Abstract

Objectives

Adolescents are increasingly consuming energy drinks (EDs), prompting worries about their potential mental health impacts. The association between ED use and psychological effects among Palestinian teenagers, particularly the impact of smoking habits such as waterpipes, electronic cigarettes, and cigarettes, is little studied. This study explores the correlation between ED consumption and mental health outcomes such as depression, insomnia, and stress among adolescents in Palestine.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from February to June 2024, involving adolescents aged 12–18 recruited from schools in the West Bank. Data collection utilized a structured questionnaire assessing ED consumption, smoking habits, depression (PHQ-9), insomnia (ISI), and stress (Adolescent Stress Scale). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 29.

Results

The research involved 1,668 adolescents, with a mean age of 15.67 years (±1.57 years). ED consumption was prevalent at 74.7 % (95 % CI: 76.5–72.7). Males and smokers, especially those using traditional cigarettes and waterpipes, exhibited a higher likelihood of consuming energy drinks (aPR: 2.18; 95 %CI: 1.64–2.91), (aPR: 2.99; 95 %CI: 1.49–5.59), and (aPR: 2.54; 95 %CI: 1.23–5.19). Depression exhibited a significant relationship with ED consumption (aPR: 2.25; 95%CI: 1.51–3.37). A dose-response relationship was identified between insomnia and ED consumption, with an adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) of 2.42 (95 % CI: 1.56–3.47) for moderate severity and 2.95 (95 % CI: 1.28–6.75) for severe insomnia.

Conclusions

ED consumption is associated with poorer mental health outcomes, particularly among smokers. Interventions targeting both ED use and smoking behaviors are crucial to improving mental health in Palestinian adolescents. The study was conducted during the Gaza war, a period marked by heightened stress levels among participants due to increased security checks and economic hardships. These challenges may have influenced participants’ stress levels and impacted their purchasing behaviors for EDs and tobacco shisha products. Further research is needed to explore the long-term effects of these behaviors.

Implications and contributions statement

This study provides valuable insights into the association between energy drink consumption and mental health issues, including depression, insomnia, and stress, among adolescents in Palestine. Our findings highlight the widespread consumption of energy drinks in this population, particularly among smokers, and the significant mental health risks associated with this behavior. The study emphasizes the urgent need for public health interventions targeting energy drink use and smoking behaviors to improve adolescent mental health outcomes in Palestine and similar low-resource, conflict-affected settings.

This research contributes to the existing body of knowledge by.

Identifying the prevalence of energy drink consumption among Palestinian adolescents and its strong association with mental health conditions such as depression and insomnia.

Demonstrating the associations between smoking behaviors, including traditional cigarettes, electronic cigarettes, and waterpipes, and the relationship between energy drink use and mental health outcomes.

Highlighting the need for culturally sensitive public health campaigns and policy regulations to reduce energy drink consumption and its associated harms in this vulnerable population.

Introduction

Energy drinks (EDs) are consumed extensively across the globe, with global sales exceeding $200 billion in 2024 [1]. In the United States, they are the second most popular nutritional supplement consumed by teens and young adults. These beverages are promoted to adolescents to enhance focus, energy, athletic performance, and weight reduction [2]. The most popular components are caffeine, taurine, guarana, glucuronolactone, ginseng, vitamin B complex, and many others [2], 3].

Several studies were conducted to investigate the prevalence of ED usage among young individuals. For instance, 51.2 % of adolescents in Australia and 1.7 % in Germany have reported utilizing ED at some stage in their lives [4], 5]. The prevalence of ED use in the USA has increased significantly from 2003 to 2016, rising from 0.2 to 1.4 % among adolescents and from 0.5 to 5.5 % among young adults [6]. In the Arab World, 30 % of university students in Lebanon reported using EDs, while 84.6 % of adolescents in Saudi Arabia indicated similar usage [7].

ED consumption leads to numerous documented physical health issues and effects on the nervous and cardiovascular systems [8]. Adolescents are not usually aware of the harmful effects of ED. A study of an Australian sample showed that less than two-fifths of all ED consumers were aware of the guidelines for the maximum recommended daily intake [9]. The most common usage motivators were enjoying the taste and the need to focus while studying. The minor reasons were imitating friends and relieving headaches [3]. In Palestine, many additional factors could be added to the list: the problematic living circumstances brought on by the occupation, poverty, instability, violations of justice and equality, territorial fragmentation, cultural pressures, future insecurity, a lack of positive social outlets, a lack of recreational facilities, and the lack of access to health and mental health care services [10], [11], [12].

ED use has been connected to a number of mental health disorders and illnesses. A systematic review and meta-analysis established a connection between insomnia, stress, and depressive mood in adolescents and the consumption of ED [8]. Among Saudi Arabian adolescents, insomnia was the most prevalent symptom connected to ED usage [13]. Where in Australia, ED consumption was linked to depression, stress, and anxiety [14]. In Russia, frequent ED consumption in adolescents was associated with cigarette smoking and insomnia [15].

The consumption of ED and its effects on adolescents has not previously been examined among school children in Palestine. The purpose of this study is to increase knowledge about the prevalence of ED use among adolescents and the possible negative effects it may have on mental health. In particular, the connections between smoking, depression, insomnia, and stress in adolescents consuming EDs.

Methodology

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from February to June 2024 and targeted Palestinian adolescents attending schools. Participants were recruited through online advertisements, e-mail campaigns, and social media. Those responding received a letter explaining the study objectives and ethical issues. The questionnaire was distributed through closed social media groups using a Google Form link. Participants provided informed consent prior to completing the online questionnaire.

Sampling and sample size

The study’s objectives were achieved with a minimum required sample size of 385 students. This calculation was based on an estimated prevalence of 50 % for high ED consumption among university students, a 95 % confidence level, a 5 % margin of error, and a design effect of 1. The sample size was determined using the formula for descriptive studies: [n=[DEFF * Np(1 – p)]/[(d2/Z21/2*(N – 1))+p * (1 – p)]]. To ensure adequate representation across the three geographic regions of the West Bank – North, Central, and South – the sample size was tripled, resulting in a final target of 1,155 students.

Given the political situation in the West Bank, conducting a random sampling process was challenging due to restrictions on accessing all schools. As a result, a non-random sampling method was used to select participants. Confidentiality of the collected information was ensured, and all students were approached and invited to participate voluntarily. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hebron College of Medicine [Ref #: Int.R. Jan. 2023/31].

Measures

The study’s measuring tool was a four-part, self-administered questionnaire developed by the research team. The first part assessed the students’ sociodemographic factors.

Include gender, age, smoking status, and ED consumption. In the second section, depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is designed to evaluate self-reported symptoms of depression and consists of nine items. It has been extensively used to assess the prevalence of depression in various populations. Participants rate how often they have experienced symptoms over the past two weeks, such as fatigue and poor appetite, on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day). The cutoff points are categorized as follows: 0–4 (normal), 5–9 (minimal symptoms), 10–14 (mild), 15–19 (moderate), and 20+ (severe), indicating varying levels of depression severity. Total scores range from 0 to 27 [16]. The scale has been evaluated among different populations and has good psychometric properties to measure depression (α=0.85) [17].

The third section assessed insomnia using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), a 7-item self-report questionnaire assessing insomnia’s nature, severity, and impact. The usual recall period is the “last month,” and the dimensions evaluated are sleep onset, sleep maintenance, early morning awakening problems, sleep dissatisfaction, interference of sleep difficulties with daytime functioning, noticeability of sleep problems by others, and distress caused by the difficulties with sleep. A 5-point Likert scale is used to rate each item (e.g., 0=no problem; 4=very severe problem), yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 28. The total score is interpreted as follows: absence of insomnia (0–7), sub-threshold insomnia (8−14), moderate insomnia (15–21), and severe insomnia (22–28) [18]. The scale was evaluated among different populations and has good psychometric properties to measure insomnia in adolescents (α=0.82) [18].

Finally, stress was assessed through the Adolescence Stress Scale (ADOSS). The ADOSS asks respondents about their thoughts and feelings over the last two weeks. Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 for “not at all” to 3 for “nearly every day.” The 20-question ADOSS assesses stressors that adolescents encounter daily and major issues that are “bothersome” to them. The scale has good psychometric properties (α=0.86) [19].

The PHQ-9 and ISI tools have been validated in Arabic [20], 21]. However, no prior validation exists for the ADOSS tool in Arabic. To address this, a standardized process was followed to translate the ADOSS into Arabic. First, the tool was translated into Arabic by a bilingual expert fluent in both English and Arabic. This version was then back-translated into English by another bilingual reviewer who was unaware of the original version. Discrepancies between the original and back-translated versions were reviewed and resolved by a panel of experts to ensure conceptual and linguistic accuracy.

Additionally, the questionnaire’s overall validity was confirmed by a panel of experts in psychology, sociology, and public health, who assessed its cultural and contextual appropriateness. A pilot study was conducted with 50 adolescents to test the clarity and applicability of the questionnaire. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with the ADOSS tool achieving a value of 0.88, indicating good internal consistency.

Data analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was employed to analyse the data. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD). The prevalence of ED consumption and its 95 % Confidence Intervals (95 %CI) were determined. The ED consumption between groups was compared using the independent t-test and the chi-squared test. The binary regression model with robust variance was implemented to adjust for confounders and examine factors independently associated with ED consumption through multivariable analysis. The results were presented as an adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) with a 95 % confidence interval (CI). The model encompassed all factors that were highly pertinent in the literature and those that had significant associations in bivariate analysis. Statistical significance was established as p-values that were less than 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the social and demographic characteristics of the participants. The study involved 1,668 adolescents, comprising 1,064 girls and 604 boys. The ages of participants varied from 12 to 18 years, with a mean age of 15.67±1.571. Smoking habits were reported as follows: traditional smoking at 9.4 %, e-cigarette use at 4.4 %, and waterpipe smoking at 6.6 %. Of the participants, 1,246 [74.7 % (95 % CI: 76.5–72.7)] reported the consumption of energy drinks (ED).

Demographic characteristics, ED consumption and smoking status of the participating students (n=1,668).

