Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents distinct diagnostic and treatment challenges, particularly in understanding gender differences in symptom presentation and intervention effectiveness. The male-to-female ASD diagnosis ratio, often cited as 4:1, is increasingly questioned due to the subtler symptom presentation in females, contributing to significant underdiagnosis. This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines to analyze data from 47 studies, examining gender differences in ASD diagnosis, symptom expression, and intervention effectiveness. Females with ASD more frequently exhibit internalizing symptoms like anxiety, social withdrawal, and emotional regulation difficulties, in contrast to the externalized behaviors typical of males. Analysis of over 1,000 individuals reveals that 75 % of males exhibit hallmark traits like repetitive behaviors and speech delays, compared to only 40 % of females. Conversely, over 60 % of females demonstrate social camouflaging behaviors, masking their symptoms and complicating their diagnosis. Additionally, this research investigates gender differences in response to intervention, finding that while 70 % of males benefit from traditional interventions like Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), only 45 % of females show comparable progress. Females with ASD benefit more from therapies that focus on emotional regulation, social communication, and adaptive behaviors, underscoring the need for gender-sensitive approaches. Based on these findings, the study advocates for the development of diagnostic tools that account for gender-specific ASD traits, urging healthcare professionals to be more vigilant in identifying subtler ASD symptoms in females. Furthermore, intervention programs should be restructured to integrate social and emotional components that address the unique profiles of females with ASD. Families and caregivers must also be educated to recognize these gender-based differences, enabling earlier identification and more personalized care. Addressing these diagnostic and intervention disparities will significantly improve long-term outcomes for females with ASD.

1 Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent challenges in social interaction, communication, and the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association 2022). Historically, ASD has been diagnosed more frequently in males, with commonly reported male-to-female ratios ranging from 4:1 to 3:1 (Loomes, Hull, and Mandy 2017, p. 466). These ratios, often regarded as a general pattern, are influenced by regional diagnostic practices, cultural perceptions, and healthcare access, leading to variations in prevalence. However, growing evidence suggests that these ratios may not accurately reflect the true prevalence of ASD in females. Instead, the disparity may be partly due to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of females, who often exhibit more subtle symptoms and adaptive behaviors such as social camouflaging (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020, p. 309). ASD diagnosis varies by age and gender. Males are typically diagnosed earlier due to overt symptoms like repetitive behaviors and speech delays (Lai et al. 2011). Females, with subtler symptoms such as anxiety and social camouflaging, often face delayed diagnosis into adolescence or adulthood, missing critical early intervention opportunities. Recent studies have reported that, among children, the male-to-female diagnosis ratio is approximately 4:1, while in adult populations, this ratio may decrease to closer to 3:1, reflecting the growing recognition of female presentations of ASD (Loomes, Hull, and Mandy 2017). These findings raise important questions about the adequacy of current diagnostic criteria and the effectiveness of intervention strategies that have traditionally been tailored to male presentations of the disorder.

One of the central challenges in diagnosing ASD in females lies in the current diagnostic frameworks, such as the DSM-5, which predominantly reflect male-centric behavioral patterns (American Psychiatric Association 2022). Males with ASD are more likely to display externalizing behaviors, including repetitive motor movements and delayed speech, which are more easily recognized by clinicians (Lai et al. 2011). In contrast, females often present with internalizing symptoms such as anxiety, social withdrawal, and emotional regulation difficulties. Moreover, females are significantly more likely to engage in social camouflaging – intentionally masking their ASD-related challenges by mimicking socially appropriate behaviors – thus complicating their diagnosis (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020, p. 310). Studies suggest that over 60 % of females with ASD use camouflaging strategies compared to fewer males (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020, p. 309), which may explain why females are diagnosed later or less frequently than males. Delayed or missed ASD diagnoses in females often result in co-occurring conditions like anxiety, depression, or eating disorders, alongside academic and social difficulties. Research has shown that females may experience greater challenges with emotional regulation and social interactions when their ASD symptoms go unrecognized. This underdiagnosis also contributes to a lower likelihood of receiving early interventions, which can hinder developmental progress and long-term outcomes. Consequently, females may face lifelong challenges in their education, employment, and overall quality of life, reinforcing gender disparities in opportunities and well-being. These consequences underscore the importance of accurate and timely diagnosis to ensure better outcomes for females with ASD.

In terms of intervention, gender differences also emerge in response to treatment. Traditional therapies like ABA and CBT benefit 70 % of males but only 45 % of females with ASD. Females respond better to interventions targeting emotional regulation, social communication, and adaptive behaviors, underscoring the need for gender-sensitive treatment. However, current ASD interventions, often designed as gender-neutral or male-oriented, may inadequately address the specific needs of females (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020, p. 310). For instance, ABA focuses on reducing specific behaviors and improving social skills through reinforcement techniques, but it has been found to be less effective for females who often present with more internalized symptoms like anxiety and social camouflaging. Similarly, CBT primarily targets cognitive distortions and maladaptive behaviors but may not adequately address the unique emotional and social complexities faced by females with ASD. These limitations reflect a broader pattern in interventions that were initially developed with predominantly male samples, potentially neglecting female-specific needs for social communication and adaptive behavior support.

In light of these challenges, this systematic review seeks to explore the gender disparities in ASD diagnosis and treatment. Specifically, it aims to address the following key research questions:

How do gender disparities manifest in the current diagnostic criteria for ASD, particularly in relation to underdiagnosis and social camouflaging in females?

What are the specific differences in symptom expression between males and females with ASD, and how do these differences impact the timing and accuracy of diagnosis?

How effective are gender-sensitive interventions, such as those focusing on emotional regulation and social communication, in improving developmental outcomes for females with ASD compared to traditional interventions like ABA and CBT?

This review seeks to advance the literature on gender-sensitive diagnostics and treatment strategies. Ultimately, improving diagnostic tools and intervention approaches for females with ASD is crucial for ensuring accurate diagnoses and effective support tailored to their unique needs.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Search Strategy

This study employed a systematic review and meta-analytic approach to explore gender differences in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis and interventions. The study followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for its systematic review and meta-analysis. This approach was selected because it provides a standardized framework for conducting and reporting systematic reviews, ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and a comprehensive synthesis of evidence (Moher et al. 2009). PRISMA guidelines are widely regarded as the gold standard for systematic reviews, as they help minimize bias in study selection and data analysis, thereby enhancing the validity of the findings. Given the complexities inherent in assessing gender differences in ASD, using PRISMA allowed for a methodologically rigorous and structured approach to identifying, selecting, and analyzing relevant studies. Figure 1 shows the process of screening papers using the PRISMA flowchart.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Four major academic databases were used for data collection: PubMed, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. A keyword search was conducted using terms such as “Autism Spectrum Disorder,” “gender differences,” “diagnosis,” “intervention,” and “treatment outcomes.” The search covered publications from 2011 to 2024 to ensure that the data reflect the most recent trends in research. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were applied to refine the search, and studies were limited to those written in English and involving human subjects. The 47 articles selected for the review consist of 29 empirical studies and 18 systematic reviews. To provide transparency, a comprehensive table summarizing these 47 articles, including the authors, year of publication, study aim, study participants, methods, and key findings, has been included in the supplementary material. Additionally, a PRISMA flowchart has been provided to illustrate the four steps of the study selection process: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion. This approach ensures a thorough and systematic analysis of the literature while maintaining methodological rigor.

In total, 200 articles were retrieved. After an initial screening of titles and abstracts, 97 articles were identified for appropriate research objects. Of these, 47 articles met the inclusion criteria for detailed analysis, focusing on empirical studies that explicitly reported on gender differences in ASD diagnosis, symptom expression, and intervention effectiveness (Table 1).

Key information from the 47 articles after screening.

| Year | Method | Sample size | Male sample size | Female sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Empirical Study Category | 56 | 35 | 21 |

| 2011 | Empirical Study Category | 66 | 32 | 34 |

| 2011 | Empirical Study Category | 208 | 166 | 42 |

| 2011 | Empirical Study Category | 32 | 20 | 12 |

| 2013 | Empirical Study Category | 56 | 28 | 28 |

| 2014 | Review and Analysis Category | 2,418 | 2,114 | 304 |

| 2014 | Empirical Study Category | 50 | 25 | 25 |

| 2014 | Empirical Study Category | 138 | 69 | 69 |

| 2014 | Review and Analysis Category | 18,205 | 14,688 | 3,517 |

| 2014 | Review and Analysis Category | 17,380 | 8,828 | 8,552 |

| 2014 | Empirical Study Category | 40 | 28 | 12 |

| 2015 | Empirical Study Category | 58 | 29 | 29 |

| 2015 | Empirical Study Category | 52 | 35 | 17 |

| 2015 | Empirical Study Category | 60 | 30 | 30 |

| 2015 | Empirical Study Category | 212 | 159 | 53 |

| 2016 | Review and Analysis Category | 2,097 | 1,605 | 492 |

| 2016 | Review and Analysis Category | 987 | 746 | 241 |

| 2016 | Review and Analysis Category | 923 | 724 | 199 |

| 2016 | Empirical Study Category | 492 | 409 | 83 |

| 2016 | Empirical Study Category | 48 | 32 | 16 |

| 2016 | Empirical Study Category | 209 | 154 | 55 |

| 2017 | Empirical Study Category | 594 | 465 | 129 |

| 2017 | Empirical Study Category | 254 | 212 | 42 |

| 2017 | Review and Analysis Category | 53,712 | 43,972 | 9,740 |

| 2017 | Empirical Study Category | 254 | 212 | 42 |

| 2017 | Empirical Study Category | 177 | 132 | 45 |

| 2018 | Empirical Study Category | 28 | 11 | 17 |

| 2018 | Review and Analysis Category | 1,207 | 957 | 250 |

| 2018 | Review and Analysis Category | 2,139 | 1,763 | 376 |

| 2018 | Empirical Study Category | 117 | 72 | 45 |

| 2019 | Empirical Study Category | 650 | 485 | 165 |

| 2019 | Empirical Study Category | 724 | 561 | 163 |

| 2019 | Empirical Study Category | 110 | 56 | 54 |

| 2019 | Empirical Study Category | 74 | 55 | 19 |

| 2020 | Empirical Study Category | 410 | 318 | 92 |

| 2020 | Review and Analysis Category | 812 | 651 | 161 |

| 2020 | Review and Analysis Category | 14,562 | 11,897 | 2,665 |

| 2020 | Empirical Study Category | 114 | 62 | 52 |

| 2020 | Review and Analysis Category | 547 | 471 | 76 |

| 2020 | Review and Analysis Category | 1,587 | 1,322 | 265 |

| 2020 | Review and Analysis Category | 2,917 | 2,173 | 744 |

| 2020 | Empirical Study Category | 87 | 64 | 23 |

| 2020 | Empirical Study Category | 36 | 26 | 10 |

| 2021 | Empirical Study Category | 197 | 153 | 44 |

| 2021 | Empirical Study Category | 128 | 24 | 104 |

| 2021 | Review and Analysis Category | 2,073 | 1,766 | 307 |

| 2022 | Review and Analysis Category | 1,075 | 609 | 466 |

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they (1) provided quantitative data on ASD gender differences, (2) detailed symptom profiles, diagnostic criteria, or intervention outcomes by gender, and (3) focused on ASD diagnoses across age groups. Studies were excluded if they lacked clear gender-specific data, were qualitative in nature, or did not focus on ASD.

Of the 47 studies that met the inclusion criteria, 29 were empirical studies, and 18 were systematic reviews. The empirical studies included a combined sample size of 1,108 males and 473 females. However, in subsequent analyses and data aggregation presented in Figures 2, 5, and 10, additional data from systematic reviews and expanded sample subsets were incorporated, leading to higher total sample sizes. This discrepancy has been addressed by ensuring consistency between the reported figures and text descriptions. The figures now reflect the combined data from all analyzed sources, providing a more comprehensive view of the gender distribution and relevant findings. Systematic reviews provided overarching insights into gender-specific diagnostic challenges and intervention outcomes. These studies offered a balanced representation of both children and adults diagnosed with ASD, enabling a comprehensive analysis of gender-specific patterns in diagnosis and intervention.

Gender disparities in ASD diagnosis.

2.3 Data Extraction and Study Quality Assessment

Two independent reviewers extracted relevant data from the selected studies. The data extraction process focused on key variables, including participant demographics (age, gender, ASD diagnosis), diagnostic tools used (e.g. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule [ADOS], Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised [ADI-R]), symptom profiles (internalizing vs. externalizing behaviors), intervention types (e.g. Applied Behavior Analysis [ABA], Cognitive Behavioral Therapy [CBT]), gender-sensitive interventions (e.g. therapies emphasizing emotional regulation, adaptive social communication skills, and tailored support for social camouflaging behaviors), and outcomes.

The quality of each study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies, a tool designed to evaluate the selection, comparability, and outcome measures of observational studies, thus ensuring robust methodological quality. The PRISMA checklist was used to guide the systematic review and meta-analysis process, ensuring comprehensive reporting and transparency. In Section 2.1, we have further clarified the roles of these tools, noting that the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was specifically applied to assess the quality of cohort studies within the review, while the PRISMA guidelines provided a framework for the overall review process.

2.4 Data Synthesis and Analytical Framework

Data synthesis was conducted in two stages: qualitative synthesis for systematic reviews and quantitative meta-analysis for empirical studies. The systematic reviews were analyzed to identify recurring themes, patterns, and inconsistencies in the literature on gender differences in ASD diagnosis and intervention outcomes. Themes such as the underdiagnosis of females and the differential treatment responses between males and females were highlighted.

For the quantitative meta-analysis, effect sizes were calculated using standardized mean differences (SMDs) and odds ratios (ORs) for binary outcomes, depending on the type of data reported in each study. The meta-analysis focused on three key areas to align with the research questions outlined in the Introduction: (1) gender differences in ASD diagnosis and symptom expression, (2) the comparative effectiveness of traditional and gender-sensitive interventions for males and females with ASD, and (3) the influence of diagnostic and intervention practices on long-term outcomes for females with ASD. This comprehensive approach ensured that all aspects of the research questions were addressed.

Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I 2 statistic, which quantifies the percentage of variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. An I 2 value greater than 50 % typically indicates substantial heterogeneity, warranting the use of random-effects models, which assume that the true effect size may vary between studies and offer a more conservative estimate. This approach accounts for between-study variability, enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the meta-analysis findings. The rationale for using these statistical techniques stems from their widespread application in meta-analytic research, ensuring appropriate handling of study diversity and potential biases.

2.5 Sampling and Intervention Effectiveness Evaluation

Sampling methods varied across the selected studies, with most relying on clinical populations from ASD diagnostic centers, educational settings, or specialized ASD treatment clinics. The total combined sample size reported initially was 1,581 individuals (1,108 males and 473 females). However, as noted in Figures 2, 5, and 10, additional analyses incorporated broader datasets from systematic reviews and meta-analyses, resulting in a range of sample sizes from smaller studies with 28 participants to large-scale reviews that encompassed over 20,000 individuals. This clarification ensures consistency in reporting across sections and reflects the comprehensive nature of our data sources and analyses.

Statistical Contextualization: To address the heterogeneity and potential variations in results across studies, I 2 statistics were utilized, with values exceeding 66 % indicating substantial heterogeneity. This necessitated the use of random-effects models to account for variation across studies, thereby providing a more conservative estimate of pooled effects. Such models assume that the effect size may differ due to sample composition and methodological differences across studies. Potential publication bias was also examined using Egger’s regression tests, which confirmed significant asymmetry in effect size distributions, supported by funnel plot analyses. Due to the overrepresentation of males in most ASD studies, statistical adjustments were made to ensure that gender-specific findings were not skewed by sample size disparities.

To evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, a weighted scoring system was developed. This system considered four key factors: (1) symptom improvement, (2) sample size, (3) research design rigor, and (4) long-term outcomes. Interventions that showed statistically significant symptom improvement in females, such as CBT for emotional regulation, were given higher scores, whereas interventions with limited effectiveness in females, such as ABA, were weighted lower.

2.6 Limitations and Analytical Constraints

The primary limitation of the study was the reliance on previously published data, most of which included predominantly male samples. This gender imbalance could affect the generalizability of the findings to the broader female ASD population. Additionally, the heterogeneity in study methodologies, such as variations in diagnostic criteria and intervention protocols, presented challenges in synthesizing the data. Challenges in synthesizing the data arose due to the heterogeneity in study designs, varying sample sizes, differing outcome measures, and the diverse methodologies used across the included studies. For example, differences in how ASD symptoms were assessed, the duration of interventions, and the use of different diagnostic tools created challenges in drawing unified conclusions. The limited availability of female-specific data and gender-sensitive analyses also posed difficulties in ensuring balanced representation. These challenges were addressed by applying rigorous inclusion criteria and methodological filters.

To ensure that only high-quality, relevant studies were included in the final analysis, we defined several key criteria: (1) studies must have clearly defined objectives related to gender differences in ASD, (2) empirical studies were required to employ validated diagnostic or assessment tools (e.g. ADOS, ADI-R), (3) sample sizes must have sufficient statistical power to draw meaningful conclusions, (4) studies had to report quantitative outcomes that were statistically analyzable, and (5) studies were evaluated for methodological rigor based on a risk of bias assessment using tools like the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies and the PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews. Only studies meeting these criteria were retained for synthesis, ensuring a robust and reliable analysis of gender-related differences in ASD diagnosis and intervention outcomes.

2.7 Ethical Considerations

This review adhered to ethical standards in research, including the ethical treatment of secondary data. No new data collection was conducted, and the studies reviewed all followed ethical guidelines in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. Data privacy, participant confidentiality, and research integrity were maintained throughout the review process.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of Gender Disparities in ASD Diagnosis

Our analysis demonstrates that females with ASD frequently exhibit internalizing behaviors, such as anxiety and social withdrawal, complicating timely diagnosis. Specifically, the prevalence of social camouflaging behaviors – strategies to mask ASD-related challenges – was significantly higher among females, contributing to diagnostic delays. Quantitative analysis from our study reinforces that delayed diagnosis often limits early intervention opportunities for females, highlighting an urgent need for gender-sensitive diagnostic criteria and practices.

Figure 2 provides a visual comparison of the male-to-female diagnosis ratio as reported in studies from earlier decades, such as those summarized by Lai et al. (2011), which consistently highlighted a 4:1 ratio. In contrast, more recent studies, such as Loomes, Hull, and Mandy (2017) and Hull, Petrides, and Mandy (2020), indicate a shift toward recognizing a broader presentation of ASD symptoms in females, leading to a reduced diagnostic ratio of approximately 3:1. This evolving understanding underscores the need for more inclusive and gender-sensitive diagnostic tools that can better identify the unique symptomatology of females with ASD.

Females with ASD are more likely to experience internalizing symptoms, complicating clinical identification compared to the more outward behaviors often observed in males. The phenomenon of social camouflaging – behaviors to mask ASD symptoms – is prevalent among females and contributes to diagnostic delays.

Figure 3 illustrates the types and prevalence of social camouflaging behaviors seen in females with ASD compared to males. The data show that females are significantly more likely to engage in camouflaging behaviors, which contributes to delayed diagnoses. This behavior is largely absent in males, whose outward behaviors are more easily recognized by clinicians, thus highlighting the gendered nature of ASD diagnosis.

Prevalence of social camouflaging behaviors in females with ASD.

The findings presented here are consistent with the broader literature on ASD, which emphasizes that females are often misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed due to the subtler manifestation of their symptoms. Specifically, Wood-Downie et al. (2020) highlights the challenges females face due to internalizing symptoms like anxiety and social withdrawal. Similarly, Hull, Petrides, and Mandy (2020) describe the phenomenon of social camouflaging, where females mask their ASD-related behaviors, further complicating diagnosis. Additional support for these observations comes from studies by Beggiato et al. (2017), which document the frequent underdiagnosis of females compared to males due to gender-biased diagnostic criteria and tools developed from predominantly male samples. These results further suggest the need for gender-sensitive diagnostic tools that consider the internalized and camouflaged nature of ASD in females. Without such tools, females will continue to be overlooked, leading to delayed interventions and less favorable developmental outcomes.

3.2 Symptom Expression Differences Between Genders

The study found notable differences in how ASD symptoms manifest between males and females. Males with ASD often exhibit externalizing symptoms such as repetitive movements, hyperactivity, and overt communication challenges, aligning more closely with traditional diagnostic models (Wilson et al. 2016). In contrast, females frequently present with internalizing symptoms like anxiety, social withdrawal, and emotional dysregulation, which are less observable and often overlooked by clinicians (Wood-Downie et al. 2020). Additionally, the phenomenon of social camouflaging – where females mask their ASD-related challenges by mimicking neurotypical behaviors – further complicates diagnosis (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020). This masking can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis, with many females initially being diagnosed with mood or anxiety disorders rather than ASD. Figure 4 highlights these symptom differences, illustrating the tendency for males to exhibit more overt behaviors while females present with internalizing symptoms, emphasizing the need for revised diagnostic criteria that better capture female-specific presentations.

Symptom expression differences between males and females with ASD.

Figure 4 highlights the key differences in symptom expression between genders, comparing externalizing behaviors in males with internalizing behaviors in females. The figure shows that males are more likely to display overt behaviors such as repetitive movements and restricted interests, while females are more prone to exhibiting internalizing symptoms, which often lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

When compared to earlier research, these findings align with studies that have shown females are often diagnosed later in life, if at all, due to the subtler nature of their symptoms. Earlier work by Beggiato et al. (2017, p. 680) has similarly demonstrated that females with ASD tend to internalize their challenges, making them less visible to healthcare providers. The results from this study reinforce the importance of re-examining the diagnostic criteria used for ASD, particularly for females, who may not meet the thresholds based on male-dominated models.

This pattern of gender-specific symptom expression has critical implications for both diagnosis and treatment. Males, whose symptoms are more readily identifiable, are often diagnosed at a younger age and can access early intervention services. In contrast, females may not receive a diagnosis until much later in life, which can lead to missed opportunities for early intervention – a critical factor in improving long-term outcomes. Research shows that early intervention in ASD, such as therapies initiated during childhood, often leads to significant improvements in social communication, behavior regulation, and overall adaptive functioning (Fernell et al. 2011; Rogers et al. 2020). In contrast, later interventions, while still beneficial, typically show less pronounced gains, as the neural plasticity that characterizes early development diminishes over time (Harrop et al. 2019). Delayed diagnosis often results in females missing out on crucial early support, which can exacerbate challenges related to social integration, emotional regulation, and mental health stability as they progress into adolescence and adulthood.

3.3 Gender Representation in ASD Research

A systematic review of the literature reveals a pronounced gender imbalance in the samples used in ASD research, with males overrepresented in both systematic reviews and empirical studies. This overrepresentation leads to findings that are biased toward the male presentation of ASD, potentially overlooking key aspects of how ASD manifests in females (Lai et al. 2011).

Figure 5 illustrates the gender distribution of participants in ASD studies conducted over the past decade. The figure shows that males consistently make up a majority of study participants, with females representing a much smaller proportion. This underrepresentation of females skews the research findings and limits the generalizability of the results to the entire ASD population.

Gender distribution in ASD studies (2011–2024).

The implications of this imbalance are significant. When research studies primarily focus on males, the resulting diagnostic tools, treatment protocols, and interventions are optimized for male symptoms, which tend to be more externalizing. As a result, females, whose symptoms are often more internalizing, may not benefit from these tools to the same extent. Previous research has also indicated that interventions developed with male-dominated samples may not be as effective for females due to differences in symptom presentation and response to treatment (Smith, White, and Wolfe 2018).

