Abstract

Linguistic asymmetries have been of great interest in much research and continue to provide intriguing insights into the working mechanisms of language. Focusing on the domain of speed, we explore the structure of Estonian speed adverbs and provide evidence for the fast-over-slow asymmetry – the tendency for fastness to be expressed more extensively than slowness. As a pre-study, in which we combined dictionary lookup, corpus and rating methods, we compiled a list of 419 speed adverbs, with 369 representing the clearest instances. The main study revealed that the number of unique fast adverbs (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’) is more than four times larger than that of slow adverbs (e.g. aeglaselt ‘slowly’). Comparing the 30 most frequent fast adverbs to the 30 most frequent slow adverbs further showed that the token frequency of fast adverbs, as attested in the Estonian National Corpus 2021, is significantly higher than that of slow adverbs. Nevertheless, the meaning of fast adverbs was not intensified by prefixoids (e.g. hüperkiiresti ‘hyper fast’) and reduplication (e.g. kiiresti-kiiresti ‘quickly-quickly’) more frequently than that of slow adverbs. The study suggests that the widely acknowledged inherent asymmetry in polar antonyms is rooted in the general asymmetry in lexicon, which, in turn, reflects cognitive asymmetries.

1 Introduction

Language is inherently asymmetric. This asymmetry comes in all shapes and sizes. One of the shapes is that of polar antonyms, where one member of the antonym pair is more basic and is often argued to serve as the unmarked or more neutral member of the pair (e.g. Lehrer 1985). For example, large is more basic and less marked than small, and fast is more basic and less marked than slow. Much research has been devoted to such antonym pairs. For instance, there are studies establishing the degree of markedness of antonyms (e.g. Ingram et al. 2016) and its relation to the sequential order of the adverbs (e.g. Kostić 2015; Nithithanawiwat 2023). While these studies on markedness and basicness are highly informative, they tend to focus only on the core terms. For instance, studies typically address the imbalance between the basic terms, such as fast and slow for the speed dimension and small and large for the size dimension (see, for example, Fuchs et al. 2019; Paradis et al. 2015). At the same time, the scalar antonyms typically belong to a larger semantic class, representing the rest of the items in this semantic class to a certain degree. For example, in English, there are many terms for fast speed besides fast (e.g. quick, rapid, swift) as there are many terms for size besides large (e.g. huge, big, great). It is likely that the asymmetries found in antonym pairs are just the tip of the iceberg, reflecting the larger asymmetries within the entire semantic domain.

To more fully understand the inherent asymmetry lying behind polar antonyms, it is essential to investigate the size of this asymmetry in terms of the structure of the whole semantic class from which the antonym pairs are pulled. The current study aims to do that by focusing on (i) the domain of speed, the dimension that frequently acts as the prime example of polar antonyms; (ii) adverbs, a word class that has received relatively less attention than adjectives despite its high importance in languages; and (iii) Estonian, a Finno-Ugric language of high manner saliency.

The further rationale for examining speed lies in its high cognitive importance. Experiencing and interpreting the speed of various actions and processes is essential in everyday life. Most processes can be described in terms of how fast or how slowly they evolve. Thus, whenever we talk about processes, information about the speed of their evolution may be linguistically encoded. Furthermore, many studies have shown that expressing speed in language is critically important. For instance, speed can distinguish between motion verbs of diverse semantics (Malt et al. 2008; Taremaa 2017; Vulchanova and Martinez 2013), and speed adverbs form an essential category within the class of adverbs in languages in general (Hallonsten Halling 2018). The latter further stresses the need to investigate the distribution and internal structure – both from the semantic and morphological angle – of the category of speed adverbs. Most importantly, speed seems to be expressed unevenly in languages not only regarding antonym pairs such as quickly versus slowly but also with fast motion being expressed more frequently and by more diverse means than slow motion in general, resulting in the fast-over-slow bias (Taremaa and Kopecka 2023a). Furthermore, fastness seems to be profoundly intense as compared to slowness in that visual fast motion and linguistic realisations of fastness tend to be processed faster than those of slowness (Ben-Haim et al. 2015; Stites et al. 2013). This suggests that cognitively more salient attributes are also intensified in language one way or another.

The purpose of this study is to test the suggested presence of the fast-over-slow asymmetry in speed adverbs that would go beyond individual antonyms. For that, we first need to systematically identify speed adverbs and their approximate amount in Estonian (pre-study). Then, and to test the fastness-bias in language, we need to reveal the semantic distribution, frequency and intensification degree of fast and slow adverbs (the main study of hypothesis testing). Following the suggestion for the fast-over-slow asymmetry, the principal question is whether fast adverbs are distinct from slow adverbs in terms of their numerosity and use. The hypotheses suggest that

fast adverbs are more numerous and frequent than slow adverbs (Hypothesis 1) and

the meaning of fast adverbs is more likely to be intensified by word-formation mechanisms (such as prefixation and reduplication) than that of slow adverbs (Hypothesis 2).

For the pre-study, we conducted a vocabulary study of speed adverbs in Estonian, combining dictionary lookup, corpus and rating methods. The hypothesis testing study is based on the results of the pre-study (the number and characteristics of speed adverbs) and frequencies of speed adverbs as attested in the Estonian National Corpus 2021 (Koppel and Kallas 2022).

We define ‘speed adverbs’ as adverbs that express the pace at which an event or process unfolds (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’ and aeglaselt ‘slowly’). Even though speed as such is continuous, ranging from extreme fastness to slowness, in language this continuum is not necessarily expressed by lexical items. Consequently, and even though, for instance, motion verbs can fill this continuum from expressing slow to fast motion (Taremaa 2017: 123–124), adverbs seem to be categorical and do not fill such a continuum. Thus, broadly speaking, speed adverbs can be divided into adverbs expressing slowness (e.g. aeglaselt ‘slowly’, tasapisi ‘gradually, slowly’) and adverbs expressing fastness (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’, ruttu ‘quickly, speedily’). Henceforth, we label the former as ‘slow adverbs’ and the latter as ‘fast adverbs’. There seem to be no specialised adverbs of speed that would convey medium speed in Estonian (medium speed can be expressed by general degree adverbs with no specific relatedness to speed; e.g. mõõdukalt ‘moderately’, parajalt ‘moderately, appropriately’). For this reason, our study revolves around fast versus slow adverbs and, as such, around polar antonyms.

Regarding word-formation mechanisms serving as means of meaning intensification, we examine (i) structures in which prefixoids (e.g. mega-) are combined with speed adverbs (e.g. mega+kiiresti ‘mega fast’) and (ii) reduplication, where speed adverbs are partially or fully repeated two or more times and written as one word (e.g. kiiresti-kiiresti ‘quickly-quickly’).

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we begin with the definition of speed and then describe the theoretical background of the study, moving from polar antonyms to the lexicalisation of speed in vocabulary more generally. Section 3 specifies the procedure and principles of data collection and presents the results of the pre-study, which also serve as an overview of the data. In Section 4, we present the results for the hypothesis-testing account regarding the fastness-bias, and in Section 5, we discuss the findings from the perspective of linguistic and cognitive asymmetries, including antonymy, and outline future prospects.

2 Background

2.1 The notion of speed

speed can be defined as a “rate of movement” understood as “how fast something moves” and/or the “rate at which something moves or happens”.[1] In linguistic studies, speed is mostly understood as a rate (e.g. Slobin et al. 2014) but also as a temporal concept (Plungian and Rakhilina 2013) or as a concept of change (Koev 2017). If seen as a rate, speed falls under the category of manner (Cardini 2008); and if seen as a temporal concept, speed can be seen as duration (Plungian and Rakhilina 2013). In most approaches, however, speed is differentiated from duration and time (Givón 1970; Hallonsten Halling 2018), and this approach is also followed in the current study. Thus, the study reports on Estonian speed adverbs expressing rate (even if the adverbs may also have a duration reading in some contexts).

The differentiation between rate and duration in the conceptualisation of speed highlights another important facet of it – namely, it seems impossible to conceptualise speed without motion. Even though all kinds of processes can be characterised by speed, not only physical motion, we can argue that motion speed is the source domain for expressing diverse target domains, similar to the time is space metaphor. In other words, the conceptualisation of any dynamic event is grounded in the conceptualisation of motion event. As a result, whenever we talk about the expression of speed in language, the prototype is the expression of motion speed, with the extensions to other domains, such as events unfolding in time or actions performed over time. Without the motion component (i.e. spatial component), only duration remains, which is a purely temporal notion.

Similar arguments have also been put forward in other studies. For example, Lahlou (2023) shows that in Arabic, the term ‘speed’ is conceptualised through two related conceptual metaphors, namely speed of action is speed of motion and speed of progress is speed of motion to a destination, both grounded in the more general metaphor change is motion (see also Lakoff et al. 1991). The metaphor speed of action is speed of motion has also been noted in the study of music language by Wu and Liu (2024) and in the analysis of Cantonese speed-expressing slang by Wong (2020).

Finally, all speed adverbs in our data can, in principle, be used to describe physical motion, providing further rationale for not distinguishing motion speed from the speed of other processes unfolding over time. Therefore, when discussing speed in language, we understand speed as motion speed (i.e. rate), while acknowledging its extensions to other, non-physical and non-motion domains. For the same reason, we also provide an overview of speed in the context of motion event studies (see Section 2.3).

