Associations of serum levels of cGAMP in the context of COVID-19 infection, atherosclerosis, sterile inflammation, and functional endothelial biomarkers in patients with coronary heart disease and healthy volunteers

Abstract

Objectives

The present study evaluated the relationships of the serum levels of the cyclic dinucleotide 2′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) marker of activation of pattern-recognition receptors with immunoglobulin G antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome-linked coronavirus (IgG-SARS)-positive status and endothelial dysfunction.

Methods

Selected groups from two cohorts (cohort 1 of 307 healthy volunteers and cohort 2 of 218 coronary heart disease [CHD] patients). COVID-19 infection was confirmed by detection of IgG-SARS against SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein receptor-binding domain. Cohort 1 was examined for systematic coronary risk evaluation by European Society of Cardiology (SCORE) starting from 2019 before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cohort 2 was processed starting from 2017 (three years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) in a hospital setting to undergo coronary angiography to assess coronary lesions as Gensini score. The levels of cGAMP and endothelial markers (nitrate and nitrite combined as NOx and endothelin-1) were assessed in the serum to evaluate the associations with IgG-SARS status, SCORE, and extent of coronary lesions by correlation and receiver operating characteristic analyses.

Results

Serum cGAMP did not discriminate between SARS-positive and SARS-negative healthy subject of cohort 1. Moreover, the level of cGAMP was not associated with endothelial biomarkers in healthy subjects. However, Serum cGAMP was associated with atherosclerosis, with area under the curve 0.69 (95 % CI 0.587–0.806; p=0.001), and with endothelial markers in cohort 2.

Conclusions

Low cGAMP was associated with atherosclerosis in CHD patients, suggesting that cGAMP is a new biomarker in the context of sterile inflammation.

Introduction

A viral infection may have harmful effects on the cardiac function due to transcriptional and posttranslational modifications that disrupt the gap junctions, influence immune response, or mediate the development of cardiomyopathy [1]. The cyclic dinucleotide 2′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) is considered a marker of pattern-recognition receptor (PRR) activation and sterile inflammation. cGAMP is produced by the cytosolic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) sensor enzyme cGAMP synthase (cGAS) in response to the presence of aberrant dsDNA in the cytoplasm. In general, cytosolic dsDNA is associated with intracellular invasion of DNA viruses or certain bacterial or with cellular DNA damage. cGAMP acts as a second messenger to activate the stimulator of interferon genes (STING), which is the central hub of cytosolic dsDNA sensing, to eventually induce type-I interferon and proinflammatory cytokine responses against infections, cancer, or cellular stress [2].

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is RNA-containing coronavirus, which is the pathogen of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 is not expected to influence the activity of cGAS, accumulation of cGAMP, or activation of STING directly since this virus does not contain dsDNA. However, infection with SARS-CoV-2 is known to trigger autophagy that involves intracellular degradation process to maintain cellular homeostasis and combat the invading pathogen. Autophagy antagonizes interferon production possibly by promoting STING degradation [3]. On the other hand, genetic deletion of STING in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice was shown to reduce atherosclerotic lesions spontaneously developing in these animals [4]. Moreover, a recent study demonstrated direct STING-independent cGAMP-dependent effects of cGAS activation by dsDNA in the endothelium on vascular smooth muscle relaxation [5].

The mechanisms and targets of sterile inflammation in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD) and healthy subjects after COVID-19 are poorly understood. The aim of the present study was to elucidate the associations of serum cGAMP levels with endothelial dysfunction markers and the presence of antibodies against the spike protein receptor-binding domain (S1 RBD) of SARS-CoV2 (IgG-SARS-CoV-2) in apparently healthy subjects with elevated cardiovascular risk assessed by systematic coronary risk evaluation by European Society of Cardiology (SCORE) and in patients with coronary atherosclerosis, which represents the advanced stage of endothelial dysfunction.

Patients and methods

Participants

The study included randomly selected groups of male and female participants 25–80 years of age from two cohorts.

Apparently healthy subjects (cohort 1)

Cohort 1 included healthy volunteers (n=307; 24–69 years of age; 44.8 ± 8.6 years; 80.4 % men) without prior record of cardiovascular diseases or other significant comorbidities. The cohort 1 subjects were volunteers over 18 years of age participating in the microcirculation study that started in 2019 in National Research Center for Preventive Medicine (NRCPM), Moscow, Russia [6]. Evaluation of the participants included assessment of baseline cardiovascular characteristics and biochemical parameters in the blood at the time of the recruitment visit.

The following exclusion criteria were applied: any acute inflammation, including oral or dental inflammation, at the enrollment date; hematological diseases; left ventricular ejection fraction below 40 %; diabetes mellitus; chronic kidney, liver, or heart failure; oncological diseases; mental illness; autoimmune diseases; any blood sugar lowering therapy; any cholesterol-lowering therapy; pregnancy; and lactation. All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in the study. The study protocol was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki and WHO guidelines and was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of NRCPM (number 01-01/17 and 01/01-2019). All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in the study and to grant access to their personal data.

Body weight of the participants was measured at a 0.1 kg precision using an electronic scale (Seca Ltd., Hamburg, Germany). Height was measured using a stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm (Seca Ltd.). The body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the equation: weight/height2 (kg/m2). Cohort 1 participants were examined for preventive counseling and estimation of SCORE according to the European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention [7]. SCORE assessment included gender, age, systolic blood pressure (SBP), total cholesterol, and use of tobacco.

Patients with CHD (cohort 2)

Cohort 2 included 218 patients (63 ± 10.9 years of age; 54 % men) treated at NRCPM as described previously [8]. Eligible patients were over 25 years of age and signed an informed consent for inclusion in the study and the collection and biobanking of the blood. Inclusion criteria were as follows: over 18 years of age, signed an informed consent, and underwent coronary angiography. All patients of cohort 2 had clear indications for coronary angiography performed by the method of Judkins [9] according to current European Society of Cardiology guidelines [10], 11] by using Philips Integris Allura Cath Lab and the GE Innova 4100 IQimaging system (General Electric, Fairfield, CT, USA). Stenosis was quantified using the Advantage Workstation software version 4.4 (General Electric). Indications for angiography included positive exercise test, positive stress echocardiography, symptoms of advanced angina pectoris, arrhythmia, pathological changes in electrocardiogram with physical inability to perform exercise or stress tests, or high Duke score.

Exclusion criteria for cohort 2 were as follows: myocardial infarction within 6 months of admission; any acute inflammatory disease; chronic kidney failure stage III and higher with rate of glomerular filtration below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2; decompensated diabetes mellitus type I or type II with levels of glycated hemoglobin over 7.5 %; left ventricular ejection fraction below 40 %; any oncological disease; familial hypercholesterolemia; any hematological disease; and immune and autoimmune diseases. Additional details have been provided in our previous publications [11], 12].

Blood pressure and heart rate were measured as described previously [12]. The patients were examined, diagnosed, stratified, and treated from 2011 to 2016 according to the National Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of stable angina [13]. The study complied with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies. Study protocols have been approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of NRCPM (approval no. 09-05/19) according to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and WHO. All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in the study and to grant access to their personal data.

Blood sampling

Blood was withdrawn from the cubital vein after 12–14 h fasting on the date of the visit at the baseline of the study. The serum was obtained by centrifugation at 1,000 g for 15 min at 4 °С. Apparently healthy asymptomatic individuals (cohort 1) were specifically asked to limit smoking and consumption of high nitrate-containing foods for at least 24 h prior to their visit to the hospital. Patients were asked to specifically abstain from consumption of high NOx products prior to withdrawal of blood for NOx assay. Low NOx diet was low on fruits and vegetables (especially green leaf salads) and rich in grains, meat, and dairy. All kinds of processed meat (hotdogs, bacon, sausage, and similar products) were strictly forbidden [14]. Patients of cohort 2 suspected of having CHD were admitted to the hospital at least 24 h prior to blood sampling and were fed a controlled hospital diet that limits consumption of dietary nitrate. Serum was aliquoted and stored at −26 °C.

Endothelial biomarkers

The endothelin/NOx ratio was used as a surrogate marker of balance between vasodilatory and vasoconstrictor mediators. Concentrations of nitrite and nitrate (NOx) were assayed in the serum deproteinized by filtration through Spin-X UF-5000 molecular weight cutoff concentrators (Corning, UK) as described previously [15]. Nitrate was reduced to nitrite with vanadium (III) chloride (Sigma, USA), and NOx levels were measured by the Griess reaction as described [15], 16] with modifications (CV<9 %). Endothelin-1 was measured using an ELISA kit (Affymetrix Bioscience, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Linear range of the assay was from 0.5 to 10 fmol/mL (CV<5 %).

Detection of cGAMP

cGAMP was measured in serum samples (n=168 and n=88) randomly selected from cohorts 1 and 2, respectively, by competitive ELISA using commercial ELISA kits (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer instructions.

Detection of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S1 RBD

Immunoassay for qualitative detection of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S1 RBD (IgG-SARS) was performed using an anti-SARS-CoV-2 ELISA E111-IVD kit (Mediagnost, Germany) by two-step ELISA with recombinant SARS-CoV-2-S1 RBD according to the manufacturer instructions as described by us previously [6]. Deionized water (Aquasmart, Russia) was used to dissolve the reagents. The samples were considered antibody-positive at >5-fold cut-off value or if the optical density was higher than 0.830. The samples with <3-fold cut-off value were considered antibody-negative. Samples from 3-fold to 5-fold cut-off or with the intermediate optical density values were considered borderline positive. The cut-off values were selected to ensure the exclusion of false positive results with a high probability. The assay was characterized by 95.55 % sensitivity, 98.36 % specificity, and 10.6 % inter-assay variance [17].

Routine blood tests

Routine tests were performed in NRCPM using specific guidelines approved by Center for External Quality Control of Clinical Laboratory Testing of Russian Federation (www.fsvok.ru, accessed on September 10, 2021). Clinical blood tests were performed on an MEK-8222 K automatic hematology analyzer (Nihon Kohden, Saitama, Japan). Serum lipids were assayed as described previously [18]. In brief, serum levels of total cholesterol (mmol/L), high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol (mmol/L) after precipitation of apoB-containing low density lipoproteins (LDL), and triglycerides (mmol/L) were assayed using an Architect c8000 autoanalyzer and reagents from Abbot Diagnostics, Lake Forest, Illinois, USA. The level of LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) was calculated according to the Friedwald equation in the samples with serum triglycerides below 4.5 mmol/L. C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/L) was assayed by high sensitivity quantitative immunoturbidimetric method enhanced with latex particles (universal range 0.3–350 mg/L; highly sensitive range 0.05–20 mg/L) using an Architect c8000 analyzer and reagents from Abbot Diagnostics. Plasma glucose level (mmol/L) was assayed by the hexokinase method using the same autoanalyzer and reagents from Abbot Diagnostics.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 and Statistica software version 8.0 (StatSoft, Inc., USA). Some clusters of the data did not pass the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality of distribution; therefore, we used non-parametric tests for all calculations. Continuous variables are presented as the median (25 %; 75 %), and categorical variables are presented in percentages. Sample size and power were estimated using the online calculator Sampsize https://sampsize.sourceforge.net/iface/s2.html#nm (accessed on September 10, 2021). Comparisons between the two groups were performed by a post-hoc Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s tests or by Mann–Whitney U test. P values<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The study included a total of 256 men and women randomly selected from two different cohorts to represent various stages of endothelial dysfunction evaluated as elevated SCORE (varied from 0 to 20) in healthy volunteers of cohort 1 [6] or as coronary atherosclerosis evaluated using Gensini score [19] (varied from 0 to 197) in CHD patients of cohort 2 [11], 12]. Patients with higher Gensini score corresponded to advanced clinical stages of endothelial dysfunction. Functional markers, including NOx and endothelin-1, were used as indicators of endothelial dysfunction.

Cohort 1 was enrolled in a microcirculation study in 2019–2021, and the participants were gradually infected with SARS-CoV-2 during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic [6]. All participants of cohort 1 had no complaints for pre-existing cardiovascular diseases, thrombotic events, or other serious comorbidities. General characteristics of the group selected from cohort 1 are listed in Table 1. Clinical and biochemical parameters of these participants varied within the corresponding normal ranges, indicating that the participants were apparently healthy. IgG-SARS antibodies were assayed in the blood samples of cohort 1, and serum cGAMP level was measured in 168 samples of cohort 1. This selected group of cohort 1 (n=168) was divided into two subgroups according to the IgG-SARS status: positive (+) (n=56) or negative (−) (n=112). All tested parameters were compared between these subgroups using Mann-Whitney U test (Table 1). The levels of tested parameters were similar between the subgroups of healthy volunteers with SARS(+) and SARS(−) status, except sex (Table 1).

General and biochemical characteristics of selected groups from cohort 1 of healthy volunteers with variable IgG-SARS status and from cohort 2 of CHD patients.

| Parameters | Healthy volunteers from cohort 1 (n=168) | Patients with CHD from cohort 2 (n=88) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS (−) (n=112) | SARS (+) (n=56) |

p-Value | Coronary stenosis present (n=44) | Coronary stenosis absent (n=44) | p-Value | |

| Sex (men, %) | 82.1 | 50.9 | 0.0001 | 68 | 40 | 0.000 |

|

|

||||||

| Median (25 %; 75 %) | Median (25 %; 75 %) | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Age. (years) | 46.0 (40.0; 51.0) | 47.0 (40.0; 54.0) | 0.73 | 64.5 (57.7; 72.0) | 61.5 (55.0; 70.2) | 0.27 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 (24.1; 30.9) | 25.0 (22.9; 28.2) | 0.31 | 29.5 (26.8; 32.5) | 29.2 (26.5; 31.6) | 0.67 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 122.0 (114.0; 130.0) | 120.0 (112.0; 130.0) | 0.16 | 130.0 (120.0; 140.0) | 130.0 (120.0; 135.0) | 0.23 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 80.0 (77.5; 85.0) | 80.0 (70.0; 90.0) | 0.58 | 72.5 (65.0;80.0) | 71.0 (65.0; 80.0) | 0.77 |

|

|

||||||

| Biochemical markers | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| cGAMP. (fmol/mL) | 52.14 (41.20; 80.21) | 52.34 (40.05; 71.03) | 0.33 | 42.04 (30.01; 50.02) | 50.92 (40.10; 60.21) | 0.005 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.16 (0.53; 1.96) | 1.23 (0.54; 2.42) | 0.65 | 4.08(1.61; 9.37) | 2.71(1.03; 6.00) | 0.04 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3.60 (3.10; 3.80) | 3.40 (2.90; 3.80) | 0.057 | 4.75(4.20; 5.55) | 4.70 (4.00; 5.50) | 0.43 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.50 (4 .90; 6.10) | 5.30 (4.45; 6.25) | 0.32 | 3.70 (3.00; 4.15) | 4.10 (3.70; 4.90) | 0.01 |

| HDL-cholesterol mmol/L) | 1.30 (1.13; 1.58) | 1.40 (1.21; 1.66) | 0.24 | 0.98(0.81; 1.11) | 1.21 (0.96; 1.42) | 0.003 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.35 (2.97; 4.07) | 3.25 (2.68; 3.97) | 0.40 | 2.11(1.56; 2.58) | 2.44 (1.79; 2.92) | 0.06 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.18 (0.86; 1.60) | 1.09 (0.77; 1.57) | 0.45 | 1.34(1.06; 1.81) | 1.43(1.02; 2.02) | 0.71 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 5.70 (5.20; 6.00) | 5.33 (4.90; 6.19) | 0.19 | 6.15(5.67; 7.27) | 5.40 (5.00; 5.85) | 0.001 |

| Endothelin-1 (pg/mL) | 2.10 (1.54; 2.70) | 1.64 (0.48; 2.35) | 0.61 | 1.68 (1.41; 1.85) | 1.86 (1.54; 2.14) | 0.51 |

| NOx (µmol/L) | 24.12(19.04; 34.55) | 23.21 (18.34; 29.73) | 0.32 | 30.00 (24.49; 41.76) | 41.79 (32.14; 58.93) | 0.001 |

-

LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; NOx, total concentrations of nitrate and nitrite. p<0.05 marked with color

The groups selected from cohort 1 and 2 were not balanced in sex or age. Thus, associations of sex and age with various tested parameters were estimated, including serum cGAMP, NOx, and endothelin-1 in combined cohorts 1 and 2. The results indicated the lack of associations with sex and age (data not shown).

Cohort 2 comprised patients with signs of CHD who underwent coronary angiography. The group randomly selected from cohort 2 (n=88) was divided into two equal subgroups according to the severity of coronary stenosis lesions: presence of coronary lesions corresponding to advanced endothelial dysfunction (n=44) and absence of coronary lesions corresponding to moderate endothelial dysfunction (n=44). Various parameters were compared between the two patient subgroups using a post-hoc test for Kruskal-Wallis, the Dunn’s test (Table 1). The levels of routine biomarkers, such as CRP and glucose, were increased in patients with coronary stenosis compared with those in patients without coronary lesions (Table 1). Total and HDL-cholesterol levels were decreased in patients with coronary stenosis compared with those in patients without coronary stenosis apparently because of statin treatment routinely prescribed to patients in the subgroup with coronary lesions.

A total of 145 healthy subjects with low SCORE index (0–1) and SARS(−) status were selected from cohort 1 to represent normal endothelial function, and associations between endothelial markers (endothelin-1 and NOx) with cGAMP were evaluated (Table 2). In these subjects, the levels of cGAMP were not correlated with endothelial markers (Table 2). This subgroup of healthy subjects was expanded by combining with the subgroup of healthy subjects with low SCORE (0–1) and IgG-SARS(+) status (Table 3). In this case, the IgG-SARS-CoV-2 status was correlated with endothelial markers (NOx and endothelin-1) but there were no correlations with cGAMP. Serum endothelin-1 and NOx levels were decreased in IgG-SARS(+) subjects compared with those in IgG-SARS(−) subjects: 1.77 ± 0.96 pg/mL vs. 1.38 ± 1.1 pg/mL (p=0.018) and 30.99 ± 22.98 μmol/L vs. 24.47 ± 12.67 μmol/L (p=0.05), respectively.

Spearmen rank correlations in healthy volunteers (n=144) selected from the cohort 1, with SCORE 0–1 and negative IgG-SARS status.

| Parameter | NOx, µmol/L | Endothelin-1, pg/mL | cGAMP, fmol/mL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOx, µmol/L | r | −0.03 | 0.12 | |

| p | 0.68 | 0.34 | ||

| Endothelin-1, pg/mL | r | −0.03 | 0.19 | |

| p | 0.68 | 0.14 | ||

| cGAMP, fmol/mL | r | 0.12 | 0.19 | |

| p | 0.34 | 0.14 | ||

Spearmen rank correlations in healthy volunteers (n=197) selected from cohort 1, with SCORE 0–1 and positive and negative IgG-SARS status.

| Parameter | NOx, µmol/L | Endothelin-1, pg/mL | cGAMP, pmol/mL | IgG-SARS status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOx, µmol/L | r | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.16a | |

| P | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.01 | ||

| Endothelin-1, pg/mL | r | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.19b | |

| P | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.007 | ||

| cGAMP, fmol/mL | r | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.04 | |

| P | 0.37 | 0.63 | 0.62 | ||

-

ap<0.05; bp<0.001

Thus, COVID-19 was linked to endothelial function, while cGAMP was not involved in these associations in apparently healthy individuals. Additionally, the cGAMP levels were not associated with IgG-SARS status in the group selected from cohort 1 with variable SCORE (Tables 1 and 4). However, serum endothelin-1 was directly correlated with SCORE in subjects with SARS(−) status with r=0.38 (p=0.0001) and in subjects with SARS(+) status with r=0.47 (p=0.0001) (Table 4). The NOx levels were directly correlated with SCORE but only in SARS(+) participants (r=0.43; p=0.001) (Table 4). Thus, higher SCORE was linked to higher levels of endothelin-1 regardless of IgG-SARS status, and only IgG-SASR(+) subjects displayed an association of SCORE with NOx.

Spearmen rank correlations in healthy volunteers of cohort 1, with variable SCORE from 0 to 20 in the SARS (−) and SARS (+) subgroups.

| Parameter | SARS(−) | SARS(+) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cGAMP, pmol/mL | NOx, µmol/L | Endothelin-1, pg/mL | SCORE % | cGAMP, fmol/mL | NOx, µmol/L | Endothelin-1, pg/mL | SCORE % | ||

| cGAMP, fmol/mL | r | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.17 | −0.08 | ||

| P | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.71 | 0.20 | 0.56 | |||

| NOx, µmol/L | r | 0.17 | 0.001 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.16 | 0.43b | ||

| P | 0.06 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 0.22 | 0.001 | |||

| Endothelin-1, pg/mL | r | 0.07 | 0.001 | 0.38a | −0.17 | 0.16 | 0.47a | ||

| P | 0.43 | 0.99 | 0.0001 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.0001 | |||

| SCORE % | r | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.38a | −0.08 | 0.43a | 0.47a | ||

| P | 0.41 | 0.89 | 0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | |||

-

ap<0.001; bp<0.05.

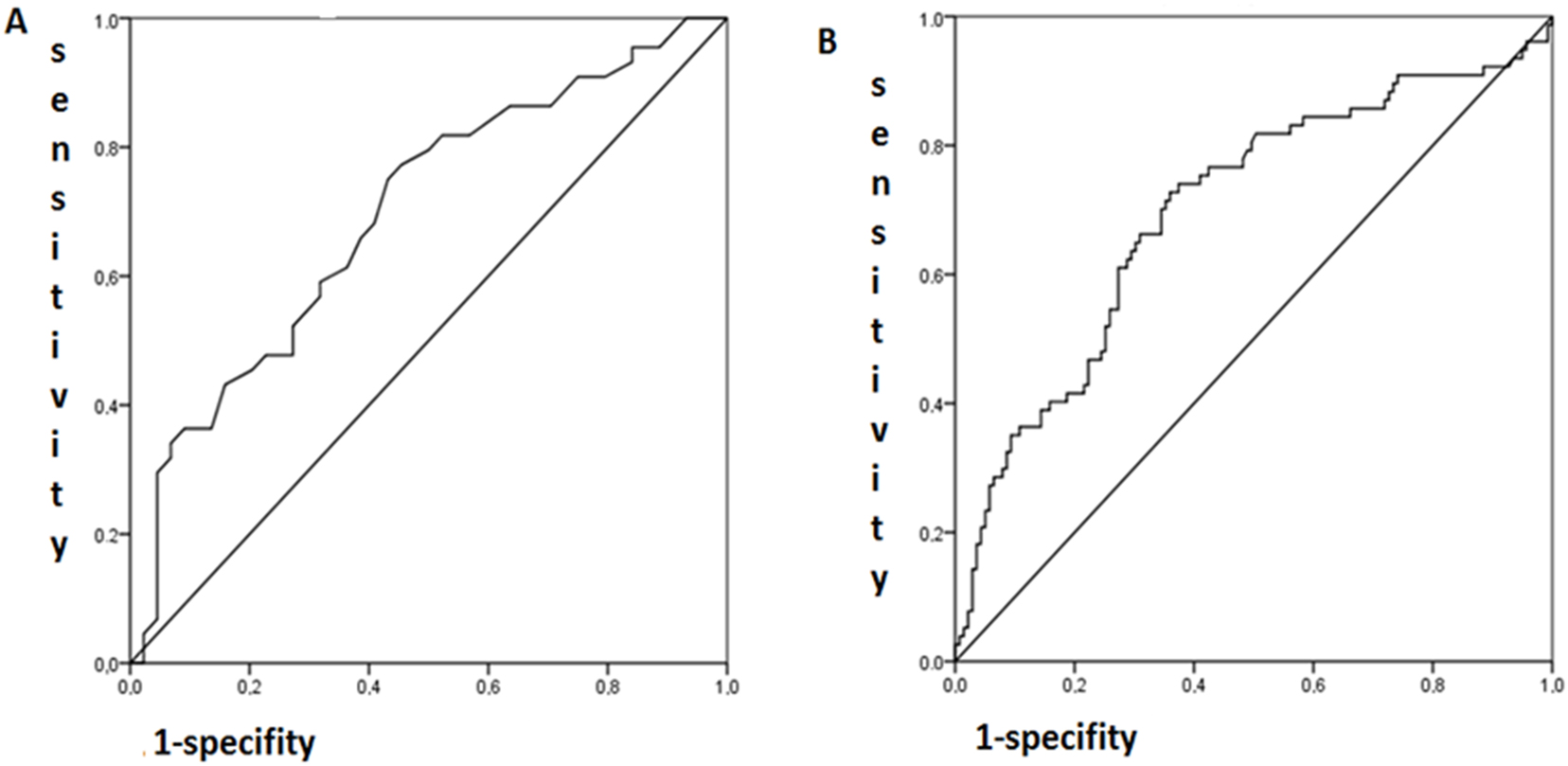

In contrast to cohort 1, serum levels of cGAMP were associated with advanced level of endothelial dysfunction in cohort 2 in patients with atherosclerosis, and cGAMP was lower in patients with coronary stenosis compared with that in patients without coronary stenosis (Table 1). The data of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (AUC=0.69; 95 % CI 0.587–0.806; p=0.001) confirmed the associations between cGAMP, as a continuous variable, with coronary lesions (presence/absence), as a binary variable, in CHD patients of cohort 2 (Figure 1).

ROC analysis of the associations (A) of cGAMP (continuous variable) with coronary lesions (binary variable; 0, without coronary lesions corresponding to Gensini score 0 vs. 1 with any coronary lesions; AUC=0.69; 95 % CI 0.59–0.81; p=0.001) and (B) NOx (continuous variable) with coronary lesions (binary variable; 0, without coronary lesions corresponding to Gensini score 0 vs. 1 with any coronary lesions; AUC=0.69; 95 % CI 0.62–0.77; p=0.0001).

Coronary stenosis expressed as Gensini score (continuous variable) in patients with advanced endothelial dysfunction was inversely correlated with serum NOx levels in CHD patients of cohort 2 (Table 5). This association was confirmed by the data of ROC analysis when coronary lesions were presented as a binary variable (no lesions/stenosis of any degree) and NOx (continuous variable) (AUC=0.69; 95 % CI 0.62–0.77; p=0.0001) (Figure 1). However, serum endothelin-1 was not associated with the presence of coronary lesions in CHD-patients (Table 5).

Spearmen rank correlations for NOx, endothelin-1, and cGAMP with the extent of coronary stenosis evaluated as Gensini score in CHD patients of cohort 2.

| NOx, µmol/L | Endothelin-1, pg/mL | cGAMP, fmol/mL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gensini score | r | −0.24a | −0.06 | −0.28a |

| P | 0.0001 | 0.53 | 0.008 | |

-

ap<0.001.

