsample of eight learners. Table 6 provides information on the subsample of interviewees, appearing as pseudonyms.

Information on the eight interview participants (all age 6).

| Pseudonym | Home language(s) | PVST-S score | PQ index | EE activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marcus | Arabic, Norwegian | 13 | 4.50 | Games, YouTube, Interaction |

| Theo | Norwegian | 13 | 2.25 | YouTube, Interaction |

| Celine | Norwegian | 14 | 4.00 | Music, YouTube, TV, Interaction |

| Leah | Norwegian | 9 | 3.75 | YouTube, TV, Music |

| Kake | Kurdish, Norwegian | 11 | 4.00 | YouTube, TV, Interaction Reading, Role play w. dolls |

| Tagg | Norwegian | 5 | 3.25 | Music, YouTube, Films, Games, TV |

| Bro | Norwegian | 25 | 4.00 | Games, YouTube, Music |

| Cole | Norwegian | 24 | 3.20 | Games, Music, Youtube, Interaction |

-

Note. EE activities are based on LDs. Marcus did not submit an LD; EE activities are in his case based on interview data. “Interaction” refers to spoken interaction with parents or siblings.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and subjected to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2022) with the aim to explore RQ3. First, emerging patterns in the material were identified from familiarising ourselves with the dataset through listening to audio recordings and reading transcripts multiple times. Based on these, potential codes were developed, and the entire dataset was then coded systematically. The codes were developed into themes, which in turn were reviewed to ensure that they highlighted the patterned meaning across the dataset in relation to the research question.

Two themes were developed in the thematic analysis. First, English was perceived to be a lingua franca; English could be used to communicate with people who could not speak Norwegian, as argued by Marcus: “if someone is new here, coming to the class, and can’t do Norwegian, then we can talk to them”. Such reflections were offered as answers to questions about reasons for learning English, but not all the participants answered the question. For some the concept of English as a language, or of language in general, seemed to be difficult to grasp. “English” was frequently associated with the school subject.

The second theme was related to perceptions about English language learning. The young learners agreed that they had known some English before starting school, but they had a difficult time remembering where this knowledge originated. Some answered at home and some the kindergarten, but they could not answer who had actually taught them. Cole explained that English one day had appeared in his repertoire, when he was 3 or 4 years old: “I just thought that it was English, then I started talking it”. Neither Cole nor the other young learners suggested EE as a source of English learning when asked explicitly about this, but some of them still offered reflections about incidental learning from EE, specifically from music. Another interviewee was Bro. When asked why he listened to English songs instead of Norwegian songs at bedtime, Bro offered incidental English learning as a reason: “I want to learn English while I am sleeping in my brain”.

In the same vein, Celine explained that she listened to English music rather than Norwegian because she wanted to learn English. She also said that English songs were more fun, as did Leah and Tagg. Tagg also said that English songs were “more real”, suggesting perceived authenticity of English in relation to music. Apart from this metalinguistic awareness related to English music, the participants did not seem to deliberately target English-language content. Rather, they chose digital platforms, games and content based on their interests, and these happened to be in English.

Information about participants’ EE exposure obtained in the interviews suggested that there is no straightforward relationship between amount of EE and word meaning recognition. Celine, for instance, had very positive attitudes to English and was able to produce whole sentences in English in the interview. However, her PVST-S score was just slightly above the mean (14 points). Tagg’s LD showed that she engaged in considerable amounts and varying types of EE, but her PVST-S score was low (5 points). Bro and Cole, who had very high PVST-S scores (25 and 24 points), stood out among the interview participants as avid gamers. In the interviews, they enthusiastically listed games that they engaged with, and they both reported to game with family members. Although there is not enough evidence to draw inferences about influence from gaming on word meaning recognition from these individual cases, the concurrence is interesting and merits further study.

5 Discussion

Our discussion will take the RQs as points of departure. For each RQ, we first briefly summarize the results, compare them with previous studies, and then venture into potential explanations for observed differences and/or similarities.

RQ1 asked “What is young Norwegian learners’ approximate receptive English word meaning recognition knowledge at the onset of formal instruction in the English subject?”. We used an age-appropriate, shortened version of the PVST (PVST-S) comprising 31 items. The mean score was 12.16 (SD 5.12) out of the maximum score of 31. Furthermore, for 20 of the 31 words frequent enough to be amongst the first 2,000 words of English, the participating children knew on average 8.6 words (∼40 %), by extrapolation equivalent to approximately 850 word families. Two aspects of these results are noteworthy, namely the observed mean number of known words and the large variation.

Starting with known number of words, it makes sense to first establish a baseline for sake of comparison: How large are the vocabularies of L1 English children? Miralpeix (2020) points to the fact that there are very few studies of young L1 learners at school. In one existing study, five-year-old children were reported to know 4,000–5,000 word families (Nation and Waring 1997). Clearly, our Norwegian sample are far below such levels, but how do they fare in comparison to learners of English as a foreign language? At the time of testing, our group of learners had had very little English instruction (between 2.5 and 7.5 h in total). In light of previous studies in the literature, where learners of English had had considerable amounts of instruction, possessing vocabularies of the sizes observed for our Norwegian sample is no small feat. In a study on Spanish young learners of English in 4th grade, i.e. somewhat older (aged 10), Jiménez Catalán and Terrazas Gallego (2008) reported sizes of around 900 words, but this was after three years of English instruction. Schmitt (2010: 9) even reports on comparable levels of English vocabulary size, around 1,000 words (after 400 h of instruction) of much older foreign language learners, such as high school pupils in France and Germany. Slightly higher sizes of around 1,200 words have even been reported for university level students in Indonesia (after 900 h of instruction). English learners in grade 5 in Turkey (Kavanoz and Varol 2019), scored close to 2,000 words. These learners had had English instruction since the 1st grade. In a small-scale study of learners closer in age in similar settings in Scandinavia, Hubbe Emilsson (2021) reported mean sizes of somewhat older Swedish learners, 2nd and 3rd grade, of around 3,300 words. This was after approximately 26 and 66 h of instruction, respectively. It is of course an empirical question whether our sample from Norway would reach a mean of 3,000 words within 2 years, but it would not be unthinkable. Although research on vocabulary growth rates in a L2 has shown that learners can acquire around 400 word families per year (Webb and Chang 2012), these learners were older than our participants but likely had less extramural input, so a clear-cut comparison is not possible. Vocabulary sizes of 3,000 English word families for pre-instruction, high-extramural input learners were reported in Puimège and Peters (2019), based on a sample of Belgium children aged 10–12.

A relevant question is what pre-literate foreign language learners of English with a vocabulary of 800–1,000 words can do in the target language. Schmitt and Schmitt (2014) have suggested a frequency-based division of vocabulary into high- (1–3,000), mid- (3,001–9,000) and low-frequency (9,001-) words and emphasized the importance of acquiring the high-frequency vocabulary of the 3,000 most frequent words. The reason for this is that evidence suggests having a vocabulary of 3,000 words (some studies suggest 2,000) allows a user to largely understand conversational English (Schmitt and Schmitt 2014). The first 1,000 words, including most of the English function words, afford a robust foundation providing an estimated high coverage of around 80 % of the words used in spoken language. An important caveat is that the test format used in the PVST, meaning-recognition, does not mean that young learners can use all the words they know receptively also productively.

Taking stock of the above benchmarking, even though comparisons are not straightforward due to the large number of factors that can vary across settings, the average performance of the Norwegian young learners is in some cases even on a par with somewhat older learners with several years of instructed learning. With increasing English instruction and continued extramural input, our Norwegian learners are in a good position to further build up their English vocabulary. When becoming literate in their L1 and drawing on transferable reading skills, the potential of also learning English through written input will further accelerate their vocabulary size (especially as the number of cognates across English and Norwegian is substantial). Generally, a requirement for this to take place is engagement (Schmitt 2008), whereby learners exhibit a positive attitude towards the language and its sociocultural manifestations. We will return to this topic in our discussion of obtained results for RQ2 and RQ3.

Our second observation based on our vocabulary results deals with variation. Even though the learners in our sample performed well on average, the average hides substantial fluctuation in scores. The lowest scoring learner in the sample knew as few as 3 out of 31 words, the equivalent of 50–100 word families, compared to the top scores of 25, the equivalent of around 1,500 word families. This distinct variation has been observed in previous studies with similarly aged children in Sweden (Sylvén 2022). The variation suggests very different levels of English exposure, as was seen in Figure 3 (number of EE sources), but likely also in combination with varying attitudes towards English. We will return to this later in this section. If the observed variation is generalisable, teachers in the lower years of primary school can expect a considerable spread of vocabulary knowledge amongst the children, something which is a challenge, since focusing too much on the low-proficiency learners may lead to loss of motivation for the high-proficiency learners, and naturally vice versa. Irrespectively, teachers must have an awareness of the fact that lots of learning can take place prior to the start of instructed learning, and develop strategies for how to best deal with these circumstances.

Turning next to RQ2, which asked to what extent there is a relation between children’s self-reported EE activities and parents’ reported EE activity for their child, and the child’s English word meaning recognition. Firstly, correlational analyses based on LDs showed that time spent on TV-watching and the total time spent on EE activities correlated significantly with PVST-S scores. The lack of significant correlation for gaming contrasts with prior studies. A possible reason could have to do with parental reporting biases; maybe it was easier for the parents to keep track of their child’s TV time exposure than their TV watching. In the absence of information on this, however, we can merely speculate as to resasons, and future studies should attempt to address such methodological challenges.

Interestingly, just like the vocabulary scores, the young learners’ time on EE activities displayed large variations in the sample. Based on a mixed-effects-model analysis, we found no effect for the young learners’ self-reported EE activities (EEQ) on vocabulary scores. There was an effect, however, of the parents’ reported EE activities (PQ) for their child. It can be mentioned that we had a perfect return rate of the PQs, which means our study does not suffer from a high rate of attrition of parental data, which was the case in some previous studies (e.g., Unsworth et al. 2015).

Since in earlier studies, effects on vocabulary have generally been found for EE activities (e.g. De Wilde and Eyckmans 2017; Hannibal Jensen 2017; Hubbe Emilsson 2021; but not Unsworth et al. 2015), what could be potential explanations for the absence of effects based on our EEQ index? One possibility could be the low number of items that were used (only three). This was done as to not place too much burden on the child, as other tests were administered as well. Another explanation could be a lack of correspondence between what the young learners reported and what their exposure actually looked like. There were indications of some students not knowing whether they were regularly watching TV in English, as they replied “do not know” in the EEQ. It is also possible that “TV” is an inappropriate term to use with children of today, since streamed media has replaced linear/regular TV in many homes. Thus, our participants may not have understood the “TV-question”. Despite attempts by the researcher to accommodate and paraphrase in the data collection situation, this begs the question whether the questionnaire is a suitable instrument for gathering data from this age group. Carrying out qualitative semi-structured interviews is likely a better method, where statements and questions can be explained and elaborated on if the young learner shows signs of not fully comprehending. Relatedly, the fact that there was an effect for the PQ index, which is more in line with results from previous studies, could mean that the parents’ reported exposure and EE activities for their child is likely a more valid indicator of “true” exposure. However, this is more speculation rather than evidence-based inferences, and there is no additional data to draw on. A more extensive set of questions could shed light on this issue, but as part of an interview as argued above.

In terms of gender effects on vocabulary scores, the boys in our study scored higher than the girls, whereas in previous studies no such differences were observed (Hannibal Jensen 2017; Hubbe Emilsson 2021). It could be that the difference is due to gendered EE preferences. Two of the highest scoring participants reported being avid gamers, and Hannibal Jensen (2017) did find that especially for boys playing digital games with both oral and written English input and gaming with only written English input were significantly related to PPVT-4TM vocabulary scores. By and large, the inconclusive role of gender merits further focus in future studies.

As the final part of our study, RQ3 targeted what characterizes young Norwegian learners’ perceptions about English and English language learning. The two themes that emerged in the content analysis of the interview data suggests that the eight participants generally see English as a lingua franca, and that English is a tool for communicating with people who do not know Norwegian. The role of English as a tool of communication is emphasized in the Norwegian subject curriculum reform from 2020 (Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training 2019). Rather than assuming that the young learners are familiar with the curricular aims, the participants’ perceptions suggest that the role of English as the world’s foremost lingua franca is well established in Norwegian society. Further, as to the learners’ perceptions about English language learning, the interviewees stated that they knew some English before starting school, but how, where and why this learning had taken place was relatively unclear, suggesting a rather organic presence of English in the everyday lives of young Norwegians.

The interview data also suggests that the participants primarily chose EE activities based on interests rather than on the fact that they often involved English (with the exception of English music). This is in line with findings in Hannibal Jensen (2019), where Danish children aged 7–11 similarly engaged extensively with English by token of their great interest in the activities. However, there was also evidence of the learners choosing YouTube material mediated in L2 English over their L1, and a perception of English experienced outside of school as more “more real” and “cooler.” This points to a positive identification with the language and its speakers, something that affects the motivation to learn and use the language (Dörnyei 2009). Similarly, experiences with the language supporting a learner’s sense of identity will likely spur more engagement and investment in learning (Norton 2013).

6 Conclusions

The participating young learners (M = 5.8 years) of English in Norway were observed to possess an average receptive meaning recognition vocabulary corresponding to around 850 word families. The level of knowledge observed occurred at the very onset of formal instruction when the participants had had approximately only six to ten lessons at the time of data collection. There was, however, a large variation in the sample. Correlational analyses based on language diaries covering one week from 2/3 of the sample showed that TV-watching and total time spent on EE activities were significantly correlated. Results regarding the relation between extramural English and receptive vocabulary knowledge were otherwise mixed as EE activities reported by the learners themselves were not correlated with their vocabulary scores, whereas activities reported by their parents and jointly filled out language diaries were. Interview data from a smaller subset of the young learners indicated that they viewed English as a lingua franca, but many showed limited grasp of English as a language and a concept. The interview data also pointed to the lack of straightforward relations between type of EE activities, perceptions about English learning, and vocabulary knowledge.

The implications of the study are that a budding large L2 English vocabulary can be expected in children prior to first grade instructed learning in input-rich settings like Norway. There will however very likely be a large variation amongst young learners, also in EE exposure. Teachers of English need strategies for dealing with both of these, and also approaches for bridging and synergizing young learners’ EE activities and the instructed learning in the classroom. For instance, detailed illustrations can be used to elicit a wider range of vocabulary, including words that teachers might not expect very young learners to know. Furthermore, authentic communication situations can be created in the classroom, where teachers draw on learners’ EE experiences (e.g., familiar characters from games or TV series) to develop new vocabulary (Rindal 2024).

Our study has some limitations. Although we collected data from 61 children, larger samples from the population of young learners are desirable, as is more extended use of qualitative interviews as a way to shed light on EE activities and attitudes to using English for the age group. Another limitation is the somewhat restricted information on details in the EEQ questionnaire used. Irrespective of these, we hope our study can inspire more studies of young learners of English around the globe. Future studies should consider using longitudinal data for mapping how EE exposure may influence development of language skills at a later stage. In addition, experimental designs could be used to investigate causal relationships between EE behaviour and foreign language proficiency.

Funding source: the Research Council of Norway

Award Identifier / Grant number: 314229

Funding source: The Research Foundation Flanders (FWO)

Award Identifier / Grant number: G052821N

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all school leaders, teachers, and students who opened not only their classroom doors to us but also generously participated in interviews; We also acknowledge the contribution of Elien Prophète at KU Leuven.

-

Research ethics: Ethical Approval by SIKT in Norway on 25 Sep 2023; Reference Number: 900288.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. CRediT author statement: HG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original draft preparation, Writing – Review and Editing, Visualization. PS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original draft preparation, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding Acquisition. EP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition. UR: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original draft preparation, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision. GS: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Review and Editing. NU: Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Original draft preparation, Writing – Review and Editing, Supervision.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: No such tools were used.

-

Conflict of interest: We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

-

Research funding: We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Research Council of Norway [grant number 314229] and The research Foundation Flanders (FWO) [grant number G052821N]: Project: STarting AGe and Extramural English: Learning English in and outside of school in Norway and Flanders (STAGE). We also acknowledge the contribution of Elien Prophète at KU Leuven.

-

Data availability: Data will be made available in a public repository (OSF).

The 31 words tested in the PVST-S, with frequency, cognateness information and item facility

| Item | Frequency band | PoS | (Near-) cognate to Norweigan | Item facility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ANIMAL | 1 | N | 0.85 | |

| 2. HOUSE | 1 | N | YES | 0.72 |

| 3. GRASS | 1 | N | YES | 0.79 |

| 4. AFRAID | 1 | A | 0.39 | |

| 5. KITE | 4 | N | 0.26 | |

| 6. LAKE | 1 | N | 0.20 | |

| 7. BEHIND | 1 | P | 0.21 | |

| 8. BENEATH | 1 | P | 0.25 | |

| 9. BEAST | 2 | N | YES | 0.48 |

| 10. BELIEVE | 1 | V | 0.51 | |

| 11. BREATH | 1 | N | 0.26 | |

| 12. LIQUID | 3 | A/N | 0.18 | |

| 13. SLOPPY | 5 | A | 0.39 | |

| 14. THIRTEEN | 1 | NUM | YES | 0.16 |

| 15. CREAM | 1 | N | 0.89 | |

| 16. HOTEL | 2 | N | YES | 0.44 |

| 17. LAUNDRY | 3 | N | 0.44 | |

| 18. WILD | 1 | A | YES | 0.54 |

| 19. SMUDGE | 6 | N | YES | 0.31 |

| 20. MESSAGE | 1 | N | 0.28 | |

| 21. ELECTRIC | 2 | A | YES | 0.34 |

| 22. ATTACK | 1 | N | 0.38 | |

| 23. BEEF | 3 | N | YES | 0.49 |

| 24. CALF | 3 | N | YES | 0.62 |

| 25. CHANT | 4 | V | 0.21 | |

| 26. SAG | 6 | V | 0.18 | |

| 27. WHIP | 2 | V | 0.23 | |

| 28. CAFETERIA | 4 | N | YES | 0.38 |

| 29. TOUR | 2 | N | YES | 0.28 |

| 30. HANDKERCHIEF | 2 | N | 0.43 | |

| 31. CANARY | 5 | N | YES | 0.07 |

Extramural English Questionnaire (EEQ)

B.1 Norwegian Version

Extramural English Questionnaire (EEQ)

B.2 English Version

Parental questionnaire (PQ)

C.1 Norwegian Version

SPØRRESKJEMA FOR FORELDRE/FORESATTE

Barnets for- og etternavn:…………………………………………………………….

For- og etternavn (foresatt 1):………………………………………………………….

For- og etternavn (foresatt 2):………………………………………………………….

Hvis barnet har to hjem, vil vi gjerne at begge foresatte fyller ut hvert sitt skjema. (Det er det samme om du fyller ut «foresatt 1» eller «foresatt 2».)

Nedenfor finner du 7 spørsmål som tillegg til spørsmålene barnet ditt har svart på på skolen. Svarene dine vil kun bli brukt i vår forskning, og navnet ditt vil ikke bli nevnt noe sted.

Hva er ditt høyeste utdanningsnivå?

Foresatt 1 Foresatt 2 Grunnskole □ □ Videregående skole □ □ Universitet/høyskole □ □ Annet □: …………………………………… □: …………………………………… Hva er yrket ditt?

Foresatt 1: ………………………………………………………………………….

Foresatt 2: ………………………………………………………………………….

Hva er morsmålet/morsmålene dine? Du kan sette flere kryss

Foresatt 1: ☐norsk ☐engelsk ☐annet/andre

(hvilke/t?):…………………………………

Foresatt 2: ☐norsk ☐engelsk ☐annet/andre

(hvilke/t?):…………………………………

Hvilket språk snakker du mest med barnet ditt? Sett kun ett kryss

Foresatt 1: ☐norsk ☐engelsk ☐annet

(hvilket?):…………………………………………….

Foresatt 2: ☐norsk ☐engelsk ☐annet

(hvilket?):…………………………………………….

Snakker du andre språk med barnet ditt? Du kan sette flere kryss

Foresatt 1: ☐norsk ☐engelsk ☐annet/andre

(hvilke/t?):…………………………………

Foresatt 2: ☐norsk ☐engelsk ☐annet/andre

(hvilke/t?):……………………………………

Hvilket kjønn er du? (sett ring)

Foresatt 1: mann kvinne annet vil ikke svare

Foresatt 2: mann kvinne annet vil ikke svare

Hvor ofte driver barnet ditt med følgende engelske aktiviteter?

(Nesten) aldri Hver måned Hver uke Et par ganger i uken Hver dag Se på TV eller videoer på engelsk (f.eks. YouTube, Netflix, TV, …) □ □ □ □ □ Bruke internett på engelsk □ □ □ □ □ Gaming på engelsk (f.eks. på PC, PlayStation, Xbox, …) □ □ □ □ □ Lytte til musikk på engelsk Andre hobbyer på engelsk:

………………………………………….

………………………………………….□ □ □ □ □ Takk for deltakelsen!

Takk for at du leverer spørreskjemaet til læreren sammen med samtykkeskjemaet!

Parental questionnaire (PQ)

C.2 English Version

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR PARENTS/GUARDIANS

Your child’s first and last name:…………………………………………………….

First and last name (guardian 1):…………………………………………………….

First and last name (guardian 2):…………………………………………………….

If the child has two homes, we kindly ask both guardians to each fill out their own form (you can choose if you want to select guardian 1 or 2 for yourself).

Below you will find 7 questions as an addition to the questions your child has answered at school. Your answers will only be used for our research, and your name will not be published anywhere.

What is your highest education level?

Guardian 1 Guardian 2 Elementary school □ □ High school/upper secondary school □ □ University □ □ Other □: …………………………………… □: …………………………………… What is your occupation?

Guardian 1: ……………………………………………………………………….

Guardian 2: ……………………………………………………………………….

What is/are your first language(s)? You can cross off the relevant alternatives below.

Guardian 1: ☐Norwegian ☐English ☐Other (which?):…………….

Guardian 2: ☐Norwegian ☐English ☐Other (which?):…………….

What language do you speak most with your child? Only cross off one alternative

Guardian 1: ☐Norwegian ☐English ☐Other (which?):…………….

Guardian 2: ☐Norwegian ☐English ☐Other (which?):…………….

Do you speak other languages with your child? You can cross off several alternatives

Guardian 1: ☐Norwegian ☐English ☐Other (which?):…………….

Guardian 2: ☐Norwegian ☐English ☐Other (which?):…………….

What is your gender? (Mark with a circle)

Guardian 1: male female other do not want to answer

Guardian 2: male female other do not want to answer

How often does your child do the following activities in English?

(Almost) never Every month Every week A few days a week Every day Watch TV or videos in English (f.ex. YouTube, Netflix, TV, …) □ □ □ □ □ Use the internet in English □ □ □ □ □ Gaming in English (f.ex. on PC, PlayStation, Xbox, …) □ □ □ □ □ Listen to English music Other hobbies in English:

………………………………………….

………………………………………….□ □ □ □ □ Thank you for your participation!

Thank you for handing in this questionnaire together with the consent form!

Language diary (LD) Excerpt

D.1 Norwegian Version (Excerpt for Monday)

D.2 English Version (Excerpt for Monday) (lacking illustrations)

Example PVST-S Item

English target word: shell

With ‘key’, three ‘distractors’ and an ‘I do not know’ answer option

References

Anthony, Laurence & Paul Nation. 2017. Picture Vocabulary Size Test (Version 1.2.0) [Computer software and measurement instrument]. Waseda University. Available at: http://www.laurenceanthony.net/software/pvst.Suche in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48.10.18637/jss.v067.i01Suche in Google Scholar

Braun, Virginia & Victoria Clarke. 2022. Thematic analysis: A practical guide. London: SAGE.10.53841/bpsqmip.2022.1.33.46Suche in Google Scholar

Council of Europe. 2020. Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages.Suche in Google Scholar

De Wilde, Vanessa, Marc Brysbaert & June Eyckmans. 2020a. Learning English through out-of-school exposure. Which levels of language proficiency are attained and which types of input are important? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23(1). 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918001062.Suche in Google Scholar

De Wilde, Vanessa, Marc Brysbaert & June Eyckmans. 2020b. Learning English through out-of-school exposure: How do word-related variables and proficiency influence receptive vocabulary learning? Language Learning 70(2). 349–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12380.Suche in Google Scholar

De Wilde, Vanessa & June Eyckmans. 2017. Game on! Young learners’ incidental language learning of English prior to instruction. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 7(4). 673–694.10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.4.6Suche in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltan. 2009. The L2 motivational self system. In Zoltan Dörnyei & Emma Ushioda (eds.), Motivation, language identity, and the L2 self, 9–42. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.2307/jj.30945943.5Suche in Google Scholar

Dunn, Lloyd & Douglas Dunn. 2007. Peabody picture vocabulary test manual (PPVT™-4), 4th edn. Pearson. Available at: http://www.pearsonclinical.com.10.1037/t15144-000Suche in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick. 1994. Implicit and explicit language learning - An overview. In Nick Ellis (ed.), Implicit and explicit learning of languages, 1–31. London: Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Enever, Janet (ed.). 2011. ELLiE: Early language learning in Europe. London: British Council. Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/publications/case-studies-insights-and-research/ellie-early-language-learning-europe.Suche in Google Scholar

Fredricks, Jennifer A., Phyllis C. Blumenfeld & Alison Paris. 2004. School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research 74(1). 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059.Suche in Google Scholar

Gyllstad, Henrik. 2013. Looking at L2 vocabulary knowledge dimensions from an assessment perspective: Challenges and potential solutions. In Camilla Bardel, Christina Lindqvist & Batia Laufer (eds.), L2 vocabulary acquisition, knowledge and use. New perspectives on assessment and corpus analysis, 11–28. Eurosla Monograph Series 2. European Second Language Association.Suche in Google Scholar

Gyllstad, Henrik, Laura Vilkaitė & Norbert Schmitt. 2015. Assessing vocabulary size through multiple-choice formats: Issues with guessing and sampling rates. ITL - International Journal of Applied Linguistics 166(2). 278–306. https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.166.2.04gyl.Suche in Google Scholar

Hannibal Jensen, Signe. 2017. Gaming as an English language learning resource among young children in Denmark. CALICO Journal 34(1). 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.29519.Suche in Google Scholar

Hannibal Jensen, Signe. 2019. Language learning in the wild: A young user perspective. Language Learning & Technology 23(1). 72–86.Suche in Google Scholar

Hubbe Emilsson, Karin. 2021. The relationship between extramural English exposure and receptive vocabulary knowledge of young Swedish L2 learners of English. Unpublished BA Thesis. Lund University, Sweden.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiménez Catalán, Rosa Mária & Mellania Terrazas Gallego. 2008. The receptive vocabulary of English foreign language young learners. Journal of English Studies 5–6. 173–191. https://doi.org/10.18172/jes.127.Suche in Google Scholar

Kavanoz, Suzan & Burcu Varol. 2019. Measuring receptive vocabulary knowledge of young learners of English. Porta Linguarum 32. 7–22. https://doi.org/10.30827/pl.v0i32.13677.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuperman, Viktor, Hans Stadthagen-Gonzalez & Marc Brysbaert. 2012. Age-of-acquisition ratings for 30,000 English words. Behavior Research Methods 44(4). 978–990.10.3758/s13428-012-0210-4Suche in Google Scholar

Kuppens, An. H. 2010. Incidental foreign language acquisition from media exposure. Learning, Media and Technology 35(1). 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880903561876.Suche in Google Scholar

Kusyk, Meryl, Henriette Arndt, Marlene Schwarz, Kossi Seto Yibokou, Mark Dressman, Geoffrey Sockett & Denyze Toffoli. 2025. A scoping review of studies in informal second language learning: Trends in research published between 2000 and 2020. System 130. 103541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103541.Suche in Google Scholar

Larsson, Karolina, Polly Björk-Willén, Katarina Haraldsson & Kristina Hansson. 2023. Children’s use of English as lingua franca in Swedish preschools. Multilingua 42(4). 527–557. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2022-0062.Suche in Google Scholar

Lázaro-Ibarrola, Amparo. 2024. What factors contribute to the proficiency of young EFL learners in primary school? Assessing the role of CLIL intensity, extramural English, non-verbal intelligence and socioeconomic status. Language Teaching Research 0(0). 13621688241292277. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241292277.Suche in Google Scholar

Lefever, Sámuel. 2010. Incidental foreign language learning in children. In Angela Hasselgreen, Ion Drew & Bjørn Sørheim (eds.), The young language learner: Research-based insights into teaching and learning, 87–100. Oslo: Fagbokforlaget.Suche in Google Scholar

Levenshtein, Vladimir. 1966. Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions and reversals. Soviet Physics Doklady 10(8). 707–710. [Russian original (1965) in Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR 163(4). 845–848.].Suche in Google Scholar

Linck, Jared & Ian Cunnings. 2015. The utility and application of mixed‐effects models in second language research. Language Learning 65(S1). 185–207.10.1111/lang.12117Suche in Google Scholar

Lindgren, Eva & Carmen Muñoz. 2013. The influence of exposure, parents, and linguistic distance on young European learners’ foreign language comprehension. International Journal of Multilingualism 10(1). 105–129.10.1080/14790718.2012.679275Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Linlin, Ju Seong Lee, Wen Juan Guan & Yefeng Qiu. 2024. Effects of extramural English activities on willingness to communicate: The role of teacher support for Chinese EFL students. System. 103319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103319.Suche in Google Scholar

McKay, Penny. 2006. Assessing young language learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511733093Suche in Google Scholar

Meara, Paul. 1996. The dimensions of lexical competence. In Gillian Brown, Kerstin Malmkjaer & John Williams (eds.), Performance and competence in second language acquisition, 35–53. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Mercer, Sara. 2019. Language learner engagement: Setting the scene. In Second Handbook of English Language Teaching, 643–660. Cham: Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_40Suche in Google Scholar

Ministry of Church Affairs Education and Research. 1996. Læreplanverket for den 10-årige grunnskolen [Curriculum for 10-year comprehensive school]. Oslo: Ministry of Education and Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Miralpeix, Imma. 2020. L1 and L2 vocabulary size and growth. In Stuart Webb (ed.), The Routledge handbook of vocabulary studies, 189–206. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429291586-13Suche in Google Scholar

Nation, Paul. 2016. Making and using word lists for language learning and testing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/z.208Suche in Google Scholar

Nation, Paul & Rob Waring. 1997. Vocabulary size, text coverage and word lists. In Norbert Schmitt & Michael McCarthy (eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy, 6–19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Norton, Bonny. 2013. Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783090563Suche in Google Scholar

Norwegian Directorate for Edcuation and Training. 2024. Available at: https://www.udir.no/regelverkstolkninger/opplaring/Innhold-i-opplaringen/udir-1-2024/.Suche in Google Scholar

Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training. 2019. Curriculum in English (ENG01-04). Available at: https://www.udir.no/lk20/eng01-04?lang=eng.Suche in Google Scholar

Norwegian Media Authority. 2020. Young children and digital devices – A good start. Available at: https://www.medietilsynet.no/digitale-medier/barn-og-medier/smabarn-og-skjermbruk/.Suche in Google Scholar

Pellicer-Sánchez, Ana & Norbert Schmitt. 2010. Incidental vocabulary acquisition from an authentic novel: Do “Things Fall Apart”? Reading in a Foreign Language 22(1). 31–55.Suche in Google Scholar

Peters, Elke, Ann-Sophie Noreillie, Kris Heylen, Bram Bulté & Piet Desmet. 2019. The impact of instruction and out-of-school exposure to foreign language input on learners’ vocabulary knowledge in two languages. Language Learning 69(3). 747–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12351.Suche in Google Scholar

Puimège, Eva & Elke Peters. 2019. Learners’ English vocabulary knowledge prior to formal instruction: The role of learner-related and word-related factors. Language Learning 69(4). 943–977. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12364.Suche in Google Scholar

R Core Team. 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.1.2) [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.r-project.org.Suche in Google Scholar

Rindal, Ulrikke. 2024. Engelskundervisning med hånddukken Lucy [English teaching with Lucy the hand puppet]. Bedre Skole 1. 39–43.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Norbert. 2008. Review article: Instructed second language learning. Language Teaching Research 12(3). 329–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168808089921.Suche in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Norbert. 2010. Researching vocabulary: A vocabulary research manual. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230293977Suche in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Norbert & Dianne Schmitt. 2014. A reassessment of frequency and vocabulary size in L2 vocabulary teaching. Language Teaching 47(4). 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444812000018.Suche in Google Scholar