Abstract

Pseudo-copulative change-of-state (PCOS) verbs are predicates that involve a change in the composition of an entity undergoing a particular event. Due to their complex linguistic nature, these verbs are not easy to be accounted for and consequently, they represent a real challenge to language teachers and learners. First, this paper critically examines the specialized L1 and L2 literature on PCOS verbs in Spanish. Then, it is shown that previous studies are unable to provide a unanimous theory, but rather offer heterogeneous explanations that are full of exceptions and overlook semantic nuances. The second part of this work presents a corpus-based constructional study of the PCOS verbal structure [Vcl+NP] in two PCOS verbs, hacerse ‘make.cl’ and volverse ‘turn.cl’. It is argued that a multi-level family of PCOS constructions captures both the specificity of fully-saturated constructions (María se hizo mujer ‘María became a woman’), as well as the more general abstract patterns ([Subject PCOS-verb Object]). This constructional approach offers a unified and motivated explanation for these PCOS verbs that can be very useful for Spanish as a Foreign Language (SFL).

1 The elusive nature of change-of-state verbs

Change-of-state verbs (henceforth, COS) are predicates that involve a change in the composition of an entity undergoing a particular event. The characteristics of the change are taken from the semantic information provided by the event itself. Due to their complex and heterogeneous linguistic nature, COS verbs are not easy to either categorize or describe as a group. Two of the major challenges that the researcher has to face when working with these verbs are: (i) to decide which particular verbs can actually be classified as COS verbs; (ii) to find a converging linguistic description that accounts for their diverse morphosyntactic and semantic characteristics.

These questions have attracted the attention of researchers working from diverse theoretical frameworks and in different languages. One way to tackle these challenges has been to take a semantic perspective in order to explain and predict grammatical behavior. This is the path taken in Fillmore’s (1970) seminal paper on hitting and breaking verbs, later expanded on by Levin and collaborators (Levin 1993; Levin and Rappaport Hovav 1995; Rappaport Hovav and Levin 2005, among others). The main idea underlying these studies is that the meaning encoded in a verb largely determines its morphosyntactic and interpretive properties. Levin’s (1993) now classic English verb classification, for example, distinguishes six verbal COS subclasses—breaking verbs (break, crack, crush), bending verbs (bend, crease, fold), cooking verbs (bake, barbecue, boil), other alternating verbs of COS (advance, grow, melt), verbs of entity-specific COS (blister, erode, ferment), and verbs of calibratable COS (climb, decline, rise)— that are subdivided into two different groups: externally-caused COS verbs and internally-caused COS verbs. These groups take different arguments on the basis of three main characteristics: controllability (the degree to which an event can be externally manipulated), causer type (whether the event is human-driven or nonhuman-driven), and subject-modification (whether the causer is in a modified or unmodified form) (Wright 2002).

This procedure has been expanded and applied to account for COS verbs in other languages such as French (Dubois and Dubois-Charlier 1997; Saint-Dizier 1999), or Spanish (Demonte 1994; Vázquez et al. 2000), as well as in contrastive analyses (Rodríguez Arrizabalaga 2001; Bordignon 2003; Duée and Lauwers 2010; Lauwers and Duée 2010, Lauwers and Duée 2011). In general, these studies focus on issues such as the role of the Aktionsart in the event structure (Demonte 1994; Vázquez et al. 2000) or the types of syntactic alternations that these COS verbs occur in. For example, externally-caused COS verbs such as break are said to participate in the causative/inchoative alternation where the verb is used both intransitively (The vase broke) and transitively (Michael broke the vase), whereas internally-caused COS verbs prefer the intransitive variant (The milk fermented, *Michael fermented the milk) (see Rappaport Hovav and Levin 2005). Another variant is the middle alternation. This occurs in cases where the subject is diffused and its function is taken over by the direct object argument as illustrated in Bordignon’s (2003: 45) examples for English, French, and Spanish, respectively, in (1).

John cuts the tart → The tart cuts easily

Colin coupe le gâteau → Le gâteau se coupe facilement

Pedro corta el pastel → El pastel se corta con facilidad

Despite their efforts, these proposals face shortcomings when they have to provide a unified account for COS verbs to capture their general semantic and grammatical features, as well as their underlying unique and individual semantic character. Unfortunately, these accounts are full of exceptions to general explanations, while also neglecting subtle differences in meaning. For instance, although internally-caused COS verbs are often used intransitively, sometimes they can also happen in transitive variants (Wright 2002). Furthermore, although alternations like those in (1) are found across different languages, the distribution of verbs that happen in these alternations, their combinations with other elements (such as adjectives or nouns), and their usage (e. g. register) are not always the same. For example, pseudo-copulative COS verbs in Spanish include verbs [1] such as hacer(se) ‘to make(cl)’, volver(se) ‘to turn(cl)’, poner(se) ‘to put(cl)’, and quedar(se) ‘to remain(cl)’, whereas in English, the list includes similar verbs, such as become, get, and turn but also go, fall, and come (see Fente 1970; Rodríguez Arrizabalaga 2001; Huddleston and Pullum 2002; Culicover and Dellert 2008).

Similarly, even if there were no formal exceptions, the choice of individual COS verbs within the same class is not trivial. Alternative examples are provided in (2).

| María | se | ha | vuelto | roja |

| mary | cl | has | turned | red |

| María | se | ha | hecho | roja |

| mary | cl | has | made | red |

| María | se | ha | puesto | roja |

| mary | cl | has | put | red |

| María | se | ha | quedado | roja |

| mary | cl | has | remained | red |

All examples in (2) have the same type of grammatical structure and properties. They are pseudo-copulative COS verbs (with the verb plus the clitic se) with a complement. They all express a general meaning, which is a change in the nature of the entity. María, before undergoing that change, was not roja ‘red’. However, each of these pseudo-copulative COS verbs adds a specific semantic interpretation: the speaker’s own view of how the change occurs. Examples (2.a) and (2.b) convey the figurative meaning of roja ‘red’ as a communist. In (2.a), the verb volverse ‘turn.cl’ adds the idea that the change is radical, that is, totally opposed to what María was before. In (2.b), the verb hacerse ‘make.cl’ indicates just the adoption of a new socioeconomic dogma, regardless of what María was before. In (2.c), the verb ponerse ‘put.cl’ means that María blushes at that moment, but it does not necessarily mean that the change occurs at a more permanent level. Finally, in (2.d), the verb quedarse ‘remain.cl’ expresses the final state after the changing process comes to an end. Something happened and as a consequence María went red as a beet.

These issues (lack of unified accounts, exceptions to general rules, semantic nuances overlooked) are important for a theoretical account of COS verbs, but they become paramount when it comes to teaching and learning a second language. The elusive nature of these verbs, both semantic and grammatical, is a real challenge for teachers and learners alike.

This paper takes up this challenge and aims at shedding further light on how to account for a more unified teaching and learning approach to COS verbs. In order to accomplish this, we direct our attention to a formal verb subclass: pseudo-copulative change-of-state (PCOS) verbs in Spanish. The first part of this paper offers a critical overview of the specialized literature on these verbs in L1 and L2 Spanish. The second part provides a corpus-based constructional analysis (Goldberg 1995, Goldberg 2006) of the verbal structure [Vcl+NP] in hacerse ‘make.cl’+NP and volverse ‘turn.cl’+NP. The final section draws some conclusions on the basis of these results and establishes future lines of research in SFL to improve the teaching of these verbs.

2 Pseudo-copulative change-of-state verbsin Spanish: A critical overview

2.1 The study of PCOS verbs in Spanish L1

Although the study of PCOS verbs has attracted the attention of many researchers with different theoretical perspectives and research agendas, most of this work revolves around three main problematic areas: the categorization of PCOS verbs, the internal classification of PCOS verbs, and the explanation of PCOS verb-construction alternations.

