Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the relationship between marijuana use and aggression and victimization among Colombian adolescents. We aimed to clarify marijuana’s distinct role by comparing different categories of drug use and by considering the order of drug initiation.

Methods

We conducted a secondary analysis of nationally representative cross-sectional data collected from Colombian adolescents in 2016. The original sample included 80,018 students in Grades 7 to 11. Participants were categorized into marijuana-use groups – EXCLUSIVE (marijuana only), INITIAL (marijuana use before other drugs), and SUBSEQUENT (marijuana use following other drugs) – and non-marijuana-use groups – NON-DRUG (no use), ONE-DRUG (one other drug only), and MULTIPLE-DRUG (two or more other drugs).Aggressive behaviors (individual aggression, group aggression, harassment) and victimization were assessed based on self-reported involvement in the past 12 months. Logistic regression models examined associations between marijuana use patterns and these outcomes, controlling for sex, age, parental education, and grade repetition. For the SUBSEQUENT group, the total number of other drugs used was also controlled.

Results

Adolescents with no drug use had the lowest rates of all aggressive behaviors and victimization. As drug use increased, so did the prevalence of these outcomes, with MULTIPLE-DRUG users exhibiting the highest levels. Compared to NON-DRUG adolescents, each marijuana-use group (EXCLUSIVE, INITIAL, SUBSEQUENT) showed increased odds of some forms of aggression and victimization. For example, EXCLUSIVE users had higher odds of aggression compared to NON-DRUG users. However, the magnitude of these associations differed when comparing marijuana-use groups against each other and against ONE-DRUG and MULTIPLE-DRUG groups. INITIAL and SUBSEQUENT users often demonstrated greater odds of aggression than EXCLUSIVE users, suggesting that polydrug involvement and the sequence of drug initiation matter.

Conclusions

These findings underscore the importance of moving beyond binary classifications of marijuana use when examining aggression and victimization among adolescents. Marijuana use is associated with an increased risk of aggression and victimization, but other substance use patterns and the temporal order of drug initiation influence this relationship. Policymakers, educators, and clinicians should consider these when designing preventive interventions. Future research should employ longitudinal designs and incorporate additional contextual variables to further clarify the mechanisms linking marijuana use to aggression and victimization.

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period of human development characterized by biological, psychological, and social transitions. During this stage, maturation of the brain’s reward and emotional regulation systems makes adolescents especially sensitive to external influences, including the availability and use of psychoactive substances [1], 2]. Among these substances, marijuana stands out as one of the most frequently used illicit drugs worldwide [3]. Its prevalence, combined with evolving public discourse and changing policies in many regions, has heightened interest in understanding its potential impact on youth well-being.

A central concern regarding marijuana consumption is its interplay with aggression and victimization [4]. Conceptually, aggression encompasses behaviors intended to harm others, ranging from verbal harassment to physical violence, whereas victimization refers to being the target of such harmful behaviors [5]. Both outcomes are linked to disrupted developmental trajectories, impaired mental health, and compromised academic and social functioning [6]. However, the direction and magnitude of marijuana’s role in these aggressive and victimizing behaviors remain a subject of debate [7]. On one hand, cultural narratives and some empirical evidence suggest that marijuana’s calming, sedative, and euphoric effects might reduce hostility and aggressive impulses [8], 9]. On the other hand, studies suggest that marijuana may impair emotional regulation, increase irritability, and worsen impulse control, thereby increasing the likelihood of aggressive behavior or vulnerability to victimization, particularly in risky or marginal social contexts [10], [11], [12].

The mixed empirical findings underscore the complexity of interpreting marijuana’s role in adolescent aggression and victimization. Several theoretical frameworks can be used to explain its role. From an emotional regulation perspective, marijuana use might interact with underlying mood dysregulation, making some adolescents more prone to lose control or become entangled in conflict [13]. Social Network theories suggest that adolescents who use marijuana may be embedded in peer networks that normalize risk-taking and aggression, potentially increasing both perpetration and victimization [14]. Stress-coping models posit that adolescents might turn to substances such as marijuana in response to environmental stressors, inadvertently placing themselves in high-risk situations for aggression or victimization [15].

A key methodological challenge in this literature is the tendency to treat adolescent marijuana users as a homogeneous group. However, adolescent substance use behaviors are diverse. Many youths who consume marijuana also use other drugs, including alcohol, tobacco, or inhalants [16], each carrying its own well-documented risks [17], 18]. This polydrug context can obscure marijuana’s unique effects, as aggression or victimization may be influenced by the additive or interactive effects of multiple substances. Moreover, the sequence of drug initiation may matter [19], 20]. Initiating marijuana use before other substances could set a different developmental trajectory compared to starting with other drugs first and then introducing marijuana. By failing to differentiate exclusive marijuana users from those who use multiple substances, and by not accounting for the timing of different drug initiations, previous studies risk cofounding marijuana’s potential impact with that of other substances.

