Abstract

The British Museum currently houses an Etruscan mirror portraying a depiction of two women engaged in an embrace and sharing a kiss. Despite previous endeavors to elucidate the symbolic gesture, the profound implications behind the embrace remain shrouded in ambiguity. This article argues that the mirror, while adorned with a veneer of mythology, conceals a narrative that holds pivotal significance in a woman’s life, specifically, the moment of a bride bidding farewell to her mother. Under this interpretive framework, the gesture takes on the role of a salutation, a conjecture fortified by parallels drawn from analogous scenes in different artistic mediums.

1 Introduction

An Etruscan mirror in the collection of the British Museum depicts on its reverse a scene in which two female figures are shown embracing and kissing (Figures 1–3).[1] This paper investigates the potential underlying meanings of the scene and assesses the extent to which its iconography can help to contextualize the mirror’s production and use. A fresh semantic interpretation of the scene will be presented, taking into full account the interaction of the figures. The aim of this analysis is to bring coherence to previous interpretations of the scene, dismissing less well-substantiated ideas and adding more significance to some other readings. The analysis will place particular emphasis on the semantics of gestures, a methodological perspective from which gestures, like the figures involved, bear significant social implications.[2]

Etruscan mirror depicting Alpnu, Thanr, Thalana and Zipna, bronze, late 5th century-early 4th century B.C.E. London, The British Museum acc. no. 1867,1023.1. (Courtesy of © The Trustees of the British Museum).

Etruscan mirror depicting Alpnu, Thanr, Thalana and Zipna (reflective side), bronze, late 5th century – early 4th century B.C.E. London, The British Museum acc. no. 1867,1023.1. (Courtesy of © The Trustees of the British Museum).

Etruscan mirror depicting Alpnu, Thanr, Thalana and Zipna, bronze, late 5th century-early 4th century B.C.E. London, The British Museum acc. no. 1867,1023.1.(Line drawing by author).

The provenance of the mirror is uncertain. It was acquired by the British Museum in 1867 via the auctioneers Rollin & Feuardent.[3] Eduard Gerhard first recorded the mirror in 1864 in the Archäologischer Anzeiger [4] and catalogued it in the fourth volume of his monumental Etruskische Spiegel.[5]

The mirror falls under the category of circular tanged mirrors with extension.[6] The disc is flat with a slight curvature. The outer rim once featured beaded grooves, but these have largely degraded over time. The ornamentation on the reflective side has also worn away considerably, possibly due to thumb wear, but at the base of the disc and on the extension one can discern a palmette flanked by spiral motifs. The reverse has a central scene portraying two female figures, their names inscribed as Thanr and Alpnu, locked in an embrace and kissing each other. Adjacent to them, two female companions, Thalana and Zipna, are seated on rocks. Thalana holds an egg in her right hand and touches Thanr’s shoulder with her left. Zipna, opposite her, holds a mirror and what appears to be a larger egg. All the figures are depicted in full dress and adorned with jewelry.[7] The exergue features alternating triangles filled with diagonal hatching, while the border of the disc is decorated with two undulating ivy stems, originating from a palmette with seven lobes located on the extension. The frame decoration is interrupted at the top of the disc by the heads of the two central figures. This suggests that the figural scene and the frame were conceived as strongly interrelated, presumably with the figures being incised prior to the frame decoration. The lines throughout the composition maintain a consistent quality, displaying uniformity in both width and depth. All faces are shown in profile, with a straight line linking the forehead to nose, creating a typical classical profile. The eyes, also portrayed in profile, are meticulously rendered, while the mouths are indicated by small downward-curving lines. The design achieves a fair degree of three-dimensionality.

2 Chronology and Workshop

The mirror is generally attributed to the latter part of the fourth century BCE.[8] This assumption ultimately rests on comparisons with other mirrors, the dating of which usually lacks contextual verification. Nonetheless, a more recent dating put forward by Adriano Maggiani suggests that the origin of this mirror could be traced to Veii, dating from the late second half of the fifth century BCE to the early fourth century BCE.[9] This proposal, grounded in paleographic analysis, gains further support from the style and theme of the scene depicted on the reverse of the mirror, which, as we will explore in further detail below, exhibit resemblances to Attic imagery of the final decades of the fifth century BCE.[10] For these reasons, the chronological frame suggested by Maggiani seems to rely on a more solid basis and therefore to be preferred.

Regarding the provenience of the artifact, determining within Etruria the exact place of its production, usage, and eventual discovery poses challenges. Furthermore, these locations may or may not be the same, as mirrors were objects of trade and artisans too might have moved from one city to another.[11] The pursuit of comparanda fails to furnish irrefutable evidence; the three mirrors that are most similar to this one in terms of configuration and the arrangement of ornamentation, specifically a mirror in Hannover, along with two others presently housed in Basel (Figure 4) and Berlin (Figure 5), share the same undetermined provenience.[12] It is noteworthy, however, that the latter two mirrors also exhibit identical scenes in their decoration, implying a potential correlation between their shapes (and consequently, workshop) and the choices of iconography. As elucidated in earlier scholarly discourse, there is a reasonable likelihood that these three mirrors were crafted by the same workshop.[13]

Etruscan mirror depicting Thalna, Thanr, Achuvizr and Turan, bronze, late 5th century-early 4th century B.C.E. Basel, private collection. (Line drawing by author after CSE Schweitz 1, 17).

Etruscan mirror depicting Alpanu, Achuvizr, Thanr and Zipanu, bronze, late 5th century-early 4th century B.C.E. Berlin, Antikensammlung der Staatlichen Museen, inv. Fr 155. (After ES 324).

3 The Iconography: Meanings through Images

The main scene on the mirror is a subject of prime interest. As mentioned above, this scene finds itself replicated on at least two other mirrors, each instance marked by variations in attributes and names of the protagonists.[14] The mirror now in Berlin reveals a comparable scene, albeit executed in a sketchier style. Positioned in proximity, two female figures named Alpanu and Achuvizr are depicted, their posture suggestive of an impending embrace. Flanking them are two attendants: Zipanu, who holds a mirror, and Thanr, who cradles a bird. By contrast, the mirror in Basel introduces a further variation in the characters depicted. Here, the embrace is performed by Thanr and Thalna, while the goddess Turan, accompanied by a swan, and Achuvizr observe from a seated position.

Despite the fluidity in the nomenclature associated with the characters in these mirrors, it is reasonable to infer that the fundamental gesture of embrace and its significance remain consistent. For this reason, a more in-depth inquiry into this aspect offers the potential for unveiling illuminating insights into the Etruscan realm of imagery, gestures, and their underlying meanings. What is important is that a gesture rarely encountered in classical visual representations emerges with noteworthy recurrence within the confines of Etruscan mirror production. The repetition implies that this scene was perceived as particularly suited for this genre of artifact.

Unlocking the message underlying the gesture could offer an avenue for further understanding the interplay of visual representation and social values in Etruria.[15]

4 The Iconography: State of the Art

The interpretation of the embracing female figures as Demeter and Persephone, proposed by Gerhard with respect to both the British Museum and Berlin mirrors, was the first to be suggested.[16] According to this interpretation the scene would have been a depiction of the reunification between the two goddesses following Persephone’s return from the Underworld. However, this theory fails to explain the recurrence of the identical schema featuring different characters on different mirrors. Moreover, the association of figures depicted with Demeter and Persephone remains tenuous. In this regard it is worth noting that the Basel mirror, which brings a third variation in the motif, at the time when Gerhard was writing had not yet entered the debate yet.

Other early scholars attempted to address this issue by proposing etymological links between the Etruscan names mentioned on the mirrors and those of the Greek goddesses, yet none solution proved entirely conclusive. A more allegorical interpretation was presented by E. Cavalieri, writing under the pen name Ulisse. This approach viewed each Etruscan character as a personification or an allegorical representation with a recognizable Greek or Roman equivalent.[17] While the rigidity of this one-to-one correspondence has lost favor, its allure persists in its endeavor to offer a broader perspective on the potential functions of these figures across various iconographic examples.

In a more recent contribution by Nancy de Grummond, the allegorical interpretation gains renewed strength.[18] The characters depicted in the three mirrors might personify prosperity and good fortune, thereby imbuing the object’s owner with these desirable attributes. Analogous scenes, featuring personifications, find parallels in Greek vases attributed to artists like the Eretria Painter and the Meidias Painter.[19] This inclination towards wishful symbolism could have made these scenes suitable for mirrors, which functioned also as bridal gifts.

While this allegorical interpretation could identify the overarching message conveyed by these figures, pivotal queries remain unanswered. The nuanced implications of the specific gesture of the embrace and the kiss exchanged between female figures, and the recurrence of this motif on Etruscan mirrors, continue to be elusive. Further exploration is necessary to uncover the profound motivations and cultural subtleties underpinning these enigmatic scenes, inviting a deeper comprehension of the intricate interplay of art, symbolism, and societal values in Etruria. The quest to elucidate the precise meaning embedded in the embrace and kiss in this context becomes even more imperative, particularly considering that in Greek vase paintings, used as comparanda for the role of female personifications, these figures are featured in an array of attitudes and gestures, with no strict preference for one over the other. This sharply contrasts with the situation observed on the three Etruscan mirrors, where a distinctively poignant gesture seems to have been deliberately selected.

In addition to the interpretation discussed so far, two alternative perspectives have focused on the act of embrace itself. In the CSE entry on the Basel mirror, Ines Jucker introduced the notion that the depiction of the two embracing figures might signify homoerotic love, drawing a parallel with images of nude women at baths engaged in dances with arms linked around partners’ necks.[20] However, it must be pointed out that these bathing scenes are more appropriately read within the context of the ritual of bathing and adornment, rather than as explicit indicators of lesbian relationships. Moreover, depictions of lesbian love are few even in the Greek world, where some of them are nonetheless attested.[21] When the content is not explicit, it is often difficult to differentiate between the “homosocial” and the “homoerotic” spheres, since the boundary between the two spheres can be thin.[22] It is difficult to translate this interpretation within the Etruscan world, where indisputable visual parallels are lacking. Most importantly, looking carefully at the scenes on the three mirrors with the embrace schema, there is nothing to confirm a sensual interpretation of any of them. Neither nudity nor intimate touching are displayed, as we might otherwise expect in the case of an erotic encounter.

Giovanna Bagnasco Gianni proposed an alternative reading, suggesting that the embracing couple symbolizes a visual representation of the dual nature of a person, with each half representing different facets or virtues of the same individual.[23] Although intriguing, this concept leans on philosophical concepts that may not have imbued the Etruscan world.

Despite these endeavors, the embrace’s implications continue to elude a full and convincing explanation. The best approach appears to involve scrutiny of the broader scope of surviving Etruscan imagery in search of similar acts of embrace and kissing between individuals of the same sex. By analyzing the contexts in which these occurrences manifest, and by deciphering the underlying messages, it may be possible to glean insights into the significance of this gesture within the Etruscan visual lexicon.

5 The Figures Involved

A succinct overview of key aspects relating to the characters involved and their respective domains of influence seems worth undertaking. This should facilitate the reconstruction of the contextual backdrop before which this gesture unfolds, hopefully elucidating its specific and contextual significance. The pertinent figures encompass Thanr, Thalana, Zipna, and Alpnu, as inscribed on the British Museum mirror. In addition, Achuvizr, featured in mirrors from Berlin and Basel, and Turan, present solely in the Basel mirror, contribute to this assembly. Turan is known as the goddess of erotic love; as we have seen above, the bottom line of the scientific debate is that the others are divine figures personifying abstract and auspicious concepts.

These figures are depicted on mirrors in scenes relevant to the realm of femininity such as the adornment of the bride and childbirth.[24] Etruscan dedicatory inscriptions further bear evidence of the divine entities Achuvizr, Alpan and Thanr.[25] Among these, Thanr merits special attention in our analysis, since she is consistently present across all three mirrors. References to Thanr are attested in ritual texts with funerary implications, such as the lead plaque from Magliano and the Capua Tile, along with dedicatory inscriptions.[26] Notably, a votive statuette in the British Museum aligns Thanr with Selvans, a deity in charge of protecting borders.[27] These pieces of evidence suggest that Thanr, too, may have been a goddess who prevailed over liminal moments in a person’s life, notably birth and death, but I suggest that other occasions of transition deserve to be taken into consideration. This prerogative of Thanr presiding over pivotal life junctures may provide us with clues for the overall interpretation of the embrace and kiss.[28]

Ultimately, Thanr and Turan emerge as the two entities whose domains and powers are most distinctly discernible in the present state of research. Their presence intimates a plausible connection between the scene depicted and pivotal transitional phases in human existence.

This thematic thread extends to an examination of the attributes wielded by these figures, ranging from eggs, mirrors, and birds to buds and globular fruits reminiscent of pomegranates or poppy heads.[29] While many attributes defy definite interpretation, a holistic consideration hints at a backdrop of the female milieu. Turan’s dominion over love, beauty, and fertility is palpable, eclipsing a purported allusion to Persephone. It is worth noting that mirrors, as attributes, may signify both the ritual of embellishment and, intriguingly, the reflective potential for divination – especially within matrimonial contexts.[30] Furthermore, the Basel mirror portrays Turan bearing branches, possibly myrtle (linked with fertility), and accompanied by a swan, both emblematic of the goddess.[31] This aligns with her character traits and spheres of influence.

6 A Multifaceted Gesture

The identification of the embrace between women as a representation of mutual love, suggested for the Basel mirror by I. Jucker, is rooted in the broader interpretation of embrace and kiss scenes viewed solely through an erotic lens. Notably Giovannangelo Camporeale suggested that embracing imagery in Etruscan art consistently portrayed lovers.[32] The fact that sometimes a mother and son pair is depicted – such as Letun/Leto and Aplu/Apollo[33] or Thetis and Achle/Achilles[34] – is explained by the assumption that the Etruscans may not have fully comprehended or cared for the familial relationships represented in Greek mythology.[35] However, the diversity of emotions conveyed through various examples of the embrace gesture is apparent when one scrutinizes the images, for instance, sensuality in the case of lovers,[36] maternal tenderness in mother-son portrayals, and the gravity of the moment in our collection of embraces between two female figures. Even with comparable schemata, differing degrees of affection can be conveyed.[37] This result is much more eloquent when considered against the backdrop of the technical difficulty of incising bronze, which makes it difficult to achieve such subtle differentiation in emotions. It is indeed evident that this gesture is not exclusively interpretable as erotic. In this respect a very recent contribution by Larissa Bonfante is relevant. It opens up the possibility of alternative interpretations of scenes traditionally understood in a sexual context, such as the two men on a couch depicted in the Tomb of the Infernal Chariot, one of whom makes an affectionate gesture towards the other while touching his hand.[38] In Bonfante’s interpretation the two of them might be a father and son reunited in the afterlife. For the group of mirrors depicting the embrace between two female figures, Bonfante suggests “a bond of romantic love, affection between two women joined by family ties, or a relationship consecrated by ritual.”[39]

Returning to our group of mirrors, one must question the nature of the bond between the figures and the circumstances prompting the gesture. Revisiting an interpretation suggested by Eva Fiesel in 1934 under the lemma “Thanr” in the Realencyclopädie, and left largely unexplored since then, we find an appealing explanation.[40] According to Fiesel, the scene depicts a moment pivotal in any woman’s life: the bride’s parting from her mother or, conversely, her arrival and reception in the groom’s home. This perspective maintains parallels with the earlier attempt to identify Demeter and Persephone in this pairing, as it centers on a mother-daughter relationship. Yet it avoids the pitfalls of untenable etymological conjectures and instead furnishes a more contextually grounded interpretation. Remarkably, the semantic potential of this interpretation has been largely overlooked.

An entry in the LIMC Supplementum by Cornelia Weber-Lehmann partially reintroduces the concept.[41] Within the overaching idea of the embrace as a salutation gesture, Weber-Lehmann is inclined to interpret the occasion as a meeting, based on drapery movements and the orientation of the figures’ feet. However, this observation loses strength as one observes that the same foot positioning is displayed in the Admetus and Alcestis krater (Figure 7), where clearly a departure is depicted. Thus, the fact that two individuals are approaching for an embrace and kiss does not necessarily negate the possibility of impending separation.

Ninety years after Fiesel’s suggestion, her idea is worth proper reconsideration. Iconographic parallels substantiating it can indeed be found in diverse media, including wall paintings, vases, and sarcophagi. These point to a very plausible contextual interpretation of the scene, considering the possibility of the mirror as a gift from mother to daughter to mark a marriage, or gift from daughter to mother, or vice versa, at the death of one of them.

7 Tales of Separation (and Some Meetings)

Exploring the notion that embracing and kissing can signify salutation in specific contexts reveals instances that lend credence to this hypothesis. Explicit examples of this gesture occurring in the context of farewells can be found in funerary imagery. Beyond the embraces of affection shared between married couples on sarcophagi lids and urns, there are instances that resist such straightforward interpretation. An illustration on the right-hand wall of the Hescana Tomb in Porano serves as a notable case, with two men embracing and kissing each other (Figure 6). Given that the tomb’s theme centers on the journey to the Underworld of the Hescana family’s departed members, the embrace here likely signifies a farewell.[42]

Porano (Orvieto), Hescana Tomb, detail from the right wall, 350–325 B.C.E. (courtesy MiC – Soprintendenza ABAP dell’Umbria, any further reproduction prohibited).

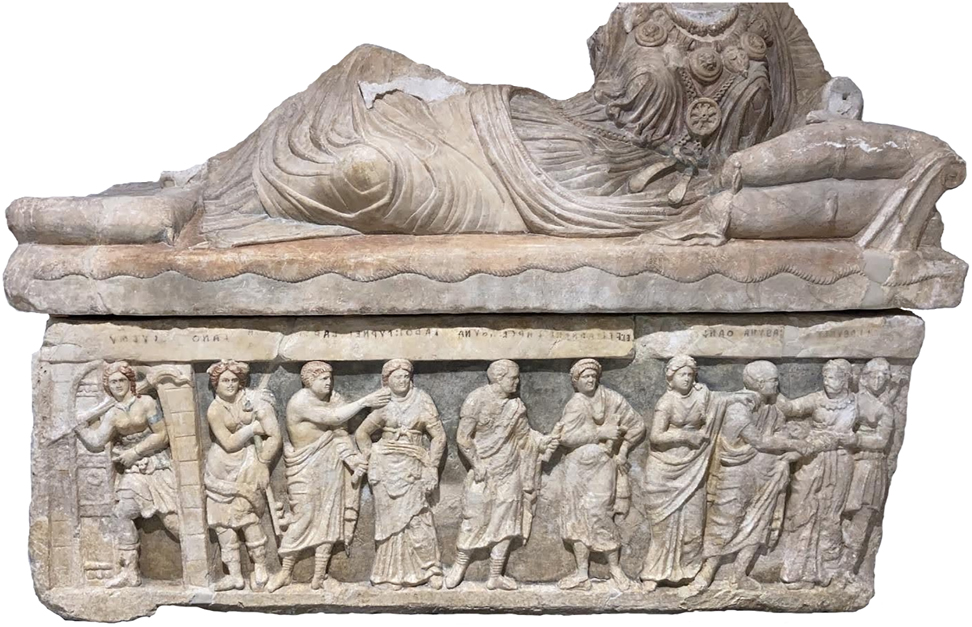

The iconic volute krater featuring Alcestis and Admetus provides another interesting case study (Figure 7).[43] Even though the couple is married, the focus of the scene does not depend on eroticism; rather, it highlights the tragedy of parting, as the looming demons of death cast their shadow over Alcestis. A purely sensual interpretation would be simplistic given the vivid theme of separation. Expanding the gamut of examples, while sarcophagi and urns often signify the parting of the deceased from loved ones – or, conversely, their reunion in the afterlife – through clasped hands, there are instances where this gesture evolves into or suggests an inclination toward an embrace. The sarcophagus of Hasti Afunei exemplifies this, featuring a relief on its front depicting Hasti reaching her arms out to her father Larth Afuna in an embracing gesture (Figure 8).[44] The significance of embracing in salutation is evident in Ramtha Vishnai’s sarcophagus, where the center of the frontal scene depicts the reunion of spouses Ramtha Vishnai and Arnth Tetnies in the afterlife.[45] Even if the context in the latter cases leans more towards reunion than farewell, the act of seeking physical contact remains prominent.

Etruscan volute krater with Alcsti and Atmite, red-figured pottery, from Vulci, 350–340 B.C.E., attributed to the Alcesti Group, Paris, BnF – Cabinet des Médailles inv. De Ridder.918 (courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France).

Hasti Afunei’s sarcophagus, chalky alabaster, from Chiusi, 225–200 B.C.E., Palermo, Museo Archeologico Salinas inv. n. 8468 (courtesy Museo Archeologico Regionale ‘Antonio Salinas’ di Palermo; photo by G. Adornato).

A similar gesture imbued with tenderness between two women, again in a funerary context, emerges on the chest relief of an urn from Volterra (Figure 9b). Here, the face of a seated deceased woman in a carpentum is caressed by another woman standing outside the carriage, stretching towards the departing figure.[46] While a full embrace is hindered by the circumstances of the scene, the gesture of physical tenderness underscores the salutation.

(a) Etruscan mirror depicting Elina, Turan and Menle, bronze, late 5th century-early 4th century B.C.E. (after ES 197). (b) Etruscan cinerary urn, from Volterra, Museo Guarnacci inv. n. 149 (after Körte 1916, LXXXIII.9).

From these examples it is evident that among the potential connotations of the embrace and kiss, salutations – whether farewells or greetings – emerge.[47] It must be noted that this gesture is also attested in the Greek world, where it is part of Rhodian funerary imagery from the fifth to the second century BCE.[48] Funerary reliefs from Rhodes feature touching examples of embraces between couples and between two women conveying intimacy but especially grief.

This interpretation, manifest within the funerary domain in a wealth of visual examples, can be extrapolated profitably to other social contexts. Similar meanings for these gestures are attested in other ancient societies as well. For instance, Herodotus notes that Persians kissed upon meeting,[49] and in the Roman Imperial age, clients kissed their patrons as a sign of respect and loyalty.[50] This underscores the idea that these gestures in ancient society could carry varied meanings depending on the identity of the participants.[51] When interpreting such scenes, contemporary Western perceptions (very recent indeed), often leaning towards eroticism – especially for mouth-to-mouth kissing – should be set aside. Substantial evidence suggests that in Etruscan society these gestures could convey diverse meanings, including that of salutation.

8 Female Figures in Action

Given that the mirror in question features female figures as the sole protagonists, we might want to examine the social events where groups of female figures take center stage. Let us now set aside the funerary contexts which we have used to explore the possibility that the embrace symbolizes a message of salutation. Notably, instances of physical tenderness between female figures often occur when one of them is on the verge of uniting with a man, signaling her imminent departure from the circle of female companions. These moments typically precede marriage or an amorous encounter between a young woman and a man. During such occasions, other female figures gather around the bride-to-be, adorning her, offering reassurance, and bidding her farewell. In real-life scenarios, this often unfolded on the wedding day when a female companion accompanied the bride in the nuptial procession.[52] An embodiment of this concept can be observed in the terracotta reliefs from the Murlo palace, where two women are depicted under a parasol, riding in a carriage – an image often interpreted as a wedding procession.[53] Another example is found on one of the ends of Ramtha Vishnai’s sarcophagus, where a scene representing two women in a two-wheeled carriage, which could be reminiscent of marriage, is transposed into a funerary context (Figure 10).[54] Comparable iconography is also attested in the Greek area, the relief from Temple C in Metaponto, portraying a wedding procession with the bride and another woman seated in a mule-drawn carriage, being a famous example.[55]

Sarcophagus and lid with portraits of husband and wife, volcanic tuff, from Vulci, late 4th – early 3rd century B.C.E., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston acc. n. 1975.799, Museum purchase with funds by exchange from a Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius C. Vermeule III (Photograph © 2024 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

This dynamic of seeking guidance and support is visually captured through intimate physical contact between the two individuals. A clear depiction of this is evident on a series of Etruscan mirrors illustrating Turan and Elina (Helen), where Turan offers solace to Elina as she is about to accompany Paris or Menelaus. This quest for guidance and comfort materializes through close physical proximity, with Helen about to embrace Turan, who stretches out her arms towards the goddess (Figure 9a).[56] These mirrors also echo patterns and themes evidenced by Attic and South Italian vase painting.

In the Greek realm, it is well established that the moment of marriage marked a significant transition in the lives of young women. This phase, accompanied by associated expectations, found representation in a range of mythological scenes, ranging from depictions of abductions to divine unions.[57] Assessing the degree to which these concepts can be transposed to the Etruscan context is a complex process. However, it is worth noting that the visual language of mirrors, coupled with local interpretations of myth and the presence of Etruscan deities, is substantially similar to the imagery seen on Attic and South Italian vases.[58]

9 Conclusion: Life through Images

The analysis conducted thus far substantiates the interpretation of the two embracing and kissing female figures as a scene of farewell. Given that all the figures featured in this scene are female, it is plausible that it portrays the parting of a bride and her mother, a situation elevated and veiled by the mythological appellations assigned to the figures.[59] Thanr in particular, a figure potentially associated with liminal moments such as birth and death, might have also overseen marriage which, as we have already observed, denoted a pivotal transition in Etruscan women’s lives. This hypothesis paves the way for further potential insights into the prerogatives of this divine figure.

The absence of differentiation in age or ceremonial attire among the embracing figures does not contradict this interpretation, since this scene does not offer a direct representation of a bride and her mother, but rather elevates a psychologically charged moment into a higher, supra-personal tableau.[60] Here, the names likely denote auspicious tutelary concepts or deities, aligning with de Grummond’s interpretation of the figures. The iconography of the gesture might well evoke a scenario witnessed in the context of marriage. This synthesis crystallizes an experience into a dimension that, while grounded in the personal, transcends into a paradigm.[61]

The choice of figures included in this established scheme may have been influenced by the agency’s preferences. This interpretation gains momentum when considered in relation to the medium (the mirror) on which this image is portrayed. Despite recent reconsideration of the extent of male mirror usage, mirrors in the Etruscan world appear to have been predominantly used by women.[62] There is scholarly consensus that mirrors, alongside other toiletries, made suitable wedding gifts.[63] The inscription on the Cista Ficoroni hints at the possibility that these objects were given as a gift by mothers to their daughters.[64] Moreover, the selection of themes for decorating the reverse side of many mirrors, including scenes of adornment of the bride, courtship, divine unions, and births, gives further support to the possibility that many of them were indeed wedding gifts. Within this broader framework of values and customs, the reference to Demeter and Persephone might have been activated on a secondary level as hypostasis of a mother and daughter separated from each other, though not in the direct pursuit of depicting a specific mythological episode. Ultimately, the gestures of the characters manifest the concepts of separation and transition inherent in the wedding ceremony in classical antiquity (and beyond).[65]

Turning attention to the mirror’s potential subsequent role as an object of prestige, consideration is warranted of the possible reinterpretations of its iconography at different stages. Regarding its final use, it is likely that our mirror was discovered in a tomb, evidenced by its excellent condition and the fact that mirrors with known findspots are predominantly from funerary contexts. Hence, it is intriguing to consider how this farewell imagery, seemingly not originally conceived for funerals, might have been recontextualized at its deposition and reinterpreted to signify a final farewell (or conversely a reunion in the afterlife). This speaks to the mirror’s potential for narrating life-changing moments, traversing the lives of one or more individuals.[66]

This investigation into a seemingly simple gesture highlights the richness of meanings inherent in the iconography chosen for an object that was quite possibly in daily use by a well-to-do woman. Images and objects can unveil moments in life, emotions, and expectations. The interpretation of these moments might not be indisputable, yet it remains invaluable for reconstructing their original cultural context, otherwise lost forever.

Funding source: Open access funding provided by Scuola Normale Superiore within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Acknowledgements

The genesis of this study traces back to a research paper defended at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa in 2020. The core idea was later presented at the International Virtual Mirror Studies Conference in 2021, organized by Dr. Goran Đurđević, and was included in my MA thesis defended at the University of Pisa in the same year. I express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Gianfranco Adornato, my supervisor, and invaluable guide during my student years at the SNS. I also offer my warmest thanks to Prof. Lisa Rosselli and Prof. Marisa Bonamici, who supervised my MA thesis and generously provided valuable insights. My sincere thanks to Professors Anna Anguissola, Nancy de Grummond and Alexandra A. Carpino for fruitful and stimulating discussions. I owe special thanks to Prof. Stefano Bruni for constant support, and to Dr. Judith Swaddling for introducing me to the study of Etruscan mirrors and for her steadfast encouragement throughout this journey.I am grateful to the British Museum, the BnF, the Museo Salinas, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, the SABAP Umbria, in the persons of Dr. Luca Pulcinelli and Dr. Elena Roscini, for granting me permission to publish the images in this paper. I acknowledge the Department of Ancient Greece and Rome of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in the persons of Dr. Phoebe Segal and Daniel Cashman, for sponsoring Figure 9. I would also like to thank the anonymous referees of the JEIS for their constructive comments, and the editor Prof. Laurel Taylor for hosting my paper in this journal.

References

Ambrosini, L. 2005. “Sull’uso di modelli iconografici attici in un’officina di specchi etruschi tardo-classici.” StEtr 70: 161–82.Search in Google Scholar

Babbi, A. 2008. La Piccola Plastica Fittile Antropomorfa dell’Italia Antica dal Bronzo Finale all’orientalizzante. Pisa, Rome: Fabrizio Serra.Search in Google Scholar

Baggio, M. 2004. I Gesti della Seduzione. Tracce di comunicazione non-verbale nella ceramica greca tra VI e IV sec. a.C. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.Search in Google Scholar

Bagnasco Gianni, G. 2012. “Tra uomini e dei: Funzione e ruolo di alcuni oggetti negli specchi etruschi.” In Kulte, Riten, religiöse Vorstellungen bei den Etruskern und ihr Verhältnis zu Politik und Gesellschaft. Akten der 1. Internationalen Tagung der Sektion Wien/Österreich des Istituto Nazionale di Studi Etruschi ed Italici (Vienna, 4–6 December 2008), edited by P. Amann, 287–314. Vienna: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.Search in Google Scholar

Bartoloni, G., and F. Pitzalis. 2011. “Matrimonio Nel Mondo Etrusco.” In Thesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum, Vol. 6, 95–100.Search in Google Scholar

Benveniste, E. 1929. “Nom et origine de la déese étrusque Acaviser.” StEtr 3: 249–58.Search in Google Scholar

Binder, G., and R. Hurschmann. 1999. “s.v. Kuss.” In Neue Pauly, Vol. 6, 939–47.Search in Google Scholar

Bonamici, M. 2012. “La Scultura.” In Introduzione all’Etruscologia, edited by G. Bartoloni, 309–42. Milan: Hoepli.Search in Google Scholar

Bonfante, L. 1989. “La Moda Femminile Etrusca.” In Le Donne in Etruria, edited by A. Rallo, 157–71. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.Search in Google Scholar

Bonfante, L. 2015. “Etruscan Mirrors and the Grave.” In L’écriture et l’espace de la mort. Épigraphie et nécropoles à l’époque préromaine, edited by M.-L. Haack. Rome: Publications de l’École française de Rome.10.4000/books.efr.2741Search in Google Scholar

Bonfante, L. 2023. Images and Translations. The Etruscan Abroad. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.11505302Search in Google Scholar

Bruni, S. 2009. “Achvizr.” In Lexicon Iconographicum Mithologiae Classicae, Supplementum 2009, 1, Abellio–Zeus, 19–20. Düsseldorf: Artemis Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Bugge, S. 1883. “Beiträge zur Erforschung der etruskischen Sprache.” In Etruskische Forschungen und Studien, Vol. 4, edited by W. Deecke. Stuttgart: Albert Heitz, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.Search in Google Scholar

Burn, L. 1987. The Meidias Painter. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Search in Google Scholar

Camporeale, G. 1960. “Thalna e scene mitolgiche connesse.” StEtr 18: 233–62.Search in Google Scholar

Camporeale, G. 1966. “s.v. Thalna.” In EAA.Search in Google Scholar

Camporeale, G. 1994. “s.v. Thalna.” In LIMC VII.Search in Google Scholar

Camporeale, G. 2000. “La ceramica arcaica: impasti e buccheri.” In Gli Etruschi. Exhibition catalogue (Venice, Palazzo Grassi 2000), edited by M. Torelli, 404–19. Florence: Bompiani.Search in Google Scholar

Carpino, A. A. 2008. “Reflections from the Tomb: Mirrors as Grave Goods in Late Classical and Hellenistic Tarquinia.” EtrStud 11: 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/etst.2008.11.1.1.Search in Google Scholar

Cateni, G., and F. Fiaschi. 1984. Le urne di Volterra e l’artigianato artistico degli Etruschi. Florence: Sansoni.Search in Google Scholar

Catoni, M. L. 2005. Schemata. Comunicazione Non Verbale Nella Grecia Antica. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore.Search in Google Scholar

Cavalieri, E. 1929. Figure Mitologiche Degli Specchi “Etruschi” I. Thalna, Anchas, Maris Halna, Maris Isminthians. Rome: Tipografia La Speranza.Search in Google Scholar

Cavalieri, E. 1930. Figure Mitologiche Degli Specchi “Etruschi,” II. Achvizr. Rome: Tipografia La Speranza.Search in Google Scholar

Cavalieri, E. 1931. Figure Mitologiche Degli Specchi “Etruschi,” IV. Alpan. Rome: Tipografia La Speranza.Search in Google Scholar

Cavalieri, E. 1933. Figure Mitologiche Degli Specchi “Etruschi” VI. Thanr. Rome: Tipografia La Speranza.Search in Google Scholar

Cavalieri, E. 1932. Figure Mitologiche Degli Specchi “Etruschi,” V. Zipna. Rome: Tipografia La Speranza.Search in Google Scholar

Craddock, P. T. 1986. “The Metallurgy and Composition of Etruscan Bronze.” StEtr 52: 211–71.Search in Google Scholar

Cristofani, M. 1993. “Sul processo di antropomorfizzazione nel pantheon etrusco.” Miscellanea Etrusco-Italica 1: 9–21.Search in Google Scholar

CSE DDR I = Heres, G. 1986. CSE Deutsche Demokratische Republik I, Berlin—Staatliche Museen, Antikensammlung. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

CSE Italia 8 = Sassatelli, G., and A. Gaucci. 2018. CSE Italia 8, Musei dell’Etruria Padana. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.Search in Google Scholar

CSE Schweiz 1 = Jucker, I. 2001. CSE Schweiz 1, Basel, Schaffhausen, Bern, Lausanne. Bern: Stämpfli Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

CSE U.S.A. 3 = Bonfante, L.. 1997. CSE U.S.A. 3, New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider.Search in Google Scholar

de Angelis, F. 2015. “Il destino di Hasti Afunei. Donne e famiglia nell’epigrafia sepolcrale di Chiusi.” In L’écriture et l’espace de la mort. Épigraphie et nécropoles à l’époque préromaine, edited by M. L. Haack. Rome: École française de Rome.10.4000/books.efr.2765Search in Google Scholar

de Grummond, N. T., ed. 1982. A Guide to Etruscan Mirrors. Tallahasse: Archaeological News.Search in Google Scholar

de Grummond, N. T. 2000. “Mirrors and Manteia: Themes of Prophecy on Etruscan and Praenestine Mirrors.” In Aspetti e problemi della produzione degli specchi etruschi figurati. Atti dell’incontro internazionale di studio (Rome, 2–4 May 1997, edited by M. D. Gentili, 27–67. Rome: Aracne.Search in Google Scholar

de Grummond, N. T. 2002. “Mirrors, Marriage, and Mysteries.” In Pompeian Brothels, Pompeii’s Ancient History, Mirrors and Mysteries, Art and Nature at Oplontis, and the Herculaneum “Basilica, edited by T. McGinn, 62–85. Portsmouth.Search in Google Scholar

de Grummond, N. T., ed. 2006. Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.Search in Google Scholar

De Stefano, F. 2016. “La dea del Tempio C di Metaponto. Una nuova ipotesi interpretativa.” AttiMGrecia s. IV (6): 131–54.Search in Google Scholar

Emiliozzi, A., and A. Maggiani, eds. 2002. Caelatores. Incisori di specchi e ciste tra Lazio ed Etruria. Atti della Giornata di studio (Rome, 4 May 2001). Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche.Search in Google Scholar

ET2 = Meiser, G., ed. 2014. Etruskische Texte. Editio Minor. Hamburg: Baar Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Ernoult, N. 2015. “Les relations filles/mères autour de la question du mariage daans l’Athènes Classique.” Cahiers Mondes Anciens 6.10.4000/mondesanciens.1339Search in Google Scholar

ET = Rix, H., ed. 1991. Etruskische Texte. Editio Minor. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.Search in Google Scholar

Fabretti, A. 1867. Corpus Inscriptionum Italicarum. Torino: Officina Regia.Search in Google Scholar

Feruglio, A. E. 1982. “Tomba Hescanas.” In Pittura Etrusca a Orvieto. Le tombe di Settecamini e degli Hescanas a un secolo dalla scoperta. Documenti e materiali, 25–7. Rome: Edizioni Kappa.Search in Google Scholar

Feruglio, A. E. 1997. “Uno specchio della necropoli di Castel Viscardo, presso Orvieto, con Apollo, Turan e Atunis.” In Etrusca et Italica. Scritti in ricordo di Massimo Pallottino, 299–314. Pisa, Rome: Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali.Search in Google Scholar

Feruglio, A. E. 2003. “La Tomba Volsiniese degli Hescanas: restauri e nuove letture.” In Pittura etrusca: problemi e prospettive. Atti del convegno, Sarteano, Teatro Comunale degli Arrischianti (26 October 2001), Chiusi, Teatro Comunale Mascagni (27 October 2001), edited by A. Minetti, 118–39. Siena: Protagon Editori Toscani.Search in Google Scholar

Fiesel, E. 1934. “s.v. Thanr.” In RE.Search in Google Scholar

Gagé, J. 1954. “Alpanu, la Némésis étrusque, et l’Extispicium du siège de Véies.” MÉFRA 66: 39–78. https://doi.org/10.3406/mefr.1954.8527.Search in Google Scholar

Gerhard, E. 1864. “Ceres und Proserpina, etruskischer Spiegel.” AA 192a 300–301.Search in Google Scholar

Izzet, V. 2007. The Archaeology of Etruscan Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511735189Search in Google Scholar

Jenkins, I. 1983. “Is There Life after Marriage? A Study of the Abduction Motif in Vase Paintings of the Athenian Wedding Ceremony.” BICS 30 (1): 13–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-5370.1983.tb00443.x.Search in Google Scholar

Jucker, H. 1982. “Abwandlung eines bekannten Themas.” In Antidoron. Festschrift für Jürgen Thimme zum 65. Geburstag, edited by D. Metzler, B. Otto, and C. Müller-Wirth, 137–42. Karlsruhe: C.F. Müller.Search in Google Scholar

Körte, G. 1916. I Rilievi Delle Urne Etrusche, Vol. 3. Berlin: Reimer.Search in Google Scholar

Lambrechts, R. 1981a. “s.v. Achvizr.” In LIMC I.Search in Google Scholar

Lambrechts, R. 1981b. “s.v. Alpan.” In LIMC I.Search in Google Scholar

Lambrechts, R. 1997. “s.v. Zipna.” In LIMC VII.Search in Google Scholar

Lambrechts, R. 2000. “‚‘‘L‘étude et l’édition des mirroirs étrusques. Quelques réflexion et questions de méthode.” In Aspetti e problemi della produzione degli specchi etruschi figurati. Atti dell’incontro internazione di studio (Rome, 2–4 May 1997, edited by M. D. Gentili, 165–79. Rome: Aracne.Search in Google Scholar

Maggiani, A. 2002. “Nel Mondo Degli Specchi Etruschi.” In Caelatores. Incisori di specchi e ciste tra Lazio ed Etruria. Atti della Giornata di studio (Rome, 4 May 2001), edited by A. Emiliozzi, and A. Maggiani, 7–22. Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche.Search in Google Scholar

Mangieri, A. F. 2010. “Legendary Women and Greek Womanhood: The Heroines Pyxis in the British Museum.” AJA 114 (3): 429–45. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.114.3.429.Search in Google Scholar

Mansuelli, G. 1943. “Materiali per un supplemento del ‘corpus’ degli specchi etruschi figurati.” StEtr 17: 487–521.Search in Google Scholar

Mansuelli, G. 1946–1947. “Gli Specchi Figurati Etruschi.” StEtr 19: 9–137.Search in Google Scholar

Mansuelli, G. 1948–1949. “Studi Sugli Specchi Etruschi. IV. La Mitologia Figurata Negli Specchi Etruschi.” StEtr 20: 59–98.Search in Google Scholar

Maras, D. F. 2001 (1998). “La Dea Thanr e le cerchie divine in Etruria: nuove acquisizioni.” StEtr 64: 173–97.Search in Google Scholar

Maras, D. F. 2003. Il dono votivo. Gli dei e il sacro nelle iscrizioni etrusche di culto. Pisa-Rome: Fabrizio Serra.Search in Google Scholar

Massa-Pairault, F. H. 1983. “Problemi di lettura della pittura funeraria di Orvieto.” DialArch s III (I): 19–42.Search in Google Scholar

Masséglia, J. 2015. Body Language in Hellenistic Art and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Menichetti, M. 2008. “Lo specchio nello spazio femminile. Tra rito e mito.” In Image et religion dans l’antiquité gréco-romaine. Actes du colloque de Rome (Rome, 11–13 December 2003), edited by S. Estienne, 217–30. Naples: Centre Jean Bérard.10.4000/books.pcjb.4536Search in Google Scholar

Mertens-Horn, M. 1992. “Die archaischen Baufriese aus Metapont.” RM 99: 1–122.Search in Google Scholar

Pfiffig, A. J. 1975. Religio Etrusca. Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt.Search in Google Scholar

Pieraccini, L. 2014. “The Ever Elusive Etruscan Egg.” EtrStud 17: 267–92. https://doi.org/10.1515/etst-2014-0015.Search in Google Scholar

Pieraccini, L., and M. Del Chiaro. 2014. “Greek in Subject, Etruscan by Design: Alcestis and Admetus on an Etruscan Red-Figure Krater.” In The Regional Production of Red-Figure Pottery: Greece, Magna Grecia and Etruria, edited by S. Schierup, and V. Sabetai, 304–10. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.10.2307/jj.608200.21Search in Google Scholar

Rabinowitz, N. S. 2002. “Excavating Women’s Homoeroticism in Ancient Greece: The Evidence from Attic Vase Painting.” In Among Women: From the Homosocial to the Homoerotic in the Ancient World, edited by N. S. Rabinowitz, and L. Auanger, 106–66. Austin: University of Texas Press.10.7560/771130-008Search in Google Scholar

Rocchetti, L. 1958a. “s.v. Achvizr.” In EAA.Search in Google Scholar

Rocchetti, L. 1958b. “s.v. Alpan.” In EAA.Search in Google Scholar

Rocchetti, L. 1966. “s.v. Zipna.” In EAA.Search in Google Scholar

Roulez, J. 1862. “Un miroir et deux trépieds.” AdI 34: 177–208.Search in Google Scholar

Rowland, I. 2008. “Marriage and Mortality in the Tetnies Sarcophagi.” EtrStud 11: 151–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/etst.2008.11.1.151.Search in Google Scholar

Säflund, G. 1993. Etruscan Imagery. Symbol and Meaning. Jonsered: Paul Åströms Förlag.Search in Google Scholar

Sandhoff, B. 2019. “Transitory Nudity: Life Changes in Etruscan Art.” In The Ancient Art of Transformation. Case Studies from Mediterranean Contexts, edited by R. M. Gondek, and C. L. Sulosky Weaver, 52–74. Oxford: Oxbow Books.10.2307/j.ctv13nb7mr.10Search in Google Scholar

Sarcone, G. 2021. “A Flower for Nikandre. On the Iconography of the First Kore.” ASAtene 99 (1): 193–214.Search in Google Scholar

Shapiro, A. 1993. Personification in Greek Art. Zürich: Akanthus.Search in Google Scholar

Sherling, K. 1934. “s.v. Thalna.” In RE.Search in Google Scholar

Sowder, C. L. 1982. “Etruscan Mythological Figures.” In A Guide to Etruscan Mirrors, edited by N. T. de Grummond, 100–28. Tallahasse: Archaeological News.Search in Google Scholar

Swaddling, J., and S. Woodford. 2014. “Lokrian Ajax and the New Face of Troilos: The Troilos Mirror in the British Museum.” Mediterranea 9: 11–26.Search in Google Scholar

Szilágyi, J. G. 1995. “Discourse on Method: A Contribution to the Problem of Classifying Late Etruscan Mirrors.” EtrStud 2: 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1515/etst.1995.2.1.35.Search in Google Scholar

Torelli, M. 1997. Il Rango, Il Rito, l’immagine. Alle Origini Della Rappresentazione Storica Romana. Milan: Mondadori Electa.Search in Google Scholar

Torelli, M., and E. Marrone. 2016. L’obolo di Persefone: immaginario e ritualità dei pinakes di Locri. Pisa: ETS Edizioni.Search in Google Scholar

Walters, H. B. 1899. Catalogue of the Bronzes, Greek, Roman, and Etruscan in the British Museum. London: Printed by the Order of the Trustees.Search in Google Scholar

Weber-Lehmann, C. 1994. “s.v. Thanr.” In LIMC VII.Search in Google Scholar

Weber-Lehmann, C. 2009. “s.v. Thanr.” In LIMC Suppl. I.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the Editor

- Letter from the Editor

- Articles

- An Ivory Writing Tablet from Poggio Civitate (Murlo)

- A Re-Evaluation of the Iconography of the Etruscan Bronze Lamp of Cortona

- An Etruscan Inscription Rediscovered

- Weaving in the Ager Faliscus: A Contextual Approach to the Analysis of Loom Weights from the Sites of Falerii, Narce, Vignanello, Corchiano and Grotta Porciosa

- The Etruscan Kiss and Embrace: A Mirror at the British Museum and a Lifetime in a Gesture

- News from the Field

- Excavations at Poggio Civitate (Murlo): The 2023 Field Season

- The Tomb of the Rings and the Tomb of the Linen. New Data for a Late Etruscan Community in the Middle Valley of the Ombrone River (Civitella Paganico – Italy)

- Museum Notice

- Archeologia svelata a Sesto Fiorentino. Momenti di vita nella piana prima, durante e dopo gli Etruschi, Sesto Fiorentino, Biblioteca Ernesto Ragionieri, September 29, 2023–July 31, 2024, curated by Valentina Leonini and Barbara Arbeid.

- Book Reviews

- Laura Banducci and Anna Gallone: A Cemetery and Quarry from Imperial Gabii (Gabii Project Reports Series 2)

- Jorma Kaimio: The Funerary Inscriptions of Hellenistic Perusia (Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 50)

- Giulio Paolucci: Viaggio archeologico nell’antica Etruria By Wilhelm Dorow

- Claudia Carlucci: Terrecotte architettoniche etrusco-laziali: I sistemi decorativi della II fase iniziale (Supplementi e monografie della rivista Archeologia Classica 17)

- F. Fabiani and G. Gattiglia: Paesaggi urbani e rurali in trasformazione. Contesti e dinamiche dell’insediamento letti alla luce della fonte archeologica

- Alessandro Sebastiani and Carolina Megale: Archaeological Landscapes of Roman Etruria. Research and Field Papers (MediTo – Archaeological and Historical Landscapes of Mediterranean Central Italy 1)

- Maurizio Sannibale: Principi etruschi in Laboratorio. La tomba Regolini-Galassi analizzata

- Lisa Pieraccini and Laurel Taylor: Consumption, Ritual, Art, and Society. Interpretive Approaches and Recent Discoveries of Food and Drink in Etruria. New approaches in Archaeology 2

- Carmen Sánchez Fernández and Jorge Tomás García: La cerámica ática fuera del Ática. Contextos, usos y miradas (Studia Archaeologica 256)

- Charlotte R. Potts: Architecture in Ancient Central Italy: Connections in Etruscan and Early Roman Building (British School at Rome Studies)

- 2024 Research Fellowships

- 2024 Fellowship Award Recipients

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Letter from the Editor

- Letter from the Editor

- Articles

- An Ivory Writing Tablet from Poggio Civitate (Murlo)

- A Re-Evaluation of the Iconography of the Etruscan Bronze Lamp of Cortona

- An Etruscan Inscription Rediscovered

- Weaving in the Ager Faliscus: A Contextual Approach to the Analysis of Loom Weights from the Sites of Falerii, Narce, Vignanello, Corchiano and Grotta Porciosa

- The Etruscan Kiss and Embrace: A Mirror at the British Museum and a Lifetime in a Gesture

- News from the Field

- Excavations at Poggio Civitate (Murlo): The 2023 Field Season

- The Tomb of the Rings and the Tomb of the Linen. New Data for a Late Etruscan Community in the Middle Valley of the Ombrone River (Civitella Paganico – Italy)

- Museum Notice

- Archeologia svelata a Sesto Fiorentino. Momenti di vita nella piana prima, durante e dopo gli Etruschi, Sesto Fiorentino, Biblioteca Ernesto Ragionieri, September 29, 2023–July 31, 2024, curated by Valentina Leonini and Barbara Arbeid.

- Book Reviews

- Laura Banducci and Anna Gallone: A Cemetery and Quarry from Imperial Gabii (Gabii Project Reports Series 2)

- Jorma Kaimio: The Funerary Inscriptions of Hellenistic Perusia (Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae 50)

- Giulio Paolucci: Viaggio archeologico nell’antica Etruria By Wilhelm Dorow

- Claudia Carlucci: Terrecotte architettoniche etrusco-laziali: I sistemi decorativi della II fase iniziale (Supplementi e monografie della rivista Archeologia Classica 17)

- F. Fabiani and G. Gattiglia: Paesaggi urbani e rurali in trasformazione. Contesti e dinamiche dell’insediamento letti alla luce della fonte archeologica

- Alessandro Sebastiani and Carolina Megale: Archaeological Landscapes of Roman Etruria. Research and Field Papers (MediTo – Archaeological and Historical Landscapes of Mediterranean Central Italy 1)

- Maurizio Sannibale: Principi etruschi in Laboratorio. La tomba Regolini-Galassi analizzata

- Lisa Pieraccini and Laurel Taylor: Consumption, Ritual, Art, and Society. Interpretive Approaches and Recent Discoveries of Food and Drink in Etruria. New approaches in Archaeology 2

- Carmen Sánchez Fernández and Jorge Tomás García: La cerámica ática fuera del Ática. Contextos, usos y miradas (Studia Archaeologica 256)

- Charlotte R. Potts: Architecture in Ancient Central Italy: Connections in Etruscan and Early Roman Building (British School at Rome Studies)

- 2024 Research Fellowships

- 2024 Fellowship Award Recipients