Abstract

RNA binding proteins (RBPs) have multiple and essential roles in transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression in all living organisms. Their biochemical identification in the proteome of a given cell or tissue requires significant protein amounts, which limits studies in rare and highly specialized cells. As a consequence, we know almost nothing about the role(s) of RBPs in reproductive processes such as egg cell development, fertilization and early embryogenesis in flowering plants. To systematically identify the RBPome of egg cells in the model plant Arabidopsis, we performed RNA interactome capture (RIC) experiments using the egg cell-like RKD2-callus and were able to identify 728 proteins associated with poly(A+)-RNA. Transcripts for 97 % of identified proteins could be verified in the egg cell transcriptome. 46 % of identified proteins can be associated with the RNA life cycle. Proteins involved in mRNA binding, RNA processing and metabolism are highly enriched. Compared with the few available RBPome datasets of vegetative plant tissues, we identified 475 egg cell-enriched RBPs, which will now serve as a resource to study RBP function(s) during egg cell development, fertilization and early embryogenesis. First candidates were already identified showing an egg cell-specific expression pattern in ovules.

1 Introduction

The generation of a functional organism from a single cell requires the spatially coordinated formation of numerous cell identities involving transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. During embryo development, the amount and activity of gene products is highly regulated e.g. during transcription by transcription factors and DNA accessibility, at the mRNA level by its processing, translation, and degradation, and at the protein level by post-translational modifications and degradation. Genetic studies have identified many transcription regulators involved in egg cell formation and embryogenesis in animals and plants. In the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis), for example, MYB and AGL together with RWP-RK domain-containing transcription factors are involved in the specification of female gametophyte (embryo sac) cells (Hater et al. 2020; Kasahara et al. 2005; Kőszegi et al. 2011; Punwani et al. 2007). Moreover, during megagametogenesis, cellularization of the eight nuclei containing coenocyte depends on the transcription factors MYB119 and MYB64 (Rabiger and Drews 2013), while MYB98 is essential for synergid and AGL61 together with AGL80 for central cell specification (Bemer et al. 2008; Kasahara et al. 2005; Portereiko et al. 2006; Steffen et al. 2008). All five plant-specific RWP-RK domain-containing transcription factors (RKDs) are expressed during ovule development and RKD1 as well as RKD2 are involved in the specification of the egg cell (Erbasol Serbes et al. 2019; Kőszegi et al. 2011; Tedeschi et al. 2017). During zygote formation, WUSCHEL Related Homeobox (WOX) transcription factors WOX2, WOX8 and WOX9 are involved in the establishment of the first embryo axes (Breuninger et al. 2008; Haecker et al. 2004; Palovaara et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2007).

In other model organisms, like Drosophila, Xenopus or mice, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) were shown to act as key regulators during oocyte formation and the first steps of embryogenesis (Jiang et al. 2023; Pushpa et al. 2017), but so far little is known about the role of RBPs during egg cell development, fertilization and early embryogenesis in plants. The RBP ARGONAUTE 9 (AGO9) was shown to be required to inhibit somatic cells surrounding the megaspore mother cell (MMC) to acquire female germ cell fate (Olmedo-Monfil et al. 2010; Petrella et al. 2021; Rodríguez-Leal et al. 2015), but its role in the egg cell remained unclear similar to other egg cell expressed AGOs (Sprunck et al. 2019). A major limitation of further (biochemical) studies is the access to this cell type, which is deeply embedded in the tissue.

At the onset of embryogenesis, it was further shown in plants like Arabidopsis and maize, that maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) of gene expression pattern occurs shortly after fertilization in zygotes (Chen et al. 2017; Dresselhaus and Jürgens 2021; Kao and Nodine 2019; Nodine and Bartel 2012; Zhao et al. 2019), whereby maternal transcripts and proteins are degraded and gradually replaced by products of the zygotic genome, which are necessary for proper embryonic development. In various species, several studies indicated the involvement of RBPs during maternal transcript degradation as well as the activation and silencing of zygotic transcripts during early embryo development (Corley et al. 2020; Deng et al. 2022; Zavortink et al. 2020). This precise control of the available gene products is essential to allow normal progression during embryogenesis in non-plant model organisms, but so far it is not known for plant embryogenesis.

Cell type- and tissue-specific identification of RBPs is possible due to the establishment of RNA interactome capture (RIC), which was first applied to mammalian cell cultures (Baltz et al. 2012; Castello et al. 2012) and represents a powerful tool to identify all RBPs (RBPome) in a given cell or tissue. Since then RIC was applied to many model organisms using, for example, cell cultures (Dvir et al. 2021), but also to analyze the RBPome during maternal to zygote transition in Zebrafish (Despic et al. 2017) or in Drosophila (Sysoev et al. 2016). These studies provided valuable insights into the role of RBP-mediated processes in that developmental stage. In response to the request for a comprehensive RBPs database in plant research, RIC has also been performed in different tissues of Arabidopsis such as leaves (Bach-Pages et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2016), seedlings (Reichel et al. 2016), root cell cultures (Marondedze et al. 2016) or seeds (Sajeev et al. 2022), but not from reproductive tissues or specialized cell types so far.

In the present study, we tried to overcome the above-described limitations to perform RIC on specialized and deeply embedded reproductive cell types by first generating and propagating callus material with egg cell identity as an example. The so-called RKD2-callus was obtained after over-expressing the egg cell-specific RKD2 transcription factor in sporophytic cells (Sprunck et al. 2019). The transcriptome of RKD2-callus was previously reported to possess egg cell-like and early embryo identity (Kőszegi et al. 2011; Sprunck et al. 2019). mRNA interactome capture was then performed in Arabidopsis using the RKD2-callus representing a biochemical accessible resource for egg cell-like tissue. The identified RBPome showed that proteins involved in RNA processes were highly enriched. With 728 identified potential RBPs, this study now provides a valuable resource for future RBP research in egg cell development, zygote formation and early embryogenesis in plants and will serve as a starting point for identifying their possible regulatory role in these processes. Moreover, in addition to RBPs with known RNA-binding domains, this study identified novel candidate RBPs, which can now be tested for direct and indirect binding to RNA and thus serve as a source to identify novel RBPs.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 RNA interactome capture in the egg cell-like RKD2-callus

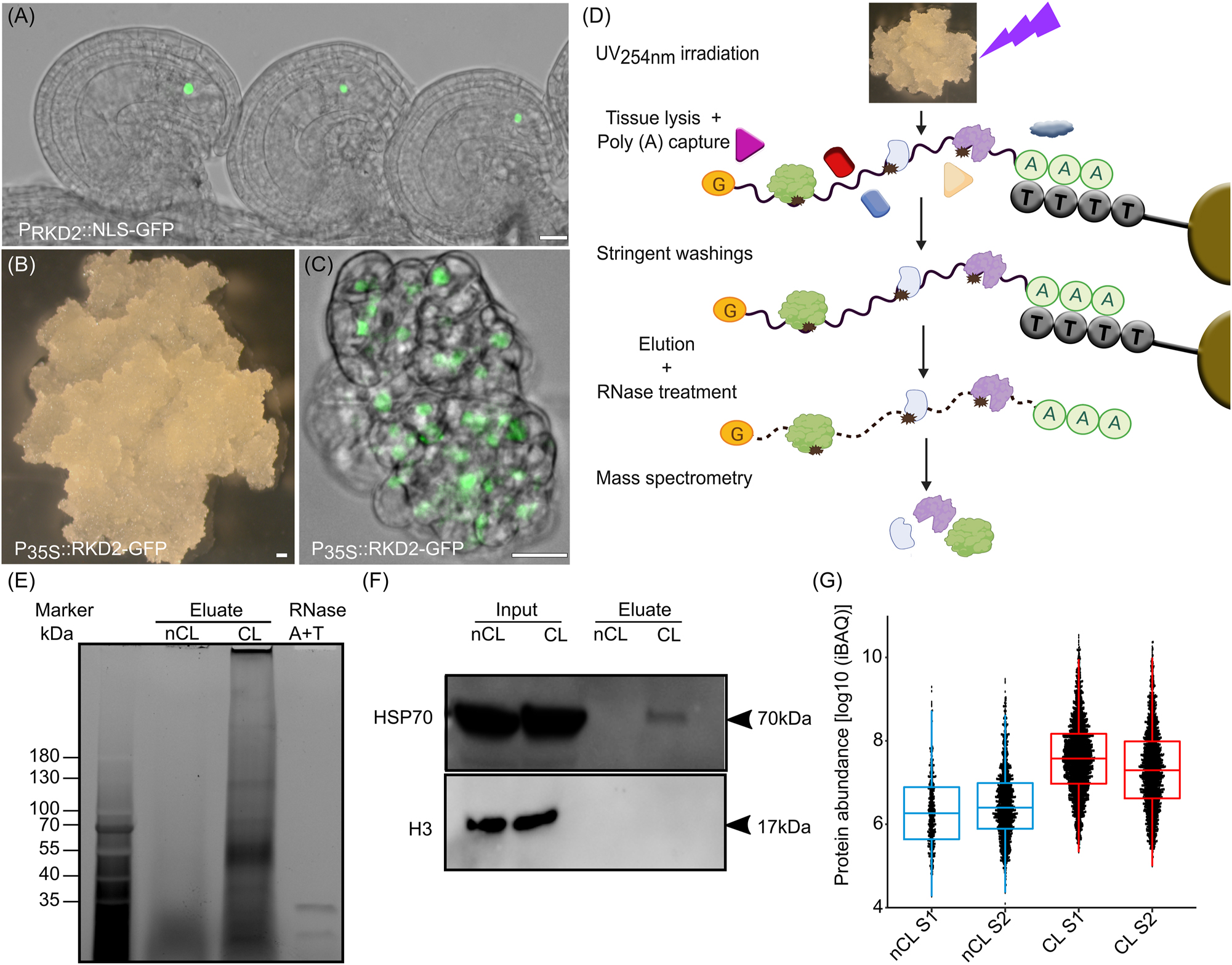

As described above, ectopic expression of the plant-specific RWP-RK domain-containing (RKD) transcription factor RKD2 is sufficient to induce callus formation in seedlings with an egg cell-like transcriptome (Kőszegi et al. 2011). In wild-type plants RKD2 is expressed in the egg cell of the female gametophyte (Figure 1A) and the ectopic expression of an RKD2-GFP fusion protein under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (35Sp:RKD2-GFP) leads to callus formation in sporophytic tissues of transgenic seedlings (Kőszegi et al. 2011; Sprunck et al. 2019). We cultivated and propagated the RKD2-callus (Figure 1B) and verified RKD2-GFP expression in the proliferating cell masses by confocal microscope to control cell identity. As described before, RKD2-GFP was stably expressed in the callus tissue even after years of cultivation (Sprunck et al. 2019) and the fusion protein localizes to the nucleus (Figure 1C). The callus has a white color indicating chloroplast de-differentiation due to egg cell-like cell identity. To systematically and comprehensively identify RNA binding proteins (RBPs) in Arabidopsis egg cells, we performed mRNA interactome capture (RIC) experiments using this RKD2-callus (Figure 1D). About 9500 proteins could be detected in the input data, with 95 % overlap with a previous proteomic analysis of the RKD2 callus (Mergner et al. 2020). The callus was irradiated by ultraviolet (UV) light leading to the formation of covalent bonds between RNAs and proteins. Cell lysis took place under denaturing conditions, so that only covalent bound proteins remained attached to the RNA and protein complexes were dissolved. mRNAs containing poly(A) stretches were isolated using oligonucleotide-deoxythymidine (OligodT) conjugated resin under stringent wash conditions. Since this takes place under denaturing conditions, only proteins that were in direct contact with the mRNA are purified and not entire protein complexes. After the mRNA was eluted from beads, it was degraded using RNase and isolated proteins were identified by quantitative liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Therefore, all identified proteins should represent RBPs (Baltz et al. 2012; Castello et al. 2013; Kwon et al. 2013). Separation of obtained proteins from RIC experiments in an SDS-PAGE showed that UV cross-linking (CL) greatly enhanced protein isolation after poly(A)+ RNA capture (Figure 1E). The protein pattern differed fundamentally from the non-cross-linked (nCL) sample as well as from the input sample. To test whether eluted proteins were enriched in RBPs, we performed Western Blot experiments to detect the known weak RNA binder Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and found that it is present in UV-irradiated samples and absent from the control (Figure 1F). In contrast, common impurities such as histone H3 were not detected in the precipitates by Western Blot (Figure 1F). By LC-MS we identify 889 proteins specifically enriched in the CL samples (Figure 1G and Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, 728 of those 889 proteins were identified by more than one peptide in the LC-MS and represent the Egg Cell-Like RKD2-callus RNA Interactome (ECL-RI; Supplementary Table S2).

RNA interactome capture (RIC) of RBPs expressed in the egg cell-like callus. (A) Expression pattern of the egg cell-specific RKD2 transcription factor in the ovule of Arabidopsis. (B) RKD2-callus induced by ubiquitously expressing RKD2 in seedlings. (C) Protein localization of RKD2 in the nuclei of RKD2-callus cells. (D) Schematic representation of RKD2 callus mRNA interactome capture (RIC). (E) Trichloroethanol (TCE) stained SDS-PAGE gel showing mRNA–protein complexes that were isolated from non-crosslinked (nCL) and cross-linked (CL) RKD2-callus samples. The RNase enzymes used for protein elution are loaded on the right side as control. (F) Western blot to analyze cytosolic heat shock protein HSP70 and histone H3 enrichment in RIC experiments using inputs (whole cell lysates) and eluates of nCL and CL samples, respectively. (G) Boxplots comparing protein abundance in nCL and CL RKD2-callus samples. Scale bars are 20 µm.

2.2 475 candidate RBPs are enriched in the egg cell-like callus

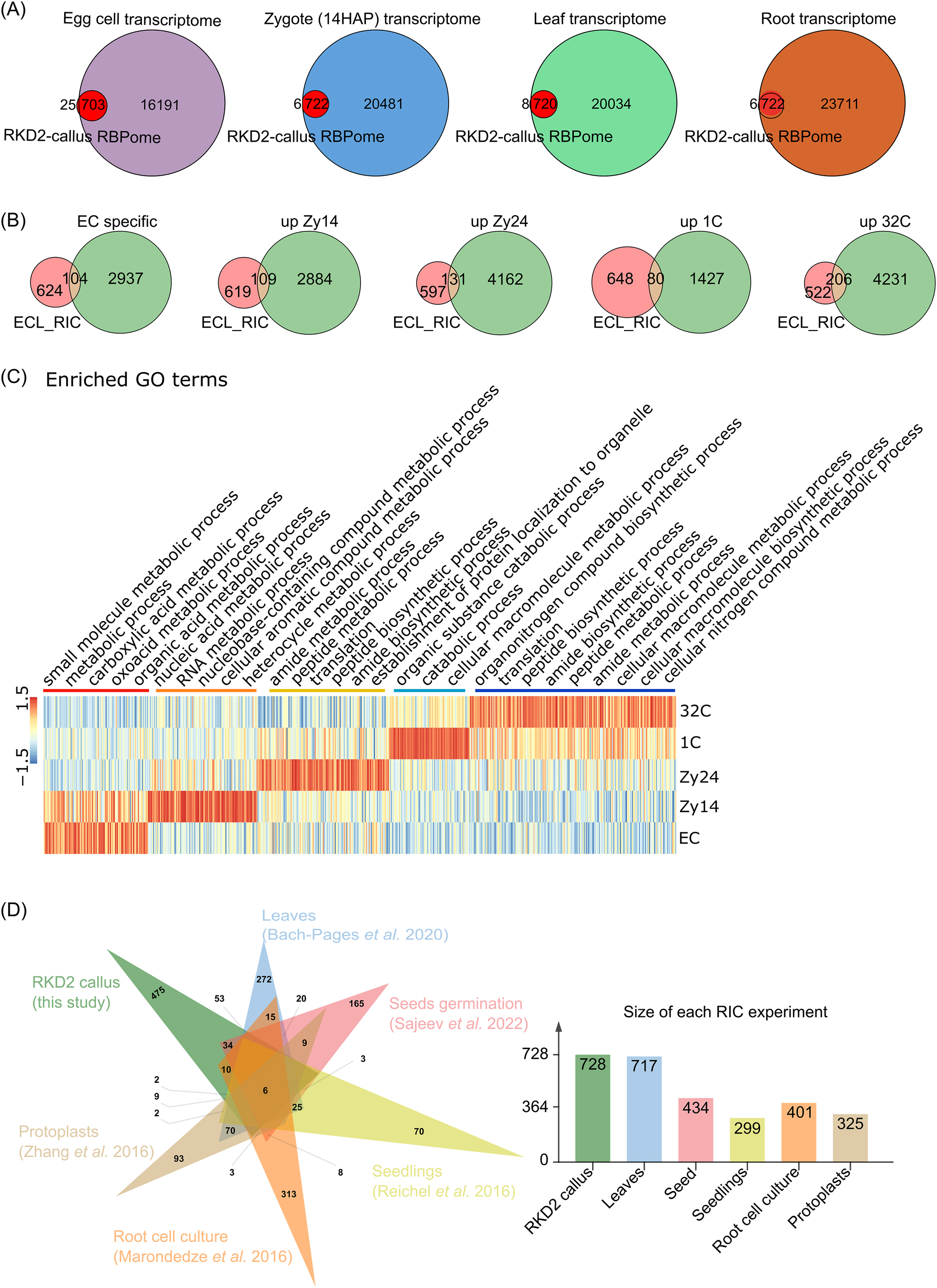

We next addressed the question whether the 728 RBPs isolated from the RKD2-callus are also expressed in Arabidopsis egg cells. Analyzing published Arabidopsis egg cell and zygote transcriptome data (Zhao et al. 2019), transcripts of 703 RBPs (97 %) could be detected in the egg cell and 722 RBP transcripts (99 %) could also be detected at the zygote stage (Figure 2A). This indicates that the ECL-RI likely represents an egg cell/zygote RBPome. To identify stage-specific RBPs, we performed a cluster analysis based on transcriptomic data of Arabidopsis egg cells, zygotes (Zhao et al. 2019) and early embryos (Zhou et al. 2020). 12 different expression patterns of the 728 RBP genes were detected in the datasets (Supplemental Figure S1, Supplementary Table S3). 104 egg cell-enriched RBP transcripts (genes down-regulated after fertilization; Clusters 10 and 11) encode especially proteins involved in metabolic processes, while 109 transcripts (Clusters 2 and 3) that are up-regulated in early zygotes (ZY, 14 h after pollination (HAP)) encode RBPs involved in transcription (Figure 2C).131 RBP genes up-regulated in late zygotes (ZY24HAP) that are represented by Cluster 1, 4 and 12 encode proteins involved in translation. At embryo stages, transcripts that are up-regulated at the one cell embryo (1C) stage (Cluster 8) and in globular embryos (32C; Clusters 6, 7 and 9), respectively, encode RBPs involved in various RNA processes including catabolic, metabolic and protein biosynthesis processes.

475 proteins are enriched in the RBPome of the egg cell-like RKD2 callus. (A) Venn diagrams showing the overlap between the identified RBPome (egg cell-like RKD2-callus RNA interactome; named ECL-RI) and published transcriptomes of egg cell, zygote (14 h after pollination (HAP)), leaf and roots. 97–99 % of the ECL-RI is also present in the transcriptomes of the four cell types and tissues, respectively. (B) Venn diagrams showing the overlap between ECL-RI and published egg cell-enriched transcripts (which are down-regulated after fertilization), zygote-enriched transcripts which are upregulated 14 and 24 h after pollination (HAP) (ZY14 and ZY24), respectively, and transcripts which are upregulated in the one and 32 cell stage embryos (1C and 32C), respectively. (C) Expression heatmap and enrichment analysis of highly expressed ECL-RIC transcripts during zygote development and early embryogenesis according to their GO terms. The color bars indicate relative expression levels. (D) Venn diagrams showing the overlap between ECL-RI and the six available Arabidopsis RNA interactomes. The tissues and references are indicated. The number of identified RBPs in each study is shown on the right side.

In the past years, several studies analyzed the mRNA interactome of Arabidopsis tissue creating individual, partially overlapping RBPomes. For example, 299 RBPs were identified in etiolated seedlings, 717 RBPs in leaves, 325 RBPs in protoplasts, and 434 RBPs in seeds (Figure 2B, Bach-Pages et al. 2017; Marondedze et al. 2016; Reichel et al. 2016; Sajeev et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2016). Comparing the ECL-RI with those five published data sets showed that only six common RBPs are present in all seven data sets analyzed. These represent ribosomal proteins (RPs) (Figure 2B, Supplementary Table S4). It was expected that a big portion of RBPs should overlap between the different tissues, as many RBPs are expected to be involved in general cellular processes including, for example, translation-associated proteins like RPs that represent a major group of the identified proteins (22 % in ECL-RI). However, as RPs show a high diversity in plants and each RP is encoded by three to eight paralogs in Arabidopsis (Barakat et al. 2001; Browning and Bailey-Serres 2015; Martinez-Seidel et al. 2020), we likely identified many egg cell-specific or -enriched gene family members. However, in most cases more than 100 tissue-enriched RBPs are present (Figure 2B). For the RKD2-callus we were able to identify 475 unique RBPs that have not been isolated previously (Figure 2D; Supplementary Table S4). This could have different reasons: on the one hand they could (i) represent genes that are only expressed particularly strongly in the egg cells and/or zygotes or (ii) proteins that show their mRNA binding capacity only in this cellular context. We were therefore wondering whether transcripts encoding the ECL-RI are also present in other tissues analyzed by RIC. Comparing complex tissues like 4-weeks rosette leaf transcriptome (Wang et al. 2022) and root transcriptome data (Ware et al. 2023) with the ECL-RI, transcripts of 720 and 722 RBPs, are also present in leaf and root tissue, respectively. Of course, this analysis does not take protein concentrations into account which strongly influence its appearance in MS studies, and it should be considered that more than 70 % of all genes are expressed in such complex tissues.

2.3 High abundance of annotated RBPs in the mRNA-bound proteome

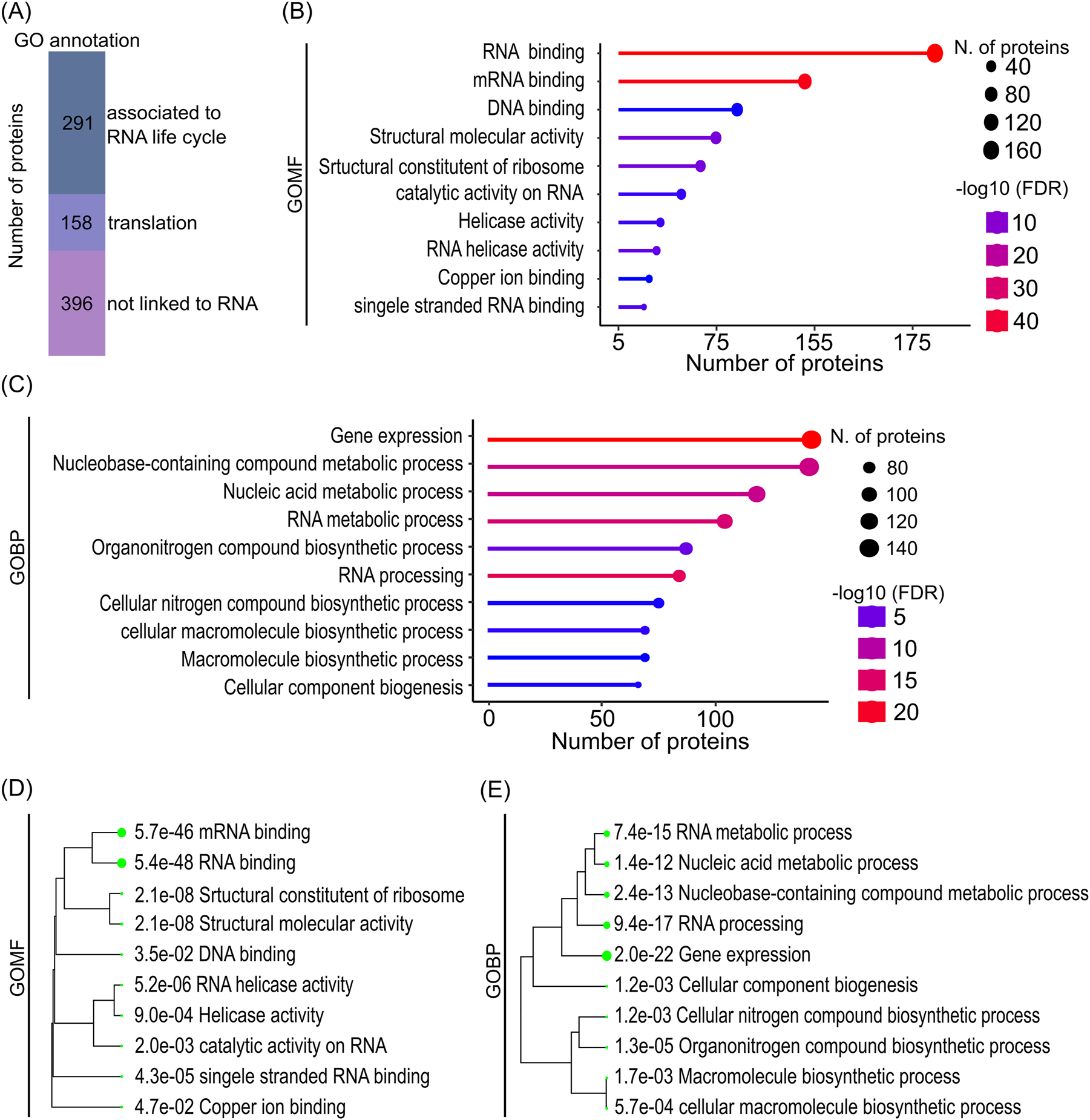

291 of the identified 728 proteins can be associated with the mRNA live cycle and 158 with translation based on their GO term annotation (Figure 3A; Supplementary Table S5). The ribosomal macro-protein complex is crosslinked during translation to the mRNA as well as to the internal rRNA, which stabilizes the entire complex leading to its isolation during RIC even though not every single protein contains an RNA binding motif itself. Those two groups, which can be associated with the RNA live cycle and its translation show a big overlap in their GO annotations and form a group of 332 proteins. 396 proteins were so far not associated with the RNA live cycle and represent egg cell-specific or enriched new RBPs. Analyzing the Gene Ontology (GO) terms based on their molecular function (GOMF) describing the protein activities, it becomes obvious that the majority of isolated RBP, which have a GO term description, can bind to RNA, act on RNA and/or are part of the translation machinery, respectively (Figure 3B). Studying the biological process GO terms (GOBP), the main enrichment can be seen in the GO terms gene expression and RNA processing (Figure 3C). Moreover, of the 10 most enriched GOMF Clusters 9 of 10 are RNA-related (Figure 3D) indicating the high enrichment of proteins involved in RNA biology. The close relationship between the most enriched terms is visible in the clustering tree (Figure 3E) that shows again processes associated with the life cycle of mRNAs.

Enriched GO terms in the ECL-RI RBPome. (A) Proportions of the ECL-RI with gene ontology (GO) annotation related to RNA life cycle, translation and not linked to RNA biology, respectively. (B) GO analysis showing ten of the most significantly enriched molecular function and (C) biological processes terms, respectively. (D) and (E) display the hierarchical clustering of enriched molecular function and biological function terms, respectively. A clear enrichment of RNA-associated functions and processes is visible in the ECL-RI. Diagrams (B–E) were generated with the ShinyGO graphical enrichment online tool (Ge et al. 2020) using LC-MS dataset of the nCL input sample as background (Supplementary Table S6).

2.4 InterPro domains in identified RNA binding proteins of egg cell-like cells

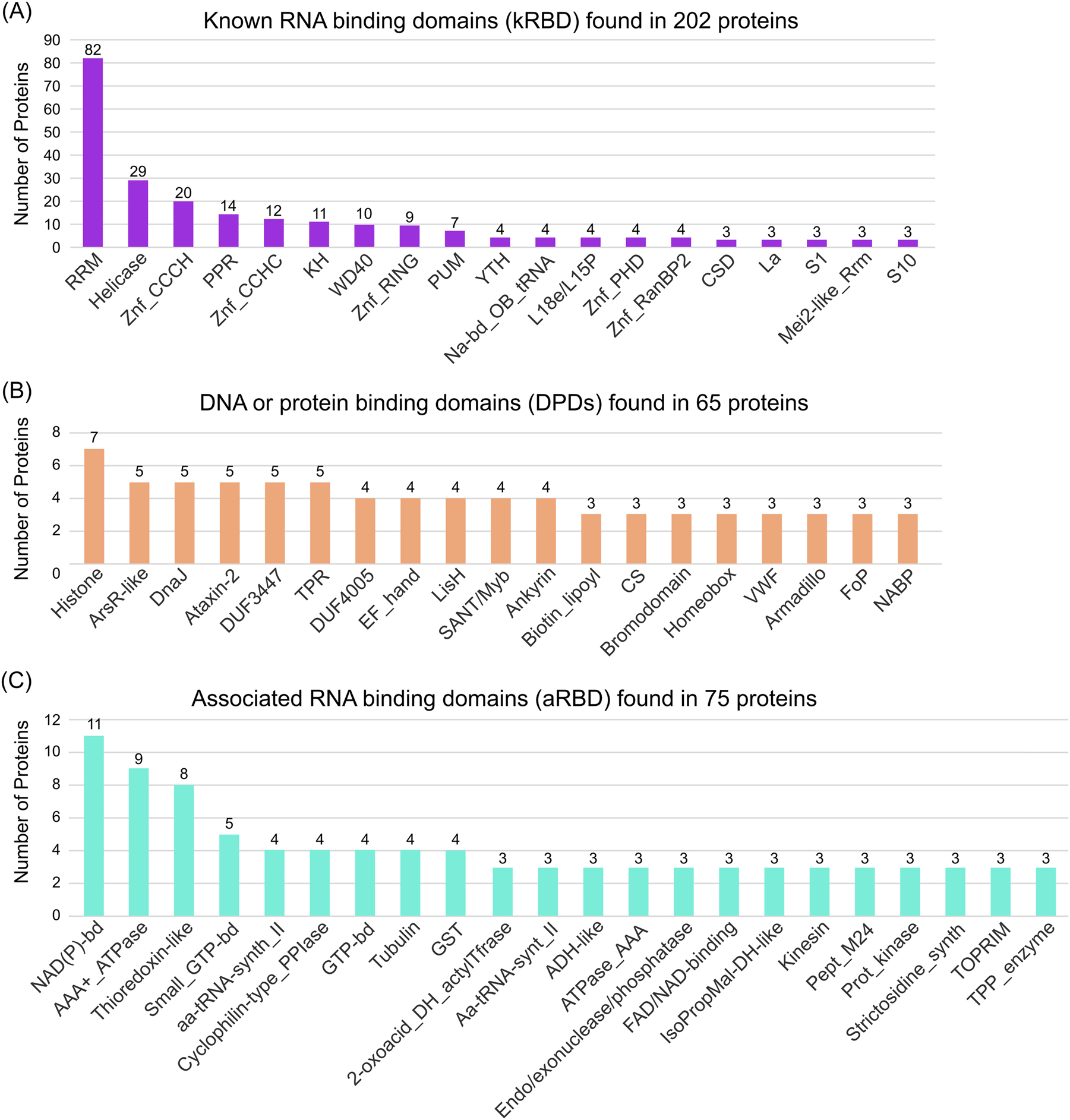

RBPs have different domains to bind to RNA. These RNA binding domains (RBDs) are usually very small (<100 amino acids) and only a few amino acids take part in the interaction with RNA at all. To generate specificity, several (same or different) RBDs within a protein often act together and some RBDs are also capable to mediate protein-protein or protein-DNA interactions in parallel to their RNA binding activity (Cieniková et al. 2015; Corley et al. 2020; Yang 2002). Analysis of the ECL-RI regarding their InterPro classification (Paysan-Lafosse et al. 2023) shows strong enrichment of known RBDs. In total, 1220 different InterPro annotations could be identified in the ECL-RI (Supplementary Table S7). However, only 77 domains are present in at least three proteins, which we further analyzed. For a better overview we sub-grouped the identified domains/repeats into known RBDs (kRBDs), which were described in their InterPro description as RNA binding (Figure 4A), DNA or protein binding domains (DPDs), which are described to permit binding to other molecules such as proteins or DNA (Figure 4B) and into associated RBD (aRBD) which mostly represents enzymatic domains (Figure 4C). 202 proteins contain a kRBD, where one protein can have multiple RBDs of the same or different kind. Within the kRBD group, the RNA Recognition Motif (RRM) is the most abundant RBD in general and also in our ECL-RI dataset. Within the kRBD term helicase group, all proteins of the superfamilies 1 and 2 contain a helicase ATP-binding domain, a C-terminal DEAD/DEAH box helicase domain, Q motif and/or a helicase-associated domain. In total 29 RBPs could be identified that contain all or several of those domains and are therefore classified as helicase. Furthermore, different Zinc Finger (Znf) domains, pentatricopeptide repeats (PPRs), K homology (KH), WD40 repeats, Pumilio (PUM), YT521-B homology (YTH), ribosomal domains L18e/L15P, S1 and S10, La and the Mei2-like_Rrm domains were identified and categorized as kRBD. Among the 58 identified Znf-containing proteins, the CCCH, CCHC, RING, PHD and RanBP2 types were the most abundant. The identification of YTH containing RBPs, a domain that in mammals and plants was shown to bind to N6-methyladenosine (Arribas-Hernández et al. 2021; Li et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014) indicates a potential function of N6-methyladenosine in egg cell mRNAs that likely affects the RNA life cycle including mRNA stability, splicing, and/or translation, and are therefore involved in posttranscriptional regulation.

Occurrence of RNA binding domains (RBDs) in the egg cell-like RBPome. (A–C) Number of proteins containing known (A), potential (B) and associated (C) RNA binding domains, respectively. Only InterPro domains or repeats with at least three hits were considered. kRBD are those domains/repeats, classified as RNA binding domain/repeat in its InterPro description site. DPDs are domains with a known function in protein or DNA binding. aRBD are mostly enzymatic domains and those which could not be classified as kRBD or DPDs. Note that some proteins contain several RBDs of the individual classes.

An interesting aspect of the ECL-RI is the absence of PIWI/PAZ-domain containing RBDs in our RIC data. The PAZ (Piwi Argonaut Zwille)-domain is present in proteins that cleave RNA: DICER and Argonaut (AGO) proteins. Although AGO1, AGO2, AGO4, AGO5 and AGO9 were previously detected in RKD2-callus protein extracts by (Sprunck et al. 2019) and even though we could detect AGO1-7 and AGO9 in our input samples with different intensities (Supplementary Table S6), we could not identify any AGO protein in the ECL-RI. In other RIC data, at least two AGO proteins/PIWI/PAZ-domain containing RBPs could be identified (Bach-Pages et al. 2020; Marondedze et al. 2016; Reichel et al. 2016; Sajeev et al. 2022). AGO9, a protein involved in RNA-directed DNA methylation, is reported to control female gamete formation by restricting the specification of gametophyte precursors to a single subepidermal megaspore mother cell (Olmedo-Monfil et al. 2010). It is further known that AGO1/2 and AGO4-9 are expressed in the egg cell (Jullien et al. 2022; Sprunck et al. 2019), but so far, no phenotype for their function in mature egg cells and during zygote formation is described. The absence of AGO proteins in our ECL-RI suggests that AGO/mRNA interactions are either short-lived in the egg cell or occur at very low levels and are therefore difficult to detect. Alternative, corresponding small RNAs could be induced or AGOs could be activated after fertilization to act on mRNAs, for example, during the transition from maternal-to-zygotic phase.

In the group of DPD we found many domains which are described to have a DNA-binding capacity, such as histones, Ars-like, Sant/Myb, Homeobox, FoP and NABP. Furthermore, we found many domains which are described as protein-protein interaction motifs such as DnaJ, Tetratricopeptide (TPR) repeat, LisH, Ankyrin and Armadillo repeats. It will now be interesting to investigate if these domains also participate in RNA binding in the egg cell.

In total 36 identified proteins contain diverse domains of unknown functions (DUF). However, only DUF3447 and DUF4005 are present in five and four, respectively, different RBPs. DUF3447 (IPR020683) most likely contains divergent Ankyrin repeats, which are classically known as protein interacting domain, but that might also have the potential to bind to RNA. Recently, the binding of DUF4005 to microtubules was shown (Li et al. 2021). We also isolated tubulin and categorized it as aRBD, which can serve as platforms to form RNA-rich liquid-liquid phase-separated compartments (Maucuer et al. 2018). Most of the other aRBD represent enzymatic domains. An example of this category is the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) defining domain which is capable to bind to many different RNAs, including tRNA, numerous mRNAs, rRNA and TNF-a hammerhead ribozyme (Balcerak et al. 2019; Cieśla 2006; Tristan et al. 2011; White and Garcin 2016). We should note that we did not find RBPs containing specific domains or domain arrangements that were enriched in the egg cell-enriched gene expression clusters described above. Finally, we would like to mention that in the InterPro classification intrinsic disordered regions (IDRs) are not listed. IDRs in proteins can play a central role in interacting with RNA molecules. They allow proteins to adapt to different RNA sequences and accommodate structural variations present in RNA molecules (Tamarozzi and Giuliatti 2018; Uversky 2013).

2.5 Validation of egg cell expressed RBPs

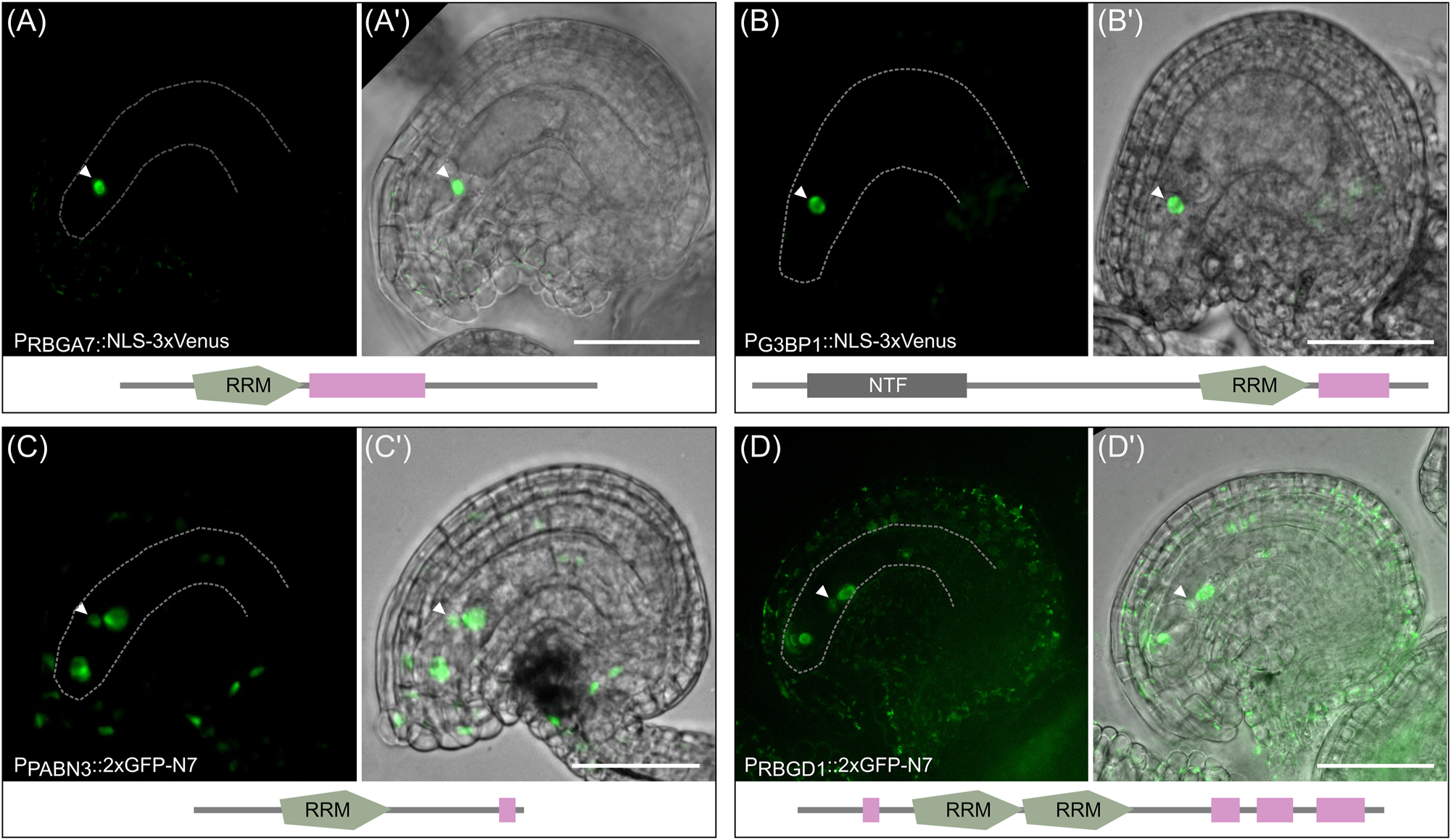

To show that the ECL-RI represents a useful dataset to identify RBP acting in Arabidopsis egg cells, four RBP genes containing RRM domains were selected and checked for their expression pattern in mature ovules by generating promoter-reporter lines. We choose RNA-binding glycine-rich protein A7 (RBGA7; AT5G61030); polyadenylate-binding protein 3 (PABN3; AT5G65260), Ras-GTPase–activating protein SH3-domain–binding protein 1 (G3BP1; AT5G48650) and RNA-binding glycine-rich protein D1 (RBGD1, AT1G17640). RBGA7 contains one RRM domain and a region of low complexity and is part of the ECL-RI but was also identified in leaf RIC experiments (Bach-Pages et al. 2017, 2020). The reporter line shows an egg cell-specific expression pattern in the ovule (Figure 5A). The same pattern was found for G3BP1 which has one RRM domain, one nuclear transport factor motif and one region of low complexity (Figure 5B). Genes encoding PABN3, which contains one RRM domain and a region of low complexity and RBGD1 that contains two RRM domains and four regions of low complexity are expressed in all cells of the embryo sac including the egg cell (Figure 5C and D). RBGD1 is also expressed in surrounding sporophytic tissue and the GFP signal in the egg cell is relatively weak. The expression pattern of these selected genes indicates that the RBPs identified in the presented ECL-RI represent indeed egg cell-expressed RBPs. In conclusion, we have demonstrated that it is possible to identify the RBPome of a highly specialized and deeply embedded cell type and provide a useful resource for further studies to identify functions of so far uncharacterized RBPs during egg cell development, fertilization and early embryo development in plants.

Promoter activity of four RBP genes identified in the ECL-RI. Promoter activity of four exemplary RBP genes in mature ovules of Arabidopsis. The expression study was performed by expressing 3xVenus-NLS fusion proteins in the case of RBGA7 and G3BP1 as well as 2xGFP-N7-NLS fusion proteins in the case of PABN3 and RBGD1 each under the control of their endogenous promoter sequences. Arrowheads mark the nucleus of the egg cell. (A-A′) The promoter of RBGA7 and (B-B′) G3BP1 is specifically active in egg cells. (C-C′) The promoter of PABN3 is active in all cells of the embryo sac (egg cell, synergid cells and central cell) with similar expression strength. (D-D′) The promoter activity of RBGD1 is detected in all cells of the embryo sac with different strength of reporter signals. The lowest GFP signal is visible in the nucleus of the egg cell. A few cells of the surrounding sporophytic tissue also show weak GFP signals. Note that GFP signals were generally very low for RBGD1, thus autofluorescence derived from plastids is also visible in the sporophytic tissue due to longer exposure. GFP channel and the merge image with the brightfield are displayed. Scale bar represents 50 µm.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Plant materials and growth conditions

A. thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) was grown on soil under long day conditions (16 h light at 8500 lux, 21 °C and 65 % humidity). The RKD2-callus was propagated on selection medium as described (Sprunck et al. 2019). Transgenic lines carrying the BAR resistance gene were selected by spraying 0.2 mg/ml glufosinate/0.1 %Tween20 on germinated seedlings.

3.2 Plasmid construction and transgenic plant generation

For promoter-reporter constructs, 2000 bp 5′-upstream of respective start codons were amplified using promoter-specific primers (Table S8). Fragments were cloned into the SPL4pro:3xVENUS-N7 vector (Heisler et al. 2005) using BamHI and XbaI restriction sites to generate PRBGA7::NLS-3xVenus and PG3BP1::NLS-3xVenus constructs. For constructs PPABN3::2xGFP-N7 and PRBGD1::2xGFP-N7, amplified promoter fragments were cloned via the GreenGate cloning system into the vector pGGA000 creating pGGA-PPABN3 and pGGA-PRBGD1. Promoter containing plasmids were assembled with pGGB-meGFP-GAGAGS, pGGC-meGFP-GAGAGS, pGGD007 (linker:NLS (N7)), pGGE_HSP18; pGGF009 (BastaR) into pBLAX000 (Lampropoulos et al. 2013) Transgenic plants were generated by applying the floral dip method (Clough and Bent 1998). Three independent transgenic lines were each analyzed by confocal microscopy.

3.3 RNA interactome capture (RIC)

For UV crosslinking, RKD2-callus containing petri dishes were placed on ice into the Stratalinker® UV Crosslinker 2400 for UV irradiation. The callus was crosslinked three times with 150 mJ/cm2 of UV light at 254 nm wavelength with 30 s pause between irradiations. For the non-crosslinked (nCL) negative control, callus was placed on ice for the same time. After irradiation, callus was immediately placed into liquid nitrogen. Both, CL and nCL samples were processed in parallel. Frozen tissue was transferred into liquid nitrogen prechilled grinding jar and grinded via the Tissue Lyser II (Qiagene; 2 times 30 Hz for 1 min). Between the two grinding steps the grinding jar was chilled with liquid nitrogen. 2 g of tissue powder was mixed with 12 mL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 % LiDS (w/v), 0.02 % IGEPAL, 2.5 % PVP40 (w/v), 1 % B-ME (v/v), 5 mM DTT, protease inhibitor and RNase inhibitor). Lysates were homogenized using the BANDELIN SONOPULS HD 2200 ultrasonic homogenizer (on ice for 2 × 30 s at 30 % intensity; 1 min break). Afterwards lysates were clarified by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) and the supernatant filtered through pluriStrainer® S/30 µm (Cell Strainer). To shear genomic DNA, lysates were passed three times through a narrow needle (27 G). Lysates were cleared again by centrifugation (4000 rpm, 10 min, 4 °C) and mRNA captured from supernatants by activated Oligo(dT) beads. We followed the ptRIC protocol for Oligo(dT) capture described in (Bach-Pages et al. 2020) with small modifications. Oligo(dT) magnetic beads (NEB, cat. no. S1419S) of 800 µl/sample were activated by washing three times with lysis buffer. 5 ml lysate were added to Oligo(dT) and incubated overnight rotating at 4 °C. After hybridization, beads were washed several times. Each washing step was performed with 5 ml of above buffers with gentle rotation for 5 min, followed by 10 min magnet capture. Oligo(dT) beads were washed two times with ice-cold lysis buffer, one time with harsh buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 M LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 % LiDS (w/v), 0.02 % IGEPAL (v/v), 5 mM DTT) at room temperature, two times with buffer I (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 % LiDS (w/v), 0.02 % IGEPAL (v/v), 5 mM DTT), one time with buffer II (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.02 % IGEPAL (v/v), 5 mM DTT), one time with buffer III (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM LiCl,1 mM EDTA, 0.02 % IGEPAL (v/v), 5 mM DTT), and one time with buffer III without detergent (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM LiCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM DTT). Finally, beads were incubated with 450 µl elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA) for 3 min at 55 °C to release poly(A)-tailed RNAs from beads. This eluate containing mRNA-protein complexes were treated with 6 µl RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. R4642) and T1 (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. R1003) mix (RNase A and RNase T1 mixed at equal proportions and diluted 1/100) for 1 h at 37 °C followed by incubation for 15 min at 50 °C.

3.4 Protein concentration and Western blotting

For Western blot analyses, 900 µl eluate was concentrated to 45–60 µl by centrifugation using an Amicon centrifugal filter (Merck) of 3 kDa cut-off. Inputs and eluates were mixed with 6× protein loading buffer and incubated for 10 min at 90 °C. Proteins were separated in a 4–20 % Mini-PROTEAN TGX Stain-Free precast gels (Bio-rad No. 456094) followed by Western Blot. Primary antibodies used were Anti-HSP70 (AS08 347; Agrisera) and Anti-Histone H3 (AS10 710; Agrisera). As secondary antibody Anti-rabbit-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated immunoglobulin G (IgG) (AS09 602; Agrisera) was used.

3.5 SP3 protein purification, digestion and peptide desalting

Protein precipitation and cleanup was performed with a variation of the Single-Pot Solid-Phase-enhanced Sample Preparation (SP3) (Hughes et al. 2014). Therefore, eluates of the RIC pull-downs with a total volume of 800 µl were combined with 100 µl SDS (20 %) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min at 700 rpm shaking for complete protein denaturation. In parallel, 20 µl of SP3 beads per sample (GE, 44152105050250) were washed with 1 ml MilliQ water three times and reconstituted in 20 µl MilliQ water. Beads were mixed with each sample, combined with 1 ml acetonitrile, and again mixed thoroughly by vortexing. Protein aggregation was allowed to occur for 15 min at room temperature before tubes were collected on a magnetic rack for two additional minutes. Beads were washed 4 times with 2 ml EtOH 70 %, spun down and collected again on the magnet to remove any residual ethanol. Protein was digested off the beads in 200 µl digestion buffer (EPPS 50 mM pH 8.5, DTT 10 mM, 0.3 µg trypsin/LysC (Promega V5073)) for 18 h at 37 °C with 700 rpm shaking. Cysteines were alkylated by addition of 15 mM chloroacetamide (CAA) for 1 h before the end of digestion. Beads were collected on the magnet and the supernatant transferred to a fresh tube. Peptides were cleaned up with C18 StageTips and fractionated into three fractions by elution with high pH buffer (50 mM ammonium formate supplemented with 10, 20, 40 % acetonitrile) (Rappsilber et al. 2007). 10 and 40 % acetonitrile containing fractions were combined and samples dried in a SpeedVac to yield two fractions per sample.

3.6 LC-MS analysis

Peptides were dissolved in 10 µl 0.1 % formic acid and injected on a Dionex UltiMate 3000 nano high-performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC) coupled to an Orbitrap Lumos mass spectrometer (both Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptides were loaded on a trap column (100 μm × 2 cm, packed in-house with Reprosil-Gold C18 ODS-3.5 μm resin, Dr. Maisch) and washed for 10 min with 0.1 % formic acid at 5 μl/min flow. Consequently, peptides were eluted onto an analytical column (75 μm × 40 cm, packed in-house with Reprosil-Gold C18 3 μm resin) using a 50 min gradient ranging from 4 to 32 % solvent B (0.1 % formic acid, 5 % DMSO in acetonitrile) in solvent A (0.1 % formic acid, 5 % DMSO) at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min. The MS was operated in a data dependent top 20 method with MS1 scans in the orbitrap at 60,000 resolution, scan range 360–1300, RF lens 50 %, AGC target 4E5, maximum injection time 50 ms. MS2 scans occurred after filtering for monoisotopic peak determination towards ‘Peptide’, intensity threshold 2.5E4, charge state 2–6, a dynamic exclusion of 1 during 20 s with 10 ppm mass tolerance. MS2 isolation occurred with a 1.7 m/z quadrupole isolation window, HCD fragmentation at 30 % and detection in the orbitrap at 30,000 resolutions, AGC target 2.0E5, and 50 ms maximum injection time.

3.7 Mass spectrometric data analysis

Raw files were searched with MaxQuant 2.1.2.0 (Cox and Mann 2008), with default settings except protein and peptide FDR set to 100 %, against the Uniprot A. thaliana proteome (UP00000654, downloaded 2023.03.21). Search results were subsequently rescored with Prosit (Gessulat et al. 2019) and protein FDRs calculated with our recently published Picked Protein FDR approach (The et al. 2022). The RNA-binding proteome was derived from the iBAQ intensities of the RIC experiments using the approach initially described by Marondedze et al. (Marondedze et al. 2016). Briefly, iBAQ intensities in crosslinked samples and non-crosslinked controls, respectively, were median-centered. Proteins without intensity in the non-crosslinked controls and intensity in the crosslinked replicates were considered RNA-binding. For proteins with intensities in the crosslinked replicates and at least one of the non-crosslinked controls, iBAQ values were imputed to apply Student’s T-test and apply the thresholds p < 0.05 and foldchange iBAQcrosslinked/iBAQnoncrosslinked > 2 for calling RNA-binding proteins.

3.8 Bioinformatic analyses of the RBPome

Gene set enrichment analyses were performed via ShinyGO tool (Ge et al. 2020). The RBPome of the RKD2-induced callus gene list was used to compare frequencies of GO terms in either the reference A. thaliana proteome annotation form input proteomics of the RKD2-induced callus. FDR cutoff was default 0.05, GO term selected by FDR < 0.05 and sorted by fold enrichment. Comparison analysis with different RBPome data of other A. thaliana tissues was performed on the jvenn website (Bardou et al. 2014). InterPro Domain annotation and GO Terms of proteins was downloaded from UniPort (Bateman et al. 2023; Paysan-Lafosse et al. 2023). Gene expression data analysed here were downloaded from (Zhou et al. 2020). The data were clustered using the fuzzy c-means (FCM) clustering algorithm implemented in the Bioconductor Mfuzz package (Futschik and Carlisle 2005). The expression heatmap was generated by R package pheatmap (version 1.0.12; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap), and the GO enrichment was performed via AgriGO (Tian et al. 2017).

3.9 Microscopy

Confocal microscopy and image analysis of ovules were performed using a spinning disc microscope system (Visitron system VisiScope) equipped with an HC PL APO 63×/1.3 NA water DIC and 20×/0.75 IMM CORR HC PL APO objective. GFP was excited at 488 nm and emission detected at 500–550 nm.

3.10 Accession numbers

Accessions of all genes and proteins analyzed in this study can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: SFB924

Award Identifier / Grant number: SFB960

Award Identifier / Grant number: FOR5235

Acknowledgments

We thank Verena Pirzer for providing the initial RKD2-callus.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire contents of this manuscript and approved its submission. ABl conceived the original research plan and, together with TD, planned and supervised the experiments. LL performed most of the experiments and analyzed the data together with ABl. JT performed the MS analysis supervised by BK. ABr analyzes the initial RIC experiments using MS. SS provided the starting plant material. GJ and YL helped LL with data analysis. The manuscript was written by ABl with LL and TD and supported by JT and SS.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the German Research Council DFG via Collaborative Research Centers SFB960 to ABr, SS and TD, SFB924 to BK and TD and FOR5235 to TD.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Arribas-Hernández, L., Rennie, S., Köster, T., Porcelli, C., Lewinski, M., Staiger, D., Andersson, R., and Brodersen, P. (2021). Principles of mRNA targeting via the Arabidopsis m6A-binding protein ECT2. eLife 10: 1–33, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.72375.Search in Google Scholar

Bach-Pages, M., Castello, A., and Preston, G.M. (2017). Plant RNA Interactome capture: revealing the plant RBPome. Trends Plant Sci. 22: 449–451, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2017.04.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bach-Pages, M., Homma, F., Kourelis, J., Kaschani, F., Mohammed, S., Kaiser, M., van der Hoorn, R., Castello, A., and Preston, G. (2020). Discovering the RNA-binding proteome of plant leaves with an improved RNA interactome capture method. Biomolecules 10: 661, https://doi.org/10.3390/biom10040661.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Balcerak, A., Trebinska-Stryjewska, A., Konopinski, R., Wakula, M., and Grzybowska, E.A. (2019). RNA–protein interactions: disorder, moonlighting and junk contribute to eukaryotic complexity. Open Biol. 9: 190096, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.190096.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Baltz, A.G., Munschauer, M., Schwanhäusser, B., Vasile, A., Murakawa, Y., Schueler, M., Youngs, N., Penfold-Brown, D., Drew, K., Milek, M., et al.. (2012). The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol. Cell 46: 674–690, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Barakat, A., Szick-Miranda, K., Chang, I.-F., Guyot, R., Blanc, G., Cooke, R., Delseny, M., and Bailey-Serres, J. (2001). The organization of cytoplasmic ribosomal protein genes in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant Physiol. 127: 398–415, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.010265.Search in Google Scholar

Bardou, P., Mariette, J., Escudié, F., Djemiel, C., and Klopp, C. (2014). jvenn: an interactive Venn diagram viewer. BMC Bioinf. 15: 293, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-293.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bateman, A., Martin, M.-J., Orchard, S., Magrane, M., Ahmad, S., Alpi, E., Bowler-Barnett, E.H., Britto, R., Bye-A-Jee, H., Cukura, A., et al.. (2023). UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucl. Acids Res. 51: D523–D531, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1052.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Bemer, M., Wolters-Arts, M., Grossniklaus, U., and Angenent, G.C. (2008). The MADS domain protein DIANA acts together with AGAMOUS-LIKE80 to specify the central cell in Arabidopsis ovules. Plant Cell 20: 2088–2101, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.108.058958.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Breuninger, H., Rikirsch, E., Hermann, M., Ueda, M., and Laux, T. (2008). Differential expression of WOX genes mediates apical-basal Axis formation in the Arabidopsis embryo. Dev. Cell 14: 867–876, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Browning, K.S. and Bailey-Serres, J. (2015). Mechanism of cytoplasmic mRNA translation. Arabidopsis Book 13: e0176, https://doi.org/10.1199/tab.0176.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Castello, A., Fischer, B., Eichelbaum, K., Horos, R., Beckmann, B.M., Strein, C., Davey, N.E., Humphreys, D.T., Preiss, T., Steinmetz, L.M., et al. (2012). Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149: 1393–1406, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Castello, A., Horos, R., Strein, C., Fischer, B., Eichelbaum, K., Steinmetz, LM, Krijgsveld, J., and Hentze, M.W. (2013). System-wide identification of RNA-binding proteins by interactome capture. Nat. Protoc. 8: 491–500, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.020.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Chen, J., Strieder, N., Krohn, N.G., Cyprys, P., Sprunck, S., Engelmann, J.C., and Dresselhaus, T. (2017). Zygotic genome activation occurs shortly after fertilization in maize. Plant Cell 29: 2106–2125, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.17.00099.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cieniková, Z., Jayne, S., Damberger, F.F., Allain, F.H.-T., and Maris, C. (2015). Evidence for cooperative tandem binding of hnRNP C RRMs in mRNA processing. RNA 21: 1931–1942, https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.052373.115.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cieśla, J. (2006). Metabolic enzymes that bind RNA: yet another level of cellular regulatory network? Acta Biochim. Pol. 53: 11–32, https://doi.org/10.18388/abp.2006_3360.Search in Google Scholar

Clough, S.J. and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Corley, M., Burns, M.C., and Yeo, G.W. (2020). How RNA-binding proteins interact with RNA: molecules and mechanisms. Mol. Cell 78: 9–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2020.03.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cox, J. and Mann, M. (2008). MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26: 1367–1372, https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1511.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Deng, M., Chen, B., Liu, Z., Wan, Y., Li, D., Yang, Y., and Wang, F. (2022). YBX1 mediates alternative splicing and maternal mRNA decay during pre-implantation development. Cell Biosci. 12: 12, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-022-00743-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Despic, V., Dejung, M., Gu, M., Krishnan, J., Zhang, J., Herzel, L., Straube, K., Gerstein, M.B., Butter, F., and Neugebauer, K.M. (2017). Dynamic RNA–protein interactions underlie the zebrafish maternal-to-zygotic transition. Genome Res. 27: 1184–1194, https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.215954.116.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Dresselhaus, T. and Jürgens, G. (2021). Comparative embryogenesis in angiosperms: activation and patterning of embryonic cell lineages. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 72: 641–676, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-082520-094112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Dvir, S., Argoetti, A., Lesnik, C., Roytblat, M., Shriki, K., Amit, M., Hashimshony, T., and Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. (2021). Uncovering the RNA-binding protein landscape in the pluripotency network of human embryonic stem cells. Cell Rep. 35: 109198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Erbasol Serbes, I., Palovaara, J., and Groß-Hardt, R. (2019). Development and function of the flowering plant female gametophyte. In: Current topics in developmental biology. Elsevier Inc., Amsterdam, pp. 401–434.10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.11.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Futschik, M.E. and Carlisle, B. (2005). Noise-robust soft clustering of gene expression time-course data. J. Bioinf. Comput. Biol. 03: 965–988, https://doi.org/10.1142/s0219720005001375.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ge, S.X., Jung, D., and Yao, R. (2020). ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants (A Valencia, Ed.). Bioinformatics 36: 2628–2629, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz931.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gessulat, S., Schmidt, T., Zolg, D.P., Samaras, P., Schnatbaum, K., Zerweck, J., Knaute, T., Rechenberger, J., Delanghe, B., Huhmer, A., et al.. (2019). Prosit: proteome-wide prediction of peptide tandem mass spectra by deep learning. Nat. Methods 16: 509–518, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-019-0426-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Haecker, A., Groß-Hardt, R., Geiges, B., Sarkar, A., Breuninger, H., Herrmann, M., and Laux, T. (2004). Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131: 657–668, https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.00963.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hater, F., Nakel, T., and Groß-Hardt, R. (2020). Reproductive multitasking: the female gametophyte. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 71: 517–546, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-081519-035943.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Heisler, M.G., Ohno, C., Das, P., Sieber, P., Reddy, G.V., Long, J., and Meyerowitz, E.M. (2005). Patterns of auxin transport and gene expression during primordium development revealed by live imaging of the Arabidopsis inflorescence meristem. Curr. Biol. 15: 1899–1911, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.052.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hughes, C.S., Foehr, S., Garfield, D.A., Furlong, E.E., Steinmetz, L.M., and Krijgsveld, J. (2014). Ultrasensitive proteome analysis using paramagnetic bead technology. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10: 757, https://doi.org/10.15252/msb.20145625.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Jiang, Y., Adhikari, D., Li, C., and Zhou, X. (2023). Spatiotemporal regulation of maternal mRNAs during vertebrate oocyte meiotic maturation. Biol. Rev. 98: 900–930, https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12937.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Jullien, P.E., Schröder, J.A., Bonnet, D.V., Pumplin, N., and Voinnet, O. (2022). Asymmetric expression of Argonautes in reproductive tissues. Plant Physiol. 188: 38–43, https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiab474.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kao, P. and Nodine, M.D. (2019). Transcriptional activation of Arabidopsis zygotes is required for initial cell divisions. Sci. Rep. 9: 17159, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53704-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kasahara, R.D., Portereiko, M.F., Sandaklie-Nikolova, L., Rabiger, D.S., and Drews, G.N. (2005). MYB98 is required for pollen tube guidance and synergid cell differentiation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 2981–2992, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.105.034603.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kőszegi, D., Johnston, A.J., Rutten, T., Czihal, A., Altschmied, L., Kumlehn, J., Wüst, S.E.J., Kirioukhova, O., Gheyselinck, J., Grossniklaus, U., et al.. (2011). Members of the RKD transcription factor family induce an egg cell-like gene expression program. Plant J. 67: 280–291, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313x.2011.04592.x.Search in Google Scholar

Kwon, S.C., Yi, H., Eichelbaum, K., Föhr, S., Fischer, B., You, K.T., Castello, A., Krijgsveld, J., Hentze, M.W., and Kim, V.N. (2013). The RNA-binding protein repertoire of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20: 1122–1130, https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2638.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lampropoulos, A., Sutikovic, Z., Wenzl, C., Maegele, I., Lohmann, J.U., and Forner, J. (2013). GreenGate – a novel, versatile, and efficient cloning system for plant transgenesis. PLoS ONE 8: e83043, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083043.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Li, Y., Huang, Y., Wen, Y., Wang, D., Liu, H., Li, Y., Zhao, J., An, L., Yu, F., and Liu, X. (2021). The domain of unknown function 4005 (DUF4005) in an Arabidopsis IQD protein functions in microtubule binding. J. Biol. Chem. 297: 100849, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100849.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Li, D., Zhang, H., Hong, Y., Huang, L., Li, X., Zhang, Y., Ouyang, Z., and Song, F. (2014). Genome-wide identification, biochemical characterization, and expression analyses of the YTH domain-containing RNA-binding protein family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 32: 1169–1186, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-014-0724-2.Search in Google Scholar

Marondedze, C., Thomas, L., Serrano, NL, Lilley, K.S., and Gehring, C. (2016). The RNA-binding protein repertoire of Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Rep. 6: 29766, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29766.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Martinez-Seidel, F., Beine-Golovchuk, O., Hsieh, Y.-C., and Kopka, J. (2020). Systematic review of plant ribosome heterogeneity and specialization. Front. Plant Sci. 11: 1–23, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00948.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Maucuer, A., Desforges, B., Joshi, V., Boca, M., Kretov, D., Hamon, L., Bouhss, A., Curmi, P.A., and Pastré, D. (2018). Microtubules as platforms for probing liquid-liquid phase separation in cells: application to RNA-binding proteins. J. Cell Sci. 131: jcs214692, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.214692.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mergner, J., Frejno, M., List, M., Papacek, M., Chen, X., Chaudhary, A., Samaras, P., Richter, S., Shikata, H., Messerer, M., et al.. (2020). Mass-spectrometry-based draft of the Arabidopsis proteome. Nature 579: 409–414, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2094-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nodine, M.D. and Bartel, D.P. (2012). Maternal and paternal genomes contribute equally to the transcriptome of early plant embryos. Nature 482: 94–97, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10756.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Olmedo-Monfil, V., Durán-Figueroa, N., Arteaga-Vázquez, M., Demesa-Arévalo, E., Autran, D., Grimanelli, D., Slotkin, R.K., Martienssen, R.A., and Vielle-Calzada, J.-P. (2010). Control of female gamete formation by a small RNA pathway in Arabidopsis. Nature 464: 628–632, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08828.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Palovaara, J., de Zeeuw, T., and Weijers, D. (2016). Tissue and organ initiation in the plant embryo: a first time for everything. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 32: 47–75, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-124929.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Paysan-Lafosse, T., Blum, M., Chuguransky, S., Grego, T., Pinto, B.L., Salazar, G.A., Bileschi, M.L., Bork, P., Bridge, A., Colwell, L., et al.. (2023). InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 51: D418–D427, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac993.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Petrella, R., Cucinotta, M., Mendes, M.A., Underwood, C.J., and Colombo, L. (2021). The emerging role of small RNAs in ovule development, a kind of magic. Plant Reprod. 34: 335–351, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00497-021-00421-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Portereiko, M.F., Lloyd, A., Steffen, J.G., Punwani, J.A., Otsuga, D., and Drews, G.N. (2006). AGL80 is required for central cell and endosperm development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18: 1862–1872, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.106.040824.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Punwani, J.A., Rabiger, D.S., and Drews, G.N. (2007). MYB98 positively regulates a battery of synergid-expressed genes encoding filiform apparatus–localized proteins. Plant Cell 19: 2557–2568, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.107.052076.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pushpa, K., Kumar, G.A., and Subramaniam, K. (2017). Translational control of germ cell decisions. In: Arur, S. (Ed.), Results and problems in cell differentiation. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 175–200.10.1007/978-3-319-44820-6_6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rabiger, D.S. and Drews, G.N. (2013). MYB64 and MYB119 are required for cellularization and differentiation during female gametogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003783, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003783.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rappsilber, J., Mann, M., and Ishihama, Y. (2007). Protocol for micro-purification, enrichment, pre-fractionation and storage of peptides for proteomics using StageTips. Nat. Protoc. 2: 1896–1906, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.261.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Reichel, M., Liao, Y., Rettel, M., Ragan, C., Evers, M., Alleaume, A.-M., Horos, R., Hentze, M.W., Preiss, T., and Millar, A.A. (2016). In planta determination of the mRNA-binding proteome of Arabidopsis etiolated seedlings. Plant Cell 28: 2435–2452, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00562.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rodríguez-Leal, D., León-Martínez, G., Abad-Vivero, U., and Vielle-Calzada, J.-P. (2015). Natural variation in epigenetic pathways affects the specification of female gamete precursors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 27: 1034–1045, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.114.133009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sajeev, N., Baral, A., America, A.H.P., Willems, L.A.J., Merret, R., and Bentsink, L. (2022). The mRNA‐binding proteome of a critical phase transition during Arabidopsis seed germination. New Phytol. 233: 251–264, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17800.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sprunck, S., Urban, M., Strieder, N., Lindemeier, M., Bleckmann, A., Evers, M., Hackenberg, T., Möhle, C., Dresselhaus, T., and Engelmann, J.C. (2019). Elucidating small RNA pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana egg cells. bioRxiv: 525956.10.1101/525956Search in Google Scholar

Steffen, J.G., Kang, I.-H., Portereiko, M.F., Lloyd, A., and Drews, G.N. (2008). AGL61 interacts with AGL80 and is required for central cell development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 148: 259–268, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.119404.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sysoev, V.O., Fischer, B., Frese, C.K., Gupta, I., Krijgsveld, J., Hentze, M.W., Castello, A., and Ephrussi, A. (2016). Global changes of the RNA-bound proteome during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 7: 12128, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12128.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tamarozzi, E. and Giuliatti, S. (2018). Understanding the role of intrinsic disorder of viral proteins in the oncogenicity of different types of HPV. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19: 198, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19010198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tedeschi, F., Rizzo, P., Rutten, T., Altschmied, L., and Bäumlein, H. (2017). RWP‐RK domain‐containing transcription factors control cell differentiation during female gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 213: 1909–1924, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14293.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

The, M., Samaras, P., Kuster, B., and Wilhelm, M. (2022). Reanalysis of ProteomicsDB using an accurate, sensitive, and scalable false discovery rate estimation approach for protein groups. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 21: 100437, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcpro.2022.100437.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tian, T., Liu, Y., Yan, H., You, Q., Yi, X., Du, Z., Xu, W., and Su, Z. (2017). agriGO v2.0: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community, 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 45: W122–W129, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx382.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tristan, C., Shahani, N., Sedlak, T.W., and Sawa, A. (2011). The diverse functions of GAPDH: views from different subcellular compartments. Cell. Signal. 23: 317–323, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.08.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Uversky, V.N. (2013). A decade and a half of protein intrinsic disorder: biology still waits for physics. Protein Sci. 22: 693–724, https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.2261.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wang, P., Clark, N.M., Nolan, T.M., Song, G., Bartz, P.M., Liao, C.-Y., Montes-Serey, C., Katz, E., Polko, JK, Kieber, J.J., et al.. (2022). Integrated omics reveal novel functions and underlying mechanisms of the receptor kinase FERONIA in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 34: 2594–2614, https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koac111.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wang, X., Lu, Z., Gomez, A., Hon, G.C., Yue, Y., Han, D., Fu, Y., Parisien, M., Dai, Q., Jia, G., et al.. (2014). N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505: 117–120, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12730.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ware, A., Jones, D.H., Flis, P., Chrysanthou, E., Smith, K.E., Kümpers, B.M.C., Yant, L., Atkinson, J.A., Wells, D.M., Bhosale, R., et al. (2023). Loss of ancestral function in duckweed roots is accompanied by progressive anatomical reduction and a re-distribution of nutrient transporters. Curr. Biol. 33: 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.03.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

White, M.R. and Garcin, E.D. (2016). The sweet side of RNA regulation: glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase as a noncanonical RNA‐binding protein. WIREs RNA 7: 53–70, https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1315.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wu, X., Chory, J., and Weigel, D. (2007). Combinations of WOX activities regulate tissue proliferation during Arabidopsis embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 309: 306–316, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.019.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Yang, Y. (2002). Solution structure of the LicT-RNA antitermination complex: CAT clamping RAT. EMBO J. 21: 1987–1997, https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/21.8.1987.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Zavortink, M., Rutt, L.N., Dzitoyeva, S., Henriksen, J.C., Barrington, C., Bilodeau, D.Y., Wang, M., Chen, X.X.L., and Rissland, O.S. (2020). The E2 Marie Kondo and the CTLH E3 ligase clear deposited RNA binding proteins during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. eLife 9: 1–48, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.53889.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Z., Boonen, K., Ferrari, P., Schoofs, L., Janssens, E., van Noort, V., Rolland, F., and Geuten, K. (2016). UV crosslinked mRNA-binding proteins captured from leaf mesophyll protoplasts. Plant Methods 12: 42, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-016-0142-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Zhao, P., Zhou, X., Shen, K., Liu, Z., Cheng, T., Liu, D., Cheng, Y., Peng, X., and Sun, M. (2019). Two-step maternal-to-zygotic transition with two-phase parental genome contributions. Dev. Cell 49: 882–893.e5, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2019.04.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Zhou, X., Liu, Z., Shen, K., Zhao, P., and Sun, M.-X. (2020). Cell lineage-specific transcriptome analysis for interpreting cell fate specification of proembryos. Nat. Commun. 11: 1366, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15189-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2023-0195).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: CRC 960 - RNP Biogenesis

- Guest Editorial

- Highlight: how to synthesize, assemble and regulate ribonucleoprotein-complexes

- Initial Steps of RNP Biogenesis

- Features of yeast RNA polymerase I with special consideration of the lobe binding subunits

- Synthesis of the ribosomal RNA precursor in human cells: mechanisms, factors and regulation

- Cellular Functions of RNPs

- The human long non-coding RNA LINC00941 and its modes of action in health and disease

- The chromatin – triple helix connection

- Post-transcriptional gene silencing in a dynamic RNP world

- Cytosolic RGG RNA-binding proteins are temperature sensitive flowering time regulators in Arabidopsis

- The archaeal Lsm protein from Pyrococcus furiosus binds co-transcriptionally to poly(U)-rich target RNAs

- RNP Turnover

- A structural biology view on the enzymes involved in eukaryotic mRNA turnover

- RNP Analysis

- Detection of a 7SL RNA-derived small non-coding RNA using Molecular Beacons in vitro and in cells

- RBPome identification in egg-cell like callus of Arabidopsis

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: CRC 960 - RNP Biogenesis

- Guest Editorial

- Highlight: how to synthesize, assemble and regulate ribonucleoprotein-complexes

- Initial Steps of RNP Biogenesis

- Features of yeast RNA polymerase I with special consideration of the lobe binding subunits

- Synthesis of the ribosomal RNA precursor in human cells: mechanisms, factors and regulation

- Cellular Functions of RNPs

- The human long non-coding RNA LINC00941 and its modes of action in health and disease

- The chromatin – triple helix connection

- Post-transcriptional gene silencing in a dynamic RNP world

- Cytosolic RGG RNA-binding proteins are temperature sensitive flowering time regulators in Arabidopsis

- The archaeal Lsm protein from Pyrococcus furiosus binds co-transcriptionally to poly(U)-rich target RNAs

- RNP Turnover

- A structural biology view on the enzymes involved in eukaryotic mRNA turnover

- RNP Analysis

- Detection of a 7SL RNA-derived small non-coding RNA using Molecular Beacons in vitro and in cells

- RBPome identification in egg-cell like callus of Arabidopsis