Abstract

Objectives

To explore the benefits and drawbacks of pediatric hospitalization of adolescents with anorexia nervosa prior to psychiatric hospitalization.

Methods

Epidemiologic data, anthropometric measures, and vital signs, as well as hospitalization characteristics and outcomes, were collected retrospectively and analyzed for 104 patients aged 12–18 years old.

Results

Pediatric hospitalization prior to psychiatric admission did not result in significant advantages in treatment outcomes. Furthermore, no significant advantages were attributed to long pediatric hospitalization as compared to short hospitalization.

Conclusions

This study suggests that for treating adolescent anorexia nervosa, pediatric hospitalization should be recommended only for immediate correction of urgent and life-threatening physical conditions, with short stays preferred over long pediatric hospitalization.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a complex psychiatric disorder with extensive physical and psychosocial consequences. The disease has one of the highest morbidity and mortality rates amongst psychiatric disorders, is often characterized by co-morbidity with other physical and mental illnesses [1], and its peak occurrence is during adolescence [2], 3]. AN has a chronic course with repetitions and high relapse rates [1].

The etiology of the disorder is complex and multifactorial; however, there is a distinct genetic component [4]. Risk factors include anxiety, perfectionism, cognitive rigidity, and early feeding problems [5] but other known risk factors for eating disorders, such as sexual abuse or assault, have not been specifically established for AN [6]. It seems that knowledge, experience, and understanding of this disorder are suboptimal in many cases, along with a lack of understanding of the associated risks [7].

Epidemiologically, while the general incidence of the disorder has been relatively stable in recent decades, there is evidence of increasing incidence amongst adolescents (under 15 years) and young women [8], 9]. Incidence also increased during the COVID-19 epidemic [10]. Whether these changes were due to earlier onset or diagnosis, the above findings are of great importance for understanding risk factors and establishing early prevention plans for AN. The growing number of incidents is causing a significant increase in hospitalizations and therefore requires more efficient and precise treatment.

In terms of prognosis, the current estimation is that ∼50 % of individuals with AN will attain full recovery, 30 % improve, and 20 % remain with this chronic disorder [11].

Beyond the mortality caused by the disorder, many patients suffer from physical or psychosocial morbidities and thus require high levels of care for their medical or psychological stabilization, such as inpatient or day patient treatment. A study that followed female patients for an extended period of 9–14 years showed that more than 20 % of female patients were unable to support themselves independently [12]. Another study of a large cohort of cases showed poor psychosocial outcomes even at age 35 years [13]. Severe cases of AN require hospitalization, which is a great burden for patients, their families, and the medical system, from both a therapeutic and psycho-social standpoint.

It is important to acknowledge that patients under the age of 15 years are at higher risk than older age groups of hospitalization during the course of the disorder [14]. In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the hospitalization rate of this pediatric age group (e.g., Germany [15] and England [14], 16]). This escalation may be attributed to the higher incidence of AN in recent years (as previously mentioned), increases in its severity, or greater awareness and diagnosis among primary care physicians [17].

Given that the main causes for inpatient treatment are extremely low weight and rapid weight loss, one of the most common treatments required during hospitalization is refeeding [18]. Refeeding is comprised of rapid feeding and physical stabilization with a full menu adjusted by a specialist dietician that includes caloric calculation adjusted for age, gender, weight, and activity level.

In recent years, there has been a debate on the optimal speed of refeeding. On the one hand there are arguments in favor of slower feeding aimed at preventing refeeding syndrome, while on the other hand previous studies have demonstrated rapid improvement in vital indices with a shortening of hospitalization days under a feeding regime with more calories at the beginning of hospitalization as compared to slow feeding [18], 19], without adverse events. This suggests a shorter hospital stay is a favorable course of action.

Different departments use diverse approaches regarding feeding options for girls who refuse to cooperate with the meal plans. In some cases, it is customary to convert food into high-calorie formulas such as Ensure® [18], while in others and at our institution tube feeding is frequently used. It is essential to note that some studies suggest that rapid feeding methods, as detailed above, may harm the interpersonal relationship between the therapist and patient [20].

Weight restoration is a central goal in the hospitalization of patients with AN. Therefore, various variables related to weight have been examined in many studies. For example, BMI calculation at admission for hospitalization and at discharge, reaching a target weight set in the plan at admission, and maintaining a target weight for a specified length of time before discharge [21], 22]. In recent years, research has increasingly concentrated on weight gain during hospitalization, with studies examining the impact of weight gain while hospitalized.

A 2014 RCT study found that rapid weight gain was associated with longer remission [23]. Wales et al. (2016)’s study of 102 hospitalized patients with AN showed a distinct prognostic advantage for patients who had gained weight during a shorter period of time [24].

Pemberton et al. (2013) described how hospitalizations of adolescents with eating disorders are complex with many aspects: physiological, psychological, social, and more. While some patients require treatment that is mainly physiological due to heart rhythm disturbances, electrolyte disturbances, and more, others require treatment focusing on psychological or behavioral aspects [25]. Therefore, some female patients at our institution were admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit, where they receive treatment from a multidisciplinary team. The mainstay of this admission is setting a target weight and establishing an orderly treatment plan to achieve it alongside other therapeutic goals. It should be noted that the psychiatric unit is an open and voluntary inpatient facility which relies on patients’ motivation, and there is no use of feeding tubes, only menus.

However, some patients are first admitted to the pediatric ward, due to urgent physiological needs, for predominantly physiological treatments by a pediatric team. A dietician prepares a menu, after which weight, vital signs, and laboratory tests are closely monitored. The usage of a feeding tube is optional, depending on severity.

Due to significant challenges associated with the pediatric hospitalization of adolescents with eating disorders that are often accompanied by adverse effects and other complications, we aimed to examine the benefits of pediatric hospitalization that preceded hospitalization in a psychiatric inpatient unit that specializes in eating disorders. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the benefits of both short- and long-term pediatric hospitalization prior to psychiatric hospitalization.

Our hypothesis holds that the purpose of hospitalization among adolescents with AN in the pediatric department is primarily to address urgent physical needs, such as bradycardia and arrhythmias, hypoglycemia, various electrolyte disorders, kidney failure, and more. We hypothesized that addressing these needs as quickly as possible and shortening the hospitalization time in the pediatric wards, as compared to longer hospitalizations before transfer to the psychiatric inpatient unit for further treatment, would lead to improved prognosis and reduction of peripheral hospitalization damages. We further hypothesized that patients admitted to the psychiatric department following pediatric hospitalization would have a shorter hospitalization period and better prognosis (in terms of achieving their target weight), as compared to patients referred from ambulatory care.

Methods

Study population and data collection

This study examined admission records and chart reviews of adolescent female patients admitted for treatment of AN, during January 2017–December 2022, to a psychiatric inpatient unit that specializes in eating disorders. Inclusion criteria included: age 12–18 years, being admitted to the hospital with AN, and were either treated ambulatory or admitted to a regular pediatric ward before admission to the psychiatry ward. Exclusion criteria were severe chronic illness and complex psychosocial background.

Among the hospitalized patients, those admitted to the pediatric ward prior to psychiatric hospitalization were hospitalized for acute medical stabilization due to life-threatening conditions, including bradycardia or cardiac rhythm disturbances, electrolyte imbalances, severe hypotension, dehydration, or complete refusal to eat. The decision for pediatric hospitalization was based on these critical medical indications rather than psychiatric severity alone. However, because our data were derived exclusively from psychiatric department records, we cannot determine the precise indication for pediatric admission for each individual patient.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). The procedure included an explanation of the study’s objectives and risks involved. The patients and their families provided written consent.

Measures

Demographic data

Ethnicity, age, age at disorder onset, duration of morbidity, co-morbidities, and number of previous admissions as reported by the patients and their parents on admission and verified against their hospital records.

Anthropometric measures and vital signs

Heart rate, blood pressure, Body mass index (BMI), and weight data were extracted at first measurement on admission, last measurement before discharge, and lowest score during hospitalization. The existence of menstrual period was reported by patients on admission and discharge.

Target weight

Reaching target weight during admission was reported by the medical staff before discharge.

Duration of hospitalization

We examined the duration of hospitalization in both the psychiatric inpatient unit and pediatric ward.

Co-morbidities

We gathered information regarding psychiatric co-morbidities, such as anxiety, depression, and self-harm/suicidal behaviors, as reported by the patients and their parents, and crossed checked these with hospital records. Additionally, we referred to the number of psychiatric medicines taken regularly by the patients.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS for Windows ver. 21 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL) for statistical analysis. To examine differences between the groups with respect to collected data (e.g., vital signs and anthropomorphic signs) and self-reported measures, we conducted a series of t-tests for independent variables or Chi-Square according to the variable type.

We compared two groups of patients: patients previously admitted to a pediatric ward and patients referred directly from any ambulatory care. A significance level of p<0.05 was used for all statistical comparisons.

Results

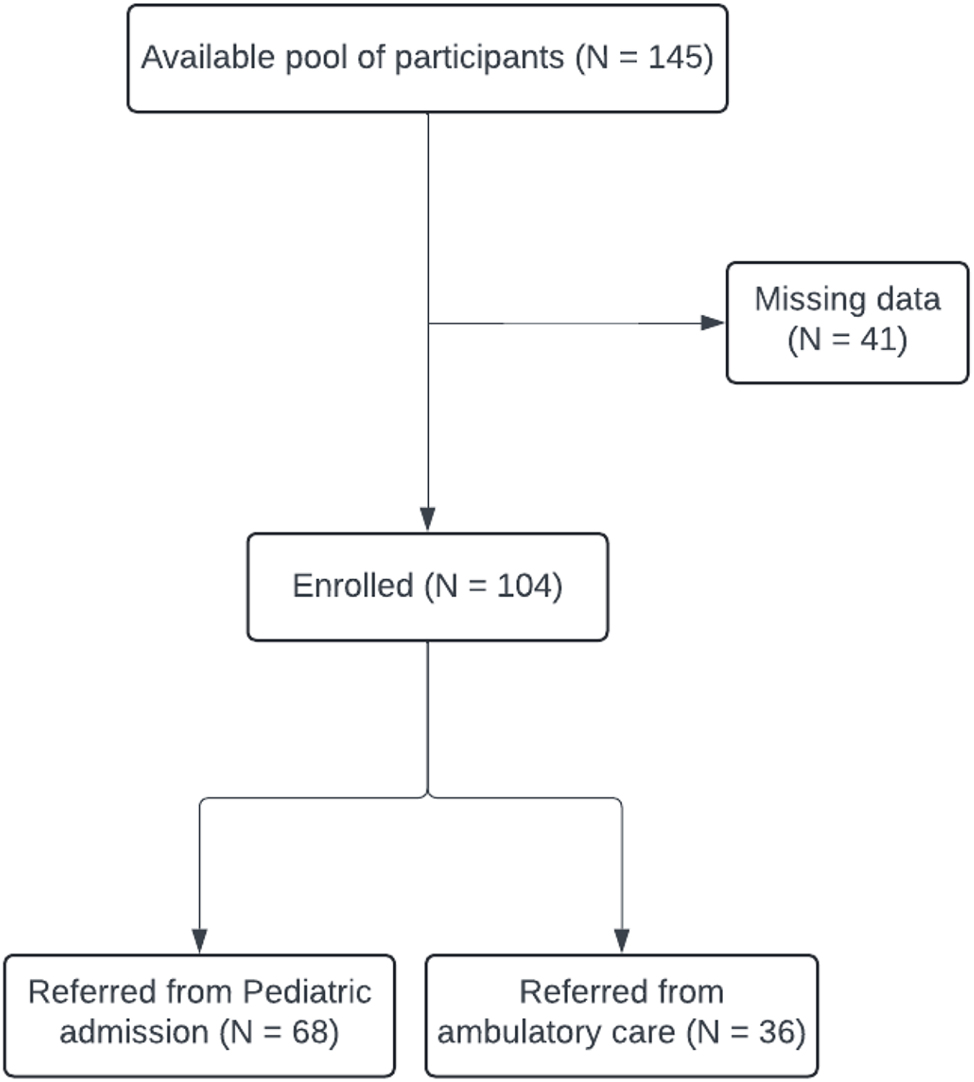

In this retrospective study, 145 patients met our inclusion criteria and 41 were excluded due to missing data (Figure 1). The 104 patients included in the study, aged 12–18 years (M=15.4, SD=1.5), were divided into two main groups: pediatric group with patients previously admitted to a pediatric ward (n=68) and Ambulatory group with patients referred directly from ambulatory care (n=36).

Flow of participants into the study.

T-tests were used to assess differences between the two groups regarding epidemiological variables, weight variables, and vital signs on arrival from the pediatric ward. The results are shown in Table 1.

Differences in variables of weight, vital signs and epidemiology collected at discharge from the pediatric ward (n=104).

| Pediatric (n=68) | Ambulatory care (n=36) | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Age of onset | 13.83 | 1.52 | 13.79 | 1.47 | 0.13 |

| Duration of morbidity | 15.00 | 12.11 | 19.89 | 10.94 | −1.99a |

| Previous admissions | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 3.86b |

| Age of hospitalization | 15.31 | 1.48 | 15.50 | 1.60 | −0.58c |

| HR_FIRST | 78.49 | 14.01 | 77.18 | 12.58 | 0.44 |

| HR_LAST | 83.18 | 15.38 | 83.32 | 13.30 | −0.04 |

| HR_DELTA | 4.44 | 15.24 | 6.19 | 16.34 | −0.50 |

| HR-LOWEST | 69.96 | 12.59 | 68.15 | 12.31 | 0.66 |

| BP% SYS FIRST | 106.00 | 10.38 | 105.15 | 12.01 | 0.35 |

| BP% SYS LAST | 112.59 | 12.82 | 109.64 | 9.32 | 1.13 |

| BP% SYS DELTA | 6.36 | 14.31 | 4.84 | 11.56 | 0.50 |

| BMI% FIRST | 16.97 | 2.37 | 17.47 | 1.97 | −1.03 |

| BMI% LAST | 19.88 | 1.78 | 19.85 | 1.77 | 0.08 |

| BMI% DELTA | 2.85 | 1.76 | 2.37 | 1.89 | 1.21 |

| WEIGHT FIRST | 42.76 | 7.45 | 45.14 | 7.51 | −1.52 |

| WEIGHT LAST | 50.22 | 6.38 | 50.95 | 6.77 | −0.53 |

| WEIGHT DELTA | 7.33 | 4.20 | 5.81 | 4.93 | 1.62 |

-

ap<0.05, bp<0.005, cp<0.001.

No differences were found between the groups with regards to age of onset and age at hospitalization. However, there was a longer mean duration of morbidity in the Pediatric group as compared to the Ambulatory group (15.00 ± 12.11 vs. 19.89 ± 10.94, respectively, p≤0.05). The Pediatric group also had more mean previous admissions than the Ambulatory group (0.87 ± 0.87 vs. 0.32 ± 0.053, respectively, p≤0.001). Regarding vital signs, no significant differences were found between the groups for all the indices tested.

Since the observed trends in variables such as BMI and heart rate changes did not reach statistical significance, we did not conduct further analysis on their potential clinical implications. However, we acknowledge that non-significant trends could still have clinical relevance, and future research with larger sample sizes may be needed to explore these patterns in more depth.

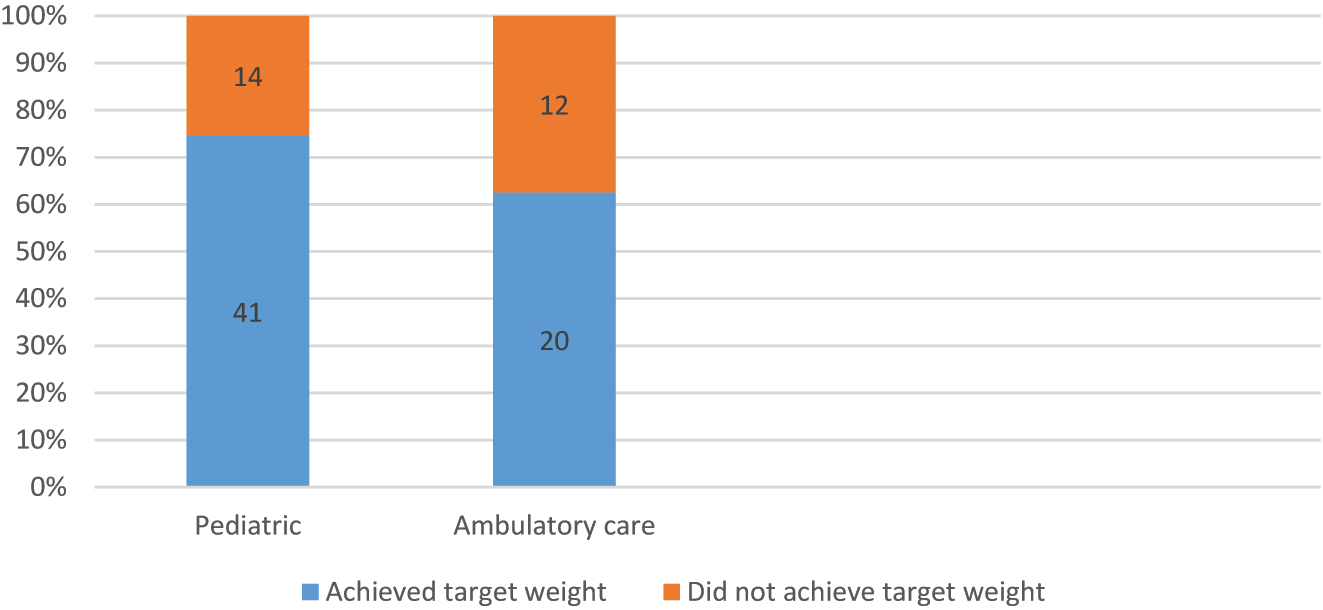

To test the relationship between type of preliminary hospitalization and success in the criterion of reaching the target weight, a chi squared test was conducted and results presented in Figure 2. No significant relationship was found between the groups and achieving target weight.

Correlation between arrival from pediatric and reaching the weight target (n=87).

T tests were used to test for differences in the length of hospitalization, as shown in Table 2. No difference was found between the groups with regards to hospitalization time.

Differences in length of hospitalization according to arrival from pediatric ward (n=102).

| Pediatric (n=68) | Ambulatory care (n=34) | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Length of hospitalization | 127.27 | 66.08 | 104.02 | 74.02 | 1.60a |

-

ap<0.05.

To test the relationship between type of preliminary hospitalization and presence of depression, a chi squared test was conducted. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 3. A significant dependence was found between depression and arrival from the pediatric ward, with a medium-low Cramer’s V coefficient (V=0.23), indicating the group with depression was associated with arrival from the pediatric ward.

Correlation between arrival from pediatric and co-morbidity with depression (n=103).

| Pediatric (n=68) | Ambulatory care (n=35) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (n=69) | 51 | 18 | 5.80a |

| No evidence of depression (n=34) | 17 | 17 |

-

ap<0.05.

To test for differences in the number of psychiatric medications, a t-test was conducted and results presented in Table 4 (see appendix). A significant difference was found in the mean number of psychiatric medications with the Pediatric group prescribed fewer than the Ambulatory group (0.76 ± 0.90 vs. 1.29±0.29, respectively, p≤0.05).

Differences in the number of psychiatric medications according to arrival from pediatric (n=104).

| Pediatric (n=68) | Ambulatory care (n=34) | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Number of psychiatric medications | 0.76 | 0.90 | 1.29 | 1.29 | −2.12a |

-

ap<0.05.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the implications of pediatric hospitalization prior to psychiatric hospitalization in adolescents with AN. We examined adolescents admitted to a psychiatric facility that specializes in eating disorders, where some patients had previously sought treatment in a pediatric ward and others in ambulatory care settings. Specifically, we examined whether pediatric hospitalization is beneficial in achieving target weights and overall treatment outcomes and prognosis as compared to patients who were not previously hospitalized in a pediatric ward.

One of the most interesting findings in this study referred to indicators of success during psychiatric hospitalization for eating disorders, which is achieving a target weight. Our findings yielded no significant difference between the groups regarding the achievement of target weight during psychiatric hospitalization [26].

Although our analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences in certain clinical parameters, such as BMI and heart rate changes, it is important to acknowledge that non-significant trends may still hold clinical relevance. For example, even small differences in weight restoration or vital signs could influence long-term treatment trajectories and overall prognosis. Given the relatively small sample size, it is possible that the study was underpowered to detect subtle yet meaningful differences. Future research with larger cohorts may be better equipped to explore whether these trends represent clinically significant effects that impact treatment outcomes.

According to our hypothesis, our findings indeed demonstrate that the major benefit of pediatric hospitalization was the immediate treatment of life-threatening conditions. The significant weight gain was carried out within the period of psychiatric hospitalization and therefore our findings indicate that preliminary pediatric hospitalization did not have any prognostic effect.

We estimate that one of the reasons for the difficulty in treating eating disorders in pediatric departments is due to the conflict that arises around the need for immediate feeding, either PO or by tube feeding. Assuming that the importance of the therapist-patient relationship is very important for this type of illness [27], it seems imperative to separate the purely physiological treatment from the psychiatric treatment and supportive treatment.

We found that patients required to be hospitalized in a pediatric ward prior to psychiatric hospitalization had been diagnosed with AN for a shorter time than those admitted to psychiatric hospitalization from any ambulatory setting. This may reflect cases in which deterioration is rapid, with insufficient time to start an ambulatory process. In addition, it was found that patients who required pediatric hospitalization had a greater number of past hospitalizations. However, despite these findings, we did not find any significant epidemiological differences between the groups. Patients in both groups were hospitalized at a similar age after being diagnosed at a similar age. In terms of vital indicators (heart rate, blood pressure, weight, and BMI) no significant differences were found between the groups. Also, no significant difference was found in the degree of change between these indices at the beginning of the hospitalization in the psychiatric ward and at discharge. In terms of comorbidities, patients requiring pre-hospitalization in a pediatric ward were diagnosed with depression at similar rates to those not hospitalized in a pediatric ward; however, not due to anxiety or previous attempts at self-harm.

We acknowledge the importance of exploring potential mechanisms underlying our findings. One possible explanation for why pediatric hospitalization did not improve outcomes is the increased psychological stress associated with medical hospitalization. Hospitalization in a pediatric ward often involves strict monitoring, medical interventions (e.g., tube feeding), and loss of autonomy, which could contribute to increased anxiety and resistance to treatment. Additionally, the treatment milieu differs significantly between pediatric and psychiatric units; pediatric wards primarily focus on medical stabilization, whereas psychiatric inpatient settings emphasize behavioral, psychological, and multidisciplinary therapeutic interventions tailored to eating disorders. It is possible that prolonged stays in pediatric wards delay engagement with specialized psychiatric care, limiting opportunities for early therapeutic intervention. Further research is needed to examine how different hospitalization settings impact long-term recovery trajectories in adolescents with AN.

Strength and limits

The strength of this study lies in its real-world clinical relevance, using a comparative cohort design to analyze the impact of pediatric hospitalization vs. direct psychiatric admission in adolescent anorexia nervosa. By leveraging retrospective hospital data, it provides practical, evidence-based insights into treatment efficacy. The study’s robust sample size, statistical analysis, and focus on long-term outcomes make it a valuable contribution to optimizing hospitalization protocols and advocating for more specialized, targeted care in eating disorder treatment.

A limitation of this study is the relatively small size of each study group, which may have affected our ability to fully explore the differences between the groups. It is also important to note that it was difficult to obtain all the information required for certain questions. For example, we were able to reach a clear answer in only 87 patients regarding reaching their target weight. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, it was not always possible to determine whether target weights had been reached.

A limitation of our statistical analysis is that multiple comparisons were performed without applying formal corrections such as Bonferroni adjustments. While we aimed to limit the number of comparisons to reduce the risk of Type I error, we acknowledge that some findings may have occurred by chance. However, given the exploratory nature of the study, we prioritized maintaining statistical power and avoiding overly conservative corrections that could obscure meaningful trends. Future research with larger sample sizes may allow for more rigorous statistical adjustments while preserving analytical sensitivity.

To shed further light on the unique characteristics of pediatric hospitalization with optimal treatment course, we recommend an in-depth examination of the course of the entire pediatric hospitalization. Finally, the retrospective design of the study limited available data and precluded conclusions regarding the beneficial costs of the pediatric hospitalization itself. Longitudinal, prospective studies are recommended for further research in the field and a more precise examination of prognosis.

What is already known on this subject?

Some adolescents with anorexia nervosa are first admitted to pediatric departments due to severe acute medical complications, such as bradycardia, hypoglycemia, and electrolyte imbalances. However, it remains unclear whether pediatric hospitalization contributes to eating disorder recovery or if it merely stabilizes immediate medical risks. The long-term impact of pediatric hospitalization compared to direct psychiatric admission has not been well studied.

What this study adds?

This study provides evidence that pediatric hospitalization does not improve long-term recovery compared to direct psychiatric admission. While hospitalization is necessary for acute medical stabilization, it does not appear to offer additional benefits for achieving weight restoration or reducing relapse. These findings suggest that prolonged pediatric hospitalization may be unnecessary, emphasizing the need for shorter medical stays and earlier transitions to specialized eating disorder units.

Conclusions

This study focused only on psychiatric hospitalization, which provided useful insights into the importance of short pediatric hospitalization. A significant percentage of patients with AN require urgent pediatric hospitalization due to various physiological disorders. Despite the different therapeutic approaches in the pediatric wards, using an optimized menu or feeding with tube in a short or long period of treatment, no significant prognostic benefit (in terms of achieving target weight) was found for pediatric hospitalization over ambulatory care prior to psychiatric hospitalization.

As we found no actual benefits to long pediatric hospitalization over short hospitalization, we assessed hospitalization duration by defining “short” and “long” based on the median hospitalization time, within our cohort. Given the peripheral side effects of long hospitalizations in pediatric wards, we believe that it might prove beneficial to all parties considered to set the goal for as short as possible pediatric hospitalizations combined with a rapid refeeding approach.

In addition, further research is necessary regarding the negative results accompanying long hospitalizations of adolescents with eating disorders, such as deterioration of psychiatric illnesses, social harm, infections, hospitalism, and even deterioration of the eating disorder.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Debby Mir for her assistance in scientific editing.

-

Research ethics: The study protocol was approved by the Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 0468-12-RMC.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study, or their legal guardians or wards.

-

Author contributions: Ziv Bren: Conceived and designed the study, performed data collection and analysis, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. Drafted and revised the manuscript. Amit Goldstein: Contributed to the study design and provided substantial input in the interpretation of results. Assisted with manuscript writing and performed revisions. Orly Lavan: Assisted in study design and contributed to manuscript writing and editing. Provided critical revisions to the manuscript’s methodology section. Silvana Fennig: Responsible for overseeing the project and ensuring ethical compliance. Reviewed and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

-

Research funding: The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

-

Data availability: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Arcelus, J, Mitchell, AJ, Wales, J, Nielsen, S. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:724–31. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Petkova, H, Simic, M, Nicholls, D, Ford, T, Prina, AM, Stuart, R, et al.. Incidence of anorexia nervosa in young people in the UK and Ireland: a national surveillance study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027339. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027339.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Micali, N, Hagberg, KW, Petersen, I, Treasure, JL. The incidence of eating disorders in the UK in 2000-2009: findings from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002646. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002646.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Hinney, A, Volckmar, AL. Genetics of eating disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15:423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0423-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Treasure, J, Russell, G. The case for early intervention in anorexia nervosa: theoretical exploration of maintaining factors. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:5–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.087585.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Wonderlich, SA, Crosby, RD, Mitchell, JE, Thompson, KM, Redlin, J, Demuth, G, et al.. Eating disturbance and sexual trauma in childhood and adulthood. Int J Eat Disord 2001;30:401–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.1101.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Hudson, LD, Cumby, C, Klaber, RE, Nicholls, DE, Winyard, PJ, Viner, RM. Low levels of knowledge on the assessment of underweight in children and adolescents among middle-grade doctors in England and Wales. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:309–11. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2012-303357.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. van Eeden, AE, van Hoeken, D, Hoek, HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr Opin Psychiatr 2021;34:515–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000739.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Javaras, KN, Runfola, CD, Thornton, LM, Agerbo, E, Birgegård, A, Norring, C, et al.. Sex- and age-specific incidence of healthcare-register-recorded eating disorders in the complete Swedish 1979–2001 birth cohort. Int J Eat Disord 2015;48:1070–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22467.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Agostino, H, Burstein, B, Moubayed, D, Taddeo, D, Grady, R, Vyver, E, et al.. Trends in the incidence of new-onset anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2137395. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37395.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Steinhausen, HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatr 2002;159:1284–93. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1284.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Hjern, A, Lindberg, L, Lindblad, F. Outcome and prognostic factors for adolescent female in-patients with anorexia nervosa: 9- to 14-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:428–32. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.018820.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Wentz, E, Gillberg, IC, Anckarsäter, H, Gillberg, C, Råstam, M. Adolescent-onset anorexia nervosa: 18-year outcome. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:168–74. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.048686.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Holland, J, Hall, N, Yeates, DG, Goldacre, M. Trends in hospital admission rates for anorexia nervosa in Oxford (1968–2011) and England (1990–2011): database studies. J R Soc Med 2016;109:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076815617651.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Silber, AS, Platte, S, Kumar, A, Arora, S, Kadioglu, D, Schmidt, M, et al.. Admission rates and clinical profiles of children and youth with eating disorders treated as inpatients before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in a German university hospital. Front Public Health 2023;11:1281363. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1281363.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Wood, S, Marchant, A, Allsopp, M, Wilkinson, K, Bethel, J, Jones, H, et al.. Epidemiology of eating disorders in primary care in children and young people: a Clinical Practice Research Datalink study in England. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026691. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026691.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Demmler, JC, Brophy, ST, Marchant, A, John, A, Tan, JOA. Shining the light on eating disorders, incidence, prognosis and profiling of patients in primary and secondary care: national data linkage study. Br J Psychiatry 2020;216:105–12. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.153.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Garber, AK, Cheng, J, Accurso, EC, Adams, SH, Buckelew, SM, Kapphahn, CJ, et al.. Short-term outcomes of the study of refeeding to optimize inpatient gains for patients with anorexia nervosa: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3359.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. O’Connor, G, Nicholls, D, Hudson, L, Singhal, A. Refeeding low weight hospitalized adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Nutr Clin Pract 2016;31:681–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0884533615627267.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Herpertz-Dahlmann, B. Intensive treatments in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Nutrients 2021;13:1265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041265.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

21. Baran, SA, Weltzin, TE, Kaye, WH. Low discharge weight and outcome in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatr 1995;152:1070–2. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.152.7.1070.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Lay, B, Jennen-Steinmetz, C, Reinhard, I, Schmidt, MH. Characteristics of inpatient weight gain in adolescent anorexia nervosa: relation to speed of relapse and readmission. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2002;10:22–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.432.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Le Grange, D, Accurso, EC, Lock, J, Agras, S, Bryson, SW. Early weight gain predicts outcome in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2014;47:124–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22221.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Wales, J, Brewin, N, Cashmore, R, Haycraft, E, Baggott, J, Cooper, A, et al.. Predictors of positive treatment outcome in people with anorexia nervosa treated in a specialized inpatient unit: the role of early response to treatment. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2016;24:417–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2443.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Pemberton, K, Fox, JR. The experience and management of emotions on an inpatient setting for people with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative study. Clin Psychol Psychother 2013;20:226–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.794.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Hetman, I, Brunstein Klomek, A, Goldzweig, G, Hadas, A, Horwitz, M, Fennig, S. Percentage from target weight (PFTW) predicts Re-hospitalization in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Isr J Psychiatry 2017;54:28–34.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Zugai, JS, Stein-Parbury, J, Roche, M. Therapeutic alliance, anorexia nervosa and the inpatient setting: a mixed methods study. J Adv Nurs 2018;74:443–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13410.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Understanding premenstrual syndrome: experiences and influences among monastir university students

- A cross-sectional study on risk factors of premenstrual syndrome among college-going students in Pune

- Application of psycho-educational intervention to reduce menstrual-related distress among adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial

- Bridging the gap: a study on substance use among the adolescents in a rural area of Jaipur

- Examining the relationship between internet addiction and the willingness to continue living, mediated by life satisfaction and negative suicidal ideation, with depression as a mediator

- Do previous pediatric inpatient interventions predict better outcomes for psychiatric inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa?

- Factors associated with eating disorders among Indonesian adolescents at boarding schools

- Is adolescent health a priority program? A qualitative study on the stunting prevention program in Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Understanding premenstrual syndrome: experiences and influences among monastir university students

- A cross-sectional study on risk factors of premenstrual syndrome among college-going students in Pune

- Application of psycho-educational intervention to reduce menstrual-related distress among adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial

- Bridging the gap: a study on substance use among the adolescents in a rural area of Jaipur

- Examining the relationship between internet addiction and the willingness to continue living, mediated by life satisfaction and negative suicidal ideation, with depression as a mediator

- Do previous pediatric inpatient interventions predict better outcomes for psychiatric inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa?

- Factors associated with eating disorders among Indonesian adolescents at boarding schools

- Is adolescent health a priority program? A qualitative study on the stunting prevention program in Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta, Indonesia