Cytosolic RGG RNA-binding proteins are temperature sensitive flowering time regulators in Arabidopsis

-

Andrea Bleckmann

, Nicole Spitzlberger

, Hans F. Ehrnsberger

, Lele Wang

, Astrid Bruckmann

, Stefan Reich

, Klaus D. Grasser

and Thomas Dresselhaus

Abstract

mRNA translation is tightly regulated by various classes of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) during development and in response to changing environmental conditions. In this study, we characterize the arginine-glycine-glycine (RGG) motif containing RBP family of Arabidopsis thaliana representing homologues of the multifunctional translation regulators and ribosomal preservation factors Stm1 from yeast (ScStm1) and human SERBP1 (HsSERBP1). The Arabidopsis genome encodes three RGG proteins named AtRGGA, AtRGGB and AtRGGC. While AtRGGA is ubiquitously expressed, AtRGGB and AtRGGC are enriched in dividing cells. All AtRGGs localize almost exclusively to the cytoplasm and bind with high affinity to ssRNA, while being capable to interact with most nucleic acids, except dsRNA. A protein-interactome study shows that AtRGGs interact with ribosomal proteins and proteins involved in RNA processing and transport. In contrast to ScStm1, AtRGGs are enriched in ribosome-free fractions in polysome profiles, suggesting additional plant-specific functions. Mutant studies show that AtRGG proteins differentially regulate flowering time, with a distinct and complex temperature dependency for each AtRGG protein. In conclusion, we suggest that AtRGGs function in fine-tuning translation efficiency to control flowering time and potentially other developmental processes in response to environmental changes.

1 Introduction

Translational control is required to regulate gene expression and protein production. It is important during development and under stress conditions to allow rapid adaptation to changing environments. As plants are sessile, they are exposed to drastic daily and seasonal changes of temperature, light intensity and duration, as well as water availability. To survive, plants adjust gene expression and protein production at multiple levels, including translation. Translation of mRNAs into proteins belongs to the major energy consuming processes in every cell and therefore has to be tightly regulated depending on the developmental status and environmental condition of a cell (Edwards et al. 2012; Kosmacz et al. 2019; Merchante et al. 2017). Control of cytoplasmic mRNA translation represents a very effective mechanism to rapidly adapt to environmental changes. In general, translation can be divided into three phases: initiation, elongation and termination/recycling (Browning and Bailey-Serres 2015). The initiation phase uses at least ten eukaryotic initiation factors to locate the initiator tRNA (Met-tRNA) together with the start codon of the mRNA to the P site of the 40S ribosomal subunit forming the 48S preinitiation complex (PIC). The PIC then associates with the 60S ribosomal subunit forming the 80S initiation complex, which is ready for protein biosynthesis during the elongation process (Blanchet and Ranjan 2022). Translation regulation most frequently occurs during the initiation phase, which also shows the highest diversification among the kingdoms of life. Modification of ribosomal proteins, initiation factors, or elongation factors is widely employed to globally adjust translation rates to the cellular requirement. In parallel, trans-acting factors such as RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) or microRNAs allow mRNA-specific translational control (reviewed in (Hershey et al. 2012; Blanchet and Ranjan 2022)). To respond to environmental changes, different mechanisms have been described that reversibly suppress global mRNA translation in eukaryotes. This is essential, for example, during starvation or in response to stress such as heat, drought and high salt conditions, respectively (Chen et al. 2021). To control translation during cellular stress, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Suppressor of Target of Myb protein 1 (ScStm1) or its mammalian homolog SERPINE mRNA-binding protein1 (HsSERBP1) can associate with ribosomes by inserting an α-helix into the mRNA entry channel sterically occluding mRNA association and preventing ribosome dissociation (Balagopal and Parker 2011; Ben-Shem et al. 2011; Brown et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2021; Van Dyke et al. 2006; Van Dyke et al. 2013). Both proteins belong to the arginine-glycine-glycine (RGG) motif-containing proteins within the RBPs. Target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) was recently shown to phosphorylate ScStm1 and HsSERBP1 thereby reactivating translation (Shetty et al. 2023). During translation elongation ScStm1 stabilizes and enhances binding of the eukaryotic elongation factor eEF2 on 80S ribosomes in its GTP-bound state and together with eEF3 promotes elongation (Hayashi et al. 2018; Van Dyke et al. 2009). Furthermore, ScStm1 recruits the DEAD-box helicase ScDhh1 to translating ribosomes leading to mRNA degradation (Balagopal and Parker 2009). Although ScStm1 is primarily considered as a ribosome-associated protein, it also binds to G-quadruplexes, secondary structures that can be formed in G-rich sequences in both RNA and DNA, and it has been further shown to be associated with sub-telomeric DNA sequences in the nucleus (Lightfoot et al. 2019; Van Dyke et al. 2004; Yan et al. 2021). Similarly, the human homolog HsSERBP1, which is upregulated in a number of cancers (Colleti et al. 2019), is involved in various biological processes. For example, HsSERBP1 can stabilize dormant 80S ribosomes by replacing the mRNA (Smith et al. 2021), functions in the recruitment of transcriptional repressors to DNA (Poole and Sinclair 2022), or interacts with cellular target mRNAs and viral RNA to regulate their translation, stability and replication, respectively (Brugier et al. 2022; Colleti et al. 2019; Yuan et al. 2022). Notably, due to the lack of canonical RNA-binding motifs such as RRM domains in ScStm1 and HsSERBP1, it is still unclear how these well investigated RBPs recognize and bind their target RNAs and DNAs (Baudin et al. 2021).

Comparably little is known about the role of RGG box-containing proteins in plants and their involvement in the regulation of translation during development or in response to environmental changes. Here, we characterize the three RGG box-containing proteins AtRGGA, AtRGGB and AtRGGC of Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis), which represent ScStm1 and HsSERBP1 homologues. Of those AtRGG proteins, only AtRGGA was previously described as an RGG box-containing RBP that influences tolerance to salt and drought stress (Ambrosone et al. 2015). We experimentally tested if all AtRGGs are capable to bind various types of nucleic acids and further studied their functional conservation by complementation assays in yeast. We analyzed the expression pattern and subcellular localization of all three AtRGG proteins. Additionally, we investigated the interaction of AtRGGs with active ribosomes by polysome profiles in comparison to ScStm1 and analyzed a protein interactome, using AtRGGB as an example. Finally, we report phenotypes of single and multiple rgga, rggb and rggc knock-down/knock-out mutants under various environmental conditions, showing their role in temperature dependent flowering time regulation.

2 Results

2.1 The Arabidopsis genome encodes three RGG proteins capable of interacting with nucleic acids

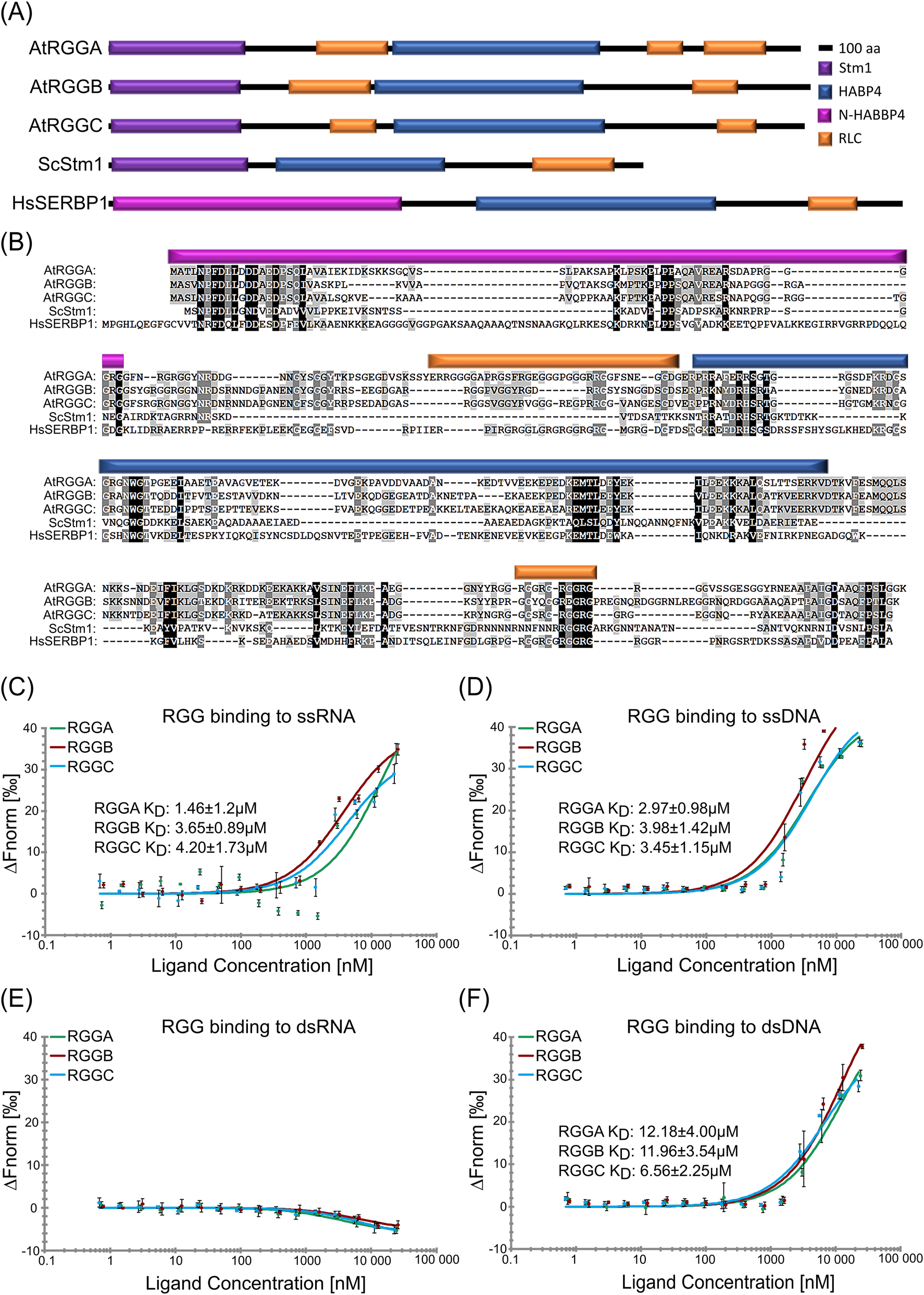

We screened the genome of A. thaliana for potential homologues of Suppressor of Target of Myb protein 1 from S. cerevisiae (ScStm1) and SERPINE1 mRNA-binding protein 1 from Homo sapiens (HsSERBP1) and identified a small protein family composed of three members named AtRGGA (At4G16830), AtRGGB (At4G17520) and AtRGGC (At5G47210). This protein family is specified by its N-terminal STM1-like domain and its internal hyaluronan/mRNA-binding domain (Figure 1A and B). In addition, AtRGGs contain an internal and a C-terminal arginine-glycine (RG)-/arginine-glycine-glycine (RGG)-motive forming regions of low complexity (RLC). A similar RLC is also present in the C-terminal region of ScStm1 containing additionally a stretch of asparagines. The human homologue HsSERBP1 contains a C-terminal RG-/RGG-motif, similar to the corresponding region in AtRGGs. An alignment of the five proteins shows their conservation over the entire sequence with ScStm1, ranging between 22 % and 25 % amino acid identity (AtRGGA 22.3 %, AtRGGB 22.7 % and AtRGGC 24.9 %) and with HsSERBP1 ranging between 23 % and 29 % (AtRGGA 28.6 %, AtRGGB 23.2 % and AtRGGC 25.0 %) (Figure 1B). AtRGGs show a higher sequence conservation among themselves with 53.2 % identity between AtRGGA and AtRGGB, 57.8 % identity between AtRGGA and AtRGGC and 64.1 % identity between AtRGGB and AtRGGC, respectively. Phylogenetic comparison of AtRGGs with homologs from other plants, animals and fungi shows their high evolutionary conservation, suggesting functional conservation (Figure S1). Notably, ScStm1 clustered most closely to sequences of other fungi and mammals, whereas plant homologs form a separated subclade. Based on the presence of a Hyaluronan/mRNA-binding domain in all three Arabidopsis proteins, we assumed that, similar to ScStm1, they interact with nucleic acids. Binding of AtRGGA to isolated total mRNA from Arabidopsis has been shown previously (Ambrosone et al. 2015). To clarify if all AtRGGs can bind nucleic acids, we purified recombinant His6-MBP-AtRGG fusion proteins from Escherichia coli and used them in a MicroScale Thermophoresis (MST) assay together with synthesized Cy3-labeled 25-nt ssRNA, dsRNA, ssDNA or dsDNA for in solution interaction studies. All AtRGGs were able to bind ssRNA, ssDNA as well as dsDNA with different affinities (Figure 1C–F). Binding to dsRNA could not be detected, while the other nucleic acids were bound with dissociation constants (K D ) ranging between 6.56 ± 2.25 µM – 12.18 ± 4.00 µM for dsDNA, 2.97 ± 0.98 µM – 3.98 ± 1.42 µM for ssDNA, and 1.46 ± 1.2 µM – 4.20 ± 1.73 µM for ssRNA (Figure 1C–F). The strongest general binding affinity to nucleic acids could be measured from AtRGGA to ssRNAs (KD 1.46 ± 1.2 µM). Whereas AtRGGB showed a lower binding affinity (KD 3.65 ± 0.89 µM) and AtRGGC displayed the lowest affinity to ssRNA (KD 4.20 ± 1.73 µM). All AtRGGs are also capable to bind to ssDNA with similar affinities (KD 2.97 µM–3.98 µM) and dsDNA with generally lower affinity (KD 6.56 µM–12.18 µM). To verify the binding to ssRNA and dsDNA we also performed an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). A clear shift of ssRNA and dsDNA can be seen with increasing amounts of added recombinant protein (Figure S2). In conclusion, all AtRGGs represent single stranded RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that are also capable to interact with DNA in vitro.

The Arabidopsis genome contains three genes encoding arginine-glycine-glycine (RGG) motif-containing RNA-binding proteins (AtRGGA, AtRGGB and AtRGGC) capable of binding preferentially single stranded nucleic acids. (A) Schematic illustration of protein domains identified in Arabidopsis RGG proteins and their yeast (ScStm1) and human (HsSERBP1) homologs, respectively. All proteins are composed of two RNA-binding domains, an N-terminal STM1 or N-HABP4, and an internal HABP4-PAI domain. Regions of lower complexity, but rich in arginine (R) and glycine (G) (RLC) are indicated. (B) Multiple sequence alignment of the proteins depicted in panel (A). Identical amino acids are shown with black shading, conserved amino acids are shaded in grays depending on the degree of conservation. Protein domains are colored according to (A). (C–F) In solution interaction study of RGGs binding to ssRNA (C), ssDNA (D), dsRNA (E), and dsDNA (F) in MST assays. KD-values are indicated.

2.2 AtRGG proteins partially associate with ribosomes

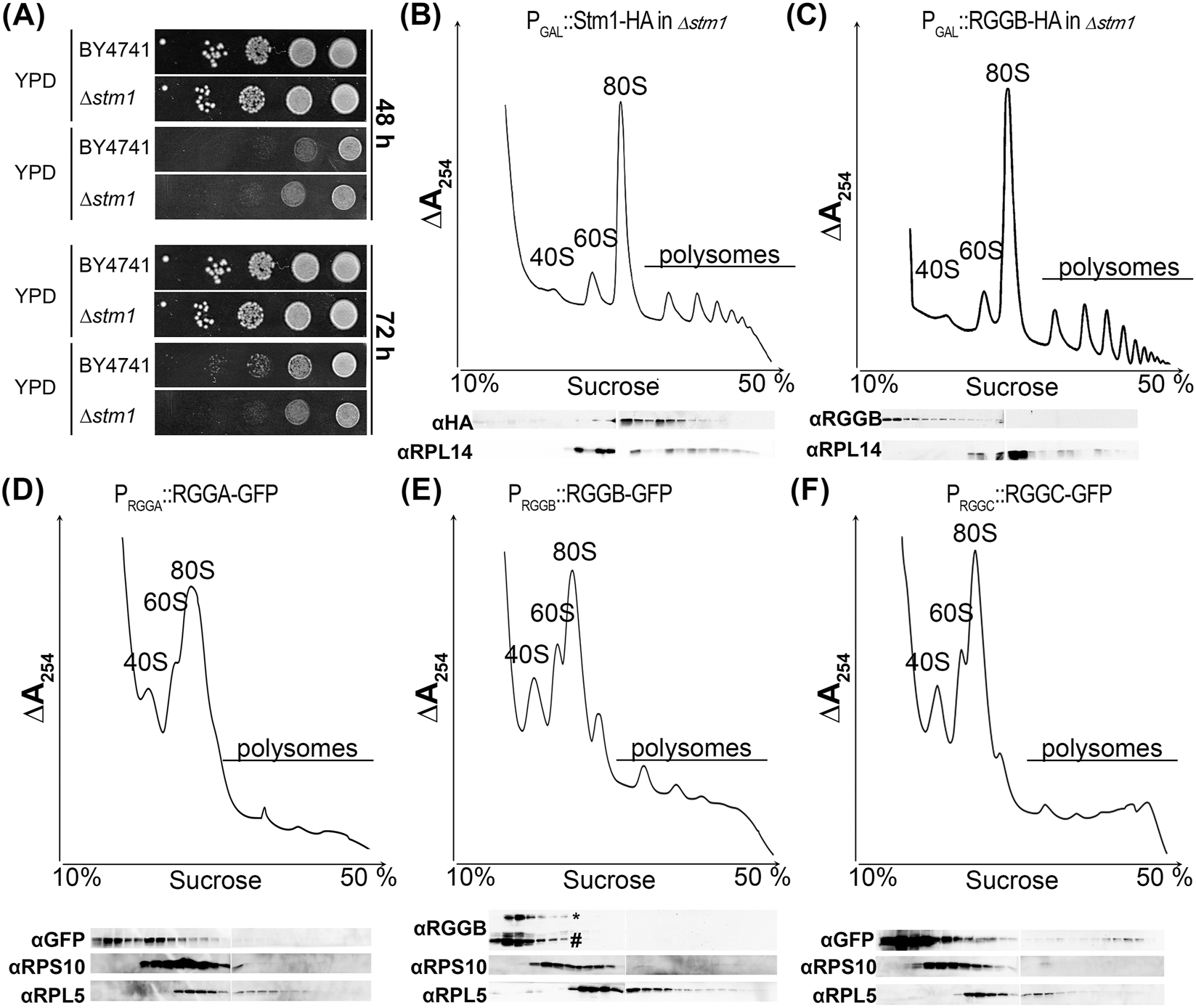

To test if AtRGGB (as an example of the RGG family) is a functional ortholog of ScStm1 in yeast we tried to rescue the yeast ∆stm1 phenotype. As the previously published ScStm1 mutant strain was not available anymore, we obtained a ScStm1 deletion strain (∆stm1) and the isogenic parental strain BY4741 as control from the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project (Winzeler et al. 1999). Previously, hyper-sensitivity of a stm1-mutant against the antibiotic rapamycin, an inhibitor of the TOR signaling pathway, was reported (Van Dyke et al. 2006). Using ∆stm1, we could detect only a modest, insignificant growth reduction in the presence of rapamycin. On plates, parental strain BY4741 and ∆stm1 grew colonies of a similar size and for both strains we observed a comparable growth reduction on media containing rapamycin after 48 h. Only after 72 h growth on rapamycin ∆stm1 colonies seemed slightly smaller compared to BY4741 (Figure 2A). As we were not able to reproduce the published phenotype with the new strains, we could not test the orthologous nature of RGGs to ScStm1 with this strategy, due to the lack of a physiological phenotype. However, we were able to biochemically compare the molecular function of RGGs and ScStm1 in yeast. ScStm1 was reported to associate with ribosomes to control translation initiation and elongation (Hayashi et al. 2018; Van Dyke et al. 2006; Van Dyke et al. 2009). To analyze functional similarities, we expressed AtRGGB and ScStm1 in the ∆stm1 strain using a galactosidase-inducible promoter and generated polysome profiles from logarithmically growing cell cultures (Figure 2B and C). Western blotting against the large ribosomal subunit protein RPL14 confirmed its presence in the 60S and 80S fractions. As previously reported, we detect ScStm1 in fractions containing 80S monosomes and polysomes (Figure 2B) (Balagopal and Parker 2009; Balagopal and Parker 2011; Van Dyke et al. 2009). ScStm1 could only be weakly detected in low-density fractions that are devoid of ribosomal subunits. This indicates that the majority of ScStm1 is bound to ribosomes and/or ribosome-associated mRNAs. In contrast, AtRGGB is mainly found in low-density, ribosome-free fractions and only a small amount of protein co-sediments with 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits (Figure 2C).

AtRGGs and their yeast homolog ScStm1 exhibit different ribosome association properties. (A) Growth of wild type yeast strain BY4741 and its isogenic counterpart lacking ScStm1 (∆stm1∆) were plated on YPD with and without rapamycin, respectively. Colony growth after 48 h and 72 h of incubation is shown. (B–C) Fractionation of cytoplasmic lysates of Δstm1 yeast cells transformed with ScStm1 and AtRGGB constructs, respectively, using sucrose gradient centrifugation. Migration of ribosomal 40S and 60S subunits as well as 80S ribosomes and polysomes is indicated. Top panels show RNA distribution by UV absorption (at 254 nm) and bottom panels show Western blots using antibodies against ribosomal proteins RPL14 as indicator for the large 60S ribosomal subunit. HA-tag-specific antibodies indicate the distribution of ScStm1-HA (B) and AtRGGB-HA (C), respectively. (D–F) Polysome profiles of Arabidopsis seedlings expressing AtRGGA-GFP (D), AtRGGB-GFP (E), and AtRGGC-GFP (F). Distribution of ribosomal subunits was confirmed by Western blot using antibodies against a ribosomal protein of the large subunit (RPL5) and the small subunit (RPS18), respectively. Asterisk in (E) indicates Western blot bands of RGGB-GFP and hash indicates bands of endogenous AtRGGB detected by an AtRGGB-specific antibody. AtRGGA and AtRGGC separation was analyzed using a GFP-specific antibody.

To test whether RGGs exhibit increased association with plant ribosomes, we analyzed the sedimentation behavior of all AtRGGs in polysome profiles using reporter lines expressing GFP fusion proteins under control of their endogenous promoters in Arabidopsis. The expressed GFP fusion proteins are functional and can rescue the mutant phenotypes, which we will be described in detail below. Protein extracts from 10 days old seedlings were separated on sucrose gradients and the distribution of ribosomal subunits was monitored by UV absorbance and Western blot experiments detecting the ribosomal proteins RPS10 and RPL5 as markers of the 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits. Similar to the results in yeast (Figure 2C), all three AtRGG-GFP fusion proteins were enriched in low-density fractions (Figure 2D–F) indicating that the majority of RGG protein does not associate with 80S ribosomes or ribosome-bound mRNA that sediment deeper in the gradient. All AtRGG-GFP fusions could be detected, to a different extent, in fractions containing 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits and at a very low level in fractions containing polysomes (Figure 2D–F and Figure S3). This suggests that in contrast to ScStm1 in yeast (Figure 2B) only a very small fraction of RGGs might be associated with actively translating ribosomes in plants. To demonstrate that the GFP tag did not alter ribosome association of RGGs, we used an AtRGGB-specific antibody to detect the endogenous, non-tagged protein. It exhibited a sedimentation profile similar to the GFP-tagged protein (Figures 2E and S3). This suggests that AtRGG proteins might be functionally different from their yeast homologue ScStm1 and serve other or additional functions.

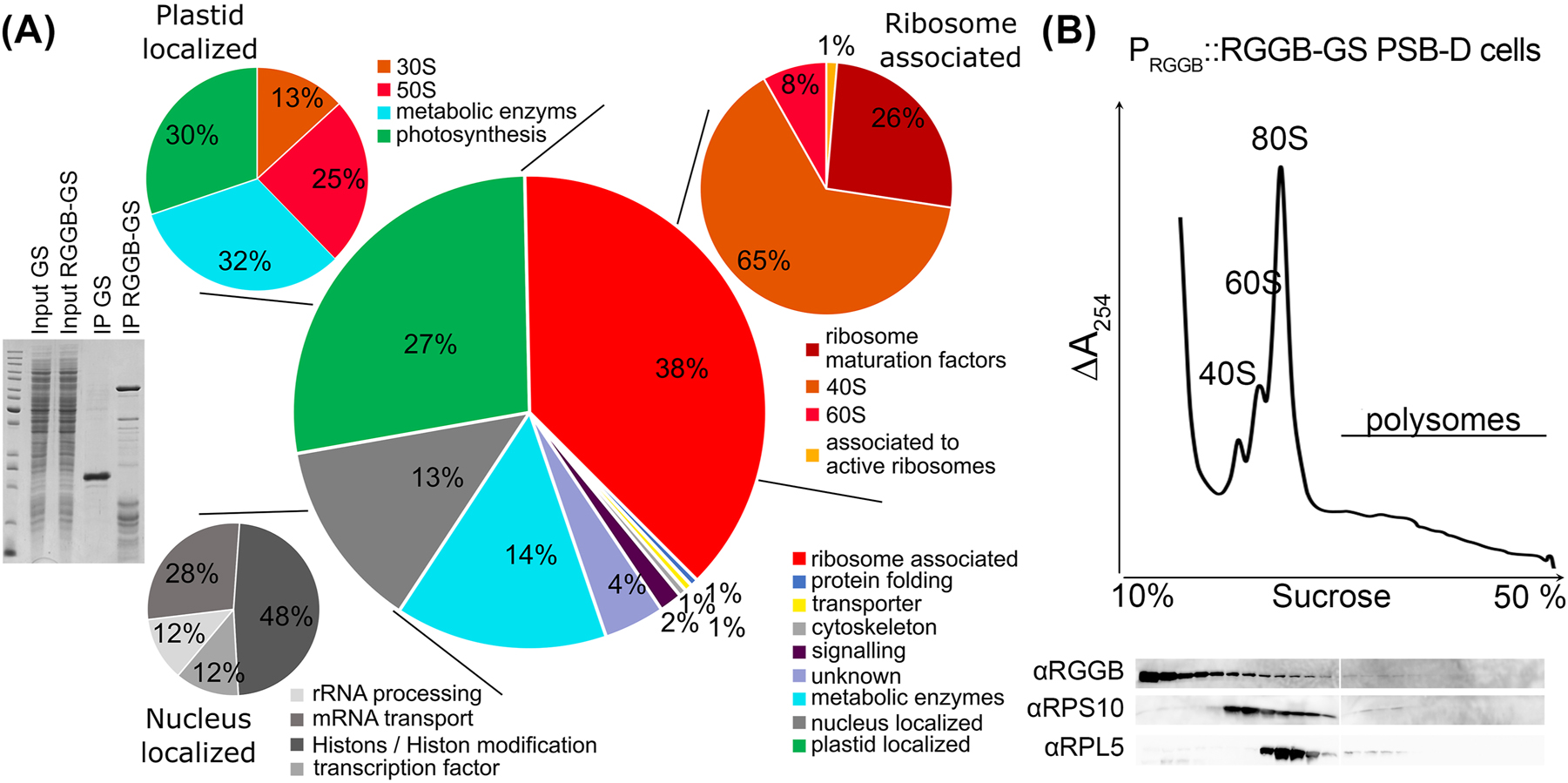

2.3 AtRGGB interacts with proteins of ribosomal subunits and active ribosomes

To identify the AtRGG interactome we expressed AtRGGB-GS (AtRGGB fused to two Protein G modules and a streptavidin binding peptide) in Arabidopsis PSB-D cell suspension culture under control of its endogenous promoter. A line expressing the GS-tag only served as a control. GS-tagged proteins were isolated from extracts treated with Sm nuclease (Benzonase) by IgG affinity purification. Multiple AtRGGB-GS interacting proteins could be purified and identified by mass spectrometry, which were not enriched or present in the control experiments employing the GS-tag only (Figure 3A). The experiment was repeated in triplicate and proteins were excluded that (1) were identified in only one of the replicate experiments with a mascot score of less than 80, (2) were identified in two or more of the control experiments, (3) exhibited a higher mascot score in the control experiments versus the AtRGGB pulldown, or (4) are listed as common contaminants according to an extended protein database of nonspecific proteins identified in 543 tandem affinity purification coupled to mass spectrometry experiments (Van Leene et al. 2015). By this, we obtained a final list of 193 potentially AtRGGB interacting proteins (Table S3). From the putative interactors, 38 % are associated with active ribosomes and most of these proteins are structural components of the 40S (26 %) and 60S (65 %) subunits, respectively (Figure 3A). 13 % of identified proteins were predicted to possess a nuclear function, like histones and histone modifying enzymes (48 % of this subgroup), or a function involved in mRNA transport (28 %), rRNA processing (12 %) and as transcription factors (12 %), respectively – functions that AtRGGB has not previously been associated with. Furthermore, 27 % (n = 53) plastidal interactors were identified. However, 38 % of these proteins are structural components of the plastid ribosomes and might originate from promiscuous interaction after cell lysis which do not reflect the in vivo situation since AtRGGs have not been detected in plastids. Considering that ribosomal proteins of both subunits represented the dominating protein fraction, we investigated if AtRGGB-GS shows a stronger ribosome association in PSB-D cells compared to seedlings. Therefore, we generated a polysome profile from PSB-D suspension cell extracts. Similar to seedlings, the main proportion of AtRGGB-GS could be detected in the soluble non-ribosome containing fraction, but we also observed AtRGGB in the 40S, 60S and 80S fractions at slightly higher amounts compared with the profile from seedlings (Figure 2E versus Figure 3B). Only a faint signal can be seen in polysomal factions. These findings support the hypothesis that plant RGGs can interact with active ribosomes to likely influence their activity and that this interaction likely depends on the cell type, developmental stage and/or environmental condition. To test whether AtRGGs can globally affect translation, we added purified recombinantly expressed His6-MBP-AtRGG fusion protein to a wheat germ extract-based in vitro translation assay using Luciferase mRNA as template for protein syntheses. Translation was quantified by the determination of luciferase activity after two hours of incubation at 23 °C (Figure S4). None of the AtRGG proteins showed an effect on translation output. However, this does not exclude the possibility that AtRGGs can control the translation of specific RNAs or they impinge on translation under specific conditions, e.g. in a developmentally regulated manner or in response to specific environmental changes.

Protein interactome of AtRGGB in Arabidopsis suspension cells. (A) IgG affinity purification of Arabidopsis PSB-D suspension cells expressing PAtRGGB::AtRGGB-GS and 35S::GS, respectively. Left: Separation of cell extract and IP eluates of GS and AtRGGB-GS expressing cells in a Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE as indicated. By mass spectrometry, 193 enriched proteins were identified in the AtRGGB-GS fraction. Right: GO-term analysis of RGGB-GS interacting proteins. See Table S3 for details. RGGB especially interacts with ribosomal proteins as well as proteins involved in RNA processing and transport, histones and proteins involved in histone modification as well as metabolic enzymes. 38 % of all proteins can be associated to the ribosome (red) either as structural components, as ribosomal maturation factors or translation regulators. 13 % of all proteins (grey) are known to be localized to the nucleus (stable or transiently), which can act in rRNA processing, mRNA transport, as transcription factors or histones. 27 % of all proteins localize to plastids (green). Here most of the isolated plastid-localized proteins represent ribosomal proteins. (B) Polysome profile of AtRGGB-GS expressing PSB-D cells performed as described in Figure 2. Endogenous AtRGGB is present in ribosome fractions, but highest protein amounts accumulate in light, ribosome-free fractions.

2.4 AtRGG proteins are ubiquitously expressed cytosolic proteins

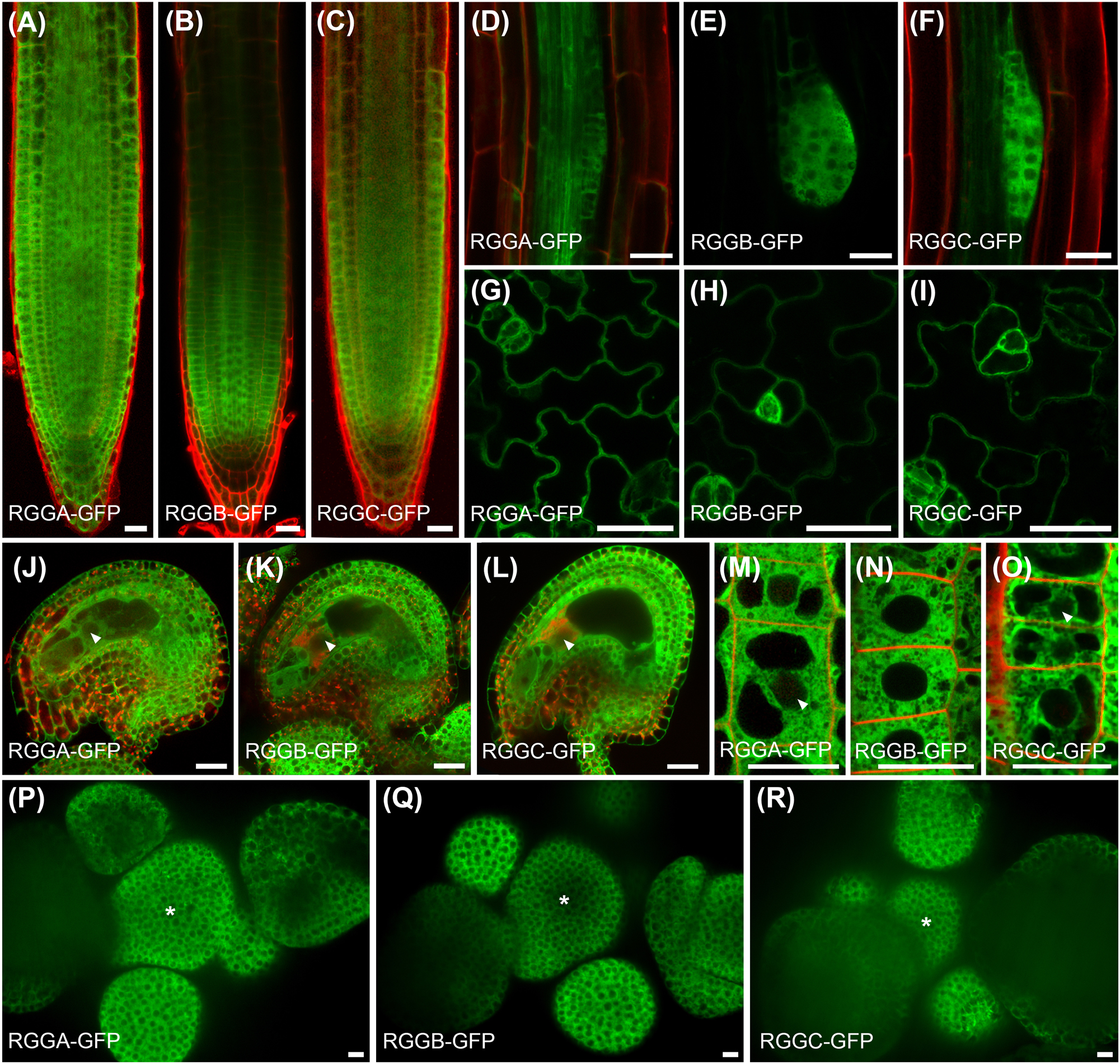

Based on publicly available transcriptome data, AtRGG genes are ubiquitously expressed in most tissues with the exception of e.g. anthers and pollen which lack AtRGG transcripts (Figure S5). To study AtRGG expression and localization in more detail and with subcellular resolution, we used the AtRGG-GFP fusion protein reporter lines mentioned earlier. P RGGA ::RGGA-GFP expressing Arabidopsis lines showed homogeneous GFP fluorescence in all sporophytic and gametophytic tissues analyzed including root tips, lateral roots, leaves, during embryogenesis as well as in mature ovules (Figure 4A, D, G, J). P RGGB ::RGGB-GFP and P RGGC ::RGGC-GFP were expressed in all tissues similar to AtRGGA, but generally displayed an increased fluorescence intensity in young, dividing cells like the meristematic zone of the root tip, emerging lateral roots, in meristemoids of young leaves and in the shoot apical meristem (SAM, Figure 4B, C, E, F, H, I, K, L, P, R). At the subcellular level, all AtRGGs localized to the cytosol and were absent from cellular organelles (Figure 4M and O). Rarely, weak GFP-fluorescence could be observed in nuclei (Figure 4J–L, M and O arrowhead).

Expression pattern and subcellular localization of AtRGG-GFP-fusion proteins using endogenous promoters as indicated. (A–C) Expression pattern in the root tip, (D–F) during lateral root initiation, (G–I) in the leaf epidermis and (J–L) in mature ovules. AtRGGs appear ubiquitously expressed, but strongest signals are obtained in dividing cells. (M–O) Subcellular localization of AtRGG-GFP fusion proteins in epidermal root tip cells. Fusion proteins occur almost exclusively in the cytoplasm. Faint signals are visible in nuclei (examples marked by arrowheads). (P–R) Expression pattern in the shoot apical meristem (SAM). The center of the SAM is marked by an asterisk. Tissues in (A-D, F and J-O) were counterstained with propidium iodide (red). Scale bars are 10 µm.

2.5 Identification and generation of knock-out/knock-down alleles of AtRGGs

To elucidate biological functions of AtRGGs, we identified homozygous mutants for each gene (Figure 5A). For AtRGGA we used the T-DNA insertion line rgga-t1 (SALK_143514), which was previously described with an insertion in the second exon (Ambrosone et al. 2015). In contrast, we located the T-DNA insertion in the first exon. By using insertion spanning primers, we could still detect low amounts of transcript, which were strongly reduced compared to wt (Figure S6A–C). For AtRGGB, a T-DNA insertion line was available containing an insertion in the fifth intron (rggb-t2) (Figure S6A and C). The insertion leads to a shortened transcript truncating the RGG-motif containing C-terminus of the protein. Abundance of 5′ region transcripts was not affected, whereas T-DNA spanning transcripts and the 3′ region were not detectable (Figure S6B). As this mutant might not result in a complete loss-of-function mutant, we additionally created a deletion mutant using CRISPR/Cas9 using two guide RNAs. The mutant line rggb-c∆, containing a 1466 bp deletion affecting all conserved protein domains, was identified and likely represents a complete loss-of-function mutant (Figure S6A and C). For AtRGGC, two independent Salk T-DNA insertion lines with insertions in the second exon (rggc-t1) and fourth exon (rggc-t2) were identified (Figure S6A and C). rggc-t1 showed a strong reduction of transcript levels and only a weak signal could be detected by amplifying the 5′ region. However, using T-DNA flanking primers we could not detect any signal indicating that a stable transcript is not produced (Figure S6B). rggc-t2 represents a weak allele as reduced transcript levels were still detectable in a T-DNA insert spanning PCR. By crossing, we generated several double (rgga-t1/rggb-c∆, rgga-t1/rggc-t2, rggb-c∆/rggc-t2) and triple mutants (rgga-t1/rggb-c∆/rggc-t2).

AtRGGs control flowering time in Arabidopsis. (A) Images from indicated plant lines 32 days after germination (dag). This time point displays the mean bolting time of wild type (Col-0) plants. (B) Quantification of bolting time, (C) rosette leave numbers formed at bolting time and (D) rosette leaf area at bolting time. (E) Quantification of leaf area 35 dag. Number of samples per genotype are ≧17 collected in two independent experiments. Graphs in (B–E) show data as jittered dots. Summary of data is shown as box plots with boxes indicating the interquartile range (IQR), whiskers showing the range of values that are within 1.5*IQR and a horizontal line indicating the median. The median line of Col-0 is drawn as dashed line through the diagrams. Notches represent for each median the 95 % confidence interval (approximated by 1.58*IQR/sqrt(n)). The Col-0 confidence interval is highlighted by a grey box throughout the diagrams. Significantly distinct groups were determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (letters indicate statistically identical groups; p < 0.01). Box plots are colored for easy orientation: white for wild type, yellow for single mutants, orange for double mutants and red for triple mutants. The rescue lines are shown in green. Scale bar is 2 cm.

2.6 rgg mutants show flowering time phenotypes

To elucidate potential roles of AtRGGs during development we analyzed the isolated rgg mutants growing at standard growth conditions (Figure 5A). Neither the overall growth analyzed by root growth rate (Figure S7), nor the size of the adult plant is affected by AtRGG loss (Figure 5E; Anova Bonferroni Group a). However, all single mutants showed an early flowering phenotype compared to wt, which is also reflected by a reduced rosette leaf number and a reduced rosette leaf area at bolting time (Figure 5B and C; Anova Bonferroni Group b). Loss of AtRGGA or AtRGGB leads to a slightly, but significantly earlier flowering time compared to wt. Importantly, both rggb mutant lines exhibit the same phenotype suggesting that the loss of the C-terminal RGG motifs in rggb-t1 impairs AtRGGB function. Loss of AtRGGC had the strongest effect on flowering time and rosette leaf number, which are significantly reduced compared to wt and also to rgga-t1 or rggb-c∆ single mutants (Figure 5B–D, Anova Bonferroni Group d). Loss of AtRGGA and AtRGGB in rgga-t1/rggb-c∆ double mutant leads to a slightly enhanced phenotype compared to single mutants (Figure 5B, Anova Bonferroni Group d), but is still weaker than rggc single mutants (not present in Anova Bonferroni Group c). The strength of the rggc flowering phenotype could not be increased by loss of AtRGGA or AtRGGB, or both (rgga-t1/rggc-t2, rggb-c∆/rggc-t2 or rgga-t1/rggb-c∆/rggc-t2 all part of Anova Bonferroni Group d in Figure 5B and C). To confirm that the observed phenotypes are caused by the respective mutants, we performed rescue experiments by expressing AtRGG-GFP fusion proteins under control of the native promoter in the corresponding mutant backgrounds. The complementation lines could rescue the observed phenotype. Some lines even promote later flowering presumably due to higher expression levels than wt supporting the finding that AtRGGs play a role in flowering time control. All single mutants show an early flowering phenotype with smaller rosette leaf area at bolting whereas all gene reporter lines show the tendency of late flowering with bigger leaf area. These phenotypes indicate a function of AtRGG in the transition of shoot apical meristem to an inflorescence meristem. Other obvious growth defects could not be observed under our controlled growth conditions. We therefore suspect that observed changes in flowering time of rgg mutants could be attributed, for example, to a role in regulating translation of mRNAs associated with flowering time.

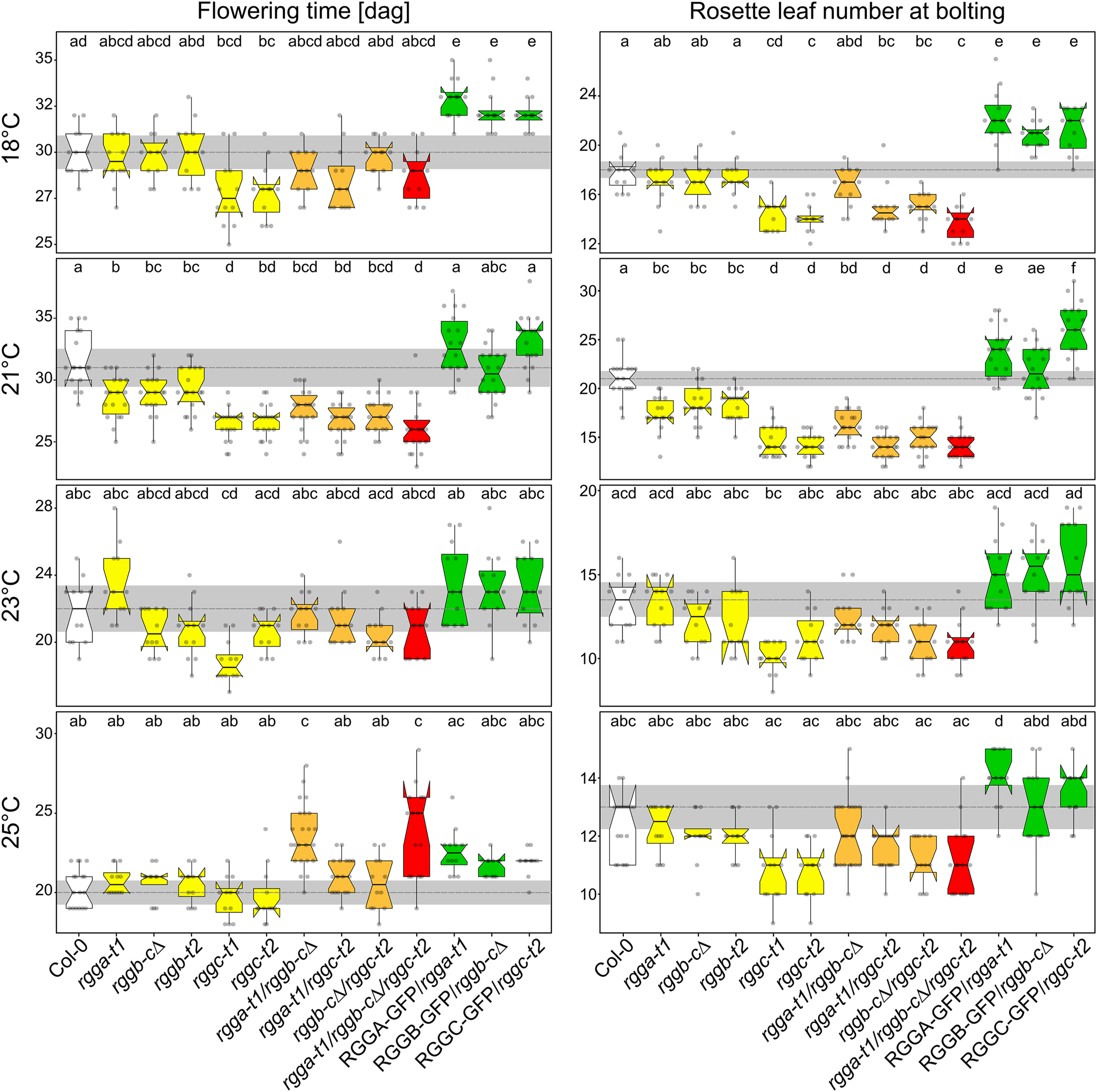

2.7 RGG effect on flowering time is temperature dependent

AtRGGA was already described as an RBP involved in salt and drought stress responses (Ambrosone et al. 2015). In that study, authors also mention a late flowering phenotype of the analyzed rgga-t1 mutant, which is in contrast to our findings. We wondered how this discrepancy could be explained and suspected a strong influence of environmental conditions, like temperature, on growth behavior and flowering transition in these mutants. Therefore, we grew all rgg mutants at different temperatures between 18 °C and 25 °C and analyzed flowering time. The effect of AtRGGC loss on flowering time was not altered by temperature. rggc grown at 18 °C and at 23 °C display an early flowering phenotype, which is still observable at 25 °C, but less pronounced compared to lower temperatures (Figure 6). The weak early flowering phenotype of rgga-t1 and rggb single mutants as well as the double mutants was not visible at 18 °C (Figure 6). On the other hand, a growth temperature of 23 °C leads to a conversion of the early flowering phenotype of rgga-t1 visible at 21 °C to a weak late flowering phenotype, even though the difference is not significant. At elevated temperature, both rggb single mutant lines still showed a tendency of early flowering even though the early meristem transition is only indicated by the rosette leaf number at 25 °C. For rgga-t1/rggb-c∆ double mutant, the opposite phenotype of rgga-t1 single mutant at 23 °C is compensated at the level of flowering time but not at the level of rosette leaf number. Here, the tendency of early flowering (Anova Bonferroni Group b) dominates. At 25 °C the flowering phenotype is hardly visible but can still be measured at the level of produced rosette leaves even though the difference isn’t significant due to high variance. Notably, the rgga/rggb double mutants as well as the triple mutant show a very high variance in flowering time. Moreover, expression of AtRGG-GFP fusion proteins induced a late flowering phenotype at 18 °C (Anova Bonferroni Group e). At 21 °C, 23 °C and 25 °C AtRGG-GFP expression complements the flowering phenotype of the single mutants at the level of flowering time (Anova Bonferroni Group a). At the level of rosette leaf number, the expression of AtRGGA-GFP and AtRGGC-GFP induces a late flowering phenotype at 21 °C (Anova Bonferroni Group e and f). At 25 °C only AtRGGA-GFP shows a significantly increased rosette leaf number (Anova Bonferroni Group d), whereas AtRGGB and AtRGGC behave like wt (Anova Bonferroni Group a). In summary, these observations show that AtRGG proteins are involved in flowering time regulation and integration of temperature into this developmental process. We show that in contrast to AtRGGC, only AtRGGA and AtRGGB regulate flowering time in a temperature dependent manner, highlighting that AtRGG functions are complex and only partially redundant.

AtRGGs influence flowering time in a temperature-dependent manner. Quantification of bolting time and rosette leave numbers initiated at bolting time at indicated growth temperature. Number of samples per genotype are ≧12 collected in two independent experiments. Graphs show data as jittered dots. Summary of the data is shown as boxplots with boxes indicating the interquartile range (IQR), whiskers showing the range of values that are within 1.5*IQR and a horizontal line indicating the median. The median line of Col-0 is drawn as dashed line through the diagrams. Notches represent for each median the 95 % confidence interval (approximated by 1.58*IQR/sqrt(n)). The Col-0 confidence interval is highlighted by a grey box throughout the diagrams. Significantly distinct groups were determined by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (letters indicate statistically identical groups; p < 0.01). Box plots are colored for easy orientation: white for wild type, yellow for single mutants, orange for double mutants and red for triple mutants. The rescue lines are shown in green.

3 Discussion

Translational control plays an important function in adjusting gene expression to the cellular requirements. E.g. the exposure of plants to light or darkness as well as cold treatments leads to massive increase or inhibition of translation which precedes changes at the transcriptional level (Cheong et al. 2021; Floris et al. 2013; Juntawong and Bailey-Serres 2012; Liu et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2013; Martinez-Seidel et al. 2021). Furthermore, correlation studies of mRNA and protein abundance during the day have shown that only 10 % of transcripts showing reduced translation also display a decrease in their mRNA levels (Pal et al. 2013; Piques et al. 2009). Changes in transcriptome and proteome are strongly correlated under standard conditions in most processes, but this correlation is lost upon injury, pathogen infection or after exposure to heat. This indicates that transcription and translation are differently coordinated under stress conditions (Chen et al. 2021). Cytoplasmic RNA binding proteins (RBPs) have been shown to play a key role during translation repression, activation and mRNA decay (Despic and Neugebauer 2018; Duarte-Conde et al. 2022). We describe here three homologues of the translational modulator Suppressor of Target of Myb protein 1 from S. cerevisiae (ScStm1) named AtRGGA, AtRGGB and AtRGGC containing a number of internal and C-terminally located RGG-motives. All three AtRGGs are RBPs and can bind to ssRNA and ssDNA as well as to dsDNA albeit with lower affinity. At the subcellular level AtRGGs locate to the cytoplasm where they mainly interact with ribosome-free mRNA but can also be found co-sedimenting with 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits, as well as with 80S monosomes and polysomes. Furthermore, the AtRGG interactome consists to a large extent of ribosomal proteins. As the pull-down experiments were performed with nuclease-treated samples, co-precipitated proteins are very likely enriched through protein-protein interactions rather than by RNA-based co-purification. The identified structural ribosomal proteins can be mapped back to both, 40S and 60S subunits with a weak preference for proteins of the small subunit. This indicates co-purification of whole translationally active ribosomes rather than direct interaction with the various ribosomal proteins. ScStm1 and its human homolog HsSERBP1 are present in crystal structures obtained from inactive 80S ribosomes as inhibitors of mRNA binding leading to ribosomal preservation (Ben-Shem et al. 2011; Giaever and Nislow 2014; Smith et al. 2021). The structure of the plant 80S ribosome from tomato has been resolved by cryo-EM recently and showed a generally conservation to its eukaryotic counterparts, but a ScStm1/AtRGG homologue was not detected (Cottilli et al. 2022). In Arabidopsis, the majority of AtRGGs proteins is detected in ribosome-free, 40S and 60S containing fractions and only a low protein amount is detected in 80S containing fractions. The association of AtRGGs with 80S ribosomes and polysomes is in agreement with the function of ScStm1, which stabilizes eEF2 on the 80S ribosome during translation elongation and interfere with the elongation factor eEF3 thereby affecting optimal translation elongation (Hayashi et al. 2018; Van Dyke et al. 2009). Notably, in polysome profiles, ScStm1 as well as HsSERBP1 were mostly absent from ribosome-free fractions and co-sedimented with ribosomal proteins (Muto et al. 2018; Van Dyke et al. 2006). This is in contrast to AtRGGs, which are enriched in ribosome-free fractions and fractions containing 40S and 60S subunits. The enrichment of ribosomal proteins of the small subunit could hint to a function of AtRGG during translation initiation which shows the highest diversification in kingdoms of life, whereas elongation and termination phase are more preserved (Browning and Bailey-Serres 2015). This indicates the evolution of possible additional and extra-ribosomal functions of AtRGGs in plants which is further supported by the clear separation of plant homologues from those of yeast and mammals, which cluster together in a phylogram.

AtRGGA seems to be associated with mRNAs essential for osmotic stress regulation (Ambrosone et al. 2015). However, the most obvious phenotype exhibited by rgg mutants was an early flowering phenotype, which could be altered to varying degrees of growth temperatures. These findings indicates that all AtRGGs likely interact with different subsets of mRNAs involved in floral transition, stress responses and likely other biological processes. Especially from studies on floral induction by the photoperiodic pathway that is mainly based on the circadian oscillator network, we have learned that oscillation of transcript abundance occurs during the day (reviewed in (Mateos et al. 2018; Webb et al. 2019)). This involves not only changes in gene expression levels, but also mRNA stability and decay, and translation control efficiencies. Connecting these results to the function of AtRGG proteins this study helps to understand how plants control the generation of flowering time regulators and fine-tune them in response to environmental conditions. For this, an important next step will be the identification of bound mRNAs and their translation status in a time (before and after flowering induction), or treatment-dependent manner. It will be important to elucidate whether binding affinities of AtRGGs to target mRNAs change, or if they influence translation initiation in a temperature-dependent manner.

The yeast homolog ScStm1 was originally identified as a G-quadruplex (G4) DNA binding protein (Frantz and Gilbert 1995). Such G4-structures have multiple genetic functions and impact gene expression, DNA replication and telomere maintenance in the nucleus and translation in the cytoplasm and via genetic instabilities in replication and transcription ultimately may lead to diseases and cancer (reviewed in (Griffin and Bass 2018; Rhodes and Lipps 2015; Teng et al. 2023)). A potential function of AtRGGs as nuclear proteins cannot be excluded taking into account that nuclear proteins such as histones and transcription factors were identified as putative interactors of AtRGGB. However, the very weak GFP signals observed in nuclei of diverse sporophytic and gametophytic plant tissues and the weaker interaction with dsDNA does not support the assumption that AtRGGs possess major nuclear functions at standard conditions like those reported for their yeast homolog. But it cannot be excluded that AtRGGs shuttle to the nucleus at certain environmental conditions and possess also nuclear function(s). To study the dynamics of a possible cytoplasm-nucleus shuttle at different environmental conditions and to elucidate associated function(s) is a very exciting, but also challenging task for future experimentation.

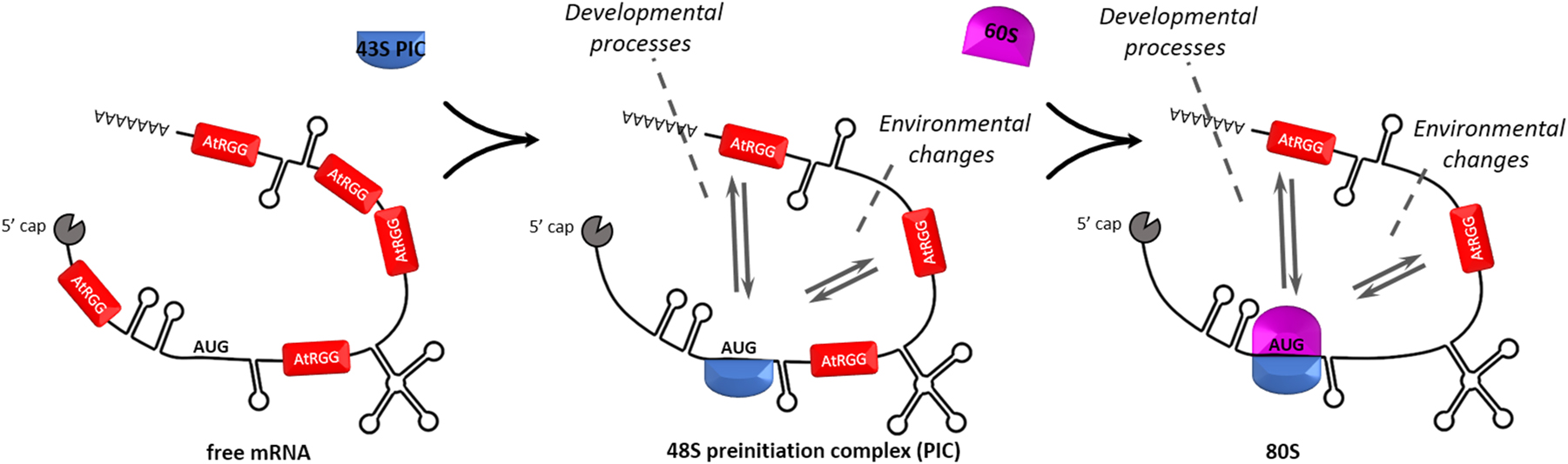

From the results presented here, we hypothesize that AtRGGs bind specific and only partly overlapping classes of mRNAs and regulate their translation through direct interaction with ribosomes, especially with the 40S subunit (Figure 7). However, how the communication of AtRGGs with ribosomes and the integration of environmental changes takes place is still unclear. In conclusion, the present study showed that AtRGG proteins regulate flowering time in a temperature dependent manner. The results contribute to our understanding of the multifunctional RGG proteins in general and will help to elucidate how plants respond to environment changes at the level of translation regulation.

Functional AtRGG model. Cytosolic AtRGG proteins are bound to single stranded mRNA regions and control their translation by direct interaction especially with the small subunit of the ribosome as well as with 80S monosomes in an environmental and developmental dependent manner. How environmental triggers, such as temperature, or osmotic stresses mechanistically affect AtRGG function and whether the three AtRGGs bind to different subsets of mRNAs remained unclear.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Plant material and growth

Arabidopsis (A. thaliana; Col-0) and mutant plants were grown on soil or on sterile GM Plates under long day conditions (16 h light at 21 °C and 8 h in the dark at 18 °C). Wild-type (wt) plants were transformed via the floral dip method (Clough and Bent 1998). Transgenics were identified by hygromycin resistance transmitted T-DNA insertion and verified by PCR. Mutant lines rgga-t1 (SALK_143514), rggb-t2 (SALK_129052), rggc-t1 (SALK_129026) and rggc-t2 (SALK_010856) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre. Homozygous mutant plants were identified by PCR using primer pairs listed in Table S1. An AtRGGB knockout line (rggb-c∆) containing a 1466 bp deletion (∆138–1604) was generated by CRISPR/Cas9 using the guide RNAs gRNA1 (5’ -GGAGGGAGAAACCAGAGGGA-3′) and gRNA2 (5′-GTACCAGCTTGAGAAGGAGGAS-3′) as described (Wang et al. 2015).

4.2 Reverse-transcribed PCR

Total RNA was extracted from leaf material using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) followed by DNaseI digestion. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Scientific). To study the presence of transcripts in mutant lines, semi-quantitative PCR was performed for 35 cycles using primer pairs listed in Table S1. Actin served as a reference. For each mutant line, the 5′-region of the transcript, the T-DNA spanning region and the 3′-region were analyzed by individual PCRs using primer pairs listed in Table S1.

4.3 Generation of transformation vectors

Genomic DNA of Arabidopsis 1527 bp (AtRGGA), 1284 bp (AtRGGB) and 839 bp (AtRGGC) upstream of the start codon were used as promoter regions and amplified together with the coding regions. See Table S1 for oligonucleotide sequences. DNA fragments were cloned into pENTR-D-TOPO (Thermo Scientific). In following LR-reactions, using pAB132 (Stahl et al. 2013) as destination vector, expression cassettes, containing AtRGGA-, AtRGGB- and AtRGGC-GFP fusions under control of the endogenous promoters, were generated.

To express AtRGGB in Arabidopsis PSB-D suspension cells, the gene locus was amplified as described above and cloned into pGreen0179-3′GS using KpnI and HindIII restriction sites (Antosz et al. 2017). As negative control for pulldown experiments pCambia2300-3′GS was used as described (Antosz et al. 2017). To express AtRGGB in yeast cells, the coding sequence was amplified from Arabidopsis leaf cDNA and cloned into pBG1805 by Gateway-technology (Gelperin et al. 2005) allowing AtRGGB-HA-His6 expression under control of a galactose-inducible promoter. The vector PGal::Stm1-HA-His6 (YSC3869) was purchased from DharmaconTM HorizonTM.

To generate recombinant proteins in E. coli, coding sequences of AtRGGA, AtRGGB and AtRGGC were amplified from Arabidopsis cDNA and cloned into the pENTR-D-TOPO vector. In following LR-reactions, using pDEST-His6-MBP (Nallamsetty et al. 2005), His6-MBP-RGGA, His6-MBP-RGGB and His6-MBP-RGGC were generated.

4.4 Affinity protein purification of RGGs from E. coli and Arabidopsis suspension cells

Arabidopsis suspension-cultured PSB-D cells were maintained and transformed as previously described (Van Leene et al. 2011). Affinity-purification of RGGB-GS from cultured suspension cells was performed and analyzed as described in (Antosz et al. 2017). His6-MBP-RGGA, His6-MBP-RGGB and His6-MBP-RGGC were expressed in NiCo21(DE3) by induction with 1 mM IPTG at an OD600 of 0.4. After 4 h at 37 °C cells were collected and resuspended in buffer A (50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 0.5 % (v/v) Tween20®) + Protease Inhibitor (Roche) + Benzonase® Nuclease and lysed by sonication. The supernatant (after 12,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C) was incubated with Ni-Sepharose6 Fast flow resin (GE Healthcare) for 30 min. Beads were washed five times with buffer A + 50 mM imidazole followed by elution with buffer A + 500 mM imidazole. Eluates were dialyzed against ice cold protein buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2), using 10 K MWCO SnakeSkin (Thermo Scientific). After concentrating 5 ml dialysates with Amicon® Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (30 kDa MWCO) to 500 µl, target proteins were further purified using the Superdex200 Increase 10/300 GL column at an ÄKTA pure chromatography system (Cytiva).

4.5 MicroScale thermophoresis (MST) assays

To test the binding affinity of AtRGG proteins with nucleic acids, microscale thermophoresis (MST) assays were carried out with a Monolish NT.115 (NanoTemper Technologies) as described previously (Ehrnsberger et al. 2019). RGG proteins were mixed with 200 nM 25-nt Cy3-labeled ssRNA, dsRNA, ssDNA or dsDNA oligonucleotides. Samples were loaded into glass capillaries (NT.115 Standard Treated Capillaries) and measured at 40 % MST power and 50 % LED power. Recorded data were analyzed with MO.Affinity Analysis Software v2.3 (NanoTemper Technologies).

4.6 Electromobility shift assays (EMSAs)

Annealed Pentaprobe PP1 Oligos (Bendak et al. 2012) was used to test dsDNA binding capacity. ssRNA pentaprobe was generated by in vitro transcription from PP1 cloned into pCRTM Blunt II-TOPO® vectors (Thermo Scientific). ssRNA probe was synthesized using HiScribe™ T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB). 150 ng nucleic acid probes were each incubated with RGG protein in gel shift buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8, 15 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 10 % glycerol, 0.1 % TritonX100) at room temperature for 30 min. Reactions were separated in a 6 % native acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (29:1) gel in TBE buffer. Nucleic acid probes were stained using SYBR® Green EMSA gel stain (Molecular ProbesTM).

4.7 In vitro translation assay

The Wheat germ extract (Promega), a cell-free eukaryotic translation system, was used to study the effect of AtRGGs on translation. In a standard translation reaction, 1 µg Luciferase control mRNA and 10 µg purified RGG protein (or buffer) was added. After 2 h at 23 °C Luciferase was quantified by ONE-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System (Promega) measured in a SPARK® multimode microplate reader (TECAN).

4.8 Yeast transformation and growth assays

Yeast strains were grown in YPD medium or in YGP medium. Transformation of yeast strains was performed as described (Gietz and Schiestl 2007). Yeast strains transformed with galactose-inducible expression vector pBG1805 (Ura3) (Gelperin et al. 2005) were selected and propagated on synthetic defied (SD) medium-URA. For growth assays, pre-cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.5 and 10 µl spread on YPD with or without 100 ng/ml rapamycin. Plates were incubated at 30 °C and documented at indicated time points. Δstm1 (YLR150W; Clone ID 4107; MATa) and the parental strain (BY4741; MATa, his3Δ1, leu2Δ0, met15, Δ0, ura3 Δ0) were obtained from the DharmaconTM HorizonTM yeast knockout collection. Strains were genotyped by PCR using the primers BLA_Y_A_F and BLA_Y_D_R (Table S1) flanking the replaced region. The junctions of the disruption were verified by amplification using mutant-specific primers BLA_Y_A_F and KanB as well as wt specific primers BLA_Y_C_F and BLA_Y_D_R.

4.9 Polysome profiling

500 mg seedling material was ground in liquid nitrogen and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche), 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide). Crude extract was cleared by centrifugation (20,000 g; 10 min, 4 °C). RNA concentration was determined photometrically and extract containing 300 µg of total RNA was loaded onto a linear 10–50 % (w/v) sucrose gradient (12 ml) in lysis buffer. After centrifugation (35 000 rpm for 3 h at 4 °C in SW41Ti rotor (Beckman Instruments)) UV absorbance at 254 nm was monitored during gradient fractionation using an ÄKTA pure chromatography system (Cytiva). 400 μl fractions were TCA-precipitated before Western blot analysis.

Yeast was grown 2 days in SD Medium-URA. 120 ml YPG medium was inoculated to an OD600 of ∼ 0.1 and incubated at 30 °C to an OD600 of 0.6. 100 ml cultures were treated with 100 μg/ml cycloheximide for 10 min on ice. Cells were harvested, washed with lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml cycloheximide, 0.2 mg/ml heparin) and cell pellets frozen in liquid nitrogen. Extracts of yeast cells were prepared by glass bead lysis in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris/Cl ph 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 100 µM cycloheximide). Extracts were cleared by centrifugation and extracts containing 200 µg of total RNA were separated in a linear 7–50 % sucrose (w/v) gradients in loading buffer (50 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.5, 50 mM NH4Cl, 12 mM MgCl2). After centrifugation (2:45 h; 39,000 rpm; 4 °C; Beckmann Sw41Ti rotor) the gradient was fractionated and analyzed as describe before.

20 µl of each fraction was used to analyze protein distribution by Western Blot. Blots were sliced horizontal into 2–3 parts to apply different antibodies simultaneously (anti-GFP from mouse (11814460001; MERCK) anti-RPS10 and anti-RPL5 from rabbits (Weis et al. 2015)); anti-HA from mouse (# 26183, Thermo Fisher); anit-RPL14 from rabbits. AtRGGB-specific peptide antibody (CGREGRGPREGNQRD) was isolated from rabbit (Pineda).

4.10 Microscopy

Fluorescent reporter lines were imaged using a Leica SP8 inverted confocal laser scanning microscope usings a 40× oil objective (Leica, 1.3 N.A.) or a 63× oil objective (Leica, 1.3 N.A.). GFP fluorescence was detected at 500–550 nm using a 488 nm laser. Propidium iodide was detected at 570–650 nm with 561 nm excitation.

4.11 Bioinformatic analyses

Protein domains were identified by SMART (Letunic and Bork 2018) and amino acid sequence alignments were generated by the T-coffee program (Di Tommaso et al. 2011). Sequence identity and similarity were quantified by the SIAS online tool (http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/sias.html) using the alignment produced by t-coffee relative to the length of the smallest sequence. RGG homologues of AtRGGB were identified by PANTHER TREE VIEWER (Mi et al. 2019). The phylogenetic tree was calculated by Simple Phylogeny (Madeira et al. 2022) and drawn by Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5 (Letunic and Bork 2021). Expression profiles were analyzed using Genevestigator (Hruz et al. 2008).

4.12 Accession numbers

All accession numbers are summarized in Table S2.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: Collaborative Research Centers SFB960

Acknowledgment

We thank Daniela Strauss for expert guidance and help in yeast cultivation and polysome profiling experiments. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge Noureddine Djella and Armin Hildebrand for plant care, Enrico Schleiff for sharing plant-specific antibodies detecting ribosomal proteins and Philipp Milkereit for sharing yeast-specific antibodies detecting ribosomal proteins. Furthermore, we would like to thank Joachim Griesenbeck for his continuous support and valuable discussions.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. TD conceived the original research plan and together with ABl planned and supervised the experiments. ABl and NS performed most of the experiments and analyzed data. LW contributed with MST data and HFE, PH and PD with biochemical and phenotypic studies. SR as well as JM supported polysome profiling studies and KDG supervised experiments performed by HFE and PH and contributed to the discussion. The manuscript was written by ABl with PD and TD and input from JM and KDG.

-

Competing interests: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the German Research Council DFG via Collaborative Research Centers SFB960 to JM, KDG and TD, and SFB924 to PD and TD.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Ambrosone, A., Batelli, G., Nurcato, R., Aurilia, V., Punzo, P., Bangarusamy, D.K., Ruberti, I., Sassi, M., Leone, A., Costa, A., et al.. (2015). The Arabidopsis RNA-binding protein AtRGGA regulates tolerance to salt and drought stress. Plant Physiol. 168: 292–306, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.255802.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Antosz, W., Pfab, A., Ehrnsberger, H.F., Holzinger, P., Köllen, K., Mortensen, S.A., Bruckmann, A., Schubert, T., Längst, G., Griesenbeck, J., et al.. (2017). The composition of the Arabidopsis RNA polymerase II transcript elongation complex reveals the interplay between elongation and mRNA processing factors. Plant Cell 29: 854–870, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.16.00735.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Balagopal, V. and Parker, R. (2011). Stm1 modulates translation after 80S formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 17: 835–842, https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.2677311.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Balagopal, V. and Parker, R. (2009). Polysomes, P bodies and stress granules: states and fates of eukaryotic mRNAs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 21: 403–408, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Baudin, A., Xu, X., and Libich, D.S. (2021). The 1H, 15N and 13C resonance assignments of the C-terminal domain of Serpine mRNA binding protein 1 (SERBP1). Biomol. NMR Assign. 15: 461–466, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12104-021-10046-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ben-Shem, A., Garreau de Loubresse, N., Melnikov, S., Jenner, L., Yusupova, G., and Yusupov, M. (2011). The structure of the eukaryotic ribosome at 3.0 Å resolution. Science 334: 1524–1529, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212642.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bendak, K., Loughlin, F.E., Cheung, V., O’Connell, M.R., Crossley, M., and Mackay, J.P. (2012). A rapid method for assessing the RNA-binding potential of a protein. Nucl. Acids Res. 40: e105, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks285.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Blanchet, S. and Ranjan, N. (2022). Translation phases in eukaryotes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2533: 217–228, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2501-9_13.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Brown, A., Baird, M.R., Yip, M.C., Murray, J., and Shao, S. (2018). Structures of translationally inactive mammalian ribosomes. eLife 7: 1–18, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.40486.Search in Google Scholar

Browning, K.S. and Bailey-Serres, J. (2015). Mechanism of cytoplasmic mRNA translation. Arab B 13: e0176, https://doi.org/10.1199/tab.0176.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Brugier, A., Hafirrassou, M.L., Pourcelot, M., Baldaccini, M., Kril, V., Couture, L., Kümmerer, B.M., Gallois-Montbrun, S., Bonnet-Madin, L., Vidalain, P.-O., et al.. (2022). RACK1 associates with RNA-binding proteins vigilin and SERBP1 to facilitate dengue virus replication. J. Virol. 96: 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01962-21.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chen, Y., Liu, M., and Dong, Z. (2021). Preferential ribosome loading on the stress-upregulated mRNA pool shapes the selective translation under stress conditions. Plants 10: 304, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020304.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cheong, B.E., Beine-Golovchuk, O., Gorka, M., Ho, W.W.H., Martinez-Seidel, F., Firmino, A.A.P., Skirycz, A., Roessner, U., and Kopka, J. (2021). Arabidopsis REI-LIKE proteins activate ribosome biogenesis during cold acclimation. Sci. Rep. 11: 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81610-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Clough, S.J. and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16: 735–743, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Colleti, C., Melo-Hanchuk, T.D., da Silva, F.R.M., Saito, Â., and Kobarg, J. (2019). Complex interactomes and post-translational modifications of the regulatory proteins HABP4 and SERBP1 suggest pleiotropic cellular functions. World J. Biol. Chem. 10: 44–64, https://doi.org/10.4331/wjbc.v10.i3.44.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Cottilli, P., Itoh, Y., Nobe, Y., Petrov, A.S., Lisón, P., Taoka, M., and Amunts, A. (2022). Cryo-EM structure and rRNA modification sites of a plant ribosome. Plant Commun. 3: 100342, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2022.100342.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Despic, V. and Neugebauer, K.M. (2018). RNA tales – how embryos read and discard messages from mom. J. Cell Sci. 131: jcs201996, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.201996.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Duarte-Conde, J.A., Sans-Coll, G., and Merchante, C. (2022). RNA-binding proteins and their role in translational regulation in plants. Essays Biochem. 66: 87–97, https://doi.org/10.1042/ebc20210069.Search in Google Scholar

Van Dyke, M.W., Nelson, L.D., Weilbaecher, R.G., and Mehta, D.V. (2004). Stm1p, a G4 quadruplex and purine motif triplex nucleic acid-binding protein, interacts with ribosomes and subtelomeric Y′ DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 24323–24333, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m401981200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Van Dyke, N., Baby, J., and Van Dyke, M.W. (2006). Stm1p, a ribosome-associated protein, is important for protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under nutritional stress conditions. J. Mol. Biol. 358: 1023–1031, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Van Dyke, N., Chanchorn, E., and Van Dyke, M.W. (2013). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Stm1p facilitates ribosome preservation during quiescence. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 430: 745–750, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.078.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Van Dyke, N., Pickering, B.F., and Van Dyke, M.W. (2009). Stm1p alters the ribosome association of eukaryotic elongation factor 3 and affects translation elongation. Nucl. Acids Res. 37: 6116–6125, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp645.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Edwards, J.M., Roberts, T.H. and Atwell, B.J. (2012). Quantifying ATP turnover in anoxic coleoptiles of rice (Oryza sativa) demonstrates preferential allocation of energy to protein synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 63: 4389–4402, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers114.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ehrnsberger, H.F., Pfaff, C., Hachani, I., Flores-Tornero, M., Sørensen, B.B., Längst, G., Sprunck, S., Grasser, M., and Grasser, K.D. (2019). The UAP56-interacting export factors UIEF1 and UIEF2 function in mRNA export. Plant Physiol. 179: 1525–1536, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.18.01476.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Floris, M., Bassi, R., Robaglia, C., Alboresi, A., and Lanet, E. (2013). Post-transcriptional control of light-harvesting genes expression under light stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 82: 147–154, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-013-0046-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Frantz, J.D. and Gilbert, W. (1995). A yeast gene product, G4p2, with a specific affinity for quadruplex nucleic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 9413–9419, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.270.16.9413.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Gelperin, D.M., White, M.A., Wilkinson, M.L., Kon, Y., Kung, L.A., Wise, K.J., Lopez-Hoyo, N., Jiang, L., Piccirillo, S., Yu, H., et al.. (2005). Biochemical and genetic analysis of the yeast proteome with a movable ORF collection. Genes Dev. 19: 2816–2826, https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1362105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Giaever, G. and Nislow, C. (2014). The yeast deletion collection: a decade of functional genomics. Genetics 197: 451–465, https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.114.161620.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gietz, R.D. and Schiestl, R.H. (2007). High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat. Protoc. 2: 31–34, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.13.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Griffin, B.D. and Bass, H.W. (2018). Review: plant G-quadruplex (G4) motifs in DNA and RNA; abundant, intriguing sequences of unknown function. Plant Sci. 269: 143–147, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.01.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hayashi, H., Nagai, R., Abe, T., Wada, M., Ito, K., and Takeuchi-Tomita, N. (2018). Tight interaction of eEF2 in the presence of Stm1 on ribosome. J. Biochem. 163: 177–185, https://doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvx070.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hershey, J.W.B., Sonenberg, N., and Mathews, M.B. (2012). Principles of translational control: an overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4: a011528, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a011528.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Hruz, T., Laule, O., Szabo, G., Wessendorp, F., Bleuler, S., Oertle, L., Widmayer, P., Gruissem, W., and Zimmermann, P. (2008) Genevestigator V3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv. Bioinform. 2008: 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/420747,Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Juntawong, P. and Bailey-Serres, J. (2012). Dynamic light regulation of translation status in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 3: 66, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2012.00066.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kosmacz, M., Gorka, M., Schmidt, S., Luzarowski, M., Moreno, J.C., Szlachetko, J., Leniak, E., Sokolowska, E.M., Sofroni, K., Schnittger, A., et al.. (2019). Protein and metabolite composition of Arabidopsis stress granules. New Phytol. 222: 1420–1433, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15690.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Van Leene, J., Eeckhout, D., Cannoot, B., De Winne, N., Persiau, G., Van De Slijke, E., Vercruysse, L., Dedecker, M., Verkest, A., Vandepoele, K., et al.. (2015). An improved toolbox to unravel the plant cellular machinery by tandem affinity purification of Arabidopsis protein complexes. Nat. Protoc. 10: 169–187, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2014.199.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Van Leene, J., Eeckhout, D., Persiau, G., Van De Slijke, E., Geerinck, J., Van Isterdael, G., Witters, E., and De Jaeger, G. (2011). Isolation of transcription factor complexes from Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures by tandem affinity purification. In: Yuan, L. and Perry, S.E. (Eds.), Methods Mol. Biol. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 195–218.10.1007/978-1-61779-154-3_11Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Letunic, I. and Bork, P. (2018). 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucl. Acids Res. 46: D493–D496, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx922.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Letunic, I. and Bork, P. (2021). Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucl. Acids Res. 49: W293–W296, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab301.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Lightfoot, H.L., Hagen, T., Tatum, N.J., and Hall, J. (2019). The diverse structural landscape of quadruplexes. FEBS Lett. 593: 2083–2102, https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.13547.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Liu, M.-J., Wu, S.-H., Wu, J.-F., Lin, W.-D., Wu, Y.-C., Tsai, T.-Y., Tsai, H.-L., and Wu, S.-H. (2013). Translational landscape of photomorphogenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 3699–3710, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.114769.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Liu, M.-J., Wu, S., Chen, H.-M., and Wu, S.-H. (2012). Widespread translational control contributes to the regulation of Arabidopsis photomorphogenesis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 8: 566, https://doi.org/10.1038/msb.2011.97.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Madeira, F., Pearce, M., Tivey, A.R.N., Basutkar, P., Lee, J., Edbali, O., Madhusoodanan, N., Kolesnikov, A., and Lopez, R. (2022). Search and sequence analysis tools services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucl. Acids Res. 50: W276–W279, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac240.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Martinez-Seidel, F., Suwanchaikasem, P., Nie, S., Leeming, M.G., Pereira Firmino, A.A., Williamson, N.A., Kopka, J., Roessner, U., and Boughton, B.A. (2021). Membrane-enriched proteomics link ribosome accumulation and proteome reprogramming with cold acclimation in barley root meristems. Front. Plant Sci. 12: 1–21, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.656683.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mateos, J.L., de Leone, M.J., Torchio, J., Reichel, M., and Staiger, D. (2018). Beyond transcription: fine-tuning of circadian timekeeping by post-transcriptional regulation. Genes (Basel) 9: 616, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9120616.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Merchante, C., Stepanova, A.N., and Alonso, J.M. (2017). Translation regulation in plants: an interesting past, an exciting present and a promising future. Plant J. 90: 628–653, https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13520.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mi, H., Muruganujan, A., Huang, X., Ebert, D., Mills, C., Guo, X., and Thomas, P.D. (2019). Protocol Update for large-scale genome and gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system (v.14.0). Nat. Protoc. 14: 703–721, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-019-0128-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Muto, A., Sugihara, Y., Shibakawa, M., Oshima, K., Matsuda, T., and Nadano, D. (2018). The mRNA‐binding protein Serbp1 as an auxiliary protein associated with mammalian cytoplasmic ribosomes. Cell Biochem. Funct. 36: 312–322, https://doi.org/10.1002/cbf.3350.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Nallamsetty, S., Austin, B.P., Penrose, K.J., and Waugh, D.S. (2005). Gateway vectors for the production of combinatorially-tagged His 6 -MBP fusion proteins in the cytoplasm and periplasm of Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 14: 2964–2971, https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.051718605.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Pal, S.K., Liput, M., Piques, M., Ishihara, H., Obata, T., Martins, M.C.M., Sulpice, R., van Dongen, J.T., Fernie, A.R., Yadav, U.P., et al.. (2013). Diurnal changes of polysome loading track sucrose content in the rosette of wild-type Arabidopsis and the starchless pgm mutant. Plant Physiol. 162: 1246–1265, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.112.212258.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Piques, M., Schulze, W.X., Höhne, M., Usadel, B., Gibon, Y., Rohwer, J., and Stitt, M. (2009). Ribosome and transcript copy numbers, polysome occupancy and enzyme dynamics in Arabidopsis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5: 314, https://doi.org/10.1038/msb.2009.68.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Poole, E. and Sinclair, J. (2022). Latency-associated upregulation of SERBP1 is important for the recruitment of transcriptional repressors to the viral major immediate early promoter of human cytomegalovirus during latent carriage. Front. Microbiol. 13: 1–9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.999290.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rhodes, D. and Lipps, H.J. (2015). G-quadruplexes and their regulatory roles in biology. Nucl. Acids Res. 43: 8627–8637, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv862.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shetty, S., Hofstetter, J., Battaglioni, S., Ritz, D., and Hall, M.N. (2023). TORC1 phosphorylates and inhibits the ribosome preservation factor Stm1 to activate dormant ribosomes. EMBO J. 1–15, https://doi.org/10.15252/embj.2022112344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Smith, P.R., Loerch, S., Kunder, N., Stanowick, A.D., Lou, T.-F., and Campbell, Z.T. (2021). Functionally distinct roles for eEF2K in the control of ribosome availability and p-body abundance. Nat. Commun. 12: 6789, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27160-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Stahl, Y., Grabowski, S., Bleckmann, A., Kühnemuth, R., Weidtkamp-Peters, S., Pinto, K.G., Kirschner, G.K., Schmid, J.B., Wink, R.H., Hülsewede, A., et al.. (2013). Moderation of Arabidopsis root stemness by CLAVATA1 and ARABIDOPSIS CRINKLY4 receptor kinase complexes. Curr. Biol. 23: 362–371, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.045.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Teng, Y., Zhu, M., and Qiu, Z. (2023). G-quadruplexes in repeat expansion disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24: 2375, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032375.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Di Tommaso, P., Moretti, S., Xenarios, I., Orobitg, M., Montanyola, A., Chang, J.-M., Taly, J.-F., and Notredame, C. (2011). T-Coffee: a web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and RNA sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucl. Acids Res. 39: W13–W17, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr245.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Wang, Z.-P., Xing, H.-L., Dong, L., Zhang, H.-Y., Han, C.-Y., Wang, X.-C., and Chen, Q.-J. (2015). Egg cell-specific promoter-controlled CRISPR/Cas9 efficiently generates homozygous mutants for multiple target genes in Arabidopsis in a single generation. Genome Biol. 16: 144, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0715-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Webb, A.A.R., Seki, M., Satake, A., and Caldana, C. (2019). Continuous dynamic adjustment of the plant circadian oscillator. Nat. Commun. 10: 550, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08398-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Weis, B.L., Palm, D., Missbach, S., Bohnsack, M.T., and Schleiff, E. (2015). atBRX1-1 and atBRX1-2 are involved in an alternative rRNA processing pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. RNA 21: 415–425, https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.047563.114.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Winzeler, E.A., Shoemaker, D.D., Astromoff, A., Liang, H., Anderson, K., Andre, B., Bangham, R., Benito, R., Boeke, J.D., Bussey, H., et al.. (1999). Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285: 901–906, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5429.901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Yan, K.K.-P., Obi, I., and Sabouri, N. (2021). The RGG domain in the C-terminus of the DEAD box helicases Dbp2 and Ded1 is necessary for G-quadruplex destabilization. Nucl. Acids Res. 49: 8339–8354, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab620.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Yuan, Y., Zhou, D., Chen, F., Yang, Z., Gu, W., and Zhang, K. (2022). SIX5-activated LINC01468 promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression by recruiting SERBP1 to regulate SERPINE1 mRNA stability and recruiting USP5 to facilitate PAI1 protein deubiquitylation. Cell Death Dis. 13: 312, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-04717-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2023-0171).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: CRC 960 - RNP Biogenesis

- Guest Editorial

- Highlight: how to synthesize, assemble and regulate ribonucleoprotein-complexes

- Initial Steps of RNP Biogenesis

- Features of yeast RNA polymerase I with special consideration of the lobe binding subunits

- Synthesis of the ribosomal RNA precursor in human cells: mechanisms, factors and regulation

- Cellular Functions of RNPs

- The human long non-coding RNA LINC00941 and its modes of action in health and disease

- The chromatin – triple helix connection

- Post-transcriptional gene silencing in a dynamic RNP world

- Cytosolic RGG RNA-binding proteins are temperature sensitive flowering time regulators in Arabidopsis

- The archaeal Lsm protein from Pyrococcus furiosus binds co-transcriptionally to poly(U)-rich target RNAs

- RNP Turnover

- A structural biology view on the enzymes involved in eukaryotic mRNA turnover

- RNP Analysis

- Detection of a 7SL RNA-derived small non-coding RNA using Molecular Beacons in vitro and in cells

- RBPome identification in egg-cell like callus of Arabidopsis

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: CRC 960 - RNP Biogenesis

- Guest Editorial

- Highlight: how to synthesize, assemble and regulate ribonucleoprotein-complexes

- Initial Steps of RNP Biogenesis

- Features of yeast RNA polymerase I with special consideration of the lobe binding subunits

- Synthesis of the ribosomal RNA precursor in human cells: mechanisms, factors and regulation

- Cellular Functions of RNPs

- The human long non-coding RNA LINC00941 and its modes of action in health and disease

- The chromatin – triple helix connection

- Post-transcriptional gene silencing in a dynamic RNP world

- Cytosolic RGG RNA-binding proteins are temperature sensitive flowering time regulators in Arabidopsis

- The archaeal Lsm protein from Pyrococcus furiosus binds co-transcriptionally to poly(U)-rich target RNAs

- RNP Turnover

- A structural biology view on the enzymes involved in eukaryotic mRNA turnover

- RNP Analysis

- Detection of a 7SL RNA-derived small non-coding RNA using Molecular Beacons in vitro and in cells

- RBPome identification in egg-cell like callus of Arabidopsis