Abstract

The goal of this work was to synthesis a novel aromatic multiamide derivative based on 1H-benzotriazole (PB) as an organic nucleating agent for poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA), and investigate the effect of PB on the non-isothermal crystallization, melting behavior and thermal decomposition of PLLA. Here, PB was firstly synthesized through 1H-benzotriazole aceto-hydrazide and terephthaloyl chloride, then PB-nucleated PLLA was fabricated via melt-blending technology at various PB concentration from 0.5 wt% to 3 wt%. Finally, the thermal performances were evaluated through differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The high thermal decomposition temperature of PB indicated that PB possessed possibility as a nucleating agent for PLLA, and the non-isothermal crystallization behavior confirmed the crystallization accelerating effectiveness of PB for PLLA. Upon optimum concentration of 2 wt%, the onset crystallization temperature, the crystallization peak temperature and the non-isothermal crystallization enthalpy increased from 101.4°C, 94.5°C and 0.1 J·g-1 to 121.3°C, 115.8°C and 35.1 J·g-1, respectively. In addition, the non-isothermal crystallization behavior was also affected by the cooling rate and the final melting temperature. The melting behavior further evidenced the advanced nucleating ability of PB, and the competitive relationship between PB and the heating rate, the nuclear rate and crystal growth rate. Thermal stability measurement showed that PB with a concentration of 1 wt%–2 wt% could slightly improve the thermal stability of PLLA.

1 Introduction

Poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA), as one of the most popular environment-friendly polymers, can succeed in inhibiting the environmental pollution from the source. Thus, PLLA has attracted more attention in various applications including food packaging (1), the automobile industry (2), toy manufacturing (3), electronic devices (4), etc., because of its excellent biodegradability (5). Furthermore, more modified PLLA materials were fabricated to improve the relevant performance (6, 7). For example, a small amount of pristine vermiculite (<3 wt%) could display dispersion very well in the PLLA matrix, and the tensile modulus and Izod impact strength of PLLA containing the pristine vermiculite caused a increase from 1.70 GPa and 9.26 J/m to 2.00 GPa and 11.56 J/m with the pristine vermiculite content increasing from 0 wt% to 10 wt%, respectively. In addition, the incorporation of pristine vermiculite could also decrease the crystallization time of PLLA (8). Through tensile properties analysis, the addition of graphene oxide, especially the 1 wt% graphene oxide, could slightly reinforce the mechanical properties including Young modulus, tensile strength at yield and tensile strength at the break. Enzymatic degradation showed that the biodegradation rates of PLLA increased with the addition of graphene oxide, the reason was that the polar hydrophilic groups of graphene oxide accelerated the penetration of water molecules in the PLLA matrix, resulting in the accelerated effect of graphene oxide on the degradation of PLLA (9). After irradiation-induced crosslinking using triallyl isocyanurate, the heat defection temperature of PLLA/basalt fiber composites could increase to 140°C, which probably exhibited a promising application in tableware (10). Through the sustainable improvements of these performances, it will be a fact that PLLA is a very credible alternative to petroleum-based polymers.

Though some inherent disadvantages of PLLA have been overcome, compared to other widely-used conventional commodity polymers, the slow crystallization rate of PLLA, resulting from low L-lactide content in synthesis stage, still seriously affects the processability and subsequent physical properties including dimensional stability, heat resistance, crystallization performance, etc. The incorporation of a nucleating agent is an easy and effective method for improving the crystallization rate of semicrystalline polymers, which has also been used in PLLA resin (11, 12). Among the reported nucleating agents, inorganic nucleating agents focused on clay (13, 14), nano oxide (15, 16), nano metal salt (17), carbon materials (18, 19), etc. However, inorganic nucleating agents were often modified using organic reagents to enhance the dispersibility and compatibility, resulting in more complicated nucleation. On the other hand, the high concentration inorganic nucleating agents could also lead to a notable decrease of the mechanical properties and plasticity of PLLA. Thus, to avoid the relevant defects of inorganic nucleating agents, organic nucleating agents were chosen or synthesized to be introduced into PLLA matrix in recent years. Many organic compounds, such as phthalimide (20), ethylenebishydroxystearamide (21), ethylenebisstearamide (22), aliphatic diacyl adipic dihydrazides (23), benzoyl hydrazine derivatives (24, 25), salicyhydrazide derivatives (26), oxalamide derivatives (27), etc., could serve as good nucleating agents for the crystallization of PLLA. Moreover, it is found that the structures of these organic nucleating agents exhibit the common amide group, indicating that the amide group may significantly affect the crystallization behavior of PLLA. Thus, it is very necessary to design and synthesise new compounds containing a different amide number to further demonstrate the nucleating effect of the amide group. In previous work (28), we had reported that N, N′-bis(1H-benzotriazole) adipic acid acethydrazide, an aliphatic multiamide derivative based on 1H-benzotriazole, had excellent acceleration effectiveness for the non-isothermal crystallization process of PLLA. In particular, as a result, 1 wt% N, N′-bis(1H-benzotriazole) adipic acid acethydrazide caused the onset crystallization temperature (To) of the pristine PLLA to increase to 126.3°C, Which was very close to 0.85 time temperature of the melting temperature of PLLA. As far as organic nucleating agents based on 1H-benzotriazole, 1H-benzotriazole derivatives with different structure should be further developed to explore the nucleation mechanism. Thus, in this paper, an aromatic multiamide derivative based on 1H-benzotriazole, N, N′-bis(1H-benzotriazole) terephthalic acid acethydrazide (designated as PB), was synthesized from 1H-benzotriazole and terephthalic acid to investigate its role as a heterogeneous nucleator in the PLLA matrix, and the non-isothermal crystallization, melting behavior, and thermal stability of PB-nucleated PLLA were investigated in detail through DSC, TGA, etc.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

PLLA was purchased from Nature Works LLC (USA), and the basic parameters of the purchased PLLA are: the D content 4.25%, the Mw 1.95×105. All other chemical reagents used to synthesis PB were obtained from Chuandong Chemical Reagent Co. (Chongqing, China).

2.2 Synthesis of PB

The synthetic route of PB is described in Scheme 1, and the detailed synthetic operation is similar to our previous work (28). IR (KBr) υ: 3474.2, 3250.3.2, 2949.1, 2849.1, 1701.5, 1674.3, 1612.7, 1551.4, 1497.1, 1456.8, 1412.7, 1367.3, 1329.4, 1309.5, 1254.1, 1231.1, 1167.7, 1136.6, 1112.6, 1018.6, 998.6, 976.3, 962.6, 799.3, 775.3, 750.5, 622.3 cm-1; 1H NMR (DMSO, 400 MHz) δ: ppm; 10.61 (s, 2H, NH), 7.41–8.08 (m, 4H, Ar), 5.64 (s, 2H, CH2).

Synthetic route of PB.

2.3 Preparation of PLLA/PB sample

PLLA and PB were dried for 24 h at 45°C in a vacuum oven to make sure that the residual water was removed completely. The blend of PLLA containing various PB concentrations was operated on a counter-rotating mixer (Harbin Hapro Electric Technology Co., Ltd., Heilongjiang, China) with a rotation speed of 32 rpm for 7 min at 180°C, and at 64 rpm for 7 min. Then the blend was hot pressed at 180°C for 5 min, removed from the hot press and cool pressed at room temperature for 5 min to obtain sheets with 0.4 mm thickness for relevant measurement.

2.4 Characterization and test

2.4.1 Infrared spectra (IR)

A few PB were ground with spectrography KBr pellets in agate mortar, then the dried mixture was pressed into thin slices through a pressing device using 20 tons. Finally, the IR was measured on a Bio-Rad FTS135 spectrophoto meter from 4000 to 400 cm-1.

2.4.2 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR)

The PB was dissolved in deuterium dimethyl sulfoxide, and the 1H NMR of PB was recorded on a Brucker AVANCE 400 MHz spectrometer.

2.4.3 Differential scanning calorimeter (DSC)

The cold crystallization and melting behavior of the neat PLLA and PLLA/PB samples were performed in a TA Instrument Q2000 DSC under nitrogen at a rate of 50 mL/min. The temperature and heat flow at different heating rates were calibrated using an indium standard before testing. Then all samples were put into the aluminum crucible to be heated to the final set melting temperature to eliminate heat history, and the relevant measurements was carried out under different conditions.

2.4.4 Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The thermogravimetric process of PB, the neat PLLA and PLLA/PB samples were recorded on a TA Instrument Q500 TGA in a flow of air (60 mL/min) from room temperature to 650°C at different heating rates.

3 Results and discussion

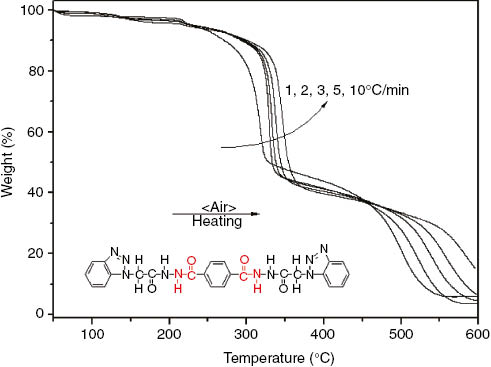

3.1 Thermogravimetric analysis of PB

One of the most important features of the nucleating agent is the high decomposition temperature, ensuring that the nucleating agent can not decompose at the blending stage. Figure 1 shows the TGA curves of PB from room temperature to 600°C at different heating rates. Through the TGA measurement, it is clear that PB has three decomposition stages, and the most weight loss occurs in the first stage. On the other hand, it is also clear that the onset decomposition temperature of PB depends on the heating rate. That is, the onset decomposition temperature increases with the increase of heating rate, resulting from the heat hysteresis (29). In comparison to other heating rates, the onset decomposition temperature of PB at the heating rate of 1°C/min has the minimum value 300.4°C, this result shows that the onset decomposition temperature of PB is higher than the blending temperature of PLLA, indicating that PB satisfies the basic requirement of a nucleating agent for PLLA. In addition, PB exhibits a slight drop in weight loss before the onset decomposition, the probable reason is that PB contains a small amount of adsorbed water.

TGA curves of PB at different heating rates.

3.2 Non-isothermal crystallization

As previously mentioned, high decomposition temperature made PB possess a possibility as a nucleating agent for PLLA. In this section, the non-isothermal crystallization behavior of PLLA modified by various PB concentration was investigated to examine the nucleating effect of PB. Figure 2 is the non-isothermal crystallization of the neat PLLA and PLLA containing different PB concentrations from the melt at the cooling rate of 1°C/min. As seen in Figure 2, the non-isothermal crystallization peak of the neat PLLA almost can not be observed in the cooling crystallization procedure, this result evidences the inherent poor crystallization ability of the neat PLLA as known (30). However, with the addition of PB, the sharp non-isothermal crystallization peaks of all PLLA containing PB appear in the DSC cooling curves, indicating that PB plays a more important role in improving the crystallization of PLLA. Moreover, when PB concentration is 0.5 wt%–2 wt%, the non-isothermal crystallization peak shifts to a higher temperature with the increase of PB concentration, showing PB can act as a heterogeneous nucleating agent for the crystallization of PLLA, because homogeneous nucleation effectively gives rise to a decrease in the higher temperature zone. However, when PB exceeds 2 wt%, the non-isothermal crystallization peak begins to shift to low temperatures, we suggest the reason for this change was that excessive PB seriously impedes the mobility of the PLLA molecular chains, which is not beneficial to the crystal growth. On the other hand, these results also indicate that 2 wt% PB is the optimum concentration to achieve the best nucleating effect for PLLA. The relevant DSC data is listed in Table 1. As seen in Table 1, compared to the neat PLLA, with the addition of 2 wt% PB, the To, the crystallization peak temperature (Tcp), and the non-isothermal crystallization enthalpy (ΔHc) increase from 101.4°C, 94.5°C and 0.1 J·g-1 to 121.3°C, 115.8°C and 35.1 J·g-1, respectively. In addition, the melting peak temperature (Tm) also increases to 148.5°C.

In the plastics industry, it is expected that polymers can achieve high crystallinity at high cooling rates. Thus, it is of considerable interest to investigate the influence of cooling rate on the non-isothermal crystallization behavior. Figure 3 shows the DSC curves of PLLA/PB samples at the cooling rate of 2, 4, 8°C/min. It is clear that the non-isothermal crystallization peaks become wider and shift to lower temperatures with the increase of the cooling rate. When the cooling rate is 8°C/min, compared to other PLLA/PB samples, the PLLA/2%PB still has a discernible non-isothermal crystallization peak, further confirming the best nucleating effective of 2 wt% PB for PLLA. And the disappearance of non-isothermal crystallization peaks of other PLLA/PB samples results from the cooling rate that is predominant in this circumstance, compared to the nucleating effect of PB. Similar results were also reported in other literature (31, 32).

Non-isothermal crystallization of the neat PLLA and PLLA/PB samples at a cooling rate of 1°C/min.

DSC data of the neat PLLA and PLLA/PB samples crystallized from the melt at cooling rate of 1°C/min.

| Sample | Rate (°C/min) | To (°C) | Tcp (°C) | ΔHc (J·g-1) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLLA | 1 | 101.4 | 94.5 | 0.1 | – |

| PLLA/0.5%PB | 1 | 116.8 | 111.0 | 34.8 | 147.5 |

| PLLA/1%PB | 1 | 119.3 | 113.2 | 34.5 | 148.0 |

| PLLA/2%PB | 1 | 121.3 | 115.8 | 35.1 | 148.5 |

| PLLA/3%PB | 1 | 119.3 | 113.4 | 34.4 | 147.9 |

Non-isothermal crystallization of PLLA/PB at different cooling rates.

According to like dissolves like, the solubility of PB in the PLLA matrix depends on the final melting temperature of the PLLA, and this solubility difference can dramatically affect the non-isothermal crystallization behavior due to the undissolved additive as nuclei for the PLLA and dissolved additive in cooling (33). The evaluation of the influence of the final melting temperature on the non-isothermal crystallization behavior was therefore performed. Figure 4 shows the non-isothermal crystallization curves of PLLA/PB samples at a cooling rate of 1°C/min from the different final melting temperatures. It is clear from Figure 4 that the non-isothermal crystallization behavior of PLLA is related to the set final melting temperature as well as PB concentration. When the set final melting temperature is 190°C, PLLA/PB samples exhibit the highest Tcp, indicating 190°C is the optimization blending temperature for PLLA/PB. In addition, under the same final melting temperature, PLLA/2%PB has the highest Tcp, further confirming the best effect of crystallization at 2 wt% PB. In particular, when the set final melting temperature is 210°C, the Tcp between PLLA/2%PB and PLLA/0.5%PB appears the maximum difference 5.2°C. The study on the effect of the final melting temperature on the crystallization of the polymer may be very helpful to adjust the blending parameters to prepare the high crystallinity-modified polymer and to study the nucleation mechanism between polymer and the additives.

Non-isothermal crystallization of PLLA/PB samples from the different final melting temperatures.

3.3 Melting behavior

The results of non-isothermal crystallization measurements revealed that the PB, as a crystallization accelerator, significantly affected the non-isothermal crystallization behavior of PLLA. Undoubtedly, PLLA/PB samples must exhibit the different melting behavior because of the introduction of PB. Figure 5 presents the melting behavior of PLLA and PLLA/PB samples at a heating rate of 1°C/min after non-isothermal crystallization at a cooling rate of 1°C/min. It is observed from Figure 5 that all PLLA/PB samples have double melting peaks, whereas PLLA only exhibits a single melting peak. According to the melting-recrystallization mechanism (34), the low-temperature melting peak is attributed to the primary crystallites formed during non-isothermal crystallization, and the high-temperature melting peak reflects the crystallites formed during the second heating procedure. In the melting curve of the neat PLLA, the low-temperature melting peak do not appear, implying that no crystallites are formed during the non-isothermal crystallization process, this result also further confirms the poor crystallization ability of the neat PLLA. What is worse, the neat PLLA only appears very weak high-temperature melting peak during the second heating scan. However, for PLLA/PB samples, both the low-temperature melting peak and high-temperature melting peak are very obvious and sharp. Moreover, with the increase of PB concentration, the melting temperature of the low-temperature melting peak first increases, then decreases, and PLLA/2%PB has the highest melting temperature. This trend is consistent with the aforementioned non-isothermal crystallization results. However, the high-temperature melting peaks are not related to the PB concentration, indicating that the perfection of crystallites formed during the second heating scan only depends on the heating rate after non-isothermal crystallization.

The melting behavior of PLLA and PLLA/PB samples at a heating rate of 1°C/min after non-isothermal crystallization.

From non-isothermal crystallization it has been evidenced that 2 wt% PB has the best nucleating effect for PLLA. Thus, in the melting behavior section, we focus on the investigation the melting behavior of PLLA/2%PB under different conditions. Figure 6 shows is the melting behavior of PLLA/2%PB at different heating rates after non-isothermal crystallization. The double melting peaks gradually degenerate to the single melting peak with increasing of the heating rate from 1°C/min to 10°C/min, finally, the high-temperature melting peak exists in the form of pulse. The increasing of the heating rate also leads to a shift of the high-temperature melting peak to low temperature, resulting from the increase of imperfect crystallites. Thus, compared to the nucleating effect of PB, the heating rate is predominant in the second heat crystallization.

The melting behavior of PLLA/2%PB at different heating rates after non-isothermal crystallization.

Figure 7 shows the melting behavior of PLLA/2%PB after isothermal crystallization at different crystallization temperatures for 120 min. Usually, the nuclear rate is faster than the crystal growth rate in the low-temperature region, in contrast, the crystal growth rate is faster in the high-temperature region. It is clear that PLLA/2%PB still has the double melting peaks in the low-temperature region after sufficient crystallization, the reason is that the macromolecule segment mobility is very poor at 100°C, resulting in the slow crystal growth rate, though the heterogeneous nucleation of PB and homogeneous nucleation of PLLA itself in the low-temperature region are prominent. Whereas PLLA/2%PB only exhibits the single melting peak after isothermal crystallization in the high-temperature region, resulting from the synergistic effect of heterogeneous nucleation of PB and excellent macromolecule segment mobility in the high-temperature region. In addition, it is noted that the single melting peak shifts to higher temperature with the increase of crystallization temperature, indicating the crystallites formed at the higher crystallization temperature are more prefect.

The melting behavior of PLLA/2%PB after isothermal crystallization at different crystallization temperatures for 120 min.

3.4 Thermal stability

Thermal stability of thermoplastic resin is one of the most important testing index before commercial application. Especially, when the thermoplastic resin is exposed to the temperatures above its melting point, investigating the thermal stability can obtain useful information for applications or processes (35). Thus, it is necessary to investigate the thermal stability of PLLA containing PB to obtain the relevant thermal decomposition temperature and evaluate the effect of PB on the thermal decomposition behavior of PLLA. Figure 8 shows the TGA curves of the neat PLLA and PLLA/PB samples at a heating rate of 5°C/min under air. As seen in Figure 8, the presence of PB does not change the thermal decomposition behavior of the neat PLLA, and both the neat PLLA and PLLA/PB samples have only one thermal decomposition stage, showing that the PLLA is compatible with PB to a certain degree (36). However, the presence of PB can affect the onset decomposition temperature (defined as Tod) of PLLA. Upon heating at 5°C/min, the Tod of the neat PLLA, PLLA/0.5%PB, PLLA/1%PB, PLLA/2%PB and PLLA/3%PB are 341.1°C, 340.1°C, 342.7°C, 341.9°C and 340.9°C, respectively. And PLLA/1%PB and PLLA/2%PB exhibit slightly higher Tod than the neat PLLA, that is, when the PB concentration is from 1 wt% to 2 wt%, the addition of PB can to some extent improve the thermal stability of PLLA. The possible reason for this result is that there exists a moderate interaction between PLLA and PB with a concentration from 1 wt% to 2 wt%, resulting in that PLLA can decompose after the destruction of this interaction. Similar phenomenon has been found in the PLLA/N, N-dilauryl chitosan system (37), and the PLLA/N, N′-bis(benzoyl) suberic acid dihydrazide system (38).

TGA curves of PLLA and PLLA/PB samples at a heating rate of 5°C/min.

4 Conclusion

The multiamide organic nucleating agent PB was synthesized from 1H-benzotriazole aceto-hydrazide and terephthaloya chloride which was deprived from p-phthalic acid via acylation, and the PB was introduced into the PLLA matrix to be used as a kind of heterogeneous nucleation agent for PLLA. The non-isothermal crystallization behavior showed that the crystallization of neat PLA on cooling was negligible, however, the addition of PB could significantly improve PLLA’s crystallization performances including the To, Tcp and ΔHc, and the 2 wt% PB exhibited the optimum concentration to achieve the best nucleating effect for PLLA. Non-isothermal crystallization behavior also revealed that the increase of the cooling rate could effectively weaken the nucleation effect of PB, and the 190°C was the optimum melting blending temperature for PLLA/PB. A comparative study of the melting behavior further confirmed the advanced nucleating ability of PB, and the melting behavior of the PLLA/2%PB sample under different conditions evidenced the competitive relationship between the nucleation effect of PB and heating rate, the nuclear rate and the crystal growth rate for melting behavior of PLLA/PB. The presence of PB did not change the thermal decomposition behavior of PLLA, however, PB with the concentration of 1 wt%–2 wt% could improve the thermal stability of PLLA, resulting from the interaction between PLLA and PB.

Funding source: National Natural Science Foundation of China

Award Identifier / Grant number: 51403027

Funding source: Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences

Award Identifier / Grant number: R2013CH11

Funding statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (project number 51403027), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (project number cstc2015jcyjBX0123), Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (project number KJ131202) and Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences (project number R2013CH11).

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (project number 51403027), Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (project number cstc2015jcyjBX0123), Scientific and Technological Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (project number KJ131202) and Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences (project number R2013CH11).

References

1. Wang HL, Liu H, Chu CJ, She Y, Jiang SW, Zhai LF, Jiang ST, Li XJ. Diffusion and antibacterial properties of nisin-loaded chitosan/poly(L-lactic acid) towards development of active food packaging film. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2015;8(8):1657–67.10.1007/s11947-015-1522-zSearch in Google Scholar

2. Wang YH, Xu XL, Dai J, Yang JH, Huang T, Zhang N, Wang Y, Zhou ZW, Zhang JH. Super toughened immiscible polycarbonate/poly(L-lactide) blend achieved by simultaneous addition of compatibilizer and carbon nanotubes. RSC Adv. 2014;4(103):59194–203.10.1039/C4RA11282BSearch in Google Scholar

3. Garcia AM, Garcia Al, Cabezas ML, Reche AS. Study of the influence of the almond variety in the properties of injected parts with biodegradable almond shell based masterbatches. Waste Biomass Valor. 2015;6(3):363–70.10.1007/s12649-015-9351-xSearch in Google Scholar

4. Mattana G, Briand D, Marette A, Quintero AV, de Rooij NF. Polylactic acid as a biodegradable material for all-solution-processed organic electronic devices. Org Electron. 2015;17: 77–86.10.1016/j.orgel.2014.11.010Search in Google Scholar

5. Yan SF, Yin JB, Yang Y, Dai ZZ, Ma J, Chen XS. Surface-grafted silica linked with L-lactic acid oligomer: a novel nanofiller to improve the performance of biodegradable poly(L-lactide). Polymer. 2007;48:1688–94.10.1016/j.polymer.2007.01.037Search in Google Scholar

6. Liu ZW, Luo YL, Bai HW, Zhang Q, Fu Q. Remarkably enhanced impact toughness and heat resistance of poly(L-Lactide)/thermoplastic polyurethane blends by constructing stereocomplex crystallites in the matrix. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;4(1):111–20.10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00816Search in Google Scholar

7. Wang HF, Wu C, Liu X, Sun J, Xia GM, Huang W, Song R. Enhanced mechanical and thermal properties of poly(L-lactide) nanocomposites assisted by polydopamine-coated multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Colloid Polym Sci. 2014;292(11):2949–57.10.1007/s00396-014-3350-5Search in Google Scholar

8. Ye HM, Hou K, Zhou Q. Improve the thermal and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide) by forming nanocomposites with pristine vermiculite. Chin J Polym Sci. 2016;34(1):1–12.10.1007/s10118-016-1724-5Search in Google Scholar

9. Papageorgiou GZ, Terzopoulou Z, Bikiaris D, Triantafyllidis KS, Diamanti E, Gournis D, Klonos P, Giannoulidis E, Pissis P. Evaluation of the formed interface in biodegradable poly(L-lactic acid)/graphene oxide nanocomposites and the effect of nanofillers on mechanical and thermal properties. Thermochim Acta. 2014;597:48–57.10.1016/j.tca.2014.10.007Search in Google Scholar

10. Liu MH, Yin Y, Wei W, Zheng CB, Shen S, Deng PY, Zhang WX. Effects of radiation-induced crosslinking on thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid) composites reinforced by basalt fiber. Nucl Sci Tech. 2013;24:S010313.Search in Google Scholar

11. Zhang XQ, Meng LY, Li G, Liang NM, Zhang J, Zhu ZG, Wang R. Effect of nucleating agents on the crystallization behavior and heat resistance of poly(L-lactide). J Appl Polym Sci. 2016;133(8):42999.10.1002/app.42999Search in Google Scholar

12. Shi XT, Zhang GC, Phuong TV, Lazzeri A. Synergistic effects of nucleating agents and plasticizers on the crystallization behavior of poly(lactic acid). Molecules. 2015;20:1579–93.10.3390/molecules20011579Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Fukushima K, Tabuani D, Arena M, Gennari M, Camino G. Effect of clay type and loading on thermal, mechanical properties and biodegradation of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites. React Funct Polym. 2013;73(3):540–9.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2013.01.003Search in Google Scholar

14. Souza DHS, Andrade CT, Dias ML. Isothermal crystallization kinetics of poly(lactic acid)/synthetic mica nanocomposites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2014;131(11):40322.10.1002/app.40322Search in Google Scholar

15. Li YH, Chen CH, Li J, Sun XZS. Isothermal crystallization and melting behaviors of bionanocomposites from poly(lactic acid) and TiO2 nanowires. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;124(4):2968–77.10.1002/app.35326Search in Google Scholar

16. Zhao Y, Liu B, You C, Chen MF. Effects of MgO whiskers on mechanical properties and crystallization behavior of PLLA/MgO composites. Mater Des. 2016;89:573–81.10.1016/j.matdes.2015.09.157Search in Google Scholar

17. Han LJ, Han CY, Bian JJ, Bian YJ, Lin HJ, Wang XM, Zhang HL, Dong LS. Preparation and characteristics of a novel nano-sized calcium carbonate (nano-CaCO3)-supported nucleating agent of poly(L-lactide). Polym Eng Sci. 2012;52(7):1474–84.10.1002/pen.23095Search in Google Scholar

18. Su ZZ, Huang K, Lin MS. Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/modified carbon black composite. J Macromol Sci B. 2012;51(8):1475–84.10.1080/00222348.2011.632741Search in Google Scholar

19. Kim SY, Shin KS, Lee SH, Kim KW, Youn JR. Unique crystallization behavior of multi-walled carbon nanotube filled poly(lactic acid). Fibers Polym. 2010;11(7):1018–23.10.1007/s12221-010-1018-4Search in Google Scholar

20. He DR, Wang YM, Shao CG, Zheng GQ, Li Q, Shen CY. Effect of phthalimide as an efficient nucleating agent on the crystallization kinetics of poly(lactic acid). Polym Test. 2013;32:1088–93.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2013.06.005Search in Google Scholar

21. Tang ZB, Zhang CZ, Liu XQ, Zhu J. The crystallization behavior and mechanical properties of polylactic acid in the presence of a crystal nucleating agent. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;125:1108–15.10.1002/app.34799Search in Google Scholar

22. Harris AM, Lee EC. Improving mechanical performance of injection molded PLA by controlling crystallinity. J Appl Polym Sci. 2008;107(4):2246–55.10.1002/app.27261Search in Google Scholar

23. Qi ZF, Yang Y, Xiong Z, Deng J, Zhang RY, Zhu J. Effect of aliphatic diacyl adipic dihydrazides on the crystallization of poly(lactic acid). J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132:42028.10.1002/app.42028Search in Google Scholar

24. Bai HW, Huang CM, Xiu H, Zhang Q, Fu Q. Enhancing mechanical performance of polylactide by tailoring crystal morphology and lamellae orientation with the aid of nucleating agent. Polymer. 2014;55:6924–34.10.1016/j.polymer.2014.10.059Search in Google Scholar

25. Zou GX, Jiao QW, Zhang X, Zhao CX, Li JC. Crystallization behavior and morphology of poly(lactic acid) with a novel nucleating agent. J Appl Polym Sci. 2015;132(5):41367.10.1002/app.41367Search in Google Scholar

26. Xing Q, Li RB, Dong X, Luo FL, Kuang X, Wang DJ, Zhang LY. Enhanced crystallization rate of poly(l-lactide) mediated by a hydrazide compound: nucleating mechanism study. Macromol Chem Phys. 2015;216:1134–45.10.1002/macp.201500002Search in Google Scholar

27. Ma PM, Xu YS, Shen TF, Dong WF, Chen MQ, Lemstra PJ. Tailoring the crystallization behavior of poly(L-lactide) with self-assembly-type oxalamide compounds as nucleators: 1. Effect of terminal configuration of the nucleators. Eur Polym J. 2015;70:400–11.10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2015.07.040Search in Google Scholar

28. Cai YH, Zhao LS, Zhang YH. Role of N, N′-Bis(1H-benzotriazole) adipic acid acethydrazide in crystallization nucleating effect and melting behavior of poly(L-lactic acid). J Polym Res. 2015;22:246.10.1007/s10965-015-0887-zSearch in Google Scholar

29. Cai YH, Zhao LS. An investigation of the effect of chitosan on isothermal crystallization, thermal decomposition, and melt index of biodegradable poly(L-lactic acid). Int J Polym Sci. 2015;2015:5.10.1155/2015/296380Search in Google Scholar

30. Fan YQ, Yu ZY, Cai YH, Hu DD, Yan SF, Chen XS, Yin JB. Crystallization behavior and crystallite morphology control of poly(L-lactic acid) through N, N′-bis(benzoyl)sebacic acid dihydrazide. Polym Int. 2013;62:647–57.10.1002/pi.4342Search in Google Scholar

31. Su ZZ, Guo WH, Liu YJ, Li QY, Wu CF. Non-isothermal crystallization kinetics of poly(lactic acid)/modified carbon black composite. Polym Bull. 2009;62:629–42.10.1007/s00289-009-0047-xSearch in Google Scholar

32. Cai YH, Zhang YH. The crystallization, melting behavior, and thermal stability of poly(L-lactic acid) Induced by N, N, N′-tris(benzoyl)trimesic acid hydrazide as an organic nucleating agent. Adv Mater. Sci Eng. 2014;2014:8.10.1155/2014/843564Search in Google Scholar

33. Yan YQ, Zhu J, Yan SF, Chen XS, Yin JB. Nucleating effect and crystal morphology controlling based on binary phase behavior between organic nucleating agent and poly(L-lactic acid). Polymer. 2015;67:63–71.10.1016/j.polymer.2015.04.062Search in Google Scholar

34. Yasuniwa M, Tsubakihara S, Sugimoto Y, Nakafuku C. Thermal analysis of the double-melting behavior of poly(L-lactic acid). J Polym Sci, Part B: Polym Phys. 2004;42(1):25–32.10.1002/polb.10674Search in Google Scholar

35. Cai YH, Yan SF, Fan YQ, Yu ZY, Chen XS, Yin JB. The nucleation effect of N, N′-bis(benzoyl) alkyl diacid dihydrazides on crystallization of biodegradable poly(L-lactic acid). Iran Polym J. 2012;21:435–44.10.1007/s13726-012-0046-xSearch in Google Scholar

36. Zuo YF, Gu JY, Zhang YH, Wu YQ. Effect of plasticizer types on the properties of starch/polylactic acid composites. J Func Mater. 2015;46:6044–48 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

37. Liao YZ, Xin MH, Li MC. Hydrogen-bonding interactions and miscibility in N, N-dilauryl chitosan/poly(L-lactide) blend membranes by solution approach. Chem Ind Eng Prog. 2007;26(5):72530 (In Chinese).Search in Google Scholar

38. Cai YH, Zhao LS. The interaction of poly(L-lactic acid) and the nucleating agent N, N′-bis(benzoyl) suberic acid dihydrazide. Polimery. 2015;60(11–12):693–9.10.14314/polimery.2015.693Search in Google Scholar

©2016 by De Gruyter

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Full length articles

- Preparation of rigid polyurethane foams using low-emission catalysts derived from metal acetates and ethanolamine

- Biodegradation of crosslinked polyurethane acrylates/guar gum composites under natural soil burial conditions

- Influence of phthalocyanine pigments on the properties of flame-retardant elastomeric composites based on styrene-butadiene or acrylonitrile-butadiene rubbers

- Synthesis and properties of low coefficient of thermal expansion copolyimides derived from biphenyltetracarboxylic dianhydride with p-phenylenediamine and 4,4′-oxydialinine

- Thermal behavior of modified poly(L-lactic acid): effect of aromatic multiamide derivative based on 1H-benzotriazole

- Functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions

- Effect of oil palm ash on the mechanical and thermal properties of unsaturated polyester composites

- Effect of carbon sources on physicochemical properties of bacterial cellulose produced from Gluconacetobacter xylinus MTCC 7795

- Investigation into the effect of the angle of dual slots on an air flow field in melt blowing via numerical simulation

- Simulation study on the assembly of rod-coil diblock copolymers within coil-selective nanoslits

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Full length articles

- Preparation of rigid polyurethane foams using low-emission catalysts derived from metal acetates and ethanolamine

- Biodegradation of crosslinked polyurethane acrylates/guar gum composites under natural soil burial conditions

- Influence of phthalocyanine pigments on the properties of flame-retardant elastomeric composites based on styrene-butadiene or acrylonitrile-butadiene rubbers

- Synthesis and properties of low coefficient of thermal expansion copolyimides derived from biphenyltetracarboxylic dianhydride with p-phenylenediamine and 4,4′-oxydialinine

- Thermal behavior of modified poly(L-lactic acid): effect of aromatic multiamide derivative based on 1H-benzotriazole

- Functionalized magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions

- Effect of oil palm ash on the mechanical and thermal properties of unsaturated polyester composites

- Effect of carbon sources on physicochemical properties of bacterial cellulose produced from Gluconacetobacter xylinus MTCC 7795

- Investigation into the effect of the angle of dual slots on an air flow field in melt blowing via numerical simulation

- Simulation study on the assembly of rod-coil diblock copolymers within coil-selective nanoslits