The present study seeks to address this complexity by employing a multigroup analytical approach that classifies adolescents into distinct categories based on their marijuana and other drug use histories. We identify exclusive marijuana users and compare them to adolescents who report no drug use, those who use only one other drug, and those who use multiple drugs. Within the marijuana-using groups, we further distinguish between adolescents who started with marijuana before using any other substance and those who began with other drugs prior to marijuana use. By parsing these different user profiles, we aim to isolate marijuana’s specific contributions to aggression and victimization, separate from the confounding effects of other drugs.

This approach allows us to test longstanding theoretical propositions such as marijuana’s role in aggression and victimization. If marijuana use alone is linked to certain forms of aggression or victimization, this finding would support models emphasizing the drug’s pharmacological effects on emotional and behavioral regulation. Alternatively, if polydrug use groups demonstrate the strongest associations with aggression and victimization, it would highlight the importance of broader social-ecological factors and the synergistic effects of multiple substances. Evidence of differential effects based on the sequence of drug initiation could suggest a developmental ordering that shapes later behavioral outcomes, offering insights into prevention and early intervention strategies.

In sum, this study extends the debate on marijuana’s role in adolescent aggression and victimization by using a multigroup design. By moving beyond simplistic comparisons of marijuana users vs. non-users, we aim to clarify how exclusive vs. polydrug patterns, and the temporal sequencing of marijuana use, inform our understanding of the relationship between marijuana use and aggression and victimization.

Methods

Study sample

This study is a secondary data analysis of the National Study of Psychoactive Substance Consumption database from Colombia (2016). The sampling strategy involved clustering and stratification of the data. Student, categorized by their grade levels, served as the final unit of selection. The sampling process was multistage: primary sampling units were constituted by municipalities, and secondary sampling units by schools, with an additional consideration of their public or private status. Colombia has 1,104 municipalities grouped into 32 departments. The population of study corresponded to 3,243,377 students in Grades 7 to 11. The final sample consisted of 80,018 students from 1,097 schools across 163 municipalities in Colombia [21].

This study adhered to the procedures established by the Uniform Data System (Sistema de Datos Uniformes, SIDUC) of the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD). The protocol for this population includes measures to reduce respondent bias and protect confidentiality during data collection.

The survey was administered to the entire school groups during regular class hours, ensuring consistency across the sample. Individual applications were explicitly avoided to maintain anonymity and reduce social pressure. The questionnaire was self-administered, and survey administrators were trained to never review completed questionnaires in the presence of students. Additional measures to safeguard confidentiality included requesting teachers to leave the room while the survey was conducted and ensuring that the forms did not contain any identifying information about participants. These protocols help to minimize potential biases and encourage honest responses.

Measures

Outcome variables: aggression and victimization

Measures of aggression and victimization were assessed based on students’ responses to nine questions concerning behaviors they had either perpetrated or experienced in the last 12 months (see Table 1). Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of these behaviors, with response options ranging from 1=never, 2=one to two times, 3=three to four times, to 4=five or more times. Behaviors were organized into four main outcomes: individual aggression, group aggression, harassment, and victimization based on the description of the behavior in each question.

Items for aggression and victimization outcome variables.

| Outcome | During the last 12 months, how often have any of these situations occurred at school? |

|---|---|

| Group aggression | Having physically assaulted a classmate with other classmates |

| Having participated in a group that started a fight with another group | |

| Harassment | Having teased a classmate with other classmates |

| Individual aggression | Having started a fight alone |

| Having assaulted a teacher | |

| Victimization | Having been teased alone by someone from school |

| Having been physically assaulted by someone from school | |

| Having been in a group that was attacked by another group | |

| Having been assaulted by a teacher |

After categorizing the behaviors, we computed a unique score for each outcome based on the following criteria: If a student reported experiencing or perpetrating at least one behavior within an outcome, that variable was coded as 1. Conversely, if a student did not report any behaviors within an outcome, the variable was coded as 0.

Independent variables: groups of use and no use of marijuana

Drug use was assessed by asking students about their lifetime use of various drugs (e.g., alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, inhalants, etc.). Students were asked, “Have you ever used (drug)?” to which they responded 1=Yes or 0=No. Those who reported affirmative responses to any drug use were further questioned about the age at which they first used the drug (i.e., At what age did you use the drug for the first time?).

Regarding the use of marijuana and other drugs, participants were categorized into two main groups: those who reported use of marijuana and those who did not report use of marijuana. For those who reported use of marijuana, three subgroups were established: Exclusive Marijuana Use (EXCLUSIVE), comprising students who only reported use of marijuana; Initial Marijuana Use (INITIAL), consisting of students who initiated drug use with marijuana and later experimented with other drugs; and Subsequent Marijuana Use (SUBSEQUENT), involving students who had used other drugs before trying marijuana, with marijuana being their most recently initiated drug. The categorization aimed to account for the confounding effects of non-marijuana drug use on aggressive behaviors and victimization. For example, in the INITIAL group, the use of subsequent drugs was hypothesized to mediate the relationship between marijuana use and aggression, and thus was not included as a control variable in the regression models. In contrast, for the SUBSEQUENT group, previous drug use was considered a potential confounder and was therefore included as a control variable in the models. This approach allowed us to account for the varying impacts that other drug use might have on the outcomes being studied.

We also identified three groups of students with no use of marijuana: the No-Drug Use group (NON-DRUG), which included students with no drug use history. This group provided a reference point for no effect of drugs on aggression and victimization; the One-Other-Drug Use group (ONE-DRUG), composed of students who had used one other drug distinct from marijuana (such as alcohol, tobacco, inhalants, etc.). This group accounted for the effects of single-drug use; and the Two-Or-More-Other-Drug Use group (MULTIPLE-DRUG), which included students who had tried multiple drugs other than marijuana. This group controlled for the effects of polydrug use.

Demographic variables

Participant demographic variables included participant’s sex (1=male, 0=female), student’s age at the time of data collection (in years), parent’s level of education (1=no education, 2=primary only, 3=high school graduate, 4=technical school, 5=bachelors or master’s degree, and 6=postgraduate degree), and whether the participant has repeated a grade (1=yes, 0=no). Table 2 displays sample sizes and demographic characteristics of the Marijuana Use and Non-Marijuana Use groups.

Demographic characteristics of marijuana use and non-use groups.

| Non-marijuana use | Marijuana use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-drug use | One drug | Multiple drugs | Exclusive | Initial | Subsequent | |

| n=24,6031 | n=33,8911 | n=11,9851 | n=2131 | n=4651 | n=20,641 | |

| Male | 11,716 (48 %) | 13,762 (43 %) | 5,998 (51 %) | 110 (53 %) | 245 (53 %) | 1,063 (52 %) |

| Not reported | 310 | 328 | 108 | 6 | 1 | 15 |

| Age | 14.53 (1.67) | 15.20 (1.58) | 15.55 (1.51) | 15.44 (1.45) | 15.91 (1.36) | 16.05 (1.34) |

|

|

||||||

| Mother’s education | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Primary | 4,595 (19 %) | 5,869 (18 %) | 2,296 (19 %) | 42 (20 %) | 89 (19 %) | 425 (21 %) |

| High school | 9,534 (39 %) | 12,937 (40 %) | 4,906 (41 %) | 93 (44 %) | 215 (46 %) | 881 (43 %) |

| Technical | 2,566 (10 %) | 4,537 (14 %) | 1,686 (14 %) | 22 (10 %) | 44 (9.5 %) | 277 (13 %) |

| Professional | 2,925 (12 %) | 4,129 (13 %) | 1,385 (12 %) | 17 (8.0 %) | 37 (8.0 %) | 219 (11 %) |

| Graduate | 1,219 (5.0 %) | 1,899 (5.8 %) | 733 (6.1 %) | 4 (1.9 %) | 26 (5.6 %) | 103 (5.0 %) |

| No education | 320 (1.3 %) | 282 (0.9 %) | 108 (0.9 %) | 5 (2.3 %) | 6 (1.3 %) | 18 (0.9 %) |

| Unknown | 2,046 (8.3 %) | 1,930 (5.9 %) | 555 (4.6 %) | 13 (6.1 %) | 31 (6.7 %) | 91 (4.4 %) |

| Other | 1,398 (5.7 %) | 905 (2.8 %) | 316 (2.6 %) | 17 (8.0 %) | 17 (3.7 %) | 50 (2.4 %) |

|

|

||||||

| Father’s education | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Primary | 4,573 (19 %) | 6,225 (19 %) | 2,508 (21 %) | 33 (15 %) | 96 (21 %) | 433 (21 %) |

| High school | 7,436 (30 %) | 10,521 (32 %) | 3,813 (32 %) | 71 (33 %) | 142 (31 %) | 682 (33 %) |

| Technical | 2,084 (8.5 %) | 3,448 (11 %) | 1,267 (11 %) | 19 (8.9 %) | 45 (9.7 %) | 214 (10 %) |

| Professional | 2,967 (12 %) | 4,096 (13 %) | 1,363 (11 %) | 16 (7.5 %) | 39 (8.4 %) | 225 (11 %) |

| Postgraduate | 1,051 (4.3 %) | 1,695 (5.2 %) | 656 (5.5 %) | 5 (2.3 %) | 20 (4.3 %) | 97 (4.7 %) |

| Graduate | 360 (1.5 %) | 368 (1.1 %) | 144 (1.2 %) | 3 (1.4 %) | 8 (1.7 %) | 23 (1.1 %) |

| Unknown | 2,854 (12 %) | 3,441 (11 %) | 1,246 (10 %) | 21 (9.9 %) | 57 (12 %) | 186 (9.0 %) |

| Other | 3,278 (13 %) | 2,694 (8.3 %) | 988 (8.2 %) | 45 (21 %) | 58 (12 %) | 204 (9.9 %) |

| Grade repetition | 3,310 (14 %) | 3,916 (12 %) | 1,731 (15 %) | 51 (24 %) | 91 (20 %) | 347 (17 %) |

| Not reported | 358 | 361 | 148 | 4 | 6 | 25 |

| Total drug use | 0.00 (0.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 2.22 (0.62) | 1.00 (0.00) | 3.68 (2.08) | 2.96 (0.85) |

-

1n (%); Mean (SD).

