Abstract

The Somali community in Britain has been portrayed as largely homogenous and rather problematic, unwilling to integrate into mainstream British society, a perception that is reinforced by the media and government policies. The government policies tend to ignore the internal diversity and change that the community is experiencing. Drawing on data from a family language policy project, this paper aims to explore intergenerational changes in language preference and use and associated issues of identity within the Somali community in Britain. We look at how the changes in language preference and practice manifest themselves through reported language use and language policies at home, how the changes are affecting the British Somali youths in particular, and how ideas of Somaliness and Britishness are negotiated on an individual level, as well as on a community-wide level through Somali-led organisations. And we highlight the work that the community is doing to tackle issues of intergenerational language shift and Somali identity building. The study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the struggles of the Somali community in Britain in dealing with diversity and change, an understanding that is crucial to the development of appropriate policies regarding the community.

1 Introduction

In 2007, Vertovec used the term “superdiversity” to describe the major population changes in Britain, caused by “a dynamic interplay of variables among an increased number of new, small and scattered, multiple-origin, transnationally connected, socio-economically differentiated and legally stratified immigrants who have arrived over the last decade” (Vertovec 2007: 1024). Vertovec gave the example of Somalis in Britain, who included refugees and asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, secondary migrants from elsewhere in the world but especially from Europe, and British Somalis who were born and brought up in the country. More than a decade on, however, the internal diversity of the ethnic minority communities in Britain remains chronically under-researched, which the studies in this thematic issue seek to redress. For the Somali community in Britain, the internal diversity as outlined by Vertovec has added to the perception that it is a problematic community. The media and policy discourses around the Somalis often focus on the apparent lack of “integration” and “assimilation”, issues such as substance abuse and crime (Adfam 2009), as well as religious extremism (Qureshi 2018). Efforts by policy makers and government officials to solve any perceived problems in the community often disregard the Somalis’ specific heritage, migration histories, generational differences and internal struggles. There is a tendency for policy initiatives to glaze over many of the very real issues of dynamic changes that affect the Somali community internally, such as issues relating to educational attainment, identity, and language shift that affect family relations in particular (e.g. London Borough of Tower Hamlets 2014). Moreover, many policies lump the Somalis together with other minority communities based on their Muslim and Black identities. Such misperceptions and misunderstandings have only worked to marginalise and alienate the Somali community. Although the Somali community has made its own bottom-up efforts to address issues of change that is happening within the community, relatively little academic research has been done on these efforts to gain a more nuanced understanding of the community. Even less empirical research exists on the sociolinguistic situation of the Somali community in Britain. Studies that do exist only focus narrowly on the English language and literacy issues some Somali school-aged children encounter that seem to have contributed to their educational under-achievement (e.g. Kruizenga 2010; Strand et al. 2010). The present study takes a first step towards understanding the sociolinguistic changes that are happening in the British Somali community, with a focus on the intergenerational changes in language preference and use and the concomitant changes in identity, and how grassroots Somali community organisations respond to such changes and to the misperceptions and misunderstandings of their community that are reflected in the media and public policy discourses.

In what follows, we begin with a brief history of Somali migration to the UK, and a sketch of the Somali language and literacy. We then look at how the community is perceived and portrayed in the media and government policies. Afterwards, we look at what has been researched with regard to the language and identity of the Somali community in Britain. The core of the article focuses on research evidence that we have gathered through a family language policy project on intergenerational changes in language preference and use within the British Somali community. We consider how these changes are affecting the identities of individuals as well as the community as a whole and how different sections of the Somali community, especially Somali grassroots organisations, are responding to the changes.

2 Somalis in Britain: history and perception

2.1 Background and demographic data

The relationship between Somalia and Britain was first established in 1884, at which time the northern part of Somalia became a British protectorate and the southern part an Italian colony (Kahin 1997). It was not until the early 1960s that Somalia gained independence and united its northern and southern sides to form the Somali Republic, a unity which was short-lived because of the assassination of President Sharmarkeh and the subsequent military coup by Siad Barre in 1969. In the following decade, tensions began to rise between the north and south of Somalia, eventually leading to a civil war in 1991 and the start of one of the largest refugee crises in the history of the region.

The first Somalis arrived in Britain in the late nineteenth century as merchant seamen working in the British Merchant Navy. They settled in port cities such as Cardiff and Liverpool (Hammersmith United Charities 2018). These migrants were mostly men who worked initially on the ships and at the docks and then had to seek other work opportunities inland largely due to the steady decline of the merchant business. Since then, there have been four notable migration waves from Somalia to the United Kingdom, beginning with wealthy economic migrants who settled in Britain after the Second World War and who heralded mainly from Somaliland. These migrants came in search of new financial opportunities after the economic boom in Britain in the 1950s, and were unattached males, upper-middle class and well-educated with a competence in the English language. Their choice of Britain was mainly due to Somaliland’s status as a British protectorate. As a result of the imported colonial schooling system, English was the language of instruction in schools in Somaliland at the time, though schooling was by no means an entitlement for all Somali children. These early migrants were followed by political refugees fleeing persecution, who came in the late 1980s and 1990s predominantly from southern Somalia. Between 1991 and 2001, the above-mentioned civil war in Somalia triggered another wave of migrants, who came from all regions of the Somali Republic. This group consisted in equal measures of men, women and children.

The Somali family unit has traditionally been an extended one – at times comprising parents, children, grandparents, uncles and aunts – living either under the same roof or in very close proximity to one another (Kahin 1997). The civil war in 1991 and the subsequent mass displacement had a huge impact on the Somali family structure. Many mothers and dependent children were separated from husbands and ended up in faraway countries, with the grandparents left behind. Even in the case of those who managed to unite again as one family in the same new country, different family members may have joined at very different times; typically the grandparents were brought into the new country much later than the others. Many Somali families had to adapt to the situation, and the mothers often had to take on important roles as both caregivers and providers for the family (Hopkins 2010). Moreover, many of those who migrated during this time (1991–2001) were less educated. They spoke little or no English, and a number of the women had no literacy skills in any language (Pattar 2010). The most recent wave of Somali migration, from 2002 onwards, is of transnational, secondary migrants who have travelled through many different countries before settling in the UK. These migrants often have other European languages in their linguistics repertories and have experienced other cultures. According to the Office of National Statistics in the UK, there were 32,100 applications for asylum made by Somali nationals between 1991 and 2000, and 18,000 between 2001 and 2003. The number of Somali asylum seekers has fallen dramatically since then, with applications made from 2010 to 2017 totalling 3,581 (Home Office 2018).

Although there is much dispute about the exact number of the Somali population in the UK, with most census figures not differentiating between Somalis born in the UK or in other countries outside of Somalia before arriving in the UK (Open Society Foundation 2014), the number shown in the 2011 census for England and Wales was 101,370 (ONS 2011). They are scattered across many towns and cities, with the largest concentration in London having a population of over 65,000. It is worth noting, however, that these figures are likely to be under-represented, as they cover mainly those who were born in Somalia.

2.2 Language history of the Somali community

The Somali language is classified as a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. The Cushitic branch comprises 40 languages spoken primarily in the horn of Africa, and Somali belongs to the East Cushitic branch which is related most closely to the languages spoken by the Afar and Oromo tribes in Djibouti and Ethiopia. There is considerable disagreement and confusion over the classification of Somali “dialects”, especially between what has been described in the Somali literature and the western linguists’ categorizations. Most Somali people recognise two varieties that, in their most standard forms, are mutually unintelligible: Af-Maxaa-tiri and Af-Maay. Of the six Somali federal states, five solely implement the Af-Maxaa-tiri, which also forms the basis of standard Somali. Af-Maay is spoken in the South West state, which is dominated by the Digil and Mirifle (Rahanweyn) clans. In addition to these two varieties, there is also Benadiri, which, metaphorically and geographically, is placed in between Af-Maxaa-tiri and Af-Maay, as it is spoken on the Benadir coast from Cadaley to the south of Merca including Mogadishu, the capital city, as well as in the immediate hinterland. Benadiri is also known as Af-Reer Xamar. Phonologically, Benadiri is closer to Af-Maxaa-tiri with some additional phonemes, but depending on the geographical location of the community, it is intelligible to speakers of Af-Maay too. All dialects are represented in the British Somali community. In addition, there are Somali migrants from Djibouti who also know French and the Afar language. Many Somalis also know Swahili and Arabic due to the close historical and geographical relationships with Kenya and Yemen, respectively. These languages, plus other European languages that some Somalis have acquired via their transnational experiences prior to coming to Britain, and the addition of English, make the Somali community as one of the most multilingual immigrant communities in the UK. It has to be said that our fieldwork within the British Somali community showed that the general awareness of dialectal differences seems rather low, especially amongst the younger generations. Most people cannot articulate the differences between the different varieties of Somali or indeed tell what dialect they speak. They tend to refer to their own dialects in terms of clan or tribe names or by geographical origin.

While the first-generation Somalis have a history with and an attachment to the homeland, the awareness of dialectal differences and names is even lower in the younger generations, as the clan and tribal names do not seem to make much sense to them and many have never been to the areas in Somalia that their parents or grandparents come from. There is also a genuine desire to try and overcome any dialectal differences to communicate with each other in the community. Given the ugly history of tribalism in Somalia, the British Somali community has made conscious efforts to downplay the differences and highlight the shared cultural heritage and customs. The downside of these efforts, which have helped to combat tribalism, is that the high multilingual capacity of the community has been concealed.

The Somalis have a rich oral tradition which is often showcased through storytelling in the form of spoken word poetry. Known widely as a nation of poets (Kahin 1997), Somalia has produced large quantities of poetry which have been collected and translated over the years into English by notable academics such as Martin Orwin and organisations such as the Somali English Poetry Collective (Cusmaan et al. 2011). There is Somali poetry on display at the British Museum as part of their Somali Object Journey permanent exhibition. The featured poem is from a collection called Cajabey (Amazement) which was written by Maxamed Ibraahin Warsame “Haraawi” and translated into English verse by W.N. Herbert.

In terms of the written language, however, controversy regarding religious, political and technical questions surrounding language choice meant that no writing system or an official spoken variety could be agreed upon as the national language, and the country resorted to taking Italian, English and Arabic as its official languages after independence in the 1960s (Warsame 2001). It was not until the 1970s after Barre’s military coup that the new government made a final decision about the Somali script and official language (Kahin 1997). The choice made was to use a Roman script which would make use of all the 26 letters with the exceptions of p, v and z. It was then implemented into the education system and rolled out across Somalia. The effort lasted right into the early 1990s, at which point its progress was halted by the civil war. It is because of the short-lived relationship with the standardised script that Somali is considered to be primarily an oral language by many, especially by the Somali people themselves. Different writing systems have come and gone through the long colonial history of the region, with Arabic, Italian and English having been used within the government, as well as in the education system as both school subjects and the medium of instruction (Andrzejewski 1977). Literacy levels in Somali in the Somali community in Britain is generally very low. There is little systematic teaching of the written form of Somali in the UK, which is also true in most Somali diasporas. We will look at some data that reflect individuals’ attitudes toward literacy later. As mentioned above, for those transnational Somali families who have journeyed through other countries before arriving in the UK, it is not unusual that the languages of those nations become part of their linguistic repertoires, though literacy levels in those languages vary considerably depending on the length of stay in those countries by the individuals (Rassool 2004).

2.3 Public perception of the Somalis in the UK

As mentioned above, the Somalis have been portrayed largely negatively in the UK media. The media focus is often on issues such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and on linking gang violence and terrorism to Somali men (Open Society Foundation 2014). Even the apparent under-achievements of Somali children in schools and the poverty experienced by certain sections of the Somali community in the UK are considered the fault of the community rather than a system failure (The Social Mobility Commission 2017). Similarly, the international media coverage of Somalia has focused heavily on famines, droughts, piracy and terrorism, without interrogating the causes (Open Society Foundation 2014). Moreover, stories with alarmist headlines such as “Crime has gone unchecked too long for Somali community in Britain” (The Times 2009) and “How brutal foreign gangs have carved up London, fuelled by cocaine epidemic” (The Sun 2019), in which the Somali community is specifically discussed, have done much to alienate the Somali community. Even articles that attempt to highlight the struggles of Somalis in Britain as part of the BAME (Black Asian Minority Ethnic) communities in the country tend to focus on the “otherness” of Somalis as a group.

“For example, beckoning to a Somali is very offensive,” explains Hassan, who advises the Metropolitan police on community relations. “It is like calling someone a dog.” Knowing this, one can just imagine how a friendly bobby’s curling finger could seem to a Somali youth. ( The Guardian 2005)

This excerpt is from a Guardian article headlined “‘There won’t be another place for us, we’ve lost a whole community’: Somalis in Wembley”. In this excerpt, the subtly implied conclusion is that Somalis – regardless of what generation they belong to or their proficiency in the Somali language and culture – have the same understanding of the particular non-verbal cue mentioned by Hassan. The fact that Hassan is an older man who grew up in Somalia, and thus has an understanding of the Somali language that is not shared by many Somali youths in Britain, does not factor into the discussion. Instead, the writer feeds into the idea of Somalis as a whole being unintegrated into British culture, and that their experiences are largely the same. The use of the very British phrase “friendly bobby’s curling finger” elicits in-group connotations and feelings of membership to the reader, who is made aware in the following sentence that this is likely not shared by the Somali youth who would misunderstand this gesture. The mention of Somali youth plays into the stereotype of Somali young men being violent, no doubt as informed by reports of gang violence among Somali youth in the media. Hassan advises the Met police (The Metropolitan Police Service, responsible for the 32 London boroughs) in general. But it is implied that he is advising the Met police about this particular non-verbal cue as if to say that such misunderstandings can lead to violence from the culturally uninitiated Somalis. It is a subtle way to instil fear of Somalis in the readers and to reinforce the idea that Somali youths, despite the majority of them having been born and raised in the UK, are unable to understand the nuances of the English language and culture.

The idea that the Somali community is too entrenched in its customs to successfully integrate into British society has been much discussed in the press and amongst policy makers (Jordan 2004; Harding et al. 2007). Berns McGowan (1999) speaks of external and internal integrations and argues that the Somalis are challenged in more ways than one where external integration (how well they visibly blend in with the other inhabitants of the host nation) is concerned. Amongst the barriers to entry into British society are language, skin colour and religion (Berns McGowan 1999). Moreover, government strategies such as PREVENT, which was introduced in 2003 by Tony Blair’s Labour government as a means to prevent radicalisation of individuals, has done much to further disenfranchise the Somali community along with other Muslim communities in Britain (Qureshi 2018). The policy encourages individuals to watch and report any behaviour by Muslims in public spaces considered out of the ordinary. Quite specifically, this includes Muslims who might begin to observe Islam more seriously. In 2015, the policy was given new powers when it became a legal duty for public sector workers, including teachers, to adhere to it, thus extending its reach into different sectors of society and fostering a culture of surveillance and distrust both from outside of the Somali community and from within. It is precisely this feeling of distrust that can affect their ways of expressing and practicing their faith (Berns McGowan 1999) and in turn affect the quality of internal integration, as the different groups and generations of Somalis in Britain have rather different attitudes towards and affiliations with religion and other cultural practices.

It is useful to point out that the Somali community lives on the periphery of the Muslim community in the UK. The two largest Muslim communities in Britain are the Middle Eastern Arab and the South Asian communities who are themselves composed of many different ethnic groups that cross over in terms of languages and customs. The Somali community is not part of these better-established communities and has had to forge its own way by creating mosques and other grassroots projects to provide spaces that address their own faith needs. Yet partly due to Somalia’s membership of the Arab league, the Somali community in Britain is often perceived as part of the Arab community (Huffington Post 2014), even though most Somalis would not regard themselves as such. They are also often placed under the banner of the Black community, which is a blanket label for the large and diverse Afro-Caribbean community (another blanket label) in the UK. It seems impossible for the Somalis in Britain to avoid this kind of blanket labelling and generalisation, which ignore the important differences within the community in terms of origin, heritage and migration history, religious affiliation and language. They also make it harder for the Somali community to integrate both internally and with the wider society. Nevertheless, the different generations and groups within the Somali community in Britain are constructing different identities. To them, recognising the differences from within is an important first step to integrate and present a clear and coherent identity for the community in British society generally. We will look at some examples of the grassroots efforts the community has made later in the paper.

3 The present study

The data we use in this article were collected over a period of two years as part of a larger sociolinguistic project on family language policy (FLP) across three transnational communities in Britain, of which the Somali community was one.[1] Data were gathered in the form of: (1) documentary research into the history and demography of the community; (2) an online family questionnaire survey that aimed to collect general information about the sociolinguistic situation within the community; (3) focus groups; (4) one-to-one interviews with Somali community members and stakeholders; and (5) ethnography of language practices in 10 Somali families in London, including video and audio recordings. The details of the data collection can be found in Appendix.1

In the following discussion, we will begin with some general information collected through the online family questionnaire survey. The survey was designed for the FLP project as a whole and the Somali families were only one of the communities that were included in it. The families were invited to respond to the online questionnaire through personal contact of the bilingual research and snowball sampling, i.e. those who were invited by the researcher then invited others. The main data source for the following discussion is the focus groups and stakeholders interviews. The focus groups were held on three different occasions with three different sets of participants, including a group of seven Somali mothers at a Somali-owned tutoring centre in South-East London, a group of five Somali young people between the ages of 17–22 at a college event in West London, and a group of 34 Somali women at a women’s event in Luton. The focus group discussions were conversational in that the Somali-English bilingual researcher asked broad questions to the group and a discussion ensued. The questions were about the participants’ (or their children’s) personal experiences in the education system in the UK, their feelings regarding language use, acquisition and identity, as well as the way in which family relations have been affected due to changing patterns of language use. The focus groups with Somali mothers were asked additional questions regarding family language policy, their language practices at home and their children’s language practices. The stakeholders interviewed were representatives of key community organisations including Ocean Somali Community Organisation, Somali Week Festival, Islington Community Centre and the Anti-Tribalism Movement. We interviewed one key representative from each organisation. The interviews lasted about an hour each and questions were asked about the roles of their organisations, their perceptions of language practices in the community and their key concerns about the community. In what follows we focus on how the different sections of the Somali community respond to the internal changes that are taking place, especially with regard to the intergenerational differences in language preference and proficiency and the associated differences in identity perception and construction.

4 Dealing with change and diversity from within

Our online family questionnaire survey gathered responses from 63 Somali families in Britain and provided useful background data of the language situation of the community. The number may look small, but each family may have more than ten individuals if it is a three-generation family. The questions were about different generations within the family, rather than individuals’ practices. Thirty-nine of the families (62%) who responded to the survey reported that their children had no or limited ability in the Somali language with regards to speaking, and 59 families (94%) said that their children had no or limited ability in Somali literacy. The children in these families were of different ages, with 32 families (51%) having at least one adult child over the age of 18. The parents reported that their preferred language was Somali when engaging in tasks such as reading, listening to the radio, or speaking to extended family members (more than 50% of the families). All the families reported that the grandparents spoke Somali only to the grandchildren, while 35 of the 63 families said the children mixed Somali and English when responding to the grandparents.

The picture that emerged from the survey was further confirmed by our ethnographic observations within the families and by the discussions and interviews with the focus groups and key stakeholders. The contrast in language preference and ability between the children on the one hand and the parents and grandparents on the other is a very common and real concern for all the people we talked to. Adults in the families that we followed in our ethnographic fieldwork often complained about their children’s apparent lack of knowledge in Somali. Poor literacy skills in Somali amongst the younger generation is frequently suggested as an indicator of language shift, though many adults did readily admit that their own literacy level in Somali was not great either. It is interesting to note that many different diasporic communities regard literacy in the heritage language as often a key indicator of language maintenance or shift, even though some, like the Somali community, have a very strong oral tradition and the standardization of the writing system is a fairly recent development from which many adults in the communities have not themselves benefited.

Let us now look at some of the examples from our fieldwork to show what is happening with regard to language preference, proficiency, attitude and ideology in the Somali community in Britain and how families and community organisations respond to the changes and realities.

4.1 Language transmission, literacy and attitude

During our focus group discussions with a group of Somali mothers from the Luton Somali women’s group, the question of how Somali language education should be conducted was raised, and many mothers said that they would encourage learning and using Somali at home, in part because it was the only place that their children would receive this education, and also because language maintenance was seen as a direct link to maintaining their Somali culture and identity. The following has been translated from Somali:

If they don’t learn Somali at home, they won’t learn it anywhere else. (Hawa, age 46)

I have understood that it is on the parents. Parents, especially mothers need to put effort into teaching Somali (to their kids). If the children don’t learn their mother tongue, they will lose their culture. (Fallis, 52)

The sentiment expressed by mothers such as Fallis and Hawa was shared by all the parents we talked to and was also supported by evidence from our family ethnography, where the mothers we observed clearly expressed a desire for their children to learn and maintain their Somali language, as it was felt that this would allow them to maintain a connection with their Somali heritage, their extended families and wider community. In practice, however, there did not seem to be any “deliberate attempt at practicing a particular language use pattern and particular literacy practices within home domains and among family members”, i.e. family language policy (Curdt-Christiansen 2009: 352). Moreover, whereas the family dynamic in Somalia for previous generations saw women’s primary role at home as that of a homemaker, Somali women in Britain have been participating in the labour market outside the home in increasingly high numbers over the past few decades (Westwood and Bauchu 1988), taking up jobs typical for Black women in Britain such as catering, nursing, cleaning, transport, clothing and food manufacture (Ali 2001). These are physically demanding jobs which often involve shift work. The women therefore have less time for their children’s education. In the meantime, the women’s economic contribution to their households is crucial, particularly in the face of increased male and youth unemployment in the community (Westwood and Bauchu 1988). Whilst the changing roles of the women adds another dimension to the diversity within the Somali community in Britain, it does seem to contribute to the language shift that is happening across generations.

Nevertheless, the mothers in our focus groups talked about their own efforts to maintain the Somali language in the home and felt confused and disappointed that the children much preferred to use English. Maidah and Sahro, during our focus group conversation in Luton, expressed the belief that their children’s ability to speak Somali was greatly impeded by their experience at school. The quote from Sahro was in English; that from Maidah was translated from Somali.

When he was small and just had come from Somalia, we used to speak Somali all the time. But now he goes to school and everyday it’s English, English, English. (Sahro, 39)

I always speak with them in Somali, but they answer me in English. It used to be that they would always speak with grandmother, even when they were small, always talking and asking in Somali and then nothing. I can’t tell you why because it happens too quickly that they lose it. (Maidah, 42)

The decreased presence of the mothers at home and the lack of consistent and persistent effort to teach the children Somali may well have contributed to the generational language gap that is being experienced by the families. This also gives credence to the idea that a language shift has already taken root once children reach school age, as reported by many of the respondents in our research, and therefore the concern was no longer how to prevent the change in language preference and proficiency but how to cope with it.

When it comes to the issue of literacy in Somali, the attitude of the parents, especially the mothers, seemed very pragmatic. Here are some of the remarks by the mothers in the focus group:

No, I haven’t taught them how to read or write (in Somali). (Fallis, 52)

We’ve never even tried teaching them to write (in Somali). It’s hard enough getting them to speak! (English) (Sahro, 39)

It would be good to teach them how to read and write their language (Somali), but we haven’t had a chance to do that (English). (Ikram, 38)

Notice first of all that parts of the remarks were made in English by the mothers themselves. In many other diasporic communities in Britain, literacy practices at home are highly important and instrumental in their heritage language maintenance. For example, the Chinese community places enormous emphasis on the need to be able to read and write the Chinese characters to be Chinese amongst the younger generations (Li Wei 1994; Li Wei and Zhu Hua 2010). The Somali families, in comparison, seem to hold a common belief that their language is essentially an oral one and literacy in Somali is not important. This belief is to some extent bolstered by the experience of the parents, many of whom have not engaged with Somali literacy themselves due to the late invention and short-lived implementation of a Somali writing system, and by the knowledge that oral poetry and storytelling have historically been the method to pass down culture and history rather than through print books (Andrzejewski 1977). In contrast to other communities, most Somalis show very little attachment to literacy in Somali. And in the diasporic context, they see even less usefulness of Somali literacy. It should be noted that many of the parents themselves lack literacy skills in the Somali language. This is particularly true for the third and fourth waves of Somali migrants, especially those from poorer, rural areas in Somalia.

At the same time, the mothers did emphasise the importance of literacy skills in English for its academic and practical functions for their children, as this was regarded as necessary for employment, career progression and future success. They also emphasised Arabic literacy for religious practice during our focus group meetings. During our family ethnography, we saw evidence of an emphasis on learning Arabic literacy in six of the ten families that we observed, where children were actively encouraged to engage in reading and writing in Quranic Arabic or learning the Arabic alphabet. It is interesting to note that there seems to be a reverse attitude towards Arabic amongst the Somalis in Britain. Where Arabic literacy seemed highly important for the families we observed, no specific effort was made to teach the children to speak Arabic. This is of course due to the need to read and memorise the Quran. But even in the families whose parents had Arabic in their linguistic repertoires, they did not seem to push the children to learn to speak it. Somali was the dominant language spoken at home by the parents. We will see how the community organisations respond to the issue of literacy later.

4.2 Religious and cultural identities

Berns McGowan (1999) argues that, before emigrating, the observance of Islam varied widely amongst the Somalis in Somalia, but that Somali adults for the most part took their religion for granted. However, after arriving in Europe and being confronted with European cultures, many Somalis turned not to nationalism or clan identity but to religion as a unifying and distinct identity. Although it is clear from McGowan’s study that there are many reasons why the vast majority of Somalis tend to observe their religion more closely after arriving in Europe – including the desire to be known as Muslims – one explanation that came out of our study was that, for some, it was as a way of showcasing them being Somali. Maryan, who is a mother of four and has been in the UK for more than 15 years, expressed this most succinctly at the focus group in London:

Somalis we are Muslims. So, if we are going to live in a non-Muslim country then we should hold steadfast onto our religion and teach our children the Quran and not leave the mosques and the prayers behind. […] When we lived back home, we were just normal, didn’t wear the hijab or anything like that, but we were all Muslims. In truth, we were all a bit uneducated (about Islam). (Maryan, 41; translated from Somali)

This remark was made as a response to a discussion about Muslims who shed their Islamic faith in order to fit in with European cultures. Maryan and some of the other women concluded that as well as being a marker of belonging to the Somali community, adherence to Islam and the pursuit of Islamic education have been ways by which Somali women bond together when in Europe. The opportunities that these Somali women have had to receive a deeper understanding of Islam since arriving in Britain, perhaps as a result of being confronted with other religions and different ways of life, has made them adhere more strongly and strictly to the faith, and encouraged many to wear the hijab although they previously had not felt the need to do so.

In the meantime, the British-born generation of Somalis are experiencing different struggles from their parents when it comes to identity construction, giving rise to the differences and tensions within the community. As noted before, Somali children and youths are often portrayed as under-achieving in the mainstream school system and as causing social problems, even though the cause of the problems are often attributable to the government policies and institutional practices that discriminate against minority ethnic groups (The Social Mobility Commission 2017). The UK’s counter-terrorism strategy, PREVENT, for example, is well criticised for creating “risky and suspect categories” out of Muslim minority communities (Tylor 2018: 851). Despite the government’s claim that PREVENT does not unduly target the Muslim community (Busher et al. 2017), the actual implementation of the policies, particularly after the 2015 mandate to involve public sector actors in the safeguarding of children and the reporting process of suspect behaviour, has seen a sharp rise in Muslim individuals, children especially, being at the receiving end of suspicious monitoring (The Muslim Council of Britain 2016). Stories such as the one of a ten-year-old Muslim boy being questioned by police after misspelling the word “terraced” when writing that he lived in a “terrorist house” (The Independent 2016) are often referenced as examples of how poorly these policies are implemented. These stories can be sensationalised. But they do raise the question of the real-life consequences and effects of such policies. During the course of our research, one of our participating families found themselves at the receiving end of discriminatory treatment from their children’s school. The mother, a 32-year-old woman, revealed that when the teachers were going to call the parent about their son’s bad behaviour at school, the son protested that he would “get into trouble”. Somehow the teachers interpreted this as an indication of child abuse at home and the school called in the police to investigate. The father was in fact ordered to move out of the family home. The family therefore decided that they would leave Britain and move to Egypt.

Incidents like this are unfortunately not uncommon in the Somali community and their effects have been far-reaching. In a study about the relationship between discrimination and violence among Somali Canadian youth, the researchers compared discrimination faced by young Somalis from within their community with discrimination from outside the community. They concluded that the latter was associated with criminal violence among men (Ungar et al. 2017). Dudenhoefer (2018: 153) pointed out that policies like PREVENT foster a culture of alienation and out-group discrimination towards young Somalis where children are viewed as both “at risk and, simultaneously, a risk”, and are likely to create and perpetuate the violent behaviour that it purports to address. Liberatore, in her research about Somali women and the question of security in Britain, talks about the effect of the “multicultural framework” as a means by which to define groups in “totalizing ways, seeing people as separate and different to the majority culture, and thus predicting the behaviour of minority groups” (Liberatore 2017: 115). She goes on to speak about how behaviours that are unacceptable, such as FGM, are attributed to cultural characteristics and thus the whole community is branded as “incapacitated by culture and as lacking in autonomy.”

For families where the parents do not speak enough English and find themselves facing discrimination or even violence, community organisations have proved a valuable resource for providing support. During an interview with the Anti-Tribalism Movement (ATM) – a London-based youth organisation, a representative spoke of how they offer regular sessions for members of their local Somali community to gather and talk about issues of discrimination affecting them, as well as providing spaces where Somali youth and parents can begin to build positive relationships with law enforcement through workshops involving police officers.

Young people have a natural desire to fit in. Yet, according to research from the Social Mobility Commission (2017), there is little institutional space for Black Muslim children and youth to succeed. Within the British Somali community, many young people report feeling as though their parents are unaware or cannot understand the experiences that they go through. Moreover, where parents seem to generally grow closer to Islamic values and practices, as well as guarding more closely the use of the Somali language in the home, many Somali young people report going in the opposite direction (Little 2017). Intra-family tensions are often caused by differences in faith and language preferences. Not speaking Somali is an expression of the young Somalis’ rebellion. Some male Somali youths join others in smoking and drinking against parental advice and Islamic teaching. However, Sporton and Valentine (2007) found in their survey of young Somalis living in Sheffield that only 19% of them self-identified as being British. They went on to explain that young people were hesitant to use the category “British” because they imagined it to be a white identity label. This sentiment was echoed by young Somalis in our study, who, when were asked if they considered themselves British, stated that for the most part they considered themselves to be more Somali than British. Moreover, there were some participants who said that they would never claim their British identity except when differentiating themselves from other members of the Somali diaspora, such as American Somalis. These senses of identity were expressed directly in the following:

Nah I’m Somali. I’m British kinda because I have a passport, but I wasn’t even born here. I don’t think I’m British. (Ayan, 20)

Like if I went to another country, I would say I’m Somali-British but I’m definitely more Somali than British. (Mohomed, 22)

It’s a weird one for me because I don’t speak Somali innit, but I’m Somali yeah, but fish and chip Somali but not British. (Hodan, 18)

The term “fish and chips Somali” is a colloquialism often used by British Somalis to describe Somali youths whose knowledge of the Somali language is weak and who have adapted to British cultural practices including food. Hodan’s sentiments about feeling Somali despite not being fluent in the language is not unique to her. As reported by Rampton, many Somalis often claim Somali as their language, using the terms “my language” or “our language”, despite their low proficiency (Rampton 1995).

When the question of what makes someone Somali was put to both the focus groups of young people and the parents, a few different answers were given. Some remarked that Somaliness was inherent not in language but in lineage – that in order to be Somali one would have to have Somali parents or, in the opinion of some, to have a Somali father, as this would ensure belonging to a clan in accordance with the established patrilineal system. Other participants expressed the opinion that Somaliness existed in degrees, that there was a difference between being technically Somali and culturally Somali, and that proficiency in the Somali language lent itself to the “authenticity” of Somaliness. It is worth noting that the adults, especially the mothers, were particularly articulate in their views on identities. And many of the opinions described here were expressed by the Somali parents in our focus group. Amongst the young people, the overwhelming feeling was that their lack of ability in the Somali language negatively affected their sense of Somaliness and belonging.

During recorded conversations with some of the youths, the idea of feeling suspended between two cultures and not fully belonging to either was frequently expressed. For instance, Ebyan, a 21-year-old university student, articulated this feeling when she was interviewed together with her mother. Ebyan’s mother, Shayma, and the researcher were talking about a trip that the family took to Hargeisa in northern Somalia. The mother was telling the researcher that such trips were important for the children to maintain a sense of their heritage language and culture, when Ebyan stepped in to share her views of her experience during that visit:

But I don’t think that I want to go back to be honest. It was a bit weird and kind of hard to talk to people and it just felt weird I don’t know […] it was nice because it’s my country and my people but at the same time I sometimes felt kind of uncomfortable. Like my cousins and everyone thought it was really funny I was messing up with Somali and every time we would go cafés or shops they’d be like “haa sjuu sjuu”. Made me not want to speak to be honest.

“Sjuu” is a Somali expression often used to describe Somalis who are not fluent speakers of their heritage language. When asked how she felt about speaking Somali now, Ebyan replied:

When I’m speaking with people outside of my family, I feel self-conscious, like I feel like I’m stuttering a lot. I’m very conscious of it and I’m aware that I don’t know words in Somali so I’ll say them in English […] There is a disconnect sometimes when older people say that you don’t know your language, even older people here say that, like my aunty says that a lot.

The conversation then turned to identity and whether Ebyan felt more British or Somali as a result of her struggles with the Somali language.

I just feel like British from a nationality standpoint. I don’t feel like I belong here, but I don’t feel like I belong in Somalia either.

At this point, the mother, Shayma, appearing visibly surprised by her daughter’s revelation, replied:

If you don’t belong to here and you don’t belong to there, you belong to where?

The fact that Ebyan’s mother did not share her sentiment was evident not only in her surprise to learn about her daughter’s struggles with her identity, but also in previous conversations with the researcher, where Shayma expressed that she felt very proud to be Somali. Moreover, this moment showcases clearly the extent of the generational gap that is emerging within Somali families and community in Britain. The link between belonging and heritage language has been much discussed in previous research. Li Wei and Zhu Hua (2016: 657) highlighted that a motivating factor for overseas Chinese individuals and families to learn their heritage languages was to foster and maintain a “sense of belonging and imagination”. Similarly, Cunningham and King (2018: 9) concluded from their research on minority language speaking teenagers in New Zealand that learning their parents’ heritage language was “less about the heritage of the children of migrants, and more about developing belonging in multiple locations”. Clearly the different feelings of belonging of the older and younger generations in the Somali community in Britain – as in the case of Ebyan and her mother – are due to a variety of factors including migration experiences and community involvement. But the realities of different language preferences and proficiencies play a significant role and need more attention in future sociolinguistics research.

4.3 Community responses

Somali community organisations are keenly aware of the diversity and changes that are happening in their community and have tried to formulate practical solutions to address them. Where possible, they have tried to create inclusive spaces for people of different Somali language capabilities, to promote the Somali language and literacy, and to present a positive and more cohesive image of their community. For example, evidence of the awareness of the intergenerational language gap can be seen through the way that events are managed, and materials produced. Figures 1 and 2 are from a pamphlet for the Somali Week Festival. The pamphlet, which is written in English, shows the different events that will be held on each day of the week and the language in which the event will be conducted. What we see here is an example of acknowledging the internal differences within the community and adopting English as a vehicle to bring the Somalis who do not speak Somali into the fold. In this sense, it can be said that this Somali organisation is implementing a pragmatic approach to the language situation of the community – one of the events being publicised is itself focused on the virtues of writing in Somali; nevertheless the event is being organised through the medium of English. We see a similar strategic use of language in other community organisations such as the Islington Community Centre, Ocean Somali Community Organisation and the Anti-Tribalism Movement, whose websites and engagement materials are written in English, even when what they are advocating for is the use of Somali within their facilities and in the community, as well as Somali language literacy.

Somali Week Festival pamphlet of an event aimed at Somali-speaking adults from the diaspora, promoting Somali literacy and literature.

Somali Week Festival pamphlet of a family event created to promote storytelling, literacy and reading in Somali to Somali children in the UK.

Of course, these organizations also have a public-facing function. And some of the organisers are very keen for the non-Somali people and organizations to be aware of what they are doing. But the use of English in their publicity material and as a working language in organizing the events means that more Somali youth who are unable to read in Somali would feel able to participate in them.

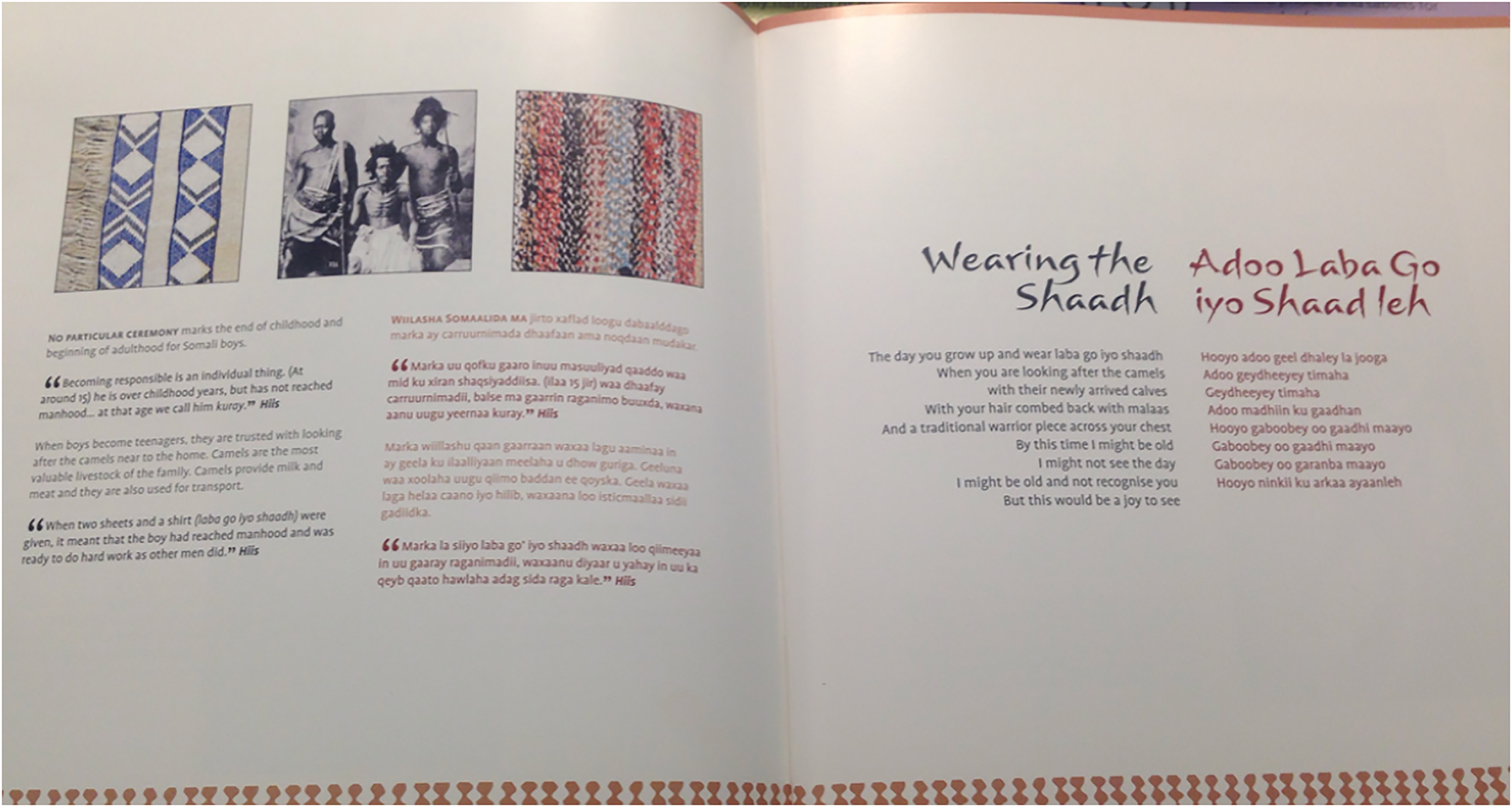

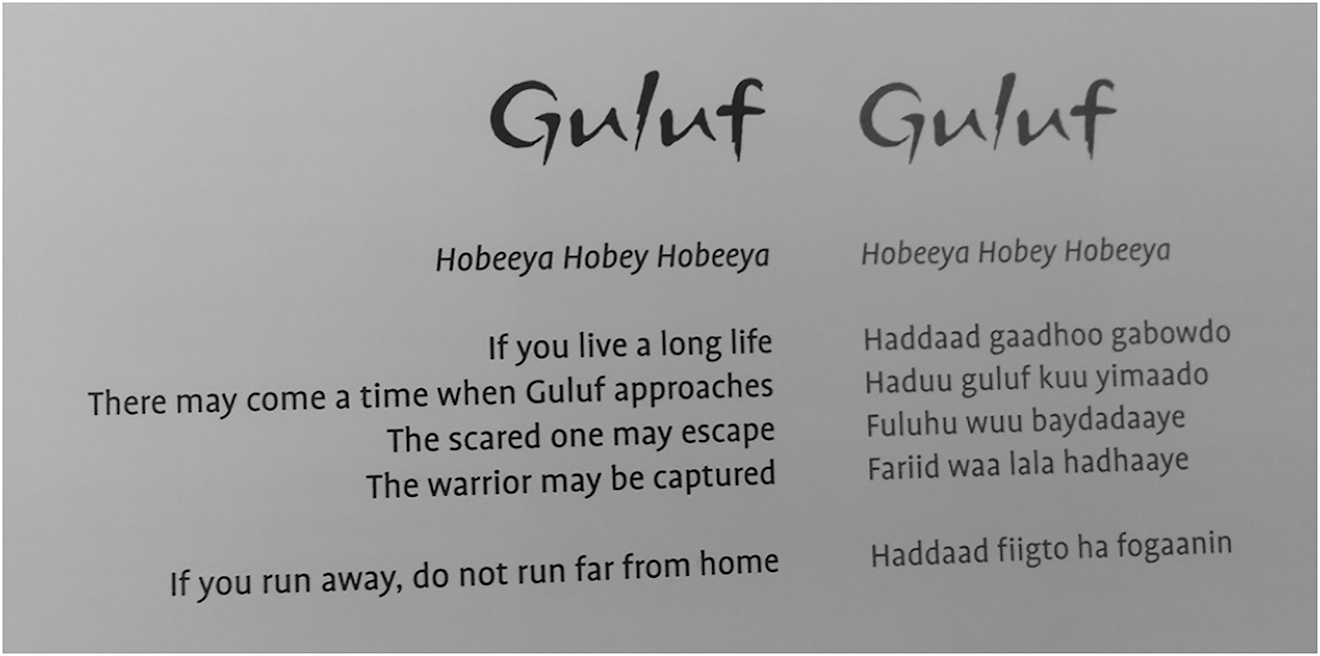

Figures 3 and 4 show examples of a Somali-English dual-language books created by Ocean Somali Community Organisation. The Organisation is a charity based in East London that focuses on helping Somalis access job opportunities, government organisations and other areas in which the language gap might be a factor. They also dedicate resources to the education of Somali children. The example comes from a series of books aimed at Somali families to encourage Somali literacy at home. Similar books that target English-speaking Somali children and celebrate Somali history and culture can be found through online shops and in many libraries in big cities such as London and Birmingham. The community organisations and the key stakeholders whom we interviewed are very much aware of the fact that having a writing system often gives a language higher social status and, by implication, literacy in a language gives its users higher social status, not least in the British context. However, in our ethnographic fieldwork, we did not witness a single occasion of families actually using such literacy materials. What we see, then, is a sharp contrast between the community organisations and the families with regards to their approaches to language and literacy transmission. Whilst the community organisations are pushing for Somali literacy as a measure fuelled by the idea that increased literacy amongst young people will not only help to keep the heritage language alive in the community but also give the community better social recognition and possibly an improved position in society, the Somali parents are choosing to teach Somali via the same methods that they were taught, i.e. verbal interaction. Consequently, although considerable efforts have been made to produce print books and teaching material for the Somali language, the take-up rate by the families has been very disappointing. Some of the community stakeholders that we interviewed expressed a concern that the lack of literacy in Somali is contributing to the generational gap currently being experienced by families. Yet the concern is not evidently shared by the families. Instead, the parents seem to place much emphasis on the ability of their children to be able to converse with family members, especially with the older generations, and through that to maintain familial ties. This is a reality that the community has to face together. It appears that literacy will not work as a unifying tool for the different generations and families. There need to be other ways to develop a stronger identity for the community as a whole if the community so desires. It may well be that the different generations within the Somali community in Britain have already developed different senses of belonging, as we discussed earlier, and that the community has to find ways to live with the differences.

Dual language children’s book showcasing Somali culture, dress and customs.

Dual language children’s book of Somali chidren's ryhmes in Somali and English.

5 Discussion

Intergenerational changes are common and natural phenomena in diasporic communities, with different generations adapting to the cultures and languages of their new home countries at different rates, which not only contributes to the internal diversity of the diasporic communities but also may lead to tensions (Lendzemo and Dirisu 2017). As outlined above, the Somali community in Britain has experienced many different waves of migration. There are families containing two or three British-born generations alongside families who are entirely newly arrived in Britain. Whilst clan affiliation and religion have always been cornerstones of Somali identity, the changes that have occurred in gender relations have added to the internal diversity of the Somali community in Britain. A significant number of women are breadwinners of the family, leading to a flux in the social roles of men in the community and impacting on the function and importance of clan relations that were based on a patriarchal, hierarchical structure (Griffiths 1997). The social networks based on clan affiliations and the role of “elders” in the community have also become less salient with the more established Somali migrants (Griffiths 1997). Younger generations in the community have grown up with rather different experiences of gender relations in the home and a different understanding of and experience with clan affiliation than their parents and grandparents. This has had far-reaching implications on language use and preference, as the former, traditional relations and structures that heavily depended on Somali language and culture have given way to new networks and hierarchies, allowing English to be widely used alongside Somali. Moreover, the transnational nature of the Somali community in the past few decades has meant that families who have access to other cultures and languages in addition to Somali culture and language and British culture and the English language have worked to lend a further layer of internal diversity to the community. As such, attitudes and policies that treat this community as a uniform whole have only exacerbated both internal and external tensions, making integration even harder.

In the UK, the Somali language is given little regard on a systemic and policy level. Kahin (1997), making reference to a report by Cox (1989), states that bilingual teaching support in British schools is used only when necessary to encourage rapid shift to English amongst the recently arrived Somali children. Once the children are able to speak English, support in Somali is withdrawn and the home language disregarded. Naturally, the parents are concerned with their children’s schooling. Without any official recognition of the value of their heritage language, some parents have even started encouraging the use of English in the home, further facilitating the rapid language shift to English (Arthur 2004). Kahin (1997) claims that due to the low status of the Somali language in the British school system and British society in general, caused in part by ignorance, prejudice, and discrimination, English has already become the main language of communication for the younger generations of Somalis in Britain, a claim that has also been borne out by our research evidence, although the ignorance, prejudice and discrimination against the Somali community, including Somali youth, show little signs of diminishing.

The relationship between language and identity is a complex one (Preece 2016), and different generations and groups within the diasporic communities deal with language and identity issues in different ways. In her study of young Somalis and the problematization of culture, Liberatore (2017) discusses how culture is used across the political spectrum as a way to stereotype groups and demonize them as creatures bound by their cultural practices without any real sense of autonomy. In the Somali community in Britain, the social prejudice and racial discrimination that has been levelled against them have pushed the older generations to hold firmly onto their cultural heritage, including language. They also want their children to inherit and maintain the ethnic language. The younger generations, though, do not tend to feel that having the Somali language necessarily strengthens their position in British society. They seek to develop a more complex identity as British Somalis who can operate in both Somali and English. Abikar (2013), for example, showed that the Somali parents in his study regarded the Somali language as a core constitutive factor of being part of the Somali community in Britain and would insist on the children, irrespective of where they were born, acquiring the Somali language. Amongst the Somali youth that Abikar studied, however, the Somali-born ones were experiencing language attrition and loss whilst the British-born ones had never acquired the language to such a level that they could comfortably use it in everyday social interaction. Indeed, many of the British-born Somali youth have never been to Somalia and cannot fully identify with the nation, its culture or language. They regard themselves as British, or more precisely British Somali. From both the interviews with the Somali youth and conversations with the children in the families during ethnographic fieldwork, the younger generations of Somalis resonated with the idea that English as their primary language was just a fact of their circumstances. This is more of a case of accepting their present position in British society rather than actively identifying with the language and culture. Some of them expressed a sentiment that they could never really be British because they are not white. They are trying to forge a new and complex Somali British identity through English-dominated bilingualism, but are clearly struggling with it.

The intergenerational differences in language preferences and proficiency and in social identification have a major impact on the family dynamics in migrant communities. Often grandparents and grandchildren are unable to communicate smoothly with each other because the children have not acquired a sufficient level of their heritage language whereas the grandparents have not acquired a sufficient level in the dominant language of society. In many families, even the relatively young parents have limited English and operate primarily in their ethnic and community languages. Barwell (2005) highlights the linguistic generation gap within the Somali community in Britain, where interactions between the Somali-born and the non-Somali-born generations are becoming quite problematic due to differences in language proficiency and attitude. There are of course diverse and complex reasons why the younger generations have not acquired sufficient Somali and the older generations have not acquired sufficient English. But the consequence of the apparent linguistic generation gap is that elderly grandparents, particularly grandmothers who are less likely to venture out and form social circles of other women of similar ages, can sometimes find themselves isolated, as other family members have little time to interact with them in Somali (Kensington and Chelsea Social Council 2011), whilst Somali youth feel pushed to seek a different identity from their parents and grandparents. Moreover, the identities of grandparents as elders of great importance within the family, as mandated by clan structures (Griffiths 1997) is also affected by the language preferences of, and subsequent reduced interaction with, the youth, thereby creating an identity crisis in the older generation as well. As Sporton and Valentine (2007) and Palm et al. (2019) pointed out, the young Somalis who have grown up outside of Somalia have very limited memories and experiences of the homeland for them to draw upon. As reported by the Somali youths in our project, their primary source of understanding of Somali culture is their families and communities. Yet their natural and genuine desire to be part of the British youth generation and culture means that they feel the need to own the English language first. In this sense, what seems to be a practical, context-induced language choice becomes identity-driven. For the parents and grandparents, on the other hand, maintaining Somali is more of an emotional investment as it may help to preserve aspects of their memories and life experiences that are vital to their own identity (see also Little 2017).

6 Conclusion

The Somalis in Britain are a diverse group, with different reasons for and histories of migration, countries of birth, clan affiliations and languages. Further differences have emerged as a result of intergenerational changes that are happening within the community. In this regard, differences in language preference and proficiency are most prominent and impact on individual identity, family dynamics and community cohesion. The failure of the media and public policies in the UK to recognise the internal diversity of the Somali community has led to misunderstanding, prejudice and discrimination. There is a false impression that the Somali community in Britain as a whole is somehow unwilling to integrate into the British culture and society. Yet, the Somali community believes that the younger generation, especially the British-born generation, have shifted too much from their traditional values and practices and no longer identify themselves, or could be identified, as Somalis only, but as British Somali or even simply British. As the examples we have looked at in this article show, language plays a crucial role in the internal tensions the Somali community is experiencing. The differences in language preference and proficiency are symptomatic of the intergenerational changes that are taking place. The language experience of the younger generations means that closer connections with elders in the family are difficult to form and sustain. Similarly, there is difficulty from the elders’ side in relating to the experiences and struggles of the British-born youth. As a consequence, relationships and emotional bonds across the generations grow strained. The preference of English amongst Somali youth is causing a great deal of concern to the community as a whole. Community organisations and the key stakeholders are very much aware of these issues. Grassroots initiatives tend to take a pragmatic approach by creating spaces for both Somali and English to co-exist and to be co-used, whilst encouraging an increased engagement with Somali literacy at the same time in hopes of boosting the maintenance of the Somali language and identity, as well as the community’s general status in society. Nevertheless, as our examples show, not all the families and individuals respond to the community organisations’ initiatives in the same positive way. It is fair to say, then, that the Somali community in Britain as a whole is struggling with a coherent identity and appropriate ways of addressing the internal diversities. The nature of Somaliness in the diasporic context is a question for the community to explore and reflect on in the years to come.

Understanding the struggles that the Somali community in Britain is experiencing in dealing with internal diversity as manifested in the changes of language preference and proficiency and the associated changes in identity is, in our view, an important step towards developing appropriate social policies that avoid stereotypes and discrimination and meet the different needs of different sections of the community. The largely negative and monolithic portrayal of the Somalis in the British media, alongside one-size-fits-all government policies for ethnic minority communities generally, have been counter-productive for the community when trying to address significant changes that have taken place across generations, as well as young Somalis’ ability to find grounding in their British and Somali identities. We hope that our study helps to reveal some of the key issues of diversity and change that the community is dealing with, issues to which policy-makers and the media will begin to pay more attention.

Funding source: Economic and Social Research Council

Award Identifier / Grant number: ES/N019105/1

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Somali community organisations that took part in this research – Ocean Somali Community Organisation, Somali Week Festival, Islington Community Centre and the Anti-Tribalism Movement. A special thank you to Sahra Dire from the Luton Somali Women’s Group, who helped to organise focus groups for the purposes of this research. The paper draws data from the project Family Language Policy: A Multi-level Investigation of Multilingual Practices in Transnational Families, funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) of Great Britain (ES/N019105/1). Part of the paper was presented at the 5th International Conference “Crossroads of Languages and Cultures: Languages and Cultures at Home and at School” (CLC5) in 2018. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers, the editors of this special issue and the editor of the journal for their critical but constructive comments.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) of Great Britain (ES/N019105/1).

Appendix: Data from the study for this article

| Tools of enquiry | Participants | Time or frequencies of data collection | Data collected | Key questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus group | Group 1: twelve women in Luton Group 2: seven mothers in London Group 3: five young people (17–22) in London |

One sitting for each focus group | Approx. 1.5 h of recording per sitting | Family language policy (FLP) questions Identity questions Community perception |

| Individual/pair (two interviewees) interviews | 10 mothers 12 young people aged (15–23) Five community stakeholders from Somali led organisations |

One interview per sitting | Approx. 20–30 min each | Individual migration histories Identity questions FLP questions |

| Ethnography | 10 families | 1-h visits once a week for two years | Audio, video recordings and observation notes | What FLPs are in use in the home setting How family relationships are impacted by language use and language education |

| Documents | Children’s books Somali organisations’ media Gov policy documents Media reports |

Over two years | Reports Leaflets Articles Websites |

Policies regarding the Somali community How the Somali community is presented and perceived; community responses |

| Online family questionnaire | Families | Six months | Questionnaire returns | Language practices and attitudes |

References

Abikar, Shamsudin. 2013. Loss and maintenance of Somali language in the UK. Arab World English Journal 4(4). 285–309.Search in Google Scholar

Adfam. 2009. Becoming visible: The Somali community and substance use in London. https://adfam.org.uk/files/docs/becoming_visible.pdf (accessed 2 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Ali, Emua. 2001. Somali women in London: education and gender relations PhD thesis. London: UCL.Search in Google Scholar

Andrzejewski, Bogumił W. 1977. The introduction of a National Orthography for Somali. London: School of Oriental and African Studies.Search in Google Scholar

Arthur, Jo. 2004. Language at the margins: The case of Somali in Liverpool. Language Problems & Language Planning 28(3). 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1075/lplp.28.3.01art.Search in Google Scholar

Barwell, Richard. 2005. Working on arithmetic word problems when English is an additional language. British Educational Research Journal 31(3). 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920500082177.Search in Google Scholar