With respect to the first area, the categorization of PCOS verbs has been the focus of attention in descriptive analyses, grammar books, and phraseological studies. Unfortunately, these studies do not agree on basic issues such as the name for this category or the number and type of its members. For instance, they are known as intransitive reflexive verbs (Crespo 1949), attributive reflexive verbs (Navas Ruiz 1963), auxiliaries and functional verbs (Alba de Diego and Lunell 1988), se constructions (Fernández Leborans 1999) or canonical change constructions (Rodríguez Arrizabalaga 2001) in descriptive studies. However, they are considered idiomatic expressions, pluriverbal lexical units, formulaic or prefabricated sequences or lexical chunks in phraseological studies (Casares 1969 [1950]; Firth 1957; Corpas Pastor 1996; Koike 2001). A look at grammars of Spanish does not offer a different picture. Works such as the Nueva gramática de la lengua española (RAE/ASALE 2009) consider these verbs as a category of their own. The Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española (Fernández Leborans 1999) does not treat PCOS separately, but rather as part of a wider phenomenon: the se constructions. This disparity is also reflected in grammar textbooks. Nilsson et al.’s (2014) article, for example, includes PCOS in the group of intransitive change-of-state verbs, whereas Matte Bon’s (1992) communicative grammar groups them together with other verb types that have an effect on the characteristics of the subject (what this author calls “subject transformations”). As far as category members are concerned, the same variation is found. The list of members and structures provided in Crespo (1949) and Coste and Redondo (1965) has served as the starting point for many subsequent studies. These have reduced the number of members but, once again, in different ways (cf. Navas Ruiz 1963; Fente 1970; Lorenzo 1970; Pountain 1984; Eberenz 1985; Porroche Ballesteros 1988; Eddington 1999; Bybee and Eddington 2006; Morimoto and Pavón Lucero 2007; Conde Noguerol 2013; Van Gorp 2017).

In relation to the second area, the internal classification of PCOS verbs also lacks uniformity. Navas Ruiz (1963) and Coste and Redondo (1965), for example, classify PCOS on so-called extralinguistic criteria such as the essential-accidental value of the verb. These criteria, sometimes criticized (Fente 1970), have nevertheless been followed by many other studies (Crespo 1949; Alba de Diego and Lunell 1988; Morimoto and Pavón Lucero 2007; RAE/ASALE 2009; Nilsson et al. 2014). Other semantic variables have also been used to organize this category. For instance, animacy, degree of intentionality, naturalness, radicalness, predictability of the change or degree of subject involvement. All these criteria are quite subjective and as a result, multiple variants, rules and, consequently, easily detectable exceptions occur.

Finally, the third area concerns PCOS verb-construction alternations. The combination of these verbs with lexical items is somehow unrestricted, in the sense that the same lexical item can be freely combined with any of these PCOS verbs. Recall, for instance, example (2) in Section 1; roja ‘red’ combines with hacerse ‘make.cl’, ponerse ‘put.cl’, volverse ‘turn.cl’, and quedarse ‘remain.cl’. Fente (1970) is one of the first studies to point out that the semantic limits between these verbs are diffuse and that their usages frequently overlap. Different reasons have been adduced for this overlapping: emphasis and expressivity (Crespo 1949), stylistic differences (Navas Ruiz 1963), and even dialectal variation (Eddington 1999). Other authors have offered alternative explanations for these alternations. Eberenz (1985) argues that the change has to be understood as a linear progression. When the change crosses a boundary, the transformation has been completed, and therefore, the rest of that line is to be taken as the result. This way of characterizing PCOS verbs on the basis of their role in the change process has been adopted by authors such as Alba de Diego and Lunell (1988), Conde Noguerol (2013), and Van Gorp (2017). The latter offers a cognitive semantic account where this progression is explained by means of the image schema metaphor changes are movements (Lakoff and Johnson 1999: 147), where the source-path-goal schema corresponds to the beginning, the development, and the achievement of the change of state.

This brief review clearly reveals the degree of difficulty that the analysis of PCOS verbs entails. A difficulty enhanced by the absence of a unified account of PCOS verbs. As a consequence, the implementation of these verbs in the language classroom is also challenging.

2.2 The explanation of PCOS verbs in SFL

The multiplicity of explanations for the behavior of PCOS verbs is mirrored in the wide variety of explanations found in SFL pedagogical materials Cheikh-Khamis (Submitted). Most of these materials follow the guidelines established in the Curriculum Plan of the Cervantes Institute (Instituto Cervantes 2007), which specifies CEFRL descriptors for the teaching of Spanish. The CPCI recommends the introduction of these verbs at the B2 level. It is at this moment when the student has to deal with at least five different verbs to express the notion of change, namely hacerse ‘make.cl’, volverse ‘turn.cl’, ponerse ‘put.cl’, quedarse ‘remain.cl’, and convertirse en ‘convert.cl in’.

Together with the intrinsic difficulty of having different verbs to describe a change of state, the lack of appropriate SFL materials make the learning of these verbs quite challenging for the learner. In a recent study, Cheikh-Khamis (Submitted) examines 35 SFL materials (27 textbooks and 8 grammar books) on the basis of 10 pedagogical criteria and concludes that the explanations and rules offered in most of these materials for PCOS are heterogeneous, imprecise, and insufficient to clarify their meaning and structure.

Some of these SFL materials for PCOS verbs are problematic instead of helpful. For example, a recurrent problem is the inclusion of different kinds of verbs of change under the same group. Most SFL materials include the teaching of four PCOS verbs —hacerse ‘make.cl’, volverse ‘turn.cl’, ponerse ‘put.cl’, and quedarse ‘remain.cl’— together with other verbs such as convertirse en ‘convert.cl in’, transformarse en ‘transform.cl in’ or llegar a (ser) ‘arrive to (be)’. These are all change verbs but the latter are both formally and semantically different from PCOS verbs. As far as their structure is concerned, they require a prepositional phrase headed by the preposition en ‘in, on, at’ or a ‘to’, whereas PCOS take a noun or an adjectival phrase. With respect to their meaning, these verbs do share the general meaning of change, but there are crucial differences, as illustrated in (3).

| Aquello | se | convirtió | en | un | zoológico |

| that | cl | converted | in | a | zoo |

| Aquello | se | volvió | un | zoológico |

| that | cl | turned | a | zoo |

‘That turned into a zoo’

Whereas in (3.a) the change is prototypically understood as physical (the place was turned into an establishment which maintains a collection of wild animals), in (3.b) the change can only be interpreted as metaphorical (the situation was quiet but it suddenly became a madhouse).

Another problem in SFL materials has to do with the explanations offered to guide students in their learning process of the PCOS. These materials usually offer a short description of how PCOS verbs work together with an illustrative example. The procedure itself is adequate, as it is a good combination of theory and practice. The problem, however, lies in the type of explanation. It is typically brief and above all, vague. Hedges such as a veces ‘sometimes’, normalmente ‘normally’ or suele ‘usually’, together with subjective evaluative information based on the length, willingness, and social appraisal of the change, find their way into these explanations. Such elements leave doors open to exceptions, contradictions, and alternative explanations. Let us examine a couple of examples.

Verdía et al. (2005: 183) characterize the PCOS verb hacerse ‘make.cl’ as “Suele presentar cambios que decide el sujeto” (‘It usually covers changes decided by the subject’). Unfortunately, this explanation does not hold for an instance such as (4), because becoming old is a natural process, impossible to be controlled by the subject.

| Nos | hacemos | mayores |

| cl.1pl | make.1pl | old.pl |

‘We are becoming old’

Similarly, volverse ‘turn.cl’ is described as an unavoidable change. In Verdía et al.’s (2005: 183) words, “A veces usamos volverse para cambios más definitivos y negativos” (‘Sometimes volverse is used for more permanent and negative changes’) (Chamorro-Guerrero et al. 2006). Once more, this explanation is incompatible with example (5), where the change is positive and its duration depends on how this person manages his fortune.

| Se | volvió | millonario | de | la | noche | a | la | mañana |

| cl.3sg | turned.3sg | millionaire | of | the | night | to | the | morning |

‘He became a millionaire overnight’

The two problems we have just highlighted seem to be quite widespread in SFL textbooks and reference materials, and they reflect the lack of uniformity in those theoretical descriptions discussed in Section 2.1. Now, the question is: why are PCOS verbs so problematic? And, secondly, is it possible to offer a unified account of PCOS verbs? The rest of this paper is devoted to tackling these questions.

