Managing the monthly: a mixed methods study on menstrual waste management among adolescent girls from South India

-

Remya Mary John

, Gomathi Ramaswamy

, Chandralekha Kona

Abstract

Objectives

This study assessed the perceptions and practices of menstrual waste management (MWM) and explored the associated facilitators and barriers in schools of Yadadri-Bhuvanagiri district, Telangana, India.

Methods

A mixed-method approach was adopted. A cross-sectional survey was done among adolescent girls and in-depth interviews among the school teachers from seven schools.

Results

Of the total 394 adolescent girls included in the study, 96.5 % used disposable sanitary pads, with 95 % disposing of them in waste bins at schools, which were incinerated, burnt in open places or buried deep. From the in-depth interviews conducted among the teachers, cultural beliefs, inadequate infrastructure, and limited awareness about reusable menstrual products emerged as significant barriers for safe MWM practices. Non-availability of sanitary workers, electricity fluctuations affecting incineration, and the lack of structured educational materials were some of the challenges that emerged from the in-depth interview. Facilitators for MWM included teacher engagement, availability of dustbins, and support from health workers.

Conclusions

The findings underscore the need for focused interventions, such as sustainable disposal solutions, education on MWM, and community involvement, to improve menstrual waste management among adolescents.

Background

India is home to the largest adolescent female population, estimated at approximately 253 million, with every fifth person between 10 and 19 years old [1]. With this significant proportion of females in menstruating age, menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is a pivotal concern, significantly impacting their health and education. MHM encompasses a spectrum of practices and resources imperative for the safe and comfortable management of menstruation, encompassing access to menstrual products, sanitation facilities, educational initiatives, and proper waste disposal strategies [2].

The landscape of menstrual hygiene products has undergone notable evolution, offering diverse options for managing menstruation with comfort and hygiene. Traditional single-use disposable products such as sanitary pads and tampons have expanded to include innovative and reusable alternatives like menstrual cups, period panties, reusable cloth pads, and menstrual discs, catering to varying preferences and needs. The single-use disposable sanitary pads are made of 90 % plastic; each pad contributes to 2 g of plastic and the tampons, which are almost 100 % plastic, have 2–3 g of plastic [3]. These plastics take around 500–800 years to degrade, which is one of the significant threats to the environment, and these materials remain as microplastics till its complete degradation.

The National Family Health Survey – 5 (NFHS-5, 2019–21), India reports that among women aged 15–24 years, 64 % used single-use disposable sanitary pads. Over 5 years, single-use disposable sanitary pads increased by 20 percent in India (single-use disposable sanitary napkin use in NFHS 4 (2014–15) – 44 %) [4], 5]. As per the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) data, within India’s municipal solid waste context (62 million tons), sanitary waste constitutes approximately 3–4 %, amounting to 1.86–2.48 million tons [6], 7]. On average, each woman uses eight single-use disposable sanitary pads for every menstrual cycle in India [2]. Considering 353 million women aged 15–49 years, 64 % usage of single-use disposable sanitary pads, and eight pads per cycle, 1807 million used sanitary waste pads will be produced in a month and 21,688 million pads in a year. Considering 2 g of plastic in each sanitary pad, 3,614 million grams of plastic in a month and 52,051 million grams of plastic in a year will be generated from menstrual waste in India. Menstrual waste is generally disposed of with general waste at home and treated in a similar way as domestic waste, posing a threat as source of infection. Owing to their slow degradation rate in landfills and oceans, further compounded by the potential leaching of toxic chemicals into soil and water sources and increasing the overall carbon footprint when disposed of improperly.

The Government of India has taken significant steps to address this issue. Initiatives such as Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP), Misson Shakti, Samagra Shiksha are implemented in India to generate awareness among adolescent girls regarding menstrual hygiene. According to Health Management and Information System reporting (HMIS), 34.5 lakh adolescent girls were provided napkin packs in 2021–22, and around 44.85 lakh adolescent girls received in 2022–23 [8]. Oxo-biodegradable sanitary pads ‘Suvidha’ are available at Rs. 1/- per pad in Jan Aushadhi Kendra [9]. While the use of safe and hygienic menstrual products has improved substantially over the years, the safe disposal of menstrual products remains a challenge.

The challenge remains even more serious in schools where a large adolescent population spends most of their daytime, and a significant amount of sanitary waste is generated daily. Adolescent girls are mostly given advice or counselling regarding menstrual hygiene at schools but seldom about proper waste disposal. Very few studies explore the menstrual waste disposal practices followed in schools and homes by the adolescent population. Hence, we planned this study to assess the perceptions and practices regarding menstrual waste management (MWM) among adolescent girls and to explore the facilitators and barriers for MWM at schools in Yadadri –Bhuvanagiri district of Telangana, India.

Data and methods

In this cross-sectional study, we followed a mixed-method approach to collect the data. We adopted a quantitative approach to determine the perceptions and practices regarding MWM among the adolescent girls in the 8th, 9th, and 10th classes. We followed a qualitative approach to explore the facilitators and barriers for MWM at schools and included school teachers as study participants. The study was conducted in government and private schools of Bommalaramaram Mandal in Yadadri Bhuvangiri district of Telangana. Telangana is one of India’s newly formed states (2014), with a population of 3,50,03,674 across 33 districts. Yadadri Bhuvanagiri district of Telangana has a population of 7,70,833 and has 17 administrative mandals. Bommalaramaram is one of the 17 Mandals in the Yadadri Bhuvanagiri district and has a population of 37,248. Ten government and one private school offer high school education in this Mandal. We included six government schools (two residential and four non-residential) and one private school (non-residential) in our study, as the remaining four government schools have a student strength of<45. Institute ethics committee approval was obtained for this study (IEC Number: AIIMS-BBN/IEC/2021/Feb/010). We collected data from October 2022 to August 2023 from the eligible study participants after obtaining informed assent from the adolescent girls and consent from the teachers. Adolescent girls who did not attain menarche or were absent on the day of the visit were excluded. For qualitative interviews, we included only the teachers who had worked in the same schools for at least the last 2 years.

Sample size

The study conducted by Veleshala et al., [10] in the Nalgonda district of Telangana, India, reported that 69.6 % of urban slum girls disposed of menstrual waste products in the dustbins or via burning, which are considered to be relatively safe practices, as suggested by the Central Pollution Control Board, Government of India, for rural areas. Assuming similar 69.6 % of safe disposal practices among rural adolescents, 80 % power, 10 % relative precision, 2 % design effect (to adjust for the cluster effects of the schools) and 95 % confidence interval, we needed 340 adolescent girls to understand the menstrual waste disposal practices. Considering a 10 % non-response rate, we calculated a sample size of 380 girls.

To explore the facilitators and barriers to MWM at schools, we conducted in-depth interviews (IDIs) among female teachers of the selected schools. The total number of IDIs was decided based on the level of information saturation.

Data collection

Three experts from public health (two faculty) and obstetrics and gynaecology (one faculty) conducted content validation of the questionnaires. The questionnaire was then pre-tested and distributed for self-administration by adolescent girls. The doubts regarding the questions were explained by the investigators to the adolescent girls and they were requested to sit separately while answering to avoid peer influence on the response.

We followed purposive sampling for IDIs and identified teachers who were vocal and involved in managing or educating adolescent girls regarding MHM. The investigator trained in qualitative research, conducted the IDIs in the local language (Telugu), and an interview guide was used to facilitate the discussion. The audio of the IDIs was recorded with consent, and these recordings were transcribed to English within 24 hours of each IDI.

Data entry and analysis

The quantitative data were entered into the EpiCollect5 mobile application and analyzed in Stata Version 18.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA) software. The categorical variables were summarized as percentages, and continuous variables were summarized as mean (SD) or median (IQR) based on the distribution of the data. Thematic analysis with inductive coding was done in ATLAS.ti software to identify the themes and categories to explore the current practices, cultural beliefs, challenges, and solutions for MWM in schools. The transcript documents were imported to ATLAS.ti, and two investigators coded them to reduce individual subjectivity and improve the credibility of the coding process. The disagreements regarding the categorization and coding between the investigators were resolved through discussions.

Results

In total, 394 adolescent girls were included in the study. The mean (SD) age of the girls was 14.2 (1.4) years. About 43 % of the adolescent girls were in class 10, and 61.4 % were living in a joint family. The majority of the mothers of the girls did not have any formal education (43.9 %), and only 3 % were graduates. More than half of the adolescent girls (58.9 %) had at least one female sibling (Table 1).

Socio-demographic characteristics and menstrual waste management pattern among the adolescent girls studying in high schools of Bommalaramaram mandal, Telangana, India.

| Characteristics | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 394 | (100) |