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 12–15 | 680 | 40.8 |

| 16–18 | 988 | 59.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 604 | 36.2 |

| Female | 1,064 | 63.8 |

| Grade | ||

| 7–9 | 589 | 35.3 |

| 10–12 | 1,079 | 64.7 |

| Traditional smoking | ||

| Smoker | 156 | 9.4 |

| Non-smoker | 1,512 | 90.6 |

| Electronic-cigarette | ||

| Smoker | 74 | 4.4 |

| Non-smoker | 1,594 | 95.6 |

| Waterpipe | ||

| Smoker | 110 | 6.6 |

| Non-smoker | 1,558 | 93.4 |

| ED consumption | ||

| Yes | 1,246 | 74.7 |

| No | 422 | 25.3 |

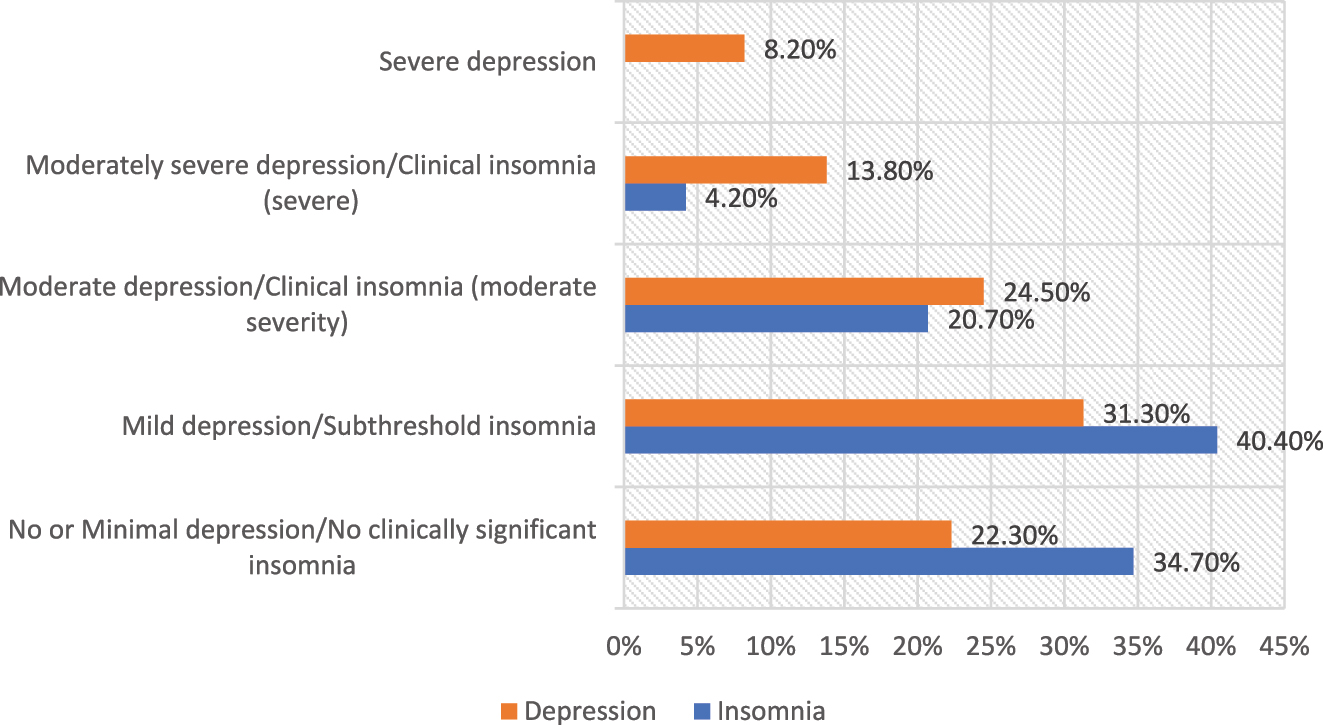

Figure 1 presents the prevalence rates of depression among participants, categorized as follows: no or minimal depression at 22.3 %, mild depression at 31.3 %, moderate depression at 24.5 %, moderately severe depression at 13.8 %, and severe depression at 8.2 %. Clinically significant insomnia, subthreshold insomnia, moderate clinical insomnia, and severe clinical insomnia were observed in 34.7, 40.4, 20.7, and 4.2 % of participants, respectively.

Prevalence and severity of depression and insomnia among palestinian adolescents (n=1,668).

Table 2 shows the frequency of stress in adolescent students. Concerning personal stress, 38 % report daily struggles with aspiring to be someone and being able to focus to achieve it. 80.7 % are not in a love relationship that causes them emotional stress. One-third of participants (34.4 %) tend to overeat or undereat for several days over the last two weeks, while 31.1 % of participants can achieve more than half of what they want in a day. In relation to academic stress, 28.2 % of the sampled population reported minimal exam anxiety.A significant proportion of individuals, 73.5 % report no distress related to their parents’ separation or disagreements, suggesting minimal parental conflict. In the context of social stress, a significant majority of respondents (71.7, 67.5, and 69.7 %) do not perceive themselves as bullied by friends, feeling inferior to their peers, or have difficulties with their peers, respectively.

Frequencies and percentages of participants’ responses to stress, social stress, family stress, academic stress, and personal stress over the last two weeks from the Adolescence Stress Scale (ADOSS).

| Scales and items | Not at all n (%) |

Several days n (%) |

More than half the days n (%) |

Nearly every day n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal stress | ||||

| I am able to achieve what I need | 262 (15.7) | 506 (30.3) | 518 (31.1) | 382 (22.9) |

| I tend to overeat or eat very less | 528 (31.7) | 574 (34.4) | 338 (20.3) | 228 (13.7) |

| I worry about my physical/body image | 1,026 (61.5) | 338 (20.3) | 158 (9.5) | 146 (8.8) |

| I aspire to be someone and focus to achieve it | 420 (25.2) | 300 (18) | 314 (18.8) | 634 (38) |

| I am often bothered by negative/sexual thoughts | 858 (51.4) | 382 (22.9) | 272 (16.3) | 156 (9.4) |

| I have difficulty in communication with the opposite (boys/girls) | 924 (55.4) | 426 (25.5) | 218 (13.1) | 100 (6) |

| I am involved in a love relationship which is causing emotional strain | 1,346 (80.7) | 136 (8.2) | 108 (6.5) | 78 (4.7) |

| I feel loss of self confidence | 1,056 (63.3) | 390 (23.4) | 126 (7.6) | 96 (5.8) |

| I am worried about my prolonged illness | 1,176 (70.5) | 250 (15) | 154 (9.2) | 88 (5.3) |

| Academic stress | ||||

| I have problems in meeting academic and extracurricular demands | 802 (48.1) | 554 (33.2) | 216 (12.9) | 96 (5.8) |

| I am unable to concentrate on studies | 380 (22.8) | 646 (38.7) | 330 (19.8) | 312 (18.7) |

| I am least scared about my performance in exams | 372 (22.3) | 498 (29.9) | 328 (19.7) | 470 (28.2) |

| I have problems speaking to persons in authority | 1,028 (61.6) | 364 (21.8) | 166 (10) | 110 (6.6) |

| Family stress | ||||

| I experience pressure from my parents over rules and expectation | 898 (53.8) | 476 (28.5) | 176 (10.6) | 118 (7.1) |

| I experience lots of conflicts with my parents | 970 (58.2) | 410 (24.6) | 166 (10) | 122 (7.3) |

| I am disturbed by separation/quarrelling of my parents | 1,226 (73.5) | 210 (12.6) | 142 (8.5) | 90 (5.4) |

| I have pressure due to financial problem at home | 974 (58.4) | 368 (22.1) | 192 (11.5) | 134 (8) |

| Social stress | ||||

| I feel my friends are always teasing/bullying me | 1,196 (71.7) | 284 (17) | 116 (7) | 72 (4.3) |

| I feel inadequate compared to my own age group boys and girls | 1,126 (67.5) | 286 (17.1) | 164 (9.8) | 92 (5.5) |

| I have difficulties with peer group/influenced by the peers | 1,162 (69.7) | 292 (17.5) | 142 (8.5) | 72 (4.3) |

Male participants were 84.1 % more likely to use ED than females (69.4 %, p-value=0.001). ED consumption for participants aged 16–18 was higher (79.1 %), compared to 68.2 % for those aged 12–15 (p=0.001). Traditional cigarette smokers consumed ED at 93.6 %, substantially higher than non-smokers (p-value=0.001). Similarly, 91.9 % of e-cigarette smokers also used EDs (p-value=0.001). Examining the link between ED use and PHQ depression symptoms, participants who used EDs were more likely to have moderate to severe depression. In contrast, non-consumers were more likely to have minimal or no depression (p-value<0.001). Regarding ISI-measured insomnia and ED consumption. ED consumers were more prone to suffer moderate-to-severe clinical insomnia. Clinical insomnia of moderate severity affects 24.4 % of ED consumers and 10 % of non-consumers. Consumers had a statistically significant difference in all stressors, with a p-value of 0.001 as seen in Table 3.

The association between ED consumption and Socio-demographic factors and smoking status (n=1,668).

| EDs consumption | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No ED (n=422) | ED (n=1,246) | p-Value | |

| Age | |||

| 12–15 | 216 (31.8 %) | 464 (68.2 %) | 0.001 |

| 16–18 | 206 (20.9 %) | 782 (79.1 %) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 96 (15.9 %) | 508 (84.1 %) | 0.001 |

