Abstract

Caldasia, a journal published by the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, was the arena of language tensions originating in scientific exchanges in the mid-20th century at a time when English was in the process of affirming its place as the lingua franca of science. In the 1940s, the journal showed indications of a multilingual process reflected in the considerable presence of US authors and their articles in English published in its pages. This paper examines Caldasia’s communication circuit, specifically the negotiations that emerged between the editor and US researchers when deciding on the most appropriate language for publishing the articles. Selecting the language of the articles was considered by them as a critical element in determining the geographical scope of the journal, positioning Caldasia as a regional or international journal. This analysis demonstrates how the tension between multilingual repertoires and linguistic ideologies was experienced in Caldasia. The editor promoted Caldasia as a multilingual journal and to reach this objective the editor managed the multilingual repertoires of the authors in the journal. The case of Caldasia indicates that the Anglicization process of science in the XX century required intense scientific contacts carried out in non-English-speaking spaces; multilingualism was one of the strategies by which English became a globally accepted language.

1 Introduction

In terms of language, during the 20th century science underwent significant transformations that reflected changes that were taking place at the time in the geopolitics of scientific knowledge: English replaced French as the lingua franca of science (Gordin 2015).

Thus, while English became an international expression of scientific knowledge, languages such as Spanish, Portuguese, Mandarin, French and German etc., have since then been associated with the local or regional level mainly due to the fact that articles published in these languages are usually not very visible, i.e., they attract fewer citations than articles published in English (Meneghini and Packer 2007).[1]

In the current system for evaluating science, researchers are frequently required to publish the results of their research in journals with a high impact factor, which are generally English-medium journals, if they want an academic promotion, salary increase or research funds (Curry and Lillis 2017).

In this context, the predominance of English as the lingua franca of science in many national research systems has been interpreted as a desired phenomenon that should also be strengthened. Under this vision, the internationalism of English is conceived as the engine and expression of scientific communalism,[2] i.e., it has streamlined the circulation and exchange of ideas among researchers located in vastly different geographical areas and with different native language skills (Haller 2019: 343–344).

However, parallel to this vision, critical positions have also emerged according to which the trend towards a monolingual science based on English leads to idiomatic injustice in science (Nygaard 2019; Politzer-Ahles et al. 2016), an injustice that is mainly experienced by non-English speakers and editors of journals published in non-English speaking countries: (i) non-English speakers face particular challenges to have their research findings published in English media journals: (a) linguistic challenges (Lillis and Curry 2010; Mazenod 2018), (b) challenges in applying a linguistically defined style of academic writing (Shehata and Eldakar 2018) and (c) challenges in their institutional environments, generally they do not have sufficient resources to access international scientific networks, acquire cutting-edge scientific material or obtain linguistic intermediation support (Lillis and Curry 2010; Nygaard 2019). A set of challenges that translate into the fact that non-English speakers in particular must invest a greater amount of additional time, energy, effort, and resources to publish their findings in English media journals (Bennett 2014; Curry and Lillis 2017).

(ii) Both editors and researchers in non-English-speaking regions must face significant tensions as to the most appropriate language in which to publish research results, considering the target audience by using a language. Should they choose objective communication with a global audience or a local one? (Harbord 2017). For example, in the case of authors in Latin American countries, publishing articles in Spanish or Portuguese implies that they are more likely to be recognized and used by other researchers in the Ibero-American region, but at the same time, they go virtually unnoticed by the English-speaking scientific community (Gibbs 1995). On the other hand, publishing in English also has its tradeoff. Although the use of English makes it more likely that the English-speaking scientific community will read the article, this also means that many of the scientists, institutions and civil society in the region of origin of the research does not have the language skills to understand these results (Martín et al. 2014). This paradox was expressed by Hanafi (2011) as publish globally and perish locally versus publish locally and perish globally.

In this perspective, the editors acknowledge that the language of the articles is also a significant indicator of the journal’s reach, since the language allows the journal to be associated with its potential readership. In the case of a journal published in Latin America with articles exclusively written in Spanish, it is normally associated with a national or regional audience, while a predominance of articles in English allows it to be associated with a potentially wider audience (Brock-Utne 2007; Ishikawa 2014).

The efforts made by many non-English-speaking countries to publish their science in English is framed in this is context (Meneghini and Packer 2007). Therefore, language choice can be considered a privileged position to analyze the editorial tensions that occur in reference to (i) the ease or difficulty of the authors to communicate in a certain language and (ii) the local/global reach of a journal, anticipating the potential readership.

Our research is focused on approaching the problem of the Anglicization of science before the implementation of the science evaluation system based on publications. Hence, we will examine the first twelve years of Caldasia, a biological science journal that has been published from 1940 to the present.[3] During its publishing history, Caldasia has published articles in Spanish and English.[4] Though, the peak years of publishing in English were during its first and last 12 years with a 30 % share of all articles published in these two periods, this language has been present throughout the journal’s history and it can be assumed that the first publishing years had a lasting impact in Caldasia’s journey.

From 1940 to 1952, mutual conditioning factors between authors and editor regarding language are observed early on as to: language skills, editorial convenience and the establishing of the geographic scope of the journal. This article combines tools from bibliometrics and the history of science and scientific publishing to analyze the language of the articles published in Caldasia between 1940 and 1952, a period during which Armando Dugand Gnecco was the director of the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales (ICN) and the first director of the journal, which had significant participation by researchers from US institutions mainly interested in establishing contacts with the Colombian scientific community.

Caldasia demonstrated with its content signs of a multilingual process. Between 1940 and 1952, approximately half of the researchers who published in the journal were from US institutions and 31.7 % of the articles published in the journal were written in English. Caldasia existed as a multilingual journal. Hence, in the case of Caldasia, three questions are addressed: how was the use of Spanish and English in the journal approached by the journal’s editor and US researchers? How was it decided upon in this period? And finally, what does the case of Caldasia teach us about the role of multilingualism in the Anglicization process of scientific communication in the mid-20th century?

Given that currently in the scientific field it is understood that English equals international, other languages equal local/regional, the case of Caldasia is central to recognizing some of the specific mechanisms through which this conception was built. An analysis of the language used in Caldasia’s articles demonstrates that the editor and US researchers who contributed to Caldasia had different ways of considering the geographical scope of this publication, either as a regional journal or international journal. Therefore, the editor and the authors related the language differently to: (i) the journal’s geography of publication, (ii) the geography of the objects of study, (iii) and the journal’s potential readership (circulation) (see Figure 1).

Language as the focus of analysis for the geographical scope of a journal. Source: Author

US researchers largely believed that the most appropriate medium to publish their results was in Spanish, while the editor of the journal preferred that they publish in English and that Latin American authors publish in Spanish. Both parties expressed linguistic ideologies regarding the scope of Spanish and English in scientific communication processes.[5] Namely, these parties produced and constituted politics of location (physical and symbolic) towards groups of scientists according to the greater/lesser command of one of these languages.[6]

The different approaches with which the actors related these elements highlights the peculiarities of how the tension between multilingual repertoires and linguistic ideologies was experienced in Caldasia.

