Abstract

This paper presents a method for extracting rice bran oil using magnetic immobilized cellulase (MIC) in a magnetic fluidized bed (MFB). Cellulase was immobilized on Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (glycydylmethacrylate) with an average grain size of 120 nm. The rice bran was hydrolyzed using MIC combined with magnetic immobilized alkaline protease to extract rice bran oil. Under intermittent conditions, the MIC concentration was 1.6 mg/g, the liquid to material ratio was 4:1, the enzymatic hydrolysis time was 150 min, and the oil yield was as high as 85.6 ± 1.20% at 55 °C. The fluid in the MFB had a magnetic field strength of 0.022 T, a flow velocity of 0.005 m/s, and an oil extraction rate of 90.3%. This provides a theoretical basis for the extraction of rice bran oil using the subsequent MFB hydroenzyme method.

1 Introduction

Rice bran is a byproduct of rice processing. Approximately one-fifth of rice bran oil (RBO) is found in rice bran. The fatty acid composition of RBO is relatively balanced, and RBO is rich in dozens of natural bioactive components, such as Ve. RBO is added to other oils to improve their antioxidant properties [1, 2]. Therefore, RBO has attracted much attention as a healthy vegetable oil.

Currently, the most commonly used RBO extraction methods include the pressing method, solvent extraction, supercritical CO2, and enzyme method. The pressing method has disadvantages in that it requires high labor intensity, is susceptible to protein degeneration, and has low oil extraction rate (OER) [3]. Organic solvent extraction carries the risk of solvent legacy and may cause environmental pollution. Supercritical CO2 extraction technology has drawbacks such as a large investment in production infrastructure and challenges in maintaining continuous production [4]. Aqueous enzymatic extraction (AEE) is a novel method for safe and convenient extraction of oil from plant cells by mixing enzymes with water. AEE has less strict conditional requirements and produces less pollution than other extraction methods, and the extracted oil has high quality and fewer byproducts [5, 6]. It is also conducive to the preservation and collection of other nutrients from the rice bran. At present, AEE has been studied in peanut [7], sesame [8], and other crops. The main process for AEE involves deconstructing oil crops using various enzymes that can decompose the cell wall [9] and liposome-related protein [5]. The type of enzyme used varies for different raw plant materials, mainly because the type of added enzyme depends on the cellular composition and structure of the oil-containing material. The most commonly used biological enzymes are cellulase, protease and phosphatase. However, free cellulase is difficult to recycle, unstable, and uneconomical and has other disadvantages [10]. To alleviate the limitations of cellulase, immobilization technology was applied to the enzymatic hydrolysis process to improve the reuse potential, efficiency and stability of cellulase.

Among the numerous support materials for immobilized enzymes, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have been favored due to their superparamagnetic properties, good biocompatibility and easy separation; they have been used in medical environmental, and other fields [11]. Under the action of a magnetic field, magnetic particles arrange into an orderly manner along the direction of the magnetic field lines. At this time, the interfacial contact area between the magnetic carrier and the mobile phase is large, and this is beneficial to mass transfer and heat transfer [12]. Yu et al. [13] found that the stability and reuse of phospholipase A1(pl A1) was improved when immobilized on magnetic Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) nanoparticles.

The magnetic fluidized bed (MFB) is a fluid-solid phase treatment system that introduces a magnetic field to a conventional fluidized bed, uses magnetic particles as a bed medium, and is a novel and efficient special fluidized bed system. In industrial processing, MFB can avoid destroying the structure of magnetic catalytic particles, increase mixing uniformity, improve production efficiency and realize continuous production [14]. At present, the application of MFB equipment has seen research results in energy [15], environmental engineering [16, 17], and other fields. However, there is no research on the application of aqueous enzymatic extraction oil to MFB.

In controlled experiment, the reactions and fluidization state in the MFB cannot be seen by the naked eye, but the internal reaction flow and phenomenon can be understood via numerical simulation. Yue et al. [18] simulated the movement of nanomagnetic immobilized lipase particles in liquid-solid MFB using OpenFOAM software. MFB can effectively improve the reaction efficiency and stability of immobilized lipase particles, increase phytosterol conversion and deacidification in rice bran crude oil. Mahdi Ramezanizadeh et al. [19] studied the effects of mass flow rates of cold stream and hot stream inlet temperatures on the heat transfer rate through computer simulations. Zhao et al. [20] simulated the rolling circulating fluidized bed (RCFB) particle distribution. Ez Abadi et al. [21] conducted the first experimental and numerical study of the influence of channel number on the temperature and humidity ratio of the product and on other important parameters.

In this study, cellulase was immobilized on magnetic supports to used to hydrolyze rice bran under intermittent conditions. Conditions for hydrolyze rice bran were optimized. Under optimal conditions, then added a magnetic immobilized alkaline protease, the rice bran oil was extracted in the MFB. Three-dimensional numerical simulation was carried out using OpenFOAM software to study the effect of magnetic field intensity and inlet flow rate on the fluidized state in order to achieve the best enzymatic hydrolysis effect. This paper focuses on the enzymatic hydrolysis of MIC, and other expert on the team continued the study by providing a theoretical basis for the subsequent industrial AEE of RBO.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Fresh rice bran was obtained from Heilongjiang Beidahuang Rice Industry Group Co. Ltd. Cellulase (10% initial enzyme activity, 10,000 U/g), alkaline protease (10,000 U/g), Fe3O4, silica, ammonia, tetraethyl orthosilicate, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), 2-bipyridine (Bpy), chloroacetyl chloride, triethylamine (TEA), glutaraldehyde, and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) were obtained from Chinese Medicines Reagent Co. Ltd; γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES, 98%), glycidyl methacrylate (GMA), GuCl, and GuCl2 were obtained from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co. Ltd; Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 was obtained from Shanghai Boo Technology Co. Ltd. The above listed reagents and other reagents were analvtically pure.

2.2 Testing methods

2.2.1 Preparation of magnetic supports

Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) was prepared following the method of Lei et al. [22] with some procedural modifications. Fe3O4 was first prepared by a co-precipitation method. Then 0.5 g of Fe3O4 particles was added to 160 ml of ethanol and evenly dispersed under ultrasonic vibration in a water bath. Forty milliliters of water, 5 ml of ammonia water, and 1 ml of TEOS were added to the dispersion and stirred for 24 h. Magnetite was separated from the permanent magnet, modified by APTS, and dispersed in DMF solution. Chloroacetyl chloride (3 ml) and DMF (6 ml) were added, and the solution was stirred for 12 h. The nanoparticles were separated with a magnet, washed thoroughly with toluene and ethanol, and then dried inside a vacuum. The composite particles were prepared by adding 1 g to the 20 ml [DMF/water] (1:1, v/v) mixing system, and a 50:0.5:0.1:1 ratio of [GMA]/[CuCl]/[CuCl2]/[Bpy] was added for the reaction. The resultant product was washed for approximately 48 h with acetone and dried in a 40 °C vacuum oven.

2.2.2 Preparation of magnetic immobilized cellulase

One milligram of support was impregnated with sodium acetate-acetic acid buffer solution (0.05 M, pH 5.0) for 10 h. At 50 °C, 6% glutaraldehyde solution and 1 mg/ml cellulase solution were added and mixed for 3 h. The solution was centrifuged to obtain magnetic enzymes. The resultant product was cleaned with sodium acetate-acetic acid buffer solution and stored at 4 °C.

2.3 Characterization and analysis of magnetic supports and MIC

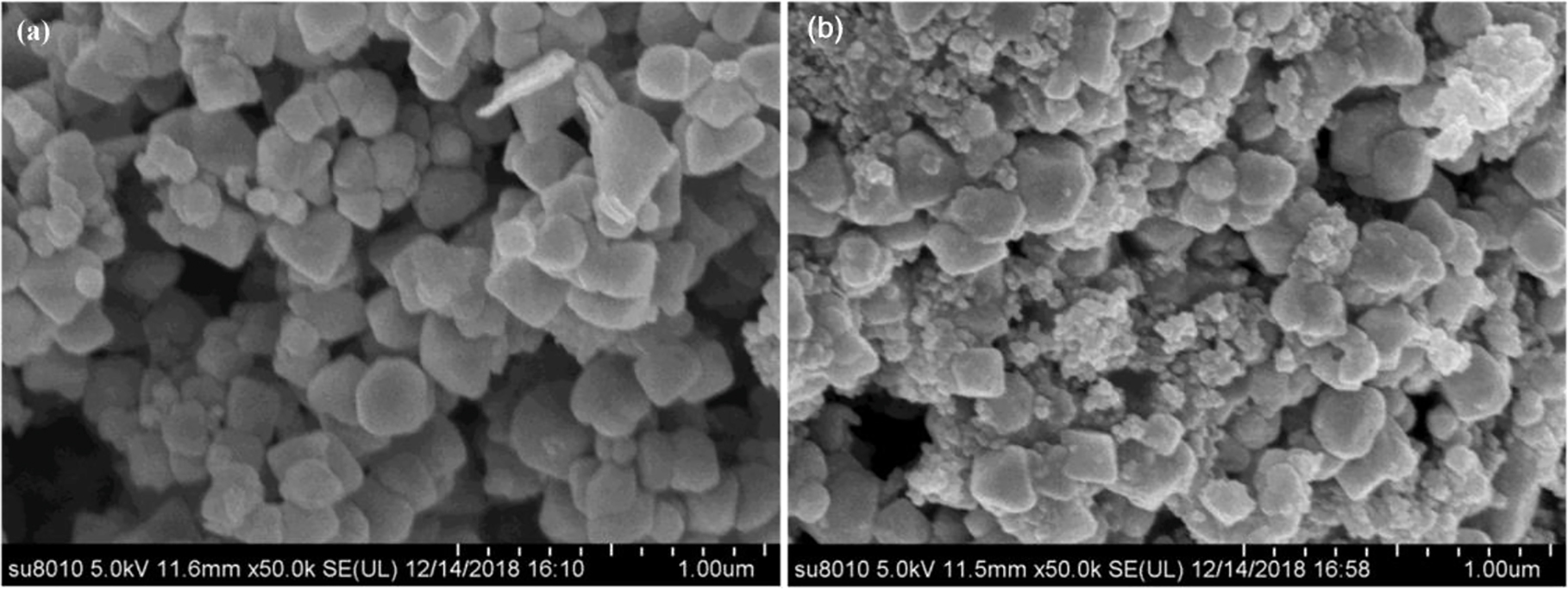

The samples were gold-plated (90 s) inside a vacuum, and the size and shape of the samples were examined under a S-3400N scanning electron microscope (SEM).

