Abstract

We examine the contributions Congress makes to problem solving in contemporary American government. We offer a more positive assessment of the institution than is the norm for political science. In terms of representation, institutional processes, and policy outcomes, the polarized Congress has underappreciated virtues. Congress’s membership and party composition do a credible job reflecting the political diversity that exists in the country, and its institutional processes show respect for that diversity. Congress’s policy outcomes typically command broad support across party lines. Amid the intense polarization of contemporary American politics, the contemporary Congress enacts as much or more legislation by sheer volume than it did in the 1980s and the 1990s, and it normally does so in ways that large majorities and both parties support.

“‘The failure of Congress’ is a hoary theme that for years has been propounded by academics in textbooks and from lecture platforms. The general impression among academics [is] that ‘something ought to be done about Congress.’”

Roger H. Davidson, David M. Kovenock, and Michael Kent O’Leary (1966, 39).

The contributions Congress makes to problem solving in American government have long been underappreciated in political science. “Something ought to be done about Congress” has been a constant theme of the discipline across the decades since the wry observation of Davidson et al. (1966, 39). In reply to the critics, we argue that the contemporary Congress has underappreciated virtues in terms of representation, institutional processes, and policy outcomes. Its membership and party composition do a credible job reflecting the political diversity that exists in the country, and its institutional processes show respect for that diversity as laws are made.

But most importantly, Congress often finds a way to enact win-win, positive-sum outcomes that address concerns of both parties. Even amid the intense polarization of contemporary American politics, Congress still does engage in problem solving and, in the process, tends to arrive at results that large majorities support. Our research shows that majority parties more often succeed at enacting their agenda priorities by co-opting the minority party, rather than by steamrolling it. When it comes to policymaking, Congress usually operates more as an impediment to partisanship than as a facilitator of it. The difficulty of legislating does not mean constant gridlock. Even though polarization always threatens paralysis, we lack evidence that the contemporary Congress legislates less than it did in the past.

Broad bipartisan agreement, of course, is no guarantee that a policy is well designed or effective. Assessing Congress’s problem-solving capacity requires considering both procedural criteria – whether or not lawmakers make serious, good-faith efforts to address public problems – and outcome criteria – whether or not those efforts succeed. Other contributions to this special issue, including those by Anzia (2025) and Jones (2025), offer guidance on outcome-based evaluations. Understanding whether public policies are actually solving the problems they target is valuable, indeed necessary. Yet it is enormously difficult to develop standards by which one can assess Congress as an institution using such approaches.

The policy challenges facing Congress are highly complex and must often be evaluated across long time horizons. Consider climate change: addressing the challenge demands sustained legislative action, yet determining whether any particular policy approach is effective requires looking decades into the future. The same is true for many issues – education reforms aimed at improving student learning, public-health interventions, or efforts to strengthen the workforce and promote economic growth. Policy assessments must inevitably be made according to values, which are often contested. Value judgments are also involved in choosing the specific set of issues on which to evaluate Congress’s performance. It is also challenging to weigh Congress’s record on one set of issues against another so as to develop an overall assessment of the institution’s performance generally.

It is undoubtedly easier to assess Congress on procedural criteria. Here we take stock of the degree to which Congress is working on problems, reflects the political diversity that exists in the country as it does so, and whether it is able to build broad support behind the legislation it enacts. On these dimensions, we argue that Congress plays a more constructive political role in our divisive contemporary politics than is generally appreciated. We closely consider two important recent enactments that achieved bipartisan consensus despite high levels of initial disagreement (the CARES Act of 2020 and the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act of 2022). We then contrast those with two enactments that involved no bipartisan consensus-building (the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and the One Big Beautiful Bill Act of 2025). The contrast highlights the value of Congress’s normal approach as valuable for problem-solving, conflict resolution, and policy stability.

1 Scholarly Portraits of Congress

Scholars routinely describe Congress as a “dysfunctional” institution. There is not much academic debate about this characterization. It often appears as a taken-for-granted fact, even in empirical scholarship not attempting to offer a normative account of what a legislature should do or why Congress fails at it.

The bill of particulars against Congress is lengthy. It is intensely polarized (McCarty 2019), rigidly partisan (Smith 2014), gridlocked (Binder 2003), captured by narrow interests (Hall and Wayman 1990; Kalla and Broockman 2016), and parochial (Howell and Moe 2016). Although there is unquestionably truth in all these characterizations, the discipline’s negativity is rarely balanced by any positive considerations. Only a few scholars venture to suggest that Congress functions as a problem-solving institution (Adler and Wilkerson 2012; Mayhew 2017).

Many shortcomings are documented. The Senate is malapportioned by the standards of one person, one vote (Evans 2024; Lee and Oppenheimer 1999). Congress inadequately reflects the nation’s diversity in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, and class (Carnes 2013; Fisher 2020; Lawless and Fox 2010; Thomsen and King 2020). Both the House and Senate employ internal legislative processes that increasingly depart from regular order, undermining the benefits of expertise and committee division of labor (Curry 2015; Sinclair 2016).

Where policymaking is concerned, the most prominent models of legislative action portray lawmaking as a zero-sum contest, rather than a process of problem solving. The majority party seeks to amass a record of partisan accomplishments (Cox and McCubbins 2005, 7). To monopolize the credit, it legislates in ways that yield clear partisan winners and losers. Polarized parties provide their “legislative party institutions and party leadership stronger powers and greater resources” and encourage their party leaders to use those powers to “enact as much of the party’s program as possible” (Aldrich and Rohde 2000, 33–38).

Scholarship on legislative negotiations and bargaining also typically casts congressional action in a zero-sum light. Krehbiel’s (1998) “pivotal politics” model envisions negotiation as a process of adjusting policy along a continuum in which gains for the left are necessarily losses for the right. Baron and Ferejohn’s (1989) “divide the dollars” game characterizes negotiation as a game of building minimum-winning coalitions to divide the spoils. “Vote buying” models reflect a similar logic (Snyder 1991; Groseclose and Snyder 1996), with leaders expected to offer side payments to win legislators’ votes, but only up to the minimum number of votes needed.

Finally, Congress is described as focused more on politics than on problem solving. Under contemporary conditions of fierce party competition for majority control, members continually engage in a quest for partisan political advantage (Lee 2016). Members force roll-call votes to define party differences, deploy harsh rhetoric against opponents, and employ increasingly sophisticated public relations operations to disseminate their messages to wider publics (Crosson et al. 2021). Members feel increased pressure to raise campaign money, which consumes more of their time and directs their attention to the hardline ideological preferences of big donors (Canes-Wrone 2025). Members also know that grandstanding and outrage win media coverage and thereby assist in raising campaign money (Ballard et al. 2023; Costa 2025). None of these activities fosters cooperative bipartisanship.

