Abstract

Objectives

Adolescents with congenital gastrointestinal malformations, such as esophageal atresia, anorectal malformations, and Hirschsprung’s disease, frequently face long-term physical and psychological sequelae. Despite increasing recognition of the need for structured transition of care (TOC) programs, standardization remains limited. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a structured interdisciplinary TOC program for adolescents with gastrointestinal malformations, focusing on patient well-being, gastrointestinal quality of life, transition competence, and satisfaction.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational study including all patients aged ≥14 years with esophageal atresia, anorectal malformations, and/or Hirschsprung’s disease who participated in a standardized TOC program at Hannover Medical School. The multidisciplinary team included pediatric and adult gastroenterologists, nutritionists, psychologists, and surgeons. Patient-reported outcomes were assessed at baseline and follow-up using validated instruments: WHO-5 (well-being), GIQLI (gastrointestinal quality of life), TCS (transition competence), and the ZAP questionnaire (satisfaction).

Results

A total of 63 patients were included. Compared to healthy controls, patients scored significantly lower on the WHO-5 and GIQLI (p<0.0001), indicating reduced well-being and quality of life. TCS scores improved significantly from 27.35 to 31.80 (p=0.015) during the visits, reflecting increased transition competence. Satisfaction with the program was high across all ZAP domains, particularly in interaction (93.1 %) and organization (91.3 %).

Conclusions

This study presents the first standardized transition of care program for patients with congenital gastrointestinal malformations in Germany. The program improved transition competence and was associated with high patient satisfaction. While emphasizing the value of structured, patient-centered transition care, larger studies are needed to validate these findings and support wider implementation.

Introduction

Transition of care (TOC) programs are mandatory to ensure the continuity of care as pediatric patients with chronic and complex conditions have to be transferred to adult healthcare systems. Research shows that up to 40 % of pediatric patients are lost to follow-up during this transitional phase, but structured programs can reduce this figure to as low as 10 % [1]. Despite advances in neonatal surgery, up to 85 % of esophageal atresia (EA) patients [2], [3], [4] and one-third of anorectal malformation (ARM) patients [5], [6], [7], [8] continue to experience significant complications, affecting their quality of life and mental health. Thus, in patients with rare congenital malformations such as EA (incidence 1:3.000–5.000 live births [9], 10]), anorectal malformation (incidence 1:3.000–5.000 live births [11]), and Hirschsprung’s Disease (HD, incidence 1:5.000 live births [12]) and persistence of chronic sequelae into adulthood, the need for such programs is evident [13], [14], [15], [16].

Despite an increasing recognition of the importance of transitional care over the last two decades, there is still a lack of standardization and evidence [17], [18], [19]. While a structured transition to adult healthcare for children with congenital heart disease has already been recommended by the American Heart Association in 2011 [20], standardization for children with congenital gastrointestinal malformations has yet to be addressed in many places [21], [22], [23]. Recent findings from a survey involving the EUPSA Network Office, ERNICA, and eUROGEN revealed that, despite awareness of the importance of TOC programs, today, they are implemented in less than 50 % of the participating centers. Furthermore, there is substantial heterogeneity in the content and timing of these programs [19].

In our institution we have implemented an interdisciplinary standardized TOC program for patients affected by congenital gastrointestinal malformations since 2014. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of our interdisciplinary transitional care program using dedicated questionnaires that assess patients’ well-being, gastro-intestinal quality of life, transition competence and subjective patient satisfaction with the TOC program, indicating its efficacy.

Materials and methods

Study design

This prospective observational study evaluated the effects of our interdisciplinary TOC-program for patients with congenital gastrointestinal malformations on their autonomy and quality of life. The study was approved by our local ethics committee (reference number 10817_BO_K_2023).

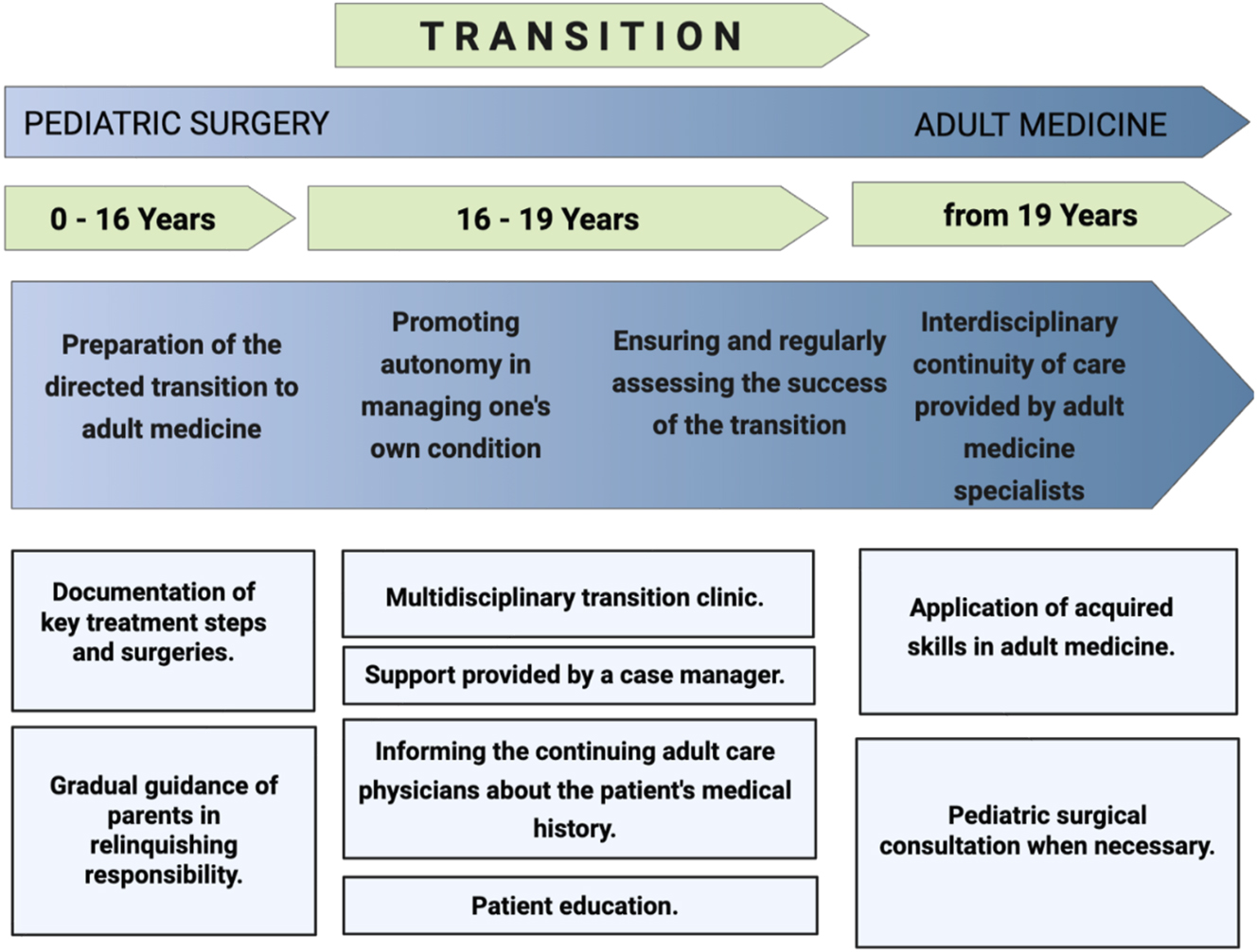

Our interdisciplinary TOC-program involved regular outpatient clinic visits with a multidisciplinary team, including pediatric surgeons, adult gastroenterologists with expertise in pediatric endoscopy, nutrition experts, and child and adolescent psychologists. During these visits, the patient’s medical status, quality of life, transition competence, and satisfaction with the transition process were documented (Figure 1).

Structure of our TOC-program.

Patients with congenital gastrointestinal malformations, including ARM, Hirschsprung’s Disease, and EA who received their primary or secondary treatment at Hannover Medical School (MHH) and participated in regular follow-up care were included in the interdisciplinary transition care program during adolescence (ages >14 years). Additionally, adolescents with gastrointestinal malformations who were not part of any regular follow-up care but voluntarily chose to participate after referral from family doctors or support groups were also included.

Instruments

Outcome parameters were assessed before and after the first visit and successive follow-up visits. Patients and families completed validated, standardized questionnaires to assess subjective well-being (WHO-5 [24]) and gastrointestinal quality of life (GIQLI [25]). Results were compared to literature based normal values from healthy control populations, where available. Additionally, transition competence and satisfaction with the TOC program were measured using the Transition Competence Scale (TCS) by Herrmann-Garitz et al. [26] and the ZAP-questionnaire by Bitzer et al. [27], respectively. All patients and families completed these questionnaires anonymously and voluntarily.

WHO-5 Well-Being Index [24]: The WHO-5 Well-Being Index is a validated tool to measure subjective psychological well-being. It consists of five questions using a 6-point Likert scale, scored from 0 to 5, resulting in a total score range of 0–25 points. Higher scores indicate better well-being, with scores below 13 suggesting reduced well-being, and scores below 7 indicating a high likelihood of depression. The healthy control average is 18.36 points (SD: 4.8, n=929) [24]. The WHO-5 is a quick, reliable screening tool widely used in clinical settings and research to assess well-being.

GIQLI [25]: To assess health-related quality of life, particularly with regard to gastrointestinal issues, we used the GIQLI [25], a 36-item validated questionnaire. It is used to evaluate five domains, with the “core symptoms” domain being the most prominent, and additional subdomains that address physical, psychological, social, and disease-specific aspects. The GIQLI comprises a 5-point Likert scale to assess the frequency of symptoms („all the time“, „most of the time“, „occasionally“, „rarely“ and „never“). Scores range from 0 to 144, with higher scores indicating a better gastrointestinal quality of life. The average value of healthy control is 125.8 points (SD: 13.0, n=168) [25].

TCS [26]: The Transition Competence Scale was used to assess the competence of patients in the transition from pediatric to adult care. The scale consists of 11 items grouped into three categories: “work readiness,” “health-related knowledge,” and “care-related competence,” as well as a single item regarding self-perceived readiness for adult care. The scale comprises a 4-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 11 to 44 points. Higher scores indicate better transition competence. A healthy control group was defined as a full competence score of 44 points [26].

ZAP-Questionnaire [27]: The ZAP-Questionnaire was used to assess patient satisfaction with the transition program. It contains 23 items across six categories: “organization,” “information,” “interaction,” “professional competence,” “trust,” and “quality of treatment,” all using 4-point Likert scales. The scores were converted into percentages, with higher percentages reflecting greater satisfaction. Control groups were established based on following factors: age (18–30 years), gender, and type of care (specialist care vs. family doctor) [27]. Our control groups included male and female, aged 18–30 years, receiving specialist care.

Statistical analysis

Clinical variables were reported as percentage and means +/− standard deviation. Proportions of categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher´s exact test. To compare our groups with healthy controls, independent samples t-test; for within-patient comparisons over time, dependent samples t-test were used. Microsoft Excel® was utilized for statistical analysis, including diagrams and box plots. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Additionally, for groups comprising fewer than 30 patients, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (KS-test) was employed to verify that the patient sample accurately represented the general population. Incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Demographics and contact to transition (Tables 1a, 1b and 2)

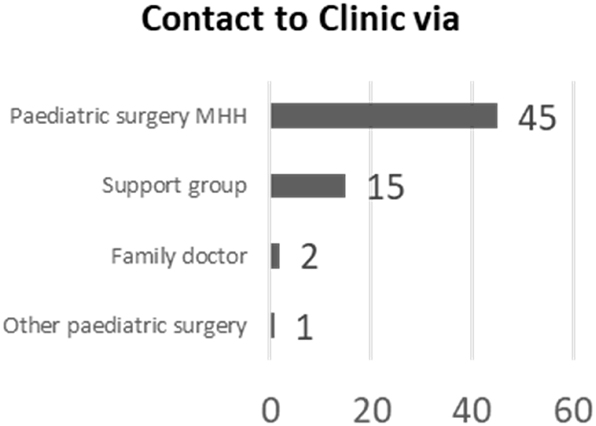

Of 202 patients enrolled in the TOC-program, 63 participated to the survey. Table 1a outlines their demographics at the first visit. Among participants, 63.4 % (n=40) were ≥18 years old, and 61.9 % (n=39) had EA (out of which n=28 isolated). Additionally, 47.6 % (n=30) had colorectal malformations, with 11 having both conditions. Surgical interventions are listed in the Supplementary Material (Table 1b). Most participants were referred by the department of pediatric surgery or from parent support groups (Table 2).