| Age in years mean (SD) | 14.2 | (1.4) |

| Class | ||

| Class 8 | 100 | (25.4) |

| Class 9 | 125 | (31.7) |

| Class 10 | 169 | (42.9) |

| Family type | ||

| Joint | 242 | (61.4) |

| Nuclear | 130 | (33.0) |

| Three generation | 22 | (5.6) |

| Age of menarche in years mean (SD) | 12.4 | (1.1) |

| Education of mother | ||

| No formal education | 173 | (43.9) |

| Primary schooling | 57 | (14.5) |

| Middle schooling | 45 | (11.4) |

| High school and above | 119 | (30.2) |

| Female sibling | ||

| No | 162 | (41.1) |

| Yes | 232 | (58.9) |

| Menstrual product used | ||

| Single-use disposable sanitary pad | 380 | (96.5) |

| Others | 14 | (3.5) |

| Number of single-use sanitary pad used/day mean (SD) | 3 | (1.2) |

| Mode of menstrual waste management at home | ||

| Gram panchayat solid waste disposal bin | 341 | (86.6) |

| Local incineration | 32 | (8.1) |

| Othersa | 21 | (5.3) |

| Mode of menstrual waste management at school | ||

| Waste disposal bin available at school | 373 | (94.7) |

| Others | 21 | (5.3) |

| Awareness on menstrual waste management (n=290) | ||

| Prevention of infection | 121 | (41.7) |

| Personal cleanliness | 150 | (51.7) |

| Environmental safety | 10 | (3.5) |

| Others | 9 | (3.1) |

| Challenges in menstrual waste disposal (n=331) | ||

| No | 301 | (90.9) |

| Yes | 30 | (9.1) |

-

aThrow into latrines −3, not answered:2.

Around 96 % of the adolescent girls used single-use disposable sanitary pads, with a mean (SD) utilization of 3 (1.2) pads per day. The remaining small proportion (3.5 %) of adolescent girls used cloth-based menstrual products, but only half (1.2 %) preferred to dry these products openly under the sun after washing.

Menstrual waste management at home and school

The majority of the adolescent girls (86.6 %) disposed of their menstrual waste along with other solid waste from home, which was collected by the Gram Panchayat solid waste collection team. These bins are emptied by the waste collectors authorized by the local body on a daily or alternate-day basis. Around eight percent of adolescent girls followed local incineration at home; the rest threw the menstrual waste in open areas, canals, or buried near their homes. At schools, most participants (95 %) disposed of their menstrual waste in the disposal bin available at school, and the rest (5 %) said they threw the menstrual waste in open areas. When asked about the ideal way to dispose of menstrual waste, 63.1 % of adolescent girls said dustbin followed by burying (17 %). Only 2.9 % said burning is the ideal way of disposal of menstrual waste. Around 9 % of adolescent girls said flushing in latrines, 7 % said throwing in water bodies like lakes and rivers, and 1 % said throwing menstrual waste in open areas was the ideal method.

Nine percent of adolescent girls mentioned that they faced challenges while disposing of their menstrual waste, such as the non-availability of separate dustbins, separate washrooms, and sanitary workers at schools, and emotional apprehension due to the presence of people from the opposite sex at home and school. Around 10 % reported feeling shy when interacting with people of the opposite gender in school and at home regarding menstruation and mentioned it as a challenge.

Only 27.4 % of adolescent students were aware of menstruation prior to their menarche. The main source for their information was their mother (69.2 %) followed by female siblings (19.5 %). Around 57 % of the participants reported having their menstrual cycles regularly; 16.8 % had irregular cycles, while 24.4 % reported occasional irregular cycles.

Around one-third of the adolescent girls said they use soap to clean their genitalia, while 60 % responded that they use only water during menstruation. A small proportion (2.7 %) of adolescent girls mentioned using disinfectants like Dettol. Around 78 % of the adolescent girls mentioned that they wash their external genitalia every time they use the restroom, and the remaining wash while taking a bath or changing their menstrual product.

About 6.4 % of adolescent girls reported having health issues occasionally while using single-use disposable sanitary pads, such as white discharge, pruritus genitalia, bad odour, burning micturition, and pain in the abdomen. Around one-third of adolescents (33.5 %) reported sickness absenteeism in the past owing to the menstrual cycle associated with abdominal pain, heavy bleeding, or as per instructions from their mother.

Regarding questions related to cultural beliefs, 55.3 % were not allowed to participate in religious rituals, 17.6 % said that they were not allowed to go to the temple, around 4 % mentioned that they should not enter or touch anything in the kitchen, nor are they allowed to go outside the house during menstruation (1.0 %). The remaining 24 % reported not following any cultural practices, specifically during menstruation.

Findings from qualitative data

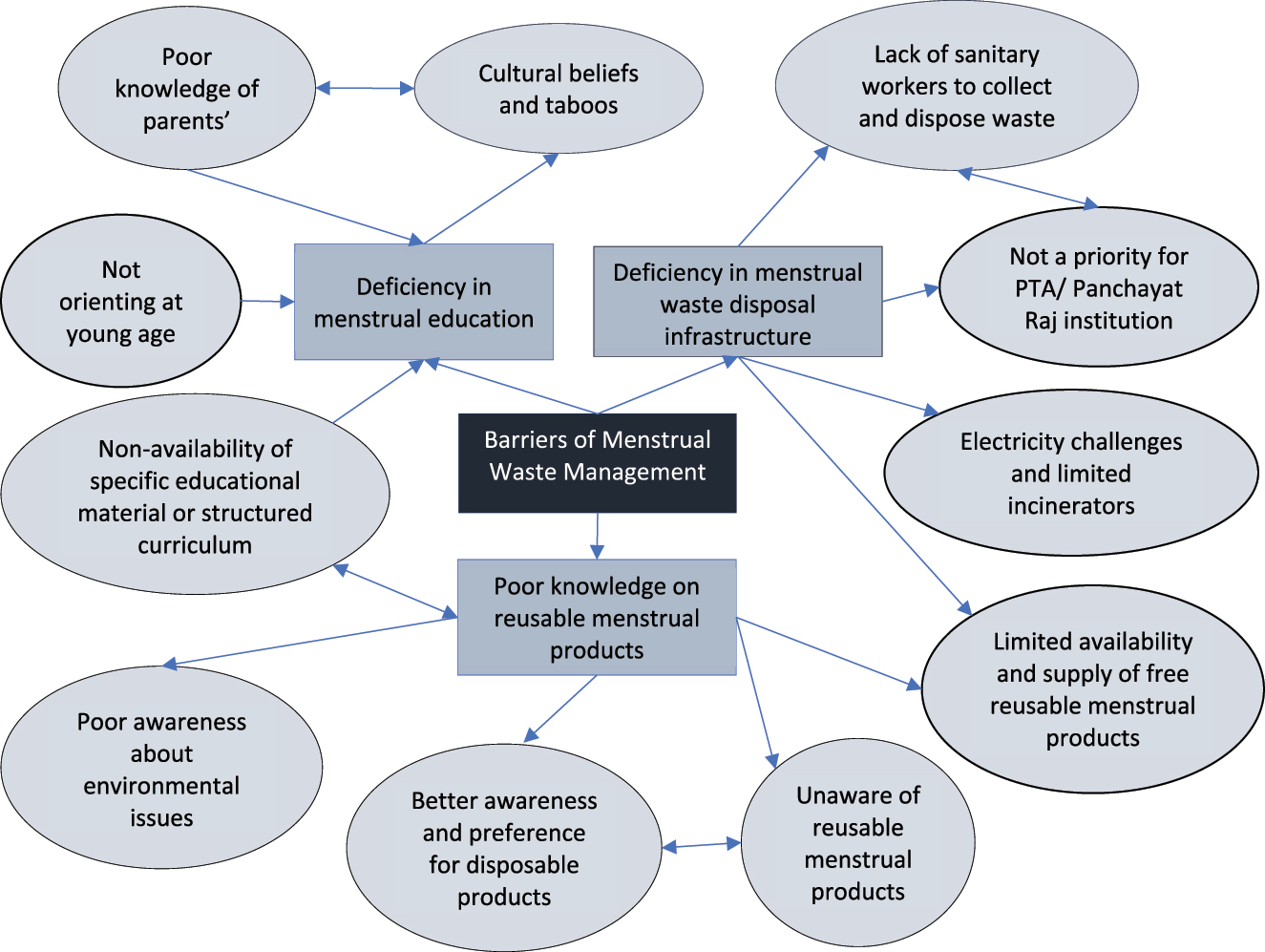

We conducted five IDIs among the teachers from the schools (two from residential government schools, two from non-residential government schools, and one from a private school) included in the study. Figure 1 provides the conceptual diagram derived from thematic analysis related to barriers in menstrual waste management at schools as perceived by the teachers. In total, 77 codes were generated, and they were grouped into 11 categories, three subthemes, and one theme – barriers of menstrual waste management. Three subthemes were, viz., deficiency in menstrual waste disposal infrastructure, deficiency in menstrual education, and poor knowledge on reusable menstrual products.

Barriers related to education about menstrual hygiene: From the codes four categories were derived viz., non-availability of specific educational material or structured curriculum, poor knowledge of parents, not orienting children at young age and cultural beliefs and taboos.

Conceptual diagram on barriers in appropriate menstrual waste management among school children as perceived by the teachers.

The following sections explain the barriers to menstrual hygiene-related education.

Nonavailability of specific educational materials or structured curriculum: The teachers felt that menstrual hygiene education is very limited for adolescents, as no specific curriculum or structured educational material is available at the schools. The teachers expressed that they speak to adolescents about menstrual hygiene during school assemblies (in girls-only schools) or during reproductive health classes and to needy students based on their knowledge and experience.

T2: “No separate (menstrual hygiene and safe disposal) session is there, but during the lessons (reproductive health), the teachers will explain about menstrual hygiene”

T3: “We have topics regarding reproductive cycle, at that time we discuss about menstrual hygiene”

T1 (girls-only residential school): “Yes, we tell them during morning prayer hours, about regularly changing pads every 6 hourly, proper disposal to avoid difficulty for others, etc”

Not orienting at a young age and poor knowledge of parents: Most of the teachers felt that students who attain menarche at early age do not take responsibility for menstrual hygiene due to their young age. Such young age students keep sanitary pads on washroom walls or throw them outside without wrapping them in the newspaper. Although teachers create awareness through lectures and demonstrations, these students find maintaining hygiene practices in school washrooms difficult. Teachers opined that girls should be oriented at a young age regarding menstrual hygiene and appropriate menstrual waste disposal techniques.

T3 (girls-only residential school): “Yes, we do face some issues like children who are young and new to menstruation will not dispose of the waste properly.”

Teachers felt that instead of teachers, parents should be educating their children regarding menstrual hygiene, as teachers felt that the girls were not listening to them. Paradoxically, the teachers also mentioned that the parents wanted teachers to teach their children about menstrual hygiene.

T5: “When the teacher explains, they (girls) will not listen sometimes. My personal opinion is the parents should talk to the girls regarding menstrual hygiene and menstrual waste disposal”

T3: “Parents request us to explain to their girls regarding menstrual hygiene”

T5: “Parents should be taken classes first regarding menstrual hygiene and disposal than students”

Cultural beliefs and taboos: Teachers mentioned that some parents do not agree to burn the menstrual wastes of their children and also do not agree to send their girl children to school especially during their initial few cycles after menarche due to their beliefs and myths.

T1: “Many of them here are illiterate and belong to ST (scheduled tribe caste) from Thanda’s (tribal hamlet). Parents believe and tell us that pads should not be burnt. If it is burnt our children will face childbirth difficulties.”

T5: “A few parents also tell us not to send their children out on New Moon Day during their menstrual cycle. We conduct campaigns to explain that these myths are not true and motivate the children to tell their parents as well. But there are a few parents who will not agree with us.”

T3 (residential girls-only school): “They don’t send the girls to school during the first and second day of menstruation. Remaining days they will send.”

Barriers related to knowledge on reusable menstrual products: From the codes five categories were derived viz. limited availability and supply of free menstrual products, adolescents unaware of reusable menstrual products, better awareness and preference for disposable products, poor awareness about environmental issues and as mentioned earlier, non-availability of specific structural curriculum.

Limited availability and supply of free menstrual products: The teachers said that the government provides disposable sanitary pads once a year. Some non-governmental organizations and corporate firms also provide such products free of cost to the schools. However, the supply is often once a year. Hence, the teachers are not able to provide sanitary pads to all girls throughout the year. They provide it only to those who need it at school or to those girls who forgot to bring it to school. Most of the girls buy sanitary products from shops from their own pocket. Sometimes, teachers spend their money to buy sanitary products when there is no supply.

T4: “They (Government or NGOs or firms) give a large box once a year. We will give it to those who need it in school only.”

T3: “Sponsors (firms) will provide sanitary pads, if anyone doesn’t get their pads we will give them… not every month, they provide (sanitary pads) every year up to 3–4 huge boxes”

Preference for disposable products and lack of awareness on reusable menstrual products:

The teachers opined that all school girls use single-use disposable sanitary pads and are unaware of reusable cloth pads or any other reusable methods. They perceived that reusable cloth pads are old methods for managing the menstrual cycle and are not preferred nowadays. The teachers are also not aware of any program related to menstrual hygiene.

T1: “No, since the generation has been changing, everyone will have awareness. So, no one will use clothes (as menstrual products). In 2010–11, students who were poor and unable to afford sanitary pads used to get cotton clothes. But later, we created awareness and requested “Whisper” for help, so they provided sanitary pads for one year. From then on, they (girls) continued to use sanitary pads.”

T3 (girls-only residential schools): “No, I don’t have any idea about it (menstrual hygiene-related programs). In the name of the Swachh Bharat program, all children will participate in campus cleaning every Saturday for one hour, they also clean their dormitories and trunk boxes.”

Poor awareness about environmental issues:

In terms of environmental issues related to menstrual products, most of the teachers were concerned about the unpleasant smell and unsightly appearance associated with the improper disposal of menstrual products. Some also mentioned that there will be a nuisance from pigs, dogs, and rats if the menstrual waste is not disposed of properly. However, there was no further expression related to other environmental problems associated with menstrual waste.

T4: “Yes, there are some cases where we get bad smell due to improper and delayed burning (of menstrual wastes).”

T3: “If the dustbin gets filled and if it is there for a long time, it leads to a bad smell”

T1:“We teach them to dispose waste properly, otherwise there are issues with pigs and dogs. Also urinary tract infections are often reported by these students”

Barriers related to menstrual waste disposal infrastructure: Four categories were derived from the codes: lack of sanitary workers to collect and dispose waste, menstrual waste disposal not being a priority for PTA/Panchayat Raj institutions, limited availability and supply of free reusable menstrual products, electricity challenges and limited incinerators.

Lack of sanitary workers to collect and dispose of waste: A few schools did not have any helpers or sanitary workers. In those situations, the teachers dispose of menstrual waste with or without the students’ help. A few teachers reported that the school’s housekeeping staff collects the menstrual waste thrown in the dustbins and disposes of it. They also thought that the government paid less for housekeeping work, so it wasn’t easy to find labor.

T3 – “I expect housekeeping staff should be employed for these kinds of work.”

T4- “We tried to employ housekeeping staff on a contract basis, but who will come for less salary? Even in villages nowadays people don’t do this type of work unless 2000 rupees is paid. Hence, our students are doing it.”

T4: “We want housekeeping staff because now we are doing all these works (disposal).”

MHM is not given priority in parent-teacher meetings, committees, or Panchayat Raj Institutions:

All the teachers opined that menstrual hygiene is not discussed during parent-teacher meetings, and these meetings mainly focus on the student’s academic performance. They also felt that parent-teacher meetings could be a good opportunity to discuss menstrual hygiene and clear misconceptions. Most teachers felt that the parents should be aware of it. The teachers also expressed that Panchayat Raj is not involved in discussing MWM.

T2 – “These things (menstrual hygiene management) are not discussed during parent-teacher meetings. Only administrative issues are discussed. But if any personal problems are mentioned, then we will discuss them.”

T3 – “Meetings are held once a month, but parents attend during vacations like Dusshera, Sankranti, and summer mostly.”

T2 – “We don’t have these (school committee meetings with Panchayat Raj members) often; during Independence Day and Republic Day, they (Panchayat Raj members/ Village leader) visit the school.”

Electricity challenges and non-availability of incinerators:

Most residential schools had electricity-based incinerators, and non-residential schools burned menstrual waste in open places using conventional firewood. However, manpower for such waste disposal was limited, and often, teachers, with the help of the students, carried out the waste disposal activities. Teachers also felt that the challenges with fluctuations in electricity and low-voltage electricity, limiting the usage of incinerators at school.

T2 – (nonresidential school) – “We have an open place behind the school where we will collect the waste (including menstrual waste) and burn it. Since this is not a residential school, we don’t get much waste”

T5 – “We wanted to buy an incinerator for our school through donors, but the electrician told us its maintenance will be difficult as we don’t get enough power supply to run it”

T1 (Residential girls-only school) – “We run the incinerator once in every two days. As they (girls) wrap the waste in the paper, the weight of each menstrual waste will be more and the incinerator gets filled easily, so we have to use it every two days.”

Facilitators

We derived three categories of facilitators from the codes. The facilitators varied based on the residential nature of the school. The categories, codes, and verbatims that facilitated the proper disposal of menstrual waste are explained in Table 2.

Facilitators of appropriate menstrual waste disposal practices among school children as perceived by the teachers from South India.

| Categories | Codes | Verbatims |

|---|---|---|

| Teachers’ engagement |

|

T1(residential girls-only school): Yes, we(teachers) tell them(students) during morning prayer hours about regularly changing pads every 6 h, proper disposal to avoid difficulty for others, etc.

T5: Yes, ANM should take classes on menstrual hygiene. Local medical officers will also take classes on anemia, and personal and menstrual hygiene. They also conduct awareness programs on world health day, world population day, and anemic day. |

| Teacher and student relationship |

|

T1: “They (students) will listen to us (teachers). Girls who are in lower 5th and 6th classes don’t know how to dispose of waste, we especially focus on them and train and demonstrate how to properly dispose of the waste.” |

| Infrastructure and manpower |

|

T1: “We have a total of 300 girl students, and there are 3 blocks with 10 washrooms each”

T2: “We have a total of 190 girls and there are 10 washrooms.” T1: “As this is a residential school, incinerator is compulsory. The housekeeping staff will collect the waste from each washroom in a big bag, and they dispose of it in an incinerator” |

| Collaboration with other sectors |

|

T5: “Yes, from the government hospital, staff come to take the classes every 3 months regarding personal hygiene, menstrual hygiene, etc.” T5: “We requested whisper for help, so they provided sanitary pads for 1 year. From then on, they (students) continued to use sanitary pads” |

Discussion

To date, only a few studies have studied MWM practices and the challenges associated with appropriate menstrual waste management at schools in India. Among the 394 adolescent girls who participated in this study, 96.5 % were using single-use disposable sanitary pads, 87 % of them disposed of the menstrual waste in the dustbins at home, and 95 % disposed of it in the dustbins at school. Only a meager proportion of adolescent girls used reusable menstrual products like cloth pads. Our study also captured the school teachers’ perspectives on menstrual waste disposal through in-depth interviews to provide deeper insights into MWM practices at schools. We identified a need for focused menstrual hygiene-related sessions and relevant educational materials, infrastructure for appropriate disposal of menstrual waste, and involvement of parents, healthcare providers, and parent-teacher committees to strengthen MWM activities. There is also minimal knowledge of reusable menstrual products among school children and teachers.

Only one-fourth of the adolescent girls knew about menstruation prior to menarche, and the majority of them gained this knowledge from their mothers or friends, which is similar to the study conducted by Veleshala et al., [10] from the same geographic region as our study. This might be because of the poor educational status of mothers, as around 40 % of the mothers did not have any formal education in our study. However, the majority of adolescents (95 %) used sanitary pads for menstrual hygiene management, with a small percentage using cloth-based pads. This is comparable to studies like Veleshala et al., which reported 96 %, and Chandar et al. [11], which reported 91 % of their study participants utilizing sanitary pads. While the study by Prasad RR et al., [12] from Jaipur, India, reported that only 66.9 % of adolescent girls from urban slums used sanitary pads, and the rest used cloth pads. The reason for the relatively low proportion of disposable sanitary pad use in the study by Prasad et al. [12], might be due to the affordability of disposable sanitary pad, awareness of reusable cloth pads, and availability of such cloth pads. Though some studies report that the usage of disposable sanitary pads are more common in urban areas, our study from rural areas also reported higher usage of single-use disposable sanitary pads, which indicates the need for appropriate disposal mechanisms for these sanitary pads in rural areas as well.

The Government of India launched the Menstrual Hygiene Scheme (MHS) in 2011, which provides subsidized sanitary pads called “Free days” through ASHAs [13], and Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK) in 2014, and the school health program under Ayushman Bharat promotes awareness regarding menstrual health and promotes destigmatization and healthy practices. Swachh Bharat Abhiyan indirectly supports menstrual hygiene by fostering access to toilets, especially for girls in schools, and safe disposal mechanisms for menstrual waste like incinerators and waste bins [14]. However, a gap exists between the programs introduced and the realistic conditions, which need to be addressed and need adoption of sustainable solutions. The solid waste management rules (2016) consider menstrual waste as sanitary waste under solid waste [15]. The conventional single-use disposable sanitary pad with or without superabsorbent polymers (SAP) is mainly non-compostable. The Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India, recommends disposing of menstrual waste in biomedical incinerators (sanitary pads without SAP) or large-scale incinerators (sanitary pads with SAP), which are not available in the majority of rural areas [16]. The MHM guidelines (2015) recommend disposing of single-use disposable sanitary pads by deep burial or burning in a good incinerator [17]. Disposal by pit burning or into a pit latrine is not recommended for single-use disposable sanitary pads. In our study, around 95 % of adolescent girls disposed of their menstrual waste in dustbins at school. In the residential schools, incinerators were available and functional for disposing of menstrual waste. However, in the non-residential schools, the incinerators were either unavailable or not functional due to fluctuations in electricity as reported in our study. Hence, when the incinerator was unavailable, the schools disposed of the menstrual waste by burning it in open spaces. The impact of environmental pollution on school children’s health with this type of practice needs close monitoring because burning such waste at low temperatures could result in the release of carcinogenic toxins – dioxin and furans [17]. Hence, maintaining WHO-recommended high temperatures (850–1,100 °C) while using incinerators and monitoring the gas released by pollution control boards during incinerators are crucial [18]. Though six out of 17 Sustainable development goals (SDG goal 6: Clean water and sanitation; goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities; goal 12: Sustainable consumption and production; goal 13 – Climate action; goal 14 – Oceans, seas, and marine resources and goal 15 – Life on land) directly calls for action for a safe environment, MWM is not explicitly addressed in SDG. The cultural beliefs around burning menstrual waste need to be addressed at the community level.

A meta-analysis conducted by Ejik et al., [19] reported that only around 28 % of adolescent girls from rural areas dispose of their menstrual waste in dustbins, and the rest dispose of it by either throwing it away or burying it. However, in our study, around 87 % of the adolescent girls reported disposal of the menstrual waste in dustbins at home, which are collected along with general solid waste by workers from the village Panchayat and disposed of either by burning or burying in sanitary landfills away from human settlements. Though the practice seems hygienic, the matter of environmental pollution remains unanswered. Commercial sanitary pads require a minimum of 800 years to break down into microplastics [20]. The quantity of microplastics in different levels of the food chain, standardized measurement techniques, and their effect on human health require robust research. From our study, “period poverty” still exists regarding access to adequate private sanitary facilities, comprehensive menstrual education, and environment-friendly disposal practices.

We did not interview the sanitary workers who handle the menstrual waste to get their perspectives on the management of menstrual waste and the associated challenges. We also did not observe the menstrual waste disposal practices directly, and the self-reported data from the participants were reported here. Hence, there is a possibility of social desirability bias with self-reporting from our study. However, the study is a wake-up call for all to be aware of the environmental impact of the non-degradable commercially available disposable sanitary pads and look for hygienic and environmentally safer measures of MHM. Such safer and reusable products are to be made affordable and accessible, and awareness around them is to be generated among adolescents and teachers to ensure a safer Earth for future generations. There is also a need for multisectoral engagement and community involvement, especially around MHM at schools.

Conclusion

In our study, more than 95 % of the adolescents were using single-use disposable pads, and the disposable menstrual wastes were burned in an incinerator in open places or buried at schools. Only a small proportion was aware of and used reusable menstrual products. The awareness of menstrual hygiene was good; however, the understanding of hygiene measures for the disposal of menstrual waste was inadequate. Menstrual Waste Management should be prioritized as a collective responsibility by the parents, teachers, students, and institutions. There is also a need for research on the availability, quality, utility, health complications, socio-cultural acceptability, and environmental pollution of reusable menstrual products.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Mandal education officer who supported us in visiting the schools of the Yadadri- Bhuvanagiri district.

-

Research ethics: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee, AIIMS Bibinagar (IEC Number: AIIMS-BBN/IEC/2021/Feb/010).

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from the class teachers/ local guardians, and assent was obtained from the adolescent girls.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted the responsibility for entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. All the authors were involved in data interpretation and manuscript writing.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw data can be obtained on request from the corresponding author.

-

Paper presentation: The paper was presented in partial in IAPSMCON 2023.

References

1. UNICEF. Adolescent development and participation. UNICEF India. https://www.unicef.org/india/what-we-do/adolescent-development-participation [Accessed 28 October 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

2. World Bank. Menstrual health and hygiene. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/water/brief/menstrual-health-and-hygiene [Accessed 28 October 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

3. Fourcassier, S, Douziech, M, Pérez-López, P, Schiebinger, L. Menstrual products: a comparable Life cycle assessment. Cleaner Environmental Systems 2022;7:100096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cesys.2022.100096.Suche in Google Scholar

4. International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National family health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2017. Available from: https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/library/resource/national-family-health-survey-nfhs-4-2015-16-india/.Suche in Google Scholar

5. International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National family health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019-21: India: volume I. Mumbai: IIPS; 2021. Available from: https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/library/resource/national-family-health-survey-nfhs-5-2019-21-india/.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation (CPHEEO). Swachh bharat mission. In: Municipal solid waste management manual. Part II: the manual. Ministry of Urban Development; 2016. Available from: https://mohua.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/Part2.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Biswas, A, Tewar, S. Sanitary waste management in India challenges and Agenda. New Delhi: Centre for Science and Environment. Available from: www.cseindia.org%2fcontent%2fdownloadreports%2f11282/RK=2/RS=QuFMH3sRQaTDVIffOI.c2Ao1_NA-.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Sabha, L. Government of India ministry of women and child development. https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1714/AU2253.pdf?source=pqals [Accessed 29 October 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

9. Pharmaceuticals & Medical Devices Bureau of India. Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana. https://janaushadhi.gov.in/pmbjb-scheme [Accessed October 29, 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

10. Veleshala, J, Malhotra, VM, Thomas, SJ, Nagaraj, K. An epidemiological study of menstrual hygiene practices in school going adolescent girls from urban slums of Nalgonda, Telangana. Int J Commun Med Public Health 2020;7:196–202. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20195853.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Chandar, D, Vaishnavi, Y, Priyan, S, S, GK. Awareness and practices of menstrual hygiene among females of reproductive age in rural Puducherry – a mixed method study. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2021;33:Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/ijamh-2017-0221/html.10.1515/ijamh-2017-0221Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Prasad, RR, Dwivedi, H, Shetye, M. Understanding challenges related to menstrual hygiene management: knowledge and practices among the adolescent girls in urban slums of Jaipur, India. India J Family Med Prim Care 2024;13:1055–61. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc-1604-23.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Menstrual hygiene Scheme (MHS) : national health mission. https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=3&sublinkid=1021&lid=391 [Accessed on 30 October 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

14. Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. Menstrual-hygiene-management- national guidelines. Government of India; 2015. Available from: https://swachhbharatmission.ddws.gov.in/sites/default/files/Guidelines/Menstrual-Hygiene-Management-Guidelines.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

15. The Gazette of India. Solid waste management rules. In: Ministry of Environment and Climate Change. Government of India; 2016. Available from: https://portal.mcgm.gov.in/irj/go/km/docs/documents/MCGM%20Department%20List/Solid%20Waste%20Management/Docs/Bye%20laws/Solid%20Waste%20Management%20Rules%20-2016.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Central Pollution Control Board. Guidelines for management of sanitary waste. Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, Govt. of India; 2018. Available from: https://cpcb.nic.in/uploads/MSW/Final_Sanitary_Waste_Guidelines_15.05.2018.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Elledge, MF, Muralidharan, A, Parker, A, Ravndal, KT, Siddiqui, M, Toolaram, AP, et al.. Menstrual hygiene management and waste disposal in low- and middle-income countries-A review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2018;15:2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112562.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. World Health Organization. Health-care waste. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste [Accessed 30 November 2024].Suche in Google Scholar

19. Eijk, AMvan, Sivakami, M, Thakkar, MB, Bauman, A, Laserson, KF, Coates, S, et al.. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010290. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010290.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Biju, A. Period product disposal in India: the tipping point. Lancet Reg Health – Southeast Asia 2023;15:100214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100214.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.