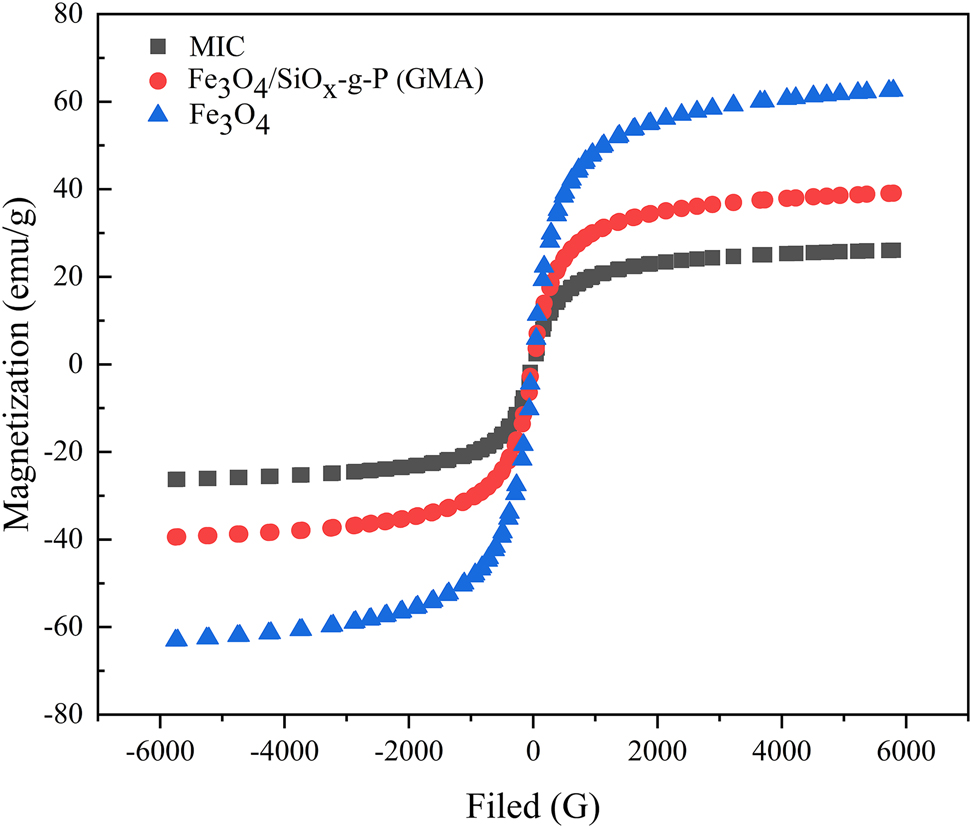

At 25 °C, the samples were placed into a vibrating sample magnetometer, and the hysteresis loops of the samples were tested in the range of −6000 Oe to 6000 Oe to analyze the magnetic properties of the samples.

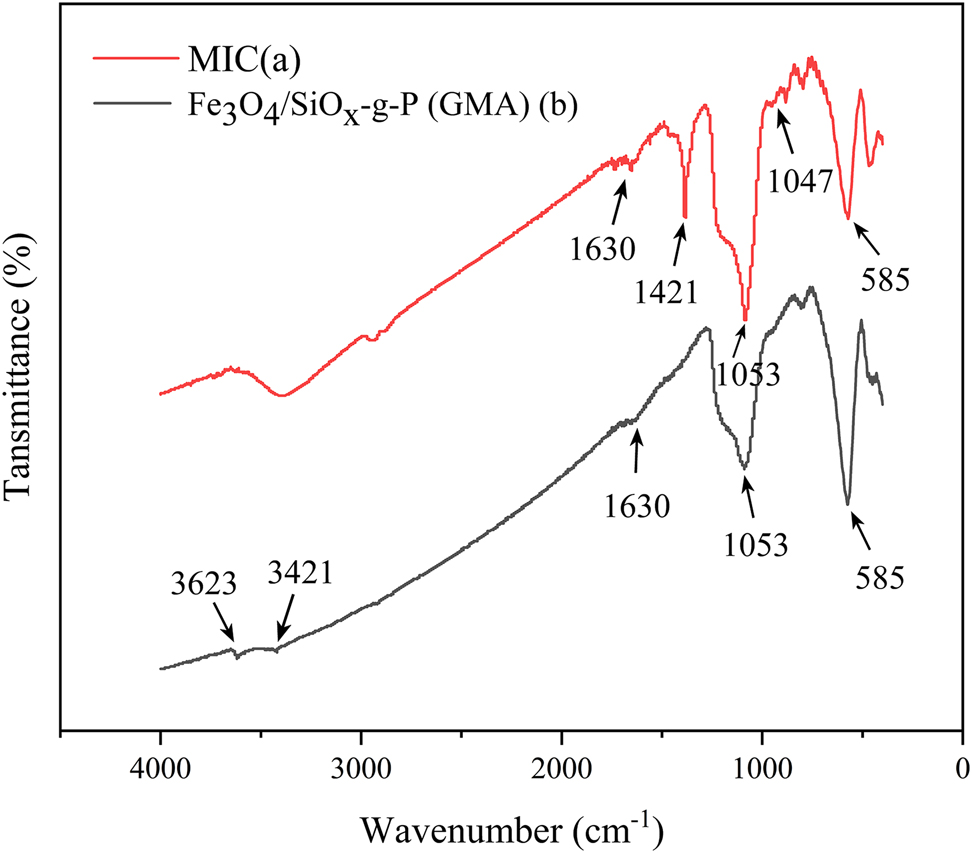

After drying for 2 h, the KBr pressing method was used. The samples were analyzed by an 8400 S infrared spectrometer for testing using scanning areas of 4000–400 cm−1 and a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.4 Enzymatic reactions under intermittent conditions

From an initial amount of rice bran powder, rice bran with uniform shape distribution was obtained via passage through a 60 mesh sieve. The rice bran was pretreated with steam. According to the solid to liquid ratio, a suitable MIC concentration was added at an appropriate temperature at pH 5.0 and then stirred for a set period of time. Alkaline protease at a concentration 9 mg/g was added. When the reaction was complete, the enzyme was inactivated for 15 min at 95 °C and centrifuged after cooling. The components obtained, listed in order from the top to the bottom of the emulsion, were the rice bran oil I, emulsion, hydrolysate and solid residue. Rice bran oil I which was located at the top of the emulsion, was separated form the other components. The emulsion was heated to 100 °C continuously stirred for 20 min, and centrifuged after cooling to obtain rice bran oil II. The sum of the oil I and oil II volumes equal the net oil output.

2.5 Numerical simulation of MIC in a MFB

For the numerical simulation in this study, the reactions used rice bran solution as the liquid phase and MIC particles as the discrete phase. Correlation equations of the applied uniform magnetic field were obtained according to the method documented by Wang et al. [23]. Numerical simulation was carried out using OpenFOAM software.

