Abstract

With democratic decay advancing around the globe, scholars deeply disagree about courts’ ability to protect democracy. I argue that this divergence is influenced by conceptual and theoretical deficiencies of the debate. The existing approaches to judicial responses to democratic decay often do not pay sufficient attention to the differences among courts and the environments in which they operate. To tackle these issues, this article introduces the judicial countering capacity frame as an analytical tool to guide further empirical analysis. The framework recognizes courts’ agency but emphasizes the constraints and resources stemming from the environment in which a court operates. Moving away from single-factor explanations, I make a case for a multicausal understanding of judicial countering of democratic decay. I argue that the extent of a court’s countering capacity rests on three pillars: institutional design, the level of political pluralism, and political culture towards courts. The judicial countering capacity frame invites an empirically oriented agenda focusing on micro-mechanisms of judicial countering, their effectiveness, structural preconditions, and the plausibility of available judicial strategies. The article demonstrates the new frame on case studies of Colombia, South Africa and Poland.

1 Introduction

Are courts able to counter the current wave of democratic decay driven by powerful executives? Scholars have recently devised a plethora of answers to this grand question. However, they deeply disagree with each other. Some put high hopes in courts and envisage them as the ‘Swiss army knives’ of democracy.[1] Some see courts as powerless victims of court-curbing and capture. And some view judges as part of the problem rather than the solution. Legal-political reality is similarly diverse. One can find examples supporting any of those positions. The Latin American context, for instance, offers a telling twin example. In 2010, the Colombian Constitutional Court blocked the President’s attempt to eliminate existing term limits. The Court held that a third presidential term would threaten Colombia’s democracy by allowing excessive cumulation of power.[2] Facing a similar situation, the Bolivian Constitutional Tribunal decided the other way. It abolished presidential term limits for violating the candidate’s political rights. Several scholars reported that this judgment paved the way for further entrenchment of the executive power in Bolivia.[3]

These theoretical divergences and variations in judicial practice form the starting point of this article. While many academic writings begin with a statement that we know surprisingly little about a topic, my point is the opposite: we know quite a lot about courts and democratic decay. There is an ever-increasing number of case studies of judicial involvement in democratic decay and its countering, supporting one or another of the theoretical positions. Yet, these accounts are often underspecified as to the conditions under which a certain outcome takes place. Consequently, the debate gets fragmented and the necessary cross-conversations are largely lacking. The focus on the grand question whether courts are good or bad at protecting democracy seems to have obscured important distinctions. We have reached a point where it is necessary to pause, take stock of our knowledge about courts and democratic decay, and to consolidate our conceptual toolkit. My aim is to use the rich and insightful but divergent existing approaches to best effect by constructing a focused theory frame that bridges the fragmentation.[4]

Specifically, I introduce a novel theory frame focusing on the capacity of courts to counter democratic decay, or judicial countering capacity. It captures apex courts’ varying ability to counter episodes of autocratization.[5] It focuses on how well a court is situated to counter democratic decay and what features influence that. The frame goes beyond the single-factor explanations and, instead, offers a multi-factor frame combining legal and socio-political features. It recognizes both judicial agency and the constraints and resources stemming from the environment in which a court operates.[6] Specifically, I argue that judicial countering capacity rests on the interaction among three pillars:

Institutional design of a court, understood as a set of rules, procedures and organizational structures enabling and constraining the court’s actions.[7] The core question is what risks and resources are built into a court’s design. Based on the recent court-curbing experiences, particular attention is paid to capture-proofing design features concerning judicial career rules (appointment, transfer, removal) and the court’s structural features, especially access rules and jurisdictional reach.

Level of political pluralism, understood broadly as a reasonably competitive political system where non-partisan independent institutions operate. The core question is how valuable other actors’ support for the judicial countering efforts is. I go beyond the traditional emphasis on inter-party competition and focus also on intra-party dynamics and non-partisan actors supporting courts’ countering efforts, such as the fourth-branch institutions and international courts.

Political culture towards the judiciary, understood as traditions, habits and patterns of behaviour shaped by a society’s prevailing political beliefs, norms and values which affect the way in which the judiciary is seen and valued.[8] The core question is whether the prevailing political culture increases the costs of court-curbing and disrespecting law. While various factors affect political culture, I pay special attention to authoritarian populism for its ability to justify resistance to existing institutional boundaries in the name of ‘real’ democracy.

Additionally, both judges and political rulers can use their agency to alter these pillars. Judicial countering of democratic decay thus unfolds as a complex process, which is dynamic, interactive and reflexive.

There is an urgent need for a unifying framework of this kind. On the one hand, judges have been seen as the major protectors of democracy, especially post-Cold War. On the other hand, courts have become the frequent targets of the autocratic rulers driving democratic decay. Various court-curbing strategies have cast doubts on the actual judicial capacity to counter democratic decay. Accordingly, to devise effective responses to democratic decay it is necessary to recognize the main risks and resources for judicial countering of democratic decay by identifying the most vulnerable and the most resilient features affecting judicial efforts to counter democratic decay. In the first place, we need a conceptual and theoretical basis for distinguishing among courts and making more nuanced claims about what courts can achieve under what conditions. To be clear, this article focuses on the descriptive question of courts’ effectiveness in protecting democracy. While the normative question whether courts should (or must) protect democracy is important,[9] I leave it aside in this article as it raises a different set of questions and requires a different methodological approach.

The judicial countering capacity frame has three main advantages. First, it is based on accumulated knowledge which connects the fragmented debates in judicial studies with the literature on democratic decay and democratic resilience. Second, it creates conceptual room for taking relevant contextual factors into account and discourages premature generalisations. Third, it allows a consistent analysis of multiple cases and generation of more detailed hypotheses, as it singles out a set of relevant factors. This has several implications for future research. The theory frame builds on configurational thinking. It envisages multiple possible ways in which a combination of factors produces a given effect and moves towards a multicausal understanding of judicial countering of democratic decay. The judicial countering capacity frame thus invites a refocusing from the grand question whether courts are good or bad at protecting democracy to a less formidable but fruitful agenda concentrating on mechanisms of effective judicial countering of democratic decay. This way, it also transcends the dichotomous accounts in several contemporary debates, such as the discussion about the (ir)relevance of institutional design in countering democratic decay.[10]

The rest of the article proceeds as follows. Part 2 revisits and systematizes the recent approaches focusing on the role of courts in countering democratic decay. The idea is to get the theoretical gist of the existing scholarship and use it for devising a more focused and structured theory frame.[11] Part 3 introduces the judicial countering capacity frame. I analyse the roles of institutional design, political pluralism, and the political culture towards the judiciary. Subsequently, I explain the significance of judicial and political actors’ agency for changes in the judicial countering capacity. To show that it is the interaction of these factors that matters and to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed frame, Part 4 includes illustrative case studies from Colombia, South Africa and Poland. Part 5 concludes.

