Abstract

Kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) is one of 15 members of the tissue kallikrein family and is primarily expressed in the skin epidermis. The activity of KLK7 is tightly regulated by multiple stages of maturation and reversible inhibition, similar to several other extracellular proteases. In this work, we used protease-specific inhibitors and active site variants to show that KLK7 undergoes autolysis at two separate sites in the 170 and 99 loops (chymotrypsinogen numbering), resulting in a loss of enzymatic activity. A protein BLAST search using the autolyzed KLK7 loop sequences identified mast cell chymase as a potential KLK7 substrate. Indeed, KLK7 cleaves chymase resulting in a concomitant loss of activity. We further demonstrate that KLK7 can hydrolyze other mast cell proteases as well as several cytokines. These cytokines belong mainly to the interferon and IL-10 families including IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, IL-28A/IFN-λ2, IL-20, IL-22, and IL-27. This is the first study to identify a possible molecular interaction link between KLK7 and mast cell proteases and cytokines. Although the precise biological implications of these findings are unclear, this study extends our understanding of the delicate balance of proteolytic regulation of enzyme activity that maintains physiological homeostasis, and facilitates further biological investigations.

1 Introduction

Extracellular proteases play an important role in mammalian physiology. The activity of these proteases is tightly regulated by latency controls, localization, pH and protein inhibitors. An imbalance in their activity has been implicated in cancer progression, immune disorders, vascular diseases, gastrointestinal pathology, respiratory conditions and more (Cudic and Fields 2009). A greater understanding of the factors influencing activity as well as identifying substrates that these proteases hydrolyze is critical in devising strategies for therapeutic intervention.

Kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) is one such extracellular serine protease that belongs to the kallikrein family of enzymes (Yousef et al. 2000). The kallikrein family consists of 15 members (KLK1-KLK15), which are secreted, closely related in sequence and structure, and increasingly recognized as important enzymes in various pathophysiological processes and thus of therapeutic interest as well (Diamandis and Yousef 2001; Kalinska et al. 2016; Lundwall et al. 2006; Prassas et al. 2015). KLK7, also referred to as stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme, is the most abundant chymotrypsin-like protease present in the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of skin epidermis, and has been shown to play an important role in skin biology (Komatsu et al. 2006). KLK7, along with other skin proteases, cleaves proteins that constitute the corneodesmosomes, the tight junction protein assemblies that hold adjacent bound corneocytes together, thereby facilitating their separation that ultimately results in skin desquamation (Milstone 2004). Among corneodesmosomal proteins, KLK7 specifically hydrolyzes cadherins like desmocollin 1 (DSC1), as well as corneodesmosin (CDSN).

In addition to skin tissue, KLK7 is also primarily expressed in brain, kidney, proximal digestive tract, tonsil, and female tissues (Clements et al. 2004; Uhlen et al. 2015) (Data from v23.0 of www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000169035-KLK7/tissue). Mis-regulation of KLK7 expression and activity is implicated in several pathological conditions. Studies have shown KLK7 to be involved in multiple skin diseases involving pathological keratinization, dermatitis, and psoriasis (Igawa et al. 2017; Kasparek et al. 2017; Kishibe 2019). KLK7 is also involved in tumor metastasis, with high expression profile in ovarian carcinomas, and enhancement of cell invasion in pancreatic cancer by shedding E-cadherins (Dorn et al. 2014; Johnson et al. 2007; Mo et al. 2010; Raju et al. 2016; Talieri et al. 2009; Walker et al. 2014). KLK7 is capable of hydrolyzing insulin at similar sites compared to the major insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), and likely plays a role in regulating the levels of insulin either locally in the pancreas or in plasma, or both (Heiker et al. 2013). KLK7 is also capable of hydrolyzing Aβ-amyloid fibrils in vitro, and has been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia (Diamandis et al. 2004; Shropshire et al. 2014).

The enzymatic activity of KLK7 is tightly regulated at the multiple stages of the protease maturation process. It is expressed as an inactive 253 amino acid pre-proenzyme in the cell cytoplasm (Hansson et al. 1994). The first 22 amino acid residues form the signal peptide, and are cleaved at the time of protein secretion from the cell. The proenzyme or zymogen is then converted into the active form as a single domain in the extracellular space by the cleavage of the 7-mer N-terminal propeptide by proteases with trypsin-like specificity. Kallikrein-related peptidase 5 (KLK5) and matriptase are among the known activators, especially in the skin tissue (Brattsand et al. 2005; Sales et al. 2010). The KLK7 propeptide lacks a cysteine and thus does not form a disulfide bond with the mature protease that is sometimes found in serine proteases. KLK7 has chymotryptic-like specificity due to Asn189 at the bottom of the S1 specificity pocket (chymotrypsinogen numbering is used throughout; Hartley 1970).

We embarked on our biochemical characterization of KLK7 as one of the biological targets in treating Netherton syndrome and atopic dermatitis with an anti-KLK5/KLK7 dual inhibitory antibody (Chavarria-Smith et al. 2022). However, when we initiated efforts to obtain purified recombinant KLK7 heterologously expressed in transient mammalian cell cultures, we observed partial proteolysis of the purified enzyme, which occurred exclusively during purification. In this study, we have undertaken an extensive biochemical characterization of the observed autolysis of KLK7, probed its scope using bioinformatics and discovered previously unidentified substrates that may have biological relevance.

2 Results

2.1 Purified KLK7 undergoes pH-dependent autolysis

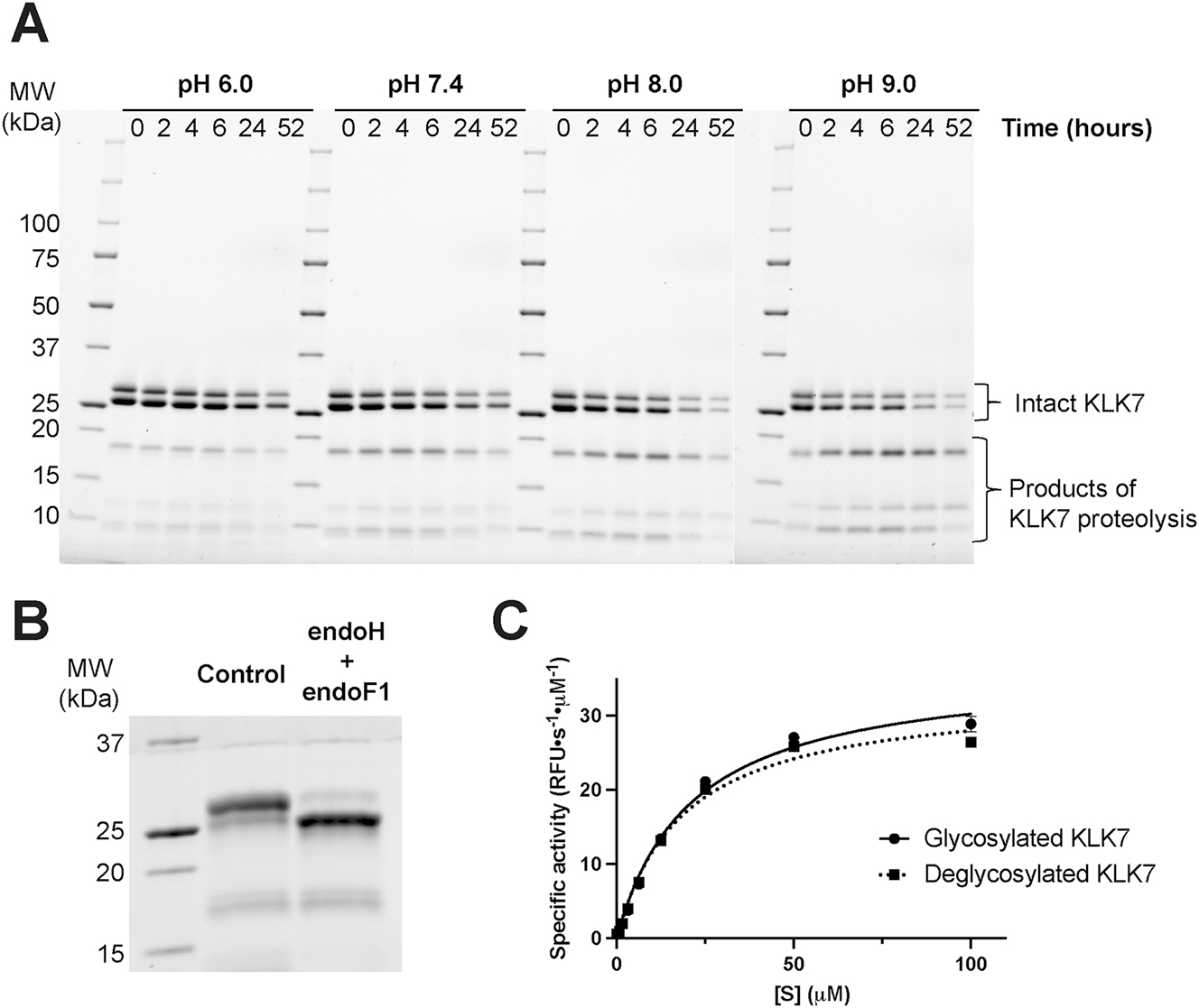

Inactive KLK7 zymogen containing an enterokinase (EK) cleavable N-terminal His6-tag was expressed and purified and then treated with EK to generate active KLK7 protease. This was then purified and buffer-exchanged into PBS (pH ∼7.4) using size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The activated KLK7 thus obtained, underwent detectable autolysis if stored at room temperature for >4 h, or at 4 °C overnight whereas the inactive His6-tagged zymogen did not (Supplementary Figure S1). We show that the observed proteolysis is indeed autolysis below. Autolysis of active KLK7, which runs as a double band due to glycosylation proceeded at different rates at different pH values (Figure 1). In general, autolysis of KLK7 was slower at acidic pH and faster at alkaline pH; pH 8 and 9 were optimal. Intact KLK7, which runs as two bands due to glycosylation (Figure 1B), diminished over time with a concomitant initial increase and then decrease of lower molecular weight bands, suggesting KLK7 autolysis. Kinetic constants for both glycosylated and deglycosylated wild-type KLK7 were similar (Vmax = 36.6 ± 2.5 and 33.1 ± 2.1 RFU s−1 µM−1 and KM = 21.2 ± 4.0 and 18.6 ± 3.6 µM, respectively), indicating that enzymatic activity was independent of the glycosylation state (Figure 1C). Characterization of the nature of glycosylation using in-solution MASS ID indicated that recombinant KLK7 expressed in Expi293 cells is N-glycosylated at Asn239 with Hexose4-5GlcNAc2 and Hexose5GlcNAc3 on the Asn239 residue within the NDT sequon. We did not observe any O-linked glycosylation at possible sites Ser139 or Thr144. Despite proceeding faster at alkaline pH, we never observed complete depletion of the intact KLK7. The temperature and pH-activity profile of KLK7 autolysis was exploited to design the purification protocol adopted in this study for obtaining intact unproteolyzed active KLK7. In brief, EK-catalyzed cleavage of the N-terminal His6-tag was carried out at 4 °C overnight using 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, and ensuring that the concentration of the zymogen was at or below 1 mg/mL. Subsequent SEC was performed using a mildly acidic buffer (20 mM MES pH 6.0, 200 mM NaCl). The concentration of MES buffer (20 mM) was kept at an optimal (minimal) level to facilitate a buffer change in the subsequent step, preferably by simple dilution, during biochemical studies.

Human KLK7 undergoes pH-dependent proteolysis. (A) Active purified KLK7 (100 μg per sample, ∼5 mg/mL) was incubated at 37 °C for 2 days at various pH values. Aliquots corresponding to various time points were quenched with reducing Laemmli buffer, followed by heat denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Intact KLK7, which runs as two bands due to glycosylation (B), diminished over time with a concomitant initial increase and then decrease of lower molecular weight bands, suggesting KLK7 autolysis. The rate of putative autolysis was lowest at pH 6.0 and increased with increasing pH. (B) Wild-type hKLK7 was incubated with (deglycosylated hKLK7) and without (control or glycosylated hKLK7) endoH and endoF1 deglycosylases in 100 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl at 4 °C overnight. Each deglycosylase was in 1:100 w/w ratio compared to hKLK7. (C) The hKLK7 enzymes from B were assayed to determine the effect of deglycosylation on activity. Values derived from fitting the data to the Michaelis–Menten equation are the sample means ± margin of error for the 95 % confidence interval.

2.2 Probing KLK7 autolysis with inhibitors and active site variants

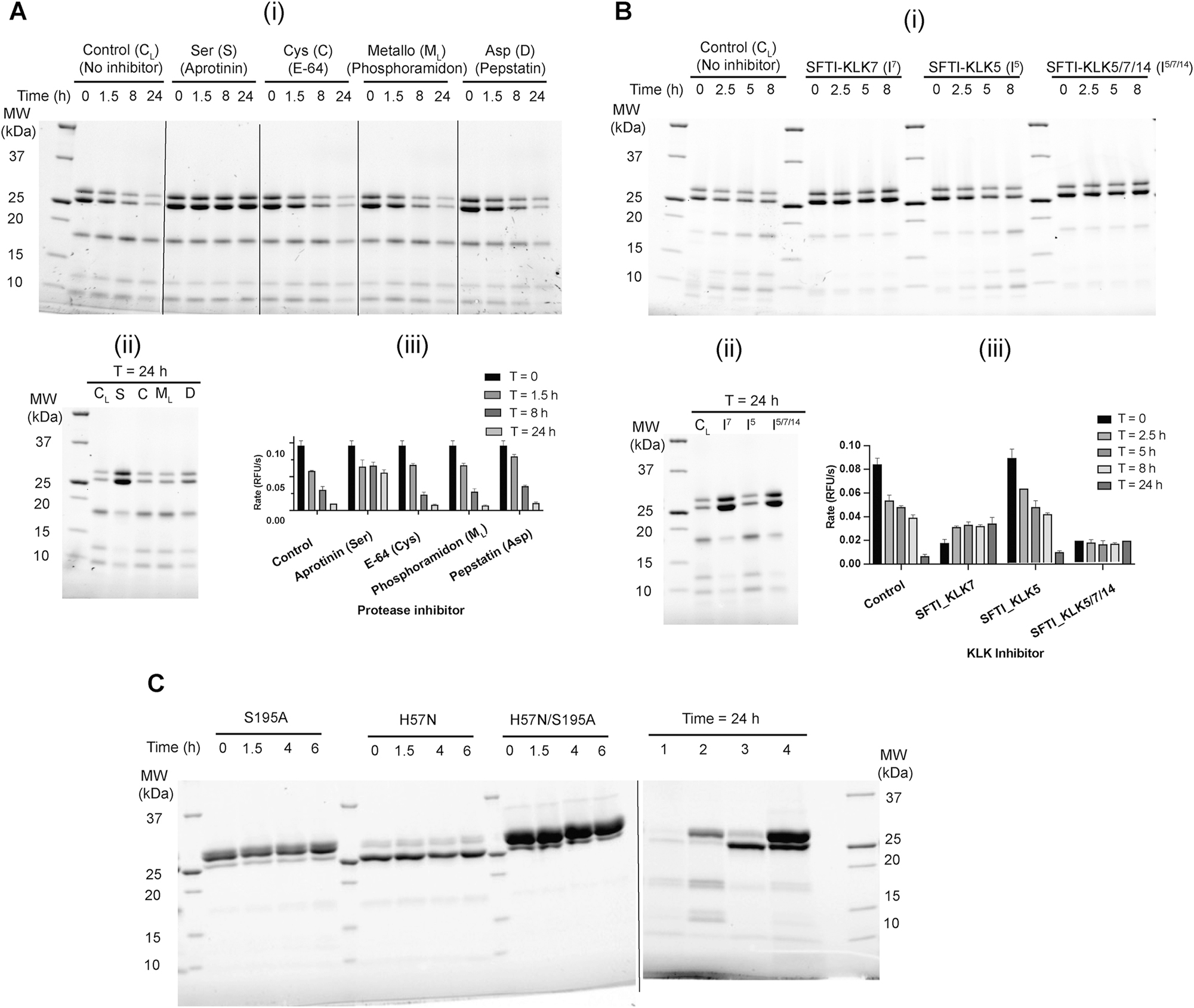

We hypothesized that the observed proteolysis of KLK7 could be attributed to a contaminating protease or to activated KLK7 itself (autolysis). Proteases have been classified into distinct families based on their reaction mechanism and the key active site residue responsible for catalysis. The four main classes of proteases are serine proteases, cysteine proteases, metallo-proteases and aspartic acid proteases. In order to narrow down the possible proteases responsible for cleavage of KLK7, purified active KLK7 was incubated separately with inhibitors that specifically target different families of proteases. Proteolysis was observed in the control sample (no inhibitor), as well as the KLK7 solutions that were treated with inhibitors of cysteine (E-64), metallo- (phosphoramidon), and aspartic acid (pepstatin A) proteases. In contrast, the serine protease inhibitor aprotinin did inhibit proteolysis (Figure 2A).

KLK7 undergoes autolysis. Effect of protease family-specific, and individual protease-specific inhibitors on the proteolysis of KLK7 was probed. Purified active KLK7 (150 μg) expressed in CHO cells was subjected to buffer exchange to 25 mM CHES pH 9.0, 100 mM NaCl, and concentrated to ∼5 mg/mL. (A) Protease inhibitors aprotinin, E-64, phosphoramidon (500 μM each), and pepstatin A (200 μM) were incubated with KLK7 (∼4.5 mg/mL) at 37 °C for 24 h. At various times, two aliquots were removed from each solution; one was quenched with 1× reducing Laemmli buffer, heated at 95 °C for 2 min, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing condition, while the other was diluted in assay buffer and used for monitoring KLK7 protease activity using the fluorescence-based kinetic assay. (i) Time course over the first 8 h; (ii) comparison of proteolysis after 24 h; (iii) proteolytic activity of KLK7 measured using fluorescence based kinetic assay. (B) Similar procedure was adopted for incubation of KLK7 with SFTI-1-derived inhibitors SFTI-KLK7 (I7), SFTI-KLK5 (I5) and SFTI-KLK5/7/14 (I5/7/14) that are specific for KLK7, KLK5, and KLK5/7/14, respectively. Enzyme solutions were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (∼5 mg/mL enzyme and 500 μM SFTI-1-based inhibitor) and proteolysis was monitored as described above. (i) Time course over the first 8 h; (ii) comparison of proteolysis after 24 h; (iii) proteolytic activity of KLK7 measured using fluorescence based kinetic assay. (C) Active site variants of KLK7 are resistant to autolysis. KLK7 variants having active site serine (S195A), active site histidine (H57N) or both mutations were incubated separately at 37 °C in 25 mM CHES pH 9, 150 mM NaCl, and monitored for autolysis as described in Supplementary Figure S1 and materials and methods. Aliquots from the initial 6 h of incubation of the time course are shown on the left panel. The samples on the right panel (right of the dotted line) after 24 h incubation are: 1. Wild-type, 2. S195A, 3. H57N, 4. H57N/S195A. Values in A (iii) and B (iii) are the mean ± SD of duplicate experiments.

To test more conclusively whether KLK7 itself was the relevant protease, incubations were carried out separately with sunflower trypsin inhibitor (SFTI-1)-derived inhibitors specific towards KLK7 only (SFTI-KLK7), KLK5 only (SFTI-KLK5), and all three enzymes KLK5, KLK7 and KLK14 (SFTI-KLK5/7/14) (de Veer et al. 2017) (Figure 2B). The parent SFTI-1 scaffold specific to trypsin-like proteases has a Lys residue at the P1 site, whereas SFTI-KLK7 has a P1-Phe residue and SFTI-KLK5 and SFTI-KLK5/7/14 both have a P1-Arg residue. SFTI-1 inhibitors of KLK7 and KLK5/7/14 prevented proteolysis while the KLK5-specific SFTI-1 inhibitor did not. The zymogen form of KLK7 and active site variants H57N, and H57N/S195A are resistant to proteolysis (Figure 2C). This indicates that the observed proteolysis of KLK7 is in fact autolysis.

Surprisingly, we observed that S195A-KLK7 still retains detectable proteolytic activity (∼4 % of WT), and undergoes autolysis (Figure 2C). Silva and colleagues have reported that S195A is catalytically active (∼1 % of WT activity), and have used D102N/S195A-KLK7 as the preferred inactive KLK7 variant (Silva et al. 2017). We determined that the KLK7 single point mutant H57N is catalytically inactive, and propose it as a preferred inactive variant for KLK7 in any future studies.

2.3 Determining the site and significance of KLK7 autolysis

The autolyzed fragments of KLK7 were subjected to Edman N-terminal sequencing analysis. The fragments generated and detected after autolysis of KLK7 and then disulfide reduction had molecular weights of ∼17 kDa and ∼12 kDa and ∼8 kDa. The ∼17 kDa band consisted of the following two sequences: a major product starting at Ile16, which is the N-terminal residue of active KLK7, and a minor fragment starting at Ser95. The ∼12 kDa band also consisted of a detectable fragment starting at Ile16. The ∼8 kDa band(s) consisted of the following two sequences: the major product starting at Cys182 and the other starting at Ile16. There were other sequences in the 6–10 kDa size range starting at Lys173 and Glu177 in other iterations of the experiment, in which the enzyme was subjected to prolonged incubation (∼36 h at 37 °C). This suggested that lysis occurred in two loops of KLK7 - the 170 loop and the 99 loop, with autolysis at the 170 loop being dominant relative to that in the 99 loop. These data imply that KLK7 autolysis is initiated by precise cleavage in the above two loops.

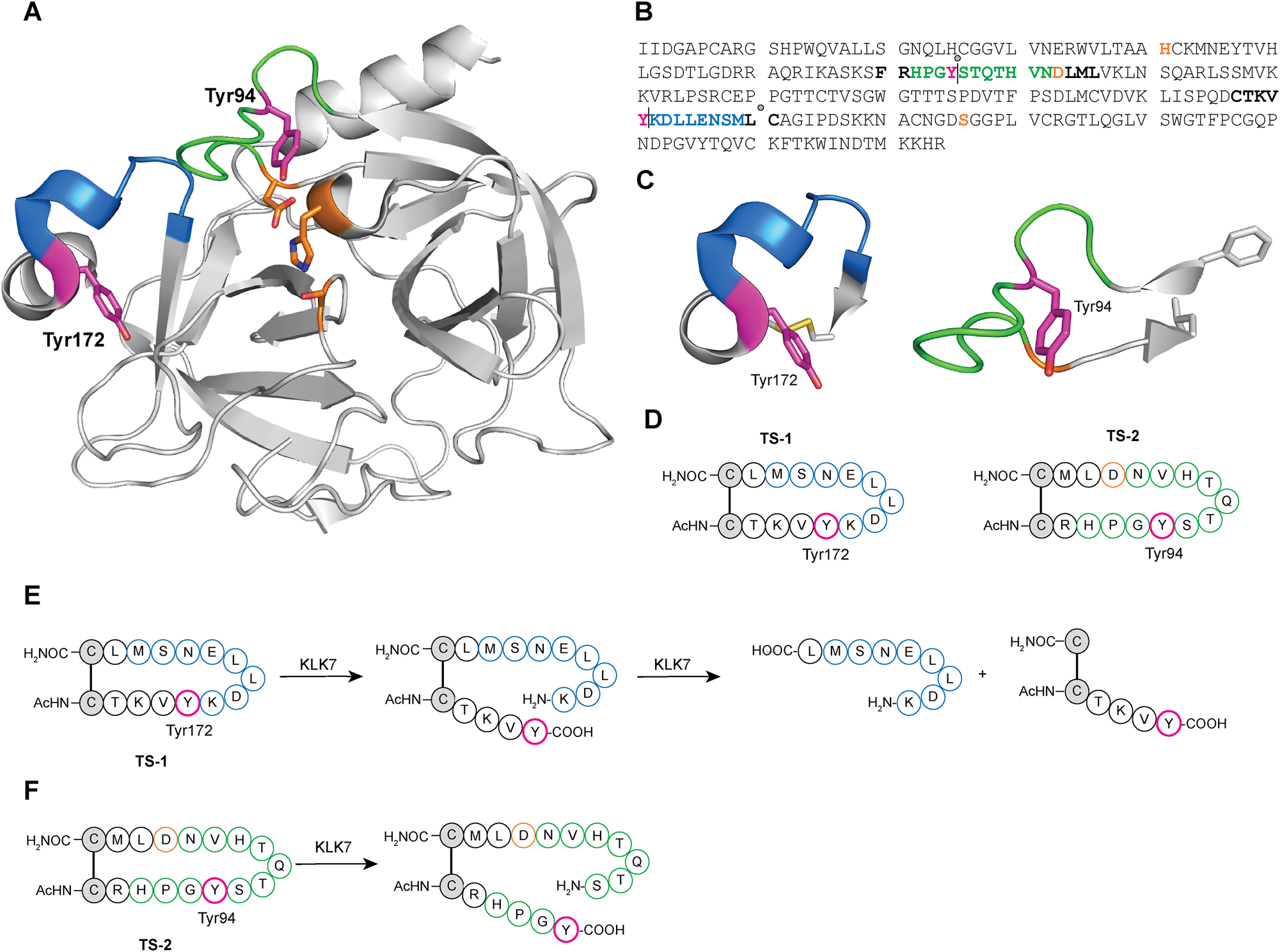

In order to determine and confirm the precise site(s) of autolysis of KLK7, synthetic peptide substrates were designed to mimic the two loops from KLK7 identified from Edman analysis (Figure 3). Multiple crystal structures of KLK7 with bound ligands are available in the PDB (Debela et al. 2007; Fernandez et al. 2007, 2008; Maibaum et al. 2016; Murafuji et al. 2017, 2018a,b, 2019). The crystal structure 2QXH was used as a template for designing the peptide substrates (Debela et al. 2007). Examination of the scission in the 170 loop of KLK7 revealed that the cleavage site is between Leu181 and Cys182. This seemed improbable for two reasons. First, the known substrate specificity of KLK7 as reported in the literature indicates that KLK7 prefers aromatic amino acid residues Tyr and Phe as the P1 residue (Oliveira et al. 2015; Shropshire et al. 2014; Silva et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2015). Second, the cleavage site is buried deep within the enzyme structure. Additionally, the Cys182 sidechain forms a disulfide link to the sidechain of Cys168, and an oxidized cysteine has not been shown, to our knowledge, as the P1′ residue of protease substrates. However, the 170 loop formed by residues between Tyr172 and Met180, has Tyr172 and Lys173, which could be a potential primary cleavage site for KLK7, as observed in the N-terminal sequencing analysis above where Lys173 was detected in one of the minor products. Therefore, a synthetic peptide consisting of residues from Cys168 to Cys182 with both cysteine residues oxidized to form a disulfide, was tested as a substrate (TS-1).

Design of synthetic peptide substrates to determine the substrate specificity and scope of KLK7 autolysis. (A) Crystal structure of KLK7 with 99 (green) and 170 (blue) loops highlighted. The active site catalytic triad is shown in orange. (B) The sequence of active human KLK7 enzyme is shown along with putative and major detected cleavage sites indicated as vertical lines and gray circles, respectively. Color scheme for residues is consistent with that in (A), except that the remaining residues corresponding to the synthetic peptide loops described in (C) are shown in bold black. Cleavage in the putative 99 loop site is expected to yield N- and C-terminal peptide fragments of 8.2 and 16.2 kDa respectively, while that in the 170 loop site of 16.5 kDa and 7.9 kDa respectively. (C) Loops bearing the sites of KLK7 autolysis with P1 tyrosine side chain are shown as sticks in magenta, and terminal residue side chains are shown in gray stick. (D) Scheme and sequence of synthetic peptides designed, with the P1 Tyr highlighted in red. TS-1 was based on the 170 loop, while TS-2 was based on the 99 loop, with acetyl capped N-termini and carboxamide C-termini, respectively. (E) Scheme of sequential peptide hydrolysis of TS-1 by KLK7 first at residue corresponding to Tyr172 in KLK7, followed by sequential hydrolysis at KLK7 residue corresponding to Leu181. (F) Scheme of peptide hydrolysis of TS-2 by KLK7 at residue corresponding to Tyr94 in KLK7.

To further address proteolysis in the 99 loop, we determined that the cleavage site was between Tyr94 and Ser95, based on Edman analysis above. The peptide loop was traced toward both its N- and C-termini until two side chains in close proximity to one another – Phe89 and Leu105 - were found. These two residues were replaced with cysteines in the designed synthetic peptides to facilitate circularization via disulfide bond formation, yielding substrate TS-2.

The peptide loop substrates (100 μM) were individually incubated with WT KLK7 overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was quenched with acetonitrile, and the sample was diluted either with water or aqueous TCEP solution and incubated for 10 min, to obtain intact disulfide-containing peptides, and reduced cysteines in the respective product mixtures. Both peptide substrates were hydrolyzed by KLK7, although to different extents. Under identical conditions and incubation time, KLK7 completely hydrolyzed TS-1, while the hydrolysis of TS-2 was incomplete (Supplementary Figure S2). TCEP-reduced product mixtures were used to identify the sites of lysis. The TS-1 peptide was hydrolyzed C-terminal to both the tyrosine corresponding to Tyr172 and the leucine corresponding to Leu-181, sequentially. The peptide product corresponding to the primary hydrolysis after tyrosine was detected to significant levels. However, peptide product corresponding to primary hydrolysis after the Leu residue was not observed. This indicated that the primary site of autolysis in the 170 loop is after Tyr172 (sequence: CTKVY|KDLLE). This hydrolysis linearizes and exposes the synthetic peptide, and in the context of KLK7 enzyme, the 170 protein loop, to a secondary hydrolysis after Leu181. LC-MS analysis of the product mixture of TS-2 indicates that the enzyme cleaves after Tyr94 in KLK7 (sequence: RHPGY|STQTH). The specific initial rates of hydrolysis for TS-1 and TS-2 determined by HPLC analysis were 25.6 and 19.3 min−1, respectively.

Secondary proteolysis detected between Leu and a disulfide-linked Cys residue in TS-1 synthetic peptide as well as through Edman degradation analysis of autolyzed KLK7 protein fragments indicates KLK7 can accommodate a disulfide-linked cysteine in the P1′ position of its substrate. This finding adds to the known substrate scope and specificity of KLK7 protease as the accommodation of a disulfide-linked Cys in the P1′ site by a serine protease has not been reported previously, to our knowledge. A similar cleavage profile was reported when KLK7 was incubated with oxidized B-chain of insulin, where in addition to proteolysis C-terminal to Tyr/Phe residues, KLK7 also hydrolyzed the Leu – cysteic acid peptide linkage (Skytt et al. 1995).

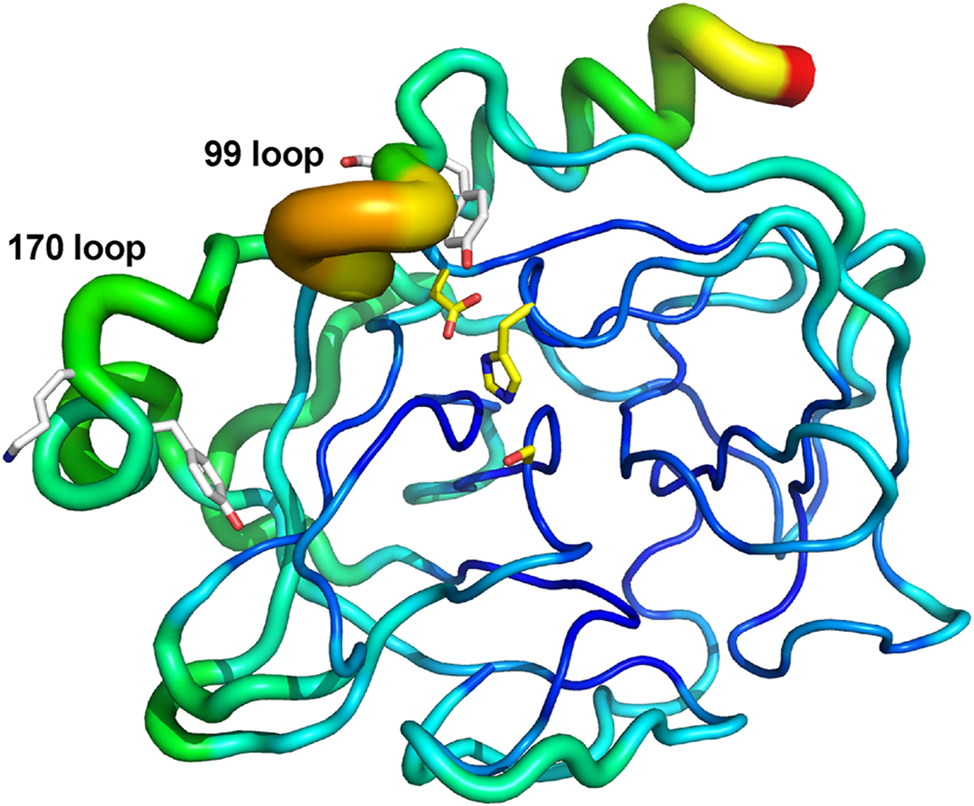

In the crystal structure of human KLK7 with an empty active site (PDB accession code 6Y4S), both Tyr94 and Tyr172 are somewhat sequestered from solvent (Hanke et al. 2020). However, the relative B-factor values in the 99 and 170 loops are higher than other regions of the structure (Figure 4). This suggests that the P1 Tyr94 and Tyr172 autolysis residues are in a region of greater plasticity and can exist in different conformations in solution. In fact, since cleavage occurs at these sites, they must be accessible. Given the negative regulation observed biochemically, we hypothesize that KLK7 autolysis may be physiologically relevant for this important house-keeping enzyme in epidermal and epithelial biology.

Conformational plasticity in human KLK7. B-factor putty cartoon of human KLK7 structure having no ligand bound to the active site (PDB access code 6Y4S; chain A is shown as one of the 3 monomers in the asymmetric unit). Catalytic triad residues are depicted in yellow sticks. Tyr94/Ser95 and Tyr172/Lys173 are depicted in white sticks. Regions of flexibility based on these B-factors range based on this depiction range from lower (narrow tubes in dark blue) to moderate (medium tubes in light blue, green, yellow) to higher (wide tubes in orange/red). Although Tyr94 and Tyr172 are somewhat sequestered from solvent, they reside in or near regions of higher flexibility.

2.4 Bioinformatic analysis of autolyzed KLK7 loops

Extended sequences of both the 170 (CTKVYKDLLENSMLC) and the 99 (FRHPGYSTQTHVNDLML) loops were subjected to BLAST searches within the human proteome using the UniProt database, to probe whether there are similar peptide sequences present in other human proteins (The UniProt Consortium 2023). These sequences may indicate potential signatures for autolytic activity, if present in a chymotryptic-like serine protease, or could instead reveal novel substrates for KLK7. The extended 170 loop (Cys168 to Cys182; Figure 3B) did not yield any sequences containing significant homology to a human protein other than the WT KLK7 itself. The search for sequences homologous to the extended 99 loop (Phe89 to Leu105; Figure 3B), however, indicated that the 99 loop of human α-chymase bears similarity to that of KLK7. Sequence alignment (ClustalO) of full-length enzyme sequences of active forms of human KLK7 and chymase showed 36 % identity and 68 % sequence similarity over the entire length. The 99 loop from these proteases showed 61 % identity, considerably higher than the 36 % identity over their entire length. Human α-chymase is a serine protease with chymotrypsin-like specificity, with a high preference for tyrosine and phenylalanine in the P1 position of its substrates, similar to KLK7. That raised the question whether chymase undergoes autolysis similar to KLK7, or whether either one proteolyzes the other.

2.5 KLK7 proteolyzes and inactivates chymase

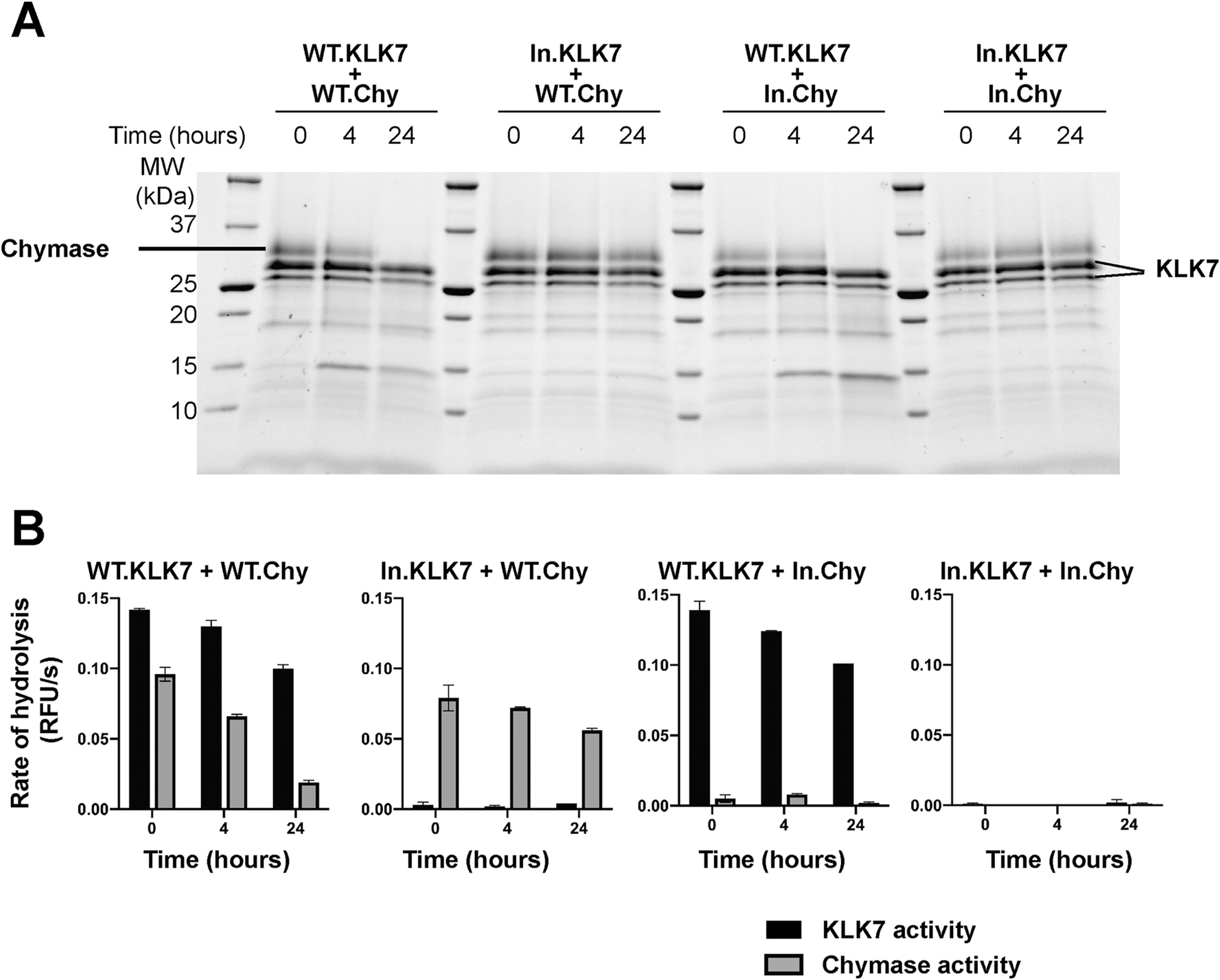

First, we tested whether chymase undergoes autolysis under conditions similar to that of KLK7. We observed no detectable autolysis even after incubation at 37 °C for over 48 h in 25 mM CHES pH 9.0, 150 mM NaCl. Next, we incubated chymase and KLK7 together at pH 7.5 under three conditions where chymase was in excess, KLK7 was in excess, or both enzymes were present in equimolar quantities (Supplementary Figure S3). Discernible proteolytic product formation was observed under equimolar conditions only, with a decrease in the intensity of the chymase protein band, and the product band was distinct from that of the autolysis of KLK7. This indicated that human KLK7 was hydrolyzing human chymase. In order to confirm this observation, we set up a time course experiment co-incubating human KLK7 and chymase enzymes. As controls for this experiment, we needed inactive versions of both enzymes. We obtained those by reacting the two proteases with irreversible serine protease inhibitors respectively. KLK7 was incubated with AEBSF, while chymase was incubated with TPCK, to obtain inactive enzyme-inhibitor complexes.

The enzyme-inhibitor pairs were selected based on preliminary experiments to obtain optimal complex formation, and maximum inhibition. The enzyme inactivation reactions were monitored using activity assays, and the excess inhibitor was separated from the enzyme-inhibitor complexes by desalting (Supplementary Figure S4). Parallel pairwise incubations were set up between KLK7 and chymase, using WT or inactivated forms of both enzymes (Figure 5). Time-dependent proteolytic product formation was observed in incubations containing WT KLK7, i.e. WT KLK7 with WT chymase, and WT KLK7 with TPCK-chymase complex, with concomitant decline in the intensity of the intact chymase bands. Conversely, no proteolysis was observed in the other two incubations, i.e. KLK7-AEBSF complex with WT chymase, and KLK7-AEBSF complex with chymase-TPCK complex. These results indicate that KLK7 proteolyzes chymase when the two proteases are incubated together, but chymase does not affect KLK7. This conclusion was further validated by titrating one enzyme against the other (Supplementary Figure S5). As expected, increasing the concentration of KLK7 in the reaction resulted in a decrease in the total amount of intact chymase, but not vice versa. We tried to determine the primary cleavage site of chymase by KLK7, using Edman degradation. Unlike KLK7 autolysis, where we detect two cleavage products, we detect only one chymase product from proteolysis by KLK7. The apparent cleavage site was C-terminal to Phe127; however, we could not verify whether this was the primary cleavage site since we could not detect sufficient accumulation of any other chymase fragment, presumably due to the presence of two active proteases. The overall rate of proteolysis of chymase by KLK7 was relatively low, and the rate of secondary cleavage(s) may be equivalent to or higher than the rate of the primary cleavage, resulting in hydrolysis of the intermediate fragments.

Human KLK7 proteolyzes and inactivates human chymase. (A) SDS-PAGE gel analysis of the time course of the reaction between human KLK7 and WT chymase over 24 h at 37 °C. Inactivated AEBSF-KLK7 complex (In.KLK7) and inactivated TPCK-chymase complex (In.Chy) were used as controls. The starting concentration of each enzyme or enzyme-inhibitor complex was 4 μM. (B) Activity of each aliquot at corresponding time points as in (A) was measured using a fluorogenic substrate. ES002 was used to measure KLK7 activity, while the chymase activity was measured using Suc-LLVY-AMC substrate by subtracting the activity of KLK7 control from the total measured rate of reaction. Values are the mean ± SD of duplicate independent experiments.

2.6 Other mast cell proteases as potential substrates for KLK7

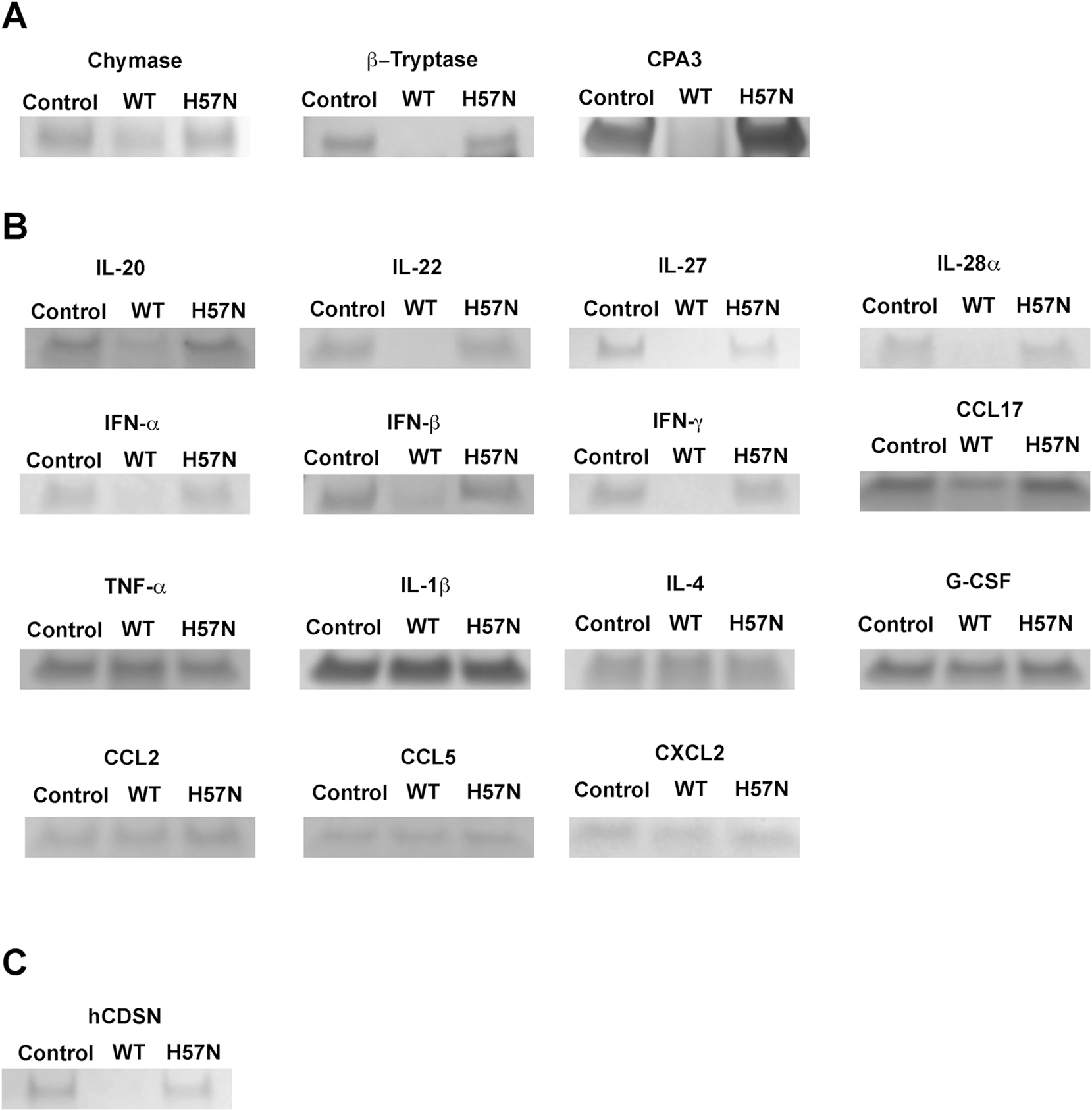

After discovering and validating that human KLK7 proteolyzes human mast cell chymase, we probed whether KLK7 had a broader substrate scope with respect to mast cell proteases. In addition to α-chymase, mast cells contain β-tryptase and carboxypeptidases. Pairwise incubation of KLK7 with mast cell proteases showed that KLK7 is capable of hydrolyzing both β-tryptase and carboxypeptidase 3 (CPA3) (Figure 6A).

Screening proteases and cytokines as potential substrates of KLK7. Various mast cell proteases and cytokines were incubated in the presence (WT) or absence (control) of human wild-type KLK7. Co-incubation of these mast cell proteases with the inactive H57N-KLK7 variant (H57N) was used as an additional negative control. (A) Wild-type KLK7 hydrolyzed the mast cell proteases chymase, β-tryptase, and carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3), while hydrolysis was not observed in the two control samples. (B) KLK7 hydrolyzed IL-20, IL-22, IL-27, IL-28/IFN-λ2, IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-γ, and the chemokine CCL17, while hydrolysis was not detectable under the tested conditions for several cytokines and all tested chemokines. Representative examples of unhydrolyzed cytokines and chemokines are shown here: cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4 and G-CSF and chemokines CCL2, CCL5, and CXCL2. For the full list, see results and supporting information. (C) Human corneodesmosin (hCDSN) is a known substrate for KLK7 in the epidermis, and was used as a positive control for ensuring that wild-type KLK7 was active.

2.7 Cytokines and chemokines as potential substrates for KLK7

Mast cell degranulation results in the release of various small molecules and protein effectors, including various proteases. The discovery that mast cell proteases are substrates of KLK7 led us to ask whether other proteins from mast cell granules are KLK7 substrates. We thought cytokines and chemokines might be prime substrate candidates. We therefore tested a panel of commercially available cytokines and chemokines, not necessarily restricted to those derived from mast cells, as KLK7 substrates. We discovered that human KLK7 can proteolyze various cytokines including interferons (IFN) α, β, and γ, IL-20, IL-22, IL-27 and IL-28A/IFN-λ2 as well as the chemokine CCL17 (Figure 6B); human corneodesmosin (hCDSN) is a known substrate for KLK7 in the epidermis, and was used as a positive control (Figure 6C) (Caubet et al. 2004; Ishida-Yamamoto and Igawa 2015). We validated these hits by incubating a fixed concentration of each cytokine with increasing concentration of KLK7 (Supplementary Figure S6). KLK7 did not hydrolyze the following tested cytokines: TNF-α, G-CSF, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IL-17a, IL-19, IL-23, IL-24, IL-29 and IL-36β. KLK7 did not hydrolyze any of the following tested chemokines: CCL2, CCL5, CCL11, CCL22 and CXCL2.

3 Discussion

Several studies have shown that certain human kallikreins are susceptible to autolysis. KLK6 and KLK11 have trypsin-like specificity and have been suggested to undergo autolytic inactivation, although their autolysis cleavage sites reside in the 70 loop and 150 loop, respectively (Bayes et al. 2004; Blaber et al. 2007; Luo et al. 2006). Human KLK12 and KLK14 also appear to undergo autolytic degradation with trypsin-like specificity, although the autolysis sites have not been definitely identified for KLK12 and there are multiple ones for KLK14 (Borgono et al. 2007; Memari et al. 2007). More recently, KLK2 has been carefully studied where its autolytic inactivation is notably dependent upon the degree of glycosylation of the 99 loop (Guo et al. 2016). In a study on KLK7 degradomics, autoproteolysis of KLK7 was suggested, although a thorough analysis was not carried out (Yu et al. 2015).

We used protease-specific inhibitors and active site variants to generate data showing that KLK7 undergoes autolysis at two separate sites in the 170 and 99 loops, resulting in a loss of its enzymatic activity. It is important to note that KLK7 autolysis is not complete self-degradation, but an initial clipping of surface loops followed by proteolysis of the fragments. It is plausible that the cleaved enzyme, held together by six disulfide linkages, may continue to possess some proteolytic activity even after autolysis. Clipped non-glycosylated KLK2 was shown to be active, while inactivation was confirmed upon further autolysis, with cleavages at up to five sites (Guo et al. 2016). Recognition and hydrolysis of peptide loop substrates demonstrated that the autolysis of KLK7 proceeds in trans. This is consistent with the observation that autolysis is incomplete since the rate is proportional to the active enzyme concentration. Both N-terminal sequencing analysis as well as hydrolysis rates of peptide loop substrates showed that hydrolysis at the 170 loop of KLK7 proceeds faster than at the 99 loop, although the difference in rates is only 20–25 %. Identification of disulfide-bridged cysteine residue in the KLK7 peptidase cleavage site suggests that peptide loops containing disulfide-linked cysteines provide useful and powerful probes for examining protease substrate specificity and can reveal novel sites of lysis and expand known substrate scope.

We show that mast cell chymase is cleaved and inactivated by KLK7, a nonintuitive finding derived from a BLAST search analysis. Chymase is a major constituent of the granules of mast cells from the connective tissue and the sub-mucosa, and therefore, is widely distributed in the body (Pejler 2020). Mast cells are believed to play an important role in the early phases of the innate immune responses against pathogens. Mast cell degranulation leads to the release of histamine, proteases such as chymase, β-tryptase, and carboxypeptidase A, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Elieh Ali Komi et al. 2020). Since KLK7 is known as a housekeeping extracellular enzyme, and because it cleaves and inactivates chymase, we hypothesized that KLK7 may proteolyze other secreted components of mast cells or recruited effectors. Indeed, we discovered that KLK7 is also capable of proteolyzing β-tryptase and carboxypeptidase A (CPA3), which are the other major mast cell proteases. Mast cell proteases cleave a variety of protein substrates that may be either protective or detrimental to normal healthy physiology (Elieh Ali Komi et al. 2020; Pejler 2020). Under healthy physiological conditions, mast cell proteases are compartmentalized within mast cell granules, while KLK7 maintains epidermal and epithelial homeostasis in the extracellular matrix. Therefore, the probable conditions under which these proteases and KLK7 come in contact with one another are post-mast cell degranulation in the skin or epithelial layers in the lungs or gut. We speculate that cleavage and inactivation of mast cell proteases by KLK7 might play a role in the resolution of mast cell degranulation-induced inflammation and in the restoration of healthy tissue conditions.

We also discovered that KLK7 can proteolyze specific cytokines: interferons (IFN) α, β, and γ, IL-20, IL-22, IL-27, and IL-28A/IFN-λ2, as well as the chemokine CCL17. Of these, mast cells have been reported to produce type I IFNs (IFN-α, IFN-β) in response to viral infections, as well as IL-22 and IFN-γ to augment their own activation, proliferation, and cytokine secretion. While our rationale to test cytokines as potential substrates of KLK7 was based on mast cell biology, the biological context in which these cytokines are hydrolyzed by KLK7 may not be limited to mast cell degranulation. Despite testing a wide range of cytokines, our results indicate that KLK7 hydrolyzes only a specific and limited set of cytokines. A closer look at the hits reveals that they largely belong to two families of cytokines: the interferon family (IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-γ, as well as IL-28A/IFN-λ2), and the IL-20 family (IL-20, IL-22, and IL-28A/IFN-λ2), which is part of the larger IL-10 family. IL-27 belongs to the IL6/IL-12 family. Both the interferon and IL-20 families of cytokines are evolutionarily closely related to one another, and belong to the type II family of cytokines. These signaling molecules are upregulated, and have been implicated in the anti-viral response of the innate immune system. There are still several outstanding questions about the sites of cleavage, the nature of fragments generated by the proteolysis by KLK7, and its effect on the activity of the cytokines. However, due to the pleiotropic nature of the physiological effects of cytokines and chemokines, the interaction between each cytokine or chemokine substrate and KLK7 should be studied in greater depth, which is outside the scope of the present study.

It is noteworthy that KLK7 may play a role in signaling related to viral infections in humans. Kallikrein-related peptidases and other serine proteases have been shown to modulate viral entry into host cells by processing either the viral surface proteins or the host cell receptors (Pampalakis et al. 2021). Some examples include the involvement of KLK1, KLK5, and KLK12 in influenza infection, that of KLK13 in coronavirus infection, KLK8 in human papillomavirus skin infection, as well as KLK5 and KLK7 in varicella zoster virus (chickenpox/shingles) infections. However, the mechanisms of action of these proteases have not to date included the proteolytic degradation of cytokines. The findings of this study, therefore, provide a new angle of investigation into the action of these proteases in viral and other infections.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Materials

The fluorogenic substrate ES002 containing the FRET pair of (7-methoxycoumarin-4-yl) acetyl (Mca) and 2,4-dinitrophenyl (Dnp) was purchased from R&D systems. Suc-LLVY-AMC was from R&D systems or Boston Biochem. 4-(2-Aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF) and tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) were from Sigma Aldrich. Aprotinin and E-64 were procured from Tocris Biosciences, phosphoramidon from Sigma, and pepstatin from EMD Millipore. Wild-type (WT) recombinant human chymase was obtained from Sigma (C8118). All cytokines and chemokines were purchased from R&D systems. Carboxypeptidase 3 was purchased from Mybiosource. Wild-type β-Tryptase enzyme was obtained as described elsewhere (Maun et al. 2018). TGX stain-free SDS-PAGE pre-cast gels were obtained from Bio-Rad and were imaged using Bio-Rad GelDoc EZ imager. Staining of gels was carried out using InstantBlue® from Expedon according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Molecular weight markers were from Bio-Rad.

4.2 General assay methods

LC-MS analysis of peptides was carried out with an Agilent PLRP-S reversed-phase column (1000 A, 8 µm, 50 × 2.1 mm) using an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity instrument in series with a 6224 time-of-flight mass spectrometer. HPLC runs were carried out using 0.05 % TFA in water as solvent A and acetonitrile containing 0.05 % TFA as solvent B. Analytes were eluted using a gradient of solvent B from 5 to 60 % over 6 min, followed by 100 % solvent B for 1 min. Protein samples were analyzed using SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and stained with InstantBlue® unless mentioned otherwise.

Enzyme assays were conducted in 75 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 % DMSO and 0.01 % Tween-20 at 25 °C with a final volume of 50 μL, unless noted otherwise. Human KLK7 (KLK7) WT and variant enzymes were used at a concentration of 5–50 nM, while the concentration of the fluorogenic substrate ES002 was varied between 0 and 96 μM. Proteolysis of substrate was indicated by the increased fluorescence of product and was monitored at 340 nm and 460 nm for absorption and emission wavelengths, respectively. Assays were carried out in 96-well Corning half-area black-bottom polystyrene 96-well microplates using a Spectramax M5e spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices).

We determined the glycosylation pattern and verified the sequence of KLK7 after digesting the enzyme with LysC + chymotrypsin, separating the peptides on an Agilent AdvanceBio Peptide Map column with an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system. The digest was analyzed by an Agilent 6545 XT AdvanceBio LC Q-TOF LCMS-MS mass spectrometer using Agilent’s MassHunter software.

4.3 Cloning and expression of human KLK7 WT and variants

DNA encoding human KLK7 (Uniprot P49862 residues Ile30 to Arg253; chymotrypsinogen numbering is used throughout this paper (Hartley 1970), so Ile30 becomes Ile16) with an enterokinase (EK) cleavable His6 tag at the N-terminus (HHHHHHDDDK) was synthesized, and subcloned into a modified pRK5 expression vector under control of the CMV promoter. The cloned plasmid was transfected into either CHO-K1 or Expi293 cells, which were seeded at 2 × 106 cells/mL using the HyCell TransFX-H with AAG media. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 and were fed 24 h post-transfection using NS2 modified for the process (contains 98 mg/L ciprofloxacin and 7.2 mM valproic acid). Cells were harvested 7 days post transfection, separated by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm, and the clarified media (filtration using 0.45 μm filter) was subjected to protein purification to isolate the secreted KLK7 zymogen.

4.4 Purification of human KLK7 WT and variants

Expressed zymogens with N-terminal His6-tags were purified using nickel affinity chromatography. His-trap FF 5 mL columns (GE Lifesciences) were equilibrated with PBS, pH 7.4 using a GE Akta FPLC system. Cell-free media containing secreted zymogen with N-terminal His6-tag was passed through the column. The column was then washed with 8 column volumes of PBS buffer containing 25 mM imidazole (pH 7.4). The bound protein was eluted using an imidazole gradient in PBS buffer from 25 to 500 mM over 10 column volumes (pH 7.4). Chromatography was monitored using UV absorbance at 280 nm and the eluted fractions were analyzed with SDS-PAGE gels. The fractions containing the target protein were pooled together, and concentrated using centrifugal filters (10 kDa cutoff, Amicon® Ultra – Millipore). The final concentration was determined using nanodrop by measuring UV absorbance at 280 nm, and using the calculated molar extinction coefficient from the ExPASY Protparam online tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/). Protein was divided into convenient aliquots, flash frozen, and stored at −80 °C until used.

KLK7 enzymes (WT and variants) were obtained by cleaving the His6-tag using EK. Aliquots of N-terminal His6-tagged zymogen were thawed and subjected to buffer exchange with 20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl using a PD-10 desalting column (Cytiva). Enterokinase (Roche or Sigma) was added at a ratio of 1:100 by weight of the zymogen; the reaction was incubated at room temperature for 1 h and then at 4 °C overnight. The final reaction solution contained zymogen at no more than 1 mg/mL, and the corresponding amount of EK. EK cleavage was monitored by SDS-PAGE gels and after completion, the activated KLK7 was purified using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) in 20 mM MES pH 6.0, 200 mM NaCl on an S200 16/600 column (Cytiva). Elution was monitored at 280 nm, and fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing pure enzyme were pooled together, concentrated using centrifugal filters with 10 kDa molecular weight cutoff, and flash frozen after determining their concentration as described above (ε280nm = 34,200 M−1 cm−1, estimated molecular weight = 24,448 Da).

4.5 pH dependence of KLK7 proteolysis

Active purified KLK7 (100 μg each) expressed in CHO cells was diluted with 400 μL buffer. Buffers used were 25 mM MES and 100 mM NaCl for pH 6, PBS for pH 7.4, 25 mM HEPES and 100 mM NaCl for pH 8.0, and 25 mM CHES and 100 mM NaCl for pH 9.0. Each of these diluted enzyme solutions was concentrated using pre-cooled 10 kDa cut-off centrifugal filters (0.5 mL, Millipore) to ∼50 μL. The concentrated protein solution was then diluted with 400 μL of the appropriate buffer and reconcentrated twice to ensure adequate buffer exchange. The final volume was adjusted to 20–25 μL (4–5 mg/mL of enzyme solution) and the samples were incubated at 37 °C for 2 days. For every time point, 1 μL of enzyme solution was removed and added to 19 μL of 1× reducing Laemmli buffer, followed by heat denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min. Samples were stored at −20 °C before running on SDS-PAGE gels.

4.6 Proteolysis in the presence of protease inhibitors

Purified active KLK7 (150 μg) was buffer-exchanged into 25 mM CHES pH 9.0, 100 mM NaCl as described above and concentrated to a final volume of ∼30 μL (∼5 mg/mL). Protease inhibitors aprotinin, E-64, and phosphoramidon were separately solubilized to 5 mM stock concentration, while pepstatin A was solubilized to 2 mM stock concentration. Each inhibitor solution (0.5 μL) was added to 4.5 μL of enzyme solution to give a final concentration of ∼4.5 mg/mL (180 μM) enzyme and 500 μM protease inhibitor (200 μM for pepstatin A). Solutions were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. At various times, a 0.5 μL aliquot was removed from each solution and mixed with 9.5 μL of 1× reducing Laemmli buffer, and heated at 95 °C for 2 min. The samples were stored at −20 °C until before running on SDS-PAGE gels.

Similar procedures were adopted for incubation of KLK7 with SFTI-1-derived inhibitors specific towards KLK7, KLK5, and KLK5/7/14. KLK7 (250 μg) expressed in CHO cells was buffer exchanged to ∼25 μL in 10 mM MES pH 6.0, 100 mM NaCl. This enzyme solution was diluted to a final buffer containing 25 mM CHES pH 9.0, 100 mM NaCl, ∼5 mg/mL enzyme and 500 μM SFTI-1-based inhibitor. Enzyme solutions were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and proteolysis was monitored as described above.

4.7 N-terminal sequencing to determine the site of proteolysis

KLK7 (∼25 μg) was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in 25 mM CHES pH 9.0, 100 mM NaCl for adequate proteolysis product to form. The protein constituents of the mixture were then separated on 16 % Tricine gels under reducing conditions. Bands were excised and subjected to N-terminal sequencing using Edman degradation. The original protein solution was also subjected to intact mass spectrometry for additional confirmation of the protein fragment identities.

4.8 Peptide synthesis and enzyme assays using peptide loops as substrates

Non-fluorogenic peptide substrates were synthesized using standard Fmoc chemistry by the peptide synthesis group at Genentech. Peptides having an N-terminal acetyl and a C-terminal amide were derived from the WT enzyme sequences of KLK7 and chymase. Test peptide substrates (100 μM) were incubated with 0.25 μM enzyme for a defined amount of time in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl at 37 °C. Aliquots of the reaction were quenched by mixing with equal volume of acetonitrile containing 0.1 % TFA. The quenched aliquot was then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 2 min to separate any insoluble material, part of the supernatant was then diluted with an equal volume of water or water containing 2 mM Tris(2-chloroethyl) phosphine (TCEP) if reducing conditions were desired. These samples, containing 25 μM peptide or equivalent products, were then subjected to analysis by LC-MS.

4.9 Generation of inactive enzyme-inhibitor complexes of KLK7 and chymase

Wild-type active KLK7 (∼35 μM) was incubated with 1 mM AEBSF, while WT chymase (∼8 μM) was incubated with 0.4 mM TPCK in 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl. Reactions were incubated overnight at 4 °C, alongside identical control solutions lacking any of these two irreversible inhibitors. Completion of the reactions was verified by measuring the proteolytic activity of the control and reaction solutions using fluorogenic substrates. ES002 was used to determine the activity of KLK7 while Suc-LLVY-AMC was used to monitor the activity of chymase. Both reactions showed that >95 % of the enzyme activity was lost upon incubation with their respective irreversible inhibitors. Excess inhibitor was removed from each enzyme-inhibitor complex by desalting using centrifugal filters (10 kDa) by repeated cycles of concentration and dilution using 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl. Both AEBSF-KLK7 and TPCK-chymase complexes were concentrated to ∼1.1 mg/mL.

4.10 Time course of KLK7 and chymase incubation

Wild-type active KLK7 and chymase were incubated with each other, as well as with the inactive irreversible inhibitor complex of one another at 37 °C overnight. Each enzyme and enzyme-inhibitor complex were incubated at 4 μM in 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl. Aliquots were removed for running SDS-PAGE gel (15 μL, containing ∼2 μg enzyme and/or enzyme-inhibitor complex each) at various times, and the reaction was quenched by adding 0.75 μL of 5 N HCl. Quenched aliquots were frozen and stored at −4 °C until the completion of the experiment. Simultaneously, 0.75 μL aliquots were diluted using 75 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01 % Tween-20 to a final concentration of 100 nM enzyme or inactivated enzyme complex for determining the activity of each enzyme respectively, and immediately flash frozen. At the end of the time course, all frozen samples were thawed, neutralized using 4.2 μL of 1 N NaOH, diluted using 2× reducing Laemmli sample buffer, and heated at 95 °C for 2 min. Samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Samples reserved for activity assays were thawed, and enzyme activity was determined using 10 μM substrate and 10 nM enzyme or enzyme-complex each, in 75 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01 % Tween-20, at 25 °C. ES002 was used to determine KLK7 activity, while the activity attributable of chymase was determined by the rate of hydrolysis of Suc-LLVY-AMC in the sample, after subtracting the rate of hydrolysis of Suc-LLVY-AMC by an equivalent sample of pure KLK7.

4.11 Testing mast cell proteases as KLK7 substrates

Each active mast cell protease (2 μM) was incubated pairwise with WT KLK7, alongside controls containing either no enzyme or the inactive active site variant H57N-KLK7 in PBS overnight at 37 °C for ∼16 h. The incubation mixtures were acidified with 1 μL of 0.2 N HCl and heated at 95 °C for 10 min to quench the reactions. The solutions were then neutralized with 2 μL of 0.1 N NaOH, treated with 2× SDS-PAGE reducing sample buffer (prepared using 4× Bolt™ LDS sample buffer and 20× Bolt™ sample reducing buffer), and protein samples were denatured by heating at 95 °C for 2 min. Samples were then analyzed using Bolt™ 4–12 % Bis-Tris Plus gels using 1× Bolt™ MES SDS buffer (prepared from 20× stock).

4.12 Testing cytokines and chemokines as KLK7 substrates

Each cytokine or chemokine (either 150 ng or 75 ng) was incubated in a final volume of 15 μL with WT KLK7 in 10:1 (w/w) ratio in PBS at 37 °C for ∼16 h. Parallel sets of control reactions, one containing no enzyme, and the other containing the inactive variant H57N-KLK7, were maintained. After overnight incubation, the three incubations for each cytokine were quenched by the addition of 1 μL of 0.2 N HCl, and heating at 95 °C for 10 min. The solutions were then neutralized with 2 μL of 0.1 N NaOH, treated with 2× SDS-PAGE reducing sample buffer (prepared using 4× Bolt™ LDS sample buffer and 20× Bolt™ sample reducing buffer), and protein samples were denatured by heating at 95 °C for 2 min. Samples were then analyzed using Bolt™ 4–12 % Bis–Tris Plus gels using 1× Bolt™ MES SDS buffer (prepared from 20× stock). For validating the hits, each cytokine (∼1 μM) was incubated with varying concentrations of WT KLK7 (0, 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 μM) in PBS in a final volume of 15 μL at 37 °C for ∼4 h. Quenching and analysis were the same as described above.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aimin Song and Jeff Tom for peptide synthesis, Hong Li and Ryan Abraham for initial protein purification, Peter Liu, Zhen Zeng, Dick Vandlen, and Wendy Sandoval for protein mass spectrometry support, and Henry Maun for β-tryptase. We also thank Daniel Kirchhofer, Andrea Cochran, Henry Maun and Charles Eigenbrot for helpful discussions.

-

Research ethics: No animal or human ethics approval was required to complete this work.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: Both authors are current employees of Genentech, Inc., a member of the Roche group and are shareholders of Roche.

-

Research funding: All funding was provided by Genentech, Inc.

-

Data availability: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Bayes, A., Tsetsenis, T., Ventura, S., Vendrell, J., Aviles, F.X., and Sotiropoulou, G. (2004). Human kallikrein 6 activity is regulated via an autoproteolytic mechanism of activation/inactivation. Biol. Chem. 385: 517–524, https://doi.org/10.1515/bc.2004.061.Search in Google Scholar

Blaber, S.I., Yoon, H., Scarisbrick, I.A., Juliano, M.A., and Blaber, M. (2007). The autolytic regulation of human kallikrein-related peptidase 6. Biochemistry 46: 5209–5217, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi6025006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Borgono, C.A., Michael, I.P., Shaw, J.L., Luo, L.Y., Ghosh, M.C., Soosaipillai, A., Grass, L., Katsaros, D., and Diamandis, E.P. (2007). Expression and functional characterization of the cancer-related serine protease, human tissue kallikrein 14. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 2405–2422, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m608348200.Search in Google Scholar

Brattsand, M., Stefansson, K., Lundh, C., Haasum, Y., and Egelrud, T. (2005). A proteolytic cascade of kallikreins in the stratum corneum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 124: 198–203, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-202x.2004.23547.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Caubet, C., Jonca, N., Brattsand, M., Guerrin, M., Bernard, D., Schmidt, R., Egelrud, T., Simon, M., and Serre, G. (2004). Degradation of corneodesmosome proteins by two serine proteases of the kallikrein family, SCTE/KLK5/hK5 and SCCE/KLK7/hK7. J. Invest. Dermatol. 122: 1235–1244, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-202x.2004.22512.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Chavarria-Smith, J., Chiu, C.P.C., Jackman, J.K., Yin, J., Zhang, J., Hackney, J.A., Lin, W.Y., Tyagi, T., Sun, Y., Tao, J., et al.. (2022). Dual antibody inhibition of KLK5 and KLK7 for Netherton syndrome and atopic dermatitis. Sci. Transl. Med. 14: eabp9159, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abp9159.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Clements, J.A., Willemsen, N.M., Myers, S.A., and Dong, Y. (2004). The tissue kallikrein family of serine proteases: functional roles in human disease and potential as clinical biomarkers. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 41: 265–312, https://doi.org/10.1080/10408360490471931.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Cudic, M. and Fields, G.B. (2009). Extracellular proteases as targets for drug development. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 10: 297–307, https://doi.org/10.2174/138920309788922207.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

de Veer, S.J., Furio, L., Swedberg, J.E., Munro, C.A., Brattsand, M., Clements, J.A., Hovnanian, A., and Harris, J.M. (2017). Selective substrates and inhibitors for kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) shed light on KLK proteolytic activity in the stratum corneum. J. Invest. Dermatol. 137: 430–439, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.09.017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Debela, M., Hess, P., Magdolen, V., Schechter, N.M., Steiner, T., Huber, R., Bode, W., and Goettig, P. (2007). Chymotryptic specificity determinants in the 1.0 Å structure of the zinc-inhibited human tissue kallikrein 7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104: 16086–16091, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707811104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Diamandis, E.P., Scorilas, A., Kishi, T., Blennow, K., Luo, L.Y., Soosaipillai, A., Rademaker, A.W., and Sjogren, M. (2004). Altered kallikrein 7 and 10 concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Clin. Biochem. 37: 230–237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.11.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Diamandis, E.P. and Yousef, G.M. (2001). Human tissue kallikrein gene family: a rich source of novel disease biomarkers. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 1: 182–190, https://doi.org/10.1586/14737159.1.2.182.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Dorn, J., Gkazepis, A., Kotzsch, M., Kremer, M., Propping, C., Mayer, K., Mengele, K., Diamandis, E.P., Kiechle, M., Magdolen, V., et al.. (2014). Clinical value of protein expression of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) in ovarian cancer. Biol. Chem. 395: 95–107, https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2013-0172.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Elieh Ali Komi, D., Wohrl, S., and Bielory, L. (2020). Mast cell biology at molecular level: a comprehensive review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 58: 342–365, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-019-08769-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Fernandez, I.S., Standker, L., Forssmann, W.G., Gimenez-Gallego, G., and Romero, A. (2007). Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of human kallikrein 7, a serine protease of the multigene kallikrein family. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 63: 669–672, https://doi.org/10.1107/s1744309107031764.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Fernandez, I.S., Standker, L., Magert, H.J., Forssmann, W.G., Gimenez-Gallego, G., and Romero, A. (2008). Crystal structure of human epidermal kallikrein 7 (hK7) synthesized directly in its native state in E. coli: insights into the atomic basis of its inhibition by LEKTI domain 6 (LD6). J. Mol. Biol. 377: 1488–1497, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.089.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Guo, S., Skala, W., Magdolen, V., Briza, P., Biniossek, M.L., Schilling, O., Kellermann, J., Brandstetter, H., and Goettig, P. (2016). A single glycan at the 99-loop of human kallikrein-related peptidase 2 regulates activation and enzymatic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 291: 593–604, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m115.691097.Search in Google Scholar

Hanke, S., Tindall, C.A., Pippel, J., Ulbricht, D., Pirotte, B., Reboud-Ravaux, M., Heiker, J.T., and Strater, N. (2020). Structural studies on the inhibitory binding mode of aromatic coumarinic esters to human kallikrein-related peptidase 7. J. Med. Chem. 63: 5723–5733, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01806.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hansson, L., Stromqvist, M., Backman, A., Wallbrandt, P., Carlstein, A., and Egelrud, T. (1994). Cloning, expression, and characterization of stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme. A skin-specific human serine proteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 19420–19426, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(17)32185-3.Search in Google Scholar

Hartley, B.S. (1970). Homologies in serine proteinases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 257: 77–87, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1970.0010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Heiker, J.T., Klöting, N., Kovacs, P., Kuettner, E.B., Sträter, N., Schultz, S., Kern, M., Stumvoll, M., Blüher, M., and Beck-Sickinger, A.G. (2013). Vaspin inhibits kallikrein 7 by serpin mechanism.. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 70: 2569–2583, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-013-1258-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Igawa, S., Kishibe, M., Minami-Hori, M., Honma, M., Tsujimura, H., Ishikawa, J., Fujimura, T., Murakami, M., and Ishida-Yamamoto, A. (2017). Incomplete KLK7 secretion and upregulated LEKTI expression underlie hyperkeratotic stratum corneum in atopic dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 137: 449–456, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ishida-Yamamoto, A. and Igawa, S. (2015). The biology and regulation of corneodesmosomes. Cell Tissue Res. 360: 477–482, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-014-2037-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Johnson, S.K., Ramani, V.C., Hennings, L., and Haun, R.S. (2007). Kallikrein 7 enhances pancreatic cancer cell invasion by shedding E-cadherin. Cancer 109: 1811–1820, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.22606.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kalinska, M., Meyer-Hoffert, U., Kantyka, T., and Potempa, J. (2016). Kallikreins – the melting pot of activity and function. Biochimie 122: 270–282, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.023.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kasparek, P., Ileninova, Z., Zbodakova, O., Kanchev, I., Benada, O., Chalupsky, K., Brattsand, M., Beck, I.M., and Sedlacek, R. (2017). KLK5 and KLK7 ablation fully rescues lethality of Netherton syndrome-like phenotype. PLoS Genet. 13: e1006566, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006566.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kishibe, M. (2019). Physiological and pathological roles of kallikrein-related peptidases in the epidermis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 95: 50–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.06.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Komatsu, N., Tsai, B., Sidiropoulos, M., Saijoh, K., Levesque, M.A., Takehara, K., and Diamandis, E.P. (2006). Quantification of eight tissue kallikreins in the stratum corneum and sweat. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126: 925–929, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jid.5700146.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lundwall, A., Band, V., Blaber, M., Clements, J.A., Courty, Y., Diamandis, E.P., Fritz, H., Lilja, H., Malm, J., Maltais, L.J., et al.. (2006). A comprehensive nomenclature for serine proteases with homology to tissue kallikreins. Biol. Chem. 387: 637–641, https://doi.org/10.1515/bc.2006.082.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Luo, L.Y., Shan, S.J., Elliott, M.B., Soosaipillai, A., and Diamandis, E.P. (2006). Purification and characterization of human kallikrein 11, a candidate prostate and ovarian cancer biomarker, from seminal plasma. Clin. Cancer Res. 12: 742–750, https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-05-1696.Search in Google Scholar

Maibaum, J., Liao, S.M., Vulpetti, A., Ostermann, N., Randl, S., Rudisser, S., Lorthiois, E., Erbel, P., Kinzel, B., Kolb, F.A., et al.. (2016). Small-molecule factor D inhibitors targeting the alternative complement pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12: 1105–1110, https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2208.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Maun, H.R., Liu, P.S., Franke, Y., Eigenbrot, C., Forrest, W.F., Schwartz, L.B., and Lazarus, R.A. (2018). Dual functionality of β-tryptase protomers as both proteases and cofactors in the active tetramer. J. Biol. Chem. 293: 9614–9628, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m117.812016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Memari, N., Jiang, W., Diamandis, E.P., and Luo, L.Y. (2007). Enzymatic properties of human kallikrein-related peptidase 12 (KLK12). Biol. Chem. 388: 427–435, https://doi.org/10.1515/bc.2007.049.Search in Google Scholar

Milstone, L.M. (2004). Epidermal desquamation. J. Dermatol. Sci. 36: 131–140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.05.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mo, L., Zhang, J., Shi, J., Xuan, Q., Yang, X., Qin, M., Lee, C., Klocker, H., Li, Q.Q., and Mo, Z. (2010). Human kallikrein 7 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like changes in prostate carcinoma cells: a role in prostate cancer invasion and progression. Anticancer Res. 30: 3413–3420.Search in Google Scholar

Murafuji, H., Muto, T., Goto, M., Imajo, S., Sugawara, H., Oyama, Y., Minamitsuji, Y., Miyazaki, S., Murai, K., and Fujioka, H. (2019). Discovery and structure-activity relationship of imidazolinylindole derivatives as kallikrein 7 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 29: 334–338, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.11.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Murafuji, H., Sakai, H., Goto, M., Imajo, S., Sugawara, H., and Muto, T. (2017). Discovery and structure-activity relationship study of 1,3,6-trisubstituted 1,4-diazepane-7-ones as novel human kallikrein 7 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 27: 5272–5276, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.10.030.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Murafuji, H., Sakai, H., Goto, M., Oyama, Y., Imajo, S., Sugawara, H., Tomoo, T., and Muto, T. (2018a). Structure-based drug design of 1,3,6-trisubstituted 1,4-diazepan-7-ones as selective human kallikrein 7 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 28: 1371–1375, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.03.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Murafuji, H., Sugawara, H., Goto, M., Oyama, Y., Sakai, H., Imajo, S., Tomoo, T., and Muto, T. (2018b). Structure-based drug design to overcome species differences in kallikrein 7 inhibition of 1,3,6-trisubstituted 1,4-diazepan-7-ones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 26: 3639–3653, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2018.05.044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Oliveira, J.R., Bertolin, T.C., Andrade, D., Oliveira, L.C., Kondo, M.Y., Santos, J.A., Blaber, M., Juliano, L., Severino, B., Caliendo, G., et al.. (2015). Specificity studies on kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) and effects of osmolytes and glycosaminoglycans on its peptidase activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1854: 73–83, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.10.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Pampalakis, G., Zingkou, E., Panagiotidis, C., and Sotiropoulou, G. (2021). Kallikreins emerge as new regulators of viral infections. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78: 6735–6744, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-021-03922-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pejler, G. (2020). Novel insight into the in vivo function of mast cell chymase: lessons from knockouts and inhibitors. J. Innate Immun. 12: 357–372, https://doi.org/10.1159/000506985.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Prassas, I., Eissa, A., Poda, G., and Diamandis, E.P. (2015). Unleashing the therapeutic potential of human kallikrein-related serine proteases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 14: 183–202, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4534.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Raju, I., Kaushal, G.P., and Haun, R.S. (2016). Epigenetic regulation of KLK7 gene expression in pancreatic and cervical cancer cells. Biol. Chem. 397: 1135–1146, https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2015-0307.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Sales, K.U., Masedunskas, A., Bey, A.L., Rasmussen, A.L., Weigert, R., List, K., Szabo, R., Overbeek, P.A., and Bugge, T.H. (2010). Matriptase initiates activation of epidermal pro-kallikrein and disease onset in a mouse model of Netherton syndrome. Nat. Genet. 42: 676–683, https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.629.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shropshire, T.D., Reifert, J., Rajagopalan, S., Baker, D., Feinstein, S.C., and Daugherty, P.S. (2014). Amyloid β peptide cleavage by kallikrein 7 attenuates fibril growth and rescues neurons from Aβ-mediated toxicity in vitro. Biol. Chem. 395: 109–118, https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2013-0230.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Silva, L.M., Stoll, T., Kryza, T., Stephens, C.R., Hastie, M.L., Irving-Rodgers, H.F., Dong, Y., Gorman, J.J., and Clements, J.A. (2017). Mass spectrometry-based determination of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) cleavage preferences and subsite dependency. Sci. Rep. 7: 6789, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06680-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Skytt, A., Stromqvist, M., and Egelrud, T. (1995). Primary substrate specificity of recombinant human stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211: 586–589, https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1995.1853.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Talieri, M., Mathioudaki, K., Prezas, P., Alexopoulou, D.K., Diamandis, E.P., Xynopoulos, D., Ardavanis, A., Arnogiannaki, N., and Scorilas, A. (2009). Clinical significance of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) in colorectal cancer. Thromb. Haemost. 101: 741–747, https://doi.org/10.1160/th08-07-0471.Search in Google Scholar

The.UniProt Consortium, Martin, M.J., Orchard, S., Magrane, M., Ahmad, S., Alpi, E., Bowler-Barnett, E.H., Britto, R., Bye-A-Jee, H., Cukura, A., et al.. (2023). UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51: D523–D531, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1052.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Uhlen, M., Fagerberg, L., Hallstrom, B.M., Lindskog, C., Oksvold, P., Mardinoglu, A., Sivertsson, A., Kampf, C., Sjostedt, E., Asplund, A., et al.. (2015). Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347: 1260419, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1260419.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Walker, F., Nicole, P., Jallane, A., Soosaipillai, A., Mosbach, V., Oikonomopoulou, K., Diamandis, E.P., Magdolen, V., and Darmoul, D. (2014). Kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) is a proliferative factor that is aberrantly expressed in human colon cancer. Biol. Chem. 395: 1075–1086, https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2014-0142.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Yousef, G.M., Scorilas, A., Magklara, A., Soosaipillai, A., and Diamandis, E.P. (2000). The KLK7 (PRSS6) gene, encoding for the stratum corneum chymotryptic enzyme is a new member of the human kallikrein gene family - genomic characterization, mapping, tissue expression and hormonal regulation. Gene 254: 119–128, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00280-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Yu, Y., Prassas, I., Dimitromanolakis, A., and Diamandis, E.P. (2015). Novel biological substrates of human kallikrein 7 identified through degradomics. J. Biol. Chem. 290: 17762–17775, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m115.643551.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2024-0127).

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- GPI-anchored serine proteases: essential roles in development, homeostasis, and disease

- Revival of the Escherichia coli heat shock response after two decades with a small Hsp in a critical but distinct act

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Proteolysis

- Analysis of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) autolysis reveals novel protease and cytokine substrates

- Broadened substrate specificity of bacterial dipeptidyl-peptidase 7 enables release of half of all dipeptide combinations from peptide N-termini

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- GPI-anchored serine proteases: essential roles in development, homeostasis, and disease

- Revival of the Escherichia coli heat shock response after two decades with a small Hsp in a critical but distinct act

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Proteolysis

- Analysis of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) autolysis reveals novel protease and cytokine substrates

- Broadened substrate specificity of bacterial dipeptidyl-peptidase 7 enables release of half of all dipeptide combinations from peptide N-termini