Abstract

This study describes the narratives of innovation produced in a knowledge-based company, constructs them into core stories and develops a narrative framework suitable for researching the topic. The research data consisted of thematic interviews with 23 professionals from the Finnish technology company. Innovation stories were convoluted, identifying innovation-framing contexts that were related to ownership, drivers, continuity, decisions and values. Based on these narratives, the study generated the 4Co (context, content, conflict, and compromise) analytical framework suitable for examining narrative data in innovation research. The study also produced an ideal description of innovation as a simultaneously shared and personally meaningful evolutionary learning process that takes place in small steps and requires a balance of necessity and freedom as well as decision-making based on intuition and facts, producing human efficiency as a value for employees and the organisation. Based on the findings, scientific, methodological, and practical discussions are also presented.

1 Introduction

The changing working life creates more and more diverse requirements for innovation, learning, and creativity, thus bringing out the many features and sides of these phenomena. Innovations are at the center especially in knowledge-based organisations where new things are created through workers’ continuous learning and development of expertise. Innovation research typically focuses on the fields of technology, management, and organisational research and psychology (Brem et al. 2016), but the examination of innovation has also become part of, for example adult education scientific research in recent years (Billett et al. 2022; Lemmetty and Billett 2023) due to new innovation approaches. Thus, innovation research has developed and diversified over the decades (Anderson et al. 2014; Edwards-Schachter 2018), opening several perspectives on the nature and role of innovations.

In literature, many dichotomies associated with innovation – that is, differences between opposite perspectives (Branco 2009; Cambridge Dictionary 2023) – can be discerned (Nilsson et al. 2012). For example, the understanding of innovation as organisation’s strategic, top-down process producing technological or economical value has been accompanied by new perspectives from the field of employee-driven innovation, where the learning and strong participation of personnel have been seen as the starting point of innovation for organisational development (Billett et al. 2022; Lemmetty and Billett 2023). Dichotomies appear as a way to structure research-based understanding of innovations and bring out their complex nature (see Edwards-Schachter 2018) from different perspectives. At the same time, dichotomies contain the risk of simplifying things into descriptions divided into two. Instead, we should strive for a dualistic conception of duality, based on the idea that things are in constant interaction with one another and not separate (Branco 2009). Lundvall (1992) description of innovation as a phenomenon that involves the continuous process of learning – searching and exploring – which leads to new products, technologies, organisational forms, and market innovations, is an example of how different innovations can be converged into one definition. Individual empirical studies are rarely able to show innovation dichotomies as a whole, let alone present solutions to them or bring observed oppositions together. This is partly due to methodological challenges, as many innovation studies are quantitative (Pajuoja 2022) and thus do not seek to understand innovations as multi-level and multidimensional entities.

In recent decades, organisational research has moved from a methodologically rational modern view toward a socioconstructivist approach, seeing the study of storytelling and narratives as key to understanding the meanings (Auvinen et al. 2013). There have been numerous analyses of narratives in organisational research (Boje 2008; Gabriel 2004), but few studies focusing on innovation narratives. Existing narrative innovation research has mainly focused on how (innovation) narratives appear and what their role is in different (real-time) problem-solving and innovation processes (Pedersen and Johansen 2012), as in the transition of an idea into an innovation (Sergeeva and Trifilova 2019). Some studies have been interested in how innovation narratives affect various key challenges faced by the organization, such as organisational efficiency (Bartel and Garud 2009), sustainability (Bartel and Garud 2009) and ambidexterity (Maclean et al. 2020).

However, a deep understanding of the role of different stories and narratives related to understanding, meaning and experience of innovation as a phenomenon is needed, as it is the narratives that guide the activities of organisations and are central to the progress of the different stages of the innovation process (Pedersen and Johansen 2012). Through narratives, it is possible to understand the dichotomies associated with innovations by gaining access to the ways of speaking through which people construct their views, focusing on time, place, and position (Burr 1995). By looking at the narratives of those working in the organisation, including their similarities and differences, it is possible to distinguish the organisation’s dominant integrated narratives from the shared stories that are formed from them (Boje 2008). At best, the resulting innovation stories bring out the meanings built in the organisation (Bruner 1986), which shape the social reality of the organisation (Berger and Luckmann 1966). In this way, they function as a communication tool in the contexts of innovation and organisational research and practice.

This research approach innovation and related narratives from a data-driven and dichotomous perspective, but with the intention of achieving a dualistic understanding of the interconnectedness of different aspects. In the next section, I describe some key starting points in relation to innovation dichotomies and the narrative approach. I then present the research’s aim and questions and describe the methodology, data, and analysis process. I highlight the five types of innovation stories that arose as a result of the research. Finally, I consider their relationship to previous knowledge and the research’s contribution to the field of narrative innovation research.

2 Innovation dichotomies

Innovation often refers to the creative idea, its practical implementation, and the desired end results (Anderson et al. 2014; Cumming 1998; Greenhalgh and Rogers 2010; Schumpeter 1934; Scott and Bruce 1994). Innovation has thus been approached as both a process and a finished outcome. From a process point of view, innovation is mainly divided into two key stages: the formation of an idea and its practical implementation (Koziol and Koziol 2019). Although both stages are extremely important for the development of innovation, the division emphasises the separate nature of the stages, reflecting a central dichotomy in innovation research. The division between the creation of an idea and its concrete implementation is related to a wider discussion on the distinction between creativity and innovation: Creativity focuses specifically on the creation of new ideas, while innovation as a process focuses on combining these ideas and their practical implementation (Amabile 1996; Anderson et al. 2014; De Jong and Den Hartog 2007). Through this process, the result – innovation – is created.

In the history of innovation research, innovation as an outcome has been seen as strongly attached to products or technologies (Høyrup 2010). In recent decades, a large part of innovation research has focused on product and technology innovations (Abernathy and Clark 1985)(Abernathy and Clark 1985; Cumming 1998; Johannessen et al. 2001). This goes back to Schumpeter’s (1934) concept of innovation in which innovation is particularly a technological output. Since then, as innovation research has developed, the idea of innovation as an end result has expanded. Today, innovations encompass a wide variety of market, organisational, and social innovations as well as innovations related to sustainable development (Edwards-Schachter 2018; Mead et al. 2022).

While our understanding of different innovations has grown, the view of who develops innovations has changed. In the history of innovation research, innovations have been seen as solutions or breakthrough products implemented by a specific, often small group of people (Høyrup 2010; Voxted 2018). For example, product developers or entrepreneurs are described as innovators, whose work is basically seen as the development of something new. In addition, innovations have been seen in organisations and their research as extensive top-down processes (Høyrup 2010), although the understanding that anyone can act innovatively (Tidd and Bessant 2009; Voxted 2018) and creatively (Amabile 1996) has increased over the years, bringing a new view regarding the role of employees at any level of the organisation in the development of innovations. This is realised especially when innovations are seen not only as technological product innovations but also as new organisational practices or ways of operating (Høyrup 2010). Consequently, the novelty and value aspects of innovation have multiplied.

Technological innovations are most often associated with radically new breakthroughs, but looking at organisational innovations helps us understand the different levels of novelty: today, it is understood that innovations can be both radical and incremental, with the ability to change entire industries or bring progress little by little (Voxted 2018). The idea of defining novelty value from different perspectives is combined with a model developed in creativity research, where creativity and its outcomes (e.g., innovations) can be categorized as either significant (big) creativity or minor (little) creativity (Kaufman and Beghetto 2009), depending on whether they produce novelty value for a large group of people or entire societies or for a single person or small group of people.

Innovation was originally defined by Schumpeter (1934) as a new thing that creates economic value. This approach has long guided innovation research (Høyrup 2010). In society and organisations, the story of innovation and creativity has been told in terms of drivers of economic competitiveness, as well as increasingly as a solution to various social, ecological, and human problems and challenges (Edwards-Schachter 2018). Innovations are thus largely connected to a positive discourse accepted and internalized by scientific and working-life communities. As a result, innovations are typically seen as solutions, means, and commodities that bring changes producing positive value. However, the definition of innovation – as well as creativity – does not largely take into account the positive rather than negative nature of the end results (Kampylis and Valtanen 2010). In recent years, creativity and innovation research has involved a way of speaking in which innovation is examined critically (Coad et al. 2021; González-Romá and Hernández 2016), including the consequences or requirements and the goals of the creative actor (Kampylis and Valtanen 2010). Among other things, the idea of the creative destruction contained in innovations has emerged in the discussion (Glaveanu 2019).

The dichotomies attached to positive and negative hegemony (Coad et al. 2021; Josefsson and Blomberg 2019), innovative actors and industries, and the material and immaterial characteristics of innovation (Koziol and Koziol 2019) processes comprehensively describe the fragmentation and multiplicity that prevail in innovation research. It is important to be aware of these dichotomies and to try to understand them to produce a new understanding of how innovations are talked about in our time and what kinds of stories are being told about them.

3 Narrative approach to innovation

Based on the previously described definitions of innovation, we can see that innovation appears as a sociocultural and multiple phenomenon (e.g., (Glaveanu 2019), which is constructed through the interaction between actors, environments, and communities. Innovation is thus both an activity tied to the cultural-historical context, where it gains its significance, and an ongoing continuum of development work maintained by different actors in their everyday lives (Lemmetty and Billett 2023). When innovation is approached this broadly as a sociocultural whole, it can be expected to become visible through the stories, ways of speaking, and meanings constructed within an organizational context.

The field of innovation research has long focused on business economics and organisational and management research. Traditional approaches have emphasised a rational modern view (Auvinen et al. 2013). However, over time, a postmodern and socioconstructivist approach to research has emerged, broadening the horizon of innovation research. Socioconstructivism is based on the view that knowledge, reality, and their structures and phenomena are constructed in social and linguistic interaction (Gergen 1999). This postmodern approach is known as the cultural paradigm (Hatch and Cunliffe 2006; see also (Auvinen 2012). At the core of the cultural paradigm are a holistic understanding of people and an examination of socially formed meaning networks. The narrative paradigm, related to the aforementioned approaches, sees people as storytellers. People reason and make decisions based on culture and situations that are built through stories (Auvinen 2012; Fisher 1987).

In organisations, stories and storytelling are central phenomena. Based on people’s experiences, they offer an opportunity to construct, make meaningful, and share an understanding of the organisation. In addition, they help create a shared vision of the organisation’s future (Gabriel 2004; Reissner 2005). Telling innovation stories is an effective way to strengthen innovation-related cultural norms and values in the organisation (Garud and Turunen 2017). Through stories, organisations can convey and strengthen the importance and role of innovation in the organisation’s success.

David Herman approaches narrativity as an intentional whole that can be examined using his CAPA model (context, action, person, ascription). Herman et al. describes the components of the model as follows (2012: 50):

Context: contexts for interpretation (including contexts afforded by knowledge about narrative genres, an author’s previous works)

Action: actions performed within those contexts and resulting in texts that function as blueprints for worldmaking.

Person: persons who perform acts of telling as well as acts of interpretation.

Ascription: ascriptions of communicative and other intentions to performers of narrative acts – given the contexts in which the persons at issue perform those acts and the structure that their resulting narratives take on.

The basic assumption underlying the CAPA model is that all social interaction can be analyzed using the concepts provided by the model. Herman et al. (2012) justifies the model’s advantages by stating that it offers a single framework for studying both the action of producing a narrative world and the non-verbal as well as verbal actions of characters within narrative worlds. Additionally, the model assumes that attributing communicative intentions to storytellers is part of the narrative interpretation process itself (Herman et al. 2012): storytelling is part of action, not just a detached description. This narrative approach opens up new perspectives for innovation research, emphasising the importance of storytelling and meaning building in organisational innovation processes (Sergeeva and Trifilova 2019). Equally, storytelling among organisational members can produce a shared understanding of innovation (Perkins et al. 2017): what innovation means in this organisation and in the experiences of its staff. Since innovations are creative processes that are often difficult to visualize, they can become easier for staff members to understand through stories (Pedersen and Johansen 2012).

Narrative research enables a comprehensive understanding of contexts of innovation (see also Herman et al. 2012). According to Garud et al. (2010; see also Garud et al. 2014), the starting point in the narrative innovation perspective is the idea that actors try to contextualize innovations through relational, temporal, and performative starting points. Relationality emphasises the actor’s or narrator’s relationship with the environment and the community and their own actions in relation to existing opportunities. It is about the formation of agency. The temporal dimension refers to the different descriptions of the past, present, and future that are offered as the innovation develops. The performative perspective emphasises how narratives act as triggers for action toward goals that are constantly changing. These three aspects –relational, temporal, and performative – form a narrative toolkit that can be used to visualize how actors form an innovation (Garud et al. 2010).

Since the concept of innovation and understanding it is complex, and often tied to technological details, phases, or other reductions, this study aims to understand the cultural, social, and contextual dimensions of innovation through narrativity as part of a cultural paradigm. The narrative approach enables a data-driven examination of the ways key actors talk, but also create a cultural foundation for innovations.

4 Research aim and questions

This study aims to describe the narratives of innovation produced in a knowledge-based company, construct them into core stories and to develop a narrative framework suitable for researching the topic. The purpose is to bring out not only the dichotomous perspectives attached to innovation stories but also the dimensions that make these perspectives converge. The research questions were formed as follows:

What kinds of innovation core stories can be formed from the narrations of the professionals of a knowledge-based technology company?

What areas do these innovation core stories consist of?

