Tumor cell lysis and synergistically enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by NKG2D engagement with a bispecific immunoligand targeting the HER2 antigen

-

Christian Kellner

, Sebastian Lutz

Abstract

Natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) plays an important role in the regulation of natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity in cancer immune surveillance. With the aim of redirecting NK cell cytotoxicity against tumors, the NKG2D ligand UL-16 binding protein 2 (ULBP2) was fused to a single-chain fragment variable (scFv) targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). The resulting bispecific immunoligand ULBP2:HER2-scFv triggered NK cell-mediated killing of HER2-positive breast cancer cells in an antigen-dependent manner and required concomitant interaction with NKG2D and HER2 as revealed in antigen blocking experiments. The immunoligand induced tumor cell lysis dose-dependently and was effective at nanomolar concentrations. Of note, ULBP2:HER2-scFv sensitized tumor cells for antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). In particular, the immunoligand enhanced ADCC by cetuximab, a therapeutic antibody targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) synergistically. No significant improvements were obtained by combining cetuximab and anti-HER2 antibody trastuzumab. In conclusion, dual-dual targeting by combining IgG1 antibodies with antibody constructs targeting another tumor associated antigen and engaging NKG2D as a second NK cell trigger molecule may be promising. Thus, the immunoligand ULBP2:HER2-scFv may represent an attractive biological molecule to promote NK cell cytotoxicity against tumors and to boost ADCC.

Introduction

Exploiting natural killer (NK) cells is a promising approach in cancer immunotherapy. These innate immune cells exert key functions in the host defense against cancer and play an important role in antibody therapy of tumors (Guillerey et al. 2016; Molgora et al. 2021; Scott et al. 2012; Vivier et al. 2011). NK cells are able to distinguish between malignant and normal cells, exhibit spontaneous cytotoxic functions against tumor cells of different entities and are able to eliminate cancer cells by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). In addition, they shape both innate and adaptive immune responses by secretion of a variety of immunoregulatory cytokines (Vivier et al. 2011).

NK cell effector functions are regulated tightly by sets of activating and inhibitory cell surface receptors, which govern NK cell activation, cytotoxicity and cytokine release (Long et al. 2013). In particular, the stimulatory receptor natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D, CD314) plays a pivotal role (Houchins et al. 1991; Lanier 2015; Wu et al. 1999). NKG2D, which also is expressed by CD8-positive T cells, γδ T cells, NK T cells and subsets of CD4-positive T cells, recognizes multiple cellular ligands, which include major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I polypeptide-related sequence A (MICA), MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence B (MICB) as well as UL-16 binding proteins (ULBP) 1–6 in humans (Bauer et al. 1999; Cosman et al. 2001; Lanier 2015). NKG2D ligands function as danger signal molecules that are rarely expressed by healthy tissues but are found frequently on malignant cells from different cancer types. Thus, recognition of NKG2D ligands enables NK cells and other cytotoxic lymphocytes to discriminate between normal and abnormal cells (Pende et al. 2002). The important roles for NKG2D in immunosurveillance of cancer has been supported in various murine tumor models (Lanier 2015). Impressively, in humans, a key function for NKG2D in tumor immune surveillance was suggested by the observation that risk of cancer development depended on haplotypes of the polymorphic NKG2D encoding gene killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily K, member 1 (Hayashi et al. 2006). Beside their functions in immune surveillance, NK cells represent an important effector cell population for therapeutic antibodies in the treatment of cancer. Thus the majority of peripheral blood NK cells expresses the activating low affinity IgG fragment crystallizable (Fc) receptor III A (FcγRIIIA) and are able to kill antibody-coated target cells by ADCC, a major effector function of therapeutic tumor targeting antibodies (Guillerey et al. 2016; Kellner et al. 2017; Perussia et al. 1983; Ravetch and Perussia 1989; Vivier et al. 2011). A relevant contribution of NK cells in antibody therapy in patients has been suggested by clinical observations, which have indicated that FcγRIIIA engagement is crucial for different therapeutic antibodies (Bibeau et al. 2009; Cartron et al. 2002; Musolino et al. 2008; Weng and Levy 2003). More directly, a role of NK cells has been revealed by a positive correlation between therapeutic responses to anti-disialoganglioside 2 antibody therapy and the presence of unlicensed NK cells lacking inhibitory killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) reactive to self-human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules in neuroblastoma patients (Tarek et al. 2012).

Regarding the important functions of NK cells, promoting their engagement may represent a promising strategy to further enhance the efficacy of antibody therapy of cancer. Interestingly, expression of NKG2D ligands was found to sensitize tumor cells for NK cell-mediated ADCC, suggesting that co-engagement of this receptor with agonistic antibodies may enhance tumor cell elimination. In previous approaches to activate NKG2D in an antigen dependent manner, bispecific antibodies and immunoligands have been generated (Chan et al. 2018; Rothe et al. 2014). For effector cell recruitment, bispecific antibodies combine antibody-derived binding sites for two different antigens in one single molecule, one for target cell recognition and one for effector cell recruitment and activation (Brinkmann and Kontermann 2017). Most advanced is the marketed bispecific antibody blinatumomab, a bispecific T cell engager, which consists of two single chain fragments variable (scFv) that bind CD19 on malignant B cells and the T cell trigger molecule CD3, respectively (Bargou et al. 2008). Recombinant immunoligands typically also use a scFv for target cell binding but contain a ligand for an activating or co-stimulatory surface receptor for effector cell engagement, which substitutes the second antibody derived binding site found in the prototypic bispecific antibody format (Vyas et al. 2014). Similar to bispecific antibodies, recombinant immunoligands are able to cross-link tumor target antigens and trigger receptors on effector cells, and thereby promote cell-mediated cytotoxicity. For NKG2D engagement, bispecific immunoligands have been designed by fusing various tumor cell-directed scFv to UL-16 binding protein 2 (ULBP2) or MICA (Kellner et al. 2012a; Stamova et al. 2011; von Strandmann et al. 2006). In particular, fusion proteins consisting of a CD20 scFv and the NKG2D ligand ULBP2 triggered NK cells to kill lymphoma cells and enhanced ADCC by therapeutic CD20 or CD38 antibodies (Kellner et al. 2012a, 2016). Most recently, therapeutic efficacy of a bispecific antibody targeting CS1 and NKG2D has been shown in xenograft models of multiple myeloma (Chan et al. 2018).

Here, for enhanced NK cell activation, the NKG2D ligand ULBP2 was fused to a scFv targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), a proto-oncogene product and validated target antigen that is expressed on a variety of solid tumors, and the cytotoxic profile of this novel bifunctional immunoligand was analysed either alone or in combination with therapeutic IgG1 antibodies.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The human breast adenocarcinoma cell lines SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-361 (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in McCoy’s 5a medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 20% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 units/mL penicillin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 20% FCS, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, respectively. Ramos cells (German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell cultures, DSMZ; Braunschweig, Germany) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Lenti-X 293T cells (Takara Bio Europe/Clontech) were kept in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Immunoligands, antibodies and fusion proteins

An expression vector for the immunoligand ULBP2:HER2-scFv was constructed by cloning the DNA sequences encoding either the anti-HER2 scFv derived from antibody humAb4D5-8 (Carter et al. 1992; Glorius et al. 2013) into vector pSecTag2/ULBP2:7D8-myc-his using SfiI restriction sites (Kellner et al. 2012a). The construct for expression of the control immunoligand was generated by replacing the sequence for the anti-HER2 scFv by those encoding a CD37 scFv (Grosmaire et al. 2007) . For expression, vectors were transfected into Lenti-X 293T cells by calcium-phosphate transfection and purified by affinity chromatography using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose beads (Qiagen) according to published procedures (Kellner et al. 2012b). Concentrations of purified immunoligands were determined by quantitative capillary electrophoresis using Experion™ Pro260 technology (BioRad) according the manufacturer’s instructions or estimated against a standard curve of bovine serum albumin.

Therapeutic antibodies trastuzumab, rituximab (both from Roche Pharma AG) and cetuximab (Merck) were purchased. NKG2D-Fc and NKp30-Fc, consisting of the extracellular domains of NKG2D and NKp30, respectively, and the human IgG1 Fc domain, were expressed and purified as described previously (Kellner et al. 2012a,b). The anti-HER2 tribody – a fusion protein between two anti-HER2 scFv and a CD89 Fab fragment (unpublished) – and a control tribody, in which the two anti-HER2 scFv were replaced by two anti-EGFR scFv (unpublished) were produced as described for other tribody molecules previously (Glorius et al. 2013). The murine IgG1 anti-NKG2D antibody (clone 149810) and the corresponding isotype control were obtained from R&D Systems.

SDS-PAGE, western blotting and gel filtration chromatography

SDS-PAGE and Western transfer experiments were performed by standard procedures (Kellner et al. 2012b). ULBP2:HER2-scFv was detected with mouse anti-penta-His (Qiagen) and secondary horse radish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Dianova). Gel filtration chromatography was performed on an ÄKTA purifier (GE Healthcare) using Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) as described (Peipp et al. 2015). Data were analyzed with Unicorn 5.1 software (GE Healthcare).

Deglycosylation of the immunoligands

Immunoligands were deglycosylated under denaturing reaction conditions using Protein Deglycosylation Mix (New England Bio Labs) containing the enzymes O-glycosidase, PNGase F, neuraminidase, β1-4 galactosidase and β-N-acetylglucosaminidase according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For Western blotting, 1.5 µg of proteins were loaded onto a gel.

Homology modeling

Homology models for the HER2-specific scFv derived from antibody humAb4D5-8 and ULBP2 were calculated using YASARA Structure software (YASARA Biosciences). Secretion leader sequences and tags were not included. Structures for whole molecules were then generated by introducing linker sequences and fusing the best-fitting models obtained for the single subunits. Ribbon drawings were generated using Discovery Studio 2.0 Visualize software (Accelrys Inc.).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on a Navios flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) as described previously (Kellner et al. 2012b). To analyze specific binding, ULBP2:HER2-scFv or the control immunoligand were employed at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. An Alexa Fluor 488-coupled anti-penta His secondary antibody (Qiagen) was used for detection. To analyze simultaneous antigen binding abilities, SK-BR-3 cells were incubated with the immunoligands at 50 μg/mL and then reacted with NKG2D-Fc (100 μg/mL), which was subsequently detected with polyclonal FITC-coupled anti-human IgG F(ab′)2 fragments (Beckman Coulter). Cell surface ULBP2 was analyzed with a PE-conjugated anti-ULBP-2/5/6 (clone 165903; R&D Systems) antibody. A recommended corresponding isotype antibody was used as a control.

Preparation of MNC and isolation of NK cells

Experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Christian-Albrechts-University (Kiel, Germany) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood was drawn after receiving the donors’ written informed consent. MNC were prepared from peripheral blood or leukocyte reduction system chambers according to published procedures (Repp et al. 2011). NK cells were purified from MNC by negative selection using MACS technology and NK cell isolation kit (Miltenyi) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified NK cells were cultured over-night at a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 Glutamax-I medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was analyzed in standard 3 h 51Cr release experiments performed in 96-well microtiter plates in a total volume of 200 µL as described previously (Repp et al. 2011). Human MNC or NK cells were used as effector cells at the indicated effector-to-target (E:T) cell ratios. All experiments were repeated with effector cells from multiple donors and performed in triplicate determinations.

Real-time cell analysis

A real-time cell analyzer (xCELLigence, ACEA) was applied to monitor the activity of antibody constructs over time as described (Kute et al. 2009; Oberg et al. 2014; Seidel et al. 2014). Briefly, 50 µL medium was added to 96-well micro-E-plates to equilibrate the system. Thereafter, 5000 adherent SK-BR-3 cells in 50 µL were added per well. Electronic sensors located at the bottom of the plates monitored the cell impedance. After reaching the linear growth time phase, both MNC (E:T cell ratio: 50:1) and antibody constructs were applied, and the final volume was adjusted to 200 µL. As controls, cells were incubated in the absence of MNC and antibody constructs or treated with Triton X-100 for determination of basal impedance (max). Employing xCELLigence technology electric impedance was determined as cell index values and monitored every 5 min. MNC from different donors were analyzed in triplicate determinations for all treatment groups.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Graphical and statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. P-values were calculated employing two-tailed student’s t-test or repeated measures ANOVA and the Bonferroni post-test when appropriate. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Combination index (CI) values were calculated with CalcuSyn software (Biosoft Ferguson, USA) according to the method of Chou and Talalay (Chou and Talalay 1984) using the formula CI x = DA/D xA + DB/D xB, where D xA and D xB indicate doses of drug A and drug B alone producing x% effect, and DA and DB indicate doses of drugs A and B in combination producing the same effect.

Results

Generation of ULBP2:HER2-scFv and binding abilities

For targeted NKG2D activation, the NKG2D ligand ULBP2 was genetically fused to a HER2-specific scFv derived from the humanized HER2-specific antibody trastuzumab (Carter et al. 1992). The recombinant immunoligand, designated ULBP2:HER2-scFv (Figure 1A, B) was expressed in eukaryotic cells and purified from cell culture supernatants by affinity chromatography. The fusion protein was detected in elution fractions by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western-Blot experiments (Figure 1C, D). Enzymatic deglycosylation and subsequent Western blot analysis suggested that the protein was weakly glycosylated (Figure 1D). Size exclusion chromatography revealed homogeneity of the protein preparations (Figure 1E).

Design and purification of ULBP2:HER2-scFv.

(A) For construction, the sequence encoding amino acids 1–210 of ULBP2, which span the secretion leader (S) and MHC class I-like α 1 and 2 domains (UniProtKB – Q9BZM5), were fused to sequences for a humanized anti-HER2 scFv derived from the antibody trastuzumab (CMV, cytomegalovirus immediate early promotor; L, linker sequences; VL, VH, variable regions of immunoglobulin light and heavy chains; M, H, sequences encoding a hexa histidine and a c-myc tag, respectively). (B) A ribbon drawing of ULBP2:HER2-scFv was obtained according to a homology model. ULBP2 α 1–2 domains are colored in dark and light green, respectively. VH and VL regions are depicted in red and orange, respectively. Yellow stained domains indicate antibody complementarity determining regions. (C) Integrity of purified ULBP2:HER2-scFv expressed by Lenti-X 293T cells was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (E1, E2, consecutive elution fractions 1 and 2, respectively). (D) Purified ULBP2:HER2-scFv was left untreated (lane 1), subjected to enzymatic deglycosylation (lane 2) or incubated with deglycosylation buffer only (lane 3) and analyzed by western blot experiments under reducing conditions using an anti-penta histidine antibody. (E) Purified ULBP2:HER2-scFv was subjected to size exclusion chromatography to remove any remaining contaminants or higher molecular mass aggregates (black dashed graph). Corresponding fractions were collected, combined and re-analyzed (red graph).