Berns McGowan, Rima. 1999. Muslims in the diaspora: the Somali communities of London and Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.10.3138/9781442677470Search in Google Scholar

Cunningham, Una & Jeanette King. 2018. Language, ethnicity, and belonging for the children of migrants in New Zealand. London: Sage.10.1177/2158244018782571Search in Google Scholar

Curdt-Christiansen, Xiao Lan. 2009. Invisible and visible language planning: Ideological factors in the family language policy of Chinese immigrant families in Quebec. Language Policy 8(4). 351–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-009-9146-7.Search in Google Scholar

Cusmaan, Abyan, Jawaahir Daahir & Idil Osman. 2011. Somalia to Europe: stories from the Somali Diaspora. Leicester: Quaker Press.Search in Google Scholar

Dudenhoefer, Anne-Lynn. 2018. Resisting radicalisation: A critical analysis of the UK prevent duty. Journal for Deradicalization 14(1). 154–191.Search in Google Scholar

Griffiths, David. 1997. Somali refugees in Tower Hamlets: Clanship and new identities. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 23(1). 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.1997.9976572.Search in Google Scholar

Harding, Jenny, Andrew Clarke & Adrian Chappell. 2007. Family matters: Intergenerational conflict in the Somali community. http://karin-ha.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/intergenerations.pdf (accessed 2 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Hammersmith United Charities. 2018. The Somali sailors: Ethnic community’s oral history project. http://hamunitedcharities.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Somali-Sailors.pdf (accessed 18 August 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Huffington Post. 2014. Why Somalia should leave the Arab league. https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/awoowe-hamza/arab-league_b_5397888.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAEeiSFjUck6CwldiqsMqFDweHHEFbl-RYtUcsShkz4bqI7l6IApvJ0rBW8sXsMBMYTNvyoT0j3lAtibOMjE4daBLdY-j9Bx_k3vdkWknnRtopNxpiZDICLvoS2z5uvqmDbRwOWUUs3mbDXTp3Z6iTlnFobH3V0nT2dVtRfT6fbmn (accessed 18 August 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Home Office. 2018. Table as_01: Asylum applications and initial decisions for main applicants, by country of nationality. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immigration-statistics-year-ending-september-2018/list-of-tables.Search in Google Scholar

Hopkins, Gail. 2010. A changing sense of Somaliness: Somali women in London and Toronto. Gender, Place & Culture 17(4). 519–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369x.2010.485846.Search in Google Scholar

Jordan, Glenn & Abdihakim Arwo. 2004. Somali Elders: Portraits from Wales (Odeyada Soomaalida: Muuqaalo ka yimid Welishka). Cardiff: Butetown History & Arts Centre.Search in Google Scholar

Kahin, Mohamed. 1997. Educating Somali children in Britain. Staffordshire: Terntham Books Limited.Search in Google Scholar

Kensington & Chelsea Social Council. 2011. The Somali diaspora in Kensington and Chelsea. https://www.councilofsomaliorgs.com/sites/default/files/resources/Somali_Diaspora_in_Kensington_Chelsea.pdf (accessed 2 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Kruizenga, Teresa M. 2010. Teaching Somali children: What perceived challenges do Somali students face in the public school system? International Journal of Education 2(1). E12. https://doi.org/10.5296/ije.v2i1.334.Search in Google Scholar

Lendzemo, Constantine Yuka & Jesse Bayodele Dirisu. 2017. Lexical attrition and language shift: The case of Uneme. Studies in Linguistics 43(2). 119–139.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Wei. 1994. Three generations, two languages, one family: Language choice and language shift in the Chinese community in Britain. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Wei & Zhu Hua. 2010. Voices from the diaspora: Changing hierarchies and dynamics of Chinese multilingualism. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 205. 155–171.10.1515/ijsl.2010.043Search in Google Scholar

Li, Wei & Zhu Hua. 2016. Transnational experience, aspiration and family language policy. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37(7). 655–666.10.1080/01434632.2015.1127928Search in Google Scholar

Liberatore, Giulia. 2017. Somali, Muslim, British: Striving in Securitized Britain. London: Bloomsbury Business.Search in Google Scholar

Little, Sabine. 2017. Whose heritage? What inheritance?: Conceptualising Family Language identities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23(2). 198–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1348463.Search in Google Scholar

London Borough of Tower Hamlets. 2014. Supporting new communities, case study of the Somali community. Available at: https://www.councilofsomaliorgs.com/sites/default/files/resources/Supporting_New_Communities_Report_Final.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Office of National Statistics. 2011. 2011 census. https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census (accessed 2 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Open Society Foundation. 2014. Somalis in London: Somalis in European cities. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/uploads/cfbed57a-9d85-454f-9e8d-d65b3aeaf1b9/somalis-london-20141010.pdf (accessed 2 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Palm, Clara, Natalia Ganuza & Christina Hedman. 2019. Language use and investment among children and adolescents of Somali heritage in Sweden. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40(1). 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2018.1467426.Search in Google Scholar

Pattar, Kanwal. 2010. Community cohesion and social inclusion - ESOL learners’ perspective: Leadership challenges. Coventry: Lancaster University Management School.Search in Google Scholar

Preece, Siân. 2016. Routledge handbook of language and identity. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315669816Search in Google Scholar

Qurashi, Fahid. 2018. The prevent strategy and the UK ‘war on terror’: Embedding infrastructures of surveillance in Muslim communities. Palgrave Communications 4(1). 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0061-9.Search in Google Scholar

Rampton, Ben. 1995. Crossing: Language and ethnicity among adolescents. London: Longman.Search in Google Scholar

Rassool, Naz. 2004. Sustaining linguistic diversity within the global cultural economy: Issues of Language rights and linguistic possibilities. Comparative Education 40(2). 199–214.10.1080/0305006042000231356Search in Google Scholar

Sporton, Deborah & Gill Valentine. 2007. Identities on the move: The integration experiences of Somali refugee and asylum seeker young people. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.268533!/file/identities_on_the_move.pdf (accessed 2 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Strand, Steve, Augustin de Coulon, Elena Meschi, John Vorhaus, Lara Frumkin, Claire Ivins, Lauren Small, Amrita Sood, Marie-Claude Gervais & Hamid Rehman. 2010. Drivers and challenges in raising the achievement of pupils from Bangladeshi, Somali and Turkish backgrounds. London: Department of Children, Schools and Families.Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, Joel David. 2018. ‘Suspect categories,’ alienation and counterterrorism: Critically assessing PREVENT in the UK. Terrorism and Political Violence 32(4). 851–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2017.1415889.Search in Google Scholar

The Guardian. 2005. There won’t be another place for us, we’ve lost a whole community. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/jan/21/britishidentity8 (accessed 14 August 2020).Search in Google Scholar

The Independent. 2016. Schoolboy questioned by Lancashire police because he said he lived in a “terrorist house”. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/schoolboy-questioned-lancashire-police-because-he-said-he-lived-terrorist-house-a6822231.html.Search in Google Scholar

The Muslim Council of Britain. 2016. The impact of prevent on Muslim communities: A briefing to the labour party on how British Muslim communities are affected by counter-extremism policies. Available at: http://archive.mcb.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/MCB-CT-Briefing2.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

The Social Mobility Commission. 2017. The social mobility challenges faced by young Muslims. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/642220/Young_Muslims_SMC.pdf (accessed 2 May 2020).Search in Google Scholar

The Sun. 2019. How brutal foreign gangs have carved up London, fuelled by cocaine epidemic. https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/10813615/how-london-is-being-infiltrated-by-brutal-foreign-hitmen-and-cocaine-kingpins-leaving-the-streets-wracked-with-fear/(accessed 14 August 2020).Search in Google Scholar

The Times. 2009. Crime has gone unchecked too long for Somali community in Britain. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/crime-has-gone-unchecked-too-long-for-somali-community-in-britain-66kcgkcxmg8 (accessed 14 August 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Ungar, Michael, Kristin Hadfield, Amarnath Amarasingam, Sarah Morgan & Michele Grossman. 2017. The association between discrimination and violence among Somali Canadian youth. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44(13). 2273–2285. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2017.1374169.Search in Google Scholar

Vertovec, Steven. 2007. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30(6). 1024–1054. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870701599465.Search in Google Scholar