Abstract

We describe the structural analysis of two Anticalin® proteins that tightly bind Aβ40, a peptide involved in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease. These anticalins, US7 and H1GA, were engineered on the basis of the human lipocalin 2, thus yielding compact single-domain binding proteins as an alternative to antibodies. Albeit selected under different conditions and mutually deviating in 13 amino acid positions within the binding pocket (of 17 mutated residues in total), both crystallised anticalins recognize the same epitope in the middle of the β-amyloid peptide. In the two complexes with the Aβ40 peptide, its central part comprising residues LysP16 to LysP28 shows well defined electron density whereas the flanking regions appear structurally disordered. The compact zigzag-bend conformation which is seen in both structures may indicate a role during conversion of the soluble monomeric form into pathogenic Aβ state(s) and, thus, explain the aggregation-inhibiting effect of the anticalins. In contrast to solanezumab, which targets the same Aβ region in a different conformation, the anticalin H1GA does not show cross-reactivity with sequence-related human plasma proteins. Consequently, anticalins offer promising reagents to prevent oligomerization of Aβ peptides to neurotoxic species in vivo and their small size may enable new routes for brain delivery.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent form of dementia, with 10% of the human population older than 65 and even 40% older than 85 years affected (Morgan 2011). Apart from a few forms of inherited AD (Tanzi and Bertram 2005), age is the major risk factor for this slowly progressive but devastating neurodegenerative disease, thus causing a dramatic increase of AD incidence due to the steadily aging global population. A histopathological hallmark of AD is the formation of so-called senile amyloid plaques (amyloid-β, Aβ). These arise from the extracellular accumulation of fibrils comprising self-aggregating Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides as result of the abnormal processing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) via β- and γ-secretases (DeTure and Dickson 2019).

According to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, depletion of Aβ should alleviate or even abolish AD, which has prompted efforts since more than 20 years to develop therapies with the goal to lower Aβ production, prevent Aβ aggregation and/or dissolve Aβ deposits (Decourt et al. 2021). In particular, immunotherapies involving monoclonal antibodies (mAb) that target Aβ plaques, including the prominent examples aducanumab, lecanemab, solanezumab, crenezumab and gantenerumab, have raised expectations which, however, were compromised by a general lack of definitive preventative or curative properties in advanced clinical trials (Decourt et al. 2021). Nevertheless, though not without controversy, the recent approval of the mAb aducanumab, which binds the residues 3–7 at the N-terminus of Aβ and selectively targets its pathological oligomeric and fibrillar forms (Arndt et al. 2018), by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has flagged the first new drug for AD treatment since 15 years (Selkoe 2021).

While amyloid plaques are clearly associated with advanced stages of the disease, recent evidence emerging from mouse models of AD suggests that soluble (misfolded) lower oligomeric forms of Aβ – which subsequently convert into larger polymers and insoluble β-sheet fibrils – already evoke neuronal hyperactivity, presumably mediated by suppression of glutamate reuptake, eventually leading to the primary neuronal dysfunction (Busche et al. 2012; Zott et al. 2019). The role of such an early neuropathological mechanism, prior to the macroscopic plaque formation, is in line with the discouraging findings from clinical studies so far as mentioned above. This notion lends support to the search for mAbs or alternative binding proteins which specifically scavenge and neutralize Aβ peptides in their nascent soluble monomeric state, thus preventing toxicities not only at the fibrillar stage but also for any early oligomeric Aβ species at the onset of the amyloid cascade.

We have recently described the selection of three different anticalin proteins, dubbed H1GA, S1A4 and US7, against the Aβ40 peptide (applied as targets for selection in different molecular formats) using combinatorial protein design starting from a random library of human lipocalin 2 (Lcn2) (Rauth et al. 2016). Lipocalins are a family of compact robust secretory proteins whose fold is dominated by a central eight-stranded β-barrel, which carries four structurally variable loops at the open end where ligands can be bound in a dedicated pocket. By reshaping this loop region, artificial binding proteins with prescribed target specificities and high affinities, so-called anticalin proteins, can be readily obtained (Richter et al. 2014). In fact, a series of biopharmaceutical drug candidates directed against various disease-related molecular targets are currently subject to clinical trials (Deuschle et al. 2021; Rothe and Skerra 2018). Lcn2, also known as neutrophil-gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL) or as siderocalin, constitutes an abundant human plasma protein and has been successfully employed as a scaffold for anticalin generation in many cases (Achatz et al. 2022; Gebauer et al. 2013; Richter et al. 2014).

While full size mAbs continue to dominate drug development efforts in the area of AD (Decourt et al. 2021), the small size of anticalins as alternative Aβ-binding reagents offers benefits in view of two promising therapeutic strategies: (i) to scavenge, after systemic delivery, soluble Aβ peptides distributed from the central nervous system (CNS) into the blood plasma, followed by rapid elimination via the kidneys, according to the peripheral sink hypothesis (DeMattos et al. 2001); (ii) to construct fusion proteins with protein/peptide ligands of transcytose receptors that enable efficient passage across the blood-brain barrier (BBB) via the Trojan horse strategy, thus effecting neutralization of Aβ peptides within the neuronal tissue from which they originate (Selkoe 2021). In this context, the lack of immunological effector functions for conventional anticalins (Deuschle et al. 2021) should fully prevent the key adverse effect of anti-Aβ mAbs, such as focal cerebral edema as well as microhemorrhages (Selkoe 2021). Of note, a clinical-stage anticalin that effectively scavenges a disease-related peptide has been described before (Renders et al. 2019). This biological drug candidate targets and antagonises hepcidin and shows promise to promote iron uptake, availability and erythropoiesis, for example in chronic kidney disease.

The three selected anti-Aβ anticalins all show tight binding of the peptide target, with KD values in the low nanomolar down to the picomolar range. In this regard H1GA, which resulted from rational affinity maturation (Rauth et al. 2016), is remarkable due to its KD value of 95 pM and an extraordinary half-life of τ1/2 = 16 h (at ambient temperature) for the dissociation of its complex with the Aβ40 peptide. Unexpectedly, and in spite of originating from phage display selection with different Aβ target formats, all three anticalins recognize a common linear epitope comprising the amino acid sequence (V)FFAED (residues P19–P23). This epitope is located at the center of both pathogenic Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides and also coincides with a hot spot for specific mutations that are associated with rare hereditary forms of AD (Bateman et al. 2011). Importantly, the anti-Aβ anticalins demonstrated inhibitory activity towards Aβ40 aggregation in vitro, which was most pronounced for H1GA, as well as a protective effect against aged Aβ42 in neuronal cell culture (Rauth et al. 2016).

To understand the mechanisms of molecular recognition of Aβ peptides by the anticalins and to gain insight into their potential as biopharmaceutical drug candidates of a novel class, we have performed crystallographic analyses of the anticalin proteins H1GA and US7 in complex with the minimal epitope peptide as well as with the full length Aβ40 target.

Results and discussion

Crystallographic analysis of engineered lipocalins in complex with Aβ40 and the minimal epitope peptide

Initially, the anticalin US7 was co-crystallized with the synthetic hexapeptide Ac-VFFAED-NH2, which represents the central Aβ epitope as identified in a SPOT epitope screen (Rauth et al. 2016). Subsequently, US7 was also crystallized isomorphously in 1:1 complex with the synthetic full length Aβ40 peptide. The two crystal structures, each with one protein•peptide complex in the asymmetric unit (a.u.), were solved at resolutions of 1.7 and 1.5 Å, respectively, using a synchroton X-ray source (Table 1). Finally, we also obtained crystals of the anticalin H1GA in complex with the full length Aβ40 peptide at 2.3 Å resolution, this time showing a different morphology with four protein•peptide complexes in the a.u.

Crystallographic analysis and refinement statistics.

| Protein: | US7 | US7 | H1GA |

| Ligand: | Aβ 40 | VFFAED | Aβ 40 |

| PDB ID: | 4MVI | 4MVK | 4MVL |

| Crystal data: | |||

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell dimensions a, b, c [Å], α = β = γ = 90° |

49.0, 58.9, 61.2 | 51.0, 59.2, 61.2 | 79.3, 79.2, 142.6 |

| Molecules per a.u. | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Data collection: | |||

| Wavelength [Å] | 0.91841 | 0.91841 | 0.91841 |

| Resolution range [Å]a | 30.0–1.7 (1.79–1.70) |

27.0–1.5 (1.58–1.50) |

39.7–2.3 (2.42–2.30) |

| I/σ[I]a | 7.6 (3.1) | 5.5 (2.0) | 5.9 (3.4) |

| Rmerge [%]a, b | 5.5 (24.5) | 7.8 (34.8) | 8.8 (22.4) |

| Unique reflections | 20,073 | 30,318 | 39,966 |

| Multiplicitya | 6.9 (6.9) | 7.1 (7.0) | 5.9 (5.5) |

| Completenessa | 99.9 (99.9) | 99.8 (100.0) | 98.4 (95.3) |

| Refinement: | |||

| Rcryst/Rfreeb | 16.9/21.2 | 16.5/18.6 | 21.9/27.9 |

| Protein atoms | 1394 | 1386 | 5560 |

| Peptide atoms | 102 | 55 | 304 |

| Solvent atoms | 81 | 160 | 129 |

| Average B-factor [Å2] | |||

| Protein | 28.6 | 23.9 | 26.4 |

| Peptide | 34.7 | 15.3 | 24.9 |

| Water | 29.4 | 31.7 | 17.6 |

| Geometry: | |||

| R.m.s.d. bond lengths, angles [Å, °] | 0.020, 1.960 | 0.023, 2.104 | 0.006, 1.024 |

| Ramachandran analysisc: | |||

Core, allowed, generously allowed, disallowed [%] |

85.4, 12.7, 0.6, 1.3 | 86.8, 9.3, 2.6, 1.3 | 82.6, 13.3, 1.3, 2.7 |

-

aValues in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell. bRmerge, Rcryst and Rfree according to Arndt et al. (1968), Brunger (1997) and Wilson (1950). cCalculated with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993).

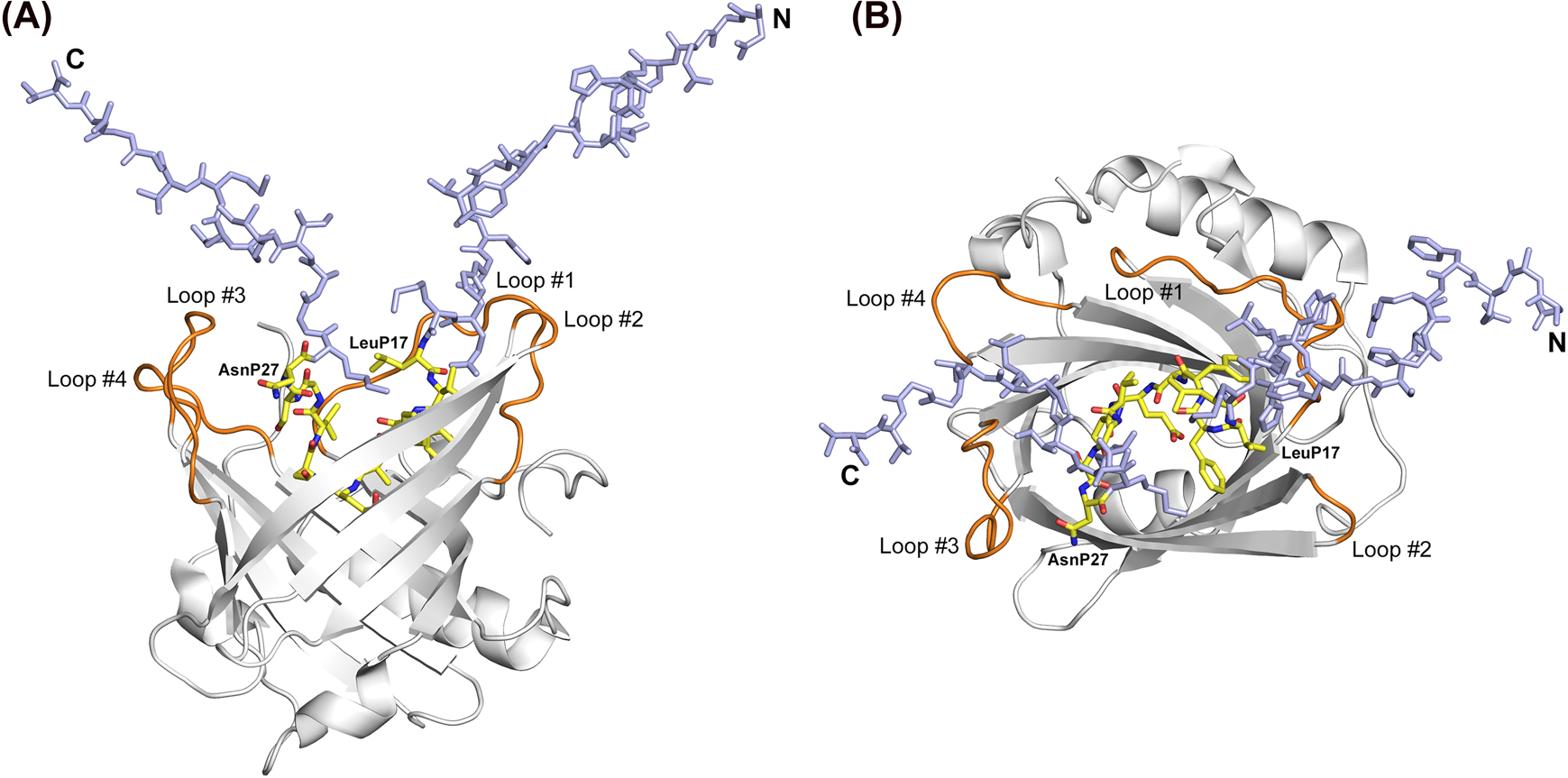

In all these crystal structures the anticalins US7 and H1GA (Figure 1) revealed the canonical lipocalin fold (Schiefner and Skerra 2015; Skerra 2000), as expected, comprising an eight-stranded β-barrel with an adjacent α-helix (Figures 2 and 3). Despite the considerable number of 17 mutated amino acids (plus two fixed mutations) that were distributed across the four structurally variable loops of the Lcn2 scaffold (PDB ID: 1L6M) (Achatz et al. 2022; Goetz et al. 2002) both anticalins showed a high degree of three-dimensional conservation, revealing root mean square deviations (RMSD) versus Lcn2 of 0.44 Å for US7•Aβ40 (0.45 Å for US7•VFFAED) and of 0.42 Å (chain A) for H1GA•Aβ40 upon superposition via a set of 58 conserved Cα positions within the β-barrel (Skerra 2000).

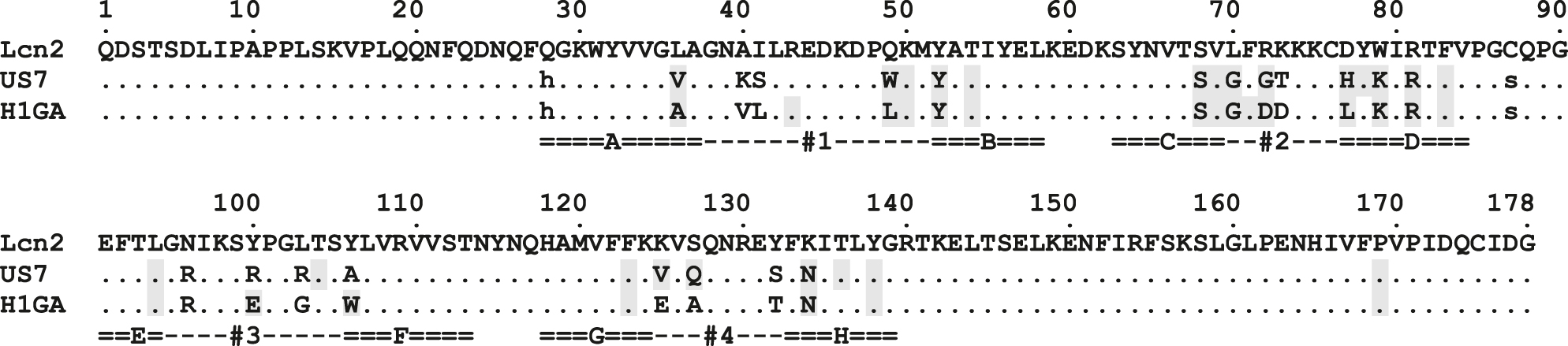

Amino acid sequence alignment of wtLcn2 with the Anticalins US7 and H1GA.

Residues that contact the Aβ40-peptide in the crystal structures (see Table 2) are highlighted using a gray background.

Crystal structure of an anticalin in complex with the Aβ40 peptide.

(A) H1GA•Aβ40 side view (loops orange, peptide carbon atoms yellow); the disordered N- and C-termini (P1–P16 and P28–P40) of Aβ40 are colored light blue. (B) View into the binding site of the H1GA•Aβ40 complex, rotated by 90° around a horizontal axis. The first and last residues of the visible part of the Aβ40 peptide are labelled.

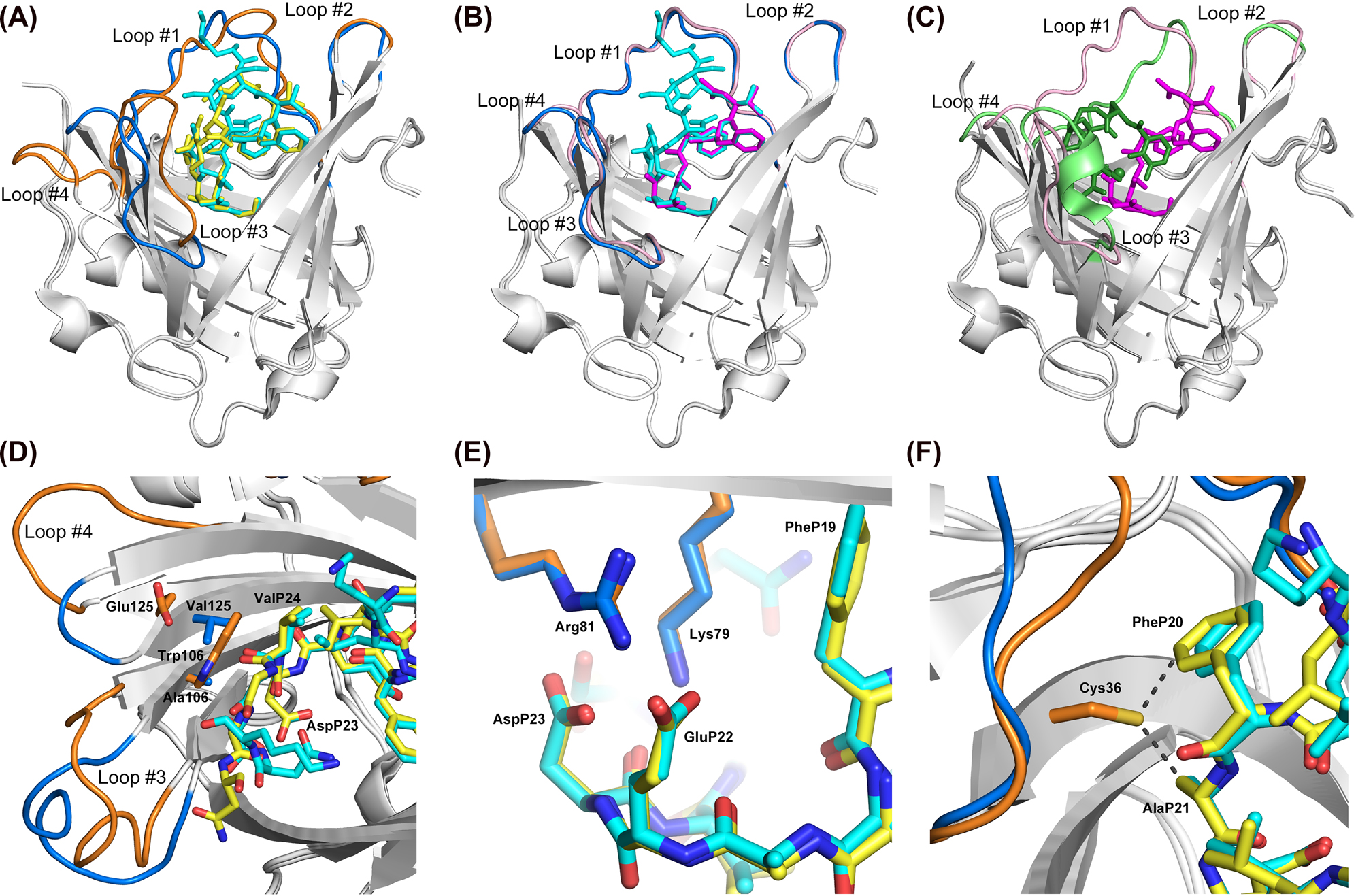

Structural comparison of the two anticalins selected against Aβ40 with wtLcn2.

(A) Superposition of H1GA•Aβ40 (loops orange, peptide yellow) with US7•Aβ40 (loops blue, peptide cyan). The central part of the Aβ40 peptide, including the Phe/Phe moiety, shows high overlap, whereas the flanking parts exhibit deviations. Loops #1, #3 and #4 reveal significant conformational changes as discussed in the text. (B) Superposition of US7•Aβ40 (loops blue, peptide cyan) with US7•VFFAED (loops pink, peptide magenta). The minimal epitope peptide structurally coincides with the central moiety of the Aβ40 peptide in the two different complexes while the loops of the anticalin show high structural similarity. (C) Superposition of US7•VFFAED (loops pink, peptide magenta) with wtLcn2 in complex with its natural ligand, FeIII•enterobactin (loops green, ligand forest; PDB ID: 3CMP). The VFFAED peptide in the complex with the anticalin only partially occupies the cavity where the natural ligand of wtLcn2 is bound. Loops #1, #3 and #4 of the anticalin US7 deviate to a similar extent from the wtLcn2 structure as from the anticalin H1GA (see panel (A)). (D) Distinct interactions between the pair of side chains Trp106/Glu125 in H1GA versus Ala106/Val125 in US7 and the central residues AspP23/ValP24 in the bound Aβ peptide. (E) Interaction between the conserved pair of positively charged residues, Lys79 and Arg81, in both anticalins and the two anionic side chains at the center of the bound Aβ peptide, GluP22 and AspP23. (F) The side chain of Cys36 in the original anticalin version H1G1 modelled in the crystal structure of H1GA with its most plausible rotamer, revealing close contacts (∼3 Å) to PheP20 and AlaP21.

Compared with the wild type Lcn2, the loop conformations in the anticalins differ to varying degrees. Loop #2 in the US7•Aβ40 complex as well as loop #4 in the H1GA•Aβ40 complex show virtually identical backbone structure. The conformations of the longer loops #1 and #3, on the other hand, exhibit deviations up to 7.8 Å (position 43 in loop #1 of H1GA•Aβ40) and 6.8 Å (position 99 in loop #3 of US7•Aβ40). While, generally, the side chains both of the conserved and the mutated residues in the anticalins show similar orientations as in wtLcn2, position 41 reveals a notable exception: the side chain of the Ile residue in wtLcn2 points into the ligand pocket whereas the mutated side chains of Ser in US7•Aβ40 and of Leu in H1GA•Aβ40 are oriented outward.

The resulting reshaped ligand pocket of the anticalin US7, for example, is moulded by two pairs of opposing loops, with loops #1 and #2 on one side and loops #3 and #4 on the other (Figure 2), and has roughly rectangular dimensions of 22 Å by 23 Å. Due to the bulky side chains of residues Tyr52 and Lys79 and of Lys40 and Gln127 on both sides of the cleft, the binding site of US7 is rather slim if compared with the one of the natural Lcn2 for its ligand enterobactin, a siderophore complexing FeIII (Goetz et al. 2002), and appears ideally shaped to accommodate the linear Aβ peptide ligand.

In the crystallized complex of US7 with the full length Aβ40 peptide, a stretch of 13 peptide residues in its central region, P16–P28 (KLVFFAEDVGSNK, minimal epitope underlined), is well defined in the electron density whereas the N- and C-terminal peptide segments are disordered. Compared with the structure of the complex between US7 and the shorter peptide VFFAED the diffraction quality was only slightly inferior (cf. Table 1). In line with the isomorphous crystallization, the conformations of both the anticalin and the bound epitope peptide are highly similar in the US7•Aβ40 complex, with an RMSD of merely 0.099 Å for the 58 conserved Cα positions and of 0.373 Å for all 177 common Cα atoms of the protein and peptide chains. In particular, the conformations of the structurally variable loops are virtually identical in both structures; the largest deviation occurs in loop #3 with 2.1 Å at residue Lys98 and in loop #1 with 1.8 Å at Lys40.

Interestingly, the visible Aβ peptide segment is compactly folded in three to four turns (see below). Its conformation is stabilized by several intramolecular hydrogen bonds, including a hydrogen bond network with 5 water molecules that appear well defined in the electron density (Figure 4). This peptide stretch wriggles deeply into the cavity of the engineered lipocalin, which in this manner gets almost completely filled. Nine peptide residues (VFFAEDVGS) are fully buried within the ligand pocket. The tight interaction with the anticalin is dominated by a multitude of hydrogen bonds, salt bridges and intimate hydrophobic interactions (Table 2).

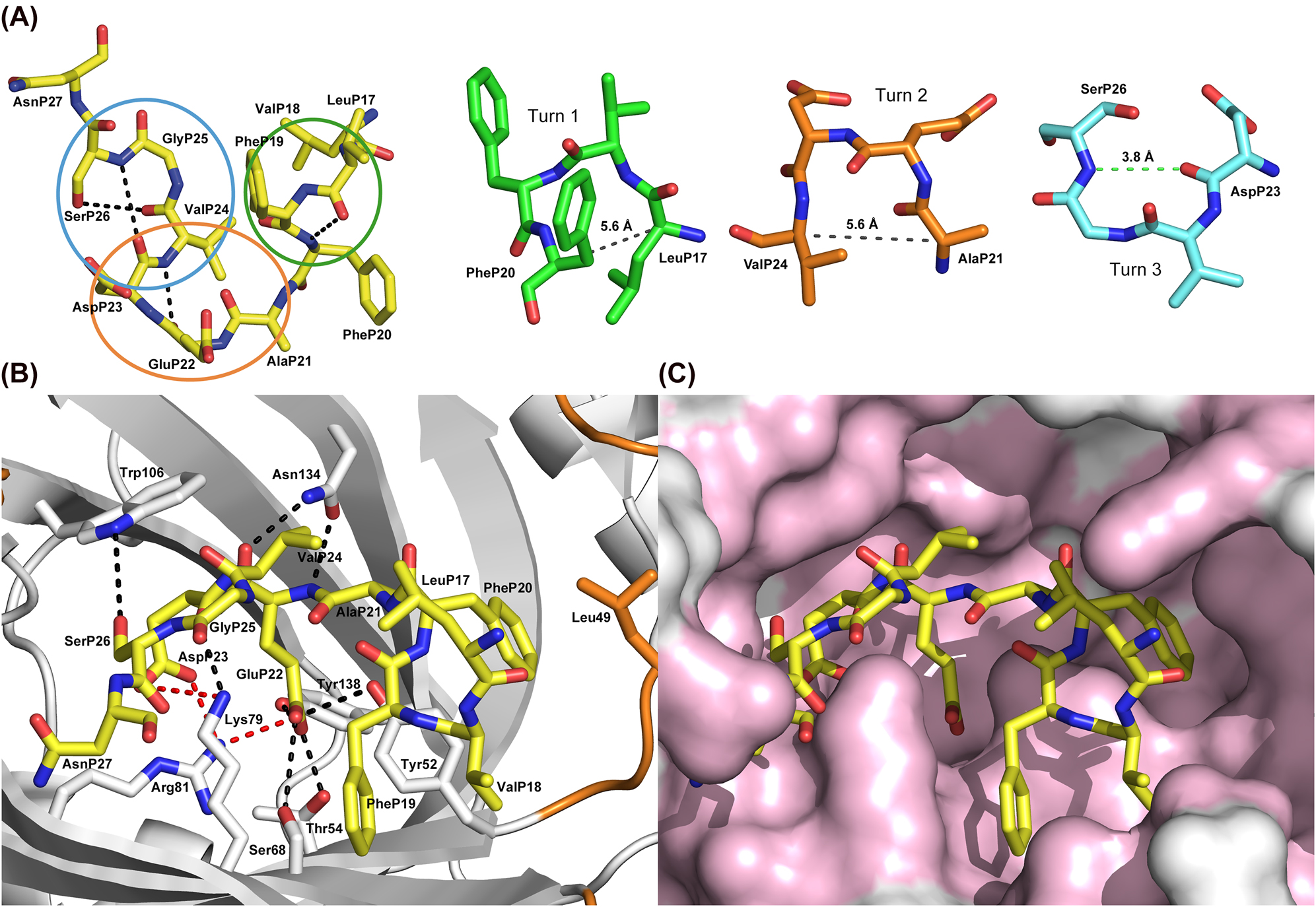

Conformation of the Aβ40 peptide and its detailed interactions with the anticalin H1GA.

(A) Aβ40 peptide conformation in the anticalin complex with intramolecular hydrogen bonds shown as black dashed lines (carbon atoms yellow). The three turns formed by the central segment of the Aβ peptide are marked by ellipses in different colors and displayed individually to the right. The hydrogen bond between the main chain C=O(i) and N-H(i + 3) of turn 3 is highlighted by a green dashed line whereas the corresponding Cα/Cα distances in the other two turns are indicated by gray dashed lines. (B) Aβ40 bound to H1GA (top view). Protein residues that form hydrogen bonds (black dashed lines) or salt bridges (red dashed lines) with the peptide ligand are depicted as sticks. (C) Surface representation of the binding site of H1GA with the bound Aβ40 peptide, whose hydrophobic side chains occupy different subpockets, in the same orientation as shown in panel (B). Protein residues that form contacts to Aβ40 are colored light pink (for residue labelling see panel (B)).