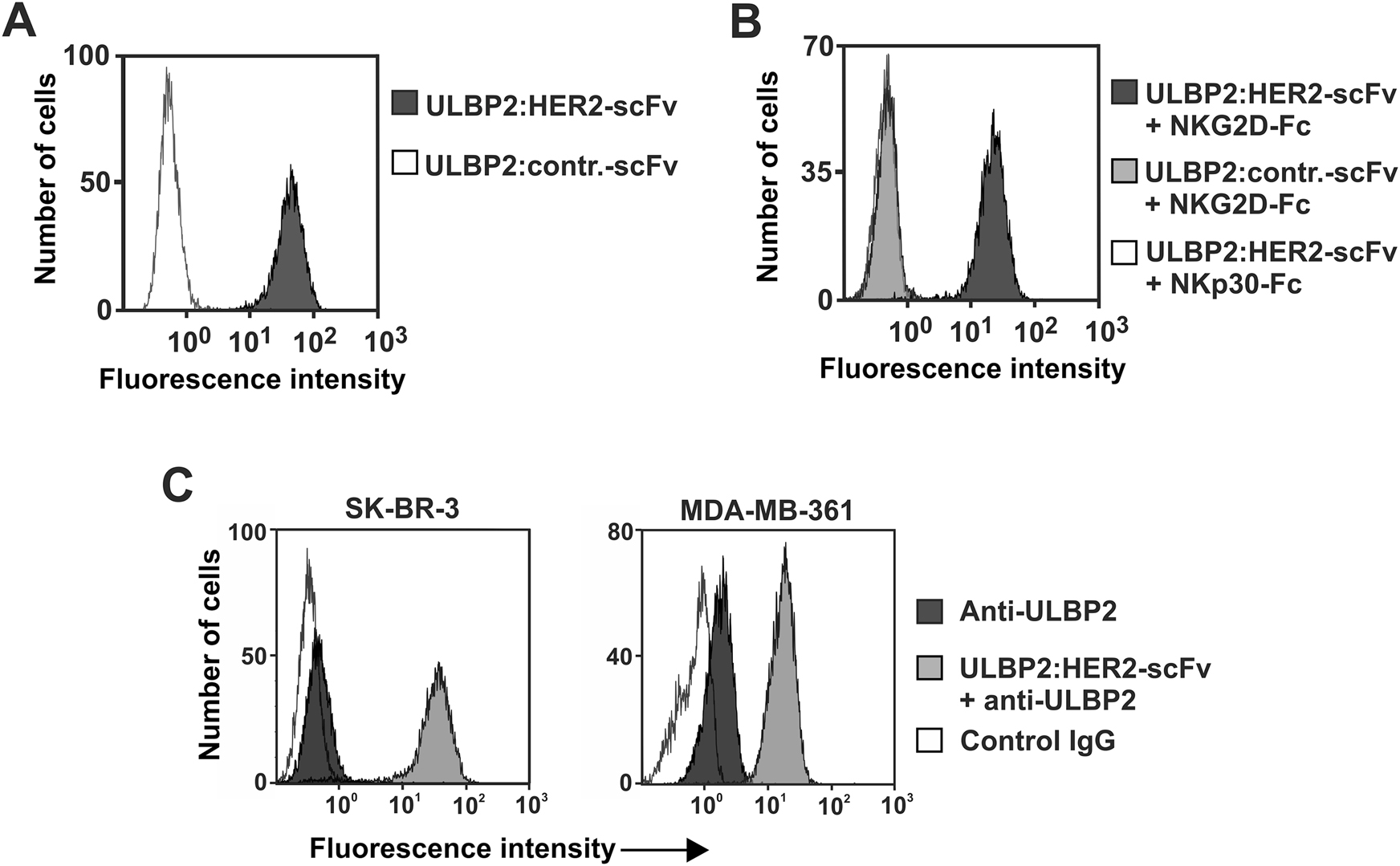

The purified immunoligand bound to HER2-positive SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells (Figure 2A) but did not react with HER2-negative Raji lymphoma cells (data not shown). However, direct binding to NK cells could not be detected by flow cytometry (data not shown), probably because the monovalent immunoligand ULBP2:HER2-scFv had low affinity for NKG2D, in agreement with previous results obtained with other immunoligands (Kellner et al. 2012a,b). Therefore, to verify specific interaction with NKG2D, SK-BR-3 cells first were pre-incubated with the immunoligand, and then incubated with a fusion protein consisting of the extracellular domain of NKG2D and the human IgG1 Fc domain (NKG2D-Fc; Figure 2B). As a result, NKG2D-Fc strongly reacted with ULBP2:HER2-scFv bound by SK-BR-3 cells, whereas no fluorescence signals were obtained with a similar constructed Fc fusion protein containing the extracellular domain of NKp30. Moreover, pre-incubation of SK-BR-3 cells with a similarly constructed control immunoligand also containing ULBP2 but a scFv specific for CD37, which is not expressed by SK-BR-3 cells, did not result in fluorescence signals (Figure 2B). Thus, soluble bivalent NKG2D was bound by ULBP2:HER2-scFv, which notably was able to bind HER2 and NKG2D simultaneously. Finally, expression analysis of endogenous ligands revealed that ULBP2 was expressed by the breast cancer derived cell lines SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-361, but surface levels of the ULBP2 were significantly augmented by pre-incubation of tumor cells with ULBP2:HER2-scFv (Figure 2C).

Binding abilities of ULBP2:HER2-scFv.

(A) Binding of ULBP2:HER2-scFv to HER2-positive SK-BR-3 cells was analyzed employing secondary anti-penta-histidine antibodies. (B) To demonstrate NKG2D reactivity and simultaneous antigen binding, SK-BR-3 cells were first incubated with ULBP2:HER2-scFv, then treated with a fusion protein consisting of the extracellular domain of NKG2D and the human IgG Fc domain (NKG2D-Fc), which finally was detected by antibodies specific for the human Fc portion. An immunoligand against CD37 (ULBP2-contr.-scFv) and a fusion protein of the extracellular domain of NKp30 and human Fc (NKp30-Fc) were applied in control reactions. (C) SK-BR-3 (left) or MDA-MB-361 (right) cells were either left untreated or pre-incubated with ULBP2:HER2-scFv and then stained with a PE-conjugated anti-ULBP2 antibody or an isotype control.

ULBP2:HER2-scFv induces NK cell cytotoxicity

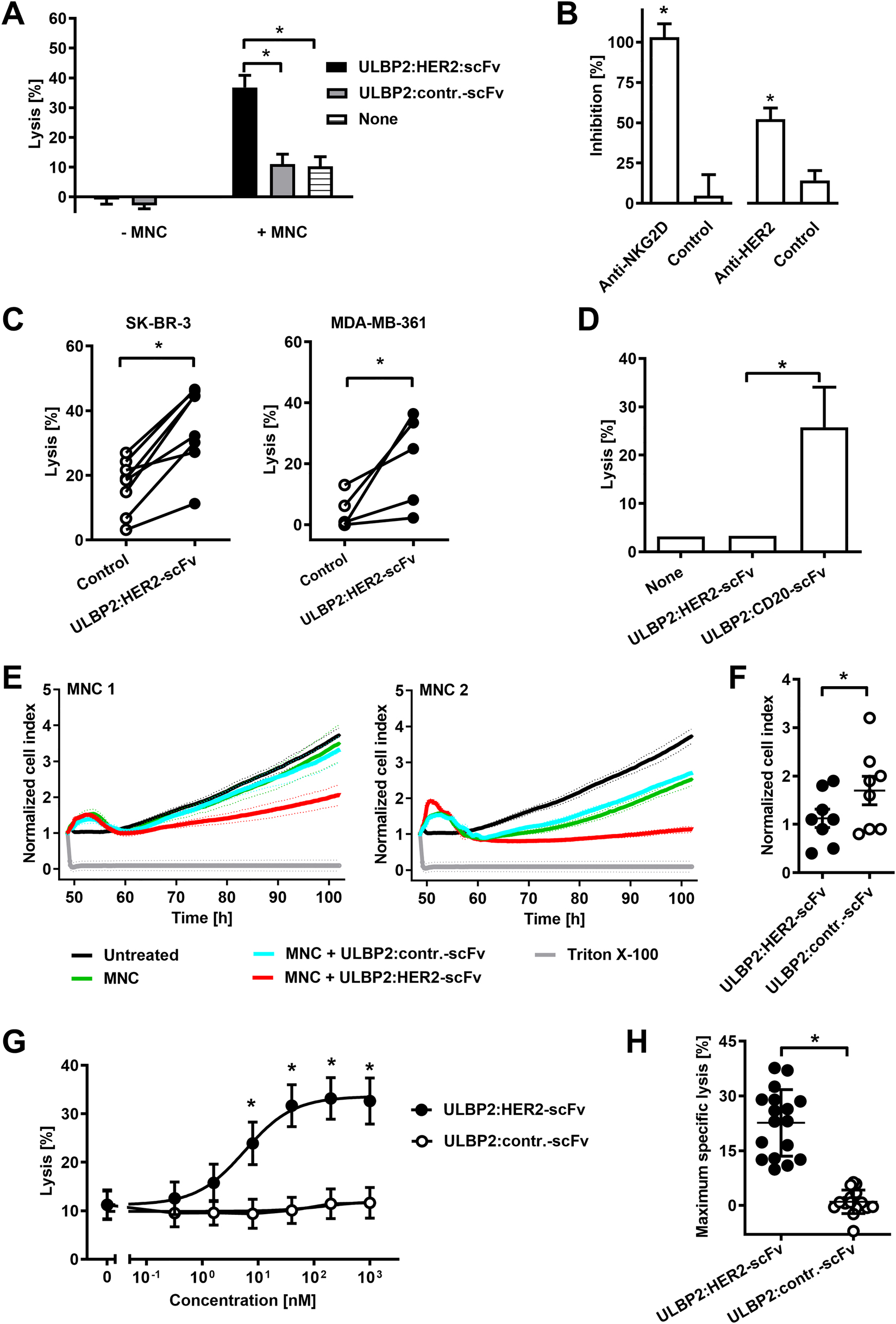

To analyze whether ULBP2:HER2-scFv was able to trigger NK cell cytotoxicity 51Cr release experiments were performed (Figure 3A). In the presence of human mononuclear cells (MNC) as a source of NK cells, ULBP2:HER2-scFv mediated killing of SK-BR-3 cells. In contrast, no killing of tumor cells by ULBP2:HER2-scFv was observed in the absence of effector cells, indicating that effector cell-mediated cytotoxicity was the underlying killing mechanism (Figure 3A). The antigen specific induction of target cell lysis was further confirmed in blocking experiments (Figure 3B). Thus, induction of tumor cell lysis was inhibited significantly when either NKG2D was blocked with a specific murine antibody or when HER2 was masked with a specific Fc-less tribody. Therefore, ULBP2:HER2-scFv required the interaction with both antigens to trigger cytotoxicity. To confirm reactivity with NK cells, human NK cells were purified and analyzed as effector cells for ULBP2:HER2-scFv (Figure 3C). Again, the immunoligand triggered lysis of HER-2 expressing SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-361 target cells efficiently, demonstrating that NK cells were indeed the relevant effector cell population for ULBP2:HER2-scFv. To verify the antigen specific mode of action further, HER2-negative Ramos lymphoma cells were analyzed as target cells for ULBP2:HER2-scFv. Of note, ULBP2:HER2-scFv was not effective, while cells were efficiently killed by a similar constructed control immunoligand targeting the CD20 antigen being expressed by Ramos cells (Figure 3D).

ULBP2:HER2-scFv triggers NK cell cytotoxicity.

(A) Cytotoxicity of ULBP2:HER2-scFv in the presence or absence of MNC. Target cells were SK-BR-3, the E:T cell ratio was 80:1. Data points indicate mean values of five independent experiments with MNC from five different donors (*P < 0.05). (B) Blockade of NKG2D or HER2 inhibits killing of SK-BR-3 cells by ULBP2:HER2-scFv and MNC. E:T cell ratio was 80:1. For blocking, a NKG2D-specific antibody or a HER2-specific tribody were employed. As controls, a non-relevant isotype-matched antibody or an EGFR-specific tribody were used. MNC from six (NKG2D blockade) or five different donors (HER2 blockade) were analyzed in independent experiments (*P < 0.05). (C) Cytotoxicity of ULBP2:HER2-scFv against SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-361 cells employing purified NK cells (E:T cell ratio: 10:1). The immunoligand was applied at a concentration of 200 nM (*P < 0.05). In independent experiments NK cells from seven (SK-BR-3) or four different donors (MDA-MB-361) were analyzed (*P < 0.05). (D) ULBP2:HER2-scFv (concentration: 200 nM) does not mediate killing of HER2-negative Ramos cells. ULBP2:CD20-scFv was used as a positive control. NK cells from four different donors were applied as effector cells in independent experiments (E:T cell ratio: 10:1; *P < 0.05). (E) For real-time monitoring, SK-BR-3 cells were cultured on an E-plate before addition of MNC and the immunoligands ULBP2:HER2-scFv or ULBP2:contr.-scFv at 10 μg/mL. The E:T cell ratio was 50:1. The cell index was determined every 5 min over the course of the experiment using xCELLigence real-time cell analysis instrument and normalized to 1 at the time point of addition of MNC and antibody constructs. Mean values ± SD of triplicate determinations are shown. Depicted are two representative experiments using MNC from different healthy donors. (F) Comparison of ULBP2:HER2-scFv and ULBP2:contr.-scFv in real-time cell analysis using MNC from eight different donors as effector cells. Data points indicate cell index values after 50 h from individual experiments, horizontal lines show mean values ± SEM (n = 8; *P < 0.05). (G) Dose-dependent lysis of SK-BR-3 cells by ULBP2:HER2-scFv. MNC from different donors were used as effector cells at an E:T cell ratio of 80:1. Data points represent mean values of 17 independent experiments with MNC from 11 different donors (*P < 0.05). (H) To determine specific maximum extents of lysis, percentage of tumor cell killing in the absence of an immunoligand was subtracted from each data point in the dose response curve. Best-fit values for maximum killing were calculated and plotted for the 17 individual MNC preparations derived from 11 different donors. Data points represent mean values from triplicate determinations, the horizontal lines represent mean percentage of specific lysis ± SD (*P < 0.05).

Moreover, the cytotoxic activity of ULBP2:HER2-scFv was monitored with SK-BR-3 cells over an extended period of time employing the real-time cell analysis assay (Figure 3E, F). SK-BR-3 target cells were seeded and allowed to attach before after 48 h MNC and the immunoligand were added. When applied with MNC effector cells the immunoligand ULBP2:HER2-scFv had substantial activity against SK-BR-3 cells, relative to control reactions containing a control immunoligand or without added immune constructs (Figure 3E, F). ULBP2:HER2-scFv had no effects on tumor cell growth in the absence of effector cells (unpublished data). Taken together, ULBP2:HER2-scFv was active against adherently growing SK-BR-3 cells.

To further analyze cytotoxic efficacy, ULBP2:HER2-scFv was tested at varying concentrations using MNC effector cells from different donors in 51Cr release experiments (Figure 3G). ULBP2:HER2-scFv acted in a dose-dependent manner and mediated tumor cell lysis at nanomolar concentrations. Half-maximum effective concentration (EC50) in the mean was 5 nM (95% confidence interval: 1.0–26.5 nM). Analysis of the extent of maximum lysis revealed that with MNC from individual donors strong cytotoxic effects were induced. However a considerable variation between different donors was observed (Figure 3H).

ULBP2:HER2-scFv enhances ADCC by therapeutic antibodies

Induction of ADCC represents an important mode of action already being described for many other therapeutic antibodies (Scott et al. 2012; Sliwkowski and Mellman 2013). To analyze whether ULBP2:HER2-scFv was able to boost ADCC, the bifunctional immunoligand was combined with trastuzumab and the combination was analyzed with MNC as effector cells and SK-BR-3 cells as targets in cytotoxicity assays (Figure 4). As a result, ULBP2:HER2-scFv sensitized SK-BR-3 cells for trastuzumab-mediated ADCC and enhanced tumor cell lysis synergistically (Figure 4A). Synergy was demonstrated by a calculated combination index (CI) < 1 and a dose reduction index (DRI) > 1 (Table 1) and was further illustrated in isobologram analysis (Figure 4B) and CI-fractional effect blots (Figure 4C). To analyze another antibody as a combination partner for ULBP2:HER2-scFv, cetuximab was employed, targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). The EGFR is co-expressed with HER2 in SK-BR-3 cells (data not shown). In combination with cetuximab, ULBP2:HER2-scFv enhanced ADCC synergistically (Figure 4A–C; Table 1). ADCC however was not enhanced, when the antibodies were combined with a control immunoligand not binding to the target cells, indicating that antigen specific tumor cell binding of the immunoligand was required also in combination (Figure 4A). Notably, synergistic effects were more pronounced, when ULBP2:HER2-scFv was combined with cetuximab compared to experiments performed with trastuzumab, most likely because in this situation the antibody and the immunoligand recognized two different target antigens and did not compete for antigen binding. Interestingly, only negligible improvements were achieved, when cetuximab was combined with trastuzumab, indicating that the additional stimulus achieved by engagement of the NKG2D receptor by ULBP2:HER2-scFv on NK cells was important (Figure 4A–C).

![Figure 4:

ULBP2:HER2-scFv enhances ADCC by therapeutic antibodies synergistically.

(A) Dose-dependent killing of SK-BR-3 cells by combinations of ULBP2:HER2-scFv and trastuzumab (top panel; n = 6) or cetuximab (middle panel, n = 5). As a control, trastuzumab was combined with cetuximab (bottom panel, n = 3). The indicated “n” denotes the number of different donors analyzed in independent experiments. MNC served as source of effector cells, the E:T cell ratio was 80:1. Statistically significant differences between lysis induced by the combination and either the antibody (#

P < 0.05) or ULBP2:HER2-scFv (*P < 0.05) alone are indicated. CI values < 1 indicating synergy are indicated (+++++, CI < 0.1; ++++, CI < 0.3; +++, CI < 0.7). (B) Analysis of synergy by isobolograms. The experimentally determined doses resulting in 20% (ED20) or 30% (ED30) target cell lysis were compared with the calculated doses which were expected, if additive effects were assumed (CI = 1). (C) CI values at varying fractional effects. Actual combination data points (open circles) represent mean values of at least four independent experiments [black line, computer simulated CI values; dashed grey line, SD; dashed black line, line of additivity (CI = 1)].](/document/doi/10.1515/hsz-2021-0229/asset/graphic/j_hsz-2021-0229_fig_004.jpg)

ULBP2:HER2-scFv enhances ADCC by therapeutic antibodies synergistically.

(A) Dose-dependent killing of SK-BR-3 cells by combinations of ULBP2:HER2-scFv and trastuzumab (top panel; n = 6) or cetuximab (middle panel, n = 5). As a control, trastuzumab was combined with cetuximab (bottom panel, n = 3). The indicated “n” denotes the number of different donors analyzed in independent experiments. MNC served as source of effector cells, the E:T cell ratio was 80:1. Statistically significant differences between lysis induced by the combination and either the antibody (# P < 0.05) or ULBP2:HER2-scFv (*P < 0.05) alone are indicated. CI values < 1 indicating synergy are indicated (+++++, CI < 0.1; ++++, CI < 0.3; +++, CI < 0.7). (B) Analysis of synergy by isobolograms. The experimentally determined doses resulting in 20% (ED20) or 30% (ED30) target cell lysis were compared with the calculated doses which were expected, if additive effects were assumed (CI = 1). (C) CI values at varying fractional effects. Actual combination data points (open circles) represent mean values of at least four independent experiments [black line, computer simulated CI values; dashed grey line, SD; dashed black line, line of additivity (CI = 1)].

Computer simulated CI and DRI values for combinations of ULBP2:HER2-scFv and cetuximab or trastuzumab.

| Combination | Ratio | CI values at lysis of | DRI values at lysis of | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 30% | 40% | 20% | 30% | 40% | ||

| ULBP2:HER2-scFv + cetuximab | 1000:1 | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 4.9 | 12.8 | 28.3 |

| 4.1 | 20.1 | 74.5 | |||||

| ULBP2:HER2-scFv + trastuzumab | 200:1 | 0.81 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 9.1 | 39.1 | 129.3 |

| 1.4 | 2.5 | 4.0 | |||||

| Trastuzumab + cetuximab | 5:1 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| 3.5 | 6.7 | 12.2 | |||||

-

Combination index (CI) and dose reduction index (DRI) values were calculated from 51Cr release experiments with SK-BR-3 cells and MNC for three different effect levels by computer simulation employing CalcuSyn software. Upper and lower DRI values correspond to ULBP2:HER2-scFv, cetuximab and trastuzumab, respectively.

Discussion

A bispecific immunoligand, ULBP2:HER2-scFv, was generated by fusing a humanized HER2-specific scFv with ULBP2 to promote cytotoxic activities of NK cells against tumor cells by NKG2D engagement. ULBP2:HER2-scFv simultaneously bound to HER2 and NKG2D and triggered NK cells to kill HER2-expressing tumor cells in the nanomolar concentration range. Impressively, ULBP2:HER2-scFv synergistically enhanced ADCC by therapeutic antibodies trastuzumab and cetuximab.

Previously, we have demonstrated that HER2-specific immunoligands containing activation-induced C-type lectin and B7 homolog 6 for engagement of NKp80 and NKp30, respectively, were capable of inducing NK cell cytotoxicity (Peipp et al. 2015). Here, we show that the human NKG2D ligand ULBP2 targeted to HER2 triggers NK-cell mediated lysis of tumor cells. ULBP2:HER2-scFv had a lower efficacy than the corresponding humanized IgG1 antibody trastuzumab, whose variable heavy and light chain regions were employed for construction of the immunoligand and which mediated ADCC at picomolar concentrations. This in part may be due to different binding abilities exerted by the immunoligand and the antibody. Thus, ULBP2:HER2-scFv contains, in contrast to the bivalent IgG1 antibody, only a monovalent HER2 binding site. An improvement of the cytotoxic activities of the immune construct could possibly be achieved by a second tumor targeting scFv and thus by a gain in avidity, as it has been demonstrated in the backbone of CD16 engaging bispecific antibody constructs and NKG2D-directed immunoligands (Kellner et al. 2008; Vyas et al. 2016). Moreover, for other immunoligands containing ULBP2 a higher cytotoxic activity was achieved by designing multimeric variants (Jachimowicz et al. 2011). In addition, different receptor characteristics may also account for these observations. For example, NKG2D is expressed at 10 to 20-fold lower levels than FcγRIIIA by NK cells (Peipp et al. 2015). Also, the strength of the activation signal delivered by NKG2D may be lower as a consequence of the differing signaling adaptor molecules. Thus, NKG2D is associated with DNAX-activation protein 10 in contrast to FcγRIIIA, which is coupled to the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) containing adapter molecules CD3 ζ or FcεRI γ chains (Long et al. 2013; Wu et al. 1999), and signaling via the ITAM containing adapter molecules may be more efficient in inducing NK cell cytotoxicity. Whether the use of bispecific NKG2D antibodies (Chan et al. 2018; Raynaud et al. 2020), which may exert enhanced affinity to the NKG2D receptor, may more efficiently elicit the NKG2D signaling cascade and further improve NK cell activation, remains to be determined.

Current attempts to promote NK cell ADCC include strategies that aim to strengthen the interaction with FcγRIIIA, for example by applying antibody Fc engineering technologies or using bispecific antibodies (Brinkmann and Kontermann 2017; Kellner et al. 2017; Oberg et al. 2018). In addition, antibody combination approaches, in which either inhibitory immune checkpoint receptors are blocked or co-stimulatory receptors are engaged, appear attractive (Minetto et al. 2019). For example, NK cell activities were promoted by combining the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab with an agonistic antibody to the stimulatory CD137 antigen or with an antibody directed to the inhibitory natural killer group 2 member A immune checkpoint receptor (Andre et al. 2018; Kohrt et al. 2014). Here, we provide further evidence that combination of monoclonal antibodies with NKG2D-specific immunoligands may offer an additional opportunity further enhancing ADCC. It would be interesting to see, if ULBP2:HER2-scFv is also capable of further enhancing cytotoxicity of bispecific antibodies engaging Fcγ receptors such as the tribody [(HER2)2 × CD16], for which we previously have observed an enhanced cytotoxic potency relative to trastuzumab (Oberg et al. 2018).

Furthermore, simultaneous targeting of two different antigens such as HER2 and EGFR may enhance specificity in antibody therapy, offering the opportunity of selectively recruiting the immune cells to double-positive tumor cells, whereas single-positive healthy cells are spared. In addition, such approaches may reduce the risk of tumor immune escape by modulation of the target antigen. Of note, whereas ADCC was enhanced by combination of cetuximab with ULBP2:HER2-scFv, ADCC was not improved when cetuximab was combined with trastuzumab. This is in accordance with published observations indicating that in contrast to complement-dependent cytotoxicity, ADCC is difficult to enhance by combination of two different IgG1 antibodies (Dechant et al. 2008; Kellner et al. 2012a; Klitgaard et al. 2013). These data suggest that when simultaneous targeting of two different tumor-associated antigens is desired, an IgG1 antibody may be combined with an immunoconstruct engaging instead of FcγRIIIA a different activating NK cell receptor such as NKG2D. By such dual-dual targeting approaches concomitant engagement of two distinct tumor-associated antigens can be combined with co-engagement of two distinct NK cell trigger molecules and, thus, synergistically promote tumor cell lysis. EGFR and HER2, which in this study have been chosen as model antigens and are co-expressed on certain breast cancers and other solid tumors, may represent potential target antigens for such an approach (Rimawi et al. 2010).

In this study, ULBP2:HER2-scFv was analyzed with NK cells. In humans, NKG2D is also expressed by conventional CD8-positive T cells, subsets of CD4-positive T cells, γδ T cells and NKT cells (Prajapati et al. 2018). Experiments in mice demonstrated that ectopically expressed or antibody-delivered NKG2D ligands triggered T cell tumor immunity in mice (Cho et al. 2010; Diefenbach et al. 2001). Previously, CD20-directed immunoligands containing either MICA or ULBP2 were found to activate ex vivo expanded γδ T cells for lymphoma cell lysis (Peipp et al. 2017). Although an activation of peripheral blood T cells was not observed in vitro with these immunoligands, a CD33-directed ULBP2 immunoligand was shown to induce cytokine release by αβ T cells (Kellner et al. 2012a; Peipp et al. 2017). Whether such immunoligands may also promote cytotoxicity by human conventional T cells still remains to be investigated.

In conclusion, the immunoligand ULBP2:HER2-scFv may represent an attractive antibody-derived biological molecule to promote NK cell cytotoxicity against tumors. Enhanced NK cell cytotoxicity may be achieved by dual-dual targeting by combining an IgG1 antibody with another antibody construct targeting a second tumor-associated antigen and engaging NKG2D as a second NK cell lysis receptor in addition to FcγRIIIA. Thus, the proposed concept may represent an interesting strategy to improve further the efficacy of antibody therapy of cancer by strengthening the important ADCC effector function. To translate this approach to clinical application probably further engineering of the described prototype molecule will be necessary.

Funding source: Deutsche Krebshilfe http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/501100005972

Funding source: Wilhelm Sander-Stiftung http://dx.doi.org/10.13039/100008672

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2014.134.1

Acknowledgments

We thank Anja Muskulus, Daniela Hallack and Britta von Below for expert technical assistance.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This study was supported by intramural funding from the Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel (to C.K.) and research grant 2014.134.1 by the Wilhelm Sander Foundation (to C.K. and M.P.) and the German Cancer Aid (Mildred-Scheel-Professorship program to M.P.).

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Andre, P., Denis, C., Soulas, C., Bourbon-Caillet, C., Lopez, J., Arnoux, T., Blery, M., Bonnafous, C., Gauthier, L., Morel, A., et al.. (2018). Anti-NKG2A mAb is a checkpoint inhibitor that promotes anti-tumor immunity by unleashing both T and NK cells. Cell 175: 1731–1743.e13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.014.Search in Google Scholar

Bargou, R., Leo, E., Zugmaier, G., Klinger, M., Goebeler, M., Knop, S., Noppeney, R., Viardot, A., Hess, G., Schuler, M., et al.. (2008). Tumor regression in cancer patients by very low doses of a T cell-engaging antibody. Science 321: 974–977, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158545.Search in Google Scholar

Bauer, S., Groh, V., Wu, J., Steinle, A., Phillips, J.H., Lanier, L.L., and Spies, T. (1999). Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science 285: 727–729, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5428.727.Search in Google Scholar

Bibeau, F., Lopez-Crapez, E., Di Fiore, F., Thezenas, S., Ychou, M., Blanchard, F., Lamy, A., Penault-Llorca, F., Frebourg, T., Michel, P., et al.. (2009). Impact of FcγRIIa-FcγRIIIa polymorphisms and KRAS mutations on the clinical outcome of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab plus irinotecan. J. Clin. Oncol. 27: 1122–1129, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.18.0463.Search in Google Scholar

Brinkmann, U. and Kontermann, R.E. (2017). The making of bispecific antibodies. MAbs 9: 182–212, https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2016.1268307.Search in Google Scholar

Carter, P., Presta, L., Gorman, C.M., Ridgway, J.B., Henner, D., Wong, W.L., Rowland, A.M., Kotts, C., Carver, M.E., and Shepard, H.M. (1992). Humanization of an anti-p185HER2 antibody for human cancer therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89: 4285–4289, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.10.4285.Search in Google Scholar

Cartron, G., Dacheux, L., Salles, G., Solal-Celigny, P., Bardos, P., Colombat, P., and Watier, H. (2002). Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcγRIIIa gene. Blood 99: 754–758, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v99.3.754.Search in Google Scholar

Chan, W.K., Kang, S., Youssef, Y., Glankler, E.N., Barrett, E.R., Carter, A.M., Ahmed, E.H., Prasad, A., Chen, L., Zhang, J., et al.. (2018). A CS1-NKG2D bispecific antibody collectively activates cytolytic immune cells against multiple myeloma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 6: 776–787, https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.cir-17-0649.Search in Google Scholar

Cho, H.M., Rosenblatt, J.D., Tolba, K., Shin, S.J., Shin, D.S., Calfa, C., Zhang, Y., and Shin, S.U. (2010). Delivery of NKG2D ligand using an anti-HER2 antibody-NKG2D ligand fusion protein results in an enhanced innate and adaptive antitumor response. Cancer Res. 70: 10121–10130, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-10-1047.Search in Google Scholar

Chou, T.C. and Talalay, P. (1984). Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 22: 27–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4.Search in Google Scholar

Cosman, D., Mullberg, J., Sutherland, C.L., Chin, W., Armitage, R., Fanslow, W., Kubin, M., and Chalupny, N.J. (2001). ULBPs, novel MHC class I-related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity 14: 123–133, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00095-4.Search in Google Scholar