Statistical analysis

Students who reported marijuana use were categorized as 1=use, while those who did not report use were categorized as 0 = non-use. We compared the marijuana use and non-use groups across different types of group comparisons. The marijuana uses groups included EXCLUSIVE, INITIAL, SUBSEQUENT. The non-use groups included NON-DRUG, ONE-DRUG, and MULTIPLE-DRUG. For example, we compared the EXCLUSIVE group (use) against the three non-use groups: NON-DRUG, ONE-DRUG, and MULTIPLE-DRUG. Similarly, we compared the INITIAL group (use) and the SUBSEQUENT group (use) against each of the three non-use groups.

We estimated the association between marijuana use, aggression and victimization across these different comparisons using logistic regression models controlled for sex, student age, parental education level, and grade repetition. For the SUBSEQUENT group, the total number of different drugs used was included as an additional control variable. We reported the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for each outcome variable to assess the strength and direction of the associations.

Missing data

We excluded students from the analysis for two reasons. First, we excluded students who reported equal ages of initiation for both marijuana and other drugs, as they could not be categorized into the groups defined earlier (INITIAL, SUBSEQUENT). These students were not informative for our analysis, which uses the order in which students used marijuana and other drugs to control for confounding effects. Secondly, students who did not report their use of marijuana or lacked information on the control variables were also excluded. It is important to note that students with missing information on the outcome variable (e.g., did not answer one of the victimization questions) were still included in the analysis if they provided information on at least one behavior within the same category. The total number of students excluded was 6,797, representing 8.49 % of the total sample.

Results

Prevalence of aggressive behavior

Prevalence rates of aggressive behavior and victimization by comparison groups are presented in Table 3. Adolescents with no history of drug use exhibited the lowest rate of harassment among classmates (33.9 %), group aggression (13.3 %), individual aggression (10.8 %), and victimization (24.5 %). Reported aggression and victimization was higher when students also reported more used drugs. For example, students in the MULTIPLE-DRUG reported more harassment among classmates (61.9 %), group aggression (31.2 %) and individual aggression (26.3 %), and victimization (41.0 %) compared to students in the ONE-DRUG group and or NON-DRUG. Students in the EXCLUSIVE group reported lower values of harassment (40.0 %), group aggression (20.1 %), individual aggression (19.8 %), and victimization (32.0 %) compared to students in the INITIAL and SUBSEQUENT group.

Aggression and victimization reported over the past year, categorized by group.

| Outcome | Non-marijuana use | Marijuana use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-drug use | One drug | Multiple drugs | Exclusive | Initial | Subsequent | |

| Harassment | 33.9 % | 52.6 % | 61.9 % | 40.0 % | 52.4 % | 59.1 % |

| Group aggression | 13.3 % | 21.7 % | 31.2 % | 20.1 % | 27.9 % | 32.5 % |

| Individual aggression | 10.8 % | 16.3 % | 26.3 % | 19.8 % | 26.4 % | 26.9 % |

| Victimization | 24.5 % | 32.9 % | 41.0 % | 32.0 % | 34.1 % | 39.6 % |

Regression models

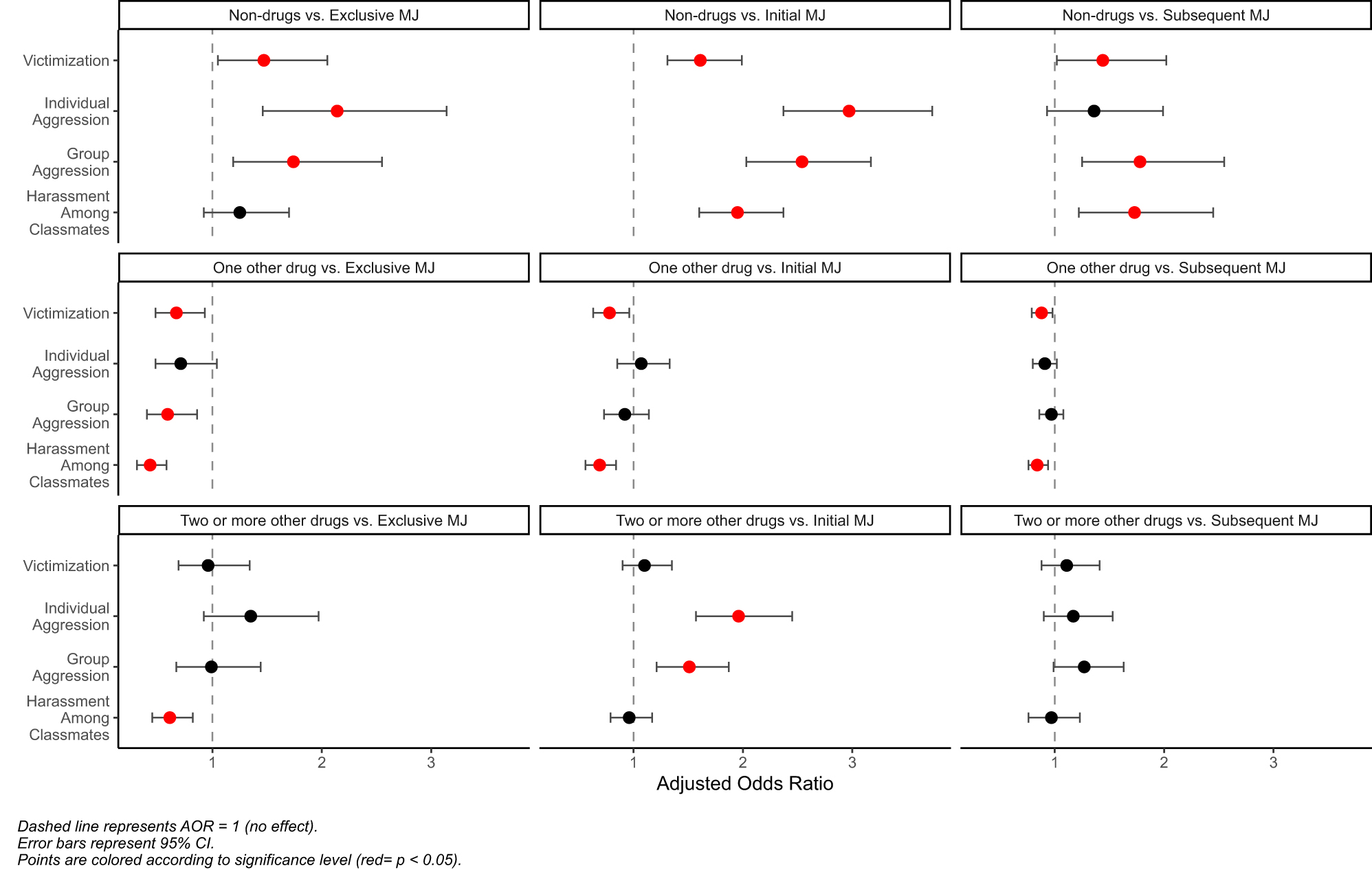

Table 4 presents the odds ratios indicating the change in the odds of reporting aggressive behavior for individuals in the marijuana use group, while controlling for other variables in the models. The parameters estimated for the controls are presented in the supplemental materials.

Odds ratios for reporting aggression/victimization across marijuana use groups compared to no-drug use, controlling for other variables.

| Group aggression | Individual aggression | Victimization | Harassment among classmates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR2 | 95 % CI2 | AOR2 | 95 % CI2 | AOR2 | 95 % CI2 | AOR2 | 95 % CI2 | |

| No-drug use | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| vs. Exclusive | 1.74** | 1.17, 2.52 | 2.14*** | 1.44, 3.10 | 1.47* | 1.04, 2.04 | 1.25 | 0.92, 1.70 |

| vs. Initial | 2.54*** | 2.03, 3.16 | 2.97*** | 2.36, 3.72 | 1.61*** | 1.31, 1.98 | 1.95*** | 1.60, 2.37 |

| vs. Subsequent | 1.78** | 1.24, 2.54 | 1.36 | 0.92, 1.98 | 1.44* | 1.02, 2.02 | 1.73** | 1.21, 2.44 |

|

|

||||||||

| One drug | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| vs. Exclusive | 0.59** | 0.39, 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.48, 1.03 | 0.67* | 0.47, 0.93 | 0.43*** | 0.31, 0.58 |

| vs. Initial | 0.92 | 0.73, 1.14 | 1.07 | 0.85, 1.33 | 0.78* | 0.63, 0.96 | 0.69*** | 0.56, 0.84 |

| vs. Subsequent | 0.97 | 0.86, 1.08 | 0.91 | 0.80, 1.02 | 0.88* | 0.79, 0.98 | 0.84** | 0.76, 0.94 |

|

|

||||||||

| Multiple | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| vs. Exclusive | 0.99 | 0.66, 1.42 | 1.35 | 0.90, 1.94 | 0.96 | 0.68, 1.33 | 0.61** | 0.45, 0.83 |

| vs. Initial | 1.50*** | 1.21, 1.87 | 1.95*** | 1.55, 2.43 | 1.1 | 0.90, 1.35 | 0.97 | 0.79, 1.17 |

| vs. Subsequent | 1.27 | 0.99, 1.62 | 1.17 | 0.89, 1.52 | 1.12 | 0.88, 1.41 | 0.97 | 0.76, 1.23 |

-

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Fixed effect. sex, age, gender, retention, father education and mother education.

Group aggression

Compared with students in the NON-DRUG, those categorized within the EXCLUSIVE had 1.74 times higher odds of reporting group aggression, as indicated by AOR=1.74 (95 % Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.17 to 2.52, p <0.05). Similarly, the odds of reporting aggression were greater for the INITIAL, with an AOR=2.54 (95 % CI: 2.03 to 3.16, p <0.001), and for the SUBSEQUENT, with an AOR of 1.78 (95 % CI: 1.24 to 2.54, p <0.05). When compared to ONE-DRUG, students in the EXCLUSIVE group presented a lower likelihood of engaging in group aggression, with an AOR=0.59 (95 % CI: 0.39 to 0.85, p <0.001), and no differences were observed when compared to the INITIAL and SUBSEQUENT groups. Lastly, compared to MULTIPLE-DRUG group, participants in the INITIAL group showed significantly increased odds of reporting group aggression, with an AOR of 1.50 (95 % CI: 1.21 to 1.87, p <0.001) and not differences were observed in the EXCLUSIVE and SUBSEQUENT group.

Individual aggression

Compared with students in the NON-DRUG, those in the EXCLUSIVE group were significantly more likely to report individual aggression, AOR=2.14 (95 % CI: 1.44 to 3.10, p <0.001)., Those in the INITIAL group also were more likely to report individual aggression, AOR=2.97 (95 % CI: 2.36 to 3.72, p <0.001). However, the SUBSEQUENT group did not show a significant increase in the odds of individual aggression (AOR=1.36, 95 % CI: 0.92 to 1.98, p >0.05). Compared to ONE-DRUG group, no significant difference in the odds of individual aggression was observed. Finally, compared to MULTIPLE-DRUG, the INITIAL group indicated significantly higher odds of reporting individual aggression (AOR=1.95, 95 % CI: 1.55 to 2.43, p <0.001).

Harassment among classmates

Compared with students in the NON-DRUG group, we found significant increase in odds for INITIAL AOR=1.95 (95 % CI: 1.60 to 2.37, p <0.001) and SUBSEQUENT groups AOR=1.73 (95 % CI: 1.21 to 2.44, p <0.01), indicating a higher report of harassment in these groups. Compared with students in the ONE-DRUG, students in the EXCLUSIVE group had lower odds of reporting harassment AOR=0.43 (95 % CI: 0.31 to 0.58, p <0.001). Similarly, we observed lower odds for INITIAL AOR=0.69 (95 % CI: 0.56 to 0.84, p <0.001) and SUBSEQUENT AOR=0.84 (95 % CI: 0.76 to 0.94, p <0.01). Finally, compared to MULTIPLE-DRUG, EXCLUSIVE group showed significantly lower odds of reporting harassment (AOR=0.61, 95 % CI: 0.45 to 0.83, p <0.01), while no significant differences were found for either INITIAL or SUBSEQUENT.

Victimization

Compared with students in the NON-DRUG group, students in the EXCLUSIVE group had an increased odds of experiencing victimization, AOR=1.47 (95 % CI: 1.04 to 2.04, p <0.05). Similar increases were observed for INITIAL (AOR=1.61, 95 % CI: 1.31 to 1.98, p <0.001) and SUBSEQUENT groups AOR=1.44 (95 % CI: 1.02 to 2.02, p <0.05). When compared to students in the ONE-DRUG, students in the EXCLUSIVE AOR=0.67 (95 % CI: 0.47 to 0.93, p <0.05), INITIAL AOR=0.78 (95 % CI: 0.63 to 0.96, p <0.05), and SUBSEQUENT AOR=0.88 (95 % CI: 0.79 to 0.98, p <0.05) exhibited lower odds of victimization. No significant differences in the odds of victimization were observed when comparing with students in the MULTIPLE-DRUG.

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the comparisons among groups and outcomes, presenting the coefficients that represent the differences between marijuana use and non-use groups. Points on the graph indicates the estimates and lines 95 % confidence intervals produced by the regression models.

Aggression and victimization among marijuana use and non-use groups.

Discussion

Overall, the data suggest that as substance use becomes more extensive, shifting from no drug use to single or multiple-drug use, rates of aggressive behavior and victimization increase. Adolescents with no history of drug use reported the lowest levels of harassment, group aggression, individual aggression, and victimization. In contrast, those engaging in multiple-drug use consistently exhibited the highest prevalence of these problematic behaviors, illustrating that polydrug involvement may relate to conditions more conducive to aggression and vulnerability.

Our results demonstrate that even when marijuana is used exclusively, adolescents face an increased likelihood of aggression and victimization relative to their non-using peers. These findings challenge narratives that position marijuana use as primarily benign and emphasize the need to consider its potential role in heightening aggression-related risks, even in the absence of other substances. At the same time, the comparison across different groups of marijuana users reveals that adolescents who used marijuana exclusively generally showed lower odds of aggression and victimization compared to those who started with marijuana and then moved on to other drugs (INITIAL) or those who began with other drugs before introducing marijuana (SUBSEQUENT). This pattern suggests that the sequence of drug initiation and the complexity of an adolescent’s substance use profile may shape the association between marijuana use and aggressive behavior. For instance, INITIAL and SUBSEQUENT groups may be more deeply embedded in risk-prone social networks or may have other underlying risk factors that magnify the likelihood of aggression and victimization.

Another notable finding is that, in several comparisons, marijuana-using groups exhibited lower odds of reporting aggressive behaviors and victimization compared to adolescents who reported using other substances. This indicates that marijuana’s influence should not be considered in isolation; instead, it must be understood within the broader context of an adolescent’s drug use repertoire. Polydrug use, especially involving multiple substances, appears to be more strongly and consistently associated with heightened aggression and victimization than marijuana use alone.

Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of moving beyond dichotomous categorizations of “marijuana user” and “non-user.” Future research should incorporate additional contextual and environmental factors, such as frequency of use, social settings, and the presence of co-occurring mental health conditions, to better elucidate the mechanisms underlying these relationships. Furthermore, interventions aimed at reducing aggression among substance-using adolescents may benefit from a more targeted approach, distinguishing between different substance use patterns and considering the temporal order of drug initiation. This perspective can help tailor prevention and treatment programs to the distinct profiles of adolescents’ substance use behaviors, ultimately contributing to more effective strategies for reducing aggression and victimization in this population.

Our findings contribute to the ongoing debate on the relationship between marijuana use and aggressive behavior among adolescents, yet we acknowledge that the social and environmental contexts in which these behaviors occur are equally important considerations. For instance, students attending private schools or residing in more privileged neighborhoods may have fewer opportunities to encounter insecure environments and, as a result, potentially less exposure to both aggressive behaviors and drug use. Conversely, less privileged neighborhoods may heighten vulnerability to environmental stressors that can foster aggression, regardless of substance use patterns.

In this study, while we controlled for certain demographic variables (e.g., parental education level, grade repetition, and age), we did not include school type (public vs. private) or other detailed measures of socioeconomic status (SES) beyond parental education. Nor did we incorporate neighborhood characteristics, as these data were not available in the dataset. Thus, we cannot fully disentangle the effects of marijuana use from those of the broader environmental contexts that adolescents inhabit. Future research should consider incorporating a wider range of social determinants. These might include neighborhood-level indicators of economic disadvantage, community violence exposure, and school quality, as well as more refined measures of family-level SES. While these issues extend beyond the scope of our current analysis, we encourage future investigations to integrate comprehensive social and environmental measures to more fully capture the interplay between drug use, socioeconomic context, victimization and aggressive behaviors.

The worldwide conversation regarding the legalization of marijuana has been gaining importance over the decade as an increasing number of countries including United States are introducing laws for both recreational use of the substance. As regulations progress and evolve in this area there are differing opinions surrounding how marijuana may influence behaviors such, as aggression. Colombia, the origin of our data, finds itself in a discussion due to its long-standing struggles with drug trafficking and violence issues that have plagued the nation with several social problems. The efforts to combat drug related problems have typically centered around substances like cocaine; nonetheless marijuana has also played a role in Colombia’s drug landscape in terms of both production and consumption patterns. At present a bill advocating for the legalization of marijuana for adults is progressing through Congress. This proposal has raised apprehensions regarding its effects, on the populace. It highlights the significance of studying how marijuana affects behaviors such, as aggression and victimization.

Conclusions

This study highlights a link between adolescent marijuana use and increased reports of aggression and victimization. While marijuana use itself appears to be a significant predictor of aggressive behaviors, its influence cannot be fully understood without considering the broader landscape of substance use patterns. Our findings underscore the importance of examining the interplay between marijuana and other substances, as these combined or sequential patterns may intensify risks and alter developmental trajectories.

By recognizing that not all adolescent substance users are alike, targeted public policies and school-based interventions can be developed to address the specific needs of distinct subgroups. Future research should continue to disentangle the relative impacts of different substances and explore potential interactive effects among them. Longitudinal studies are particularly important for capturing the temporal and causal relationships between early substance use and long-term behavioral outcomes. Ultimately, a better understanding of these dynamics can inform effective prevention and intervention strategies to reduce aggression and victimization among adolescents.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, although we controlled for key demographic variables and distinguished among different patterns of drug use, other unmeasured confounders related to aggressive behavior such as the frequency and intensity of marijuana use, underlying mental health issues, or the broader social environment, may have influenced the observed associations. Second, the use of cross-sectional data limits our ability to identify causal relationships. Third, our measures of aggression and victimization were based on self-reported behaviors, which may be subject to recall bias or social desirability concerns. Fourt, while this study outlines potential pathways through which marijuana use may contribute to aggressive behaviors, it does not account for the role of consumption quantity or method in activating these pathways. The data utilized did not include information on the intensity, frequency, or method of marijuana consumption, factors essential for understanding whether any amount is sufficient to trigger these behaviors or if a specific threshold exists. Additionally, the available data did not include more detailed socioeconomic indicators, neighborhood context, or school-level factors, limiting our ability to fully disentangle the effects of marijuana use from broader social and environmental influences. Future research should incorporate longitudinal designs, richer contextual variables, and more refined substance use measures to address these limitations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between marijuana use, aggression, and victimization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Colombia’s Drug Observatory for providing the data.

-

Research ethics: This study involved the analysis of an existing governmental dataset that was fully anonymized and publicly available. The data was collected and shared by the government in compliance with applicable legal and ethical standards, ensuring that no individual subjects could be identified.

-

Informed consent: No applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: Large Language Models were used to check grammatical accuracy after the manuscript was written. Suggestions from the tool were considered but not always accepted.

-

Conflict of interests: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The R scripts used in this study are available upon request. The data is publicly accessible through the Colombian Observatory of Drugs.