2.5.1 Boundary conditions and establishment of the numerical simulation model

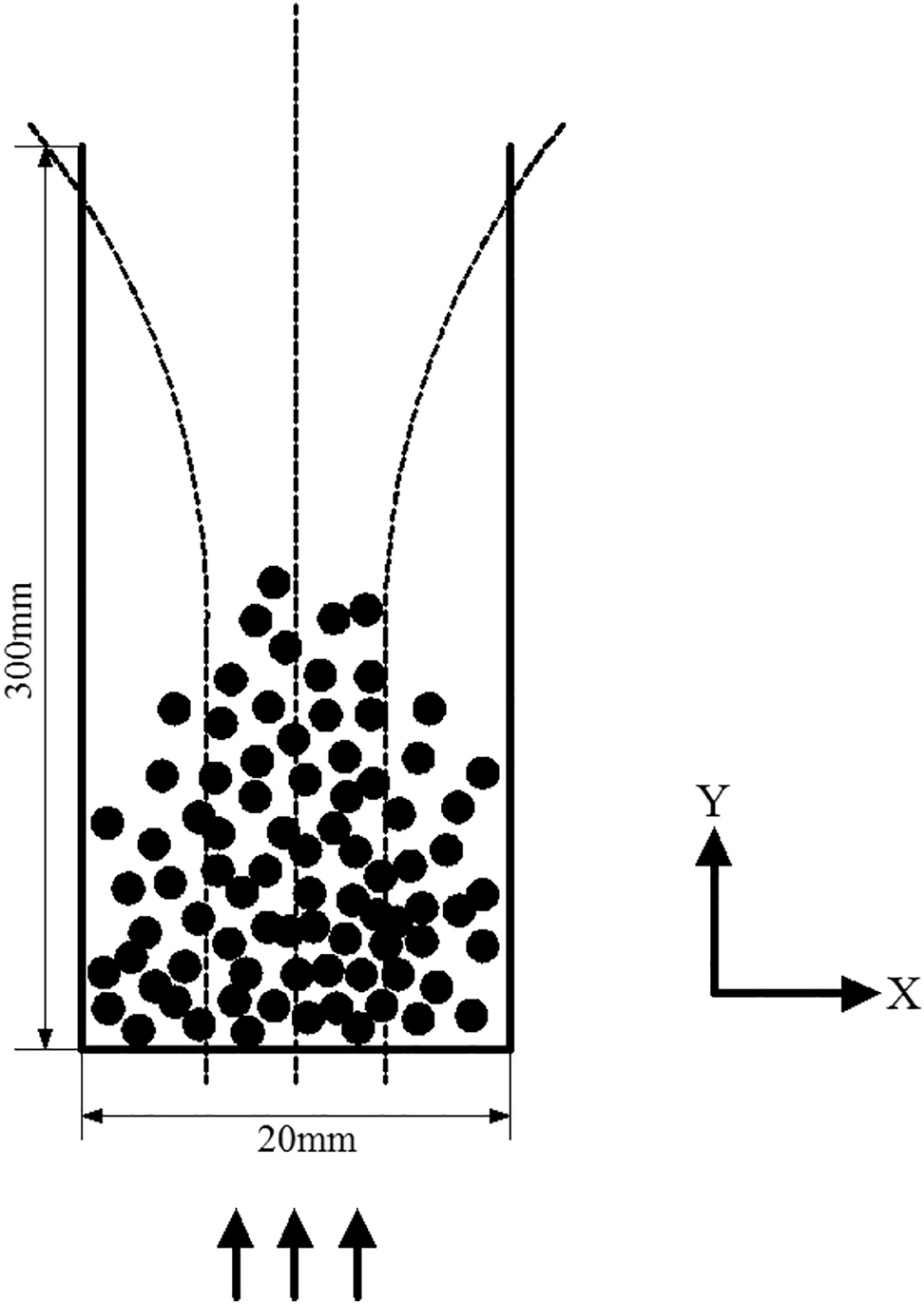

The diameter of the bottom of the cylindrical reaction vessel in the MFB is 20 mm, and the height of the cylindrical reaction vessel is 300 mm. The number of MIC particles, which are the simulation objects, is 5000, and the side profile of the 3D numerical simulation model diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Model of liquid-solid magnetic fluidized bed.

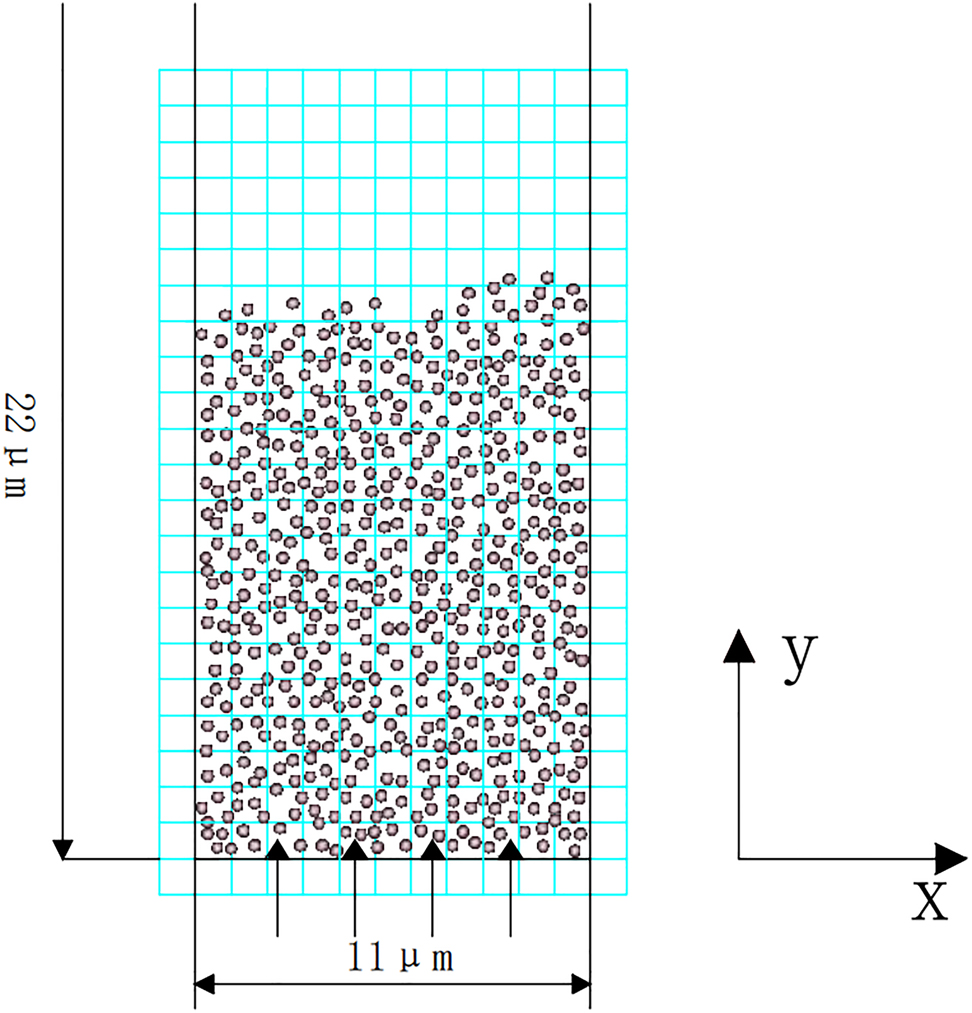

The large number of particles in the reactor exceeds the limit of computing capabilities for the current software. Therefore, 5000 magnetase particles were selected as simulation objects, and a sample 11 × 22 μm section was chosen for simulation. The simulated model of the MFB is shown in Figure 2.

Simulation model of magnetic fluidized bed with two-dimension and two-phase.

Figure 2 shows that the continuous phase is divided into multiple computational grids. Average pressure, flow velocity of continuous phase in a single grid are calculated by “staggered grid method”. The concentration of solid-phase nanomagnetic enzyme particles in the grid was calculated by “the area calculation method”. Under the action of external magnetic field, the wall of MFB can be regarded as non-magnetic wall because of the superparamagnetic properties of magnetic enzyme nanoparticles. Assuming that the nano-magnetic enzyme particles are randomly filled in the specified region, the initial velocity of the nanomagnetic enzyme particles is zero, and an inelastic collision is performed at the boundary. In the simulation, the fluid enters from the bottom of the MFB and flows upward along y axis.

2.5.2 Main parameters used in the numerical simulation of the MFB

The main parameters of the liquid–solid MFB simulation are shown in Table 1.

Main parameters of the simulation.

| Name | Simulated parameters | Name | Simulated parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bed diameter | 20 mm | Number of magnetic enzyme particulate | 5000 |

| High bed | 300 mm | Magnetic enzyme particulate density | 930 kg/m3 |

| Damping coefficient [18] | 0.05 | Mean particle diameter of magnetic enzyme particles | 138 nm |

| Magnetic permeability | 1.24 × 10−7 | Magnetic enzyme particle stiffness | 500 N/m |

| Wall stiffness | 800 N/m | Magnetic susceptibility of magnetic enzyme microparticles | 0.91 |

| Specific saturation magnetization | 26.10 ± 0.35 emu/g | Viscosity of rice bran solution | 1.3 × 10−3 Pa s |

| Sizing grid | 400 × 400 nm | Temperature of rice bran solution | 50 °C |

| Friction coefficient between particle and wall | 0.60 | Rice bran solution density | 720 kg/m3 |

| Perforated hole rate | 35% | Stack height | 2 mm |

| Iterative step | 1 × 10−5 | Friction coefficient between the particles | 0.90 |

According to the parameters in Table 1, the effects of magnetic field intensity and liquid velocity on the instantaneous state and velocity distribution of the particles are studied under the optimum magnetic field intensity.

2.5.3 Effects of enzymatic solution in a magnetic fluidized bed

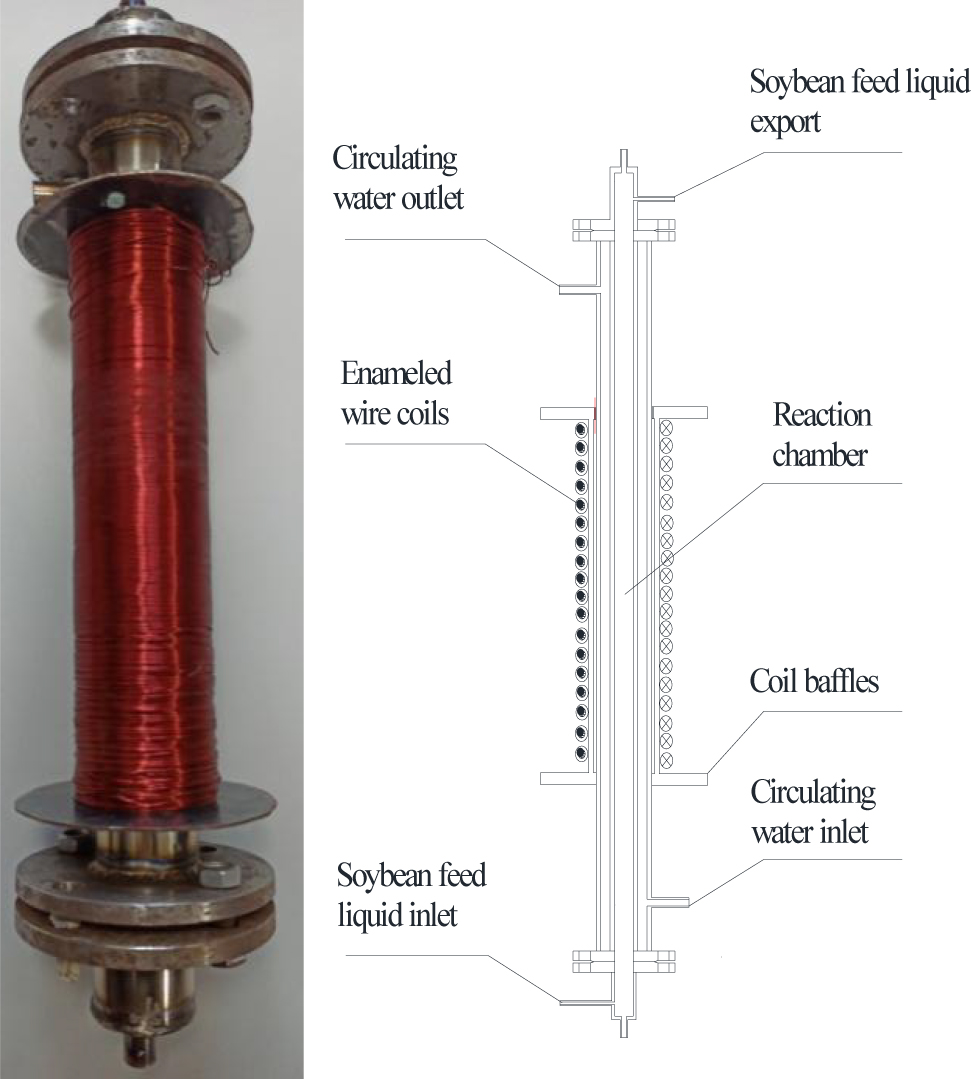

The rice bran solution was pumped from the inlet into the reaction room of the MFB at a uniform speed. Under a specified magnetic field, enzymatic hydrolysis was carried out according to conditions obtained from the single factor test. After the reaction was completed, the rice bran solution was pumped out of the reaction room through its outlet. The remaining operations were carried out in accordance with Section 2.4. After the reaction was finished, the OER was calculated according to the relevant formula. The MFB is shown in Figure 3.

Magnetic fluidized bed.

2.6 Detection of contents

2.6.1 Detection of immobilization activity

One cellulose active unit (U/g) is defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 μmol of glucose from carboxymethyl cellulose hydrolysis within 1 min at 40 °C and pH 4.6. The amount of glucose produced was measured using DNS as a reagent by observing the absorption at 540 nm. Enzyme activity was determine using the method proposed by Zang et al. [24]. The formula is as follows:

where the symbols in the equation denote the following:

E—amount of reducing sugar (mg); N—dilution multiple; T—enzymatic hydrolysis time (min); F—amount of enzyme added (ml); 180—molar amount of glucose (g/mol);60—time conversion factor.

where the symbols in the equation denote the following:

A—specific activity of magnetic enzyme; M—enzyme activity of magnetic enzyme (IU/g); F—enzyme activity of free enzyme (IU/g).

Assuming that the enzyme activity added to the enzyme solution is 100% (initial enzyme activity), the ratio of instantaneous enzyme activity to initial enzyme activity measured under different conditions is expressed as specific activity.

2.6.2 Determination of enzyme load

The enzyme loading formula was determined by Bradford [25]. The formula is expressed as follows:

where the symbols in the equation denote the following:

K 0—slope of bovine serum standard curve; V—the volume of the desired enzyme solution (ml); C 2—absorbance value of free enzyme; C 1—absorbance value of immobilized enzyme.

2.6.3 Calculation of the rice bran oil extraction rate

2.7 Data analysis

To guarantee the reliability and accuracy of the experimental data, it is necessary to ensure that there are three groups of parallel experiments. The experimental results are shown using mean values and deviations. In the study, the deviation were calculated using SPSS 22.0, and the figures were generated using Origin 7.5.

3 Results and analysis

3.1 Structural characterization of magnetic composite carrier and MIC

3.1.1 SEM analysis

Silica-coated magnetic particles were used as magnetic supports for immobilized cellulase. The relative enzyme activity of the MIC was measured to be 78.5% and the value was measured to be 148.5 mg/g. The SEM images of the magnetic supports and magnetic enzymes are shown in Figure 4, where Figure 4a shows data for Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) and Figure 4b shows data for MIC.

SEM images of a-Fe3O4/SiOx-g-P (GMA) and b-MIC.

Figure 4 shows that both have uniform morphology and particle size distribution [26]. The average particle size of the supports in Figure 4a is approximately 120 nm. It is likely that agglomeration occurs due to the directed attachment growth mechanism which leads to the minimization of the surface energy [27] and magnetic action between the particles. The average particle size of the magnetic enzymes in Figure 4b is approximately 138 nm. The size distribution is more uniform, and the agglomeration is reduced. After the immobilization of cellulase, the particle size increased, indicating that the enzyme was successfully loaded onto the supports.

3.1.2 Magnetic performance analysis

Fe3O4, Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) and MIC were analyzed using a vibrating sample magnetometer. The hysteresis regression line is shown in Figure 5.

Hysteresis regression line of Fe3O4, Fe3O4/SiOx-g-P (GMA) and MIC.

From Figure 5, it can be seen that the saturation magnetic intensities of Fe3O4, Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) and MIC were 62.57 emu/g, 39.10 emu/g and 26.10 emu/g, respectively. The hysteresis regression line presents an “S” shape that follows a closed curve indicating that the carriers and magnetic enzymes have superparamagnetic properties [13]. Due to an increase in covalent bonds and a change in environmental pH, the saturation magnetic intensity decreases slightly. Because the saturation magnetization is high and the coercivity is close to zero, immobilized cellulase can be quickly collected from the reaction system in the presence of an external magnetic field [28].

3.1.3 FTIR analysis

The correlation peaks of Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) and MIC were analyzed via infrared spectrometry, and the results are shown in Figure 6.

FT-IR of Fe3O4/SiOx-g-P (GMA) and MIC.

In Figure 6, Fe–O stretching vibration bonds appear in both Figure 6a and 6b at 585 cm−1. In Figure 6a, for APTES-modified MNPs, the narrow peak at 3623 cm−1 is related to the stretching fluctuation of OH groups on the MNPs surface. The vibrational peak at 1630 cm−1 corresponds to the flexion and extension of OH [29]. Due to the presence of Si–O stretching fluctuations, a new vibrational peak is revealed at 1053 cm−1. The peak at 3421 cm−1 results from the stretching vibration of the N–H [30]. The vibrational peak in Figure 6b at 1047 cm−1 can be explained by the stretching vibration of carboxyl C–O [31] and resembles the peak of cellulase molecules [32]. The vibrational peak at 1421 cm−1 is related to the C–N stretching of the amide Ⅲ band. These results confirm that free cellulase has been successfully immobilized on Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) nanoparticles.