Patients’ demographics. Age of the patients at start of transition of care. n=number of patients

| Age at start of transition (in years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <14 | 14–15 | 16–17 | 18–19 | >19 | Sum |

| EA (n) | 0 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 13 | 28 |

| ARM/HD (n) | 1 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 19 |

| Combined (n) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 11 |

| Other (n) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Overall (n) | 1 | 11 | 11 | 21 | 19 | 63 |

Contact to transition care program. MHH=Hannover medical school.

|

Specialists and diagnostic work-up during transition (Tables 3a and 3b)

During the study period as part of the transition program, patients received different types of specialists’ support and diagnostic work-up, depending on their symptoms and needs.

Patients received predominantly support from general (69.8 %) and pediatric (31.8 %) practitioners, along with internal medicine specialists (20 %) (Table 3a).

Representation of further specialist treatment needed performed during the TOC.

| Further treatment by | ||

|---|---|---|

| Multiple answers possible. No. of patients n=63. | ||

| n | % Of patients | |

| General medicine | 44 | 69.84 % |

| Paediatrics | 20 | 31.75 % |

| Internal medicine | 13 | 20.63 % |

| Cardiology | 4 | 6.35 % |

| Pulmonology | 3 | 4.76 % |

| Gynecology | 2 | 3.17 % |

| Urology | 2 | 3.17 % |

| Paediatric surgery | 2 | 3.17 % |

| Nephrology | 1 | 1.59 % |

Representation of the diagnostic work-up performed during the TOC.

| Diagnostic work-up during transition | |

|---|---|

| Multiple answers possible. No. of patients n=63. | |

| n | |

| Diagnostic endoscopy | 68 |

| Change of/additional medication | 59 |

| Non-invasive diagnostic procedures | 59 |

| Consultation of other subspecialities | 40 |

| Imaging | 27 |

| Other invasive diagnostic procedures | 23 |

| Consultation of psychologists | 10 |

| Surgical procedures | 7 |

| Interventional endoscopy | 4 |

Among 63 patients (108 visits), diagnostic endoscopies were the most common procedure (68 instances, 69.8 %). Seven patients required corrective surgery, and 50 cases needed consultations with other medical subspecialties (Table 3b).

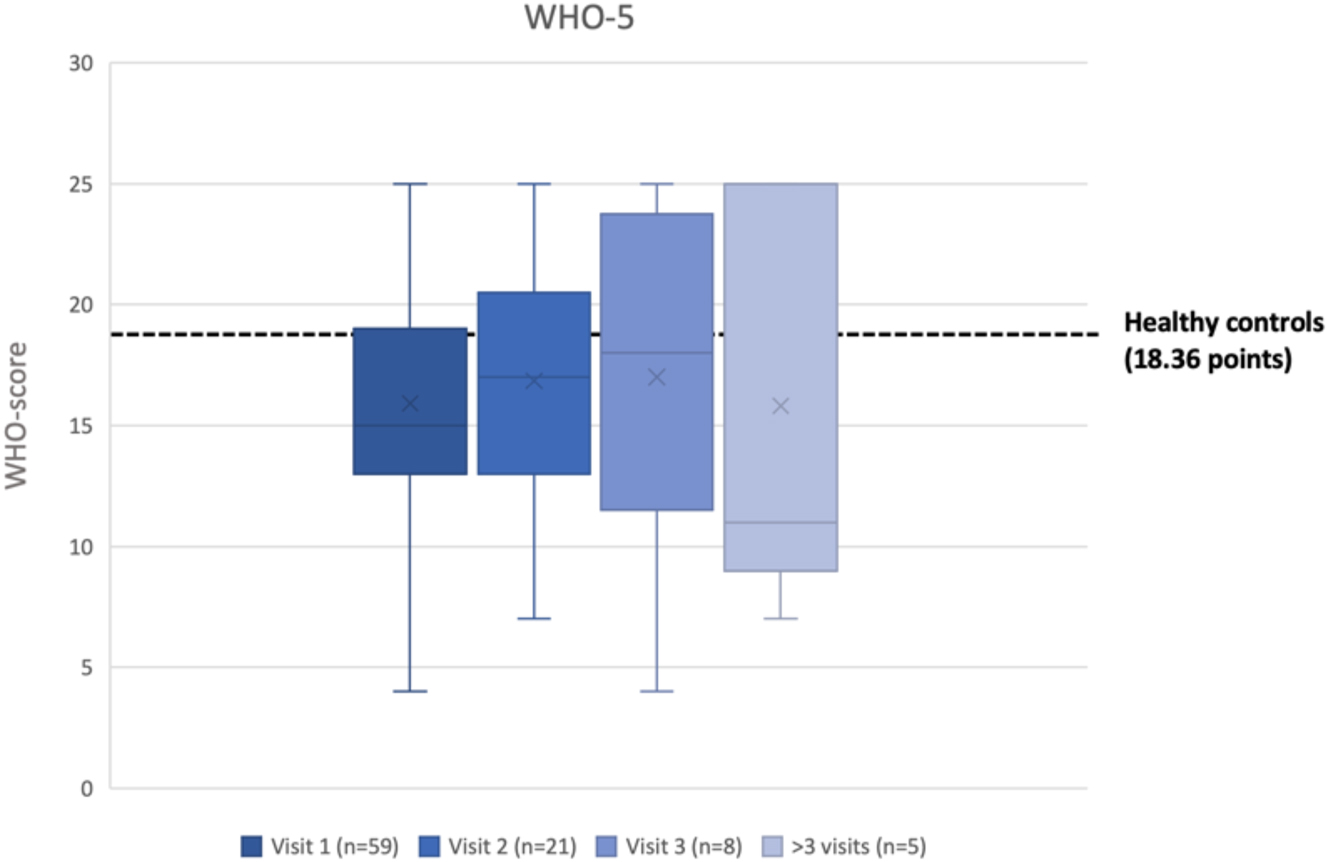

WHO-5 (Figure 2)

Regarding the WHO-5 well-being index, 59 out of 63 patients returned the questionnaire during their first visit to our program. The WHO´s scores were significantly lower as compared to healthy controls (15.92, SD 4.52 vs. 18.36, SD: 4.80; p=0.00011). Two patients (1.18 %) scored less than seven points, falling in the category “depression most likely”. Figure 2. A detailed division per entity may be found in the Supplement Material (Table 4).

Box-plot with WHO-5 graphical representation. X=average score; _= median score.

During the second visit to the TOC-program, only 20 out of 59 patients returned the questionnaire. Since the sample size was small (n<30), the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to ensure the data represented the general population. The test confirmed a normal distribution (critical value=0.294, t=0.166).

These 20 patients reached an average of 16.65 points (SD: 3.84) at their first visit, slightly below healthy controls, but the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.061). On the second visit, their average score decreased to 16.45 (SD: 4.89) (p=0.097). No significant change of WHO5-scores occurred between first and second visit (p=0.857). Only patients with combined morbidity showed an improvement between first and second visit, however not statistically significant (details in Supplement Table 4).

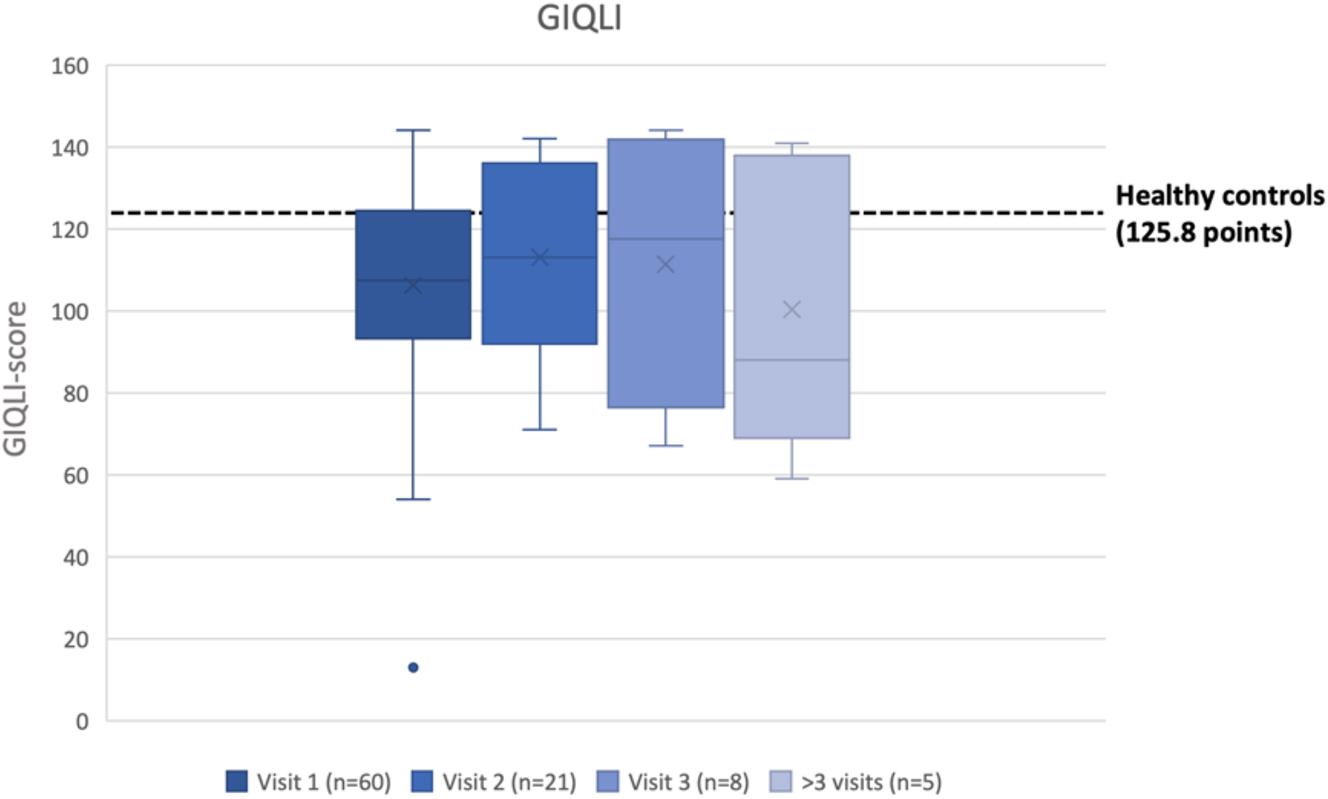

GIQLI (Figure 3 and Table 5)

At the first visit, 60 patients returned their GIQLI scoring in average significantly lower compared to healthy controls (106.23, SD:24.34 vs. 125.8, SD:13.0; p<0.00001). (Figure 3). A detailed division per pathology is visible in the Supplementary Material (Table 5).

Box-plot with graphical representation of the GIQLI score. X=average score; _= median score.

At the second visit, 20 patients returned the GIQLI, they had normal distribution (KS-test: critical value=0.294, t=0.096). These patients scored an average of 112.55 points (SD: 17.38) at the first and 111.55 (SD: 23.09) at the second visit. GIQLI was in both visits significantly lower than healthy controls (respectively p=0.0036 at the first and p=0.0125 at the second visit). No significant changes have been revealed between first and second visit (p=0.849).

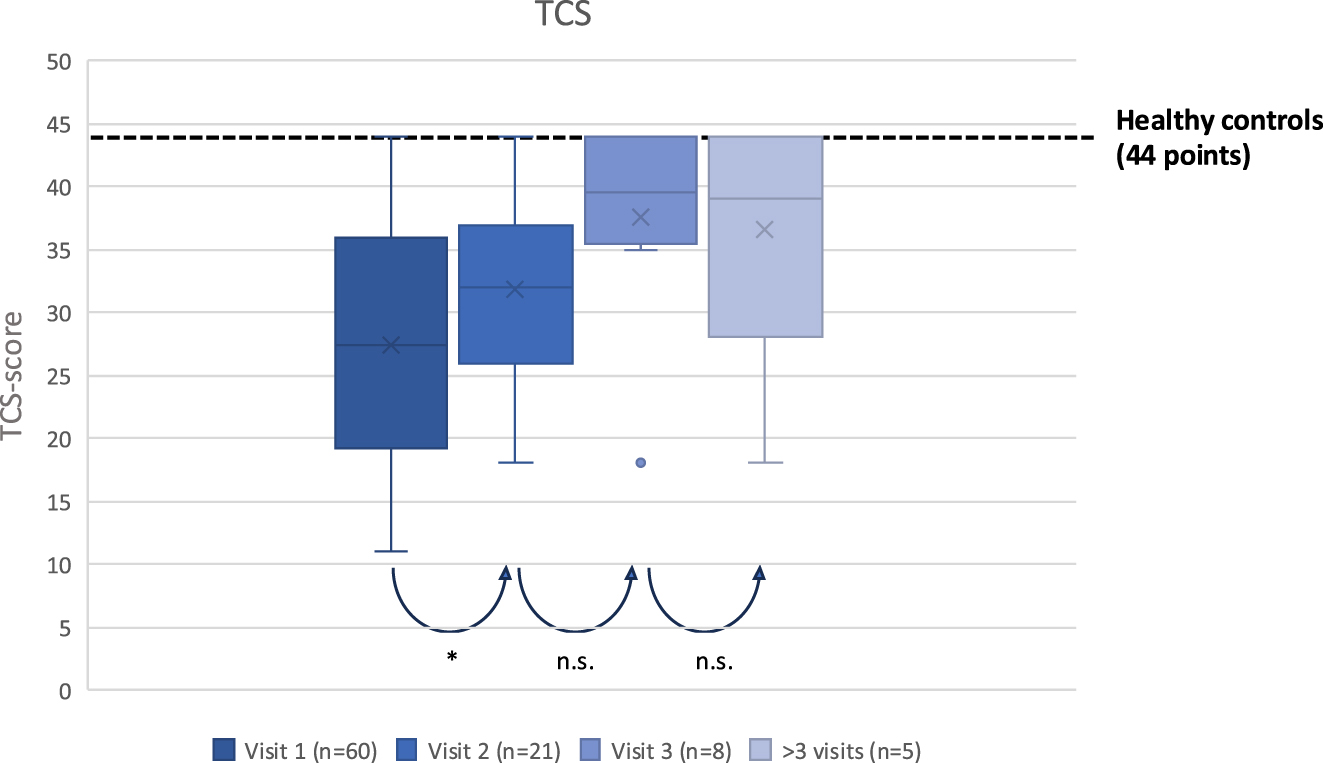

TCS (Figure 4)

At the first visit, 60 patients completed the TCS, averaging 27.43 out of 44 points (SD: 9.82), significantly lower than healthy controls (p<0.00001). At the second visit, 20 patients returned the TCS questionnaire, and normal distribution was confirmed (critical value=0.294, t=0.151). For these patients the TCS score improved significantly from 27.35 (SD: 10.40) to 31.80 (SD: 7.73) points (p=0.01509), demonstrating the educative impact of the transition care program (Figure 4).

Box-plot with graphical representation of the transition competence scale (TCS). Considering the overall visits of the patients an increasing improvement in subjective patients’ competence could be observed, with statistical significance between first and second vist. X=average score; _= median score *=p<0.05 n.s.=non statistical significance.

ZAP (Figure 5)

54 ZAP questionnaires were evaluable. Compared to reference data for “organization,” “information,” “personal competence,” and “interaction,” our TOC-program was scored highest in “interaction” (93.1 %, 21.95/24 points, SD: 4.77) and “organization” (91.3 %, 8.22/9 points, SD: 1.04). “Professional competence” scored 86.1 % (5.07/6 points, SD: 1.33), while “information” scored lowest at 81.3 % (19.27/24 points, SD: 4.48). Categories without reference comparisons were “trust” (87.65 %, 2.58/3 points, SD: 0.71) and “quality of treatment” (85.8 %, 2.53/3 points, SD: 0.78). Overall satisfaction was 59.62/69 points (SD: 9.07). Our TOC-program achieved significantly higher satisfaction-scores than in the literature available reference groups [27] (p<0.00001).

![Figure 5:

Diagram illustrating satisfaction with the program. Each category was compared to similar assessments described in the literature. A value of 100 % represent the maximum possible score for each category. Satisfaction scores in category “Interaction” and “Organisation” were statistically significant better compared to ZAP-scores for other programs (respectively p=0.015 and p=0.0003) *= p < 0.05 and **= p< 0.001 [27].](/document/doi/10.1515/ijamh-2025-0113/asset/graphic/j_ijamh-2025-0113_fig_005.jpg)

Diagram illustrating satisfaction with the program. Each category was compared to similar assessments described in the literature. A value of 100 % represent the maximum possible score for each category. Satisfaction scores in category “Interaction” and “Organisation” were statistically significant better compared to ZAP-scores for other programs (respectively p=0.015 and p=0.0003) *= p < 0.05 and **= p< 0.001 [27].

Discussion

TOC-programs are crucial in preventing the loss of follow-up of pediatric patients during their transfer to adult care, reducing the risks associated with unmanaged chronic symptoms and reducing healthcare costs [28], 29].

In our study we identified several key aspects of TOC for patients with gastrointestinal congenital malformations, emphasizing both challenges and achievements. Patients in our cohort reported significantly lower mental health well-being and gastrointestinal quality of life compared to healthy controls. These findings reflect the chronic burden faced by these patients and emphasize the necessity comprehensive transitional care programs to address the complexity of their conditions. Our results are consistent with long standing evidence of low menlat health in this population, according a recent multicentric study, in which patients with ARM and HD were interviewed from 11 to 26 years [30]. The authors reported on a spectrum of challenges extending beyond the pathology itself, including profound physical, mental and emotional impacts, effects on family dynamics, concerns about future relationships and careers [30]. These findings emphasize the several challenges faced by adolescents with congenital gastrointestinal conditions, reinforcing the need for holistic approaches in their care.

Psychological well-being is intricately linked to patients’ overall quality of life, and addressing the complex interplay of physical, mental, and emotional health is necessary. This complexity also enhances the necessity of integrating psychologists as core members of interdisciplinary care teams. Evidence from other studies also supports this approach, pointing to the benefits of a multidisciplinary model in improving patient outcomes [31].

In our TOC- program, we involved an interdisciplinary team, led by a pediatric surgeon and an adult gastroenterologist, the program brings together specialists from various fields to address patients’ diverse medical, surgical and psychological needs. This approach fosters coordinated decision-making and comprehensive care, essential for optimizing outcomes in patients with complex conditions [32]. Although not statistically significant, patients with combined conditions such as EA and ARM showed a promising trend toward improved well-being and gastrointestinal quality of life. These findings suggest that structured, multidisciplinary support programs may be beneficial particularly for patients. However, the limited scope of our analysis, which included only the first two visits and a relatively small number of patients completing the questionnaires, likely contributed to these modest results. Moreover, the integration of psychological care continues to represent a systemic challenge, as emerged from both our findings and the broader studies [33]. Despite national guidelines, such as those in the United States, emphasizing the importance of addressing psychosocial and developmental needs, psychologists are still not consistently integrated into TOC teams [34]. Expanding psychological support within the transition framework is crucial to address the unmet emotional and mental health needs of this population [41].

Our TOC-program demonstrated a significant improvement in patients’ transition competence, with measurable gains in their ability to manage healthcare and navigate adult medical systems between the first and second visit. These results suggest that the program can improve essential self-management skills; however, they must be interpreted with caution, as no statistically significant changes were observed in psychological well-being or gastrointestinal quality of life. Furthermore, our patients expressed high satisfaction with the program, particularly in areas such as interaction, organization, and the structured, patient-centered approach. Finally, although patient satisfaction with our program was high, claims of its superiority over other transition models require additional comparative evidence. Notably, the existing programs have not been directly evaluated using standardized scales or questionnaires. However, the category of “information” received the lowest scores, pointing to a need to improve communication strategies and ensure that patients fully understand their conditions and care plans.

An important element supporting the program’s effectiveness was the early implementation of an interdisciplinary, structured approach, as suggested from north American society of Pediatric Gastroentorology, Hepatology and Nutrition [35]. In our program we additionaly complemented by the involvement of patient and parent support groups. Close interdisciplinary collaboration ensured that adult medicine teams were already familiar with patients’ medical histories from childhood, which in turn facilitated the establishment of a dedicated transition clinic for adolescents during the transition phase. Furthermore, in recent years, contact with patients/parents support groups has become significantly more important for both patients and their parents. The goal of these organizations is to improve treatment quality providing patients and families peer connections, education, and resources to navigate the transition process [36], 37]. Approximately one-quarter of our cohort of patients was referred through patients/parents support groups, emphasizing the fundamental role in disseminating information about the program and creating awareness about the importance of transitional care [38], 39]. These groups not only help patients gain independence but also assist families [40] in adapting to their new roles during the transition [39], 41], ultimately improving outcomes and reducing stress [42].

Despite the implementation of a standardized transition program represents an important initiative, several limitations of our study warrant consideration. Over a 10-year period, 63 of 202 eligible patients participated, and only 20 completed follow-up assessments. This small sample size, corresponding to approximately six patients per year and two patients per year with longitudinal follow-up, necessarily limits the generalizability of our findings. Consequently, any conclusions regarding the overall benefit of the program should be interpreted with caution. Notably, the possibility of selection bias must be acknowledged. It remains unclear whether patients who did not return for follow-up visits were highly satisfied with their initial care and therefore felt no need to continue participation, or conversely, whether they disengaged due to dissatisfaction. Differentiating between these groups was not feasible in the present study.

Furthermore, patients invited from other centres may have had different backgrounds and previous medical experiences, contributing to a mixed starting point for all patients at the beginning of the program. These limitations evidence the complexity of evaluating transition programs and point up the challenges in interpreting our findings.

Conclusions

We presented the outcomes and patient perceptions of the first standardized transition of care program for individuals with congenital gastrointestinal malformations in Germany. Our findings suggest improvements in patients’ transition competence and high levels of satisfaction with the program’s supportive and patient-centered approach. However, given the small sample size and limited follow-up data, these results should be interpreted with caution. While the study emphasizes the potential benefits of structured transition care and the need for broader implementation of standardized programs, further research with larger cohorts and longer follow-up is recomended.

-

Research ethics: yes.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. RK: data collection, paper writing and patients care. LG: data collection and paper writing. SK: organization of the patients. MO: paper writing. AM: data collection. AS: data collection and patients care. JD: data collection and patients care.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: We used ChatGPT (OpenAI) to assist with language editing and improving the clarity in some parts of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: All other authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Uecker, M, Ure, B, Quitmann, JH, Dingemann, J. Need for transition medicine in pediatric surgery – health related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with congenital malformations. Innov Surg Sci. 2022;6:151–60. https://doi.org/10.1515/iss-2021-0019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Sistonen, SJ, Koivusalo, A, Nieminen, U, Lindahl, H, Lohi, J, Kero, M, et al.. Esophageal morbidity and function in adults with repaired esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula: a population-based long-term follow-up. Ann Surg 2010;251:1167–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c9b613.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Taylor, ACF, Breen, KJ, Auldist, A, Catto–Smith, A, Clarnette, T, Crameri, J, et al.. Gastroesophageal reflux and related pathology in adults who were born with esophageal atresia: a long-term follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2007;5:702–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2007.03.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Legrand, C, Michaud, L, Salleron, J, Neut, D, Sfeir, R, Thumerelle, C, et al.. Long-term outcome of children with oesophageal atresia type III. Arch Dis Child 2012;97:808–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-301730.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Davidson, JR, Kyrklund, K, Eaton, S, Pakarinen, MP, Thompson, DS, Cross, K, et al.. Sexual function, quality of life, and fertility in women who had surgery for neonatal Hirschsprung’s disease. Br J Surg 2021;108:e79–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znaa108.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Witvliet, MJ, Petersen, N, Ekkerman, E, Sleeboom, C, van Heurn, E, van der Steeg, AFW. Transitional health care for patients with Hirschsprung disease and anorectal malformations. Tech Coloproctology 2017;21:547–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-017-1656-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Rigueros Springford, L, Connor, MJ, Jones, K, Kapetanakis, VV, Giuliani, S. Prevalence of active long-term problems in patients with anorectal malformations: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum 2016;59:570–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0000000000000576.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Ludman, L, Spitz, L, Kiely, EM. Social and emotional impact of faecal incontinence after surgery for anorectal abnormalities. Arch Dis Child 1994;71:194–200. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.71.3.194.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Depaepe, A, Dolk, H, Lechat, MF. The epidemiology of tracheo-oesophageal fistula and oesophageal atresia in Europe. EUROCAT working group. Arch Dis Child 1993;68:743–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.68.6.743.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Cassina, M, Ruol, M, Pertile, R, Midrio, P, Piffer, S, Vicenzi, V, et al.. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of children with esophageal atresia: a 32-year population-based study including 1,417,724 consecutive newborns. Birt Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2016;106:542–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.23493.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Grasshoff, S. Leitlinien der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kinderchirurgie Anorektale Fehlbildungen. https://register.awmf.org/. [December 2023]. https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/006-002l_S1_Anorektale-Fehlbildungen_2024-04.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Kyrklund, K, Sloots, CEJ, de Blaauw, I, Bjørnland, K, Rolle, U, Cavalieri, D, et al.. ERNICA guidelines for the management of rectosigmoid Hirschsprung’s disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020;15:164. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-020-01362-3.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Davidson, JR, Kyrklund, K, Eaton, S, Pakarinen, MP, Thompson, DS, Cross, K, et al.. Long-term surgical and patient-reported outcomes of Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg 2021;56:1502–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.01.043.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Hartman, EE, Oort, FJ, Aronson, DC, Sprangers, MA. Quality of life and disease-specific functioning of patients with anorectal malformations or Hirschsprung’s disease: a review. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:398–406. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.118133.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Cairo, SB, Chiu, PPL, Dasgupta, R, Diefenbach, KA, Goldstein, AM, Hamilton, NA, et al.. Transitions in care from pediatric to adult general surgery: evaluating an unmet need for patients with anorectal malformation and Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg 2018;53:1566–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.09.021.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Feng, X, Lacher, M, Quitmann, J, Witt, S, Witvliet, MJ, Mayer, S. Health-related quality of life and psychosocial morbidity in anorectal malformation and Hirschsprung’s disease. Eur J Pediatr Surg Off J Austrian Assoc Pediatr Surg Al Z Kinderchir 2020;30:279–86. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1713597.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Cooley, WC. Adolescent health care transition in transition. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:897–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2578.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Schwartz, LA, Brumley, LD, Tuchman, LK, Barakat, LP, Hobbie, WL, Ginsberg, JP, et al.. Stakeholder validation of a model of readiness for transition to adult care. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:939–46. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2223.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. de Beaufort, CMC, Aminoff, D, de Blaauw, I, Crétolle, C, Dingemann, J, Durkin, N, et al.. Transitional care for patients with congenital colorectal diseases: an EUPSA network office, ERNICA, and eUROGEN joint venture. J Pediatr Surg 2023:S0022346823003688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2023.06.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Sable, C, Foster, E, Uzark, K, Bjornsen, K, Canobbio, MM, Connolly, HM, et al.. Best practices in managing transition to adulthood for adolescents with congenital heart disease: the transition process and medical and psychosocial issues: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2011;123:1454–85. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182107c56.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Giuliani, S, Grano, C, Aminoff, D, Schwarzer, N, Van De Vorle, M, Cretolle, C, et al.. Transition of care in patients with anorectal malformations: consensus by the ARM-net consortium. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1866–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.06.008.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Dingemann, J, Szczepanski, R, Ernst, G, Thyen, U, Ure, B, Goll, M, et al.. Transition of patients with esophageal atresia to adult care: results of a transition-specific education program. Eur J Pediatr Surg Off J Austrian Assoc Pediatr Surg Al Z Kinderchir 2017;27:61–7. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1587334.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Harhuis, A, Cobussen-Boekhorst, H, Feitz, W, Kortmann, B. 5 years after introduction of a transition protocol: an evaluation of transition care for patients with chronic bladder conditions. J Pediatr Urol 2018;14:150.e1–e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.09.023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Topp, CW, Østergaard, SD, Søndergaard, S, Bech, P. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84:167–76. https://doi.org/10.1159/000376585.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Eypasch, E, Williams, JI, Wood-Dauphinee, S, Ure, BM, Schmulling, C, Neugebauer, E, et al.. Gastrointestinal quality of life index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg 1995;82:216–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800820229.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Herrmann-Garitz, C, Muehlan, H, Bomba, F, Thyen, U, Schmidt, S. [Conception and measurement of health-related transition competence for adolescents with chronic conditions - development and testing of a self-report instrument]. Gesundheitswesen Bundesverb Arzte Offentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes Ger 2017;79:491–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1549986.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Bitzer, EM, Bitzer, E, Dierks, M, Schwartz, R. AP-Fragebogen zur Zufriedenheit in der ambulanten Versorgung. Qualität aus Patientensicht. Medizinische Hochschule Hannover 1999. http://www2.mh-hannover.de/1608.html [Accessed 03 Sep 2007].Suche in Google Scholar

28. McDonagh, JE, Viner, RM. Lost in transition? Between paediatric and adult services. BMJ 2006;332:435–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7539.435.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Bloom, SR, Kuhlthau, K, Van Cleave, J, Knapp, AA, Newacheck, P, Perrin, JM. Health care transition for youth with special health care needs. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2012;51:213–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Rajasegaran, S, Chandrasagran, RA, Tan, SK, Ahmad, NA, Lechmiannandan, A, Sanmugam, A, et al.. Experiences of youth growing up with anorectal malformation or Hirschsprung’s disease: a multicenter qualitative in-depth interview study. Pediatr Surg Int 2024;40:119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-024-05709-w.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Vilanova-Sanchez, A, Halleran, DR, Reck-Burneo, CA, Gasior, AC, Weaver, L, Fisher, M, et al.. A descriptive model for a multidisciplinary unit for colorectal and pelvic malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:479–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.04.019.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. McManus, M, White, P, Barbour, A, Downing, B, Hawkins, K, Quion, N, et al.. Pediatric to adult transition: a quality improvement model for primary care. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2015;56:73–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Giuliani, S, Anselmo, DM. Transitioning pediatric surgical patients to adult surgical care: a call to action. JAMA Surg 2014;149:499–500. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4848.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Izumi, BT, Schulz, AJ, Israel, BA, Reyes, AG, Martin, J, Lichtenstein, RL, et al.. The one-pager: a practical policy advocacy tool for translating community-based participatory research into action. Prog Community Health Partnersh Res Educ Action 2010;4:141–7. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.0.0114.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Vittorio, J, Kosmach-Park, B, King, LY, Fischer, R, Fredericks, EM, Ng, VL, et al.. Health care transition for adolescents and young adults with pediatric-onset liver disease and transplantation: a position paper by the North American society of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2023;76:84–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000003560.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Hilderson, D, Eyckmans, L, Van der Elst, K, Westhovens, R, Wouters, C, Moons, P. Transfer from paediatric rheumatology to the adult rheumatology setting: experiences and expectations of young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:575–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-012-2135-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Bomba, F, Herrmann-Garitz, C, Schmidt, J, Schmidt, S, Thyen, U. An assessment of the experiences and needs of adolescents with chronic conditions in transitional care: a qualitative study to develop a patient education programme. Health Soc Care Community 2017;25:652–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12356.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Moons, P, Pinxten, S, Dedroog, D, Van Deyk, K, Gewillig, M, Hilderson, D, et al.. Expectations and experiences of adolescents with congenital heart disease on being transferred from pediatric cardiology to an adult congenital heart disease program. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2009;44:316–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.11.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Bratt, EL, Burström, Å, Hanseus, K, Rydberg, A, Berghammer, M, On behalf on the STEPSTONES-CHD consortium. On behalf on the STEPSTONES-CHD consortium. Do not forget the parents-Parents’ concerns during transition to adult care for adolescents with congenital heart disease. Child Care Health Dev 2018;44:278–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12529.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Obed, M, Kiblawi, R, Schneider, AS, Dingemann, J. Organization of follow-up and transition of patients with gastrointestinal malformations. Hannover: Monatsschr Kinderheilkd; 2023:518–26 pp.10.1007/s00112-023-01755-1Suche in Google Scholar

41. Betz, CL, Coyne, IT. Transition from pediatric to adult healthcare services for adolescents and young adults with long-term conditions. Cham: Springer; 2020:P336 p.10.1007/978-3-030-23384-6Suche in Google Scholar

42. Moons, P, Bratt, EL, De Backer, J, Goossens, E, Hornung, T, Tutarel, O, et al.. Transition to adulthood and transfer to adult care of adolescents with congenital heart disease: a global consensus statement of the ESC association of cardiovascular nursing and allied professions (ACNAP), the ESC working group on adult congenital heart disease (WG ACHD), the association for European paediatric and congenital cardiology (AEPC), the pan-African society of cardiology (PASCAR), the Asia-Pacific pediatric cardiac society (APPCS), the inter-American society of cardiology (IASC), the cardiac society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ), the international society for adult congenital heart disease (ISACHD), the world heart federation (WHF), the European congenital heart disease organisation (ECHDO), and the global alliance for rheumatic and congenital hearts (global ARCH). Eur Heart J 2021;42:4213–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab388.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2025-0113).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Interdisciplinary transition of care for congenital gastrointestinal malformations: analysis of a standardized program

- Mental Health and Well-being

- The impact of family function as a moderating variable on the association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and behavioral problems in male adolescents aged 10–17 Years in Indonesia

- Association between nutritional status and cognitive function scores of adolescent girls in underprivileged communities

- Nutrition, Eating Behaviours, and Body Image

- Nutritional status of adolescents undergoing tuberculosis treatment in urban Bangladesh: prevalence and determinants of malnutrition

- Association between omega-3 fatty acid intake and ADHD symptoms among early adolescents aged 10–12 years: a cross-sectional study in Palestine

- Demographic and clinical characteristics of adolescent patients with eating disorders before and during the Covid-19 pandemic

- The role of nutrition in maintaining health and physical activity among adolescents assigned to special medical groups

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- Parental perspectives: a mixed method study on perceived risk, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy, and willingness for adolescent HPV vaccination in Puducherry, South India

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Chronic Illness and Transition to Adult Care

- Interdisciplinary transition of care for congenital gastrointestinal malformations: analysis of a standardized program

- Mental Health and Well-being

- The impact of family function as a moderating variable on the association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and behavioral problems in male adolescents aged 10–17 Years in Indonesia

- Association between nutritional status and cognitive function scores of adolescent girls in underprivileged communities

- Nutrition, Eating Behaviours, and Body Image

- Nutritional status of adolescents undergoing tuberculosis treatment in urban Bangladesh: prevalence and determinants of malnutrition

- Association between omega-3 fatty acid intake and ADHD symptoms among early adolescents aged 10–12 years: a cross-sectional study in Palestine

- Demographic and clinical characteristics of adolescent patients with eating disorders before and during the Covid-19 pandemic

- The role of nutrition in maintaining health and physical activity among adolescents assigned to special medical groups

- Adolescent Rights, Participation, and Health Advocacy

- Parental perspectives: a mixed method study on perceived risk, self-efficacy, vaccine response efficacy, and willingness for adolescent HPV vaccination in Puducherry, South India