2 Courts and Democratic Decay: Mapping the Divergence

After the Cold War, the vast majority of new democracies established constitutional courts to facilitate democratic transitions and act as ‘downstream democratic consolidators.’[12] Recently, however, attention has turned from democratic consolidation to a contrary process of democratic decay, which denotes ‘the incremental degradation of the structures and substance of liberal constitutional democracy.’[13] The current democratic decay is typically driven by executive aggrandizement, which occurs ‘when elected executives weaken checks on executive power one by one, undertaking a series of institutional changes that hamper the power of opposition forces to challenge executive preferences.’[14] The degradation of structures thus typically concerns the elimination or neutralization of non-majoritarian checking institutions, while the degradation of the democratic substance touches mainly upon democratic norms and the political actors’ willingness to play by the rules.[15] Unlike sudden authoritarian reversions, decay is incremental. It consists of a series of steps, each of which might be tolerable. Their combination, however, leads to a considerable weakening of democratic checks.[16] Compared to earlier authoritarians, current architects of democratic decay rely extensively on constitutional and legal forms rather than violence and extra-legal measures.[17] Finally, democratic decay is not limited to new or weak democracies. It has affected several democracies previously thought to be well consolidated.[18]

One of the recent major topics in comparative constitutional studies has been what constitutional institutions can do about democratic decay.[19] Some stress the need to address the underlying socio-economic macro-causes of democratic decay,[20] while others emphasize the immediate mechanisms capable of countering such decay. Within the latter dimension, many have zeroed in on courts, given their role in democratic consolidation. Countering democratic decay is different, though. While democratic consolidation puts emphasis on the prospective and constructive roles in creating a democratic order, countering democratic decay requires a protective role defending fundamental democratic features from being destroyed.[21] The source of concern emerges from the present rather than the past.[22] This setting seems to be more challenging for the judiciary: ‘Transitions to democracy seem to be accompanied by an expansion of judicial power, but transitions away from it often involve a contraction.’[23] Indeed, courts have become one of the first targets of the ruling actors’ efforts to avoid accountability. Reacting to this trend, Daly argued that ‘[t]o anyone viewing courts as a central bulwark for threatened democracies, recent years have been a sharp reality check.’[24]

Accordingly, courts’ actual capacity to effectively counter democratic decay has been questioned and has produced a considerable amount of scholarship. Most of the existing approaches in comparative constitutional law combine descriptive claims with explicit or implicit normative elements. This article focuses on the approaches closer to the descriptive and analytical part of the spectrum and leaves the normative dimension aside.[25] The following sections provide a systematization of existing literature according to the significance of the judicial role in countering democratic decay (see Table 1).

Courts and countering of democratic decay: classification of current approaches.

| Judicial role | Key idea | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | Courts as guarantors of democracy | Judge-led democracy-protecting efforts |

| Weak | Courts as speedbumps | Courts creating room for other pro-democracy actors |

| Insignificant | Courts incapable of countering decay effectively | Judicial susceptibility to backlash |

2.1 Strong Judicial Role

Many scholars see courts as actors capable of countering democratic decay. Yet, they largely differ as to the strength of the judicial role and the mechanism of judges’ contribution. I broadly distinguish between a strong and weak role ascribed to courts in countering democratic decay. Although the dividing line is blurred, the strong role sets ambitious tasks for the judiciary. These approaches portray courts as (one of) the major protectors of democracy and see countering democratic decay as a judge-led enterprise. This position has been widely shared, almost as a default one, after the Cold War.[26] I will focus specifically on Samuel Issacharoff’s work, as he provided one of the most transparent and sophisticated accounts of the strong reliance on courts.[27]

Issacharoff’s book, Fragile Democracies, is characteristic of a rather strong emphasis on the courts’ democracy-protecting role. Exploring how fragile democracies secure the stability of their constitutional orders against the challenge of sliding towards authoritarianism, Issacharoff focuses on constitutional courts. He does not reduce the protection of democracy to a purely judicial enterprise and recognizes the role of other actors. But he stresses the significance of the judicial element, labelling constitutional courts ‘the major institutional enforcers of the bargained for constraint,’[28] and ‘guarantors of democracy.’[29] Specifically, Issacharoff sees them as protectors against dominant political actors striving for one-partyism: ‘in many countries strong constitutional courts have served as a stopgap against efforts of the rulers of today to manipulate the powers of governmental authority to secure their permanence in office.’[30] While recognizing courts’ vulnerability and the possibility of backlash, he states that ‘where political competition lags or fails, these courts are often the only institutional actor capable of challenging an excessive consolidation of power.’[31]

2.2 Weak Judicial Role

The recent wave of democratic decay, however, seems to have curbed the once widespread optimism about judicial protection of democracy. Many scholars still see courts as actors playing an active role in countering democratic decay but focus on more modest judicial roles. A frequent claim is that courts are unlikely to save the day on their own but can alter the course or pace of democratic decay. Such alterations can create room for other actors to reunite, get involved and coordinate pro-democratic efforts.

These approaches frequently liken courts to speedbumps. Examining democracy-protecting constitutional design, Huq, Ginsburg and Versteeg conclude that there is no foolproof design to immunize liberal democracy from backsliding. At best, they view constitutional design features, including constitutional courts, as ‘speed bumps to slow the agglomeration and abuse of political power.’[32] Similarly, Bugarič claims that courts alone are unlikely to defeat a powerful and determined government aiming to dismantle the rule of law institutions. Nonetheless, he posits that constitutional courts can serve ‘as “speed bumps” to slow the deconsolidation of liberal democracy.’[33] Roznai argues that courts can fulfil the function of a ‘useful speed bump or stop sign’ since ‘judicial decisions may slow down – even if not completely stop – authoritarian initiatives until different political actors gain power.’[34]

Huq and Ginsburg explain the significance of the speed bump function. First, a judgment authoritatively declares the illegality of the reviewed measure that endangers democracy. After all, the current autocratic leaders are often surrounded by teams of lawyers and use the law extensively to enforce and justify their policies.[35] A judicial decision eliminates doubts about the permissibility of such measures. Second, it may help regime opponents to rally supporters to their cause. A judgment declaring unlawfulness can enable the coordination of regime opponents’ response.[36] Thereby, courts reduce the information and coordination costs of monitoring the ruling party.[37] Accordingly, judicial safeguards of democracy work as time-buying mechanisms for democracy defenders to regroup for a renewed electoral challenge.[38] Thus, Ginsburg and Huq argue, a well-timed judicial decision can make the difference between ‘a near miss and a fatal blow.’[39] In this view, ‘courts are not great heroes here. … Courts operate by providing high-quality information to publics and elites. But the action taken to protect democracy from erosion is taken by other actors, not courts themselves.’[40]

2.3 Judicial Insignificance

Other scholars are much less optimistic. Besides general concerns about courts’ institutional capacity and epistemic limitations,[41] they doubt judicial resilience vis-à-vis autocratic forces. While the post-Cold War literature emphasized the power of judges and the coming juristocracy,[42] debates about de-judicialization and post-juristocracy have emerged more recently.[43] Court-packing, jurisdiction stripping, budget cuts, the delegitimization of judges and other court-curbing strategies have spread across continents and shown the fragility of the judicial power.[44] These developments have led many to argue that courts are not as effective protectors of democracy and fundamental rights as commonly believed.[45] The greatest concern comes from the courts’ susceptibility to backlash. Various measures can be used to paralyze courts, prevent them from issuing consequential decisions and even drag them to the rulers’ side by changing their composition.

As a telling example, Sadurski points to the fate of the Polish Constitutional Tribunal, which was paralyzed and captured by a populist government. Based on that, he stresses the incapacity of constitutional institutions such as constitutional courts to protect democracy ‘against a dishonest President “appointing” improperly elected “judges”, and the executive refusing to comply with judgment,’[46] and makes a general point about the ‘relative irrelevance of constitutional design.’[47] Instead, Sadurski stresses the significance of widely shared and respected unwritten norms as the crucial feature of constitutional resilience.[48] Levitsky and Ziblat concur that institutional safeguards like constitutional courts are less effective in protecting democracy than is usually assumed. Without widely shared political norms of mutual toleration and institutional forbearance, courts can become easy targets for the strongmen.[49] In the worst-case scenario, a court is captured and used to advance the rulers’ non-democratic goals, rather than counter them.[50]

Yet another group of scholars goes further and views courts not merely as insignificant actors but rather as part of the problem. They claim that excessive judicialization contributed to feelings of a lacking control over important socio-political issues, to discontent with liberal democracy and surging support for anti-systemic parties. Court-centred versions of liberal constitutionalism are thus blamed for being complicit in democratic decay.[51] While this argument is important, it addresses a different question from this article’s. It focuses on causes of democratic decay rather than ways of countering it. Accordingly, I leave this strand of literature aside.

3 Towards Convergence: The Judicial Countering Capacity Frame

At first sight, the existing approaches give radically different answers – sometimes to the extent of contradictions – to the question whether courts can counter democratic decay. Which one is right then? My point is that they can all be right. The key to understanding the theoretical divergence lies in the underlying assumptions and theoretical foundations of the debate. The three groups differ in their reasons for ascribing courts either strong, weak or insignificant roles in countering democratic decay. To start with, there is a clash about the importance of institutional design.[52] Whereas scholars closer to the strong judicial role position allude to the significance of constitutional institutions and the way these are designed,[53] those seeing courts as rather insignificant are sceptical about the role of design. Instead, they emphasize the prevailing political norms as the core aspects of democratic resilience.[54] The group closer to the weak judicial role shifts attention to the features of the broader ecosystem in which courts operate and stresses courts’ dependence on partnerships with other actors.

While all these points sound right, courts and their surroundings differ vastly along these lines. Democratic decay is a complex, dynamic and interactive process. So is its countering. The two processes have different starting points, trajectories and varying paces across countries. Different courts are differently placed to withstand a backlash, and they operate in different political, institutional, and cultural landscapes. Therefore, an analysis of courts’ ability to protect democracy must consider these important distinctions, the proverbial differences that make a difference. This part aims to bridge the fragmentation and divergence in the literature. It uses the rich insights provided by the existing scholarship and further develops them on the basis of recent research on democratic resilience and protection of democracy.[55] Specifically, I offer a new way of organizing our thinking about courts’ capacity to counter democratic decay and make a case for refining the debate by looking at how a constellation of enabling conditions bolsters courts’ capacity to counter democratic decay.

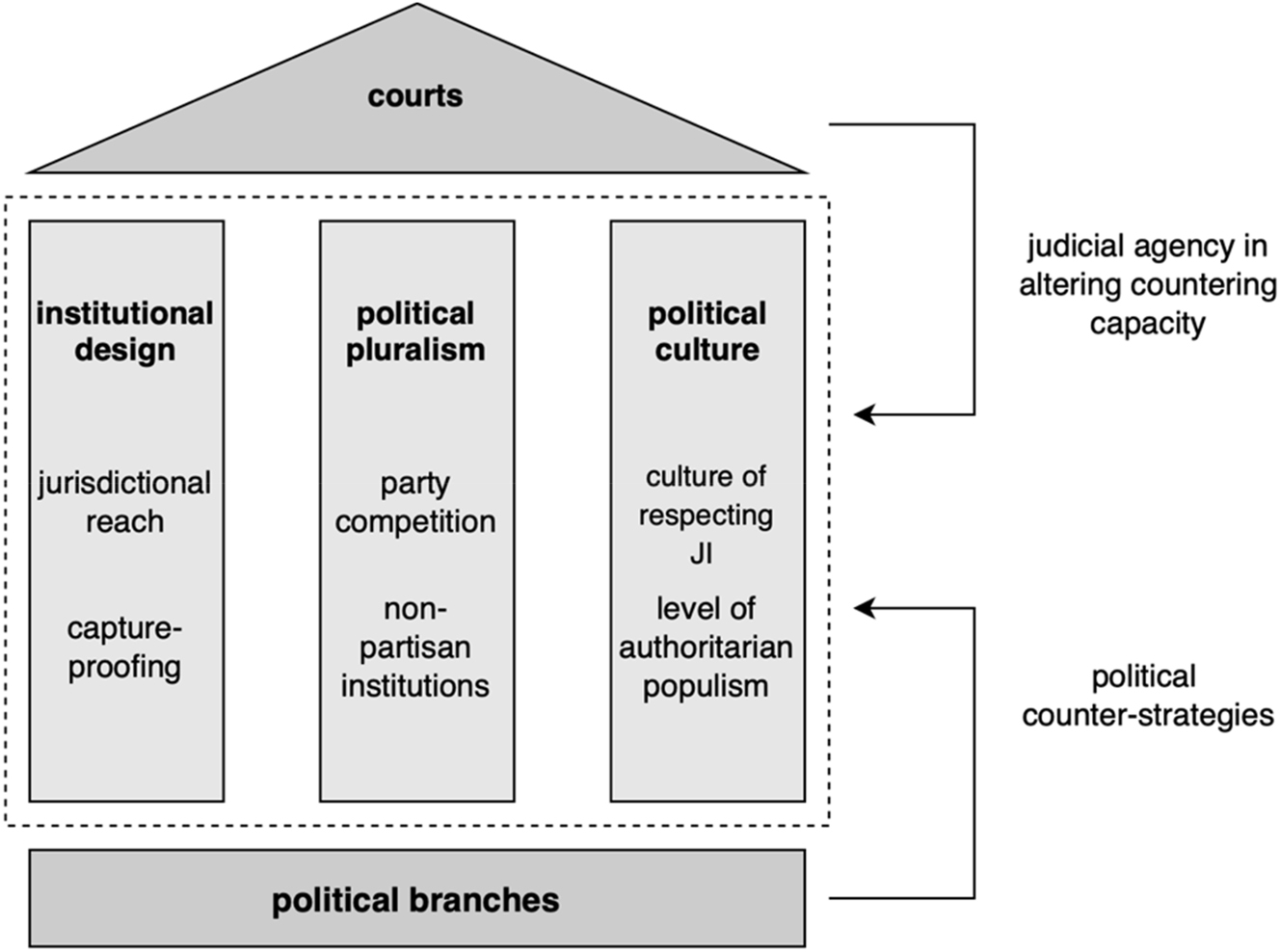

The rest of this article introduces the idea of judicial countering capacity: a focused theory frame accounting for why some courts are better positioned to counter democratic decay than others. It captures how well a court is situated to counter democratic decay and what features determine it. I move away from single-factor explanations and present judicial countering capacity as a multicausal phenomenon: configurations and interactions of several factors are crucial. These factors are not merely a matter of the separation of powers arrangements, or a merely political matter. Judicial countering capacity is a composite consisting of legal, political and socio-political features (see Figure 1). It emphasizes the role of constraints and resources stemming from the environment in which a court operates, but also acknowledges the dynamic dimension: the agency of courts and the political branches in modifying judicial countering capacity.

The architecture of judicial countering capacity.

Specifically, I argue that the extent of a court’s countering capacity rests on the interaction of three pillars of judicial resilience – institutional design, the level of political pluralism, and the prevailing political culture towards the judiciary – and on the agency of the courts and political actors. The three pillars can provide structural resources for courts to counter democratic decay but, also, structural constraints if they provide political branches with opportunities for resisting courts: ignoring them and employing court-curbing strategies. However, judicial countering capacity is not static. Both courts and political branches have some agency in modifying the pillars, as they can act in ways aimed at altering judicial countering capacity.

As a result, two ideal typical configurations emerge: courts with extensive and narrow countering capacity. Courts operating in an environment in which all three pillars are relatively solid – the court has a somewhat capture-proof design, reasonable pluralism still exists in the political field and the prevailing political culture makes court-curbing costly – have an extensive countering capacity. Their jurisdictional reach allows them to intervene, their intervention is more likely to be complied with and they are quite well protected against backlash, at least in the short term. However, cracks in one or more pillars tend to reduce a court’s countering capacity. Narrow countering capacity tends to make courts susceptible to being inconsequential, ignored or targeted by backlash strategies. Nonetheless, the relationship between the pillars is fuzzy, based on substitutability rather than necessity. A minor crack in one pillar can be balanced by the remaining pillars. Larger cracks, however, tend to be problematic, especially if occurring in more pillars simultaneously. The following sections demonstrate the significance of the structural features as well as the strategies and counterstrategies aimed at modifying them.

3.1 Institutional Design

The approaches pointing to judicial incapacity to protect democracy emphasize courts’ susceptibility to backlash and refer to various court-curbing strategies that have been successfully used to neutralize previously powerful courts. Institutional design plays a double-edged role here. On the one hand, poor design can contribute to the court’s incapacity to rule on problematic policies and facilitate court-curbing. On the other hand, sensible institutional design can discourage court-curbing and reshuffle the risks and opportunities related to backlash against the judiciary.

One question thus is whether design allows the court to intervene at all. The issue at stake must be within the court’s jurisdictional reach, which consists of the court’s competences, access rules and factual operability – a court must be able to review the given measure, get hold of an actual case and be able to decide. Additionally, to improve the countering capacity, the court’s design must provide some sort of security of survival in the event of a clash with the ruling majority. Otherwise, the court might not be able to face the government’s eventual retaliation. Dothan argued that a court cannot uphold the respective standards if doing so would significantly jeopardize its own future: ‘backlash should be considered by the court as it makes its decisions. The court cannot go on suicide missions.’[56]

Therefore, another question is whether institutional design provides the court with some protection against backlash and court-curbing, particularly against inoperability and capture. If the court is inoperable or paralysed, it may not be able to rule on the issue at stake at all. If the court is captured and re-staffed with government loyalists it is unlikely to be willing to counter the rulers’ policies, at least the crucial ones. Accordingly, two sets of rules are particularly important here:[57] those concerning the structural features of a court (such as delimitation of jurisdiction, access rules, procedural rules, budget) and rules on judicial appointment, removal, transfer, promotion or demotion. Some court-curbing techniques target the court’s structural features, aiming to reduce its ability to tackle certain issues. Limiting access makes the court less likely to be activated. Jurisdiction stripping restricts the court’s reach. Radically reducing the court’s budget can make it ineffective or inoperable. Meddling with the procedural rules can decrease the court’s operability and even paralyse it. Yet, targeting the court’s structural features is visible and prone to domestic and international critique, hence politically costly. Consequently, judicial career rules are often exploited instead, with the aim of keeping the court operating but changing its composition. The goal is to neutralize the court’s veto power through ideological approximation of the bench to the government’s positions. Court-packing and other techniques aimed at replacing disloyal judges with the loyal ones are instrumental in this respect.[58]

Capture-proofing a court’s design should aim at making the named techniques harder, or at least more costly, to employ. One way is the constitutional entrenchment of the fundamental aspects of the court’s structural features to separate ordinary politics from a constitutional overhaul. As regards judicial appointments, staggered appointment mechanisms based on the co-decisionmaking of a plurality of actors provide some protection against large-scale unilateral appointments condensed in a short period of time that would allow for the extreme politicization of the bench.

Scholars have argued about the (ir)relevance of institutional design in safeguarding democracy.[59] The judicial countering capacity frame shows that the debate about institutional design is part of a much broader issue. Institutional design is but one part of a wider configuration of pillars of judicial countering capacity. It depends on its interaction with the other pillars. Appropriate design features can increase judicial countering capacity by making it easier for the court to rule on the issue at stake and by providing some protection against court-curbing. However, it seems that no design is totally resistant to abuse, particularly if the rulers hold a constitutional majority. Still, the point of capture-proofing is not to rule court-curbing out completely. Rather, it is about the distribution of costs. The attainable goal is to make court-curbing more visible, more costly and less likely, especially in combination with the resources stemming from the other pillars of judicial countering capacity: political pluralism and political culture.

3.2 Level of Political Pluralism

Apex courts’ institutional design interacts with the broader political environment in which courts operate. One take-away insight from the scholarship pointing to the weak judicial role in protecting democracy is that judicial efforts are often not an isolated endeavour. Rather than superheroes saving the day themselves, judges are seen as sidekicks with special skills used to create room for a pro-democratic response by other actors. Neo-Elyian theories then stress the judicial task of cleaning channels of the political process and allowing other actors to participate.[60] For this synergy between courts and other actors to work, however, a fair amount of political pluralism must be in place.[61] Accordingly, I understand political pluralism broadly as a pluralistic political ecosystem – a reasonably competitive political system where non-partisan independent institutions exist. It is the opposite of ‘one-partyism’, i.e., a centralized system in which all actors are controlled by a single party.[62] If all the actors are controlled by the ruling majority, they can hardly provide the necessary support to courts, boost their countering capacity and function as partners in countering decay. Accordingly, political pluralism requires certain institutional prerequisites.

The existing scholarship has emphasized party competition as an essential enabler of judicial authority. Generally, if the party system is competitive enough, a risk-averse governing party is motivated to keep courts relatively powerful and independent should it become a loser one day.[63] The strength of the opposition becomes crucial. If the political opposition can plausibly picture itself as the next electoral winner, the political uncertainty about the next election can increase judicial countering capacity. The prospect of the opposition’s victory can lead even previously loyal judges to strategic defection and challenging the incumbents.[64] In the context of democratic decay, however, opposition parties are often weak compared to the aggrandized ruling majority. If the opposition is decimated or fragmented, without a reasonable chance of challenging the ruling party, its support has limited implications for bolstering the court’s countering capacity.[65]

Inter-party competition, however, is not the only mechanism increasing judicial countering capacity. First, intra-party dynamics also matter. Second, the political environment is much broader than parties. Courts operate in a complex network of domestic, international and transnational actors who extend the pool of courts’ potential partners. Some of them can act as valuable allies working in synergy with courts and increasing their countering capacity. Two types of such actors have become particularly relevant in the current wave of (countering) democratic decay: fourth-branch institutions and international courts.