2.2 Polar antonyms

Polar antonyms are gradable antonyms that “denote relative values along a single dimension, like length or weight, prototypically measured in conventional units” (Cruse 2006: 129–130). The English adjectives fast and slow are examples of typical polar antonyms. As polar antonyms, speed adjectives (and adverbs) are subject to certain characteristics. First, they “are typically evaluatively neutral, and objectively descriptive” (Cruse 1986: 208). This means that events described by such words can be measured (e.g. as kilometres per hour). Second, one of the two antonyms is more basic than the other. That is, one end of the scale of polar antonyms is more dominant than the other end. The dominant end can also be taken as the unmarked category and the other end as the marked one (Al-Kajela 2018; Ingram et al. 2016). Cruse (1986: 208–209) describes this characteristic of polar antonyms in terms of impartialness: “Only one member of a pair yields a normal how-question /…/, and this question is impartial”. For instance, it would be more neutral to ask How fast is it? than How slow is it? In addition, “a single scale underlies a pair of polar antonyms” (Cruse 1986: 210), and this scale is for the dominant member of the word pair (e.g. fast). Thus, as Cruse (1986: 210) notes, it is more natural to say fastness than slowness as the underlying scale is driven by the concept of fast, not by slow. Al-Kajela (2018) further claims that in terms of the unmarked (i.e. dominant) and marked (i.e. non-dominant) category member of the antonym pair, “the former is more frequent and neutral than the latter” (Al-Kajela 2018: 115). Cross-linguistically, however, gradable antonyms vary in that even though some cross-linguistic regularities regarding impartialness can be detected, the committed behaviour of the lexical items is also very much context-dependent (Cruse 1992).

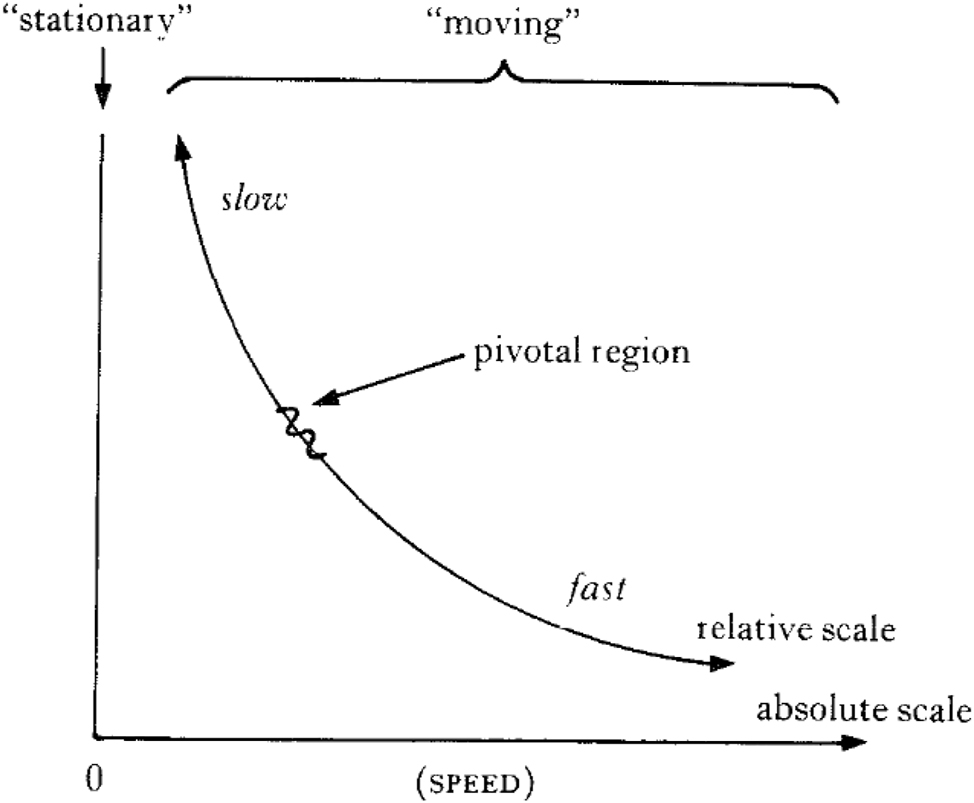

A more general inherent feature of (polar) antonyms is that they can simultaneously be presented on two scales: on “an absolute scale, which covers all possible values of the scaled property from zero to infinity, and relative scale, which is movable relative to the absolute scale” (Cruse 1986: 205). That is, the speed of an object can vary from 0 m/s (= standing) to infinity (faster than light). Even though speed can be measured, in language, and particularly so at the word level, speed can be best treated on a relative scale: fast refers to faster motion than slow. Cruse (1986: 205) illustrates the two scales with the following figure in which the pivotal region refers to the neutral centre of the scale (see Figure 1).

Speed as an illustration of polar antonyms. The figure is taken from Cruse (1986: 205).

This neutral centre, or pivotal region, can be captured as “some kind of implicit or explicit standard or norm /…/ against which judgements are made and in the light of which qualities are attributed” (Singleton 2016: 73). Often, however, there seem to be no lexical items that could be taken to convey the norm itself (Pajusalu 2009: 143). Even though there are very general items that could represent the pivotal region (e.g. moderately, normally), their semantics does not include the features of this specific domain. This applies also to speed in that there seem to be no lexical items conveying medium speed (apart from the general terms that do not incorporate speed features). Thus, it is an open question whether the pivotal region of the scale is realised in a specialised lexical inventory, or whether there is a gap in the scale between the items (e.g. between the items of fastness and slowness).

Polar antonyms are typically not discussed in the context of their whole semantic domain because other linguistic realisations of the same domain, and their relation to the clearest instance of an antonym pair, tend to lie behind the main scopes of the studies. Because antonyms can reflect the more general asymmetries in language and in cognition, we now turn to the studies that have addressed lexical means for speed – the focus of the current study – from a broader angle.

2.3 Asymmetries in the expression of speed

There are several ways in language to express speed. For instance, depending on the language, speed can be expressed by verbs (e.g. hurry), nouns (e.g. rush), adverbs (e.g. quickly) and adjectives (e.g. quick) (see also papers in Dixon and Aikhenvald 2004). In addition, speed can be conveyed by suprasegmental categories, such as speech rate, and even by phonemic iconicity (Zhao and Wu 2025). We can call lexemes that incorporate speed in their semantics as instances of speed lexicon. Speed adverbs – a specific class of speed lexicon and, simultaneously, a specific class of manner adverbs – are the focus of the current paper. However, speed adverbs are considerably less often addressed in the literature than speed adjectives, and far less frequently than (manner of) motion verbs that also lexicalise speed as a principal dimension. Thus, addressing speed, we start with motion verbs and then move to adverbs and adjectives as word classes that are closely linked in language as adverbs are often derived from adjectives (e.g. slow > slowly in English) or even share the same lexical form (e.g. fast as both an adverb and adjective in English).

As evidenced in studies of motion verbs, speed is highly pertinent to motion (Ikegami 1969; Malt et al. 2008; Slobin et al. 2014; Vulchanova and Martinez 2013). It is one of the core dimensions of manner (e.g. Cardini 2008; Kopecka 2010; Narasimhan 2003; Snell-Hornby 1983; Stosic 2019), introducing asymmetries in linguistic encoding (Ikegami 1969; Snell-Hornby 1983). For example, Ikegami (1969) suggests that there are more fast motion verbs than slow motion verbs in English, whereas slow motion verbs are often semantically more complex in that the slow motion is a consequence of laborious motion, as in the verb crawl. Similarly, Aurnague (2011, 2024), in his classification of semantic dimensions that license French verbs’ telicity reading in context, discusses speed in relation to fast verbs (e.g. ‘run’), and force in relation to slow verbs (e.g. ‘crawl’). Snell-Hornby (1983), in analysing German and English verbs, also treats fastness as a primary and slowness as a secondary dimension of motion verbs. At the same time, motion verbs, when rated for how fast or slow the motion they encode is form a continuum from the slowest to fastest verbs, as evidenced by studies on English (Zhao and Wu 2025) and Estonian (Taremaa 2017). Such rating studies do not seem to confirm the early observations of imbalanced sets of fast versus slow verbs, but both studies indicate that fast verbs receive more extreme ratings than slow verbs.

As for adjectives and adverbs, the seminal study of Dixon (1982; see also Dixon 2004a) links word classes with their characteristic semantic types and lists speed as one of the peripheral semantic types of adjectives. Peripheral means that adjectives of speed are not found in the lexicon of all languages, but rather only in those with medium- or large-sized adjective classes. Studies of diverse languages (see papers in Dixon and Aikhenvald 2004) confirm this suggestion by showing that even if speed is expressed by adjectives in some languages, there are languages in which instead of adjectives, speed is realised in verbs (Dixon 2004b) or adverbs (England 2004; Levy 2004). A recent study (Hallonsten Halling 2018) focusing on adverbs instead of adjectives further shows that for the word class of adverbs, speed can be taken as the core, not peripheral semantic type. It examines 60 typologically diverse languages, focusing on simple adverbs (in Hallonsten Halling’s approach, simple adverbs are mono-morphemic words). Of the languages that have simple adverbs (41 out of 60), all express speed with adverbs.

If speed adverbs or adjectives occur in a language, their lexicon can vary greatly, with some languages having only one item of speed per word class, whereas others have a numerous and diverse set of speed words. For instance, Hallonsten Halling (2018) shows that, based on her typological study of 60 languages, even though the majority (i.e. 41) of the study’s languages have simple speed adverbs, several of them have only one or two speed adverbs (it should be noted, however, that she only examined mono-morphemic speed adverbs). As another example, Nkami (spoken in Ghana) has only two speed adjectives, one for fast and one for slow speed (Asante 2021).

If a language has several items of speed adjectives/adverbs (which is typical, for instance, in European languages), a specific asymmetry may occur, as evidenced by the studies conducted in the domain of motion descriptions. That is, there is converging evidence for the asymmetry between fast and slow expressions in language, also labelled as the fast-over-slow asymmetry (Taremaa and Kopecka 2023a). As one realisation of this asymmetry, fast motion tends to be expressed more frequently and diversely than slow motion (Hallonsten Halling 2018; Plungian and Rakhilina 2013; Taremaa and Kopecka 2023a, 2023b). For instance, in Russian, there are over fifteen adjectives for fastness and only one main adjective for slowness (Plungian and Rakhilina 2013). Plungian and Rakhilina (2013) suggest the same holds true for other Slavic languages as well. In Estonian motion descriptions, fast motion is explicitly expressed by manner modifiers (realising in various morphosyntactic patterns) almost five times more frequently than slow motion (Taremaa and Kopecka 2023a). Also, it does not seem to be accidental that Schäfer (2023), in his study on ly-derivational adverbs of English, includes in his analysis 10 adjectives of fast motion (e.g. brisk, hasty) and only one adjective of slow motion (slow). Furthermore, as for processing in the sentential context, fast adverbs are read more quickly than slow adverbs in English (Stites et al. 2013), which is in accord with the finding that objects entailing faster motion tend to be named faster than those that imply slower motion (Ben-Haim et al. 2015). This suggests that fastness in general receives predominant processing over slowness, resulting in the asymmetries of adverbs (also in terms of antonyms).

2.4 Adverbs in Estonian

Estonian is a morphology-rich Finno-Ugric language with high manner saliency (Taremaa et al. 2024). One way of expressing manner (including speed as one dimension of it) is through adverbs. However, it should be noted that manner can be expressed not only by adverbs, and conversely, not all adverbs express manner. Adverbs in Estonian are defined as invariable words that, in the sentential context, function as adverbials, and, typically, express space, time, manner, state or quantity (Erelt et al. 1995: 23–26; Veismann and Erelt 2017: 417–421). Speed adverbs are subsumed under manner adverbs with no formal features to distinguish them from the rest of the (manner) adverbs. Instead, they share the same morphological characteristics with other adverbs.

Whereas a small number of Estonian adverbs have a simple morphological structure (e.g. tasa ‘quietly, slowly’) with no overt morphological marking, most Estonian adverbs are derived from adjectives or nouns by different derivational suffixes (e.g. aeglase+lt ‘slowly’ < aeglane ‘slow’ + -lt). The most common and most productive adverbial suffix is -lt; other suffixes with limited productivity are -sti, -misi, -ti/-di, and -mini (Kasik 2015: 383, 393). In addition, there are adverbs that are lexicalised case-inflected nominal words (e.g. hoo+ga ‘with a momentum’ as hoog ‘momentum’ + -ga as the comitative marker). As for complex, multi-stem adverbs, there are compounds consisting of fixed compounds, such as tasa+pisi [quietly+tiny.nom] ‘gradually, slowly’, and similes, such as välk+kiiresti [lightning.nom+fast] ‘lightning fast’. The other major class is reduplications (e.g. ruttu-ruttu ‘quickly-quickly’). All adverbs, regardless of their structure and semantics, can in principle be reduplicated in Estonian, and it is therefore a clear mechanism for meaning intensification (Erelt 2008; see also Dressler and Barbaresi 1994: 510–524). Furthermore, Erelt (2008: 271) suggests that “While väga ‘very’ and other augmentatives express a high degree of intensity, reduplication expresses ultimate intensity.”

Adverbs falling in the borderline of compounding and derivation are those composed of an intensifier as the first component and a speed adverb as the second component (e.g. hüper+kiiresti ‘hyper fast’) (see also Kiik 2021). Such intensifiers have sometimes been called prefixes (Hoeksema 2012), but more frequently prefix-like elements, semi-prefixes or prefixoids (Norde and Van Goethem 2018) or initial combining forms (ICFs; Prćić 2005). Depending on the take on the initial forms, the resulting complex words can be understood as compounds, prefixed words or something in between (see also Booij 2005).

For the purposes of the current study, the exact classification of such complex words is irrelevant as the main focus is on whether or not the meaning of a speed adverb is intensified by the initial component which, in essence, can attach to both slow and fast adverbs (cf., mega+kiiresti ‘mega fast’ and mega+aeglaselt ‘mega slowly’, üli+kiiresti ‘extra fast’ and üli+aeglaselt ‘extra slowly’, elu+kiiresti [life.nom+fast] ‘at full speed’ and elu+aeglaselt [life.nom+slowly] ‘very slowly’). Assessing intensification, we need to differentiate such word structures from fixed compounds and similes, as in the latter case the combinability of the first and second compound is much more restricted.

Simile compounds (e.g. välk+kiirelt [lightning.nom+fast] ‘lightning fast; very fast’, tigu+aeglaselt [snail.nom+slowly] ‘very slowly’) can also be seen as being based on the intensification mechanism but are not analysed here as such. This is because the combinability of the first component (e.g. välk ‘lightning’, tigu ‘snail’) with adverbs is much more restricted than for prefixoids. Not only can they not be added to the adverb expressing the opposite speed (e.g. *välk+aeglaselt ‘lightning slowly’, *tigu+kiirelt ‘snail fast’), but they cannot be easily combined with all adverbs of the same speed category either (cf. välk+kiirelt ‘lightning fast’ and ?välk+kähku ‘lightning’ + ‘quickly’). Prefixoids, on the other hand, can be attached to all kinds of speed adverbs (e.g. mega+kiirelt ‘mega quickly’, mega+kähku ‘mega quickly’, mega+aeglaselt ‘mega slowly’). Thus, for reasons of clarity, and to differentiate principally different word formation mechanisms, complex words with an intensifier as a prefixoid (e.g. mega- ‘mega’, hüper- ‘hyper’) are not termed as compounds but as ‘adverbs with prefixoids’ (for the sake of convenience, and very loosely, we will also use the term ‘prefixation’ to denote the mechanism of attaching prefixoids to adverbs). The term ‘compounds’ is used for fixed compounds (e.g. aega+mööda ‘slowly, gradually’) and similes (e.g. välk+kiirelt ‘lightning fast’).

3 Pre-study: establishing speed adverbs in Estonian

To examine the structure and any possible asymmetries of the speed adverb lexicon, it was first essential to establish as comprehensive a list of Estonian speed adverbs as possible, and then to annotate them for the variables that characterise the adverbs’ frequency, semantics and morphological structure.

3.1 Data collection

In the data collection process, two main difficulties had to be overcome: semantic and formal. The semantic challenge captures difficulties with the adverbs that could be positioned on the periphery of speed adverbs (or perhaps even be considered non-speed adverbs). For example, tasakesi in Estonian means ‘quietly’, but it may also imply slow motion without expressing any sound at all.

The formal challenge relates to difficulties in establishing the adverbs as a word class, as the boundaries of the adverb class in Estonian are fuzzy (Paulsen 2018). While in most cases, adverbs can be easily detected based on derivational suffixes or unchangeable word stems, certain case-inflected words are in the process of lexicalisation from case-inflected nouns to adverbs in Estonian. In addition, with regard to complex adverbs consisting of more than one word stem, it may be difficult to decide upon the bounds of an adverb (simple adverb vs. adverb with an intensifier as a separate word) due to the variation in whether the concept is written as one word or not. For example, super+kiiresti ‘superfast’ is almost as equally frequently written as two words (super kiiresti) or as one word (superkiiresti).[2]

To overcome the difficulties and to collect speed adverbs, we took a multimethodological approach and combined the dictionary lookup method, corpus analysis and a small-scaled rating task. The full procedure is described in Appendix A. Briefly summarised, we started with a small list of speed adverbs (N = 38) found in an earlier study by Taremaa and Kopecka (2023a) and then used these adverbs in dictionary and corpus searches to gather as many speed adverbs as possible (e.g. by establishing synonyms and compounds). The consulted dictionaries include the main monolingual dictionaries of Estonian, Dictionary of Synonyms (Õim 2007), The Dictionary of Estonian (Sõnaveeb 2019) and The Defining Dictionary of Estonian (EKSS; Langemets et al. 2009). The corpus that was consulted is the Estonian National Corpus 2021 (ENC 2021, size 2.4 billion words; Koppel and Kallas 2022). To reduce researcher bias, adverbs were also rated for their speed reading by four native speakers of Estonian, all trained in linguistics. When rating for speed, the task of the speakers was to evaluate whether an adverb encodes speed, with the possible responses ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘maybe’ and ‘unknown word’. When at least one speaker marked the adverb as expressing speed, it was included in the preliminary list of speed adverbs.

This resulted in 419 speed adverbs. The next step was to limit the set of adverbs to those that incorporate speed as a salient feature in their semantics. For this, we consulted two main dictionaries of Estonian which provide definitions for words: The Dictionary of Estonian (Sõnaveeb 2019) and The Defining Dictionary of Estonian (EKSS; Langemets et al. 2009). If an adverb was defined in at least one of the dictionaries through speed-related notions, it was included in the study. If it was not defined through speed or it was absent in the dictionaries, it was excluded. Regarding some adverbialised comitative or adessive forms that did not occur as separate entries, the meaning of the corresponding verb or noun was considered in establishing the adverbs semantics. If a reduplication or an adverb with a prefixoid was absent in the dictionary, the meaning definition of the second component was taken into account. Applying these criteria, 369 adverbs remained,[3] and this is the data the current study reports on.