3 Towards a unified constructional accountof PCOS verbs in Spanish

The critical overview in the previous sections clearly shows that the analysis and implementation of PCOS is not an easy task. As mentioned, earlier accounts lack a unanimous view on what these verbs are and how they work. It is therefore paramount to sort out these difficulties in order to pave the way for future SFL research. The solution may be possible if their main problem is tackled: their versatile syntactic and semantic nature. It is to this solution we now turn.

3.1 Two problems, one solution: The family of PCOS constructions

From a syntactic perspective, PCOS verbs are neither fully copulative nor predicative. They are mainly inaccusative but they also allow accusative structures. These multiple possibilities are partly responsible for the lack of a unified account. All PCOS are different and therefore, it is not possible to syntactically classify them in a single category without finding exceptions. A possible solution is to focus on those characteristics shared by these PCOS: their middle-voice structure and their intransitive, pronominal character. According to Castañeda Castro (2006), these characteristics are responsible for a shift in the focus of the PCOS verbs from the cause of the change onto the subject itself. On the one hand, the subject loses some of the control features typical in an active agent, but it nevertheless participates in the COS event. On the other hand, the subject itself is the locus of the COS described in the verb, since it is the one that experiments the change. In other words, the subject is simultaneously both agent and experimenter (see Maldonado 1999).

From a semantic perspective, the main challenge lies in the subtle meaning differences among PCOS verbs. Characteristics such as animacy, intentionality or gradualness have been used before, but they are not enough. We argue that it is necessary to consider the specific meaning of the PCOS verbs. This is crucial because the lexical verb is responsible for the subtle differences in meaning for the interpretation of the change-of-state event (that is, the speaker’s own view of how the change is like, see examples in (2)), and for the physical and metaphorical interpretation of the PCOS structure.

A possible way to capture these common and distinctive characteristics is to propose a “family of PCOS constructions” in the sense of Goldberg’s Construction Grammar (1995, 2006). Constructions are defined as form and meaning pairings which are conventionalized and usually non-compositional. In this framework, form and meaning are taken broadly, that is, “form” refers to any kind of structure (phonemic, morphosyntactic, prosodic, etc.) and “meaning” to any kind of semantic, pragmatic, and discursive information. The main idea is that constructions themselves are carriers of meaning independently from the specific linguistic items that saturate (i. e. integrate) them. On some occasions, the choice of linguistic items is restricted (e. g. tightly-bound idiomatic expressions), but on others, it is less constrained, which results in fully productive patterns. The latter may create a family of constructions that interact with each other by means of different mechanisms, called inheritance relations (see Golberg 1995: 72–81), such as polysemy links (same construction with different associated meanings), subpart links (a subpart is also a separate construction), metaphorical extension links (constructions related by metaphorical mappings), and instance links (a construction is a fully specified case of a construction).

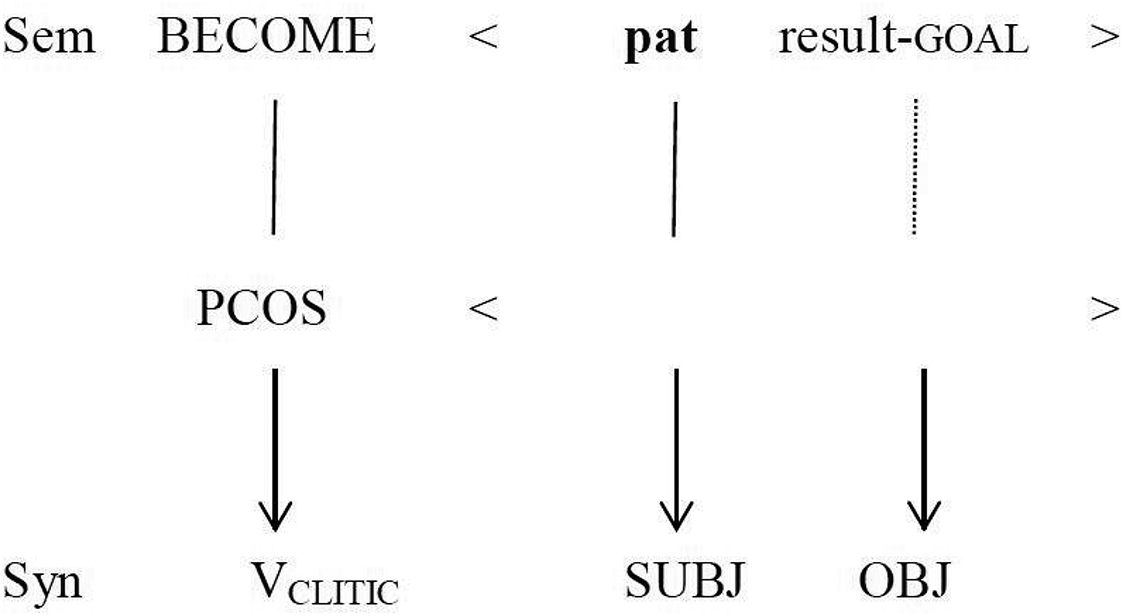

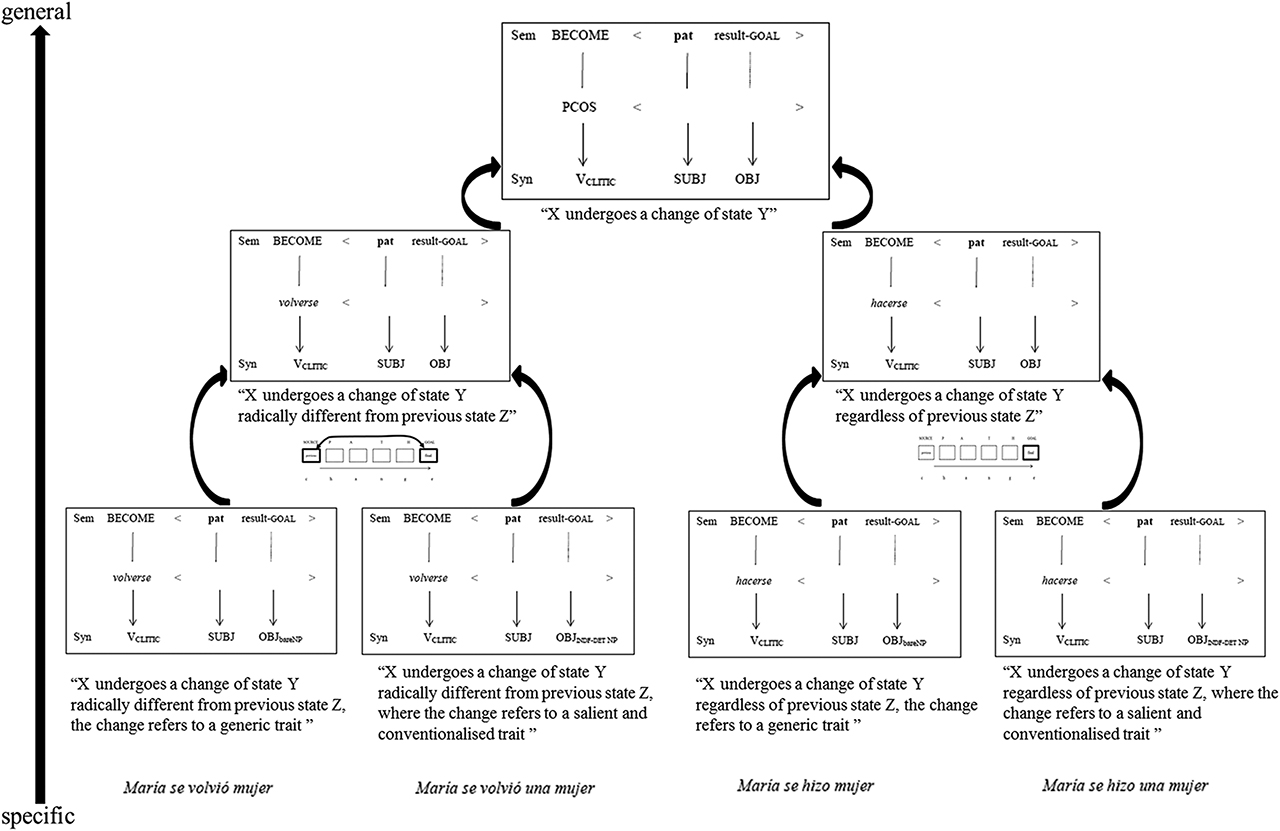

In the case of the PCOS construction, its general meaning is “X undergoes a change of state Y”. Notice that the interpretation of the change itself is intrinsically metaphorical since it is understood as a progression (path) from an initial state (source), up to the resulting final state (goal) (Lakoff and Johnson 1999; Van Gorp 2017). The PCOS construction form is represented as [SUBJ Vclitic OBJ]. The configuration of the PCOS construction is represented in Figure 1.

PCOS construction in Spanish.

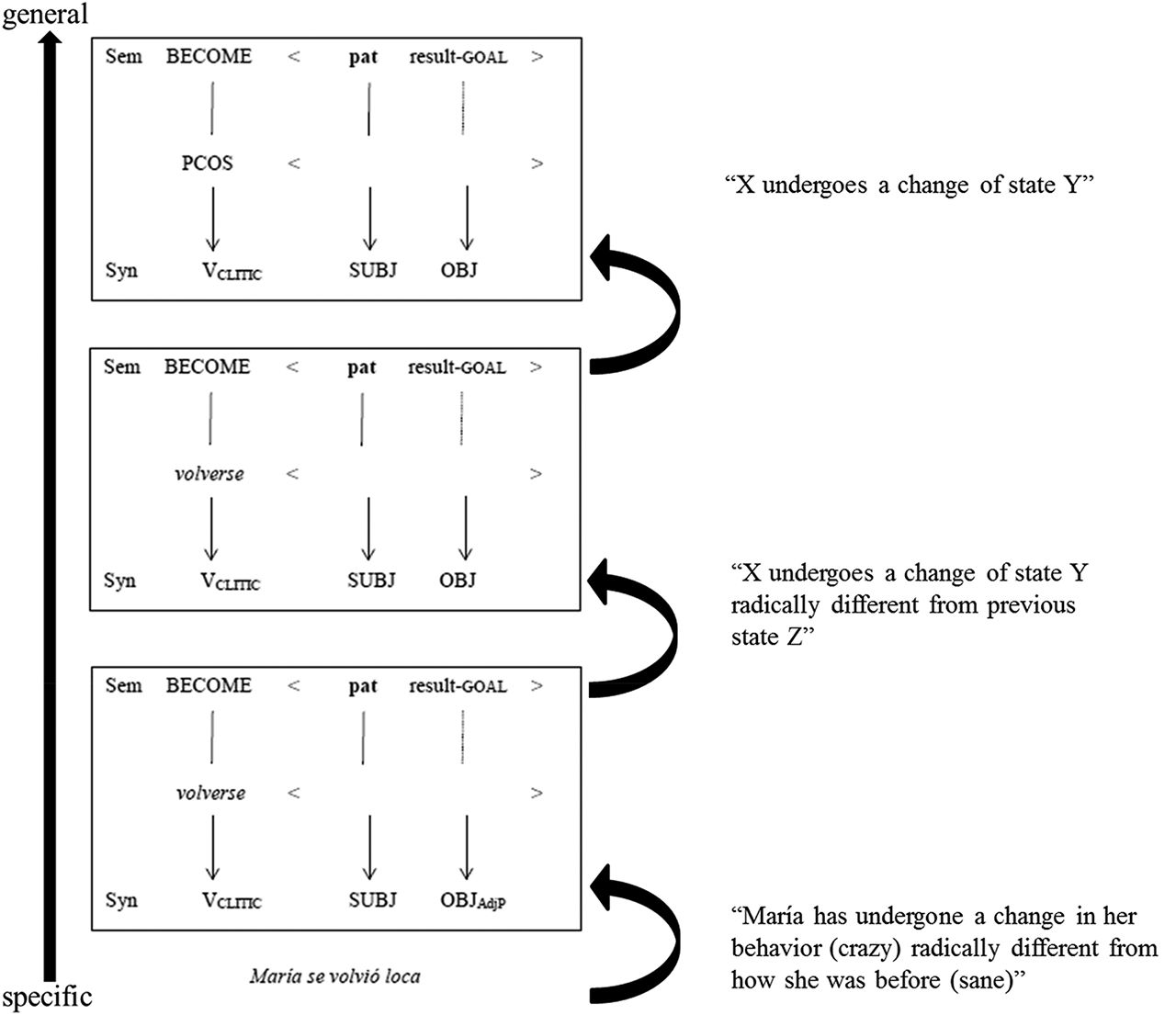

This general PCOS construction will then be saturated by different linguistic items that will shape its specific characteristics. All subconstructions will then inherit all the characteristics of the matrix construction by means of instance links, while adding the information of the specific lexical items.

We propose that these subconstructions can be organized in several levels of specificity. A first-level family of constructions is triggered by the choice of a PCOS verb and thus, by its meaning, as shown in (6).

Volverse ‘turn.cl’: change of state radically different from previous state

Hacerse ‘make.cl’: appearance of a new state regardless of previous state

Ponerse ‘put.cl’: momentary change of state, not necessarily intrinsic

Quedarse ‘remain.cl’: after the change takes place, the change of state is completed and will remain so.

The meaning of the lexical verb that saturates the V position is kept constant in all the possible instances of this construction. These first-level constructions are then further specified by means of different complements, usually adjectival phrases (e. g. volverse loco ‘turn.cl crazy’) or noun phrases (e. g. volverse un loco ‘turn.cl a madman’). This originates a second-level family of subconstructions that depend on the semantics of these complements. If needed, further levels of subconstructions could be identified.

In a nutshell, we propose a hierarchical family of PCOS constructions which at the lower levels inherit the meaning and characteristics of the previous level subconstruction by means of instance links. The idea is to create a bottom-up approach that captures both the specificity of fully-saturated constructions (e. g. María se volvió loca) as well as the more general abstract patterns (e. g. [Subject volverse AdjP] → [Subject PCOS-verb Object]). Figure 2 schematizes how this family of PCOS constructions works.

A family of PCOS constructions in Spanish.

This type of bottom-up family of constructions is meant to provide the student with the necessary tools to interpret the meaning of PCOS constructions, and not only the general meaning of a change of state, but also the specific nuances of each subconstruction. The goal is to provide a unique and motivated account of PCOS constructions to facilitate the SFL learner’s processing and understanding.

3.2 The family of PCOS constructions into practice: [Subject hacerse/volverse ObjectNP]

With the purpose of testing the validity of the family of PCOS constructions, we undertook a corpus study that focuses on two PCOS verbs, hacerse ‘make.cl’ and volverse ‘turn.cl’, with NP complements.

3.2.1 Corpus

In order to extract examples, we use the open-access Corpus del Español del Siglo XXI (CORPES XXI, ‘Corpus of the twenty-first Century Spanish’), from the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language. The CORPES XXI is a 25 million-word reference corpus that contains written and oral texts in Spanish from Spain, America, the Philippines, and Equatorial Guinea, compiled between 2001 and 2012.

Our corpus was built in four stages. First, the lemmas (hacer, volver) were individually searched together with all the proclitic forms (e. g. se hizo cura ‘he became a priest’), and second, with the enclitic forms as it corresponds to non-finite forms (e. g. volverse cura ‘to become a priest’). In both searches, we added a search for right-adjacent nouns. Resulting concordances were downloaded in text format and filtered with the AntConc3 tool to proceed with the count of types and tokens. It is at this third stage when unsuitable occurrences were manually discarded, such as cases where the verbs hacerse ‘make.cl’ and volverse ‘volver.cl’ do not take a pseudocopulative change-of-state meaning, as in se hizo daño (cl.3sg made.3sg harm) ‘s/he hurt himself’ or se volvió a casa (cl.3sg turned.3sg to house) ‘s/he returned home’. Accusative (me vuelves loca (cl.1sg turn.2sg crazy) ‘you turn me crazy’), reciprocal (nos hicimos caricias (cl.1pl made.1pl caress ‘we cuddled each other’), and impersonal (se hacen fotocopias (cl.3sg made.3pl photocopies) ‘photocopies are made here’) pronominal uses were also eliminated. Once the corpus was ready, we further categorized instances into two groups, according to the structure of the NP, i. e. bare NP or NP with determiner.

The result is a corpus that contains a total of 1,505 types and 4,485 tokens. We consider tokens of the same type utterances that share the same lexical verb (regardless of other morphological information, e. g. tense, mood, etc.) and the same kind of NP. For instance, María se hizo vegetariana ‘María became vegetarian’ and Clara se ha hecho vegetariana ‘Clara has become vegetarian’.

3.2.2 Analysis

Our constructional approach proposes a multi-level family of PCOS constructions. Therefore, in this section, we will examine each of these levels from the most general to the most specific. The goal is to test the role and meaning of the items that saturate each construction in order to establish regularities that might offer the SFL student a motivated account of the PCOS construction in Spanish.

As far as the quantitative data are concerned, the distribution of examples in each construction is summarized in Table 1.

Hacerse/volverse+NP in corpus.

| hacerse/volverse+NP | # types (%) | # tokens (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| hacerse+NP | 606 (32.70%) | 2546 (56.75%) | |

| hacerse+∅+noun | 581 (95.87%) | 2478 (97.32%) | |

| hacerse+det+noun | 25 (4.12%) | 68 (2.67%) | |

| volverse+NP | 1247 (67.29%) | 1940 (43.24%) | |

| volverse+∅+noun | 834 (66.88%) | 1347 (69.43%) | |

| volverse+det+noun | 413 (33.12%) | 593 (30.56%) | |

| Total | 1853 | 4486 | |

Quantitative data in Table 1 show that volverse+NP is the construction with the highest variety of types (1247, 67.29% vs. 606, 32.70%), but that hacerse+NP is the construction with more tokens per type (2546, 56.75% vs. 1940, 43.24%). In both cases, the construction with the bare NP is more frequent, but this preference is more acute in the case of hacerse+NP. This means that the construction hacerse/volverse with a determiner is not very productive which is an interesting fact from a teaching perspective, as will be discussed in the next section.

In general, these figures seem to indicate that volverse+NP is structurally less restrictive than hacerse+NP, but it also shows that the usage of hacerse+NP is more conventionalized. In other words, hacerse+NP presents a smaller number of types, but they are widely used. For example, a quick look at the examples in hacerse+bare NP reveals that hacerse realidad (make.cl reality) ‘to become real’ and hacerse amigos (make.cl friends) ‘to become friends’ cover over a third of all the tokens in this subconstruction (35,55%); 534 tokens and 347 tokens, respectively. This suggests that the degree of idiomaticity, i. e. how fixed the expression is, is higher in hacerse+NP. Both characteristics, frequency and conventionalization, are key issues in SLA (see, Ellis 2002) and therefore, this kind of instantiations of the subconstruction could play an important role in the acquisition of Spanish.

As far as qualitative data are concerned, we are going to focus on two subcases to illustrate the explanatory power of the family of the PCOS constructions. One examines instances where both verbs, hacerse ‘make.cl’ and volverse ‘turn.cl’, select the same lexical noun to fill the bare NP. The other explores instances of the subconstructions with bare NPs and with NP+determiner.

The goal of the first subcase is to show the way the subconstruction works at the verbal level. In our corpus, out of the 1,505 different nouns, 209 (13.71%) occur with both hacerse ‘make.cl’ and volverse ‘turn.cl’. [2] This group of nouns is suitable to show the role of each verbal subconstruction, since this is the level where the difference lies. Let us examine some examples in (7–9).

| Entonces | el | agua | se | volvió | piedra [PVNZ-0973] [3] |

| then | the | water | cl.3sg | turned.3sg | stone |

‘At that moment water turned into stone’

| El | corazón | se | hace | piedra [PHNZ-1226] |

| the | heart | cl.3sg | makes | stone |

‘The heart turns into stone’

| Como | una | oruga | que | se | vuelve | mariposa [PVNZ-0697] |

| as | a | caterpillar | that | cl.3sg | turns | butterfly |

‘As a caterpillar when she turns into a butterfly’

| El | gusano | se | hace | mariposa | o | quizá | al |

| the | worm | cl.3sg | makes | butterfly | or | maybe | to.the |

| revés [PHNZ-6722] | |||||||

| opposite |

‘The worm turns into a butterfly or maybe the opposite’

| Imagínate, | si | no | fuera | por | eso | ¡el | pueblo | americano |

| imagine | if | not | were | for | that | the | village | american |

| entero | se | volvía | fidelista! [PVNZ-0503] |

| whole | cl.3sg | turned.3sg | fidelist |

‘Just imagine! If it weren’t for that, the whole American nation would have become a supporter of Fidel Castro!’

| Pepito | se | hizo | fidelista | en | el | 59 | [PHNZ-0551] |

| pepito | cl.3sg | made.3sg | fidelist | in | the | 59 |

‘Pepito became a supporter of Fidel Castro in 59’

In these examples, the subjects —heart/water; caterpillar/worm; the American nation/Pepito— undergo a change that results into a different state —stone; butterfly; a supporter of Fidel Castro. This meaning is inherited from the PCOS matrix construction, which is in turn expanded with that of the verbal subconstruction. In all the a. versions, the volverse subconstruction adds the connotation of a change that radically differs from the previous state. In all the b. versions, the change in the hacerse subconstruction refers to the new state but without profiling the previous one. We argue that these are the key differences between these two subconstructions, rather than the involuntary and swift, and consequently negative, character of the change in the volverse construction, or the positive character of the change in the hacerse construction. These traits are very subjective and cannot be applied to all examples. For instance, to turn into a butterfly cannot be considered either positive or negative, as it is just a natural process.

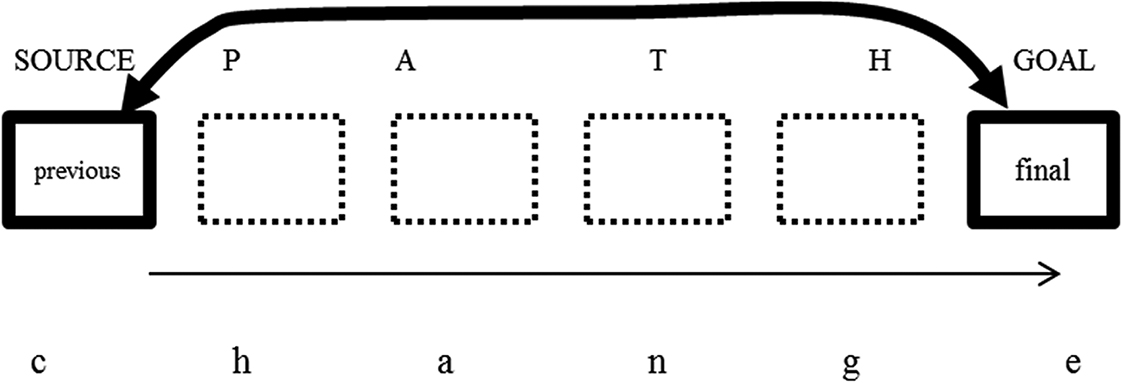

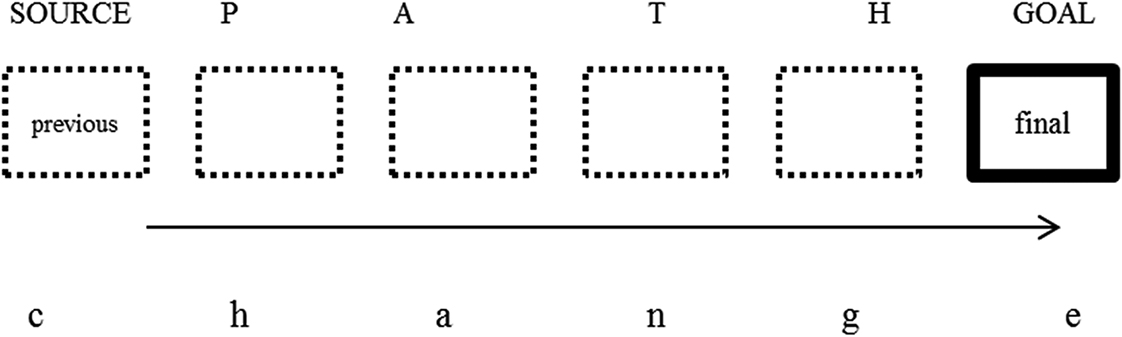

Instead, we suggest that each construction establishes, and therefore profiles, a different relation between the previous and the new state. Similarly to Van Gorp’s (2017) proposal, we also argue that a PCOS construction can be described as a source-path-goal image-schema-based metaphor; however, we propose that the element profiled in each subconstruction corresponds to a different part of the image schema, or in general terms, to a different part of the change-of-state event. Figures 3 and 4 capture these differences. The bold line represents the parts of the event profiled in each subconstruction.

Volverse PCOS subconstruction.

Hacerse PCOS subconstruction.

The second subcase we are going to briefly discuss focuses on a higher level of specificity: the structure of the NP. As mentioned above, PCOS subconstructions may take two types of NPs as complements, a bare NP and an NP with an (indefinite) determiner. We have already shown that these two possibilities differ sharply as far as their frequency and prototypicality, but now we would like to explore whether the presence or lack of a determiner triggers meaning differences. Examples (10–11) illustrate these contrasts, where both verbs and nouns are kept constant, but what changes is the presence or absence of the indefinite determiner un (-a, -os, -as) (abbreviated as indf.det (-m.sg, -f.sg, -m.pl, -f.pl)).

| […] como | si | temiera | hacerse | grande, | o |

| […] as | if | was.afraid | make.cl.3sg | big | or |

| hacerse | mujer [PHNZ-0983] |

| make.cl.3sg | woman |

‘She was kind of afraid of becoming big, or becoming a woman’

| La | niña | está | bien, | haciéndose | una | mujer |

| the | girl | is | ok | making.cl.3sg | indf.det.f.sg | woman |

| para | el | futuro [PHNI-0035] |

| for | the | future |

‘The girl is ok, just becoming a woman for the future’

| Se | vuelven | señores | los | ladrones [PVNZ-1193] |

| cl.3pl | turn.3pl | gentlemen | the | thieves |

‘Thieves become gentlemen’

| Se | volvería | un | señor | en | pantuflas | y |

| cl.3sg | turned.3sg | indf.det.m.sg | gentleman | in | slippers | and |

| pijama [PVNI-0546] | ||||||

| pajamas |

‘He would become a gentleman in slippers and pajamas’

In (10), both examples refer to a change related to womanhood, but they profile different aspects of it. In (10a), hacerse mujer relates to the biological evolutive change from girl to woman. In (10b), hacerse una mujer does not refer to the biological change, but to the acquisition of all those traits that characteristically differentiate a female adult from a younger one. Similarly, in (11a), volverse señores refers to a change in behavior (represented by the social class), whereas in (11b), volverse un señor focuses on those properties typical of a certain social class, the bourgeoisie.

Our proposal is that the use of the PCOS subconstruction with a NP+determiner triggers a different reading from the bare NP. In the case of bare NPs, the referential meaning of the noun corresponds to a generic interpretation where the change does not refer to any specific characteristic of the noun but to the general class. For the NPs with a determiner, on the contrary, the meaning of the noun refers to the salient prototypical characteristics that may help in differing one class from another.

Examples (12–14) add further evidence to this proposal.

| Los | labios | de | Mariana | se | volvieron | un |

| the | lips | of | mariana | cl.3pl | turned.3pl | indf.det.m.sg |

| hilo [PVNI-0266] | |||||

| thread |

‘Mariana’s lips became very slender and thin’

| Sacks […] | ahora | con | este | libro | se | vuelve | un | Darwin |

| sacks […] | now | with | this | book | cl.3sg | turns | indf.det.m.sg | darwin |

| de | sus | tiempos [PVNI-0155] |

| of | his | times |

‘Now, with this book, Sacks […] becomes the new Darwin’

| Se | volvían | unos | Judas | sin | árbol | donde |

| cl.3pl | turned.3pl | indf.det.m.pl | judas | without | tree | where |

| colgarse [PVNI-0310] | ||||||

| hang.cl |

‘They became like Judas but with no tree to hang from’

In (12), Mariana’s lips did not turn into a thread but, according to the speaker’s own perspective, they became slender and thin. In (13), Sacks becomes like Darwin, that is, an influential person (scientist) thanks to a revolutionary book (theory). In (14), these people become distrustful like Judas (only worse, since they did not have a chance to redeem themselves).

In short, in the NP with determiner PCOS subconstruction, the noun is metonymically interpreted thanks to the indefinite determiner. [4] The noun stands for its most salient property. This subconstruction is quite flexible since it works with virtually any noun. There is only one important condition: the shared encyclopedic knowledge, i. e. the speakers’ conventionalized knowledge (see, Valenzuela 2017). The second part of the title in this paper is an illustrative example. “[W]ithout turning into a Barbie” refers to the salient characteristics of this famous doll. However, in order to correctly interpret which characteristics are salient, it is necessary to know that Barbie represents a thin and voluptuous blond woman as well as a stereotypical superficial person who cares about her physical aspect more than anything else.

In sum, the use of the indefinite determiner triggers the most salient and prototypical meaning. However, which part of the meaning gets taken as prominent depends on the encyclopedic knowledge that speakers have in common.

4 Conclusions: The PCOS construction in Spanish and beyond

This paper had two goals: (i) to critically review PCOS verbs in specialized L1 and L2 literature in Spanish and (ii) to build a construction grammar-based explanation that could offer a unified account of their linguistic behavior, suitable for pedagogical purposes.

With respect to the first goal, it has been shown that these verbs are problematic due to their versatile and complex nature, syntactically as well as semantically. L1 and L2 literature has focused on three main areas— the categorization of PCOS verbs, the internal classification of PCOS verbs, and the explanation of PCOS verb construction alternations —. Despite all efforts, these studies suffer from three main problems: the lack of a unanimous explanation, the existence of many exceptions to general rules, and a neglect of semantic nuances. These problems have been carried over onto SFL materials, and have reinforced the already difficult and elusive nature of these verbs.

In order to tackle these issues, we have proposed a family of PCOS constructions in Spanish as represented in Figure 5.

A constructional approach to volverse ‘turn.cl’ and hacerse ‘make.cl’.

The idea is that constructions with different levels of specificity inherit the meaning of the general constructions above them, while also contributing new semantic content. The more saturated the (sub)construction is, the more restricted its meaning will be.

The family of constructions proposed in Figure 5 will offer the student a template (a morphosyntactic structure with meaning), that could be filled in with different lexical items. This template will offer a two-way learning mechanism. On the one hand, it helps identifying the general meaning of the construction, regardless of the specific lexical items; that is, a top-bottom (general-specific) process. On the other, it provides a bottom-up learning process. The student encounters a specific utterance of the PCOS construction, which s/he can identify as belonging to the PCOS construction. The more utterances the student encounters, the more entrenched this construction could become (see Blumental-Dramé 2012).

Our multi-level family of PCOS constructions was tested on a corpus of 4,485 utterances. Quantitative results show that volverse+NP is structurally less restrictive than hacerse+NP. The usage of hacerse+NP, on the other hand, is more conventionalized; i. e. it presents a smaller number of types, but those are widely used.

Quantitative information is not just important from a descriptive viewpoint: it is crucial when it comes to decide what and when to teach. The PCOS construction is not only ubiquitous in Spanish but also exhibits a rich collection of subconstructions. Once the problem of how to explain this construction is taken care of, an equally-necessary issue is to decide a temporal sequence for the teaching of its subconstructions. The quantitative analysis in this paper may offer some hints. It has been shown that the subconstruction hacerse/volverse with a bare NP is the most frequent both in types and tokens. This is important for two reasons. First, research in SLA in cognitive linguistics (Ellis 2002; Ellis and Ferreira-Junior 2009; Cadierno and Eskilden 2015) has shown that the frequency of input is crucial in the acquisition of a second language. The more the learner is exposed to a kind of construction, the more bound it is to become entrenched, and therefore, acquired. And second, this subconstruction is the most prototypical, the one that better represents the whole category of PCOS constructions, and therefore, it will help the student to understand how the category works (Achard and Niemeier 2004; Ellis and Cadierno 2009; De Knop et al. 2010). It is for these reasons that it would be advisable to start with this subconstruction first, and later with the rest of the possible subconstructions.

Qualitative data, on the other hand, have shown that subconstructions at each level add further information beyond the general meaning of the PCOS construction “X undergoes a change of state Y”. At the verbal construction level, if the verb that saturates the subconstruction is volverse ‘turn.cl’, the change profiles the radical differences that exist between the old and the new state. If the verb is hacerse ‘make.cl’, the change profiles the appearance of a new state. Further down, at the object constructional level, if the NP lacks a determiner the change highlights the generic meaning of the noun. If the NP has an indefinite determiner, this triggers a metonymic reading whereby the salient and conventionalized characteristics of the noun are profiled. The regularity of these meaning patterns in each constructional level could also be very useful in SFL. Regardless of the specific lexical items involved in each particular utterance, these constructional templates offer a motivated explanation of what the structures mean (Boers and Lindstromberg 2008, Boers and Lindstromberg 2009; Goldberg and Casenhiser 2008), and at the same time, they avoid possible “exceptions to the rule” that may arise in specific instantiations. Further research is no doubt needed, both in the academic field and the language classroom alike.

The constructional approach to the PCOS in Spanish that we present in this paper offers informed options for pedagogical implementation that focus on giving SFL students a pathway for holistic, structured, and motivated comprehension. We are aware that didactic transposition (Chevallard 1985) is a challenge, and that while some of the hints we have provided might not be ultimately successful in a classroom setting, it is our hope that this model will help both students and language instructors understand how someone can become a woman without turning into a Barbie.

Funding statement: This research has been supported by Grant FFI2017–82460–P from the Spanish State Research Agency and the European FEDER Funds. Many, many warm thanks to the editors, Reyes Llopis-García and Alberto Hijazo-Gascón, for their patience, comments, and above all, for turning a late-night Geordie chitchat into this wonderful special issue.

References

Achard, Michel & Susanne Niemeier (eds.). 2004. Cognitive linguistics, second language acquisition and foreign language teaching. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110199857Suche in Google Scholar

Alba de Diego, Vidal & Karl-Axel Lunell. 1988. Verbos de cambio que afectan al sujeto en construcciones atributivas. In Pedro Peira, Pablo Jauralde, Jesús Sánchez Lobato & Jesús Urrutia (eds.), Homenaje a Alonso Zamora Vicente. Volumen I: Historia de la lengua. El español contemporáneo, 343–359. Madrid: Castalia.Suche in Google Scholar

Blumenthal-Dramé, Alice. 2012. Entrenchment in usage-based theories. What corpus data do and do not reveal about the mind. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110294002Suche in Google Scholar

Boers, Frank & Seth Lindstromberg (eds.). 2008. Cognitive linguistic approaches to teaching vocabulary and phraseology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110199161Suche in Google Scholar

Boers, Frank & Seth Lindstromberg. 2009. Optimizing a lexical approach to instructed second language acquisition. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230245006Suche in Google Scholar

Bordignon, Frédérique. 2003. Un approche cognitive du potentiel sémantique et constructionnel du verbe casser. Clermont-Ferrant: Blaise Pascal-Clermont II University PhD Dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Bybee, Joan & David Eddington. 2006. A usage-based approach to Spanish verbs of ‘becoming’. Language 82(2). 323–355.10.1353/lan.2006.0081Suche in Google Scholar

Cadierno, Teresa & Soren W. Eskildsen (eds.). 2015. Usage-based perspectives on second language learning. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110378528Suche in Google Scholar

Casares, Julio. 1969 [1950]. Introducción a la lexicografía moderna. Madrid: CSIC.Suche in Google Scholar

Castañeda Castro, Alejandro. 2006. Querían dormirlo, se ha dormido, está durmiendo. Gramática cognitiva para la presentación de los usos del se en clase de ELE. Mosaico 18. 13–20.Suche in Google Scholar

Chamorro-Guerrero, María Dolores, Gracia Lozano-López, Pablo Martínez-Gila, Beatriz Muñoz-Álvarez, Francisco Rosales-Varo, José Plácido Ruiz Campillo & Guadalupe Ruiz Fajardo. 2006. Abanico. Libro del alumno. Barcelona: Difusión.Suche in Google Scholar

Cheikh-Khamis, Fátima. Submitted. El tratamiento de los verbos de cambio en los materiales de enseñanza de español como lengua extranjera.Suche in Google Scholar

Chevallard, Yves. 1985. La transposition didactique; du savoir savant au savoir enseigné. Paris: La Pensée Sauvage.Suche in Google Scholar

Conde Noguerol, María Eugenia. 2013. Los verbos de cambio en español. La Coruña: University of La Coruña PhD dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Corpas Pastor, Gloria. 1996. Manual de fraseología española. Madrid: Gredos.Suche in Google Scholar

Coste, Jean & Agustin Redondo. 1965. Syntaxe de l’espagnol moderne. Paris: Societé d’Edition d’Enseignement Superieur.Suche in Google Scholar

Crespo, Luis. 1949. To become. Hispania 32. 210–212.10.2307/333076Suche in Google Scholar

Culicover, Peter & Johannes Dellert. 2008. Going postal: The architecture of English change of state verbs. https://www.asc.ohiostate.edu/culicover.1/Publications/Tufts%20workshop,%20going%20Postal,%20v2a.pdf. (accessed 13 December 2017).Suche in Google Scholar

De Knop, Sabine, Frank Boers & Antoon De Rycker (eds.). 2010. Fostering language teaching efficiency through cognitive linguistics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110245837Suche in Google Scholar

Demonte, Violeta. 1994. La semántica de los verbos de cambio. In Beatriz Garza Cuarón, José Antonio Pascual & Alegría Alonso González (eds.), II Encuentro de lingüistas y filólogos de España y México, 535–563. Salamanca: Junta de Castilla y León & Universidad de Salamanca.Suche in Google Scholar

Dubois, Jean & Françoise Dubois-Charlier. 1997. Les verbes français. Paris: Larousse-Bordas.Suche in Google Scholar

Duée, Claude & Peter Lauwers. 2010. Une étude contrastive de “se faire/hacerse” + adjectif. Synergies Espagne 3. 23–31.Suche in Google Scholar

Eberenz, Rolf. 1985. Aproximación estructural a los verbos de cambio en Iberorromance. Linguistique Comparée et Typologie des Langues Romanes 2. 460–475.Suche in Google Scholar

Eddington, David. 1999. On ‘becoming’ in Spanish: A corpus analysis of verbs expressing change of state. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 18. 23–35.Suche in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 2002. Frequency effects in language processing: A review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 24(2). 143–188.10.1017/S0272263102002024Suche in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. & Teresa Cadierno. 2009. Constructing a second language: Introduction to the special section. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 7. 111–139.10.1075/arcl.7.05ellSuche in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. & Fernando Ferreira-Junior. 2009. Constructions and their acquisition: Islands and the distinctiveness of their occupancy. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 7. 187–220.10.1075/arcl.7.08ellSuche in Google Scholar

Fente, Rafael. 1970. Sobre los verbos de cambio o devenir. Filología Moderna 38. 151–171.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández Leborans, María Jesús. 1999. La predicación: las oraciones copulativas. In Ignacio Bosque & Violeta Demonte (eds.), Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, 2357–2460. Madrid: Espasa.Suche in Google Scholar

Fillmore, Charles J. 1970. The grammar of hitting and breaking. In Roderick Jacobs & Peter Rosenbaum (eds.), Syntax and semantics 8: Grammatical relations, 59–81. New York: Academic Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Firth, John Rupert. 1957. Papers in linguistics 1934–1951. London: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 1995. Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at work. The nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268511.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Goldberg, Adele E. & David Casenhiser. 2008. Construction learning and second language acquisition. In Peter Robinson & Nick C. Ellis (eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition, 197–215. London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Huddleston, Rodney & Geoffry K. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316423530Suche in Google Scholar

Instituto Cervantes. 2007. Plan Curricular del Instituto Cervantes. Los niveles de referencia para el español. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.Suche in Google Scholar

Koike, Kazumi. 2001. Colocaciones léxicas en el español actual: estudio formal y léxico-semántico. Madrid: Universidad de Alcalá/University of Takushoku.Suche in Google Scholar

Laca, Brenda. 1999. Presencia y ausencia de determinante. In Ignacio Bosque & Violeta Demonte (eds.), Gramática descriptiva de la lengua española, 891–928. Madrid: Espasa.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. New York: Basic Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Lauwers, Peter & Claude Duée. 2010. Se faire/hacerse + attribut. Une étude contrastive de deux semi-copules pronominales. Revue Romance Philology 64(1). 99–132.10.1484/J.RPH.3.29Suche in Google Scholar

Lauwers, Peter & Claude Duée. 2011. From aspect to evidentiality: The subjectification path of the French semi-copula se faire and its Spanish cognate hacerse. Journal of Pragmatics 43(4). 1042–1060.10.1016/j.pragma.2010.09.013Suche in Google Scholar

Levin, Beth. 1993. English verb classes and alternations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Levin, Beth & Malka Rappaport Hovav. 1995. Unaccusativity: At the syntax-lexical semantics interface. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lorenzo, Emilio. 1970. Sobre los verbos de cambio. Filología Moderna 38. 173–197.Suche in Google Scholar

Maldonado, Ricardo. 1999. A media voz. Problemas conceptuales del clítico se en español. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas, UNAM.Suche in Google Scholar

Matte Bon, Francisco. 1992. Gramática comunicativa del español. Tomo II. Barcelona: Difusión.Suche in Google Scholar

Morimoto, Yuko & María Victoria Pavón Lucero. 2007. Los verbos pseudo-copulativos del español. Madrid: Arco Libros.Suche in Google Scholar

Navas Ruiz, Ricardo. 1963. Ser y Estar. Estudio sobre el sistema atributivo del español. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca.Suche in Google Scholar

Nilsson, Kåre, Ingmar Söhrman, Santiago Villalobos & Johan Falk. 2014. Verbos copulativos de cambio. In Susana Fernández & Johan Falk (eds.), Temas de gramática española para estudiantes universitarios. Una aproximación cognitiva y funcional, 145–170. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Porroche Ballesteros, Margarita. 1988. Ser, estar y verbos de cambio. Madrid: Arco Libros.Suche in Google Scholar

Portolés Lázaro, José. 1994. La metáfora y la lingüística: los atributos metafóricos con un enfático. In Violeta Demonte (ed.), Gramática del español, 531–556. México: El Colegio de México.Suche in Google Scholar

Pountain, Christopher. 1984. How “become” became in Castilian. In Richard A. Cardwell (ed.), Essays in honour of Robert Brian Tate from his colleagues and pupils, 101–111. Nottingham: University of Nottingham.Suche in Google Scholar

RAE/ASALE. 2009. Nueva gramática de la lengua española. Madrid: Espasa.Suche in Google Scholar

Rappaport Hovav, Malka & Beth Levin. 2005. Change-of-state verbs: Implications for theories of argument projection. In Nomi Erteschik-Shir & Tova Rapoport (eds.), The syntax of aspect, 274–254. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199280445.003.0013Suche in Google Scholar

Rodríguez Arrizabalaga, Beatriz. 2001. Verbos atributivos de cambio en español e inglés contemporáneos. Un análisis contrastivo. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva.Suche in Google Scholar

Saint-Dizier, Patrick. 1999. Alternations and verb semantic classes for French: Analysis and class formation. In Patrick Saint-Dizier (ed.), Predicative forms in natural language and in lexical knowledge bases, 1–52. Amsterdam: Kluwer.10.1007/978-94-017-2746-4Suche in Google Scholar

Valenzuela, Javier. 2017. Meaning in English: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316156278Suche in Google Scholar

Van Gorp, Lise. 2017. Los verbos pseudo-copulativos de cambio en español. Estudio semántico-conceptual de hacerse, volverse, ponerse, quedarse. Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert.10.31819/9783954876310Suche in Google Scholar

Verdía, Elena, Javier Fruns, Felipe Martín, Mila Ortín & Conchi Rodrigo. 2005. En acción 2. Libro del alumno. Madrid: Enclave ELE.Suche in Google Scholar

Vázquez, Glòria, Ana Fernández & María Antonia Martí. 2000. Clasificación verbal. Alternancias de diátesis. Lleida: Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida.Suche in Google Scholar

Wright, Saundra K. 2002. Transitivity and change of state verbs. Proceedings of the Twenty-eighth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 28. 339–350.10.3765/bls.v28i1.3849Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Applied cognitive linguistics and foreign language learning. Introduction to the special issue

- Articles

- Description, acquisition and teaching of polysemous verbs: The case of quedar

- Mr Bean exits the garage driving or does he drive out of the garage? Bidirectional transfer in the expression of Path

- A cognitive approach to teaching deictic motion verbs to German and Italian students of Spanish

- “How to become a woman without turninginto a Barbie”: Change-of-state verbconstructions and their role in Spanish as a Foreign Language

- Exploring the pedagogical potential of vertical and horizontal relations in the constructicon:The case of the family of subjective-transitive constructions with decir in Spanish

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Applied cognitive linguistics and foreign language learning. Introduction to the special issue

- Articles

- Description, acquisition and teaching of polysemous verbs: The case of quedar

- Mr Bean exits the garage driving or does he drive out of the garage? Bidirectional transfer in the expression of Path

- A cognitive approach to teaching deictic motion verbs to German and Italian students of Spanish

- “How to become a woman without turninginto a Barbie”: Change-of-state verbconstructions and their role in Spanish as a Foreign Language

- Exploring the pedagogical potential of vertical and horizontal relations in the constructicon:The case of the family of subjective-transitive constructions with decir in Spanish