5 Research design and narrative methodology

This study uses narrative methodology. The narrative research strategy is based on social constructionism, according to which reality is constructed in social interaction (Berger and Luckmann 1966) and in the experiences that arise at the intersection of interaction and the real world (Polkinghorne 1988). Narrative has many different meanings and definitions, but it has most often been described as synonymous with storytelling. The narrative research method is based on the idea that stories reveal truths about the experiences of the person being studied (Riessman 2008) and their significance in a certain time and context (Polkinghorne 1995). In this meaning-making process, plot, intrigue, and narrative structure play central roles (Polkinghorne 1995). The story told by a single individual is attached to the context and environment in which it is told and takes shape as a subjective description. The result is a unique description of the experiences: a story that can be based on the same facts but differ a lot from the version of another interpreter, with each interpreter having a unique interpretative frame of reference based on their own history and experience (Polkinghorne 1995). By combining the narratives of actors operating in the same context into broader stories, a more versatile overall picture of certain phenomena or events can be created. Since the same events give rise to different narrative accounts, depending on the context and point of view (Auvinen 2012), the construction of communal stories can make visible the relational, temporal, and performative dimensions of the phenomenon under study (Garud et al. 2010) and reveal dichotomies occurring in the context and their solutions.

5.1 Context, participants, and data

The target organisation of this study was a medium-sized Finnish international technology company whose business was the production of high-quality products based on top science and innovative technology. The target company employed around 300 people in different functions and was divided into different departments and teams. Personnel from three departments participated in this study: administration, product development, and production. These were chosen not only because they were key players in the company’s operations and in the goal of producing quality products but also because they were different in terms of the content of their work. Like most of the narrative studies in human sciences today (Riessman 2008), the data for this research were based on interviews. A total of 23 employees participated in the study, of whom five worked in production, 10 in product development, and eight in administration and management. Some of the participants were invited to participate in the study randomly, while others were invited because another participant had described their role as central to organisational innovation. The study followed the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration at all stages. No separate ethical approval was required because the participants were not children, animals or patients; rather, they were adults who anonymously and voluntarily agreed to participate. The participants were given a written copy of the research release, privacy statement and participation form to read before taking part in the study. These, together with the ethical principles of the study and issues related to anonymity, were also discussed verbally before the interviews. Each participant volunteered to take part in the study by signing a written consent form.

The interviews were conducted in autumn 2022 as semi-structured thematic interviews in which participants were asked to share their experiences of innovating and innovations in the organisation. The interviews lasted from 45 min to 2 h. Participants were encouraged to tell stories about innovation processes and innovation culture and to think about what innovation means in their own opinion. Additional questions included the following: What comes to your mind about innovations in your work? What kinds of innovations do you think are being developed or are expected to be developed in this work context? What kinds of development and innovation processes have you been involved in?

5.2 Narrative analysis for innovation stories

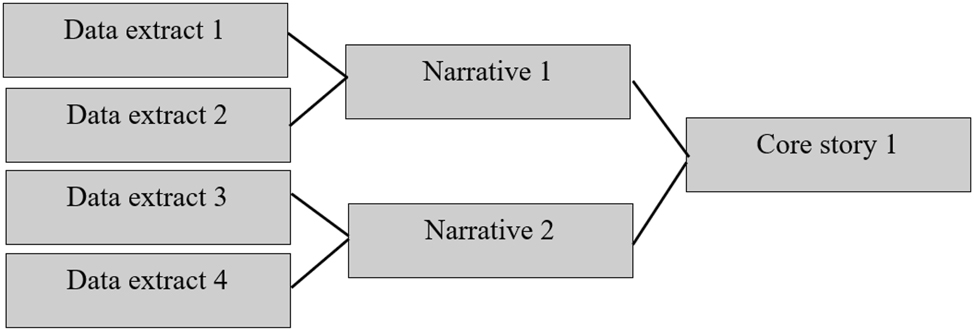

Storytelling is an emerging trend in social constructivism. It is now considered one of the most important ways in which people structure and construct their understandings of the world, life, and themselves (Cortazzi 2011). This study used narrative analysis (Polkinghorne 1995) as an analysis method, proceeding in three stages (see Figure 1). Before the start of the actual analysis, the transcribed data were read through twice to form a general understanding, while making notes on the key events related to innovations immediately observed in the data. In accordance with narrative analysis, in the actual analysis, the descriptions of the innovation processes and experiences from participants’ narratives were examined in detail. The narration was approached as a chronology (i.e., a causal story) built up along with the plot (i.e., a narrative), paying particular attention to how the different depicted stories or the characters’ own actions led to later events in certain circumstances (Elliott 2005; Polkinghorne 1995). In the analysis, the narratives appearing in the interviews (i.e., individual events and narrated experiences; Abbot 2008 (Abbot 2008)) were first located and then structured into a logical order, outlining the key moments, twists, and consequences in the events and experiences described, which connected to the contexts and environments in which they were produced (Spector-Mersel 2010).

Example of the data analysis process.

In the second stage of the analysis, the observed narratives were cross-examined, paying particular attention to the similarities and differences in the contexts conveyed in the backgrounds of the narratives. Narratives attached to the same context were seen as forming a mutual conflict, but also related solutions (i.e., compromises). These data fragments were thus structured into their own categories. In the third stage, by taking a closer look at the previously observed narratives, core stories were constructed that described the innovation speech in the everyday life of the organisation and whose purpose was to summarize the narratives and the stories that arose from them to make them easier to understand (Emden 1998). The construction of the stories proceeded in a data-based manner by assembling into stories various structural elements attached to the innovation speech in each category of the previous stage, including the description of the context, the narrator and other actors appearing in the story, their evaluations, and the conclusion (Labov and Waletzky 1997). The main point of the story does not refer to the temporal conclusion of the event (Labov and Waletzky 1997) but to the resolution of the conflict described in the story, which was observed during the analysis of the stories. The construction of core stories was part of the analysis phase, as through them, it was possible to confirm which aspects, phases, and connections – from which the plots of the innovation stories could be built – appeared in the narratives (Riessman 2008), thus answering the second research question.

Based on the analysis, the core stories were structured in the following way. Each story begins with an introduction, providing the background and context. Next, the two central opposite sides are attached (i.e., the dichotomy containing the conflict between the two sides). The story ends with the compromise that appeared in the narratives, which appears as a kind of solution to the dichotomy. The stories were named after the compromise that was eventually built from the opposite sides of the characters in them and the context behind them. In the core stories presented in the results section, the original word choices and expressions of the interviewees have been preserved as closely as possible. The narratives of the same interviewees can be found in several stories, and the stories are thus not based on the narratives of certain individual interviewees.

6 Findings

Five core stories about innovations were built from the data. These stories describe innovation in five different contexts: innovation ownership, innovation drivers, continuity of innovation, innovation decisions, and innovation value. Each story contains at least two opposite sides, which not only appear in conflict but are also connected to each other due to the presented compromise. The results are presented story by story. First, a core story describing the result category is presented, after which its key parts (i.e., the content that forms the dichotomy and the compromise) are described in detail, supported by the original data extracts.

6.1 “Personal but shared”: the story of innovation ownership

Here, ideas develop, refine, transform, and build into innovations. There can be many and diverse ideas in various stages of the process. We, as experts, possess a lot of knowledge and are, in a certain way, confident, wanting to create something new. In such a perspective, it’s important to be able to feel that you’ve accomplished something and say, “I’ve come up with or developed a product or a new way of doing things”. In this viewpoint, there are also dangers of self-centeredness that have emerged in the history of this organisation, especially when the significance of individuals was more pronounced and stronger. Excessive ambition or selfishness is not good because it leads to conflicts within the group. It’s also not a good thing because in today’s world, innovation – such as a new product or approach – cannot be developed from start to finish by a single person in such an organisation. Developing innovations is so much more complex and requires much more diverse and specific expertise nowadays, so few individuals can possess such skills. Therefore, it’s important that we fundamentally understand these innovations as shared and collective. They come about through compromises, refinement, collaboration, comparing and blending of ideas, and communal learning. Excessive humility – never expressing one’s opinion or offering criticism to others – is also not beneficial. The essence of innovation is not whose idea a particular thing is or whether someone receives a personal reward for it, but rather the shared experience of success and significance – understanding one’s role as part of something larger. Thus, the focus should be on what has been created, rather than emphasising who created it.

Ownership appears as a key context in the participants’ innovation experiences. In this story, the individual level and the communal level are emphasised, which are weighed from the perspectives of motivation and meaning, as is evident at the beginning of the story.

There was a lot of personal self-talk in the data, with the narrators emphasising their own visions, expertise, and experience, as well as the ideas formed based on them. Narratives describing the ambitions and strong – sometimes even selfish – ways of individuals who have worked in the organisation now or in the past also told us about personalities and their need to make their own ideas turn into innovations. The perspective of personal ownership of innovations was emphasised particularly in those narratives focusing on the company’s history. The story emphasises the idea that when the company was smaller, individual people had more visible importance for innovation, and thus ownership was distributed to a few. In the same way, previously problem-solving work and innovation were more individually manageable, so processes could be promoted by relying on the expertise of individual people. As the company grew and the industry developed, the importance of individual people was not seen to decrease, but harmful ambition and the personification of innovations were seen to endanger the culture of innovation and produce conflicts within the organisation:

There used to be a lot of fighting; we couldn’t come up with anything without having two competing ideas, and neither of us wanted to give up. But sometimes that competition was so bloody that it just wasn’t fun. (H10)

It hurts a lot if your own idea doesn’t make it into the final product. (H2)

The experiences of innovation that describe modern times emphasize shared ownership of innovation instead of personal ownership. A single innovation – whether related to a product or an organisation’s practices – requires multi-level and versatile expertise and the combination of several ideas. In the narratives set in modern times, there was thus talk of “cooperation”, “us”, and “sharing”. A sense of community was attached both to the cooperation between actors within the company and to networks and stakeholders outside. However, risks were also described in relation to communality. As the quote below shows, excessive humility and the need to please all actors (from customers to internal actors in the organisation) is problematic and at worst eats away at the innovativeness of innovation.

That the innovation is not tried to be squeesed so that it works for everyone. We cannot always satisfy the needs of all people with a certain solution, but different solutions are needed for different people. Because what happens is that if we try to make everyone’s wishes come true, then we will lower that bar for everyone else if we make too many compromises. In such a situation, that innovation is watered down if we try to make it suitable for too many people. (H8)

The story’s compromise is a description of innovation ownership as personal and shared at the same time: a collaboration where not only each actor’s ideas but also their critical evaluations of other ideas and actions are essential. The joint output is celebrated together, recognizing not only the importance of the group but also the role of each participant as part of the group.

Ambition is dangerous. But humility is also a bad word. Too much self-ambition is poison. But also, in the other hand, if you put yourself in such a position that you expect someone to do something for you or decide, it doesn’t really work. The most important thing is not who invented something, but what was invented. And for that, there are ways of how it should be done, so that there is not too much ownership of those ideas, that at an early stage we should talk about those things with as many people as possible, so that what we are doing becomes a common thing. (H4)

6.2 “Motivating necessity”: the story of innovation drivers

A crappy product was born from a starting point where none of us wanted to do it the way we had to. There was creativity even in that situation, but that creativity isn’t very motivating when we are forced to come up with ways to create something new or advance work within tight constraints. It’s a bit like innovations forced by necessity during wartime. There, necessity motivates because there’s so much at stake. However, this is not a war, so excessive compulsion adversely affects work motivation and leads to poor results. If this compulsion becomes too prevalent in the culture, people also learn to expect that all the answers are provided for them. On the other extreme are situations where you can do whatever you want. In the past, it was more common to have the freedom to work on things that were not directly related to a specific product. Nowadays, there is more urgency, which reduces freedom. Here, we have also seen that excessive freedom leads to individualism, and once again, we are on thin ice. Adequate courage and the opportunity to make decisions, to experiment, and even to play with ideas are important prerequisites, which fortunately are often realised in our work. In such cases, compulsion is in the right proportion, helping us understand expectations while also providing sufficient freedom and flexibility. Because we are talking about work where innovation is so crucial, creating something new is always more or less obligatory. Typically, these boundaries exist here; sometimes they could be more clearly defined, and there is enough freedom. Supervisors don’t shout, and mistakes are not punished. In such a scenario, compulsion is motivating and acts as a driver for innovation.

The second story describes how the company struggles between necessity and freedom. In this case, the narratives are contextualized to the drivers behind innovation.

The data contained narratives about excessive necessity and the problems caused by it, which appeared as a weakening of work motivation and poor results. The factors producing coercion were urgency and the strong and guiding views of those in formal or informal positions of power. The conflict between the opinions of the individual narrators and certain actors belonging to the community appeared to the narrators as a “compulsion”, in which they must submit to the strong guidance of another. The narratives focused on experiences of duty, compulsion, fulfillment, demands. These experiences were described as weakening the motivation of those working in expert work, the desire to innovate, and, at worst, the quality of the end result:

So, dictated by necessity [we create something new], and therefore there are constantly those older [employees] there who have seen everything here, and they remind me that work motivation is quite lost at the moment, and I can’t do it; we have had to come up with all the means by which we’re even able to run this business … it [necessity] would be a good motivator … if they came in the right proportion; then it would be ok. (H 16)

The role of freedom for innovation was mainly emphasised in the interviews as a synonym for an open atmosphere and a safe culture; thus, it was described as a positive driver. In the same way, the material produced narratives about excessive freedom, which could lead to individual-oriented activities, forgetting the organisation’s goals, and thus inappropriate results. Excessive freedom was described as leading to uncertainty about what the organisation was aiming for. Moreover, it was seen to cause “clutter”, which took activities in inappropriate directions and caused confusion in the community:

It’s a fairly open work community, and there needs to be a safe atmosphere so that people dare to say their own opinion, what works, and what doesn’t; otherwise, those ideas won’t come, and they’ll get buried in the creator’s head at worst, and that’s not good. But at the same time, the decisions have to be made; otherwise, nothing will happen, so you have to sometimes take that role and say that we will do it this way. (H10)

As a kind of compromise, the situational relativity of necessity and freedom was formed in the story, as in certain work situations and events, necessity appeared as a natural part of work and – together with sufficient freedom – as a motivation. The structure of the story thus becomes a narrative about necessity and freedom as conflict-sensitive extremes that are sometimes slipped within the framework of a harmonious everyday life that contains enough freedom but also some necessity. Through these narratives and the story formed from them, necessity and freedom are attached as prerequisites to innovations.

6.3 “Evolution in steps”: the story of continuity of innovation

Big innovations, those products or truly significant organisational changes that have a major impact on the development of this company, are seldom celebrated. That’s why it’s difficult to grasp innovation as a whole. Innovation in this work involves solving small problems as part of a larger whole. We break down individual problems or complexities into smaller parts and seek the best solutions for them. The difficulty then lies in the fact that our experience is not that we innovate or build innovations. Those small pieces, small advancements, don’t feel meaningful or valuable from an innovation perspective. Instead, the value and sense of achievement should come from the journey of continuously learning a little, moving step by step forward. Sometimes you must pause to look at that journey – to see the leaps forward that all those small parts and steps have taken you. We have a lot of staff who have had long careers in this organisation. They can see that journey and the bigger picture and understand the significance of individual steps. Individual products or end results are always built on the background of new products or outcomes. Temporally, it’s an evolution. It’s about constantly innovating, but in small steps.

In the third innovation story, the context shows the continuity of innovation: a temporal dimension where innovation can be viewed and understood by looking not so much at what lies ahead but at history.

In this story, the concept of innovation is portrayed as problematic for the story tellers. The narratives highlighted reflections on what innovation is in the end. Innovation as some significant, great invention was mirrored in the great innovations that have occurred in the history of the world, as was evident in the narrative below. Compared to these historically significant innovations, the narrator’s own innovation experiences were described as modest:

The term innovation is tricky here because the world is full of the real Leonardo da Vincis and Benjamin Franklins, who have really invented big things, but I can’t claim that I invent the same kind of gold every day. Sometimes a little gold is born, but I don’t know if it necessarily ends with a product. (H8)

However, in the narratives, the participants felt that they were also innovating. They described innovation as being linked to continuous problem solving and the individual small actions, ideas, and development steps taken in daily work. These appeared to the authors as everyday events, which is why conceptualizing them as innovations – or even as parts of innovation – was difficult, although it became clearer as the interviews and narrations progressed.

The most difficult thing is to understand what innovation is. [In a certain area,] that innovation might be a drop of glue on the edge of the membrane that made the whole thing work. Or, if we discover a defect in the product, isn’t that also an innovation? (H11)

The compromise in this story is that innovation is a kind of evolutionary chain of events, where every small step is essential in terms of the end result and its continuity and further development. This understanding of evolution was described as important for appreciating and enjoying the work and everyday activities:

I can show photos of our current product [parts] and the older ones, so it hasn’t always felt like it was some kind of innovation, but they’ve changed an awful lot over the years, and I guess it’s, I don’t know, evolution … I don’t know if innovation has to be, like bigger than evolution. I don’t know. (H10)

6.4 “Balance of the facts and intuition”: the story of innovation decisions

In this work, we are in a certain way in the middle ground between art and science and at their interfaces. Much of that innovation is intuitive. You must have enough knowledge, understanding, and experience in the matter to be able to justify to yourself and others why you do what you do. That intuitiveness is based specifically on tacit knowledge of the identity of this company – some kind of feeling or idea of what is right or wrong. On the one hand, research, measurement, and facts play an equally central role here. We aim to do background work – we even do research ourselves – as the basis for their innovations. On the other hand, we also measure how any prototype works or what kind of effects the finished innovation has. At its best, intuition and facts live in symbiosis here, creating a foundation, especially for decision-making, which is hugely included in innovation processes. Some of those decisions are ones that we can make in everyday life, such as what to try or what would be central in terms of development and learning. However, there are also decisions that we employees cannot make. Sometimes there are competing ideas here that have already been developed, but neither can be completed. In this case, many different people participate in decision-making, and it is guided by many perspectives; the role of management is also central. Ultimately, the polyphonic combination of subjective and objective is typically – and at least should b – the background of the decision that guides innovation. This is not always the case, and even such a starting point for decision-making is not simple. It is challenging to make decisions when, objectively evaluated, there are two or more equally good alternatives, in which case the decision must be based on a subjective view, i.e., intuition. People look at the world from different perspectives – from their own experience – so the perspectives can be very contradictory and far from each other. It is essential to ask for whom it is being done or from what point of view value is sought. In difficult decision-making situations, the view of those who have the most power, responsibility, know-how, and understanding of the company naturally becomes guiding.

Decision-making related to innovation processes is built into the context of the fourth story. Within this framework, the narratives described reflections on the role of intuition and facts in the advancement of innovation.

In the narratives, intuition was spoken of as a “feeling” and “understanding” of things that cannot be directly measured or documented. For example, the company’s identity and vision, as starting points for innovation, were discussed as an understanding based on experience. In several narratives, learning, long work experience, and understanding of the organisation’s culture, practices, and values formed the basis of intuition, which was at the center when decisions were made either about individual experiments at the employee level or about larger strategic choices at the organisational level:

How do we blend it [innovation] into our DNA so that if things have always been done this way, they can’t be done in a completely different way. You have to understand what the company wants. Someone who understands that theory terribly can completely disagree, but that window alone is too small. (H4)

Focusing equally on decision-making, so-called factual speech was emphasised in the interviews. In this speech, views on the role of data, theory, measurement, and testing in decision-making were emphasised. This was described as essential for promoting innovation, as it was necessary to understand the substance-level issues, technology, and operations related to the industry and products, which were real and the same for everyone, regardless of subjective experience.

Of course, the key is the prototype – that when you are allowed to test, it is a good way to make choices; it is the right way. … Well, that [method of testing] is good; that’s what we always aim for here, or else measurement, it gives objective measures. (H7)

The idea of a balance between intuition and facts in a decision-making situation appears as a compromise in the story. It is essential that choices are based on information and reliable metrics, but they should also take into account the organisation’s value base, culture, and ideas of what is right and appropriate in each context. In the end, intuition and facts are not just opposite points of view; in the narratives, intuition was defined as a feeling based on the learning process, knowledge, and experience, which thus had a factual basis, even though a decision made based on intuition was not always easy to describe and structure to others and could cause the community to question the actual basis of the decision:

It’s hard to say; it’s [decision-making is] not just a feeling. I would say that intelligent intuition, it is not a feeling, but it is based on learning, which arises through practice, theoretical knowledge, and doing. At some point, you get a feeling that this is the right thing to do and it’s worth continuing. In practice, however, decisions should be based on measurements and reasoning – substance. Based on subjective experience, there may be differences in opinion, but when tested, it can be proven that this is the best. (H23)

6.5 “Humanely effective”: the story of innovation value

When we talk about product innovations – or organisational innovations that promote product development or production – we are of course talking about money. A company must produce in order to ensure its existence, but the essential question is by what means this financial return is achieved. This organisation has grown tremendously over the years, and it poses challenges for certain types of family assets. Before, everyone knew each other; it was easy to build trust, and thus humanity was self-evident in all activities. Now we must consciously strive to maintain this humanity. On the other hand, there are opportunities here to develop your own work from the point of view of your own well-being: If you have to bang your head against a wall because of a way of working day after day, and if it can be solved with your own ideas, then you can solve it. These everyday solutions develop operating methods to be humane, but they also bring efficiency. A person is a creative being, and it is important that that creative potential is put to use. At the same time, work that does not require a human can be automated. This has been done and will be done, and it does not mean that the work will stop. Human resilience is a key value in innovation also because many innovations are based on long experience – a long working career – and thus it is important that these working careers can be maintained. It has not always been successful, but it is worth striving for. Learning is created through competence and well-being, which in itself is already a value in innovation.

The fifth and last innovation story is based on narratives that emphasised defining the value of innovation. In the interviews, the innovation speech focused on considerations of the company’s existence, financial stability, and competitiveness, but equally on human and social values. The idea of how to increase the efficiency of the organisation and promote the economy while making work more meaningful and supportive of well-being and learning was emphasised in innovation.

Economy, cost-effectiveness, and competitiveness were repeated in the descriptions of “the benefit of the company”. To some extent, this appeared to involve confrontational speech between the company and the personnel. In such a confrontation, these two areas were seen as separate, and each value perspective was brought forward as independent and as its own starting point, as shown in the following excerpt:

The value of innovation comes from where the company benefits the most. From there, I try to find the big lines. You shouldn’t interfere with small things that have no economic significance or that are not very significant in terms of the big operation, but then it should be those that are essential for us to be able to develop new products as rationally and cost-effectively as possible. (H13)

The predominance of an economic or efficiency perspective was criticized in the participants’ speech if it happened at the expense of well-being or other work. In this case, the speech presented perspectives on considerations of humanity and examples of situations where the value of innovation had been shown to be humanely and socially sustainable:

The pace of work is really hectic, so learning is not fun. There are changes all the time; internalizing them is learning, which is not always pleasant. Sometimes there should be a steady time so that you don’t have to worry about changes. … You have to think about what is good enough. It is usually awfully good. Then there would also be time for stopping and learning, daring, and inventing. When we do enough good … then we can manage “to have long working careers – long working relationships in accordance with sustainable development.” (H18)

However, the different narratives about the value of innovation created a larger overall picture of how different values appeared in the context of innovation than the individual narratives. In this story, the view of consequentialism is emphasised as a compromise: human value in the long run also produces financial value, which again promotes the organisation’s human activities. This appears as the continuous development of work from an employee-oriented perspective, where the starting point is the promotion of well-being and the meaningfulness of work, which accumulates into more efficient work for the organisation:

Due to my own natural laziness, I have had the desire to make this job easier so that with as little work as possible, the same end result can be achieved. I think that laziness is creative efficiency. [Tells an example of a development project that started from the person’s own desire to make it easier] … After a few years, our numbers grew. … and we doubled the possibility of how much a certain product could be sold. (H15)

7 Discussion and conclusion

This study aimed to describe the narratives of innovation produced in a knowledge-based company, construct them into core stories and to develop a narrative framework suitable for researching the topic. Through the narrative analysis (Polkinghorne 1995), five types of stories about innovation were formulated, each of which describes innovation from a different perspective. All five stories create an understanding of the context of innovation as well as its content, conflict, and related compromises (see Table 1). Based on the findings, an ideal description about innovation was created: a simultaneously shared and personally meaningful evolutionary learning process that takes place in small steps and requires a balance of necessity and freedom as well as decision-making based on intuition and facts, producing human efficiency as a value for employees and the organisation.

The main findings in the narrative 4Co framework.

| Context | Content | Conflict | Compromise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Personal | Excessive ambition or self-centeredness takes precedence over the group level, while excessive humility hinders a sufficiently critical and multi-faceted debate | From whom to what |

| Shared | Personal things as a part of the joint outcome | ||

| Drivers | Freedom | Total freedom without necessity or forced action without freedom | Situational-based relativity between freedom and necessity |

| Necessity | |||

| Continuity | Evolution | Small everyday actions do not feel like innovations, and, from an evolutionary point of view, one’s own contribution is lost in the big picture | Intermediate results |

| Steps | Individual actions as parts of continuity | ||

| Decisions | Objective facts | Strong disagreements between subjective views or difficulties in assessing objectivity and subjectivity | Balance of the content |

| Subjective intuition | Decision based on both intuition and facts | ||

| Values | Humane | Strong focus on (economical) efficiency at the expense of humanity | Causal relationship between humane values to efficiency |

| Effective (economic) |

The stories formed in this study do not appear to be completely new in the field of innovation research. For example, the understanding of innovation as a shared process has been presented in previous studies, which found that innovation is formed through different phases and group-level activities and that the individual’s role is mainly central to the idea-generation phase (Sung and Choi 2014). There is also an earlier discussion of innovation as an evolutionary process (Ziman 2003). However, this research produces new understanding by underlining the idea of personal roles and ownership and their significance for the whole in relation to long, multi-generational, and communal innovation processes in which the individual’s contribution can be easily lost. Thus, it brings into discussion the motivation and experiences of those doing expert work about the meaning of the work within the framework of this evolutionary and group activity.

Creativity and innovation research has also strongly highlighted the relationship between compulsion and freedom as a prerequisite for innovation (Amabile 1996; Stokes 2014). The relationship between necessity and freedom appears to be both situational and relative in this study. At the organisational level, strategy and goals can always be seen as a kind of frame – or even compulsion – to which personnel must commit, but within these frames, it is important that experts have sufficient autonomy and opportunities to influence so that their motivation and willingness to innovate and develop remains.

The story of human efficiency is attached to the discussion about the nature of innovation. While Schumpeter’s (1934) original view emphasised the economic value of innovation, more and more innovations can be seen as producing social and human value (Høyrup 2010). Especially in research on employee-driven innovation, the promotion of work that brings value to employees from the perspective of improving the quality of working life has been central (Kristiansen and Bloch-Poulsen 2008). At the same time, the improvement of the quality of working life as a goal of innovation has been seen to be in conflict with economic value – or the pursuit of the organisation’s benefit (Lemmetty and Billett 2023). However, in this study, these two values were seen to follow each other, so they were not opposed but mutually supportive. In addition, the discussion about intuition and facts in the interviews was interesting and new, although there are earlier reviews of innovation decisions and their success (Anderson et al. 2014). The decision-making story constructed in this study reveals the complexity of decisions not only among managers but also among staff when they make decisions related to everyday ideas and trying them out.

Temporal, relational, and performative contexts can be observed in all the innovation stories constructed in this research (Garud et al. 2010). For example, in the innovation story about ownership, the talk about personal practices that prevailed in the history of the organisation was emphasised, while regarding development, communal activities were seen as central in the present. In the same way, when it comes to the continuity of innovations, temporality is at the center of the story, as the evolution described as a compromise could be observed by looking more at what had already been done – and relating one’s own role to this – than at what would happen. Relationality is present in all the stories, as they convey reflections on one’s own agency and role in relation not only to the organisation’s operations and culture but also to colleagues and stakeholders. In addition, performativity is strongly described, as in the story built in a value context, where the human development of work is seen to affect the organisation’s efficiency and effectiveness. The narrative approach (Polkinghorne 1995) revealed various dichotomies present in the staff’s narratives and provided solutions to these conflicts. The study found that narratives often described different facets of the same issue within the same context, resulting in both conflicts and compromises. This led to the development of a narrative 4Co model, which involves structuring innovation stories around four key areas: context, content, conflict, and compromise. The 4Co model is fundamentally connected to Herman’s CAPA model (see Herman et al. 2012), considering the context and the actors within it, as well as the causes and effects constructed through narratives for the described themes. However, the 4Co model narrows the focus to a dichotomous approach, aiming to identify extremes and their connections. The goal of the model is partly to construct the plot of core stories, offering a kind of starting point for creating the “dramatic arc” of stories in research. Through this, conflicting but also compromising descriptions can be revealed. The 4Co model can assist future narrative researchers in constructing core stories when exploring similar dichotomies and their resolutions. The study underscores the significance of storytelling within work organisations. Understanding the types of innovation stories produced by the organisation’s personnel is crucial because these stories shape actions and collective thinking, influencing the organisation’s operations. By grasping these narratives, it becomes possible to identify conflicts that hinder innovation. The study emphasises that the compromises discussed within the narratives can play a central role in promoting innovative activities and cultivating an innovative organisational culture.

The identified and constructed core stories of innovation in the study are descriptions of how organizational actors narrate stories of innovation based on their own experiences from the past and their visions for the future. When these stories, once shared and integrated into the collective story of the organization, can practically have the following effects: they maintain a certain type of innovation culture and a shared, general understanding, help make historical and tacit knowledge visible in communities – including a historical understanding that may not necessarily be ‘true’ in the present day but is deeply ingrained due to past strong experiences – and aid in developing leadership and organizational practices towards conflict resolution and generating compromises.

Funding source: Research Council of Finland

Award Identifier / Grant number: 349117

-

Research funding: This work was supported by the Research Council of Finland (349117).

References

Abbot, H. Porter. 2008. The Cambridge introduction to narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Abernathy, William J. & Kim B. Clark. 1985. Innovation: Mapping the winds of creative destruction. Research Policy 14(1). 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(85)90021-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Amabile, Teresa M. 1996. Creativity and innovation in organizations. Harvard Business School Background Note.Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, Neil, Kristina Potočnik & Jing Zhou. 2014. Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management 40(5). 1297–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527128.Suche in Google Scholar

Auvinen, Tommi. 2012. The ghost leader: An empirical study on narrative leadership. Electronic Journal of Business Ethics and Organization Studies 17(1). 4–15.Suche in Google Scholar

Auvinen, Tommi, Iiris Aaltio & Kirsimarja Blomqvist. 2013. Constructing leadership by storytelling: The meaning of trust and narratives. The Leadership & Organization Development Journal 34(6). 496–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-10-2011-0102.Suche in Google Scholar

Bartel, Anna & Raghu Garud. 2009. Role of narratives in sustaining organizational innovation. Organization Science 20(1). 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1080.0372.Suche in Google Scholar

Berger, Peter L. & Thomas Luckmann. 1966. The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin Books.Suche in Google Scholar

Billett, Stephen, Justin Tan, Christopher Chan, Wei-Han Chong & Seong Chang Ju. 2022. Employee-driven innovations: Zones of initiation, enactment, and learning. In William Lee, Philip Brown, Anthony Goodwin & Andy Green (eds.), International handbook of education development in the Asia-Pacific, 1413–1431. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-2327-1_67-1Suche in Google Scholar

Boje, David. 2008. Storytelling organizations. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.10.4135/9781446214305Suche in Google Scholar

Branco, Angela Uchoa. 2009. Why dichotomies can be misleading while dualities fit the analysis of complex phenomena. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science 43. 350–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-009-9105-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Brem, Alexander, Rogelio Puente-Diaz & Agogué Marine. 2016. Creativity and innovations: State of the art and future perspectives for research. International Journal of Innovation Management 20(4). 1–12.10.1142/S1363919616020011Suche in Google Scholar

Bruner, Jerome. 1986. Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674029019Suche in Google Scholar

Burr, Vivien. 1995. An introduction to social constructionism. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203299968Suche in Google Scholar

Cambridge Dictionary. 2023. Dichotomy. In Cambridge dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/dichotomy (accessed 4 June 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Coad, Alex, Nightingale Paul, Jack Stilgoe & Antonio Vezzani. 2021. Editorial: The dark side of innovation. Industry and Innovation 28(1). 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2020.1818555.Suche in Google Scholar

Cortazzi, Martin. 2011. Narrative analysis in ethnography. In Paul Atkinson, Amanda Coffey, Sara Delamont, John Lofland & Lyn Lofland (eds.), Handbook of ethnography, 384–394. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.10.4135/9781848608337.n26Suche in Google Scholar

Cumming, Bruce S. 1998. Innovation overview and future challenges. European Journal of Innovation Management 1(1). 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601069810368485.Suche in Google Scholar

De Jong, Jeroen P. & Deanne N. Den Hartog. 2007. How leaders influence employees’ innovative behaviour. European Journal of Innovation Management 10. 41–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601060710720546.Suche in Google Scholar

Edwards-Schachter, Monica. 2018. The nature and variety of innovation. International Journal of Innovation Studies 2(2). 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijis.2018.08.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Elliott, Jane. 2005. Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Emden, Carolyn. 1998. Conducting a narrative analysis. Collegian 5(3). 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1322-7696(08)60299-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Fisher, Walter R. 1987. Human communication as a narration: Toward a philosophy of reason, value, and action. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Gabriel, Yiannis. 2004. Narratives, stories, and texts. In David Grint, Cynthia Hardy, Cliff Oswick & Linda Putnam (eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational discourse, 61–77. London: SAGE Publications.10.4135/9781848608122.n3Suche in Google Scholar

Garud, Raghu, Arun Kumaraswamy & Peter Karnøe. 2010. Path dependence or path creation? Journal of Management Studies 47(4). 760–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00914.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Garud, Raghu, Gehman Joel & Alberto P. Giuliani. 2014. Contextualizing entrepreneurial innovation: A narrative perspective. Research Policy 43(7). 1177–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.04.015.Suche in Google Scholar

Garud, Raghu & Marja Turunen. 2017. The banality of organizational innovations: Embracing the substance–process duality. Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice 19. 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2016.1258996.Suche in Google Scholar

Gergen, Kenneth J. 1999. An invitation to social construction. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Glaveanu, Vlad P. 2019. Creativity reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

González-Romá, Vicente & Alfons Hernández. 2016. Uncovering the dark side of innovation: The influence of the number of innovations on work teams’ satisfaction and performance. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology 25(4). 570–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2016.1181057.Suche in Google Scholar

Greenhalgh, Christine & Mark Rogers. 2010. Innovation, intellectual property, and economic growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400832231Suche in Google Scholar

Hatch, Mary Jo & Ann L. Cunliffe. 2006. Organization theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Herman, David, James M. Phelan, Peter J. Rabinowitz, Brian K. Richardson & Robyn R. Warhol. 2012. Narrative theory: Core concepts and critical debates. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Høyrup, Steen. 2010. Employee-driven innovation and workplace learning: Basic concepts, approaches, and themes. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research 16(2). 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258910364102.Suche in Google Scholar

Johannessen, Jon-Arild, Johan Olaisen & Bjørn Olsen. 2001. Mismanagement of tacit knowledge: The importance of tacit knowledge, the danger of information technology, and what to do about it. International Journal of Information Management 21. 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0268-4012(00)00047-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Josefsson, Ingela & Alexander Blomberg. 2019. Turning to the dark side: Challenging the hegemonic positivity of the creativity discourse. Scandinavian Journal of Management 36. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2019.101088.Suche in Google Scholar

Kampylis, Panagiotis G. & Juha Valtanen. 2010. Redefining creativity: Analyzing definitions, collocations, and consequences. Journal of Creative Behavior 44(3). 191–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2010.tb01333.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Kaufman, James & Ronald Beghetto. 2009. Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity. Review of General Psychology 13(1). 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688.Suche in Google Scholar

Koziol, Leszek & Maria Koziol. 2019. The concept of dichotomy of the innovation process in an enterprise. In Maria Segarra-Oña (ed.), Smart tourism as a driver for culture and sustainability, 89–101. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-03910-3_7Suche in Google Scholar

Kristiansen, Marianne & Janne Bloch-Poulsen. 2008. Employee driven innovation in team (EDIT): Innovative potential, dialogue, and dissensus. International Journal of Action Research 6. 155–195.Suche in Google Scholar

Lemmetty, Soila & Stephen Billett. 2023. Employee-driven learning and innovation. Journal of Workplace Learning 35(2). 102–118.10.1108/JWL-12-2022-0175Suche in Google Scholar

Labov, William & Joshua Waletzky. 1997. Narrative analysis: Oral versions of personal experience. Journal of Narrative and Life History 7(1–4). 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1075/jnlh.7.02nar.Suche in Google Scholar

Lundvall, Bengt-Åke. 1992. National systems of innovation: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. London: Pinter Publishers.Suche in Google Scholar

Maclean, Mairi, Charles Harvey, Benjamin Golant & John Sillince. 2020. The role of innovation narratives in accomplishing organizational ambidexterity. Strategic Organization 19(4). 693–721. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127019897234.Suche in Google Scholar

Mead, Tim, Sally Jeanrenaud & John Bessant. 2022. Sustainability-oriented innovation narratives: Learning from nature-inspired innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production 344. 130980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130980.Suche in Google Scholar

Nilsson, Susanne, Johanna Wallin, Andre Benaim, Maria Carmela Annosi, Richard Berntsson, Sofia Ritzen & Mats Magnusson. 2012. Re-thinking innovation measurement to manage innovation-related dichotomies in practice. Proceedings from the 13th International cinet conference, 886–904. Loburg: Continuous Innovation Network (CINet).Suche in Google Scholar

Pajuoja, Matti. 2022. From mechanistic measuring to up-to-date understanding: Problematising the study of innovative work behaviour. Vaasa: Vaasan yliopisto.Suche in Google Scholar

Pedersen, Anne Reff & Maj Britt Johansen. 2012. Strategic and everyday innovative narratives: Translating ideas into everyday life in organizations. Innovation Journal 17(1). 2–18.Suche in Google Scholar

Perkins, Guy, Jonathan Lean & Robert Newbery. 2017. The role of organizational vision in guiding idea generation within SME contexts. Creativity and Innovation Management 26. 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12206.Suche in Google Scholar

Polkinghorne, Donald. 1988. Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1995. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 8. 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103.Suche in Google Scholar

Reissner, Stefani. 2005. Learning and innovation: A narrative analysis. Journal of Organizational Change Management 18. 482–494. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810510614968.Suche in Google Scholar

Riessman, Catherine K. 2008. Narrative methods for the human sciences. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.Suche in Google Scholar

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1934. The theory of economic development. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Scott, Susanne G. & Reginald A. Bruce. 1994. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal 37(3). 580–607. https://doi.org/10.5465/256701.Suche in Google Scholar

Sergeeva, Natalia & Anna Trifilova. 2019. The role of storytelling in the innovation process. Creativity and Innovation Management 27. 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12295.Suche in Google Scholar

Spector-Mersel, Gabriela. 2010. Narrative research: Time for a paradigm. Narrative Inquiry 20(1). 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.20.1.10spe.Suche in Google Scholar

Stokes, Patricia D. 2014. Using a creativity model to solve the place – Value problem in kindergarten. The International Journal of Creativity & Problem Solving 24(2). 101–122.Suche in Google Scholar

Sung, S. Yoon & Jin Nam Choi. 2014. Do organizations spend wisely on employees? Effects of training and development investments on learning and innovation in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior 35. 393–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1897.Suche in Google Scholar

Tidd, Joe & John Bessant. 2009. Managing innovation: Integrating technological, market, and organizational change. Hoboken: Wiley.Suche in Google Scholar

Voxted, Søren. 2018. Conditions of implementation of employee-driven innovation. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 22(4–5). 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijeim.2018.092974.Suche in Google Scholar

Ziman, John. 2003. Technological innovation as an evolutionary process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Figures of discourse in prose fiction

- Joseph Conrad’s reluctant raconteurs

- Audience-authored paratexts: legitimation of online discourse about Game of Thrones

- Horizontal metalepsis in narrative fiction

- “Small machines of words”: poetics, phonetics, and mechanisms of narrative realism in late twentieth-century Hip Hop

- Secondary storyworld possible selves: narrative response and cultural (un)predictability

- Explaining the innovation dichotomy: the contexts, contents, conflicts, and compromises of innovation stories

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Articles

- Figures of discourse in prose fiction

- Joseph Conrad’s reluctant raconteurs

- Audience-authored paratexts: legitimation of online discourse about Game of Thrones

- Horizontal metalepsis in narrative fiction

- “Small machines of words”: poetics, phonetics, and mechanisms of narrative realism in late twentieth-century Hip Hop

- Secondary storyworld possible selves: narrative response and cultural (un)predictability

- Explaining the innovation dichotomy: the contexts, contents, conflicts, and compromises of innovation stories