As for the speed content of the adverbs, the resulting list contains both prototypical speed adverbs (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’, aeglaselt ‘slowly’), which we can refer to as primary speed adverbs, and also less prototypical ones where speed is just one (and possibly backgrounded) semantic feature, which we can refer to as secondary speed adverbs (e.g. tormiliselt ‘stormily, fast’, tasa ‘quietly, slowly’). In essence, the set of speed adverbs we have established and their further possible division into typical and less typical speed adverbs nicely illustrates the cline of speed the adverbs lexicalise. This cline is conceptual, corresponding to what Slobin et al. (2014: 702) have pointed out as follows: “Rather than representing discrete, compositional, Aristotelian categories, language use reveals conceptual continua”. However, differentiating between the primary and secondary speed adverbs and establishing the cuts on the speed cline for adverbs warrants a different type of study. Therefore, we focus on the opposition between fast and slow adverbs without further dividing them into additional semantic classes.

3.2 Data annotation

The adverbs in our data are annotated for the following variables (see Table 1). The main variables are Adverb, AdverbSpeed, AdverbComplexity and ComplexityType. The variable Adverb represents the individual adverbs in our list of speed adverbs (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’, üli+kiiresti ‘extra fast’). AdverbComplexity shows whether the adverb is a simple or complex one. A simple adverb is a one-stem adverb, i.e. an un-prefixed, non-compound and non-reduplicated adverb, where it is considered a simple adverb regardless of the presence of any possible derivational suffixes. For instance, non-derived adverbs such as ruttu ‘quickly’ and derived adverbs such as kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’ (< kiire + the derivational suffix -sti) are both analysed as simple adverbs in this study. A complex adverb, as captured by ComplexityType, is either a compound (e.g. välk+kiiresti ‘lightning fast’), an adverb with a prefixoid (e.g. üli+kiiresti ‘extra fast’) or a reduplicated word (e.g. ruttu-ruttu ‘quickly-quickly’). In other words, a complex adverb consists of multiple stems. For modelling purposes, additional variables PrefixedOrNot and ReduplicatedOrNot are included to assess complexity type in more detail.

Adverb annotation schema.

| Variable | Levels | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lexical material and morphological complexity of the adverbs | Adverb | aegamisi ‘slowly’, aegamööda ‘slowly, gradually’, aeglaselt-aeglaselt ‘slowly-slowly’, … | Individual adverbs |

| AdverbComplexity | simple, complex | Type of adverb in terms of one-stem (simple) or multiple-stem (complex) structure | |

| ComplexityType | compound, adverb with prefixoid, reduplication | Type of complex adverb in terms of word formation patterns | |

| PrefixedOrNot | yes, no | A binary variable showing whether the adverb is with a prefixoid or not | |

| ReduplicatedOrNot | yes, no | A binary variable showing whether the adverb is reduplicated or not | |

| FirstComp | aega-, aeglaselt-, elu-, üli-, … | Individual first components of complex adverbs | |

| LastComp | -mööda, -aeglaselt, … | Individual last components of complex adverbs | |

| DerivSuffix | -kesi, -kesti, -l, -lt, -misi, -sti, -ti/-di; -ga | Derivational suffix of derived adverbs | |

| Semantic dimensions of speed adverbs | AdverbSpeed | fast, slow | General speed content of the adverbs |

| Descriptiveness | yes, no | A binary variable showing whether the adverb sound structure mimics visible or auditory aspects of a process or not | |

| Token frequency | EstimAbsFreq | Numeric values (range 0 to 543,886) | Estimated absolute frequency of adverbs in the ENC 2021 |

| EstimRelFreq | Numeric values (range 0 to 184.65) | Frequency per million words in the ENC 2021 | |

| Log10freq | Numeric values (range 0 to 5.736) | Logarithmically transformed frequencies (log10). To avoid minus infinity log-values of zero frequencies, all raw frequencies were increased by 1 before log-transformation |

To address intensification mechanisms, the additional variables FirstComp and LastComp are coded to address which lexical information is used to intensify the meaning of fast versus slow adverbs, and how. FirstComp represents lexical items that are used as the first component (e.g. üli- ‘ekstra-’) of complex adverbs (e.g. üli+kiiresti ‘ekstra fast’). LastComp is the item used as the last component (e.g. -kiiresti ‘-fast’) of a complex adverb. In addition, for background knowledge, DerivSuffix is coded to assess if an adverb is a derivative, and if it is, which derivational suffixes it has.

As for semantics, AdverbSpeed divides the adverbs into fast (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’) and slow adverbs (e.g. aeglaselt ‘slowly’). To assess background information, Descriptiveness shows whether the adverb mimicks via sound symbolism auditory or visible aspects of a process (Kasik 2015: 77) – or not (e.g. vudinal ‘running (with small steps), pattering’, viuh ‘with a whizz, quickly’). This variable also includes onomatopoeic and momentaneous adverbs (e.g. viuh ‘with a whizz, quickly’, suts ‘with a pop, quickly’).

Frequency information of the adverbs is captured by estimated absolute and relative frequencies as EstimAbsFreq and EstimRelFreq (paired with log10-transformed frequencies, Log10freq), as attested in the ENC 2021 (accessed through SketchEngine; Kilgarriff et al. 2014). In calculating the frequencies, any possible orthographic deviations or misspellings of a word are not taken into account. For instance, rutturuttu and ruttu-ruttu ‘quickly-quickly’ are analysed as the same lemma, as are üli+kiiresti and yli+kiiresti ‘extra fast’. To address the potential homonymy of adverbs and adjectives when inflectional and derivational suffixes overlap (e.g. -lt in aeglase+lt, which can be an adverb meaning ‘slowly’, as in jooksi-n aeglase+lt [run-pst1sg slowly] ‘I ran slowly’, or an ablative-inflected adjective form, as in aeglase-lt auto-lt [aeglane-abl car-abl] ‘from a slow car’), the raw frequencies were adjusted based on an additional corpus analysis. With all such adverbs (N = 99), 200 sentences (if available) were randomly taken from the ENC 2021. Then, the sentences containing an adverb (and not an overlapping word form of some other word class) were counted and, based on this, an estimated frequency of each adverb was calculated. Thus, the frequencies of the adverbs in our data represent the frequencies of the adverb forms only.

Nevertheless, this frequency measure does not show how often an adverb is used to express speed-related information. This is a concern for polysemous words, which can be used in a broad range of semantic functions. For instance, tasa ‘quietly, slowly’ can mean slow motion, but it can also express the absence of noise or that something is done without anyone noticing it (EKSS; Langemets et al. 2009). Our frequency analysis fails to account for the uses of an adverb in which there are no associations with speed, and, therefore, the analysis can be taken merely as a rough estimation regarding the possible differences between the use of slow versus fast adverbs.

Data analysis and visualisation were performed in R (R Core Team 2023), using also packages sjPlot (Lüdecke 2021) and ggplot2 (Wickham et al. 2021). Data and code are available on the OSF (https://osf.io/dhpc7).

3.3 Results of the pre-study: data overview

This study is based on 369 adverbs conveying the semantic feature of speed. The majority of speed adverbs are semantically complex. For instance, the descriptive adverb vuhinal ‘swooshing, fast’ expresses high speed, sound and intensity; non-descriptive tulisi+jalu ‘hotfoot, fast’ expresses high speed and intensity, but in addition to that, it specifies body movements (‘on foot’; the second component of the word, -jalu, is a historical instructive case form of the word jalg ‘foot, leg’). This semantic complexity of speed adverbs is similar to manner complexity of motion verbs (for which speed is one of many dimensions motion verbs can express) (e.g. Cardini 2008), also noted in earlier studies of manner as a concept in general (e.g. Stosic 2020). In addition, a number of adverbs in our data are descriptive (N = 59), mostly onomatopoeic (e.g. robinal ‘rustling, fast’), and many of those are also momentaneous (N = 40; e.g. lipsti ‘with a plop, quickly’).

The morphological structure of speed adverbs in Estonian can be described from the perspective of (i) compounding, prefixation and reduplication (variable ComplexityType; i.e. adverbs analysed as complex adverbs in our study) and (ii) derivational suffixes (variable DerivSuffix). Recall that derivational adverbs can occur as either simple or complex adverbs in our analysis, meaning that the defining feature of complexity is the number of stems, not morphemes. Simple adverbs are either monomorphemic or consist of a stem and a derivational suffix, whereas complex adverbs have multiple stems (including prefixoids).

Of the 369 adverbs, 123 are simple adverbs (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’, aeglaselt ‘slowly’) and 246 complex adverbs (see Table 2). Complex adverbs are either reduplications (N = 40; e.g. ruttu-ruttu ‘quickly-quickly’, aeglaselt-aeglaselt ‘slowly-slowly’), adverbs modified by prefixoids (N = 140; e.g. mega+kiiresti ‘mega fast’, üli+aeglaselt ‘extra slowly’), or compound words (N = 66; e.g. välk+kiirelt [lightning.nom+fast] ‘lightning fast’, aega+mööda [time.prt+along] ‘slowly, gradually’). Compound words consist of fixed compounds (N = 43; e.g. tulisi+jalu [hot.adv+foot.adv] ‘hotfoot, fast’, aega+mööda [time.prt+along] ‘slowly, gradually’) and words which are based on the mechanism of comparison, i.e. similes (N = 23). In these simile compounds, the second component is a speed adverb and the first component expresses an entity with a characteristic motion speed (e.g. välk+kiirelt [lightning.nom+fast] ‘lightning fast’, tigu+aeglaselt [snail.nom+slowly] lit. ‘snail slowly’) or environment which dictates the possible motion speed (e.g. muda+aeglaselt [mud.nom+slowly] lit. ‘mud slowly’).

Simple versus complex adverbs and the distribution of adverbs across morphological make-up in terms of compounding, prefixation and reduplication.

| Adverb type | Distribution among the 369 speed adverbs |

|---|---|

| Simple adverbs | 123 (32.7 %) |

| Complex adverbs, including | 246 (67.3 %) |

| … fixed compounds | … 43 (17.5 % of the complex adverbs) |

| … simile compounds | … 23 (9.3 % of the complex adverbs) |

| … adverbs with prefixoids | … 140 (56.9 % of the complex adverbs) |

| … reduplications | … 40 (16.3 % of the complex adverbs) |

The most typical and frequent speed adverbs (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’, aeglaselt ‘slowly’) are also the ones that are often combined with a diverse set of prefixoids (e.g. üli+kiiresti ‘extra fast’, super+kiiresti ‘superfast’, elu+kiiresti lit. ‘life fast’) and are frequently reduplicated (e.g. kiiresti-kiiresti ‘quickly-quickly’, aeglaselt-aeglaselt ‘slowly-slowly’).

Of the total of 369 adverbs (both simple and complex), 108 are non-derived (including fully lexicalised partitive, inessive and instructive case forms) and 261 derivational adverbs. Of the 123 simple adverbs, 28 (22.8 %) are non-derived and 95 (77.2 %) are derived adverbs. Of the 246 complex adverbs, 80 (32.5 %) are non-derived and 166 (67.5 %) are derived adverbs. Seven unique derivational suffixes occur (exceptionally, we include the comitative case ending -ga here as comitative-inflected nouns are in the process of lexicalising into adverbs; e.g. hoo+ga ‘with a momentum’). The most frequent by far are lt-adverbs (N = 144; kiire+lt ‘fast, quickly’), followed by sti-adverbs (N = 58; e.g. kiire+sti ‘fast, quickly’).[4]

4 Main study: testing the fast-over-slow asymmetry

Having established the inventory of speed adverbs in Estonian, we now turn to testing the suggested fast-over-slow asymmetry. The hypotheses were that fast adverbs are more numerous and more frequently used than slow adverbs (Hypothesis 1) and that the meaning of fast adverbs is more likely to be intensified than that of slow adverbs (Hypothesis 2).

4.1 Hypothesis 1: type and token frequencies of fast versus slow adverbs

The hypothesis regarding the number of unique speed adverbs (i.e. type frequencies) is clearly confirmed, as can be seen in Figure 2. The total list of 369 adverbs has 105 (85.4 %) fast versus 18 (14.6 %) slow simple adverbs, and 193 (78.5 %) fast versus 53 (21.5 %) slow complex adverbs. In total, there are 298 (81 %) fast versus 71 (19 %) slow adverbs.

The distribution of fast and slow adverbs across complexity types. Simple adverbs consist of one stem (and a derivational suffix); complex adverbs consist of multiple stems (including prefixoids).

The ten most frequent speed adverbs are presented in Table 3. Two fast adverbs, kiiresti and kiirelt ‘fast, quickly’, are the most frequent. They are followed by the slow adverb vaikselt ‘quietly, slowly’, which can be considered a secondary speed adverb. This is because it can denote only quietness (without encoding speed) or describe slow motion (without encoding quietness). The neutral primary slow adverb, aeglaselt ‘slowly’, ranks fifth according to their frequencies.

The ten most frequent adverbs in the data.

| Adverb | Adverb speed | EstimAbsFreq | EstimRelFreq (per million words) | Log10Freq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’ | FAST | 543,886 | 184.65 | 5.74 |

| kiirelt ‘fast, quickly’ | FAST | 206,239 | 70.02 | 5.31 |

| vaikselt ‘quietly, slowly’ | SLOW | 180,892 | 61.41 | 5.26 |

| ruttu ‘quickly’ | FAST | 88,742 | 30.13 | 4.95 |

| aeglaselt ‘slowly’ | SLOW | 69,477 | 23.59 | 4.84 |

| tasa+pisi ‘gradually, slowly’ | SLOW | 65,205 | 22.14 | 4.81 |

| tasa ‘quietly, slowly’ | SLOW | 29,631 | 10.06 | 4.47 |

| kähku ‘swiftly, fast’ | FAST | 24,577 | 8.34 | 4.39 |

| jõudsalt ‘thrivingly, fast’ | FAST | 22,914 | 7.78 | 4.36 |

| hoogsalt ‘briskly, fast’ | FAST | 20,037 | 6.80 | 4.30 |

Regarding token frequencies (as attested in the ENC 2021), the total sum of all adverbs’ frequencies across fast versus slow adverbs is also different, but here fast outperforms slow only across simple adverbs (1,015,137 fast vs. 301,527 slow adverbs), whereas the opposite occurs for complex adverbs (28,233 fast vs. 91,054 slow adverbs) (see Figure 3).

Summed estimated absolute frequencies (token frequencies) of speed adverbs across complexity types. Simple adverbs consist of one stem (and a derivational suffix); complex adverbs consist of multiple stems (including prefixoids).

The summed frequencies depend on the number of lexemes available. Therefore, by having more fast adverbs in the language, it is not surprising that the summed frequencies of fast adverbs are considerably higher than that of slow adverbs. Figure 4 indicates that there are high-frequency adverbs both in slow and fast groups, but the numerosity differs (extensively more fast than slow adverbs). In addition, simple adverbs (in blue) seem to be more frequent than complex adverbs (in yellow). This is also reflected in the top 10 adverbs in terms of frequencies, as shown in Table 3.

Frequency distribution of fast and slow adverbs as simple (in blue) or complex adverbs (in yellow) across complexity types. Simple adverbs consist of one stem (and a derivational suffix); complex adverbs consist of multiple stems (including prefixoids).

Because the data is highly unbalanced, with fast adverbs comprising the majority of the data (which is a significant result in itself), modelling the entire dataset would not be reliable. Therefore, and to capture the most important speed adverbs in the language, we fitted a regression model to a subset of data consisting of the 60 most frequent speed adverbs (30 fast and 30 slow; see Appendix B). Only simple adverbs (N = 42) and compounds (N = 18) were included to ensure data consistency. We used a binary logistic regression model to analyse the relationship between adverb semantic type (AdverbSpeed; fast vs. slow) and the adverb frequency (Log10freq; as attested in the ENC 2021), controlling for adverb complexity (AdverbComplexity). The model was statistically significant (χ 2(2) = 15.37, p < 0.001) and moderate (C = 0.75);[5] see also Appendix C. Consistent with the hypothesis, there is a reliable effect of adverb frequency on adverb speed (β = 0.96, SE = 0.4, z = 2.7, p = 0.008), with fast adverbs having a higher likelihood of being of higher frequency than slow adverbs (see Figure 5). Adverb complexity was marginally significant (β = –1.08, SE = 0.7, z = –1.6, p = 0.1), indicating that complex adverbs are more likely to occur among the most frequent slow adverbs than among fast adverbs. This shows the limited number of simple slow adverbs that are available for the speakers as compared to fast adverbs.

Log10-frequencies of slow and fast adverbs (left panel; horizontal lines indicate median, square symbols indicate mean values) and predicted probability of fast adverbs as a function of log10-frequencies (right panel). The data subset includes the 30 most frequent and typical fast and 30 slow adverbs.

These results suggest that even though there are some slow adverbs that are particularly frequent, similarly to the most frequent fast adverbs, fastness is predominant in Estonian and can be expressed by a variety of adverbs. Slowness is much less frequently expressed and by fewer lexemes. Thus, the fast-over-slow hypothesis regarding type and token frequencies is clearly confirmed.

4.2 Hypothesis 2: meaning intensification of fast versus slow adverbs

We hypothesised that because fastness is more intense than slowness, the meaning of fast adverbs is more likely to be intensified than that of slow adverbs (Hypothesis 2). As a proxy for measuring meaning intensification, we use intensifying prefixoids and reduplications and count the occurrences of an adverb being (i) preceded by a prefixoid or (ii) reduplicated.

The proportions are presented in Figure 6. Contrary to our expectations, there are no significant differences in proportions between fast and slow adverbs in terms of being preceded by a prefixoid. The number of fast adverbs with prefixoids is much larger than that of slow adverbs (115 vs. 25), but this is due to the large number of fast adverbs. The proportion of adverbs with prefixoids is close to 40 % for both fast and slow adverbs. As for reduplication, even smaller differences occur.

The proportion of adverbs with prefixoids (left panel) and reduplicated adverbs (right panel) across fast and slow adverbs.

To confirm these observations statistically, we fitted a binary logistic regression with adverb speed (fast vs. slow) as the dependent variable and the presence of a prefixoid and reduplication as predictors, controlling for adverb frequency (log10 frequency). The model was not statistically significant (χ 2(3) = 1.86, p = 0.6); see also Appendix C. Thus, there are no significant effects of meaning intensification through adding prefixoids or through reduplication.

Finally, not all adverbs lend themselves equally often to prefixation. In our data, only roughly 18 % of fast and 19 % of slow simple/compound adverbs occur with prefixoids (see Table 4). The choice of prefixoids is more varied across slow adverbs than fast adverbs, at least considering the ratio between the number of unique adverbs and the number of unique prefixoids (1.9 for fast and 3.6 for slow adverbs), even though the total number of unique prefixoids is larger for fast adverbs compared to slow adverbs (40 vs. 18 unique prefixoids).

Combinability between unique prefixoids and unique adverbs.

| Adverb speed | Unique prefixoids (N = 41)a | Unique adverbs as last components (N = 26) preceded by a prefixoid | Ratio between unique prefixoids and unique adverbs being preceded by prefixoids |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAST | 40 | 21 out of 115 (18 %) | 40/21 = 1.9 |

| SLOW | 18 | 5 out of 25 (19 %) | 18/5 = 3.6 |

-

aNote that because some of the prefixoids overlap, the total number of unique prefixoids is smaller than when summing up unique prefixoids of fast and slow adverbs.

These results indicate that contrary to our expectation, speed adverbs are not sensitive to intensification in terms of prefixation and reduplication. In other words, Hypothesis 2 is not confirmed. The proportion of adverbs being used with prefixoids is similar across fast and slow adverbs, but the array of possible prefixoids is broader for fast than for slow adverbs because simple fast adverbs are more numerous than slow adverbs. Slow adverbs (if preceded by a prefixoid), in turn, are more likely to co-occur with different prefixoids because on average, each slow adverb occurs with 3.6 unique prefixoids, whereas every fast adverb occurs with 1.9 unique prefixoids. However, it should be noted that these results depend on, firstly, what is considered a speed adverb, and, secondly, how similes and adverbs with prefixoids are differentiated from one another. We shall discuss this more thoroughly in the next section.

5 Discussion

The aim of this study was to address the linguistic asymmetry of polar antonyms, extending beyond individual word pairs to encompass the entire semantic domain of a particular word class. Thus, we examined the speed domain and adverbs expressing it in Estonian by contrasting fast adverbs (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’) with slow adverbs (e.g. aeglaselt ‘slowly’). Using multiple data collection sources, methods and criteria, we established 369 adverbs that – according to dictionary definitions – can be attributed to a speed reading in Estonian: 123 simple and 246 complex adverbs. Simple adverbs are understood as one-stem adverbs, including those with derivational suffixes (e.g. kiire+sti ‘fast, quickly’). Complex adverbs are understood as multi-stem adverbs, including also adverbs with prefixoids (e.g. mega+ruttu ‘mega quickly’) in addition to compounds (e.g. aega+mööda ‘slowly, gradually’) and reduplications (e.g. ruttu-ruttu ‘quickly-quickly’).

Testing the possible inherent asymmetry in speed adverbs – the fast-over-slow bias –, we found clear evidence for it in terms of the imbalanced number of items we have for fast and slow speed. Specifically, the number of unique adverbs for fastness is approximately four times larger than the number of unique items for slowness (regarding simple adverbs, the ratio is even larger). Having more adverbs for fastness results in a proportionally high summed frequency for adverbs. To verify that fast adverbs are indeed used more frequently than slow adverbs independent of the high number of fast adverbs, we modelled the data by including only the 30 most frequent fast and most frequent slow adverbs. This also confirmed the positive link between fast adverbs and high frequency. The adverbs kiiresti and kiirelt, both translated as ‘fast, quickly’, are the most frequent fast adverbs, and the most frequent ones in general. Even though some slow adverbs (e.g. vaikselt ‘quietly, slowly’ and aeglaselt ‘slowly’) are particularly frequent too, the number of such high-frequency slow adverbs is smaller than that of fast adverbs. Thus, taken together, people express fastness considerably more often than slowness.

These results suggest that the asymmetry between scalar polar antonyms, such as fast–slow, large–small, and the like, is rooted in a more fundamental asymmetry within the lexicon and language use, which, in turn, is likely to be related to cognitive asymmetries. It is conceivable that looking at antonyms as word pairs, one of them is more marked than the other, as has been proven in several studies with diverse antonym pairs (Kostić 2015; Lehrer 1985; Nithithanawiwat 2023). However, the items within the two poles vary significantly in terms of markedness. That is, fast adverbs have neutral adverbs (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’) and items that are clearly more loaded one way or another (e.g. ummis+jalu ‘running, headlong, fast’). Similarly, slow adverbs have neutral adverbs (e.g. aeglaselt ‘slowly’) and items that can be taken as marked (e.g. pikkamööda ‘slowly, gradually’). When comparing less typical items taken from the opposite poles (e.g. ummisjalu vs. pikkamööda), one would find it impossible to decide which one of them is the marked and which one is the neutral one. This, in turn, relates to semantic complexity in that conceptually complex items do not form easily antonym pairs (Paradis 2011; see also Kotzor 2021). Furthermore, one would find it challenging to find an antonym for all the individual fast adverbs and all the individual slow adverbs as it is likely to depend on the degree of forming conventionalised antonyms (see also Paradis et al. 2009). Thus, it is essential to bridge the antonym studies to larger lexicon studies (also from the cross-linguistic perspective) to more fully capture the realisation of cognitive asymmetries in language.

Why one end of a scale is more dominant in language is likely to have cognitive underpinnings. Regarding speed, high speed is more prominent for humans than low speed. For instance, neuroimaging studies have shown that not only are fast and slow motion processed partially unrelatedly in the brain (Yan et al. 2023) but also that fast motion results in more enhanced neural responses (Wang et al. 2003) and faster reaction than slow motion (Hülsdünker et al. 2019). This is presumably because fast motion is perceived as more important and possibly having more consequences than slow motion (Grasso et al. 2018). The predominance of fastness has also been observed in psycholinguistic experiments. For instance, reading times for fast adverbs are shorter than those for slow adverbs in English (Stites et al. 2013), and objects associated with faster motion tend to be named faster than those associated with slower motion (Ben-Haim et al. 2015). There is also some evidence that notions relating to fastness can be perceived as more positive than those of low speed (Paradis et al. 2012). This, in turn, relates the findings for the speed lexicon to the Pollyanna principle. According to the Pollyanna principle, positive terms are more profound than negative ones (Boucher and Osgood 1969). Therefore, it is not surprising that language reflects the cognitive bias towards fastness by also having a larger lexical inventory for fast motion than for slow motion.

Nevertheless, and contrary to our expectations, the meaning of fast adverbs was not more likely to be intensified than the meaning of slow adverbs in terms of prefixoids and reduplication. Needless to say, these results heavily depend on the selection choices (what counts as a speed adverb?) and classification criteria (how compounds are differentiated from adverbs with prefixoids?). In this regard, the results are somewhat unstable, as different inclusion and analysis criteria could have resulted in a somewhat different set of speed adverbs. For instance, we excluded instances that had a meaning intensifier (e.g. nii ‘so’, väga ‘very’) but were written as two words more frequently than as one word (e.g. niikiiresti as nii kiiresti ‘so fast’, vägakiiresti as väga kiiresti ‘so fast’, ilmatukiiresti as ilmatu kiiresti ‘so very fast’). Including such uses would have changed the results, with fast adverbs being prefixed more frequently than slow adverbs. Thus, future studies could also assess other meaning intensification mechanisms besides word-formation ones, including prefixoids written as separate words (mega kiiresti ‘mega fast’) and other intensifying adverbs that can precede an adverb (e.g. väga ‘very’, nii ‘so’), occasionally also written as one word.

One aspect that the current study did not delve into is the semantic complexity and salience of the speed dimension in adverb semantics, as this would require a different type of study. However, it should be noted that the set of speed adverbs we have established is a heterogeneous group of words in terms of their semantics, and they clearly vary in terms of the foregrounded speed content. As such, they range from more typical to less typical speed adverbs. Typical speed adverbs express speed as a salient dimension (e.g. kiiresti ‘fast, quickly’, aeglaselt ‘slowly’), whereas adverbs falling on the periphery of the speed domain, express speed as a backgrounded feature within their complex semantics (e.g. tormiliselt ‘stormily, fast’, vaikselt ‘quietly, slowly’). An observation not discussed in this study, but left for future research, is that slow adverbs may have a more complex semantic makeup, with speed being just one of several dimensions, where speed itself can be backgrounded. This, in turn, can be linked to findings of motion verbs where it has emerged that, frequently, high speed is lexicalised in motion verbs as a primary dimension, whereas low speed is lexicalised as a secondary, concomitant dimension (Ikegami 1969; Snell-Hornby 1983; see also Aurnague 2024 for the distinction between high speed and force dimensions in verbs, in which force implies slow speed). Future studies could assess the cognitive structure of speed adverbs in speakers’ language knowledge by using experimental and corpus linguistic computational methods. A corpus study of speed adverbs, examining their usage context and actual realisation as speed, rather than non-speed adverbs (in the case of secondary speed adverbs), would also be necessary.

The current study highlights the importance of focusing on individual core dimensions of manner such as speed and examining less-investigated word classes such as adverbs. The study showed that a language can exhibit a rich and vibrant inventory of speed lexemes that can be used flexibly to convey diverse semantic dimensions alongside speed and that can easily obey various word-formation mechanisms. This finding promotes adverbs as a valuable study object in linguistics in line with Hallonsten Halling (2018) and Duplâtre and Modicom (2022).

Regarding Estonian data, it seems to be the case that word-formation flexibility (in terms of forming lexemes by derivational suffixes and by compounding and adding intensifying prefixoids to the adverbs) is a prerequisite for the richness and diversity of speed adverbs as a subdomain of manner adverbs. In fact, because reduplication and intensifying through prefixoids are both productive mechanisms in Estonian, the number of possible complex speed adverbs exceeds the number of instances found in this study using dictionary and corpus methods. Another aspect that contributes to the diversity is the high degree to which Estonian relies on iconic vocabulary, including onomatopoeic words (on manner saliency and mimetics, see also Akita and Matsumoto 2020). As such, the study adds to the growing body of research on how manner, including speed, can be expressed in language (for manner in motion events, see, for instance, Goschler and Stefanowitsch 2013; Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2017; Matsumoto and Kawachi 2020; Sarda and Fagard 2022; Slobin 1996, 2004; Talmy 1985, 2000b; for studies that go beyond motion events, see, for instance, Akita 2017; Eckardt 1998; Gehrke and Castroviejo 2015; Hallonsten Halling 2018; Koev 2017; Paulsen 2018; Stosic 2020). The study emphasises the necessity to investigate not only manner as a general category, but also to delve into manner subdimensions and focus on specific linguistic means that are specialised to convey these subdimensions.

6 Conclusions

Embarking on the idea that linguistic asymmetry of polar antonyms reflects the asymmetry of the whole semantic domain the antonyms represent, the study addressed the expression of speed by adverbs. Thus, the inventory and internal structure of speed adverbs, as a subclass of manner adverbs, were examined in Estonian. The multimethodological approach resulted in establishing as many as 424 speed adverbs, 369 of which were defined as expressing speed in the monolingual dictionaries. The overall large number of unique speed adverbs can be attributed to the flexibility of word-formation mechanisms – compounding, derivation, reduplication and combining adverbs with prefixoids – available for the productive use of the speakers of the language. Examining the suggested fast-over-slow asymmetry, it was confirmed that the lexicon of speed adverbs is heavily biased towards fast adverbs, which were far more numerous and frequent than slow adverbs, even though the two sets of adverbs were not significantly different in terms of meaning intensification patterns through word-formation mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Len Toots for their great help in data collection and annotation. The study was supported by the Estonian Research Council grant PSG929, “Speed at the Crossroads of Language, Perception and Action”.

-

Data availability: The data and R code can be accessed on OSF: https://osf.io/dhpc7.

Appendix A: Data collection procedure

Appendix B: The 30 most frequent fast and most frequent slow adverbs included in the binary logistic regression modelling

| No | Adverb | Translation | Adverb speed | Adverb complexity | EstimAbs Freq | EstimRel Freq | Log10 Freq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | kiiresti | fast, quickly | FAST | simple | 543,886 | 184.65 | 5.74 |

| 2 | kiirelt | fast, quickly | FAST | simple | 206,239 | 70.02 | 5.31 |

| 3 | ruttu | quickly, speedily | FAST | simple | 88,742 | 30.13 | 4.95 |

| 4 | kähku | quickly, fast | FAST | simple | 24,577 | 8.34 | 4.39 |

| 5 | jõudsalt | thrivingly, fast | FAST | simple | 22,914 | 7.78 | 4.36 |

| 6 | hoogsalt | briskly | FAST | simple | 20,037 | 6.8 | 4.30 |

| 7 | kiiruga | hastily, hurriedly | FAST | simple | 15,030 | 5.1 | 4.18 |

| 8 | suts | with a pop, quickly | FAST | simple | 6,580 | 2.23 | 3.82 |

| 9 | hooga | with a momentum | FAST | simple | 6,570 | 2.23 | 3.82 |

| 10 | kärmelt | swiftly | FAST | simple | 6,027 | 2.05 | 3.78 |

| 11 | ajuga | lit. with brain; fast | FAST | simple | 5,668 | 1.92 | 3.75 |

| 12 | reipalt | vivaciously, fast | FAST | simple | 4,271 | 1.45 | 3.63 |

| 13 | naksti | click, quickly | FAST | simple | 3,850 | 1.31 | 3.59 |

| 14 | mühinal | roaring, fast | FAST | simple | 3,732 | 1.27 | 3.57 |

| 15 | uljalt | boldly, fast | FAST | simple | 3,576 | 1.21 | 3.55 |

| 16 | ülepeakaela | headlong, fast | FAST | complex [fixed compound] | 3,188 | 1.08 | 3.50 |

| 17 | jooksuga | running, hurriedly | FAST | simple | 2,795 | 0.95 | 3.45 |

| 18 | tormiliselt | stormily, fast | FAST | simple | 2,603 | 0.88 | 3.42 |

| 19 | tempokalt | fast | FAST | simple | 2,593 | 0.88 | 3.41 |

| 20 | lennult | on the fly, fast | FAST | simple | 2,543 | 0.86 | 3.41 |

| 21 | niuhti | with a whizz, quickly | FAST | simple | 2,400 | 0.81 | 3.38 |

| 22 | ludinal | smoothly, fast | FAST | simple | 2,280 | 0.77 | 3.36 |

| 23 | ummisjalu | in a blind rush, fast | FAST | complex [fixed compound] | 2,249 | 0.76 | 3.35 |

| 24 | jõudsasti | thrivingly, fast | FAST | simple | 2,204 | 0.75 | 3.34 |

| 25 | nobedalt | swiftly | FAST | simple | 2,174 | 0.74 | 3.34 |

| 26 | jalamaid | immediately, fast | FAST | complex [fixed compound] | 2,021 | 0.69 | 3.31 |

| 27 | hopsti | with a hop, quickly | FAST | simple | 2,005 | 0.68 | 3.30 |

| 28 | joonelt | straight, fast | FAST | simple | 1,858 | 0.63 | 3.27 |

| 29 | välkkiirelt | lightning fast | FAST | complex [simile compound] | 1,651 | 0.56 | 3.22 |

| 30 | kibekähku | lit. bitterly; quickly | FAST | complex [fixed compound] | 1,622 | 0.55 | 3.21 |

| 31 | vaikselt | quietly, slowly | SLOW | simple | 180,892 | 61.41 | 5.26 |

| 32 | aeglaselt | slowly | SLOW | simple | 69,477 | 23.59 | 4.84 |

| 33 | tasapisi | gradually, slowly | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 65,205 | 22.14 | 4.81 |

| 34 | tasa | quietly, slowly | SLOW | simple | 29,631 | 10.06 | 4.47 |

| 35 | tasakesi | quietly, slowly | SLOW | simple | 8,167 | 2.77 | 3.91 |

| 36 | aegamööda | slowly, gradually | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 7,633 | 2.59 | 3.88 |

| 37 | aegamisi | slowly | SLOW | simple | 4,966 | 1.69 | 3.70 |

| 38 | pikkamööda | slowly, gradually | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 4,595 | 1.56 | 3.66 |

| 39 | tasahilju | quietly, slowly | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 4,342 | 1.47 | 3.64 |

| 40 | aegluubis | in slow motion | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 3,415 | 1.16 | 3.53 |

| 41 | pikkamisi | slowly, gradually | SLOW | simple | 2,807 | 0.95 | 3.45 |

| 42 | laisalt | lazily, slowly | SLOW | simple | 2,768 | 0.94 | 3.44 |

| 43 | pisitasa | gradually, slowly | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 2,589 | 0.88 | 3.41 |

| 44 | loiult | sluggishly, slowly | SLOW | simple | 1,432 | 0.49 | 3.16 |

| 45 | aegapidi | slowly, gradually | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 897 | 0.3 | 2.95 |

| 46 | tasahaaval | gradually, slowly | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 867 | 0.29 | 2.94 |

| 47 | tasakesti | quietly, slowly | SLOW | simple | 411 | 0.14 | 2.61 |

| 48 | pikaldaselt | slowly, languidly | SLOW | simple | 348 | 0.12 | 2.54 |

| 49 | natukesehaaval | gradually, slowly | SLOW | complex | 207 | 0.07 | 2.32 |

| 50 | hiljukesi | quietly, slowly | SLOW | simple | 196 | 0.07 | 2.29 |

| 51 | hilju | quietly, slowly | SLOW | simple | 195 | 0.07 | 2.29 |

| 52 | venivalt | lit. stretchingly; slowly | SLOW | simple | 147 | 0.05 | 2.17 |

| 53 | tasahiljukesi | quietly, slowly | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 118 | 0.04 | 2.08 |

| 54 | härgamisi | laboriously, slowly | SLOW | simple | 52 | 0.02 | 1.72 |

| 55 | venitamisi | lit. stretchingly; slowly | SLOW | simple | 27 | 0.01 | 1.45 |

| 56 | tiguaeglaselt | lit. snail slowly | SLOW | complex [simile compound] | 16 | 0.01 | 1.23 |

| 57 | ruttamatult | without hurry | SLOW | simple | 7 | >0.01 | 0.90 |

| 58 | pikaliselt | slowly, languidly | SLOW | simple | 4 | >0.01 | 0.70 |

| 59 | mudaaeglaselt | lit. mud slowly | SLOW | complex [simile compound] | 2 | >0.01 | 0.48 |

| 60 | tasapikka | gradually, slowly | SLOW | complex [fixed compound] | 1 | >0.01 | 0.30 |

Appendix C: Model outputs in predicting adverb speed using binary logistic regression analysis

| Predictors | Adverb speed | Adverb speed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | t | p | Est. | SE | t | p | |

| (Intercept) | 17.68 | 22.33 | 2.27 | 0.023 | 0.32 | 0.15 | −2.45 | 0.014 |

| Logl0freq | 0.38 | 0.14 | −2.67 | 0.008 | 1.12 | 0.14 | 0.94 | 0.348 |

| Adverb complexity [complex] | 2.96 | 1.95 | 1.65 | 0.100 | ||||

| Prefixed or not [no] | 0.92 | 0.31 | −0.24 | 0.812 | ||||

| Reduplicated or not [no] | 0.62 | 0.27 | −1.09 | 0.275 | ||||

| Observations | 60 | 369 | ||||||

| R 2 Tjur | 0.233 | 0.005 | ||||||

-

Values in bold indicate statistically significant results (p<0.05).

References

Akita, Kimi. 2017. The typology of manner expressions. In Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano (ed.), Motion and space across languages: Theory and applications (Human Cognitive Processing 59), 39–60. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Suche in Google Scholar

Akita, Kimi & Yo Matsumoto. 2020. A fine-grained analysis of manner salience: Experimental evidence from Japanese and English. In Yo Matsumoto & Kazuhiro Kawachi (eds.), Broader perspectives on motion event descriptions (Human Cognitive Processing 69), 143–180. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/hcp.69.05akiSuche in Google Scholar

Al-Kajela, Ala. 2018. The syncategorematic nature of Neo-Aramaic and English antonyms. Linguistic Discovery 16(2). 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1349/PS1.1537-0852.A.477.Suche in Google Scholar

Asante, Rogers Krobea. 2021. A survey of property encoding expressions in Nkami. The Journal of West African Languages 48(1).Suche in Google Scholar

Aurnague, Michel. 2011. How motion verbs are spatial: The spatial foundations of intransitive motion verbs in French. Lingvisticae Investigationes 34(1). 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1075/li.34.1.01aur.Suche in Google Scholar

Aurnague, Michel. 2024. Telic motion constructions in French and the notion of tendentiality. Lingua 311. 103791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2024.103791.Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Haim, Moshe Shay, Eran Chajut, Ran R. Hassin & Daniel Algom. 2015. Speeded naming or naming speed? The automatic effect of object speed on performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 144(2). 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038569.Suche in Google Scholar

Booij, Geert. 2005. Compounding and derivation: Evidence for construction morphology. In Wolfgang U. Dressler, Dieter Kastovsky, Oskar E. Pfeiffer & Franz Rainer (eds.), Current issues in linguistic theory, vol. 264, 109–132. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Suche in Google Scholar

Boucher, Jerry & Charles E. Osgood. 1969. The pollyanna hypothesis. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 8(1). 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(69)80002-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Cardini, Filippo-Enrico. 2008. Manner of motion saliency: An inquiry into Italian. Cognitive Linguistics 19(4). 533–569. https://doi.org/10.1515/COGL.2008.021.Suche in Google Scholar

Cruse, D. Alan. 1986. Lexical semantics (Cambridge textbooks in linguistics). Cambridge/New York/Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Cruse, D. Alan. 1992. Antonymy revisited: Some thoughts on the relationship between words and concepts. In Adrienne Lehrer & Eva Feder Kittay (eds.), Frames, fields, and contrasts: New essays in semantic and lexical organization, 289–306. New York/London: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Cruse, Alan. 2006. A glossary of semantics and pragmatics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748626892Suche in Google Scholar

Dixon, R. M. W. 1982. Where have all the adjectives gone? And other essays in semantics and syntax (Janua Linguarum. Series maior 107). Berlin/New York/Amsterdam: Mouton Publisher.10.1515/9783110822939Suche in Google Scholar

Dixon, R. M. W. 2004a. Adjective classes in typological perspective. In R. M. W. Dixon & Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (eds.), Adjective classes: A cross-linguistic typology (Explorations in Linguistic Typology), 1–49. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199270934.003.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Dixon, R. M. W. 2004b. The small adjective class in Jarawara. In R. M. W. Dixon & Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (eds.), Adjective classes: A cross-linguistic typology (Explorations in Linguistic Typology), 177–198. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199270934.003.0007Suche in Google Scholar

Dixon, R. M. W. & Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (eds.). 2004. Adjective classes: A cross-linguistic typology (Explorations in Linguistic Typology). Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199270934.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Dressler, Wolfgang U. & Lavinia M. Barbaresi. 1994. Morphopragmatics: Diminutives and intensifiers in Italian, German, and other languages (Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs 76). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110877052Suche in Google Scholar

Duplâtre, Olivier & Pierre-Yves Modicom (eds.). 2022. Adverbs and adverbials: Categorial issues (Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs 371). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110767971Suche in Google Scholar

Eckardt, Regine. 1998. Adverbs, events, and other things: Issues in the semantics of manner adverbs. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.10.1515/9783110913781Suche in Google Scholar

England, Nora C. 2004. Adjectives in mam. In R. M. W. Dixon & Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (eds.), Adjective classes: A cross-linguistic typology (Explorations in Linguistic Typology), 125–146. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199270934.003.0005Suche in Google Scholar

Erelt, M. 2008. Intensifying reduplication in Estonian. Linguistica Uralica 44(4). 268. https://doi.org/10.3176/lu.2008.4.02.Suche in Google Scholar

Erelt, Mati, Tiiu Kasik, Helle Metslang, Henno Rajandi, Kristiina Ross, Henn Saari, Kaja Tael & Silvi Vare. 1995. Eesti keele grammatika I. Morfoloogia. Sõnamoodustus [Estonian Grammar I. Morphology. Derivation]. Tallinn: Eesti Teaduste Akadeemia Eesti Keele Instituut.Suche in Google Scholar

Fuchs, Susanne, Egor Savin, Stephanie Solt, Cornelia Ebert & Manfred Krifka. 2019. Antonym adjective pairs and prosodic iconicity: Evidence from letter replications in an English blogger corpus. Linguistics Vanguard 5(1). 20180017. https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2018-0017.Suche in Google Scholar

Gehrke, Berit & Elena Castroviejo. 2015. Manner and degree: An introduction. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 33(3). 745–790. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9288-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Givón, Talmy & Talmy Givon. 1970. Notes on the semantic structure of English adjectives. Language 46(4). 816. https://doi.org/10.2307/412258.Suche in Google Scholar

Goschler, Juliana & Anatol Stefanowitsch (eds.). 2013. Variation and change in the encoding of motion events (Human Cognitive Processing 41). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/hcp.41Suche in Google Scholar

Grasso, Paolo A., Elisabetta Làdavas, Caterina Bertini, Serena Caltabiano, Gregor Thut & Stephanie Morand. 2018. Decoupling of early V5 motion processing from visual awareness: A matter of velocity as revealed by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 30(10). 1517–1531. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01298.Suche in Google Scholar

Hallonsten Halling, Pernilla. 2018. Adverbs: A typological study of a disputed category. Department of Linguistics, Stockholm University PhD Thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoeksema, Jack. 2012. Elative compounds in Dutch: Properties and developments. In Guido Oebel (ed.), Intensivierungskonzepte bei Adjektiven und Adverben im Sprachenvergleich/Crosslinguistic comparison of intensified adjectives and adverbs, 97–142. Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Kovač.Suche in Google Scholar

Hosmer Jr, W. David, Stanley Lemeshow & Rodney X. Sturdivant. 2013. Applied logistic regression, 3rd edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.10.1002/9781118548387Suche in Google Scholar

Hülsdünker, Thorben, Martin Ostermann & Andreas Mierau. 2019. The speed of neural visual motion perception and processing determines the visuomotor reaction time of young elite table tennis athletes. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 13. 165. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00165.Suche in Google Scholar

Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide (ed.). 2017. Motion and space across languages. Theory and applications (Human Cognitive Processing 59). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/hcp.59Suche in Google Scholar

Ikegami, Yoshihiko. 1969. The semological structure of the English verbs of motion. Linguistic automation project. New Haven, CT: Yale University.Suche in Google Scholar

Ingram, Joanne, Christopher J. Hand & Maciejewski Greg. 2016. Exploring the measurement of markedness and its relationship with other linguistic variables. PLoS One 11(6). e0157141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157141.Suche in Google Scholar

Kasik, Reet. 2015. Sõnamoodustus [Derivation] (Eesti Keele Varamu I). Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus.Suche in Google Scholar

Kiik, Johanna. 2021. Nelja uusklassikalise keelendi kohanemisest eesti keeles: Supermees jooksis hüperkiiresti megaraskel ultramaratonil [Adaptation of the neoclassical prefixes super-, hüper-, mega- and ultra- in Estonian]. Keel ja Kirjandus 64(4). 301–317. https://doi.org/10.54013/kk760a2.Suche in Google Scholar

Koev, Todor. 2017. Adverbs of change, aspect, and underspecification. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 27. 22–42. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v27i0.4123.Suche in Google Scholar

Kopecka, Anetta. 2010. Motion events in Polish: Lexicalization patterns and the description of Manner. In Viktoria Hasko & Renee Perelmutter (eds.), New approaches to Slavic verbs of motion (studies in language companion series 115), 225–246. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/slcs.115.14kopSuche in Google Scholar