Dechant, M., Weisner, W., Berger, S., Peipp, M., Beyer, T., Schneider-Merck, T., Lammerts van Bueren, J.J., Bleeker, W.K., Parren, P.W., van de Winkel, J.G., et al.. (2008). Complement-dependent tumor cell lysis triggered by combinations of epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies. Cancer Res. 68: 4998–5003, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-07-6226.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Diefenbach, A., Jensen, E.R., Jamieson, A.M., and Raulet, D.H. (2001). Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumour immunity. Nature 413: 165–171, https://doi.org/10.1038/35093109.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Glorius, P., Baerenwaldt, A., Kellner, C., Staudinger, M., Dechant, M., Stauch, M., Beurskens, F.J., Parren, P.W., Winkel, J.G., Valerius, T., et al.. (2013). The novel tribody [(CD20)(2)xCD16] efficiently triggers effector cell-mediated lysis of malignant B cells. Leukemia 27: 190–201, https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2012.150.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Grosmaire, L.S., Hayden-Ledbetter, M.S., Ledbetter, J.A., Thompson, P.A., Simon, S.A., and Brady, W. (2007). B-Cell reduction using CD37-specific and CD20-specific binding molecules. WO 2007/014278.Search in Google Scholar

Guillerey, C., Huntington, N.D., and Smyth, M.J. (2016). Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 17: 1025–1036, https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3518.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Hayashi, T., Imai, K., Morishita, Y., Hayashi, I., Kusunoki, Y., and Nakachi, K. (2006). Identification of the NKG2D haplotypes associated with natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral blood lymphocytes and cancer immunosurveillance. Cancer Res. 66: 563–570, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-2776.Search in Google Scholar

Houchins, J.P., Yabe, T., McSherry, C., and Bach, F.H. (1991). DNA sequence analysis of NKG2, a family of related cDNA clones encoding type II integral membrane proteins on human natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 173: 1017–1020, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.173.4.1017.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Jachimowicz, R.D., Fracasso, G., Yazaki, P.J., Power, B.E., Borchmann, P., Engert, A., Hansen, H.P., Reiners, K.S., Marie, M., von Strandmann, E.P., et al.. (2011). Induction of in vitro and in vivo NK cell cytotoxicity using high-avidity immunoligands targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen in prostate carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Therapeut. 10: 1036–1045, https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.mct-10-1093.Search in Google Scholar

Kellner, C., Bruenke, J., Stieglmaier, J., Schwemmlein, M., Schwenkert, M., Singer, H., Mentz, K., Peipp, M., Lang, P., Oduncu, F., et al.. (2008). A novel CD19-directed recombinant bispecific antibody derivative with enhanced immune effector functions for human leukemic cells. J. Immunother. 31: 871–884, https://doi.org/10.1097/cji.0b013e318186c8b4.Search in Google Scholar

Kellner, C., Gunther, A., Humpe, A., Repp, R., Klausz, K., Derer, S., Valerius, T., Ritgen, M., Bruggemann, M., van de Winkel, J.G.J., et al.. (2016). Enhancing natural killer cell-mediated lysis of lymphoma cells by combining therapeutic antibodies with CD20-specific immunoligands engaging NKG2D or NKp30. Oncoimmunology 5: e1058459, https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2015.1058459.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kellner, C., Hallack, D., Glorius, P., Staudinger, M., Mohseni Nodehi, S., de Weers, M., van de Winkel, J.G.J., Parren, P.W.H.I., Stauch, M., Valerius, T., et al.. (2012a). Fusion proteins between ligands for NKG2D and CD20-directed single-chain variable fragments sensitize lymphoma cells for natural killer cell-mediated lysis and enhance antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Leukemia 26: 830–834, https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.288.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kellner, C., Maurer, T., Hallack, D., Repp, R., van de Winkel, J.G.J., Parren, P.W.H.I., Valerius, T., Humpe, A., Gramatzki, M., and Peipp, M. (2012b). Mimicking an induced self phenotype by coating lymphomas with the NKp30 ligand B7-H6 promotes NK cell cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 189: 5037–5046, https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1201321.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kellner, C., Otte, A., Cappuzzello, E., Klausz, K., and Peipp, M. (2017). Modulating cytotoxic effector functions by Fc engineering to improve cancer therapy. Transfus. Med. Hemotherapy 44: 327–336, https://doi.org/10.1159/000479980.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Klitgaard, J.L., Koefoed, K., Geisler, C., Gadeberg, O.V., Frank, D.A., Petersen, J., Jurlander, J., and Pedersen, M.W. (2013). Combination of two anti-CD5 monoclonal antibodies synergistically induces complement-dependent cytotoxicity of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells. Br. J. Haematol. 163: 182–193, https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12503.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Kohrt, H.E., Colevas, A.D., Houot, R., Weiskopf, K., Goldstein, M.J., Lund, P., Mueller, A., Sagiv-Barfi, I., Marabelle, A., Lira, R., et al.. (2014). Targeting CD137 enhances the efficacy of cetuximab. J. Clin. Invest. 124: 2668–2682, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci73014.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kute, T.E., Savage, L., Stehle, J.R.Jr., Kim-Shapiro, J.W., Blanks, M.J., Wood, J., and Vaughn, J.P. (2009). Breast tumor cells isolated from in vitro resistance to trastuzumab remain sensitive to trastuzumab anti-tumor effects in vivo and to ADCC killing. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 58: 1887–1896, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-009-0700-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lanier, L.L. (2015). NKG2D Receptor and its ligands in host defense. Cancer Immunol. Res. 3: 575–582, https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.cir-15-0098.Search in Google Scholar

Long, E.O., Kim, H.S., Liu, D., Peterson, M.E., and Rajagopalan, S. (2013). Controlling natural killer cell responses: integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31: 227–258, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075005.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Minetto, P., Guolo, F., Pesce, S., Greppi, M., Obino, V., Ferretti, E., Sivori, S., Genova, C., Lemoli, R.M., and Marcenaro, E. (2019). Harnessing NK cells for cancer treatment. Front. Immunol. 10: 2836, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02836.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Molgora, M., Cortez, V.S., and Colonna, M. (2021). Killing the invaders: NK cell impact in tumors and anti-tumor therapy. Cancers 13: 595, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040595.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Musolino, A., Naldi, N., Bortesi, B., Pezzuolo, D., Capelletti, M., Missale, G., Laccabue, D., Zerbini, A., Camisa, R., Bisagni, G., et al.. (2008). Immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms and clinical efficacy of trastuzumab-based therapy in patients with HER-2/neu-positive metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 26: 1789–1796, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.14.8957.Search in Google Scholar

Oberg, H.H., Kellner, C., Gonnermann, D., Sebens, S., Bauerschlag, D., Gramatzki, M., Kabelitz, D., Peipp, M., and Wesch, D. (2018). Tribody [(HER2)2 × CD16] is more effective than trastuzumab in enhancing γδ T cell and natural killer cell cytotoxicity against HER2-expressing cancer cells. Front. Immunol. 9: 814, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00814.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Oberg, H.H., Peipp, M., Kellner, C., Sebens, S., Krause, S., Petrick, D., Adam-Klages, S., Rocken, C., Becker, T., Vogel, I., et al.. (2014). Novel bispecific antibodies increase gammadelta T-cell cytotoxicity against pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 74: 1349–1360, https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-13-0675.Search in Google Scholar

Peipp, M., Derer, S., Lohse, S., Staudinger, M., Klausz, K., Valerius, T., Gramatzki, M., and Kellner, C. (2015). HER2-specific immunoligands engaging NKp30 or NKp80 trigger NK-cell-mediated lysis of tumor cells and enhance antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Oncotarget 6: 32075–32088, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.5135.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Peipp, M., Wesch, D., Oberg, H.H., Lutz, S., Muskulus, A., van de Winkel, J.G.J., Parren, P.W.H.I., Burger, R., Humpe, A., Kabelitz, D., et al.. (2017). CD20-specific immunoligands engaging NKG2D enhance γδ T cell-mediated lysis of lymphoma cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 86: 196–206, https://doi.org/10.1111/sji.12581.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Pende, D., Rivera, P., Marcenaro, S., Chang, C.C., Biassoni, R., Conte, R., Kubin, M., Cosman, D., Ferrone, S., Moretta, L., et al.. (2002). Major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain A and UL16-binding protein expression on tumor cell lines of different histotypes: analysis of tumor susceptibility to NKG2D-dependent natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 62: 6178–6186.Search in Google Scholar

Perussia, B., Acuto, O., Terhorst, C., Faust, J., Lazarus, R., Fanning, V., and Trinchieri, G. (1983). Human natural killer cells analyzed by B73.1, a monoclonal antibody blocking Fc receptor functions. II. Studies of B73.1 antibody-antigen interaction on the lymphocyte membrane. J. Immunol. 130: 2142–2148.10.4049/jimmunol.130.5.2142Search in Google Scholar

Prajapati, K., Perez, C., Rojas, L.B.P., Burke, B., and Guevara-Patino, J.A. (2018). Functions of NKG2D in CD8(+) T cells: an opportunity for immunotherapy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 15: 470–479, https://doi.org/10.1038/cmi.2017.161.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Ravetch, J.V. and Perussia, B. (1989). Alternative membrane forms of Fc gamma RIII(CD16) on human natural killer cells and neutrophils. Cell type-specific expression of two genes that differ in single nucleotide substitutions. J. Exp. Med. 170: 481–497, https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.170.2.481.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Raynaud, A., Desrumeaux, K., Vidard, L., Termine, E., Baty, D., Chames, P., Vigne, E., and Kerfelec, B. (2020). Anti-NKG2D single domain-based antibodies for the modulation of anti-tumor immune response. Oncoimmunology 10: 1854529, https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2020.1854529.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Repp, R., Kellner, C., Muskulus, A., Staudinger, M., Nodehi, S.M., Glorius, P., Akramiene, D., Dechant, M., Fey, G.H., van Berkel, P.H., et al.. (2011). Combined Fc-protein- and Fc-glyco-engineering of scFv-Fc fusion proteins synergistically enhances CD16a binding but does not further enhance NK-cell mediated ADCC. J. Immunol. Methods 373: 67–78, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2011.08.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Rimawi, M.F., Shetty, P.B., Weiss, H.L., Schiff, R., Osborne, C.K., Chamness, G.C., and Elledge, R.M. (2010). Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in breast cancer association with biologic phenotype and clinical outcomes. Cancer 116: 1234–1242, https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24816.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Rothe, A., Jachimowicz, R.D., Borchmann, S., Madlener, M., Kessler, J., Reiners, K.S., Sauer, M., Hansen, H.P., Ullrich, R.T., Chatterjee, S., et al.. (2014). The bispecific immunoligand ULBP2-aCEA redirects natural killer cells to tumor cells and reveals potent anti-tumor activity against colon carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 134: 2829–2840, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28609.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Scott, A.M., Wolchok, J.D., and Old, L.J. (2012). Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12: 278–287, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3236.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Seidel, U.J., Vogt, F., Grosse-Hovest, L., Jung, G., Handgretinger, R., and Lang, P. (2014). Gammadelta T cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity with CD19 antibodies assessed by an impedance-based label-free real-time cytotoxicity assay. Front. Immunol. 5: 618, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00618.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sliwkowski, M.X. and Mellman, I. (2013). Antibody therapeutics in cancer. Science 341: 1192–1198, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1241145.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Stamova, S., Cartellieri, M., Feldmann, A., Bippes, C.C., Bartsch, H., Wehner, R., Schmitz, M., von Bonin, M., Bornhauser, M., Ehninger, G., et al.. (2011). Simultaneous engagement of the activatory receptors NKG2D and CD3 for retargeting of effector cells to CD33-positive malignant cells. Leukemia 25: 1053–1056, https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.42.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Tarek, N., Le Luduec, J.B., Gallagher, M.M., Zheng, J., Venstrom, J.M., Chamberlain, E., Modak, S., Heller, G., Dupont, B., Cheung, N.K., et al.. (2012). Unlicensed NK cells target neuroblastoma following anti-GD2 antibody treatment. J. Clin. Invest. 122: 3260–3270, https://doi.org/10.1172/jci62749.Search in Google Scholar

Vivier, E., Raulet, D.H., Moretta, A., Caligiuri, M.A., Zitvogel, L., Lanier, L.L., Yokoyama, W.M., and Ugolini, S. (2011). Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science 331: 44–49, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198687.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

von Strandmann, E.P., Hansen, H.P., Reiners, K.S., Schnell, R., Borchmann, P., Merkert, S., Simhadri, V.R., Draube, A., Reiser, M., Purr, I., et al.. (2006). A novel bispecific protein (ULBP2-BB4) targeting the NKG2D receptor on natural killer (NK) cells and CD138 activates NK cells and has potent antitumor activity against human multiple myeloma in vitro and in vivo. Blood 107: 1955–1962, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-05-2177.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Vyas, M., Koehl, U., Hallek, M., and von Strandmann, E.P. (2014). Natural ligands and antibody-based fusion proteins: harnessing the immune system against cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 20: 72–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2013.10.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Vyas, M., Schneider, A.C., Shatnyeva, O., Reiners, K.S., Tawadros, S., Kloess, S., Kohl, U., Hallek, M., Hansen, H.P., and Pogge von Strandmann, E. (2016). Mono- and dual-targeting triplebodies activate natural killer cells and have anti-tumor activity in vitro and in vivo against chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncoimmunology 5: e1211220, https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2016.1211220.Search in Google Scholar

Weng, W.K. and Levy, R. (2003). Two immunoglobulin G fragment C receptor polymorphisms independently predict response to rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 21: 3940–3947, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2003.05.013.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, J., Song, Y., Bakker, A.B., Bauer, S., Spies, T., Lanier, L.L., and Phillips, J.H. (1999). An activating immunoreceptor complex formed by NKG2D and DAP10. Science 285: 730–732, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.285.5428.730.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Protein Engineering & Design

- Protein engineering & design: hitting new heights

- Antibody display technologies: selecting the cream of the crop

- In vitro evolution of myc-tag antibodies: in-depth specificity and affinity analysis of Myc1-9E10 and Hyper-Myc

- Prodrug-Activating Chain Exchange (PACE) converts targeted prodrug derivatives to functional bi- or multispecific antibodies

- Trispecific antibodies produced from mAb2 pairs by controlled Fab-arm exchange

- EGFR binding Fc domain-drug conjugates: stable and highly potent cytotoxic molecules mediate selective cell killing

- Modular peptide binders – development of a predictive technology as alternative for reagent antibodies

- Tumor cell lysis and synergistically enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by NKG2D engagement with a bispecific immunoligand targeting the HER2 antigen

- Structural basis of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide recognition by engineered lipocalin proteins with aggregation-blocking activity

- A guide to designing photocontrol in proteins: methods, strategies and applications

- Atomistic insight into the essential binding event of ACE2-derived peptides to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Highlight: Protein Engineering & Design

- Protein engineering & design: hitting new heights

- Antibody display technologies: selecting the cream of the crop

- In vitro evolution of myc-tag antibodies: in-depth specificity and affinity analysis of Myc1-9E10 and Hyper-Myc

- Prodrug-Activating Chain Exchange (PACE) converts targeted prodrug derivatives to functional bi- or multispecific antibodies

- Trispecific antibodies produced from mAb2 pairs by controlled Fab-arm exchange

- EGFR binding Fc domain-drug conjugates: stable and highly potent cytotoxic molecules mediate selective cell killing

- Modular peptide binders – development of a predictive technology as alternative for reagent antibodies

- Tumor cell lysis and synergistically enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity by NKG2D engagement with a bispecific immunoligand targeting the HER2 antigen

- Structural basis of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptide recognition by engineered lipocalin proteins with aggregation-blocking activity

- A guide to designing photocontrol in proteins: methods, strategies and applications

- Atomistic insight into the essential binding event of ACE2-derived peptides to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein