Abstract

This scoping review explores the complex dynamics of ageism and intergenerational relations within workplace settings, providing insights into how these phenomena shape organizational culture, employee engagement, and workplace inclusivity. Using a systematic search across five databases, we identified 25 studies that examine various aspects of age-based discrimination and generational interactions in the workplace. Key findings suggest that an inclusive intergenerational climate can buffer against ageism, enhance job satisfaction, and improve retention across age groups. The review highlights the compounded challenges faced by older workers, especially older women, suggesting a need for research on gendered ageism and its impact on older female workers. The findings underscore the importance of human resource management (HRM) practices that foster knowledge sharing and mutual respect across generations, aligning with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to gender equality, decent work, and reduced inequalities. Additionally, this review emphasizes the potential of sustainable HRM strategies to dismantle stereotypes, support gender-sensitive policies, and foster a socially responsible workplace that values contributions across all ages. Future research should address regional differences, particularly in Asian and Global South contexts, to better understand how socio-economic factors such as education, job type, and citizenship status influence ageism in diverse workplace settings.

1 Introduction

As global populations age, workforce demographics are changing dramatically. Therefore, diversity in the workforce today not only pertains to gender, ethnicity and culture but also to age (Kapoor and Solomon 2011). In many countries, older workers are being mandated or encouraged to extend their working lives due to pension shortfalls, increasing life expectancy, and government policy aimed at alleviating economic pressures on public pension systems (Carta, D’Amuri, and von Wachter 2021). This trend has resulted in workplaces where younger and older employees are working side by side for longer periods than ever before. Hanks and Icenogle (2001) mention that there will be intergenerational conflicts since younger and older workers often have different values and work styles. But other studies argue that older workers can bring valuable experience and skills, benefiting overall productivity of employees in all ages (Sobrino-De Toro, Labrador-Fernández, and De Nicolás 2019), and Moore, Everly and Bauer (2016) believe that intergenerational collaboration can enhance organizational performance. Consequently, understanding the dynamics between different generations in the workplace is becoming increasingly critical for organizational success and employee well-being.

Intergenerational relations in the workplace, including the interaction between older and younger employees, are shaped by complex factors such as age-related stereotypes (Wang and Shi 2024), communication patterns (Drury and Fasbender 2024), and workplace cultures (Manongcarang and Guimba 2024). According to Peng et al. (2024), ageism, or prejudice against individuals based on their age, diminishes older workers’ voice behaviour (such as sharing ideas, suggestions and/or opinions that are intended to benefit the organization) and limits their engagement in the workplace. This not only impacts the career progression and mental well-being of older employees but also impedes the development of inclusive, dynamic work environments. The study of Takeuhi and Katagiri (2024) found that in Japan 75 % of older workers experiencing ageism in the workplace reported diminished self-perception and subjective well-being. Hegde and Kumar (2024) reveal that in the Indian IT industry ageist attitudes create barriers to intergenerational collaborative and dynamic workplaces. Ageism can manifest in various forms through subtle biases in hiring, promotions, or even interpersonal relationships between workers of different ages (Dennis and Thomas 2007). In addition, gendered ageism at work cannot be ignored. Older women in the workplace and labor market often face more discrimination than older men, for example, being perceived as less competent (McConatha et al. 2023). The intersection of age and gender in steoretypes and discrimination create a toxic work environment that affects well-being of older female workers (McConatha et al. 2023).

Intergenerational dynamics in the workplace refer to the interactions and collaborations among employees from different age groups. Positive intergenerational relations are linked to knowledge sharing, mentorship, and mutual respect (Moore, Everly, and Bauer 2016), while negative interactions can lead to conflict, miscommunication, and entrenched stereotypes (Meshel and McGlynn 2004). Given these evolving dynamics, human resource management (HRM) practices are being scrutinized for their roles in either perpetuating or combating ageism in the workplace (Dennis and Thomas 2007). A sustainable HRM approach focusing on the long-term well-being and development of all employees, irrespective of age, can play a vital role in fostering inclusive work environments (Peng et al. 2024). Based on Kramar (2014), sustainable HRM is defined as the utilization of human resource policies and practices to promote the long-term health and well-being of both the organization and its employees and meanwhile it takes into count the organization’s role within society and its impact on the environment. Sustainable HRM policies and practices that promote continuous learning and knowledge transfer across generations can mitigate ageism and facilitate positive intergenerational interactions (Minbaeva 2007).

This scoping review aims to systematically explore and document the breadth of international literature on ageism and intergenerational relations in the workplace. By investigating existing research, this review seeks to deepen the understanding of how ageist attitudes and intergenerational dynamics shape workplace experiences. Furthermore, it aims to offer strategies for HRM sustainability to promote a more inclusive, multi-generational workforce. The following research questions were posed at the outset of the literature review. First, what does ageism ‘look’ like in the workplace? Second, what patterns are evident in intergenerational relations within workplace settings? And finally, what strategies and practices, particularly from a sustainable HRM and gender pespective, can be employed to combat ageism and improve positive intergeneratioanl dynamics in the workplace?

2 Methodology

To understand the range and nature of research conducted to date on ageism and intergenerational relations in the workplace, a scoping review of the current literature was performed guided by the information retrieval guidelines of the Campbell Collaboration (Kugley et al. 2016). Scoping reviews are a method used to map the existing literature on a broad topic with diverse study designs (Arksey and O’Malley 2005). This approach helps uncover sources, concepts and findings that can inform future research. This scoping review, therefore, followed the five stages of Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) scoping study framework: 1) identifying the research questions; 2) finding relevant studies; 3) selecting studies; 4) charting data; and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results. A comprehensive and replicable search was conducted. Details about the search strategy, study screening and selection, data extraction, coding, and analysis are provided in the following sections.

2.1 Inclusion Criteria

The selected articles had to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) published in peer-reviewed journals; 2) written in English; 3) published between 2007 and 2023; 4) empirical research, reviews or opinion articles (excluding gray literature). To ensure transparency and rigor in the study selection process, the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al. 2018) were followed.

2.2 Search Strategy

There were four steps in the search strategy. To commence, an initial exploratory search, informed by the research teams own existing knowledge of the topic, identified published journal articles within the research area. These articles were then reviewed to identify key concepts and phrases in the literature to inform the development of a comprehensive keyword search string using Boolean operators (Harter 1986) to focus search results. Thirdly, the keyword search string was used to query article titles and abstracts contained in relevant electronic databases. Finally, following screening, the reference lists of included studies were reviewed to locate any additional studies for inclusion.

The terms used were (“worker*” OR “employee” OR “workforce” OR “employment” OR “labor market” OR “labour” OR “job*” OR “work” OR “workplace” OR “work environment”) AND (“ageing” OR “aging” OR “old*” OR “mature” OR “ageism” OR “ageist” OR “age discrimination”) AND (“intergenerational” OR “multigenerational” OR “generational” OR “age diversity” OR “age-diverse” OR “interpersonal” OR “younger worker*” OR “generation*” OR “friendship*” OR “interaction*” OR “interpersonal” “behaviour” OR “behavior” OR “solidarity” OR “dynamic*” OR “conflict” OR “relations” OR “mentor*” OR “difference*” OR “collaboration” OR “gap” OR “exchange”).

Five databases were searched: Web of Science (177 results), ProQuest Social Science Collection (151 results), Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (95 results), PsycINFO (85 results), and Scopus (9 results).

2.3 Screening and Study Selection

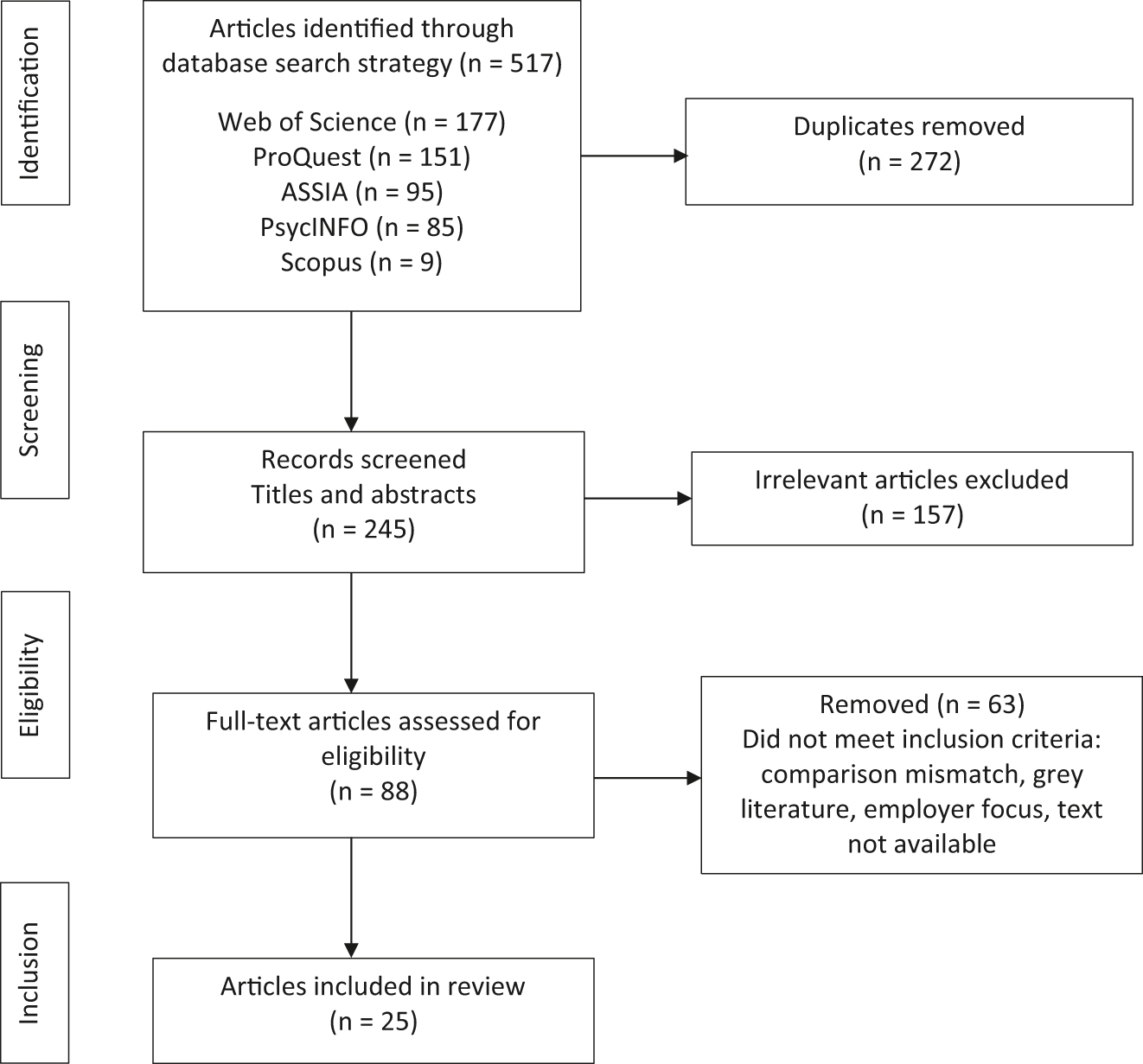

In total, 517 articles were identified following the search strategy steps as detailed and were imported into Covidence screening and data extraction manager (Veritas Health Innovation 2023). Duplicates were automatically removed, yielding a total of 245 articles for screening. Following the guidance by Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (2010), a transparent and reproducible screening process to assess eligibility for full text evaluation was undertaken. Firstly, titles and abstracts were reviewed for adherence to the inclusion criteria. 157 further studies were deemed as not fully complying with the inclusion criteria and were excluded, resulting in 88 studies for full text review. The full text of these potential articles were retrieved and assessed and 28 were selected for extraction and further analysis. Finally, the reference lists of these included studies were scrutinised for additional articles and a further 22 articles were identified for inclusion. Reasons for exclusion varied, including not relating specifically to older workers, intergenerational relations or ageism. Following further review and scrutiny, the screening and study selection process yielded a total of 25 studies for inclusion in the review and is reported and presented in a PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (see Figure 1).

PRISMA-ScR flow diagram of study selection process.

2.4 Data Extraction

The finalised 25 included articles were examined for compliance with the objectives of the scoping review by the research team. To chart the data and record characteristics and key information, a systematic record of the following was extracted and compiled into a data extraction table: author(s), year, region, title, publication, study aims, population and methods. In doing so, the researchers were able to characterise the research conducted to date and identify any potential research gaps. The extraction is presented in Table 1.

Ageism and intergenerational relations in the workplace.

| ID | Author | Year | Region | Title | Publication | Study aims | Population | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barabaschi | 2015 | Europe | Intergenerational solidarity in the workplace: Can it solve Europe’s labor market and social welfare crises? | Journal of Workplace Rights | Discusses solidarity between generations in the workplace | Four case countries (Belgium, France, Italy and Poland) | Opinion |

| 2 | Burmeister, wang, and Hirschi | 2020 | Switzerland | Understanding the motivational benefits of knowledge transfer for older and younger workers in age-diverse coworker dyads: An actors partner interdependence model | Journal of Applied Psychology | Investigates the motivations, benefits and consequences of knowledge transfer in age-diverse workforces | 173 age-diverse co-worker dyads in diverse industries (younger mean age: 28.12 and older mean age: 54.73) | Quantitative |

| 3 | Claes and van de ven | 2008 | Belgium and Sweden | Determinants of older and younger workers’ job satisfaction and organisational commitment in the contrasting labour markets of Belgium and Sweden | Ageing & Society | Explores the factors that keep older workers satisfied and committed at work by contrasting older and younger workers in favourable (Sweden) and unfavourable labour markets (Belgium) | 209 workers aged 16 to 25 and 235 workers aged 50 to 66 | Quantitative |

| 4 | Dencker, Joshi, and Martocchio | 2007 | US | Employee benefits as context for intergenerational conflict | Human Resource Management Review | Discusses how employee benefits practices detract from job motivation across different age groups | US census data | Review |

| 5 | Desmette and Gaillard | 2008 | Belgium | When a “worker” becomes an “older worker”: The effects of age-related social identity on attitudes towards retirement and work | Career Development International | Investigates the relationship between perceived social identity as an older worker and attitudes towards early retirement and commitment to work | 352 French-speaking workers aged 50 to 59 working in private organizations | Quantitative |

| 6 | Fasbender, Burmeister, and Wang | 2023 | UK | Managing the risks and side effects of workplace friendships: The moderating role of workplace friendship self-efficacy | Journal of Vocational Behaviour | Investigates the risks and side effects of workplace friendships for co-workers | 950 employees across two studies aged over 18 | Quantitative |

| 7 | Finkelstein, King, and Voyles | 2015 | US | Age meta-stereotyping and cross-age workplace interactions: A meta view of age stereotypes at work | Work, Aging and Retirement | Establishes a framework to understand dynamics of age meta-stereotypes in the workplace | Review | |

| 8 | Firzly, van de Beeck, and Lagacé | 2021 | Canada | Let’s work together: Assessing the impact of intergenerational dynamics on young workers’ ageism awareness and job satisfaction | Canadian Journal on Aging | Aims to assess if intergroup contact has a positive effect on perceptions of ageism amongst canadian younger workers | 612 student workers aged under 45 | Quantitative |