Taken together, the scholarly literature on Congress offers almost nothing by way of a positive view of the institution’s capabilities for problem solving. The portrait is of a poorly representative institution that employs suboptimal legislative procedures to jam through legislation with clear winners and losers. That is, it behaves in such a way when it can pull itself away from position-taking and grandstanding to legislate at all.

2 Credibly Representative

Although the institution has never perfectly mirrored the country it represents, the polarized Congress measures up surprisingly well by the most important benchmark: partisan representation. Party is the single most important factor shaping the political views and behavior of both voters and elected officials. Congress has afforded roughly proportional representation to the major parties since the 1990s. Despite its use of single member districts and plurality election rules, the division of party power in Congress closely mirrors the balance between the parties as reflected in presidential elections and in public opinion polling. Our 50-50 Congress accurately reflects our 50-50 country. In the 2024 elections, for example, Donald Trump won 51 % of the two-party vote for president nationally, and Republicans won 51 % of House seats and 53 % of Senate seats. In the 2020 elections, Joe Biden won 51 % of the national popular vote, and Democrats won 51 % of House seats and 50 % of Senate seats. Whatever distortions are produced by gerrymandering, parties receive aggregate seat shares appropriate for their support in the electorate nationally.

Congress has never been more racially, ethnically, and gender diverse than it is today. The institution has made big strides in achieving closer correspondence to the American population, most especially during the last decade. Black representation in Congress has increased by 75 % since 2000, with the biggest gains since 2014. In fact, Black Americans are not currently underrepresented in the House, making up 12 % of the national population and 14.2 % of the 119th House of Representatives (2025–26). Hispanic Americans have seen their presence in Congress increase more than 180 % over the past 25 years. Although the Senate is much less representative in terms of race and ethnicity, it is a better mirror than it used to be. For the first time, two Black women were elected to the Senate in the 2024 elections.

Women make up a quarter of the Senate and 29 % of the House. As late as the 1980s, women only made up 5 % of Congress. Women are now approaching representational parity in the Democratic party in Congress, where they make up more than 40 %. Less well known is that the share of women in the congressional GOP almost doubled since 2020 (from 8 to 15 %).

Altogether, while the U.S. Congress is not a perfect mirror of the American public, it is a credibly representative institution. In particular, party divisions in both the House and Senate closely track the partisan cleavages in the broader electorate. Just as important, Congress routinely relies on inclusive procedures during debate and deliberation, creating space for competing viewpoints and encouraging the integration of political differences in legislative outcomes.

3 Inclusive Processes

An underappreciated aspect of congressional processes is that they are designed to acknowledge, respect, and give full voice to political disagreement. When legislation is debated, proponents and opponents are allocated equal time. This convention of granting equal time on both sides of pending questions is followed, even when the chambers operate under special rules adopted by majority vote (as is common in the House) or under unanimous consent agreements (as commonly in the Senate). When witnesses are questioned in congressional hearings, committees typically employ the “five-minute rule” granting each committee member five minutes for questions and comments. Equal time for proponents and opponents is the norm even when one party has a large majority in Congress.

Second, Congress’s processes are inclusive because the minority party chooses its own representatives on committees. In the current Republican-majority Congress, for example, Democrats on the Ways & Means Committee or on the Oversight Committee are the Democrats that Democratic party leaders and members want to have there. Democratic members of committees are not hand-picked by the Speaker or the Republican party. Committees are not always perfectly representative of the chamber. In the House, the majority party gives itself an outsized majority on some committees. But the committee system on the whole is representative of Congress. Regardless there is no “tokenism,” where the party in power chooses its preferred minority party members for various positions.

Third, legislative processes enforce norms of respect and civility. During floor debate and within committee meetings, by rule, members may not refer to one another in a derogatory manner, nor may they attack their motives. There are breaches of decorum, but these norms are largely adhered to, and members whose actions violate these rules are typically reprimanded, and their words are “taken down.” Recent congresses have not seen any increase in the frequency with which words are taken down (Alexander 2021).

Americans could learn a thing or two about civility and respect for difference from watching Congress. In a classic comparative legislatures text, David M. Olson (1994, 130) noted how parliaments in the new democracies created after the fall of the Soviet Union modeled democratic debate and deliberation in an open society. “In newly democratic societies, parliament is the leading example of what democracy is in practice.” Whatever shortcomings congressional deliberation might have, the institution shows respect for political diversity and opposing points of view. Congress and other U.S. legislatures arguably adhere better to these fundamental liberal values than almost any other institutions in American society.

4 Consensus-Based Legislating

It’s not merely that Congress’s processes are inclusive and respectful of difference. Congress’s legislative outcomes are highly inclusive, as well. Laws, quite simply, rarely get enacted on close votes. Across the past 50 years, the average bill that became law passed the Senate with 77 votes and the House with support from 78 % of the chamber. There has been little change in this indicator, despite polarization on roll-call voting generally and all the other disincentives to bipartisanship prevalent in today’s political context. In other words, it is still the case that most of what passes Congress was acceptable to most members.

The picture is not different if one looks instead only at important laws, as designated by the lists that Yale political scientist David Mayhew has long compiled at the end of each Congress.[1] The average important law passed the House with 70 % support and the Senate with 77 % support. Our research shows that the increase in centralized legislative power and departures from regular order have not resulted in increases in the frequency of partisan enactments (Curry and Lee 2020). In fact, bills developed via “unorthodox” processes are no more likely to pass on party-line votes than legislation crafted via “regular order” legislative processes in which committees take the lead.

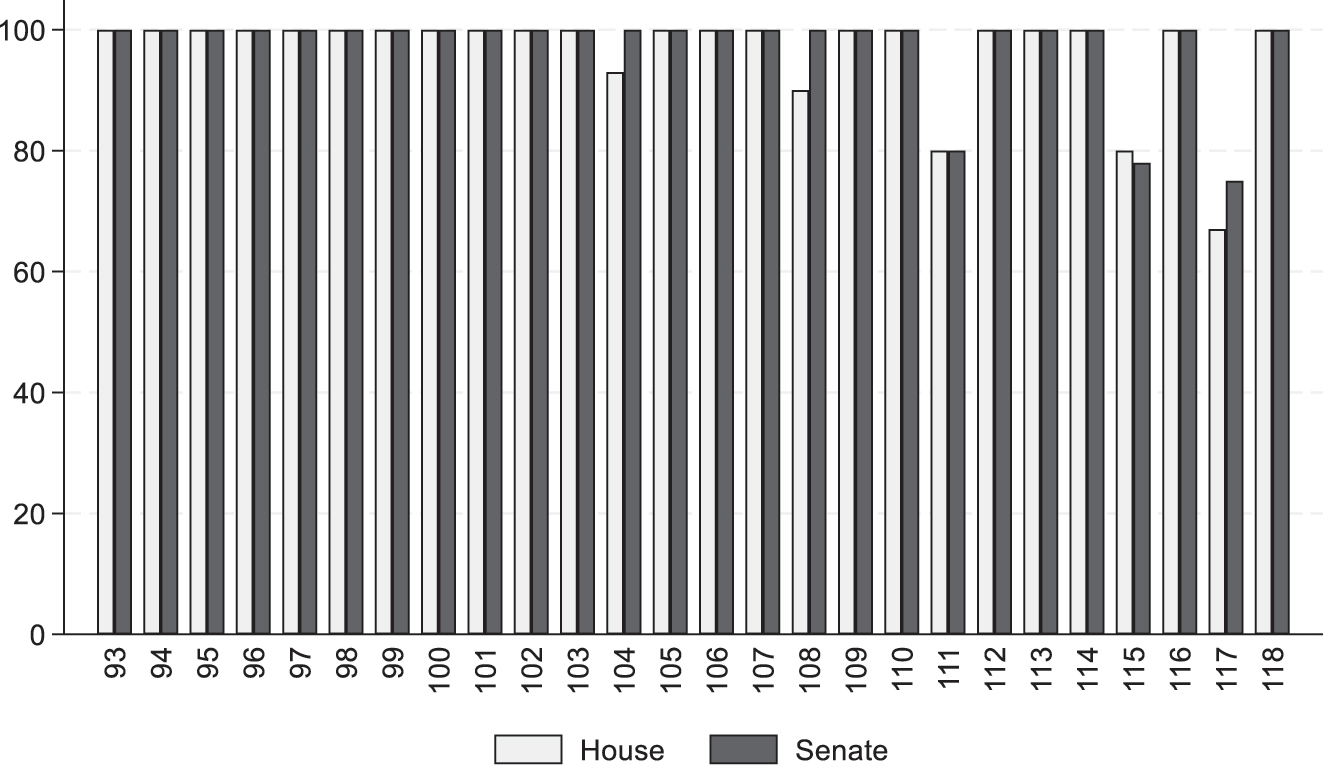

Very few important laws pass without meaningful minority party support, regardless of the procedures used or conditions of unified or divided party control. If we set the bar at 10 % or more of the minority party voting in favor, 100 % of important laws typically clear it each congress (see, Figure 1). Generally speaking, a president working with unified control of both chambers of Congress can expect to get only one or two important laws passed without any support from the minority party. George W. Bush got his tax cuts; Barack Obama got Obamacare and the stimulus package; Donald Trump won another round of tax cuts in 2017; and Joe Biden got his Covid bill and a health care/environment package. Trump reauthorized the 2017 tax cuts in 2025 as part of a sweeping enactment reflecting the most ambitious single-party enactment to date, the “One Big Beautiful Bill.” Even in the polarized era, enactments passed with only one party in support have been very unusual. The One Big Beautiful Bill is a significant exception, but the fact is that lawmaking has remained predominantly bipartisan, even as partisan conflict has intensified.

Share of important laws enacted with at least 10 % of the minority party in support, 1973–2024.

5 Co-opting, Not Steamrolling Minority Parties

Even when majority parties in Congress are trying to legislate on their top agenda priorities, they are more likely to win by co-opting, rather than steamrolling the minority party. When they succeed in enacting legislation on their agenda items, majority parties usually do so by getting buy-in from the minority party.

For this point, we draw on data collected for our book, The Limits of Party (Curry and Lee 2020), which we have updated for subsequent years. To gauge the success congressional majority parties achieve on their top legislative priorities, we read the opening speeches of every Speaker of the House and Senate majority leader since the 99th Congress (1985–86) and examined every bill introduced into a majority leadership reserved bill slot in the House (H.R. 1–10) and Senate (S. 1–5). The result is a list of 312 agenda items majority parties wanted to address in each congress through the 118th (2023–24).[2] We then constructed legislative histories of each of these items.

For each agenda priority, we ascertain whether or not the majority party succeeded in enacting a law addressing that issue. For all those agenda items on which the majority succeeded in passing a law, we noted how they got the job done. We identified four potential “pathways” to legislative success.

Bipartisan logroll: These are cases in which the majority party logrolled with the minority party, pairing the majority’s priorities with items on the minority’s wish list.

Seek broad support: These are cases in which the majority party reaches out to the minority party at the start of the legislative process to craft a bill that can obtain broad support across the political spectrum.

Back down: These are cases in which majority party starts out by making a strong, partisan proposal. However, as the process unfolds, the majority party backs down on contentious aspects of its proposal in order to secure votes from the minority party.

Steamroll: These are cases in which the majority party proposes a policy strongly opposed by the minority party, but goes on to pass it without making any significant concessions.

The first three of these pathways to success all involve crafting legislation that can be supported by large bipartisan majorities. The first two pathways feature efforts to secure minority party support from the outset of the legislative drive; the third pathway involves the majority party conceding on its controversial provisions in order to win minority party support. Only the fourth approach – the steamroll – yields legislation that will allow the majority party to claim clear partisan credit for the enactment. It is the only pathway to success that does not afford at least some credit-claiming opportunities for the minority party.

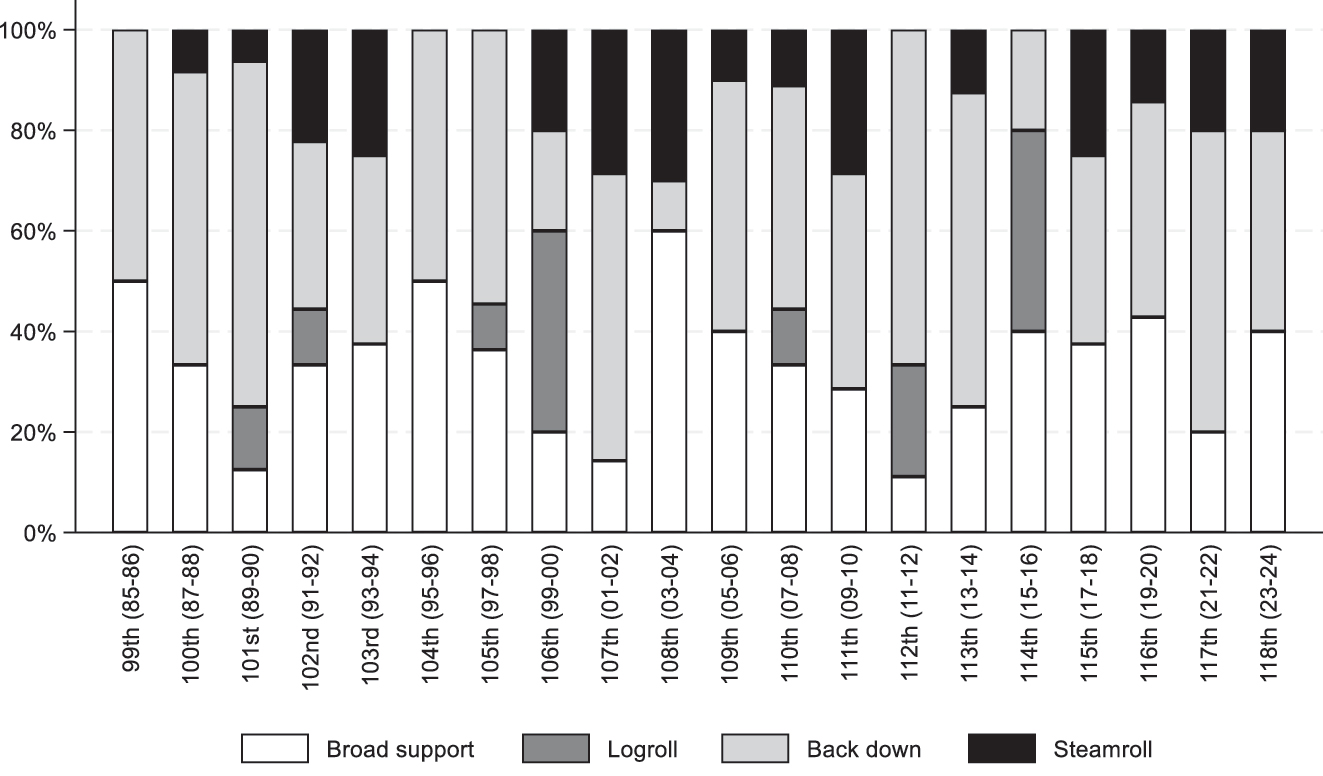

Figure 2, below, shows the pathways by which majority parties achieved success on their legislative priorities (those that resulted in the enactment of a new law, 152 in total). Parties could take more than one pathway on a legislative i.e. but did so rarely (13 % of the time). Across the time period, majority parties enacted priority legislation without winning significant minority party support just 14 % of the time. They wound up taking the “back down” path more than half of the time (54 %). Over 45 % of the time, they pursued pathways that accommodated the minority party from the start, by either seeking broad support (33 %) or by logrolling to incorporate minority party priorities into a larger legislative package (8 %).

Pathways to success on majority party agenda items, 1985–2024.

Majority parties rarely succeed in enacting legislation that constitutes an unambiguous “win” that will allow them to claim exclusive credit for the enactment. In five of the 20 congresses in the dataset, the majority party notched no “steamroll” wins at all. There is no Congress in the time series in which the majority party achieved most of its successes via the steamroll path. In most congresses, the vast bulk of the majority party’s successes were accomplished by backing down or by seeking broad support. There is no trend in these data. Pathways to success since the 2010s are much the same as they were in the 1980s and 1990s.

Majority party successes overwhelmingly featured broad bipartisan support on final passage. Fully 78 % of these enactments passed with at least a majority of the opposition party in one or both chambers of Congress voting in support, and 83 % were endorsed by one or more top elected leaders of the minority party.

Even when majority parties are trying to enact legislation on their partisan agenda priorities, they are rarely able to do so in a manner that maximizes their own party’s credit claiming opportunities. These pathways to success also do not turn on the majority party using its institutional resources to muscle through legislation over sustained minority party opposition. Only the steamroll victories feature any significant amount of success via minimum winning coalition. Majority party successes instead normally occur via lopsided majorities and co-optation of the minority party.

6 Two Cases of Congressional Problem-Solving

Rather than the zero-sum games that predominate in political science theory, legislation may instead more often take the form of positive-sum or integrative negotiation (see Warren and Mansbridge 2016). Legislative efforts often get underway when members broadly agree that a problem or need for legislation exists. In such cases, they nevertheless often confront either uncertainty about how to address the issues or an array of different ideas about how to do so. Negotiators will need to uncover or develop policy proposals they believe can address the perceived problems while also not crossing anyone’s red lines. This is not trivial work. It requires serious effort and creativity. But Congress frequently engages in this kind of work, even if it is not as readily recognized by scholars or observers of the institution, who tend to conceive of legislating as a zero-sum game.

Congressional problem-solving efforts featuring positive-sum, consensus-oriented negotiation are apparent in the legislative histories of a large number of major enactments across recent years: the Bipartisan Infrastructure law (2021) investing in transportation, broadband and electric grid renewal; the CHIPS and Science Act (2022) to foster scientific research and domestic manufacturing of semiconductors; the Great American Outdoors Act (2020) funding national parks and conservation; the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (2018) addressing the opioid crisis; the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act (2022) enhancing background checks and gun safety; the 21st Century Cures Act funding cancer research and streamlining the FDA (2016); the Dingell Act (2019) protecting public lands and expanding wilderness areas, and the Postal Service Reform Act (2022) stabilizing financing of the postal service. Positive-sum accommodation of diverse interests is also a feature of virtually every appropriations bill that gets enacted.

Below are brief sketches of two such problem-solving efforts in recent years.

6.1 Covid Relief in 2020

The Covid pandemic triggered the largest-ever crisis response in United States history. Across four enactments in 2020, Congress authorized more than $3.1 trillion in new spending, most of which was allocated to keeping businesses and workers afloat through closures. Gauged by the increase in expenditures relative to total gross domestic product, 2020 pandemic aid was bigger than the 2009 stimulus package and the New Deal combined.[3] The largest of these enactments was the $2.2 trillion CARES Act in March, followed by a $900 billion package in December.

Congressional negotiators had to resolve an array of conflicts amid a fast-moving public health and economic crisis.[4] Republicans and Democrats disagreed on the size of the aid packages needed, with Democrats favoring larger expenditures. The parties disagreed on the need for aid to state and local governments, on the generosity and time limits for unemployment benefits, on shielding businesses, schools and universities from pandemic-related lawsuits, and on direct assistance to corporations, among others matters.

To a considerable extent, these conflicts were resolved by logrolling. Democrats went along with Republican priorities, and vice-versa, as long as those priorities did not cross either party’s “red lines.” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) kicked off the negotiations by advancing the first proposal. He initiated negotiations among Republicans, aiming to reach internal party agreement before soliciting support from Democrats.[5] McConnell unveiled his $1 trillion proposal on March 19, organized around what he called four “pillars”: aid to small business, cash payments for individuals, loans for pandemic-impacted industries, and support for the health-care sector.[6]

Democrats denounced McConnell’s proposal as grossly inadequate. In a joint statement, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) criticized the draft for putting “corporations way ahead of workers.”[7] Democrats had a range of demands: a special pandemic unemployment bonus of $600 per week, suspension of student loan payments, as well as more aid to hospitals, health systems, and state and local governments, among others. By the time the CARES Act was complete, it had doubled in size, with the final legislation authorizing $2.2 trillion. The resulting package was a gigantic logroll that included McConnell’s four pillars, as well as funding for Democrats’ top priorities.

The December 2020 Covid aid package took longer to negotiate. The two parties reached agreement relatively quickly on a $900 billion top line. But then they deadlocked over a set of priorities, neither of which could win bipartisan support. Democrats wanted a new infusion of aid to state and local governments, which Republicans regarded as an unacceptable “blue state bailout.” McConnell’s priority was a shield against pandemic-related lawsuits for businesses, universities and other entities, which Democrats regarded as a nonstarter. The parties could never bridge their differences on these priorities. In the end, the December package came together by narrowing the scope of their negotiations. In an “anti-logroll,” the parties agreed to set aside each party’s most controversial priority. Although the package did not fully satisfy either party, both were willing to move forward with those provisions that could get sufficient support for enactment.

6.2 Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act (2022)

Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election pushed Congress to address the longstanding weaknesses of the Electoral Count Act of 1887. With its antiquated and ambiguous language, the existing Electoral Count Act failed to offer clear guidance on key aspects of the process. The law was especially unclear about how disputed elections were to be handled, rendering the statute open to the multiple interpretations and confusion that Trump’s legal team sought to exploit. There was bipartisan acknowledgement of the problem and support for fixing the law, but there was not agreement on how to do it.

First, there were disagreements about what fixes to the law were preferable. Some thought an expedited judicial review process should be used to resolve disputes, while others thought such a process would be easily abused. Some thought legal challenges should take place in state courts, while others thought federal courts were preferable. Some thought governors should be given the power to certify a state’s winner, while others thought this was too much power in the hands of one individual.

Second, there were turf wars dividing the House and Senate. Members of the House’s January 6th Select Committee thought they should lead out on reforms. Senators, on the other hand, believed the Committee had poisoned the well, and that they should take the lead. Third, there were concerns about alienating Republicans, either because the proposal could be interpreted as an attack on Trump, or by succumbing to Democrats’ wishes to tie ECA reforms to unrelated reforms of voting rights, campaign finance, redistricting, or other electoral processes.[8]

Negotiations in the Senate, led by Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Susan Collins (R-ME), lasted for over a year. Unlike in the CARES Act – where coalition leaders built an additive coalition by expanding the scope of a bill and including more members’ priorities – in this case the key to success was narrowing the scope of the negotiations to focus only on the problems with the ECA. The narrower the focus, Collins told reports, the more quickly the 16-senator “gang” could act.[9]

Senate negotiators rolled out a bill draft in summer 2022 that would clarify the vice president’s role in the process as purely ministerial; specify governors’ power to approve a state’s electors; establish an expedited judicial review to challenge governors’ decisions in federal court; define narrowly what constitutes a valid challenge to state certification; and require one-fifth support in both chambers of Congress to force a vote on objections to state electors.[10]

The proposal quickly drew criticism from some Democrats for being too weak. House Democrats on the January 6 Committee were most vocal. But they did not provide much detail about their concerns, perhaps because their objections were primarily rooted in the view that they should take the lead. Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD) called the proposal, “not remotely sufficient,” but declined to say why.[11] Other Democrats, especially elections lawyer Marc Elias, argued that it gave governors too much power, did not leave enough time for adequate legal challenges, and placed too much faith in federal courts.[12]

The House Committee then rolled out a more complex bill that included a list of “catastrophic” events permitting a state to prolong its voting period; a process for candidates to sue state election officials; a longer list of valid challenges to a state’s selection of electors – including barring electors who supported a candidate who had “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” – and a threshold to challenge certification in Congress at one-third of both chambers.[13]

Republicans overwhelmingly rejected the House bill. “I take it for what it is,” said Representative Jim Banks (R-IN), Republican Study Committee chair, “a political weapon to beat up on Donald Trump and not about preventing a Jan. 6 from ever happening again.”[14] It received just 10 Republican votes on the floor. Senate negotiators were left with a major challenge: make enough changes to satisfy House Democrats without adding detail that would alienate Senate Republicans.

Negotiations, now led by Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), chair of the Senate Rules and Administration Committee, involved discussions with legal scholars and practitioners about what might work. The final bill kept the structure of the original Senate proposal, but made changes to address Democrats’ concerns. Among other revisions, the bill made clear that gubernatorial decisions were subject to a narrowly defined set of legal challenges and review; emphasized that state laws were the primary basis for legal challenges; and made Supreme Court review optional.

In the end, the law was able to pass as part of an omnibus spending package in December because it no longer elicited any significant controversy. Congress had succeeded in building universal support for a major law addressing one of the most partisan and contentious events of the 21st century, the ambiguities in the ECA that Trump exploited in his efforts to overturn the 2020 elections. Leading legal scholar Cass Sunstein (2022) called it a “phenomenal achievement.” It was praised on the right, left, and center: by the Center for American Progress,[15] the Cato Institute,[16] and the Campaign Legal Center.[17]

7 Two Cases of Steamrolling: Infrequent, But Disruptive

Bipartisan problem-solving approaches to lawmaking are the norm on Capitol Hill, and majority “steamrolls” are comparatively rare. Yet they do occur – and examining such cases underscores the value of Congress’s typical processes. The last two major steamrolls – the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA, 117th Congress) and the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA, 119th Congress) – illustrate an inferior approach to problem solving, one prone to ongoing contention and long-term policy instability. Together, they offer a cautionary tale for those who push Congress to operate in a more programmatic or parliamentary fashion.

It is important to acknowledge that both the IRA and the OBBBA involved problem solving. In the case of the IRA, Democrats sought to address several long-standing problems. First, they aimed to confront global climate change – an issue central to the party for decades and increasingly urgent as global temperatures continued to rise.[18] They also sought to curb rising healthcare costs, which had continued to climb through the 2010s and 2020s, despite the enactment of the Affordable Care Act.[19] Democrats also hoped to close tax loopholes disproportionately benefiting wealthy Americans. Reforming the tax code to increase revenue from high-income individuals had long been a party priority, especially as a series of tax cuts since 2001 had reduced the burden on the richest households and corporations while also increasing budget deficits.

Similarly, at least two salient policy problems motivated the GOP as it took up the OBBBA. First was the impending expiration of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), enacted during Donald Trump’s first term. Many of its provisions were scheduled to sunset at the end of 2025, which would have triggered trillions of dollars in tax increases affecting roughly 80 % of Americans through higher rates, a reduced standard deduction, a smaller child tax credit, and other changes.[20] Even though the parties disagree about tax policy, even Democrats would probably have perceived the expiration of all the 2017 tax cuts as a policy problem, had they won unified control in the 2024 elections. Republicans were also driven by the deteriorating situation at the southern border. Illegal crossings had surged during the Biden administration, peaking in late 2023,[21] with migrant deaths reaching record highs,[22] contributing to what many viewed as a genuine humanitarian and international crisis. By early 2025, about half of Americans, and 70–80 % of Republicans, told pollsters that immigration and border security were major issues requiring government action.[23]

However, in partisan steamrolls, both problem definition and solution design are only partially developed. Such efforts reflect the concerns and preferences of just one segment of Congress – the majority party. Table 1 lists the major enactments since the start of the Obama administration that qualify as partisan steamrolls – cases in which the majority party notched a clear policy victory on a party-line vote.[24] What stands out is that every one of these steamrolls occurred under unified party government, and all but one depended on expedited processes to secure passage. At least half of them then generated sustained contention and agitation for repeal.

Partisan steamrolls, 2009–2025.

| Congress | Party | Steamroll | Expedited procedures? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 111 | Democrats | The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) | yes* |

| 111 | Democrats | Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act | no |

| 115 | Republicans | Obama administration rules roll-backs | yes |

| 115 | Republicans | The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act | yes |

| 117 | Democrats | The American Rescue Plan | yes |

| 117 | Democrats | The Inflation Reduction Act | yes |

| 119 | Republicans | One Big Beautiful Bill Act | yes |

-

*Budget reconciliation was not used to pass the ACA itself, but to get the bill through the House, they had to also pass the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 using budget reconciliation, which made various changes to the law in a manner that could sidestep the filibuster.

Expedited procedures include budget reconciliation, which are not subject to the Senate filibuster or the 60-vote cloture threshold. The last four laws on the list – the OBBBA, the IRA, the American Rescue Plan (ARP), and the TCJA – were all enacted exclusively through reconciliation. The Affordable Care Act was not itself passed under reconciliation, but a separate reconciliation bill was required to secure the votes for final passage. The Obama-era regulatory rollbacks – a set of 14 enactments nullifying agency regulations – were advanced under the Congressional Review Act, which establishes expedited procedures, including exemption from the filibuster, to overturn recently adopted rules. The only one of these seven enactments that did not rely on expedited procedures was the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Its passage was aided by the Democrats’ near–filibuster-proof 59-seat Senate majority and the support of a small number of Republican senators.

While expedited procedures can help Congress avoid gridlock and bypass the filibuster, they also make lawmaking on Capitol Hill less inclusive. When majority-party votes alone are sufficient for passage, House and Senate leaders engage primarily with their own members and negotiate only within the majority. The minority’s perspectives are sidelined. This dynamic can deliver a clear policy victory for the majority party – sometimes on goals it had pursued for decades, as with the ACA. But it also narrows the range of viewpoints that shape problem definition and solution development, resulting in legislation crafted from a more limited set of perspectives.

Expedited procedures can also produce policy changes that are unusually vulnerable to reversal (Ragusa and Birkhead 2016), increasing the risk of policy instability. This dynamic is evident with the IRA and the OBBBA. The IRA created an array of green energy tax incentives – including production and investment credits for wind, solar, geothermal, and clean hydrogen; electric vehicle credits; and incentives for energy-efficient home improvements, and more. Yet just three years later, the OBBBA sought to dismantle or phase out many of these credits, even as businesses and consumers had already committed billions of dollars in investments based on them.[25]

Some Republicans acknowledged the costs of such policy whiplash. “One of the worst things that we do to businesses is inconsistency and unpredictability,” Senator John Curtis (R-UT) told NPR. “If we’re closing [these credits] down, let’s just do it in a way that takes into account those employees of those businesses, the banks that loaned on those projects, and make sure we have business certainty.”[26] Such concerns got members to agree to a slower phase-out of some clean-energy incentives. Yet even that mitigation might have looked different had a broader, bipartisan set of lawmakers been engaged in the OBBBA deliberations – just as the original structure of the credits might have been shaped differently and been better protected against reversal had Republicans participated in negotiations over the IRA.

Green energy incentives are only one illustration. The IRA increased the tax burden on the wealthiest businesses and individuals; the OBBBA reversed course and reduced it. The IRA aimed to lower barriers to health care access by requiring Medicaid and CHIP to cover more vaccines and by extending enhanced premium tax credits,[27] while the OBBBA imposed stricter requirements for maintaining Medicaid coverage.[28]

In general, steamrolls are handled differently from most lawmaking on Capitol Hill – and in ways that involve more partial efforts at problem definition and solution consideration. Yet it is important to remember that one-party legislating remains rare. Steamrolls are the exception, not the rule, even in today’s party-polarized Congress. Most of the time, Congress approaches policymaking through more inclusive, bipartisan processes that incorporate diverse perspectives. Scholars should take seriously how Congress’s usual mode of operating promotes conflict-resolution and policy stability, even during times of intense partisan conflict. At minimum, such outcomes better protect society’s reliance interests with respect to major legislation.

8 Legislative Activism in the Polarized Congress

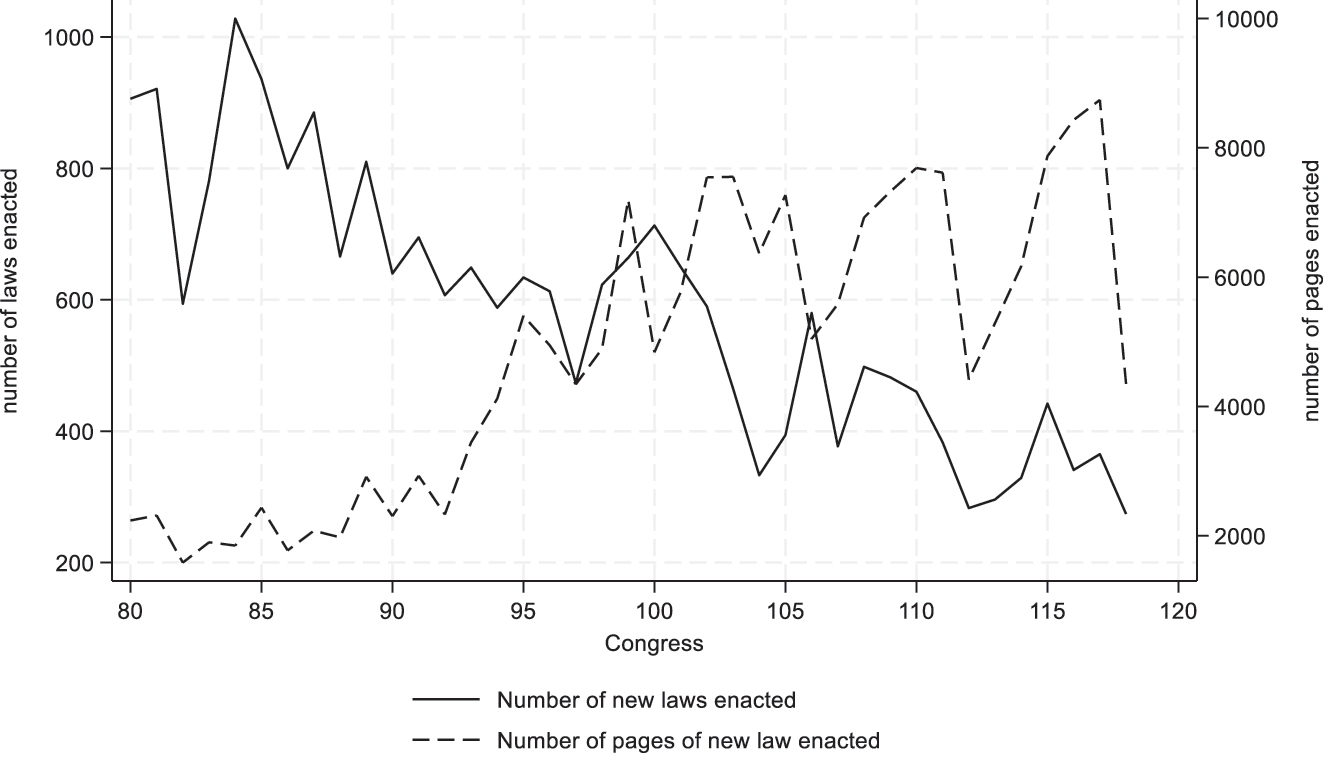

The formidable difficulties of forging consensus in the polarized Congress could reasonably be expected to yield institutional paralysis. Stalemate undoubtedly prevails on important issues. But real-world data on legislative activity are much more ambiguous. The contemporary Congress overall is not less legislatively active than the Congress of the 20th century. As gauged by sheer volume, recent Congresses have passed just as much legislation as Congresses of the 1970s and 1980s.

Figure 3 displays data from the Brookings Institution’s Vital Statistics on Congress.[29] As is clear here, the number of individual laws passed per Congress has declined since the middle of the 20th century. At the same time, however, the number of pages of legislative text enacted in each two-year Congress has not decreased. Likewise, if one measures Congress’s productivity by the number of titles of legislation enacted, the contemporary Congress is no less productive than it was in the early 1980s and more productive than it was in the 1950s–1970s (Jones et al 2019, 155). The polarized Congress makes much greater use of omnibus legislating (Curry 2015; Curry and Lee 2020; Krutz 2001). In other words, individual laws have grown much longer such that the total volume of lawmaking is not less. Indeed, both the 116th Congress (2019–2020) and the 117th Congress (2021–22) set new, all-time records for the total amount of enacted legislation. Consistent with Mayhew (2005), high levels of activism in recent congresses extended across episodes of divided (116th Congress) and unified (117th Congress) party control. There is no clear evidence that the laws the polarized Congress enacts are less substantively significant than those of previous eras (Farhang 2021).

Volume of enacted legislation, by Congress, 1947–2024.

9 Discussion and Unanswered Questions

Consider an image that routinely appears in national news reporting: a photo of a “four corners” meeting of the president along with the bicameral bipartisan leaders of Congress. Such meetings are how big decisions about domestic policy commonly get made, especially but not exclusively under conditions of divided party control. Such meetings routinely handle the omnibus appropriations packages that keep the federal government functioning.

We normally conceive of Congress as an arena of conflict. There is no shortage of conflict, to be sure. But it is a mistake to stop with this fact. Congress’s main contribution to American politics is to bring the parties to terms. The process conforms to some fundamental features of fairness. Parties receive representation in Congress that accords well with their levels of national public support. Not even a regime of proportional representation could much improve on it. Today’s Congress is also more representationally diverse than ever. It operates under procedures that allow both parties to have input. To the extent that we expect Congress to confront important issues in American politics, it is as well positioned in representational terms to do so as it has ever been.

Over recent decades – and amidst high levels of polarization and political fragmentation – Congress has frequently achieved broad-based agreements to keep the federal government operating and to address widely perceived problems and needs. Despite polarization, congressional majority parties rarely succeed in enacting legislation without winning bipartisan support. Instead, majority parties usually succeed on their agenda items – when they succeed at all – by getting buy-in from the minority party. Data on the volume of legislation enacted over time do not show that the polarized Congress is paralyzed or inactive. Instead, it enacts as much legislation as it did when levels of polarization were much lower.

We need better theorizing about how Congress reaches broadly-supported agreements for legislative action. The case examples examined here point to the need for scholars to conduct more close analysis of real-world congressional negotiation. We need many more such cases systematically analyzed. Looking to the cases considered here, one factor that seems quite relevant is Congress’s freedom to define the scope of negotiations for itself. In these cases, the range of included policies was subject to negotiation, not fixed within any pre-existing choice space. Agreements could be achieved by building an “additive coalition” that logrolled each party’s priorities. It could also be reached by narrowly focusing on just those provisions acceptable to both parties and excluding contentious matters. We are not aware of research that investigates how Congress engages in negotiations about the scope of enactments.

What is clear is that these cases are not well-suited to interpretation within the framework of a zero-sum game, in which opposing sides seek gains at each other’s expense. Neither the Covid aid enactments of 2020 nor the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022 entailed negotiators adjusting policy along a fixed continuum from left to right. They were also not “divide the dollars” negotiations over a fixed pie. They certainly did not represent one party getting a “win” over the opposition of the other.

These were complex, multi-dimensional negotiations where the scope and range of issues included in the negotiations was endogenous to the negotiation itself. These enactments only came together when both parties agreed that there was a real problem that needed addressing and also agreed that the packages they had assembled could be construed as an improvement on the status quo. In reaching these conclusions, Democratic and Republican negotiators probably focused on different aspects of the packages as they went back to their party colleagues to ask for support on final passage. But as on most legislation that gets enacted, today as in the 20th century, members were able to come together as part of broad, bipartisan coalition.

The processes resulting in the IRA and the OBBBA were much more partial, involving only one party in the negotiations. In both cases, the legislation could be characterized as efforts at problem solving. But by including only one party, problem-definition was one-sided, and the result was a failure of conflict-resolution. Contention continued unabated. Indeed, the OBBBA undid an array of the enactments included in the IRA. Looking ahead, there will be ongoing efforts to reverse major parts of the OBBBA, perhaps most especially its cuts to Medicaid.

Accommodation and conflict resolution are arguably what is most needed in a polarized country where neither major party commands majority support most of the time. These are Congress’s great strengths. It is a messy process. But what Congress is good at doing is arriving at acceptable political settlements. Its record of success is imperfect. No doubt, there are many important policy problems that have not been addressed adequately or at all. But Congress arguably does more to promote conflict-resolution in our polarized society than other institutions of American government.

References

Adler, E. Scott., and John D. Wilkerson. 2012. Congress and the Politics of Problem Solving. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139150842Suche in Google Scholar

Aldrich, John H., and David W. Rohde. 2000. “The Consequences of Party Organization in the House: The Role of the Majority and Minority Parties in Conditional Party Government.” In Polarized Politics: Congress and the President in a Partisan Era, edited by Jon R. Bond, and Richard Fleisher, 31–72. Washington, DC: CQ Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Alexander, Brian. 2021. A Social Theory of Congress: Legislative Norms in the Twenty-First Century. Lanham: Lexington Books.10.5040/9781666983210Suche in Google Scholar

Anzia, Sarah F. 2025. “The Politics of Problem Solving: Housing, Pensions, and the Organization of Interests.” The Forum. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2025-2029. In this issue.Suche in Google Scholar

Ballard, Andrew O., Ryan DeTamble, Spencer Dorsey, Michael Heseltine, and Marcus Johnson. 2023. “Dynamics of Polarizing Rhetoric in Congressional Tweets.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 48: 105–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12374.Suche in Google Scholar

Baron, David, and John Ferejohn. 1989. “Bargaining in Legislatures.” American Political Science Review 83 (4): 1181–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961664.Suche in Google Scholar

Binder, Sarah A. 2003. Stalemate: Causes and Consequences of Legislative Gridlock. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Canes-Wrone, Brandice. 2025. “Congressional Fundraising Dynamics and their Implications for Problem-Solving.” The Forum. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2025-2031. In this issue.Suche in Google Scholar

Carnes, Nicholas. 2013. White-Collar Government: The Hidden Role of Class in Economic Policy Making. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226087283.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Costa, Mia. 2025. How Politicians Polarize: Political Representation in an Age of Negative Partisanship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cox, Gary W., and Mathew D. McCubbins. 2005. Setting the Agenda: Responsible Party Government in the U.S. House of Representatives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511791123Suche in Google Scholar

Crosson, Jesse M., Alexander C. Furnas, Timothy Lapira, and Casey Burgat. 2021. “Partisan Competition and the Decline in Legislative Capacity Among Congressional Offices.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 46 (3): 745–89, https://doi.org/10.1111/lsq.12301.Suche in Google Scholar

Curry, James M. 2015. Legislating in the Dark: Information and Power in the House of Representatives. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226281858.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Curry, James M., and Frances E. Lee. 2020. The Limits of Party: Congress and Lawmaking in a Polarized Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226716497.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Evans, C. Lawrence. 2024. “Senate Countermajoritarianism.” American Political Science Review 119 (2): 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055424000510.Suche in Google Scholar

Farhang, Sean. 2021. “Legislative Capacity & Administrative Power Under Divided Polarization.” Daedalus 150 (3): 49–67.10.1162/daed_a_01859Suche in Google Scholar

Fishback, Price, and Valentina Kachanovskaya. 2015. “The Multiplier for Federal Spending in the States During the Great Depression.” Journal of Economic History 75 (1): 125–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022050715000054.Suche in Google Scholar

Fisher, Patrick. 2020. Insufficient Representation: The Disconnect Between Congress and its Citizens. Rowman & Littlefield.Suche in Google Scholar

Groseclose, Tim, and James M. Snyder. 1996. “Buying Supermajorities.” American Political Science Review 90 (2): 303–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082886.Suche in Google Scholar

Hall, Richard L., and Frank W. Wayman. 1990. “Buying Time: Moneyed Interests and the Mobilization of Bias in Congressional Committees.” American Political Science Review 84 (3): 797–820. https://doi.org/10.2307/1962767.Suche in Google Scholar

Howell, William G., and Terry M. Moe. 2016. Relic: How Our Constitution Undermines Effective Government, and Why We Need a More Powerful Presidency. New York: Basic Books A Member of the Perseus Books Group.Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Bryan D. 2025. “Are Democracies Better at Solving Problems than Non-Democratic Regimes?” The Forum. In this issue.Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Bryan D., Sean M. Theriault, and Michelle Whyman. 2019. The Great Broadening: How the Vast Expansion of the Policy-Making Agenda Transformed American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226626130.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Kalla, Joshua L., and David E. Broockman. 2016. “Campaign Contributions Facilitate Access to Congressional Officials: A Randomized Field Experiment.” American Journal of Political Science 60 (3): 545–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12180.Suche in Google Scholar

Krehbiel, Keith. 1998. Pivotal Politics: A Theory of U.S. Lawmaking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226452739.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Krutz, Glen S. 2001. Hitching a Ride: Omnibus Legislating in the US Congress. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lawless, Jennifer L., and Richard Logan Fox. 2010. It Still Takes a Candidate: Why Women Don’T Run for Office. Rev. ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511778797Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Frances E., and Bruce I. Oppenheimer. 1999. Sizing up the Senate: The Unequal Consequences of Equal Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, Frances E., Bettina Poirier, and Christopher Bertram. 2024. “High Stakes Negotiation: Reaching Agreement on Pandemic Aid in 2020.” In Disruption? The Senate During the Trump Era, Sean Theriault, 87–113. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780197767832.003.0006Suche in Google Scholar

Mayhew, David R. 2005. Divided We Govern: Party Control, Lawmaking and Investigations, 1946-2002, 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Mayhew, David R. 2017. The Imprint of Congress. New Haven: Yale University Press.10.12987/yale/9780300215700.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

McCarty, Nolan M. 2019. Polarization: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.10.1093/wentk/9780190867782.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Olson, David M. 1994. Democratic Legislative Institutions: A Comparative View. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe.Suche in Google Scholar

Ragusa, Jordan M., and Nathaniel A. Birkhead. 2016. Congress in Reverse: Repeals from Reconstruction to the Present. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Sinclair, Barbara. 2016. Unorthodox Lawmaking: New Legislative Processes in the US Congress. Washington DC: CQ Press.10.4135/9781506322810Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, Steven S. 2014. The Senate Syndrome: The Evolution of Procedural Warfare in the Modern U.S. Senate. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Snyder, James M.Jr. 1991. “On Buying Legislatures.” Economics and Politics 3 (2): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0343.1991.tb00041.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Sunstein, Cass R. 2022. The Rule of Law vs. ‘Party Nature’: Presidential Elections, the U.S. Constitution, the Electoral Count Act of 1887, the Horror of January 6, and the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022. Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 23-16. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4313291 (accessed October 1, 2023).10.2139/ssrn.4313291Suche in Google Scholar

Thomsen, Danielle M., and Aaron S. King. 2020. “Women’s Representation and the Gendered Pipeline to Power.” American Political Science Review 114 (4): 989–1000. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055420000404.Suche in Google Scholar

Warren, Mark E., and Jane Mansbridge. 2016. “Deliberative Negotiation.” In Political Negotiation: A Handbook, Jane Mansbridge and Cathie Jo Martin, 141–96. Washinton, DC: Brookings Institution Press.10.5040/9780815752332.ch-005Suche in Google Scholar

© 2026 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.