| Female | 326 (30.6 %) | 738 (69.4 %) | |

| Grade | |||

| 7–9 | 198 (33.60 %) | 391 (66.4 %) | 0.001 |

| 10–12 | 224 (20.80 %) | 855 (79.2 %) | |

| Traditional smoking | |||

| Smoker | 10 (6.4 %) | 146 (93.6 %) | 0.001 |

| Non-smoker | 412 (27.2 %) | 1,100 (72.8 %) | |

| Electronic-cigarette | |||

| Smoker | 6 (8.1 %) | 68 (91.9 %) | 0.001 |

| Non-smoker | 416 (26.1 %) | 1,178 (73.9 %) | |

| Waterpipe | |||

| Smoker | 10 (9.1 %) | 100 (90.9 %) | 0.001 |

| Non-smoker | 412 (26.4 %) | 1,146 (73.6 %) | |

| Depression | |||

| No or Minimal depression | 144 (34.10 %) | 228 (18.30 %) | 0.001 |

| Mild depression | 132 (31.30 %) | 390 (31.30 %) | |

| Moderate depression | 80 (19.00 %) | 328 (26.30 %) | |

| Moderately severe depression | 40 (9.50 %) | 190 (15.20 %) | |

| Severe depression | 26 (6.20 %) | 110 (8.80 %) | |

| Insomnia | 0.001 | ||

| No clinically significant insomnia | 188 (44.50 %) | 390 (31.30 %) | |

| Subthreshold insomnia | 184 (43.60 %) | 490 (39.30 %) | |

| Clinical insomnia (moderate severity) | 42 (10.00 %) | 304 (24.40 %) | |

| Clinical insomnia (severe) | 8 (1.90 %) | 62 (5.00 %) | |

| Stress factor | |||

| Personal stress | 0.82 (0.50) | 0.92 (0.49) | 0.001 |

| Academic stress | 0.94 (0.71) | 1.10 (0.69) | 0.001 |

| Family stress | 0.57 (0.66) | 0.65 (0.69) | 0.001 |

| Social stress | 0.52 (0.66) | 0.47 (0.65) | 0.001 |

| Total stress | 0.75 (0.50) | 0.84 (0.48) | 0.715 |

On multivariable analysis, males were significantly more likely to consume EDs than females. Thus gender strongly predicted ED intake (aPR: 2.18; 95 %CI: 1.64–2.91). The results showed that smoking was a decisive factor. Smokers who used conventional cigarettes and smokers who used waterpipes (aPR: 2.99; 95 %CI: 1.49–5.59) and (aPR: 2.54; 95 %CI: 1.23–5.19), respectively, were significantly more likely to consume EDs than nonsmokers. These results suggest that there is a greater likelihood of engaging in harmful behaviors such as consuming EDs when engaging in another harmful behavior such as some type of smoking. In addition, depression showed a significant association with ED consumption (aPR: 2.25; 95 %CI: 1.51–3.37). A dose-response effect was found between insomnia and ED consumption, showing that clinical insomnia was significantly related to ED consumption (aPR: 2.42; 95 %CI: 1.56–3.47) for moderate severity and (aPR: 2.95; 95 %CI: 1.28–6.75) for severe insomnia. Finally, all levels of stress were significantly associated with ED consumption, as seen in Table 4.

Multivariable Poisson regression (with robust variance) analysis of variables related to ED consumption.

| Prevalence ratio | 95 %CI | aP value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Ref: 12–15 years) | 0.711 | 0.41–1.21 | 0.21 |

| Gender (Ref: Female) | 2.18 | 1.64–2.91 | <0.0001 |

| Grade (Ref: 7–9) | 1.69 | 0.99–2.89 | 0.052 |

| Cigarette smoker (Ref: No) | 2.99 | 1.49–5.97 | 0.002 |

| Vape smoker (Ref: No) | 2.06 | 0.82–5.21 | 0.124 |

| Waterpipe smoking (Ref: No) | 2.54 | 1.23–5.19 | 0.011 |

| Depression (ref: No or Minimal depression) | |||

| Mild depression | 1.88 | 1.35–2.62 | <0.0001 |

| Moderate depression | 2.25 | 1.51–3.37 | <0.0001 |

| Moderately severe depression | 2.09 | 1.24–3.51 | 0.005 |

| Severe depression | 1.88 | 0.99–3.55 | 0.053 |

| Insomnia (Ref: No clinically significant insomnia) | |||

| Subthreshold insomnia | 0.87 | 0.64–1.16 | 0.346 |

| Clinical insomnia (moderate severity) | 2.42 | 1.56–3.74 | <0.0001 |

| Clinical insomnia (severe) | 2.95 | 1.28–6.75 | 0.011 |

| Stress | 0.03 | 0.01–0.15 | <0.0001 |

| Personal stress | 5.376 | 2.26–12.81 | <0.0001 |

| Academic stress | 2.658 | 1.73–4.08 | <0.0001 |

| Family stress | 2.018 | 1.28–3.17 | 0.002 |

-

CI, confidence interval; aP value, adjusted p value.

Discussion

The present study investigated the significant correlates of ED consumption. Significant associations were demonstrated with gender, smoking, stress, depression, and sleep disturbance. These provide new insights into sociodemographic/personal factors influencing ED use, particularly in a Palestinian Arab adolescent context.

Males were significantly more likely to consume EDs than females. This aligns with research finding that males, especially those aged 16 to 18, exhibit a high prevalence of ED consumption influenced by peer pressure, marketing strategies, and various social environmental factors [22], [23], [24], [25]. These gender differences show that focused interventions are needed to reduce the consumption of ED and adolescent males, who are more vulnerable to its harmful effects, should be targeted.

Smokers who used conventional cigarettes and those who used waterpipes were significantly more likely to consume EDs than nonsmokers. This is consistent with other research [26], [27], [28]. In addition, studies confirm that environmental risk factors and engaging in one risky behavior increase the likelihood of adolescents engaging in other risky behaviors [26], 28], 29]. Given that smoking and ED consumption are associated with adverse health effects [30], these risky behaviors poses a severe threat to public health. Therefore, reducing smoking habits may be necessary to reduce ED use.

Studies have shown a positive association between EDs and depression. Adolescents who drank EDs were more likely to suffer from mental health symptoms [31]. Mahamid showed a significant link between ED consumption and depression in Palestinian adults [32]. The fact that EDs containing caffeine may stimulate the activity of methylxanthine, which can be linked to psychological conditions such as anxiety or depression could explain the findings. However, the effects of this stimulation may vary depending on how sensitive a person is to methylxanthine [33], 34]. Depression simultaneously influences and leads to an increase in ED consumption, [31] which logically means that the interrelation between ED and depression goes both ways.

As for insomnia, the positive relationship between ED and insomnia, the link between the consumption of EDs and insomnia, and people who drink EDs were more likely to suffer from symptoms of mental health problems such as insomnia have all been shown [32]. In addition, caffeine consumption affected the people who consume it and made them more likely to suffer from insomnia and other health problems [32]. Our study showed the ISI score of severe insomnia was significantly related to ED consumption. The explanation for this could be due to the presence of taurine in ED acting as mood disturbers and interfering with sleep cycles. Also, EDs have an extremely high amount of caffeine which lead to sleep deprivation and fatigue [35].

Living in conflict-affected areas has been consistently associated with heightened psychological stress due to exposure to violence, insecurity, and economic instability. Studies have shown that individuals in such environments often experience elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) because of the prolonged adversity [36]. These stressors can significantly influence health behaviors, including dietary and substance use patterns. Stress-induced coping mechanisms may lead to increased consumption of ED as they are perceived to provide temporary relief from fatigue and stress. Furthermore, economic hardships caused by conflict can simultaneously constrain access to such products, creating variability in consumption patterns. In the context of Palestine, ongoing occupation and the additional stress of events such as the Gaza war likely exacerbated stress levels, contributing to shifts in ED consumption as both a coping mechanism and a reflection of economic constraints [37].

Conclusions

The significant correlation between ED consumption and sociodemographic and behavioral factors have important health implications for adolescents. Males, smokers, and those aged 16–18 years were more likely to consume EDs; thus, any form of targeted interventions should focus on these groups. A significant correlation between ED consumption and increased prevalence of depression and insomnia was found. ED consumption among adolescents was associated with a higher risk of moderate and moderately severe depressive symptoms and clinical insomnia, both moderate and severe. In addition, personal stress, academic stress, and family stress in ED consumers were significantly higher than in non-consumers and may imply that ED consumption could be a behavior that was used to cope with various forms of stress.

These findings emphasize the need for health interventions for ED consumption and other related issues, including smoking and problems with mental health and disturbed sleep, among adolescents. The results implicated a bidirectional association between ED consumption and both depression and insomnia. Consequently, addressing these issues could contribute significantly to mitigating the adverse effects of EDs on adolescent health.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the ongoing political events in the West Bank resulted in significant challenges in data collection. These difficulties necessitated using a convenient sampling method instead of the initially intended cluster sampling design. This may limit the generalizability of the findings. Also, the potential impact of economic challenges, during the Gaza war, may have influenced consumption habits due to affordability constraints which could affect the results, suggesting theat other times, consumption could be higher. Administering the questionnaire at a different time, under less stressful circumstances, might yield different results. Additionally, the war and the frequent sounds of attacks and bombings at night may have affected participants’ sleep patterns, which may confound findings related to stress and insomnia. Another factor to consider is nighttime cell phone use, which is a well-documented cause of sleep problems in other contexts, and may also be relevant in Palestine [38]. Finally, the disruption of in-person schooling and the shift to online learning during this period may have contributed to increased stress and altered daily routines, further influencing the behaviors investigated in this study.

Although efforts were made to simplify the language of the questionnaire for ease of comprehension, some of the younger adolescent participants found it difficult to understand specific questions. This may have led to misinterpretation or incomplete responses, affecting the overall quality of the data collected from this subgroup.

Despite the emphasis on data confidentiality and assurances provided to the students, some participants appeared hesitant to respond truthfully to specific sensitive questions, particularly those related to smoking behaviors. A social desirability bias could have led to the underreporting of smoking prevalence or other sensitive behaviors, which may affect the accuracy of the results related to those variables. In addition, the cross-sectional study limits the ability to draw inferences on cause and effect.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our deepest gratitude to the adolescents and their families who participated in this study and were willing to contribute to this research. We are also grateful to the school administrators and teachers across the West Bank who supported us in facilitating data collection. We are especially thankful to Hebron University for providing the necessary resources and institutional support to conduct this research. We also thank our Department of Family and Community Medicine colleagues for their valuable input throughout the study design and analysis stages.