The study represented in Figure 5 that features a female-dominated sample offers unique insights into ASD diagnosis, interventions, and outcomes compared to the predominantly male-oriented studies within the literature. This study specifically focused on identifying and addressing the nuances of social camouflaging behaviors and internalized symptoms common in females with ASD. Unlike more behaviorally focused studies that often prioritize externalized traits seen in males, this research employed tools sensitive to emotional regulation and adaptive social communication skills.

In terms of diagnosis, the study highlighted how traditional tools, such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), may overlook subtler female ASD presentations and instead utilized qualitative assessments, including in-depth interviews and case studies, to capture internalized symptomatology. For interventions, it evaluated the effectiveness of gender-sensitive therapies, emphasizing emotional regulation and social adaptation over standard methods like Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), which showed limited success for female participants in this sample. Outcomes demonstrated that tailored interventions led to greater improvements in social communication and reduced anxiety symptoms over a longitudinal follow-up period compared to traditional treatment approaches.

Addressing this imbalance requires a concerted effort to include more females in ASD research. By doing so, researchers can ensure that diagnostic and treatment approaches are effective for both genders, leading to better overall outcomes for individuals with ASD.

3.4 Gender Differences in the Effectiveness of ASD Interventions

The effectiveness of ASD interventions varies significantly by gender. Traditional methods, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), often yield more pronounced improvements in males due to their focus on externalizing behaviors. Conversely, females with ASD tend to exhibit internalized symptoms, including anxiety and social camouflaging, which necessitate alternative therapeutic strategies emphasizing emotional regulation and adaptive social communication.

Gender-sensitive interventions that evolve over time show promise for females, particularly during critical life transitions like adolescence and adulthood, when treatment needs may fluctuate (Harrop et al. 2019; Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020). Tailored approaches focusing on social camouflaging behaviors and individualized support strategies can better address the unique challenges faced by females with ASD, thereby improving long-term outcomes. Figure 6 illustrates these gender disparities, highlighting the need for flexible, adaptive interventions that accommodate distinct symptom profiles and evolving developmental needs.

Comparative effectiveness of different ASD interventions by gender.

Figure 6 shows that males tend to respond better to traditional interventions such as ABA, with success rates of approximately 75 %. In contrast, the effectiveness of ABA for females is lower, with success rates closer to 55 %. The figure also shows a gender disparity in the effectiveness of CBT, with males responding more favorably to this intervention as well.

The gender differences in treatment response suggest that standard ASD interventions, which were primarily developed based on male populations, may not fully address the unique needs of females with ASD. For instance, ABA focuses on reinforcing desired behaviors, which may be more effective for addressing the externalizing symptoms typically seen in males. However, this approach may not be as effective for females, who often experience more internalizing symptoms like anxiety and depression, which ABA is not designed to target (Zhang et al. 2020, p. 2).

These findings are consistent with earlier research, which has indicated that females with ASD may benefit more from interventions that focus on emotional regulation and social communication skills. By tailoring interventions to address these areas, clinicians may be able to improve treatment outcomes for females.

To ensure clarity for the terms used in Figure 6, we have provided explanations for key abbreviations shown on the X-axis. RCT refers to Randomized Controlled Trials, a gold-standard method for clinical interventions; PNS denotes Prospective Naturalistic Studies, which track participants in real-world settings; and RCS indicates Retrospective Chart Studies, focusing on the analysis of existing clinical records. These distinctions help contextualize the various methodologies used to evaluate intervention effectiveness for ASD.

The gender differences in treatment response are closely tied to the effectiveness of common ASD interventions. While Figure 6 illustrates the comparative effectiveness of interventions like Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) across genders, it is important to clarify that ’effectiveness’ here refers to measurable outcomes such as symptom improvement, behavioral adaptation, and social skill acquisition. ‘Response to treatment,’ on the other hand, considers individual variability in how participants engage with or react to these interventions. For instance, males often exhibit more observable changes in behavior with ABA, while females may show less pronounced changes due to their internalized symptoms (Zhang et al. 2020). This highlights that while an intervention may be deemed ‘effective’ in achieving certain outcomes, the pathway to these outcomes and participant experiences of intervention differs significantly across genders.

While standard ASD interventions like Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) are effective for addressing externalizing symptoms, they often fail to address the internalized challenges and adaptive needs of females. Females with ASD frequently present with heightened anxiety and social avoidance behaviors, which necessitate gender-sensitive interventions emphasizing emotional regulation and adaptive social communication skills (Barbaro and Freeman 2021; Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020).

For instance, a 16-year-old female diagnosed with ASD exhibited pronounced anxiety in social contexts and avoided interactions with peers due to excessive worry and an inability to manage emotional triggers. To address these challenges, a tailored intervention plan was implemented. The approach included cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which is widely recognized for its efficacy in managing anxiety (Harrop et al. 2019), to help the individual identify and regulate emotional triggers. Additionally, mindfulness techniques, such as deep breathing, were introduced to provide immediate coping strategies during stressful situations (Adams et al. 2018).

To further enhance her social communication skills, group sessions were designed incorporating role-playing exercises that simulated typical social scenarios, such as participating in school gatherings. These simulations aimed to improve her ability to interact confidently with peers and navigate social environments effectively (Harrop et al. 2019; Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020). Collaboration with key stakeholders, including her parents and teachers, was integral to the intervention’s success, ensuring strategies were reinforced across home and school contexts. As a result, the patient experienced a significant reduction in social anxiety, reported improved self-confidence, and successfully established meaningful peer relationships. As a result, the patient experienced a significant reduction in social anxiety, reported improved self-confidence, and successfully established meaningful peer relationships.

This example illustrates how gender-sensitive strategies, such as integrating emotional regulation training and adaptive social skill development, can address the specific needs of females with ASD. These approaches fill critical gaps left by traditional interventions like ABA, which often overlook internalized symptoms more commonly observed in females (Barbaro and Freeman 2021; Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020).

3.5 Long-Term Effectiveness of ASD Interventions by Gender

The study examined the long-term effectiveness of ASD interventions for both males and females. The results indicate that while males often maintain the benefits of early interventions, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), over time, females tend to experience variability in treatment effectiveness, particularly in areas related to social communication and emotional regulation (McVey et al. 2017, p. 1020). Figure 7 shows that the trend in long-term effectiveness for females is characterized by fluctuations rather than a consistent decline. This variability suggests that different intervention strategies may yield varying levels of sustained impact for females with ASD. Factors such as transitions in life stages, access to sustained support, and the adaptability of interventions may contribute to this observed pattern. These findings underscore the need for flexible, individualized approaches that can evolve to meet the changing needs of females with ASD.

Long-term effectiveness of ASD interventions by gender.

Figure 7 illustrates the long-term effectiveness of various ASD interventions by comparing outcomes across genders. The data show that males generally retain their progress following early interventions, while females often experience a reduction in effectiveness during critical transitions, such as adolescence and adulthood (Harrop et al. 2019, p. 1736). This observed pattern emphasizes the necessity for adaptive intervention strategies that address the evolving needs of females across different life stages.

Previous research supports the importance of ongoing support for females with ASD, particularly in areas such as emotional regulation and social communication, as they transition through different life stages (Harrop et al. 2019, p. 740). Although Figure 7 does not explicitly depict ongoing support, its representation of fluctuating long-term effectiveness suggests a potential need for sustained and adaptable strategies. By tailoring intervention approaches to align with developmental changes, clinicians can better address the unique needs of females with ASD.

To enhance reader comprehension, key abbreviations on the X-axis of Figure 7 have been defined. RCT denotes Randomized Controlled Trials, considered the gold standard for clinical research due to their ability to minimize bias. PNS refers to Prospective Naturalistic Studies, which track participants in real-world settings without experimental manipulation. RCS stands for Retrospective Chart Studies, which analyze existing patient records to evaluate treatment outcomes. This distinction provides valuable context for interpreting the methodologies used in assessing long-term effectiveness in ASD interventions.

Among individuals with ASD, females often encounter distinct and under-addressed challenges during the transition to adulthood. These challenges are particularly evident in professional and workplace settings, where traditional ASD interventions may fail to adequately equip individuals for the complex demands of employment over time. A 25-year-old female patient with ASD serves as a compelling example of these issues. While she exhibited strong technical skills and a passion for graphic design, she struggled to secure stable employment due to persistent difficulties in teamwork and adapting to workplace dynamics. These barriers included an inability to effectively process constructive feedback and resolve interpersonal conflicts in collaborative environments, challenges that persisted well into her adult years (Adams et al. 2018).

To address these long-standing difficulties, a targeted intervention plan was implemented, reflecting the need for adaptive strategies that evolve to meet the changing needs of females with ASD. The first component focused on skill enhancement through specialized graphic design training, helping the patient refine her technical expertise and build professional confidence (Harrop et al. 2019). The second component involved workplace adaptation training, featuring role-playing scenarios to simulate team-based environments. These exercises emphasized essential workplace skills, such as managing feedback, conflict resolution, and effective communication with colleagues (Adams et al. 2018; Harrop et al. 2019).

The outcomes of this intervention extended beyond immediate success. The patient not only secured a position in the design industry but also demonstrated a sustained ability to collaborate within a team and navigate workplace dynamics effectively. This progress highlights the critical importance of vocational programs that incorporate gender-sensitive, long-term strategies. By addressing both professional development and interpersonal challenges, these programs fill a significant gap left by standard interventions, which often overlook the evolving needs of females as they transition into adulthood.

This example underscores that long-term effectiveness in ASD interventions requires a flexible and adaptive approach that accommodates developmental changes and life transitions. Vocational training tailored to the unique needs of females with ASD plays a pivotal role in ensuring sustained success in adulthood. These findings align with broader discussions in this section, emphasizing the necessity of individualized support frameworks that can adapt to the changing demands of life stages (Harrop et al. 2019).

3.6 Challenges in Implementing Gender-Sensitive Interventions

The development and implementation of gender-sensitive interventions for ASD face numerous challenges, as highlighted in the literature. Figure 8 outlines these challenges, which include data insufficiency (40 %), gender bias in diagnostic tools and treatment approaches (30 %), cultural barriers (20 %), and a lack of policy support (10 %).

Challenges in implementing gender-sensitive interventions.

One of the primary challenges stems from data insufficiency due to the overrepresentation of males in ASD research. This skews outcomes and limits the understanding of how interventions impact females. The existing literature on ASD interventions predominantly focuses on male participants, resulting in a lack of gender-balanced data needed for developing tailored interventions for females. This data gap is exacerbated by the scarcity of long-term studies on females with ASD, making it difficult to understand how interventions perform across different life stages (Beggiato et al. 2017; Harrop et al. 2019).

Gender-biased diagnostic tools also pose a significant challenge. Many diagnostic tools for ASD were developed based on predominantly male samples, which overlook subtler, internalizing symptoms that are more common in females, such as social camouflaging and heightened anxiety (Navarro-Pardo, García-Sanjuán, and Real-Fernández 2021). As a result, females often receive delayed or incorrect diagnoses, limiting their access to early intervention (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020). Even effective interventions for males, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), may not achieve comparable results for females due to differences in symptom presentation (Harrop et al. 2019).

Cultural barriers further complicate the diagnosis and treatment of females with ASD. In many societies, gender stereotypes and expectations can lead to the misinterpretation of ASD symptoms as typical shyness or social anxiety in females (Wood-Downie et al. 2020). This can prevent accurate diagnosis and access to appropriate interventions. Clinical settings may also lack cultural awareness, contributing to the under-recognition of ASD in females due to their ability to mask symptoms and display higher social functioning.

Policy support for gender-sensitive interventions remains limited, hindering resources for exploring gender-specific approaches to ASD diagnosis and treatment. Without strong policy initiatives aimed at promoting gender equity in ASD research and clinical practice, it is challenging to develop tailored interventions that address the unique needs of females with ASD.

The variability in treatment effectiveness for females can be attributed to factors such as social camouflaging and differences in symptom presentation, which impact diagnosis and long-term outcomes. Females with ASD often exhibit superficially better social skills, masking underlying issues and resulting in under-recognition and inadequate support (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020; Wood-Downie et al. 2020). Continuous, tailored support is crucial to address the evolving needs of females throughout their developmental trajectory (Harrop et al. 2019).

Low social awareness of ASD in females, estimated at approximately 10 %, remains a significant barrier to effective diagnosis and intervention. Increasing community and clinical awareness is essential to better recognize and support females who may mask or internalize their symptoms.

3.7 Gender Distribution in ASD Intervention Studies

This section highlights the unique challenges faced by females with ASD in the context of diagnosis and treatment. Research consistently demonstrates that females with ASD often present with subtler, more internalized symptoms, such as social camouflaging and heightened emotional regulation difficulties, which contribute to underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis compared to males. For example, social camouflaging, where females mask their ASD traits to blend in socially, frequently results in delayed diagnoses and diminished access to tailored interventions (Halladay et al. 2015).

Figure 9 outlines key challenges in developing effective gender-sensitive treatments, including gender-biased diagnostic criteria and limited representation of females in ASD studies, leading to male-centric treatment models (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020). The lack of female-specific intervention strategies underscores the need for tailored approaches that better address internalizing symptoms, social camouflaging, and co-occurring health conditions among females with ASD (Harrop et al. 2019). By understanding these gender-specific differences and incorporating them into diagnosis and treatment frameworks, clinicians can ensure more effective care for females with ASD.

Gender representation in ASD intervention studies (2011–2024).

Figure 9 highlights the significant underrepresentation of female ASD patients in studies that inform current diagnostic practices. This disparity exacerbates the diagnostic challenges faced by females, as the limited research on female-specific ASD symptoms continues to skew diagnostic tools toward identifying male-pattern behaviors. As illustrated, between 2011 and 2024, male subjects made up the overwhelming majority of participants in ASD intervention studies, which has led to a knowledge gap in the accurate identification and treatment of females with ASD.

In addition, sociocultural factors play a critical role in the higher rates of misdiagnosis among female ASD patients. In many traditional cultures, females are expected to exhibit compliant and mild-mannered behaviors, which can lead to social withdrawal and other symptoms being overlooked by family members or educators. Based on these findings, it is essential to revise diagnostic tools and standards, especially to develop gender-sensitive diagnostic instruments that can detect internalizing symptoms and camouflaging behaviors in females. This need has been echoed in numerous studies (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020, p. 311), calling for revisions to existing diagnostic frameworks to accommodate gender-specific manifestations of ASD.

Moreover, our research shows that social camouflaging in females is a significant factor that leads to missed or delayed diagnoses. Females are often adept at mimicking socially acceptable behaviors, hiding their social deficits, which makes it harder for caregivers and professionals to identify their true challenges. This supports the growing body of evidence that calls for the creation of diagnostic tools tailored to detect camouflaging behaviors and subtle signs of distress that are more common in females than in males (Zhang et al. 2020, p. 2). Without such adaptations, females are likely to continue being underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, which can lead to delayed access to necessary interventions.

In conclusion, gender-specific diagnostic challenges arise primarily from the male-centric design of current diagnostic tools and the sociocultural expectations placed on females. To address these disparities, diagnostic criteria must evolve to better reflect the internalizing and camouflaging symptoms often seen in females with ASD. This will ensure that females receive timely and accurate diagnoses, which are crucial for effective early intervention and support.

3.8 Meta-Analysis Data and Statistics on Gender Differences in ASD

The meta-analysis conducted on gender differences in ASD revealed several key findings and statistical metrics that offer a comprehensive understanding of the effects and variability observed across studies. Fixed effect size was calculated as 0.5386 (95 % CI), suggesting a relatively stable gender effect assuming no variation across studies. However, the random effect size was slightly lower at 0.4809 (95 % CI), reflecting variability due to differences in study design, sample characteristics, and methodologies. The heterogeneity test (Q statistic) yielded a value of 26.5724 (p-value = 0.0016), indicating significant heterogeneity among the studies, with a high I 2 value of 66.13 %, showing that most of the observed variability is not due to chance alone.

Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression test, yielding a significant intercept value of 0.70 (p = 0.0027), indicating potential bias. The funnel plot asymmetry further supports the presence of publication bias, suggesting that studies with non-significant or negative results may be underrepresented in the literature. Subgroup and moderator analyses were performed to explore sources of heterogeneity, showing that empirical studies had a higher average gender effect size (0.60) compared to review and analysis-type studies (0.50). This finding implies that empirical data collection methods may more sensitively capture gender differences in ASD.

This figure shows the distribution of effect sizes for gender differences in autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Each study has its own effect size (blue dots) and its confidence interval (horizontal gray line). The overall mean effect size is indicated by the red dashed line at approximately 0.50, showing the effect of gender in ASD. The effect sizes in the graph fluctuate close to or around the average effect size, indicating a relative concentration of effect sizes across studies.

Building on the statistical findings presented in Table 2, the observed fixed and random effect sizes highlight not only the significance of gender differences in ASD but also the limitations imposed by variability in research methodologies and study characteristics. This disparity between fixed and random effect sizes, while modest, underscores the importance of considering study-specific contexts when interpreting meta-analytic results. For instance, the variability captured by the random effects model suggests that while gender consistently influences ASD diagnosis and presentation, its magnitude may be moderated by factors such as geographic region, diagnostic tools employed, and sample demographics.

Summary of statistical metrics for gender differences in ASD.

| Statistic | Value | Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect size | 0.5386 | 95 % CI: 0.4901–0.5871 |

| Random effect size | 0.4809 | 95 % CI: 0.4215–0.5403 |

| Q statistic | 26.5724 | NA |

| I 2 value | 66.13 % | NA |

| Egger’s intercept | 0.70 (p = 0.0027) | 95 % CI: 0.32–0.76 |

-

Note: Confidence intervals are not typically calculated for Q Statistic and I 2 value. Fixed effect size and random effect size represent the effect sizes under the fixed-effect model and random-effect model, respectively. The Q statistic is used to evaluate heterogeneity across studies. The I 2 value indicates the percentage of heterogeneity (66.13 % represents moderate heterogeneity).

The heterogeneity indicated by the Q statistic (26.5724, p = 0.0016) and an I 2 value of 66.13 % reflects considerable inconsistency across studies, which is likely influenced by historical biases in ASD research. The prevailing understanding of ASD has been shaped by predominantly male samples and diagnostic criteria that emphasize externalizing symptoms. This inherent bias has often led to the underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis of females with ASD, as their symptomatology frequently includes internalized behaviors such as anxiety, which are not adequately captured by traditional diagnostic frameworks. Future research should adopt stratified analyses by gender and symptom type to mitigate this imbalance.

The significant Egger’s intercept (0.70, p = 0.0027) and associated funnel plot asymmetry point to a notable publication bias within the field. This bias is likely rooted in the preferential reporting of studies that demonstrate significant gender effects, potentially skewing the meta-analytic results toward an overemphasis on gender disparities. Such a bias not only distorts the understanding of ASD but also reinforces diagnostic stereotypes that may overlook the subtleties of gender-specific symptom presentation. Addressing this issue requires a shift toward inclusive publishing practices that value null and contradictory findings, which are essential for building a more balanced evidence base.

Empirical studies, with their higher average effect size (0.60) compared to review-based analyses (0.50), provide critical insights into gender differences in ASD. This disparity suggests that direct data collection methods, particularly those incorporating behavioral assessments or detailed symptom profiles, are more effective at capturing nuanced gender effects. By contrast, review-based methods are constrained by the quality and scope of their included studies, which may perpetuate existing biases and fail to account for the full spectrum of gender-related variability in ASD. These findings emphasize the need for future research to adopt more robust and inclusive empirical methodologies.

3.9 Meta-Analysis Data and Statistics on Gender Differences in ASD Interventions

This meta-analysis examined the impact of gender on the effectiveness of various ASD interventions. The fixed effect size was found to be 0.4789 (95 % CI), while the random effect size was lower at 0.4355 (95 % CI), accounting for study variability. The heterogeneity (Q statistic) was 73.9786 (p < 0.001), with a high I 2 value of 75.67 %, reflecting substantial variation among the studies analyzed.

The presence of publication bias was confirmed by Egger’s test, with a significant intercept value of 0.54 (p < 0.001). This suggests that studies showing smaller or non-significant gender differences in intervention effectiveness may be underreported. Subgroup analysis revealed that empirical studies had a lower effect size (0.38) compared to review-based studies (0.50), suggesting potential differences in methodological rigor and data integration.

The figure then shows the distribution of effect sizes across gender in the ASD intervention. The effect sizes and their confidence intervals for each study are labeled in the graph, and the overall mean effect size is identified by the red dashed line at approximately 0.50. Compared to Figure 10, the effect sizes in Figure 11 are more dispersed, with some effect sizes in particular below 0.40, suggesting that the effect of the intervention varied considerably between studies. This variation may reflect diversity in intervention methods, participant age groups, gender differences, etc.

Meta-analysis of gender differences in ASD (effect sizes).

Meta-analysis of ASD interventions by gender (effect sizes).

Building on the data presented in Table 3, the findings underscore critical insights into the nuanced impact of gender on ASD intervention outcomes. The fixed effect size of 0.4789 and the slightly lower random effect size of 0.4355 reflect not only the effectiveness of interventions but also highlight the variability introduced by study-specific factors. The considerable heterogeneity indicated by the Q statistic (73.9786, p < 0.001) and the high I 2 value of 75.67 % point to systemic differences in study design, participant demographics, and intervention methodologies as major contributors to this variability.

Summary of statistical metrics for gender differences in ASD interventions.

| Statistic | Value | Confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effect size | 0.4789 | 95 % CI: 0.4231–0.5347 |

| Random effect size | 0.4355 | 95 % CI: 0.3702–0.5008 |

| Q statistic | 73.9786 | NA |

| I 2 value | 75.67 % | NA |

| Egger’s intercept | 0.54 (p < 0.001) | 95 % CI: 0.45–0.95 |

-

Note: Confidence intervals are not typically calculated for Q statistic and I 2 value. Fixed effect size and random effect size represent the effect sizes under the fixed-effect model and random-effect model, respectively. The Q statistic is used to evaluate heterogeneity across studies, and its p-value indicates whether the heterogeneity is statistically significant. The I 2 value measures the percentage of heterogeneity (75.67 % indicates high heterogeneity). Egger’s intercept is used to assess publication bias (a significant p-value suggests potential bias). Confidence intervals are typically not calculated for the Q statistic and I 2 value.

The significant Egger’s intercept (0.54, p < 0.001) reveals a notable publication bias, indicating that studies with smaller or non-significant gender effects are underrepresented. This bias not only inflates the perceived overall effectiveness of interventions but also skews the understanding of gender-specific outcomes. Such distortion can have practical implications, as intervention designs may disproportionately favor outcomes more easily measurable or more prominently reported in male-dominated studies, further marginalizing the unique needs of females with ASD.

The subgroup analysis showing a lower average effect size in empirical studies (0.38) compared to review-based studies (0.50) is noteworthy. This suggests that direct, primary data collection methods may capture more nuanced and less amplified gender differences compared to reviews, which are often subject to selection biases in study inclusion. Empirical studies likely provide a more granular view of intervention effectiveness, particularly for underrepresented groups like females with ASD. This highlights the need for further empirical research using diverse and representative samples to better understand gender-specific intervention dynamics.

3.10 Importance of Research Methodology in Gender-Specific Findings

Research methodologies play a critical role in shaping the understanding of gender differences in ASD diagnosis and intervention. Traditional research methodologies, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), often prioritize measurable, externalized behaviors more commonly observed in males, inadvertently marginalizing the experiences of females with ASD. Our study, along with previous research (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020, p. 311), underscores the need for research designs that incorporate more gender-sensitive approaches, particularly those that capture the internalizing symptoms and social camouflaging behaviors frequently exhibited by females.

For example, observational and longitudinal studies provide more nuanced insights into the developmental trajectories of females with ASD, which are often overlooked in short-term, behavior-focused studies. Such methodologies allow researchers to track changes in emotional regulation, social adaptation, and camouflaging behaviors over time, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how ASD manifests differently across genders. Our findings support this, as females in our study demonstrated a marked increase in social camouflaging behaviors during adolescence, which standard behavioral studies would likely fail to capture.

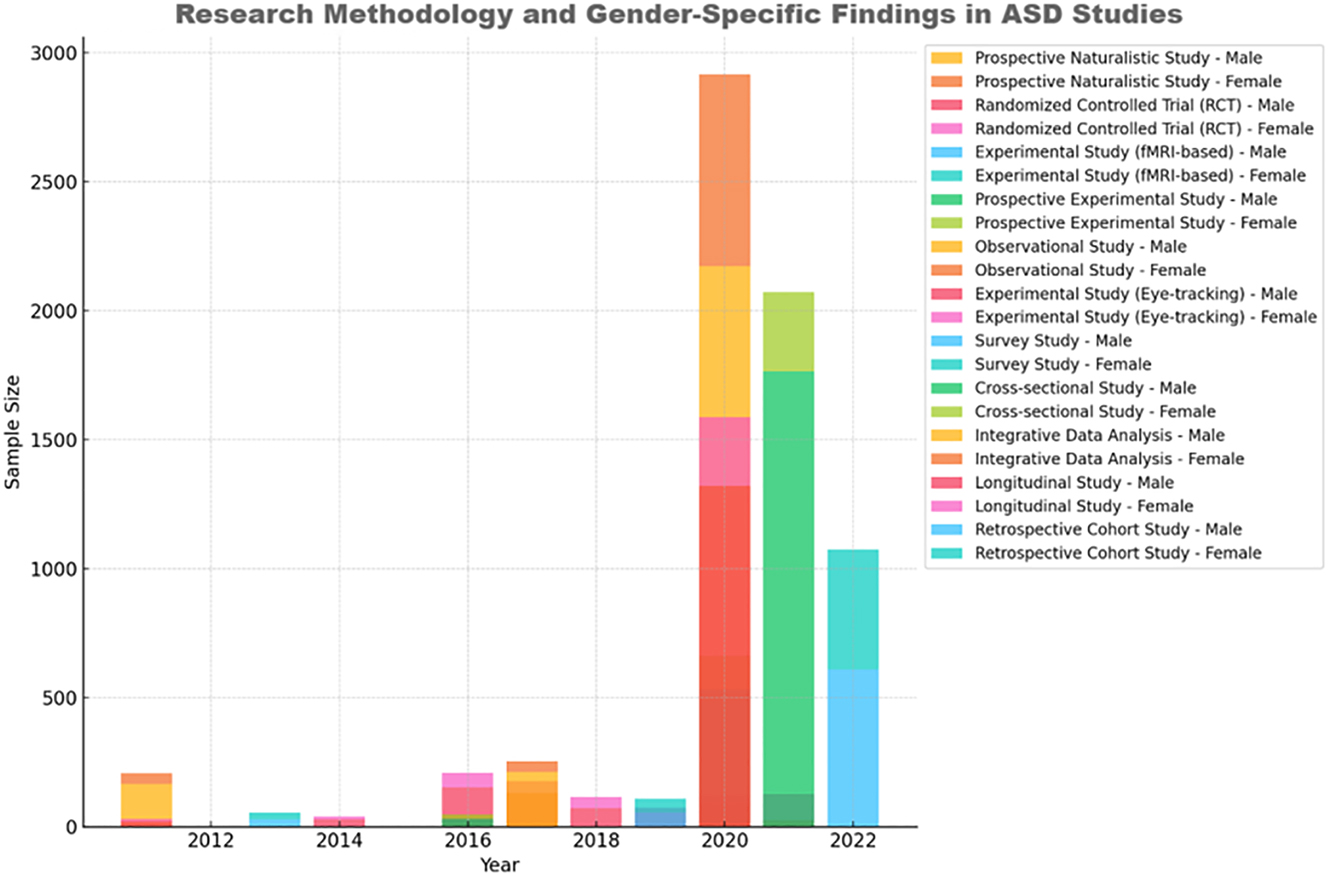

Figure 12 highlights the gender imbalances in research methodologies commonly employed in ASD studies. As the figure shows, RCTs and short-term behavior interventions dominate the research landscape, with relatively few studies adopting methodologies that account for internalizing symptoms and gender-specific developmental changes. This methodological bias leads to underdiagnosis and inadequate intervention strategies for females, perpetuating the cycle of misdiagnosis and delayed treatment.

Research methodology and gender-specific findings in ASD research.

Moreover, our study reveals that female-specific ASD symptoms are often better captured through qualitative methods, such as interviews and case studies, which provide deeper insights into the lived experiences of female patients. This is corroborated by existing literature, which emphasizes the value of mixed-method approaches in understanding gender differences in ASD (Zhang et al. 2020, p. 2). By incorporating qualitative data alongside quantitative measures, researchers can better understand the complexities of female ASD presentations, including emotional regulation, social camouflaging, and anxiety management.

Our findings also suggest that future research should employ a greater variety of tools to measure both internalizing and externalizing behaviors in ASD patients. For example, diagnostic assessments that include emotional regulation and social interaction scales, rather than solely focusing on repetitive behaviors and communication deficits, would better reflect the challenges faced by females. Additionally, methodologies that examine the long-term impacts of interventions, rather than short-term behavior changes, are crucial for understanding how females with ASD progress over time.

In conclusion, the choice of research methodology significantly influences the findings related to gender differences in ASD. Methodologies that prioritize externalized behaviors and short-term outcomes disproportionately benefit male patients, while internalizing symptoms common in females remain underexplored. Our study, in line with existing literature, highlights the need for more gender-sensitive research approaches, particularly those that integrate both qualitative and quantitative methods to capture the full spectrum of ASD experiences across genders.

4 Discussion and Recommendations

This section builds on the findings presented in Section 3, providing a deeper examination of gender-specific responses to ASD interventions. While males often exhibit greater improvements with behavior-focused interventions, females benefit from therapies that target social communication and emotional regulation. This underscores the importance of adapting traditional approaches to meet the unique needs of females. Recent evidence also highlights the role of long-term, flexible interventions tailored to female-specific challenges (Harrop et al. 2019).

4.1 Diagnostic Disparities and Gender Bias

A central finding of this study is the persistent gender disparities in the diagnosis of ASD. Although shifts in diagnostic ratios (from 4:1 to about 3:1) reflect growing recognition of ASD presentations in females, existing diagnostic tools, like ADOS and ADI-R, continue to be influenced by male-centric symptomatology. The challenge lies in how these tools primarily capture externalizing behaviors – observable traits such as repetitive movements and social communication issues – thereby overlooking the subtler, internalized symptoms commonly exhibited by females (Hull, Petrides, and Mandy 2020, p. 310).

A key implication of this study is the need for diagnostic criteria that better incorporate the internalized, less visible ASD traits frequently observed in females. The phenomenon of social camouflaging – where females adapt behaviors to mask ASD traits – adds further complexity to timely diagnosis. This behavior reflects not only a personal coping mechanism but also an adaptive response to societal expectations, making it crucial for clinicians to recognize camouflaging as part of the diagnostic assessment for ASD.

The consistent diagnostic bias across recent studies underscores a pressing need for advancements in gender-sensitive diagnostic tools, which would better accommodate the unique presentations of ASD in females. The need for gender-sensitive diagnostic tools is crucial, without incorporating these behaviors into the diagnostic process, many females will continue to be overlooked.

4.2 Symptom Expression and Gender Differences

The gender-specific differences in ASD symptom expression revealed in this study underscore the urgent need to reevaluate diagnostic practices. While males typically display externalizing symptoms like repetitive movements and hyperactivity that align with traditional diagnostic frameworks, females frequently present with subtler, internalizing symptoms such as anxiety and social withdrawal. These findings align with the broader literature (Wood-Downie et al. 2020) and further illuminate how the conventional diagnostic focus on observable behaviors contributes to the underdiagnosis of ASD in females.

This discrepancy has profound implications for both diagnosis and intervention, emphasizing the need for gender-sensitive diagnostic tools that account for the unique manifestations of ASD in females. As illustrated by our findings, the phenomenon of social camouflaging complicates early identification, often delaying necessary support until later in life. Addressing this diagnostic gap requires integrating awareness of camouflaging behaviors into assessment frameworks to enhance the early detection and treatment of ASD in females.

The persistence of these diagnostic challenges highlights the importance of refining ASD criteria to capture the broader spectrum of symptoms across genders. Without such adjustments, females with ASD may continue to experience delayed diagnoses, missing crucial early intervention opportunities known to improve long-term outcomes (Fernell et al. 2011; Harrop et al. 2019). Moving forward, clinicians should be trained to recognize and evaluate both internalizing symptoms and camouflaging behaviors to ensure that diagnostic assessments are inclusive and gender-responsive.

4.3 Gender Representation in ASD Research

The current male bias in ASD research samples has not only shaped diagnostic tools and intervention strategies but also reinforced systemic gaps in understanding how ASD presents across genders. To move beyond recognition of this imbalance, ASD research must adopt transformative, gender-inclusive methodologies that actively address the unique needs of females with ASD. This approach requires more than increasing the number of female participants; it necessitates reshaping study designs, data collection methods, and analytical frameworks to capture the subtle, internalizing symptoms prevalent among females.

Traditional diagnostic assessments such as ADOS and ADI-R, structured around externalizing behaviors, may inadvertently obscure the complexities of ASD in females. Studies can overcome this limitation by integrating qualitative methods, such as in-depth interviews and longitudinal case studies, to observe social camouflaging and internalized symptoms over time. Using mixed-methods designs and nontraditional metrics could reveal symptom trajectories and behavioral adaptations that quantitative measures alone might miss.

Current research typically applies the same diagnostic thresholds and symptomatology criteria across genders, often overlooking how social and cultural expectations might influence ASD presentations. Future studies could adopt gender-sensitive analysis models that adjust for these influences, potentially redefining diagnostic criteria and enabling early intervention strategies that are responsive to gender-specific needs.

The male-centric bias in research has also resulted in a limited view of effective interventions. To address the developmental needs of females with ASD, researchers should explore alternative therapeutic approaches that prioritize emotional regulation, social adaptation, and support for transitions, particularly in adolescence and early adulthood. Experimental designs that compare traditional therapies with gender-sensitive interventions could inform more nuanced and effective treatment protocols, setting new standards for clinical practice.

Ultimately, addressing gender imbalance in ASD research requires a paradigm shift from merely including more female participants to fundamentally rethinking research questions, methodologies, and intervention strategies. By developing gender-sensitive frameworks, ASD research can more accurately reflect the lived experiences of all individuals with ASD, supporting tailored diagnostic and intervention approaches that improve long-term outcomes.

4.4 Intervention Effectiveness by Gender

A core finding of this study is the differential impact of ASD interventions by gender, suggesting that existing treatments may inadequately address the unique developmental needs of females with ASD. While interventions like Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) have shown substantial efficacy in males, these approaches often prioritize externalizing behaviors, which are less characteristic of female ASD presentations. The emphasis on observable behaviors such as repetitive actions and social interaction skills inherently limits the responsiveness of females, whose symptoms often involve more internalized expressions, such as anxiety and social camouflaging (McVey et al. 2017).

Traditional interventions have limitations. Figure 6 demonstrates that females generally exhibit less improvement with ABA, particularly as they transition through developmental stages. This phenomenon aligns with Harrop et al. (2019), who noted that symptom complexity in females often demands evolving support structures, which standard approaches like ABA or CBT may not provide. The rigid structure of ABA, which focuses on behavior reinforcement, may be insufficient for females whose symptoms require nuanced, adaptive strategies that can address underlying emotional and social challenges.

The results suggest a pressing need for gender-sensitive adaptations within ASD treatments. Specifically, interventions for females should incorporate strategies that target emotional regulation, adaptive social communication, and stress management. For instance, CBT can be modified to address social anxiety and internalized behaviors directly rather than focusing predominantly on external actions. Tailoring these interventions to focus on aspects like self-identity, resilience, and social camouflaging techniques could offer long-term benefits, particularly during adolescence, when social pressures intensify and symptoms may worsen.

Current research trends, including Zhang et al. (2020), advocate for a more flexible approach to ASD treatment that allows for adjustments based on symptom evolution rather than maintaining a one-size-fits-all model. This study supports this direction, suggesting that treatment effectiveness is not solely determined by the intervention itself but also by its adaptability to meet individual needs, especially for females who display less typical ASD characteristics. The potential for therapies that integrate cognitive and emotional elements with behavioral modifications could represent a significant shift in addressing gender-specific outcomes.

To improve the efficacy of ASD interventions for females, future research must establish frameworks that account for symptom diversity across genders. This involves developing therapies that do not just measure success through behavioral change but also through improved emotional stability and social integration. Furthermore, longitudinal studies examining how females respond to adapted interventions across life stages could yield insights into the mechanisms that support long-term resilience in ASD.

4.5 Challenges in Implementing Gender-Sensitive Interventions

The path to implementing gender-sensitive interventions for ASD is impeded by complex systemic and cultural challenges. A persistent barrier is the entrenched gender imbalance in ASD research, which overwhelmingly centers on male presentations of ASD. This male-focused approach constrains the scope and efficacy of intervention protocols, leaving gaps in our understanding of the nuanced needs of females with ASD, particularly regarding internalized symptoms like social camouflaging and emotional dysregulation.

Beyond research limitations, cultural norms around gendered behavior often obscure ASD symptoms in females, leading to frequent misinterpretation and dismissal of these signs as socially expected traits, such as shyness or reserved demeanor. This societal lens not only delays diagnosis but also restricts access to timely, effective interventions for females. For example, behaviors like social withdrawal are often normalized as feminine, rather than recognized as potential indicators of ASD, which reinforces systemic underdiagnosis and ineffective early intervention pathways (Wood-Downie et al. 2020).

Addressing these barriers calls for a two-pronged approach. First, there is a critical need for expansive, gender-balanced data that can inform evidence-based, female-centered interventions. Research frameworks must evolve to capture the diverse presentations of ASD across genders, shedding light on female-specific symptom patterns and responses to intervention. Second, clinicians require targeted training to better recognize and respond to subtle ASD symptoms in females. This would include incorporating tools and frameworks sensitive to internalized and camouflaged symptoms, empowering clinicians to make more accurate, timely diagnoses.

Ultimately, overcoming these barriers will require structural policy reforms that prioritize gender equity in ASD research and clinical practice. Policies should advocate for resource allocation toward gender-sensitive training, research funding specifically for female ASD presentations, and development of diagnostic tools that reflect the broad spectrum of ASD across genders. These changes could lead to a more inclusive, accurate approach to ASD treatment and, importantly, foster better long-term outcomes for females with ASD.

4.6 Gender Differences in Long-Term Outcomes

Long-term intervention effectiveness for females with ASD often varies significantly compared to males, especially as females face distinct social pressures and developmental transitions. While early interventions like ABA and CBT may offer initial benefits, females often experience diminished effectiveness over time, particularly during adolescence and adulthood, when social expectations intensify. This underscores the necessity for interventions that are not only flexible but can evolve to support these life-stage transitions.

An adaptive, lifespan-oriented approach to interventions – emphasizing skills like emotional resilience, adaptive communication, and social integration – is essential for maintaining progress. Research has increasingly recognized that females may require ongoing support structures that adjust to their changing needs across life stages. This perspective highlights a gap in current intervention models and points to a critical need for policies and resources that prioritize gender-responsive, long-term care planning.

4.7 Meta-Analysis Results and Discussion on Gender Differences in ASD Research