Abstract

This paper provides a comprehensive overview of prior research on Gender Egalitarianism (GE) as a societal culture dimension, where it has been employed as either a correlate or moderator in the analysis of various phenomena, including entrepreneurship, leadership, human resource management, and sustainability. Building on the analysis of a large sample of eighty-two works, the main aim of this paper is to comprehensively reflect on GE as a cultural dimension based on a synthesis of insights from previous empirical studies.

1 Introduction

Gender is a relational concept, a social construct shaped by societal expectations, norms, and roles that vary across cultures and time, which began to develop primarily in the mid-20th century. Gender as a concept goes beyond the individual identities. Instead, it can be understood as one of the organizing principles defining social structures. It is a relational concept that defines the interactions and power dynamics between genders, creating a system of social relations that is produced and reproduced in everyday life, influencing personal identities, social practices, and institutions (Connell and Pearse 2015). As such, gender is one of the categories that need to be considered when analyzing, interpreting, and understanding the social world (Scott 1986).

Gender demonstrates itself in gender roles associated with a set of expectations and rules related to the idea of masculinity and femininity. These are often based on gender stereotypes assigning some set of qualities, activities, and ways of behaving to women (woman is passive, patient, caring, self-sacrificing, gentle, faithful) on one side and to men on the other (man is active, independent, proactive, uncompromising, decisive, strong) while also hierarchizing these qualities (male being superior to female) (see Kiczková 2011).

Gender roles and relationships between them are shaped by gender ideologies. Gender ideologies refer to a set of beliefs and perceptions regarding women, men, and alternative gender identities with the practical implications for both how individual identities are formed and how social groups and whole societies and economies are structured (Chatillon, Charles, and Bradley 2018). A variety of gender ideologies move from traditional gender ideologies characterized by clear distinction of gender roles at one end to egalitarian or feminist gender ideologies characterized by less distinctive gender roles at the other end. More recent approaches problematize this unidimensional and propose alternative frameworks that take the multidimensionality of gender ideologies into account (Grunow, Begall, and Buchler 2018; Knight and Brinton 2017; Van Damme and Pavlopoulos 2022).

However, it is not only values structuring gender relations. Practices, laws, and institutions also reflect and regulate the roles, expectations, and power relations between genders in a specific context forming the “gender regimes”. The concept of gender regimes (introduced by S. Walby) is also crucial in taking gender out of the context of the family to other domains, including economy, policy, civil society, and violence. Multiple components are considered in the definition of gender regimes (Walby 2020), crucial ones being division of labor, power relations, cultural norms, gendered identities (how individuals see themselves and others based on gender roles and expectations), and regulation and enforcement (laws, policies, or societal pressures that enforce gender roles or challenge gender inequalities).

One of the widely studied areas of management research is how gender impacts or interacts with various phenomena. Current management and organizational studies offer a vast body of research with some gender aspect across all areas of management, from human resources to financial management (for a comprehensive review of areas of research, see, e.g. Joshi et al. 2015).

The understanding of gender roles and norms is not confined to a single discipline; rather, it draws from various fields such as ethics, psychology, cultural studies, and organizational behavior. This multidisciplinary approach is crucial for comprehensively analyzing how these constructs influence managerial decision-making and leadership dynamics. For our article, it is essential to grasp these concepts within the context of cultural dimensions as they manifest in different aspects of managerial, organizational, and societal activities. Gender is also integrated as a dimension in the most influential cross-cultural management models/theories – Hofstede’s Cultural Dimension Theory and Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE). These models/theories were developed with the aim of facilitating an understanding of how the norms and expectations of different societies translate into organizational behavior and, in practical terms, navigate the design of organizational policies or preferred leadership styles.

Hofstede’s theory has been widely used in many studies in the field of both cross-cultural management and organizational and leadership studies. It has, however, also been subject to criticism, e.g. dimension of Masculinity/Femininity for oversimplifying gender roles by categorizing traits as either “masculine” or “feminine”, ignoring the complexity and diversity of gender expressions in different cultures and neglecting intersectionality. It is also criticized for being rooted in Western culture, portraying cultures as static, when in reality, they are dynamic and constantly evolving (see e. g. Moulettes 2007).

The operationalization of gender as a cultural dimension evolved further in the GLOBE program, a global research program investigating the relationships between societal culture, organizational culture, and leadership. National cultures are examined in terms of nine dimensions: performance orientation, uncertainty avoidance, human orientation, institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism, assertiveness, future orientation, power distance, and gender egalitarianism (see e.g., Dorfman et al. 2012; House et al. 2002; Javidan and Dastmalchian 2009). The former phase of this research project covered more than 60 societies, while the current GLOBE 2020 includes more than 140 countries with a focus on connecting cultural norms with attributes of effective leadership.

Dimension of Gender Egalitarianism (GE) is defined as the “degree to which an organization or a society minimizes gender role differences while promoting gender equality” (House et al. 2002, p. 5). Operationalization of this dimension referred to Hofstede’s Femininity/Masculinity dimension but was further developed to reflect some of the limitations of Hofstede’s approach. Mainly, the GLOBE program narrows the scope of the GE dimension, extracting some of the elements included in Hofstede Masculinity/Femininity into a separate dimension labeled Assertiveness, allowing for a clearer interpretation (Emrich, Denmark, and Den Hartog 2004).

As suggested by Emrich, Denmark, and Den Hartog (2004), the GE dimension encompasses both attitudinal and behavioral aspects. The attitudinal component pertains to core values, beliefs, and perspectives regarding gender stereotypes and gender role ideologies. The behavioral manifestations reflect observable actions in society related to GE, which include both gender discrimination and gender equality. Gender equality, as understood by the GLOBE model, refers to an extent to which women and men are represented equally in the labor force and position of power and their relative contribution to rearing children. The more society seeks to minimize differences in the roles allocated to men and women, the more equality we would expect. Gender discrimination, on the other hand, constitutes an act that prevents the members of one group from gaining an equal level of resources and recognition (Emrich, Denmark, and Den Hartog 2004).

In the GLOBE project, GE is measured using several items; requesting “As is” responses reflect current practices (behavioral manifestations), and “As should be” responses reflect the underlying values with regard to an ideal society in this dimension. Societies that score higher on GE are expected to have a greater representation of women in leadership roles, assign them a higher social status, and involve them more significantly in community decision-making processes. They should reach higher participation of women in the labor force with lower levels of occupational sex segregation. They should also demonstrate higher literacy rates for women and similar levels of education for both men and women (Emrich, Denmark, and Den Hartog 2004).

The main goal of this paper is a comprehensive reflection on GE as a cultural dimension, based on a synthesis of insights from previous empirical studies. Multiple empirical studies use GE as a correlate or a moderator variable in analyzing various phenomena. Based on an in-depth review of the sample of these studies, this paper explores how GE connects with other individual, organizational, and societal phenomena, and offers some recommendations for advancing the understanding of GE as a cultural characteristic. Awareness concerning the role of GE can assist different levels of stakeholders in setting policies related to corporate governance, approaches to sustainable development, and overall societal advancement.

2 Research Methodology

To gain a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the effects of the cultural dimension of Gender Egalitarianism (GE), the search aimed to identify all relevant scientific articles addressing GE. The literature search was carried out in the two most renowned databases, Scopus and Web of Science, as they curate content only from reputable journals with rigorous review processes aiming to ensure high academic standards of the published works. Considering the substantial interdisciplinarity of the GE topic, despite some limitations of the given databases (Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016), a key advantage is their extensive coverage across a wide range of disciplines.

The search was carried out in April 2024. In its initial phase, the keywords “gender egalitar*” and “cultur*” combined with method* PRE/4000 “GLOBE” (alt. “global leadership and organizational behavior effectiveness”) were used in all search fields in both databases. This yielded 175 documents in Scopus and 218 papers in Web of Science. Afterward, the search was limited to papers in English, which led to 136 items in Scopus and 199 items in Web of Science. The manual screening based on titles, abstracts, and keywords sections ended with 58/78 papers, respectively. Two additional papers were included based on the references in the screened papers. In this eligibility screening process, two in/exclusion criteria were applied: (1) our focus was on GE as a societal culture dimension, and, therefore, papers dealing with GE in a different way (e.g. as an organizational characteristic) were excluded; and (2) we focused only on empirical studies that explored correlations involving GE or examined GE as a moderating variable between other factors. Thus, theoretical studies or papers that provided descriptive analyses of GE within a single country were excluded from the analysis.

In the next step, the two sets of papers from Scopus and Web of Science were merged in the R program to eliminate duplicities. This resulted in acquiring a set of 105 documents. The following cleaning round was based on a detailed screening of the methodological sections of the papers. Given that the GE as a cultural dimension has been specifically conceptualized within the GLOBE project, the search concentrated on publications explicitly stating in their methodological sections that they utilized national culture scores as reported by this project. Additionally, we included papers that replicated the GLOBE methodology and generated new data on the level of GE in culture using the same measurement instrument. Research projects employing alternative methodologies, such as the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, World Values Survey, or Hofstede’s framework, were excluded due to differences in measurement approaches and the conceptualization of gender egalitarianism.

Following this manual review, the final sample of studies eligible for the subsequent qualitative synthesis was n = 82. This sample of papers was analyzed via Bibliometrics-Biblioshiny (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017) in the R program.

2.1 Brief Overview of the Analyzed Sample of Papers

The analyzed corpus’s publication period was 2005–2024, with an annual growth of nearly 9 %. The sample included 82 works by 285 authors published in 60 journals, with seven single-authored papers. The average number of authors per paper was four, and 29 % of papers were written under international collaboration. The average number of citations per paper was close to 59.

With more than 1,000 citations, the paper by Bae et al. (2014) was the most cited study in the corpus of analyzed works. It dealt with the connection between entrepreneurship education and the intentions of individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activities, with GE as a moderator of this relationship. The second most cited paper (436 citations) by Baughn, Chua, and Neupert (2006) examined how specific norms supporting women’s entrepreneurship influence the gender gap in entrepreneurial participation across countries, considering the interplay between general entrepreneurial support, GE, and economic development. The third most frequently cited study (with 409 citations) by Haar et al. (2014) investigated GE as a moderator of work-life balance, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, anxiety, and depression across the seven cultures.

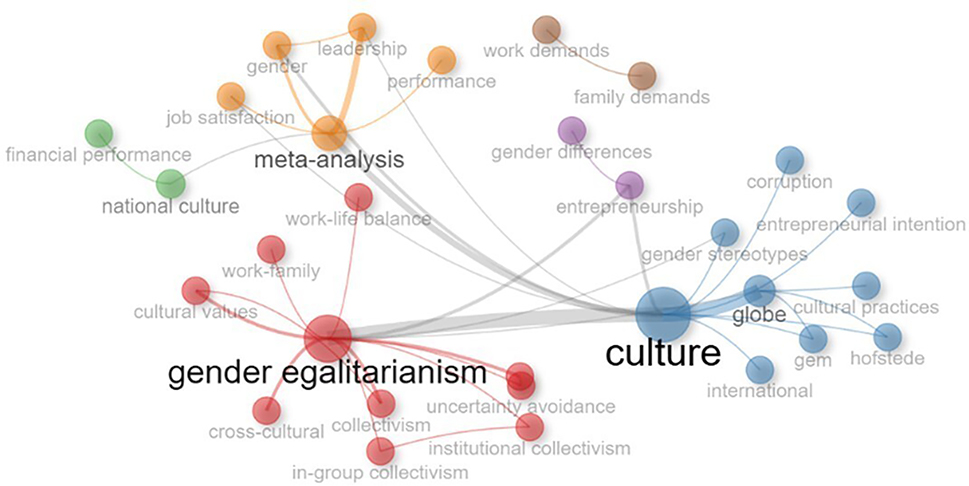

Figure 1 illustrates the co-occurrence of the research topics within the GE discourse. Each node represents a research topic, and the connections between nodes represent the relationship between these topics in the GE literature. The size of the nodes indicates the frequency of the topic, while the color of the clusters highlights different thematic groupings.

Co-occurrence network of research topics related to gender egalitarianism.

The brown cluster, which includes “family demands” and “work demands”, seems more isolated, with fewer connections to other themes. This might suggest that research in this area is more specialized or less integrated with other themes in GE research. The main “meta-analysis” theme in the orange cluster links broader gender-related research, such as performance, leadership, and job satisfaction, indicating the synthesis of findings across studies. The violet highlights the importance of gender differences in entrepreneurship. Similarly, the green cluster connects gender research with national culture and financial performance. The orange and green clusters seem to have fewer connections to other clusters, suggesting that these research topics may be more self-contained or less frequently associated with other areas. On the other hand, the red and blue clusters are significant groupings with many interconnected nodes representing major research themes. They share several connections between them, indicating that topics within these clusters often co-occur.

Central to the research, gender egalitarianism is closely connected with concepts like work-family balance and cross-cultural aspects of institutional collectivism, in-group collectivism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance that represent cultural dimensions frequently studied in connection with GE. The theme of culture in the blue cluster serves as a bridge linking international perspectives (e.g., GEM study, GLOBE study, Hofstede’s dimensions) with gender stereotypes, entrepreneurial intentions, and corruption.

This brief overview in Figure 1 highlights the most relevant research topics within the respective discourse, but due to the broad level of generalization, it does not cover all topics comprehensively. The next section of this paper will present in great detail the results of a qualitative analysis of 82 studies on GE as either a correlate or moderator in the relationship between variables of interest.

3 Results

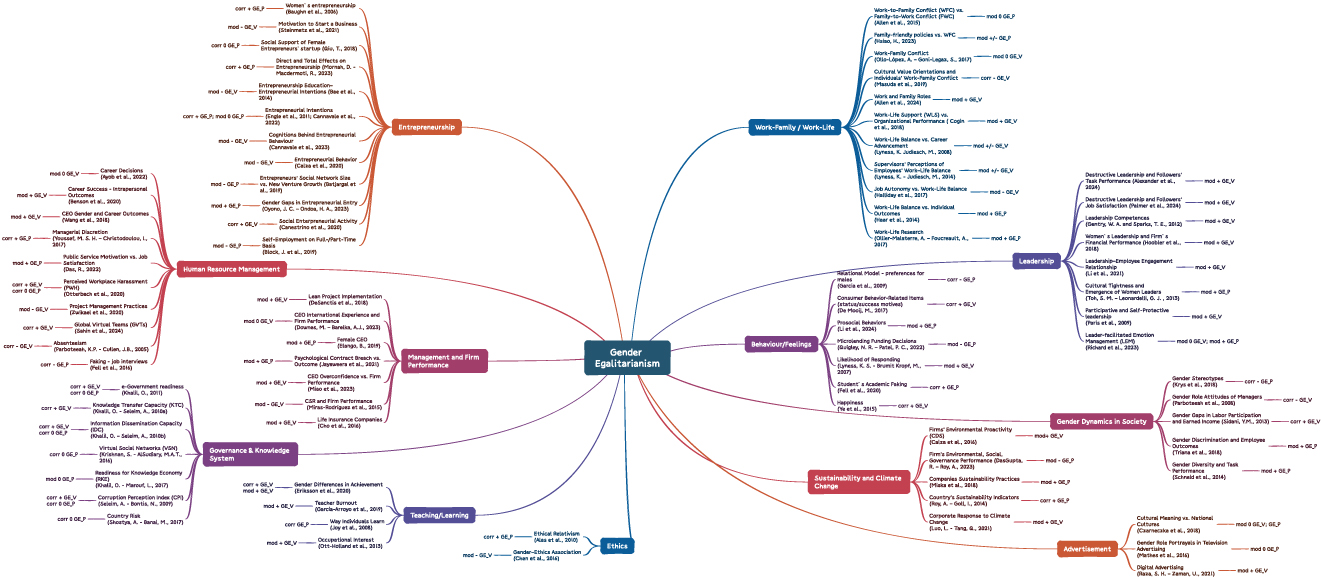

A comprehensive review of the literature on GE was carried out, followed by an in-depth analysis of the findings. Figure 2 presents a summary of GE’s role, highlighting its function as both a correlate and a moderator. To provide a more accessible overview of the extensive findings from multiple studies, the results have been organized into subgroups based on the subject matter of the reviewed papers.