-

Research ethics: The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of medicine in Hebron University approved the study (Ref: HU.CM.MRC Jan. 4\2024), and participants provided informed consent. The data were treated with strict confidentiality, with personally identifiable information concealed, and each participant was represented numerically. We confirm that all methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines, regulations, and the Declaration of Helsinki.

-

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in this study.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Research funding: There is no funding source for this study.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Statisa. Revenue of the energy & sports drinks industry worldwide 2018-2029. Consumer goods & FMCG, non-alcoholic beverages; 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/691384/sales-value-energy-drinks-worldwide/#statisticContainer [Accessed 10 January 2025].Suche in Google Scholar

2. Ali, F, Rehman, H, Babayan, Z, Stapleton, D, Joshi, DD. Energy drinks and their adverse health effects: a systematic review of the current evidence. Postgrad Med J 2015;127:308–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2015.1001712.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Al Sabbah, H, Younis, M. Consumption patterns and side effects of energy drinks among university students in Palestine: crosssectional study. MOJ Public Heal 2015;2. https://doi.org/10.15406/MOJPH.2015.02.00015.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Trapp, G, Hurworth, M, Christian, H, Bromberg, M, Howard, J, McStay, C, et al.. Prevalence and pattern of energy drink intake among Australian adolescents. J Hum Nutr Diet 2021;34:300–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/JHN.12789.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Galimov, A, Hanewinkel, R, Hansen, J, Unger, JB, Sussman, S, Morgenstern, M. Energy drink consumption among German adolescents: prevalence, correlates, and predictors of initiation. Appetite 2019;139:172–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APPET.2019.04.016.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Vercammen, KA, Koma, JW, Bleich, SN. Trends in energy drink consumption among U.S. Adolescents and adults, 2003–2016. Am J Prev Med 2019;56:827–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.12.007.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Subaiea, GM, Altebainawi, AF, Alshammari, TM. Energy drinks and population health: consumption pattern and adverse effects among Saudi population. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-019-7731-Z/FIGURES/4.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Nadeem, IM, Shanmugaraj, A, Sakha, S, Horner, NS, Ayeni, OR, Khan, M. Energy drinks and their adverse health effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2020;13(3):265-77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738120949181 Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

9. Peacock, A, Droste, N, Pennay, A, Miller, P, Lubman, DI, Bruno, R. Awareness of energy drink intake guidelines and associated consumption practices: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2016;16. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-015-2685-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Mahamid, F, Veronese, G. Psychosocial interventions for third-generation Palestinian refugee children: current challenges and hope for the future. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2021;19:2056–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11469-020-00300-5/METRICS.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Veronese, G, Mahamid, F, Bdier, D, Pancake, R. Stress of COVID-19 and mental health outcomesin Palestine: the mediating role of well-beingand resilience. Health Psychol Rep 2021;9:398–410. https://doi.org/10.5114/HPR.2021.104490.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Barber, BK, McNeely, CA, El Sarraj, E, Daher, M, Giacaman, R, Arafat, C, et al.. Mental suffering in protracted political conflict: feeling broken or destroyed. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156216. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0156216.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Alsunni, AA, Badar, A. Energy drinks consumption pattern, perceived benefits and associated adverse effects amongst students of University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2011;23.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Kaur, S, Christian, H, Cooper, MN, Francis, J, Allen, K, Trapp, G. Consumption of energy drinks is associated with depression, anxiety, and stress in young adult males: evidence from a longitudinal cohort study. Depress Anxiety 2020;37:1089–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/DA.23090.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Kong, G, Idrisov, B, Galimov, A, Masagutov, R, Sussman, S. Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adolescents in the Russian Federation. Subst Use Misuse 2017;52:332–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1225766.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Sun, Y, Fu, Z, Bo, Q, Mao, Z, Ma, X, Wang, C. The reliability and validity of PHQ-9 in patients with major depressive disorder in psychiatric hospital. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12888-020-02885-6/TABLES/2.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Kroenke, K, Spitzer, RL, Williams, JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.1525-1497.2001.016009606.X.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Morin, CM, Belleville, G, Bélanger, L, Ivers, H. The insomnia severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011;34:601. https://doi.org/10.1093/SLEEP/34.5.601.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Jagannathan, N, Anjana, RM, Mehreen, TS, Yuvarani, K, Sathishkumar, D, Poongothai, S, et al.. Reliability and validity of the adolescence stress scale (ADOSS) for Indian adolescents. Indian J Psychol Med 2022;XX:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176221127138.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. AlHadi, AN, AlAteeq, DA, Al-Sharif, E, Bawazeer, HM, Alanazi, H, AlShomrani, AT, et al.. An Arabic translation, reliability, and validation of Patient Health Questionnaire in a Saudi sample. Ann Gen Psychiatr 2017;16:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12991-017-0155-1/TABLES/7.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Al Maqbali, M, Madkhali, N, Dickens, GL. Psychometric properties of the insomnia severity Index among Arabic chronic diseases patients. SAGE Open Nurs 2022;8. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608221107278/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_23779608221107278-FIG2.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Alissa, NA. The impact of social media on adolescent energy drink consumption. Médica Sur 2024;103:E38041. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000038041.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Ajibo, C, Van Griethuysen, A, Visram, S, Lake, AA. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: a systematic review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. Public Health 2024;227:274–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PUHE.2023.08.024.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Visram, S, Cheetham, M, Riby, DM, Crossley, SJ, Lake, AA. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: a rapid review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010380. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2015-010380.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Al-Waalan, T, Al Khamees, R. Energy drinks consumption patterns among young Kuwaiti adults. SHS Web Conf. 2021;123:01015. https://doi.org/10.1051/SHSCONF/202112301015.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Larson, N, DeWolfe, J, Story, M, Neumark-Sztainer, D. Adolescent consumption of sports and energy drinks: linkages to higher physical activity, unhealthy beverage patterns, cigarette smoking, and screen media use. J Nutr Educ Behav 2014;46:181–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNEB.2014.02.008.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Khamis, N, Ibrahim, R, Iftikhar, R, Murad, M, Fida, H, Abalkhaeil, B. Energy drinks consumption amongst medical students and interns from three colleges in jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Food Nutr Res 2014;2:174–9. https://doi.org/10.12691/JFNR-2-4-7.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Markon, AO, Ding, M, Chavarro, JE, Wolpert, BJ. Demographic and behavioural correlates of energy drink consumption. Public Health Nutr 2023;26:1424–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980022001902.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Schieber, E, Wang, A, Ou, G, Herbert, C, Nguyen, HT, Deveaux, L, et al.. The influence of socioenvironmental risk factors on risk-taking behaviors among Bahamian adolescents: a structural equation modeling analysis. Heal Psychol Behav Med 2024;12. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2023.2297577.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

30. Alsunni, AA. Energy drink consumption: beneficial and adverse health effects. Int J Health Sci 2015;9:468. https://doi.org/10.12816/0031237.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Kim, H, Park, J, Lee, S, Lee, SA, Park, EC. Association between energy drink consumption, depression and suicide ideation in Korean adolescents. 2020;66(4):335-43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020907946 Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Mahamid, F, Bdier, D, Damiri, B. Energy drinks, depression, insomnia and stress among Palestinians: the mediating role of cigarettes smoking, electronic cigarettes and waterpipe. J Ethn Subst Abuse 2022;0:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2022.2136812.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Park, S, Lee, Y, Lee, JH. Association between energy drink intake, sleep, stress, and suicidality in Korean adolescents: energy drink use in isolation or in combination with junk food consumption. Nutr J 2016;15:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12937-016-0204-7/TABLES/3.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Rodak, K, Kokot, I, Kratz, EM. Caffeine as a factor influencing the functioning of the human body—friend or foe? Nutrients 2021;13. https://doi.org/10.3390/NU13093088.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Mihaiescu, T, Turti, S, Souca, M, Muresan, R, Achim, L, Prifti, E, et al.. Caffeine and taurine from energy drinks—a review. Inside Cosmet 2024;11:12. https://doi.org/10.3390/COSMETICS11010012.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Miller, KE, Rasmussen, A. The mental health of civilians displaced by armed conflict: an ecological model of refugee distress. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2017;26:129–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000172.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Hamadeh, A, El-Shamy, F, Billings, J, Alyafei, A. The experiences of people from Arab countries in coping with trauma resulting from war and conflict in the Middle East: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Trauma Violence Abuse 2024;25:1278–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231176061/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_15248380231176061-FIG1.JPEG.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Adams, SK, Daly, JF, Williford, DN. Article commentary: adolescent sleep and cellular phone use: recent trends and implications for research 2013;6. https://doi.org/10.4137/HSI.S11083 Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Evaluating the relationship between marijuana use, aggressive behaviors, and victimization: an epidemiological study in colombian adolescents

- Enhancing adolescent health awareness: impact of online training on medical and community health officers in Andhra Pradesh, India

- Development of the “KARUNI” (young adolescents community) model to prevent stunting: a phenomenological study on adolescents in Gunungkidul regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Energy drinks, depression, insomnia, and stress in palestinian adolescents: a cross-sectional study

- Characterization of the most common diagnoses in a population of adolescents and young adults attended by a Healthcare Service Provider (HSP) in Bogotá, Colombia

- Association of chronotype pattern on the quality of sleep and anxiety among medical undergraduates – a cross-sectional study

- Addressing emotional aggression in Thai adolescents: evaluating the P-positive program using EQ metric

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Evaluating the relationship between marijuana use, aggressive behaviors, and victimization: an epidemiological study in colombian adolescents

- Enhancing adolescent health awareness: impact of online training on medical and community health officers in Andhra Pradesh, India

- Development of the “KARUNI” (young adolescents community) model to prevent stunting: a phenomenological study on adolescents in Gunungkidul regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Energy drinks, depression, insomnia, and stress in palestinian adolescents: a cross-sectional study

- Characterization of the most common diagnoses in a population of adolescents and young adults attended by a Healthcare Service Provider (HSP) in Bogotá, Colombia

- Association of chronotype pattern on the quality of sleep and anxiety among medical undergraduates – a cross-sectional study

- Addressing emotional aggression in Thai adolescents: evaluating the P-positive program using EQ metric