References

1. Hammond, CJ, Allick, A, Park, G, Rizwan, B, Kim, K, Lebo, R, et al.. A meta-analysis of fMRI studies of youth cannabis use: alterations in executive control, social cognition/emotion processing, and reward processing in cannabis-using youth. Sci Rep 2022;12:1281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12202-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Volkow, ND, Baler, RD, Compton, WM, Weiss, SRB. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2219–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1402309.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report; 2024. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2024.html.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Ostrowsky, MK. Does marijuana use lead to aggression and violent behavior? J Drug Educ 2011;41:369–89. https://doi.org/10.2190/DE.41.4.c.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Bauman, S, Taylor, A. Agression and victimization. In: Emerging trends in the social and behavioral Sciences. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015:1–14 pp. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0005.10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0005Suche in Google Scholar

6. Lester, L, Cross, D, Dooley, J, Shaw, T. Developmental trajectories of adolescent victimization: predictors and outcomes. Soc Influ 2013;8:107–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2012.734526.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Moore, TM, Stuart, GL. A review of the literature on marijuana and interpersonal violence. Aggress Violent Behav 2005;10:171–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2003.10.002.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Hathaway, AD. Marijuana and lifestyle: exploring tolerable deviance. Deviant Behav 1997;18:213–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.1997.9968056.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Earleywine, M. Social problems. In: Understanding marijuana: a new look at the scientific evidence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003:197–222 pp.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195138931.003.0009Suche in Google Scholar

10. Dellazizzo, L, Potvin, S, Athanassiou, M, Dumais, A. Violence and cannabis use: a focused review of a forgotten aspect in the era of liberalizing cannabis. Front Psychiatr 2020;11:567887. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.567887.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Gao, Y. Epidemiology, health implications, and resilience factors in adolescent marijuana use: a comprehensive review. Eur J Prev Med 2023;11:75–81. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ejpm.20231105.13.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Gray, KM, Squeglia, LM. Research review: what have we learned about adolescent substance use? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017;59:618–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12783.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Dvorak, RD, Day, AM. Marijuana and self-regulation: examining likelihood and intensity of use and problems. Addict Behav 2014;39:709–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.001.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Ali, MM, Amialchuk, A, Dwyer, DS. The social contagion effect of marijuana use among adolescents. PLoS One 2011;6:e16183. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016183.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

15. Hyman, SM, Sinha, R. Stress-related factors in cannabis use and misuse: implications for prevention and treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009;36:400–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. DuPont, RL, Han, B, Shea, CL, Madras, BK. Drug use among youth: national survey data support a common liability of all drug use. Prev Med 2018;113:68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Orlando, M, Tucker, JS, Ellickson, PL, Klein, DJ. Concurrent use of alcohol and cigarettes from adolescence to young adulthood: an examination of developmental trajectories and outcomes. Subst Use Misuse 2005;40:1051–69. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-200030789.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Shamblen, SR, Miller, T. Inhalant initiation and the relationship of inhalant use to the use of other substances. J Drug Educ 2012;42:327–46. https://doi.org/10.2190/DE.42.3.E.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Wall, M, Cheslack-Postava, K, Hu, MC, Feng, T, Griesler, P, Kandel, DB. Nonmedical prescription opioids and pathways of drug involvement in the US: generational differences. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;182:103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Lynskey, MT, Agrawal, A. Kandel’s classic work on the gateway sequence of drug acquisition. Addiction 2018;113:1927–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14190.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho, Ministerio de Educación Nacional. Estudio nacional de consumo de sustancias psicoactivas en población escolar - colombia 2016. Bogotá, D.C: Observatorio de Drogas de Colombia; 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Evaluating the relationship between marijuana use, aggressive behaviors, and victimization: an epidemiological study in colombian adolescents

- Enhancing adolescent health awareness: impact of online training on medical and community health officers in Andhra Pradesh, India

- Development of the “KARUNI” (young adolescents community) model to prevent stunting: a phenomenological study on adolescents in Gunungkidul regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Energy drinks, depression, insomnia, and stress in palestinian adolescents: a cross-sectional study

- Characterization of the most common diagnoses in a population of adolescents and young adults attended by a Healthcare Service Provider (HSP) in Bogotá, Colombia

- Association of chronotype pattern on the quality of sleep and anxiety among medical undergraduates – a cross-sectional study

- Addressing emotional aggression in Thai adolescents: evaluating the P-positive program using EQ metric

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Original Articles

- Evaluating the relationship between marijuana use, aggressive behaviors, and victimization: an epidemiological study in colombian adolescents

- Enhancing adolescent health awareness: impact of online training on medical and community health officers in Andhra Pradesh, India

- Development of the “KARUNI” (young adolescents community) model to prevent stunting: a phenomenological study on adolescents in Gunungkidul regency, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

- Energy drinks, depression, insomnia, and stress in palestinian adolescents: a cross-sectional study

- Characterization of the most common diagnoses in a population of adolescents and young adults attended by a Healthcare Service Provider (HSP) in Bogotá, Colombia

- Association of chronotype pattern on the quality of sleep and anxiety among medical undergraduates – a cross-sectional study

- Addressing emotional aggression in Thai adolescents: evaluating the P-positive program using EQ metric