Since the party-political competition does not seem sufficient to fully guarantee the endurance of democracy, several countries introduced institutions charged with protecting constitutional democracy: the fourth branch or guarantor institutions.[66] These include electoral commissions, ombudspersons, anti-corruption watchdogs, knowledge institutions, etc. They aim to take some of the burden of protecting democracy off the courts’ shoulders and guarantee democracy by different means. As Tushnet stressed, ‘A constitutional court might fail to protect the constitution against a specific threat, but perhaps the nation’s ombudsperson will do so – or the nation’s auditor general, or its public prosecutor.’[67] The option of such actors stepping in and protecting democracy is one possibility. After all, courts may fail and have failed on numerous occasions. Another option, however, is that fourth-branch institutions and courts act in synergy. Rather than replacing one another, they may supplement each other’s efforts with their own activities and institutional strengths. Fourth-branch institutions are specialized actors and their methods and powers vary. Ombudspersons, for instance, can lead investigations, name and shame, communicate with the media and mobilize the public, arguably better than most judges. Courts, however, are endowed with institutional strengths (independence and impartiality, specific reasoning methods and the binding nature of their decisions), which can further reduce the information and coordination costs of monitoring the government and bolster the effectiveness of the ombudsperson’s findings.

The pool of eventual allies is even larger as it reaches beyond the state. A number of international and regional organizations increasingly focus on democracy-supporting activities.[68] In addition, the expansion of judicial power after the Cold War has taken place not only domestically, but also on the international plane. International courts have proliferated and some of them have gained considerable authority, particularly thanks to partnering with domestic audiences.[69] Such interconnectedness between national and international legal orders can be seen as an extra protective layer of democracy and a major resource for increasing the countering capacity of domestic courts. Committing to the jurisdiction of an international human rights court was described as a lock-in mechanism to consolidate democracy vis-à-vis non-democratic political threats.[70] Embeddedness of international human rights law in domestic courts’ case law was then understood as an extra safeguard for mitigating harmful policies of authoritarian populists.[71] These transnational partnerships have helped in the judicial countering of democratic decay on some occasions.[72] However, as Section 3.4 below shows, these partnerships can also be manipulated and dismantled by the governments’ counteractions.

In sum, judicial countering capacity depends on pluralism in the political environment in which a court operates. It partly rests on synergies with other actors who can bolster courts’ efforts in guarding democracy. While inter-party competition is crucial, intra-party dynamics and various non-partisan actors are also important. The pool of potential partners includes domestic non-partisan institutions and international actors. The next pillar of judicial countering capacity – political culture towards the judiciary – warns, however, that the value of such partnerships can be reduced by rhetorical attacks portraying non-majoritarian institutions as deformations of the popular will.[73]

3.3 Political Culture Towards Courts

As the aforementioned approaches pointing to courts’ insignificance in resisting democratic decay emphasize, unwritten political norms are important for the healthy functioning of a constitutional democracy. Indeed, besides institutional design and political pluralism, judicial countering capacity depends on the existence of a shared political culture of respecting judicial independence.[74] Political culture is important both as a matter of political actors’ strategic calculation and as a matter of their commitment to judicial independence.[75]

Political culture vis-à-vis the judiciary consists of traditions, habits and patterns of behaviour shaped by a society’s prevailing political beliefs, norms and values which affect the way in which the judiciary is seen and valued.[76] It is a ‘mental software’ surrounding the judicial system.[77] If the political culture of respecting law and judicial independence is well embedded and widespread, it can serve as a crucial backbone of judicial countering. It contributes to making respect for judicial independence a part of political actors’ role and increases public demand for respecting independence. That makes court-curbing more costly.

There may be various political and cultural obstacles to the development of such a culture. A culture of respecting judicial independence is not predestined to institutionalize. In some contexts, it can simply remain weak and underdeveloped.[78] In other contexts it can be disrupted. Currently, the major challenge seems to be the rise of authoritarian populism, which often fuels and accompanies democratic decay. On the one hand, populism has admittedly become a buzzword with overbroad meanings that fails to account for the full extent of the threats to constitutional democracy.[79] On the other hand, populism brings about several novel and distinctive challenges to judicial countering. Ignoring the populist imaginary that often accompanies current autocratization projects and treating them just like the old-fashioned 20th century authoritarianisms may blur the full spectrum of the problem.

Populism has acquired quite a widely shared understanding in political and constitutional theory. It is ‘an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.’[80] Müller adds that populists are also anti-pluralist and claim exclusive representation of the ‘real’ people.[81] Yet, there is a debate whether the anti-pluralist features are attributable to all varieties of populism.[82] Be that as it may, it seems that the authoritarian versions of populism dominate these days.[83] Therefore, I focus on authoritarian populism, i.e. the currently prevailing type of populism linked with significant ethnonationalist, anti-pluralist, and illiberal elements.[84]

What are the extra challenges brought about by authoritarian populism? Unlike the 20th century authoritarianisms, populism is based on a pro-democratic appeal and some form of democratic legitimacy. As Barber put it, ‘[p]opulists subvert constitutional government, but do so in a manner that brings much of the people along with them, and which allows – and requires – the basic structures of a democratic state to remain in place.’[85] Terms such as democratic self-government, constituent power, popular will and popular sovereignty are crucial for populists’ political claims. Yet, the populist constitutional vision gives a specific meaning to these concepts, a meaning that allows for significant contempt for previous institutional boundaries while maintaining the appearance of democracy. In the realm of the judiciary, this translates to populists’ skill in depicting judicial independence not as a means to ensure the rule of law, but as a bulwark allowing elitist judges to deform the genuine will of the real people.

The democratic parlance may be just a cloak covering authoritarian tendencies.[86] But it still allows populists to argue that breaking through the existing institutional boundaries and rejecting judicial authority are justifiable or even necessary for achieving true democracy and popular sovereignty. The populist political style takes large numbers of the people on board and shows itself to be capable of mobilizing parts of the public against the judiciary by including judges in the populist ‘narrative of blame’ explaining the roots of people’s dissatisfaction.[87] If that narrative is successful and resonates well, the public demand for judicial independence diminishes, which lowers the costs of court-curbing and judicial countering capacity. In fact, court-curbing is often accompanied by the populist reframing of such reforms. Moreover, the authoritarian populist framing seems to extend the perils of democratic decay to consolidated democracies too.[88]

3.4 Judicial Agency and the Dynamic Dimension of Judicial Countering Capacity

Institutional design, political pluralism and political culture towards courts represent the pillars forming the judicial countering capacity. Their mutual interactions co-determine whether a court is able to tackle a measure contributing to democratic decay, the prospects of compliance with the judicial pronouncement, and the probability of deterring or withstanding a backlash by the rulers. While most features within the three pillars are predetermined by the legal-political framework, they can change. First, sudden changes beyond the control of judges can shift the judicial countering capacity. Specific political moments and developments can create a window of opportunity when the court’s countering capacity temporarily increases due to a shift in the court’s political surroundings. A broad oppositional coalition challenging the rulers can emerge, for instance, or a schism in the dominant party can take place.[89] Worsening economic performance or corruption charges, for example, can incite social mobilization and increase political pluralism.[90]

Second, both judges and political rulers can step in and actively alter the pillars of judicial countering capacity. To extend their countering capacity, judges can use their agency in legal reasoning, treatment of previous decisions, case selection, fine-tuning of procedures, setting organizational goals, and designing communication strategies with external audiences.[91] From the long-term perspective, political scientists refer to judicial strategies aimed at extending the ‘tolerance interval’: the range of decisions rulers are willing to tolerate.[92] However, these accounts sometimes pay little attention to the legal preconditions for such judicial action.[93] Legal scholars thus stress the role of ‘doctrinal markers’: rulings that establish legal doctrines justifying later judicial interventions into areas previously regarded as off limits.[94] The court’s agency, however, is constrained (or empowered) by the existing legal framework, previous case law, doctrine, and the accepted ways of constitutional interpretation, which emerge as a result of both external and internal interactions of judges.[95] As Dixon and Roux argued, ‘courts can only ever succeed in implementing a constitution through arguments that the domestic legal culture accepts as legally plausible or legitimate.’[96]

In this way, judges can attempt to alter their countering capacity in all three pillars. In the context of institutional design, some courts have extended their jurisdictional reach by judicializing new policy areas and by empowering themselves to review sources of higher law (typically the unconstitutional constitutional amendments doctrine). Various domestic and international courts have also extended judicial review of decisions on judicial career,[97] which can contribute to capture-proofing institutional design. In the political pluralism pillar, courts have created legal mechanisms of partnering with other actors, e.g. with international courts by constitutionalizing international human rights treaties or by protecting the status and autonomy of fourth-branch institutions. Even in the political culture pillar, judges have engaged in various in- and out-of-courtroom efforts aimed at cultivating respect for the rule of law, judicial independence and judicial professionalism.[98] Yet, political rulers can respond with counterstrategies aimed at reducing judicial countering capacity. In the institutional design context, the governing majorities have thwarted judicial self-empowerment efforts by jurisdiction stripping.[99] They have managed to pack domestic courts and subsequently dismantle their partnership with international courts and other allies.[100] All this can be facilitated if the rulers manage to shift the understanding of judicial independence in the political culture pillar and portray judicial independence as an elite privilege allowing judges to deform the will of the real people.

Judicial countering of democratic decay thus unfolds as a dynamic, interactive and reflexive process; admittedly a complex one. The next part includes illustrative case studies or plausibility probes from various parts of the world to demonstrate the judicial countering capacity frame and its added value.[101]

4 Judicial Countering Capacity in Practice

The judicial countering capacity frame is not very well fitting for quantitative tools. As Part 3 suggests, the devil is often in the details that are hard to ascertain with quantitative approaches. In the context of institutional design, for example, even ‘small organizational and procedural details’ often matter for a court’s authority.[102] Consequently, the use of small-n case studies and process tracing seem like a better fit. Such approaches enable an incremental building of richer findings as to what resilience factors and their combinations are sufficient for effective judicial countering of democratic decay. That is short of answering the grand question whether courts are good or bad at protecting democracy, but the relatively abstract nature of the frame facilitates generalisations beyond single cases to the mid-range level.

This part analyses three cases: Colombia, South Africa, and Poland. They had experienced some level of democracy, faced a substantial risk of democratic decay fuelled by powerful executives, with courts involved in the process of countering (or advancing) the decay. Yet, they vary geographically and in the dynamics of judicial countering. All three cases have been well-documented. They are paradigmatic illustrations of the promises and pitfalls of judicial countering and epitomize the respective views on the judicial role in democratic decay summarized in Part 2 above. I include those not to provide new data – the analysis is based on existing country-specific scholarship – but to (1) demonstrate that one framework can explain cases with radically different outcomes, and (2) to show that case study approach can be useful for incremental theory-building as to what combinations of resilience factors and their interactions facilitate (or impede) effective judicial countering of democratic decay.

From that perspective, we can draw some tentative lessons from the three case studies. They unfold as multicausal stories of dynamic interactions between the pillars of judicial countering. These interactions, rather than any single factor, determine the options available to courts and the political rulers and create different configurations of judicial countering capacity. In this sense, the three interacting pillars seem to work as prongs of judicial resilience, united by the logic of determining the costs of backlash and non-compliance.[103] If political culture doesn’t make backlash costly and unacceptable, the court may still issue a consequential ruling and survive under some conditions. Partnership with another actor (political pluralism) may increase the costs of backlash, empower some actors, weaken others, and set further political processes in motion. Reasonably capture-proof institutional design may facilitate this scenario by making court-curbing too complicated, visible and/or time-consuming. In contrast, poor design may lower the costs of backlash, especially when combined with a political style attacking the culture of judicial independence and eroding the pluralist legal-political environment. These lessons, however, are tentative. There are surely other cases with different trajectories, scenarios and actors involved – such as the military and security forces, intra-court level issues, or economic developments – that are not considered here. The aim was to create a frame general enough to capture a wide variety of cases, but it is not infallible. Its transparent and structured nature at least facilitates its eventual revisions. In sum, this Part illustrates the feasibility and usefulness of the judicial countering capacity frame, rather than creates full theories.

4.1 Court Preventing Further Executive Entrenchment: Colombia

In 2002, Álvaro Uribe won the presidential election in Colombia with a programme focused on defeating the Colombian armed guerrilla groups. His policies gained him considerable support from the electorate. Yet, Uribe faced the obstacle of presidential term limits. The Constitution had introduced a single four-year term presidency to ensure rotation in that office.[104] However, a constitutional amendment was adopted that allowed for two consecutive terms. The Colombian Constitutional Court upheld the amendment and Uribe secured re-election in 2006.[105] During his second term, Uribe and his supporters initiated a referendum on amending the Constitution to allow the President to run for his third term. This time, the Constitutional Court blocked the attempt and argued that the third term could threaten Colombia’s democracy.[106] Uribe complied with the judgment, which led to alternation in power as Uribe’s successor, Juan Manuel Santos, was elected president. Scholars often invoke the Court’s 2010 intervention as a major demonstration of courts’ ability to counter executive aggrandizement and democratic deterioration.[107]

The Constitutional Court’s successful intervention was unique, though,[108] conditioned by the Court’s rather high countering capacity. It was based on a favourable interaction between the three pillars and the Court’s previous actions. Considering the Court’s institutional design, its formal competences limit its review of constitutional amendments ‘exclusively to errors of procedure in their formation’.[109] In 2003, nonetheless, the Court used its agency and increased its countering capacity by devising an important ‘doctrinal marker’:[110] the substitution of the constitution doctrine. It allows the Court to review the substance of a constitutional amendment, based on the argument that constitutional amendments can reform but not replace the existing constitution. These changes can only be achieved through a Constituent Assembly, not through a constitutional amendment procedure: ‘the derivative constituent power, then, lacks the power to destroy the Constitution.’[111] This judicial innovation increased the Constitutional Court’s capacity to counter democratic decay, especially in the context of a relatively easily amendable Colombian Constitution.[112] It allowed the Court to review the amendments on the first and second presidential re-elections. In the judgment on Uribe’s possible third term, the Court applied the substitution of the constitution doctrine. The judges concluded that allowing a second re-election would give the president too much power over other state institutions, which would destabilize the balance in the constitutional system.[113]

At the same time, the design of the Constitutional Court’s appointment mechanism, entrenched in the Constitution, reduced the chances of institutional capture. The original designers aimed to create a mechanism providing the Court with adequate independence.[114] One safeguard is the non-renewability of judicial terms. Another is the number of actors taking part in the selection process. The President, the Supreme Court and the Council of State each send a list of nominees to the Senate, which makes the final selection.[115] Based on that, Cepeda Espinosa and Landau argue that ‘no one actor or institution is able to play a decisive role in composing it,’ which fact played a crucial role before and after the Court’s decision on Uribe’s second re-election.[116]

The relatively strong institutional design was not the only factor that discouraged resistance against the Constitutional Court. It interacted with the political environment. Uribe’s coalition was quite diverse and internally fragmented. Accordingly, there was not a single strong political block to resist the court. In fact, Dixon and Landau argued, ‘many of [Uribe’s] rivals within his movement welcomed the decision because it created a new opportunity for them.’[117] Finally, the Court could rely on its previous capacity to withstand pressure and fend off court-curbing plans thanks to an emerging judicial independence culture based on the mobilisation of allied civil society actors, media, and the public.[118]

In sum, the Colombian case supports the claim that non-majoritarian actors can play crucial roles in preventing democratic decay.[119] However, analysing it within the judicial countering capacity frame adds that this was based on a specific configuration of crucial resilience factors: a reasonably capture-proof institutional design, developments in the political environment, the court’s previous case law that set the jurisprudential basis for the 2010 decision, and also its previous performance which had gained the court considerable popular support.

