Broadened substrate specificity of bacterial dipeptidyl-peptidase 7 enables release of half of all dipeptide combinations from peptide N-termini

-

Kana Shirakura

, Yuko Ohara Nemoto

, Haruka Nishimata

Abstract

Dipeptide production mediated by dipeptidyl-peptidase (DPP)4, DPP5, DPP7, and DPP11 plays a crucial role in growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis, a periodontopathic asaccharolytic bacterium. Given the particular P1-position specificity of DPPs, it has been speculated that DPP5 or DPP7 might be responsible for degrading refractory P1 amino acids, i.e., neutral (Thr, His, Gly, Ser, Gln) and hydrophilic (Asn) residues. The present results identified DPP7 as an entity that processes these residues, thus ensuring complete production of nutritional dipeptides in the bacterium. Activity enhancement by the P1′ residue was observed in DPP7, as well as DPP4 and DPP5. Toward the refractory P1 residues, DPP7 uniquely hydrolyzed HX|LD-MCA (X = His, Gln, or Asn) and their hydrolysis was most significantly suppressed in dpp7 gene-disrupted cells. Additionally, hydrophobic P2 residue significantly enhanced DPP7 activity toward these substrates. The findings propose a comprehensive 20 P1 × 20 P2 amino acid matrix showing the coordination of four DPPs to achieve complete dipeptide production along with subsidiary peptidases. The present finding of a broad substrate specificity that DPP7 accounts for releasing 48 % (192/400) of N-terminal dipeptides could implicate its potential role in linking periodontopathic disease to related systemic disorders.

1 Introduction

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a Gram-negative anaerobic and asaccharolytic rod, is considered to be one of the most potent causative factors of severe periodontal diseases and shown as a major cause of tooth loss in adults in developed countries (Holt and Ebersole 2005; Socransky and Haffajee 2002). Furthermore, P. gingivalis infection in the oral cavity has been found to be closely related to systemic diseases, such as type-2 diabetes mellitus (Grossi and Genco 1998; Lalla and Papapanou 2011; Preshaw et al. 2012), atherosclerotic cardiovascular disorder (Genco and VanDyke 2010; Tabeta et al. 2014), decreased kidney function (Kshirsagar et al. 2007), rheumatoid arthritis (Detert et al. 2010), and Alzheimer’s disease (Teixeira et al. 2017). Thus, identification of virulence factors related to this bacterium and synthesis of compounds targeting them will lead to potent strategies for prevention and treatment of these diseases.

P. gingivalis exclusively utilizes amino acids as the primary carbon and energy sources, making its growth highly dependent on their uptake. Previously reported metabolic analysis findings indicated that nutritional amino acids are preferentially incorporated as dipeptides, but not as single amino acids, in the bacterium (Takahashi and Sato 2001; Takahashi and Sato 2002; Tang-Larsen et al. 1995). It has also been shown that P. gingivalis possesses three types of amino acid/oligopeptide transporters, i.e., serine/threonine transporter (SstT), proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter (Pot), and oligopeptide transporter (Opt) (Nelson et al. 2003). We recently reported that the bacterium preferentially and predominantly takes up dipeptides via Pot, while Opt transports tripeptides. In addition, knockout of the pot gene caused significantly greater growth retardation than opt- and sstT-gene-disrupted strains (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2020). These findings highlight the importance of dipeptide production in the bacterium. In contrast to gingipains, which degrade extracellular substrates (Potempa et al. 1995), DPP activities have been detected in the periplasmic fraction but not in the culture supernatant of P. gingivalis, as shown by subcellular fractionation. This localization suggests their roles in producing nutritional dipeptides within this space (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2014). Immunoelectron microscopy experiments have further revealed the periplasmic localization of DPPs and Pot in the inner membrane, suggesting an integrated amino acid uptake system (Shimoyama et al. 2023).

P. gingivalis dipeptide production is governed by four DPPs, i.e., DPP4 (Banbula et al. 2000), DPP5 (18 Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2014), DPP7 (Banbula et al. 2001), and DPP11 (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2011). DPP activities can be assessed by use of synthetic chromogenic or fluorogenic substrates, including Gly-Pro-4-p-nitroanilide or methycoumaryl-7-amide (MCA) for DPP4, Gly-Phe-MCA for DPP5, and Leu-Asp/Glu-MCA for DPP11. Although the commercially available Met-Leu-MCA has also been used for measurement of DPP7 activity (Rouf et al. 2013a,b), that substrate is degraded by DPP5. Accordingly, we previously established a DPP7-specific substrate, Phe-Met-MCA, which showed a 40-fold higher kcat/KM value and was scarcely hydrolyzed by DPP5 (Nemoto et al. 2018). Use of these DPP-specific substrates enabled quantitative measurements of DPP activities in oral bacteria as well as oral specimens (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022).

The substrate specificity of DPP is primarily defined by the P1 residue, a penultimate amino acid residue from the N-terminus, with previous studies showing DPP4 for Pro (Banbula et al. 2000), DPP5 for hydrophobic amino acids (Beauvais et al. 1997; Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2014), DPP7 for hydrophobic amino acids (Banbula et al. 2001), and DPP11 for acidic amino acids (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2011). Subsite residues such as P2 (N-terminal residue) and P1’ (third residue from N-terminus) were previously thought to have scant effects on DPP activities. However, our previous study found that both DPP7 and DPP11, members of the S46 exopeptidase family, have a preference for hydrophobic P2 amino acid residues (Rouf et al. 2013b). In addition, our more recent study indicated that the prime-side residues increase the kcat of DPP7, resulting in a broader P1 specificity than previously considered. For example, DPP7 sequentially releases dipeptides from the N-termini of incretins, i.e., glucagon-like peptide 1 (7–37) (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (52–93) (GIP), thus reducing the half-life of GLP-1 by a factor of seven as compared to DPP4 (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2017, 2022).

Together, those findings demonstrated that DPP activities can be modulated by subsite residues and further raised the following question. Although DPP5 can hydrolyze His-Ala-MCA, can its failure to cleave GLP-1, which possesses the NH2-His7-Ala8-Glu9 sequence, be explained by the effects of prime side residues? Moreover, while the broad P1 specificity of DPP7 including amino acids with a low hydrophobicity index (HI) (Monera et al. 1995), such as Thr (HI = 13), Gly (0), Ser (−5), Gln (−10), and Asn (−28), has been observed with recombinant DPP7 (Hack et al. 2017; Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022), it awaits to be revealed whether these cleavages truly occur in P. gingivalis. In this context, it is considered crucial to elucidate the properties of DPPs in relation to these refractory P1 amino acids.

The present study was conducted to examine the effects of the P2, P1, P1′, and P2′ positions of amino acids of substrates on the activities of DPP7, as well as DPP4 and DPP5 with use of a two-step hydrolyzing method (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022). A sophisticated collaboration between DPP5 and DPP7 was revealed, culminating in a fuller understanding of the comprehensive coverage of the 20 × 20 amino acid matrix at the P1 and P2 positions by the four DPPs and relevant peptidases.

2 Results

2.1 Activity enhancement by prime-side amino acids for DPP4, DPP5, and DPP7

To investigate the effects of the P1′ residue in detail, hydrolysis of HAXD-MCA, where X represents 12 different amino acids, was measured using a two-step method (Figure 1, Table S1). Under the conditions employed, when the examined DPP hydrolyzes the substrate into His-Ala and Xaa-Asp-MCA, the latter is readily converted into Xaa-Asp and 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) by an excess amount of DPP11. DPP11 does not hydrolyze tetrapeptidyl substrates, while it exhibits activity exclusively toward Xaa-Asp-MCA. Consequently, hydrolysis of tetrapeptidyl-MCA was attributed to the first-order reaction of the target DPP (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022). However, one might raise a question that the activity of the first-step DPP might be affected by the second-step DPP11 activity. In fact, DPP11 prefers hydrophobic amino acids at the N-terminus (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2011; Rouf et al. 2013b). Thus, we here show the results with HAMD- and HAED-MCA as controls among tetrapeptidyl substrates examined in Figure 1B. The hydrolyzing activity of DPP7 (10 ng) increased dependent on the amount of DPP11 and thereafter reached a plateau over 3 µg. Therefore, we concluded that the DPP7 activity is defined as the plateau stage independent of the DPP11 activity. Consequently, the amount of DPP11 was fixed at 5 µg in the following experiments.

P1′ preference for DPP4, DPP5, and DPP7 (A) The two-step process on the breakdown of HAXD-MCA is shown. Fluorescent AMC group is indicated in blue (B) HAMD- and HAED-MCA were incubated with various amounts of DPP11 in the absence and presence of DPP7 (10 ng) at 37 °C for 30 min (C) His-Ala- and HAXD-MCA were digested by DPP7 (10 ng), or (D) DPP4 (25 ng) and DPP5 (25 ng) in the presence of DPP11 (5 μg) at 37 °C for 30 min. values (mean ± SD, n = 3) shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments (E) replotted hydrolysis findings for His-Ala- and HAED-MCA by DPP4, DPP5, and DPP7 shown in B and C. Values (mean ± SD, n = 3) shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments (F) Relationships of activities for HAXD-MCA between two DPPs were compared. Regression lines for DPP4–DPP5, DPP4–DPP7, and DPP5–DPP7 are y = 1.842x + 178.6 (R2 = 0.104), y = 2.678x + 59.10 (R2 = 0.787), and y = 0.237x + 148.6 (R2 = 0.202), respectively.

As shown in Figure 1C, DPP7 scarcely degraded His-Ala-MCA, while it hydrolyzed HAXD-MCA with P1′ Met, Leu, Ser, Ala, Val, Tyr, Gln, Asn, and Glu to varying degrees. Activities toward substrates with P1′ Lys, Ile, and Phe were minimal (Figure 1C). These results confirmed the previous finding that release of His-Ala from GLP-1 by DPP7 is increased by the presence of an appropriate P1′ residue. In addition, they are the first to show activity enhancement by the P1′ residue in DPP4 and DPP5, both of which belong to the S09 family (Figure 1D). The increase in activity was modest in DPP4 and most prominent with P1′ Met, followed by Leu, Tyr, Gln, and Ser. DPP5 activity was significantly increased with P1′ Ser, and Met, followed by Asn, Leu, and Ala. Therefore, at least towards substrates with P1 Ala, activity enhancement by a P1′ residue was shown to be common among the three DPPs. In addition, despite structural similarities between Leu and Ile, activities toward HALD-MCA were increased in the three DPPs, while those for HAID-MCA were quite low, possibly due to differences in the structural entropy of these side chains (Creamer and Rose. 1992). Similarly, significant differences in activities for HAYD- and HAFD-MCA were found. These results again indicated a substantial role for the P1′-position amino acid in regard to these activities. Furthermore, findings showing that the P1′ residue had the least effect on DPP4 activity likely reflects its strict preference for P1 Pro followed by Ala, in contrast to the more moderate specificities observed for DPP5 and DPP7.

Hydrolytic activities of the three DPPs toward His-Ala- and HAED-MCA that mimic the N-terminal sequence (underlined) of active GLP-1 (NH2-His7-Ala8-Glu9---) are depicted in Figure 1E. These activities matched GLP-1 cleavage efficiency, i.e., DPP5<DPP4<<DPP7, previously demonstrated by MALDI TOF-MS analysis (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022). Taken together, it is concluded that the inactivation potentials of the three DPPs for GLP-1 are primarily determined by their allowance for P1′ Glu. Among the relationships between the activities of DPP4 and DPP5, DPP4 and DPP7, and DPP5 and DPP7 toward the same substrates, only those of DPP4 and DPP7 were closely related (y = 2.678x + 59.10, R2 = 0.787), indicating similar P1′ preferences (Figure 1F). This latter result was unexpected, since DPP4 and DPP7 exhibit completely different P1 specificities and no amino acid sequence similarity (11.6 %). Currently, there is no appropriate explanation for the similar P1′ preferences of DPP4 and DPP7, though the findings clearly indicated no correlation between the HI of P1′ amino acids and their activities.

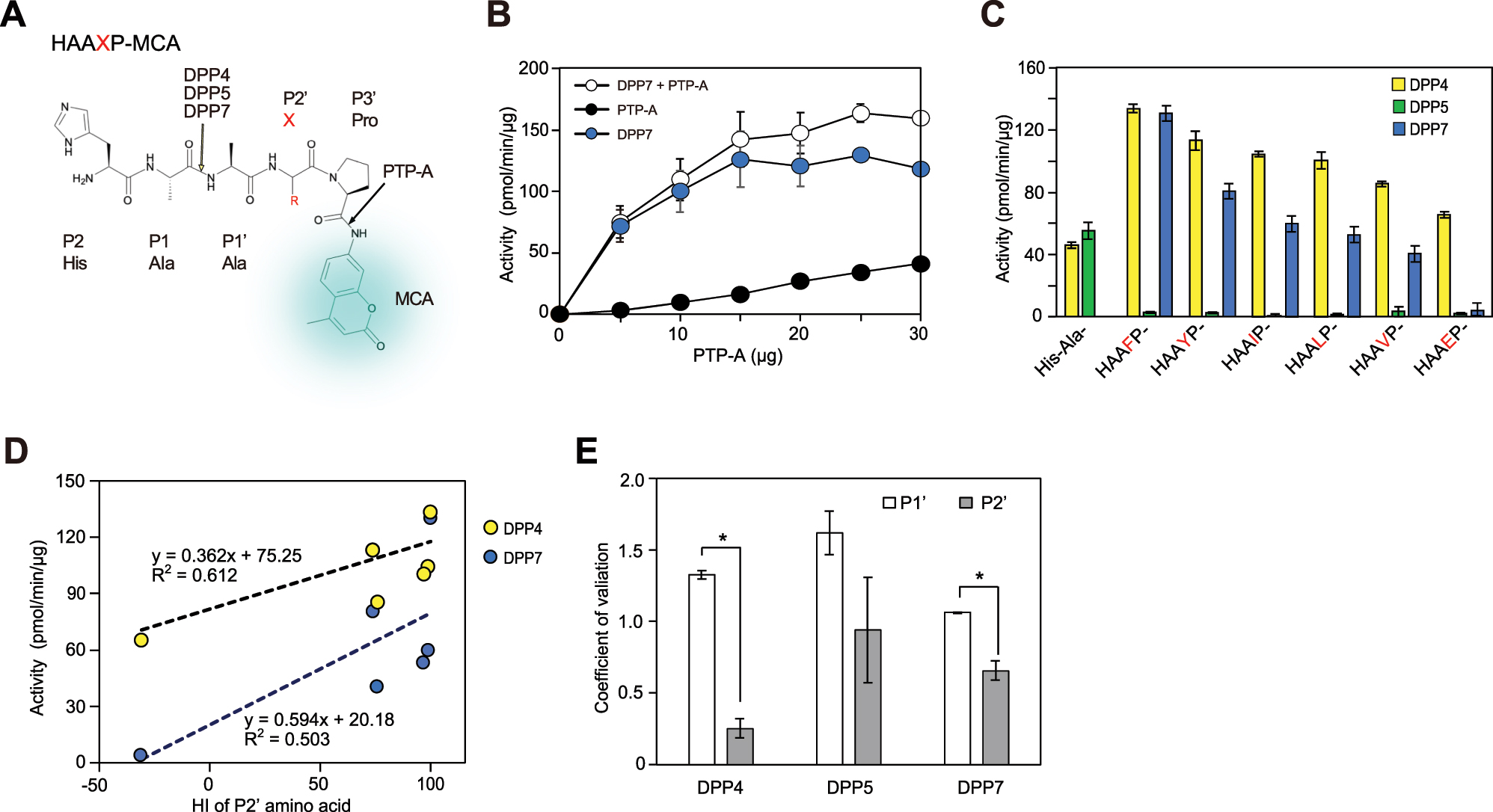

Involvement of the P2′-position residue in DPP activity was examined using a novel method with pentapeptidyl-MCA in combination with P. gingivalis prolyl-tripeptidyl peptidase A (PTP-A) as the second-step enzyme (Figure 2). PTP-A has been shown to specifically recognize the third Pro from the N-terminus and liberate an N-terminal tripeptide (Banbula et al. 1999; Ito et al. 2006). When HA-|-AFP-|-MCA was incubated with DPP7 (100 ng) together with increasing amounts of PTP-A, hydrolysis reached a plateau at 15 μg of PTP-A. As shown in Figure 2C, DPP4 and DPP7 activities toward HAAXP-MCA (X = Phe, Tyr, Ile, Leu, Val, and Glu) were increased as compared to His-Ala-MCA, while HAAEP-MCA was found to be hydrolyzed by DPP4 but minimally by DPP7. Consequently, both DPPs exhibited similar P2′ preferences (y = 1.779x − 117.2, R2 = 0.964), with P2′ Phe showing the greatest level of activity, followed by Tyr, Ile, Leu, and Val. Moreover, a weak correlation between the activities and HI value regarding the P2′ residue was observed for both DPP4 and DPP7 (Figure 2D and E). In contrast, the activity of DPP5 was minimal with all of the substrates examined, suggesting its poor acceptance of P3′ Pro. Taken together, the present results are the first to indicate that the hydrophobic P2′ residue has a positive role in DPP4 and DPP7 activities.

Involvement of P2′ residue in DPP activity, and comparisons of contributions of P1′ and P2′ residues (A) The chemical formula and cleavage sites of HAAXP-MCA used for the two-step method are shown (B) HAAFP-MCA was incubated with PTP-A in the absence (closed circle) or presence (open circle) of DPP7 (0.1 µg). DPP7 activity (blue circle) was calculated by subtraction of hydrolysis in the absence of DPP7 from that in its presence. Values (mean ± SD, n = 3) shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments (C) His-Ala- and HAAXP-MCA were incubated with DPP4, DPP5, or DPP7 (0.1 µg) in the presence of PTP-A (15 µg). Values (mean ± SD, n = 3) shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments (D) specific activities of DPP4 and DPP7 for HAAXP-MCA (X = Phe, Tyr, Ile, Leu, Val, or Glu) plotted against the HI values of P2′-position amino acids (E) coefficient of variation for P1′ and P2′ positions, as described in the text, was calculated using data shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively (mean ± SD (n = 3). * p <0.001.

To examine the contributions of the P1′ and P2′ positions in DPP activity, it was speculated that if a position has an effect on the activity, then it will vary depending on the amino acids at the position. On the other hand, if the position does not affect the activity, the activity amount should remain constant regardless of the amino acids present. Thus, the importance of a substrate position should be evaluated using coefficient of variation, determined based on the standard deviation of activities of substrates with various amino acids divided by the average of specific activities toward those substrates. It was considered that obtained value would be highest for a protease at an essential position, such as the P1 position of GluV8 (Nemoto et al. 2008) and trypsin and the P1′ position of thermolysin. Analyses of the results shown in Figure 1C and D for the P1′ residue, and in Figure 2C for the P2′ residue showed that the coefficient of variation for the P1′ position of the three DPPs was consistently higher than that for the P2′ position (Figure 2E), indicating that the P1′ position has a more significant effect on DPP activity. These findings are reasonable, due to the proximity of the P1′ position to the cleavage site, and also consistent with crystallography data previously presented, which showed that residues at the P1′ position are tightly bound to DPP11, while those at the P2′ position are partially exposed (Bezerra et al. 2017).

2.2 DPP7 responsible for liberation of dipeptides with P1-neutral amino acids and hydrophilic Asn

To investigate DPP activity toward refractory P1 amino acids with an HI value lower than Ala (HI = 41), HXLD-MCA [X indicates His (HI = 8), Gln (−10), or Asn (−28)] was synthesized. In contrast to findings obtained with hydrolysis of HALD-MCA, the three HXLD-MCA compositions were highly resistant to DPP7 (Figure 3B). However, following prolonged incubation for up to 24 h with a large amount (1 μg) of DPP7, gradual hydrolysis of the substrates was observed (Figure 3C), suggesting that DPP7 has potential to hydrolyze those. Under these conditions, DPP7 predominantly hydrolyzed the three substrates, while DPP5 exhibited a lower level of hydrolysis only for HNLD-MCA and DPP4 showed no activity (Figure 3D).

Hydrolysis of HXLD-MCA containing refractory P1 residue (A) Chemical formula and cleavage sites of HXLD-MCA used for the two-step method are shown (B) Dipeptidyl- and HXLD-MCA were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with DPP7 (25 ng for Tyr-Ala- and HALD-MCA, 1 µg for others) in the presence of DPP11 (5 μg) (C) HHLD-, HQLD-, and HNLD-MCA were incubated with DPP11 in the absence (cont) or presence of DPP7 (1 μg) at 37 °C for up to 24 h (D) Tetrapeptidyl-MCA was incubated with DPP4, DPP5, or DPP7 (1 μg) in the presence of DPP11 at 37 °C for 24 h (E) Left. Peptidyl-MCA was incubated with wild-type P. gingivalis cells (10 µl of A600 = 10) in the presence of DPP11. Right (magnified). Values for HHLD-, HQLD-, and HNLD-MCA are shown (F) Substrates were incubated with wild-type P. gingivalis and dpp-gene disrupted cells (10 µl of A600 = 10) in the presence of DPP11. Activities are presented as percent ± SD (n = 3), with those for wild-type P. gingivalis considered to be 100 %. Values (mean ± SD, n = 3) shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments. *1 p <0.05, *2 p <0.005 (as compared to wild-type P. gingivalis).

Hydrolysis of Phe-Met-MCA and tetrapeptidyl-MCA with P1 Ala (HALD-, HAMD-, and HASD-MCA) was observed in P. gingivalis wild-type organisms. In accordance with results of recombinant DPPs, the level of hydrolysis of substrates with P2 His and refractory P1 residue (HHLD-, HQLD-, or HNLD-MCA) were quite low in the wild-type cells (Figure 3E). When hydrolysis was evaluated using dpp-gene disrupted strains (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2011; 2014), the dpp7-gene disrupted strain showed the greatest decrease (Figure 3F). These results suggest that peptide degradation with P1 neutral amino acid and hydrophilic Asn in the bacterium is predominantly mediated by DPP7.

The specific activities of recombinant DPPs were as follows: DPP4, 5,323 ± 1,544 pmol/min/µg (n = 5) and DPP11, 3,778 ± 473 pmol/min/µg (n = 5), and DPP5, 759 ± 342 pmol/min/µg (n = 4) and DPP7, 593 ± 173 pmol/min/µg (n = 8) (Figure S2), indicating higher specific activities for DPP4 and DPP11. These differences are likely due to the highly-restricted P1 residues of DPP4 and DPP11, in contrast to the broader specificities of DPP5 and DPP7. Accordingly, the contents of DPP4, DPP5, DPP7, and DPP11 in the wild-type P. gingivalis cells were calculated to be 0.9 ± 0.0, 2.9 ± 0.1, 9.5 ± 0.3, and 1.4 ± 0.1 ng/μl (A600 = 10), respectively. This distribution is discussed in greater detail later.

2.3 Enhancement of DPP7 activity by subsite residues toward substrates with P1 neutral amino acids and Asn

DPP7 activity was found to be enhanced by hydrophobic P2 residue (Rouf et al. 2013a), thus the activity toward XNLD-MCA with the substitution of P2 His for hydrophobic amino acids was examined (Figure 4). DPP7 activities toward P1 Asn were significantly increased with P2 amino acids with a higher HI value, such as Leu (HI = 97), Phe (100), Met (74), and Tyr (63), as compared to P2 Glu (−31), Ala (41), Asp (−55), and His (8) (Figure 4B Left). Slight increases in these substrates due to hydrophobic P2 residues were also observed with DPP4 and DPP5 (Right). A plot showing the activities against HI of P2-position amino acids confirmed that the activities of DPP4 and DPP5, as well as DPP7 were positively corelated with the hydrophobicity of P2 amino acids, and that DPP7 exhibited higher activities than DPP4 and DPP5 for all of the examined substrates (Figure 4C). These results also reinforced findings indicating that DPP7 primarily targets neutral and hydrophilic P1 amino acids. Notably, the hydrolysis profiles in the bacterial cells for these eight P2 amino acids with XNLD-MCA were indistinguishable from that of recombinant DPP7 (compare Figure 4B–D).

Preference for hydrophobic P2 residue in DPP activities (A) The chemical formula and cleavage sites of XNLD-MCA used for the two-step method are shown (B) XNLD-MCA was incubated with DPP7 (5 ng), DPP4 (40 ng), or DPP5 (40 ng) in the presence of DPP11 (5 μg) at 37 °C for 30 min (C) Linear regression analyses were performed using the log of the DPP activities and HI of P2-amino acid residues. The HI values for Leu, Phe, Met, Tyr, Glu, Ala, Asp, His were 97, 100, 74, 63, −31, 41, −55, and 8, respectively. Regression lines for DPP4, DPP5, and DPP7 are y = 0.0084x + 0.109 (R2 = 0.721), y = 0.0136x + 0.415 (R2 = 0.880), and y = 0.013x + 1.487 (R2 = 0.379), respectively (D) XNLD-MCA was incubated with wild-type P. gingivalis in the absence or presence of DPP11 (5 μg). Values (mean ± SD, n = 3) shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments.

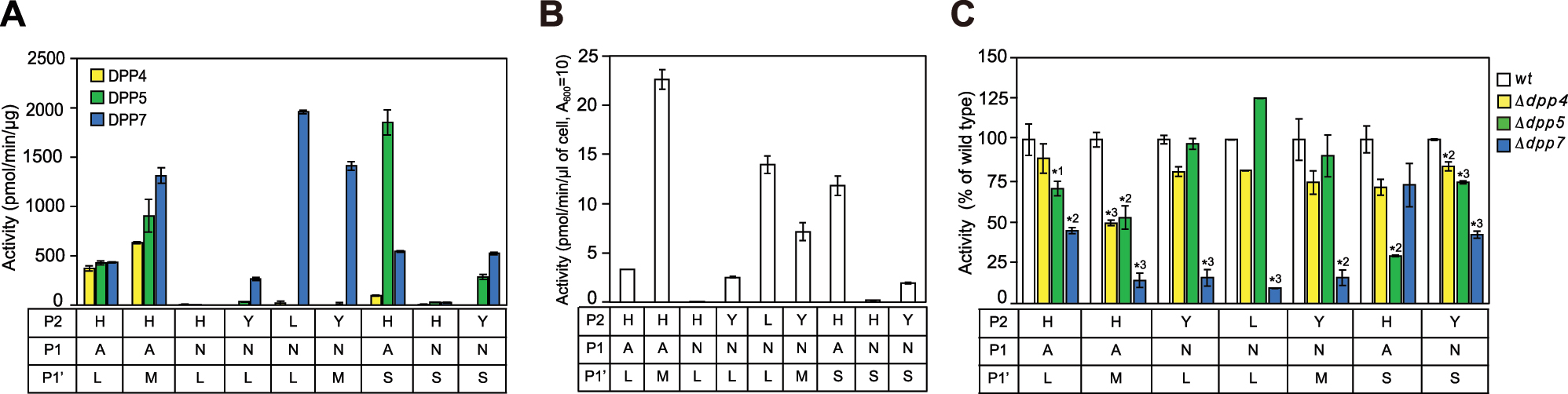

To examine the synergistic effects of P2 and P1′ residues, nine tetrapeptidyl-MCA substrates with P1′ Leu with moderate enhancement of three DPPs were used, with Met found to be most preferable for DPP7 and Ser most preferable for DPP5 (see Figure 1). Those were combined with P1 Ala as a positive control or Asn as a refractory residue, P2 His, Tyr, or Leu, which vary in HI, and all with P2′ Asp (Figure 5A). DPP4 degraded HAMD- and HALD-MCA, as noted above, followed by HASD-MCA, while degradation of the other six substrates was negligible. These findings were understandable, because DPP4 is exclusively specific for P1 Pro and Ala. Furthermore, DPP5 exhibited the highest level of activity toward HASD-MCA, followed by HAMD-, HALD-, and YNSD-MCA, while its activity toward the others was negligible. DPP7 cleaved the substrates with P1 Ala, HAMD-, HASD-, and HALD-MCA, as noted above, and exclusively degraded substrates containing P1 Asn with both P2 and P1′ Leu (LNLD-MCA), and with P2 Tyr and P1′ Met (YNMD-MCA), followed by YNSD- and YNLD-MCA. As a result, the synergistic effect of P2 Tyr and P1′ Met was noted with DPP7, as compared with HNLD-, YNLD-, and YNMD-MCA while that of P2 Tyr and P1′ Ser was noted with DPP5, as compared with YNLD-, HNSD-, and YNSD-MCA though was rather limited.

Synergistic effects of P2 and P1′ residues on DPP activities (A) Tetrapeptidyl-MCA substrates carrying P1 Ala or Asn with P2′ Asp were incubated with DPP4 (5–20 ng), DPP5 (5–40 ng) or DPP7 (5–20 ng) (B) Hydrolyzing activities of wild-type P. gingivalis (0.5–5 µl of A600 = 10) in the presence of DPP11 (5 μg). Values (mean ± SD, n = 3) shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments (C) Tetrapeptidyl-MCA substrates were incubated with wild-type P. gingivalis or dpp-gene disrupted strains (0.5–3 µl of A600 = 10). Results for HNLD- and HNSD-MCA are not shown, as their activities were quite low, while that of HNLD-MCA is presented in Figure 3F. Values represent a typical example of three separate experiments and are presented as percent ± SD (n = 3) of wild-type P. gingivalis, which was considered to be 100 %. *1 p <0.05, *2 p <0.005, *3 p <0.001 (as compared to wild-type P. gingivalis).

Hydrolyzing activities in wild-type P. gingivalis cells were comparable to those observed with recombinant DPPs (compare with findings shown in Figure 5A and B). Among the dpp-gene disrupted strains, dpp7 KO showed the most significant decreases in activity toward substrates containing P1 Asn (LNLD-, YNLD-, YNMD-MCA) (Figure 5C). In addition, a significant loss for HASD-MCA was noted for the dpp5 KO strain. Thus, peptides with P1-hydrophilic amino acid (Asn) were primarily processed by DPP7 in the bacterial cells, though cleavage of substrates with P1 Ala could be shared by DPP5 depending on the subsite residues.

Activity sharing between DPP7 and DPP5 was further compared using XNSD-MCA (X = Leu, Phe, or Tyr). For this comparison, the unique activity of DPP7 for LNLD- and FNLD-MCA was referred to as a positive control, and the quite low activity of both DPPs for HNSD-MCA as a negative control (Figure 6A). Both DPP5 and DPP7 showed significant hydrolysis for LNSD-, FNSD-, and YNSD-MCA as compared with that for HNSD-MCA. Nevertheless, the activities of DPP7 for these substrates were consistently superior to those of DPP5. In accord with these results, hydrolysis of substrates in P. gingivalis was most significantly reduced in the dpp7 gene-disrupted cells (Figure 6B Right). Taken together, it was concluded that peptides carrying penultimate P1 Asn and presumably neural amino acids were predominantly hydrolyzed by DPP7, though the efficiency was low.

Degradation of tetrapeptidyl-MCA carrying P1′ Ser by DPP5 and DPP7, and in P. gingivalis cells (A) Tetrapeptidyl-MCA was hydrolyzed by DPP5 (20 ng) or DPP7 (5 ng) in the presence of DPP11 (5 µg) (B) Specific activities of wild-type P. gingivalis or dpp-gene disrupted strains (A600 = 10) (5 µl for YNSD-MCA, 2 µl for others) in the presence of DPP11 (5 µg). Left. P. gingivalis wild-type cells. Right. Activities are presented as percent ± SD (n = 3), with those of P. gingivalis wild-type considered to be 100 %. Values shown represent a typical example of three separate experiments and are presented as percent ± SD (n = 3) of wild-type P. gingivalis (100 %). *1 p <0.05, *2 p <0.005, *3 p <0.001 (as compared to the wild-type P. gingivalis).

2.4 Examinations of remaining ambiguous amino acid residues to obtain a comprehensive 20 P1 ✕ 20 P2 amino acids matrix

Additional detailed examinations were conducted with specific amino acids to more comprehensively understand the 400 combinations of P1 and P2 dipeptide release.

2.4.1 Degradation of substrates with P2 Asn, and P1 Asn or Thr by DPP7

Although Asn is classified as a hydrophilic amino acid (HI = −28), P2 Asn has been reported to stabilize the DPP7-substrate complex (Nakamura et al. 2021). Hence, examinations were conducted to determine whether tetrapeptidyl-MCA carrying P2 Asn and P1 Asn or Thr, which cover HI from 13 to −28 (see Table 1), is hydrolyzed by DPP7, with substrates with P2 His used as a control. The levels of degradation of HNLD-, HTLD-, HNLD-, and HTMD-MCA by DPP5 and DPP7 were quite low, though notably higher activity was shown with DPP7 as compared with DPP5 (Figure S3A). Findings of substrates where P2 His was substituted with Asn showed an increased activity of DPP7 for NNMD- and NTLD-MCA (Figure S3A). In contrast, the activities of DPP5 for these substrates remained quite low. Analysis of dpp-gene disrupted cells confirmed predominant degradation of NNMD- and NTLD-MCA by DPP7 (Figures S3B, C). These findings demonstrated that peptides with a P1-neutral amino acid, Thr, and hydrophilic Asn are efficiently hydrolyzed by DPP7 when Asn is located at the P2 position. Nevertheless, as compared to the significant effect of P2 Asn, the difference in activity between neutral Thr (HI = 13) and hydrophilic Asn (−28) at the P1 position appeared to be small.

Dipeptide matrix of P1 and P2 amino acids released in P. gingivalis.

| Property | P1 amino acid | HI | P2 amino acid (N terminus) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very hydrophobic | Hydrophobic | Neutral | Hydrophilic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phe | Ile | Trp | Leu | Val | Met | Tyr | Cys | Ala | Thr | His | Gly | Ser | Gln | Arg | Lys | Asn | Glu | Pro | Asp | |||||||||||

| Very Hydrophobic |

Phe | 100 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5 | PTP | 5 | ||||||||

| Ile | 99 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5 | PTP | 5 | |||||||||

| Trp | 97 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5 | PTP | 5 | |||||||||

| Leu | 97 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5 | PTP | 5 | |||||||||

| Val | 76 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5 | PTP | 5 | |||||||||

| Met | 74 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5 | PTP | 5 | |||||||||

| Hydrophobic | Tyr | 63 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5.7 | PTP | 5,7 | ||||||||

| Cys | 49 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5.7 | PTP | 5.7 | |||||||||

| Ala | 41 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5.7 | 5,7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | Rgp | Kgp | 7 | 5.7 | PTP | 5.7 | |||||||||

| Neutral | Thr | 13 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | Rgp | Kgp | 5<7 | 7 | PTP | 7 | ||||||||

| His | 8 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | Rgp | Kgp | 5<7 | 7 | PTP | 7 | |||||||||

| Gly | 0 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7* | Rgp | Kgp | 5<7 | 7* | PTP | 7* | |||||||||

| Ser | −5 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | Rgp | Kgp | 5<7 | 7 | PTP | 7* | |||||||||

| Gln | −10 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | Rgp | Kgp | 5<7 | 7 | PTP | 7 | |||||||||

| Hydrophilic | Arg | −14 | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Rgp | Kgp | Rgp | Rgp | PTP | Rgp | ||||||||

| Lys | −23 | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | Rgp | Kgp | Kgp | Kgp | PTP | Kgp | |||||||||

| Asn | −28 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 5<7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | Rgp | Kgp | 5<7 | 7 | PTP | 7 | |||||||||

| Glu | −31 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | Rgp | Kgp | 11 | 11 | PTP | 11 | |||||||||

| Pro | −46a | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | PTP | 4 | |||||||||

| Asp | −55 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | Rgp | Kgp | 11 | 11 | PTP | 11 | |||||||||

-

DPP4 (4), DPP5 (5), DPP7 (7), and DPP11 (11), as well as Rgp and Kgp are responsible for release of N-terminal dipeptides, while PTP-A (PTP) is proposed responsible for release of tripeptides from nutritional peptides. P1 and P2 amino acids are arranged according to HI value. Typical substrates for DPP4, DPP5, DPP7, and DPP11 are indicated as black cells. Red numbers: cleavage tested as tetrapeptidyl-MCA in this study. Underlined: readily cleaved by DPP7. Asterisk, bottleneck step by DPP7 reported in the previous study (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022). The P2–P1 combinations processed by DPP5 and/or DPP7 are categorized into five groups: Group I (orange column) processed by DPP7; Group II (grey column) processed by DPP5; Group III (sky blue column) processed by either DPP5 or DPP7, with the DPP preference further modulated by prime amino acids; Group IV (green column) dominantly processed by DPP7; and Group V (yellow column) processed by DPP7 at the lowest level of efficiency. aat pH 2.

2.4.2 Hydrophilic P2 Arg, Lys, Glu, and Asp

Given that DPP7 predominantly hydrolyzes substrates with P1 refractory residues and P2 residues classified as very hydrophobic (HI = 100 to 74), hydrophobic (63–41), neutral (13 to −10), or hydrophilic Asn (−28), the remaining four hydrophilic P1 amino acids, Arg, Lys, Glu, and Asp (HI = −14 to −55), were examined (Table 1). Arg and Lys rarely remain inside of peptides, because they are likely cleaved by the endopeptidases Rgps and Kgp, respectively, before entering the periplasmic space of P. gingivalis. For P2 Glu and Asp, DPP7 moderately hydrolyzed ENLD- and DNLD-MCA, while DPP4 and DPP5 activities for those were negligible, as shown in Figure 4B. Additionally, substitution of P2 His of HTMD for Glu or Asp provided ETMD- and DTMD-MCA increased DPP7 activity, while DPP4 and DPP5 activities were minimal toward these substrates (Figure S4). Although a hydrophobic P2 preference is generally observed for substrates with P1 hydrophobic amino acids, that tendency was restricted in amino acids with an HI higher than Ala (41) (Figure 4B, C). Hence, it is currently speculated that activity enhancement of DPP7 by P2 Asp and Glu is likely better suited than neutral residues. Taken together, it was concluded that when Asp and Glu are at the P2 position, DPP7 predominantly hydrolyzes peptides with P1 neutral amino acid.

Finally, Pro, classified as an imino acid, was considered. The Yaa-Pro bond is known to be resistant to many peptidases, including DPPs. To overcome this resistance, P. gingivalis expresses PTP-A, which liberates an Xaa-Yaa-Pro tripeptide from the N-terminus of a peptide. As a result, Pro is never or rarely present at the P2 position of substrates.

3 Discussion

Using integration of the present results with previous findings, a comprehensive 20 P1 × 20 P2 amino acid matrix is proposed (Table 1), which indicates that the four DPPs, along with PTP-A, Rgp, and Kgp, are capable of releasing all combinations of dipeptides in P. gingivalis. The endopeptidases Rgp and Kgp anchored in the outer membrane degrade polypeptides at the Arg-Xaa and Lys-Xaa bonds, respectively (Potempa et al. 1995), while the resulting nutritional oligopeptides pass through the membrane and are processed in the periplasmic space. When the penultimate position (P1 position) from the N-terminus is Pro or Asp/Glu, DPP4 releases the dipeptide Xaa-Pro (Banbula et al. 2000), while DPP11 releases the Xaa-Asp/Glu dipeptides (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2011), respectively. When the third position of peptides from the N-terminus is Pro, PTP-A releases Xaa-Yaa-Pro tripeptides (Banbula et al. 1999). Dipeptides released by Rgp, Kgp, DPP4, and DPP11, as well as tripeptides released by PTP-A are indicated by open cells in Table 1, where specific substrates for DPP4 and DPP11 are marked by black cells.

In addition to the 145 samples processed by DPP4, DPP11, gingipains, and PTP-A, there are 255 dipeptides considered likely to be released by either DPP5 or DPP7, and have been tentatively categorized into five groups (colored cells in Table 1), as noted following.

Group I (orange cells) – 90 combinations of very hydrophobic or hydrophobic amino acids, or hydrophilic Asn at the P2 position with very hydrophobic or hydrophobic P1 amino acids. This group, which includes the DPP7-specific substrate Phe-Met-MCA, shows maximal efficiency for hydrolysis by DPP7. Some of these results are presented in Figure S3, while others have been described previously (Nemoto et al. 2018).

Group II (grey cells) – 42 combinations of neutral or acidic P2 amino acids with very hydrophobic P1 amino acids. This group is predominantly processed by DPP5, as the minimal requirement of hydrophobic P2 amino acid in DPP5 assures this role (Figures 1 and 5). Gly-Phe-MCA, a DPP5-specfic substrate, is located in this group.

Group III (sky blue cells) – 21 combinations of neutral or acidic P2 amino acids with hydrophobic and acidic P1 amino acids. This group is processed by DPP5 or DPP7, with the preference influenced by subsite amino acids, such as the P1′ position. For example, HASD-MCA was found to be predominantly hydrolyzed by DPP5 and HAMD-MCA preferentially by DPP7 (Figures 1, 3, 5, and S1).

Group IV (green cells) – 60 combinations of very hydrophobic or hydrophobic amino acids, or Asn at the P2 position with neutral amino acids or Asn at the P1 position. This group is predominantly processed by DPP7 due to its strong P2 preference for hydrophobic residues and Asn. DPP5 may cleave these substrates with a lower level of efficiency (Figures 4, 5, and 6).

Group V (yellow cells) – 42 combinations of neutral or acidic P2 amino acids with neutral or acidic P1 amino acids. Members of this group are degraded by DPP7, though the extent of hydrolysis is limited (Figure 3).

Taken together, among the 400 combinations of P1 and P2 amino acids, there were 192 (48 %), comprising Groups I, IV, and V, shown to be primarily targeted by DPP7, 42 (10.5 %) in Group II primarily targeted by DPP5, 21 (5.3 %) in Group III primarily targeted by either DPP5 or DPP7, dependent on the subsite residues, 34 (8.5 %) primarily targeted by DPP11, and 19 (4.8 %) primarily targeted by DPP4. Of the remaining combinations, 74 (18.5 %) are targeted by gingipains and 20 (5 %) by PTP-A. Thus, the enzymatic potential of DPPs required for production of all types of dipeptides in P. gingivalis cells is considered to be in the ascending of order of DPP4 (4.8 %), DPP11 (8.5 %), DPP5 (10.5 %), and then a large increase for DPP7 (48 %), even following elimination of 21 (5.3 %) processed by either DPP5 and DPP7. Interestingly, this order coincides with the estimated protein levels of the four DPPs in P. gingivalis cells (Figure S2), as the regression curve between the percent ratio (y axis) and protein level (x axis) of those DPPs was y = 5.04x – 0.56 (R2 = 0.985) (data not shown). This suggests that protein levels of the four DPPs in P. gingivalis bacterial cells are regulated based on demand for dipeptide production.

For many years, DPP activities have generally been measured using synthetic dipeptidyl-p-nitroanilide or dipeptidyl-MCA, with very efficient unveiling of DPP11 and DPP5. However, in our previous study, several substrates, such as Thr-Ser-, Gly-Gly-, and Ala-Asn-MCA, were shown to be scarcely hydrolyzed by any known recombinant DPPs and in P. gingivalis cells (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2014). Should it not be possible to hydrolyze peptides containing P1 neutral amino acids (Thr, His, Gly, Ser, Gln) (HI = 13 to −10) or hydrophilic Asn (−28), then not only is dipeptide production efficiency reduced by 30 % (6 of 20 amino acids), but also a more significant loss occurs due to cessation of C-terminal peptide degradation. In this regard, the present along with our previous (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022) findings showing that the prime-side residues of substrates enhance DPP7 activity and broaden P1 specificity are important. Furthermore, the present evaluations conducted with the new method using pentapeptidyl-MCA and PTP-A revealed a P2′ preference of DPPs. This two-step reaction analysis is a valuable biochemical technique for studying subsite effects that influence protease and peptidase activities. Using that, we recently reported that Staphylococcus aureus GluV8 endopeptidase exerts N-terminal exopeptidase activity, which is assisted by an enhancing effect by hydrophobic P1′ amino acid (Nemoto et al. 2024). Thus, similarities regarding the mechanisms of exopeptidase activities of DPPs and GluV8 are suggested.

The ability of bacterial DPP7 to release nearly half of the 400 dipeptide combinations is noteworthy and suggests that it degrades and/or inactivates a variety of host polypeptides accompanying harmful effects on the host. While DPP4 from periodontopathic bacteria degrades GLP-1 and GIP (35), we previously reported that P. gingivalis DPP7 cleaves them more efficiently and consecutively than DPP4, and also degrades glucagon, oxyntomodulin, and insulin A and B chains. These results are also considered to be in accordance with the finding that among the four DPPs, overexpression of P. gingivalis DPP7 led to the greatest amount of growth retardation in the E. coli host (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2022). Furthermore, the most intrinsic periplasmic proteins in the phylum Bacteroidetes including P. gingivalis have the N-terminally modified residue pyroglutamic acid to acquire DPP resistance, the so-called Q-rule (Szczęśniak et al. 2023), because all DPPs require unmodified N-terminus for hydrolysis. On the other hand, members of the phylum Enterobacteriaceae including E. coli do not possess the Q-rule, thus must be sensitive to DPPs, especially DPP7.

Exploration of the kinship of bacterial DPP7 with systemic diseases is of interest (37, 38). Patients with poor oral hygiene or advanced periodontitis increased risk of oral microorganism bacteremia, and periodontopathic bacteria have been reported to be isolated from the blood of more than one-third of periodontitis patients (Forner et al. 2006). Therefore, under certain conditions, bacterial peptidases entering the bloodstream may degrade bioactive peptides and consequently disrupt physiological systems. In particular, the present findings showing that DPP7 has an ability to release N-terminal dipeptides from nearly half of the P2–P1 combinations imply it as a factor linking periodontopathic disease to related systemic disorders.

In contrast to bacterial DPP4, orthologs of P. gingivalis DPP5, DPP7, and DPP11 are absent in mammals and found exclusively in subgingival bacteria that have potential to cause periodontal diseases (40). DPP4 inhibitors, such as sitagliptin and vildagliptin, are used clinically for treatment of type 2 diabetes to reduce the HbA1c level in affected patients (Gallwitz 2019; Mentlein et al. 1993). Therefore, development of a DPP7-specific inhibitor is eagerly anticipated, as it may function synergistically with DPP4 inhibitors and, moreover, any adverse effects could be minimal for such patients. In addition, bacteria from the Bacteroidetes phylum, which form a large part of the gut microbiota, possess DPP7 (Rouf et al. 2013a). It is thus considered that additional investigations of the potential role of gastrointestinal bacterial DPP7 in systemic diseases will be important.

4 Conclusions

The results obtained with the two-step hydrolyzing method demonstrated that bacterial DPP7 can cleave even peptides with refractory P1 amino acids with HI values lower than that of Ala (HI = 41), i.e., neutral amino acids (Thr, His, Gly, Ser, Gln, HI = +13 to −10), and hydrophilic Asn (HI = −28). We propose a 400-combination matrix of dipeptides composed of 20 P1 and 20 P2 amino acids liberated by peptidases in P. gingivalis. Notably, DPP7 is associated with at least 192 (48 %) of the combinations and shown as the most dominant among the four DPPs involved in this process. The broad substrate specificity of bacterial DPP7 implicates that its role is not limited to nutritional dipeptide production in P. gingivalis, but may be extended to breakdown of various bioactive peptides in human hosts.

5 Materials and methods

5.1 Materials

All synthetic peptidase substrates used in the present study are shown in Table S1. t-Butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)-FSR-, Gly-Pro-, Phe-Met-, and Leu-Asp-MCA were purchased from Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan), and Gly-Phe-MCA was obtained from Bachem (Bubendorf, Switzerland). His-Ala-, Tyr-Ala-, and all of the tetra- and penta-peptidyl-MCA substrates were not commercially available, thus were synthesized by Scrum (Tokyo, Japan) at a purity ≥ 90 %.

5.2 Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Construction of P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 derivatives NDP200 (Δdpp4), NDP300 (Δdpp5), NDP400 (Δdpp7), and NDP500 (Δdpp11) was performed as previously described (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2014; Rouf et al. 2013b). P. gingivalis strains were grown anaerobically at 37 °C (80 % N2, 10 % CO2, 10 % H2) in Anaerobic Bacterial Culture Medium broth (EIKEN Chemical, Tochigi, Japan) supplemented with 0.5 μg/ml of menadione. Appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline) were added for cultures of dpp-gene deleted strains. P. gingivalis cells were harvested in the early stationary phase and washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.3, then suspended in PBS for adjustment to 10 at A600.

5.3 Expression and purification of recombinant DPPs

Expression plasmids for P. gingivalis DPP4 (Rouf et al. 2013a), DPP5 (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2014), DPP7 (22), DPP11 (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2011), and PTP-A (Ito et al. 2006) tagged with a C-terminal hexa-histidine have been previously reported. Escherichia coli XL-1 Blue cells carrying an expression plasmid were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 75 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C overnight. After addition of two volumes of fresh media, recombinant proteins were induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 30 °C for 4 h, then purified from the bacterial cell lysate using TALON affinity chromatography, as previously described (Ohara-Nemoto et al. 2011). A previous report noted that recombinant PTP-A was not adsorbed to a TALON metal affinity resin (Clontech Lab. Inc., CA, USA) for an unknown reason (29), thus PTP-A purification was performed by chromatography using DEAE-Toyopearl 650 M (TOSOH, Tokyo, Japan), with recombinant PTP-A purity shown by SDS-PAGE results to be approximately 90 %.

5.4 Peptidase activity determination

The reaction was started by addition of recombinant DPPs (0.5–100 ng) or a bacterial cell suspension (1–5 μl) in a reaction mixture (200 µl) composed of 50 mM Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, and 20 µM peptidyl-MCA. All reactions were performed at 37 °C. For two-step measurements, target DPP (5–100 ng) or bacterial cells (0.5–1 µl of A600 = 10) were added in the presence of an excess amount of DPP11 (5 µg) or PTP-A (15 µg) as the second enzyme, unless otherwise stated. After 30 min, fluorescence intensity was measured with excitation at 380 nm and emission at 460 nm, while details for prolonged reactions are presented in Figure 3. Decomposition of the substrate up to 10 % could be determined as a first-order reaction. Rgp, DPP4, DPP5, DPP7, and DPP11 activities in P. gingivalis cells (0.5–10 µl) were determined using Boc-FSR-, Gly-Pro-, Gly-Phe-, Phe-Met-, and Leu-Asp-MCA, respectively. DPP4, DPP5, and DPP7 activities for the various dipeptidyl-MCA substrates examined were determined using the conditions noted above, with an excess amount of the second peptidase utilized to adjust the measuring conditions in accordance with the other samples.

5.5 Protein concentration

Concentrations of the purified proteins were determined using Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye (Bio-Rad) with BSA as the standard.

5.6 Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test with Bonferonni correction. P values less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Funding source: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

Award Identifier / Grant number: JP22K17045

Award Identifier / Grant number: JP23K09125

Award Identifier / Grant number: JP23K09461

Award Identifier / Grant number: JP23K11199

Abbreviations

- AMC

-

7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- Boc

-

t-butyloxycarbonyl-

- DPP

-

dipeptidyl-peptidase

- GIP

-

glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (52–93)

- GLP-1

-

glucagon-like peptide 1 (7–37)

- HI, hydrophobicity index

-

Kgp, Lys-gingipain

- MCA

-

4-methycoumaryl-7-amide

- Opt

-

oligopeptide transporter

- Pot

-

proton-dependent oligopeptide transporter

- PTP-A

-

prolyl-tripeptidyl-peptidase A

- Rgp

-

Arg-gingipain

- SstT

-

serine/threonine transporter.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the assistance of Dr. H. Kondo (Nagasaki University) with statistical analysis.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: KS, MS, YS, and MNS determined the conditions for the two-peptidase combination method, and performed measurements of peptidase activities. YS, TKN, and YON performed expression and purification of DPPs, and culturing of P. gingivalis cells. KI performed initial gene cloning and recombinant expression of PTP-A. TKN, HN, MNS, and NT obtained funding. YON performed gene cloning, and creation of the gene-disrupted strains. TKN designed and directed the research project, and co-wrote the article with all of the authors.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: JSPS KAKENHI grants (JP23K09125 to T.K·N., 22K17045 to M.N.-S., JP23K09461 to H·N., JP23K11199 to N.T.).

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Banbula, A., Bugno, M., Goldstein, J., Yen, J., Nelson, D., Travis, J., and Potempa, J. (2000). Emerging family of proline-specific peptidases of Porphyromonas gingivalis: purification and characterization of serine dipeptidyl peptidase, a structural and functional homologue of mammalian prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Infect. Immun. 68: 1176–1182, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.68.3.1176-1182.2000.Search in Google Scholar

Banbula, A., Yen, J., Oleksy, A., Mak, P., Bugno, M., Travis, J., and Potempa, J. (2001). Porphyromonas gingivalis DPP-7 represents a novel type of dipeptidylpeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 6299–62305, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M008789200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Banbula, A., Mark, P., Bugno, M., Sibberring, J., Dubin, A., Nelson, D., Travis, J., and Potempa, J. (1999). Prolyl tripeptidyl peptidase from Porphyromonas gingivalis. A novel enzyme with possible pathological implications for the development of periodontitis. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 9246–9252, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.274.14.9246.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Beauvais, A., Monod, M., Debeaupuis, J.P., Diaquin, M., Kobayashi, H., and Latge, J.P. (1997). Biochemical and antigenic characterization of a new dipeptidyl-peptidase isolated from Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 6238–6244, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.10.6238.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bezerra, G.A., Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Cornaciu, I., Fedosyuk, S., Hoffmann, G., Round, A., Márquez, J.A., Nemoto, T.K., and Djinović-Carugo, K. (2017). Bacterial protease uses distinct thermodynamic signatures for substrate recognition. Sci. Rep. 7: 2848, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017–03220-y.10.1038/s41598-017-03220-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Creamer, T.P. and Rose, G.D. (1992). Side-chain entropy opposes α-helix formation but rationalizes experimentally determined helix-forming propensities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89: 5937–5941, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.13.5937.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Detert, J., Pischon, N., Burmester, G.R., and Buttgereit, F. (2010). The association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease. Arthritis Res. Ther. 12: 218, https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3106.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Forner, L., Larsen, T., Kilian, M., and Holmstrup, P. (2006). Incidence of bacteremia after chewing, tooth brushing and scaling in individuals with periodontal inflammation. J. Clin. Periodontol 33: 401–407, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00924.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Gallwitz, B. (2019). Clinical use of DPP-4 inhibitors. Front. Endocrinol. 10: 389 https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.008930Search in Google Scholar

Genco, R.J. and VanDyke, T.E. (2010). Prevention: reducing the risk of CVD in patients with periodontitis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7: 479–480, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2010.120.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Grossi, S.G. and Genco, R.J. (1998). Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a two-way relationship. Ann. Periodontol. 3: 51–61, https://doi.org/10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.51.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hack, K., Renzi, F., Hess, E., Lauber, F., Douxfils, J., Dogné, J.M., and Cornelis, G.R. (2017). Inactivation of human coagulation factor X by a protease of the pathogen Capnocytophaga canimorsus. J. Thromb. Haemost. 15: 487–499, https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13605.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Holt, S.C. and Ebersole, J.L. (2005). Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: the ‘red complex’, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontol 38: 72–122 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00113.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ito, K., Nakajima, Y., Xu, Y., Yamada, N., Onohara, Y., Ito, T., Matsumoto, F., Kabashima, T., Nakayama, K., and Yoshimoto, T. (2006). Crystal structure and mechanism of tripeptidyl activity of prolyl tripeptidyl aminopeptidase from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Mol. Biol. 362: 228–240 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.083.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kshirsagar, A.V., Offenbacher, S., Moss, K.L., Barros, S.P., and Beck, J.D. (2007). Antibodies to periodontal organisms are associated with decreased kidney function: the dental atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Blood Purif 25: 125–132, https://doi.org/10.1159/000096411.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lalla, E. and Papapanou, P.N. (2011). Diabetes mellitus and periodontitis: a tale of two common interrelated diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 7: 738–748, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.106.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mentlein, R., Gallwitz, B., and Schmidt, W.E. (1993). Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV hydrolyses gastric inhibitory polypeptide, glucagon-like peptide-1(7-36)amide, peptide histidine methionine and is responsible for their degradation in human serum. Eur. J. Biochem. 214: 829–835, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17986.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Monera, O.D., Sereda, T.J., Zhou, N.E., Kay, C.M., and Hodges, R.S. (1995). Relationship of sidechain hydrophobicity and a-helical propensity on the stability of the single-stranded amphipathic α-helix. J. Peptide Sci. 1: 319–329, https://doi.org/10.1002/psc.310010507.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nelson, K.E., Fleischmann, R.D., DeBoy, R.T., Paulsen, I.T., Fouts, D.E., Eisen, J.A., Daugherty, S.C., Dodson, R.J., Durkin, A.S., Gwinn, M., et al.. (2003). Complete genome sequence of the oral pathogenic Bacterium porphyromonas gingivalis strain W83. J. Bacteriol. 185: 5591–5601, https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.185.18.5591-5601.2003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nakamura, A., Suzuki, Y., Sakamoto, Y., Roppongi, S., Kushibiki, C., Yonezawa, N., Takahashi, M., Shida, Y., Gouda, H., Nonaka, T., et al.. (2021). Structural basis for an exceptionally strong preference for asparagine residue at the S2 subsite of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia dipeptidyl peptidase 7. Sci. Rep. 11: 7929, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86965-x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Nemoto, T.K., Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Ono, T., Kobayakawa, T., Shimoyama, Y., Kimura, S., and Takagi, T. (2008). Characterization of the glutamyl endopeptidase from Staphylococcus aureus expressed in Escherichia coli. FEBS J. 275: 573–587, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06224.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nemoto, T.K., Ono, T., and Ohara-Nemoto, Y. (2018). Establishment of potent and specific synthetic substrate for dipeptidyl-peptidase 7. Anal. Biochem. 548: 78–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2018.02.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nemoto, T.K., Nishimata, H., Shirakura, K., and Ohara-Nemoto, Y. (2024). Potential elevation of exopeptidase activity of Glu-specific endopeptidase I/GluV8 mediated by hydrophobic P1′-position amino acid residue. Biochimie 220: 99–106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2023.12.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Nakasato, M., Shimoyama, Y., Baba, T.T., Kobayakawa, T., Ono, T., Nemoto, T.K., and Kimura, S. (2017). Degradation of incretins and modulation of blood glucose levels by periodontopathic bacterial dipeptidyl peptidase 4. Infect. Immun. 85, https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00277-17.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Shimoyama, Y., Kimura, S., Kon, A., Haraga, H., Ono, T., and Nemoto, T.K. (2011). Asp- and Glu-specific novel dipeptidyl peptidase 11 of Porphyromonas gingivalis ensures utilization of proteinaceous energy sources. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 38115–38127, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M111.278572011.Search in Google Scholar

Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Rouf, S.M.A., Naito, M., Yanase, A., Tetsuo, F., Ono, T., Kobayakawa, T., Shimoyama, Y., Kimura, S., Nakayama, K., et al.. (2014). Identification and characterization of prokaryotic dipeptidyl-peptidase 5 from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 5436–5448, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M113.527333.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Sarwar, M.T., Shimoyama, Y., Kobayakawa, T., and Nemoto, T.K. (2020). Predominant dipeptide incorporation in Porphyromonas gingivalis mediated via a proton-dependent oligopeptides transporter (Pot). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 367: 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnaa204.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Shimoyama, Y., Ono, T., Sarwar, M.T., Nakasato, M., Sasaki, M., and Nemoto, T.K. (2022). Expanded substrate specificity supported by P1′ and P2′ residues enables bacterial dipeptidyl-peptidase 7 to degrade bioactive peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 298: 101585, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101585.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Potempa, J., Pike, R., and Travis, J. (1995). The multiple forms of trypsin-like activity present in various strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis are due to the presence of either Arg-gingipain or Lys-gingipain. Infect. Immun. 63: 1176–1182, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.63.4.1176-1182.1995.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Preshaw, P.M., Alba, A.L., Herrera, D., Jepsen, S., Konstantinidis, A., Makrilakis, K., and Taylor, R. (2012). Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia 55: 21–31, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2342-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rouf, S.M.A., Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Hoshino, T., Fujiwara, F., Ono, T., and Nemoto, T.K. (2013a). Discrimination based on Gly and Arg/Ser at position 673 between dipeptidyl-peptidase (DPP) 7 and DPP11, widely distributed DPPs in pathogenic and environmental Gram-negative bacteria. Biochimie 95: 824–832, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2012.11.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Rouf, S.M.A., Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Ono, T., Shimoyama, Y., Kimura, S., and Nemoto, T.K. (2013b). Phenylalanine664 of dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) 7 and phenylalanine671 of DPP11 mediate preference for P2-position hydrophobic residues of a substrate. FEBS Open Bio 3: 177–181, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fob.2013.03.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shimoyama, Y., Sasaki, D., Ohara-Nemoto, Y., Nemoto, T.K., Nakasato, M., Sasaki, M., and Ishikawa, T. (2023). Immunoelectron microscopic analysis of dipeptidyl-peptidases and dipeptide transporter involved in nutrient acquisition in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Curr. Microbiol. 80: 106, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-023-03212-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Socransky, S.S. and Haffajee, A.D. (2002). Periodontal microbial ecology. Periodontol. 2000 38: 135−187 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00107.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

Szczęśniak, K., Veillard, F., Scavenius, C., Chudzik, K., Ferenc, K., Bochtler, M., Potempa, J., and Mizgaiska, D. (2023). The Bacteroidetes Q-rule and glutaminyl cyclase activity increase the stability of extracytoplasmic proteins. mBio 14: e0098023, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00980-23.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tabeta, K., Yoshie, H., and Yamazaki, K. (2014). Current evidence and biological plausibility linking periodontitis to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 50: 55–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdsr.2014.03.001.Search in Google Scholar

Takahashi, N. and Sato, T. (2001). Preferential utilization of dipeptides by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Dent. Res. 80: 1425–1429, https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345010800050801.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Takahashi, N. and Sato, T. (2002). Dipeptide utilization by the periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrescens and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 17: 50–54, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0902-0055.2001.00089.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Tang-Larsen, J., Claesson, R., Edlund, M.B., and Carlsson, J. (1995). Competition for peptides and amino acids among periodontal bacteria. J. Periodont. Res. 30: 390–395, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.1995.tb01292.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Teixeira, F.B., Saito, M.T., Matheus, F.C., Prediger, R.D., Yamada, E.S., Maia, C.S.F., and Lima, R.R. (2017). Periodontitis and Alzheimer’s disease: a possible comorbidity between oral 495 chronic inflammatory condition and neuroinflammation. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9: 327, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00327.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2024-0156).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- GPI-anchored serine proteases: essential roles in development, homeostasis, and disease

- Revival of the Escherichia coli heat shock response after two decades with a small Hsp in a critical but distinct act

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Proteolysis

- Analysis of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) autolysis reveals novel protease and cytokine substrates

- Broadened substrate specificity of bacterial dipeptidyl-peptidase 7 enables release of half of all dipeptide combinations from peptide N-termini

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Reviews

- GPI-anchored serine proteases: essential roles in development, homeostasis, and disease

- Revival of the Escherichia coli heat shock response after two decades with a small Hsp in a critical but distinct act

- Research Articles/Short Communications

- Proteolysis

- Analysis of kallikrein-related peptidase 7 (KLK7) autolysis reveals novel protease and cytokine substrates

- Broadened substrate specificity of bacterial dipeptidyl-peptidase 7 enables release of half of all dipeptide combinations from peptide N-termini