Abstract:

We present a general statistical modelling framework for handling multivariate mixed types of outcomes in the context of quantitative genetic analysis. The models are based on the multivariate covariance generalized linear models, where the matrix linear predictor is composed of an identity matrix combined with a relatedness matrix defined by a pedigree, representing the environmental and genetic components, respectively. We also propose a new index of heritability for non-Gaussian data. A case study on house sparrow (Passer domesticus) population with continuous, binomial and count outcomes is employed to motivate the new model. Simulation of multivariate marginal models is not trivial, thus we adapt the NORTA (Normal to anything) algorithm for simulation of multivariate covariance generalized linear models in the context of genetic data analysis. A simulation study is presented to assess the asymptotic properties of the estimating function estimators for the correlation between outcomes and the new heritability index parameters. The data set and R code are available in the supplementary material.

1 Introduction

Linear mixed effects models [1, 2] are the main statistical tool in the context of quantitative genetic data analysis. The estimation of the additive genetic variance and thus the heritability of different outcomes is one of the main goals in quantitative genetic [3, 4]. Examples appear frequently in evolutionary biology [5] and animal breeding [6]. Although flexible for Gaussian data, linear mixed effects models are unsuitable for analysing binary, binomial, count and asymmetric continuous outcomes.

For the analysis of non-Gaussian outcomes the generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) framework is a frequent choice [7, 8]. GLMMs consist of specifying a generalized linear model conditionally on a multivariate latent distribution, often the multivariate Gaussian. In general GLMMs are computationally demanding and many different algorithms have been proposed in the past three decades, see [9] and [10] for additional references. A further aspect of GLMMs that gives rise to concern is the general lack of a closed-form expression for the likelihood and the marginal distribution of the data vector. A related question is the special interpretation of parameters inherent from the construction of GLMMs. Thus, the covariate effects are conditional on the latent variables, whereas the correlation structure is marginal for the latent variables rather than for the outcomes.

The literature to deal with mixed types of outcomes in the context of quantitative genetic is sparse. [7, 11] proposed to use the GLMMs family relying on MCMC (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) methods for estimation in the Bayesian framework. MCMC methods for GLMMs are challenging in terms of convergence and computational time. Furthermore, these challenges seem to be amplified for mixed types of outcomes and covariance modelling using genetic structures. Moreover, the implementation itself can be difficult, especially for end-users who might not be expert in programming. For a more comprehensive discussion on the computational challenges for MCMC methods, we refer the interested reader to [12] and [10]. [13] presented the penalized multivariate linear mixed model for the analysis of multi-traits in the context of genome-wide association studies. For a recent application of this approach and further discussion about mixed types of outcomes, see [14].

The computation of the heritability index in the Gaussian case is trivially defined by the proportion of the variance attributed to the genetic component. For non-Gaussian data, it is not immediately obvious how to define the heritability of an outcome. A comprehensive discussion about the computation of the heritability index for non-Gaussian data based on GLMMs is presented in [15] along with a proposal of solution. Although, this new development on the computing of the heritability index for non-Gaussian data, it remains a daunting task requiring intricate calculation involving multivariate integrals and specific algorithms.

In this paper, we present an alternative approach for modelling mixed types of outcomes in the context of genetic data based on the multivariate covariance generalized linear models (McGLMs) [16].

In the McGLM framework the marginal covariance matrix is explicitly modelled combining a matrix linear predictor and a covariance link function. Variance function are employed to take into account non-normality and the mean structure is modelled using a link function and a linear predictor. McGLMs are fitted using quasi-likelihood and Pearson estimating functions, based on second-moment assumptions, and implemented in an efficient Newton scoring algorithm. McGLMs are an extension of the linear mixed effects models to deal with multivariate non-Gaussian data and have the last one as a special case. Furthermore, from the marginal specification of McGLMs emerges a marginal measure of heritability for non-Gaussian data.

McGLMs have many in common with GEE (Generalized Estimating Equations) models popular in the analysis of longitudinal data [17]. However, McGLMs were explicitly designed to deal with multiple outcomes and allow for a flexible and interpretable specification of the marginal covariance structure using a covariance link function combined with a linear combination of known matrices. Furthermore, in the McGLM framework the dispersion parameters play an important role in terms of model specification and interpretation. On the other hand, current GEE implementations deal only with one outcome and include a short list of pre-specified covariance structures, such as auto-regression and compound symmetry [18, 19]. In general in the GEE framework the dispersion parameters are considered as nuisance. In terms of fitting algorithm, both methodologies use the quasi-score function for estimation of the regression coefficients. In the McGLM framework the dispersion parameters are estimated using the Pearson estimating function [20], while in the GEE context the method of moments and the GEE2 are frequent choices [21, 22].

The model we shall present in Section 3 is motivated by the data set analysed in [8] consisting of a natural meta population of house sparrow (Passer domesticus) on six islands off the coast of Helgeland, Northern Norway. In this study blood samples were used to determine genetic parenthood, and the genetic pedigree for the birds could be established. The outcomes of interest are: (1) bill depth, (2) breeding season success, and (3) average reproductive intensity. The main biological goals are to compute the heritability of the different outcomes, as well as the possible correlation between outcomes that can be due to genetic and environment effects. This example is particularly interesting because the outcomes are of mixed types, i.e. bill depth is a continuous outcome, while breeding season success and average reproductive intensity are examples of binomial and count outcomes.

In view of the recent developments in the McGLMs framework the main contributions of this article are: (i) introducing a suitable specification of the McGLMs to deal with mixed types of outcomes in the context of genetic data analysis. (ii) presenting the extended binomial variance function for handling binomial and restricted outcomes. (iii) proposing a new marginal measure of heritability for non-Gaussian data. (iv) presenting a comparison between the conditional specification of GLMMs and the marginal specification of McGLMs to explain why negative heritability index can appear in practical data analysis and how to use this fact to easily assess the significance of the genetic effects. (v) adapting the NORTA (Normal to anything) [23] algorithm for simulation of McGLMs. (vi) presenting a simulation study to check the asymptotic properties of the estimating function estimators with emphasis to the correlation between outcomes and the new measure of heritability and (vii) analysing the house sparrow data set comparing the results with the ones obtained by [8].

We present the data set in Section 2. Section 3 presents the model and discusses its properties. Section 6 compares the conditional and marginal model specifications and explains why negative heritability index appears naturally in the marginal specification. Section 5 adapts the NORTA algorithm for simulation of McGLMs. Section 6 presents a simulation study to verify the asymptotic properties of the estimating function estimators. Section 7 presents the application of the model to the data. Finally, the main results are discussed in Section 8, including some directions for future investigations. The data set and R [24] code are available in the supplementary material.

2 Data set

The case study analysed in this paper uses data from a natural meta population of house sparrow (Passer domesticus) on six islands off the coast of Helgeland, Northern Norway. For additional description of the field work, study area and genetic parenthood analyses, see [5, 8, 25, 26].

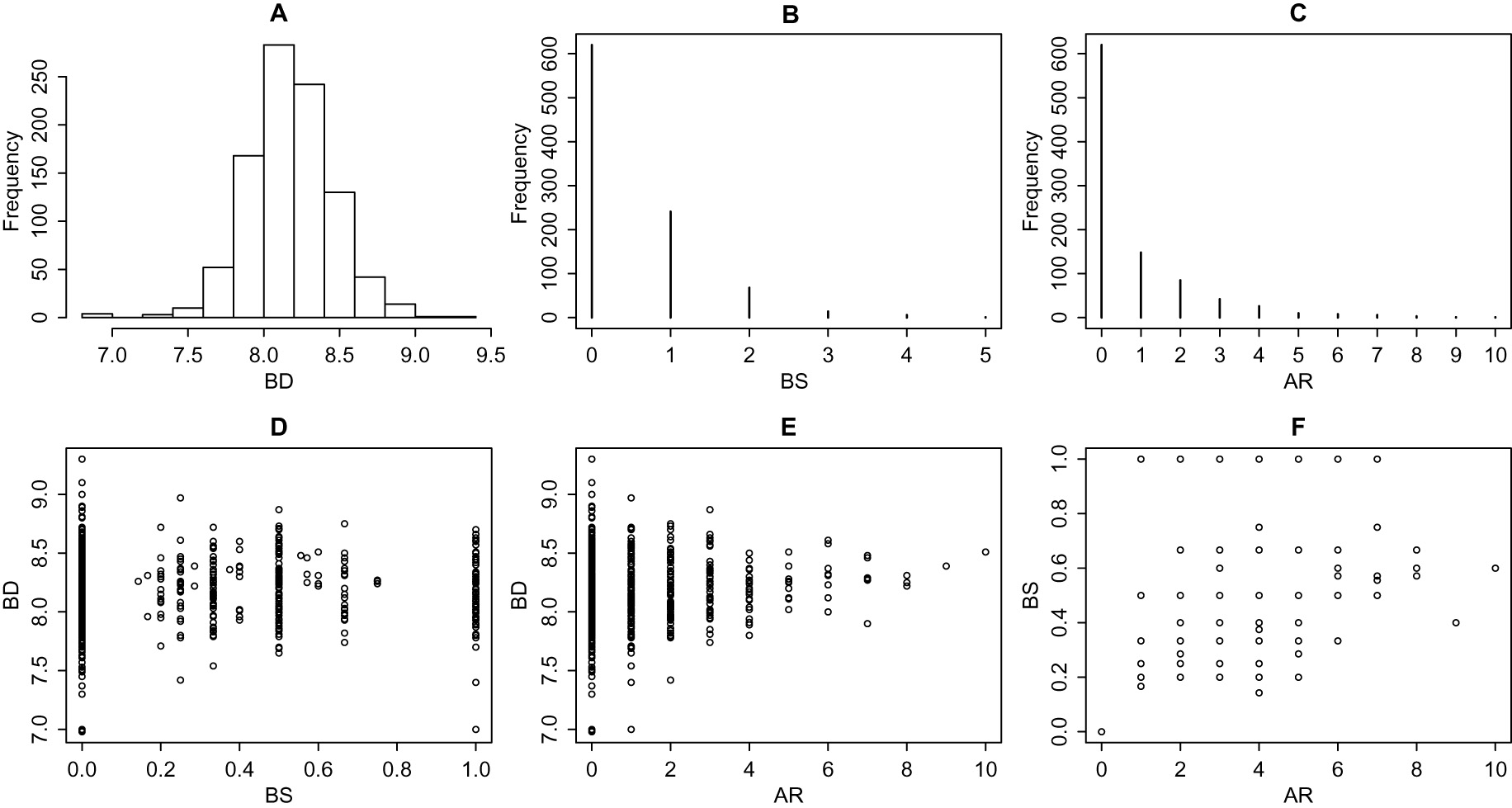

In this study, blood samples were used to determine genetic parenthood, and a genetic pedigree for the birds could be established. We highlight that the genetic parenthood structure was determined for each bird. The study has three outcomes of interest: (1) bill depth (BD), (2) breeding season success (BS), and (3) average reproductive intensity (AR). There are three covariates, namely sex (sex), hatch year (HY) and hatch island (HI). The data set that we have access corresponds to the study period from

Histograms (A to C) and scatter plots (D to F) for outcomes in the house sparrow data set.

[8] analysed the house sparrow data set using univariate GLMMs in the Bayesian framework with random effects specified on the bird level. The INLA (Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation) algorithm [12] was employed for fitting the models. For the outcome BD the authors assumed a Gaussian distribution, while for BS and AR their choices were the binomial and zero-inflated Poisson distributions, respectively. The deviance information criterion (DIC) was applied for model selection. In the Section 7, we compare the results obtained by [8] with the ones obtained by fitting the multivariate model that we shall present in Section 3.

3 McGLMs for mixed types of outcomes

Let

where

is the generalized Kronecker product [27]. The matrix

The key point for specifying McGLMs for mixed types of outcomes is the specification of the covariance matrix within outcomes

where

In the house sparrow data set, we have three types of outcomes, namely, a continuous (BD), a binomial (BS) and a count (AR). To take into account the nature of the outcomes, in this paper, we adopted three set of variance functions. To deal with continuous outcomes the power variance function

For handling binomial data we propose to use the extended binomial variance function defined by

Finally, for modelling count outcomes we following [32] adopted the Poisson-Tweedie dispersion function [33], i.e. \-

where

The power parameter

The dispersion matrix

where

McGLMs are fitted using an efficient Newton scoring algorithm based on quasi-likelihood and Pearson estimating functions, using only second-moment assumptions. The algorithm is described in detail by [16] and implemented in the mcglm [34] package for the R statistical software. The data set and R code are available in the supplementary material.

3.1 Linear covariance models for genetic data

Hadfield and Nakagawa[7] showed that virtually all models used in the fields of quantitative genetic and phylogenetic in the Gaussian case are special specifications of the matrix linear predictor eq. (2) involving different types of known matrices, such as the additive genetic relatedness matrix [2, 37]. Furthermore, [38] showed that the covariance structure induced by the orthodox Gaussian linear mixed effects model is a linear covariance model, using the identity covariance link function. In this sense, the models presented in this paper can be seen as an extension of the Gaussian linear mixed effects models for handling mixed types of outcomes.

Let

where

In special for the house sparrow data set presented in Section 2, we have three outcomes, a continuous (BD), a binomial (BS) and a count (AR). For the outcome BD exploratory analysis showed that symmetry is a reasonable assumption, thus we assume the identity link function and constant variance function, which in turn correspond to assume the Gaussian distribution. Note that, these assumptions also correspond to use the Tweedie variance function with power parameter fixed at zero. Similarly, for the binomial outcome BS we adopt the logit link function and the extended binomial variance function. Finally, for the count outcome our exploratory analysis showed a possible excess of zero and overdispersion, consequently we adopt the standard logarithm link function and Poisson-Tweedie dispersion function.

For all outcomes the matrix linear predictor was specified as a linear combination of an identity matrix (environment effect) and a relatedness matrix

where

and

The design matrices

where

Finally, from the specification of the matrix linear predictor emerges a natural marginal measure of heritability, defined for the component

that is completely analogous to the definition of heritability in the Gaussian case and does not depend on the choice of the variance function. For the special case eq. (3) the heritability index is given by

4 Conditional and marginal models: Explaining negative heritability index

McGLMs introduce the additive genetic effects directly in the marginal covariance matrix by using a linear combination of known matrices, see eq. (3). It is in contrast to the more orthodox approach based on hierarchical models, where the additive genetic effects are introduced through random effects using a conditional specification, see for example [2] and [11]. In this section, we discuss conditional and marginal model specifications in the context of additive genetic models and explain why negative heritability index appears naturally in the marginal specification. Furthermore, we use this fact to explain how to assess the significance of the genetic effects. To simplify the discussion and without loss of generality consider the one outcome case, i.e

It is assumed that the components of

The conditional specification eq. (6) makes clear that the dispersion parameters should be positive and provides a convenient interpretation of the statistical model components for quantitative genetic analysis. In this context, however, we are interested in testing whether or not the genetic additive effects are absent in the model, which in turn is equivalent to testing the dispersion parameter

A notorious special case of eq. (6) is the Gaussian linear mixed effects models obtained by assuming that

where it is clear that the only request to obtain a valid multivariate Gaussian distribution is that the covariance matrix

The McGLMs extend the Gaussian marginal specification eq. (7) to deal with non-Gaussian data by introducing link, variance and covariance link functions. In the case of one outcome and using the identity covariance link function, the general model eq. (1) customized to take into account the additive genetic effects has the following form

Hence, the terms of the diagonal matrix

5 Simulation of McGLMs

In this section we adapt the NORTA algorithm for simulation of McGLMs with mixed types of outcomes. The NORTA algorithm described in detail by [23] is a simple, but still powerful method for simulation of random vectors with arbitrary marginal distributions and pre-specified correlation matrix. The key idea behind the NORTA method is to transform a multivariate Gaussian random vector into the desired random vector.

To simplify the notation, let

where

Let

for all

where the marginal quantities

where

6 Simulation study

In this section we present a simulation study to verify the properties of the estimating function estimators. We considered a mixed types of outcomes scenario where a combination of Gaussian, binomial and Poisson outcomes is observed. The matrix linear predictor for each outcome was specified by a linear combination of an identity matrix and a relatedness matrix defined by a pedigree structure, see eq. (3). The R packages pedigree[45] and nadiv were employed to simulate the pedigree structure and build the relatedness matrix, respectively. The simulated pedigree consists of ten independent families, each one with five generations and an increasing number of individuals. We considered

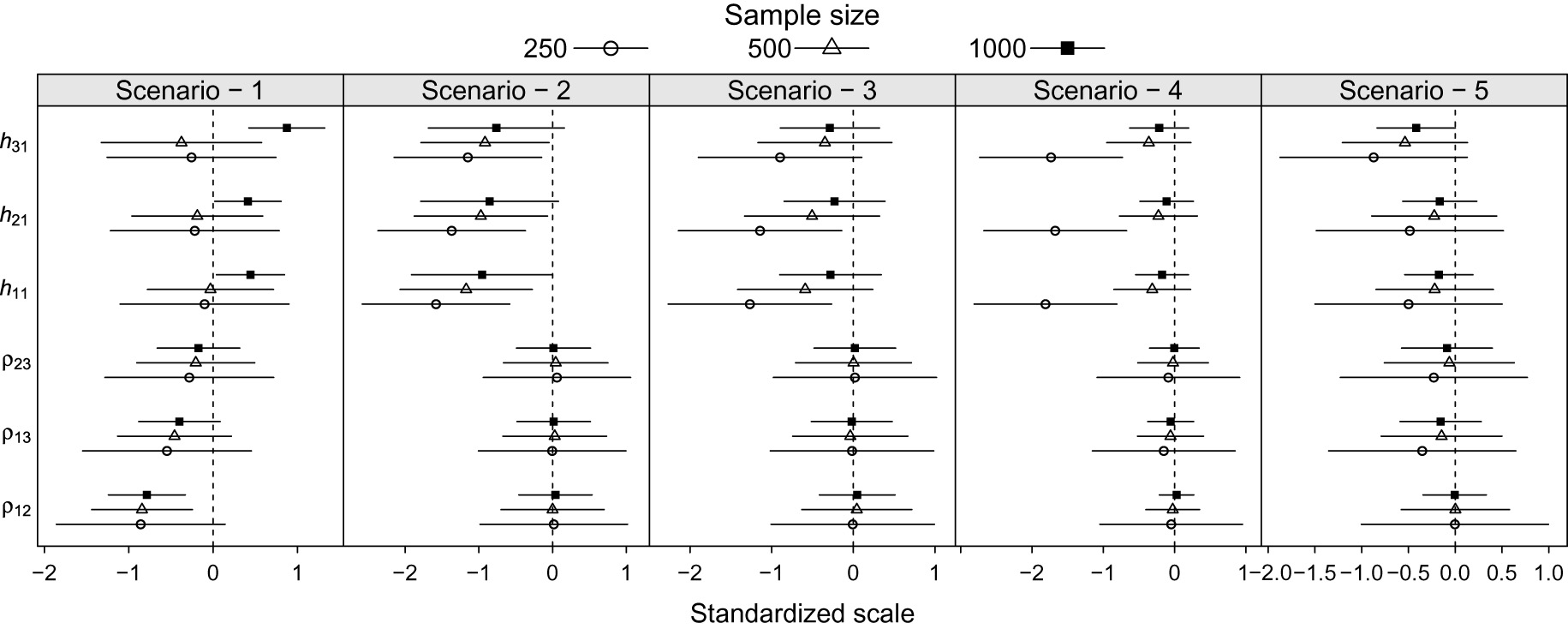

In this simulation study, we focus on the estimation of the correlation between outcomes and the new heritability index. We designed five simulation scenarios in order to explore the range of values of the heritability index. The first scenario considered a negative heritabililty index, thus we fixed the dispersion parameter values at

For all simulation scenarios, the correlations between outcomes were specified as

The Gaussian, binomial and Poisson scenarios consider linear predictors with intercepts and slopes given by:

The Gaussian marginal was modelled using the identity link function and constant variance function. For the binomial marginal we adopted the logit link function and the orthodox binomial variance function. Finally, the Poisson marginal was modelled using the log link function and the Tweedie variance function with power parameter fixed at

For each simulation scenario, we generated

Average bias and confidence interval on a standardized scale by scenarios and sample sizes for the correlation and heritability parameter estimators.

Figure 2 shows that for the scenarios

The heritability index is underestimated in the scenarios

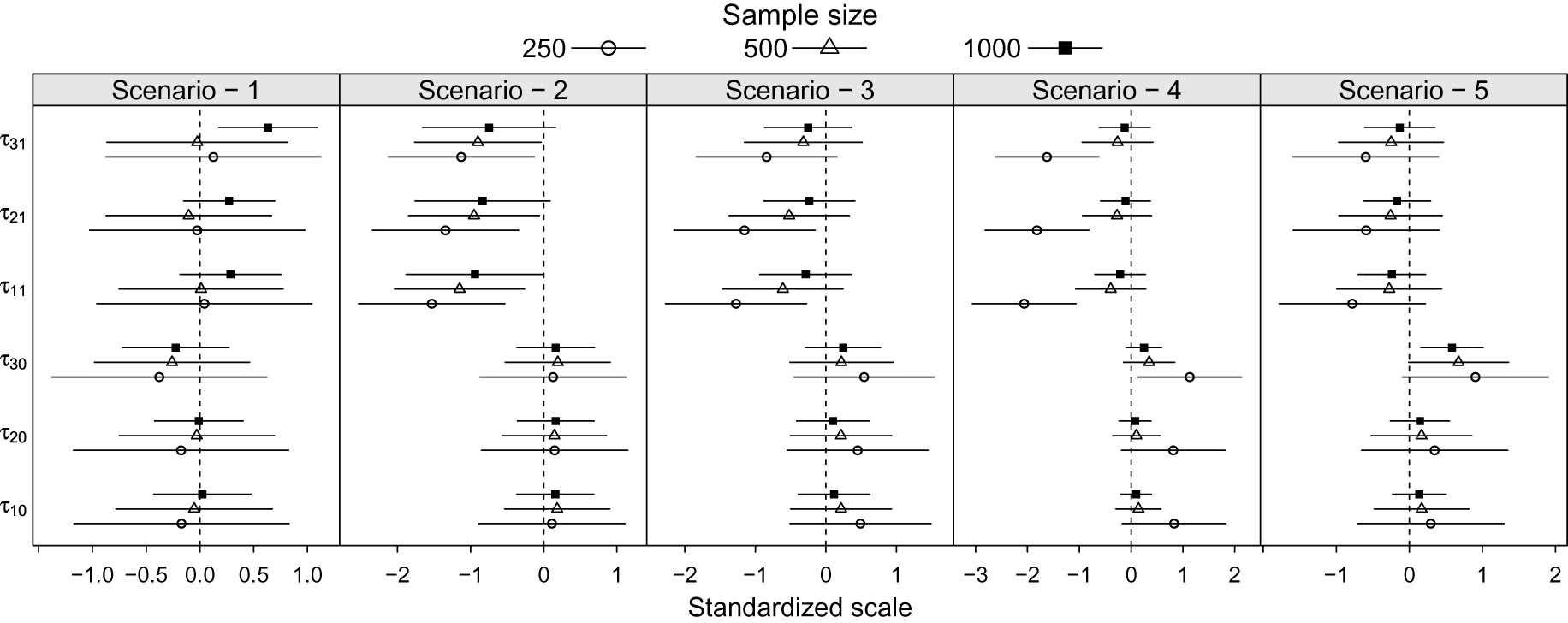

In order to further investigate the origin of the underestimation of the heritability index Figure 3 presents the average bias plus and minus the average standard error on standardized scale for the dispersion parameter estimators for each simulation scenario.

Average bias and confidence interval on a standardized scale by scenarios and sample sizes for the dispersion parameter estimators.

The results presented in Figure 3 show that in the scenarios

The simulation scenario

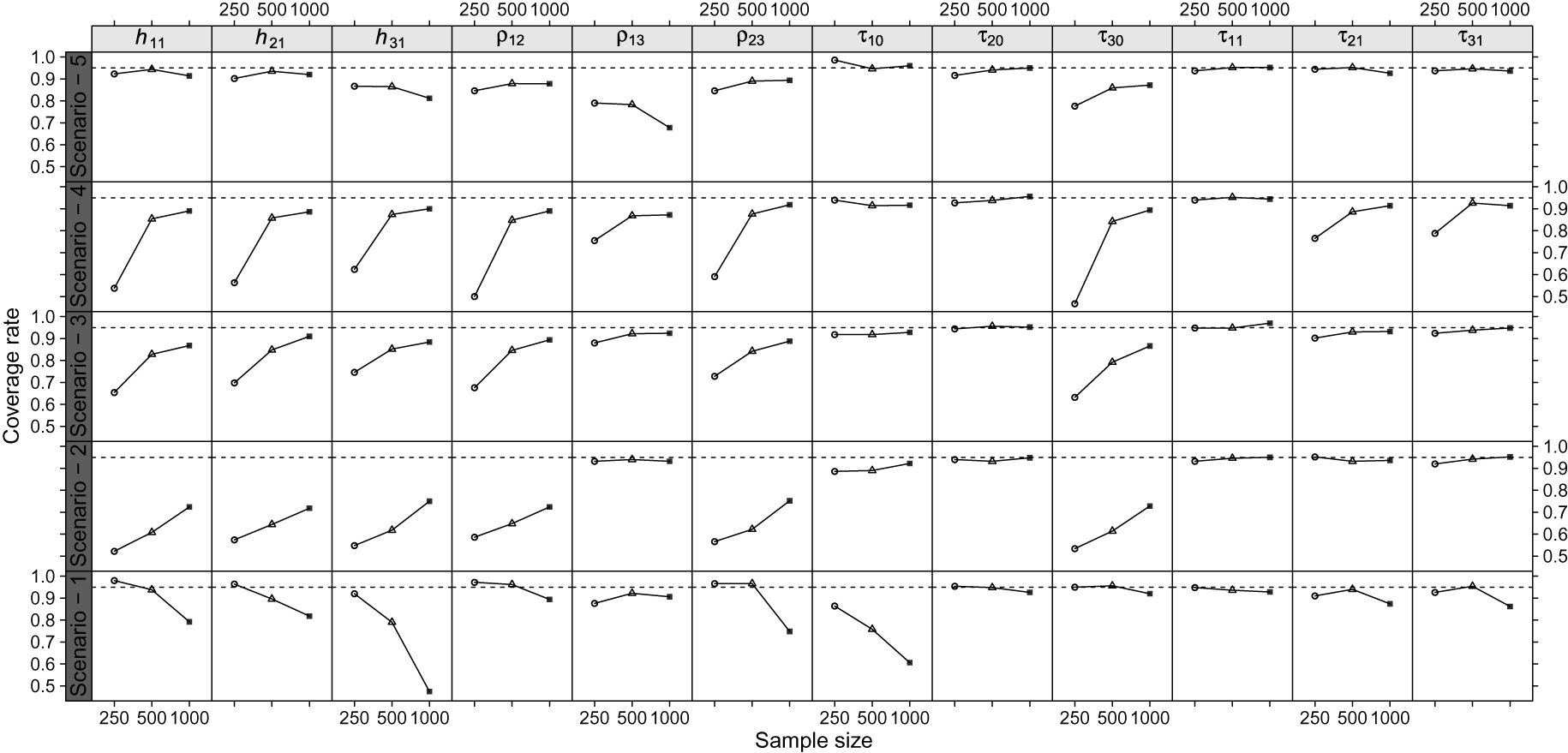

Coverage rate by scenarios and sample sizes for the heritability, correlation and dispersion parameter estimators.

The empirical coverage rate presented values close to the nominal level for scenarios

7 Data analysis

In this section, we apply the McGLMs for mixed types of outcomes to analyse the house sparrow data set presented in Section 2. The linear predictor for each outcome was specified using the three covariates available. We adopted the identity, logit and log link functions along with constant, extended binomial and Poisson-Tweedie variance/dispersion functions for the outcomes BD, BS and AR, respectively.

The matrix linear predictor for each outcome is composed of an identity matrix combined with a relatedness matrix, representing the environmental and genetic structures respectively, see Section 3.1 for detail. The R package nadiv was employed for building the relatedness matrix based on the pedigree structure available for the house sparrow data set. As discussed in Section 3.1 we adopted the identity covariance link function.

First, we investigated the estimation of the extended binomial variance function for the outcome BS. We considered three special cases: Case

Power and dispersion parameter estimates and standard errors (SE) for each special case of the extended binomial variance function for the outcome BS.

| Estimates (SE) | |||

| Case | Case | Case | |

The results in Table 1 show that the model in the case

In all cases presented in Table 1 the dispersion parameters associated with the genetic structure (

Power, dispersion and heritability parameter estimates and standard errors (SE) by models fitted to the house sparrow data set.

| Estimates (SE) | ||||

| BD | BS | AR | Joint | |

Table 2 shows that the genetic structure has a significant effect only for the outcome BD. In that case, the heritability index is different from zero, as expected. On the other hand, for the outcomes BS and AR the heritability index was negative, but non-significant.

In general the univariate and multivariate models provide the same interpretation in terms of genetic effects. Differences appear in the size of the standard errors associated with the dispersion parameters and consequently in the standard errors of the heritability index. On average the standard errors from the joint model are

The differences may be explained by the correlation between outcomes, whose estimates and standard errors were as follows:

The correlation between BD and BS

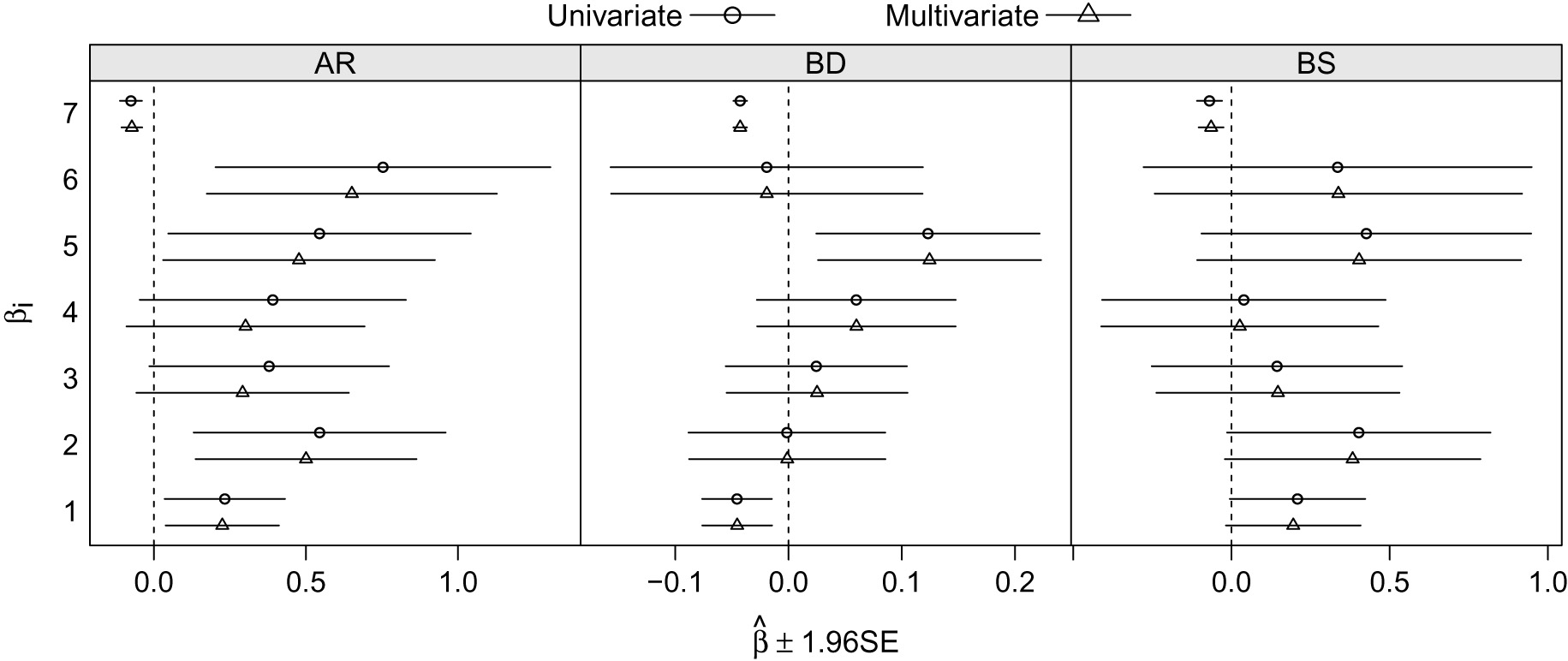

Regression parameter estimates and

Figure 5 shows that for the outcome BD the confidence intervals from the univariate and multivariate models are really similar, in fact the difference on average is

[8] results showed that the heritability for BD, BS and AR were

The results presented in Table 2 show that the heritability index for the outcome BD was

8 Discussion

We presented a general statistical modelling framework for analysis of mixed types of outcomes in the context of genetic data. The models were motivated by the house sparrow data set, where a mixed of continuous, binomial and count outcomes are of interest. Furthermore, we adapted the NORTA algorithm for simulation of McGLMs and proposed a new index of heritability.

The marginal covariance structure within outcomes were modelled by means of a variance function and a matrix linear predictor combined with a covariance link function. In this paper, we focused on the identity covariance link function, since many important models used in quantitative genetic analysis appear as special cases. The variance function plays an important role in our framework, since it allows us to deal with different types of outcomes in a unified way. Furthermore, the estimation of the power parameter provides extra flexibility for our models. The linear structure of the matrix linear predictor allows us to accommodate the genetic structure as well as extend the model to deal with repeated measures, longitudinal, spatial and covariates effects. Moreover, in the context of genetic data the specification of the matrix linear predictor provides an intuitive way to define a measure of heritability for non-Gaussian data. Finally, the joint covariance matrix is specified using the generalized Kronecker product, allowing to compute the correlation between outcomes.

The second-moment assumptions allow us to adopt an estimation function approach for parameter estimation and inference. The advantages of this approach are that the estimation procedure relies on a relatively simple and efficient Newton scoring algorithm and keep the traditional population average interpretation for both regression and dispersion parameters. The simulation study presented in Section 5 showed that in general the estimating function estimators are unbiased and consistent for large samples. The simulation study also showed that for small sample size the heritability index can be strongly underestimate mainly when the parameters are close to the border of the parameter space, as appear in the scenarios

Regarding the data analysis, our results showed a significant genetic effect for the outcome BD and non-significant genetic effect for the outcomes BS and AR. These results agree with previous results obtained by [8], although these authors found a weak but still significant genetic effect for the outcome AR. The main advantages to fit a multivariate model are the possibility to compute the correlation matrix between outcomes and improve the estimation of the regression and dispersion parameters. As shown in our data analysis, in general the correlation between outcomes implies smaller standard errors for the regression and dispersion parameters.

Possible topics for further investigation and extensions include designing simulation studies to explore in detail the effect of different number of generations and families in the pedigree structure. An important aspect of the presented framework is the possibility to obtain negative heritability index. Thus, an interesting topic is to investigate from a genetic viewpoint what such negative values represent in practical data analyses. In the genetic context the genetic and environment correlations are two measures of interest. However, in the framework presented in this paper, we can assess only the correlation between outcomes (phenotypic correlation), i.e. we cannot distinguish between the genetic and environment correlations. Thus, a topic for future investigation is to propose marginal models able to distinguish between these two sources of correlation. In terms of modelling framework is interesting to investigate the performance of the McGLMs for the analysis of multivariate binary traits. Furthermore, theoretical and computational developments are required in order to construct new estimating functions to handle data not missing at random and make prediction using the Best Linear Unbiased Predictor (BLUP).

Acknowledgements:

For Bent Jø rgensen (1954

References

1. Henderson C. Estimation of genetic parameters. Ann Math Stat 1950;21:309–210.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Sorensen D, Gianola D. Likelihood, Bayesian, and MCMC methods in quantitative genetics. New York: Statistics for Biology and Health, Springer, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Dempster ER, Lerner IM. Heritability of threshold characters. Genetics 1950;35:212–236.10.1093/genetics/35.2.212Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Hill WG. Understanding and using quantitative genetic variation. Philos Trans R Soc London, Ser B 2009;365:73–85.10.1098/rstb.2009.0203Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Jensen H, Steinsland I, Ringsby TH, Sæther B-E. Evolutionary dynamics of a sexual ornament in the house sparrow (Passer domesticus): the role of indirect selection within and beween sexes. Evolution 2008;62:1275–1293.10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00395.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Gianola D, Fernando RL. Bayesian methods in animal breeding theory. J Anim Sci 1986;63:217–244.10.2527/jas1986.631217xSuche in Google Scholar

7. Hadfield JD, Nakagawa S. General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology: phylogenies, taxonomies and multi-trait models for continuous and categorical characters. J Evol Biol 2010;23:494–508.10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01915.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Holand AM, Steinsland I, Martino S, Jensen H. Animal models and integrated nested Laplace approximations. G3: Genes, Genome, Genetics, 2013;3:1241–1251.10.1534/g3.113.006700Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. McCulloch CE. Maximum likelihood algorithms for generalized linear mixed models. J Am Stat Assoc 1997;92:162–170.10.1080/01621459.1997.10473613Suche in Google Scholar

10. Fong Y, Rue H, Wakefield J. Bayesian inference for generalized linear mixed models. Biostatistics 2010;11:397–412.10.1093/biostatistics/kxp053Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Hadfield JD. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J Stat Software 2010;33:1–22.10.18637/jss.v033.i02Suche in Google Scholar

12. Rue H, Martino S, Chopin N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. J R Stat Soc, Ser B 2009;71:319–392.10.1111/j.1467-9868.2008.00700.xSuche in Google Scholar

13. Liu J, Huang J, Ma S. Penalized multivariate linear mixed model for longitudinal genome-wide association studies. BMC Proc 2014;8:1–4.10.1186/1753-6561-8-S1-S73Suche in Google Scholar

14. Liu J, Yang C, Shi X, Li C, Huang J, Zhao H, Ma S. Analyzing association mapping in pedigree-based gwas using a penalized multitrait mixed model. Genet Epidemiol 2016;40:382–393.10.1002/gepi.21975Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. de Villemereuil P, Schielzeth H, Nakagawa S, Morrissey M. General methods for evolutionary quantitative genetic inference from generalised mixed models. Genetics 2016;204(3):1281–1294.10.1534/genetics.115.186536Suche in Google Scholar

16. Bonat WH, Jørgensen B. Multivariate covariance generalized linear models. J R Stat Soc, Ser C 2016;65:649–675.10.1111/rssc.12145Suche in Google Scholar

17. Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13–22.10.1093/biomet/73.1.13Suche in Google Scholar

18. Carey VJ. gee: generalized estimation equation solver, 2015, http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gee, r package version 4.13-19.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Højsgaard S, Halekoh U, The Yan J. R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Software 2006;15:1–11.10.18637/jss.v015.i02Suche in Google Scholar

20. Jørgensen B, Knudsen SJ. Parameter orthogonality and bias adjustment for estimating functions. Scand J Stat 2004;31, 93–114.10.1111/j.1467-9469.2004.00375.xSuche in Google Scholar

21. Hall DB, Severini TA. Extended generalized estimating equations for clustered data. J Am Stat Assoc 1998;93, 1365–1375.10.1080/01621459.1998.10473798Suche in Google Scholar

22. Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford: Oxford Statistical Science Series, 2002.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Cario MC, Nelson BL. Modeling and generating random vectors with arbitrary marginal distributions and correlation matrix, Technical report, Northwestern University, 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Core Team R. Language R: A and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2015, ISBN 3-900051-07-0.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Pärn H, Jensen H, Ringsby TH, Sæther B-E. Sex-specific fitness correlates of dispersal in a house sparrow metapopulation. J An Ecol 2009;78:1216–1225.10.1111/j.1365-2656.2009.01597.xSuche in Google Scholar

26. Ringsby TH, B-E Sæther, Tufto J, Jensen H, Solberg EJ. Asynchronous spatiotemporal demography of a house sparrow metapopulation in a correlated environment. Ecology 2002;83:561–569.10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0561:ASDOAH]2.0.CO;2Suche in Google Scholar

27. Martinez-Beneito MA. A general modelling framework for multivariate disease mapping. Biometrika 2013;100:539–553.10.1093/biomet/ast023Suche in Google Scholar

28. Bonat WH, Kokonendji CC. Flexible Tweedie regression models for continuous data. J Stat Comput Simul 2017;87:2138–2152.10.1080/00949655.2017.1318876Suche in Google Scholar

29. Jø rgensen B. Exponential dispersion models. J R Stat Soc, Ser B 1987:49:127–162.10.1111/j.2517-6161.1987.tb01685.xSuche in Google Scholar

30. Jø rgensen B. The theory of dispersion models. London: Chapman & Hall, 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Barndorff-Nielsen O, Jø rgensen B. Some parametric models on the simplex. J Multivariate Anal, 1991;39:106–116.10.1016/0047-259X(91)90008-PSuche in Google Scholar

32. Bonat WH, Olivero J, Grande-Verga M, Fárfan MA, Fa JE. Modelling the covariance structure in marginal multivariate count models. J Agric Biol Environ Stat 2017;1–19.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Jø rgensen B, Kokonendji C. Discrete dispersion models and their Tweedie asymptotics. AStA Adv Stat Anal 2015;100:43–78.10.1007/s10182-015-0250-zSuche in Google Scholar

34. Bonat WH. mcglm: multivariate covariance generalized linear models, 2016. http://git.leg.ufpr.br/wbonat/mcglm, R package version 0.3.0.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Anderson TW. Asymptotically efficient estimation of covariance matrices with linear structure. The Ann Stat 1973;1:135–141.10.1214/aos/1193342389Suche in Google Scholar

36. Pourahmadi M. Maximum likelihood estimation of generalised linear models for multivariate normal covariance matrix. Biometrika 2000;87:425–435.10.1093/biomet/87.2.425Suche in Google Scholar

37. Lynch M, Walsh B. Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits. Oxford: Sinauer, 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Demidenko E. Mixed models: theory and applications with R. New Jersey: Wiley, 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Wolak ME. nadiv: an R package to create relatedness matrices for estimating non-additive genetic variances in animal models. Meth Ecol Evol 2012;3:792–796.10.1111/j.2041-210X.2012.00213.xSuche in Google Scholar

40. Self SG, Liang K-Y. Asymptotic properties of maximum likelihood estimators and likelihood ratio tests under nonstandard conditions. J Am Stat Assoc 1987;82:605–610.10.1080/01621459.1987.10478472Suche in Google Scholar

41. Crainiceanu CM, Ruppert D. Likelihood ratio tests in linear mixed models with one variance component. J R Stat Soc, Ser B 2004;66:165–185.10.1111/j.1467-9868.2004.00438.xSuche in Google Scholar

42. Stram DO, Lee JW. Variance components testing in the longitudinal mixed effects model. Biometrics 1994;50:1171–1177.10.2307/2533455Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Huifen C. Initialization for norta: generation of random vectors with specified marginals and correlations. INFORMS J Comput 2001;13:312–331.10.1287/ijoc.13.4.312.9736Suche in Google Scholar

44. NORTARA: Su P. generation of multivariate data with arbitrary marginals, 2014, R package version 1.0.0.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Coster A. pedigree: pedigree functions, 2013, R package version 1.4.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplemental Material

The R code and data set are available in the supplementary material website.http://www.leg.ufpr.br/doku.php/publications:papercompanions:biometrics

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Estimation and Inference for the Mediation Proportion

- Adaptation of Chain Event Graphs for use with Case-Control Studies in Epidemiology

- Modelling Mixed Types of Outcomes in Additive Genetic Models

- A Comparison of Methods for Estimating the Determinant of High-Dimensional Covariance Matrix

- Generalized Confidence Intervals for Intra- and Inter-subject Coefficients of Variation in Linear Mixed-effects Models

- Kernel-Based Measure of Variable Importance for Genetic Association Studies

- A Generally Efficient Targeted Minimum Loss Based Estimator based on the Highly Adaptive Lasso

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Estimation and Inference for the Mediation Proportion

- Adaptation of Chain Event Graphs for use with Case-Control Studies in Epidemiology

- Modelling Mixed Types of Outcomes in Additive Genetic Models

- A Comparison of Methods for Estimating the Determinant of High-Dimensional Covariance Matrix

- Generalized Confidence Intervals for Intra- and Inter-subject Coefficients of Variation in Linear Mixed-effects Models

- Kernel-Based Measure of Variable Importance for Genetic Association Studies

- A Generally Efficient Targeted Minimum Loss Based Estimator based on the Highly Adaptive Lasso