Multilingual repertoires include the languages, dialects, registers and styles that are available to speakers and which can be selected to make themselves understood verbally or in writing in linguistically diverse environments, regardless of the communication skill proficiency in one language or another. Their multilingual repertoire is made up of learning patterns and language encounters that these individuals have had. Therefore, the linguistic repertoire must be seen as a space for restrictions/potentialities in communication that is achieved situationally in communicative interactions with others (Blommaert and Backus 2013; Gumperz 1964; Lüdi 2006; Ros 2020).

Multilingualism in Caldasia was not the result of the convergence in its pages of two groups of monolingual researchers, one “Spanish-speaking” and the other “English-speaking.” On the contrary, the journal’s multilingualism was constituted from the convergence of authors with multilingual repertoires who saw their multilingualism restricted in this journal due to the editor’s initiatives.[7] Caldasia’s editor redirected the multilingual repertoires of the authors towards a language-state relationship in which US researchers were encouraged to write in the journal mainly as English-speaking researchers, while Colombian researchers did so mainly as Spanish-speaking researchers.

In the field of the history of science, important studies have been published on the dynamics of scientific encounters between Colombia and the United States during the first half of the 20th century.[8] These studies have moved from explanatory papers focused on dependency (center-periphery) towards more complex analyses in which the asymmetries that existed between the parties are recognized. However, the negotiated nature that drove these encounters as well as the mutual benefits that the parties achieved is still acknowledged.

Thus, in this study we wish to contribute by focusing on understanding that Caldasia became a contact zone. The category of contact zone refers to an area in which interacting groups speak different languages, highlighting the asymmetries between the groups that are in contact but still considering that these asymmetries may be suspended or modified in favor of local needs and wishes of the groups in the least advantageous position in the encounter (Pratt 1991, 2003; Roberts 2009). Hence, Caldasia is understood to be a publishing space where intense and asymmetric encounters played out between United States and Colombian researchers, ones in which language was the driver of negotiations that occurred among the parties and the editor played an active role in the negotiations.

Caldasia’s multilingual language regimen, which emerged in this period, was the engine and expression of the configuration of a politics of location with a linguistic ideology according to which English should be understood as the international language of science while Spanish should be conceived as a local/regional language. The Caldasia case demonstrates that the Anglicization process of science in the twentieth century required intense scientific contacts carried out in non-English-speaking spaces with multilingualism being a part of this development.

2 Methodology

The language analysis of the articles in Caldasia was carried out with (i) bibliometrics and (ii) document analysis. In bibliometric terms, indications of the language choice were captured by reviewing the contents of all research papers published in Caldasia (N = 180) between 1940 and 1952. This is how the share of the two languages in the articles was determined. The information was processed with the Pajek, a software program used for the analysis and representation of social networks. In our case, it facilitated the analysis of the existing links between the language of the published articles and the authors’ country of affiliation.[9]

(ii) For the documentary analysis, the Historical Archive of the Instituto de Ciencias Naturales (AICN) located at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in the city of Bogotá (Colombia) was consulted. An interval of Caldasia’s communication circuit was analyzed, specifically, correspondence between the director of the journal and US researchers interested in having their work published and in which the language aspect of the articles was the focus of discussion.

Although there is a high number of communications in the archive between the editor and the authors affiliated with institutions in Latin America, these communications focus on formal aspects of publishing the articles in the journal and not on the issue of language choice. Thus, this correspondence will not be analyzed. Although, this fact will be taken as an indication that supports what we will later call as the editorial flexibility in Caldasia as to language.

3 Caldasia in the 1940s

The 1940s was an important period in the evolution of journal publishing in both Latin America and Colombia; In 1949, approximately 1,200 scientific publications were produced in Latin America (Shapley 1949). A significant number of these journals specialized in biological sciences and have continued to date, e.g., Rodriguesia has been published in Brazil by the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro since 1935; Lilloa has been printed in Argentina by the Miguel Lillo Foundation since 1938; and Caldasia has been published in Colombia by the ICN since 1940.[10]

Colombia, during the period called the Liberal Republic from 1930 to 1940, went through an unprecedented cultural experience characterized by nationalist attitudes that broadened the notion of the country’s culture (Silva 2005). This drive legitimized the creation and financing of institutions exclusively dedicated to developing knowledge on the flora and fauna in the national territory. It is in this spirit that the creation and mission of the ICN of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and its publication Caldasia can be understood (Quintero 2014).

On December 20, 1940, ICN published the first issue of Caldasia that stood out from previous journals published in the country because it included three characteristics: (i) publication of researchers’ work in the format of a journal article; (ii) reception and publication of articles from a single field of knowledge; and (iii) focus as a journal primarily for a specialized audience.[11] Therefore, the efforts to produce Caldasia must be seen as those of a nascent scientific community interested in conquering a relatively autonomous space for its activity in Colombian society. This effort yielded results given that Caldasia managed to function as a node in a network that linked various players and institutions in and outside of Colombia around a research agenda focused on knowledge of Colombian flora and fauna (Hernández-Socha 2018).

When it began, ICN did not have a scientific infrastructure robust enough to study the Colombian flora and fauna.[12] Therefore, contact with US researchers and institutions was fundamental to provide ICN with the necessary knowledge and information to conduct scientific research, consolidate a scientific community in the country, reach a certain level of prestige in Colombia and begin to be acknowledged before the international scientific community (Quintero 2012).

Parallel to this, the United States consolidated itself as a global power and a point of reference in the Latin American region. The United States viewed Latin America as a key trading partner. On the one hand, Latin America was seen as a valuable source of raw materials and, on the other, as a potential consumer of manufactured and industrial goods that were produced in the United States (Quintero 2009).

However, the emergence of the United States as a new power in the region was not limited exclusively to the economic and political spheres, science also played a preponderant role in this process.

At this time, the United States increased its efforts to establish scientific cooperation agreements with the Latin American region to establish relations based on understanding and non-intervention.[13] In 1940, as Nazi Germany seized territories in Europe, the United States government tried to secure the loyalty and assistance of Latin America in the coming war (Sadlier 2012). Specialized journals and nature studies played a central role in this process.

For the United States promoting scientific exchanges with Latin America through journals became important. The creation of the Committee on Inter-American Scientific Publication (CIASP) was an initiative in this direction, especially its commitment to encouraging and facilitating translation from Spanish to English of articles by Latin American researchers to be published in United States journals. The circulation of knowledge in journals would contribute to strengthening alliances between the nations of America, which in the context of World War II was considered a strategic matter (Minor 2016).

Nature studies were a central tool in promoting Pan-American cooperation and integration. In the case of scientific cooperation between the United States and Colombia, the interaction between United States and Colombian naturalists made it possible to consolidate shared research agendas and conservation policies. In United States scientific institutions, the need to establish and strengthen direct contacts with Colombian naturalists was promoted, insofar as the latter were essential to complement research on rare Colombian specimens and to have an allied voice within the Colombian government to support nature conservation initiatives promoted by US researchers (Quintero 2012: 167).

From 1840 to 1950, the practice of survey collecting was the predominant collection practice in biological sciences in the United States. It was the systematic, extensive and intensive collecting of specimens. This practice was active on two fronts, one national and the other global: (i) on the national front, survey collecting took place within the United States and neighboring countries in North America and was promoted by governments and nation states; (ii) on the global front, this took place in territories other than North America (e.g., in South American countries) and was supported mainly by museums and science academies of the United States (Kohler 2006: 9).

It is precisely within the framework of the global front where scientific relations in the biological sciences between the United States and Colombia were established in the first half of the 20th century. The ICN was a benchmark institution for joint work with American scientific institutions, and Caldasia was a place, among others, where these scientific exchanges occurred (Hernández-Socha 2020).

4 The main languages in Caldasia

From 1940 to 1952, a significant editorial process transpired at Caldasia: 26 issues were published with an approximate periodicity of 2.16 issues per year, and 43 researchers published 180 papers on various topics: botany (55 %), ornithology (21.1 %), entomology (9.4 %), herpetology (8.9 %), ichthyology (2.2 %), ethnobotany (1.1 %), mycology (1.1 %), parasitology (0.6 %), and geology (0.6 %).

During this period, Caldasia became a non-commercial journal with a significant circulation capacity both in the national and international scientific fields. On average, 496 copies were published for each issue of the journal and its geographical distribution was concentrated in at least three continents (see Table 1), but with strong circulation in the American continent, specifically in countries such as Colombia (43.6 %) and the United States (25.5 %).

Caldasia circulation by continents, 1940–1952.

| Copies | % | |

|---|---|---|

| North & Central America | 1263 | 32.4 |

| South America | 2391 | 61.4 |

| Europe | 237 | 6.1 |

| Asia | 5 | 0.1 |

| Total | 3896 | 100 |

-

Source: Author.

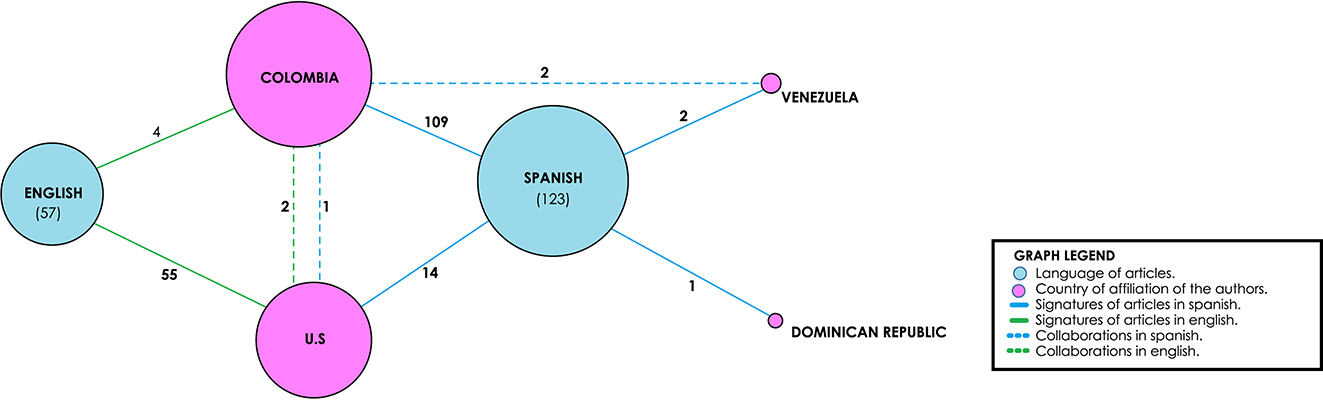

When we concentrate on the language of the articles published in the journal, Figure 2 shows that the most used languages were Spanish and English. Although the data indicates that Spanish was the predominant language for the articles published in Caldasia, the considerable use of English in the pages of the journal should not go unnoticed, especially from 1944 to 1952.[14]

Share of language in Caldasia’s articles, 1940–1952. Source: Author.

Furthermore, the fact that during these years no other language was used is a clear indication that Caldasia was a publication in which principally researchers with these language skills contributed. Table 2 shows the preponderance of Colombia and the United States as the main countries for the institutional affiliation of the authors in Caldasia.

Country of institutional affiliation for the authors in Caldasia, 1940–1952.

| Country | Authors | % |

|---|---|---|

| Colombia | 21 | 48.8 % |

| United States | 20 | 46.5 % |

| Dominican Republic | 1 | 2.3 % |

| Venezuela | 1 | 2.3 % |

| Total | 43 | 100.0 % |

-

Source: Author.

When linking the language of Caldasia’s articles to the authors’ country of institutional affiliation, there is an important correlation between both variables. Figure 3 shows that the authors affiliated to institutions in Colombia wrote the articles mainly in Spanish and to a lesser extent in English, while researchers from institutions in the United States wrote their articles mainly in English and to a lesser extent in Spanish.

Relation between country of authors’ institutional affiliation and the language of the articles in Caldasia, 1940–1952. Source: Author.

Although, these last records apparently show that Latin American and American researchers mainly chose to publish articles in the language most convenient for them, these records obscure that for researchers affiliated with US institutions the selection of the language was quite conflictive. As we shall see, US authors had a multilingual repertoire that they wanted to make available to the journal, since they believed that the subscribers of a journal published in Colombia only read in the Spanish language (language-state relationship); according to this linguistic ideology, Spanish would be the appropriate language to publish their research in Caldasia.

5 Tensions in setting Caldasia’s geographical scope: an international journal versus a regional one

In the process of determining the most suitable language for publishing articles in Caldasia, the difference in the way that the editor and US researchers conceived the geographical scope of the journal became clear. For the editor, Caldasia was a journal with an international scope, while for the US researchers, it was a regional journal. It is in this light that the editor’s inclination for US researchers to publish their articles in English should be understood versus that of researchers who considered that their contributions should be published in Spanish.

This difference in the two parties’ conception of Caldasia’s reach played out intensely in the first five years of the journal’s existence. Therefore, this difference can be considered an expression of the process of editorial standardization for the journal in its first years. In the specific case of language, this implies the process of standardizing the languages in which the researchers would publish in the journal.

In this regard, two recurring editorial procedures stand out and they were used by the editor and US researchers to try to decide on the most appropriate language to publish the articles in Caldasia: (i) determine in advance the potential audience of the journal and its language skills and (ii) support the editorial advantage of publishing in either of the two languages.

To understand this editorial approach and its editorial procedures, we will analyze some significant communications between Armando Dugand, editor of the journal, and US authors interested in publishing in the journal, such as: Louis O. Williams, Richard Clements, Robert E. Woodson Jr., F. J. Hermann and Alexander Wetmore.

Armando Dugand (1906–1971) was a Colombian geobotanical botanist and ornithologist. Author of 127 publications, he has been considered one of the most important figures in Colombia in the field of botany. Dugand was born and grew up in the elite Colombian social circles that had contacts in the United States, and they saw this country as a model for development in Colombia. In his education as well as his professional development, the United States had a constant presence: Research Fellow of Harvard University, attached to the “Arnold Arboretum” and the “Gray Herbarium” in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1942, and member of the “John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation” from New York between 1965 and 1967. It is also important to note that between 1940 and 1952, Dugand was both the director of Caldasia and ICN, thus, it may be assumed that his position on the orientation of Caldasia had institutional backing afforded by his position as director of the institute.

On March 2, 1942, Louis O. Williams (1908–1971),[15] a researcher from the Botanical Museum of Harvard University, queried Armando Dugand about whether it was appropriate or not to publish an article in Spanish that he was writing on orchids located mainly in America:

A few days ago I had a letter from Dr. Schultes in which he told me that he thought that you would like to have another short paper on orchids for the next number of CALDASIA.

I have gone through a pile of my manuscript notes and have taken out all of those pertaining to South America, the West Indies and a couple of those for Central America […] Will you be kind enough to correct and publish the Spanish if you decide to use the article. I believe that I would just as soon have articles Published in South America in Spanish, especially when the plants concerned are almost all from Spanish speaking countries.[16]

In this letter, Williams established associations between the use of Spanish as an appropriate language to present his article and the geographic conditions. Williams considered it totally pertinent to present his article in Spanish since it would be published in a journal such as Caldasia, i.e., a journal located in a Spanish-speaking country of South America. In addition, for Williams the relevance of Spanish was reinforced by the fact that the objects of study in his paper were also located in Spanish-speaking countries.[17] Given these associations, the researcher considered that the article would surely be of great interest to the scientific community in these territories, a Spanish-speaking public.

Williams perceived Caldasia as a regional journal and actually tried to establish the existence of a “geographical coherence”, established by a link among the geography of the objects of his study (South America countries), geography of the journal (a South American country where Spanish is spoken), the journal’s potential audience (Spanish-speaking people with little or no command of English) and the language in which the research results were to be presented (Spanish).

The appropriate language for the publishing situation in Caldasia was established by imagining the linguistic knowledge/lack of knowledge of the rest of the scientists who participated in the linguistic exchange (Salö 2022). With the idea of publishing in Spanish, Williams makes a repair, which in multilingual exchanges is expressed through the changes made by the speaker to reach a compatible code of communication with his interlocutors (Blommaert et al. 2005: 212). For US researchers, this repair mainly originates from a linguistic ideology, which expresses and at the same time generates limits of spatial location of the “other”, the scientific community that is around Caldasia; this spatial location includes both a physical aspect, people located in South American countries, and a symbolic one, Spanish-speaking readers with little or no command of English.

Moreover, Williams sees himself as a researcher with a multilingual writing repertoire and wishes to publish in Spanish, although he recognizes that his writing competence in Spanish requires the accompaniment of the editor in the manner of a literacy broker.[18] He considers that this multilingual repertoire is vital to establish “geographical coherence.”

However, Armando Dugand had another conception of the geographic scope of the journal. Hence, it is appropriate to examine the reply to Richard Clements, affiliated to the Colombian-British Cultural Institute, who like Williams, also expressed his doubts to Dugand regarding the most appropriate language to publish an article in Caldasia. Dugand preferred that the latter present his contribution in English:

We publish articles in English as well as in Spanish in our bulletin CALDASIA. You may feel free of writing yours in either language. Personally, I should prefer it in English as our bulletin reaches many English-speaking centers and one of its aims is to make Colombia known abroad.[19]

For Armando Dugand, Caldasia was a journal with a regional and international scope since its readership was not only from Colombian or South American institutions. The journal was also of interest to researchers affiliated to international research centers where, as claimed by Dugnad, English was the main language.

For Dugand, Caldasia’s public was not uniform in its language abilities with Latin American readers that had good command of English and Spanish, while the non-Latin American readers had good English abilities but limited ability for Spanish. This forecast of the potential audience was a determining factor in Dugand’s judgment that English could be an appropriate language to assure effective communication of the journal contents to this public in particular. English could be an appropriate language to publish articles in the journal.

Dugand referred to Caldasia’s readers as a public that understood both English and Spanish. However, Dugand assessed that he preferred that the article be published in English and stated that publishing articles in English about such local and regional biodiversity would contribute to calling the attention of researchers in other countries. Let us remember that establishing scientific collaborations with North American researchers was essential for the ICN. These collaborations allowed access to scientific infrastructure and made it possible for the ICN to gain scientific legitimacy both nationally and before the international scientific community.

Dugand promoted a linguistic ideology that energized a politics of location in which physical and symbolic spaces are also interrelated. He contributed to establishing a linguistic market in which English would be the language of “international” scope while Spanish would have a “local/regional” limited scope.[20]

The undertone of the correspondence reveals that both Williams and Dugand’s vision share a common point; the journal is not conceived as an abstract tool, driven by a logic of publishing for publishing’s sake. On the contrary, both parties conceive the journal as a communication tool linked to specific scientific communities. Consequently, language is understood as a central element to try to ensure effective communication with the journal’s audience.[21]

In the analyzed correspondence, it is observed that the language-subject-readers configuration is mediated by the editorial process known in the literature on the history of the book and publishing as “anticipation of demand”. The history of science and scientific publishing shows that the potential readers of a scientific work have an effect on a work’s communication circuit, i.e., potential readers are a core element that is present in editors’ and authors strategies during the materialization process of works (Fyfe 2002).

In the correspondence, it is evident that scientific astuteness mediated the publishing experience and editorial astuteness mediated the scientific experience. In line with the potential readers of the journal, the articles were printed in a specific language.

5.1 Select the languages in Caldasia based on editorial convenience

The editorial insight was not the only publishing practice that energized the selection of one language or another. As we will see in Dugand’s reply to Robert E. Woodson Jr.’s request, it is evident that “editorial convenience” was another factor.

Robert E. Woodson Jr. (1904–1963), a botanist affiliated to the Missouri Botanical Garden,[22] consulted Dugand about the possibility of publishing in Caldasia his work on South American Genolobeae of Asclepiadaceae and asked Dugand about the most appropriate language to publish his paper in the journal.[23] In his letter, Woodson Jr. also established a “geographical coherence” conceiving Caldasia as a Spanish journal.

Similar to his reply to Williams, Armando Dugand told Woodson Jr. that the most appropriate decision was to publish his results in English, yet this time his answer was not justified by the degree of internationality of Caldasia’s reading public, but by editorial convenience. Dugand explained his position on publishing the article in English or Spanish:

I acknowledge receipt of your letter of September 24 and I wish to assure you that I do appreciate very highly your proposed collaboration in “Caldasia” […]

Papers in English – as you already know – are being published in our bulletin, by North American botanists and zoologists who do not have a fluent command of the Spanish language. To be frank, we in Colombia have a rather very high and justified concept for the kind of Spanish we speak and write, and especially our Universities and Academies, and other centers of learning, are extremely keen and critical about it. Now, unless an English-speaking author has a really good knowledge of Spanish terms and syntaxis, and he can write his manuscripts, or have them translated and written by a competent Spanish-speaking person, in such a way that does not need a lot of corrections and re-writing here, it is very much easier both for him and for the editor, to write them in English.[24]

Dugand pointed out that those who published articles in English in Caldasia were mainly US authors who did not have a good command of written Spanish. If the authors published in Spanish without having adequate proficiency, the editor would face an excessively complex and lengthy revision processes. Dugand also mobilized the myth that Colombian Spanish is one of the purest to discourage US authors away from using Spanish.[25] In Dugand’s mindset, one of his roles as editor was to safeguard “high standard” language use.[26] Another strategic argument to reinforce the editorial convenience.

In his response, the editor also distances himself from the role of literacy broker. It is important to note that this editorial decision of opting to publish articles in English had economic repercussions. According to the agreement established between ICN and the printer, El Gráfico, Caldasia’s printing cost increased if the pages were published in a language other than Spanish. For this reason, the editor’s decision suggests that the increase in the printing price was offset by the time saved in editing. Although the perception of Caldasia as a journal of regional and international scope is not explicitly present in this letter, the editorial convenience along with the printing costs that are incurred by this decision make sense within the framework of considering Caldasia as a journal aimed at an English-speaking audience. Dugand was willing to pay the price of giving an international scope to his journal. In this editorial position, again, a linguistic ideology is expressed in which English is equivalent to international.

This preference for editorial convenience allows us to frame the dynamics at Caldasia within the tension between a multilingual repertoire and the establishing of Caldasia as a multilingual journal. But these categories themselves had a completely different meaning depending on the party’s ideology. For US authors, English was not an understandable language for the scientific community they envisioned for Caldasia. Choosing to write in the language they were fluent in (speaker-centric) implied a greater connection with an English-speaking reader but made it impossible to communicate with the public they associated with Caldasia, a Spanish-speaking public. On the contrary, for the editor of the journal writing in English implied a suitable mix of the US authors’ ease of writing and the communication aspirations of the journal, since Dugand defined Caldasia’s potential readers as a Spanish and English-speaking public.

The editorial desirability expressed by Dugand attempts to discourage multilingual writing repertoires expressed by US authors, specifically, their intention to publish in Spanish. In the correspondence, it is evident that the journal’s multilingualism emerges from reorienting the multilingual writing repertoire of US researchers.

The combination of anticipating the language skills of the journal’s potential public and the editorial convenience that arose from writing in a familiar language were explicitly referenced in the communication between Armando Dugand and F.J. Hermann (1906–1987) a botanist from the United States Department of Agriculture.[27] Dugand suggested that Hermann publish an article in Caldasia on the Colombian botanical collection under his charge. In this regard, Hermann wrote:

Thank you for your cordial letter of September 1st, and for your offer to publish a paper on my Colombian collections in Caldasia. I suppose that such a paper would be more generally useful if it were in Spanish, but if I undertake to write it in that still too-little familiar language I must beg you as a favor to rectify at least the really gross solecisms during your editing or the manuscript.[28]

For Hermann, publishing an article in Caldasia that dealt with a Colombian botanical collection meant that it would be published in Spanish, manifesting a geographic coherence; furthermore, the author expressed the difficulties involved in writing his article in an unfamiliar language and, Caldasia’s editor was the right person to provide support for the translation.

In his reply to this letter, Armando Dugand pointed out to Hermann that publishing articles in a language that the author mastered represented an editorial convenience for both parties: author and editor. Sending the article in English would generate less effort in the document’s writing and editing process. Furthermore, he added that publishing in English was not an inconvenience for the journal’s public since Caldasia was not a journal exclusively for Spanish readers, and according to the editor, most botanists from Latin America understood English:

It would be much preferable, I believe, to write your manuscript in English, especially if you are not yet familiar with the subtleties of the Spanish language. Caldasia is not only a magazine for Spanish readers, and most of the Spanish and Spanish-American botanists understand English. Besides, for simple reasons of time, I avoid as much as possible re-editing the manuscripts. I would therefore recommend that your manuscript be written “ready for the printers.”[29]

For US authors, the proposed language choice led to establishing links with a regional community (imagined as a Spanish-speaking scientific community) at the cost of losing communication with the English-speaking scientific community, at least in reference to the articles that would be published in Spanish.

However, the editor considered that publishing in Caldasia would not necessarily imply losing internationality due to the language used. For Dugand, both aspects were compatible in Caldasia: (i) the journal had circulation throughout scientific institutions around the world, which were mainly institutions located in English-speaking countries; (ii) Caldasia readers in Latin America were fluent in English.

The aforementioned points are crucial for understanding that at the time Caldasia was a publication in the process of standardization. Precisely, the journal was constituting an idiomatic publishing regimen in which English plays a central role as the language of science. To that extent, the participants became more aware of the expectations of the journal.

According to the reviewed documentation, as of 1945 there are indications that the standardization process at Caldasia took a specific direction; the journal began to be viewed by US researchers as a multilingual journal, i.e., with a potential readership that was fluent in Spanish and English. Indicators of this trend were: (i) the decrease in correspondence between the editor and US researchers in which the most appropriate language to publish in the journal was discussed; (ii) correspondence in which researchers from US institutions began to acknowledge Caldasia as a means to publish their research results in English.

An example of the latter is observed in a consultation by Alexander Wetmore (1886–1978), affiliated to the Smithsonian Institution,[30] in which he indicates the reasons why he decided to “venture” to send his contribution to Caldasia in English:

I am taking advantage of Mr. Killio’s journey to Colombia to place in your hands this manuscript on the classification of the Rayadores that I would like to offer for publication in “Caldasia,” if it is not too long. I had in mind originally to translate this into Spanish before asking you if you would like to print it. I have been so occupied, however, with other matters that there has not been time to allow this. I have noticed in recent numbers of your magazine short articles in English and so venture to offer this one.[31]

Although it was a viable option for Wetmore to translate his contribution into Spanish, he expressed a definite preference to avoid this translation and present his article directly in English, and since the journal had published other articles in English, he felt there was support for this choice. In this regard, Armando Dugand did not express any objection, and thanked him for the sending the article.[32] US researchers began to recognize the language choices that the journal offered.

Finally, it is important to mention that the editorial convenience declared by the editor of Caldasia at certain times demonstrated editorial flexibility as to the most appropriate language to publish in the journal. We should not ignore that the aggregate records showed that: (i) 14 articles published in the journal in Spanish were authored by US researchers;[33] (ii) the vast majority of articles published by Colombian and Latina American researchers were published in Spanish, including papers by Armando Dugand; (iii) in the journal correspondence, no pressure was observed for Colombian and Latina American researchers to publish their articles in English. Dugand did not try to redirect these authors’ repertories. We can affirm that for Dugand, Caldasia had to become a space for multilingual scientific exchange. Dugand made the most of the authors’ linguistic repertoires and the ICN network to strengthen US-Colombian academic collaboration.

6 Discussion and conclusions

Between 1930 and 1949, the United States advocated scientific diplomacy that made it possible to establish ties of scientific cooperation with Latin American countries. This diplomacy fulfilled two objectives (i) to integrate the United States with the Latin American region under the principles of understanding and non-intervention and (ii) to displace European influence and consolidate North America as a scientific reference for the region.

Even though language differences have been present in these scientific engagements, the problems related to linguistic tensions in scientific communication have not been addressed in depth. This is striking since along with the aforementioned language differences, it was during the 20th century especially starting in the 1940s, that science underwent a process of Anglicization, notably promoted in the contents of journals focused on disseminating discoveries about the natural world (Gordin 2015: 295, 299).

Despite being published and printed in Colombia, Caldasia was not a purely national communication circuit. In the 1940s, Caldasia became a contact zone, the expansionism of United States science and the national research agendas of the Colombian scientific community specialized in biological sciences converged. Journals such as Caldasia helped build mutual recognition between United States science and Latin American science. It implied that researchers and editors in the region had to increasingly recognize the importance of thinking about the scope and limitations of Spanish and English in the process of scientific communication. The various linguistic ideologies expressed by the actors regarding the scope and limitations of Spanish and English are expressions of this importance.

The American researchers wanted to strengthen their relationships with Colombian scientists and those from the Latin American region to consolidate their research agendas in Colombia (Quintero 2012). In this regard, our study showed that the practice of publishing in journals such as Caldasia could be understood within the framework of the expansionism of American science. Researchers affiliated with US institutions were motivated to publish in Caldasia mainly with the intention of establishing direct communication with scientific communities in the Latin American region.

In turn, Colombian researchers wanted to acquire national legitimacy and international recognition for their scientific agendas. On this point, the connection with American researchers was a valuable opportunity to fulfill this objective. Our study showed that Armando Dugand saw in this encounter an opportunity to strengthen scientific collaboration relations with North America, position research agendas (the study of Colombian territory) and the media (such as Caldasia) within a communication framework that went beyond the reach and form of a non-English publication.

Hence, when trying to anticipate the potential readership of the journal, US researchers chose Spanish as the most relevant language to publish their articles in the journal. These researchers inferred and actually tried to establish the existence of a “geographical coherence”, driven by a linguistic ideology in which publishing in Spanish corresponded to a logic in which gaining communication at a regional level meant communication at an international level would be lost.[34]

However, Dugand tried to break with this “geographical coherence” by proposing another type of geographic scope for Caldasia. For the editor, the interest of US researchers to publish in Caldasia was seen as an editorial opportunity for Caldasia to go through an internationalization process by prompting these researchers to publish their work in the journal in English even if this meant higher printing costs. In this framework, it is understood that the publisher sought to ensure that multilingual US researchers be primarily perceived as English-speaking researchers in Caldasia. As Blommaert (2005) has expressed it, multilingualism is not simply the manifestation of an individual’s ability to deal with particular languages, but rather the product of the situational environment in which certain linguistic assets are enabled or disabled.

The promoters of the journal chose to make Caldasia a multilingual journal, a regional/international forum and English played a central role in defining the geographic scope of Caldasia. Hence, the linguistic regimen that is built in Caldasia is an expression and engine of the process of Anglicization of science that is taking shape in this period, i.e., the idea that “international” and “English” are synonymous.

Therefore, the Anglicization process that Caldasia underwent between 1940 and 1952 was not purposely promoted by US researchers. To the contrary, it was an Anglicization by invitation brought about by the journal’s editor who played a leading role in this transition. This invitation enabled Colombian researchers to establish and strengthen scientific collaboration ties with the United States.

In the background, the Anglicization by invitation expresses the usual logic of consolidating a hierarchical linguistic market. Linguistically subordinated groups legitimize the benefits of the difference that subordinates them (Bourdieu 1991). In this case, they support the advantages and greater value of English versus the limitations of Spanish, leading to the naturalization of the arbitrary positioning of English as the international language of science. As Makoy and McKinney have put it, “consensus on the legitimate language depends on both those who benefit from the ideology as well as those disadvantaged by it” (2014: 660).

Hence, it can be stated that the inter-American integration process made it possible to increase the influence of English in the region. The editorial dynamics of Caldasia were part of this process. The multilingualism of Caldasia can be understood as one of the strategies by which English became a globally accepted language.

What does the case of Caldasia teach us about the role of multilingualism in the Anglicization process of scientific communication in the mid-20th century? This case study leads to two lessons about the formation process of a monolingual science: (i) it is necessary to overcome a unidirectional vision of the Anglicization process of science, i.e., a vision according to which this process occurs only because non-English-speaking researchers are attracted to English spaces of communication.

The process of bringing about a monolingual communication system can be analyzed with greater complexity if we link it to the expansionism of United States science carried out on a global level. Precisely, the case of Caldasia reminds us that the expansionism of US science required intense scientific contacts that were also carried out in non-English-speaking spaces. The US researchers’ efforts were focused on publishing in a non-English-speaking space as they conceived Caldasia: an ideal journal to approach potential Spanish-speaking “regional” audiences. Precisely the willingness of US researchers to publish in this space and even negotiate the language in which the results of their research would be published is the engine and expression of this process.

Therefore, the Caldasia experience invites us to break with what Solli and Odemark (2019) have defined as an English-centric conceptualization of multilingualism. This interpretation gives very little or no attention to the situations in which researchers live and work in contexts where English is the official and dominant medium of communication, but their work is written for publication in countries where other languages predominate, as in the experience of the US researchers in Caldasia.

Did multilingual spaces emerge and multiply during the consolidation of monolingual English-speaking space?

(ii) Although the case of Caldasia relates to Colombia and the biological sciences in particular, we consider that it should be understood as part of a global process, i.e., one that occurred with particularities in various regions other than Latin American e.g., Africa, Asia and Europe.[35]

In the case of Caldasia, United States expansionism was expressed through the consolidation of a multilingual space. However, this situation did not necessarily mean the emergence and consolidation of symmetrical relationships between English-speaking researchers and Spanish-speaking researchers. In fact, this multilingual space made it possible to address asymmetric relationships. These asymmetries were a constitutive part of the contact zone represented by Caldasia. Dugand’s recognition of the potentialities of English and not of Spanish to internationalize Caldasia is an expression of this. As Duchêne (2020) has warned, multilingualism can also generate inequalities. Multilingualism can have different meanings in different places or circumstances, it can reflect different phases of the “struggle for access to and distribution of knowledge, resources, and status” (2020: 93).

Therefore, we have some insights that allow us to think that asymmetric relationships were manifested from an unequal geographical distribution of multilingual and monolingual spaces. Thus, in Colombia, a multilingual space like Caldasia emerged in which English and Spanish converged. On the other hand, in the United States, an organization such as CIASP sought scientific integration between North and South America by encouraging Latin American researchers to publish in journals edited in the United States. However, Latin American researchers were required to publish their articles in English.

In the 1940s, Caldasia and CIASP took different paths in the Interamerican scientific integration (multilingualism/monolingualism), but both led to an increase in the importance of English in the region and these editorial practices helped to configure the current politics of location. This is a politic that as Lillis and Curry (2010) pointed out has brought about the label of “international” knowledge to mean Anglo-speaking centers, while “local” refers to knowledge produced outside of Anglo-speaking centers. Then, “international” and “good English” began to be used as synonyms for high quality scientific publications.

Now with greater frequency but not exclusively, the interactions between authors, reviewers, and editors occur in an environment where researchers that have been labeled as “local” face considerable obstacles to publish in a higher scale with more “international” prestige (Broekhoff 2019; Hanauer et al. 2019; Lillis and Curry 2010; McDowell and Liardét 2019; Melliti 2019; Nygaard 2019; Stockemer and Wigginton 2019; Strauss 2019). Given the above, we consider that reflections on these publication regimens should also explore to what measure the current editorial multilingualism policies implemented in certain journals,[36] help to overcome or consolidate the ideology of scientific monolingualism.

Acknowledgments

I thank Professor Jorge Márquez for his support and guidance throughout the research, Leonardo Álvarez for providing language help, Omaira Londoño for her collaboration with the archival work, and Liliana Delgado for providing writing assistance. I also thank the funding for publishing this research by Dirección General de Investigaciones of Universidad Santiago de Cali under call No. 02-2023. And finally, the editor and the referees’ comments, which are greatly appreciated and led to an improved version of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of Interest statement: I have no conflict of interest.

References

Bennett, Karen. 2014. Introduction: The political and economic infrastructure of academic practice: The semiperiphery as a category for social and linguistic analysis. In Karen Bennett (ed.), The Semiperiphery of Academic Writing: Discourse, Communities and Practices, 1–9. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137351197_1Search in Google Scholar

Blackledge, Adrian & Aneta Pavlenko. 2002. Introduction. Multilingua 21. 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.2002.006.Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan, Collins James & Stef Slembrouck. 2005. Spaces of multilingualism. Language & Communication 25. 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2005.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan. 2006. Language ideology. In Keith Brown (ed.), Encyclopedia of language and linguistics, 6, 510–523. Oxford: Elsevier.10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/03029-7Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan & Ad Backus. 2013. Superdiverse repertoires and the individual. In Ingrid Saint-Georges & Jean Weber (eds.), Multimodality and multilingualism: Current challenges for educational studies, 11–32. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.10.1007/978-94-6209-266-2_2Search in Google Scholar

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and symbolic power. Cambridge: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Brock-Utne, Birgit. 2007. Language of instruction and research in higher education in Europe: Highlights from the current debate in Norway and Sweden. Imernational Review of Education 53. 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-007-9051-2.Search in Google Scholar

Broekhoff, Marna. 2019. Perceived challenges to Anglophone publication at three universities in Chile. Publications 7. 61.10.3390/publications7040061Search in Google Scholar

Curry, Mary & Theresa Lillis. 2017. Problematizing English as the privileged language of global academic publishing. In Mary Curry & Theresa Lillis (eds.), Global Academic Publishing: Policies, Perspectives and Pedagogies, 1–20. Bristol and Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783099245-006Search in Google Scholar

Deas, Malcolm. 2006. Del poder y la gramática y otros ensayos sobre historia, política y literatura colombianas. Bogotá: Taurus.Search in Google Scholar

Duchêne, Alexandre. 2020. Multilingualism: An insufficient answer to sociolinguistic inequalities. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 263. 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl-2020-2087.Search in Google Scholar

Fyfe, Aileen. 2002. Publishing and the classics: Paley´s Natural theology and the nineteenth century scientific canon. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 33(4). 729–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-3681(02)00032-8.Search in Google Scholar

Garfield, Seth. 2004. A nationalist environment: Indians, nature, and the construction of the Xingu national park in Brazil. Luso-Brazilian Review 41(1). 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1353/lbr.2004.0008.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbs, Wayt. 1995. Lost science in the third world. Scientific American 273(2). 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0895-92.Search in Google Scholar

Gordin, Michael. 2015. Scientific babel: How science was done before and after global English. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226000329.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Gumperz, John. 1964. Linguistic and social interaction in two communities. American Anthropologist 66(6). 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1964.66.suppl_3.02a00100.Search in Google Scholar

Haller, Max. 2019. A global scientific community? Universalism versus national Parochialism in patterns of international communication in sociology. International Journal of Sociology 49(5–6). 342–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2019.1681863.Search in Google Scholar

Hanafi, Sari. 2011. University systems in the Arab East: Publish globally and perish locally vs publish locally and perish globally. Current Sociology 59(3). 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392111400782.Search in Google Scholar

Hanauer, David, Cheryl Sheridan & Karen Englander. 2019. Linguistic injustice in the writing of research articles in English as a second language: Data from Taiwanese and Mexican researchers. Written Communication 36(1). 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088318804821.Search in Google Scholar

Harbord, John. 2017. Language policy and the disengagement of the international academic elite. In Mary Curry & Theresa Lillis (eds.), Global Academic Publishing: Policies, Perspectives and Pedagogies, 88–102. Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781783099245-011Search in Google Scholar

Hernández-Socha, Yuirubán. 2018. Un suceso Editorial en el Campo de las Publicaciones Especializadas de Biología en Colombia. Una Aproximación Histórica al Circuito de la Comunicación de Caldasia, 1940–1966. PhD thesis. Medellín: ColombiaSearch in Google Scholar

Hernández-Socha, Yuirubán. 2020. Scientific encounters between Colombia and the United States analyzed through publishing practices in Caldasia journal: The birds of the Republic of Colombia as a publishing event. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 82. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2020.101289.Search in Google Scholar

Horta, Regina. 2006. Pássaros e cientistas no Brasil: Em busca de proteção, 1894–1938. Latin American Research Reveiew 41(1). 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2006.0006.Search in Google Scholar

Ishikawa, Mayumi. 2014. Ranking regime and the future of vernacular scholarship. Education Policy Analysis Archives 22(31). 1–23. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22n30.2014.Search in Google Scholar

Kohler, Robert. 2006. All creatures. Naturalists, collectors, and biodiversity, 1850–1950. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Lillis, Theresa & Mary Curry. 2006. Professional academic writing by multilingual scholars: Interactions with literacy brokers in the production of English-medium texts. Written Communication 23. 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088305283754.Search in Google Scholar

Lillis, Theresa & Mary Curry. 2010. Academic writing in a global context: The politics and practices of publishing in English. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Lüdi, Georges. 2006. Multilingual repertoires and the consequences for linguistic theory. In Kristin Bührig & Thije Jan (eds.), Beyond Misunderstanding. Linguistic analyses of intercultural communication, 11–42. Amsterdam/Philadelpua: John Bensamins Publishing Company.10.1075/pbns.144.03ludSearch in Google Scholar

Mair, Christian. 2003. The politics of English as a world language. New horizons in postcolonial cultural studies. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi.10.1163/9789401200929Search in Google Scholar

Makoe, Pinky & Carolyn McKinney. 2014. Linguistic ideologies in multilingual South African suburban schools. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 35(7). 658–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2014.908889.Search in Google Scholar

Martín, Pedro, Jesus Rey-Rocha, Sally Burgess & Ana Moreno. 2014. Publishing research in English-language journals: Attitudes, strategies and difficulties of multilingual scholars of medicine. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 16. 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2014.08.001.Search in Google Scholar

Mazenod, Anna. 2018. Lost in translation? Comparative education research and the production of academic knowledge. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 48(2). 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2017.1297696.Search in Google Scholar

McDowell, Leigh & Cassi Liardét. 2019. Japanese materials scientists’ experiences with English for research publication purposes. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 37. 141–153.10.1016/j.jeap.2018.11.011Search in Google Scholar

Melliti, Mimoun. 2019. Publish or perish: The research letter genre and non-Anglophone scientists’ struggle for academic visibility. English Language Teaching Research in the Middle East and North Africa, 225–253. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-319-98533-6_11Search in Google Scholar

Meneghini, Rogerio & Abel Packer. 2007. Is there science beyond English? Initiatives to increase the quality and visibility of non-English publications might help to break down language barriers in scientific communication. European Molecular Biology Organization Journal 8(2). 112–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400906.Search in Google Scholar

Merton, Robert. 1977. The sociology of science. Theoretical and empirical investigations. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.Search in Google Scholar

Meyer de Schauensee, Rodolphe. 1948-52. The Birds of the Republic of Colombia. Caldasia 5(22–26). 251–1264.Search in Google Scholar

Minor, Adriana. 2016. Traducción e intercambios científicos entre Estados Unidos y Latinoamérica: El Comité Inter-Americano de Publicación Científica (1941–1949). In En Gisela Mateos y Edna Suárez (ed.), Aproximaciones a lo local y lo global: América Latina en la historia de la ciencia contemporánea, 183–214. Ciudad de México: Centro de Estudios Filosóficos, Políticos y Sociales Vicente Lombardo Toledano.Search in Google Scholar

Nygaard, Lynn. 2019. The institutional context of ‘linguistic injustice’ Norwegian social scientists and situated Multilingualism. Publishing 7(1). 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7010010.Search in Google Scholar

Politzer-Ahles, Stephen, Jeffrey Holliday, Teresa Girolamod, Maria Spychalskae & Kelly Harper Berkson. 2016. Is linguistic injustice a myth? A response to Hyland (2016). Journal of Second Language Writing 34. 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2016.09.003.Search in Google Scholar

Pratt, Mary. 1991. Arts of the contact zone. Profession. 33–40.Search in Google Scholar

Pratt, Mary. 2003. Imperial eyes: Travel writing and transculturation. London and New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203106358Search in Google Scholar

Quintero, Camilo. 2009. Astrapoterios y dientes de sable: relaciones de poder en el estudio paleontológico de los mamíferos suramericanos. Historia Critica 39. 34–51.10.7440/histcrit39E.2009.02Search in Google Scholar

Quintero, Camilo. 2012. Birds of empire, birds of nation. A history of science, economy, and conservation in United States-Colombia relations. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.Search in Google Scholar

Quintero, Camilo. 2014. Ciencia, nacionalismo y construcción de nación en Colombia, 1920–1950. En Fernando Purcell y. In En Fernando Purcell y Ricardo Arias (ed.), Chile – Colombia. Diálogos sobre sus trayectorias, 155–176. Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes.10.7440/2014.41Search in Google Scholar

Roberts, Lissa. 2009. Situating science in global history. Local Exchanges and networks of circulation. Itinerarios 33(1). 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0165115300002680.Search in Google Scholar

Ros, Cristina. 2020. Lived languages: Ordinary collections and multilingual repertoires. International Journal of Multilingualism 19(4). 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2020.1797047.Search in Google Scholar

Sadlier, Darlene. 2012. Americans All: Good neighbor cultural diplomacy in World War II. Austin: University of Texas Press.10.7560/739307Search in Google Scholar

Salö, Linus. 2022. The spatial logic of linguistic practice: Bourdieusian inroads into language and internationalization in academe. Language in Society 51. 119–141. https://doi.org/10.1017=S0047404520000743.10.1017/S0047404520000743Search in Google Scholar

Shapley, Hikomaro. 1949. The committee on Inter-American Scientific Publication. Science 109(2842). 603–605. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.109.2842.603.Search in Google Scholar

Shehata, Ahmed & Metwaly Eldakar. 2018. Publishing research in the international context: An analysis of Egyptian social sciences scholars’ academic writing behaviour. The Electronic Library 36(5). 910–924. https://doi.org/10.1108/el-01-2017-0005.Search in Google Scholar

Silva, Renan. 2005. Republica liberal, intelectuales y cultura popular. Medellín: La Carreta Editores.Search in Google Scholar

Solli, Kristin & Ingjerd Odemark. 2019. Multilingual research writing beyond English: The case of Norwegian academic discourse in an era of multilingual publication practices. Publications 7(2). 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7020025.Search in Google Scholar

Stockemer, Daniel & Michael Wigginton. 2019. Publishing in English or another language: an inclusive study of scholar’s language publication preferences in the natural, social and interdisciplinary sciences. Scientometrics 118(2). 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1007s11192-018-2987-0.10.1007/s11192-018-2987-0Search in Google Scholar

Strauss, Pat. 2019. Shakespeare and the English Poets: The influence of native speaking English reviewers on the acceptance of journal articles. Publications 7(20). 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications7010020.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Raciolinguistic perspective on labor in the Americas

- Língua e raça no Brasil colonial

- Indexing whiteness: practices of categorization and racialization of social relations among Maroons in French Guiana

- Language, race and work in the Caribbean: a Bakhtinian approach

- Decommodifying Spanish-English bilingualism: aggrieved whiteness and the discursive contestation of language as human capital

- ¿Habilidad o identidad?: tensiones entre las ideologías neoliberales y las raciolingüísticas en el trabajo de los y las jóvenes bilingües de origen latino en EEUU

- International students and their raciolinguistic sensemaking of aural employability in Canadian universities

- Discussion

- Varia

- Positioning English as the international language during the Interamerican scientific integration: the role of multilingualism in defining the scope of a scientific journal in the mid-20th century

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Raciolinguistic perspective on labor in the Americas

- Língua e raça no Brasil colonial

- Indexing whiteness: practices of categorization and racialization of social relations among Maroons in French Guiana

- Language, race and work in the Caribbean: a Bakhtinian approach

- Decommodifying Spanish-English bilingualism: aggrieved whiteness and the discursive contestation of language as human capital

- ¿Habilidad o identidad?: tensiones entre las ideologías neoliberales y las raciolingüísticas en el trabajo de los y las jóvenes bilingües de origen latino en EEUU

- International students and their raciolinguistic sensemaking of aural employability in Canadian universities

- Discussion

- Varia

- Positioning English as the international language during the Interamerican scientific integration: the role of multilingualism in defining the scope of a scientific journal in the mid-20th century