Abstract

Substrate-binding proteins (SBPs) are part of solute transport systems and serve to increase substrate affinity and uptake rates. In contrast to primary transport systems, the mechanism of SBP-dependent secondary transport is not well understood. Functional studies have thus far focused on Na+-coupled Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters for sialic acid. Herein, we report the in vitro functional characterization of TAXIPm-PQM from the human pathogen Proteus mirabilis. TAXIPm-PQM belongs to a TRAP-subfamily using a different type of SBP, designated TRAP-associated extracytoplasmic immunogenic (TAXI) protein. TAXIPm-PQM catalyzes proton-dependent α-ketoglutarate symport and its SBP is an essential component of the transport mechanism. Importantly, TAXIPm-PQM represents the first functionally characterized SBP-dependent secondary transporter that does not rely on a soluble SBP, but uses a membrane-anchored SBP instead.

1 Introduction

Solute uptake systems in prokaryotes and archaea commonly involve a substrate-binding protein (SBP) to enhance their affinity and specific uptake rate (Bosdriesz et al. 2015). SBPs are best known in the context of primary transport systems, i.e., ATP-binding cassette (ABC) importers (Davidson and Maloney 2007; Lewinson and Livnat-Levanon 2017), but are also found as part of secondary transporters (Forward et al. 1997; Jacobs et al. 1996) whose transport mechanism is less well understood. Known SBP-dependent secondary transport systems are symporters that use Na+-gradients to drive the import of amino acids, N-acetylneuraminic acids, (aromatic) dicarboxylates, α-keto acids, and even hydrophobic compounds (Brautigam et al. 2012; Deka et al. 2012; Gautom et al. 2021; Mulligan et al. 2009, 2011; Vetting et al. 2015).

Based on sequence dissimilarity, SBP-dependent secondary transport systems are organized in the Tripartite ATP-independent Periplasmic (TRAP)- and the Tripartite Tricarboxylate Transporter (TTT)-families (Kelly and Thomas 2001; Winnen et al. 2003). Both families have an identical tripartite organization involving a small and large membrane domain of approximately 4 and 12 transmembrane segments, respectively, in addition to the SBP. Gene fusions of the small and large membrane subunits are commonly found in both families (Rosa et al. 2018). Within the TRAP family two types of SBPs are found that differ with respect to their structure. The most common form is represented by DctP from Rhodobacter capsulatus (Forward et al. 1997) that is assigned to cluster E in the structural classification of SBPs (Scheepers et al. 2016), similar to the SBPs found in the TTT family. The second family of SBPs used by TRAP transporters is represented by the glutamate-binding protein TTHA115 from Thermus thermophilus (Takahashi et al. 2004) that is part of cluster F. They are referred to as TAXI proteins, for TRAP-Associated eXtracytoplasmic Immunogenic proteins (Kelly and Thomas 2001). These proteins are less abundant than DctP-like SBPs in bacteria, but are the only type associated with TRAP transporters in archaea. To aid discrimination, here we refer to TRAP transporters using DctP-like SBPs or TAXI-SBPs as TRAP-and TAXI-transport systems, respectively.

Detailed in vitro characterization of SBP-dependent secondary transporters has thus far been limited to the TRAP transporters for sialic acids from Haemophilus influenzae, Vibrio cholerae, and Photobacterium profundum (Davies et al. 2023; Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012). These systems are composed of SiaP, a soluble DctP-like SBP, the small membrane subunit SiaQ, and the large membrane unit SiaM. The SiaP of these TRAP transporters generally binds the sialic acid N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) with high affinity (sub-micromolar) and in a 1:1 stoichiometry (Müller et al. 2006; Mulligan et al. 2009). In the absence of SiaP no transport is observed, highlighting the essential role of the SBP in the transport process. As transport could not be restored by the addition of a SiaP-homolog from a different species, the membrane domains and the SBP are thought to interact directly (Mulligan et al. 2009). The membrane subunits SiaQ and SiaM form a strong complex even in TRAP systems where both are expressed as separate proteins (Mulligan et al. 2012). In addition to SiaP, both SiaQ and SiaM are indispensable for transport.

All three characterized SiaPQM systems are symporters that use Na+-gradients to drive uptake (Davies et al. 2023; Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012). As SiaPQM-mediated uptake of anionic Neu5Ac is accelerated by a negative-inside membrane potential, the stoichiometry of Na+:Neu5Ac is at least 2:1. Conventional secondary transporters operate bidirectionally, that is the direction of transport depends on the sum of the gradients imposed. An interesting consequence of the implementation of an SBP is that this renders SBP-dependent secondary transporters essentially unidirectional (Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012). Only upon the addition of a large excess of unliganded SiaP the direction of transport could be reversed.

Recent structures of the SiaQM membrane domains from H. influenzae and P. profundum (Davies et al. 2023; Peter et al. 2022) have finally provided the first mechanistic insights into TRAP transporters. Both SiaQM structures highlight a heterodimer composed of one copy of each subunit. The large SiaM domain displays high structural similarity to the Na+-dependent dicarboxylate transporter VcINDY from V. cholerae (Mancusso et al. 2012). VcINDY is dimeric and uses an elevator-like transport mechanism involving the relative reorientation of a mobile ‘transport’ domain to an immobile ‘scaffold’ domain (Drew and Boudker 2016). All known elevator proteins are homo-oligomers and associate using their scaffold domains (Holzhuter and Geertsma 2020). Instead of self-associating with an opposing protomer, the scaffold domain of SiaM interacts with SiaQ, thereby forming the first ‘monomeric’ elevator protein. Biochemical and computational evidence suggests that SiaP interacts with both membrane subunits during the transport cycle (Davies et al. 2023; Ovchinnikov et al. 2014; Peter et al. 2022).

Thus far functional and structural studies have focused on TRAP-transporters only. Here we detail the first functional characterization of a TAXI-transport system in vitro under defined conditions and demonstrate that this system relies on membrane-anchored, rather than soluble SBPs.

2 Results

2.1 Deorphanization of TAXIPm-P

We selected the TAXIPm transporter from the Gram-negative pathogen Proteus mirabilis (Schaffer and Pearson 2015) based on the comparably high heterologous expression levels of the substrate binding protein TAXIPm-P and the membrane domain TAXIPm-QM in Escherichia coli. The latter is composed of a fusion of the small and large membrane domains Q and M, respectively, which is common for TAXI transport systems (Kelly and Thomas 2001). As the SBPs in these type of carriers are essential for transport and determine the substrate specificity (Mulligan et al. 2009), our deorphanization strategy initially focused on TAXIPm-P.

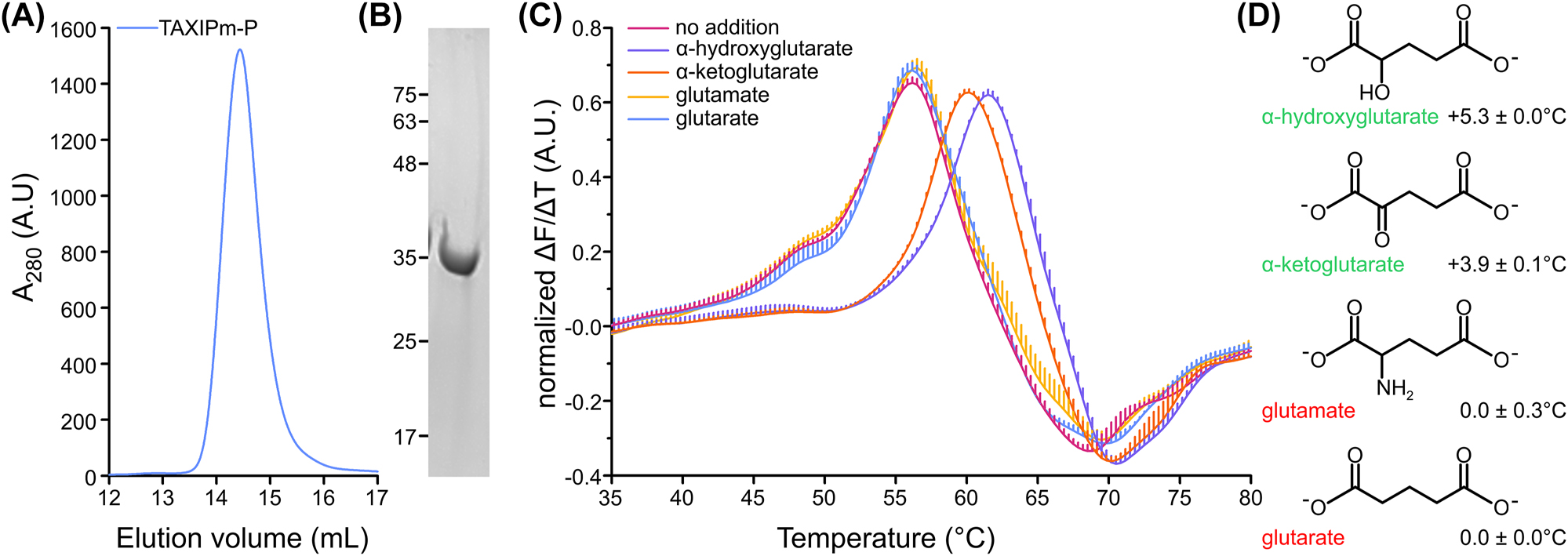

TAXIPm-P was produced without its 24 N-terminal amino acids as a soluble protein in the cytoplasm of E. coli and purified to homogeneity (Figure 1A and B). We used differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) to screen a library with 31 compounds including C4-, C5-dicarboxylates, amino acids, and other known ligands of TRAP transporters (Mulligan et al. 2011; Vetting et al. 2015) (Supplementary Figure 1). Apo-TAXIPm-P showed a slightly biphasic melting curve with the main melting point at 56 °C and a minor shoulder near 47 °C (Figure 1C). We observed reproducible shifts in the T m in the presence of α-hydroxyglutarate and α-ketoglutarate, but not in the presence of glutamate and glutarate (Figure 1C). This suggests that TAXIPm-P is highly selective as all four compounds are structurally-related and only differ in their substituents at C2 (Figure 1D). While the thermal stabilization (ΔT m ) of 5.3 ± 0.0 °C and 3.9 ± 0.1 °C for TAXIPm-P in the presence of α-hydroxyglutarate or α-ketoglutarate, respectively, appears modest, it correlates well with the substrate-induced stabilization observed previously for other substrate binding proteins of TRAP transporters (Gautom et al. 2021; Vetting et al. 2015). To explore the degree of ligand-induced stabilization in more detail we titrated α-ketoglutarate and followed protein unfolding (Supplementary Figure 2). While thermal stabilization initially increased up to a concentration of 12.5 µM with a ΔT m of 9.3 ± 0.1 °C, the degree of stabilization reduced to a ΔT m of only 4.0 ± 0.1 °C at 25 µM. At α-ketoglutarate concentrations of 50 µM and above no melting curve could be observed anymore, suggesting destabilization of the protein. The degree of thermal stabilization of TAXIPm-P thus depends on the substrate concentration used.

Deorphanization of TAXIPm-P. (A) Size-exclusion chromatography of IMAC-purified TAXIPm-P. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of the SEC-peak fraction. (C) Differential scanning fluorimetry of TAXIPm-P in the presence of buffer (designated “no addition”) or 40 µM α-hydroxyglutarate, α-ketoglutarate, glutamate, or glutarate. The peak in the normalized first derivative of the curve indicates the melting temperature. Curves represent average values of normalized data with standard errors of triplicates. For clarity only upward-facing error bars are shown. (D) Structures of the compounds tested in panel C. The change in melting temperature ± the standard error with respect to the ligand-free TAXIPm-P are indicated next to the compound name.

2.2 Substrate specificity of TAXIPm-P

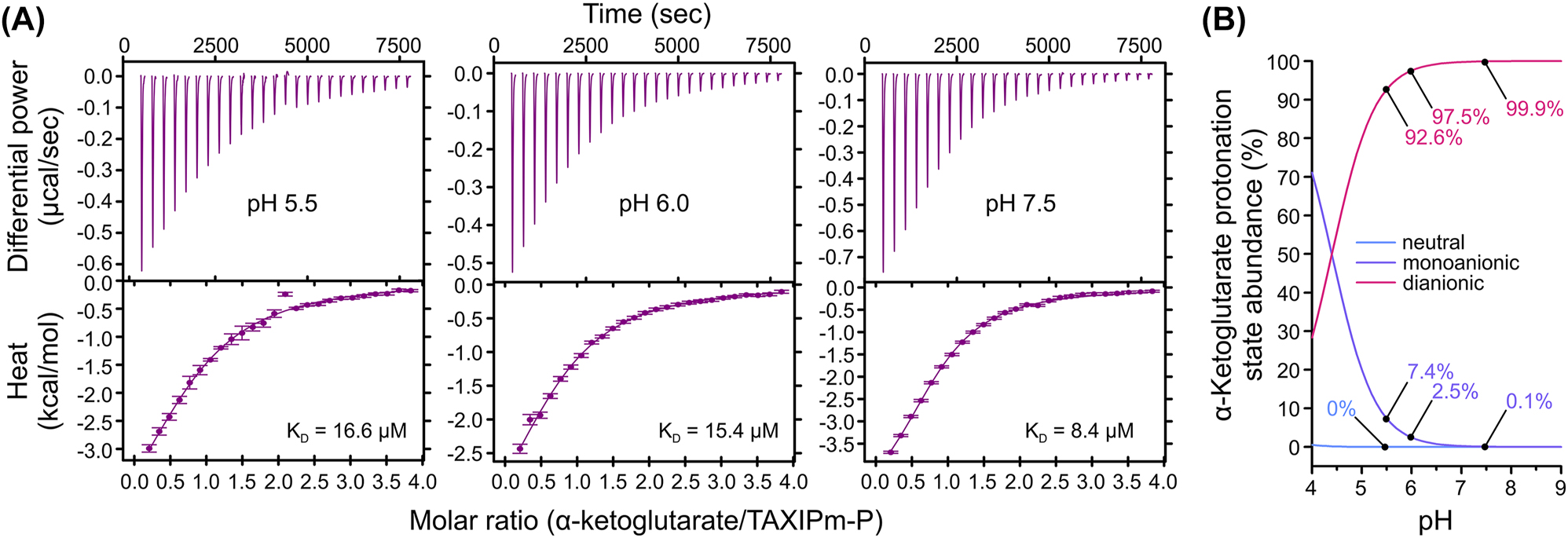

Both α-hydroxyglutarate and α-ketoglutarate are dicarboxylates. These compounds occur in three charge states, neutral, monoanionic, and dianionic, depending on the pH value. To determine which species of α-ketoglutarate binds to TAXIPm-P we performed isothermal calorimetry (ITC) at pH 5.5, 6.0, and 7.5 (Figure 2A). Binding of α-ketoglutarate proved exothermic and equilibrium dissociation constants of 16.6, 15.4, and 8.4 µM were determined at pH 5.5, 6.0, and 7.5, respectively. Based on the pK a values of 1.9 and 4.4 for α-ketoglutarate, the neutral form is an unlikely substrate given its negligible concentration even at the lowest pH value used (Figure 2B). The modest change in K D determined for binding at pH 5.5 and 7.5 does not reflect the 70-fold decrease in concentration of the monoanionic species, suggesting that neither monoanionic α-ketoglutarate is the exclusive substrate of TAXIPm-P. This is further supported by the molar ratios at which binding is saturated; these barely vary indicating that the concentration of the species that is bound does not change in the pH range tested. Taken together, these data suggest that TAXIPm-P either exclusively binds dianionic α-ketoglutarate, or that it is indiscriminate towards both the monoanionic and dianionic species.

pH-dependence in binding affinity of α-ketoglutarate to TAXIPm-P examined by ITC. (A) Top panels show the background-corrected raw heat exchange data associated with α-ketoglutarate binding to TAXIPm-P at pH 5.5 (left panel), pH 6.0 (middle panel), and pH 7.5 (right panel). Lower panels show the binding isotherms obtained from the integration of the heat pulses, normalized per mole of injection, and fitted by a one-site binding model. Individual KD values are indicated. (B) Percentage of abundance of the different α-ketoglutarate protonation states as a function of pH.

2.3 Deorphanization of TAXIPm-PQM

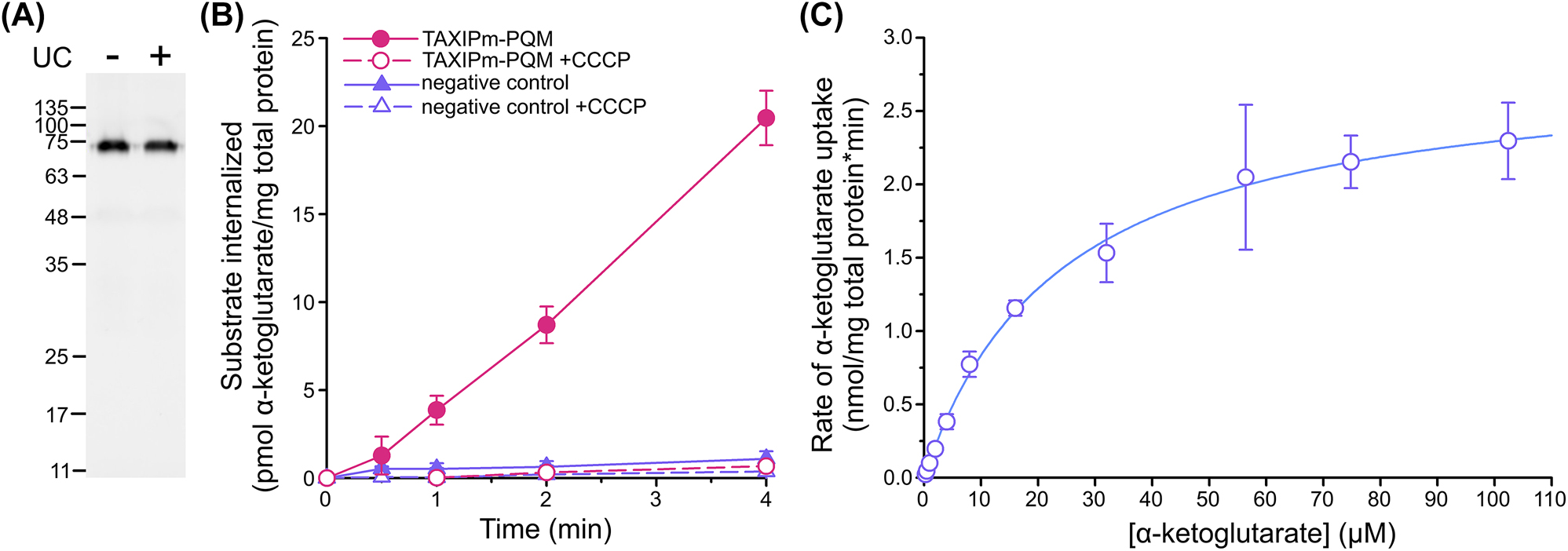

Both DSF and ITC demonstrated that TAXIPm-P binds α-ketoglutarate. To verify whether this compound is indeed transported by the TAXIPm-QM membrane domain, we established a transport assay in E. coli BW25113(ΔkgtP), which lacks the endogenous α-ketoglutarate permease KgtP (Seol and Shatkin 1992). TAXIPm-PQM was expressed using its native operon structure. The TAXIPm-P signal sequence was substituted with the one of SiaP from Haemophilus influenzae to improve expression levels of the complex and TAXIPm-QM was decorated with a carboxy-terminal GFP. We assessed the folding quality of the membrane domain by comparing the GFP intensity of a DDM-solubilized whole cell lysate before and after ultracentrifugation (Figure 3A) (Marino et al. 2017). As both samples show equal intensities, we conclude that TAXIPm-QM is well-folded under these conditions.

Cell-based transport assay for TAXIPm-PQM. (A) Assessment of the TAXIPm-PQM folding state upon expression in E. coli BW25113(ΔkgtP). In gel GFP fluorescence analysis of DDM-solubilized whole cell lysates before (minus) ultracentrifugation and the supernatant following ultracentrifugation (plus). (B) Time-dependent uptake of 2 µM α-ketoglutarate in E. coli BW25113 (ΔkgtP)/pEXC3sfGH-TAXIPm-PQM in the presence or absence of 10 µM CCCP. Curves represent average values with standard errors of triplicates. Control samples express TAXIMh-PQM from Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus in order to impose a similar degree of physiological stress from protein overexpression. (C) Kinetics of α-ketoglutarate uptake in E. coli BW25113 (ΔkgtP)/pEXC3sfGH-TAXIPm-PQM. Datapoints represent average values with standard errors of duplicates. The data were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

We observed robust TAXIPm-PQM-dependent α-ketoglutarate uptake in pre-energized cells, in agreement with the α-ketoglutarate binding to TAXIPm-P (Figure 3B). The transport was completely abolished upon the addition of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP). This preliminary analysis suggests that TAXIPm-QM is driven by the proton-motive force, though great care should be taken in dissecting driving forces in intact cells (Holzhuter and Geertsma 2022). We further determined an apparent KM for the complete TAXIPm-PQM transport system of 24 µM (Figure 3C), which approximates the K D determined for TAXIPm-P.

2.4 Characterization of mature TAXIPm-P

Determination of the forces driving solute uptake is best done in vitro. To this end we first purified TAXIPm-QM (Supplementary Figure 3A). Decylmaltoside-solubilized TAXIPm-QM eluted in two peaks during SEC, which may resemble different oligomeric states. Reconstitution into detergent-solubilized liposomes (Mulligan et al. 2009) was inefficient. Only a small fraction of the protein was associated with the liposomes and the majority of that could not be resolubilized from the proteoliposomes using detergent (Supplementary Figure 3B), suggestive of protein aggregation. In contrast, TAXIPm-QM was efficiently reconstituted using a milder approach relying on detergent-doped liposomes and less abrupt detergent removal (Geertsma et al. 2008) (Supplementary Figure 3B). Using proteoliposomes prepared by the latter method, we attempted to measure in vitro α-ketoglutarate uptake. However, despite the high reconstitution efficiency we reproducibly failed to measure any substrate transport in the presence of external soluble TAXIPm-P at a concentration of 5 µM while applying inwardly-directed proton-and sodium-gradients (Supplementary Figure 3C). Similar conditions were previously used successfully for the TRAP transport systems SiaPQM from H. influenzae and V. cholerae (Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012) and appeared to recapitulate all relevant aspects allowing TAXIPm-PQM mediated α-ketoglutarate uptake in intact cells (Figure 3B).

Ultimately, we identified potential differences between the substrate binding proteins used in our in vivo and in vitro transport assays. Substrate binding proteins in Gram-negative bacteria are mostly preceded by a signal sequence that guides the pre-protein into the secretory pathway. Following transport by the Sec translocon this signal sequence is cleaved by Signal Peptidase I and the mature protein remains in the periplasm as a soluble protein. Our implementation of the SiaP signal sequence preceding TAXIPm-P in the cell-based transport assays (Figure 3B) had been imperfect, resulting in a reduction of the cleavage efficiency according to a SignalP prediction (Supplementary Figure 4AB) (Teufel et al. 2022), and potentially leading to a fraction of TAXIPm-P still anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane. Full-length wildtype TAXIPm-P contains an N-terminal stretch of positively charged amino acids followed by a hydrophobic core of approximately 17 amino acids. Analysis by SignalP suggested that the N-terminus does not contain any conventional signal sequence (Supplementary Figure 4C). Our hypothesis was therefore that TAXIPm-P matures to a membrane-anchored periplasmic binding protein, and not a soluble one. To confirm this we expressed TAXIPm-P with and without the first N-terminal 24 amino acids. Analysis by Western blot revealed a higher apparent mass of the full-length protein (Figure 4A). Intact protein mass analysis of purified full-length TAXIPm-P demonstrated that only the N-terminal methionine was removed from the protein (Supplementary Figure 5). Together, this suggests that the N-terminus of TAXIPm-P is relevant for both exposing the substrate binding domain to the periplasm and anchoring it to the cytoplasmic membrane. The difference in the transport activities observed in the in vitro system (Supplementary Figure 3C) and the cell-based system (Figure 3B) might therefore result from the absence of the membrane anchor on TAXIPm-P in our initial in vitro setup. To pursue this hypothesis, we co-reconstituted the TAXIPm-PQM system using the full-length TAXIPm-P and tested for membrane-localization and transport.

![Figure 4:

In vitro transport assay for TAXIPm-PQM. (A) Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate from E. coli MC1061 expressing TAXIPm-P as soluble protein (SOL) or as full-length protein (FL). Proteins were detected using an anti-His antibody. (B) Size-exclusion chromatography of full-length TAXIPm-P, initially purified in the presence of 0.005% (w/v) Triton X-100. Purple and pink traces indicate the sample run in the absence of detergent, and subsequent analysis following addition of 0.2% (w/v) DM, respectively. (C) Assessment of the reconstitution efficiency of TAXIPm-PQM. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of DDM-solubilized proteoliposomes before (minus) ultracentrifugation and the supernatant following ultracentrifugation (plus). Black and white arrows indicate TAXIPm-QM and full-length TAXIPm-P, respectively. (D) Time-dependent uptake of 10 µM [14C]-α-ketoglutarate into TAXIPm-PQM proteoliposomes at 20 °C. H+, Na+, and α-ketoglutarate refer to inwardly-directed proton- (out: pH 6.0; in: pH 7.5), Na+- (out: 50 mM Na+; in: 50 mM K+; symmetrical pH 7.5 unless otherwise stated), and α-ketoglutarate-gradients (out: 10 µM; in: 0 µM; symmetrical pH 7.5 unless otherwise stated). (E) Uptake of 10 µM [14C]-α-ketoglutarate into TAXIPm-PQM proteoliposomes at 20 °C driven by a proton-gradient. Arrow indicates the timepoint at which 1 mM [12C]-α-ketoglutarate was added to the sample indicated by the orange trace. Datapoints in (D) and (E) represent average values with standard errors of triplicates.](/document/doi/10.1515/hsz-2022-0337/asset/graphic/j_hsz-2022-0337_fig_004.jpg)

In vitro transport assay for TAXIPm-PQM. (A) Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate from E. coli MC1061 expressing TAXIPm-P as soluble protein (SOL) or as full-length protein (FL). Proteins were detected using an anti-His antibody. (B) Size-exclusion chromatography of full-length TAXIPm-P, initially purified in the presence of 0.005% (w/v) Triton X-100. Purple and pink traces indicate the sample run in the absence of detergent, and subsequent analysis following addition of 0.2% (w/v) DM, respectively. (C) Assessment of the reconstitution efficiency of TAXIPm-PQM. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of DDM-solubilized proteoliposomes before (minus) ultracentrifugation and the supernatant following ultracentrifugation (plus). Black and white arrows indicate TAXIPm-QM and full-length TAXIPm-P, respectively. (D) Time-dependent uptake of 10 µM [14C]-α-ketoglutarate into TAXIPm-PQM proteoliposomes at 20 °C. H+, Na+, and α-ketoglutarate refer to inwardly-directed proton- (out: pH 6.0; in: pH 7.5), Na+- (out: 50 mM Na+; in: 50 mM K+; symmetrical pH 7.5 unless otherwise stated), and α-ketoglutarate-gradients (out: 10 µM; in: 0 µM; symmetrical pH 7.5 unless otherwise stated). (E) Uptake of 10 µM [14C]-α-ketoglutarate into TAXIPm-PQM proteoliposomes at 20 °C driven by a proton-gradient. Arrow indicates the timepoint at which 1 mM [12C]-α-ketoglutarate was added to the sample indicated by the orange trace. Datapoints in (D) and (E) represent average values with standard errors of triplicates.

2.5 Co-reconstitution of TAXIPm-PQM

A membrane-anchored substrate binding protein can only diffuse in a two-dimensional space. Given similar expression levels its effective concentration is therefore expected to greatly exceed that of a soluble version. The observed lack of α-ketoglutarate uptake when using soluble TAXIPm-P may therefore be explained by a low binding affinity of the membrane domain TAXIPm-QM for TAXIPm-P.

To determine whether a membrane-tethered TAXIPm-P facilitates uptake in the TAXIPm-PQM reconstituted system, we established a co-reconstitution procedure. Full-length TAXIPm-P was efficiently purified using DDM and Triton X-100 (Supplementary Figure 6). As we scrambled the orientation of TAXIPm-QM in our proteoliposomes by means of sonication, we aimed to co-reconstitute TAXIPm-P in a right-side-out orientation as this would allow exclusive functional analysis of the transport complexes in this respective orientation. To achieve unidirectional reconstitution, we opted to avoid the use of detergent as much as possible. Purified TAXIPm-P solubilized in Triton X-100 was therefore submitted to size-exclusion chromatography in the absence of detergent. This resulted in the formation of large aggregates of TAXIPm-P that eluted in the void volume of the column (Figure 4B). As addition of detergent did dissolve these clusters again, we assume that the overall folding state of the protein was not affected by this treatment. For co-reconstitution we added detergent-depleted TAXIPm-P to proteoliposomes already containing TAXIPm-QM. Using this approach we observed high reconstitution efficiencies for both proteins (Figure 4C).

2.6 In vitro characterization of TAXIPm-PQM

Using proteoliposomes containing TAXIPm-QM and membrane-anchored TAXIPm-P we observed robust uptake of α-ketoglutarate driven by a combined inwardly-directed proton- and Na+-gradient (Figure 4D). This confirms the absolute requirement of a membrane-tethered substrate binding protein for transport. Further dissection of the driving forces revealed that the proton-gradient alone suffices for transport. Since the rate of transport and the peak α-ketoglutarate accumulation level measured in the presence of a combined Na+- and proton-gradient are comparable to those observed in the presence of a proton-gradient alone, we postulate that TAXIPm-PQM is a proton-dependent symporter.

The directionality of TAXIPm-PQM was subsequently determined using a substrate counterflow experiment (Mulligan et al. 2009). Following an initial accumulation of radiolabeled α-ketoglutarate, we added a 100-fold excess of unlabeled substrate (Figure 4E). For conventional secondary transporters this results in an immediate exchange of the internalized substrate for the unlabeled external compound, thereby reducing the radioactivity in the lumen of the proteoliposomes significantly (Mulligan et al. 2009). Here we do not observe such an immediate strong reduction, suggesting that TAXIPm-PQM operates as a strict unidirectional uptake system.

3 Discussion

Our deorphanization effort for the TAXIPm-PQM system from P. mirabilis revealed that α-hydroxyglutarate and α-ketoglutarate are ligands for TAXIPm-P. While dicarboxylates have previously been identified as substrates for TRAP systems, this involved only C3- and C4-, but not the C5-dicarboxylates found here (Vetting et al. 2015). Within the same operon as the genes for TAXIPm-QM and TAXIPm-P (designated by locus tags PMI1055 and PMI1056, respectively) the lhgO gene coding for a putative L-2-hydroxyglutarate oxidase (PMI1053) is found (Price et al. 2005). L-2-hydroxyglutarate oxidases convert α-hydroxyglutarate into α-ketoglutarate (Kalliri et al. 2008). The close genomic proximity of these genes further strengthens the substrate specificity determined here by suggesting that the corresponding proteins are part of an α-hydroxyglutarate-uptake and -conversion pipeline. Alternatively, this operon may also represent two independent strategies both aimed at replenishing intracellular α-ketoglutarate, e.g., to complement the upregulation of enzymes responsible for the first steps of the tricarboxylic acid cycle observed for P. mirabilis in the urinary tract, which serves the same aim (Pearson et al. 2011).

Thus far all in vitro characterized TRAP transport systems are sodium-coupled (Davies et al. 2023; Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012). The proposed sodium binding sites are located in the M-domain (Supplementary Figure 7) and Na+ ion coordination mostly involves backbone oxygens (Davies et al. 2023). The M-domain of TRAP and TAXI transport systems shares its architecture with that of the SLC13 or divalent anion sodium-symporter (DASS) family (Davies et al. 2023; Peter et al. 2022). As clear from the latter designation, most of the SLC13 symporters are reported to be sodium-coupled as well (Bergeron et al. 2013; Hall and Pajor 2007; Mulligan et al. 2014; Pajor et al. 2013; Strickler et al. 2009; Youn et al. 2008). In contrast, the TAXIPm-PQM transport system studied here is a strict proton-dependent symporter, as suspected by the absence of α-ketoglutarate uptake in protonophore-treated cells (Figure 3) and subsequently confirmed using our in vitro transport assay (Figure 4).

In agreement with previous observations on SBP-dependent secondary transporters (Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012) and SBP-dependent primary transport systems (Shuman 1982), we observe that transport by TAXIPm-QM does not proceed in the absence of a binding protein, which in the case of TAXIPm-PQM needs to be anchored to the membrane (Supplementary Figure 3C). The fact that a soluble version of TAXIPm-P cannot replace membrane-attached TAXIPm-P suggests that the interaction between the SBP and the transport domain is less strong than that of transport systems relying on soluble SBPs, such as the SiaPQM systems from H. influenzae and V. cholerae (Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012). This may compensate for the increased apparent concentration of anchored SBPs, which can only diffuse in a two-dimensional plane. While conventional secondary transporters operate bidirectionally, the assimilation of an SBP in the transport cycle converts TAXIPm-PQM into a unidirectional transport system. Unidirectional transport had already been observed for secondary transporters relying on soluble binding proteins (Mulligan et al. 2009, 2012), and our data now indicates this also holds true for transport systems relying on membrane-anchored binding proteins (Figure 4E).

The identification of a transport system depending on an SBP that is tethered to the plasma-membrane is not unprecedented. In Gram-positive bacteria and archaea, which lack an outer membrane, membrane-anchoring often serves to retain the SBP at the cytoplasmic membrane and thereby prevent it from diffusing out of the cell. Tethering to the membrane can be achieved by an N-terminal lipid anchor (Sutcliffe and Russell 1995), fusion to the translocator protein (van der Heide and Poolman 2002), or an N-terminal transmembrane segment (Albers et al. 1999). Interestingly, P. mirabilis is a Gram-negative bacterium (Schaffer and Pearson 2015), implying that there is no obvious need to tether TAXIPm-P to the cytoplasmic membrane.

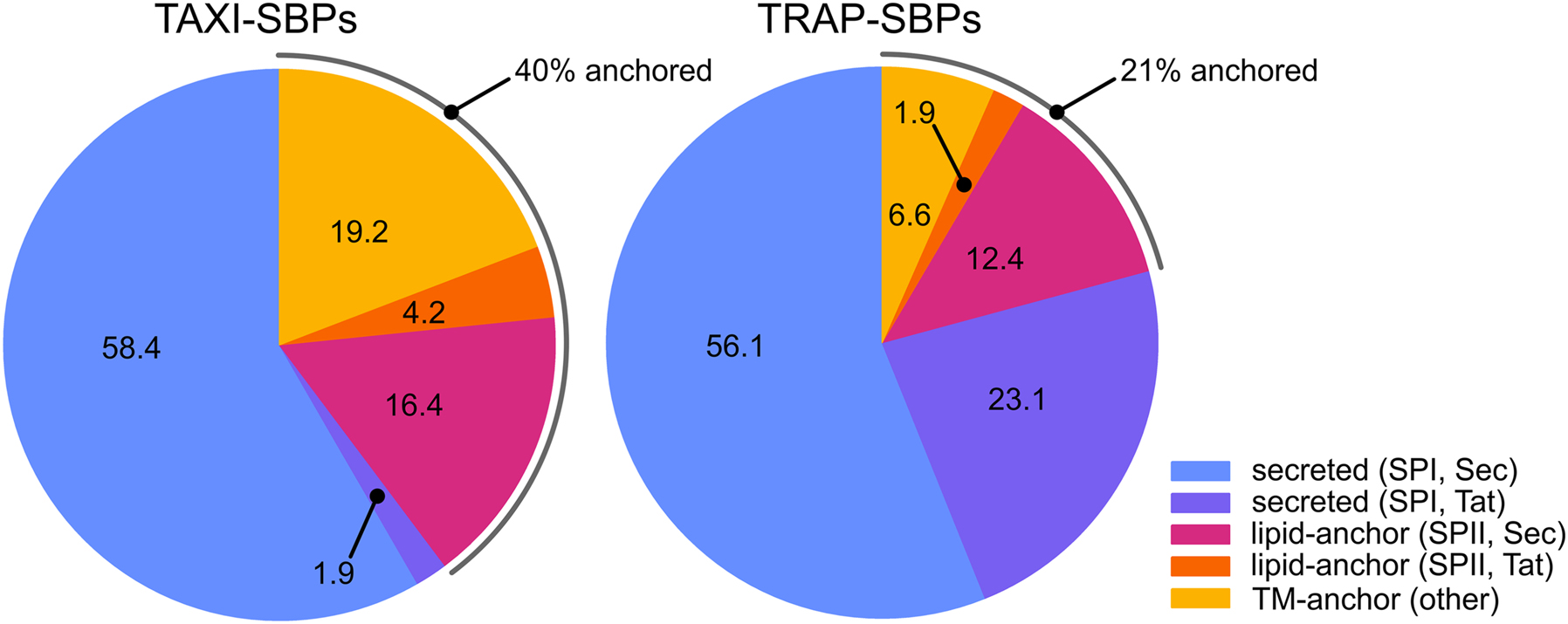

To determine whether membrane-anchoring is common amongst TAXI transport systems, we retrieved 215 and 636 unique SBP sequences of TAXI-and TRAP-systems from TRAPDB (Mulligan et al. 2007) and analyzed these in more detail (Figure 5). SignalP predicts that the majority of the SBPs in both systems are preceded by a conventional Signal Peptidase I signal sequence, in line with the common assumption that these proteins are soluble. If those proteins without any predicted signal sequence do functionalize their N-terminal hydrophobic sequence as a membrane anchor, a large fraction (19.2%) of transmembrane-anchors is observed for TAXI proteins. This fraction exceeds that of TRAP proteins using this mode of attachment by a factor of two, suggesting that membrane-anchors are more common for TAXI systems. Upon inclusion of lipid-anchored proteins, approximately 40% of the analyzed TAXI systems have membrane-immobilized SBPs versus 21% of the TRAP transporters. To some extent this difference will reflect a bias in our dataset due to the higher occurrence of TAXI systems in archaea (Kelly and Thomas 2001). Nevertheless, it highlights that membrane-tethered SBPs are common in both families.

Signal sequence variation in TAXI-and TRAP-SBPs. Pie charts representing the SignalP analysis of sequences of TAXI-and TRAP-SBPs obtained from TRAPDB. Numbers refer to the percentage of proteins with the respective signal sequence. The TAXI-SBP dataset consisted of 215 unique sequences with a maximum, minimum, median, and average identity of 99.7, 8.3, 23.4, and 25.9%, respectively. The TRAP-SBP dataset consisted of 636 unique sequences with a maximum, minimum, median, and average identity of 99.7, 7.0, 20.2, and 21.6%, respectively. SPI, SPII, Sec, and Tat refer to Signal Peptidase I, Signal Peptidase II, Sec translocon, and the Tat translocon, respectively. In this analysis ‘other’ refers to SBPs without any predicted signal sequence but with an N-terminal hydrophobic transmembrane segment.

Here we have demonstrated that the SBP-dependent secondary transporters TAXIPm-PQM, akin to certain ABC importers (van der Heide and Poolman 2002), relies on a membrane-anchored SBP. In Gram-positive bacteria and archaea the membrane-anchor serves primarily to tether the SBP to the cell and prevent its loss to the environment. We postulate that in Gram-negative bacteria the anchoring to the inner-membrane ensures a more economical alternative for soluble SBPs as high local SBP concentrations can be easily achieved, especially upon direct association of the SBP’s membrane-anchor with the membrane-embedded transport domain.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Cloning

Wild type genes of TAXIPm-P and TAXIPm-QM from P. mirabilis (ATCC 29,906) were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA, cloned into pINIT_cat by FX cloning (Geertsma and Dutzler 2011), and sequence verified prior to subcloning. The construction of pEXC3sfGH was based on the expression vector pES7SiaPQM (Mulligan et al. 2009). Following elimination of two endogenous SapI sites in the vector backbone, the sequence coding for the suicide cassette, a 3C protease site, superfolder GFP, and a decaHis tag was transferred from pBXC3sfGH to the vector backbone using Infusion cloning (Hamilton et al. 2007). The pEXC3sfGH harbors a pSC101 origin of replication and a bla marker, and allows expression of C-terminally superfolder-GFP- and decaHis-tagged protein from the lac promoter.

4.2 TAXIPm-P expression and purification

E. coli MC1061 transformed with the pBXNH3- or pBXC3H-vector containing the sequence coding for soluble or membrane-anchored TAXIPM-P was cultivated in TB medium supplemented with ampicillin at 37 °C. At an OD600 between 1.0 and 1.5 the temperature was shifted to 25 °C and 1 h later cells were induced by the addition of 0.01% (w/v) arabinose for 16 h. For purification of soluble TAXIPm-P cell pellets were stored at −20 °C until use. Cell pellets were resuspended in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol, supplemented with 1 mg/mL lysozyme, trace amounts of DNAse I, 2 mM MgSO4, and 15 mM imidazole, and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Cells were disrupted using a pressure cell homogenizer from Stanstedt. PMSF was added to 1 mM, and the lysate was cleared by ultracentrifugation (30 min at 186,000 g). All steps of protein purification were carried out at 4 °C. Protein was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC). Protein was eluted from the Ni-NTA resin using buffer supplemented with 300 mM imidazole, and subsequently treated with HRV 3C protease and dialyzed to 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol. Contaminants were removed by reverse-IMAC and following concentration the protein was subjected to size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL Increase column using 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl as running buffer. Protein-containing fractions were pooled, supplemented with 10% (w/v) glycerol, adjusted to a concentration of 10 mg/mL, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further usage.

For purification of membrane-anchored TAXIPm-P, cells were disrupted immediately following harvest. Unbroken cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation (30 min at 15,000 g) and membrane vesicles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation (1 h, 186,000 g), resuspended in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol to a concentration of 500 mg wet weight/mL, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until use. Membrane vesicles were solubilized for at least 1 h by ten-fold dilution in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol, and supplemented with 1.6% (w/v) dodecylmaltoside (DDM). Following removal of insoluble material by ultracentrifugation (30 min at 186,000 g), the solubilized membrane protein was purified by IMAC and SEC, essentially as detailed above but using buffers supplemented with 0.05% (w/v) Triton X-100. The peak fraction was submitted to another round of SEC using a running buffer devoid of detergent to assure reversible aggregation. Peak fractions were pooled, supplemented with 10% (w/v) glycerol, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further usage.

4.3 TAXIPm-QM expression and purification

E. coli MC1061 transformed with the pBXC3sfGH-vector containing the sequence coding for TAXIPm-QM was cultivated in TB medium supplemented with ampicillin at 37 °C. At an OD600 between 1.0 and 1.5 the temperature was shifted to 25 °C and 1 h later cells were induced by the addition of 0.01% (w/v) arabinose for 16 h. Cells were disrupted immediately following harvest. Unbroken cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation (30 min at 15,000 g) and membrane vesicles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation (1 h, 186,000 g), resuspended in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol to a concentration of 500 mg wet weight/mL, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until use. Membrane vesicles were solubilized for at least 1 h by ten-fold dilution in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol, and supplemented with 1.6% (w/v) decylmaltoside (DM). Following removal of insoluble material by ultracentrifugation (30 min at 186,000 g), the solubilized membrane protein was purified by IMAC, essentially as detailed above but using buffers supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) DM, and eluted from the column by a 2 h incubation with HRV 3C protease. The protein was subjected to SEC on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL Increase column using 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.2% (w/v) DM as running buffer. Protein-containing fractions were pooled, supplemented with 10% (w/v) glycerol, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further usage.

4.4 Reconstitution into liposomes

Proteoliposomes were essentially prepared as described previously (Chang et al. 2019; Geertsma et al. 2008). In brief, purified membrane proteins were mixed with Triton X-100-destabilized liposomes composed of L-α-phosphatidylcholine from soy bean at a weight-to-weight ratio of 1:50 (protein:lipid) and detergent was subsequently removed by step-wise addition of Biobeads (BioRad). The resulting proteoliposomes were collected by ultracentrifugation at 200,000 g for 30 min at 15 °C and resuspended in 50 mM KPi or NaPi, pH 7.5, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4 to a lipid concentration of 20 mg/mL. To randomize the orientation of the reconstituted protein the proteoliposomes were sonicated in six cycles (10 s on/50 s off). Proteoliposomes were subjected to five freeze/thaw cycles and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Reconstitution efficiency was determined as described (Holzhuter and Geertsma 2022). For co-reconstitution of membrane-anchored TAXIPm-P, TAXIPm-QM-containing proteoliposomes were thawed and extruded 11-fold through 400 nm pore size polycarbonate filters. Afterwards temporary aggregated TAXIPm-P holding its membrane-anchor was mixed with the proteoliposomes to achieve a TAXIPm-QM:TAXIPm-P ratio of 1:0.1 (weight-to-weight). The sample was incubated for 15 min at room temperature while rocking. Proteoliposomes were subsequently collected by ultracentrifugation (30 min at 200,000 g), resuspended in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, to a lipid concentration of 100 mg/mL.

4.5 Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF)

For DSF analysis, 10 µM soluble TAXIPm-P was mixed with potential ligands at a final concentration of 40 µM. Sypro Orange, purchased at a concentration of 5000Χ, was diluted 50-fold to reach a 100Χ substock. The 100Χ substock was subsequently diluted 20-fold in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (w/v) glycerol containing TAXIPm-P and a potential ligand to reach a final Sypro Orange concentration of 5Χ. Samples were subjected to thermal melting in an RT-PCR cycler (Rotor-Gene Q, Qiagen). Protein was incubated from 25 °C up to 95 °C in steps of 1 °C with 1 min per incubation step, and Sypro Orange fluorescence was recorded (excitation: 470 nm, emission: 555 nm).

4.6 Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

IMAC-purified soluble TAXIPm-P was thawed, subjected to SEC in 50 mM KPi, pH 5.5, 6.0, or 7.5, and peak fractions were concentrated to 30 µM, degassed, pre-warmed to 18 °C, and transferred to the reaction cells of the ITC device (MicroCal VP-ITC, Malvern). The ligand was dissolved in the same buffer as the respective protein preparation, adjusted to 600 µM and filled in the syringe of the ITC device. Once the reaction cell reached 20 °C, the ligand was titrated to the protein solution in 10 µL steps, resulting in a gradual increase of the ligand concentration from 6.4 µM to 95.5 µM. Data was evaluated using the software NITPIC for automatic baseline correction and subtraction of dilution heat, the software Sedphat to set the binding parameters to heteroassociation assuming a 1:1 binding stoichiometry and fitting the data, and the software GUSSI for plotting the data (Brautigam et al. 2016).

4.7 Radiolabeled transport assay on whole cells

Radioactive transport assays of α-ketoglutarate by TAXIPm-PQM were performed using E. coli BW25113 (ΔkgtP) transformed with pEXC3sfGH containing a sequence coding for TAXIPm-PQM in which the first twenty amino acids of TAXIPm-P were replaced with the first 21 amino acids of SiaP from H. influenzae (Supplementary Figure 4). Cells were grown overnight in LB medium, supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin. The next day, 10 mL LB/amp were inoculated with 1% of the pre-culture. The cells were grown in tubes with a gas-permeable lid at 37 °C until an OD600 of 0.6–0.8 was reached, followed by induction with 1 mM IPTG for 2 h at 37 °C. All subsequent steps were performed at 4 °C. Cells were harvested for 10 min at 2500 g, washed twice using 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, and adjusted to an OD600 of 100. The transport assay was performed at 30 °C in 50 mM KPi, pH 6.0 or 7.5, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1% (w/v) glucose. If needed, 10 µM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) was added to dissipate the proton-gradient. Following thermal equilibration of the buffer for 1 min, cells were added to a final OD of 3 and pre-energized for 2 min. Samples were continuously stirred. The transport reaction was started by the addition of 2 µM [14C]-α-ketoglutarate and stopped at dedicated timepoints by transferring 100 µL into 2 mL ice-cold 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, and immediate filtrated over an 0.45 µm pore size nitrocellulose acetate filter. Subsequently, the filters were washed with another 2 mL ice-cold buffer and dissolved in 4 mL scintillation liquid overnight. The next day, the radioactivity was determined using a scintillation counter. TAXIPm-QM expression levels and folding quality were determined based on the C-terminal GFP-fusion as described (Marino et al. 2017).

4.8 Radiolabeled transport assay on proteoliposomes

Transport assays on TAXIPm-PQM proteoliposomes were performed at 20 °C in 50 mM KPi, pH 6.0, or 50 mM NaPi, pH 6.0, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4 and 10 µM [14C]-α-ketoglutarate. A 25 µL aliquot of proteoliposomes in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, at a lipid concentration of 100 mg/mL and a TAXIPm-QM concentration of 2 mg/mL were diluted in 575 µL of the respective outside buffer to a final TAXIPm-QM concentration of 83 μg/mL. Samples were continuously stirred. At dedicated timepoints the transport reaction was stopped by transferring 100 µL into 2 mL ice-cold 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5, supplemented with 2 mM MgSO4, and immediate filtrated over an 0.45 µm pore size nitrocellulose acetate filter. Subsequently, the filters were washed with another 2 mL ice-cold buffer and dissolved in 4 mL scintillation liquid overnight. The next day, the radioactivity was determined using a scintillation counter.

Funding source: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

Award Identifier / Grant number: Cluster of Excellence Frankfurt – Macromolecular Complexes (EXC115)

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Prof. Dr. Volker Dötsch, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main for access to ITC equipment, Dr. Christian Osterburg for initial ITC training, and Drs. Dorothea Anrather and Markus Hartl of the Mass Spectrometry Facility from the Max Perutz Labs Support in Vienna, Austria for intact protein mass analysis. AR thanks the KNAUER Wissenschaftliche Geräte GmbH, Berlin for the great support that permitted the experiments to be realized. We further acknowledge Christiane Ruse for assistance with cloning and sample preparation, and Drs. Barbara Borgonovo (PEPC-facility, MPI-CBG) and Benedikt Kuhn for critical discussions. This research was financially supported by the German Research Foundation via the Cluster of Excellence Frankfurt – Macromolecular Complexes, and core funding from MPI-CBG (ERG). All members of the Geertsma and Pos laboratories are acknowledged for help in all stages of the project.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (EXC115); MPI-CBG (core-funding)

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Albers, S.V., Elferink, M.G., Charlebois, R.L., Sensen, C.W., Driessen, A.J., and Konings, W.N. (1999). Glucose transport in the extremely thermoacidophilic Sulfolobus solfataricus involves a high-affinity membrane-integrated binding protein. J. Bacteriol. 181: 4285–4291, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.181.14.4285-4291.1999.Search in Google Scholar

Bergeron, M.J., Clemencon, B., Hediger, M.A., and Markovich, D. (2013). SLC13 family of Na+-coupled di-and tri-carboxylate/sulfate transporters. Mol. Aspect. Med. 34: 299–312, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2012.12.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Bosdriesz, E., Magnusdottir, S., Bruggeman, F.J., Teusink, B., and Molenaar, D. (2015). Binding proteins enhance specific uptake rate by increasing the substrate-transporter encounter rate. FEBS J. 282: 2394–2407, https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.13289.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Brautigam, C.A., Deka, R.K., Schuck, P., Tomchick, D.R., and Norgard, M.V. (2012). Structural and thermodynamic characterization of the interaction between two periplasmic Treponema pallidum lipoproteins that are components of a TPR-protein-associated TRAP transporter (TPAT). J. Mol. Biol. 420: 70–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2012.04.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Brautigam, C.A., Zhao, H., Vargas, C., Keller, S., and Schuck, P. (2016). Integration and global analysis of isothermal titration calorimetry data for studying macromolecular interactions. Nat. Protoc. 11: 882–894, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2016.044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Chang, Y.N., Jaumann, E.A., Reichel, K., Hartmann, J., Oliver, D., Hummer, G., Joseph, B., and Geertsma, E.R. (2019). Structural basis for functional interactions in dimers of SLC26 transporters. Nat. Commun. 10: 2032, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10001-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Davidson, A.L. and Maloney, P.C. (2007). ABC transporters: how small machines do a big job. Trends Microbiol. 15: 448–455, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2007.09.005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Davies, J.S., Currie, M.J., North, R.A., Scalise, M., Wright, J.D., Copping, J.M., Remus, D.M., Gulati, A., Morado, D.R., Jamieson, S.A., et al.. (2023). Structure and mechanism of the tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporter. Nat. Commun. 14: 1120, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.13.480285.Search in Google Scholar

Deka, R.K., Brautigam, C.A., Goldberg, M., Schuck, P., Tomchick, D.R., and Norgard, M.V. (2012). Structural, bioinformatic, and in vivo analyses of two Treponema pallidum lipoproteins reveal a unique TRAP transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 416: 678–696, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Drew, D. and Boudker, O. (2016). Shared molecular mechanisms of membrane transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 85: 543–572, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014520.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Forward, J.A., Behrendt, M.C., Wyborn, N.R., Cross, R., and Kelly, D.J. (1997). TRAP transporters: a new family of periplasmic solute transport systems encoded by the dctPQM genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus and by homologs in diverse Gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 179: 5482–5493, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.179.17.5482-5493.1997.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Gautom, T., Dheeman, D., Levy, C., Butterfield, T., Alvarez Gonzalez, G., Le Roy, P., Caiger, L., Fisher, K., Johannissen, L., and Dixon, N. (2021). Structural basis of terephthalate recognition by solute binding protein TphC. Nat. Commun. 12: 6244, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26508-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Geertsma, E.R. and Dutzler, R. (2011). A versatile and efficient high-throughput cloning tool for structural biology. Biochemistry 50: 3272–3278, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi200178z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Geertsma, E.R., Nik Mahmood, N.A., Schuurman-Wolters, G.K., and Poolman, B. (2008). Membrane reconstitution of ABC transporters and assays of translocator function. Nat. Protoc. 3: 256–266, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.519.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hall, J.A. and Pajor, A.M. (2007). Functional reconstitution of SdcS, a Na+-coupled dicarboxylate carrier protein from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 189: 880–885, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.01452-06.Search in Google Scholar

Hamilton, M.D., Nuara, A.A., Gammon, D.B., Buller, R.M., and Evans, D.H. (2007). Duplex strand joining reactions catalyzed by vaccinia virus DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: 143–151, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl1015.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Holzhuter, K. and Geertsma, E.R. (2020). Functional (un)cooperativity in elevator transport proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 48: 1047–1055, https://doi.org/10.1042/bst20190970.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Holzhuter, K. and Geertsma, E.R. (2022). Uniport, not proton-symport, in a non-mammalian SLC23 transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 434: 167393, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167393.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Jacobs, M.H., van der Heide, T., Driessen, A.J., and Konings, W.N. (1996). Glutamate transport in Rhodobacter sphaeroides is mediated by a novel binding protein-dependent secondary transport system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93: 12786–12790, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.23.12786.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kalliri, E., Mulrooney, S.B., and Hausinger, R.P. (2008). Identification of Escherichia coli YgaF as an L-2-hydroxyglutarate oxidase. J. Bacteriol. 190: 3793–3798, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.01977-07.Search in Google Scholar

Kelly, D.J. and Thomas, G.H. (2001). The tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters of bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25: 405–424, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00584.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lewinson, O. and Livnat-Levanon, N. (2017). Mechanism of action of ABC importers: conservation, divergence, and physiological adaptations. J. Mol. Biol. 429: 606–619, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2017.01.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mancusso, R., Gregorio, G.G., Liu, Q., and Wang, D.N. (2012). Structure and mechanism of a bacterial sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter. Nature 491: 622–626, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11542.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Marino, J., Holzhuter, K., Kuhn, B., and Geertsma, E.R. (2017). Efficient screening and optimization of membrane protein production in Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 594: 139–164, https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2017.05.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Müller, A., Severi, E., Mulligan, C., Watts, A.G., Kelly, D.J., Wilson, K.S., Wilkinson, A.J., and Thomas, G.H. (2006). Conservation of structure and mechanism in primary and secondary transporters exemplified by SiaP, a sialic acid binding virulence factor from Haemophilus influenzae. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 22212–22222, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m603463200.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mulligan, C., Fischer, M., and Thomas, G.H. (2011). Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters in bacteria and archaea. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35: 68–86, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00236.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mulligan, C., Fitzgerald, G.A., Wang, D.N., and Mindell, J.A. (2014). Functional characterization of a Na+-dependent dicarboxylate transporter from Vibrio cholerae. J. Gen. Physiol. 143: 745–759, https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.201311141.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mulligan, C., Geertsma, E.R., Severi, E., Kelly, D.J., Poolman, B., and Thomas, G.H. (2009). The substrate-binding protein imposes directionality on an electrochemical sodium gradient-driven TRAP transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 1778–1783, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0809979106.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Mulligan, C., Kelly, D.J., and Thomas, G.H. (2007). Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic transporters: application of a relational database for genome-wide analysis of transporter gene frequency and organization. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12: 218–226, https://doi.org/10.1159/000099643.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Mulligan, C., Leech, A.P., Kelly, D.J., and Thomas, G.H. (2012). The membrane proteins SiaQ and SiaM form an essential stoichiometric complex in the sialic acid tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporter SiaPQM (VC1777-1779) from Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 3598–3608, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m111.281030.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ovchinnikov, S., Kamisetty, H., and Baker, D. (2014). Robust and accurate prediction of residue-residue interactions across protein interfaces using evolutionary information. Elife 3: e02030, https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.02030.Search in Google Scholar

Pajor, A.M., Sun, N.N., and Leung, A. (2013). Functional characterization of SdcF from Bacillus licheniformis, a homolog of the SLC13 Na+/dicarboxylate transporters. J. Membr. Biol. 246: 705–715, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00232-013-9590-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Pearson, M.M., Yep, A., Smith, S.N., and Mobley, H.L. (2011). Transcriptome of Proteus mirabilis in the murine urinary tract: virulence and nitrogen assimilation gene expression. Infect. Immun. 79: 2619–2631, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.05152-11.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Peter, M.F., Ruland, J.A., Depping, P., Schneberger, N., Severi, E., Moecking, J., Gatterdam, K., Tindall, S., Durand, A., Heinz, V., et al.. (2022). Structural and mechanistic analysis of a tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic TRAP transporter. Nat. Commun. 13: 4471, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31907-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Price, M.N., Huang, K.H., Alm, E.J., and Arkin, A.P. (2005). A novel method for accurate operon predictions in all sequenced prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 880–892, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki232.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rosa, L.T., Bianconi, M.E., Thomas, G.H., and Kelly, D.J. (2018). Tripartite ATP-independent periplasmic (TRAP) transporters and tripartite tricarboxylate transporters (TTT): from uptake to pathogenicity. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8: 33, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Schaffer, J.N. and Pearson, M.M. (2015). Proteus mirabilis and urinary tract infections. Microbiol. Spectr. 3: 3.5.10, https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.uti-0017-2013.Search in Google Scholar

Scheepers, G.H., Lycklama, A.N.J.A., and Poolman, B. (2016). An updated structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 590: 4393–4401, https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.12445.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Seol, W. and Shatkin, A.J. (1992). Escherichia coli α-ketoglutarate permease is a constitutively expressed proton symporter. J. Biol. Chem. 267: 6409–6413, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(18)42710-x.Search in Google Scholar

Shuman, H.A. (1982). Active transport of maltose in Escherichia coli K12. Role of the periplasmic maltose-binding protein and evidence for a substrate recognition site in the cytoplasmic membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 257: 5455–5461, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9258(19)83799-7.Search in Google Scholar

Strickler, M.A., Hall, J.A., Gaiko, O., and Pajor, A.M. (2009). Functional characterization of a Na+-coupled dicarboxylate transporter from Bacillus licheniformis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788: 2489–2496, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.10.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sutcliffe, I.C. and Russell, R.R. (1995). Lipoproteins of Gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 177: 1123–1128, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.177.5.1123-1128.1995.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Takahashi, H., Inagaki, E., Kuroishi, C., and Tahirov, T.H. (2004). Structure of the Thermus thermophilus putative periplasmic glutamate/glutamine-binding protein. Acta Crystallogr., D: Biol. Crystallogr. 60: 1846–1854, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0907444904019420.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Teufel, F., Almagro Armenteros, J.J., Johansen, A.R., Gislason, M.H., Pihl, S.I., Tsirigos, K.D., Winther, O., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G., and Nielsen, H. (2022). SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 40: 1023–1025, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-01156-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

van der Heide, T. and Poolman, B. (2002). ABC transporters: one, two or four extracytoplasmic substrate-binding sites? EMBO Rep. 3: 938–943, https://doi.org/10.1093/embo-reports/kvf201.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Vetting, M.W., Al-Obaidi, N., Zhao, S., San Francisco, B., Kim, J., Wichelecki, D.J., Bouvier, J.T., Solbiati, J.O., Vu, H., Zhang, X., et al.. (2015). Experimental strategies for functional annotation and metabolism discovery: targeted screening of solute binding proteins and unbiased panning of metabolomes. Biochemistry 54: 909–931, https://doi.org/10.1021/bi501388y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Winnen, B., Hvorup, R.N., and Saier, M.H.Jr (2003). The tripartite tricarboxylate transporter (TTT) family. Res. Microbiol. 154: 457–465, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0923-2508(03)00126-8.Search in Google Scholar

Youn, J.W., Jolkver, E., Kramer, R., Marin, K., and Wendisch, V.F. (2008). Identification and characterization of the dicarboxylate uptake system DccT in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 190: 6458–6466, https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.00780-08.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2022-0337).

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Membrane Proteins from Structure to Function

- The Rauischholzhausen Transport Colloquium: membrane proteins from structure to function

- Determination of membrane protein orientation upon liposomal reconstitution down to the single vesicle level

- Interaction of RTX toxins with the host cell plasma membrane

- Interactions of Na+/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide with host cellular proteins upon hepatitis B and D virus infection: novel potential targets for antiviral therapy

- Mycobacterial type VII secretion systems

- Lipid exchange among electroneutral Sulfo-DIBMA nanodiscs is independent of ion concentration

- Membrane-anchored substrate binding proteins are deployed in secondary TAXI transporters

- ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis in full-length MsbA monitored via time-resolved Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Membrane Proteins from Structure to Function

- The Rauischholzhausen Transport Colloquium: membrane proteins from structure to function

- Determination of membrane protein orientation upon liposomal reconstitution down to the single vesicle level

- Interaction of RTX toxins with the host cell plasma membrane

- Interactions of Na+/taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide with host cellular proteins upon hepatitis B and D virus infection: novel potential targets for antiviral therapy

- Mycobacterial type VII secretion systems

- Lipid exchange among electroneutral Sulfo-DIBMA nanodiscs is independent of ion concentration

- Membrane-anchored substrate binding proteins are deployed in secondary TAXI transporters

- ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis in full-length MsbA monitored via time-resolved Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy