Abstract

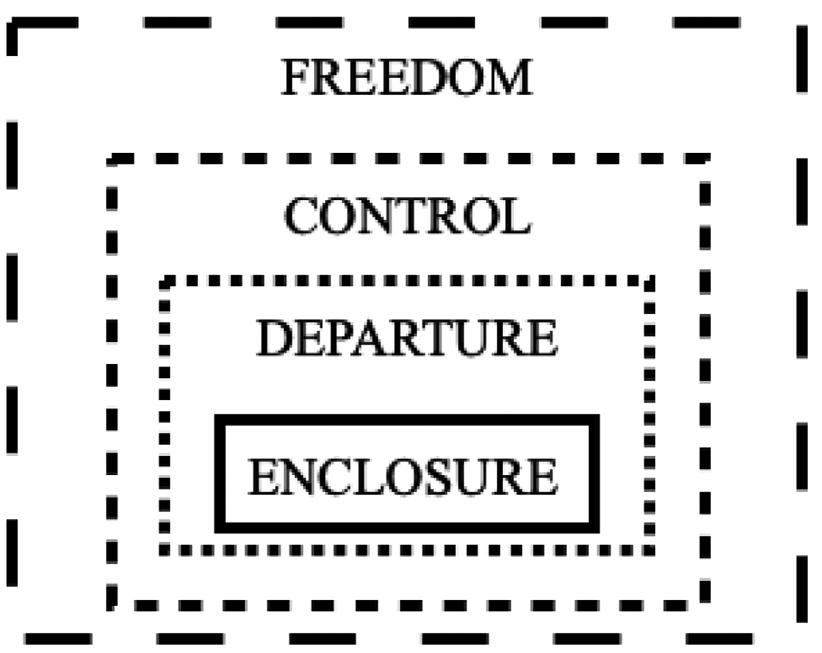

This paper examines the way metaphor was utilized in political discourse on social media in order to delegitimize the European Union. To explore this process, public posts were collected from Twitter during the immediate period preceding the Brexit referendum and were examined for metaphoric language related to Brexit and the EU. The analysis of the tweets showed that more than half of the total tweets concerned the Brexit/EU and incorporated metaphoric language, and underscores the importance of metaphor for politicians on social media. The metaphors in the tweets examined were found to revolve primarily around four metaphoric frames: enclosure, departure, control and freedom; these metaphoric frames constructed the allegory of unjust entrapment, which played a pivotal role in the delegitimization of the EU on social media. Through the metaphoric frames incorporated in their tweets the political leaders sought to delegitimize the EU by presenting it as a place of confinement, akin to a prison, that exerted a restrictive power on anyone inside. The proposed solution to the entrapment and to the effects this had on the people of the UK was for the British to abandon the enclosure of the EU immediately and reclaim their freedom.

Zusammenfassung

Die vorliegende Studie untersucht, wie Metaphern im politischen Diskurs in den sozialen Medien eingesetzt wurden, um die Europäische Union zu delegitimieren. Zu diesem Zweck wurden öffentliche Beiträge aus Twitter aus der Zeit unmittelbar vor dem Brexit-Referendum gesammelt und auf metaphorische Sprache im Zusammenhang mit dem Brexit und der EU untersucht. Die Analyse der Tweets ergab, dass mehr als die Hälfte aller Tweets den Brexit und die EU betrafen und metaphorische Sprache enthielten, was die Bedeutung von Metaphern für Politiker in den sozialen Medien hervorhebt. Die Metaphern in den untersuchten Tweets drehten sich hauptsächlich um vier metaphorische Rahmen: Eingeschlossenheit, Austritt, Kontrolle und Freiheit. Diese metaphorischen Rahmen konstruierten die Allegorie einer ungerechten Gefangenschaft, die eine entscheidende Rolle bei der Delegitimierung der EU in den sozialen Medien spielte. Durch die in ihren Tweets verwendeten metaphorischen Rahmen versuchten die politischen Vertreter, die EU zu delegitimieren, indem sie sie als einen Ort der Gefangenschaft darstellten, ähnlich einem Gefängnis, das eine restriktive Macht auf alle darin befindlichen Personen ausübte. Die vorgeschlagene Lösung für die Eingeschlossenheit und deren Auswirkungen auf die Bevölkerung des Vereinigten Königreichs bestand darin, dass die Briten die EU verlassen und ihre Freiheit sofort zurückgewinnen sollten.

Abstract

Η παρούσα μελέτη εξετάζει τον τρόπο με τον οποίο η μεταφορά χρησιμοποιήθηκε στον πολιτικό λόγο στα μέσα κοινωνικής δικτύωσης με στόχο την απονομιμοποίηση της Ευρωπαϊκής Ένωσης. Για να διερευνηθεί αυτό, συλλέχθηκαν δημόσιες αναρτήσεις από το Twitter την περίοδο αμέσως πριν από το δημοψήφισμα για το Brexit και εξετάστηκαν για μεταφορική γλώσσα που σχετίζεται με το Brexit και την ΕΕ. Η ανάλυση των tweets έδειξε ότι περισσότερα από τα μισά από το σύνολο των tweets αφορούσαν το Brexit/ΕΕ και περιελάμβαναν μεταφορική γλώσσα, γεγονός που υπογραμμίζει τη σημασία της μεταφοράς για τους πολιτικούς στα μέσα κοινωνικής δικτύωσης. Οι μεταφορές στα tweet που εξετάστηκαν βρέθηκαν να περιστρέφονται κυρίως γύρω από τέσσερα μεταφορικά πλαίσια: εγκλεισμος, αναχωρηση, ελεγχος και ελευθερια- αυτά τα μεταφορικά πλαίσια κατασκεύασαν την αλληγορία του άδικου εγκλωβισμού η οποία έπαιξε καθοριστικό ρόλο στην απονομιμοποίηση της ΕΕ στα μέσα κοινωνικής δικτύωσης. Μέσω των μεταφορικών πλαισίων που ενσωματώθηκαν στα tweets τους, οι πολιτικοί ηγέτες προσπάθησαν να απονομιμοποιήσουν την ΕΕ παρουσιάζοντάς την ως τόπο εγκλεισμού, που μοιάζει με φυλακή και ασκεί περιοριστική δύναμη σε όποιον βρίσκεται μέσα σε αυτήν. Η προτεινόμενη λύση για τον εγκλωβισμό και τις επιπτώσεις που είχε αυτός στους πολίτες του Ηνωμένου Βασιλείου ήταν οι Βρετανοί να εγκαταλείψουν τον εγκλωβισμό της ΕΕ άμεσα και να ανακτήσουν την ελευθερία τους

1 Introduction

This study investigates the way the European Union (EU) was metaphorically delegitimized in relation to the United Kingdom’s (UK) membership in the EU as discussed in political discourse on social media (Twitter). In order to do so the present work examines the use of metaphoric frames in Brexit tweets among key proponents of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU[1]. Starting from metaphor, this paper adopts the Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) view of metaphor, according to which in metaphor there is a source domain, a target domain and the mappings between these domains (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). Metaphor in CMT is a means through which we conceptualize the world around us; it enables us conceptualize one conceptual domain in terms of another conceptual domain (Kövecses, 2002). Metaphor no longer belongs to the arsenal of the most eloquent orator (Aristotle, 1457a-1458a), but rather “the way we think, what we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of metaphor” (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980: 3). As opposed to being a rhetorical trope, therefore, metaphor in the CMT view becomes an integral part of everyday communication deeply rooted in our conceptual system. In terms of CMT, this study focuses on the source domain of the metaphors in order to identify the metaphoric frames present in the Tweets. In this case, the source domain is the conceptual domain from which we draw metaphorical expressions to understand another conceptual domain; the aim of this approach is to locate broad consistent patterns of metaphor use based on their source domains that can constitute metaphoric framing devices (Burgers, et al., 2016).

Using metaphor to deliberate about an issue can frame an abstract concept so that we think about it “by drawing on structured knowledge from a semantically unrelated domain” (Thibodeau, et al., 2017: 852), with the semantically unrelated domain being the source domain of the metaphors. Brugman et al. (2019: 46) provide a rather complete definition of metaphoric frames as “frames that represent a metaphorical understanding of the issue under investigation” with (multiple) metaphors associated with general ideas. Based on the source domains of the metaphors, such as the containment schema[2] of the prepositions in/inside that evoke the frame of the enclosure in a three-dimensional space, or the source domain of the American Independence Day and of breaking free that evoke the frame of freedom, the metaphors of the tweets were grouped based on the metaphoric frames stemming from such source domains. As another example, metaphors are used that indicate motion along a path or focus on the end point of the motion schema[3], as shown later in the discussion. For instance, items like leave, and get out fall under one frame, or one general idea – that of departure. Not employing metaphoric frames as general associated ideas would mean that various similar metaphors were viewed independently, and would likely hinder the identification of consistent patterns of metaphor usage in the instances of political discourse examined.

In order to identify the metaphoric items that are required for the identification of the metaphoric frames, the study follows Steen et al. (2010: 111), who refer to “metaphorical items” as lexical items that constitute metaphors. In this study, therefore, the use of “metaphoric items” in the analysis aims to indicate words or short phrases that convey meaning through metaphor. In the examples provided in the analysis all metaphoric items are underlined to highlight their use in political discourse on social media.

Delegitimization is the process through which Others are portrayed negatively by “the use of ideas of difference and boundaries, and speech acts of blaming, accusing, insulting, etc.” (Chilton, 2006: 46). Apart from presenting the Other in a negative way or assigning blame to them, delegitimization can be seen in cases of “scape-goating, marginalising, excluding, attacking the moral character of some individual or group, attacking the communicative cooperation of the other, attacking the rationality and sanity of the other”; in some cases, this process is linked to the extreme act of “deny[ing] the humanness of the other” (Chilton, 2006: 46). Support for Brexit heavily relied on delegitimizing the EU by attributing numerous, if not all, problems faced by the UK to the EU membership as a whole, rather than on specific problematic aspects of the EU’s structure (Jessop, 2017). Thus, for a tweet to be considered as a case of delegitimization of the EU, it had to depict the EU as the Other, rather than part of the collective We, and some form of blame had to be attributed to the EU, with very common cases being migration, law making, or financial freedom, as demonstrated in the analysis of the tweets in this study. Brexit discourse as developed on social media provides a compelling case for studying the metaphoric delegitimization of the EU, especially at the present time, when the EU is confronting numerous challenges to its status quo[4].

The role of metaphor in the delegitimization of the EU is considered of pivotal importance in this study due to the central role of metaphor in political discourse (Thompson, 1996). Metaphor can make complex issues accessible to audiences (Schlesinger & Lau, 2000) or constitute a so-called Great Wall limiting access to information (Thompson, 1996). However, it is the power of metaphor to influence opinions that is central to the discussion of delegitimizing Brexit metaphors on Twitter[5] serving as “prescriptive linguistic devices that guide and shape thinking” (Vavrus, 2000: 194) which can have diverse effects on political enemies, such as to humiliate or to discredit them (Cammaerts, 2012). The use of metaphor in Brexit tweets to discredit the EU is analyzed here in terms of delegitimization and is examined in the context of the allegory of “ unjust entrapment” an allegory of freedom from entrapment based on the conceptual metaphor containers are bounded spaces (Charteris-Black, 2019) with an allegory constituting “a brief story that offers some form of covert ethical comment that cautions the reader or listener indirectly on how to behave when faced with some form of moral question” (Charteris-Black, 2019: 18). In the case examined here, the unjust entrapment relates to the stance that the British people were expected to adopt regarding the membership in the EU, and the urgency to abandon it, as continued membership was perceived to confine them and negatively affect various aspects of their lives.

The present study, by investigating the metaphoric delegitimization of the EU in political discourse on social media (i. e., Brexit tweets), aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. To what extent did Brexit proponents make use of metaphor on Twitter?

RQ2. What were the most frequently used metaphoric frames?

RQ3. How was the EU metaphorically delegitimized among Brexit proponents on Twitter?

By gaining insights into metaphoric delegitimization on Twitter, researchers can understand how metaphor in online political discourse attributes blame and discredits various entities, as well as how they can influence public opinion, especially in the context of significant decision-making processes.

2 Delegitimization

In the world of politics various entities have been victims of delegitimization by opposition parties or other bodies. In this study, the investigation of delegitimization aims to examine and uncover the processes through which the EU became a victim of delegitimization on social media with respect to the membership of the UK during the period preceding the Brexit referendum. Previous research on the delegitimization of the EU explored issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Forchtner & Özvatan, 2022; Filardo-Llamas & Perales-García, 2022). In the case of climate-crisis and COVID-19, for example, Forchtner and Özvatan (2022) identified a “two-dimensional process of narrative delegitimisation” in public debates by the far-right party Alternative for Germany (AfD), with “national elites [being] ‘primary villains’, as compared to the EU [being] less prominently vilified” (1); what is more, various topics in the communication strategy of the AfD were discussed in terms of the metaphor of the “hero/ine” who will save the Germans (21), a type of metaphor present in other discussions of crises such as the war in Iraq in 1991 (Lakoff, 1991). Delegitimisation of political opponents, that is to say, opposition parties, can be also achieved through other means, such as acronyms, similes and metaphors, and through linguistic intergroup bias (Chisango & Gwandure, 2011). In such cases, group belonging is portrayed as desirable while the opposite as undesirable (Spears et al., 2011). Apart from individuals and political parties, delegitimization can be used to target a state by presenting it “in a highly negative light in an effort to have it excluded from the international community and seen as undeserving of its protection” such as the case of Israel and the conflict over the Gaza strip (Cohen & Freilich, 2018: 2). Other relevant research concerns Brexit with a focus on de/legitmization of Brexit by various Labour actors after the referendum. The study revealed an internal conflict in the Labour party regarding the de/legitimization of Brexit and the EU, which was defined by various factors such as the national vs international view of socialism (Zappettini, 2022). In examining the eurosceptic discourse on social media (Facebook) regarding the refugee crisis of 2016–2018 in Italy, Lucchesi (2020) concluded that an anti-Europe, anti-immigration discourse was present in users’ comments on newspapers posts, irrespective of the neutral non-delegitimizing perspective the newspapers adopted (Lucchesi, 2020). In their study on political speeches, Serafis, et. al. (2022) examined a Greek politician’s de/legitmization of the EU’s austerity measures in Greece. The results of their study revealed that the politicians’ argumentation both delegitimized and legitimized the EU’s austerity measures, eventually shifting the politicians’ stance on anti-austerity measures to one of pro-austerity. Delegitimization is a case that is worth researching as it provides insights into the way politicians attack their opponents, or even situations, for their own benefit. What can make research on delegitimization even more interesting, though, is the inclusion of metaphor, to which the discussion now turns.

3 Delegitimization metaphors

Metaphor in delegitimization has been the focus of researchers providing valuable information on the way politicians and other actors delegitimize their opponents or other entities of interest. In investigating monster metaphors in the media coverage of the 2016 presidential election in the United States, Cassese (2017) observes the delegitimizing effect of the Witch hunt metaphor as employed by the media in headlines to delegitimize the attacks of the Republicans on Hilary Clinton, Trump’s opponent in the election race. In another case of research on media, Arcimaviciene and Baglama (2018) examined how metaphor was employed by US and EU media to delegitimize migrants in the so-called migration crisis. Their analysis of the delegitimizing metaphors revealed the myth of dehumanization that was based on metaphors of objects and commodities. Another metaphor through which migrants were delegitimized was the myth of moral authority, expressed though metaphors of natural phenomena, crime and terrorism. The researchers concluded that these metaphors led to the representation of migrants as inanimate objects, their delegitimization further enhanced by the use of metaphor to evoke negative emotions of the audience towards migrants. Cibulskienė (2012) analyzed journey political metaphors of Lithuanian political discourse before and after the country joined the EU and NATO. She observed that the conservative party attempted to attract voters by delegitimizing the opposing party through the metaphor of the opposing party’s governing is a sea voyage. In this case, through metaphors of voyage the government was presented as chaotic and unable to govern the country, as in the case of a captain being unable to steer his ship in the right direction, with the only hope being favourable winds (Cibulskienė, 2012). In examining the metaphors utilized by prominent political figures of Italy, Baldi (2020) shows how the Italian political figure De Gasperi used the religious metaphor of the wolf dressed as a lamb to delegitimize his leftist political opponent by presenting him as the “internal enemy”. Such delegitimizing metaphors are based on dehumanizing political opponents, “aiming to reshape the symbolic universe of persons and bring to light a concealed perception of things” (Baldi, 2020: 365). In examining the use of anti-terrorism discourse by Spanish president Zapatero, Hellin-García (2013) discusses the delegitimization of terrorism through building metaphors. Her analysis of the president’s speeches revealed that stable building constructions were related to the legitimization of the government and its initiative against terrorism, while, in more limited cases, metaphors of implied lack of foundations, destruction and obstruction were utilized to delegitimize criminal acts in the president’s speeches. The investigation of metaphor as a delegitimization device is a fertile area of study and calls for more research in order to uncover how the politicians, media, and other bodies that produce public discourse utilize this conceptual mechanism to alter their audiences’ perspectives on their opponents or competitors. By investigating metaphoric delegitimization, this study aims to contribute to the existing literature by examining how proponents of Brexit used metaphors to delegitimize the EU within the specific context of social media. More specifically, it seeks to uncover consistent patterns of metaphor use in terms of delegitimization under the Brexit referendum.

4 Brexit metaphors

Research examining Brexit metaphors in speeches by political leaders in the UK concluded that the most common source domains were those of war and journey (Rodet, 2020), with journey metaphors also appearing in Brexit political cartoons (Đurović & Silaški, 2019). Đurović and Silaški (2018) investigated how Musolff’s (2006) married partners metaphor scenario was used in Brexit. Their analysis revealed that the metaphors of both marriage and divorce played an important role in better explaining the relationship between the EU and the UK in media discourse. Musolff’s (2017) research on the slogan, Britain at the heart of Europe in the British press from 1991 till 2016 showed that its use shifted from positive to negative, eventually being associated with metaphors of disease and death. In another case, Musolff (2019) examined the use of the proverb you can(’t) have your cake and eat it by Boris Johnson; he concluded that the proverb was used in four different ways depending on whether this use was in support of or against the UK leaving the EU. In his more recent research, Musolff (2021) points out that the combination of metaphor with hyperbole, in the case of this proverb, has a more intense emotional and “polemical” effect on the pro-Brexit argument in the short term.

Freedom was a significant issue in metaphoric discourse on Brexit, which is of importance to the present research, as will be shown later. Research conducted by Buckledee (2018) demonstrated how the Brexit campaigners used metaphor in headlines, leads, and articles, to picture the EU as restricting the freedoms of the people of the UK, while Koller et al. (2019: 6) comment on the use of visual metaphor in the campaign video by UKIP’s ‘We’re Better Off Out’, in which case the EU is presented as a prison in the form of a dark chicken warehouse, with brave chickens escaping it. Charteris-Black (2019), by drawing data from a variety of sources, discusses metaphors of Brexit from both the Leave and Remain perspectives; his analysis revealed the allegory of the unjust entrapment which was prominent in Boris Johnson’s Brexit-related discourse. Although past research has focused on metaphors of Brexit by drawing data from various sources, these studies have not examined Brexit metaphors on social media, the contemporary platform for public discourse. This paper, by drawing data from social media, adds to the discourse on Brexit metaphors the perspective of social media and documents how politicians, through such a medium, metaphorically communicated issues surrounding the EU in the context of Brexit to their audiences.

5 Brexit on Twitter

With respect to Brexit-related language on Twitter, tweets by political actors have attracted the attention of researchers, although not necessarily those with a specific focus on metaphor and delegitimization. Usherwood and Right (2017) examined tweets by the three main groups of Brexit advocates, namely StrongerIn, Vote Leave, and Leave.EU; their analysis showed that all groups made almost equal use of positive and negative content and frames, with StrongerIn using “Project Fear”. Outright lies have also been observed in politicians’ tweets; politicians, aware of the power of social media, use them to “ ‘turbo-charge’ the ‘strategic lie’ in setting, framing, and priming of news agendas to suit their campaigning ends” (Gaber & Fisher, 2022: 472). Rosa and Jiménez (2020) examined how key political actors of Brexit used Twitter in the final weeks leading up to the referendum. Their research focused on appeal to emotions versus rational arguments, as well as the impact of the politicians’ tweets. Regarding the former, emotions did not prevail over rational arguments, yet had the researchers taken into account metaphorical vs non-metaphorical arguments, this finding might have been different, as metaphor is a means of appealing to the emotions (Mio, 1997). Regarding the impact of the politicians’ tweets, their analysis showed that Boris Johnson’s tweets had a higher impact than those of the other politicians (i. e., engagement: likes, retweets) (Rosa & Jiménez, 2020).

Of particular, albeit limited, interest to the present study is the work by Angouri et al. (2018) whose research touches on the issue of metaphor without explicitly addressing it. In their study, Angouri et al. (2018) compared the tweets of the Greek and UK Prime Ministers during the referendums held in both countries. Their results documented an emphasis on emotion despite the differences between the two politicians and the political contexts. In their analysis of the data, the authors mentioned some cases of metaphoric tweets; however, there was no systematic analysis of these instances or of relevant tweets that could have provided insights into metaphor use on Twitter. Other research examined tweets produced by the general public concerning Eurosceptisism (Hänska-Ahy & Bauchowitz, 2017) and the referendum result itself (Khatua & Khatua, 2016), but again without a specific focus on metaphor use.

The research on Twitter and Brexit discourse discussed in this section highlights the importance of social media for political discourse and the study of metaphor. The most common approaches to Twitter focus on how politicians use their tweets to appeal to or affect the emotions, as in the case of “Project Fear” (Usherwood & Right, 2017). Thus, the study of social media can contribute to our understanding of how politicians utilize these communication platforms to influence public opinion and their electorate (Daniel & Obholzer, 2020; Fazekas et al., 2021), and also how specific types of language such as metaphor contribute to the overall power of online political discourse.

By exploring a variety of topics, previous researchers offer valuable insights on Brexit-related discourse, yet numerous issues have not yet been explored. Research on Brexit metaphors reveals a lack of scholarship that focuses specifically on the use of Brexit metaphors on Twitter/X and the use of metaphorical language to delegitimize the EU on social media. Additionally, research on Brexit discourse that drew data specifically from Twitter did not adopt a particular stance on metaphor use nor on metaphoric delegitimization. The present research aims to fill the gaps left by previous scholarship; thus, this study incorporates and systematically examines Brexit metaphors on Twitter used by key Brexit political figures and analyzes their effect in delegitimizing the EU.

6 Study: Method & Data

The instances of political speech (tweets) were collected from Twitter as this social media platform is more closely linked to politics than other social media (Ross & Burger, 2014) and span from the 1st of June until the 23rd, the day of the referendum. The choice of this period is based on research that revealed “a very marked rise” in the volume of tweets by Twitter accounts related to Brexit after the 1st of June (Usherwood & Wright, 2017: 377). To collect the tweets, the native Twitter search engine was used, and an advanced search string was produced. Since including multiple variables limited the number of results to ten tweets per search, a simpler advanced search was preferred that included one account and a period of one day[6]; this search was renewed for every day and each account independently, resulting in 69 search strings.

In order for a tweet to be included in the corpus, two criteria had to be met: first, the tweet had to include a metaphor, and second, it had to be Brexit and/or EU related; if a tweet was focused on Brexit/EU but did not include a metaphor, or vice versa, if it included a metaphor but was not focused on Brexit/EU, the tweet was excluded from the corpus.

Coding for metaphor was performed following the Metaphor Identification Procedure VU (MIPVU) (Steen et al., 2010), which involves locating possible metaphoric words in text and comparing their contextual meaning to the most basic meaning of that item in a dictionary, which is defined as “a more concrete, specific, and human-oriented sense in contemporary language use” (Steen et al., 2010: 35).

In the data examined, the use of the word leave in the string the UK to leave the EU constitutes such a case. The basic meaning of leave as provided in the Longman Dictionary[7] is “to go away from a place or a person;” this sense is distinct from that of leave as used in the tweets, in that the UK would not physically walk away from the EU, but would rather withdraw its participation from a group of other counties, i. e., the EU. A challenge in identifying metaphors in tweets can be related to the contextual meaning of the lexical items due to the limited space for a tweet to develop. Difficulties may arise in cases “[w]hen utterances are not finished” or “[w]hen there is not enough contextual knowledge to determine the precise intended meaning of a lexical unit in context” (Steen, et al., 2010: 33). Such challenges, however, did not appear in the cases examined, as the one of the two criteria for inclusion of a tweet specified that it had to be Brexit/EU related; therefore, the context was a prerequisite. Furthermore, because the platform allows only a limited number of characters, the politicians did not leave any of their tweets unfinished. Although it might be difficult to determine the contextual meaning in some cases, this problem did not arise in the present study.

To identify the metaphoric frames of the tweets, I focused on the source domains of the metaphor(s) by applying the MIPVU procedure and establishing the basic meaning in the dictionary (Brugman et. al., 2019); the frame “was coded as metaphorical when the name of the frame implied a comparison between a political domain (target domain) [in our case, Brexit or the EU] and a non-political domain (source domain)” (Brugman et. al., 2019: 48). Metaphors characterised by common source domains that belonged to the same concept, such as freedom, were grouped as common metaphoric frames based on Brugman’s definition of metaphoric frames as provided in the beginning of this paper. To give an example, one of the most common metaphoric frames was that of CONTROL. The metaphors that comprised this metaphoric frame included the metaphoric lexical item control in the context of the relationship of the UK with the EU, primarily in cases of regaining CONTROL from the EU, as in #Take back control. All cases of non-physical control that referred to Brexit or the EU were grouped under the metaphoric frame of CONTROL. Another frequent metaphoric frame, to be analyzed later, was that of DEPARTURE, based on the motion schema. This case was characterised predominantly by the lexical item leave, used metaphorically in the Brexit context, indicating that “[a]n object (the Theme) moves away from a source” (FrameNet: Departing, Ruppenhofer et al. 2016). All instances of leave were categorized in the DEPARTURE metaphoric frame, and the frame characterized as metaphoric, since no physical motion of abandoning a location was included in the tweet. However, if leave referred to the actual action of departing from a location this was not included in the metaphoric frame of DEPARTURE.

The politicians’ accounts that have been examined are @BorisJohnson (@BJ), @Nigel_Farage (@NF), and @pritipatel (@PP), all prominent supporters of Brexit[8]. Other political accounts examined included @Geoffrey_Cox, whose tweets did not meet the criteria to be included in the corpus, as well as Ann Widdecombe and Jacob Rees-Mogg, both of whom did not have a Twitter account before the Brexit referendum. In total, 191 tweets were examined for the period in focus. Of these tweets, 102 were related to Brexit/EU and employed at least one metaphor; Table 1 shows the distribution of tweets among the accounts examined. The percentages correspond to the metaphoric tweets that each politician produced individually in their online discourse during the period leading up to the referendum.

Number of tweets examined

| Account | Total tweets | Metaphoric EU/Brexit tweets | Met. Tweets % |

| @BorisJohnson | 40 | 13 | 32.5 |

| @Nigel_Farage | 116 | 71 | 61.2 |

| @pritipatel | 35 | 18 | 51.4 |

| Total | 191 | 102 | 53 |

Examples 1–3 below are instances from @BJ that were either excluded or included in the analysis according to the two criteria specified above. Example 1 fulfills one of the two criteria for inclusion, as it concerns the EU (EU-undemocratic); however, since none of its lexical items was coded as a metaphor, this instance was excluded from the corpus.

(1) And how many people can name their Euro MP? The EU is totally undemocratic#VoteLeave #InOrOut

In Example 1, the items “#VoteLeave” and “#InOrOut”, although metaphoric, were not included in the evaluation as they are not part of the syntactic/grammatical structure of the text/tweet but function as “social metadata” (Zappavigna, 2015)[9]. Removing the #VoteLeave from the tweet does not affect the grammatical structure of the tweet or alter the concept of the EU being undemocratic, as it is not embedded in the linguistic structure. In such cases #hashtags perform the indexing function (tagging) of the platform and do not contribute to the meaning of the tweets. Had the #hashtag metaphoric items been part of the text/tweet, i. e., a component of the linguistic structure contributing to its overall meaning, these would have been included in the analysis. Such a case is #TakeBackControl of our country (Example 8) in which tweet the # is part of the grammatical structure and contributes to the meaning of the tweet; thus the #metaphor is included in the analysis.

Example 2 includes the metaphoric items blackhole and break; however, since the tweet is not related to the EU or Brexit, it was not included in the analysis.

(2) Throughout the campaign Khan was asked how he’d fund his £2bn transport budget blackhole. Answer – break his promise

Example 3 includes four metaphoric items (wake up, nightmare, stay in, leave) and is related to the EU and Brexit; thus, this tweet was included in the analysis.

(3) Don’t wake up to the nightmare of staying in the EU on June 24th. Believe in Britain and vote Leave

7 Results

7.1 Frequencies of metaphoric #Brexit tweets

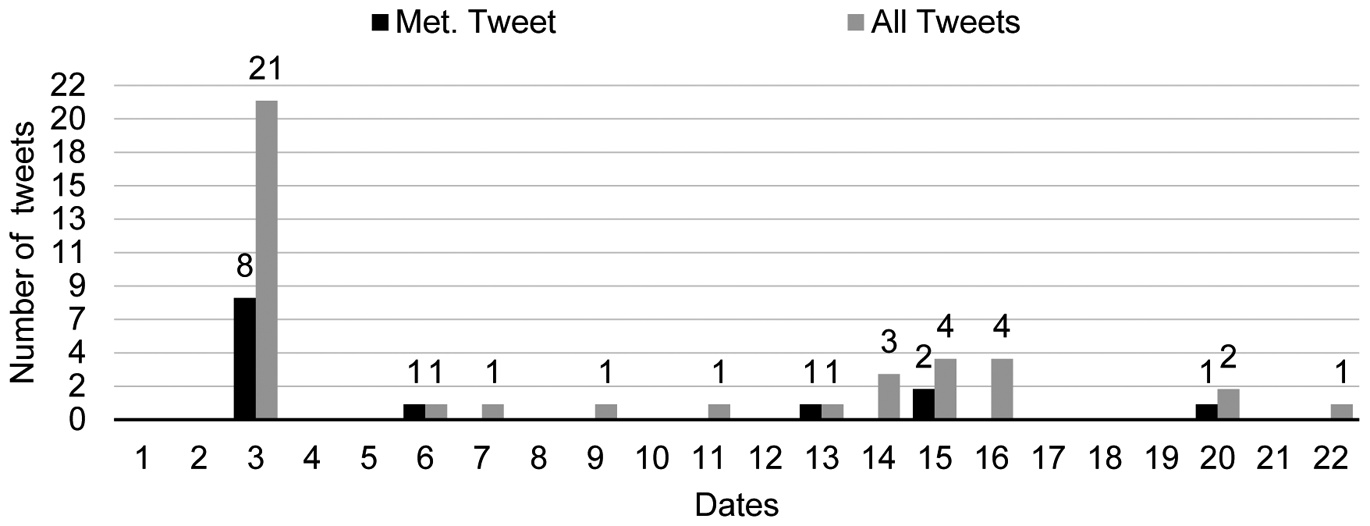

Figures 1–3 show the distribution of each account’s tweets during the period under examination. Overall, @BJ (Figure 1) made limited use of the platform with half of his tweets published on the 3rd of June, which was the day of Michael Gove’s[10] interview to Faisal Islam on Sky News in support of Brexit. The rest of his tweets are scattered across the following days, leading up to the referendum, with a small increase around the 15th of June. Of all his tweets, 32.5 % were metaphoric and related to Brexit/EU (Table 1).

Frequencies of tweets and of metaphoric tweets by @BorisJohnson

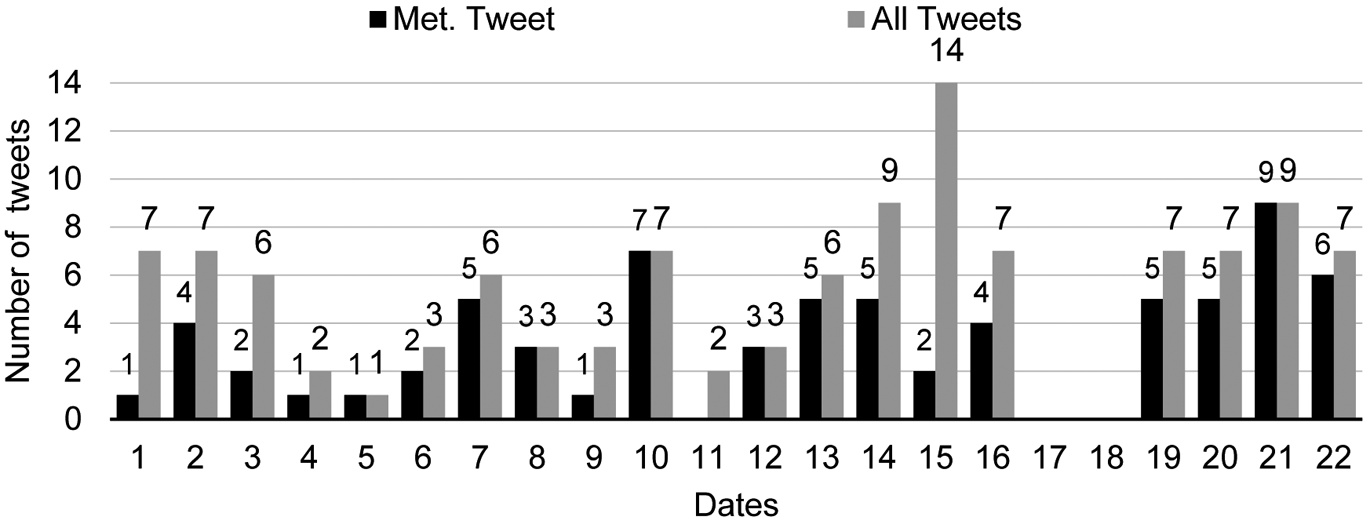

@NF (figure 2) made extensive use of the platform, publishing on a regular daily basis. The peak on the 15th of June is a result of @fishingforleave, a flotilla of fishing boats traveling up the Thames led by Nigel Farage in support of Brexit[11]. The lack of tweets after the 16th follows the murder of politician Jo Cox and is observed in all accounts examined. In terms of metaphor use, 61.2 % of @NF’s tweets were metaphoric and related to the Brexit/EU, which is the highest use of metaphor observed among the three political leaders that were examined.

Frequencies of tweets and of metaphoric tweets by @Nigel_Farage

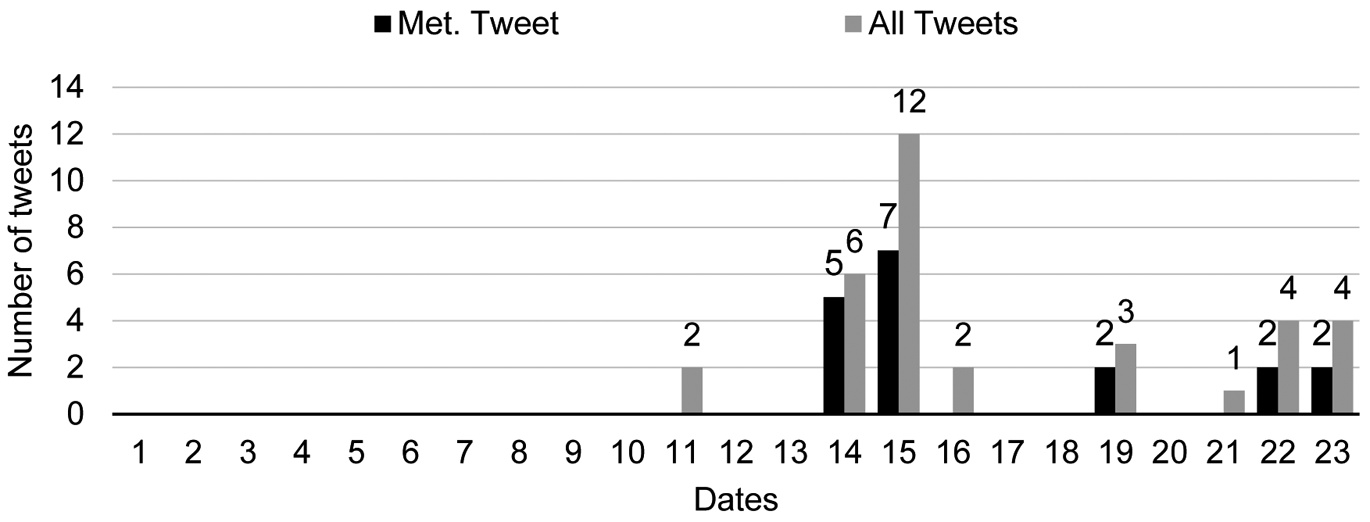

In the case of @PP (Figure 3), no activity is present for up to two weeks before the referendum. Like the account of @NF, a peak is observed on the 15th of June the day of the flotilla in support of Brexit. Most of @PP’s tweets cluster around this date, while the remaining tweets appear the last few days leading up to the referendum. In terms of metaphor use, 51.4 % (Table 1) of her tweets were metaphoric and related to Brexit/EU.

Frequencies tweets of and of metaphoric tweets by @pritipatel

Overall, a single pattern of tweeting cannot be identified in the frequencies presented in Figures 1–3, as all three accounts demonstrate their own pattern of Twitter use. Table 2 shows the distribution of metaphoric tweets among the politicians. It is clearly demonstrated in the table that @NF, an ardent supporter of Brexit, produced the most metaphoric #Brexit tweets throughout this period (69.6 %) (Table 2). @PP and @BJ published a limited number of metaphoric #Brexit tweets, focusing primarily on specific days/events, 17.6 % and 12.7 % respectively (Table 2). The analysis of the frequencies addresses RQ1, which asks about the extent of metaphor use in the tweets examined. Overall, more than half of the tweets published used metaphoric language, indicating the importance of metaphor for politicians on social media. Of these tweets, the majority was produced by @NF; consequently, these tweets are central to the analysis that follows.

Number of metaphoric Brexit tweets by account

| Account | Metaphoric EU/Brexit tweets | % of metaphoric tweets among accounts |

| @BorisJohnson | 13 | 12.7 |

| @Nigel_Farage | 71 | 69.6 |

| @pritipatel | 18 | 17.6 |

| Total | 102 |

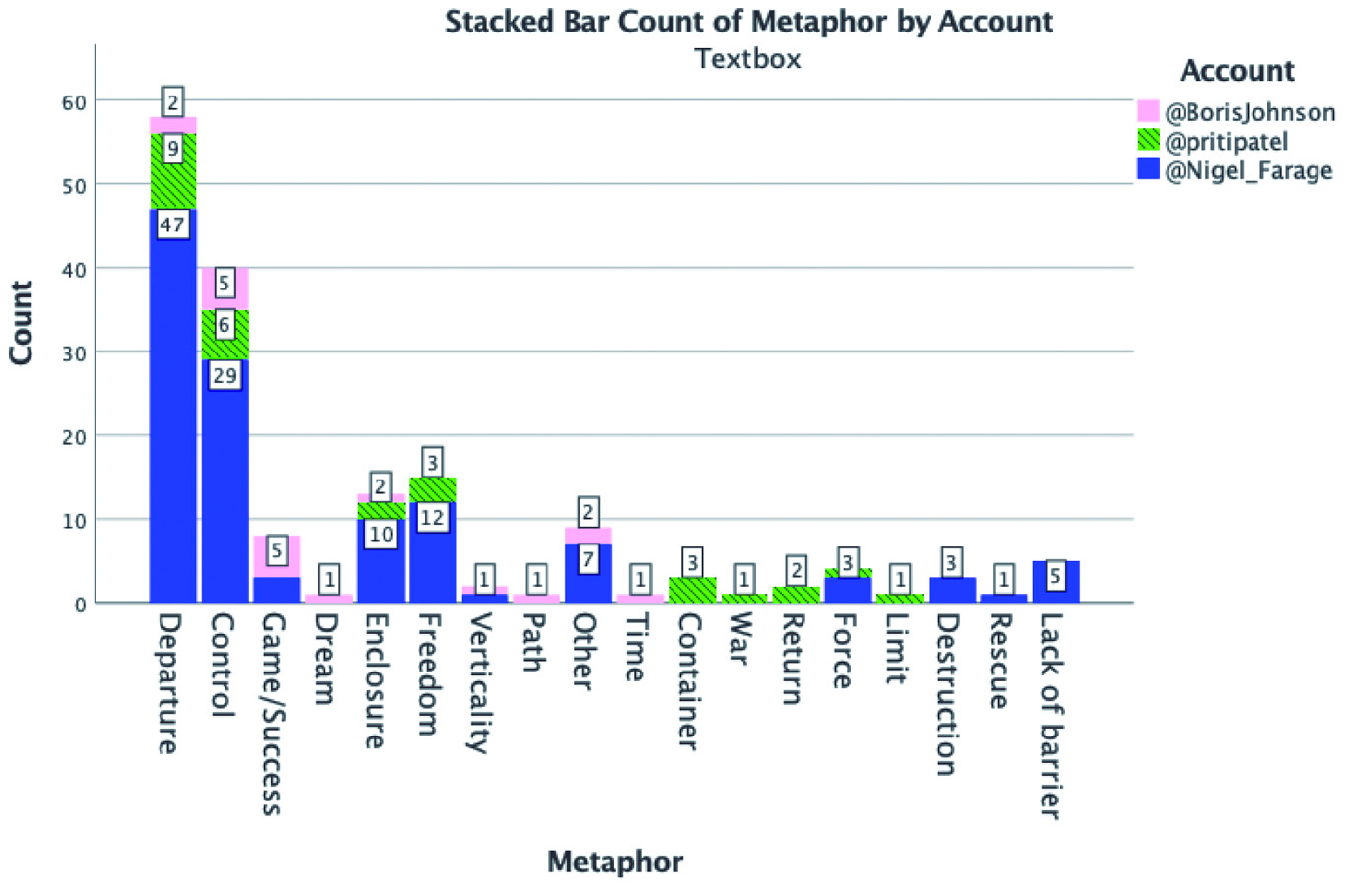

7.2 Metaphoric frames

Table 3 presents the metaphoric frames identified in the tweets examined, as well as their distribution by account. Overall, 26 metaphoric frames appeared in the data. The most frequently occurring metaphoric frames were departure, control, freedom, and enclosure. The departure frame appeared 58 times and was expressed mostly through the lexical item leave; the departure frame accounts for 34.5 % of all the metaphoric frames and was the most frequently used. The Twitter account that used the departure frame the most was that of @NF, who repeated it 47 times during the period examined, followed by @PP, who repeated it 9 times, with @BJ using it only twice (Table 3).

Control was the second most frequently used metaphoric frame. It appeared 40 times, accounting for 23.8 % of all the metaphoric frames. This metaphoric frame appeared in the tweets mostly as Take back control (of X). In terms of Twitter account use, control was used most frequently by @NF, with 29 instances, followed by @PP and @BJ who used it 6 and 5 times respectively. Of the remaining commonly occurring metaphoric frames, i. e., freedom (15 repetitions) was used 10 times by @NF and three times by @PP while none by @BJ; enclosure (13 repetitions), commonly indicated by three-dimensional prepositions, was used 10 times by @NG, once by @BJ and twice by @PP.

List of metaphoric frames & metaphor frequencies[12]

| Metaphoric frames | Metaphoric Frames by Account @NF@BJ@PP | Total Frequency of Metaphors | Total % | ||

| departure | 47 | 2 | 9 | 58 | 34.5 |

| control | 29 | 5 | 6 | 40 | 23.8 |

| freedom | 12 | 0 | 3 | 15 | 8.9 |

| enclosure | 10 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 7.7 |

| game/Success | 3 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 4.8 |

| lack of barrier | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1.9 |

| force | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1.8 |

| destruction | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.8 |

| container | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1.2 |

| return | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1.2 |

| verticality | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Miscellaneous | – | – | – | 15 | 8.9 |

| Total | 168 | 100 % | |||

Chart 1 presents all the metaphoric frames identified in the tweets examined by account. The analysis reveals the prominence of the departure and control metaphoric frames, which account for 60 % of all metaphoric frames used by the politicians under study. Less frequently used, but significant nonetheless, were freedom, and enclosure. The frequencies of the metaphoric frames are relevant to the second research question (RQ2) regarding which metaphoric frames were used most frequently during the period of study. These frames were: departure, control, freedom and enclosure.

Number of metaphoric frames by account

7.3 Metaphoric frames of the Brexit/EU: towards delegitimization

departure

The departure frame, expressed mainly through the metaphoric item leave, played a significant role in the discourse of #Brexit, not only as part of published tweets but also as part of the communication strategy of the Leave campaign (Charteris-Black, 2019). Example 4 presents the use of the departure frame through leave.

(4) This is one vote that can really change things. Vote for your country. Vote to Leave EU. (@NF)

An important function of leave in all relevant cases is that it draws the audience’s attention to the point of departure, whether stated explicitly or not[13]. Example 4 is a case in which the point of departure is explicitly mentioned; leave is followed by the abbreviation EU, directly indicating to the audience the location that they must abandon to change their lives. Leaving the EU entails starting from a point, moving along a path, and reaching a destination. In Example 4, the politician focuses on the starting point, which is probably a place not good to be at/in, leaving out of the discussion the path and the endpoint. In the cases of leave, the source of departure is always present, whether mentioned or not, and “[f]or those supporting Leave, the EU was framed as a type of container from which the UK needed to break out in order to gain its freedom” (Charteris-Black, 2019: 144), as exemplified in the rest of the analysis. In terms of the frame of departure, what mattered was to depart from a place of confinement, probably a three-dimensional space, such as a container, as indicated through get out, a different type of motion (Example 5). In this case the political party leading the vote to leave the EU presents itself as the saviour who will help deliver the UK from an enclosed container.

(5) We in UKIP are today launching the biggest advertising campaign in our history to get our country out of the EU. (@NF)

Example 6, still in the realm of leave, does not make a direct reference to the EU as the point from which to depart but rather implies it as part of the frame of departure, interacting with the context of the Brexit referendum.

(6) Vote to Leave on Thursday and make June 23rd our Independence Day. (@NF)

What is important in terms of the metaphor leave, whether stated explicitly or implicitly, is the point of departure, i. e., the EU, which was the issue at stake in the referendum. In this example, although not stated, the audience understands that the place to leave is the EU. Example 6 urges the politician’s audience to abandon a place of confinement and lack of freedom, clearly demonstrated through the term Independence Day, which indicates freedom from an illegitimate authority such as a ruler or a captor. The third metaphoric item, which appears in a limited number of instances and contributes to the departure frame, is outside (Example 7). This type of metaphor indicates the endpoint on the motion schema that completes the departure frame. Therefore, starting from the location of being in the EU, the UK will experience better circumstances once it has reached its final destination, which is none other than being outside the influence of the EU. This will be achieved when the UK metaphorically achieves the aim of its departure, which is to be in a new location.

(7) Looking forward to my interview with @afneil on BBC1 this evening. We will be safer and better off outside EU. (@NF)

control

control highlights the main benefit of not being a member of the EU – specifically, not being dependent on or limited by someone else. Since at that time the UK was part of the EU, the control metaphoric frame focused on the lack of control by the UK as the main drawback of EU membership, suggesting that the EU had illegitimate power over the UK and that the referendum was the last opportunity to reclaim control from the EU, as shown in Example 8.

(8) @BorisJohnson in Maldon this morning #VoteLeave. Last chance to #TakeBackControl of our country. (@PP)

In this case, an entity other than the UK is in charge of the country. By voting in favour of Brexit, the people of the UK would take advantage of this last chance and reclaim the ability to make decisions for their own country from another implied entity which is no other than the EU. Participating in the EU project deprives the UK citizens of the ability to make their own decisions, or even to be masters of their own country. The importance of reclaiming their ability to make decisions for themselves, in this case in terms of borders, is enhanced in Example 9 in terms of morality by the use of golden[14], a metaphor or “evaluative adjective” which “makes moral evaluation covert and seeks to shield it from debate and argument” (van Leeuwen 2007: 98).

(9) We must seize this golden opportunity to Leave the European Union and take back control of our borders. (@NF)

Example 10 presents a different type of restriction imposed by the EU on the citizens of the UK, a supernatural one, in which case the EU exercises power to decide on the destiny of the country.

(10) Vote to Leave EU and let’s take back control of our country’s destiny. (@NF)

The frame of (lack of/retaining) control over specific issues or even over one’s own destiny can indicate that this person/entity has been deprived of its own volition, possibly by being in prison; this person cannot determine their own future. The lack of volition in Example 10 is further emphasized by leave, or departure, as the entity is depicted as being entrapped in a physical space, with the result that it is deprived of its ability to act on its own but now has the chance to change its circumstances. This prison-like place is identified as the EU, and the UK citizens are depicted as trapped, unable to define their own futures for as long as they are contained within it.

Another way control is expressed in the metaphoric items in the tweets is through ownership. Getting something back, Example 11, indicates the importance for the UK to reclaim from the EU some of its core institutions, such as its borders, its democracy, and the country itself. By reclaiming ownership, the people of the UK can regain control of these core institutions and define how they function. The institutions mentioned in this tweet become objects, or commodities, to be returned to the UK so that its people can, metaphorically, hold them in their hands and therefore control them as they wish (Example 11).

(11) It’s time to get our borders back, our democracy back and our country back. #Brexit (@NF)

enclosure

The metaphoric frame of enclosure is depicted particularly by the use of spatial prepositions such as in or inside, which denote a three-dimensional space such as a container. This three-dimensional space is a problematic place to occupy, as its inherent failures are transferred to those that are inside it, such as the UK and the British people. In Example 12, being in this space, and thereby being subjected to its influence, poses a serious risk for the security of the nation. For as long as the UK is located in this enclosure, it is up to the enclosure (EU courts) to make decisions on behalf of the UK.

(12) Staying in the EU is a risk to our national security. European courts decide who we can refuse entry to and deport from the UK (@PP)

Another problem attributed to the enclosure of the EU relates to immigration; in Example 13, the enclosure, indicated by the metaphoric items remain and inside, fails, quite ironically, because it is open.

(13) If we Remain inside EU with open borders our population will rapidly rise to 80 million by 2040. (NF)

Being inside a three-dimensional space that is open suggests a container that is not sealed to prevent or protect it from intrusion. Such a container could be used primarily for storing liquids, or it could be used for storing a variety of materials, including liquids. This use could be entailed by the verb rise, as in the case of water levels rising in a flood, with flood as a common metaphor used to depict immigration (O’Brien, 2003; Charteris-Black, 2006). As long as the UK remains in the malfunctioning container of the EU, there is no escape from the rising levels of water, which represent imagistically the increase in numbers of immigrants. The restrictive power of the enclosure does not allow for freedom of action to close the container and limit immigration.

Another instance based on the image of a malfunctioning enclosure is provided in Example 14. In this example, as in the one above, the problem is a result of the enclosure itself. The effects of the problematic enclosure are such that they negatively impact the quality of life of those within it. Such an image of faulty enclosure could imply that the only way to avoid being affected is to abandon the container and go elsewhere.

(14) Quality of life matters more than GDP. Our infrastructure is at breaking point inside EU. (NF)

Overall, the enclosure indicated by a three-dimensional space exerts its power on those inside and restricts their freedom of choice and action. By being in a malfunctioning container, British citizens are subjected to its problematic nature or restrictive powers that limit their scope of action for as long as they are inside. The problematic enclosure wields illegitimate power over those inside, causing harm to them and putting their existence at risk.

freedom

The last metaphoric frame to be discussed is that of freedom, which along with the metaphoric frames presented above, completes the scenario developed on Twitter of the unjust entrapment, as discussed later. In Example 15, an entity, we, is the agent empowered to end its captivity imposed by the captor, i. e., the EU, by breaking free. In this case, the EU is metaphorically conceptualized by the audience as the captor, the prison or the chains that have deprived them of their ability to control their own affairs, while they themselves are the hostages. In this example, the EU has illegitimate power over its victim, and the latter must first to escape from its captor to regain the ability to make decisions for itself.

(15) We must break free of the EU and take back control of our borders. (@NF)

Example 16 focuses on the outcome of the referendum, i. e., an entity, whether a person or a country, having regained its freedom from its captor. Now this free entity can make its own decisions and vote on its own laws, just as it could in the past, indicated by the phrase once again. Furthermore, the free entity can once again move freely, something which was not possible at that time.

(16) #IVotedLeave so we can once again be a self-governing country free to make our own laws and our own way in the world. (@PP)

The use of the phrase Independence Day, as shown in Example 17, makes a rather bold claim regarding the relationship of the UK with the EU. Quite ironically in this case, the metaphor used by the politician indirectly presents the EU as a Monarch or a ruler from whom UK citizens must reclaim their freedom; as discussed above, recovering one’s freedom is the ultimate aim of the victim in the case of the unjust entrapment allegory. This meaning draws on encyclopedic knowledge of United States history, particularly the period during which settlers in the new colony declared independence from the Monarch of Britain, King George III.

(17) The odds are certainly shifting for Leave. I’m delighted. Let’s make June 23rd our Independence Day. (@NF)

The metaphoric frames of departure, control, enclosure and freedom, examined in the tweets above, align with the allegory of the “unjust entrapment” (Charteris-Black, 2019) and construct this allegory in the world of social media in an attempt to delegitimize the EU. The interaction of these frames in the social world of Twitter present “Britain as struggling to gain its freedom from imprisonment within the EU”, and suggest that “being part of the EU, the UK was trapped within a container from which it sought to liberate itself by breaking out into a free world” (Charteris-Black 2019: 144).

8 Metaphoric delegitimization of the EU in four steps: the allegory of unjust entrapment.

The metaphoric frames of departure, control, freedom, and enclosure contribute to the delegitimization of the EU by building “concepts of physical constraint and release from constraint”, giving rise to the allegory of unjust entrapment (Charteris-Black, 2019: 167). Through these metaphoric frames, the politicians managed to delegitimize the EU as a whole for the allegedly negative influence it had on the UK. By attributing blame to the EU for the challenges that the UK and the British people were facing, the politicians constructed the EU as the Other. The EU was metaphorically a place that was hostile to the interests of the UK, an inhumane political entity, an enemy Other that deprived the UK of its will and more importantly its freedom. It can be argued that collectively, these metaphoric frames even questioned the sanity of the EU with regards to its relationship to the UK. The EU was conceptualized as a prison guard or a ruthless ruler who wielded absolute power over the UK and its people. This metaphoric conceptualization of the EU was built within the allegory of the unjust entrapment, which is developed throughout the data in four steps as illustrated in Figure 4. In this configuration, being closer to the centre, i. e., enclosure, delegitimizes the EU membership and the EU as a whole, while each step towards the periphery legitimizes the decision to leave the EU[15].

Stages of delegitimization of the EU

Starting with the enclosure frame, depicted by the continuous line in the centre of Figure 4, the EU is conceptualized as a container that restricts the ability of the UK to act for itself, a metaphor drawing from the conceptual metaphor containers are bounded spaces. For as long as the UK remains within this bounded space it will experience strife and turmoil, due to the power exerted and the restrictions imposed by the enclosure. In this confining space, the British people have lost the ability to define their present and future, akin to prisoners unable to define their own lives while confined to the enclosure of their cells. Being confined within the enclosure of the EU not only limits the actions of the British people, but it also restricts their freedom; such restriction is evident in the last metaphoric frame discussed in this section. The EU is the restrictive place that has deprived the UK of its ability to make political and economic decisions of its own, similar to the condition of someone being held captive or imprisoned. The EU is thus an illegitimate place, and the UK should not remain inside. The metaphoric frame of enclosure strongly urges the people of the UK to react and abandon the place of confinement as “[w]e know that our bodies resent being physically trapped –whether in wrestling or when arrested and that the natural response is to struggle for freedom from such entrapment” (Charteris-Black, 2019: 174). The EU, as a place of confinement, is not a legitimate space to occupy, so it is better to move out. The departure frame that follows (i. e., indicated by dotted lines in Figure 4) reminds the British people of the need to take action.

Since the tweets identified the EU as the illegitimate place where the British were trapped, the next step is to direct them on how to react. The metaphoric frame of departure offers the solution to the problem of the enclosure and further delegitimizes the point of departure, i. e., the EU, since staying inside would only cause more harm and deprive the British people of the opportunities that are waiting for them, as illustrated by the next two steps in Figure 4. The departure frame, primarily evoked through the metaphoric item leave, was the most prominent metaphoric frame in the political tweets, and defined the plan for the British people to follow regarding their relationship to the EU. Although abandoning the EU as a political and economic entity would not be an easy task due to the numerous bureaucratic complications, the departure frame made the process seem as simple as abandoning a place where someone feels dissatisfied. The British people were portrayed as having a unique opportunity to move out of the EU in a single step. Whether the EU was conceptualized as a three or two-dimensional space, abandoning it would be as easy as walking away from a place they should never have occupied in the first place. This is an illegitimate place, and the need to abandon it delegitimized it even further. Having established the place (container) and its negative properties, as well as the single action to take (departure) in order to stop its negative effects, the next metaphoric frames further enhanced both the delegitimization of the EU as well as the legitimization of withdrawing from it. These metaphoric frames highlighted the benefits that would result from leaving, the most important of which is to restore what the EU had taken from the British people.

The important benefit of abandoning the illegitimate enclosure of the EU is the much-desired control, depicted by small dashes in Figure 4. This metaphoric frame plays a crucial role in the delegitimization of the EU as it explicitly states what the British people lost while being in confinement by the EU. Lack of control reinforces the belief, already prominent among the audience of the politicians, that the EU affected them negatively by depriving them of their most fundamental abilities, individually as free citizens and collectively as a country. This ability to act on their own affairs by exercising control over their own lives was not possible during their confinement in the EU, as the EU, and not their country, made crucial decisions on many aspects of their lives. The metaphoric frame of control indicates to UK citizens that their former ability to make their own decisions could easily be restored by following a few simple steps; the first would be to recognize the negative influence of their enclosure and the second to abandon it as soon as possible. Enclosed within the EU, the UK did not have control over its own matters; this suggests that the EU had excessive and illegitimate power over the UK, similar to that which a ruler or a prison guard exerts over enslaved people or prisoners. By having departed and restored control one is close to the final aim, that of freedom.

The final and most crucial step towards delegitimizing the EU through the allegory of unjust entrapment is specified by the metaphoric frame of freedom. After realizing the disadvantages of remaining within the EU, including loss of freedom, citizens of the UK opt for freedom; this is the ultimate benefit and the primary goal, and would most likely lead to “national liberation” (Musolff, 2021). Anything less than national liberation would fail to restore the freedoms relinquished to the delegitimized EU. The metaphoric frame of freedom, explicitly stated to the British the most important drawback of being within the enclosure of the EU. The UK and its people were not free to determine their own future, as the EU, acting as a prison guard, exerted excessive power over them. The metaphoric frame of freedom is indirectly suggested by the frames of enclosure, departure, and control, as all three contributed to the allegory of unjust entrapment. Freedom was the ultimate goal for both the politicians and the people of the UK. By regaining their freedom, British citizens would be able to make their own decisions, shape their own affairs in the world and create their own future according to their own priorities they would therefore be free of external control, whether originating from a ruler, a prison guard or the European Union. The metaphoric frame of freedom completes the most frequent metaphoric frames in the data examined that build the unjust entrapment allegory in the online discourse of pro-Brexit politicians. It constitutes the cornerstone in the delegitimization of the EU, as it connects all the other metaphoric frames by making explicit the main drawback of being located in the enclosed space of the EU.

Most frequent metaphoric frames by account

| Metaphors | @Nigel_Farage | @BorisJohnson | @pritipatel | Total |

| Departure | 47 | 2 | 9 | 58 |

| Control | 29 | 5 | 6 | 40 |

| Freedom | 12 | 0 | 3 | 15 |

| Enclosure | 10 | 1 | 2 | 13 |

The allegory of unjust entrapment, as exemplified in the metaphors present in the tweets, succeeds in delegitimizing the EU as an enclosed space that had an overtly restrictive power over those located inside, to such an extent that they had lost not only their freedom to act as independent entities but also their ability to think for themselves and make their own decisions. The only way to become volitional individuals to leave this confining and illegitimate place, take control of their lives, and reclaim their own freedom. Research question 3 (RQ3) is answered by the allegory of the unjust entrapment, which was constructed on the metaphoric frames of enclosure, departure, control, and freedom. The delegitimization of the EU was achieved by making use of these frames, which depicted the union as a prison or a guard; by leaving, the British people could eventually escape and regain their long-lost freedom.

9 Discussion and Conclusions

This paper systematically examined the use of metaphoric language among Brexit political proponents on Twitter and demonstrated how the metaphoric delegitimization of the EU prior to the Brexit referendum developed through the use of metaphors that build the allegory of unjust entrapment in the tweets published by the politicians. Regarding the extent of metaphor use on Twitter (RQ1), metaphor as an important component of political discourse (Thomson, 1996; Musolff, 2004) was also shown to play an important role in political discourse on social media, as more than 50 % of the tweets examined included metaphoric language related to the Brexit/EU. The analysis revealed in total 26 metaphoric frames based on the source domains of the metaphoric items in the tweets examined. With respect to research question 2 (RQ2) concering the most frequent metaphoric frames in the data, the analysis revealed that the most frequent were enclosure, departure, control, and freedom. These most frequent metaphoric frames built the allegory of the unjust entrapment in the online discourse of the politicians by constructing their tweets on concepts of constraint and release from constraint. Regarding research question 3, (RQ3), which focused on how the EU was metaphorically delegitimized, the allegory of unjust entrapment (Charteris-Black, 2019) is proposed. This allegory was shown to be the basic means through which the politicians under study delegitimized the EU in relation to Brexit. The EU was presented as a place of confinement that exercised an extremely negative influence over the UK and its people. Within the EU, the UK was a mere prisoner or a captive in a prison cell, with both its present and future defined by a prison guard or captor, epitomized by the EU. By using metaphors that built the allegory of the unjust entrapment, the politicians managed to delegitimize the EU as a whole, and more importantly, they delegitimized its relationship with the UK. As in the case of the unjust entrapment, only one solution was available to the British and the UK, namely, to free themselves and their country from the prison of the EU. Freedom, as the ultimate goal in the allegory of the unjust entrapment, was also the most important and the only goal of the British people that could be achieved by supporting the exit of the UK from the EU in the referendum. With support for Brexit as the focus of their political discourse on Twitter, the allegory of the unjust entrapment was the best foundation for the politicians’ pre-referendum campaign, as it managed to show the voters metaphorically that, apart from being politically and economically constrained by the EU, they were also captives in an enclosure that restrictively defined their own life as a whole.

Clearly, metaphor plays a crucial role in framing the debate (Lakoff, 1991; 2004). Metaphors used by the politicians, either in isolation or in groups of two or more in their tweets, activated the allegory of unjust entrapment in the conceptual world of the politicians’ audiences and voters. By indicating enclosure, departure, control, or freedom through the use of linguistic metaphors, the politicians managed to undermine faith in the EU’s reliability or trustworthiness as a partner. Significantly, one of the two alternatives on the Brexit referendum ballot paper, i. e., “leave” (vs stay), could reenact the allegory of unjust entrapment for the voters through the metaphoric frame of departure it evoked, potentially influencing decision-making at a critical moment. Ultimately, the four metaphoric frames that built the allegory of unjust entrapment in Twitter discourse transformed the opportunity of being members of the “EU family” (Musolff, 2017) into a once-in-a-life opportunity to escape.

Overall, metaphor played an important role in the delegimization of the EU in political discourse on Twitter before the Brexit referendum. Through metaphor, the political leaders in question managed to discredit the EU in terms of its political, economic, and social relationship with the UK. Various EU procedures were metaphorically framed, and probably conceptualized by the audiences, as physical boundaries that restricted the freedom of the British people to act or think independently. The only solution to the problematic interaction with a delegitimized authority was to stop cooperating with it; this could be easily achieved, in metaphoric terms, by simply walking away from a faulty enclosure, a captor or a ruler.

The results of this study underscore the importance of metaphor in political discourse on social media, as exemplified through the metaphoric frames that created the allegory of unjust entrapment. Given the challenges the EU is currently facing due to various peripheral crises and domestic political voices that doubt its existence (Bortun, 2022; Vasilopoulou, 2023), it is important for researchers and stakeholders to monitor the use and further development of the metaphors building this allegory in political discourse, particulary on social media, which serve as a space for public debate, a modern-day Athenian agora.

References

Angouri, Jo., Salomi Boukala and Dimitra Dimitrakopoulou. 2018. From Grexit to Brexit and back: Mediatisation of economy and the politics of fear in the Twitter discourses of the Prime Ministers of Greece and the UK. Language@Internet 16. (urn:nbn:de:0009-7–47769) https://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2018si/angouri. Accessed 15 October 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

Arcimaviciene, Liudmila, & Baglama H., Sercan. 2018. Migration, Metaphor and Myth in Media Representations: The Ideological Dichotomy of “Them” and “Us”. Sage Open, 8(2). 1–13.Suche in Google Scholar

Aristotle. (1457a-1458a). Ποιητική. Retrieved from www.greek-language.gr. 7/10/2017. http://www.greeklanguage.gr/digitalResources/ancient_greek/library/browse.html?text_id=76&page=17Suche in Google Scholar

Baldi, Benedetta. 2020. Persuasion we live by: symbols, metaphors and lingustic strategies. Qulso 6, 337–382.Suche in Google Scholar

Bortun, Vladimir. 2022. Plan B for Europe: The Birth of ‘Disobedient Euroscepticism’? Journal of Common Market Studies 60(5). 1416–1431.Suche in Google Scholar

Buckledee, Steve. 2018. The language of Brexit: How Britain talked its way out of the European Union. London: Bloomsbury.Suche in Google Scholar

Brugman, C., Britta, Christian Burgers & Barbara Vis. 2019. Metaphorical framing in political discourse through words vs. concepts: a meta-analysis. Language and Cognition 11. 41–65.Suche in Google Scholar

Burgers, Christian, Elly A., Konijn & Gerard Steen Jr. 2016. Figurative Framing: Shaping Public Discourse Through Metaphor, Hyperbole, and Irony. Communication Theory 26. 410–430.Suche in Google Scholar

Cammaerts, Bart. 2012. The strategic use of metaphors by political and media elites: the 2007–11 Belgian constitutional crisis. International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics 8(2/3). 229–249. Suche in Google Scholar

Cassese, C., Erin. 2018. Monster metaphors in media coverage of the 2016 U. S. presidential contest. Politics, Groups, and Identities. 1–13.Suche in Google Scholar

Charteris-Black, Johnathan. 2006. Britain as a container: Immigration metaphors in the 2005 election campaign. Discourse & Society 17(5). 563–581.Suche in Google Scholar

Charteris-Black, Johnathan. 2019. Metaphors of Brexit: No Cherries on the Cake? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Suche in Google Scholar

Chilton, Paul. 2006. Analysing Political Discourse: Theory and Practice. London & New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Chisango, Tadios & Calvin Gwandure. 2011. Delegitimisation of Disliked Political Organisations Through Biased Language and Acronyming. Journal of Psychology in Africa 21(3). 455–458. Suche in Google Scholar

Cibulskienė, Jurga. 2012. The development of the journey metaphor in political discourse: Time-specific changes. Metaphor and the Social World 2(2). 131–153.Suche in Google Scholar

Cohen, S., Matthew & Chuck D., Freilich. 2018. War by other means: the delegitimisation campaign against Israel. Israel Affairs 24(1). 1–25.Suche in Google Scholar

Daniel, William T., and Lukas Obholzer. (2020). Reaching out to the voter? Campaigning on Twitter during the 2019 European Elections. Research and Politics, 7(2), 1–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Đurović, Tatjana & Nadežda Silaški. 2018. The end of a long and fraught marriage: Metaphorical images structuring the Brexit discourse. Metaphor and the Social World 8(1). 25–39.Suche in Google Scholar

Đurović, Tatjana & Nadežda Silaški. 2019. The JOURNEY metaphor in Brexit-related political cartoons. Discourse, Context & Media 31. 1–10.Suche in Google Scholar

Fazekas, Zoltán, S. A. Opa, Hermann Schmitt, Pablo Barbera, and Yannis Theocharis. 2021. Elite-public interaction on twitter: EU issue expansion in the campaign. European Journal of Political Research, 60(2), 376–396.Suche in Google Scholar

Filardo-Llamas, Laura, & Cristina Perales-García. 2022. Widening the North/South Divide? Representations of the role of the EU during the Covid-19 crisis in Spanish media: A case study. In Franco Zappettini & Samuel Bennett (eds.), (De)legitimising EUrope in times of crisis. [Special issue]. Journal of Language and Politics 21(2). 233–254.Suche in Google Scholar

Forchtner, Bernhard & Özgür Özvatan. 2022. De/legitimising EUrope through the performance of crises: The far-right Alternative for Germany on “climate hysteria” and corona hysteria”. In Franco Zappettini & Samuel Bennett (eds.), (De)legitimising EUrope in times of crisis. [Special issue]. Journal of Language and Politics 21(2). 208–232.Suche in Google Scholar

Gaber, Ivor, & Caroline Fisher. 2022. Strategic Lying: The Case of Brexit and the 2019 U. K. Election. The International Journal of Press/Politics 27(2). 460–477.Suche in Google Scholar

Hänska-Ahy, Max & Stefan Bauchowitz. 2017. Tweeting for Brexit: how social media influenced the referendum. In John Mair, Clark Tor, Neil Fowler, Snody Raymond & Richard Tait (eds.), Brexit, Trump and the Media, 31–35. Edmunds: Abramis Academic Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Hellin-Garcia, Maria Jose. 2013. Legitimization and delegitimization strategies on terrorism: A corpus-based analysis of building metaphor. Pragmatics. 301–330.Suche in Google Scholar

Jessop, Bob. 2017. The organic crisis of the British state: Putting Brexit in its place. Globalizations 14(1). 133–141.Suche in Google Scholar

Khatua, Apalak & Aparup Khatua. 2016. Leave or Remain? Deciphering Brexit Deliberations on Twitter. IEEE 16th International Conference on Data Mining Workshops. 428–433.Suche in Google Scholar

Koller, Veronika, Susanne Kopf & Marlene Miglbauer. 2019. Discourses of Brexit. London & New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Kövecses, Zoltán. 2002. Metaphor: A practical introduction. Oxford University Press. New York, NY.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George. 1991. Metaphor and War: The Metaphor System Used to Justify War in the Gulf. Retrieved from: < http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/sixties/HTML_docs/Texts/ Scholarly/Lakoff_Gulf_Metaphor_1.html> 8/04/2010.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George. 2004. Don’t think of an elephant. Vermont: Chelsea Green.Suche in Google Scholar

Lucchesi, Dario. 2020. The refugee crisis and the delegitimisation of the EU: a critical discourse analysis of newspapers’ and users’ narratives in Italian Facebook pages. Culture, Practice & Europeanization 5(1). 34-51Suche in Google Scholar

Marwick, Alice. 2013. Ethnographic and Qualitative Research on Twitter. In Katrin, Weller, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt, Cornelius Puschmann, (eds), Twitter and Society. New York: 2 Peter Lang, 109–122.Suche in Google Scholar

Mio, S., Jeffery. 1997. Metaphor and politics. Metaphor and Symbol 12(2). 113–133.Suche in Google Scholar

Musolff, Andreas. 2004. Metaphor and Political Discourse: Analogical Reasoning in Debates about Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan.Suche in Google Scholar

Musolff, Andreas. 2006. Metaphor scenarios in public discourse. Metaphor and Symbol 21(1). 23–38. Suche in Google Scholar

Musolff, Andreas. 2017. Truths, lies and figurative scenarios: Metaphors at the heart of Brexit. Journal of Language and Politics 16(5). 641-657Suche in Google Scholar

Musolff, Andreas. 2019. Brexit as ‘having your cake and eating it’: The discourse career of a proverb. In Veronika, Koller, Susanne, Kopf & Marlene, Miglbauer (eds.),Discourses of Brexit. 208–221. New York: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Musolff, Andreas. 2021. Hyperbole and emotionalisation – escalation of pragmatic effects of metaphor and proverb in the Brexit debate. Russian Journal of Linguistics 25(3). 628–644.Suche in Google Scholar

O’Brien, V., Gerald. 2003. Indigestible food, conquering hordes, and waste materials: Metaphors of immigrants and the early immigration restriction debate in the United States. Metaphor and Symbol 18(1). 33–47.Suche in Google Scholar

Radden, Gündeter & Dirven René. 2007. Cognitive English Grammar. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing CompanySuche in Google Scholar

Rodet, Pauline. 2020. Metaphor as the Distorting Mirror of Brexit: A Corpus-Based Analysis of Metaphors and Manipulation in the Brexit Debate. ELAD-SILDA n°5 juillet.Suche in Google Scholar

Rosa, M., Jorge & Cristian Jiménez Ruiz. 2020. Reason vs. emotion in the Brexit campaign: How key political actors and their followers used Twitter. First Monday 25(3). https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/9601/9402. Accessed 15 October 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

Ross, Karen, & Tobias Burger. 2014. Face to face(book): Social media, political campaigning and the unbearable lightness of being there. Political Science 66(1). 46–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Ruppenhofer, Josef, Michael Ellsworth, Miriam R. L., Petruck, Christopher R., Johnson, Collin F., Baker, & Jan Scheffczyk. 2016. FrameNet II: Extended Theory and Practice. The Berkley FrameNet Project.Suche in Google Scholar

Schlesinger, Mark, & Richard R., Lau. 2000. The meaning and measure of policy metaphors. The AmericanPolitical Science Review 94(3). 611–626.Suche in Google Scholar

Serafis, Dimitris, Dimitris E., Kitis & Stavros Assimakopoulos. Sailing to Ithaka: The transmutation of Greek left-populism in discourses about the European Union. In Franco, Zappettini & Samuel, Bennett (eds.), (De)legitimising EUrope in times of crisis. [Special issue]. Journal of Language and Politics 21(2). 344–369.Suche in Google Scholar

Spears, R., Christian Leach, Martijn van Zomeren, Andrei Ispas, Jennifer Sweetman, & Nicole Tausch. (2011). Intergroup emotions: More than the sum of the parts. Emotion Regulation and Wellbeing, 2, 121–145.Suche in Google Scholar

Steen, Gerard J., Aletta G. Dorst, Berenike, Herrmann, Anna A. Kaal, Tina, Krennmayr, & Trijntje, Pasma,. 2010. A method for linguistic metaphor identification: From MIP to MIPVU. John Benjamins Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Thibodeau, Paul, Rose Hendricks & Lera Boroditsky. 2017. How linguistic metaphor scaffolds reasoning. Trends in cognitive science 21(11). 852–863.Suche in Google Scholar

Thompson, Seth. 1996. Politics without Metaphors is Like a Fish without Water. In Jeffery, Mio, S. & Albert, Katz, N. (eds.), Metaphor: Implications and Applications, 185–201. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Suche in Google Scholar

Usherwood, Simon, & Katharine Wright. 2017. Sticks and stones: Comparing Twitter campaigning strategies in the European Union referendum. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19(2). 371–388. Suche in Google Scholar

van Leeuwen, Theo. 2007. Legitimation in discourse and communication. Discourse & Communication 1(1). 91–112. Suche in Google Scholar

Vasilopoulou, Sofia & Liisa Tavling. 2023. Euroscepticism as a syndrome of stagnation? Regional inequality and trust in the EU. Journal of European Public Policy.Suche in Google Scholar

Vavrus, D., Mary. 2000. From Women of the Year to “Soccer Moms”: The Case of the Incredible Shrinking Women. Political Communication 17(2). 193–213. Suche in Google Scholar

Zappavigna, Michele. 2015. Searchable talk: the linguistic functions of hashtags. Social Semiotics, DOI: 10.1080/10350330.2014.996948Suche in Google Scholar

Zappettini, Franco. 2022. Taking the left way out of Europe: Labour party’s strategic, ideological and ambivalent de/legitimation of Brexit. In Franco, Zappettini & Samuel, Bennett (eds.),(De)legitimising EUrope in times of crisis. [Special issue]. Journal of Language and Politics 21(2). 320–343Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.