3.2 Study of enzymatic solutions of MIC

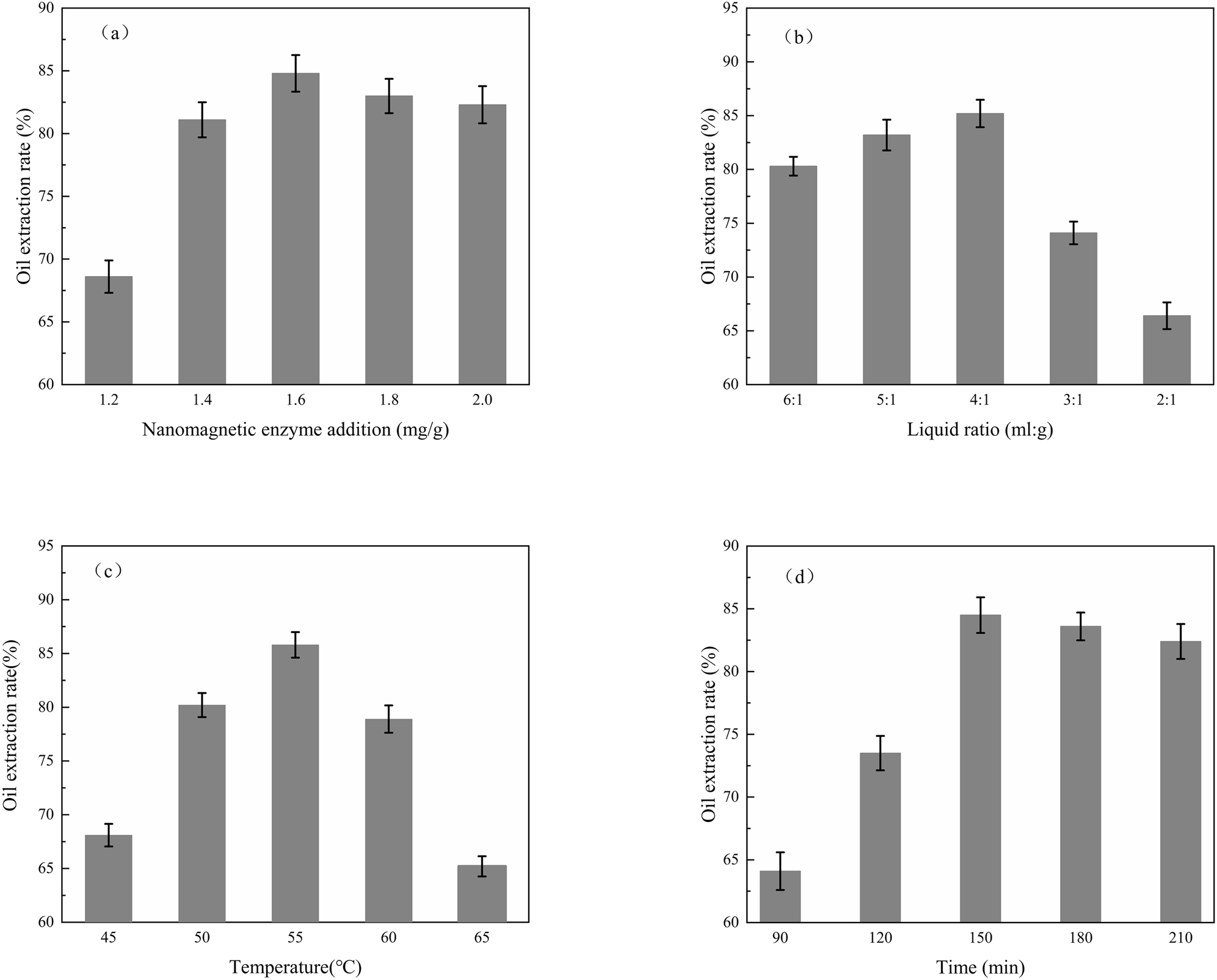

Figure 7 shows how the OER is affected by the magnetic enzyme amount, the material to liquid ratio, the enzymatic hydrolysis temperature, and the enzymatic hydrolysis time under intermittent condition. When the material to liquid ratio is 4:1 (ml:g) and the temperature is 55 °C, the change in the OER with varying amounts of magnetic enzyme over 150 min is shown in Figure 7a. When the amount of magnetic enzyme is 1.6 mg/g and the temperature is 55 °C, the change in the OER with varying the material to liquid ratio over 150 min is shown in Figure 7b. When the amount of magnetic enzyme is 1.6 mg/g and the material to liquid ratio is 4:1 (ml:g), the change in OER variation with varying enzymatic hydrolysis temperature over 150 min is shown in Figure 7c. Figure 7d shows the change in the OER with varying enzymatic hydrolysis time at 55 °C with 1.6 mg/g of magnetic enzyme and the material to liquid ratio of 4:1 (ml:g).

(a) Effect of magnetic enzyme addition on OER, (b) effect of liquid-material ratio on OER, (c) effect of reaction temperature on OER, (d) effect of reaction time on OER.

Figure 7a shows that the OER trendline begins with a steady rise and then remains nearly constant in the range of 1.2–2.0 mg/g. When 1.6 mg/g of magnetic enzyme was added, the OER became 84.8%. When the amount of added MIC increased from 1.2 mg/g to 1.6 mg/g, the oil extraction rate increased significantly. At this time, due to the degradation of the MIC, cellulose and related components were destroyed. When the amount of magnetic enzyme was greater than 1.6 mg/g, there was no more substrate to act on, resulting in wasted enzyme. Considering the above, the amount of magnetic enzyme was chosen to be 1.6 mg/g.

As shown in Figure 7b, when the liquid to material ratio was 4:1 (ml:g), the OER was at its maximum value of 85.2%. When the water content is too low, a thick suspension is formed, and the added magnetic enzyme has difficulty contacting the cell wall of the rice bran and cannot participate in enzymatic hydrolysis. In contrast, adding too much water can reduce the enzyme and the sample concentrations, which makes it difficult for enzymes to make contact with substrates. The contact time may also become too short, resulting in a reducing in extraction efficiency. Therefore, the optimal liquid to material ratio was chosen to be 4:1 (ml:g) for the follow-up study.

Figure 7c shows that when the reaction temperature is 55 °C, the OER reaches a maximum value of 85.8%. At 45–55 °C, the OER increases accordingly because the conditions approach the optimal reaction temperature. When the temperature of the reaction system exceeds 55 °C, the secondary and tertiary conformations of cellulase are destroyed due to the high temperature. The hydrophobic group is oriented inward and then outward into an exposed state, and the mutuality and dispersion of protein molecules decrease [33]. Protein denaturation occurs, resulting in a decrease in the OER. Therefore, a reaction temperature of 55 °C was chosen for the follow-up study.

Figure 7d shows that when the reaction time is set at 150 min, the OER reaches the maximum value of 84.5%. Between 90 and 150 min, due to sufficient substrate concentration, magnetic enzymes can fully contact the material so that the material releases more grease conjugates. When the reaction time is increased to longer than 150 min, the oil release system reaches a dynamic balance. Continuing to increase the reaction time does not improve the oil extraction efficiency, so there would be a wasted experimental cost. Therefore, the reaction time was set at 150 min for the follow-up study.

3.3 Numerical simulation of MIC in a MFB

3.3.1 Effect of magnetic field intensity on instantaneous distribution of MIC

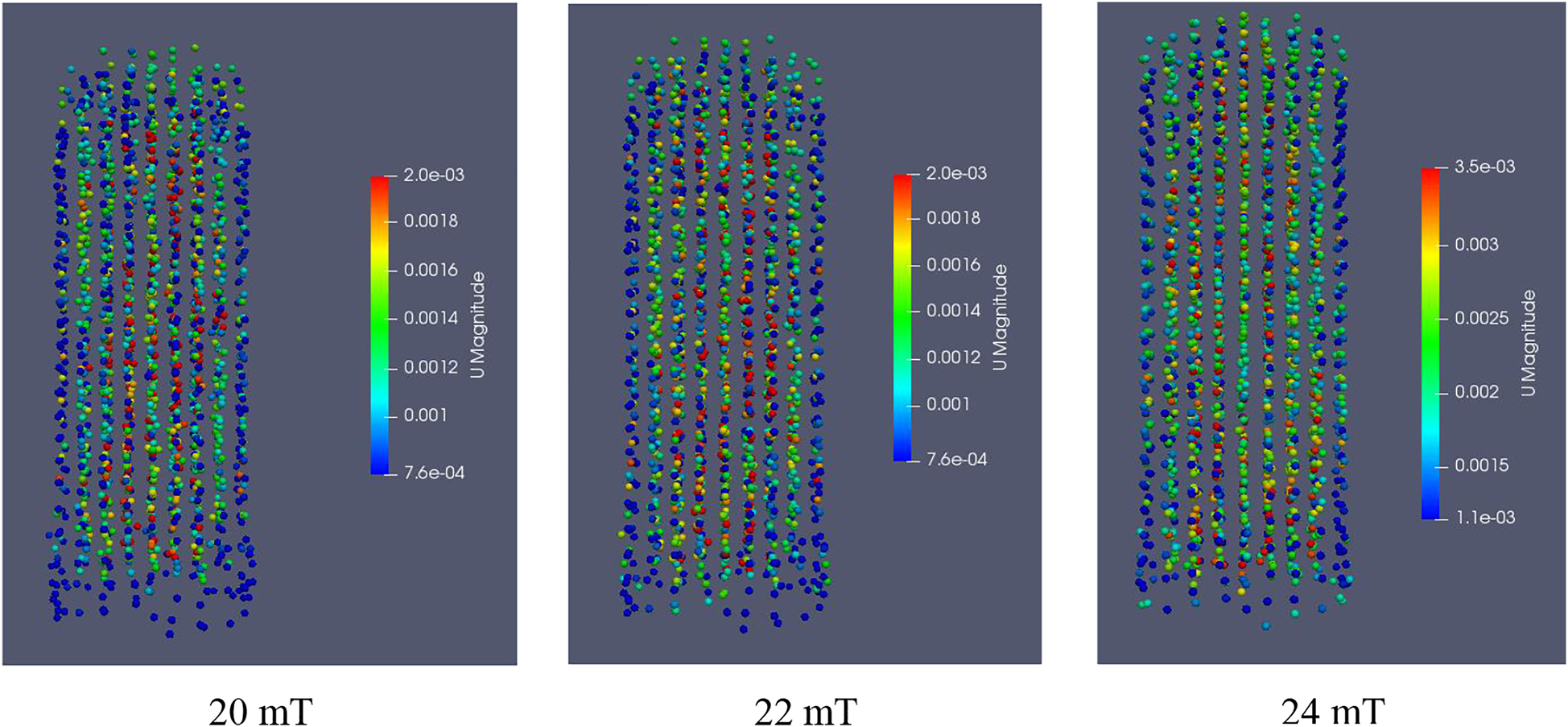

At a flow velocity of 0.005 m/s, the effect of magnetic field intensity on the instantaneous distribution of MIC particles is shown in Figure 8.

Instantaneous distribution of magnetic enzyme particle movement under different magnetic field intensities.

Figure 8 shows that the MIC particles in the MFB change from a chaotic state to an orderly arrangement. When the magnetic field intensity is 20 mT, the magnetic particles are mainly affected by gravity, magnetic force and resistance. Because the magnetic field is weak, the two nonmagnetic forces dominate, and the particles exist in a mostly chaotic state. As the magnetic field intensity increases to 22 mT, the appropriate magnetic field intensity increases the active space of the magnetic particles, and the MFB changes from partial stabilization to magnetic stabilization [34]. The length of the magnetic chain are related to the strength of the magnetic field, and when the liquid flows upward, it carries the magnetic particles upward and forms numerous “short chains” that are conducive to the fluidization state of the magnetic particles. Thus, the reaction in the liquid-solid MFB becomes more efficient. When the magnetic force reaches 24 mT, the MFB becomes a “frozen” magnetic bed. Since the magnetic force is large enough to exert complete controls over the magnetic particles in the bed, more magnetic particles are bound together [23]. At this point, the MFB cannot provide a sufficient contact interface between the MIC and rice bran solution. The enzymatic hydrolysis of magnetic particles is reduced, so this is not conducive to the reaction. Considering the above, the magnetic field intensity is set at 22 mT.

3.3.2 Effect of magnetic field intensity on velocity profiles of MIC

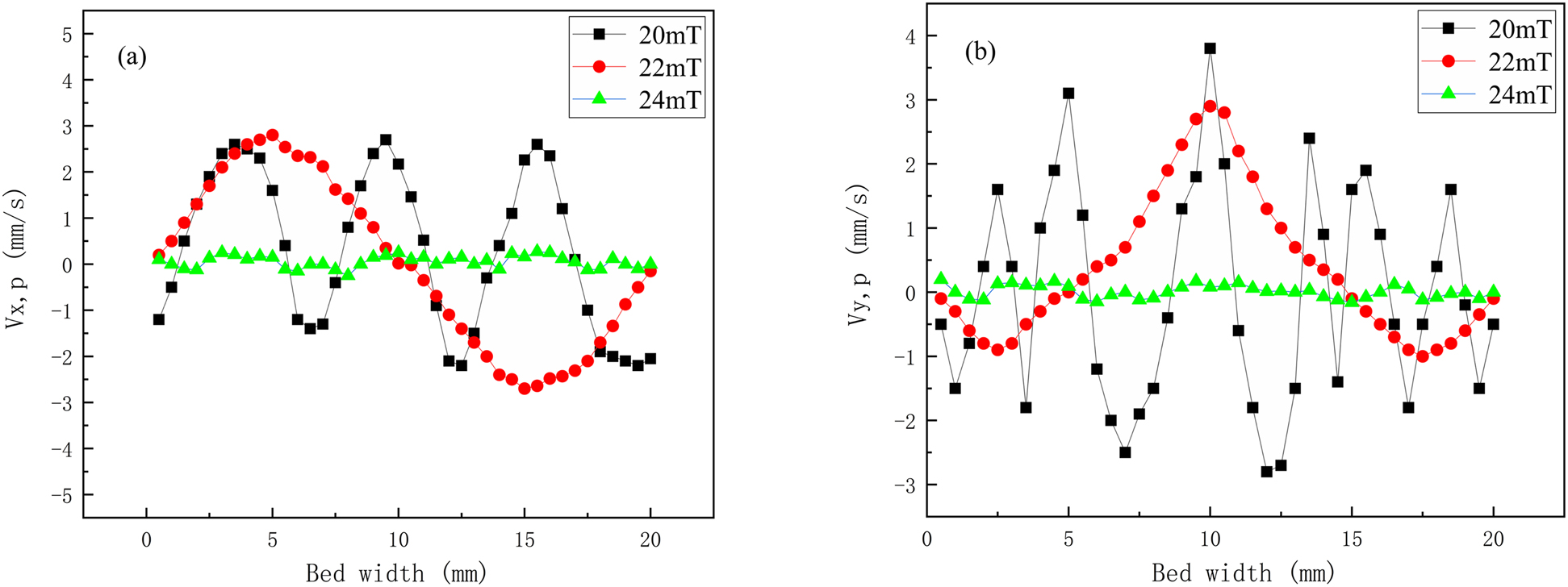

When the rice bran solution flow velocity is equal to 0.005 m/s, the effect of the magnetic field intensity on the speed of MIC particles is shown in Figure 9.

Velocity diagram of magnetic enzyme particles under different magnetic field strengths.

Figure 9 shows that the velocities of MIC particles are limited to a certain region under different magnetic field intensities [35]. When the liquid flow velocity is 0.005 m/s and B 0 = 20 mT, the axial velocities and radial velocities in the MFB are irregular, and the rice bran solution moves together with the magnetic particles, indicating that the magnetic particles move freely in the MFB. When B 0 = 22 mT, the axial velocities carry particles upward at the center of the sample, while the magnetic particles move downward near the left and right boundaries. Due to the radial velocities, the magnetic particles at the left and right boundaries of the fluidized bed move in opposite directions; namely, the particles near the left boundary move rightward, and vice versa, resulting in a state of circular circulation. With an increase in magnetic field intensity to B 0 = 24 mT, the axial velocities and radial velocities of the magnetic particles both approach zero, leading to a “frozen bed” state and resulting in the binding of magnetic particles that is not conducive to a fluidized state. A magnetic field intensity of 22 mT is chosen.

3.3.3 Effect of the solution flow velocity on transient distribution of MIC

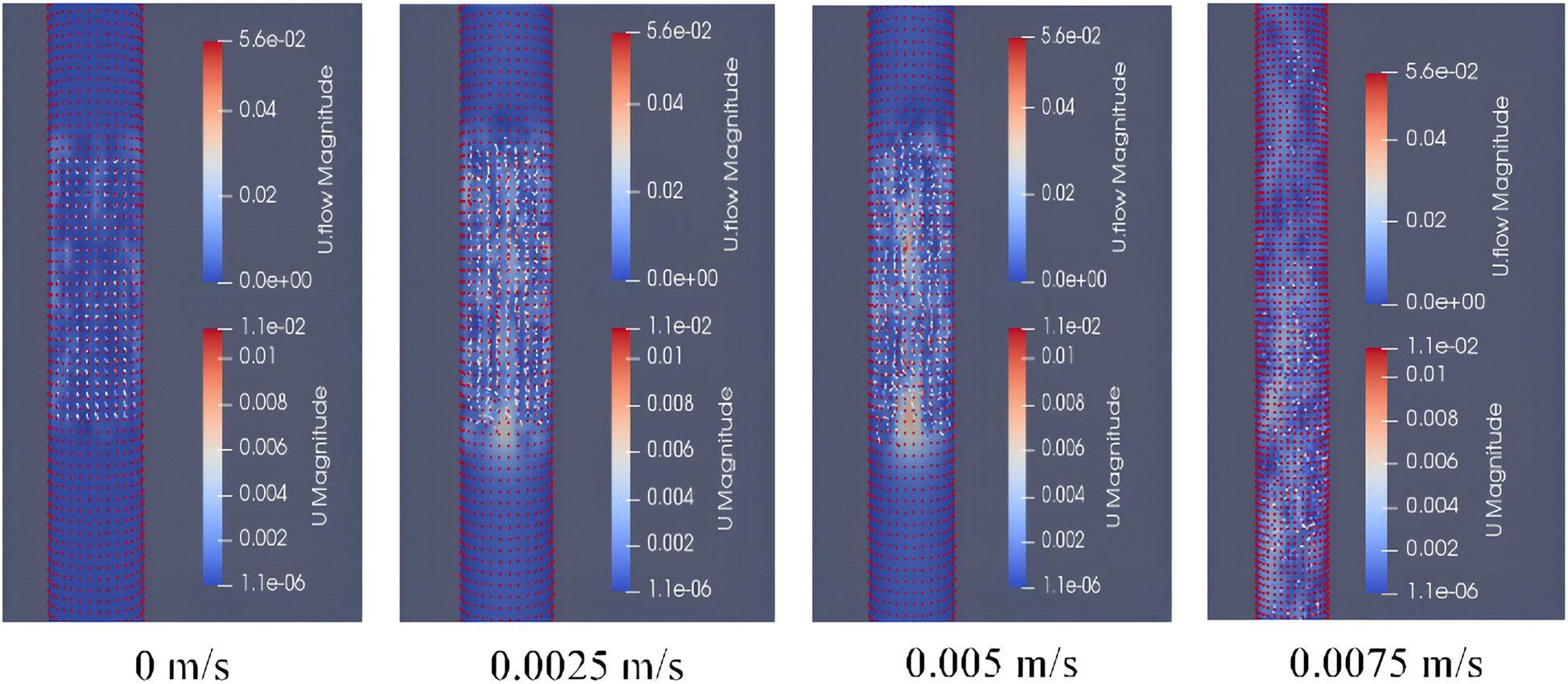

For an applied magnetic field intensity of 22 mT, the effect of the rice bran solution flow velocity on the instantaneous distribution of MIC particles is shown in Figure 10.

Instantaneous distribution of magnetic enzyme particles at different rice bran solution flow velocitys.

As shown in Figure 10, when the liquid flow velocity is 0 m/s, the magnetic particles are suspended in the MFB despite the force of gravity due to the counteracting effect of the large external magnetic force. When the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is in the range 0.0025–0.0075 m/s, the increase in the rice bran solution velocity increases the collision probability of the magnetic particles in the MFB, which leads to an increase in the average cyclic motion [36]. When the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is 0.0025 m/s, the flow velocity is small, and the force on the magnetic particles is too weak to drive the magnetic particles into a fluidized state. When the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is 0.005 m/s, the liquid flow velocity is moderate, and the magnetic particles are driven upward to reach the optimal fluidized state. When the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is 0.0075 m/s, the high flow velocity disperses the optimal fluidization state of the magnetic particles, and leads to the overflow of some magnetic particles from the outlet at the upper end of the MFB [37]. This results in wasted magnetic enzymes and reduced reaction efficiency. Considering the above, the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is chosen to be 0.005 m/s.

3.3.4 Effect of the solution flow velocity on the velocities of MIC

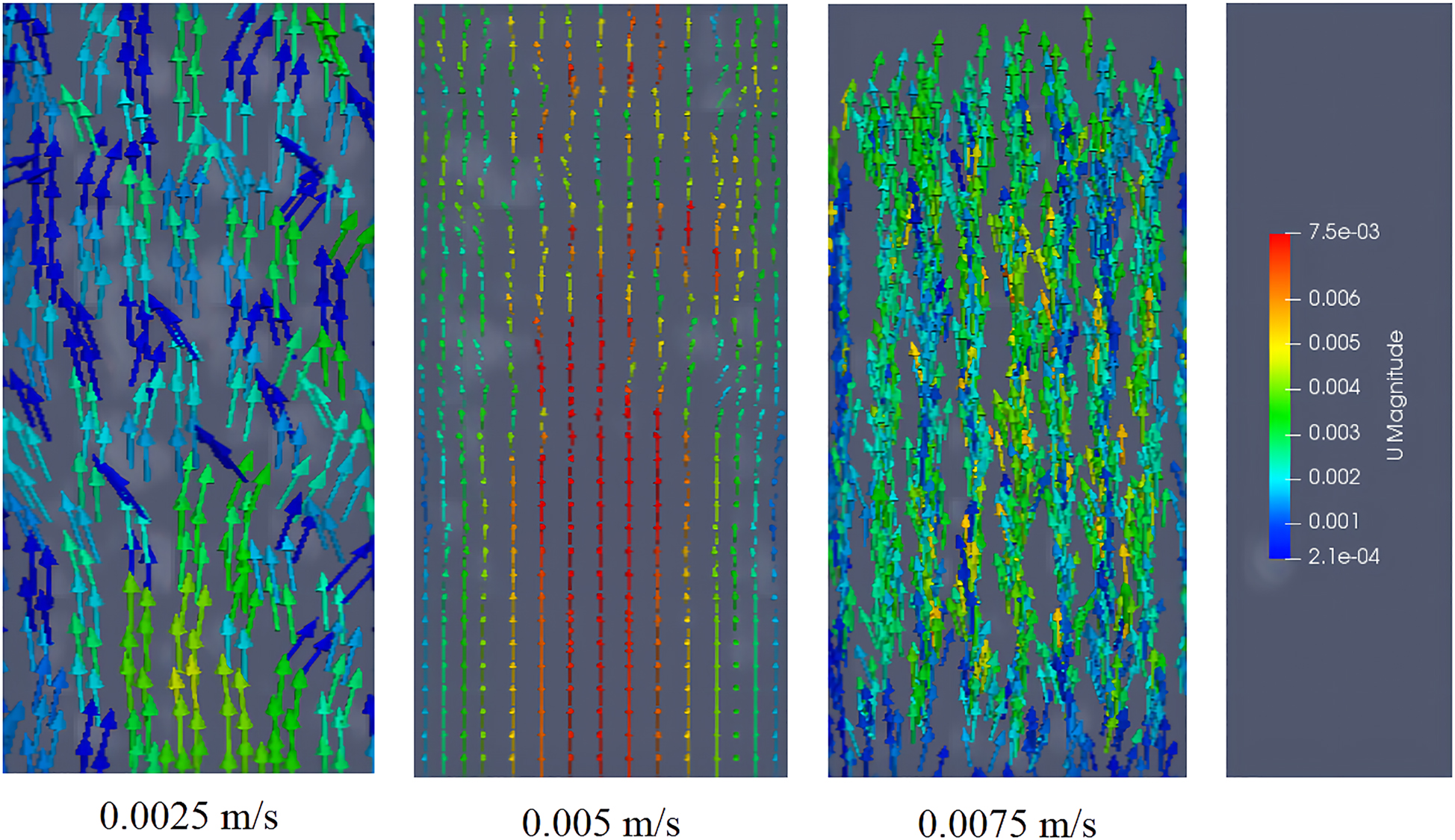

For an applied magnetic field intensity of 22 mT, the effect of the rice bran solution flow velocity on the speed of MIC particles is shown in Figure 11. The direction of the arrows indicate the velocity direction of the magnetic particles, while the colors of the arrow represent the speed.

Velocity diagram of magnetic enzyme particles at different rice bran solution flow velocitys.

As shown in Figure 11, when the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is 0.0025 m/s, the majority of the magnetic particles move upward due to the action of the liquid, while some magnetic particles move downward due to gravity, so the motion in the entire bed is chaotic. When the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is 0.005 m/s, the magnetic enzymes in the entire bed have a clear motional state, with the magnetic particles in the middle moving upward via the resistance of the liquid and the magnetic particles on the sides of the bed responding to various forces producing circular circulation, and the fluidization state is good. When the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is 0.0075 m/s, the magnetic particles in the entire bed move upward. Because, the rice bran solution has a large resistance, the magnetic particles move from the bottom of the MFB to the top, destroying the formation of “short chains” and resulting in some magnetic enzymes flowing out of the upper outlet. Accordingly, the flow velocity of the rice bran solution is chosen to be 0.005 m/s.

3.4 Comparison of hydrolysis of MIC under intermittent conditions and in a MFB

Under the identical process conditions, the effects of intermittent conditions and a MFB on the OER are compared, as shown in Table 2.

Comparison of relevant indicators in intermittent conditions and magnetic fluidized beds.

| Target | Intermittent conditions | Magnetic fluidized bed |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme addition (mg/g) | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Liquid ratio (ml:g) | 4:1 | 4:1 |

| Reaction temperature (°C) | 55 | 55 |

| Reaction time (min) | 150 | 150 |

| OER (%) | 85.6 ± 1.2 | 90.3 ± 1.5 |

Under intermittent conditions, oil extraction needs continuous stirring to make the enzyme fully contact with rice bran. However, while stirring, the mechanical force and the heat generated will change the morphology and structure of the MIC, resulting in reduced enzyme reusability and enzyme activity.

No magnetic particles were detected at the outlet of the MFB. Under the appropriate uniform magnetic field and the appropriate flow rate of rice bran solution, MIC showed uniform circulation flow. The circulation flow process was the process of magnetic enzyme reuse, which reduced the loss caused by MIC separation and improved the efficiency of oil extraction. According to Table 2, under identical reaction conditions, the OER was large in the fluidized bed by 4.7% when compared to batch reactions; this indicates that the MFB can improve the OER via the AEE method and provide a theoretical basis for the application of the AEE method to the industrial production of RBO.

4 Conclusions

In this paper, free cellulase was immobilized on a magnetic supporter to prepare an MIC. The MIC has a magnetic response with coercivity that is close to zero, indicating that it is superparamagnetic and can be applied to MFB. The MIC, when combined with magnetic immobilized alkaline protease, was capable of extracting RBO from fresh rice bran with an optimal OER of 85.6% under intermittent conditions. In numerical simulations, application of the MIC to MFB, with a magnetic field intensity of 22 mT and the liquid velocity of 0.005 m/s showed optimal solid-liquid two-phase fluidization. Under optimized enzymatic hydrolysis conditions, the OER using a continuous AEE was increased by 4.7% compared with that under intermittent conditions. This shows that the application of MIC in the MFB can improve the reaction efficiency as well as provide a theoretical basis for the extraction of RBO for future studies using the industrial continuous chemical hydrase method. This paper also needs to study the following aspects: continue to search for chemical reagents with a smaller impact on enzyme activity, improve the relative enzyme vitality of MIC, and reduce the production costs for regenerating Fe3O4/SiO x -g-P (GMA) immobilization enzymes in order to increase the use cycle of magnetically immobilized enzyme. From the perspective of industrial production, there is still the problem of the long enzyme solution reaction time. We should improve the height of the reaction room, reduce its pipeline length, and further improve the pilot application of the three-phase MFB to provide more practical theoretical parameters for the realization of industrial production.

Funding source: Integration and demonstration of key technologies for soybean bio-based oil and protein products

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2020ZX08B01

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province: Mechanism of enzymatic degumming process of soybean oil characterized by electrochemical biosensor (No: LH2020C061).

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

1. Katsri, K, Noitup, P, Junsangsree, P, Singanusong, R. Physical, chemical and microbiological properties of mixed hydrogenated palm kernel oil and cold-pressed rice bran oil as ingredients in non-dairy creamer. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol 2014;36:73–81.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Rudzinska, M, Hassanein, M, Adel, G, Ratusz, K, Siger, A. Blends of rapeseed oil with black cumin and rice bran oils for increasing the oxidative stability. J Food Sci Technol-Mysore 2016;53:1055–62.10.1007/s13197-015-2140-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Follegatti-Romero, LA, Piantino, CR, Grimaldi, R, Cabral, FA. Supercritical CO2 extraction of omega-3 rich oil from Sacha inchi (Plukenetia volubilis L.) seeds. J Supercrit Fluids 2009;49:323–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2009.03.010.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Amit, RA, Bikash Mohanty, B, Ravindra Bhargava, B. Modeling and response surface analysis of supercritical extraction of watermelon seed oil using carbon dioxide. Separ Purif Technol 20152015;141:354–65.10.1016/j.seppur.2014.12.016Suche in Google Scholar