| 9 | Hanrahan, Thomas, and Finkelstein | 2023 | US | You’re too old for that! ageism and prescriptive stereotypes in the workplace | Work, Aging and Retirement | Explores what happens when a worker violates prescriptive age identity stereotypes (i.e., does not act in ways that align with cultural expectations for people in their age group) | 664 workers aged 18 to 75 | Quantitative |

| 10 | Iweins et al. | 2013 | Belgium | Ageism at work: The impact of intergenerational contact and organizational multi-age perspective | European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology | Examines attitudes towards and contextual factors impacting age diversity and intergenerational relationships at work | 316 Belgian employees aged under 50 across 2 studies | Quantitative |

| 11 | Jelenko | 2020 | Slovenia | The role of intergenerational differentiation in perception of employee engagement and job satisfaction among older and younger employees in Slovenia | Changing Societies & Personalities | Investigates influence of age discrimination on job satisfaction and employee engagement between age cohorts | 755 younger workers aged 18 to 35 and 750 older workers aged over 55 | Quantitative |

| 12 | Lagacé, van de Beeck, and Firzly | 2019 | Canada | Building on intergenerational climate to counter ageism in the workplace? A cross-organizational study. | Journal of Intergenerational Relationships | Explores factors to counter negative outcomes of ageism in the workplace | 415 workers aged over 45 in public and private sectors | Quantitative |

| 13 | Lagacé et al. | 2022 | Canada | Testing the shielding effect of intergenerational contact against ageism in the workplace: A Canadian study | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | How cross generational contacts in the workplace and knowledge sharing practices reduce ageist attitudes, increasing work engagement levels and intentions to remain | 603 workers aged 18 to 68 | Quantitative |

| 14 | Lagacé et al. | 2023 | Canada | Fostering positive views about older workers and reducing age discrimination: A retest of the workplace intergenerational contact and knowledge sharing model | Journal of Applied Gerontology | Aims to understand psychosocial mechanisms that may counteract age discrimination and help retain workers | 500 workers aged 19 to 73 | Quantitative |

| 15 | Lavoie-Tremblay | 2010 | Canada | Retaining nurses and other hospital workers: An intergenerational perspective of the work climate | Journal of Nursing Scholarship | Describes and compares work climate perceptions and intentions to quit amongst hospital workers | 1,324 healthcare workers aged 18 to 63 | Quantitative |

| 16 | Lyons and Schweitzer | 2017 | Canada | A qualitative exploration of generational identity: Making sense of young and old in the context of today’s workplace | Work, Aging and Retirement | Investigates individuals’ generational identities in the workplace. How and why people identify with generational groups (or not), and whether there are age-related patterns in generational identification. | 105 workers, 57 women (54 %) and 48 men (46 %), average age of 39 years | Qualitative |

| 17 | McCann and Keaton | 2013 | US and Thailand | A cross cultural investigation of age stereotypes and communication perceptions of older and younger workers in the USA and Thailand | Educational Gerontology | Younger workers’ perceptions of older and same age worker stereotypes and communication | 142 American students and 125 Thai students aged 18 to 33 | Quantitative |

| 18 | McConatha, Kumar, and Magnarelli | 2022 | US | Ageism, job engagement, negative stereotypes, intergenerational climate, and life satisfaction among middle-aged and older employees in a university setting | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | How experiences of ageism, work climate and job engagement impact life satisfaction | 115 university staff aged 50 to 79 | Quantitative |

| 19 | Moriarity, Brown, and Schultz | 2014 | US | We have much in common: The similar inter-generational work preferences and career satisfaction among practicing radiologists | Journal of the American College of Radiology | Assesses generational differences in workplace satisfaction | 1,577 radiologists aged 30 to 68 | Quantitative |

| 20 | Patel, Tinker, and Corna | 2018 | UK | Younger workers’ attitudes and perceptions towards older colleagues | Working with Older People | Investigates younger workers’ views on intergenerational relationships within the workplace | Ten employees aged under 35 in a multi-generational workplace | Qualitative |

| 21 | Sudheimer | 2009 | US | Stories appreciating both sides of the generation gap: Baby boomer and generation X nurses working together | Nursing Forum | Discusses differences in work ethics and values between age groups | Opinion | |

| 22 | Tybjerg-Jeppesen et al. | 2023 | Denmark | Is a positive intergenerational workplace climate associated with better self-perceived aging and workplace outcomes? A cross-sectional study of a representative sample of the Danish working population | Journal of Applied Gerontology | Examines association between intergenerational workplace climate and self-perceived aging, work engagement and intentions to quit | 1,571 workers aged 18 to 74 | Quantitative |

| 23 | Von Humboldt et al. | 2023 | Portugal | Is age an issue? Psychosocial differences in perceived older workers’ work (un)adaptability, effectiveness, and workplace age discrimination | Educational Gerontology | Perceptions about older workers | 453 workers aged 18 to 65 | Quantitative |

| 24 | Weingarten | 2009 | US | Four generations, one workplace: A gen X-Y staff nurse’s view of team building in the emergency department | Journal of Emergency Nursing | Opinions of four generations at work together | Opinion | |

| 25 | Yeung et al. | 2021 | Hong Kong | Age differences in visual attention and responses to intergenerational and non-intergenerational workplace conflicts | Frontiers in Psychology | Investigates if levels of visual attention, emotional responses and conflict strategies will be moderated by the age group of workers, conflict type, and their interaction | 48 younger workers aged 20 to 34 and 46 older workers aged 40 to 68 | Quantitative |

2.5 Study and Population Characteristics

The selected articles comprised of 18 quantitative studies (Burmeister, Wang, and Hirschi 2020; Claes and Bart Van de Ven 2008; Desmette and Gaillard 2008; Fasbender, Burmeister, and Wang 2023; Firzly, Van de Beeck, and Lagacé 2021; Hanrahan, Thomas, and Finkelstein 2023; Iweins et al. 2013; Jelenko 2020; Lagacé, Van de Beeck, and Firzly 2019; Lagacé et al. 2022; Lagacé et al. 2023; Lavoie-Tremblay et al. 2010; McCann and Keaton 2013; McConatha, Kumar, and Magnarelli 2022; Moriarity, Brown, and Schultz 2014; Tybjerg-Jeppesen et al. 2023; von Humboldt et al. 2023; Yeung et al. 2021), two qualitative studies (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017; Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018), two review articles (Dencker, Joshi, and Martocchio 2007; Finkelstein, King, and Voyles 2015) and three opinion articles (Barabaschi 2015; Sudheimer 2009; Weingarten 2009). Of these, six studies explored not only ageism but also age discrimination with an intersectional gender perspective (Burmeister, Wang, and Hirschi 2020; Desmette and Gaillard 2008; Firzly, Van de Beeck, and Lagacé 2021; Lyons and Schweitzer 2017; Moriarity, Brown, and Schultz 2014; von Humboldt et al. 2023).

Geographically, 14 studies were conducted in the US and Canada, 10 in Europe and one study was located in Asia. The articles investigated workers aged 16 and older, focusing on diverse questions related to ageism and intergenerational relationships in the workplace, particularly between younger and older workers. The definitions of younger and older workers varied significantly across the studies, influenced by cultural and policy contexts. Younger workers are often defined as individuals aged 15–24, with some policies extending this to 29 years (Haar Ter and Rönnmar 2014) and older workers as those aged 55–64 (Steiber 2014). Among our selected articles, the Slovenian study (Jelenko 2020) defined the younger workers as 18–35 years old and older workers as 55 years and above. In the UK study (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018), younger workers were those below 35 years old and older workers were individuals above 50 years old. The Danish study by Tybjerg-Jeppesen et al. (2023) considered younger workers as those aged 18 to 30 and older workers as those 50 years and above. However, in the Hong Kong study (Yeung et al. 2021), younger workers were people aged 20–34 while older workers were those aged 40–68 years old, and the Canadian study defined the group of older workers as employees aged 45 years and above (Lagacé, Van de Beeck, and Firzly 2019).

2.6 Data Coding and Analysis

Following the thematic analysis guidelines proposed by Braun and Clarke (2021), patterns within the data were identified and analysed to capture the spectrum of concepts across the literature. This was achieved by reading and noting features in a systematic way. The codes were grouped into four overarching themes with associated sub-themes and are now discussed. The themes and examples extracted from the literature are presented in Table 2 (The codebook with detailed examples from the literature is available upon request from the authors).

Themes and examples extracted from the literature.

| Core theme | Sub-themes | Example in literature |

|---|---|---|

| Ageism and gender in workplace discrimination | Ageism |

An inclusive intergenerational workplace is the most effective buffer against ageism [12] |

| Sustainability |

Age discrimination impacts on job satisfaction and employee engagement across older and younger, which will play a deciding role in the broader socio-economic context via the future job market, providing higher economic growth, a sustainable healthcare and retirement system, etc. [11] |

|

| Gender |

Older female actors derived less motivational benefits from partner knowledge receiving. Dyadic gender difference had sizeable effects on older workers’ competence need fulfilment and their intention to remain [2] |

|

| Generational identity and stereotyping in the workplace | Generational identity |

Misconceptions exist about every generation [24] |

| Generational grouping |

Workers tend to interact with individuals in their own age group [20] |

|

| Perceptions of older workers |

Older workers seen as more uncomfortable with new technology, less flexible, more cautious at work and more loyal to their employer [17] |

|

| Perceptions of younger workers |

Young people adaptive and responsive to change [16] |

|

| Age stereotypes |

Older workers more likely to be associated with negative work-related stereotypes [23] |

|

| Intergroup contact |

Intergroup contacts prevent development of negative stereotypes [13] |

|

| Intergenerational dynamics and knowledge transfer in the workplace | Working in a multigenerational workplace |

A positive intergenerational climate at work enhances job satisfaction and retention [8] |

| Communication between generations |

Cultural differences in communications remind us that experiences of aging and working are not universal [17] |

|

| Intergenerational tension |

Older and younger workers respond differently to conflict at work [25] |

|

| Knowledge transfer |

The employment of younger and older workers can be rendered more complementary by promoting knowledge transfers across generations within firms, allowing more sustainable and likely permanence at work and ensuring transmission of knowledge and skills within the company [1] |

|

| Workplace climate and generational work experiences | Workplace climate |

Positive intergenerational workplace climate related to more positive experiences of aging [22] |

| Generational work experiences |

Employee benefits can contribute to intergenerational conflict [4] |

|

| Organizational fairness |

Fairness in organisation procedures a mediator for positive attitudes towards older workers [10] |

|

| Loyalty to employer |

Older people value long tenure with employer, shows evidence of loyalty and perseverance [16] |

|

| Job satisfaction | Skill discretion and organisational fairness predicts job satisfaction and commitment to employer [3] |

3 Results and Discussion

This review aims to synthesis and present evidence on a range of issues relating to ageism and intergenerational relations in the workplace. Four overarching themes were identified and are now presented: ageism and gender in workplace discrimination, generational identity and stereotyping in the workplace, intergenerational dynamics and knowledge transfer in the workplace, and organisational fairness, workplace climate and generational work experiences.

3.1 Ageism and Gender in Workplace Discrimination

Age discrimination affects job satisfaction and engagement across all age groups, and it can influence broader socio-economic outcomes, such as social cohesion, economic growth and the sustainability of healthcare and retirement systems (Jelenko 2020). Ageist attitudes are not limited to any one age group, and both young and older workers who experience ageism at work report decreased work engagement and a reduced intention to stay in their jobs (Lagacé et al. 2023). Interestingly, von Humboldt et al. (2023) found that as people age, their perception of experiencing age discrimination tends to increase. Ageist stereotypes towards older workers can harm both organizations and individuals. When older workers leave, organizations may suffer lose valuable knowledge, which affects the sustainability of institutional memory (Lagacé, Van de Beeck, and Firzly 2019). At an individual level, older workers who report age-related discrimination often experience lower life satisfaction (McConatha et al. 2022).

Gender can influence generational differences in workplace settings (Moriarity, Brown, and Schultz 2014). For older women, employment experiences are often shaped by the intersection of age-based discrimination and gendered roles. For example, Burmeister, Wang, and Hirschi (2020) found that gender can significantly impact older workers’ sense of competence and their intentions to remain in the workforce. Older female workers are often less motivated by receiving knowledge from their colleagues (Burmeister, Wang, and Hirschi 2020), which can affect their job satisfaction and decision about continuing employment (McConatha et al. 2023). Technology also poses unique challenges. Albinowski and Lewandowski (2024) found that advancements in ICT and robots have reduced the sectoral employment opportunities and wage shares of European women aged 60 and above. In blue-collar jobs, older female applicants experience greater age discrimination during hiring compared to older men (Drydakis et al. 2017). In some industries, older women face compounded challenges. For instance, in the IT sector, they are underrepresented and often part of a vulnerable group (Brooke 2009). Similarly, Fitzpatrick and O’Neill (2023) highlighted that older women in the film industry encounter significant ageism, with stark underrepresentation in leadership roles.

Besides gender, such factors as life-cycle stage and work culture also can interact with age to influence how workers define their social identity and generational affiliations (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017). For instance, social roles tied to family responsibilities, like caregiving, often lead women (but not men) to retire early to meet family needs (Wu, Li, and Waern 2022), while men may seek ways to stay active in the workforce as they age (Desmette and Gaillard 2008). Furthermore, research by Firzly, Van de Beeck, and Lagacé (2021) suggests that age can moderate the negative impact of gender on ageist practices toward older workers, which indicates the need for more detailed research into how factors like gender, education level, and profession interact and influence age-related stereotypes and discrimination in the workplace (von Humboldt et al. 2023).

3.2 Generational Identity and Stereotyping in the Workplace

Identifying with a generational group is a way for individuals to make sense of the workplace social context, providing a basis for both social and individual identity within an organisation (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017). Across the literature, age-related patterns in workers’ identification with generational groups highlight how people view themselves, understand workplace group dynamics and relate to organisational culture (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017). Workers often prefer interacting with colleagues of their own age group (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018), however, recognizing similarities between age groups has been found to mediate negative stereotypes about other groups and foster positive relationships (Iweins et al. 2013).

Workplaces with distinct generational groupings tend to develop more positive attitudes toward older workers. Yet, when older workers identify closely with age-related peers, they often hold more negative attitudes toward their work and express a stronger desire to retire early (Desmette and Gaillard 2008). Generational identity at work can influence perceptions with the group and, in the case of older workers, it may lead to disadvantages compared to younger age groups (von Humboldt et al. 2023). Younger workers, on the other hand, may be shielded from awareness of negative stereotypes about older workers due to their generational identity (Firzly, Van de Beeck, and Lagacé 2021). While misconceptions exist for every generation (Weingarten 2009), Patel, Tinker, and Corna (2018) found that the tendency for workers to form groups based on age can intensify conflicts and add complexity to the work environment, which is in line with the findings of Weingarten (2009).

Perceptions of other generational groups reveal how generational identity can shape workplace stereotypes. Younger workers often view older colleagues as reliable, hardworking, experienced, and willing to share knowledge, contributing to better decision making and a positive work environment (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018). These positive views about older workers have been linked to increased work engagement for all employees (Lagacé et al. 2022). However, when younger workers tend to have neutral or mixed perceptions about the cognitive abilities of their older colleagues (McCann and Keaton 2013), they may also perceive older colleagues as resistant to change or less adaptable (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017; McCann and Keaton 2013; Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018; von Humboldt et al. 2023).

Contradictions arise in perceptions of older workers. They are often seen as loyal to their employer (McCann and Keaton 2013) but may be viewed as prioritizing responsibilities outside of work, such as caregiving (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018). A study by Van Dalen and colleagues (2010) involving 10 Dutch companies found that both employers and employees across all age groups view older workers as loyal to employers and highly committed to organization. Older workers are sometimes perceived as less uncomfortable with new technology (McCann and Keaton 2013), which can reinforce generational stereotypes (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017). As to younger workers, there is a general perception that they lack a strong work ethic and are more self-centred (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017) and are less likely to do additional shifts at work (Sudheimer 2009).

Stereotypes about generational groups shape workplace perceptions across the literature, with younger workers more often holding different views about both their own and other generations (McCann and Keaton 2013). Age meta-stereotyping refers to the process by which one group perceives how they believe another group views them (Vauclair et al. 2016), and it adds an additional layer of complexity to age-diverse interactions (Finkelstein, King and Voyles 2015). Negative stereotypes about older workers, for instance, viewing them as inflexible or outdated, are often deeply entrenched (von Humboldt et al. 2023). Violating age-related expectations, such as an older worker ‘acting young’, can lead to negative judgments about their stability (Hanrahan, Thomas, and Finkelstein 2023).

Positive intergroup contact can improve perceptions across generational lines, in particular, toward older workers and has been associated with increased work engagement (Lagacé et al. 2022). Encouraging open communication and understanding (Weingarten 2009), and promoting intergroup interactions, can help reduce stereotypes and foster a more inclusive workplace environment (Lagacé et al. 2022).

3.3 Intergenerational Dynamics and Knowledge Transfer in the Workplace

A positive intergenerational climate at work has been shown to enhance job satisfaction and employee retention (Firzly, Van de Beeck, and Lagacé 2021). The prevailing findings of the study by Patel, Tinker, and Corna (2018) revealed that many workers appreciate a generational mix in the workplace, as different age groups often bring complementary skills. For instance, older workers tend to excel in customer service and social skills, while younger workers often perform better with technical skills (Van Dalen, Henkens, and Schippers 2010). Additionally, research by Frerichs et al. (2012) indicates that knowledge transfer between younger and older workers is an effective practice for active ageing. This exchange of knowledge and skills not only promotes the retention of older employees but also helps organizations address the challenges of an ageing workforce (Frerichs et al. 2012).

In general, younger workers who interact frequently with older colleagues hold more positive attitudes toward them (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018). However, motivations for social interactions at work differ between age groups. Older workers see these interactions as a measure of personal success and a way to boost productivity, while younger workers view them as opportunities for mentorship and network-building (Moriarity, Brown, and Schultz 2014). Younger workers generally respect their older colleagues, though this respect often leads to more formal communication with them (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018). Older workers reported that their work domain was devalued when their social identity as an older worker did not translate into meaningful relationships at work (Desmette and Gaillard 2008), and younger workers found that older colleagues could be intimidating, resulting in a hesitation to ask questions for fear of being judged (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018). When the boundaries between older and younger groups are rigid, it can lead to disengagement (Desmette and Gaillard 2008).

Intergenerational tensions are often rooted in differing approaches to work and can be exacerbated when generational groups become insular (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018). A lack of understanding about generational cultures, styles, and backgrounds could lead to conflict in the workplace (Weingarten 2009). Generational differences in workplace friendships have also been linked to role conflicts and incivility toward colleagues of other generations (Fasbender, Burmeister, and Wang 2023), and these generational differences can negatively impact on job satisfaction (Jelenko 2020). Older workers in poor health or in physically demanding roles are more likely to engage in intergenerational competition (Desmette and Gaillard 2008), while younger workers may feel competitive when they perceive that older workers are staying in higher positions longer than expected (Sudheimer 2009). Remarkably, older workers tend to manage emotional reactions to workplace conflict more effectively than younger employees (Yeung et al. 2021).

Knowledge transfer across generations in the workplace is widely recognized as mutually fulfilling and beneficial. According to Barabaschi (2015), the French government introduced a labour market policy in 2013 aimed at supporting the entry of young people into the workforce and retaining older workers. This initiative promotes sustainable employment and the transfer of knowledge and skills by pairing young employees with experienced senior workers (Barabaschi 2015).

Mentorship opportunities also provide motivational benefits for all age groups and contribute to staff retention (Burmeister, Wang, and Hirschi 2020). Research by Wikström and colleagues (2023) highlights the importance of trust and a sense of community in mentorship relationships. These factors enhance socialization, leading to increased social capital through learning and retaining employees (Wikström et al. 2023). However, younger workers are often in the role of receiving knowledge without reciprocating, due to organizational age norms and their own goal priorities (Burmeister et al. 2024). They may also hesitate to ask questions or be vulnerable (Patel, Tinker, and Corna 2018; Wikström et al. 2023). Meanwhile, older workers may feel that participating in intergenerational knowledge sharing does not always lead to a sense of inclusion or value (Lagacé, Van de Beeck, and Firzly 2019). Therefore, organizational support, along with a culture that promotes knowledge-sharing, should be prioritized (Burmeister et al. 2024).

Additionally, bi-directional knowledge sharing practices between younger and older workers is crucial for fostering positive attitudes toward ageing (Lagacé et al. 2023), as it increases younger workers’ awareness of ageist behaviours in the workplace (Firzly, Van de Beeck, and Lagacé 2021). Moreover, continual, trustful interactions between mentors and mentees are essential for building strong, mutually beneficial relationships (Wikström et al. 2023).

3.4 Workplace Climate and Generational Work Experiences

Older workers often place greater value on organisational structures and processes compared to younger workers (Lavoie-Tremblay et al. 2010). Benefits such as pensions and medical care are more important to older workers, while younger workers tend to focus on wage levels to meet higher housing and child-rearing costs (Dencker, Joshi, and Martocchio 2007). These differences in priorities can sometimes lead to intergenerational conflict, as younger workers may view older employees as having more favourable work conditions (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017). Generational differences also emerge in attitudes toward job loyalty and job insecurity tends to have a more negative impact on older workers (Claes and Van de Ven 2008), since they often value long tenures as a sign of loyalty and perseverance; in contrast, younger workers often prefer flexibility and are less inclined to commit to a single employer long-term (Lyons and Schweitzer 2017).

An inclusive intergenerational workplace is one of the most effective defences against ageism (Barabaschi 2015; Lagacé, Van de Beeck, and Firzly 2019), as it reduces feelings of discrimination among older workers and fosters a sense of belonging for all employees (Lagacé, Van de Beeck, and Firzly 2019). Positive intergenerational collaborations can also raise younger workers’ awareness of ageist practices, promoting mutual respect across age groups (Firzly, Van de Beeck, and Lagacé 2021). From human resource management (HRM) perspective, organisational performance is closely linked to HR activities in recruitment, development and employee management, therefore, effective HR practices can boost employee commitment and drive greater effort (Dastmalchian et al. 2015).

A positive workplace climate contributes to more favourable perceptions of ageing, as it is associated with better self-perceived ageing, increased work engagement and lower turnover intentions (Tybjerg-Jeppesen et al. 2023). A supportive and friendly work environment benefits employees of all generations in the workplace (Lavoie-Tremblay et al. 2010) by enhancing job satisfaction (Lagacé, Van de Beeck, and Firzly 2019). A study by Biswas, Boyle and Bhardwaj (2021), involving 182 human resource managers in Bangladeshi companies, concluded that supportive HR practices foster a positive organisational climate, promoting equal opportunity for everyone to grow and succeed irrespective of their background and identity. This inclusive climate enables organisations to take advantage of creativity and innovation offered by their diverse talents, which is a critical factor for the organisation to thrive in a dynamic market (Biswas, Boyle, and Bhardwaj 2021). Furthermore, organisational fairness, particularly when combined with opportunities for skill discretion, has been found to predict job satisfaction and commitment to the employer (Claes and Bart Van de Ven 2008). Fairness in organisational procedures also help improve attitudes toward older workers (Iweins et al. 2013), and employers play a critical role by facilitating mentoring and age-diverse learning opportunities (Burmeister, Wang, and Hirschi 2020).

4 Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, our inclusion criteria were restricted to articles published in peer-reviewed journals and written in English. While this approach simplifies the review process, it introduces potential biases, such as publication bias, where studies with positive findings are more likely to be published. Additionally, unlike some reviews that incorporate gray literature and use translation tools to include non-English studies, our review lacks this comprehensiveness.

Second, we excluded dissertations, theses, books, and book chapters from our selection criteria. This exclusion could lead to selection bias by omitting potentially valuable contributions from these sources.

Lastly, as a scoping review, this study differs from systematic reviews in its objectives and methodologies. While systematic reviews focus on synthesizing specific outcomes, often through techniques like meta-analysis, this scoping review provides a broad overview of the existing literature. Although it does not offer detailed data synthesis, it serves as a foundation for future research. Specifically, it can guide quality assessments of related studies and support in-depth synthesis through systematic literature reviews in the future (Armstrong et al. 2011).

5 Conclusions

This scoping review synthesized a broad range of literature on ageism and intergenerational dynamics in the workplace, offering valuable insights into how these phenomena shape workplace culture, employee engagement, and organizational effectiveness. The findings demonstrate that ageist attitudes negatively impact workers of all ages, with older workers often facing marginalization and younger workers experiencing disengagement in non-inclusive environments.

A key take-away is that an inclusive intergenerational workplace climate not only helps buffer against ageism but also enhances job satisfaction and retention of all employees. Effective management of generational diversity and a climate of intergenerational cooperation can foster successful organizational performances and promote workplace harmony (Macovei and Martinescu-Bădălan 2022). The review underscores the compounded discrimination faced by older women, pointing to the need for future research on gendered ageism and its impact on opportunities for older workers, especially women. As traditional Human Resource Management (HRM) practices may overlook these intersecting factors, potentially leading to ineffective age management strategies (Aaltio, Salminen, and Koponen 2014), a holistic understanding of age and gender is crucial.

To address these challenges, organizations should adopt holistic HRM strategies that incorporate sustainability and gender perspectives. By aligning with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), sustainable HRM practices can play a pivotal role in fostering a sustainable, equitable, and inclusive workforce. Sustainable HRM is essential for effectively managing workplace dynamics, as it explicitly recognizes the need to mitigate the negative impacts of traditional HRM practices on all employees (Kramar 2014). By implementing sustainable HRM policies that leverage the skills and competencies of all age groups, organizations can actively combat ageism (McGuire and Robertson 2007). Examples include age-diverse recruitment practices, continuous training, knowledge sharing, and development opportunities for older workers to recognize and promote their expertise and value (Franz 2023, p. 109, p. 119). Moreover, continuous accountability in executing fair employment policies ensures that older workers, especially women, are not overlooked or undervalued (Franz 2023, p. 116, p. 121). A European study by Visser, Lössbroek, and van der Lippe (2021) found that while traditional HR practices (e.g. demotion) harm older workers’ well-being and job satisfaction, effective HR policies, such as training, phased retirement options (e.g. reduced workloads, additional leave, semi-retirement), positively contribute to their well-being, directly aligning with SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth).

To promote inclusivity, organizations should implement Older Worker-Oriented HR Practices (OW-HRPs), such as training managers to address unconscious bias, establishing age-awareness programs, and creating flexible work arrangements like part-time work, job sharing, and telecommuting (Farr-Wharton et al. 2023). These initiatives are particularly crucial for older female workers who may have caregiving responsibilities and therefore can benefit from work-life balance support (Earl and Taylor 2015; Wu, Li, and Waern 2022; Farr-Wharton et al. 2023). Such practices align with SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Supporting these HR initiatives and practices dismantle stereotypes, build social capital, and enhance organisational performance (McGuire and Robertson 2007).

Taken together, this review highlights the complexity of ageism and intergenerational dynamics in contemporary workplaces, and suggests that organizations adopt effective and inclusive HR policies and practices, such as training, phased retirement, flexible work arrangements, and targeted age management strategies. Beyond gender and sustainability perspectives, further research, for example, longitudinal quantitative studies, comparative qualitative studies, or mixed-methods approaches, is needed to examine regional and cultural differences, particularly in Asian and Global South contexts, and to explore how factors like education, job type, and citizenship status influence experiences of ageism and intergenerational interactions in workplace settings.

Funding source: Trinity College Dublin

Acknowledgments

Trinity Research in Social Sciences (TRiSS) Research Fellowship, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland provided the funding for this work.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: Trinity Research in Social Sciences (TRiSS) Research Fellowship, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland provided the funding for this work.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Aaltio, Iiris, Maria Salminen Hanna, and Koponen Sirpa. 2014. “Ageing Employees and Human Resource Management – Evidence of Gender-Sensitivity?” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 33 (2): 160–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-10-2011-0076.Search in Google Scholar

Albinowski, Maciej, and Piotr Lewandowski. 2024. “The Impact of ICT and Robots on Labour Market Outcomes of Demographic Groups in Europe.” Labour Economics 87: 102481.10.1016/j.labeco.2023.102481Search in Google Scholar

Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’ Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards A Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.Search in Google Scholar

Armstrong, Rebecca, Belinda Hall, Jodie Doyle, and Elizabeth Waters. 2011. “Cochrane Update. ‘Scoping the Scope’ of a Cochrane Review.” Journal of Public Health 33 (1): 147–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr015.Search in Google Scholar

Barabaschi, Barbara. 2015. “Intergenerational Solidarity in the Workplace: Can it Solve Europe’s Labor Market and Social Welfare Crises?” Sage Open 5 (4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015621464.Search in Google Scholar

Biswas, Kumar, Brendan Boyle, and Sneh Bhardwaj. 2021. “Impacts of Supportive HR Practices and Organisational Climate on the Attitudes of HR Managers towards Gender Diversity – A Mediated Model Approach.” Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship 9 (1): 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-06-2019-0051.Search in Google Scholar

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: Sage Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Brooke, Libby. 2009. “Prolonging the Careers of Older Information Technology Workers: Continuity, Exit or Retirement Transitions?” Ageing and Society 29 (2): 237–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X0800768X.Search in Google Scholar

Burmeister, Anne, Mo Wang, and Andreas Hirschi. 2020. “Understanding the Motivational Benefits of Knowledge Transfer for Older and Younger Workers in Age-Diverse Coworker Dyads: An Actor–Partner Interdependence Model.” Journal of Applied Psychology 105 (7): 748–59. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000466.Search in Google Scholar

Burmeister, Anne, Yifan Song, Mo Wang, and Andreas Hirschi. 2024. “Understanding Knowledge Sharing from an Identity-Based Motivational Perspective.” Journal of Management 1–34, https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063241248106.Search in Google Scholar

Carta, Francesca, Francesco D’Amuri, and Till von Wachter. 2021. Workforce Aging, Pension Reforms, and Firm Outcomes. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper https://www.nber.org/papers/w28407 (accessed October 3, 2024).10.3386/w28407Search in Google Scholar

Claes, Rita, and Bart Van de Ven. 2008. “Determinants of Older and Younger Workers’ Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commitment in the Contrasting Labour Markets of Belgium and Sweden.” Ageing and Society 28 (8): 1093–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08007423.Search in Google Scholar

Dastmalchian, Ali, Nicola McNeil, Paul Blyton, Nicolas Bacon, Betsy Blunsdon, Hayat Kabasakal, Renin Varnali, and Claudia Steinke. 2015. “Organisational Climate and Human Resources: Exploring A New Construct in A Cross-National Context.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 53 (4): 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12081.Search in Google Scholar

Dencker, John, Aparna Joshi, and Martocchio Joseph. 2007. “Employee Benefits as Context for Intergenerational Conflict.” Human Resource Management Review 17 (2): 208–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

Dennis, Helen, and Kathryn Thomas. 2007. “Ageism in the Workplace.” Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging 31 (1): 84–9. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26555516.Search in Google Scholar

Desmette, Donatienne, and Mathieu Gaillard. 2008. “When A “Worker” Becomes an “Older Worker”: The Effects of Age-Related Social Identity on Attitudes towards Retirement and Work.” Career Development International 13 (2): 168–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810860567.Search in Google Scholar

Drury, Lisbeth, and Ulrike Fasbender. 2024. “Fostering Intergenerational Harmony: Can Good Quality Contact between Older and Younger Employees Reduce Workplace Conflict?” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 97 (4): 1789–812.10.1111/joop.12539Search in Google Scholar

Drydakis, Nick, Peter MacDonald, Vasiliki Bozani, and Vangelis Chiotis. 2017. “Inclusive Recruitment? Hiring Discrimination against Older Workers.” In Shaping Inclusive Workplaces Through Social Dialogue, edited by Alicia Arenas, Donatella Di Marco, Lourdes Munduate, and Martin Euwema, 87–102. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-66393-7_6Search in Google Scholar

Van Dalen, Hendrik, Kène Henkens, and Joop Schippers. 2010. “Productivity of Older Workers: Perceptions of Employers and Employees.” Population and Development Review 36 (2): 309–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00331.x.Search in Google Scholar

Earl, Catherine, and Philip Taylor. 2015. “Is Workplace Flexibility Good Policy? Evaluating the Efficacy of Age Management Strategies for Older Women Workers.” Work, Aging and Retirement 1 (2): 214–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wau012.Search in Google Scholar

Farr-Wharton, Ben, Tim Bentley, Leigh-Ann Onnis, Carlo Caponecchia, Abilio De Almeida Neto, Sharron O’Neill, and Andrew Catherine. 2023. “Older Worker-Orientated Human Resource Practices, Wellbeing and Leave Intentions: A Conservation of Resources Approach for Ageing Workforces.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20 (3): 2725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032725.Search in Google Scholar

Fasbender, Ulrike, Anne Burmeister, and Mo Wang. 2023. “Managing the Risks and Side Effects of Workplace Friendships: The Moderating Role of Workplace Friendship Self-Efficacy.” Journal of Vocational Behaviour 143: 103875.10.1016/j.jvb.2023.103875Search in Google Scholar

Finkelstein, Lisa, Eden King, and Elora Voyles. 2015. “Age Meta-Stereotyping and Cross-Age Workplace Interactions: A Meta View of Age Stereotypes at Work.” Work, Aging and Retirement 1 (1): 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wau002.Search in Google Scholar

Firzly, Najat, Lise Van de Beeck, and Martine Lagacé. 2021. “Let’s Work Together: Assessing the Impact of Intergenerational Dynamics on Young Workers’ Ageism Awareness and Job Satisfaction.” Canadian Journal on Aging 40 (3): 489–99. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980820000173.Search in Google Scholar

Fitzpatrick, Niamh, and Desmond O’Neill. 2023. “Exploring the Success of Older Female Directors: Creativity and Resilience of Old Age in the Face of Cultural Barriers.” Age and Ageing 52 (S3). https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afad156.273.Search in Google Scholar

Franz, Nadine. 2023. “Restructuring the Workforce through Non-ageist Hiring and Retention Practices that Value Aging Workers’ Expertise: Recognizing the Need for Workplace Age Diversity.” In Examining The Aging Workforce and Its Impact on Economic and Social Development, edited by Bruno de Sousa Lopes, Maria Céu Lamas, Vanessa Amorim, and Orlando Lima Rua, 107–28. Hershey: IGI Global Publishing.10.4018/978-1-6684-6351-2.ch006Search in Google Scholar

Frerichs, Frerich, Robert Lindley, Paula Aleksandrowicz, Beate Baldauf, and Sheila Galloway. 2012. “Active Ageing in Organisations: A Case Study Approach.” International Journal of Manpower 33 (6): 666–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437721211261813.Search in Google Scholar

Hanks, Roma Stovall, and MarjorieIcenogle. 2001. “Preparing for an Age-Diverse Workforce: Intergenerational Service-Learning in Social Gerontology and Business Curricula.” Educational Gerontology 27 (1): 49–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/036012701750069049.Search in Google Scholar

Hanrahan, Elizabeth, Courtney Thomas, and Lisa Finkelstein. 2023. “You’re Too Old for that! Ageism and Prescriptive Stereotypes in the Workplace.” Work, Aging and Retirement 9: 204–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waab037.Search in Google Scholar

Harter, Stephen. 1986. Online Information Retrieval: Concepts, Principles and Techniques. Cambridge: Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hegde, Rati, and Abhishek Kumar. 2024. “Ageism: The New Menace for the IT Workforce in India and How to Tackle it.” Journal of Business, Ethics and Society 4 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.61781/4-1I2024/3bmlm.Search in Google Scholar

Haar Ter, Beryl, and Mia Rönnmar. 2014. Intergenerational Bargaining, EU Age Discrimination Law and EU Policies – an Integrated Analysis. Amsterdam: AIAS – iNGenBar. https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.432345.Search in Google Scholar

von Humboldt, Sofia, Isabel Miguel, Joaquim Valentim, Andrea Costa, Gail Low, and Isabel Leal. 2023. “Is Age an Issue? Psychosocial Differences in Perceived Older Workers’ Work (un)Adaptability, Effectiveness, and Workplace Age Discrimination.” Educational Gerontology 49 (8): 687–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2022.2156657.Search in Google Scholar

Iweins, Caroline, Donatienne Desmette, Yzerbyt Vincent, and Stinglhamber Florence. 2013. “Ageism at Work: The Impact of Intergenerational Contact and Organizational Multi-Age Perspective.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 22 (3): 331–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.748656.Search in Google Scholar

Jelenko, Jernej. 2020. “The Role of Intergenerational Differentiation in Perception of Employee Engagement and Job Satisfaction Among Older and Younger Employees in Slovenia.” Changing Societies & Personalities 4 (1): 68–90. https://doi.org/10.15826/csp.2020.4.1.090.Search in Google Scholar

Kapoor, Camille, and Nicole Solomon. 2011. “Understanding and Managing Generational Differences in the Workplace.” Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 3 (4): 308–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554211111162435.Search in Google Scholar

Kramar, Robin. 2014. “Beyond Strategic Human Resource Management: Is Sustainable Human Resource Management the Next Approach?” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (8): 1069–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.816863.Search in Google Scholar

Kugley, Shannon, Anne Wade, James Thomas, Quenby Mahood, Anne-Marie Klint Jørgensen, Karianne Hammerstrøm, and Nila Sathe. 2016. “Searching for Studies: A Guide to Information Retrieval for Campbell Systematic Reviews.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 13 (1): 1–73. https://doi.org/10.4073/cmg.2016.1.Search in Google Scholar

Lagacé, Martine, Anna Rosa Donizzetti, Lise Van de Beeck, Caroline Bergeron, Philippe Rodrigues-Rouleau, and Audrey St-Amour. 2022. “Testing the Shielding Effect of Intergenerational Contact against Ageism in the Workplace: A Canadian Study.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (8): 4866. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084866.Search in Google Scholar

Lagacé, Martine, Lise Van de Beeck, Caroline Bergeron, and Philippe Rodrigues-Rouleau. 2023. “Fostering Positive Views about Older Workers and Reducing Age Discrimination: A Retest of the Workplace Intergenerational Contact and Knowledge Sharing Model.” Journal of Applied Gerontology 42 (6): 1223–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648231163840.Search in Google Scholar

Lagacé, Martine, Lise Van de Beeck, and Najat Firzly. 2019. “Building on Intergenerational Climate to Counter Ageism in the Workplace? A Cross-Organizational Study.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 17 (2): 201–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2018.1535346.Search in Google Scholar

Lavoie-Tremblay, Melanie, Maxime Paquet, Marie-Anick Duchesne, Anelise Santo, Ana Gavrancic, François Courcy, and Serge Gagnon. 2010. “Retaining Nurses and Other Hospital Workers: An Intergenerational Perspective of the Work Climate.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 42 (4): 414–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01370.x.Search in Google Scholar

Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and O’Brien Kelly. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5: 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.Search in Google Scholar

Lyons, Sean, and Linda Schweitzer. 2017. “A Qualitative Exploration of Generational Identity: Making Sense of Young and Old in the Context of Today’s Workplace.” Work, Aging and Retirement 3 (2): 209–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw024.Search in Google Scholar

Macovei, Crenguța Mihaela, and Fabiana Martinescu-Bădălan. 2022. “Managing Different Generations in the Workplace.” International Conference Knowledge-Based Organization 28 (2): 191–6. https://doi.org/10.2478/kbo-2022-0071.Search in Google Scholar

Manongcarang, Sittie Maryam Dumarpa, and Sonayah Dirampatun Guimba. 2024. “Intergenerational Challenges and How They Manifest in the Public Workforce: A Basis for Designing Effective Performance Management Strategies.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Management Practices 7 (25): 67–87. https://doi.org/10.35631/IJEMP.725007.Search in Google Scholar

Meshel, David, and Richard McGlynn. 2004. “Intergenerational Contact, Attitudes, and Stereotypes of Adolescents and Older People.” Educational Gerontology 30 (6): 457–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270490445078.Search in Google Scholar

McCann, Robert, and Shaughan Keaton. 2013. “A Cross-Cultural Investigation of Age Stereotypes and Communication Perceptions of Older and Younger Workers in the USA and Thailand.” Educational Gerontology 39 (5): 326–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2012.700822.Search in Google Scholar

McConatha, Jasmin, V.K. Kumar, and Jaqueline Magnarelli. 2022. “Ageism, Job Engagement, Negative Stereotypes, Intergenerational Climate, and Life Satisfaction Among Middle-Aged and Older Employees in a University Setting.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (13): 7554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137554.Search in Google Scholar

McConatha, Jasmin, V.K. Kumar, Jaqueline Magnarelli, and Georgina Hanna. 2023. “The Gendered Face of Ageism in the Workplace.” Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 10 (1): 528–36. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.101.13844.Search in Google Scholar

McGuire, Sharon, and Maxine Robertson. 2007. “Assessing the Potential Impact of the Introduction of Age Discrimination Legislation in UK Firms from an HRM and KM Perspective.” In Proceedings of Organizational Learning, Knowledge and Capabilities Conference (OLKC), 14–7. London and Ontario: The University of Western Ontario. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/wbs/conf/olkc/archive/olkc2/papers/mcguire_and_robertson.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Minbaeva, Dana. 2007. “Knowledge Transfer in Multinational Corporations.” MIR: Management International Review 47 (4): 567–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-007-0030-4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40658222.Search in Google Scholar

Moore, Jill, Marcee Everly, and Renee Bauer. 2016. “Multigenerational Challenges: Team Building for Positive Clinical Workforce Outcomes.” Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 21 (2): 3. https://doi.org/10.3912/ojin.vol21no02man03.Search in Google Scholar

Moriarity, Andrew, Manuel Brown, and Lonni Schultz. 2014. “We Have Much in Common: The Similar Inter-generational Work Preferences and Career Satisfaction Among Practicing Radiologists.” Journal of the American College of Radiology 11 (4): 362–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2013.08.008.Search in Google Scholar

Patel, Jasmine, Anthea Tinker, and Laurie Corna. 2018. “Younger Workers’ Attitudes and Perceptions towards Older Colleagues.” Working with Older People 22 (3): 129–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-02-2018-0004.Search in Google Scholar

Peng, Xiqiang, Xizhou Tian, Xiaoping Peng, and Jinyu Xie. 2024. “Age-Inclusive HR Practices and Older Workers’ Voice Behaviour: The Role of Job Crafting toward Strengths and Negative Age-Based Metastereotypes.” Personnel Review 53 (9): 2273–92, https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2022-0752.Search in Google Scholar

Sobrino-De Toro, Ignacio, Jesús Labrador-Fernández, and Victor De Nicolás. 2019. “Generational Diversity in the Workplace: Psychological Empowerment and Flexibility in Spanish Companies.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1953.10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01953Search in Google Scholar

Steiber, Nadia. 2014. “Aging Workers and the Quality of Life.” In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, edited by Alex Michalos, 111–6. Dordrecht: Springer.10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_58Search in Google Scholar

Sudheimer, Erin. 2009. “Appreciating Both Sides of the Generation Gap: Baby Boomer and Generation X Nurses Working Together.” Nursing Forum 44 (1): 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2009.00127.x.Search in Google Scholar

Takeuhi, Masumi, and Keiko Katagiri. 2024. “Effects of Workplace Ageism on Negative Perception of Aging and Subjective Well-Being of Older Adults According to Gender and Employment Status.” Geriatrics and Gerontology International 24 (S1): 259–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14819.Search in Google Scholar

Tricco, Andrea, Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, et al.. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.Search in Google Scholar

Tybjerg-Jeppesen, Anette, Paul Maurice Conway, Yun Ladegaard, and Christian Gaden Jensen. 2023. “Is A Positive Intergenerational Workplace Climate Associated with Better Self-Perceived Aging and Workplace Outcomes? A Cross-Sectional Study of a Representative Sample of the Danish Working Population.” Journal of Applied Gerontology 42 (6): 1212–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648231162616.Search in Google Scholar

Vauclair, Christin-Melanie, Maria Luísa Lima, Dominic Abrams, Hannah Swift, and Christopher Bratt. 2016. “What Do Older People Think that Others Think of Them, and Does it Matter? the Role of Meta-Perceptions and Social Norms in the Prediction of Perceived Age Discrimination.” Psychology and Aging 31 (7): 699–710. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000125.Search in Google Scholar

Veritas Health Innovation. 2023. “Covidence Systematic Review Software.” https://www.covidence.org.Search in Google Scholar

Visser, Mark, Jelle Lössbroek, and Tanja van der Lippe. 2021. “The Use of HR Policies and Job Satisfaction of Older Workers.” Work, Aging and Retirement 7 (4): 303–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waaa023.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Ying, and Weiwei Shi. 2024. “Effects of Age Stereotypes of Older Workers on Job Performance and Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer Intention and Mediating Mechanisms.” Behavioural Sciences 14 (6): 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14060503.Search in Google Scholar

Weingarten, Robin. 2009. “Four Generations, One Workplace: A Gen X-Y Staff Nurse’s View of Team Building in the Emergency Department.” Journal of Emergency Nursing 35 (1): 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2008.02.017.Search in Google Scholar

Wikström, Ewa, Rebecka Arman, Lotta Dellve, and Nanna Gillberg. 2023. “Mentoring Programs - Building Capacity for Learning and Retaining Workers in the Workplace.” Journal of Workplace Learning 35 (8): 732–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-01-2023-0003.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, Jing, Ying Li, and Margda Waern. 2022. “Suicide Among Older People in Different European Welfare Regimes: Does Economic (in)Security Have Implications for Suicide Prevention?” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (12): 7003. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127003.Search in Google Scholar

Yeung, Dannii, Derek Isaacowitz, Winnie Lam, Jiawen Ye, and Cyrus Leung. 2021. “Age Differences in Visual Attention and Responses to Intergenerational and Non-intergenerational Workplace Conflicts.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 604717 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.604717.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of the Zhejiang Normal University, China

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.