Summative overview of gender egalitarianism effects. Note: Corr – correlation, mod – moderation, GE_V – value, GE_P – practice, +/− positive/negative relationship, 0 – not significant relationship.

The subsequent sections offer a thorough description of the findings within each domain. Within the presented studies, the dimension of GE was mostly only one of several investigated indicators, but we pay special attention only to the role of GE in the observed relationships. The following text includes all outcomes concerning the GE where the connection with other variables was either confirmed, partially supported, or no significant results were established.

3.1 Entrepreneurship

The most popular research area concerning the role of GE seems to be entrepreneurship and its different aspects. Studies are oriented toward drivers of social entrepreneurship, attitudes of women toward doing business, or entrepreneurial intentions. Few studies map the role of cultural dimensions on entrepreneurial behavior (see Figure 2).

In their study, Baughn, Chua, and Neupert (2006) investigated how a country’s level of gender equality influences the ratio of women to men involved in entrepreneurship. The findings indicate that countries with higher GE (practice) tend to have more women participating in entrepreneurship. Steinmetz, Isidor, and Bauer (2021) explored how the societal context moderates the motivation to start a business. Contrary to expectations, they found that in countries with high gender egalitarianism (value), women had a more negative attitude toward starting a business compared to men and felt less external support or expectation to do so, in contrast to women in less egalitarian countries. Another study by Qiu (2018) examined how cultural practices influence social support for female entrepreneurs’ startups across various countries, finding that the impact of gender egalitarianism (practice) on the variation in social support for female entrepreneurs was negligible. In their research Mornah and Macdermott (2022) model the Direct (how societal values and norms facilitate and encourage entrepreneurship) and Total (direct plus indirect) Effects of culture on entrepreneurship, considering potential endogeneity. They found that GE (practice) has robust positive Total Effects on national entrepreneurship. The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions was studied by Bae et al. (2014), and cultural values served as moderators. They found in low GE countries the mentioned relationship becomes more positively associated.

Other impacts on entrepreneurial intent, such as the social influence of family, friends, and role models, were studied by Engle, Schlaegel, and Delanoe (2011), who found GE (practice) to be significantly influencing the entrepreneurial intentions of women. In the study of Cannavale et al. (2022), GE was used as a moderator in the relationship between entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial activities. GE (practice) did not show any moderating role in such a relationship, while at both very high and very low levels of GE, the enactment of entrepreneurial intentions into actual activities may be inhibited. In the later study, Cannavale et al. (2023) investigated the effects of GE on the cognitions behind entrepreneurial behavior. They found a negative moderation effect of GE (value), indicating that the positive attitude toward entrepreneurship weakens in societies with high GE values. Research by Calza, Cannavale, and Zohoorian Nadali (2020) found that GE (value) negatively impacts the formation of the reasoning behind entrepreneurial behavior. In countries with high GE, the motivation for entrepreneurial intention is low, while the ‘reason against’, such as fear of failure, is high. Equal opportunities in those countries probably reduce the importance of prestige and success. A study by Batjargal et al. (2019) analyzed why female and male entrepreneurs experience different growth returns from their social networks. In cultures with low GE (practice), male entrepreneurs benefited more from their larger social networks than female entrepreneurs did.

The role of GE on gender gaps in entrepreneurial entry in developing countries was analyzed by Oyono and Ondoa (2023) who showed GE (practice) positively moderated this gap, promoting women’s entry into both total and opportunity-based entrepreneurship. Similarly, Canestrino et al. (2020) investigated the cultural drivers of social entrepreneurial activity (SEA) and found that GE (value) positively correlates with narrowly defined operating SEA. A study by Block, Landgraf, and Semrau (2019) found a negative relationship between GE (practice) and full-time self-employment, as higher GE societies typically establish policies (such as parental leave, and child care services) that enhance opportunities for parents to engage in the labor market.

3.2 Work-Family/Work-Life

A lot of studies have followed specific aspects within the area of work-family and work-life balance (see Figure 2), several of them focusing attention on the work-to-family (and vice-versa) conflict (WFC/FWC), where the role of GE seems not to be significant. Besides, GE plays a role in work-life balance versus career advancement, or outcomes.

For instance, Allen et al. (2015) compared cross-national differences in work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict and found no significant difference in reporting WFC and FWC between less and more GE (practice) countries. The moderating role of GE (practice) was also investigated by Hsiao (2023), who demonstrated that family-friendly policies, like parental leave, have a stronger impact on reducing work-family conflict for men than for women. In high GE cultures (practice), fathers experienced greater WFC, as societal expectations for them to engage more in family life conflicted with their work demands. In contrast, GE negatively moderated the relationship between having a full-time working spouse and WFC (in high GE cultures, mothers experienced less WFC because their spouses were more likely to share family responsibilities). Yet, the findings of Ollo-López and Goni-Legaz (2017) demonstrated that GE (value) as a moderator had no significant effect on women’s and men’s WFC, and, as a variable, did not explain national differences in WFC. Contrary, Masuda et al. (2019) revealed that GE (value) is negatively related to individuals’ WFC.

Allen et al. (2024), in their later study, examine the relationships between GE (value), gender, and boundary management preferences. Individuals from more GE societies expressed a lower preference for separating family and work; however, GE was not directly linked to preferences to segment work-from-family. The study of Cogin, Sanders, and Williamson (2018) analyzed the relationship between work-life support (WLS) practices in companies benefits to organizational performance considering both the internal and external environments of the organization. The percentage of top management team members with children and GE (value) of the country, strengthened the relationship between WLS practices and customer satisfaction. Findings of Lyness and Judiesch (2008) indicated that GE (value) plays a significant moderating role in the relationship between work-life balance and career advancement potential. In low GE cultures, managers with higher work-life balance are perceived as having greater career advancement potential compared to more work-focused managers. However, in high GE cultures, this relationship is stronger for women (benefit more from work–life balance), while it is nonsignificant for men (benefit more in low GE cultures). In their later study, Lyness and Judiesch (2014) found that supervisors’ perceptions of employees’ work–life balance varied based on the gender of the ratee and the country context. In countries with low GE, supervisors rated women’s work-life balance lower than that of men; however, similar to men in highly egalitarian countries.

Halliday et al. (2018) revealed the moderating role of GE (value) in the relationship between perceived job autonomy and work-life balance, engagement, and turnover intentions. Stronger positive effect was found in low GE cultures where women face greater gender-based challenges, autonomy is a critical resource, helping women overcome barriers and achieve better job satisfaction and performance. Moderating effect of GE (practice) on the relationship between work–life balance (WLB) and several individual outcomes was investigated by Haar et al. (2014) implying high levels of WLB were more positively associated with job and life satisfaction and more negatively associated with anxiety for individuals in GE cultures. Last but not least, Ollier-Malaterre and Foucreault (2017) offered insights for cross-national work-life research, GE (practice) being one of the moderators. While GE did not predict WFC for either men or women, the study found that gender differences in work-family enrichment were reduced in higher GE countries.

3.3 Human Resource Management

Ten studies examined different aspects of HRM (Figure 2, the highly populated category of HRM is located on the left side under Entrepreneurship), where in five of them, GE served as a correlate and in the rest as a moderator. Three studies mapped the impact of GE on career (decisions, success), and the rest were focused on other specific problems.