Advanced endothelial dysfunction in CHD-patients (presence of coronary stenosis) and apparently healthy subjects without endothelial dysfunction with SARS(+) status was associated with lower NOx levels. Higher extent of endothelial dysfunction corresponding to higher SCORE was associated with higher levels of serum NOx and endothelin-1. Healthy subjects with IgG-SARS(−) status demonstrated no correlations of SCORE with NOx or endothelin-1.

Thus, these results demonstrated that cGAMP, as a marker of sterile inflammation, was able to discriminate severe coronary stenosis in CHD-patients and was not associated with early stages of endothelial dysfunction in subjects with elevated SCORE. Moreover, cGAMP was not linked to the IgG SARS(+) and (−) immune status in healthy participants and was not associated with SCORE.

Discussion

Recognition of microbial and viral nucleic acids is a major mechanism of pathogen detection and neutralization by the immune system [20]. SARS-CoV-2 still poses a global threat due to several highly transmissible variants and long COVID-19 [20]. SARS-CoV-2 can trigger autophagy associated with lysosomal degradation of STING that mediates type I interferon production in response to infection. Autophagy is an intracellular degradation process that maintains cellular homeostasis required for efficient defense against pathogens [4].

STING is one of the key mediators of the cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway. cGAS produces cGAMP in response to cytosolic dsDNA to activate innate immune responses mediated by STING [2], 21]. Additionally, the cGAS–cGAMP-STING pathway is able to detect almost any dsDNA that is present in the cytosol as a result of cellular DNA damage in the case of abnormal DNA damage response similar to the processes detected in many tumor cells.

Replication of pathogens inside the cell engages various cytosolic sensors, depending on the pathogen structure. These sensors are known as pattern-recognition receptors. For example, NOD-like receptor (NLR) family is involved in the detection of a variety of microbial toxins and general cellular damage to trigger certain downstream signaling pathways mediated by inflammasomes. Receptors of the RLR family detect viral RNA in the cytosol to trigger a signaling cascade that leads to the production of type I interferons and inflammatory cytokines [2], 22].

SARS-CoV-2 is the member of the Orthocoronavirinae subfamily of RNA-containing coronaviruses, with its genome encoding for 29 nonstructural, structural, and accessory proteins [23]. The data of the present study indicated that serum cGAMP did not discriminate between the SARS(+) and SARS(−) statuses in apparently healthy individuals because SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus that does not influence the cGAS–cGAMP-STING pathway due to the lack of dsDNA. However, cGAMP may be linked to certain signaling pathways regulated by the NLR/RLR systems, which detect the presence of viral RNA in the cytosol [2], 22]. The NLR family pyrin domain-containing three inflammasome is known to be the key mediator in sterile inflammatory responses [24]. On the other hand, endogenous DNA fragments produced in the cytosol due to aberrant DNA damage provoke sterile inflammation through cGAS. Thus, STING has been actively studied in atherogenesis [4]. For example, hypercholesterolemic apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice fed a western-type diet show an increase in STING expression and in markers of DNA damage, such as single-stranded DNA accumulation in macrophages in the aorta. Moreover, the levels of cGAMP, an STING agonist, in the aorta are higher in ApoE−/− mice, and genetic deletion of STING in ApoE−/− mice reduces atherosclerotic lesions and the expression of inflammatory mediators in the aorta. The authors concluded that STING stimulates the activation of proinflammatory macrophages, leading to the development of atherosclerosis, and STING is a potential therapeutic target for atherosclerosis [4]. The data of the present study are generally consistent with these observations because serum cGAMP was able to discriminate between CHD patients with and without coronary lesions.

Inflammation plays an important role in cardiometabolic diseases. Sterile inflammation is a non-infectious innate immune response largely induced by damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) via PRR and is closely associated with the development and progression of various cardiovascular diseases [24]. Thus, we aimed to study the associations between serum cGAMP and endothelial dysfunction that represents one of the initial stages of cardiovascular lesions in atherosclerosis. We used serum NOx and endothelin-1 as surrogate markers of endothelial function. Healthy subjects of cohort 1 with SCORE indexes 0 and 1 were used as the reference. In the present study, associations of serum endothelin-1 or NOx were detected only if SCORE index was elevated in healthy subjects or when the subjects were IgG-SARS positive (Table 4) and in patients with CHD. However, the data indicated that cGAMP was not associated with endothelial function in healthy subjects of cohort 1.

Severe Covid-19 infection may induce specific changes in typical responses of T and B cells manifested as a delay in over-response of T cells, which may contribute to functional exhaustion and premature senescence of T cells. These delays were hypothesized to contribute to pneumonitis and a delay in cytokine secretion. Similar patterns are observed in animal models and patients with STING hyperactivation that can be triggered only by indirect transfer of cGAMP from SARS-CoV-2-infected antigen-presenting cells because normal T cells do not express the main SARS-CoV receptor and are not infected by the virus [25]. However, these data are not particularly relevant to the present study because we did not include patients with current severe Covid-19.

A study in cell culture models demonstrated that infection with high doses of SARS-CoV-2 or fusion of the cells expressing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with the cells expressing its main receptor ACE2 induces an increase in the levels of cytosolic chromatin, which is sensed by the cGAS-STING pathway, thus contributing to an antiviral response. Moreover, an STING activator was able to suppress viral replication in mice infected with the virus. However, these observations have not been extended to Covid-19 in patients [26]. We think that this scenario is not applicable for mild or asymptomatic Covid-19 since the scenario requires massive tissue damage and cell death associated with fusion or release of high amounts of dsDNA. These effects are secondary and are relevant to the cGAMP-STING pathway only in the most severe cases of Covid-19, and these cases have not been included in the present study.

These considerations are supported by a study in patients with long Covid-19 who had fibrotic changes in the lung tissue detected by chest CT scans. Comparison of peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from these patients with those from patients without fibrotic lesions in the lung indicated significant changes in the secretion of interferons. The authors concluded that these changes are not due to the differences in cGAMP signaling but are mediated by another pathway associated with activation of the Absent in melanoma-2 protein [27].

On the other hand, activation of the cGAMP-STING pathway by using cGAMP analogs, which directly stimulate STING, has been shown to provide nonspecific protection against infection by various RNA viruses in cell culture and animal models [28]. These results suggest that the cGAMP-STING pathway may be an important target for the development of antiviral agents with broad specificity to inhibit replication of RNA viruses. Currently, it is not known whether these mechanisms are relevant to actual inflammatory processes in human tissues during or after Covid-19. Nevertheless, these approaches to antiviral therapy are being explored to create nanoparticle-based formulations for control of severe respiratory infections in animal models [29] emphasizing critical roles of the pathway in nonspecific immune response.

Conclusions

Serum cGAMP level was similar in IgG-SARS(+) and IgG-SARS(−) healthy individuals of cohort 1. In contrast, serum levels of cGAMP were decreased in patients with coronary stenosis in cohort 2 compared with that in patients without coronary stenosis. Endothelial dysfunction was associated with cGAMP in CHD patients but endothelial function was not associated with cGAMP in healthy subjects. Thus, low serum cGAMP was associated with coronary stenosis in patients with advanced endothelial dysfunction.

Funding source: Russian Science Foundation

Award Identifier / Grant number: project No. 23-25-00025

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for editing of English to Dr. Alexander Kots.

-

Research ethics: The study protocol was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki and WHO guidelines and was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of NRCPM (number 01-01/17 and 01/01-2019).

-

Informed consent: All participants gave their written informed consent to participate in the study and to grant access to their personal data.

-

Author contributions: N.G. Conceptualization ideas; formulation and evolution of overarching research goals and aims; methodology; development, visualization, preparation, creation and presentation of the published work, specifically data presentation. A.G and N.B. Conducting the patients, data collection, conducting a research and investigation process; creation and presentation of the published work. N.B. Investigation; conducting a research and investigation process, performing the experiments, and data collection, creation and presentation of the published work; visualization. A.G. and N.G. Administration and supervising. N.G. Funding acquisition.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 23-25-00025).

-

Data availability: The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Calhoun, PJ, Phan, AV, Taylor, JD, James, CC, Padget, RL, Zeitz, MJ, et al.. Adenovirus targets transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms to limit gap junction function. FASEB J 2020;34:9694–712. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202000667r.Search in Google Scholar

2. Blest, HTW, Chauveau, L. cGAMP the travelling messenger. Front Immunol 2023;14:1150705. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1150705.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Jiao, P, Fan, W, Ma, X, Lin, R, Zhao, Y, Li, Y, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 6 triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy to degrade STING1. Autophagy 2023;12:3113–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2238579.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Pham, PT, Fukuda, D, Nishimoto, S, Kim-Kaneyama, JR, Lei, XF, Takahashi, Y, et al.. STING, a cytosolic DNA sensor, plays a critical role in atherogenesis: a link between innate immunity and chronic inflammation caused by lifestyle-related diseases. Eur Heart J 2021;42:4336–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab249.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Su, J, Coleman, P, Ntorla, A, Anderson, R, Shattock, MJ, Burgoyne, JR. Sensing cytosolic DNA lowers blood pressure by direct cGAMP-dependent PKGI activation. Circulation 2023;148:1023–34. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065547.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Gumanova, NG, Gorshkov, AU, Bogdanova, NL, Korolev, AI, Drapkina, OM, et al.. Detection of anti-SARS-CoV-2-S1 RBD-specific antibodies prior to and during the pandemic in 2011-2021 and COVID-19 observational study in 2019-2021. Vaccines 2022;10:581. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10040581.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Piepoli, MF, Hoes, AW, Agewall, S, Albus, C, Brotons, C, Catapano, AL, et al.. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the sixth joint task force of the European society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European association for cardiovascular prevention & rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2315–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Zhatkina, M, Metelskaya, V, Gavrilova, N, Yarovaya, E, Makarova, Y, Litinskaya, OA, et al.. Biochemical markers of coronary atherosclerosis: building models and assessing their prognostic value regarding the lesion severity. Russ J Cardiol 2021;26:4559. https://doi.org/10.15829/1560-4071-2021-4559.Search in Google Scholar

9. Judkins, MP. Selective coronary arteriography. I. A percutaneous transfemoral technic. Radiology 1967;89:815–24. https://doi.org/10.1148/89.5.815.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Montalescot, G, Sechtem, U, Achenbach, S, Andreotti, F, Arden, C, Budaj, A, et al.. ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht296.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Metelskaya, V, Zhatkina, M, Gavrilova, N, Yarovaya, E, Bogdanova, N, Kutsenko, V, et al.. Associations of circulating biomarkers with the presence and severity of coronary, carotid and femoral arterial atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Ther Prev 2021;20:3098. (in Russian) https://doi.org/10.15829/1728-8800-2021-3098.Search in Google Scholar

12. Metelskaya, V, Gavrilova, N, Zhatkina, M, Yarovaya, E, Drapkina, O. A novel integrated biomarker for evaluation of risk and severity of coronary atherosclerosis, and its validation. J Pers Med 2022;12:206. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12020206.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Akchurin, RS, Vasyuk, YA, Karpov, YA, Lupanov, VP, Marcevich, SY, Pozdnyakov, YM. National guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of stable angina. Cardiovasc Ther Prev 2009;2009:1. https://doi.org/10.15829/1728-8800-2009-0.Search in Google Scholar

14. Gumanova, NG, Teplova, NV, Ryabchenko, AU, Denisov, EN. Serum nitrate and nitrite levels in patients with hypertension and ischemic stroke depend on diet: a multicenter study. Clin Biochem 2015;48:29–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.10.010.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Gumanova, NG, Klimushina, MV, Metel’skaya, VA. Optimization of single-step assay for circulating nitrite and nitrate ions (NOx) as risk factors of cardiovascular mortality. Bull Exp Biol Med 2018;165:284–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10517-018-4149-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Miranda, KM, Espey, MG, Wink, DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 2001;5:62–71. https://doi.org/10.1006/niox.2000.0319.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Mateus, J, Grifoni, A, Tarke, A, Sidney, J, Ramirez, SI, Dan, JM, et al.. Selective and cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 T cell epitopes in unexposed humans. Science 2020;370:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3871.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Gumanova, NG, Gavrilova, NE, Chernushevich, OI, Kots, AY, Metelskaya, VA. Ratios of leptin to insulin and adiponectin to endothelin are sex-dependently associated with extent of coronary atherosclerosis. Biomarkers 2017;22:239–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354750X.2016.1201539.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Gumanova, NG, Gorshkov, AU, Klimushina, MV, Kots, AY. Associations of endothelial biomarkers, nitric oxide metabolites and endothelin, with blood pressure and coronary lesions depend on cardiovascular risk and sex to mark endothelial dysfunction on the SCORE scale. Horm Mol Biol Clin Invest 2020;41:20200024. https://doi.org/10.1515/hmbci-2020-0024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Chen, Q, Sun, L, Chen, ZJ. Regulation and function of the cGAS-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing. Nat Immunol 2016;17:1142–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3558.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Jiao, P, Fan, W, Ma, X, Lin, R, Zhao, Y, Li, Y, et al.. SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 6 triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy to degrade STING1. Autophagy 2023;12:3113–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2238579.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Ahn, J, Ruiz, P, Barber, GN. Intrinsic self-DNA triggers inflammatory disease dependent on sting. J Immunol 2014;193:4634–42. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1401337.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Yan, W, Zheng, Y, Zeng, X, He, B, Cheng, W. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2: open the door for novel therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022;7:26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00884-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Cho, S, Ying, F, Sweeney, G. Sterile inflammation and the NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiometabolic disease. Biomed J 2023;46:100624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bj.2023.100624.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Berthelot, JM, Lioté, F, Maugars, Y, Sibilia, J. Lymphocyte changes in severe COVID-19: delayed over-activation of STING? Front Immunol 2020;11:607069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.607069.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Zhou, Z, Zhang, X, Lei, X, Xiao, X, Jiao, T, Ma, R, et al.. Sensing of cytoplasmic chromatin by cGAS activates innate immune response in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021;6:382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00800-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

27. Colarusso, C, Terlizzi, M, Maglio, A, Molino, A, Candia, C, Vitale, C, et al.. Activation of the AIM2 receptor in circulating cells of post-COVID-19 patients with signs of lung fibrosis is associated with the release of IL-1α, IFN-α and TGF-β. Front Immunol 2022;13:934264. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.934264.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

28. Garcia, GJ, Irudayam, JI, Jeyachandran, AV, Dubey, S, Chang, C, Castillo, CS, et al.. Innate immune pathway modulator screen identifies STING pathway activation as a strategy to inhibit multiple families of arbo and respiratory viruses. Cell Rep 2023;4:101024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101024.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

29. Leekha, A, Saeedi, A, Kumar, M, Sefat, KMSR, Martinez-Paniagua, M, Meng, H, et al.. An intranasal nanoparticle STING agonist protects against respiratory viruses in animal models. Nat Commun 2024;15:6053. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50234-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Crosstalk between miRNAs and signaling pathways in the development of drug resistance in breast cancer

- Hormonal disorders in autism spectrum disorders

- An overview of the relationship between melatonin and drug resistance in cancers

- Original Articles

- Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): diagnosis using biochemical parameters and anthropometric measurements during the first trimester in the Indian population

- Endothelial cell phenotype is linked to endothelial dysfunction in individuals with a family history of type 2 diabetes

- Associations of serum levels of cGAMP in the context of COVID-19 infection, atherosclerosis, sterile inflammation, and functional endothelial biomarkers in patients with coronary heart disease and healthy volunteers

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Articles

- Crosstalk between miRNAs and signaling pathways in the development of drug resistance in breast cancer

- Hormonal disorders in autism spectrum disorders

- An overview of the relationship between melatonin and drug resistance in cancers

- Original Articles

- Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM): diagnosis using biochemical parameters and anthropometric measurements during the first trimester in the Indian population

- Endothelial cell phenotype is linked to endothelial dysfunction in individuals with a family history of type 2 diabetes

- Associations of serum levels of cGAMP in the context of COVID-19 infection, atherosclerosis, sterile inflammation, and functional endothelial biomarkers in patients with coronary heart disease and healthy volunteers