Abstract

The application of synthetic riboswitches or aptamer-based biosensors for the monitoring of engineered metabolic pathways greatly depends on a high degree of target molecule specificity. Since metabolic pathways include close derivatives that often differ only in single moieties, the binding specificity of aptamers utilized for these systems has to be high. In the present study, we selected an RNA aptamer that is highly specific in its binding to homoeriodictyol while discriminating its close derivatives eriodictyol and naringenin. This high degree in specificity was achieved through three consecutive SELEX approaches while the selection parameters were adjusted and refined from one to the next. The adjustments along the process, with the selection outcome and next-generation sequencing analysis of the selection rounds, led to valuable insights into the stringency necessary to facilitate target specificity in aptamers obtained from SELEX. From the third selection, we obtained a highly binding specific aptamer and examined its structure and binding properties. Overall, our results connect the importance of selection stringency with SELEX outcome and aptamer specificity while providing a highly selective, homoeriodictyol-binding RNA aptamer.

1 Introduction

Aptamers are short single-stranded RNA or DNA molecules that can bind to a target molecule with high affinity and specificity. They are selected de novo through SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by EXponential enrichment) (Ellington and Szostak 1990; Tuerk and Gold 1990), an iterative process for selecting target molecule binding sequences from a random library of oligonucleotides. Since the invention of SELEX in 1990, constant development has led to numerous different SELEX methods adapted for the efficient selection of aptamers with specific characteristics. Among these methods are Cell-SELEX, developed for the selection of aptamers against the surface of living cells (Homann and Göringer 1999; Morris et al. 1998), paramagnetic bead-based SELEX, developed for efficient selection of protein-binding aptamers (Bruno 1997; Vockenhuber et al. 2023) and Capture-SELEX, which facilitates the selection of aptamers showing ligand-induced conformational changes (Boussebayle et al. 2019; Stoltenburg et al. 2012) just to name a few. With a de novo selection, aptamers for binding virtually any given target molecule can be obtained. This possibility, combined with their excellent binding properties, has led to a multitude of applications for aptamers. Some examples include their use in biosensors for the detection of water contaminants (Thavarajah et al. 2020; Yildirim et al. 2012), their application in lateral flow assays (Kramat et al. 2024), the live observation of metabolite dynamics by combination with light-up aptamers (You et al. 2015) or the binding of proteins and subsequent inhibition of their function (Amano et al. 2021; Hunsicker et al. 2009).

Virtually all applications of aptamers rely on good binding properties and a high degree of binding specificity toward the target molecule. Therefore, carefully performed in vitro selections, including monitoring stringency and pre- and counter-elution steps as well as changing setups between selection rounds, have been introduced to shape selection outcomes (Famulok 1994; Kramat et al. 2024; Ohuchi and Suess 2017). An interesting example of the unforeseen consequences that selection design can have on the results of SELEX is the tobramycin riboswitch (Kraus et al. 2023). The aptamer sequence for the tobramycin riboswitch came from a SELEX for kanamycin A, a close derivative of tobramycin. The SELEX did not include a counter-selection until the final round of selection, and the enriched sequences were found to bind with higher affinity to tobramycin than to the selection target, kanamycin A. While this was a serendipitous result that led to the development of one of the best performing synthetic riboswitches known to date, improper SELEX design more commonly leads to negative results. For example, we have observed that a selection without pre-selection against bead-, sepharose- or other column-binding sequences usually leads to rapid enrichment of sequences binding to the solid parts of the selection setup instead of the selection target. Therefore, most SELEX protocols include pre-selection steps to avoid this unwanted enrichment (Famulok 1994; Ohuchi and Suess 2017; Valero et al. 2021). Careful design of the SELEX protocol is even more important when selecting for an aptamer capable of discriminating between a target molecule and close derivatives.

In this study, we aimed to select an aptamer capable of specifically binding to homoeriodictyol over its close derivatives eriodictyol and naringenin, which only differ in one chemical moiety (Figure 1A). All three substances are flavanones, a group of naturally occurring secondary plant metabolites that can be found in citrus plants (Khan et al. 2014), and are highly potent bitter masking agents (Ley et al. 2005). This property has made them valuable additives in oral medicines, for masking the bitter taste of many pharmaceutical ingredients (Beltrán et al. 2022). For efficient and reliable production of these substances, biotechnological production processes have been developed to transfer the biosynthesis from plants to bacteria (Pandey et al. 2016). To monitor flavanone production in vivo, efforts have been undertaken to engineer synthetic riboswitches for naringenin concentration readout (Jang et al. 2017). Furthermore, aptamer-based biosensors have been generally proposed for the monitoring of biotechnological production processes (Shi et al. 2017). For these applications, aptamers with high specificity are crucial for the correct function of the engineered system.

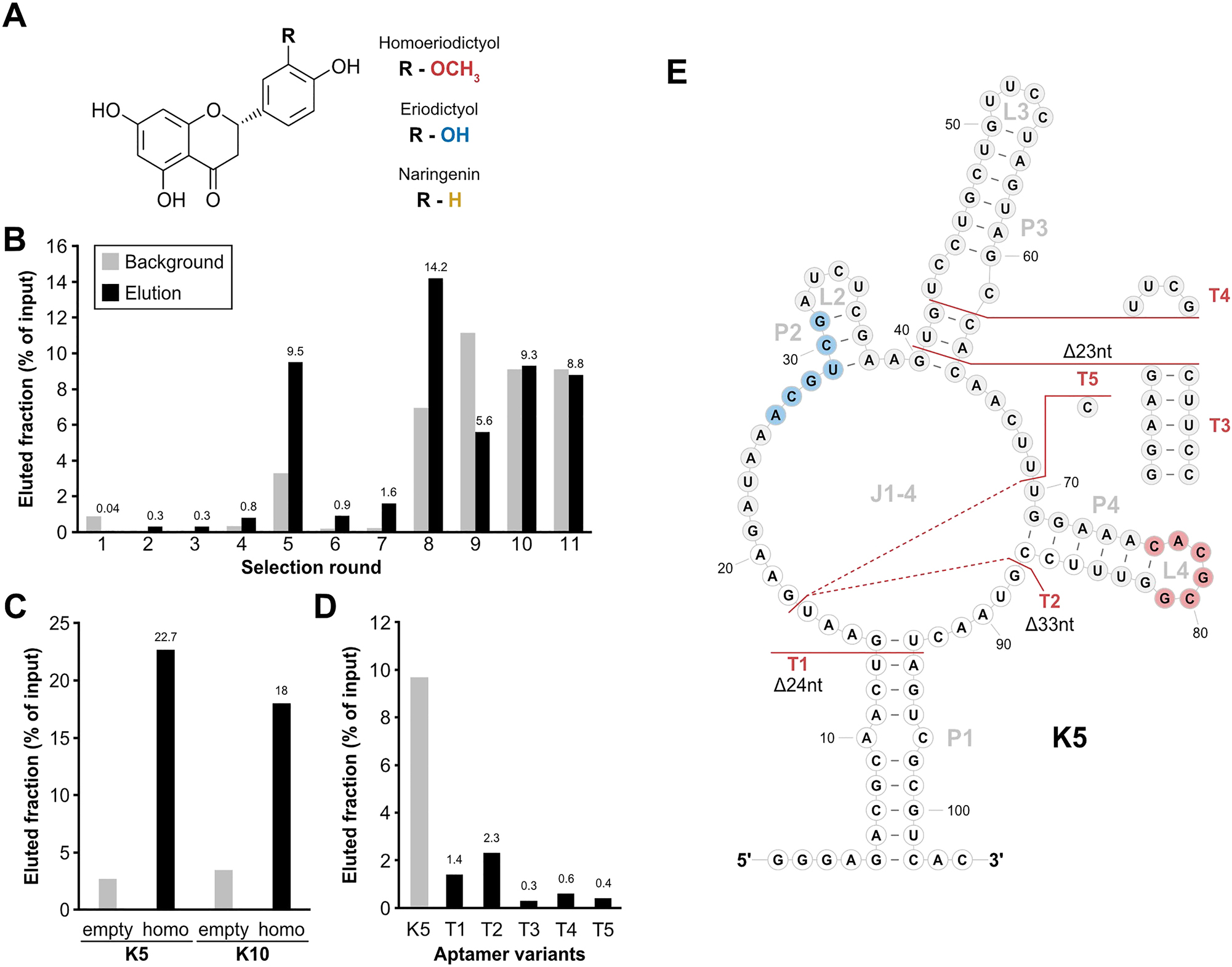

Column-based SELEX with a randomized N64 library. (A) Basic molecular structure of homoeriodictyol and its close derivatives eriodictyol and naringenin. Difference between the derivatives consists in one residue (R) and the corresponding groups of the different substance are indicated (red: homoeriodictyol, blue: eriodictyol, yellow: naringenin). (B) Progression of the in vitro selection process. Fractions of eluted RNA (black) and background (light grey) are depicted in percent relative to the input corresponding to selection rounds. Mentioned above the columns is the value of the eluted fraction of each round. (C) Binding assay of the aptamer candidates K5 and K10. Shown is the eluted fraction for both candidates from either an uncoupled control column (empty) or a homoeriodictyol-coupled column (homo). (D) Binding assay of the truncations of K5. Shown are the eluted fractions from a homoeriodictyol-coupled column of the full-length candidate K5 and 5 truncations of K5. (E) Secondary structure depiction of aptamer candidate K5 with indications of the tested truncation T1-T5. Nucleotides with white background indicate the sections of the constant regions. The identified binding motifs for homoeriodictyol are highlighted in blue (motif 1) and red (motif2). The shown structure is based on a folding prediction from RNAfold (Lorenz et al. 2011).

In the present study, we refined selection parameters over the course of three in vitro selections to select an RNA aptamer with specificity to its ligand homoeriodictyol. The insights gained along this process highlight parameters important for the selection of highly specific aptamers in general and can employed as a general framework for the selection of aptamers for other target molecules. Such aptamers, like our final candidate A1, can be suitable for applications in production processes where the target molecule and several close derivatives are present (Liu et al. 2013).

2 Results

2.1 Conventional column-based SELEX for an RNA aptamer binding homoeriodictyol

We started our selection approach with a conventional in vitro selection in which the ligand was immobilized on a solid support (column). For this, homoeriodictyol (Figure 1A) was coupled to epoxy-activated sepharose, using a 1,4-diaminobutane linker and a subsequent Mannich reaction. This unusual coupling strategy was necessary due to the instability of homoeriodictyol at high pH (Figure S1C) which is commonly used for the coupling of small molecules. The efficient coupling of homoeriodictyol to the resin was monitored by measuring the absorbance of the homoeriodictyol-containing solution at 290 nm before and after the coupling reaction (Figure S1D). Based on the difference in homoeriodictyol concentration in solution before and after coupling, 57 % of the homoeriodictyol have been coupled to the resin.

In vitro selection was then performed using a randomized 64 nucleotide long library (N64 pool). For each step, we performed pre-selection on an uncoupled column with subsequently incubating the RNA pool with the homoeriodictyol-coupled column. Although overall recovered RNA fractions increased over the course of 11 selection rounds, while adapting selection stringency through counter-elution steps and specific elution with 1 mM homoeriodictyol, no specific enrichment of binding to homoeriodictyol was achieved (Figure 1B, detailed selection parameters see Table S1). With similar or lower RNA amounts found in the eluted fraction as in the washing step (background) in later rounds, the selection was stopped.

Although the pool showed no enrichment, round 11 was analysed by sequencing for enriched sequences. Out of 28 sequences, 26 turned out to be individual candidates. The binding capacity of 17 candidates was assessed by a column-based binding assay and revealed only 3 candidates with binding affinity exceeding binding of the pool from round 5 (Figure S1E). The two candidates with the highest levels of eluted RNA (K5 and K10) showed no unspecific binding to the column material, while candidate K5 showed the highest binding with 22.7 % RNA eluted from the homoeriodictyol-coupled column (Figure 1C). The secondary structure of K5 was predicted as shown in Figure 1E (Lorenz et al. 2011). To gain further insight into the structure of the candidate K5, five truncated versions of the aptamer were designed (Figure 1E) and tested for binding homoeriodictyol. All truncations led to a complete loss of binding (Figure 1D).

Based on the outcome of the in vitro selection with no clear sign of specific enrichment for target binding (Figure 1B), an aptamer candidate which was difficult to examine by mutational studies and no sign of sequence enrichment in the sequencing results, we decided to improve the selection parameters.

We started a new selection with a larger library (74 randomized nt, N74 pool) which may facilitate the formation of more intrigued binding pockets. Moreover, this pool has been used successfully in the past for the selection of several high-affinity aptamers (Berens et al. 2001; Famulok 1994; Wallis et al. 1995). In vitro selection was started again by subjecting 2 nmol RNA of the N74 pool to a uncoupled pre-selection column, followed by a homoeriodictyol-coupled column and eluting unspecific with 20 mM EDTA (detailed selection parameters see Table S2). In contrast to the previous SELEX, from the second round onwards the RNA was eluted specific with 1 mM homoeriodictyol to enhance a specific selection of homoeriodictyol-binding RNAs. After the first sign of increased binding to the homoeriodictyol-coupled column in round 5, the washing steps were increased from 10 column volumes (CV) to 20 CV to increase selection stringency (Figure 2A). After an immediate decrease of the eluted RNA fraction in round 6, the amount of eluted RNA recovered in round 7. Thus, the washing steps were further increased from round 8 on to 25 CV to remove weak or unspecific bound candidates before elution. With further increased binding of the RNA to the homoeriodictyol-coupled column in round 9, a counter elution with an eriodictyol-coupled column was performed in round 10 to facilitate the specificity towards homoeriodictyol. To promote the selection of aptamers with strong binding, pre-elution steps were introduced from round 11 on to remove weak bound RNAs before recovering RNA for the next selection round. This was done by performing two additional steps of elution with homoeriodictyol and discarding the eluted RNA, before the subsequent elution steps to recover RNA. By removing target-binding RNAs in the pre-elution that are easily detached from their ligand, it is thought to favor the selection of RNAs with a lower KD and thereby selecting aptamers with a high binding affinity to the target. The selection was stopped in round 13 when the eluted RNA reached a level of 8.9 % relative to input and a background of 3.4 %, indicating a specific enrichment of homoeriodictyol-binding RNAs (Figure 2A).

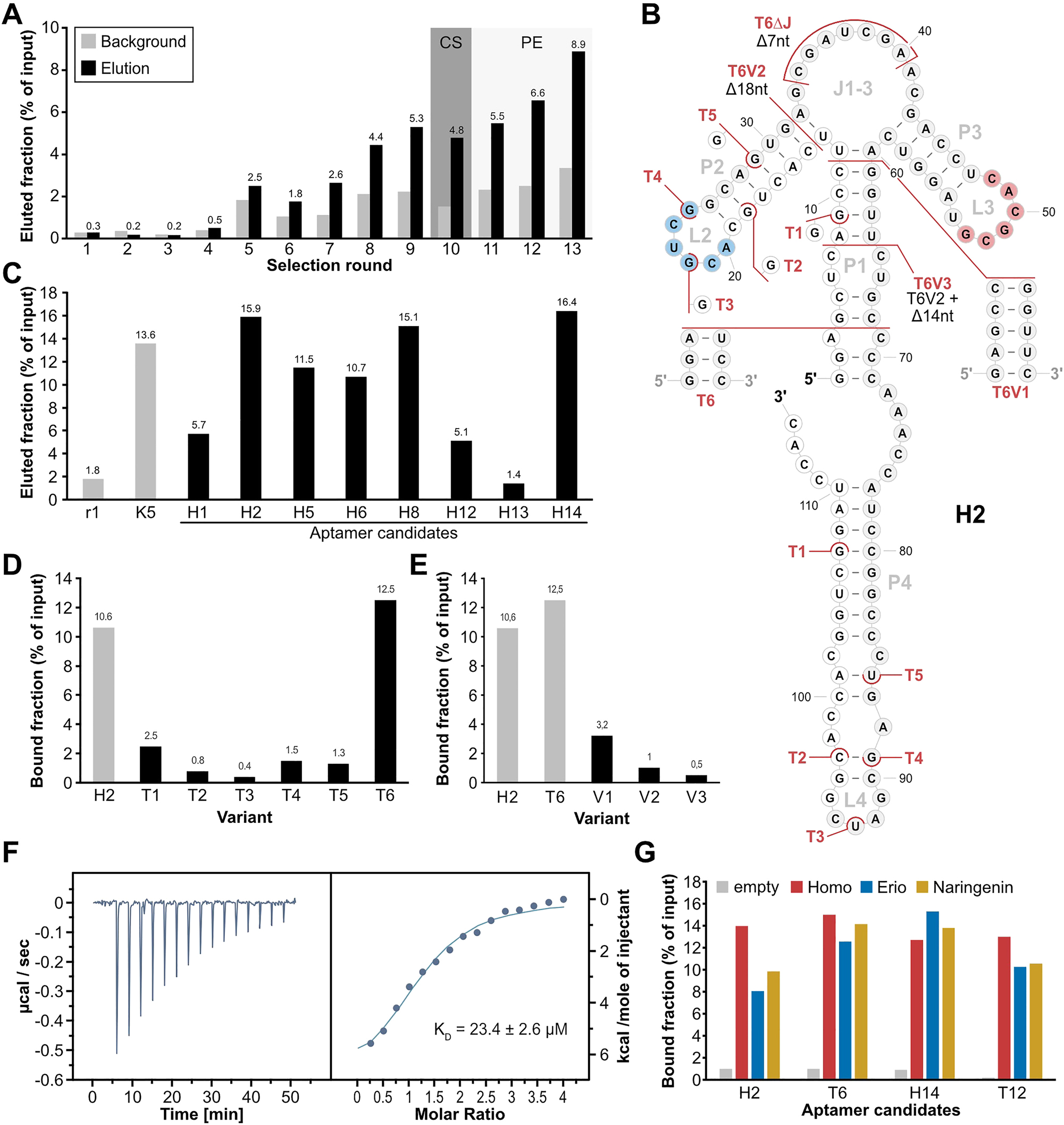

Column-based SELEX with a N74 library. (A) Progress of the column-based SELEX using the N74 pool, showing the eluted fraction (black) and background level (grey) over the course of the selection rounds. Numbers above the columns show the value of the corresponding elution fraction. Round 10 including a counter-selection (CS) step is indicated by a grey background. Rounds including pre-elution steps (PE) are indicated by a light grey background. (B) 2D representation of aptamer H2, based on folding prediction from RNAfold (Lorenz et al. 2011). White background of nucleotides indicates sections of the constant regions, grey background indicates the randomized region. The homoeriodictyol-binding motifs 1 (blue) and 2 (red) are indicated. Truncations T1-T6 and mutations of T6 (V1-3) are indicated in red. (C) Binding assay of aptamer candidates from round 13 of the column-based SELEX using N74. Round 1 of this selection and aptamer K5 were used as controls for binding to homoeriodictyol. (D) Binding assay of truncated versions of H2 (T1-T6) in comparison to the full-length aptamer H2. (E) Binding assay of the mutations of T6 (V1-V3) in comparison to H2 and its truncation T6. (F) Representative Thermogram and titration curve of isothermal titration calorimetry with T6 titrating homoeriodictyol. (G) Binding assay testing binding specificity of H2, T6, H14 and T12. The aptamers were incubated either with an uncoupled column (grey) or a homoeriodictyol-coupled column and then eluted by washing with either 1 mM homoeriodictyol (red), eriodictyol (blue) or naringenin (yellow).

Again, single candidates were identified by cloning and sequencing. Results of 40 clones revealed 28 individual sequences. Out of the 40 analyzed clones, a single candidate appeared five times (H2) and two other candidate sequences were present three times. Eight of these sequences were picked for binding assay to homoeriodictyol, including the most abundant ones from the sequencing (Figure 2C). Two candidates possessed substantially lower values compared to K5 and one candidate was lower in elution level than the initial round 1. Candidates H2, H8 and H14 possessed elution values exceeding the elution of K5, indicating good binding affinity towards homoeriodictyol. H2 and H14 were chosen for further characterization, due to multiple appearance in the pool (H2) and highest eluted fraction (H14, 16.4 %). For both candidates, six truncations were designed based on their 2D folding prediction (Lorenz et al. 2011) (T1-T12, Figures 2B and S2A) to gain insight into their structure and reduce the size of the aptamer. Truncations were either designed to shorten the aptamer from the 5′ or the 3′ end of the sequence (T1-T5, T7-T10), or to shorten the aptamer below a section expected to be involved in target binding (T6, T11, T12). Only the truncation T6 of H2 and the truncation T12 of H14 maintained binding to homoeriodictyol as shown by the column-based binding assay (Figure 2C and Figure S2C). In direct comparison, T6 possessed the best binding of all truncations with 12.5 %, exceeding the bound fraction of its full-length aptamer H2. T12 instead showed lower binding than T6 with 11.2 % bound fraction and showed even lower binding than H14 (Figure S2C). Based on the successful truncation of H2 with T6, three further mutations of T6 were created (Figure 2B). Mutation T6V1 further shortened the P1 stem, T6V2 removed the P2-L2 region of the aptamer to test for importance of this section of the aptamer and T6V3 combined T6V2 with a slightly shorter P1 stem. Binding assay of the new truncations revealed a loss of binding to homoeriodictyol for all three (Figure 2E).

Based on the higher binding values of T6 compared to T12, T6 was chosen for further characterization. We performed isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to assess the binding affinity of T6 to homoeriodictyol. The analysis revealed a final KD of 16.6 ± 11 µM (N = 3, Figure 2F). We next performed in-line probing to confirm the predicted folding of the aptamer. Position reactivity supported the predicted structure, with the highest reactivity occurring in the unbound regions L2, J1-3 and L3 (Figure S3A). When comparing the reactivity in presence or absence of 100 µM homoeriodictyol, no change in position reactivity was noticeable, indicating no change in aptamer structure upon ligand binding. Next, we analyzed binding to close derivatives of homoeriocictyol to test for the specificity of the aptamer. H2, H14, T6 and T12 were incubated with columns coupled with homoeriodictyol or an uncoupled column and eluted with BB containing 1 mM of either homoeriodictyol, eriodictyol or naringenin (Figure 2G). All four aptamers showed no discrimination against the close derivatives of homoeriodictyol, as shown by the high elution values obtained from the washing with the respective derivatives.

2.2 Identification of homoeriodictyol-binding motifs

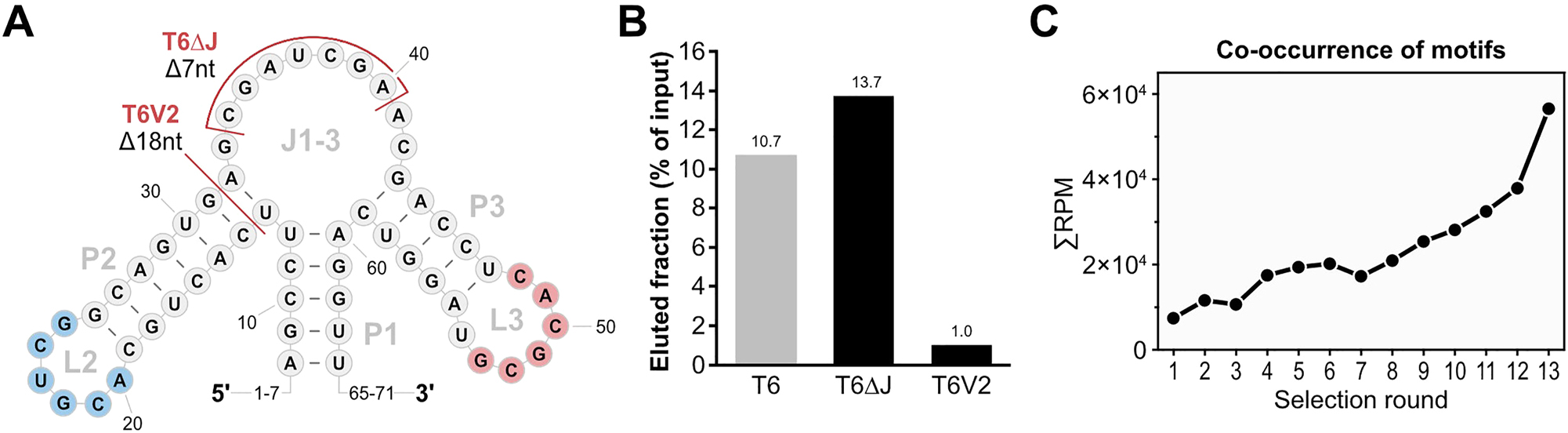

While comparing the aptamer candidates from the first two selections, we noticed two sequence motifs that appeared in both K5 from the first in vitro selection and H2 from the second in vitro selection (M1: 5′-ACG UCG-3′, M2:5′-CAC GCG-3′, Figures 1E and 2B). Having these motifs present in both homoeriodictyol-binding sequences selected from two independent pools and in vitro selections, strongly suggested a role in the binding of homoeriodictyol. This was further supported by the truncation T6V2 of the aptamer H2, where the truncation removed motif 1 and resulted in a loss of binding to homoeriodictyol (Figures 2E and 3B). We also generated another variant of T6 to further investigate the role of these motifs, where we deleted seven nucleotides of the junction area J1-3 to test whether the remaining P2-L2 and P3-L3 regions are sufficient for homoeriodictyol binding (T6ΔJ, Figures 2B and 3A). When comparing the binding to homoeriodictyol of T6 and T6ΔJ, both sequences bound comparable fractions of RNA, indicating no loss of binding (Figure 3B). To further investigate the role of the two motifs in the binding of homoeriodictyol, we sequenced the pools of each round from the second in vitro selection by next-generation sequencing (NGS) and analyzed the co-occurrence of the motifs over the course of the selection (Figure 3C). With progress of the selection, the number of reads carrying both motifs continuously increased, further supporting a role of the two motifs in homoeriodictyol binding.

Identification of Homoeriodictyol-binding motifs. (A) Apical structure of T6 relevant for the identification of the homoeriodictyol-binding motifs. Identified motifs are highlighted in blue (motif 1) and red (motif 2). Mutations of T6 related to the function of the motifs are indicated in red (T6V2 and T6ΔJ). Left out nucleotide positions at the 5′- and 3′-end are indicated by numbers. (B) Binding assay results of the mutations of T6 connected to the identified motifs in comparison to T6. (C) Analysis of co-occurrence of the two motifs on sequences over the course of the N74 SELEX by NGS. The number of reads containing both motifs is given in reads per million (RPM) over the selections rounds of the SELEX.

2.3 Doped Capture-SELEX delivering a highly specificity homoeriodictyol RNA aptamer

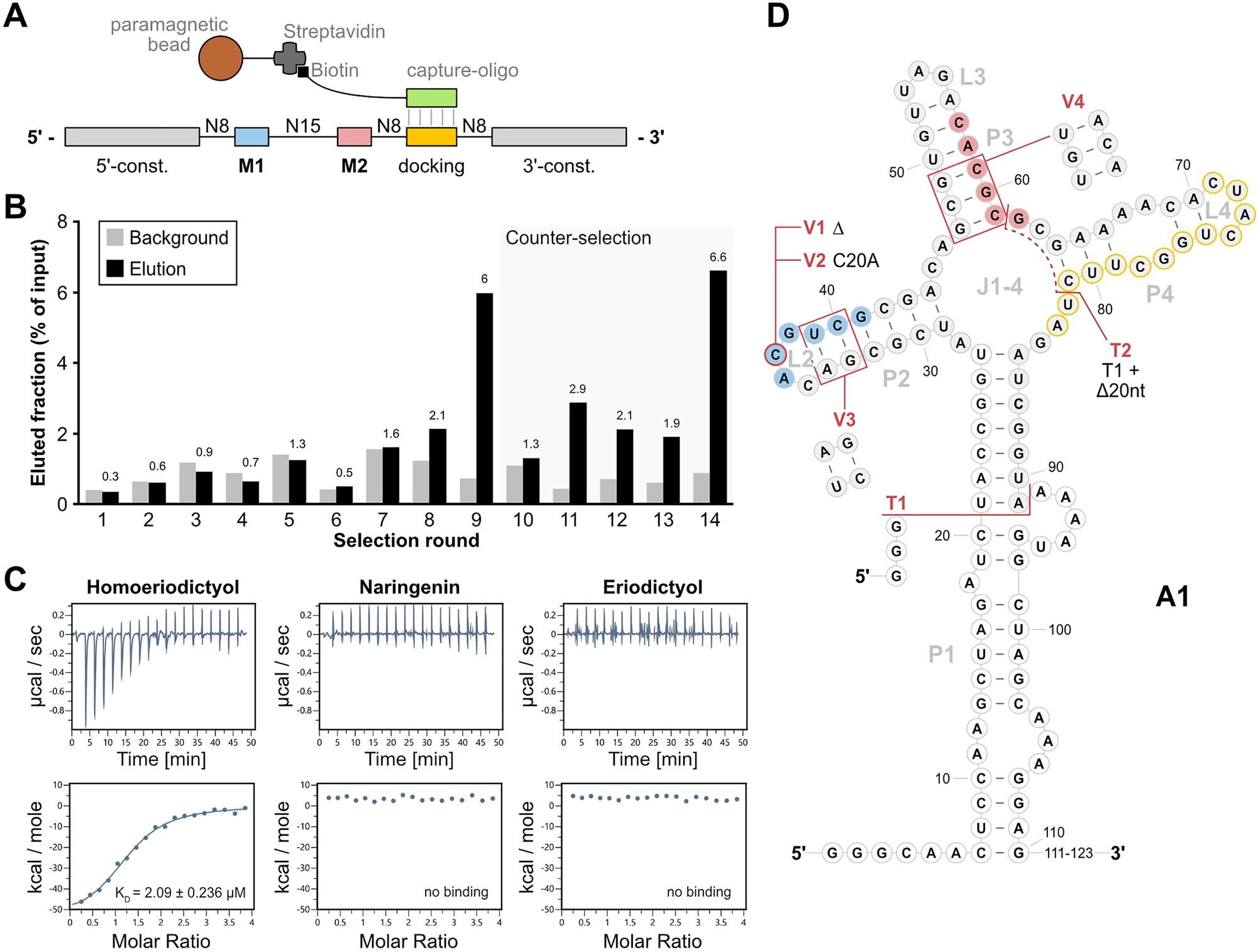

After the first two attempts to select a RNA aptamer binding homoeriodictyol with high affinity and specificity, we decided to readjust our approach of the selection method from the column-based selection to Capture-SELEX (Boussebayle et al. 2019). This was done due to the mode of selection of this method, where the RNA pool is immobilized by hybridization to a capture-oligonucleotide while the ligand is free in solution (Figure 4A). By eliminating the need of immobilizing the ligand, all chemical moieties of homoeriodictyol were now available for binding interactions with the RNA library, enabling the possibility for higher specificity in ligand binding. With the decision to change our SELEX method, we also decided to include the previously found motifs in our pool design to facilitate binding to homoeriodictyol. This new pool design consisted of the two motifs embedded between sections of randomized nucleotides and a docking sequence for the capture oligonucleotide as shown in Figure 4A. Overall, the pool included 39 randomized nucleotides, and the two motifs were not part of any primer-binding region, allowing for mutations of these sequence sections over the course of selection.

Selection of A1 by motif-doped Capture-SELEX. (A) Doped Capture-SELEX pool design with immobilization mechanism through hybridization of the docking sequence to the capture-oligonucleotide and Streptavidin-Biotin interaction. The incorporated motifs are indicated as M1 (blue) and M2 (red), while the docking sequence for immobilization is indicated as “docking” (yellow). The pool is immobilized by hybridizing the docking sequence to a DNA capture-oligonucleotide (green) that is coupled to paramagnetic beads by biotin-streptavidin interaction. (B) Progress of the Capture-SELEX. Shown are the fractions of background (light grey) and specifically eluted RNA (black). Values of the eluted fraction are indicated above the columns. Rounds including a counter-selection step with 1 mM eriodictyol and naringenin are indicated by a light-grey background. (C) Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) results of A1 with homoeriodictyol, naringenen and eriodictyol. Shown are thermograms and titration curves of the three measurements. (D) Depiction of the secondary structure of A1 as predicted by RNAfold (Lorenz et al. 2011). The motifs 1 (blue) and motif 2 (red) as well as the docking sequence (yellow outline) are highlighted. White background of nucleotides indicates sections of the constant regions while grey background indicates parts of the randomized region. The modifications of the aptamer are indicated in red, showing the first truncations T1 and T2, and the subsequent mutations of T1 V1-V4. The last 12 nucleotides of the aptamers 3′-end are indicated as “111–123”, since they were removed with T1 and were predicted to show no secondary structure.

The Capture-SELEX was started by immobilizing 2 nmol of the doped pool to paramagnetic beads. After washing the beads with buffer, the RNA was eluted by washing the beads with 1 mM homoeriodictyol in 1x CSB. During the first 7 rounds of selection, the eluted fraction was lower or equal to the background signal (Figure 4B, for detailed selection parameters see Table S3). The eluted fraction exceeded the background the first time in round 8 with 2.1 % and further increased in round 9 to 6 %. To avoid enrichment of non-specific binders, a pre-selection with 1 mM eriodictyol and 1 mM naringenin before the specific elution with homoeriodictyol was introduced from round 10 onwards. This led to a decrease in eluted fraction to 1.3 % in round 10. The eluted fraction fluctuated between 2.9 % and 1.4 % from round 11 to 13 but always exceeded the background signal. In round 14, the eluted fraction increased to the highest eluted fraction of 6.6 % while the background stayed low with 0.9 %, indicating a specific enrichment of homoeriodictyol-binding RNAs (Figure 4B). To gain an insight into the enriched pool, 96 colonies were used for sequencing. It revealed 34 individual candidates out of these 96 clones. The most abundant candidate was A1 with 21 sequences and a point mutation variant of it (A10) with 15 sequences. This point mutation consisted of a deletion in motif 1 (5′-AGU CG-3′ instead of 5′-ACG UCG-3′).

To test for specificity in binding, 20 of the 36 sequences were subjected to a binding assay, testing their binding to homoeriodictyol, eriodictyol and naringenin. Candidates A1 and A10 clearly showed higher binding to homoeriodictyol than to eriodictyol or naringenin, implying specificity in binding (Figure S2B). Based on these results, we decided to further investigate the binding affinity and specificity of A1 using ITC. The measurements revealed a high binding affinity to homoeriodictyol with a KD of 2 µM while no binding to eriodictyol or naringenin were detected (Figure 4C). This clear discrimination in binding between homoeriodictyol and its close derivatives, demonstrated high specificity in binding of A1. Next, we created truncations and mutations of A1 to identify the binding relevant sections and gain further insights into its strucutre (Figure 4D). In a first step, we truncated A1 by shortening the P1 stem (T1) and removing the docking sequence used for immobilization during the SELEX (T2). When testing the truncations using ITC, A1T1 showed high affinity binding possessing a final KD of 1.83 ± 1.24 µM (N = 3, Figure S2D) while A1T2 completely lost binding to homoeriodictyol (Figure S2D). We then performed in-line probing to examine the structure of A1T1. The reactivity pattern supported the predicted secondary structure with the highest reactivity observed in unstructured areas like the loops L2 and L3 (Figures S3C and S3D). However, the P4/L4 region possessed a reactivity way higher than expected for a region structured through base pairing. This indicated a less stable or complete absence of structure in this section. Building on this information, we further modified A1T1 by removing position C20 from motif 1 (A1T1_V1), as found in candidate A10, changing C20 to an A (A1T1_V2), flipping the upper two base pairs of P2 (A1T1_V3) or changing the lower three base pairs of P3 to mutated motif 2 (A1T1_V4). We performed ITC to analyze the effects of these mutations on the binding behavior to homoeriodictyol. While mutations V1 and V2 maintained binding, V3 exhibited reduced binding and V4 showed complete loss of binding to homoeriodictyol (Figure S2E).

2.4 NGS analysis reveals the impact of selection parameters

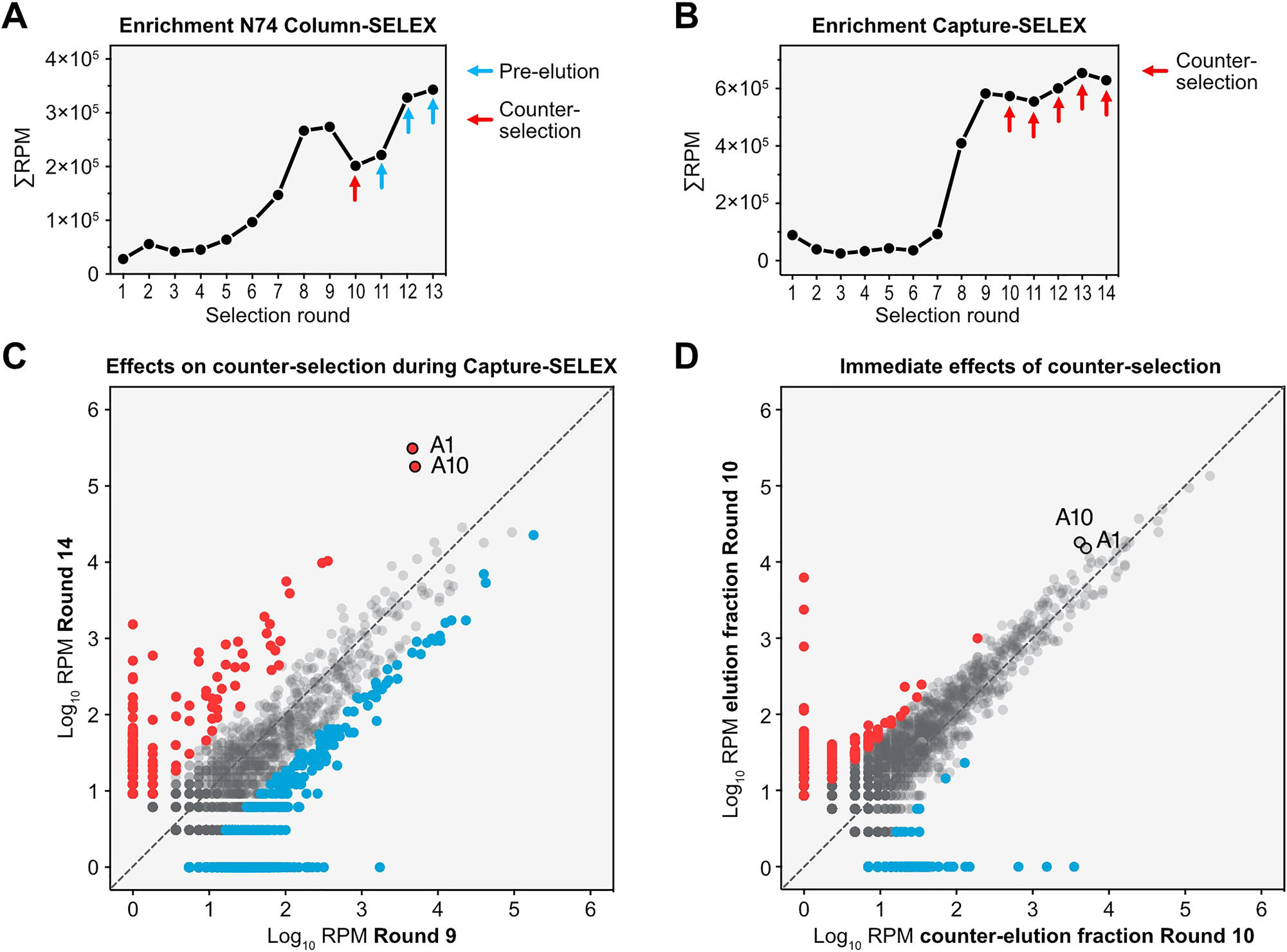

With the different outcomes of the three in vitro selection attempts, we asked how big the influence of counter-selection was on the outcome of the selection. To shed light on this, we sequenced all selection rounds of the column-based SELEX using the N74 pool and the Capture-SELEX and analyzed the abundance of sequences. By identifying the Top100 sequences of the last round of both selections and tracing them back through the selections, clear differences in progress between the selections became apparent. Over the course of the column-based SELEX, the tracked sequences slowly enriched until round 8 and 9 where they reached a first plateau of abundance (Figure 5A). Introduction of counter-selection led to an immediate decrease in abundance in round 10. Without the counter-selection from round 11 onwards, the abundance of the tracked sequences continuously increased until the end of selection in round 13. In rounds with a pre-elution step such effects were not noticeable. In comparison, the results of the Capture-SELEX showed a different picture of sequence behavior: in the first 7 rounds of selection no noticeable enrichment of the tracked sequences became apparent (Figure 5B). In round 8 the abundance of the tracked sequences suddenly increased, continuing to increase in round 9. With the introduction of counter elution in round 10, the abundance of the tracked sequences slightly decreased, further decreasing in round 11. In round 12 and 13 the abundance increased slightly and decreased again in round 14.

NGS revealing impact of counter-selection during SELEX. (A) Tracking of the Top100 enriched sequences found in the last round of the N74 column-based SELEX. The abundance of the sequences is shown in reads-per-million (RPM) over the rounds of selection. Indicated by arrows are the changed selection parameters, either counter-selection (red) or pre-elution (blue). A striking feature of the graph is the decrease in sequence abundance in reaction to the counter-selection and the fast recovery in the following two rounds. (B) Tracking of the Top100 enriched sequences found in the last round of the Capture-SELEX. The abundance of the sequences is shown in reads-per-million (RPM) over the rounds of selection and the rounds with a counter-selection step are indicated by red arrows. (C) Comparison of the abundance of sequences in RPM from round 9 and round 14 of the Capture-SELEX for illustration of long-term effects by the counter-selection. Sequences increasing ≥ 5-fold in reads between round 9 and 14 are accounted as enriching (red) while sequences decreasing ≥ 5-fold in reads are accounted as depleting (blue). Highlighted are the final candidates A1 and A10. (D) Comparison of the abundance of sequences in RPM in the elution fraction and counter-selected fraction during round 10.

We compared the abundance of individual sequences from round 14 with their abundance before the introduction of counter-selection in round 9 to gain insight into the pool behavior during the counter-selection (Figure 5C). From round 9 to round 14 1822 sequences decreased in abundance ≥ 5-fold (marked in blue, Figure 5C), 1217 sequences showed no change in abundance and 475 sequences enriched ≥ 5-fold (marked in red, Figure 5C). The changes in abundance appeared for sequences with all different RPM values but showed the strongest effects on sequences with low abundance. Strikingly, the two sequences with the highest abundance in round 14 and a clear enrichment from round 9 to round 14 were the candidates A1 and A10. To gain insight into the immediate effects of counter-selection, we compared the abundance of sequences in the eluted fraction and the counter-selection fraction from round 10 (Figure 5D). In this comparison, 756 sequences showed a ≥ 5-fold higher abundance in the elution fraction, 1709 sequences showed no difference, and 561 sequences showed a ≥ 5-fold higher abundance in the counter-selection fraction. The final candidates A1 and A10 did not possess a 5-fold difference between the two fractions. The most effects appeared in sequences with low read counts in both fractions (<102 RPM). These results indicate the strongest, immediate effects of counter-selection on sequences with low abundance while more abundant sequences seem to be less affected. In turn, the difference between rounds 9 and 14 hint towards a change in high abundant sequences over multiple rounds that include a counter-selection, as performed between round 9 and 14.

3 Discussion

After three selection approaches with changing setups, we identified with A1 a RNA aptamer with high binding specificity to homoeriodioctyol, discriminating between close derivatives. Thereby, the process over three different selection approaches provided valuable insights into the SELEX process. First, similarities between the two aptamer candidates K5 and H2 revealed two shared motifs. Based on their independent appearance in two selections, the co-occurrence of the motifs during the second column-based selection, the results of mutational studies on H2 and the successful selection of the aptamer A1 from a pool including these two motifs, strongly indicates their involvement in the binding of homoeriodictyol. Furthermore, during mutational studies on the aptamers H2 and A1, alteration or removal of the two identified motifs led to loss of binding to homeriodictyol, further supporting their role in target binding. However, the motifs were found in the aptamers K5 and H2 which could not discriminate between homoeriodictyol, eriodictyol and naringenin, as well as in A1 which was able to discriminate between these close derivatives. This indicates that despite their involvement in binding, the two motifs seem not relevant for binding specificity. The precise factors causing the binding specificity of A1 remains unknown so far, though it can be hypothesized that either the relative positioning of the motifs or a third part of the aptamer could have led to the binding specificity. Interesting in this context is the loss of binding behavior of A1T2 caused by removal of the L4-P4 region, hinting towards a role in target binding. This could, for example, be a third part of the aptamer allowing for binding affinity and specificity of A1 in cooperation with the motifs 1 and 2.

Second, the outcome and progress of the three selections gave insight into the importance of selection method and parameters. While the first two column-based attempts failed to deliver an aptamer specific in binding to homoeriodictyol, the Capture-SELEX approach resulted with A1 in an aptamer with high binding specificity and good affinity. Having a ligand that made coupling to the epoxy-activated sepharose difficult due to instability at high pH values, highlights a big advantage of Capture-SELEX where the ligand does not have to be immobilized. To have the ligand free in solution during the selection step might have facilitated the specificity of the resulting aptamer since all functional groups and sites of the target molecule were accessible for the aptamer. Nevertheless, the success should not be merely attributed to the selection mode of the Capture-SELEX. When comparing the parameters of the three attempts, it becomes apparent that the selection stringency was increased with every new approach. While in the first selection only two rounds included counter-selection (6 and 7) and the last three rounds included specific elution while the wash steps were kept constant, the second selection already included specific elution from round two on, increase in wash steps, one round with counter-elution and an introduction of pre-elution steps in the last three rounds. This increase in selection stringency seems to have facilitated the selection of target binding sequences as indicated by the lower diversity of sequences found in the sequencing results of the second selection compared to the first. With the third selection attempt not only the selection method was changed, but the stringency was further increased. Having a specific elution every round and counter-selection with eriodictyol and naringenin through the last five rounds of selection might have played a decisive role in the selection of A1. This is further supported by the NGS analysis results, as the impact of counter-selection in the second column-based SELEX seemed to have impacted the pool composition for only one round (Figure 5A) while the consistent counter-selection introduced in the Capture-SELEX had a lasting effect on the pool composition (Figure 5B). Furthermore, the detailed comparison between rounds 9 and 14 and the comparison of the elution fraction with the counter-selection fraction of round 10 of the Capture-SELEX support the importance of consistent counter-selection for high specificity of the resulting aptamers. The little difference in abundance of sequences between elution and counter-selection fraction indicates a minor impact on pool composition by single counter-selection step. The stronger differences in pool composition after 5 rounds including counter-selection, suggest that a consistent counter-selection is necessary for permanent changes in the pool. This is highlighted by the abundance changes of A1 and A10 between rounds 9 and 14 and in comparison, to their abundance in the fractions of round 10.

Overall, we succeeded in selecting a highly specific RNA aptamer binding homoeriodictyol with good affinity while we also gained valuable insights into the parameters shaping the selection process. The outcome of the selections and our NGS analysis strongly suggest the importance of consistent high stringency for the successful selection of specific aptamers. With A1T1, we provide an RNA aptamer with high binding specificity for homoeriodictyol, offering a good basis for applications like biosensor engineering utilizing this new aptamer (Kramat et al. 2024).

4 Materials and methods

Chemicals

Homoeriodictyol, eriodictyol and naringenin were purchased by Extrasynthese (Genay, France). All other chemicals and reagents were acquired by Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, USA), if not stated otherwise. The flavanone stock solutions were prepared as 50 mM in DMSO. The final concentration of DMSO for the experiments never exceeded 0.2 %.

4.1 Pool design and preparation

For the first column-based SELEX approach, a pool with a randomized region of 64 nucleotides was chosen. For amplification of the N64 pool, the flanking constant regions were used (5′ constant: 5′-GGG AGA CGC AAC TGA ATG AA-3′ / 3′ constant: 5′-TCC GTA ACT AGT CGC GTC AC-3′) for the binding of the oligonucleotides B8 (5′-ATG TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGA GAC GCA ACT GAA TGA A-3′), adding the T7 promoter sequence, and RQ (5′-GTG ACG CGA CTA GTT ACG GA-3′). For the second column-based SELEX, a N74 pool was used which consists of a 74-nt long randomized sequence flanked by constant regions (5′ constant: 5′-GGA GCT CAG CCT TCA CTG C-3’ / 3′ constant: 5′-GGC ACC ACG GTC GGA TCC AC-3′) for amplification using the oligonucleotides Pool_fwd (5′-TCT AAT ACG ACT CAC TAT AGG AGC TCA GCC TTC ACT GC-3′) and Pool_rev (5′-GTG GAT CCG ACC GTG GTG CC-3′) (Famulok 1994). In case of Capture-SELEX, a doped pool based on the design of the Capture-SELEX pool containing the two motives found in the column-based SELEX was used (Boussebayle et al. 2019). The pool consisted of the two motives, sections with randomized nucleotides and the docking sequence (Figure 4A). The docking sequence consists of a 13 nt long sequence (5′-CUA CUG GCU UCU A-3′), necessary for coupling the RNA pool to the capture-oligonucleotide (5′-TAG AAG CCA GTA G [BtnTg]-3′) (Figure 4A). Both ends of the pool contained constant regions, necessary for the amplification of the pool (5′ constant: 5′-GGG CAA CTC CAA GCT AGA TCT ACC GGT-3′ / 3′ constant: 5′-AGT GAA AAG TTC TTC TCC TTT GCT AGC CAT TTT-3′). The pool was amplified using the oligonucleotides Pool_fwd_capSEL (5′-CCA AGT AAT ACG ACT CAC TAT AGG GCA ACT CCA AGC TAG ATC TAC CGG T – 3′) and Pool_rev_capSEL (5′-AGT GAA AAG TTC TTC TCC TTT GCT AGC CAT TTT-3′). Amplification and transcription were performed as previously described (Groher et al. 2018).

4.2 Immobilization of homoeriodictyol to epoxide resin

For the column-based SELEX, homoeriodictyol was immobilized on Profinity™ Epoxide Resin (BioRad). Due to the sensibility of homoeriodictyol at high pH values, the immobilization was only feasible via a linker (1,4-diamonobutane) and a subsequent Mannich reaction (Figure S1A). First, 0.5 g of resin were incubated with 5 ml of 0.02 M diaminobutane (Sigma-Aldrich) in buffer at pH 13 (132 mM NaOH, 50 mM KCl), for 3 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. After the incubation, the resin was settled in order to remove the supernatant, washed two times with buffer pH 13 and collected on a fritted glass. The unreacted diaminobutane was removed by three alternating wash cycles of 100 mL of buffer pH 4 (17.5 M acetic acid, 5 M NaCl) and buffer pH 8 (1 M K2HPO4, 1 M KH2PO4, 5 M NaCl). Subsequently, the resin was equilibrated with coupling buffer pH 4.7 (50 mM MES, 75 mM NaCl, 50 % Ethanol) to start the Mannich reaction. To couple homoeriodictyol to the column, 4 mL of 3 mM homoeriodictyol solution and 200 µl formaldehyde (37 % solution) were added to 2 mL resin. The same was done for eriodictyol-coupled resin used for counter-selection. For pre-selection columns (without a coupled ligand), the resin was incubated with 3 mM DMSO in coupling buffer. The Mannich reaction was incubated at 37 °C, 70 rpm for 66 h. Coupling of homoeriodictyol was confirmed by measuring the absorbance at 290 nm. For this, a standard curve measurement of homoeriodictyol in the binding buffer (BB, described below) was performed (Figure S1B).

4.3 In vitro selection of the RNA aptamers

For all in vitro selections, eluted RNA was ethanol-precipitated in the presence of 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 6.5) and 15 µg GlycoBlue as coprecipitant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). After two washing steps with 70 % ethanol, the pellet was air-dried and dissolved in 50 µL MQ-H2O, reverse transcribed and amplified (RT-PCR) as previously described (Groher et al. 2018). For the following round, 10 µL of the RT-PCR were mixed with 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM DTT, 2.5 mM NTPs (each), 15 mM MgCl2, T7 RNA polymerase (home made), 40 U ribonuclease inhibitor (moloX) and 33 nM 32P-α-UTP (Hartmann Analytics) in a total volume of 100 µl. Transcription was carried out overnight at 37 °C and was afterwards ethanol-precipitated in the presence of 2.5 M ammonium acetate and washed twice with 70 % ethanol. The pellet was then dissolved in 50 µL MQ-H2O and used for subsequent in vitro selection.

4.3.1 Column-based SELEX

The column-based SELEX was started with 2 nmoles RNA mixed with 250 kcpm of radioactive-labeled RNA in water. The RNA was folded by heating to 95 °C for 5 min followed by snap cooling on ice for 5 min. After this folding step, yeast tRNA was added to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL and the volume was adjusted to 1 column volume (CV) of resin (200 µL) with 1x binding buffer (BB, 40 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 125 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 % DMSO). To reduce column-binding RNAs a pre-selection step was performed in round 1–3. For this, the RNA pool was first incubated with a column without a coupled ligand. Unbound RNAs were directly added to the 1 CV homoeriodictyol-coupled resin and incubated for 30 min at RT (room temperature). After initial incubation, the column was washed with 10, 20 or 25 CV BB and bound RNAs were eluted with either 4 CV 20 mM EDTA (N64 pool: round 1–8, N74 pool: round 1) or with 4 CV 1 mM homoeriodictyol in BB (N64 pool: 9–11, N74 pool: round 2–13). RNA amounts throughout the selection process were calculated relative to the input in percent based on radioactive measurements. RNA recovered after washing the column with homoeriodictyol was accounted as specifically bound, while the signal of the last 4 CV of washing before the elution was referred to as background. In rounds 6 and 7 of the first column-based SELEX approach and round 10 of the second SELEX approach (N74 pool), a counter-selection step with an eriodictyol-coupled column was performed before the selection step with homoeriodictyol. In this case, folded RNA was first incubated with an eriodictyol-coupled column and unbound RNAs were directly added to the homoeriodictyol-coupled column and incubated as usual for 30 min at RT.

4.3.2 Capture SELEX

Capture-SELEX was performed as previously described in Boussebayle et al. (2019) with minor modifications as described below (Boussebayle et al. 2019).

In each round, 100 kCPM 32P-body-labeled RNA were used for the selection. Each round was performed with 150 µL Streptavidin-Tag magnetic beads and 6 nmol of capture-oligonucleotide. During the selection, the RNA was specifically eluted with 1 mM (round 1–10) or 100 µM homoeriodictyol (round 11–15) in 1x Capture-SELEX buffer (CSB) by incubating for 5 min at room temperature. A counter elution step with 1 mM eriodictyol and 1 mM naringenin in 1x CSB was added during round 10–15. The radioactive signal of the last washing step was defined as background signal to be compared with the eluted fraction.

4.4 Identification of candidates by sequencing

For the identification of single candidates, the DNA pool of a SELEX round was cloned into the pJet plasmid (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and NEB10β were transformed with the plasmid carrying the pool sequences and grown on LB agar plates with ampicillin as selection marker. To obtain plasmids for sequencing, individual colonies were picked to inoculate LB with ampicillin, grown over night and the plasmid was isolated using the Wizard Plus SV Miniprep kit (Promega, Walldorf, Germany). The isolated plasmids were sent for Sanger-sequencing (Microsynth AG, Balgach, Switzerland) using an added primer (pJet-f: 5′-CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG AGA GCG GC-3′).

4.5 RNA synthesis

In vitro transcription was performed from PCR-generated templates. In all cases, between one or three 5′-terminal guanine residues were added to facilitate in vitro transcription of the T7 RNA polymerase. For every single aptamer, two oligonucleotides were designed with an overlap of 30 bp and amplified using Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase following the supplier’s instructions Supplementary Table SXX. The in vitro transcription was carried out as previously described (Groher and Suess 2016). The RNA was gel purified, and molarity was determined by spectrophotometric measurement using NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA).

4.6 Radioactive labeling of RNA

For binding assays and in-line probing, the RNA was end-labeled with 32P-ATP. Two nmols of RNA pool were dephosphorylated using the enzyme antarctic phosphatase (5 U/µl) following the manufacturer’s specifications. Subsequently, 0.5 nmol of dephosphorylated RNA were end-labeled with 32P-ɣ-ATP (Hartmann Analytics) using T4 Polynucleotide kinase (10 U/µl). After incubating 2 h at 37 °C, the RNA was precipitated by ammonium-acetate and ethanol. The precipitated RNA was dissolved in MQ-H2O. The radioactivity was then measured in a Scintillation Counter (Tri-Carb 2800TR, PerkinElmer, Waltham, USA).

4.7 Binding assays

The binding capacity of aptamer candidates to their target ligand was tested using a column binding assays. RNA was treated as described for the column-based in vitro selection of RNA aptamers. Between 100 and 200 kCPM of body-labeled RNA were folded as described above and loaded onto a homoeriodictyol-coupled column. After incubation for 30 min at RT, the columns were washed with 10 CV with of 1x of the corresponding SELEX buffer and bound RNA was specifically eluted with 6 CV of 1 mM homoeriodictyol. The amount of radioactive signal from all 6 CV of eluted RNA was added and normalized to the input to make a conclusion about the binding of the tested aptamer candidate.

4.8 In-line probing experiments

In-line probing was performed to probe the structure of RNA aptamer candidates. For size comparison, specifically fragmented samples of the aptamers were generated. The RNA was dephosphorylated and 5′-32P-labeled as described above. To generate control reactions, it was subjected to alkaline hydroxylation by incubation for 3 min at 96 °C in 50 mM Na2CO3 (pH 9.0) or incubated for 3 min at 55 °C with 20 U RNase T1 at denaturing conditions to identify guanine positions. For in-line probing, 5′-32P-labeled RNA was incubated for at least 68 h at 22 °C in in-line reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.3, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl). Samples from all three reactions (alkaline hydroxylation, RNase T1 or in-line) were ethanol precipitated, and the pellet was dissolved in 5 M urea. The RNA fragments were separated by size through a denaturating polyacrylamide gel (10 %, 8 M urea) electrophoresis, dried at 80 °C for 1 h and analyzed using phosphorimaging (GE Healthcare, Chicago, USA).

4.9 Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC experiments were carried out in a MicroCal PEAQ-ITC (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, United Kingdom) with the sample cell (200 µl) containing 20 µM RNA and 400 µM homoeriodictyol solution in 1x of the corresponding SELEX-buffer in the injector syringe (40 µl). After thermal equilibration at 25 °C, an initial 150 s delay and one initial 0.4 µl injection were carried out. Then, 19 serial injections of 2.0 μl at intervals of 150 s and at a stirring speed of 750 rpm were performed. Raw data were recorded as power (µcal s−1) over time (min). The heat associated with each titration peak was integrated and plotted against the corresponding molar ratio of homoeriodictyol and RNA. The dissociation constant (KD) was extracted from a curve fit of the corrected data by use of the one-site binding model provided by the MicroCal PEAQ-ITC Analysis Software 1.1.0.1262. Final KD values with standard deviation were obtained from three independent measurements.

4.10 Next-generation sequencing analysis

In vitro selections were analyzed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) using Illumina sequencing reactions (GenXPro GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany). For this, barcodes to multiplex selection rounds were attached by PCR using a different set of oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table S4 and S5). They introduced a 4-mer or 6-mer barcode to assign each sequence to the specific round from column-based SELEX or Capture-SELEX, respectively. After amplification, the samples were gel-purified (Zymoclean Gel DNA Recovery Kit, Zymo Research, Irvine, USA) and mixed in equimolar amounts. All data was analyzed as previously described (Groher et al. 2018).

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: SU402/11-1

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Britta Schreiber for excellent technical support. The authors would like to thank Francesca Arabica for her inspiration and motivation.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: J.H. data analysis, manuscript writing; C.B.B. project design, performing and supervision of experiments; A.W.M. and M.M.R. performing experiments; F.G. NGS analysis; B.S. project conception, manuscript writing and revision, funding acquisition.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The work was financially supported by EU FP7 Promys and the DFG (SU402/11-1).

-

Data availability: All data included in the manuscript, NGS data will be uploaded for public access. <authors: indicate URL/give source information for access>.

References

Amano, R., Namekata, M., Horiuchi, M., Saso, M., Yanagisawa, T., Tanaka, Y., Ghani, F.I., Yamamoto, M., and Sakamoto, T. (2021). Specific inhibition of FGF5-induced cell proliferation by RNA aptamers. Sci. Rep. 11: 2976, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82350-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Beltrán, L.R., Sterneder, S., Hasural, A., Paetz, S., Hans, J., Ley, J.P., and Somoza, V. (2022). Reducing the bitter taste of pharmaceuticals using cell-based identification of bitter-masking compounds. Pharmaceuticals 15: 317, https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15030317.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Berens, C., Thain, A., and Schroeder, R. (2001). A tetracycline-binding RNA aptamer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 9: 2549–2556, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00063-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Boussebayle, A., Groher, F., and Suess, B. (2019). RNA-based Capture-SELEX for the selection of small molecule-binding aptamers. Methods 161: 10–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.04.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bruno, J.G. (1997). In vitro selection of DNA to chloroaromatics using magnetic microbead-based affinity separation and fluorescence detection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234: 117–120, https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1997.6517.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ellington, A.D. and Szostak, J.W. (1990). In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346: 818–822, https://doi.org/10.1038/346818a0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Famulok, M. (1994). Molecular recognition of amino acids by RNA-Aptamers: an L-Citrulline binding RNA motif and its evolution into an L-Arginine binder. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116: 1698–1706, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00084a010.Search in Google Scholar

Groher, F., Bofill-Bosch, C., Schneider, C., Braun, J., Jager, S., Geißler, K., Hamacher, K., and Suess, B. (2018). Riboswitching with ciprofloxacin—development and characterization of a novel RNA regulator. Nucleic Acids Res. 46: gkx1319, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1319.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Groher, F. and Suess, B. (2016). In vitro selection of antibiotic-binding aptamers. Methods 106: 42–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.05.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Homann, M. and Göringer, H.U. (1999). Combinatorial selection of high affinity RNA ligands to live African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 2006–2014, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/27.9.2006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Hunsicker, A., Steber, M., Mayer, G., Meitert, J., Klotzsche, M., Blind, M., Hillen, W., Berens, C., and Suess, B. (2009). An RNA aptamer that induces transcription. Chem. Biol. 16: 173–180, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.12.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Jang, S., Jang, S., Xiu, Y., Kang, T.J., Lee, S.-H., Koffas, M.A.G., and Jung, G.Y. (2017). Development of artificial riboswitches for monitoring of naringenin In Vivo. ACS Synth. Biol. 6: 2077–2085, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.7b00128.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Khan, M.K., Zill-E-Huma, and Dangles, O. (2014). A comprehensive review on flavanones, the major citrus polyphenols. J. Food Compos. Anal. 33: 85–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2013.11.004.Search in Google Scholar

Kramat, J., Kraus, L., Gunawan, V.J., Smyej, E., Froehlich, P., Weber, T.E., Spiehl, D., Koeppl, H., Blaeser, A., and Suess, B. (2024). Sensing levofloxacin with an RNA aptamer as a bioreceptor. Biosensors 14: 56, https://doi.org/10.3390/bios14010056.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kraus, L., Duchardt-Ferner, E., Bräuchle, E., Fürbacher, S., Kelvin, D., Marx, H., Boussebayle, A., Maurer, L.-M., Bofill-Bosch, C., Wöhnert, J., et al.. (2023). Development of a novel tobramycin dependent riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res. 51: 11375–11385, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad767.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ley, J.P., Krammer, G., Reinders, G., Gatfield, I.L., and Bertram, H.-J. (2005). Evaluation of bitter masking flavanones from Herba Santa (Eriodictyon californicum (H. & A.) Torr., Hydrophyllaceae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 53: 6061–6066, https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0505170.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Liu, Q., Liu, L., Zhou, J., Shin, H., Chen, R.R., Madzak, C., Li, J., Du, G., and Chen, J. (2013). Biosynthesis of homoeriodictyol from eriodictyol by flavone 3′-O-methyltransferase from recombinant Yarrowia lioplytica: heterologous expression, biochemical characterization, and optimal transformation. J. Biotechnol. 167: 472–478, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.07.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lorenz, R., Bernhart, S.H., Siederdissen, C.H.zu, Tafer, H., Flamm, C., Stadler, P.F., and Hofacker, I.L. (2011). ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 6: 26, https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-7188-6-26.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Morris, K.N., Jensen, K.B., Julin, C.M., Weil, M., and Gold, L. (1998). High affinity ligands from in vitro selection: complex targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 2902–2907, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.6.2902.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ohuchi, S. and Suess, B. (2017). An inhibitory RNA aptamer against the lambda cI repressor shows transcriptional activator activity in vivo. FEBS Lett. 591: 1429–1436, https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.12653.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Pandey, R.P., Parajuli, P., Koffas, M.A.G., and Sohng, J.K. (2016). Microbial production of natural and non-natural flavonoids: pathway engineering, directed evolution and systems/synthetic biology. Biotechnol. Adv. 34: 634–662, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.02.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Shi, J., Feng, D., and Li, Y. (2017). Biosensors in fermentation applications. Ferment. Process. 1: 145–157, https://doi.org/10.5772/65077.Search in Google Scholar

Stoltenburg, R., Nikolaus, N., and Strehlitz, B. (2012). Capture-SELEX: selection of DNA aptamers for aminoglycoside antibiotics. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2012: 415697, https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/415697.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Thavarajah, W., Silverman, A.D., Verosloff, M.S., Kelley-Loughnane, N., Jewett, M.C., and Lucks, J.B. (2020). Point-of-Use detection of environmental fluoride via a cell-free riboswitch-based biosensor. ACS Synth. Biol. 9: 10–18, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.9b00347.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tuerk, C. and Gold, L. (1990). Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249: 505–510, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2200121.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Valero, J., Civit, L., Dupont, D.M., Selnihhin, D., Reinert, L.S., Idorn, M., Israels, B.A., Bednarz, A.M., Bus, C., Asbach, B., et al.. (2021). A serum-stable RNA aptamer specific for SARS-CoV-2 neutralizes viral entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118: e2112942118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2112942118.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Vockenhuber, M.-P., Hoetzel, J., Maurer, L.-M., Fröhlich, P., Weiler, S., Muller, Y.A., Koeppl, H., and Suess, B. (2023). A novel RNA aptamer as synthetic inducer of DasR controlled transcription. ACS Synth. Biol. 13: 319–327, https://doi.org/10.1021/acssynbio.3c00553.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Wallis, M.G., Ahsen, U.von, Schroeder, R., and Famulok, M. (1995). A novel RNA motif for neomycin recognition. Chem. Biol. 2: 543–552, https://doi.org/10.1016/1074-5521(95)90188-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Yildirim, N., Long, F., Gao, C., He, M., Shi, H.-C., and Gu, A.Z. (2012). Aptamer-Based optical biosensor for rapid and sensitive detection of 17β-Estradiol in water samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46: 3288–3294, https://doi.org/10.1021/es203624w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

You, M., Litke, J.L., and Jaffrey, S.R. (2015). Imaging metabolite dynamics in living cells using a Spinach-based riboswitch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: E2756–E2765, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1504354112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2025-0118).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Meeting Report

- The 76th Mosbacher Colloquium: AI-driven (r)evolution in structural biology and protein design

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Genes and Nucleic Acids

- Triple SELEX approach for the selection of a highly specific RNA aptamer binding homoeriodictyol

- Protein Structure and Function

- New polyamine oxidases from Ogataea parapolymorpha DL-1: expanding view on non-conventional yeast polyamine catabolism

- Molecular Medicine

- Formulation of pH-responsive nanoplexes based on an antimicrobial peptide and sodium alginate for targeted delivery of vancomycin against resistant bacteria

- Cell Biology and Signaling

- TBK1 alleviates triptolide-induced nephrotoxic injury by up-regulating mitophagy in HK2 cells

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Meeting Report

- The 76th Mosbacher Colloquium: AI-driven (r)evolution in structural biology and protein design

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Genes and Nucleic Acids

- Triple SELEX approach for the selection of a highly specific RNA aptamer binding homoeriodictyol

- Protein Structure and Function

- New polyamine oxidases from Ogataea parapolymorpha DL-1: expanding view on non-conventional yeast polyamine catabolism

- Molecular Medicine

- Formulation of pH-responsive nanoplexes based on an antimicrobial peptide and sodium alginate for targeted delivery of vancomycin against resistant bacteria

- Cell Biology and Signaling

- TBK1 alleviates triptolide-induced nephrotoxic injury by up-regulating mitophagy in HK2 cells