Ayob, Hamid, and Sidek (2022) explored the moderating effect of cultural dimensions between individual values – as selfdirection, power, and benevolence – and career decisions (self-employment or paid-employment). They found that individual values had a stronger impact on career choice than cultural context, with GE being statistically insignificant in predicting individual career decisions. The relationship between national culture and the ways how individuals define career success was examined by Benson et al. (2020). GE (value) was more likely to support career success in terms of intrapersonal outcomes. Wang et al. (2018) used GE (value) as a moderator within the relationship between CEO gender and career outcomes. GE influences societal expectations and norms regarding gender roles in leadership, shaping career success and organizational performance for male and female CEOs differently depending on the country’s cultural framework. The findings of Haj Youssef and Christodoulou (2017) showed GE positively correlated with the level of discretion executives had in decision-making. A study by Das (2022) revealed that public service motivation (PSM) may predict job satisfaction (JS) among employees in government and nonprofit organizations across diverse contexts. GE (practice) had a notably stronger moderating effect on this correlation in Asia compared to the West.

An interesting study on workplace harassment (WH) by Otterbach, Alfonso, and Zhang (2021) found that although the perceived WH gender gap was positively correlated with the GE values, there was no large or significant correlation with the GE practices. Whereas enhanced GE values increase women’s perceptions of workplace harassment, concrete practices tended to reduce them. Results of Zwikael et al. (2022) revealed that GE (value) showed a negative moderating effect on adopting project management practices. More specifically, in countries with higher GE, there was a tendency to see less adoption of these practices. The effectiveness of global virtual teams (GVTs) within different cultural contexts was explored by Şahin et al. (2024). The results showed that cultural values interact to drive high levels of team performance rather than operating in isolation. Different configurations of cultural values can lead to similar successful outcomes, with the presence of GE and the absence of power distance being the most crucial factors for achieving these results. Parboteeah, Addae, and Cullen (2005) examined absenteeism from a cross-cultural perspective, proving that GE (value) had a negative relationship with absenteeism. The question of whether applicants with different cultural backgrounds are equally prone to fake in job interviews was answered in the Fell, König, and Kammerhoff (2016) study. At a national level, attitudes toward faking were linked to four cultural dimensions, one of them being GE (practice). Countries with high GE tended to view faking in job interviews more negatively and vice-versa.

3.4 Leadership

The examined studies show that GE is a significant moderator in the relationship between leadership style and employee performance, outcomes, or satisfaction. We found eight studies concerning GE’s role in that area.

In the study of Alexander et al. (2024), GE (value) moderated the relationship between destructive leadership and the task performance of followers. In higher GE cultures, followers may be less affected by destructive leadership, as these cultures tend to promote equal and supportive relationships in the workplace, reducing the impact of harmful leadership behaviors. Palmer et al. (2024) found that GE (value) also moderated the adverse effects of destructive leadership on followers’ job satisfaction. In high GE cultures, the negative impact of destructive leadership on job satisfaction was weaker. Findings of Gentry and Sparks (2012) revealed that GE (value) moderated the importance managers place on different leadership competencies across cultures. In high GE cultures, leadership competencies reflected more collaborative and inclusive traits are valued more, while in low GE cultures, traditional leadership competencies tended to be prioritized. Hoobler et al. (2018) built their research on defining the relationship between women’s representation in leadership roles and financial performance of organizations. They found that the presence of a female CEO was more likely to have a positive impact on firms’ financial performance in more GE cultures (value). Findings of Li et al. (2021) indicated that GE (value) moderates the relationship between leadership and employee engagement across different countries. In high GE cultures, leadership behaviors that emphasized equality, inclusiveness, and fairness were more strongly associated with higher employee engagement.

Toh and Leonardelli (2012) showed that GE (practice) moderated the relationship between cultural tightness (how strict or flexible social norms are) and the emergence of women leaders. In high GE cultures, women are more likely to emerge as leaders, as societal norms favor equal opportunities for both genders. Paris et al. (2009) analyzed if preferred leadership prototypes held by female leaders differ from those held by male leaders and what moderates these differences. In high GE (value) societies, female managers emphasized the Participative leader prototype more than their male counterparts. GE also moderated the relationship between gender and Self-Protective leadership but not Autonomous leadership. Leader-facilitated emotion management (LEM), which refers to behaviors that assist followers in regulating negative emotions, is a crucial element of various leadership styles. However, expectations for LEM can differ based on the leader’s gender and cultural background. Richard, Walsh, and Young (2023) examined GE (value; practice) in moderating gender-based and LEM-related differences in leader effectiveness ratings. Results showed that GE as a value was not a significant moderator, contrary to GE as a practice. In high GE countries, a stronger positive correlation was observed between LEM behavior and leader effectiveness ratings, with male leaders facing a greater ‘penalty’ for low LEM behavior compared to their female counterparts. Conversely, in low GE practice countries, the ‘boost’ in effectiveness ratings linked to high LEM behavior was more pronounced for female leaders than for male leaders.

3.5 Behavior/Feelings

Seven studies mapped the impact of GE on behavior (e.g., employment-related decisions, students’ academic faking) or feelings (e.g., happiness) (see Figure 2, on the right in the middle).

García, Posthuma, and Roehling (2009) expanded the relational model theory incorporating social dominance theory to investigate the impact of national culture on preferences for males and nationals in employment decisions. Their findings indicated that GE (practice) was linked to a reduced likelihood of preferring males in hiring, while masculinity was correlated with an increased preference for nationals. The study of De Mooij (2017) compared three prominent dimensional models (Hofstede, Schwartz, GLOBE) by analyzing consumer behavior-related items. Just several dimensions explained differences in consumer behavior. Moreover, dimensions sharing the same label did not necessarily explain similar differences; however, masculinity/femininity, GE, and assertiveness seemed to be closest in their explanatory power. The study concluded that when examining specific areas of human behavior, researchers could select from various models, with GE (value) effectively elucidating items associated with status and success motives. In a later study, Li et al. (2024) revealed the impacts on prosocial behaviors. In countries with low GE (practice), a gender gap in pro-environmental behaviors was more pronounced, with women exhibiting less prosocial behavior compared to men. Additionally, women in similar institutional contexts displayed significantly higher levels of anticorruption behavior than their male counterparts; however, this discrepancy diminished in countries with high GE. Quigley and Patel (2022) investigated how the gender of the borrower and the GE (practice) of their societal culture interacted to affect the amount of funding received in microlending. They found that while women borrowers generally secured less funding than men, this trend was moderated by the level of GE in the borrowers’ home culture. Specifically, in cultures with low GE, women borrowers obtained more funding than their male counterparts.

Lyness and Brumit Kropf (2007) examined how both individual and country characteristics influenced the likelihood of response. They discovered that although women were more likely to respond than men, the gender gap narrowed in countries with higher GE. Findings of Fell and König (2020) revealed that students’ academic faking was positively related to GE (practice). The similarity in academic faking between female and male students was slightly greater in cultures with higher GE compared to those with lower GE. Finally, Ye, Ng, and Lian (2015) revealed that GE (value) significantly correlated with subjective well-being, influencing the level of happiness across different societies.

3.6 Management and Firm Performance

Seven studies analyzing GE’s moderating role in the relationship between firm performance and other aspects of management, such as CEO experience, were identified under this domain (see Figure 2 on the left in the middle).

DeSanctis et al. (2018) studied the interplay of various factors related to national culture and company characteristics on the outcome of lean project implementation, finding that GE (value) significantly influenced lean management outcomes, thereby fostering a lean culture. Downes and Barelka (2023) investigated how the international experience of chief executive officers (CEOs) relates to firm performance. Yet, differences in performance between going to or from higher scoring countries on GE (value) were not significantly different. Elango (2019) observed that country wealth, GE (practice), and humane orientation increased the likelihood that a female CEO would lead a firm. Miao et al. (2023) revealed that the CEO overconfidence – firm performance relationship was stronger in high GE (value) cultures. A study by Jayaweera et al. (2021) found that GE practices moderated the individual-level relationships between psychological contract breach and key work outcomes, specifically job performance and turnover. Del Mar Miras‐Rodríguez, Carrasco‐Gallego, and Escobar‐Pérez (2015) aimed to analyze the moderator role of national culture on the CSR and firm performance relationship. Countries with high GE (value) showed a negative relationship between them. Cho, Cho, and Xue (2016) tested how national culture affects life insurance companies. Higher levels of GE (value) strengthened the positive effects of cultural alignment between joint venture partners, leading to better company performance.

3.7 Gender Dynamics in Society

GE, as a cultural dimension, indicates differences in gender roles. Cross-cultural research indicates that explicit gender stereotypes are less common in societies that prioritize GE. Five studies were identified in this specific area.

Krys et al. (2018) analyzed if self-reported gender stereotypes differed from implicit attitudes towards each gender. Societal GE (practice) reduced the “women-are-wonderful” effect when it was measured more implicitly and documented that the social perception of men benefits more from GE than women’s. The results indicate that the disparities in the social perception of men and women are reduced in more GE societies. Parboteeah, Hoegl, and Cullen (2008) explored how certain aspects of various countries relate to the traditional gender role attitudes of managers, utilizing the country’s institutional profile. As expected, GE (value) negatively affected managers’ traditional gender role attitudes. Research by Sidani (2013) addresses the relationship between differences in labor force participation and salary earnings. GE (value) was associated with higher levels of female labor participation relative to male participation and ratio of women’s earnings to men’s earnings. In egalitarian societies women’s labor force participation is expected to be more encouraged. The moderating role of GE (practice) in the relationship between perceived gender discrimination and various employee outcomes (job attitudes, physical and psychological health outcomes, work-related outcomes) was analyzed by Triana et al. (2019). Authors inferred that in higher GE countries, people would feel more entitled to fair treatment and have stronger adverse reactions to gender discrimination. Schneid et al. (2015) found a negative direct relationship between gender diversity and contextual performance, with GE moderating how gender diversity impacts task performance. In particular, in cultures with low GE, gender diversity seems more detrimental to teams’ task performance.

3.8 Governance and Knowledge System

This domain includes seven studies concerning the role of GE in the readiness of the economy to develop e-government, knowledge economy, transfer capacity or governance of corruption, and country risk. As the results indicate, GE does not seem to play a significant role in this particular area (Figure 2, on the left).

Khalil (2011) showed that GE values were critical determinants of e-Government readiness, but there was no significant relation with GE practices. A study by Khalil and Selim (2010a) declared that national culture may elucidate the differences in knowledge transfer capacities (KTC) observed among countries. It showed that KTC correlated positively with GE (value). In another study, Khalil and Seleim (2010b) explored the impact of national culture practices on information dissemination capacity (IDC). A society with low GE values had low IDC and vice versa. On the other hand, IDC-Index did not correlate with GE practices. The impact of cultural practices on the spread of virtual social networks within the country was investigated by Krishnan and AlSudiary (2016). GE was not significantly associated with virtual social network diffusion in a country. A study by Khalil and Marouf (2017) assumed that nations differ considerably in their readiness for knowledge economy (RKE), but GE (practice) was found insignificant in this respect. The study by Seleim and Bontis (2009) aimed to investigate the relationship between cultural dimensions of values and practices in relation to the Corruption Perception Index (CPI). There was a positive significant relationship between GE (value) and CPI score (more GE country, less corruption). However, the finding did not confirm any relationship between GE (practice) and corruption. Shostya and Banai (2017) aimed to investigate how cultural and institutional factors influence country risk. No statistically significant relationship with GE (practice) was established.

3.9 Sustainability and Climate Change

The crucial topic of recent times is sustainability, which is entering almost all areas of our lives. It is not surprising that it has also attracted the attention of researchers dealing with cultural dimensions as moderators of the differences in cultures’ impact on climate change and attainment of sustainable development, GE not being an exception (for a better overview of studies see also Figure 2).

Calza, Cannavale, and Tutore (2016) tried to evaluate how national culture impacts the environmental proactivity of firms, specifically through the Carbon Disclosure Score (CDS). GE (value) had a positive impact on firms’ environmental proactivity. Research by DasGupta and Roy (2023) investigated the extent to which national culture dimensions may influence an international firm’s environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance, potentially enhancing or detracting from its financial performance. High GE (practice) would negatively moderate the firm’s financial and ESG performance, meaning that ESG performance would weaken the firm’s financial performance. The influence of cultural, institutional, and natural ecosystems on how corporations react to climate change was investigated by Luo and Tang (2022). They found that GE (value) strengthened corporate performance. Miska, Szőcs, and Schiffinger (2018) examined how culture influences companies’ practices in economic, social, and environmental sustainability, finding that GE (practice) positively predicted corporate sustainability practices. How national culture shapes various dimensions of a country’s sustainability indicators, such as environmental performance, human development, and the prevention of corruption, was examined by Roy and Goll (2014). GE (practice) positively influenced environmental performance, even after accounting for a nation’s wealth, such as GDP. GE also interacted with economic freedom in shaping both environmental performance and human development, similarly to the effects of GDP and the economic growth rate.

3.10 Teaching/Learning

There is no doubt that GE plays a moderating role in factors influencing teaching and learning. In our set, we identified four studies on this topic (Figure 2, located on the bottom left).

Eriksson, Björnstjerna, and Vartanova (2020) found that gender differences in achievement exhibited variation between domains and countries. Thus, higher levels of GE values were associated with reduced gender disparities in academic performance. According to García-Arroyo, Osca Segovia, and Peiró (2019), more GE tended to decrease teacher burnout, showing significant variation across countries; this indicates that interventions aimed at alleviating this issue should also account for cultural contexts to enhance their effectiveness. Joy and Kolb (2009) examined culture’s role in how individuals learn. The individuals tended to have a more abstract (opposite to reflective) learning style in countries with high GE (practice). A study by Ott-Holland et al. (2013) demonstrated that GE moderated gender differences in occupational interests. In higher GE (value) cultures, vocational interests tended to be less influenced by traditional gender roles, leading to more flexibility in career choices for both men and women.

3.11 Ethics/Business Ethics

Although the ethical aspect could be a side-line in several already mentioned studies, we categorized two studies as dealing directly with ethics (see Figure 2 at the bottom). More specifically, Alas, Junhong, and Jorge (2010) indicated differences in the impact of national cultures on ethical relativism between countries. They found that people in higher GE societies put more emphasis on situational factors when deciding what is right and wrong. Chen et al. (2016) examined the moderating influence of cultural values on the relationship between gender and ethics. Their findings indicated that male managers were more inclined than female managers to rationalize unethical business practices, such as bribery and tax evasion. Furthermore, the gender disparity in ethical perceptions was amplified in the presence of certain cultural dimensions (values), including GE.

3.12 Advertising

The extensive scope of research on the impact of GE is further evidenced by three studies focused on advertising. Czarnecka, Brennan, and Keles (2018) explored how advertisements’ cultural meanings align with target audiences’ national cultures. Their findings revealed both similarities and differences in advertising appeals, but GE was not a significant factor in shaping these cultural reflections. In the study by Raza and Zaman (2021), GE (value) acted as a positive moderator in a mediated model where attitudes toward digital advertising mediated the association between perceptions of digital advertising (PDA) and online purchase intention (OPI) for fashion brands. The findings showed that while attitudes mediated the PDA-OPI relationship, the strength of this mediation was significantly greater in higher GE contexts. Matthes, Prieler, and Adam (2016) noted a lack of comparative studies on gender role portrayals in TV advertising. Their model showed that gender stereotypes were unrelated to GE (practice), suggesting that a country’s level of GE does not influence gender stereotyping in TV ads.

4 Discussion

The GLOBE framework represents one of several ways to approach the interconnection of gender and management. Building on the insights presented, we propose that the GE cultural dimension, as a tool employed in international management studies, warrants a thoughtful and critical evaluation. This would allow a deeper understanding of its applicability, strengths, and limitations in diverse contexts. In this discussion, we aim to highlight the variety of thematic domains in which the GE societal culture dimension is researched with special attention to the practices versus values levels of analysis, to offer a multidisciplinary perspective on the empirically derived effects of GE, and to explore the associated practical implications.

4.1 An Integrative Overview of GE-Related Thematic Domains and Levels of Analysis

From the viewpoint of GE yielding different impacts in the twelve identified domains, the presented review of empirical studies suggests that GE frequently appears as a correlate or a moderator in relationships related to human resource management practices, leadership, and entrepreneurial motivation. Inspecting the GE-related results from the perspective of each identified domain (see Figure 2), Meaningful are many domains, particularly Gender Dynamics in Society, Sustainability and Climate Change, or Teaching/Learning, producing relatively unambiguous conclusions with respect to GE. On the other hand, the Governance and Knowledge Systems, and the Advertising areas of research seem to somewhat lack connection (either positive or negative) with the level of GE in societies. For example, GE was found to be an insignificant factor regarding cultural meanings in advertisements (Czarnecka, Brennan, and Keles (2018) and gender role portrayals in TV (Matthes, Prieler, and Adam 2016). It is likely that these phenomena are influenced by factors beyond the GE orientation in society. Alternatively, it is also possible that these phenomena are shaped by a broader set of cultural variables, suggesting that focusing on a single factor (in this case, GE) may not yield meaningful or conclusive results.

Our synthesis of studies reveals an intriguing pattern within the Governance and Knowledge Systems domain: GE values consistently show significant relationships with key outcomes like e-government readiness (Khalil 2011), knowledge transfer capacity (Khalil and Seleim 2010a), and corruption perception (Seleim and Bontis 2017), while GE practices do not (see e.g. information dissemination capacity (Khalil and Seleim 2010b), or virtual social network diffusion (Krishnan and AlSudiary 2016)). This discrepancy may stem from the deeper cultural layer at which values operate, influencing long-term aspirations and societal ideals, as opposed to practices, which reflect immediate and often more constrained realities. Values likely shape perceptions and strategic planning in governance, aligning more closely with aspirational systems like knowledge economies or anti-corruption frameworks. Practices, conversely, may face structural barriers and entrenched societal norms, limiting their immediate impact on these systems. This distinction aligns with findings from the GLOBE study, which emphasizes that values often drive broader societal effectiveness and alignment with idealized cultural goals, whereas practices may lag due to institutional inertia or conflicting local contexts (House et al. 2004).

Hence, GE values represent societal ideals about the extent to which men and women should have equal opportunities and treatment. On the other hand, GE practices reflect the actual observed equality or inequality in behaviors, roles, and access to resources between genders in different societies. It seems that countries with higher GE practices tend to demonstrate greater structural and organizational inclusivity, while higher GE values may reflect societal aspirations to improve gender parity without necessarily implementing it fully. Interestingly, GE is the only cultural dimension in the GLOBE program where practices and values were significantly positively correlated. This means that the higher the perceived level of GE practices in a society, the more desirable GE is within that society (Hanges 2004). In other cultural dimensions, the relationship between practices and values tends to be negatively correlated, suggesting that these cultural characteristics may be perceived as inherently tensed, for instance, the more a society is power-distant, the less it considers this trait desirable, and vice versa. This, however, does not apply to the GE dimension.

The challenge posed by the positive association between GE practices and values is that when examining GE as a correlate or moderator, outcomes for certain “desirable” organizational or societal variables should align with the same pattern. However, as we present in the Results section (see also Figure 2), the mentioned is not the case for several variables under investigation. For instance, in the domain of entrepreneurship, it was shown that countries with higher GE (practices) tend to have more women participating in entrepreneurship (Baughn, Chua, and Neupert 2006). In contrast, GE values, as in Calza, Cannavale, and Zohoorian Nadali (2020) and Cannavale et al. (2023), often highlight more nuanced or even negative moderations, where societies with strong aspirations toward gender equality may paradoxically reduce entrepreneurial motivation, possibly due to shifts in societal expectations or reduced external pressures. In a similar vein, Steinmetz, Isidor, and Bauer (2021) found that women in societies with higher desired levels of GE (values) had a more negative attitude toward starting a business than men. Moreover, it was also found that GE (practices) did not explain the variation of social support of female entrepreneurs in diverse countries (Qiu 2018). To formulate a broader generalization, it appears that GE practices positively impact tangible outcomes, such as participation rates or entrepreneurial activities, as they reflect real, structural inclusivity. On the other hand, GE values often serve as moderators or indirect influences, shaping attitudes or motivations. However, they can also reveal societal tensions or unintended effects of aspirational equality. But still, the mixed results, to some extent, might be influenced by the different methodologies used by various studies and by the complexity of the investigated phenomena (e.g., entrepreneurial intent) with many potential intervening variables. On the other hand, concerning these seemingly colliding results, more research would be needed to ascertain the thresholds for GE scores in both practices and values responsible for certain outcomes since, for instance, Cannavale et al. (2022) showed that at both very high and very low levels of GE practices, the enactment of entrepreneurial intentions into actual activities seemed to be inhibited.

4.2 A Multidisciplinary Perspective on GE-Related Research

The presented synthesis of studies tracing the impact of GE as a cultural dimension on different areas at the level of the organization and society as a whole reveals that gender issues have a wide reach into different areas of our lives. In this section, we will offer a multidisciplinary perspective on other aspects of gender issues that have been examined through the lens of GE as a cultural dimension but are also of interest to other disciplines.

First, from the viewpoint of leadership studies, the representation of women on corporate boards has emerged as a critical issue in contemporary business discourse, reflecting broader societal shifts toward gender equality. Research indicates that diverse leadership teams, particularly those that include women, enhance decision-making processes and drive better organizational performance (e.g. Belaounia, Ran, and Zhao 2020). Research by Simionescu et al. (2021) provided several managerial insights from Standard & Poor’s 500 Information Technology Sector, proving that a larger share of women on board may positively influence firm performance and enhance productivity, creativity, and innovation. Despite these benefits, women remain underrepresented in boardrooms globally, often facing systemic barriers that limit their advancement. Research indicates that men are often perceived as more competent due to prevailing stereotypes, which can undermine women’s influence in decision-making contexts (e.g., Carli 2017). As Else-Quest and Hyde (2017) suggest, the Social Role Theory posits that societal expectations about gender roles significantly shape behaviors and perceptions, affecting women’s participation in leadership. From our analysis, it is clear that GE, as a societal culture dimension, promotes the inclusion of women in leadership positions (Elango 2019), and it is also confirmed that firms that have women as CEOs perform better financially (Hoobler et al. 2018). Philosophical discussions often reflect on how societal views of wisdom are influenced by gender, suggesting that traditional notions favor male perspectives (Xiong and Wang 2021). This can impact how women’s contributions are valued in managerial settings. Ultimately, addressing the gender gap in board representation is not only a matter of equity but also a strategic imperative that can enhance organizational effectiveness and drive sustainable success in today’s diverse business landscape. A different perspective on the representation of women in top positions is through quotas. Recognizing women as a social collective is vital for highlighting structural inequalities between genders, justifying gender quotas as a legitimate tool to address these disparities (Mottlová 2015).

Second, from the perspective of organizational behavior, our study also contributes to the growing body of work-family research exploring international and cross-cultural factors impacting work-life balance and conflict (see, e.g., Ollier-Malaterre and Foucreault 2017, 2018]). These factors include both structural conditions, such as policies and availability of services, and cultural dimensions. However, while the role of structural factors is rather well described, the effect of culture is more ambiguous. Despite work-life conflict being closely related to the stereotypical gender roles division and thus to gender equality (Kaufman and Taniguchi 2019), studies included in this review do not show a straightforward and non-ambiguous relationship between GE cultural dimension and work-life conflict/balance. An accurate assessment of the role of cultural characteristics in work-life issues may require considering a combination of multiple cultural dimensions. For instance, dimensions such as humane orientation (Ollo-López and Goni-Legaz 2017) and individualism (Hsiao 2022) could significantly influence the moderation of work-life conflict/balance along with the GE cultural dimension.

Third, from the perspective of moral psychology, the findings of this overview suggest that the GE cultural dimension exerts a complex and multifaceted influence on ethical perceptions and behavioral intentions among men and women. Culture has an effect on gender differences in terms of ethical decision-making (e.g., Roxas and Stoneback 2004), with females’ decisions more dependent on contextual and cultural background compared to men (Beekun et al. 2010). Our overview shows, amongst others, an increased rationalization of unethical behavior among men (Chen et al. 2016), a higher tendency for ethical relativism (Alas, Junhong, and Jorge 2010), and a greater propensity for academic dishonesty, interestingly with less difference between males and females in high GE cultures (Fell and König 2020). The GE-related research seems to include a certain pattern that is in line with the moral psychology findings in that when it concerns ethical judgment ascertaining the ethical context of situations, females consistently demonstrate higher ethical judgment and a greater willingness to reject questionable activities compared to males across various contexts, including among students and marketing professionals (Lund 2008; Nguyen et al. 2008; Ruegger and King 1992; Swaidan, Rawwas, and Al-Khatib 2004). Also, findings from moral psychology and business ethics reveal a concerning bias in perceptions of ethical and deviant behavior, with “gray area” actions being viewed as more acceptable when carried out by males (Klein and Shtudiner 2021), and followers more inclined to challenge female leaders exhibiting deviance while avoiding or tolerating similar behavior from male leaders, potentially enabling unethical male leaders to retain their positions of authority (Pandey et al. 2021). Also, it was shown that men exhibit a stronger tendency toward unethical behavior, as evidenced by their greater likelihood of justifying unethical pro-organizational actions (Dadaboyev, Paek, and Choi 2023), engaging in unethical behavior generally (Bersoff 1999), and providing utilitarian responses to emotionally charged moral dilemmas, reflecting gender-specific cognitive and emotional processing (Fumagalli et al. 2010). However, prior research also indicates that females are more prone to responding in a socially desirable fashion. Dalton and Ortegren (2011) touched on this issue, showing that the effect of gender on ethical decision-making is largely diminished once social desirability is included in the analysis. While our understanding of actual ethical behavior differences between genders is limited, findings suggest that females tend to exhibit higher levels of ethical intent and judgment than males. This aligns with research on the GE cultural dimension, which highlights its role in moderating ethical perceptions and behaviors. In low GE cultures, the gender differences in ethical judgment and intent may be amplified, reinforcing the observed trends.

Fourth, taking a critical feminist studies perspective on the definition and operationalization of the GE dimension, it is important to note that although the general definition of GE as a cultural dimension provided by Emrich, Denmark, and Den Hartog (2004) can be considered a relatively broad one encompassing various aspects of gender equality/egality beyond gender equality in the labor market, the criteria the GLOBE framework adopted to assess the level of GE are on the other side relatively narrow, concentrating primarily on values and practices related to the position of women (and men) on the labor market and closely related fields such as education and politics. Our analysis also indicates a geographic bias in research focus, often aligned with the authors’ countries of origin. Studies on developing, economically poorer nations – frequently associated with undemocratic governance and limited basic provisions – are insufficient. The dynamics of cultural dimensions, including GE, likely differ significantly in such contexts compared to advanced economies, highlighting an important gap in the literature. The criteria assessed in GLOBE’s GE dimension can be compared with two major indexes measuring the level of gender (in)equality in society – Gender Equality Index (GEI) developed by the European Institute of Gender Equality (EIGE) and Gender Inequality Index (GII) developed by United Nation Developments Programme (UNDP). The GEI is calculated based on six domains – work, money, knowledge, time, power, and health, while the GII considers three dimensions – reproductive health, empowerment, and the labor market. Moreover, the GEI works with two additional domains (violence against women and intersecting inequalities), which are, however, not included in the index score calculations. There is also another index that concentrates more specifically on gender equality in companies – the Bloomberg Gender Equality Index. This index evaluates businesses based on five pillars - leadership and talent pipeline, equal pay and gender pay parity, inclusive culture, anti-sexual harassment policies, and external brand. Other areas that are interesting from the point of view of this index but are not measured are race and sexual orientation, gender identity, and ethnicity. We can observe that all these three indexes grasp the concept of gender equality much more broadly than the GLOBE framework. Thus, to truly assess the level of gender equality in a society, it is necessary to go beyond the question of power, predominantly connected with the public sphere. Hence, it is also crucial to assess how women are treated in the private sphere, in their families, households, and communities, especially in daily life, and what opportunities, rights, and responsibilities they have because the private sphere reflects how the values and practices are exercised daily for every woman. This perspective will bring into the picture critical aspects such as who bears the burden of care (for children, elderly, vulnerable, household, community, etc.), which is often invisible and hence unpaid, or the prevalence of gender-based violence (both in the private and public sphere, including sexual harassment in the workplace which is often described as a method of pushing women out of certain areas or positions) or other forms of oppression. Moreover, it is not sufficient to assess the level of GE in society solely by concentrating on the position of women as a unified group having the same experience. Different women have different experiences, own different forms of privilege, or face different forms of gender stereotypes, barriers, and oppression based on their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, social background, etc. Hence, the question of intersectionality is lacking in this dimension.

Additionally, we shall not only ask who is in the position of power but also how they exercise this power and what type of leadership they perform. If the women in positions of power reproduce practices and values that lead to discrimination and inequality in the workplace and broader society, then greater equality is not achieved. This brings us to feminist leadership (Batliwala 2011) as an alternative for more egalitarian societies and organizations and sheds light on criteria we should consider when assessing GE. We can perhaps consider feminist leadership in the Global South a contribution to a debate on envisioning fair and just organizations and societies. Although all indexes have their limitations and can be deemed as an oversimplification of complex reality and relationships in societies and companies, there are many authors who are critically assessing either GEI or GII whether in relation to their measurement (e.g., Schmid and Elliot 2023) or their applicability (e.g., Permanyer 2013). It is naïve to expect that any measurement of such complex issues as (gender) (in)equality would be perfect. For future research, it would be beneficial to examine more closely how GE, as a cultural dimension, aligns with other metrics of measuring gender equality and to explore the potential correlations or underlying connections between them.

4.3 Practical Implications

Our overview of the empirical results concerning GE can be leveraged to develop practical implications relevant to both managers and policymakers. For instance, as for a more systematic support of entrepreneurship, policymakers should pay attention to enhancing specific entrepreneurial support systems for women, as higher GE practices correlate with increased female participation in entrepreneurship (e.g., Baughn, Chua, and Neupert 2006). These programs could include access to funding, mentorship, and training tailored to the unique needs of women entrepreneurs. Also, women may perceive less external support and hold more negative attitudes toward entrepreneurship (e.g., Steinmetz, Isidor, and Bauer 2021). Policymakers in such societies should focus on reshaping societal attitudes and public awareness campaigns to encourage entrepreneurial activities among women. Also, institutional support and targeted funding to non-governmental organizations dedicated to reducing the gender gap and promoting women’s participation in entrepreneurship could be beneficial. Furthermore, as business associations constitute an important pillar of the business environment, they should adopt and actively integrate this agenda into their operations. In countries with high GE, where entrepreneurial intentions are lower, and fear of failure is higher (Calza, Cannavale, and Zohoorian Nadali 2020), policymakers should design programs aimed at reducing the psychological barriers to entrepreneurship. These programs could include support systems and model success stories that normalize experimenting and related failure as a natural part of entrepreneurship. In sum, in both high and low GE societies, different dynamics influence the enactment of entrepreneurial intentions into activities. Policymakers and organizations should design culture-sensitive interventions that address these nuances. For example, in high GE societies, addressing structural inhibitors like fear of failure, and low GE societies focusing on enhancing women’s access to resources and training.

Another significant domain identified in our review study is the realm of work-family and work-life balance. The findings highlight the role of GE as a moderator in reducing gender disparities in work-life outcomes. Policymakers should integrate these insights into public discourse, e.g., policy dialogues to advance gender equality. For instance, high GE cultures show stronger positive associations between work-life balance, life satisfaction, and anxiety (Haar et al. 2014). Employers should offer mental health and support systems and promote a culture of openness around work-life challenges to maximize these benefits. Organizations should focus on enabling work-family balance through initiatives like skill-sharing and mentoring programs in family-related benefits. Managers in these contexts should be trained to recognize and mitigate biases connected with low work-life balance among employees, particularly for women. Where women face greater gender-based challenges (Halliday et al. 2018), they could benefit significantly from greater job autonomy, which enhances work-life balance and job satisfaction. Employers in these contexts should prioritize flexible work-related policies, such as flexible scheduling and greater autonomy in deciding when and from where to work. In high GE cultures, women benefit more from achieving work-life balance in terms of career advancement potential (e.g., Lyness and Judiesch 2008). In this context, organizations should emphasize fluid job designs and install job crafting and work-life balance initiatives to foster inclusive career advancement. Connected with that, organizations should implement bias-awareness training for HR professionals and managers who conduct employee performance evaluations. Since individuals in high GE societies may be less inclined to separate family and work life (Allen et al. 2024), employers should offer tailored hybrid work arrangements. Furthermore, in low GE cultures, mothers might experience more work-family conflict (Hsiao 2023). Therefore, organizational initiatives in these countries should emphasize the value of shared family responsibilities and actively support programs encouraging men’s involvement in family life. Also, where fathers experience greater work-family due to increased family expectations (Hsiao 2023), organizations and policymakers should design targeted family-friendly policies, such as paternal leave for both men and women.

Another key area highlighted by our review is the field of leadership development in organizations. In high GE cultures, leadership competencies that emphasize collaboration, inclusiveness, and fairness are highly valued (e.g., Gentry and Sparks 2012; Li et al. 2021). Organizations operating across diverse cultural contexts should adapt leadership development strategies to match these cultural preferences. Leadership training programs should prioritize developing these traits to align with cultural expectations and enhance effectiveness. Furthermore, high GE cultures can create environments where women are more likely to emerge as leaders due to societal norms favoring equality (e.g., Toh and Leonardelli 2012). Organizations should leverage this by actively supporting women’s leadership development through mentoring, training, and fairness in career promotion planning. In less egalitarian cultures, raising awareness of potential gender biases and implementing diversity and inclusion initiatives can help shift cultural norms and reduce discriminatory practices. Organizations should also enforce strict anti-discrimination policies, provide clear grievance mechanisms, and foster open dialogues on dilemmas experienced by employees. In low GE cultures, governments and organizations should prioritize initiatives aimed at reducing traditional gender role attitudes and legal reforms ensuring equal pay and anti-discrimination protections.

4.4 Limitations

While this literature review offers a comprehensive synthesis of the body of knowledge on GE as a societal cultural dimension, several limitations must be acknowledged, as they may influence the scope and depth of the analysis. As is typical of the literature review methodology, certain inherent limitations are associated with this approach. These often connect with the reliance on databases as primary sources of knowledge, the application of inclusion criteria, the challenges associated with processing large volumes of information, and the subsequent presentation and interpretation of results (e.g., Papaioannou et al. 2010; Snyder 2019). This review excluded non-peer-reviewed work, i.e., grey literature and preprints, and relied primarily on peer-reviewed publications, which may be subject to publication bias. Although a systematic search strategy was employed, the reliance on specific databases and the searched keywords may have led to omitting some studies in the field. We sought to address this limitation by implementing a comprehensive and iterative search strategy and conducting multiple rounds of testing to identify the most effective keyword combination.

Another limitation lies in the inclusion of only studies published in English, which may constrain the breadth of the findings by excluding potentially relevant research published in other languages. Further, our study presents the findings in a narrative way, synthesizing existing knowledge without employing systematic or meta-analytical methods. While this approach offers flexibility and allows for a deep, interpretative synthesis, it also has several weaknesses (e.g., Baumeister and Leary 1997). For instance, integrating studies with diverse designs, varied terminology, methods, and contexts can pose a significant challenge since the findings depend on how the original authors presented their data. Also, in general, reviews can synthesize findings from studies of varying methodological quality.

To mitigate these limitations, we made efforts to assess the methodological rigor of included studies, carefully applied inclusion criteria for the inclusion of studies, and presented a clear and replicable methodology (see Section 2). We also employed a structured approach by organizing the reviewed literature into thematic subgroups based on their conceptual proximity and identifying common themes within each subset to facilitate more targeted conclusions. Furthermore, in presenting the overview, we provided not only the synthesized results but also contextualized them by highlighting the specific contexts of the included studies.

Finally, a limitation of the GE measure is that it may result in a somewhat reductionist interpretation of the intricacies of social reality. On the other hand, the GLOBE measures have garnered widespread recognition and are among the most utilized frameworks in comparative research, particularly in the fields of cross-cultural management and organizational behavior. Their popularity stems from their robust theoretical foundation and extensive empirical validation across diverse cultural settings. This approach enables the comparison of phenomena such as GE across a wide range of countries, which can provide valuable insights into cross-cultural differences and similarities, facilitate the identification of common patterns, and support the formulation of theories and policies that address cultural diversity on a global scale.

5 Conclusions

This study aimed to provide an integrative overview of empirical results connected with GE as a cultural dimension. The findings presented in this paper underscore the role of GE in various aspects of management and broader social and economic contexts. More attention should be given to the issues discussed above regarding how the GE was assessed. This may lead to the replication of a narrow view of gender equality and skew the results of how this dimension interacts with various areas. Also, more research is needed focusing on the countries of the Global South as they have much to offer in this regard.

From a practical angle, it becomes evident that many stakeholders, particularly managers working in cross-cultural environments, should find it valuable to consider GE as a cultural dimension when shaping policies and strategies. Practical measures such as promoting workplace diversity, encouraging gender diversity in leadership roles, implementing equal pay policies, offering gender-neutral parental leave, and supporting flexible work arrangements are crucial to achieving greater gender egalitarianism in the workplace. For policymakers, recommendations could entail enforcing transparent reporting of state-level and corporate diversity programs and developing frameworks for monitoring progress toward gender equality. They can also launch public awareness campaigns that challenge traditional gender norms. Additionally, considering intersectionality (i.e., how other factors, such as ethnicity, class, or sexual orientation, intersect with gender) in policy design safeguards addressing the unique challenges different identities face.

Funding source: Vedecká grantová agentúra MŠVVaM SR a SAV (VEGA)

Award Identifier / Grant number: VEGA no. 1/0419/22

Acknowledgement

This paper was developed at Comenius University Bratislava, Faculty of Management, within the project VEGA no. 1/0419/22.

-

Research funding: This study was developed at Comenius University Bratislava, Faculty of Management, within the project VEGA no. 1/0419/22.

-

Declaration: All individuals listed as authors qualify as authors and have approved the submitted version. Their work is original and is not under consideration by any other journal. They have permission to reproduce any previously published material.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Paulína Mihaľová, upon reasonable request.

References

Alas, Ruth, Gao Junhong, and Carneiro Jorge. 2010. “Connections between Ethics and Cultural Dimensions.” Engineering Economics 21 (3).Search in Google Scholar

Alexander, Katherine C., D. Mackey Jeremy, Liam P. Maher, Charn P. McAllister, and B. Parker Ellen. 2024. “An Implicit Leadership Theory Examination of Cultural Values as Moderators of the Relationship between Destructive Leadership and Followers’ Task Performance.” International Business Review 33 (3): 102254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2024.102254.Search in Google Scholar

Allen, Tammy D., Kimberly A. French, Soner Dumani, and Kristen M. Shockley. 2015. “Meta-Analysis of Work–Family Conflict Mean Differences: Does National Context Matter?” Journal of Vocational Behavior 90 (október): 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.07.006.Search in Google Scholar

Allen, Tammy, Barbara Beham, Ariane Ollier-Malaterre, Andreas Baierl, Matilda Alexandrova, Alexandra Beauregard Artiawati, et al.. 2024. “Boundary Management Preferences from a Gender and Cross-Cultural Perspective.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 148 (február): 103943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2023.103943.Search in Google Scholar

Aria, Massimo, and Corrado Cuccurullo. 2017. “Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis.” Journal of Informetrics 11 (4): 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007.Search in Google Scholar

Ayob, Abu H., Hamizah Abd Hamid, and Farhana Sidek. 2022. “Individual Values and Career Choice: Does Cultural Context Condition the Relationship?” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 22 (2): 560–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12306.Search in Google Scholar