4.2 Court Maintaining Accountability: South Africa

Courts can also counter democratic decay by strengthening or restoring accountability mechanisms exercised by other actors. A case study from South Africa illustrates how an alliance between a court and a fourth-branch institution can boost efforts aimed at countering accountability avoidance. It also shows, however, that such a move was conditioned by a sufficient level of political pluralism. Specifically, the existence of autonomous non-partisan institutions and of internal splits within the dominant political party played a crucial role in the South African Constitutional Court’s efforts during Jacob Zuma’s Presidency.

Several authors have claimed that in Zuma’s period South Africa experienced democratic deterioration due to systemic corruption and eroding accountability mechanisms.[120] The Public Protector turned out to be a crucial actor in tackling these practices. It is a fourth-branch ombudsperson-type body created to strengthen constitutional democracy.[121] The Public Protector’s consequential impact, however, was made possible by the Constitutional Court’s intervention. Woolman described the whole story:[122] early in Zuma’s first term, journalists discovered that public money had been used to fund luxurious renovations to Zuma’s personal Nkandla estate. Concluding her investigation into the matter, the Public Protector found that public funds had been spent on the estate. She ordered the President to reimburse these costs. Yet, Zuma’s party commissioned an alternative report which exculpated him. When the parliamentary opposition tried to initiate action on the Public Protector’s report, the efforts were defeated by the African National Congress (ANC), the dominant party.[123]

The opposition took the case to the Constitutional Court, pointing to the failure to implement the Public Protector’s requirement for remedial action. In its Nkandla judgment, the Court stressed the principle of accountability and the Constitution’s goal ‘to make a decisive break from the unchecked abuse of State power.’[124] It concluded that the Public Protector’s findings might have binding effects: ‘[t]he Public Protector would arguably have no dignity and be ineffective if her directives could be ignored willy-nilly.’[125] As Roux reported, the judgment ‘turned public opinion decisively against Zuma.’[126] In fact, the combination of the Public Protector’s reports, the Constitutional Court’s Nkandla judgment and subsequent rulings, and the media’s efforts led to waning public support for Zuma and put further political processes in motion. In the 2016 municipal election, the ANC suffered substantial losses in major cities. This prompted further developments in the party, which ultimately led to the ousting of President Zuma and election of a new President.[127]

The Nkandla case was definitely not a low-cost one. The South African Constitutional Court is not ideally insulated from backlash. Most importantly, the ANC’s dominant position and the lack of a credible opposition party have represented obstacles to a robust political culture of respecting judicial independence.[128] Roux argued that it further suffered under Zuma who displayed populist tendencies both in his rhetoric and actions, including the undermining of constitutional institutions.[129] The institutional design pillar provides a mixed answer. Constitutional court judges are appointed by the President. The core actor, however, is the Judicial Service Commission (JSC). The JSC creates a list of nominees, which must be greater by three than the number of vacancies at the Court.[130] The JSC is a multi-stakeholder body composed of senior representatives of the judiciary, other legal professions and politicians.[131] In theory, this is quite a capture-proof design aimed at reducing executive control over appointments. Fowkes explained, however, that the dominant position of the ANC complicated this as it gives the ANC a considerable influence.[132] While there have in recent years been a number of controversies surrounding the appointment process and the ANC’s control over the JSC has been seen as a ‘constant threat’ to the Constitutional Court,[133] it seems that they have not resulted in an outright attack on the Court.[134] As Fowkes summarized, ‘While there are some more recent signs that the ANC has used this power to favour justices perceived to take a more restrained view of the judicial role, this is inherent in democratic political of appointments and has not translated into a threat to judicial independence.’[135]

The two pillars analysed so far – institutional design and political culture – thus present us with a non-captured court operating in a challenging environment. It was the Constitutional Court’s navigation in the broader political ecosystem that was crucial for the case. Although various scholars classify South Africa as a dominant party system due to the ANC’s ascendancy in the post-apartheid politics,[136] two main factors within the political pluralism pillar mattered for the Constitutional Court’s countering capacity in Nkandla: the pluralism of accountability institutions and the political uncertainty stemming from the existence of factions inside the ANC. First, the Constitutional Court managed, at least for that moment, to alter the deteriorating trajectory of South African democracy by buttressing an important accountability mechanism created by the 1996 Constitution. The Court maintained and strengthened the chance of holding the President accountable by supporting the Public Protector’s findings. The synergic effect of the Constitutional Court’s case law and the Public Protector’s report put things in motion thanks to a non-monolithic political context: pressure of the opposition and the public, as well as internal schisms in the ruling ANC party. In fact, Roux argued that the existence of factions within the ANC had been one of the crucial factors of the Constitutional Court’s authority.[137]

From the perspective of the dynamic dimension of judicial countering capacity, the Constitutional Court’s move in Nkandla was to some extent facilitated by its previous case law. While previously criticized for not having done enough to develop a doctrine to check the ANC’s dominance,[138] Brett argued that the Constitutional Court had interpreted the Constitution in a way that made virtually all exercise of public power justiciable.[139] Only later, however, does the Court seem to have started fully acknowledging the perils related to party dominance and has it aimed to stimulate greater pluralism. It has adjudicated on the quality of the ANC’s internal democratic processes and changed its approach to ‘constitution-building’ partnerships.[140] The judges started broadening the pool of partners responsible for the implementation of the constitutional project ‘in an apparent effort to contribute to the building of a more diffuse, pluralist democracy.’[141] Bolstering the authority of the Public Protector’s reports is a continuation of this trend. Yet, while these steps paved the way for the Constitutional Court’s decision, the Nkandla judgment also had unintended effects once a new Public Protector took the office.[142] The South African example thus portrays the countering of democratic decay as a long-term effort with possible twists and turns with an unclear endpoint. Simultaneously, however, it demonstrates the Court’s ability to contribute to countering democratic decay by interpreting the separation of powers principle in ways that empower actors capable of maintaining the rulers’ accountability.[143]

4.3 Court Capture: Poland

The judicial countering efforts in Colombia and South Africa are seen, more or less, as success stories. In contrast, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal’s (PCT) fate during the 2015–2016 crisis illustrates the perils of an institutional design lacking some important capture-proofing features, combined with a deteriorating populist political culture.[144] In 2015, the Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS), often labelled authoritarian populist,[145] won the parliamentary election and gained the absolute majority of seats in Sejm, the lower chamber. The party subsequently identified the Polish Constitutional Tribunal as a potential obstacle to implementing its agenda.[146] Sadurski argues that PiS aimed to transform the PCT in several stages. In the first stage, the government amended the Constitutional Tribunal Act in ways that paralyzed the court and effectively prevented it from reviewing new legislation.[147] Another step, however, was to shift the Tribunal’s ideological position towards government preferences by personnel changes. Sadurski concludes that PiS succeeded quite quickly, pointing to a number of cases where the Tribunal acted as the ‘governmental enabler’, rather than a check on the government.[148]

How could this happen to the 15-member Tribunal, once a posterchild of liberal constitutionalism in East-Central Europe, in less than a year? The judicial countering capacity frame provides an explanation based on the interaction of political and design features. First, the design of appointing constitutional judges in Poland has not been optimal for preventing unilateral politicized appointments. Judges of the Tribunal are chosen de facto by a single institution, the Sejm. Judges are elected by an absolute majority in the presence of at least half of the statutory number of MPs.[149] The Sejm is the confidence chamber of the Polish Parliament where the government is likely to enjoy a majority. Also, some of the vacancies occurring at the PCT are concentrated within a relatively short time period. This gives a lot of power to the majority governing at the time these vacancies occur. In addition, PiS took advantage of the previous majority’s problematic attempt to prevent personal takeover of the Tribunal. Shortly before the end of its term, the outgoing parliament had filled three vacancies on the Tribunal with new judges. Yet the MPs took a controversial step when they elected two more appointees in the place of judges whose mandate would run out two months later, i.e. after the end of the parliament’s term, to prevent the incoming parliament from choosing those judges. PiS used this problematic move. Although the election of the three judges was found legal,[150] the PiS-backed President refused to swear in all newly selected PCT judges. The government declared all five appointments invalid and installed its own nominees in the PCT.[151] As a result of these and other vacancies, by mid-2016 a majority of the PCT judges were the PiS government nominees. Several Polish scholars reported that these judges were rather deferential to the government.[152]

While the government’s strategy provoked public protests, violating the norms of political culture was not so costly for PiS, at least for that moment. The take-over of the PCT was followed by a complex and controversial judicial reform including major changes of the National Judicial Council, the Supreme Court, judicial leadership, and the ordinary courts.[153] The key was the populist rhetoric employed to justify the reform and an extensive media campaign against the courts. PiS reframed the discourse and presented judicial independence as a bulwark used by judges to deform the popular will. As Zoll and Wortham explained, PiS politicians labelled the Polish judiciary as being controlled by Communist-era corrupt judges and portrayed the judicial reforms as ‘the battle for justice and fairness in Poland.’[154] The government thus used the battle over the judicial reform as a way of further mobilizing its supporters.

These developments have had significant effects on the Tribunal’s judicial behaviour. Initially, the PCT’s caseload significantly decreased. Important actors, such as the Ombudsman, stopped activating the Tribunal due to concerns about the PCT’s legitimacy.[155] Then, the government itself initiated constitutional review on numerous occasions. Brzozowski argued that the post-2016 Tribunal ‘has abandoned the appearance of political neutrality and is now siding, almost openly, with the government,’ and has been complicit in the deterioration of democracy and the rule of law.[156] In this way, for instance, the PCT was blamed for paving the way for the government’s reform of the National Council of the Judiciary,[157] and for limiting the domestic effects of the CJEU’s and the ECtHR’s case law in areas related to the government’s judicial reform.[158]

The PCT’s story unfolded largely according to the predictions of the approaches ascribing courts an insignificant role in countering democratic decay. A previously successful court is paralyzed, which makes it largely unable to counter democratic decay, and subsequently captured. Sadurski considers the Polish case to be evidence of the irrelevance of constitutional design, others as a general proof of judicial impotence vis-à-vis democratic decay.[159] However, the judicial countering capacity frame provides a more nuanced view. It explains the PCT’s post-2015 developments as a case of a suboptimal institutional design facilitating swift capture, which largely prevented inter-institutional partnerships for countering democratic decay from coming into being. All of that was facilitated by a heavy populist framing, which facilitated a deterioration in political culture towards the courts and reduced costs of attacking the PCT.

5 Conclusions

The burgeoning field studying the judicial role in democratic decay is characteristic by the emergence of numerous diverging approaches. These cover a wide variety of views, ranging from those who see courts as major protectors of democracy to those who argue that judges are not capable of countering democratic decay effectively. While all of them offer valuable insights into the promises and pitfalls of judicial countering of democratic decay, the lack of a common conceptual and theoretical basis makes necessary cross-conversations difficult. This article, in contrast, has explained that the extent of courts’ capacity to counter democratic decay varies across countries and contexts, depending on how the court is situated and how it has used its agency. To capture these differences, the article has introduced the judicial countering capacity – a multifactor theory frame based on structural features of the political system (institutional design, political pluralism, and political culture) and on the agency of judicial and political actors. The point of the frame is to create a common conceptual and theoretical ground, which enables a creation of more detailed theories.

The idea of a varying judicial countering capacity has a number of implications. First, it makes a case for moving beyond the grand question whether courts are good or bad at protecting democracy. We should refocus scholarly attention from this grand question to less formidable but hopefully more productive enquiries. The judicial countering capacity frame invites an empirically oriented agenda focusing on micro-mechanisms of effective judicial countering across courts, issue areas and over time. Second, such analysis must move beyond the single-factor accounts towards explanations based on configurational thinking. Some of the case studies in Part 4 of this article, for instance, showed that it is rather unproductive to think about the significance of institutional design as a binary question. Examples from around the globe show that institutional design gains relative significance based on how it interacts with the remaining pillars of countering capacity: political pluralism and culture towards the judiciary. Third, the judicial countering capacity frame urges us to broaden our understanding of the political determinants of judicial authority. The direction is to go beyond the competitiveness of party systems and to include intra-party competition, and judicial partnerships with domestic and international non-partisan actors as important features. Each of these aspects, and particularly their combination, can have important implications for how the actors involved (especially litigants, civil society actors and judges) approach the countering of democratic decay and how they design their strategies.

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the Editor

- Nil Nisi Bene

- Research Articles

- When Populism Meets the Constitutional Dimension: A Formal Framework for Facilitating Comparative Constitutional Studies

- Emergency Labor Constitutionalism and Emergency Regulations

- Notes and Essays

- Constitutional Reform in a Fragile and Conflict-Affected Environment? Outlook on Constitutional Reform Processes in Ethiopia

- Countering Democratic Decay Judicially: Is Resistance Futile?

- Book Review

- Robert Böttner & Hermann-Josef Blanke: The Rule of Law Under Threat – Eroding Institutions and European Remedies

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the Editor

- Nil Nisi Bene

- Research Articles

- When Populism Meets the Constitutional Dimension: A Formal Framework for Facilitating Comparative Constitutional Studies

- Emergency Labor Constitutionalism and Emergency Regulations

- Notes and Essays

- Constitutional Reform in a Fragile and Conflict-Affected Environment? Outlook on Constitutional Reform Processes in Ethiopia

- Countering Democratic Decay Judicially: Is Resistance Futile?

- Book Review

- Robert Böttner & Hermann-Josef Blanke: The Rule of Law Under Threat – Eroding Institutions and European Remedies