Residues of the anticalins US7 and H1GA that interact with the Aβ40 peptide.

| US7 residue | Interaction | BSA [Å2] | Aβ residue | BSA [Å2] | Interaction | H1GA residue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 5.4 | LysP16 | – | |||

| None | 0.7 | LeuP17 | 46.3 | VDW | Arg43* | |

| Tyr52* Gly70* Gly72 |

VDW VDW VDW |

83.3 | ValP18 | 100.0 | VDW VDW VDW VDW |

Tyr52* Phe71* Asp72 Leu77 |

| Tyr52* Ser68* Val69* Gly70* His77 Tyr78* Lys79* |

VDW VDW VDW VDW VDW VDW VDW |

124.0 | PheP19 | 139.9 | VDW VDW VDW VDW VDW |

Tyr52* Ser68* Val69* Gly70* Leu77 |

| Val36 Trp49 Lys50* Tyr52* Pro169* |

VDW VDW VDW HB VDW |

138.6 | PheP20 | 132.5 | VDW VDW VDW VDW VDW |

Ala36 Leu49 Lys50* Tyr52* Pro169* |

| Val36 Tyr52* Thr136* |

VDW HB VDW |

52.9 | AlaP21 | 52.4 | VDW HB VDW |

Ala36 Tyr52* Asn134* |

| Tyr52* Thr54* Ser68* Arg81* Phe123* Val125 Asn134* Thr136* Tyr138* |

HB HB HB SB VDW VDW 2 HB HB HB |

153.3 | GluP22 | 155.2 | HB HB HB SB VDW VDW 2 HB HB |

Tyr52* Thr54* Ser68* Arg81* Trp106 Phe123* Asn134* Tyr138* |

| Lys79* Arg81* Phe83* Leu94* Phe123* Val125 |

SB + HB SB VDW VDW VDW VDW |

102.3 | AspP23 | 109.2 | SB + HB SB VDW VDW VDW VDW |

Lys79* Arg81* Phe83* Leu94* Trp106 Phe123* |

| Val125 Asn134* |

VDW VDW |

61.4 | ValP24 | 46.2 | VDW VDW |

Trp106 Asn134* |

| Gln127 | HB | 22.8 | GlyP25 | 3.5 | – | – |

| Lys79* Leu94* Thr104* |

HB VDW VDW |

65.2 | SerP26 | 58.0 | VDW | Trp106 |

| Lys79* | VDW | 28.4 | AsnP27 | 42.6 | VDW | Glu100 |

| Gln127 | HB | 29.5 | LysP28 | – | – | – |

-

Randomized residues are shown in bold, identical residues between US7 and H1GA are indicated by asterisks. Analysis was carried out using the program CONTACT (Winn et al. 2011) with minor manual adjustments using distances ≤4 Å for hydrogen bonds (HB), salt bridges (SB) and van der Waals contacts (VDW), while the buried surface areas (BSA) of the interfacing Aβ40 peptide residues were calculated with PISA (Krissinel and Henrick 2007).

Due to the extraordinary target affinity and the pronounced Aβ40 aggregation-blocking activity of the anticalin H1GA its interactions with the bound peptide are of particular interest. H1GA was selected in an independent phage display campaign and differs in 13 amino acid positions from US7 (Rauth et al. 2016). This explains its mode of crystallisation in a different crystal form with four protein•peptide complexes in the a.u. (Table 1). Polypeptide chain A showed the lowest crystallographic B factors overall and, thus, was chosen for detailed analysis. Compared with the structure of the complex between US7 and the Aβ40 peptide the conformations of both anticalins with the bound peptide are highly similar, resulting in a very low RMSD of 0.306 Å for the 58 conserved Cα positions and of 1.903 Å for all 172 common Cα atoms of the polypeptide chains. Similar to US7, the central segment of the Aβ40 peptide ligand (P17–P27: LVFFAEDVGSN, minimal epitope underlined) showed well defined electron density also in complex with the anticalin H1GA (Figure 2).

A striking feature of this bound Aβ segment is the cluster of five strongly hydrophobic side chains, LVFFP17–P20 and ValP24, with a negatively charged Glu-Asp dipeptidyl moiety in between (Figure 4). This coiled stretch, with the hydrophobic side chains pointing into different directions, constitutes the experimentally verified minimal epitope (Rauth et al. 2016). Notably, the LVFF moiety forms the first in a series of altogether three (four in the US7 complex) adjacent tight turns (Figure 4A): LeuP17–PheP20, turn 1; AlaP21–ValP24, turn 2; AspP23–SerP26, turn 3. Turn 3 is a type II β-turn with the canonical H-bond between the main chain C=O(i) and N-H(i + 3) – as well as a Gly residue at position i + 2 – whereas turns 1 and 2 belong to the "open" class of β-turns with a distance between Cα(i) and Cα(i + 3) of less than 7 Å (Chou 2000; Wilmot and Thornton 1988). Interestingly, in the US7•Aβ40 complex, where LysP28 is also visible in the higher resolution electron density map (cf. Table 1), a fourth β-turn becomes evident, formed by residues GlyP25–LysP28 and belonging to type I, though with a geometrically non-ideal intra-backbone H-bond (not shown). Overall, this leads to a peculiar zigzag-bend conformation for the central Aβ segment in both anticalin complexes.

Analysis with PISA (Krissinel and Henrick 2007) revealed an interface area of 886 Å2 for the visible part of the Aβ40 peptide, which constitutes 65% of the total solvent accessible surface of the peptide stretch P17–P27. Within this interface, 9 hydrogen bonds and 3 salt bridges are formed (Table 2). A detailed interaction analysis using CONTACT (CCP4 1994) revealed that 11 peptide residues interact (within a radius of 4.0 Å) with 22 residues of the anticalin H1GA. The majority of anticalin residues that play a role for complex formation (18 of 22) interact via their side chains. Of note, 11 of these 18 residues had been mutated during the generation of H1GA (cf. Table 2 and Figure 1). As expected from the biochemical epitope mapping analysis (Rauth et al. 2016), the majority of interactions involve the central Aβ positions PheP19, PheP20, AlaP21, GluP22 and AspP23 (see also further below).

While the first visible N-terminal residues of the bound Aβ peptide, LeuP17 and ValP18, are located at the entrance of the ligand pocket and still interact with the solvent, the following residue, PheP19, forms tight contacts with the side chains of Lys79 and Ser68 of the anticalin. Interestingly, the peculiar residue pair PheP19 and PheP20 within the central epitope of the Aβ peptide rests with almost oppositely oriented aromatic side chains in two distinct hydrophobic subpockets (Figure 4C). The phenyl group of PheP19 is sandwiched between residues Lys79 and Tyr52 while PheP20 is wedged between Leu49 and Tyr52, involving an edge-to-face contact with the aromatic side chain (Figure 4B).

The following small residue AlaP21 is placed in a canyon formed by the hydrophobic side chains Val33, Ala36, Thr136 and Tyr138 of the engineered lipocalin (Figure 4B and C). The deepest point of this canyon is occupied by GluP22, which is anchored through an extended polar network between its carboxylate group and the guanidinium group of Arg81, comprising numerous hydrogen bonds and one salt bridge (Table 2). Beyond that, this residue forms a hydrogen bond to the only water molecule within the binding site, which itself is engaged in two hydrogen bonds to Tyr52 and Lys79.

The next peptide residue, AspP23, is also deeply buried and forms two salt bridges and three hydrogen bonds with the side chains of Lys79 and Arg81. ValP24 is situated further up in the cavity again, close to LeuP17, and interacts with residues Trp106 and Asn134 of the anticalin. While GlyP25 is not engaged in a close interaction with H1GA – in contrast with the anticalin US7 (cf. Table 2) – SerP26 forms a final contact with Trp106 and leads into the solvent-exposed disordered C-terminal peptide segment of Aβ. The last visible peptide residue in the H1GA•Aβ40 complex, AsnP27, just loosely interacts with the anticalin.

Similarities and differences between the individual anticalin•Aβ complexes

Although the anticalin US7 differs in 13 amino acid positions from H1GA (cf. Figure 1) and it crystallized non-isomorphously, the structure of its binding site and the mode of complex formation with Aβ, including the conformation of the bound peptide, are surprisingly similar. Nevertheless, there are some notable structural differences (Figure 3A). In particular, the binding pocket of H1GA is slightly larger, mostly because loop #4 is bent more outward and the side chain of Leu at position 49 occupies less space than the corresponding Trp side chain in US7.

According to an analysis with CONTACT, there are altogether 23 residues in US7 that intertact with the Aβ peptide (Table 2) while 14 contact residues are identical in both anticalins. Further analysis of the buried surface area of the Aβ peptide with PISA revealed that predominant interactions with both anticalins are made by residues ValP18 to SerP26 (Table 2 and Figure 4B). On the side of the anticalin, most interactions arise from identical residues between US7 and H1GA. Contributions by differing residues are confined to the less tightly bound ends of the central peptide epitope, e.g. His77 in US7 versus Leu77 in H1GA as well as Trp49/Leu49 and Gln127/Ala127, or to the periphery of the ligand pocket, e.g. Val36/Ala36. An interesting exception is the linked pair of distinct residues Ala106/Val125 in US7 versus Trp106/Glu125 in H1GA (Figure 3D), which will be discussed below.

Of the 8 differing residues that form contacts with the Aβ peptide in US7 and H1GA (see Table 2), some are associated with significant deviations in the peptide binding mode and/or altered loop conformations. Trp at position 49 in US7 has a slightly smaller contact area compared to Leu in H1GA (42.1 versus 43.1 Å2; Figure 4B) but is involved in a π–π stacking of its aromatic ring with the side chain of PheP20 (not shown). In H1GA, Asp72 makes a van der Waals contact to ValP18, which is not the case for Gly72 in US7. The two linked mutations Tyr106 to Ala/Trp and Lys125 to Val/Glu are responsible for the most prominent structural differences between the complexes of US7 and H1GA with the Aβ40 peptide. Trp106 in the H1GA structure provides a much larger hydrophobic interface with the peptide residues AspP23 and ValP24 than the Ala residue in US7 (53.2 versus 7.0 Å2). This Trp side chain also adopts the role of the Val125 side chain which is involved in a contact with the bound peptide in US7 (Figure 3D). Conversely, in H1GA the corresponding Glu125 side chain is moved away from the binding site by the large indole group of Trp106, which is reflected by the much larger contact surface of 32.6 Å2 for Val125 in US7 compared with just 1.8 Å2 for Glu125 in H1GA. Apart from the kinked side chain conformation of Glu125, space for the bulky side chain of Trp106 is further provided in H1GA by pushing outward the first two residues of β-strand F (Thr104 and Ser105) and the last three residues of β-strand G (Lys124 to Val126) (Figure 3D).

The conformation of the flanking loops is affected, too. Loop #2 (Gly72–Lys75 in US7, Asp73–Lys74 in H1GA) is bent outward in US7, with deviations up to 2.5 Å at the Cα atom of Asp73. Furthermore, loop #3 in H1GA has a considerably different conformation compared to its counterpart in US7: the N-terminal loop segment, Gly95–Pro101, is bent toward the binding site, whereas the C-terminal segment, Gly102–Thr104, leans outward (Figure 3A). Finally, loop #4 is also bent outward by up to 7.0 Å in H1GA (at the Cα atom of Asn129) compared to the US7 structure. The conformational deviation of loop #4 ends at the differing residues Ser132/Thr132 (US7/H1GA) where the Ser hydroxyl group adopts a distinct rotamer and forms an additional water-mediated hydrogen bond to the peptide at residue ValP24.

In spite of these structural differences between the two anticalins, the position and conformation of the bound Aβ40 peptide in the complexes with H1GA and US7 is surprisingly similar. Superposition of the 11 Cα atoms of the visible peptide segment LeuP17–AsnP27 results in a very low RMSD value of 0.83 Å. There are just a few smaller deviations either due to intrinsic conformational plasticity of the peptide or as a result of distinct contacts with the two anticalins. For example, the Cζ carbon atoms of the equivalent PheP20 residues are mutually shifted by 0.7 Å. In US7, this residue is in contact with the indole side chain of Trp49 through face-to-face-stacking, as mentioned above, while in H1GA this is not possible with the corresponding Leu residue (Figure 4B).

A sequence alignment with wtLcn2 (Rauth et al. 2016) revealed mutually identical amino acids in 7 of the 20 randomized positions (Tyr52, Ser68, Gly70, Lys79, Arg81, Arg96, Asn134) between H1GA and US7 (Figure 1), of which 3 are unchanged from wtLcn2. According to the crystal structure of the H1GA•Aβ40 complex (see Table 2), each of these residues, except for Arg96, is involved in the binding of the Aβ peptide, which explains their high conservation amongst the set of all three independently selected anticalins, including S1A4 (Rauth et al. 2016). The two basic residues Lys79 and Arg81 seem particularly important in this regard since they form hydrogen bonds as well as salt bridges with the central pair of acidic residues within the Aβ epitope, GluP22 and AspP23 (Figure 3E).

In another aspect, the anticalin H1GA was derived from the initially selected anti-Aβ anticalin H1G1 by replacing an unpaired Cys residue that emerged at the randomized position 36 on the N-terminal side of loop #1 (Rauth et al. 2016). This residue was rationally exchanged by Ala or Val mainly to prevent non-physiological crosslinking and/or protein misfolding under oxidizing conditions. While, as anticipated, both exchanges resulted in much improved biochemical protein properties the Ala mutation, unexpectedly, led to a 70-fold higher affinity towards the Aβ40 peptide. To explore the structural environment of Cys36, we modelled this residue into the H1GA crystal structure (Figure 3F). The thiol side chain in the most probable rotamer gets directed toward the Aβ peptide, leading to van der Waals contacts with PheP20 and AlaP21. However, it seems that this contact is too tight such that removal of the bulky sulfur atom via replacement by Ala – in contrast to Val – results in a sterically more favourable situation.

Comparison between the bound Aβ epitope and its conformation in fibril structures or other peptide complexes

A search through the protein data bank (PDB) for structurally related peptides with the Aβ peptide segment LeuP17–AsnP27 from the US7 complex using the SPASM server (Madsen and Kleywegt 2002) revealed only poor hits without obvious similarities. Even the first hit (PDB ID: 1AK0) showed a rather high RMSD value of 1.88 Å for a totally unrelated peptide sequence (ILGSSSSSYLASI) as part of a larger protein structure, nuclease P1 (Romier et al. 1998). While this best matching peptide comprises several turns, its conformation differs significantly from the one of the Aβ peptide segment. Hence, this analysis indicated a unique conformation of the central Aβ peptide moiety as seen in the complexes with the two different anticalins. Considering that the ligand pockets of H1GA and US7 differ by 13 residues, as described above, and that both anticalins were selected using different procedures and even different target molecules – the biotin-labelled full length synthetic Aβ40 peptide in one case and a recombinant thioredoxin-Aβ28 hybrid protein in the other (Rauth et al. 2016) – suggests that the peculiar structure of the central region of the Aβ peptide observed in the bound state represents a preferred conformation that may preexist in solution.

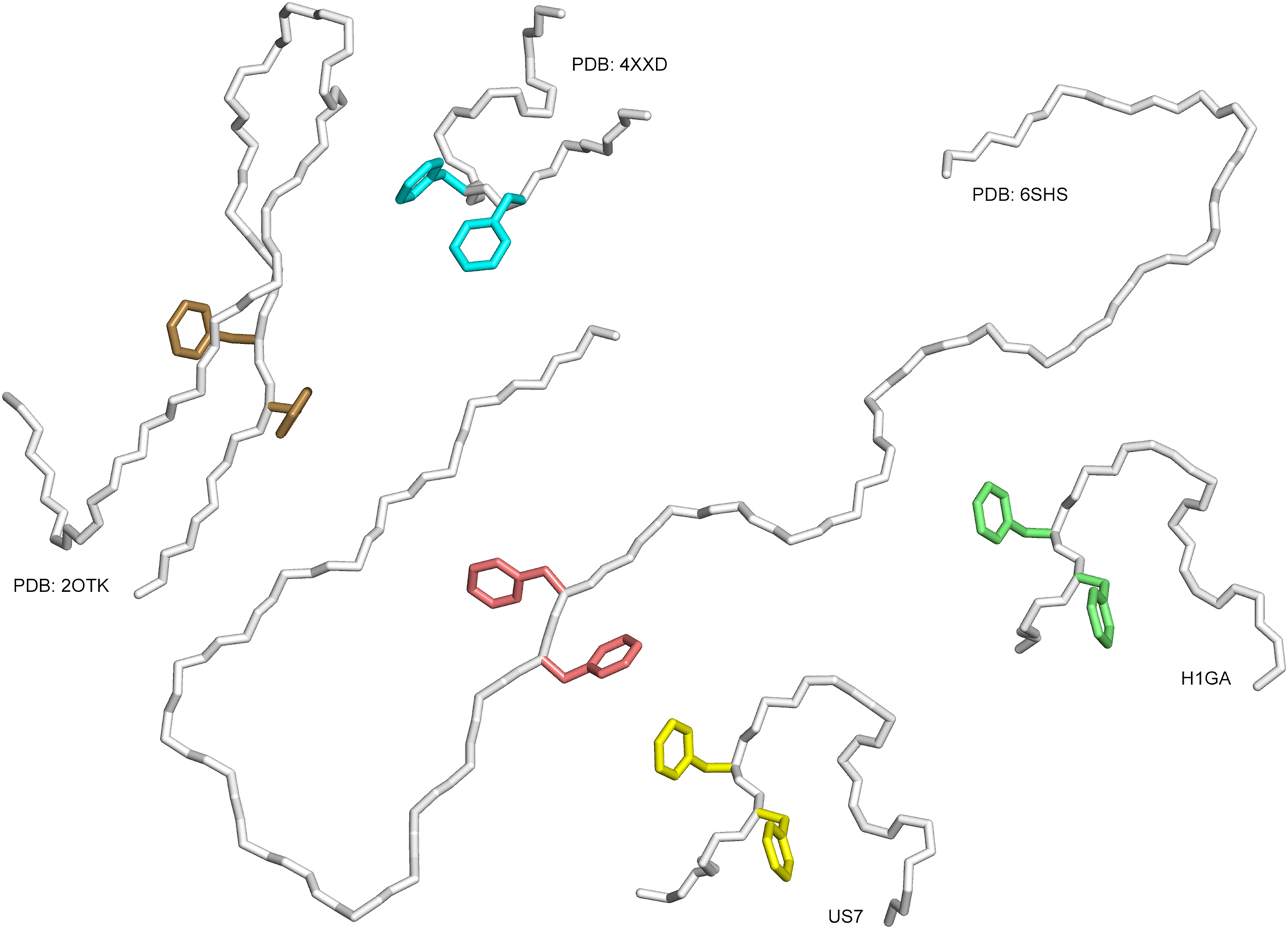

The structural properties of Aβ peptides have been analysed in many studies before, both in the free monomeric state, in complexes with antibodies and also with alternative binding proteins and as part of macromolecular fibrils. Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations for Aβ peptides and their oligomers have been performed (Ciudad et al. 2020), however, with no hint on a peculiar conformation of its central moiety. To investigate the functional significance of the zigzag-bend seen here for the Aβ peptide when bound to the anticalins, we compared its conformation with several relevant coordinate sets for Aβ peptides or their complexes: the NMR structure of Aβ40 bound to a dimeric affibody protein (PDB ID: 2OTK; Aβ residues 16–40 resolved) (Hoyer et al. 2008), the high resolution cryo-EM structure of native Aβ amyloid fibrils (PDB ID: 6SHS) (Kollmer et al. 2019) and the X-ray structure of Aβ in complex with solanezumab (PDB ID: 4XXD; Aβ residues 16–26 resolved) (Crespi et al. 2015). All these Aβ structures were compared with the peptide moiety in the higher-resolution US7•Aβ40 complex using as reference the characteristic central PheP19/PheP20 motif, which was resolved in all experimental structures (Figure 5).

Distinct conformations of the Aβ40 peptide in different structural environments:

(i) In complex with the anticalins from this study, H1GA and US7, (ii) in complex with solanezumab (PDB ID: 4XXD), (iii) in complex with a dimeric affibody protein (PDB ID: 2OTK) and (iv) as part of an amyloid fibril purified from Alzheimer’s brain tissue and elucidated by cryo-EM (PDB ID: 6SHS). The peptides are shown as Cα traces, side chains of the central residues PheP19 and PheP20 are depicted as sticks.

Remarkably, none of the superimposed structures share the unique backbone conformation seen for the anticalin-bound Aβ peptide. Only the feature of the two Phe side chains pointing into more or less opposite directions is seen in the amyloid fibril structure and also in the complex with the dimerized affibody. However, the peptide backbone surrounding these Phe residues is extended in both structures and not compactly folded as in the anticalin complexes. Nevertheless, the feature of the two exposed large hydrophobic side chains appears to contribute to the formation of macromolecular β-amyloid fibrils (Kollmer et al. 2019), where PheP20 in one Aβ subunit nestles among residues PheP4 and ValP18 of its own N-terminal peptide segment whereas PheP19 is engaged in close contacts to residues LeuP17, AlaP21, ValP24 and IleP31 of a neighbouring strand. Obviously, the anticalins US7 und H1GA can provide an alternative hydrophobic environment for the pair of Phe side chains and, thus, compete with this kind of Aβ aggregation.

Comparison between the Aβ40 peptide in complex with anticalins and with a clinical-stage anti-Aβ antibody

The crystal structure of solanezumab, one of the leading antibodies targeting Aβ that has been tested in multiple phase III clinical trials, has been published (PDB ID: 4XXD) (Crespi et al. 2015). Similar to the anticalins described here, solanezumab recognizes a central epitope in the Aβ peptide. This mAb was shown to reduce brain Aβ burden in transgenic mouse models of AD by sequestering plasma Aβ and favouring efflux from the CNS, which is accompanied by a decrease of Aβ levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (DeMattos et al. 2002). In the crystal structure of solanezumab, the residues P16–P26 (KLVFFAEDVGS) exhibit unambiguous and continuous electron density in the most complete of the two macromolecular assemblies present in the a.u.

At first glance, there are similarities between this Fab•Aβ complex and the ones of the anticalins. First, a linear peptide epitope of almost the same sequence and length (11–13 residues) is recognized by both types of binding proteins. Second, the buried surface of the bound Aβ segment has a similar size in all three complexes, with 886 Å2 and 868 Å2 for the anticalins H1GA and US7, respectively, and 960 Å2 in the case of solanezumab. Third, despite differing backbone conformations, the dominant residues PheP19 and PheP20 are both deeply buried at the center of each binding site.

On the other hand, the conformation of the Aβ peptide bound to the solanezumab Fab fragment is quite different from both anticalin complexes. In the Fab complex the N-terminal peptide moiety, i.e. residues LysP16–PheP19, adopts an extended conformation, whereas the C-terminal segment, PheP20–SerP26, exhibits a helical structure and projects out of the binding site. The core of the Aβ epitope is formed by the PheP19/PheP20 motif, however, this time with both aromatic side chains pointing into the same direction. This dipeptide moiety is deeply buried at the bottom of the paratope, within the cleft between the pair of variable immunoglobulin domains. This is a very different Aβ conformation from the one seen in the anticalin complexes, where the two aromatic side chains point into almost opposite directions and each of them rests in a distinct hydrophobic subpocket. In fact, superposition of the Cα-atoms of residues LeuP17–SerP26 in the Fab complex with the corresponding peptide segment bound to US7 or H1GA results in rather high RMSD values of ∼2.7 Å. For comparison, the corresponding RMSD value between the two anticalin complexes is as low as 0.27 Å.

Furthermore, the individual interactions with the respective binding protein and, in particular, the pattern of Aβ peptide residues that form hydrogen bonds or salt bridges are markedly different. In solanezumab only the N-terminal peptide residues, LysP16, LeuP17, ValP18, PheP19, AlaP21 and AspP23, form tight interactions, mainly via the main chain. In the anticalin complexes, however, hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are formed primarily by the C-terminal residues: AlaP21, GluP22 and AspP23 in the H1GA complex and PheP20, AlaP21, GluP22, AspP23, GlyP25, SerP26 and LysP28 in the US7 complex (see Table 2). Whereas the negatively charged Aβ residue AspP23 is involved in the formation of a salt bridge also in solanezumab, only the anticalin complexes comprise an additional salt bridge with the neighbouring GluP22.

Cross-reactivity analysis of the anticalin H1GA between Aβ peptides and related sequences occurring in abundant plasma proteins

Solanezumab, as well as other anti-Aβ antibodies such as crenezumab, are known to cross-react with human plasma proteins, which is thought to lead to partial saturation of the biopharmaceutical upon systemic administration to patients and, thus, to negatively affect the therapy of AD (Crespi et al. 2015; Watt et al. 2014). Consequently, it was of interest whether the anticalins selected against Aβ40, in particular H1GA, might show a similar interaction with those proteins. The 12 plasma proteins in question (Watt et al. 2014) (see Table 3) share high sequence similarity, or even complete identity, with Aβ around the LVFF motif at the core of the linear epitope seen both in the solanezumab complex and also in our anticalin structures, as discussed above.

Sequences spotted for the analysis of the cross-reactivity of the anti-Aβ anticalin H1GA to other epitope-related sequences from various human plasma proteins.

| Peptide number | Sequence | Protein | UniProt ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | NSGVDEAFFVLKQHHV | Reverse Aβ | – |

| 1 | VHHQKLVFFAEDVGSN | Aβ | (P05067 = APP) |

| 2 | PDDTKLVNFAEDKGES | Probable ATP-dependent DNA helicase | A2PYH4 |

| 3 | LIKGKLVFFLNSGNAK | Contactin-associated protein-like 3B | Q96NU0 |

| 4 | PSWNKLVFFEVSPVSF | 2-Oxoglutarate and iron-dependent oxygenase domain-containing protein | Q8N543 |

| 5 | PRCQQPVFFAEKVSSL | Cysteine-rich protein 3 | Q6Q6R5 |

| 6 | GLILYLVFFAPGMGPM | Solute carrier family 2, member 13 | Q96QE2 |

| 7 | LLARQLVFFAGALFAA | Autophagy-related protein 9B | Q674R7 |

| 8 | PFLSKLIFFNVSEHDY | Neurotrimin | Q9P121 |

| 9 | VYKNKLIFFGGYGYLP | Kelch domain containing 2 | Q9Y2U9 |

| 10 | QVSDWLIFFASLGSFL | Interleukin-12 receptor beta-1 | P42701 |

| 11 | ARALQYAFFAERKANK | Peroxisomal bifunctional enzyme | Q08426 |

| 12 | GPNKPESGFAEDSAAR | Cardiomyopathy associated 3 (corrected) | A4UGR9 |

| 13 | PPVVCSHFAEDFWPEQ | Zinc finger protein 429 | Q86V71 |

| 0 | SAWSHPQFEKGG | Strep-tag II | – |

| −0 | GGKEFQPHSWAS | Reverse Strep-tag II | – |

-

Sequence homology to Aβ is underlined. The spotted 8mer, 12mer and 16mer amino acid sequence, respectively, is shown in bold, black and grey letters.

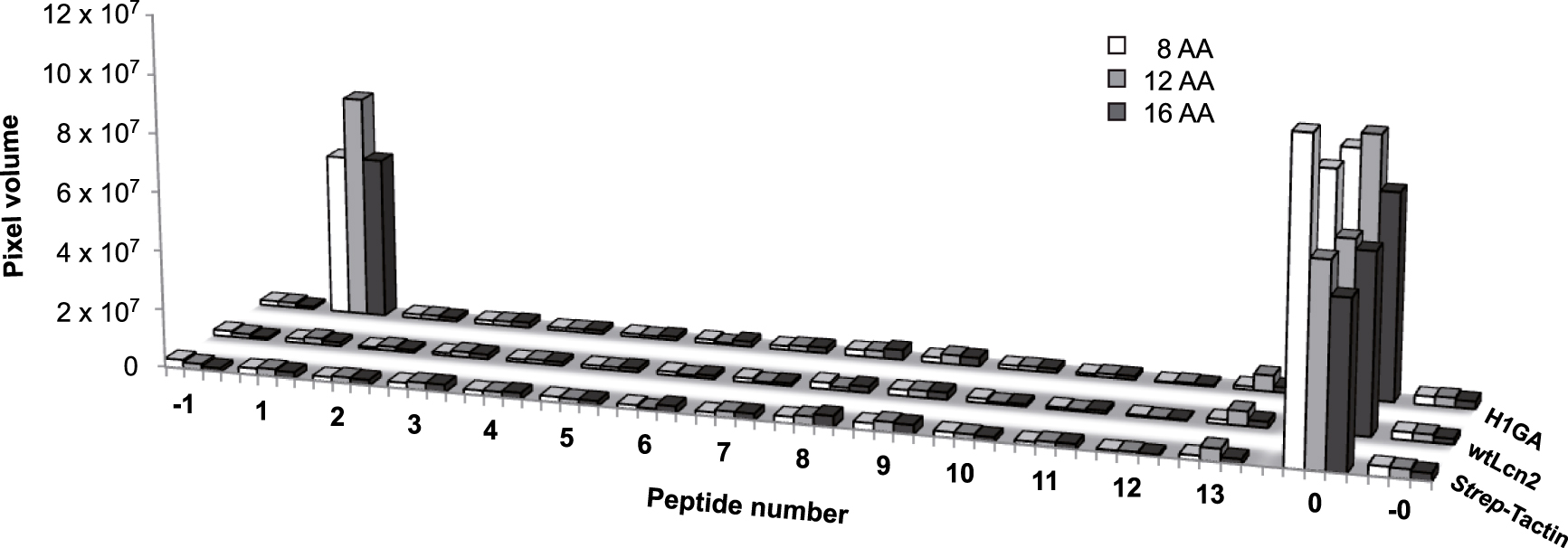

Hence, we investigated the potential recognition of those related epitope sequences present in the human plasma proteins by the Aβ-specific anticalin H1GA using the SPOT technique. This method, which employs peptides synthesized on a hydrophilic cellulose membrane as solid support (Frank 2002), was successfully applied before in order to precisely identify the minimal epitope sequence recognized by our selected anticalins (Rauth et al. 2016). Now, a set of 12 peptide sequences occurring in those relevant human plasma proteins and having similarity to the linear epitope 18VFFAED23 recognized by H1GA were synthesized with varying lengths, as octamer, dodecamer and hexadecamer peptides, on the membrane along with the target peptide, Aβ16–23 (Figure 6).

Investigation of potential cross-reactivity of the Aβ-specific anticalin H1GA with related epitope sequences in human plasma proteins (Table 3) using the SPOT technique. Twelve protein sequences (2–13) with similarity to the linear epitope 18VFFAED23 recognized by H1GA were synthesized as octamer (8 AA), dodecamer (12 AA) and hexadecamer (16 AA) peptides onto a hydrophilic cellulose membrane together with the original target Aβ16–23 (1). The reverse sequence of Aβ16–23 served as negative control (−1). The membranes were incubated with the anti-Aβ anticalin, followed by detection via the Strep-tag II. The synthetic Strep-tag II peptide itself was present on the same membrane as a positive control (0) and also as reverse sequence (−0). Apart from the very low non-specific background signals that were also seen without anticalin, or for wtLcn2, H1GA revealed binding activity exclusively to its target sequence Aβ16–23.

After incubation with the anti-Aβ anticalin, only the peptide fragments derived from Aβ itself gave rise to pronounced signals (for all three lengths). The very low signals detected for the 12 plasma protein sequences were in the same range as seen for the reverse Aβ peptide fragment, serving as a negative control, or for the wtLcn2 protein, which was applied in parallel, or with the secondary detection reagent alone (see Figure 6). These data demonstrate that the anticalin H1GA binds to its Aβ target sequence with unparalleled specificity, which is explained by the tight structural complex formation with this peptide segment, also involving flanking residues of the central LVFF motif as described in detail above.

Conclusions

Using X-ray crystallographic analysis we have elucidated the structural mechanism how the central region of the Aβ40 peptide is specifically recognized and tightly bound by two different anticalins. An unexpected finding was that, although selected in independent phage display campaigns and employing the target peptide in different molecular formats, both anticalins, H1GA and US7, bind to the same peptide epitope, which in both complexes adopts an unprecedented compact zigzag-bend conformation. Together with the earlier observation that in particular the anticalin H1GA suppresses Aβ aggregation already at substoichiometric levels, this feature supports the hypothesis that these anticalins selectively bind a peculiar conformation of Aβ40 which might represent a relevant intermediate during oligomerization followed by aggregate and/or fibril formation. Hence, apart from a simple stoichiometric scavenging effect – as aspired in the light of the peripheral sink hypothesis – our structural analysis indicates that these anticalins may prevent Aβ oligomerization via a conformational selection mechanism, thus blocking the presumably most toxic event in the early molecular pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Together with the experimentally proven high target specificity, our study illustrates the potential of generating alternative binding proteins, beyond conventional antibodies, via advanced protein design as drug candidates for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and methods

Protein crystallization and X-ray data collection

The anticalins H1GA and US7 as well as the recombinant wild-type lipocalin (wtLcn) were prepared as soluble proteins, carrying the C-terminal Strep-tag II, by secretion in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity from the periplasmic cell extract via StrepTactin affinity chromatography (Schmidt and Skerra 2007) and size exclusion chromatography as previously described (Rauth et al. 2016). The Aβ40 peptide was acquired from the Keck Biotechnology Resource Laboratory (Yale University, New Haven, CT). The short hexapeptide VFFAED (N-terminally acetylated and C-terminally amidated) was purchased from Centic Biotec (Weimar, Germany).

The monomeric Aβ40 peptide dissolved in water (Rauth et al. 2016) was co-crystallized with the anticalins at 1.2:1 molar ratio using solutions of 0.8 mg/ml H1GA in 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl and 2 mg/ml US7 in 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 115 mM NaCl. After incubation for 1 h at 4 °C the mixtures were concentrated to 17 and 11 mg/ml, respectively, using amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filter units (10 kDa cutoff; Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). After successful search for suitable precipitation conditions using an in-house nanodrop precipitant screen, diffraction quality crystals were obtained at 20 °C using the hanging drop vapour diffusion technique from the following mixtures: 1 μl anticalin•Aβ40 solution with 1 μl 24% (w/v) PEG 3350 for H1GA and with 1 μl 30% (w/v) PEG 4000, 100 mM Na-acetate pH 5.25 for US7. For co-crystallization of US7 with the short VFFAED peptide, 1 μl of the purified anticalin (12 mg/ml) was mixed with 1 μl of the synthetic peptide (5 mM), both dissolved in 10 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0, 115 mM NaCl, followed by the addition of 1 μl reservoir solution consisting of 27% (w/v) PEG 8000, 100 mM MES/NaOH pH 6.5. Crystals were transferred into their respective precipitant buffer supplemented with 20% (v/v) or 10% (v/v) PEG 200 as cryoprotectant for the US7 and H1GA complexes, respectively, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at beamlines 14.1 and 14.2 of the BESSY synchroton (Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin, Germany). All anticalin•peptide complexes crystallized in the space group P212121 (Table 1), however, with different numbers of protein•peptide complexes in the asymmetric unit (a.u.).

Crystal structure determination

X-ray diffraction data were processed with MOSFLM and scaled with SCALA (Winn et al. 2011). Molecular replacement was carried out with MOLREP for the US7 complexes and with Phaser for the H1GA complexes using the coordinates of the natural Lcn2 (PDB ID: 1L6M) (Goetz et al. 2002) as search model. The electron density of H1GA•Aβ40 was initially averaged for non-crystallographic symmetry with RESOLVE (Terwilliger 2000). Atomic models were built with Coot (Emsley et al. 2010) and refined with Refmac5 (Murshudov et al. 1997) in iterative cycles using manual correction. Water molecules were added to all models using ARP/wARP (Langer et al. 2008) while rotamers of Asn and Gln residues were adjusted with NQ-flipper (Weichenberger and Sippl 2007). The refined structural models were validated with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al. 1993) and WHAT_CHECK (Hooft et al. 1996) and via the MolProbity server (Williams et al. 2018). Secondary structures were assigned using DSSP (Kabsch and Sander 1983), and protein-ligand contact surfaces were calculated with PISA (Krissinel and Henrick 2007). Molecular graphics and structural superpositions were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano 2002).

For the US7•Aβ40 complex, electron density was resolved for 172 of the 188 protein residues, namely Asp6–Asp177, whereas the Aβ40 peptide was only defined in its central region for residues LysP16–LysP28. The electron density of the structurally variable loops #1 and #3 at the entrance to the ligand pocket, in particular positions Ser41–Asp45 and Ile97–Arg103, had low quality and these segments were tentatively modelled with plausible stereochemistry. The electron density map of the US7•VFFAED complex allowed model building for residues Leu7–Asp177 together with the entire epitope peptide. The N-terminal acetyl group as well as the C-terminal amide nitrogen of the peptide were clearly visible in the electron density. Again, however, poor density was seen for residues Ser41–Asp47 and Lys98–Gly102 in the loop regions. In case of the H1GA•Aβ40 complex there was continuous electron density in all four polypeptide chains within the a.u. (A, B, C, D) for residues Ser5–Asp177, Asp6–Asp177, Ser5–Gly178, and Leu7–Asp177, respectively. The four copies of the Aβ40 peptide were defined throughout residues LeuP17–AsnP27 (chains E and F bound to chains A and B, respectively) and ValP18–SerP26 (chains G and H bound to chains C and D, respectively). Due to their overall lower B-factors and the better definition of electron density both for the anticalin and the bound peptide ligand, chains A and E were chosen for the structural analysis of H1GA as described in the text.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors of the refined crystal structures US7•Aβ40, US7•VFFAED and H1GA•Aβ40 have been deposited at the PDB, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ), under accession codes 4MVI, 4MVK and 4MVL, respectively.

Epitope-peptide binding assay

To investigate the specificity of the anticalin H1GA towards its prescribed target Aβ40, 12 human plasma proteins showing sequence homology with the central region of the linear Aβ epitope, KLVFFAED (Watt et al. 2014) (Table 3), were tested for possible cross-reactivity using the SPOT technique (Frank 2002). The relevant sequences were prepared as octamers, dodecamers and hexadecamers via fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (FMOC) solid-phase peptide synthesis on a MultiPep RS instrument (Intavis, Köln, Germany) using an amino-PEG500-derivatized cellulose membrane (Intavis) as support for C-terminal immobilisation. After final acetylation of the N-termini, side chains were deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid as described (Zander et al. 2007). The Strep-tag II 10mer peptide (Schmidt and Skerra 2007) was synthesized on the same membrane with a C-terminal Gly–Gly spacer and served as an internal positive control for detection. Both the Aβ peptide fragments and the Strep-tag II were also synthesized with reverse sequences as negative controls. After completion of the synthesis, the membrane was washed once with ethanol, three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), blocked with 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in PBS/Tween for 1 h and washed 3 times with PBS/T. Three copies of the membrane were prepared in this manner. The first and second membrane were probed with the anticalin H1GA or wtLcn2, respectively (100 nM each), in PBS/T for 1 h, followed by washing three times with PBS/T. The membrane was subsequently incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of Chromeo546 labeled StrepTactin (IBA, Göttingen, Germany) in PBS/T for 1 h to detect the bound recombinant lipocalin protein via its C-terminal Strep-tag II. To quantify any background signal arising from the use of this secondary reagent, the third membrane was incubated in the same manner while skipping the incubation with the lipocalin protein. Finally, the membranes were washed three times with PBS/T prior to signal detection on an Ettan DIGE system (GE Healthcare, Freiburg Germany) using the Cy3 channel. Quantification of the fluorescence signals including background subtraction was performed using Quant software (TotalLab, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, UK).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Manfred S. Weiss and Dr. Sandra Pühringer (Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin, Germany) for technical support at BESSY beamlines 14.1 and 14.2, respectively, Dr. Lars Friedrich (TUM) for advice in the SPOT synthesis, and Dr. André Schiefner (TUM) for structural discussions.

-

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work was financially supported by the Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin, Germany.

-

Conflict of interest statement: A.S. is founder and shareholder of Pieris Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article. Anticalin® is a registered trademark of Pieris Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Germany.

References

Achatz, S., Jarasch, A., and Skerra, A. (2022). Structural plasticity in the loop region of engineered lipocalins with novel ligand specificities, so-called anticalins. J. Struct. Biol. X 6: 100054, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjsbx.2021.100054.Search in Google Scholar

Arndt, J.W., Qian, F., Smith, B.A., Quan, C., Kilambi, K.P., Bush, M.W., Walz, T., Pepinsky, R.B., Bussière, T., Hamann, S., et al.. (2018). Structural and kinetic basis for the selectivity of aducanumab for aggregated forms of amyloid-β. Sci. Rep. 8: 6412, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24501-0.Search in Google Scholar

Arndt, U.W., Crowther, R.A., and Mallett, J.F.W. (1968). A computer-linked cathode-ray tube microdensitometer for X-ray crystallography. J. Phys. E Sci. Instrum. 1: 510–516, https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3735/1/5/303.Search in Google Scholar

Bateman, R.J., Aisen, P.S., De Strooper, B., Fox, N.C., Lemere, C.A., Ringman, J.M., Salloway, S., Sperling, R.A., Windisch, M., and Xiong, C. (2011). Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 3: 1, https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt59.Search in Google Scholar

Brunger, A.T. (1997). Free R value: cross-validation in crystallography. Methods Enzymol. 277: 366–396, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77021-6.Search in Google Scholar

Busche, M.A., Chen, X., Henning, H.A., Reichwald, J., Staufenbiel, M., Sakmann, B., and Konnerth, A. (2012). Critical role of soluble amyloid-β for early hippocampal hyperactivity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109: 8740–8745, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1206171109.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

CCP4 (1994). The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 50: 760–763, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0907444994003112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Chou, K.C. (2000). Prediction of tight turns and their types in proteins. Anal. Biochem. 286: 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.2000.4757.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Ciudad, S., Puig, E., Botzanowski, T., Meigooni, M., Arango, A.S., Do, J., Mayzel, M., Bayoumi, M., Chaignepain, S., Maglia, G., et al.. (2020). Aβ(1-42) tetramer and octamer structures reveal edge conductivity pores as a mechanism for membrane damage. Nat. Commun. 11: 3014, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16566-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Crespi, G.A., Hermans, S.J., Parker, M.W., and Miles, L.A. (2015). Molecular basis for mid-region amyloid-β capture by leading Alzheimer’s disease immunotherapies. Sci. Rep. 5: 9649, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09649.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Decourt, B., Boumelhem, F., Pope, E.D.3rd, Shi, J., Mari, Z., and Sabbagh, M.N. (2021). Critical appraisal of amyloid lowering agents in AD. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 21: 39, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-021-01125-y.Search in Google Scholar

DeLano, W.L. (2002). The PyMOL molecular graphics system. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific.Search in Google Scholar

DeMattos, R.B., Bales, K.R., Cummins, D.J., Dodart, J.C., Paul, S.M., and Holtzman, D.M. (2001). Peripheral anti-Aβ antibody alters CNS and plasma Aβ clearance and decreases brain Aβ burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98: 8850–8855, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.151261398.Search in Google Scholar

DeMattos, R.B., Bales, K.R., Cummins, D.J., Paul, S.M., and Holtzman, D.M. (2002). Brain to plasma amyloid-β efflux: a measure of brain amyloid burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 295: 2264–2267, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067568.Search in Google Scholar

DeTure, M.A. and Dickson, D.W. (2019). The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 14: 32, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13024-019-0333-5.Search in Google Scholar

Deuschle, F.C., Ilyukhina, E., and Skerra, A. (2021). Anticalin® proteins: from bench to bedside. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 21: 509–518, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2021.1839046.Search in Google Scholar

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W.G., and Cowtan, K. (2010). Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66: 486–501, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0907444910007493.Search in Google Scholar

Frank, R. (2002). The SPOT-synthesis technique. Synthetic peptide arrays on membrane supports–principles and applications. J. Immunol. Methods 267: 13–26, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00137-0.Search in Google Scholar

Gebauer, M., Schiefner, A., Matschiner, G., and Skerra, A. (2013). Combinatorial design of an anticalin directed against the extra-domain B for the specific targeting of oncofetal fibronectin. J. Mol. Biol. 425: 780–802, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2012.12.004.Search in Google Scholar

Goetz, D.H., Holmes, M.A., Borregaard, N., Bluhm, M.E., Raymond, K.N., and Strong, R.K. (2002). The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol. Cell. 10: 1033–1043, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00708-6.Search in Google Scholar

Hooft, R.W., Vriend, G., Sander, C., and Abola, E.E. (1996). Errors in protein structures. Nature 381: 272, https://doi.org/10.1038/381272a0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hoyer, W., Grönwall, C., Jonsson, A., Ståhl, S., and Härd, T. (2008). Stabilization of a β-hairpin in monomeric Alzheimer’s amyloid-β peptide inhibits amyloid formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105: 5099–5104, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0711731105.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kabsch, W. and Sander, C. (1983). Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22: 2577–2637, https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.360221211.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kollmer, M., Close, W., Funk, L., Rasmussen, J., Bsoul, A., Schierhorn, A., Schmidt, M., Sigurdson, C.J., Jucker, M., and Fändrich, M. (2019). Cryo-EM structure and polymorphism of Aβ amyloid fibrils purified from Alzheimer’s brain tissue. Nat. Commun. 10: 4760, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12683-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Krissinel, E. and Henrick, K. (2007). Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372: 774–797, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Langer, G., Cohen, S.X., Lamzin, V.S., and Perrakis, A. (2008). Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat. Protoc. 3: 1171–1179, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.91.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Laskowski, R.A., MacArthur, M.W., Mos, D.S., and Thornton, J.M. (1993). PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26: 283–291, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889892009944.Search in Google Scholar

Madsen, D. and Kleywegt, G.J. (2002). Interactive motif and fold recognition in protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 35: 137–139, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0021889802000602.Search in Google Scholar

Morgan, D. (2011). Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Intern. Med. 269: 54–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02315.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Murshudov, G.N., Vagin, A.A., and Dodson, E.J. (1997). Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53: 240–255, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0907444996012255.Search in Google Scholar

Rauth, S., Hinz, D., Börger, M., Uhrig, M., Mayhaus, M., Riemenschneider, M., and Skerra, A. (2016). High-affinity anticalins with aggregation-blocking activity directed against the Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide. Biochem. J. 473: 1563–1578, https://doi.org/10.1042/bcj20160114.Search in Google Scholar

Renders, L., Budde, K., Rosenberger, C., van Swelm, R., Swinkels, D., Dellanna, F., Feuerer, W., Wen, M., Erley, C., Bader, B., et al.. (2019). First-in-human phase I studies of PRS-080#22, a hepcidin antagonist, in healthy volunteers and patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis. PLoS One 14: e0212023, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212023.Search in Google Scholar

Richter, A., Eggenstein, E., and Skerra, A. (2014). Anticalins: exploiting a non-Ig scaffold with hypervariable loops for the engineering of binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 588: 213–218, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.006.Search in Google Scholar

Romier, C., Dominguez, R., Lahm, A., Dahl, O., and Suck, D. (1998). Recognition of single-stranded DNA by nuclease P1: high resolution crystal structures of complexes with substrate analogs. Proteins 32: 414–424, https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980901)32:4<414::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-g.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(19980901)32:4<414::AID-PROT2>3.0.CO;2-GSearch in Google Scholar

Rothe, C. and Skerra, A. (2018). Anticalin® proteins as therapeutic agents in human diseases. BioDrugs 32: 233–243, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-018-0278-1.Search in Google Scholar

Schiefner, A. and Skerra, A. (2015). The menagerie of human lipocalins: a natural protein scaffold for molecular recognition of physiological compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 48: 976–985, https://doi.org/10.1021/ar5003973.Search in Google Scholar

Schmidt, T.G. and Skerra, A. (2007). The Strep-tag system for one-step purification and high-affinity detection or capturing of proteins. Nat. Protoc. 2: 1528–1535, https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.209.Search in Google Scholar

Selkoe, D.J. (2021). Treatments for Alzheimer’s disease emerge. Science 373: 624–626, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi6401.Search in Google Scholar

Skerra, A. (2000). Lipocalins as a scaffold. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1482: 337–350, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00145-x.Search in Google Scholar

Tanzi, R.E. and Bertram, L. (2005). Twenty years of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell 120: 545–555, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008.Search in Google Scholar

Terwilliger, T.C. (2000). Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56: 965–972, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0907444900005072.Search in Google Scholar

Watt, A.D., Crespi, G.A., Down, R.A., Ascher, D.B., Gunn, A., Perez, K.A., McLean, C.A., Villemagne, V.L., Parker, M.W., Barnham, K.J., et al.. (2014). Do current therapeutic anti-Abeta antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease engage the target? Acta Neuropathol. 127: 803–810, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-014-1290-2.Search in Google Scholar

Weichenberger, C.X. and Sippl, M.J. (2007). NQ-Flipper: recognition and correction of erroneous asparagine and glutamine side-chain rotamers in protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 35: W403–W406, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm263.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, C.J., Headd, J.J., Moriarty, N.W., Prisant, M.G., Videau, L.L., Deis, L.N., Verma, V., Keedy, D.A., Hintze, B.J., Chen, V.B., et al.. (2018). MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27: 293–315, https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3330.Search in Google Scholar

Wilmot, C.M. and Thornton, J.M. (1988). Analysis and prediction of the different types of β-turn in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 203: 221–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(88)90103-9.Search in Google Scholar

Wilson, A. (1950). Largest likely values for the reliability index. Acta Crystallogr. 3: 397–398, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0365110x50001129.Search in Google Scholar

Winn, M.D., Ballard, C.C., Cowtan, K.D., Dodson, E.J., Emsley, P., Evans, P.R., Keegan, R.M., Krissinel, E.B., Leslie, A.G., McCoy, A., et al.. (2011). Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67: 235–242, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0907444910045749.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Zander, H., Reineke, U., Schneider-Mergener, J., and Skerra, A. (2007). Epitope mapping of the neuronal growth inhibitor Nogo-A for the Nogo receptor and the cognate monoclonal antibody IN-1 by means of the SPOT technique. J. Mol. Recognit. 20: 185–196, doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jmr.823.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Zott, B., Simon, M.M., Hong, W., Unger, F., Chen-Engerer, H.-J., Frosch, M.P., Sakmann, B., Walsh, D.M., and Konnerth, A. (2019). A vicious cycle of β amyloid-dependent neuronal hyperactivation. Science 365: 559–565, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay0198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Protein Engineering & Design

- Protein engineering & design: hitting new heights

- Antibody display technologies: selecting the cream of the crop

- In vitro evolution of myc-tag antibodies: in-depth specificity and affinity analysis of Myc1-9E10 and Hyper-Myc

- Prodrug-Activating Chain Exchange (PACE) converts targeted prodrug derivatives to functional bi- or multispecific antibodies

- Trispecific antibodies produced from mAb2 pairs by controlled Fab-arm exchange

- EGFR binding Fc domain-drug conjugates: stable and highly potent cytotoxic molecules mediate selective cell killing

- Modular peptide binders – development of a predictive technology as alternative for reagent antibodies

- Tumor cell lysis and synergistically enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by NKG2D engagement with a bispecific immunoligand targeting the HER2 antigen

- Structural basis of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide recognition by engineered lipocalin proteins with aggregation-blocking activity

- A guide to designing photocontrol in proteins: methods, strategies and applications

- Atomistic insight into the essential binding event of ACE2-derived peptides to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Protein Engineering & Design

- Protein engineering & design: hitting new heights

- Antibody display technologies: selecting the cream of the crop

- In vitro evolution of myc-tag antibodies: in-depth specificity and affinity analysis of Myc1-9E10 and Hyper-Myc

- Prodrug-Activating Chain Exchange (PACE) converts targeted prodrug derivatives to functional bi- or multispecific antibodies

- Trispecific antibodies produced from mAb2 pairs by controlled Fab-arm exchange

- EGFR binding Fc domain-drug conjugates: stable and highly potent cytotoxic molecules mediate selective cell killing

- Modular peptide binders – development of a predictive technology as alternative for reagent antibodies

- Tumor cell lysis and synergistically enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by NKG2D engagement with a bispecific immunoligand targeting the HER2 antigen

- Structural basis of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide recognition by engineered lipocalin proteins with aggregation-blocking activity

- A guide to designing photocontrol in proteins: methods, strategies and applications

- Atomistic insight into the essential binding event of ACE2-derived peptides to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein