Abstract

A global push to start learning English early has heightened interest in effective pedagogical practices for young learners. In many parts of the world, however, teachers feel constrained by the educational system in which they work. Coursebooks are mandated, tests and examinations dominate, and teacher education may not consider the particularities of teaching young learners. Such factors have all been identified in Vietnam, where this study was conducted. A storytelling innovation based on coursebook texts was introduced and taught for one school term. Pre- and post-tests of speaking found that learners who experienced the storytelling innovation significantly outperformed the learners who followed the textbook when measured by English tokens, English types, idea units in English, and idea units in English and Vietnamese. The study demonstrates how a relatively modest course book adaptation can lead to improved learning outcomes in an EFL context where change is often considered difficult to achieve.

1 Introduction

Over the past twenty or thirty years, teaching English to young learners (TEYL) has become a well-established field of research in applied linguistics and education. Its growth can be seen as a response to globalisation, and the role of English as a global lingua franca (Rich 2014). Governments promote English language learning in schools as a way of serving the national interest. Parents want their children to learn English for reasons of economic advantage and social mobility. Beginning to learn at a young age is supported, at least popularly, by the belief that children learn languages more easily than older learners. “To many politicians and their public,” as Rixon (2015) notes, TEYL seems “an uncontroversially desirable proposition”.

Vietnam has not been immune to these global trends. In 2008 the government formalised English language learning in primary schools, with English being introduced in Grade 3, or at around 8 years of age. Teachers were expected to be at CEFR B2 and learners to have reached A1 by the end of primary education (Grade 5). However, a range of factors militate against achieving these language goals and include inappropriate teacher education programmes, a lack of English language proficiency, being professionally isolated, maintaining a traditional textbook-driven focus, and not using young learner appropriate pedagogy (Le and Do 2012). There is, of course, great diversity within Vietnam and these factors operate more strongly in rural than urban settings, and in the public rather than the private sector. Furthermore, the situation in Vietnam is not unique as Rixon (2015) made clear in her discussion of the critical issues around TEYL in Outer and Expanding Circle countries.

In order to achieve the language learning targets mentioned above, effective ways of working with current teachers and textbooks need to be found. Any textbook adaptation needs to draw on TEYL pedagogical principles and to be feasible for teachers in their context for, as Le and Do (2012, p. 119) highlight, “the learning culture of Vietnam […] is textbook-centred and teachers have very limited methodological repertoires”. Further, any adaptation should result in improved language learning outcomes. That is the goal of this article. It investigates a storytelling innovation based on a short text in a required textbook and its impact on speaking proficiency in a Grade 5 classroom in provincial Vietnam. In doing so, it demonstrates the importance of research-informed practice in the classroom, the absence of which is periodically lamented (Nation 2018).

2 Storytelling

People tell stories. Stories can be heard everywhere – in news reports, in songs, in religious texts, and in everyday conversations. In education, stories and storytelling have been recognized as powerful tools in the development of language skills in first and also foreign or second language learning, regardless of the learners’ age or background (Cameron 2001). Storytelling is a methodological approach in which learning is structured around a story as a means of sense making. This aligns with the need to provide quantities of comprehensible input to learners (Krashen 1985), a necessary condition for language acquisition. It also aligns with the need to provide opportunities for output, as stories and their re-enactment are “valuable strategies for the development of spoken language and literacy within early years and elementary classrooms” (Cremin et al. 2017, p. 1).

Unsurprisingly, then, the use of storytelling is frequently incorporated into different pedagogical approaches. For example, the natural approach embraces stories as a key source of input (Krashen and Terrell 1995). Don Holdaway developed this into the Natural Learning Model (Park 1982) which is based on the belief that children can learn how to read by experiencing the texts in storybooks over and over and, through these experiences, acquire the language. His shared book reading approach has been applied with great success, such as in the Fiji Book Flood experiment (Elley and Mangubhai 1983), but has also been challenged with the result that phonics instruction typically integrates with storytelling in current approaches. Nevertheless, storytelling has survived the pendulum shifts in pedagogy. It is compatible with communicative language teaching (Ellis and Brewster 2014; Wright 1995) because the main focus of storytelling is to set up life-like situations in which students communicate meaningfully and the primary focus of storytelling is on the meaning and the construction of stories; it has in fact been defined “as a broader version of the communicative approach” (Ellis 1995, p. 89). Furthermore, storytelling fits with the task-based approach as “[t]asks provide a framework for storytelling which can be manipulated by the task designer or teacher to both support and challenge the learner” (Kiernan 2005, p. 59). The two perspectives of task-based storytelling reflect the input/output distinction. One considers that students interactively listening to and joining the teacher telling the story is the main task and the other considers students telling the story to be the main task.

It is worth noting that in the literature ‘storytelling’ is used to cover both oral telling and the reading of texts, as in the shared book approach mentioned above. Oral storytelling requires the teacher to be the storyteller, and may best be suited to pre-literate learners, or learners who are not yet fluent readers (Bland 2015). Reading texts may make use of picturebooks (Mourão 2015) or of what Linse (2007) calls ‘predictable books’, books written for native speakers. Common to all these is the use of formulaic language, the acquisition of which can contribute to language development and to more fluent language processing (Kersten 2015).

Regardless of how it is understood, storytelling has support from different theoretical perspectives, and various frameworks for constructing a storytelling lesson have been proposed. All frameworks employ a holistic approach to teaching and learning and create classroom conditions in which the learners are involved “in dealing with different aspects of the language in the way language is normally used” (Samuda and Bygate 2008, p. 7). The approach focuses on meaning, not correction, on the outcome of the activity, not on the language or discrete language items, on collaboration and social development (Peck 2001). The approach integrates the four skills and provides the learner with the linguistic and intellectual immersion necessary for language acquisition to take place.

2.1 Benefits of stories and storytelling

Storytelling have been shown to contribute to the development of linguistic skills for young learners in an EFL environment, including vocabulary (Gomez 2010; Kirsch 2016; Soe 2016), grammar (Garcia 2017; Kalantari and Hashemian 2016) and pronunciation (Lucarevschi 2018). As an example, Kalantari and Hashemian (2016) performed an intervention study on the effectiveness of storytelling on Iranian young learners’ vocabulary and attitudes. They compared a regular class with lessons based on the Backpack textbook and an intervention class with storytelling lessons based on the textbook prepared by the teachers and the researcher. The teachers used storytelling with pre-, while- and post-activities. Before reading the stories, the participants received interesting and comprehensible input through the teacher’s talk, games, reading and listening activities which familiarized them with the new language and vocabulary. While reading the story, the teacher directed the participants’ attention to a PowerPoint presentation which included the visual representation of the story to facilitate comprehension. In the post-storytelling stage, the teacher played vocabulary games with the participants and asked them to role-play the story by memorizing the dialogue. To assess the students’ improvement, a vocabulary pre- and post-test was conducted. The results showed that the intervention group experienced a significant increase in their vocabulary knowledge, compared to the comparison group. In addition, they become more motivated in learning with storytelling. However, it is worth noting that the intervention group received more and richer input than the comparison class.

Other studies report that storytelling can develop specific sets of skills, such as reading comprehension, critical reading (Belet and Dala 2010), listening (Oduolowu and Oluwakemi 2014), speaking (Fikriah 2016) and writing (Alkaaf and Al-Bulushi 2017). Gupta (2009) reported that storytelling plays an important role in the development of language skills by promoting social interaction and mutual collaboration, as storytelling encourages learners to interact with the teachers and their classmates by listening and telling stories to each other, thus providing opportunities to receive support from their teachers and their classmates.

Kim (2013) used classroom observations and teacher interviews to compare Korean elementary students’ interactions in task-based lessons and storytelling-based lessons. The findings indicate that interaction patterns for task-based lessons and storytelling-based lessons were different. In task-based lessons, some pitfalls were found such as spending time explaining how to perform a task, mainly using low-level lessons, and frequent use of native language. The frequency of students’ interaction was significantly higher in the storytelling classrooms. The overall process of the storytelling lessons provided students with opportunities for dynamic interactions in the classroom, while in the task-based lessons, the teacher and students talked more in their native language. Kim (2013) also suggests that the storytelling approach was more efficient in developing vocabulary, background knowledge and skills due to the enjoyment created in story-based lessons.

In terms of oral production, the focus of this paper, Li and Seedhouse (2010) investigated the role of storytelling in the development of oral interaction in primary Taiwanese EFL classes. They compared learners’ interactions in standard classes with textbook support (including choral drills, task-based activities and playing games) and storytelling classes (including talking about characters, prediction, storytelling, story discussion and pupils retelling the story). The researchers found there was an increase in oral interactions, vocabulary and expressions of different language functions among students in storytelling lessons as the story-based approach created an entertaining environment, causing a higher level of motivation and engagement from students. Li and Seedhouse (2010) suggest storytelling as an effective tool for promoting social interactions and, through interaction, improving their language skills.

However, Chwo and Chen’s (2015) found that storytelling was not very effective. This study had a large population of 40 classes including 1,036 primary school learners, from 10 schools, lasting 34 weeks. In the intervention group, the students, in addition to their normal English classes, had a daily 10‒15-min storytelling session led by the general class teacher who played a CD of an English story being read aloud, with no attendant preparation or associated activities. Occasionally, foreign English teachers told a story in person in a 40-min session with pre-, while- and post- activities. Students also read and listened to stories from magazines. The comparison group had normal reading and listening input and they could borrow magazines to read and listen to outside the classroom. Results showed many favourable attitudes, together with considerable gains between pre- and post-tests of reading and listening, but interestingly no overall significant difference between the score improvements in the storytelling classes and those in the comparison classes. The unsuccessful storytelling may be due to two reasons. The first is that it was not clear whether the students listened to the stories during the daily 10–15 min storytelling sessions conducted by the general teachers. They did not have any reason for listening to the stories and it was not clear how the students interacted with the story. The second reason was that they did not have any interactions after listening to the story to use what they had learned. The children had exposure to many stories, but they did not interact with the story or with friends to construct meaning and to use the language. McGee and Schickedanz (2007) suggest that just exposing children to stories is not enough to develop language and cognitive skills through storytelling. Storytelling should include activities planned around specific learning outcomes and the story serves as the reference point for teaching cognitive and linguistic skills.

Although the studies explore the effects of storytelling in different areas, a common feature across their findings is that storytelling positively influences motivation, language knowledge and language skills for young learners. Most studies report the positive effects on learners’ motivation and interest in English classrooms. The use of stories encourages learners to actively participate in the learning process by not only listening to stories but also discussing them and telling their own stories. The students enjoy the meaningfulness of the story and its creative activities. A significant finding from the empirical studies is that interaction plays an important role in storytelling lessons for language learning development.

2.2 The Vietnamese context

Despite the theoretical and research support for the use of storytelling that emerges from the literature, its use in classrooms is far from universal. As noted earlier, Vietnam has ambitious goals for English language learning and teaching but faces challenges in achieving them (Le and Do 2012). The challenges vary depending on context. Le and Barnard (2009), for instance, investigated the introduction of communicative language teaching in a rural public secondary school and found that even when the teacher attempted a small innovation, such as group work, learners did not change their behaviour; they worked individually and silently. On the other hand, however, Nguyen et al. (2018) reported successful transformation of textbook activities applying task-based learning principles in an urban private secondary school. Bui and Newton (2021) also found the potential for TBLT in the adaptations of PPP among a select group of primary teachers, but as they themselves noted these teachers were not ‘typical’. Among the constraints innovation in English language education face are the dominance of the textbook, the demands of assessment, and teachers’ own proficiency. A further issue, again not restricted to Vietnam, is the history of top-down directives in education and the lack of involvement of teachers in formulating policy and guidelines (Enever 2020). In the context of this article, a background study (Le 2020) indicated that teachers had to use the textbook, and that although the textbooks contained stories the quality of the texts was insufficiently interesting; that the stories were not employed to provide effective learning opportunities for young learners; and that student engagement was low. The challenge, therefore, was how to find a way to work both within and against the existing constraints so that learners could benefit from storytelling.

2.3 Research question

Studies on storytelling are popularly conducted in countries where the curriculum allows teachers to choose their own materials and teaching methods or where their textbooks were designed with stories and interactive storytelling. They had freedom to choose storybooks and create stories that were suitable for the students’ interests, proficiency levels, and age or were supported with storybooks and by the authorities. In countries such as Vietnam, on the other hand, it can be a challenge to find this curriculum space or opportunities for the exercise of teacher agency. Thus, there is a need for more empirical research on effective innovation in resource poor EFL environments where teaching is strictly regulated, and textbooks are considered to be the curriculum. If an innovation, such as storytelling, can be demonstrated to be successful and feasible, it creates the opportunity for positive change. The question that guided this study, then, was:

What was the effect of the storytelling innovation on young EFL learners’ spoken language performance?

3 Methodology

3.1 Context and participants

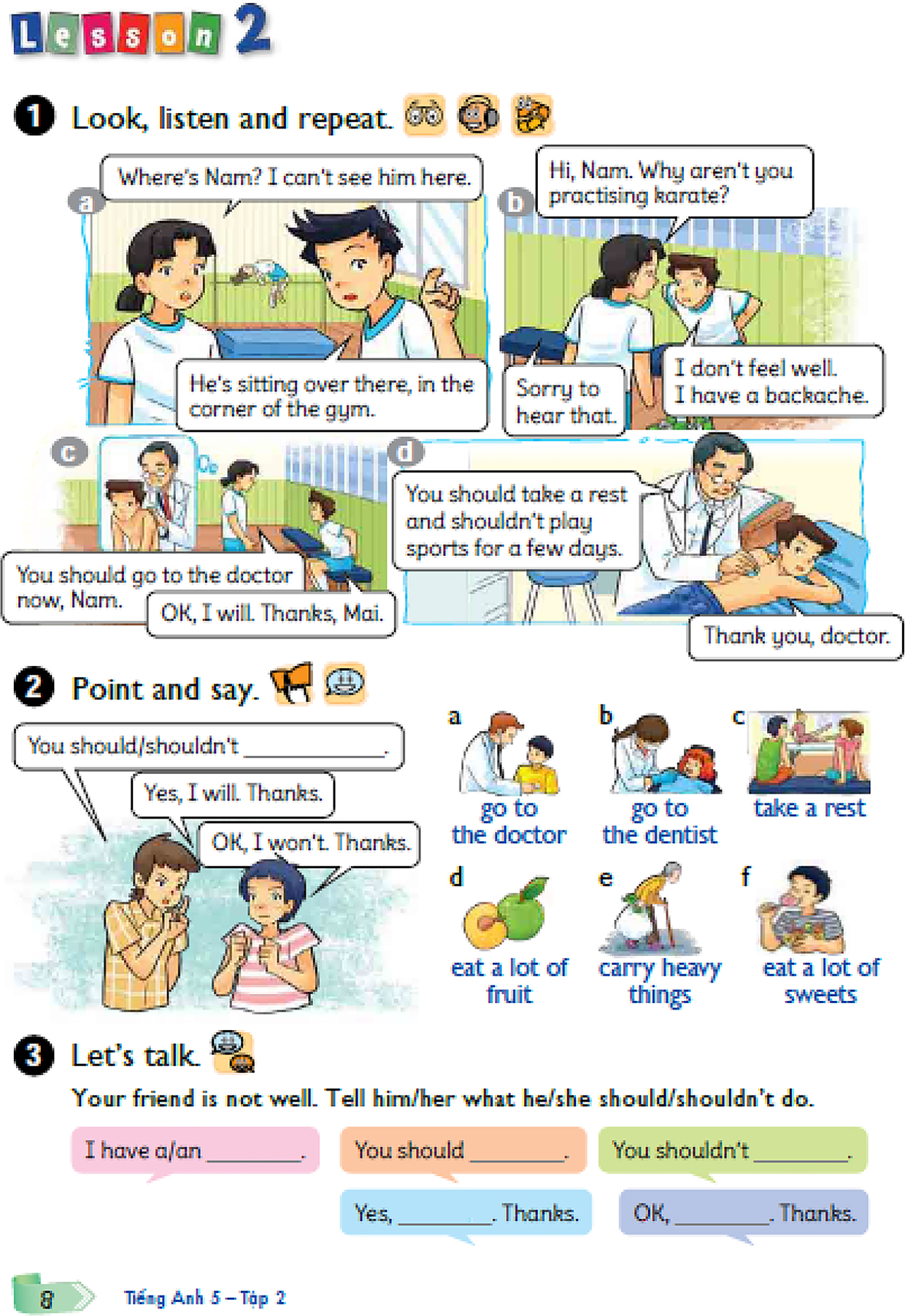

This study was conducted in an urban primary school in southern Vietnam. This school had six Grade 5 classes and two of these classes, each with 46 students, joined the study. English was taught for four periods a week using the Tieng Anh textbook. The coursebook had ten units and two review units, with each unit consisting of three lessons, and each lesson of six sections. One coursebook lesson was taught over two classroom lessons, with the storytelling innovation being based on the three sections of one lesson (Appendix A) and occupying one classroom lesson. Over the 15 weeks of the study, the intervention class had the storytelling innovation for 22 lessons, while the comparison class covered the same material following the textbook.

Both teachers had similar backgrounds. They attended the same three-year course at college. Since graduation, they had been teaching at primary schools and together in the same school for over four years. Both had achieved the B2 certificate of English proficiency and attended a 180-h workshop on TEYL and textbook training workshops. They were in the same professional learning group. Together with teaching normal classes, both had been working as teaching assistants for foreign teachers.

3.2 A storytelling innovation

Adaptation of existing materials was undertaken to create the storytelling innovation (Macalister 2016). The format and presentation of the textbook speaking lessons were redesigned into storytelling lessons to offer interactive opportunities for young learners to use language (see Appendix A for an example of a textbook story). A story was created by adding some short sentences to provide the setting and the characters. In the Appendix A example, for instance, in telling the story the teacher began by saying “Mai and Quan were at a gym”, thus establishing the setting. Instead of asking students to ‘Look, listen and repeat’ as instructed in the textbook, the teacher told the story, using the pictures without showing the words. Table 1 presents the structure of a storytelling innovation lesson.

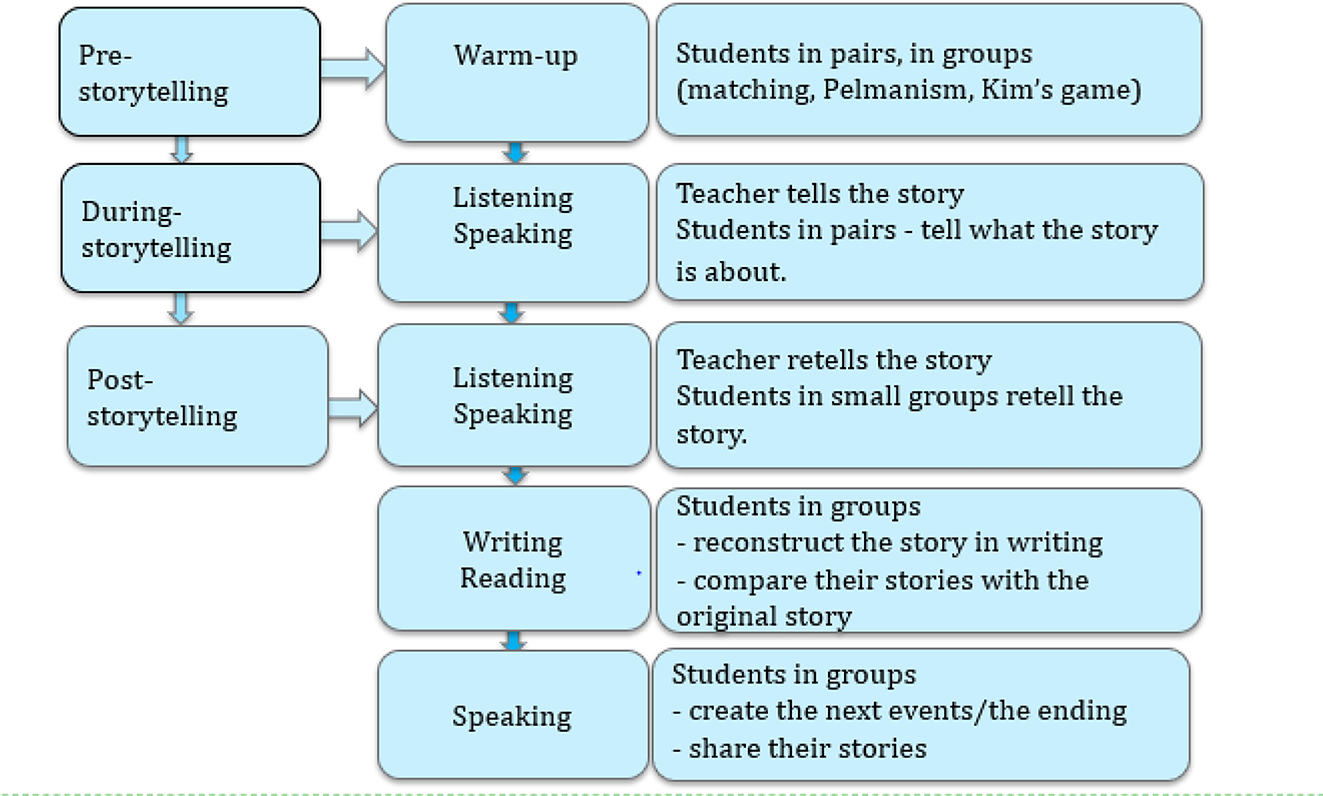

Structure of a storytelling innovation lesson.

The lesson structure consists of three phases: pre-, during- and post activities. It is an integrated skills lesson with a focus on speaking and it has five main activities. In the first activity, students in groups or pairs join in a fun and engaging game. In the second activity, the teacher tells the story, pointing to the pictures (without showing the text), or using body language. Students are asked to work in pairs to tell what the story is about. In the third activity, the teacher retells the story (similar to Activity 1). Students retell the story in small groups. In the fourth activity, students retell the story in writing and compare their group’s story with the original. In the fifth activity, students are required to make the next events of the story (the ending of the story) and retell the story with their own endings.

3.3 Data generation

The storytelling innovation was used regularly in class for one term, while the comparison class followed the textbook as usual. Pre- and post-tests were conducted at the start and end of term. The tests involved learners retelling the story of a cartoon story they had just seen.

After piloting, two cartoon stories, Little Red Riding Hood (LRRH) and Tom and Jerry (T&J), were used in the story retelling. The students were randomly put in the subgroups. Thirty-one students in each class participated in the retellings and were divided into four subgroups depending on which stories they were exposed to in the pre- and post-tests (Table 2). However, six students in the comparison group and one student in the intervention group were removed from the analysis because they did not supply enough data. Two of the children in the comparison group watched the cartoon but refused to say anything in the pre-test and post-test; one of the comparison group children moved to another school towards the end of the second semester; and two of the students in the comparison group and one in the intervention group did not say anything after watching the cartoon in the pre-test but they did tell the story in the post-test. Therefore, the data of story retelling for analysis were from participants of 25 students in the comparison group and 30 in the intervention group.

Subgroups and numbers of students.

| Subgroups | Comparison group | Intervention group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of students | Pre-test | Post-test | No. of students | Pre-test | Post-test | |

| Subgroup 1 | 4 | LRRH | T&J | 9 | LRRH | T&J |

| Subgroup 2 | 6 | T&J | LRRH | 7 | T&J | LRRH |

| Subgroup 3 | 8 | T&J | T&J | 8 | T&J | T&J |

| Subgroup 4 | 7 | LRRH | LRRH | 6 | LRRH | LRRH |

3.4 Story retelling test procedure

Pre- and post-storytelling tests were conducted in the staff room and the corridor in front of the staff room where it was quiet. One of the second author’s colleagues managed the cartoon watching. Her assistance reduced their time out of the classroom. She explained what the students would do, did a short modelling demonstration using the cartoon Three Little Pigs and a series of pictures from it, and invited them to watch a cartoon. Two learners watched a cartoon together which helped increase their enjoyment. They had time to prepare their retold story individually. Each of them then took turns to retell their stories to the second author, who listened and audiorecorded them. The story retelling task was not timed, and the participant students were free to retell the story in as much detail as possible. They were also encouraged to use English as much as possible. No comments on the children’s story retellings were revealed to the children or their teachers and parents to minimize external threat.

3.5 Story retelling data analysis

Lexical richness and idea units were used to analyse the participants’ language. Lexical richness is about the quality of vocabulary in a language text, and it is popularly employed to measure the proficiency level of a student. Educators (Laufer and Nation 1995; Read 2000) have suggested different models to measure lexical richness. The oldest and the most frequently used measure of lexical richness is based on the type-token ratio, which is generally concerned with counting how many different tokens there are for each type in a text (Van Hout and Vermeer 2007). However, in the current study, the students’ English proficiency in their story retellings was at a low level. Most of the students were less proficient English speakers, so they spoke in English and Vietnamese in story retellings. Only a few proficient students spoke completely in English. In this study, tokens and types were counted but no ratio was taken.

For the analysis, the independent variables were the normal lessons for the comparison group and the storytelling lessons for the treatment group and dependent variables were the outcomes of the students’ pre-test and post-test story retellings. Tokens, English types and idea units in the students’ retold stories were analysed to examine their central tendencies and degrees of deviation to measure the language development within the participating groups and between them. Because the data were collected from mixed-ability classes, preliminary analyses of the data were performed to examine their normality, homogeneity of variance and outliers in order to choose precise statistical tests. The results of Shapiro-Wilks tests demonstrated violations of normal distribution and box-plots showed some outliers, while Levene tests showed the data had equal variances. Following advice from a statistical consultant, medians (not means) were determined to be better measures of the centres of the data and Wilcoxon signed rank and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to determine whether the differences of story retelling measurements within and between the comparison group and the intervention group were statistically significant. In addition, their size effects were also calculated on the formulas recommended by Clark Carter and Cohen (cited in Allen et al. 2014, pp. 257–259). All the tests were computed with SPSS 25, a statistical software programme.

In addition to counting tokens and types, idea units were also counted to measure the amount of ideas in a text. Idea units have been shown as a useful measure of oral speech, especially narratives (Brenes 2005; Gee 1991, 2018).

3.6 Data transcription

For each of the students’ story retellings, two versions were created. In the first version, everything was transcribed verbatim. The only changes made were when the students pronounced words with mistakes in final sounds. For example, if they pronounced “mouse” as [mau], it was transcribed as a full word [maus]. Grammatical mistakes were not corrected as in the example “the mother cook soup”. In the second version, all fillers like “umm” and “ủa” (oops), and unclear words were omitted, and some changes were made based on notes in counting tokens (see Appendix B). The two versions were saved as.txt documents, and the latter version was used for data analysis. The story retellings were analysed in relation to the number of tokens and English tokens, English types and idea units.

3.7 Tokens in students’ stories

A token is an individual occurrence of a linguistic unit in speech or in writing. In other words, tokens are the total number of words in a text, regardless of how often they are repeated. Tokens reflect the speakers’ language use. In this study, there were two types of tokens in the students’ stories: tokens in English and tokens in Vietnamese. For example, in “On the street cô bé quàng khăn đỏ gặp one wolf and then cô bé nói là đang đi đến grandmother home”, there are 22 tokens, consisting of nine English tokens and 13 Vietnamese tokens.

3.7.1 Possible influence of title character names in tokens

The title character names in English or in Vietnamese might influence the sum of tokens and the central tendency of tokens (the central value for the distribution of tokens). T&J cartoons are popular in Vietnam and Vietnamese people do not have different names for the main characters; therefore, children in Vietnamese also call them Tom and Jerry. These were counted as English tokens. Most of the students used the names in their stories; only six students in the pre-test and four students in the post-test used nouns and pronouns instead of the proper nouns in English. As a result, some students told the story completely in Vietnamese with the English title names Tom and Jerry; therefore, their stories had some English tokens. The prevailing use of Tom and Jerry might increase the number of English tokens.

LRRH is a very popular story in Vietnam. There is a Vietnamese version with a Vietnamese equivalent name for the title character: Co Be Quang Khan Đo. Most school children in Vietnam know this story well because it is included in the official textbook for studying Vietnamese in state primary schools. Rather than using English proper names when telling stories, the familiarity of the LRRH story could lead to the adoption of Vietnamese character names in retold stories, which might influence the total number and the central tendency of tokens.

In the students’ stories, there were English tokens in some T&J stories but there were no English tokens in some LRRH stories because of the difference in using the title character names. Take one student who told LRRH in the pre-test and T&J in the post-test as an example. Her LRRH story was in Vietnamese with Vietnamese title character names, her story had no English tokens. Her T&J story was also in Vietnamese with the title character names Tom and Jerry, so this story had some English tokens. However, it would be misleading to conclude that her English had improved.

Furthermore, if the students used a lot of title character names, they might produce longer stories as Little Red Riding Hood and the Vietnamese title character Co Be Quang Khan Đo had more words than Tom and Jerry or the nouns such as “the dog” or “the cat” or the pronouns used to refer to the characters. To avoid being misleading, the sum of tokens and the average tokens with and without the title character names will be presented below to give a clear picture of the students’ language production.

3.8 Counting tokens and types

Here is an example of a student’s retold story.

The mouse is go the mouse get up at night, and he open the door, and go outside, he see a bag in the river, he open the bag, and he see many dogs in the bag, one dog is lick the mouse, the dogs and a mouse go, the dogs and a mouse go to the house, and the cat see the dog, and he is very angry, the dogs and the cat was in the bed, the cat the mouse cooking soup, and he đổ soup vào miệng con mèo, and the dogs is lick the cat, there are many dogs go to the house, the dogs is lick the bowl of milk.

The text was submitted to Lextutor https://lextutor.ca/ for analysis. The analysis was for English tokens and types, with Vietnamese words appearing as off-list. However, a careful manual check was necessary as some Vietnamese words are recognized as English words. In this example, con was misrecognized as an English token and the figures needed to be adjusted, leaving in this example 110 English tokens and 37 English types.

3.9 Idea units in students’ stories

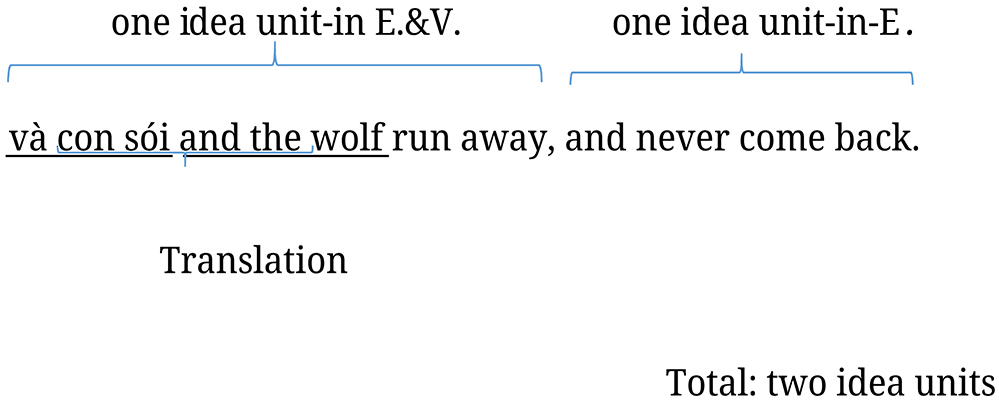

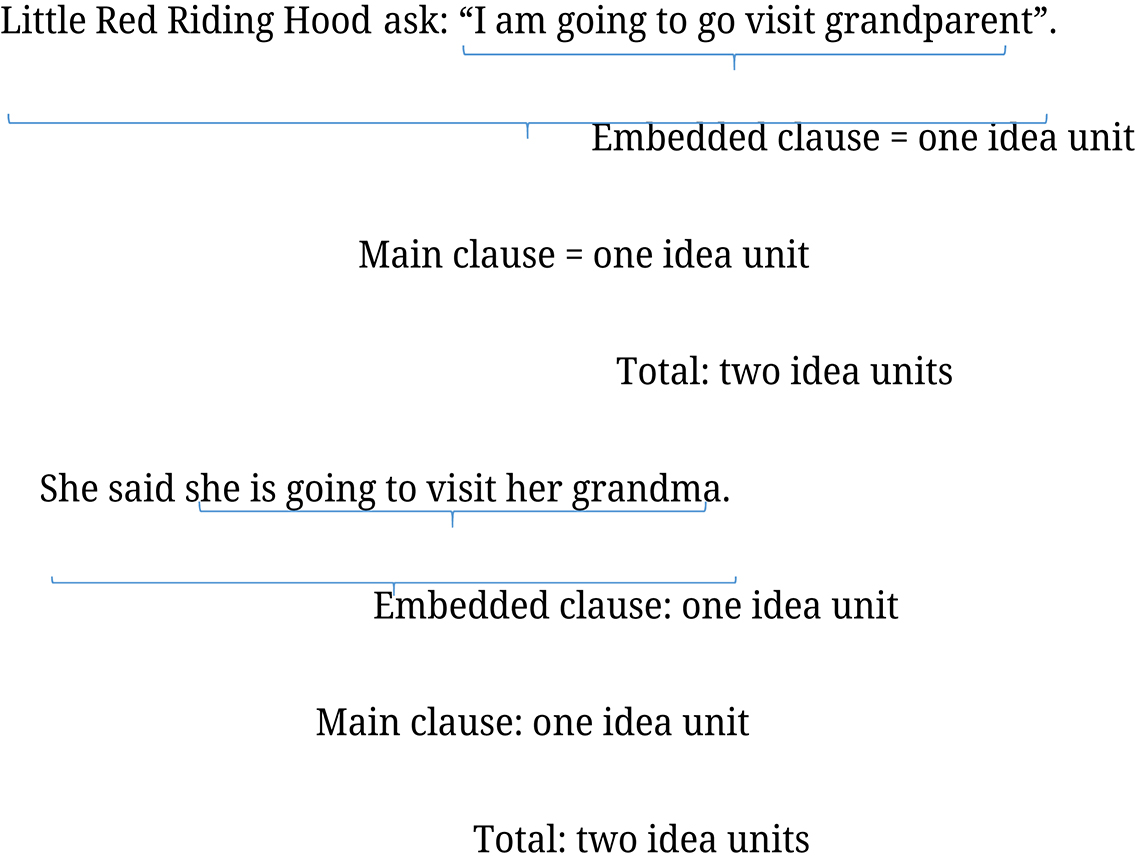

Idea units are the basic elements that are used by speakers to successfully transmit a message. In speaking, they can be identified as spurts of language that are typically separated by a long pause; therefore, pausing is an important factor that serves to identify idea units when transcribing an oral text (Chafe 1985; Gee 2018). An idea unit is associated with a clause and “is spoken with a single coherent intonation contour, ending in what is perceived as a clause-final intonation” (Chafe 1985, p. 106). However, in story retellings, the participating students rarely had clear rising and falling intonation in their English speech as they were affected by the way they spoke their mother tongue and were just English language beginners. Therefore, the keys to identify idea units were brief pauses, and commas were used to show their pauses in the transcriptions; after the retellings were transcribed, clauses were the main tool for counting idea units.

Grammatical mistakes were ignored when counting idea units. For example, a student said: “The dog is lick Tom” instead of saying: “The dog licked Tom”. “The dog is lick Tom” was counted as one idea unit.

There were four types of idea units in the students’ stories.

Idea units in Vietnamese such as “Ngày xửa ngày xưa ở làng kia có một cô bé quàng khăn đỏ” (Once upon a time, in a village lived Little Red Riding Hood).

Idea units in English such as “The wolf walk slowly and slowly”.

Idea units in Vietnamese and English such as “He see one cái bọc is trôi trên water” (He saw a bag floating on the water).

Idea units in Vietnamese with English characters’ names such as “Jerry nấu cháo cho Tom ăn” (Jerry cooked soup for Tom).

Further information about identifying and counting idea units is provided in Appendix C.

3.9.1 Counting idea units

Due to the complication of identifying idea units, they were counted manually with a high degree of caution. The following extract illustrates how idea units were classified and counted. The extract has 12 idea units in English and three idea units in English and Vietnamese. There were no idea units in Vietnamese, and none in Vietnamese with English character names.

| one day in the night Tom and Jerry go out | (one idea unit in English) |

| but he look the car | (one idea unit in English) |

| Jerry is look the car | (one idea unit in English) |

| the car is stop | (one idea unit in English) |

| và một người thanh niên đã lấy và quăng a bag | (one idea unit in English and Vietnamese) |

| the bag is có cái gì nhúc nhích cái gì nhúc nhích | (one idea unit in English and Vietnamese) |

| he open the bag | (one idea unit in English) |

| in the bag is the one dog and some dog is go out and ran away | (three idea units in English) |

| the dog is liếm Jerry | (one idea unit in English and Vietnamese) |

| Jerry is angry and go home | (two idea units in English) |

| but the dog is go with Jerry | (one idea unit in English) |

4 Findings

This study asked whether the storytelling innovation improves primary school students’ oral language production and, if so, to what extent.

4.1 Tokens

Tokens were examined to determine whether the choice of texts affected the students’ language production and whether or not the length of their stories improved.

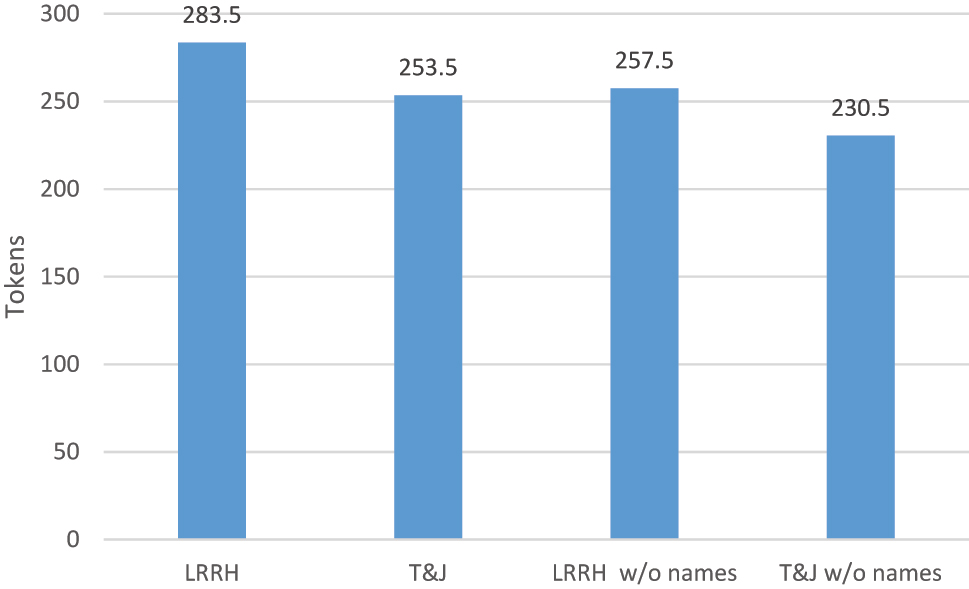

As seen from Figure 1, the median of total tokens in LRRH retellings was higher than T&J retellings. The longer character names of LRRH than in T&J possibly made LRRH longer; however, when character names were removed, the mean of LRRH is still higher than T&J. The median difference between T&J and LRRH with names is about 30 and without names is about 27.

Medians of total tokens in each story.

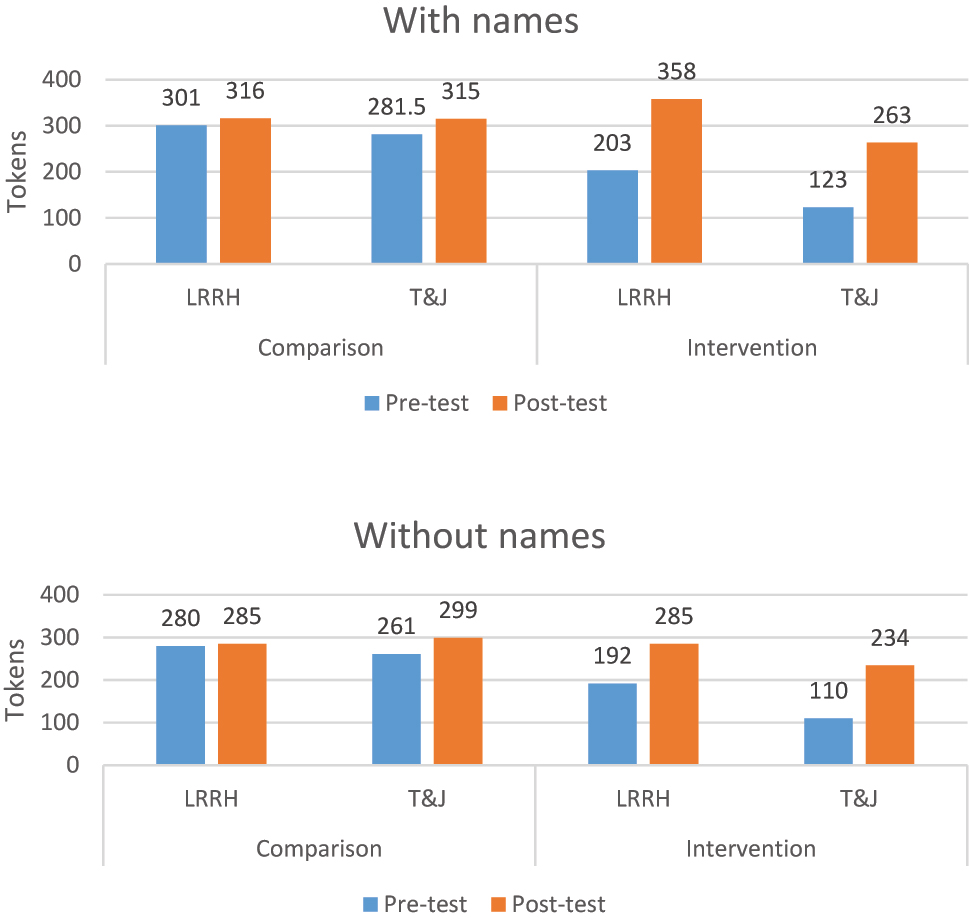

Figure 2 shows that both groups produced longer stories in the post-test than they did in the pre-test in both LRRH and T&J. The comparison group produced longer stories than the intervention group in both pre-and post-test. Both groups produced longer LRRH than T&J stories in both pre- and post-test. When the characters’ names are removed, the medians of stories were a little lower than the medians with names, but the tendencies of language production did not appear to be changed. In sum, the finding from the examination of the central tendencies of total tokens of two stories and of tokens in each story in the pre-test and in the post-test lead to the conclusion that the choice of texts (two different cartoons, one with and one without speaking characters) had little effect on the students’ language production.

Medians of total tokens x story x group.

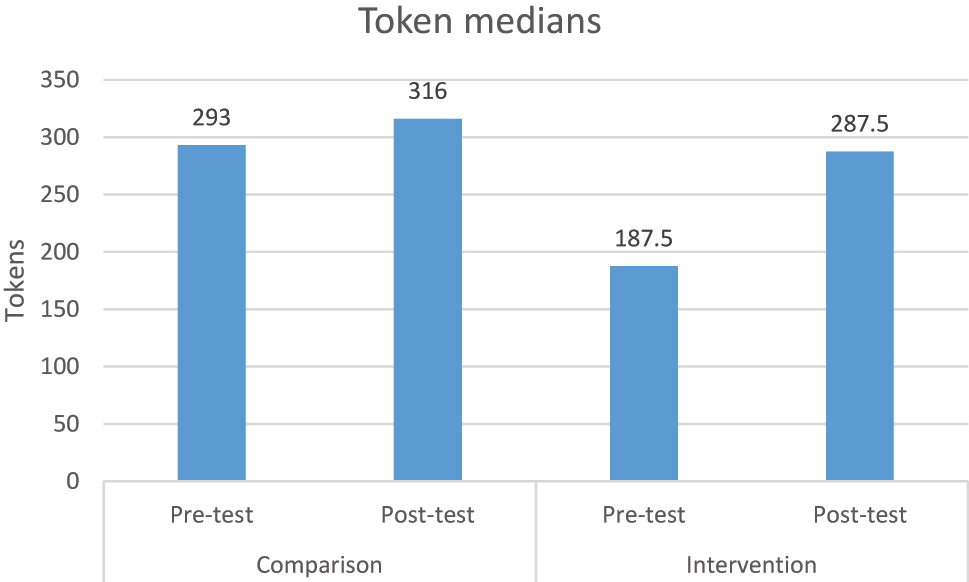

Figure 3 consolidates the findings and reveals that both groups produced more tokens in the post-test than in the pre-test. From the pre-test to post-test, the median scores increased relatively modestly in the comparison group from 293 to 316 but more dramatically, from 187.5 to 287.5, in the intervention group.

Medians of tokens in each story in pre-test and post-test.

The comparison group produced longer stories on both occasions but it is important to recall that up to this point the discussion has included both Vietnamese and English tokens. The following sections will present the analysis of English tokens, types and idea units to examine whether the students improved their oral English production.

4.1.1 English tokens

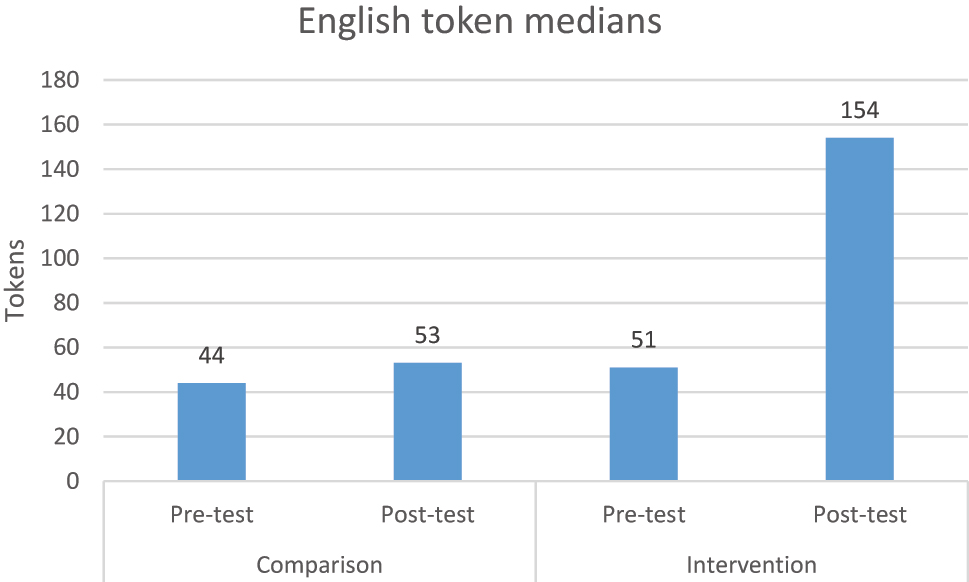

As can be seen in Figure 4, the intervention group produced a few more English tokens than the comparison group in the pre-test. The results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed that the intervention group’s production of English tokens was not statistically significantly higher than the comparison group (Mean Rank = 24.64 for the comparison group and Mean Rank = 30.80 for the intervention group, U = 291, z = 1.420, p = 0.155).

Medians of English tokens.

In Figure 4, we can see that both groups produced more English tokens in the post-test than in the pre-test. From the pre-test to post-test the median scores increased from 44 to 53 in the comparison group and from 51 to 154 in the intervention group.

Unlike the results of token analysis, the Wilcoxon signed rank test for the comparison group indicated that improvement of English tokens was statistically significant in the post-test, T = 229.50, z = 2.272, p = 0.023, with 18 participants ranked as more improved, six participants ranked as negatively improved and one participant ranked as unchanged; this effect can be considered rather ‘large’, r = 0.45. Similarly, the same test for the intervention group indicated that the growth of their English tokens was statistically significant, T = 445.00, z = 4.371, p < 0.000, and the size effect can be considered ‘large’, r = 0.8, 28 participants ranked as more improved and two participants produced less in the post-test. The improvement of the treatment group was much higher than the comparison group as the Mann-Whitney U test indicated that the difference of English tokens between them (Mean Rank = 20.56 for the comparison group and Mean Rank = 34.20 for the intervention group) was statistically significant, U = 189, z = 3.144, p = 0.002, which can be described as a ‘medium’ size effect, r = 0.42.

4.1.2 English types

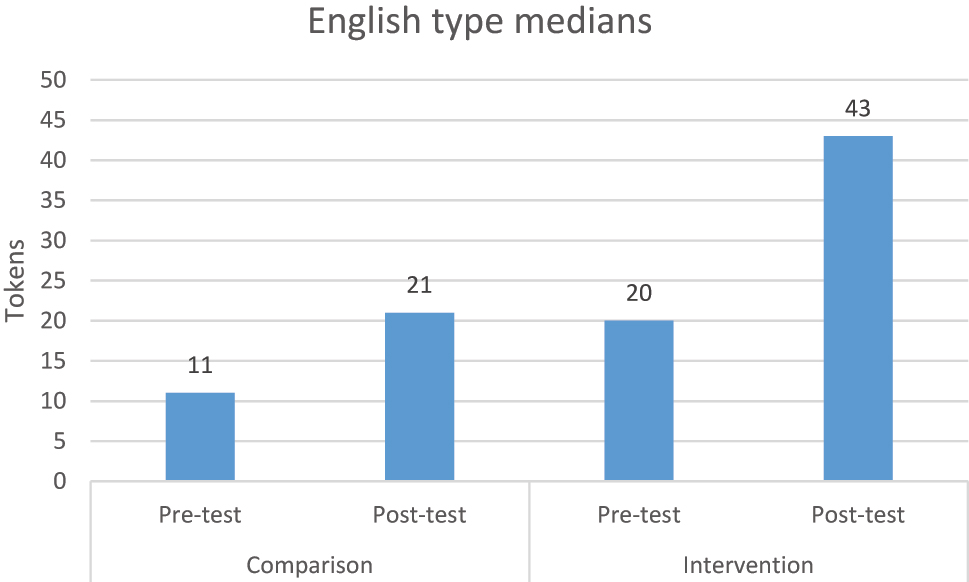

The intervention group produced more English types than the comparison group in the pre-test. The results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed that the intervention group’s production of English tokens was statistically significantly higher than the comparison group (Mean Rank = 23.22 for the comparison group and Mean Rank = 31.98 for the intervention group, U = 255.5, z = 2.021, p = 0.043).

As can be seen from the data in Figure 5, both groups produced more English types in the post-test than in the pre-test. From the pre-test to post-test the median scores increased from 11 to 21 in the comparison group and from 20 to 43 in the intervention group.

Medians of English types.

Similar to the findings of the tests for English tokens, the Wilcoxon signed rank test for the comparison group and the intervention group’s English types indicated that their improvements were both statistically significant. For the comparison group, the results were T = 254, z = 2.977, p = 0.003, with 18 participants again ranked as more improved, six as negatively improved and one as unchanged; this effect can be considered rather ‘large’, r = 0.45. For the intervention group, the results were T = 381, z = 4.054, p < 0.000, with 28 participants again ranked as more improved and two as not; it is considered a ‘large’ effect, r = 0.8. The difference of English types between the comparison group (Mean Rank = 23.18) and the intervention group (Mean Rank = 32.02) was statistically significant as the Mann-Whitney U test computed, U = 254.50, z = 32.039, p = 0.041. This effect can be described as ‘medium’, r = 0.42.

Like the result of the analysis of English tokens, the English types in the intervention group’s retellings were much more than in the comparison group’s as the deviation was significantly different in the post-test. A proper name, no matter how many times it is used, is counted as one type. Therefore, the students’ growth in language use was not strongly affected by naming the characters. Obviously, the number of tokens and types in the students’ stories improved, but how did they use them to create meaningful units in their stories?

4.2 Idea units

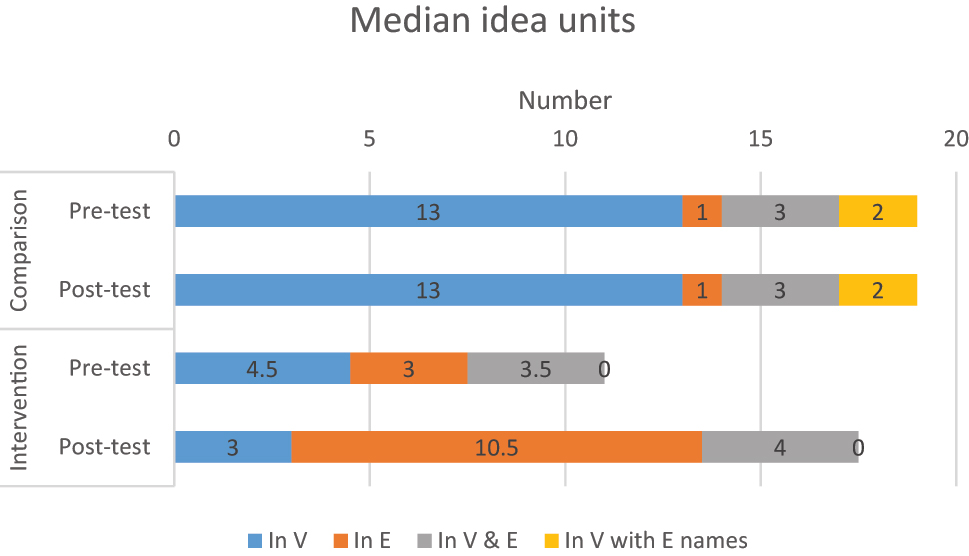

It is apparent in Figure 6 that the comparison group did not increase their idea units in the post-test compared to the pre-test while the intervention group did; specifically, idea units in English increased from 3 to 10.5 and idea units in English and Vietnamese from 3.5 to 4 while idea units in only Vietnamese decreased from 4.5 to 3. Based on these changes, nonparametric tests were run for idea units in English and idea units in English and Vietnamese only.

Medians of idea units.

In the pre-test, the intervention group produced more idea units in English and idea units in English and Vietnamese than the comparison group. The results of the Mann-Whitney U test showed that the differences were statistically significant (for idea units in English: Mean Rank = 24.28 for the comparison group and Mean Rank = 30.10 for the intervention group, U = 2.562, z = 2.021, p = 0.043; for idea units in English and Vietnamese: Mean Rank = 27.64 for the comparison group and Mean Rank = 28.30 for the intervention group, U = 366, z = 0.154, p = 0.877).

In the post-test, the results of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for idea units in English and idea units in English and Vietnamese for both groups were similar. For the comparison group, the improvements of these two kinds of idea units were not statistically significant. The Wilcoxon test results for idea units in English were T = 97, z = 0.974, p = 0.33, with 10 participants ranked as more improved, seven participants ranked as negatively improved and eight participants ranked as unchanged. Those for idea units in English and Vietnamese were T = 116, z = 1.333, p = 0.183, 10 participants ranked as more improved, eight participants ranked as negatively improved and seven participants ranked as unchanged.

Unlike results of the non-parametric t-test for the comparison group, the improvement of the intervention group’s idea units in English and idea units in English and Vietnamese were statistically significant. For idea units-in-English, the Wilcoxon test results were T = 323, z = 3.749, p = 0.000, with 22 participants ranked as more improved, four participants who produced less and four ranked as unchanged in the post-test; the effect can be considered ‘large’, r = 0.68. For idea units in English and Vietnamese, the results were T = 189.50, z = 2.047, p = 0.41, with 16 participants ranked as more improved, six participants who produced less and eight ranked as unchanged in the post-test. The effect can be considered ‘large’, r = 0.68.

Again, Mann-Whitney U tests indicated that the differences of idea units in English and idea units in English and Vietnamese between the comparison group (Mean Rank = 21.30 and 25.98 respectively) and the intervention group (Mean Rank = 33.58 and 29.68 respectively) were statistically significant; (for idea units in English U = 207, z = 2.848, p = 0.004, r = 0.38); for idea units in English and Vietnamese U = 189, z = 3.144, p = 0.002, r = 0.42. The size effects were ‘medium’.

In sum, the major findings show that at the beginning of the study, there was no significant difference in the English-speaking competence in terms of tokens, idea units in English and idea units in English and Vietnamese between the comparison and the intervention groups. At the end of the study, both groups improved their speaking competence, but the changes were quite different. The comparison group improved their oral English production but not as much as the treatment group. The students in the storytelling innovation class improved their oral English communication in dependent variables of English tokens, English types, idea units in English and idea units in English and Vietnamese; and their improvements were statistically significant not only inside each group but also compared to the comparison group (all p < 0.05 in Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and Mann-Whitney U tests).

5 Discussion

This quantitative analysis of the students’ pre- and post-story retellings was conducted to investigate the effect of a storytelling innovation on their oral English language development. These retellings did not require learners to recall and reproduce specific language taught in class, or that was focussed on in the coursebook. Rather, the learners needed to draw on their existing linguistic repertoire, both Vietnamese and English, to retell the story. The English language production of the comparison group and the intervention group both improved when measured by English tokens, English types, idea units in English, and idea units in English and Vietnamese. It is not the case that learners taught traditionally do not learn. However, the degree of their improvement was very different: after the intervention, the English language production of the comparison group slightly increased whereas that of the intervention group nearly doubled in terms of English tokens. In other words, the students in the intervention group created much more English language in their stories than those in the comparison group. In short, the analysis showed that the students in the storytelling innovation improved their English language production in speaking, their improvement was statistically significant and the size effects of the difference were from medium to large, which serves to answer the question as to the effect of the storytelling innovation on primary school students’ oral communicative competence.

This is important for two reasons. First, it shows the importance of applying research-based knowledge about pedagogical effectiveness in the classroom in order to improve language learning outcomes. The innovation was not a new approach in itself, but in this context it qualified as an innovation for being “an idea, practice, or object perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption” (Rogers 2003, p. 12). It responded to understanding of good practice in teaching young learners, such as the need for “rich high-quality language input” (Bland 2015, p. 184), as well as to more general principles, most obviously perhaps that as language is used to convey meaning language teaching should be meaning-focused (as examples, Macalister and Nation 2020, pp. 61–62; Nation 2007) and the recognition of the value of interaction in the classroom. Interaction has been described as “the use of language for communicative purposes, with a primary focus on meaning rather than accuracy” (Philp and Tognini 2009, p. 246), a further reminder that teaching should tend to the meaning-focused. Interaction can also enhance learner engagement, as occurred with this innovation (Le and Macalister forthcoming).

The second reason for the importance of these findings is that this study has also shown how a relatively straightforward, research-informed adaptation of a short existing text in a mandatory textbook can enhance English language teaching for young EFL learners in a context where change can be viewed as difficult to achieve. Further, by adapting material in the required coursebook and providing a set format that could be used repeatedly the storytelling innovation proved to be manageable for the intervention group teacher. She was not being asked to deviate from course content, nor was she being asked to devote extra time and effort to lesson planning. It provides a replicable example of how teachers can address a critical issue, that of optimizing teaching approaches (Rixon 2015, p. 42). This is a global concern. Thus, although this study took place in a particular setting its findings may well be generalizable for it provides an example “of what effective pedagogy for TEYL looks like, revealing local practices that may well have global resonance” (Rich 2014, p. 11).

5.1 Pedagogical considerations

A concern raised by the intervention group teacher, however, was that her students might suffer as a result of the intervention as the storytelling innovation was mainly to improve the students’ speaking while the normal tests focused on the four skills. This is a legitimate concern. Grade 5 students in Vietnam have two end-of-term tests per year. The test scores play a part in determining the students’ primary schooling achievement. One was done at the end of the first term, one week before they started the second term and one was done at the end of the second term. The storytelling intervention was conducted in term two; therefore, the end-of-term-one test was used as a form of pre-test and the end-of-term-two test was used as a form of post-test in this study.

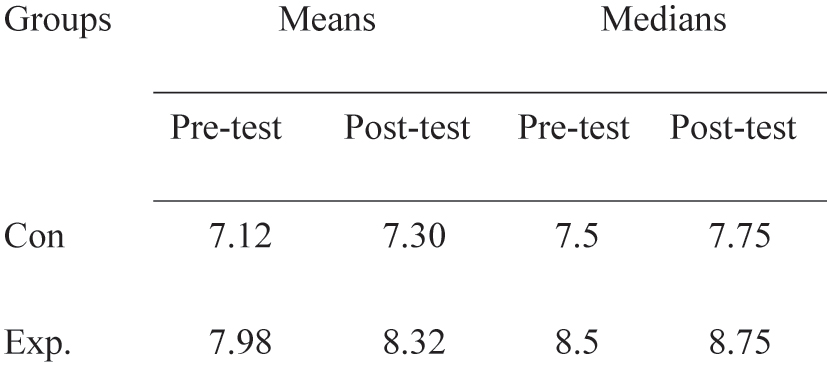

The structure and the content of the tests were designed by the participating schools’ teachers of English on the basis of DOET’s test guides and test matrix. The tests appeared child-friendly with lovely pictures and clear instructions with examples. They were aimed to measure the four language skills with each macro-skill having just 10 questions. In speaking, for example, each student answered 10 questions that were previously learned in the textbook; the focus was on vocabulary and the structures learned in each lesson in the textbook. In the interviews with the participant teachers, they reported that the students wrote the answers to the questions and learned them by heart. This is not the place to raise questions of validity and reliability about the tests. Rather, the nature of the tests reinforces the idea that the comparison group students might be more advantaged because the form of the test matched with the normal learning that focused on language features, whereas the intervention group students might be disadvantaged because the process of their learning, which involved meaning-focused activities like listening to a story, constructing a story and creating a story, were not reflected in normal tests. However, when test scores were analysed, the results showed both classes got higher scores in the post-test than they did in the pre-test. In terms of means scores,[1] the comparison group increased slightly about 0.2 from 7.12 in the pre-test to 7.30 in the post-test. The students in the intervention group improved their test scores a little more than the comparison group, over 0.3 from 7.98 in the pre-test to 8.32 in the post-test. In terms of median, the test scores increased 0.25 for both of the groups. Basically, the intervention had no discernible negative effect, and so allayed teacher concerns (Figure 7).

Means and medians of test scores.

6 Conclusions

In much of the world where English is taught as an additional or foreign language, teachers are faced with challenges such as those found in Vietnam. Classes are large, textbooks are mandated, assessment looms large, and teachers may not feel confident in their own target language proficiency. As a result, teachers often feel reluctant to innovate or adapt materials. This study has shown how a modest change to a text can lead to improved language learning outcomes for young learners in such a situation. The learners who were taught using the storytelling innovation made significant gains in their speaking performance as measured by quantity and range of English vocabulary used in a retelling task, and by idea units expressed in English. While the time on task for the two classes was similar, with the difference being the pedagogical approach employed, conceivable limitations on the results are that learners in the intervention class were exposed to richer language input than those in the comparison class and they had greater exposure to and practice in producing narratives. Nevertheless, using available local assessment data, their improved speaking performance did not appear to come at the expense of other skills or sub-skills. The study has, therefore, demonstrated what it is possible to achieve within the constraints that exist in an EFL classroom setting. Future research could extend these results by investigating the exact nature of the linguistic development, such as the use of formulaic language, and any relationship between improved speaking performance and the production of short, written narrative texts.

Funding source: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington

Funding source: Government of Vietnam PhD scholarship

Award Identifier / Grant number: 216080

Appendix A: A textbook lesson

What’s the matter with you?

Appendix B: Counting tokens

To ensure consistency in counting tokens, the following decisions were taken.

Students’ introductions and farewells were removed; for example, “My name _____” or “I am ___” or plain “Goodbye” were erased.

Talking about their class and school were removed; for example, “I am a student of class____. I’ m studying at ___(name) primary school” were excluded.

Grammatical mistakes like “walk” in “The wolf walk slowly” were ignored; “walk” was counted as one token.

Self-correction was included in token counting, as self-correction is part of speaking. For example, “It they” in “It they are five dog” was counted as two tokens.

Contractions were transferred into full words. For example, “He’s … ” was transferred as “he is … ”

Repetition is part of our fluency. There were three kinds of repetitions in the students’ story retellings:

repetition showing that the speaker was thinking as in “a a a … bag … ”; the three “a” words were counted as one token; two a were removed.

repetition showing that the speaker wanted to make clear what he or she wanted to say as “bowl” in “The dog running đến chỗ (to) bowl milk bowl”. In this example, “bowl” was counted as two tokens.

repetition emphasizing meaning as in “The wolf walk slowly and slowly” where “slowly” words were counted as two tokens.

Proper names of title characters were counted as tokens. For example, “Little Red Riding Hood” was counted as four tokens, “Little Red” as two tokens, “Tom” as one token.

Appendix C: Counting idea units

To be consistent in counting idea units, the following inclusions and exclusions were taken into consideration. Some examples will be diagrammatically presented to make clear the explanations of what are or are not taken in idea units.

Any clauses with words in both languages were counted as idea units in English and Vietnamese. For example, in “Và and then the Riding Hood is and her grandma was happy”, this clause was counted as one idea unit in Vietnamese and English.

In a compound sentence, the first clause that had bilingual words was counted as an idea unit in Vietnamese and English and the second clause was an idea unit in only English as displayed in the example:

In direct speech, the embedded clause was counted as one idea unit and the main clause was counted as one idea unit. Their examples were diagrammatically presented as follows:

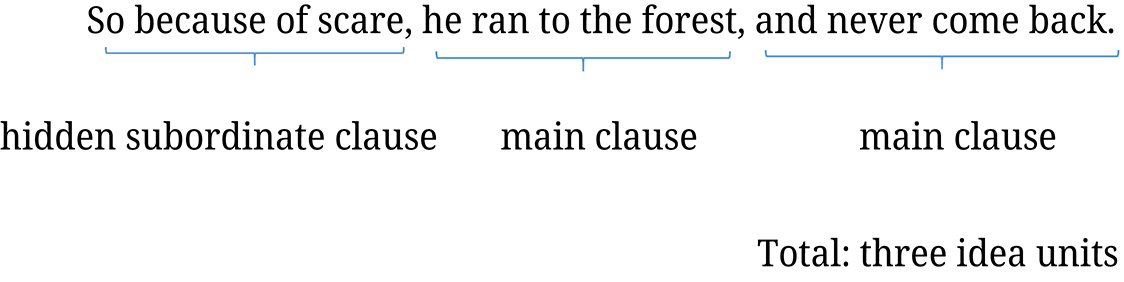

Similarly, in a complex sentence, its subordinate clause or its hidden subordinate clause was counted as one idea unit and its main clause was counted as one idea unit. For example:

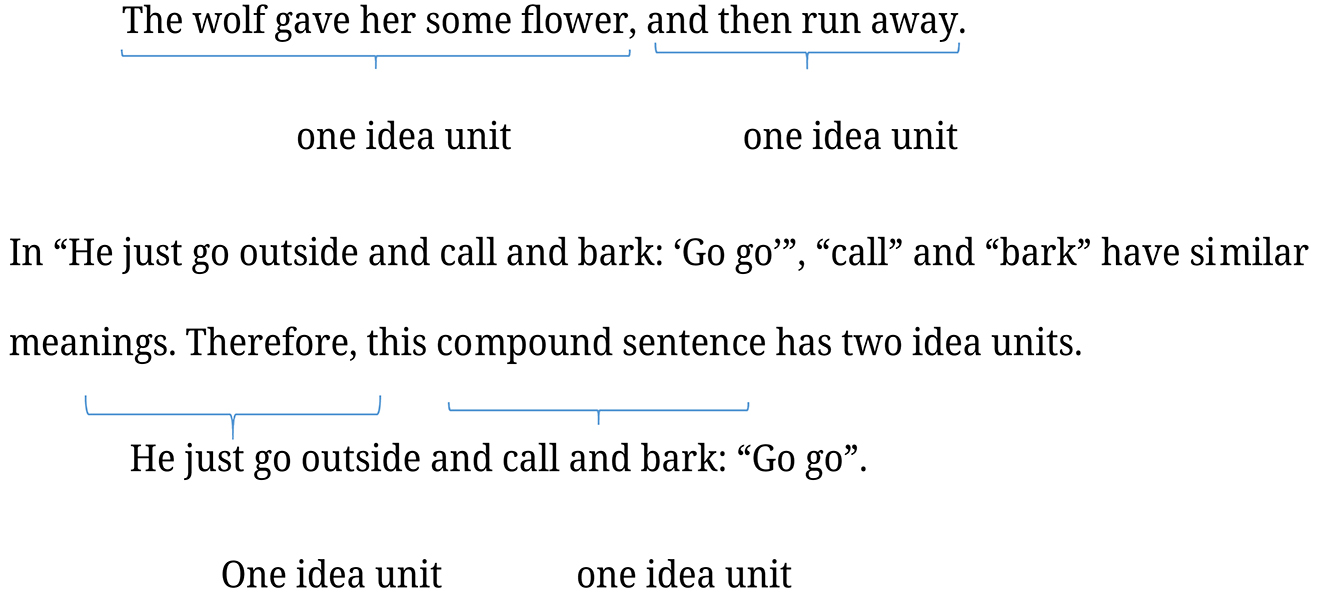

The numbers of idea units in a compound sentence depended on the number of main verbs. For example, in “The wolf gave her some flower, and then run away”, two idea units were counted.

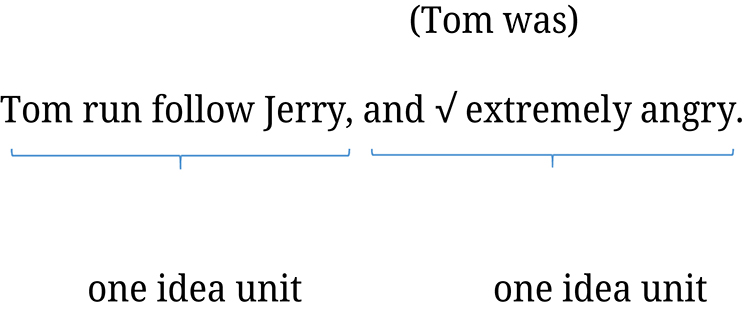

In speaking, the subject and the main verb were sometimes absent but listeners could understand the missing information as they listened to the story from the beginning. For example, in “Tom run follow Jerry, and extremely angry”, “Tom was” was missing but the sentence was understandable. Therefore, the example sentence was counted as having two idea units.

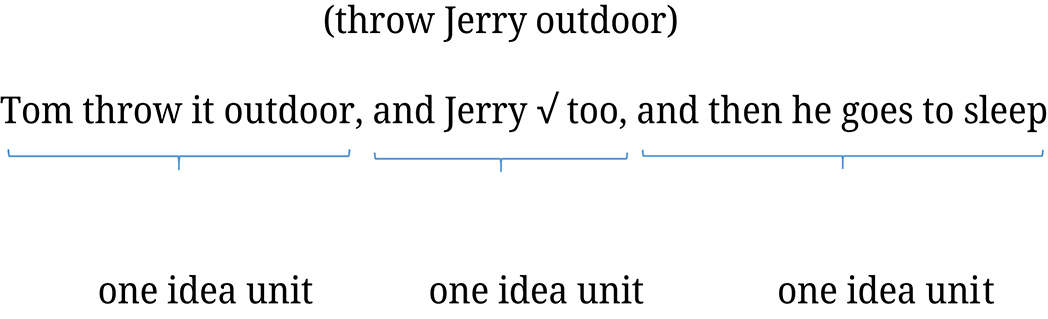

Likewise, as in “Tom throw it outdoor, and Jerry too, and then he goes to sleep”, the speaker meant “Tom throw Jerry outdoor too.” “Jerry too” was counted as an idea unit.

Children sometimes used wrong names in telling a story, but the listeners still understood what the speaker meant because they were in the story context. For example, in “Tom think Tom think him a bad guy because he throw Tom and the dog outside”, the second “Tom” and the third “Tom” meant “Jerry”. The example sentence was counted as having two idea units.

Repeated clauses were counted as one idea unit. For example, in “The girl is funny. The grandparent is funny, and the girl is funny.” The two instances of “The girl is funny” were counted as one idea unit. A repeated clause to make the meaning of the previous clause clear was counted as one idea unit, as in “because it’s a bowl it’s a Tom bowl” (Tom’s bowl), in which two idea units was counted.

Meaningless sentences and phrases were not counted, as in “He get the dog a bowl of milk, but Tom doesn’t want to drink of the dog, so he throw the dog to the window”, “but Tom doesn’t want to drink of the dog” was not counted, and in “He dream dream he take Jerry and the dog, he dream he doesn’t love Jerry and the dog”, “He dream dream he take Jerry and the dog” was excluded.

Introductions and closures were excluded in counting idea units.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington (216080) and Government of Vietnam PhD scholarship.

References

Alkaaf, Fatma & Ali Al-Bulushi. 2017. Tell and write, the effect of storytelling strategy for developing story writing skills among grade seven learners. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 7(2). 119. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2017.72010.Search in Google Scholar

Allen, Peter, Kellie Bennett & Brody Heritage. 2014. SPSS statistics version 22: A practical guide, 3rd edn. South Melbourne: Cengage Learning. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/vuw/detail.action?docID=4635118.Search in Google Scholar

Belet, S. Dilek & Sibel Dala. 2010. The use of storytelling to develop the primary school students’ critical reading skill: The primary education pre-service teachers’ opinions. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 9. 1830–1834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.409.Search in Google Scholar

Bland, Janice. 2015. Oral storytelling in the primary English classroom. In Janice Bland (ed.), Teaching English to young learners: Critical issues in language teaching with 3–12 year olds, 183–198. London: Bloomsbury Academic.Search in Google Scholar

Brenes, Brenes, César Alberto Navas. 2005. Analyzing an oral narrative using discourse analysis tools: Observing how spoken language works. Actualidades Investigativas en Educación 5(1). 1–19.10.15517/aie.v5i1.9119Search in Google Scholar

Bui, Trang Le Diem & Jonathon Newton. 2021. PPP in action: Insights from primary EFL lessons in Vietnam. Language Teaching for Young Learners 3(1). 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.19015.bui.Search in Google Scholar

Cameron, Lynne. 2001. Teaching languages to young learners. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511733109Search in Google Scholar

Chafe, Wallace L. 1985. Linguistic differences produced by differences between speaking and writing. In David R. Olson, Nancy Torrance & Angela Hildyard (eds.), Literacy, language, and learning: The nature and consequences of reading and writing, 105–123. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Chwo, Gloria Shu-Mei & Bih-Hua Chen. 2015. Storytelling to young EIL learners in Taiwan: A cautionary tale. 弘光學報 76. 75–94.Search in Google Scholar

Cremin, Teresa, Rosie Flewitt, Ben Mardell & Joan Swann (eds.). 2017. Storytelling in early childhood: Enriching language, literacy and classroom culture. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9781315679426Search in Google Scholar

Elley, Warwick B. & Francis Mangubhai. 1983. The impact of reading on second language learning. Reading Research Quarterly 19(1). 53–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/747337.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Gail. 1995. Storytelling and storybooks: A broader version of the communicative approach. The Journal of TESOL France-British Council 2(1). 89–100.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Gail & Jean Brewster. 2014. Tell it again! The storytelling handbook for primary English language teachers. London: British Council.Search in Google Scholar

Enever, Janet. 2020. Global language policies: Moving English up the educational escalator. Language Teaching for Young Learners 2(2). 162–191. https://doi.org/10.1075/ltyl.19021.ene.Search in Google Scholar

Fikriah. 2016. Using the storytelling technique to improve English speaking skills of primary school students. English Education Journal 7(1). 87–101.Search in Google Scholar

Garcia, Fabián Vergel. 2017. Storytelling and grammar learning: A study among young - elementary EFL learners in Colombia. International Journal of English and Education 6(2). 63–81.Search in Google Scholar

Gee, James Paul. 1991. A linguistic approach to narrative. Journal of Narrative and Life History 1(1). 15–39.10.1075/jnlh.1.1.03aliSearch in Google Scholar

Gee, James Paul. 2018. Introducing discourse analysis: From grammar to society. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.10.4324/9781315098692Search in Google Scholar

Gomez, Asuncion Barreras. 2010. How to use tales for the teaching of vocabulary and grammar in a primary education English class. Revista Espanola de Linguistica Aplicada 23. 31–52.Search in Google Scholar

Gupta, Amita. 2009. Vygotskian perspectives on using dramatic play to enhance children’s development and balance creativity with structure in the early childhood classroom. Early Child Development and Care 179(8). 1041–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430701731654.Search in Google Scholar

Kalantari, Farzaneh & Mahmood Hashemian. 2016. A storytelling approach to teaching English to young EFL Iranian learners. English Language Teaching 9(1). 221–234. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v9n1p221.Search in Google Scholar

Kersten, Saskia. 2015. Language development in young learners: The role of formulaic language. In Janice Bland (ed.), Teaching English to young learners. Critical issues in language teaching with 3–12 year olds, 129–145. London: Bloomsbury Academic.Search in Google Scholar

Kiernan, Patrick. 2005. Storytelling with low-level learners: Developing narrative tasks. In Corony Edwards & Jane Willis (eds.), Teachers exploring tasks in English language teaching, 58–68. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230522961_6Search in Google Scholar

Kim, S. 2013. Comparison of task-based and storytelling-based English classroom interaction in Korean elementary schools. English teaching 68(3). 51–83. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.68.3.201309.51.Search in Google Scholar

Kirsch, Claudine. 2016. Using storytelling to teach vocabulary in language lessons: Does it work? The Language Learning Journal 44(1). 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2012.733404.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen D. 1985. The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Krashen, Stephen D. & Tracy D. Terrell. 1995. The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. Padstow, UK: Prentice Hall Europe.Search in Google Scholar

Laufer, Batia & Paul Nation. 1995. Vocabulary size and use: Lexical richness in L2 written production. Applied Linguistics 16(3). 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/16.3.307.Search in Google Scholar

Le, Hong Phuong Thao. 2020. Storytelling and teaching English to young learners: A Vietnamese case study. Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Le, Hong Phuong Thao & John Macalister. forthcoming. Engagement in oral production: The impact of a coursebook innovation. Language Teaching for Young Learners.Search in Google Scholar

Le, Van Canh & Roger Barnard. 2009. Curricular innovation behind closed classroom doors: A Vietnamese case study. Prospect 24(2). 20–33.Search in Google Scholar

Le, Van Canh & Thi Mai Chi Do. 2012. Teacher preparation for primary school English education: A case of Vietnam. In Bernard Spolsky & Young-in Moon (eds.), Primary school English language education in Asia: From policy to practice, 106–128. New York & London: Taylor & Francis.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Chen Ying & Paul Seedhouse. 2010. Classroom interaction in story-based lessons with young learners. The Asian EFL Journal Quarterly 12(2). 288–315.Search in Google Scholar

Linse, Caroline. 2007. Predictable books in the children’s EFL classroom. ELT Journal 61(1). 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl044.Search in Google Scholar

Lucarevschi, Claudio R. 2018. The role of storytelling in the development of pronunciation of Brazilian learners of English as a foreign language. Victoria, Canada: University of Victoria PhD thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Macalister, John. 2016. Adapting and adopting materials. In Maryam Azarnoosh, Mitra Zeraatpishe, Akram Faravani & Hamid Reza Kargozari (eds.), Issues in materials development, 57–64. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.Search in Google Scholar

Macalister, John & I. S. P. Nation. 2020. Language curriculum design, 2nd edn. New York & London: Routledge.10.4324/9780429203763Search in Google Scholar

McGee, Lea M. & Judith A. Schickedanz. 2007. Repeated interactive read‐alouds in preschool and kindergarten. The Reading Teacher 60(8). 742–751. https://doi.org/10.1598/rt.60.8.4.Search in Google Scholar

Mourão, Sandie. 2015. The potential of picturebooks with young learners. In Janice Bland (ed.), Teaching English to young learners: Critical issues in language teaching with 3–12 year olds, 199–217. London: Bloomsbury Academic.Search in Google Scholar

Nation, Paul. 2007. The four strands. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 1(1). 2–13. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt039.0.Search in Google Scholar

Nation, Paul. 2018. Keeping it practical and keeping it simple. Language Teaching 51(1). 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444817000349.Search in Google Scholar

Nguyen, Bao Trang Thi, David Crabbe & Jonathon Newton. 2018. Teacher transformation of oral textbook tasks in Vietnamese EFL high school classrooms. In Virginia Samuda, Kris Van Den Branden & Martin Bygate (eds.), TBLT as a researched pedagogy, 52–70. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

Oduolowu, Esther & Akintemi E. Oluwakemi. 2014. Effect of storytelling on listening skills of primary one pupil in Ibadan north local government area of Oyo State, Nigeria. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 4(9). 100–107.Search in Google Scholar

Park, Barbara. 1982. The big book trend: A discussion with Don Holdaway. Language Arts 59(8). 15–821.10.58680/la198226487Search in Google Scholar

Peck, Sabrina. 2001. Developing children’s listening and speaking in ESL. In Marianne Celce-Murcia (ed.), Teaching English as a foreign language, 3rd edn., 139–149. Boston: Cengage Learning.Search in Google Scholar

Philp, Jenefer & Rita Tognini. 2009. Language acquisition in foreign language contexts and the differential benefits of interaction. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 47(3–4). 245–266. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2009.011.Search in Google Scholar

Read, John. 2000. Assessing vocabulary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511732942Search in Google Scholar

Rich, Sarah. 2014. Taking stock: Where are we now with TEYL? In Sarah Rich (ed.), International perspectives on teaching English to young learners, 1–19. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137023230_1Search in Google Scholar

Rixon, Shelagh. 2015. Primary English and critical issues: A worldwide perspective. In Janice Bland (ed.), Teaching English to young learners: Critical issues in language teaching with 3–12 year olds, 31–50. London: Bloomsbury Academic.Search in Google Scholar

Rogers, Everett M. 2003. Diffusion of innovations, 5th edn. New York: Free Press.Search in Google Scholar

Samuda, Virginia & Martin Bygate. 2008. Tasks in second language learning. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230596429Search in Google Scholar

Soe, Marlar Lwin. 2016. It’s story time!: Exploring the potential of multimodality in oral storytelling to support children’s vocabulary learning. Literacy 50(2). 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12075.Search in Google Scholar

Van Hout, Roeland & Anne Vermeer. 2007. Comparing measures of lexical richness. In Daller, Helmut, James Milton & Jeanine Treffers-Daller (eds.), Modelling and assessing vocabulary knowledge, 221–238. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1017/CBO9780511667268.008Search in Google Scholar

Wright, Andrew. 1995. Storytelling with children. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Unpacking the positioning of being “disengaged” and “disrespectful” in class through nexus analysis: an international student’s navigation of institutional and interactional university norms

- Assessing English language learners’ collocation knowledge: a systematic review of receptive and productive measurements

- The role of awareness in implicit and explicit knowledge

- Intensity of CLIL exposure and L2 motivation in primary school: evidence from Spanish EFL learners in non-CLIL, low-CLIL and high-CLIL programmes

- Promoting young EFL learners’ oral production through storytelling: coursebook adaptation in the Vietnamese classroom

- Applying embodied meaning of spatial prepositions and the Principled Polysemy model to teaching English as a second language: the case of to and on

- The impact of guessing and retrieval strategies for learning phrasal verbs

- Unraveling the differential effects of task rehearsal and task repetition on L2 task performance: the mediating role of task modality

- Examining L2 studentsʼ development of global cohesion and its relationship with their argumentative essay quality

- The construct of integrated group discussion (IGD) among undergraduate students: to what extent does group discussion performance reflect performance on IGD tasks?

- Discipline-specific attitudinal differences of EMI students towards translanguaging

- Relationship between second language vocabulary knowledge and vocabulary learning strategy use: a meta-analysis of correlational studies

- Evaluative language in undergraduate academic writing: expressions of attitude as sources of text effectiveness in English as a Foreign Language

- Investigating optimal spacing schedules for incidental acquisition of L2 collocations

- The association between socioeconomic status and Chinese secondary students’ English achievement: mediation of self-efficacy and moderation of gender

- Integrated instruction of Appraisal Theory and rhetorical moves in literature reviews: an exploratory study

- Scaffolding in genre-based L2 writing classes: Vietnamese EFL teachers’ beliefs and practices

- Exploring the professional role identities of English for academic purposes practitioners: a qualitative study

- The combined effects of task repetition and post-task teacher-corrected transcribing on complexity, accuracy and fluency of L2 oral performance

- Teacher behaviour and student engagement with L2 writing feedback: a case study

- The effect of an intervention focused on academic language on CAF measures in the multilingual writing of secondary students

- Which approach best promoted low-proficiency learners’ listening performance: metacognitive, bottom-up or a combination of both?

- Enhancing young EFL learners’ written skills: the role of repeated pre-task planning

- The mediating roles of resilience and motivation in the relationship between students’ English learning burnout and engagement: a conservation-of-resources perspective

- Student and teacher beliefs about oral corrective feedback in junior secondary English classrooms

- The effects of context, story-type, and language proficiency on EFL word learning and retention from reading

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Unpacking the positioning of being “disengaged” and “disrespectful” in class through nexus analysis: an international student’s navigation of institutional and interactional university norms

- Assessing English language learners’ collocation knowledge: a systematic review of receptive and productive measurements

- The role of awareness in implicit and explicit knowledge

- Intensity of CLIL exposure and L2 motivation in primary school: evidence from Spanish EFL learners in non-CLIL, low-CLIL and high-CLIL programmes

- Promoting young EFL learners’ oral production through storytelling: coursebook adaptation in the Vietnamese classroom

- Applying embodied meaning of spatial prepositions and the Principled Polysemy model to teaching English as a second language: the case of to and on

- The impact of guessing and retrieval strategies for learning phrasal verbs

- Unraveling the differential effects of task rehearsal and task repetition on L2 task performance: the mediating role of task modality

- Examining L2 studentsʼ development of global cohesion and its relationship with their argumentative essay quality

- The construct of integrated group discussion (IGD) among undergraduate students: to what extent does group discussion performance reflect performance on IGD tasks?

- Discipline-specific attitudinal differences of EMI students towards translanguaging

- Relationship between second language vocabulary knowledge and vocabulary learning strategy use: a meta-analysis of correlational studies

- Evaluative language in undergraduate academic writing: expressions of attitude as sources of text effectiveness in English as a Foreign Language

- Investigating optimal spacing schedules for incidental acquisition of L2 collocations

- The association between socioeconomic status and Chinese secondary students’ English achievement: mediation of self-efficacy and moderation of gender

- Integrated instruction of Appraisal Theory and rhetorical moves in literature reviews: an exploratory study

- Scaffolding in genre-based L2 writing classes: Vietnamese EFL teachers’ beliefs and practices

- Exploring the professional role identities of English for academic purposes practitioners: a qualitative study

- The combined effects of task repetition and post-task teacher-corrected transcribing on complexity, accuracy and fluency of L2 oral performance

- Teacher behaviour and student engagement with L2 writing feedback: a case study

- The effect of an intervention focused on academic language on CAF measures in the multilingual writing of secondary students

- Which approach best promoted low-proficiency learners’ listening performance: metacognitive, bottom-up or a combination of both?

- Enhancing young EFL learners’ written skills: the role of repeated pre-task planning

- The mediating roles of resilience and motivation in the relationship between students’ English learning burnout and engagement: a conservation-of-resources perspective

- Student and teacher beliefs about oral corrective feedback in junior secondary English classrooms

- The effects of context, story-type, and language proficiency on EFL word learning and retention from reading