5. Jiao, J, Li, Z, Gai, Q, Li, X, Wei, F, Fu, Y, et al.. Microwave-assisted aqueous enzymatic extraction of oil from pumpkin seeds and evaluation of its physicochemical properties, fatty acid compositions and antioxidant activities. Food Chem 2014;147:17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.079.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Peng, L, Ye, Q, Liu, X, Liu, S, Meng, X. Optimization of aqueous enzymatic method for Camellia sinensis oil extraction and reuse of enzymes in the process. J Biosci Bioeng 2019;128:716–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2019.05.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Wang, Y, Wang, Z, Cheng, S, Han, F. Aqueous enzymatic extraction of oil and protein hydrolysates from peanut. Japanese Soc Food Sci Technol 2008;14:533–40. https://doi.org/10.3136/fstr.14.533.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Latif, S, Anwar, F. Aqueous enzymatic sesame oil and protein extraction. Food Chem 2010;125:679–84.10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.064Suche in Google Scholar

9. Li, F, Yang, L, Zhao, T, Zhao, J, Zou, Y, Zou, Y, et al.. Optimization of enzymatic pretreatment for n-hexane extraction of oil from Silybum marianum seeds using response surface methodology. Food Bioprod Process 2012;90:87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbp.2011.02.010.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Gao, J, Lu, C, Wang, Y, Wang, S, Shen, J, Zhang, J, et al.. Rapid immobilization of cellulase onto graphene oxide with a hydrophobic spacer. Catalysts 2018;8:180. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8050180.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Bohara, R, Thorat, N, Pawar, S. Immobilization of cellulase on functionalized cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. Kor J Chem Eng 2016;33:216–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-015-0120-0.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Zhou, G, Chen, G, Yan, B. Biodiesel production in a magnetically-stabilized, fluidized bed reactor with an immobilized lipase in magnetic chitosan microspheres. Biotechnol Lett 2014;36:63–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10529-013-1336-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Yu, D, Ma, Y, Xue, S, Jiang, L, Shi, J. Characterization of immobilized phospholipase A1 on magnetic nanoparticles for oil degumming application. LWT-Food Sci Technol (Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft-Technol) 2013;50:519–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2012.08.014.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Jovanovic, G, Atwater, J, Znidarsic-Plazl, P, Piazl, I. Dechlorination of polychlorinated phenols on bimetallic Pd/Fe catalyst in a magnetically stabilized fluidized bed. Chem Eng J 2015;274:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2015.03.087.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Chen, G, Liu, J, Yao, J, Qi, Y, Yan, B. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil in a magnetically fluidized bed reactor using whole-cell biocatalysts. Energy Convers Manag 2017;138:556–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.02.036.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Xu, Y, Zhou, M, Hu, J, Xu, Y, Luo, G, Li, X, et al.. Particulate matter filtration of the flue gas from iron-ore sintering operations using a magnetically stabilized fluidized bed. Powder Technol 2019;342:335–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2018.09.095.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Zhou, Z, Lin, T, Jing, G, Lv, B, Liu, Y. High-efficiency removal of NOx by a novel integrated chemical absorption and two-stage bioreduction process using magnetically stabilized fluidized bed reactors. Sci China 2015;58:1621–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11426-015-5413-y.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Yue, Y, Chen, K, Liu, J, Yu, B, Jiang, L, Yu, D, et al.. Numerical simulation and deacidification of nanomagnetic enzyme conjugate in a liquid–solid magnetic fluidized bed. Process Biochem 2020;90:32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2019.10.035.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Ramezanizadeh, M, Nazari, MA, Ahmadi, MH, Chau, KW. Experimental and numerical analysis of a nanofluidic thermosyphon heat exchanger. Eng Appl Comput Fluid Mech 2019;13:40–7.10.1080/19942060.2018.1518272Suche in Google Scholar

20. Zhao, T, Ding, X, Wang, Z, Zhang, Y, Liu, K. Dynamic control method of particle distribution uniformity in the rolling circulating fluidized bed (RCFB). Eng Appl Comput Fluid Mech 2021;15:210–21.10.1080/19942060.2020.1871417Suche in Google Scholar

21. Ez Abadi, AM, Sadi, M, Farzaneh-Gord, M, Ahmadi, MH, Kumar, R, Chau, KW. A numerical and experimental study on the energy efficiency of a regenerative heat and mass exchanger utilizing the counter-flow Maisotsenko cycle. Eng Appl Comput Fluid Mech 2020;14:1–12.10.1080/19942060.2019.1617193Suche in Google Scholar

22. Lei, L, Liu, X, Li, Y, Cui, Y, Yang, Y, Qin, G. Study on synthesis of poly(GMA)-grafted Fe3O4/SiOX magnetic nanoparticles using atom transfer radical polymerization and their application for lipase immobilization. Mater Chem Phys 2011;125:866–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2010.09.031.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Wang, S, Shen, Y, Ma, Y, Gao, J, Lan, X, Dong, Q, et al.. Study of hydrodynamic characteristics of particles in liquid–solid fluidized bed with uniform transverse magnetic field. Powder Technol 2013;245:314–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2013.04.049.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Zang, L, Qiu, J, Wu, X, Zhang, W, Sakai, E, Wei, Y. Preparation of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles as support for cellulase immobilization. Ind Eng Chem Res 2014;53:3448–54. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie404072s.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Bradford, M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 1976;72:248–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Ashjari, M, Garmroodi, M, Amiri, F, Emampour, M, Yousefi, M, Lish, M, et al.. Application of multi-component reaction for covalent immobilization of two lipases on aldehyde-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles; production of biodiesel from waste cooking oil. Process Biochem 2019;90:156–67.10.1016/j.procbio.2019.11.002Suche in Google Scholar

27. Bohara, RA, Yadav, HM, Thorat, ND, Mali, SS, Hong, CK, Nanaware, SG, et al.. Synthesis of functionalized Co0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 nanoparticles for biomedical applications. J Magn Magn Mater 2015;378:397–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2014.11.063.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Hajar, M, Vahabzadeh, F. Biolubricant production from castor oil in a magnetically stabilized fluidized bed reactor using lipase immobilized on Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Ind Crop Prod 2016;94:544–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.09.030.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Cheng, G, Xing, J, Pi, Z, Liu, S, Liu, Z, Song, F. α-Glucosidase immobilization on functionalized Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles for screening of enzyme inhibitors. Chin Chem Lett 2019;30:656–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2018.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Lin, Y, Liu, X, Xing, Z, Geng, Y, Wilson, J, Wu, D, et al.. Preparation and characterization of magnetic Fe3O4–chitosan nanoparticles for cellulase immobilization. Cellulose 2017;24:5541–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-017-1520-6.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Zhang, Q, Kang, J, Yang, B, Zhao, L, Hou, Z, Tang, B. Immobilized cellulase on Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a magnetically recoverable biocatalyst for the decomposition of corncob. Chin J Catal 2016;37:389–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1872-2067(15)61028-2.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Abraham, RE, Verma, ML, Barrow, CJ, Puri, M. Suitability of magnetic nanoparticle immobilised cellulases in enhancing enzymatic saccharification of pretreated hemp biomass. Biotechnol Biofuels 2014;7:90. https://doi.org/10.1186/1754-6834-7-90.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

33. Jiang, L, Hua, D, Wang, Z, Xu, S. Aqueous enzymatic extraction of peanut oil and protein hydrolysates. Food Bioprod Process 2010;88:233–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbp.2009.08.002.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Wang, S, Sun, Z, Li, X, Gao, J, Lan, X, Dong, Q. Simulation of flow behavior of particles in liquid–solid fluidized bed with uniform magnetic field. Powder Technol 2013;237:314–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2012.12.013.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Wang, S, Sun, J, Yang, Q, Zhao, Y, Gao, J, Liu, Y. Numerical simulation of flow behavior of particles in an inverse liquid–solid fluidized bed. Powder Technol 2014;261:14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2014.04.017.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Wang, S, Guo, S, Gao, J, Lan, X, Dong, Q, Li, X. Simulation of flow behavior of liquid and particles in a liquid–solid fluidized bed. Powder Technol 2012;224:365–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2012.03.022.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Wang, S, Wang, X, Wang, R, Zhao, J, Yang, S, Liu, Y, et al.. Simulations of flow behavior of particles in a liquid-solid fluidized bed using a second-order moments model. Powder Technol 2016;302:21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2016.08.019.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/ijfe-2021-0111).

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Critical Review

- Artificial intelligence, big data, and blockchain in food safety

- Articles

- Immobilization of cellulase on magnetic nanoparticles for rice bran oil extraction in a magnetic fluidized bed

- Utilization of shallot bio-waste (Allium cepa L. var. aggregatum) fractions for the production of functional cookies

- Effect of bacterial cellulose nanofibers incorporation on acid-induced casein gels: microstructures and rheological properties

- Effect of microencapsulated chavil (Ferulago angulata) extract on physicochemical, microbiological, textural and sensorial properties of UF-feta-type cheese during storage time

- Evaluation of thickened liquid viscoelasticity for a swallowing process using an inclined flow channel instrument

- Comparative flavor analysis of four kinds of sweet fermented grains by sensory analysis combined with GC-MS

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Critical Review

- Artificial intelligence, big data, and blockchain in food safety

- Articles

- Immobilization of cellulase on magnetic nanoparticles for rice bran oil extraction in a magnetic fluidized bed

- Utilization of shallot bio-waste (Allium cepa L. var. aggregatum) fractions for the production of functional cookies

- Effect of bacterial cellulose nanofibers incorporation on acid-induced casein gels: microstructures and rheological properties

- Effect of microencapsulated chavil (Ferulago angulata) extract on physicochemical, microbiological, textural and sensorial properties of UF-feta-type cheese during storage time

- Evaluation of thickened liquid viscoelasticity for a swallowing process using an inclined flow channel instrument

- Comparative flavor analysis of four kinds of sweet fermented grains by sensory analysis combined with GC-MS