Abstract

In the literature several models have been derived by different authors in order to predict the solar irradiance intensity over inclined surfaces, however for the most models accuracy at various inclinations have not been verified. The study evaluated the estimation of solar irradiance at different tilt angles by means of different models based on the experimental measurements. For this purpose, two groups of models (isotropic and anisotropic) were carried out: the first group of models was used for estimating the diffuse solar irradiance component, and the second group was used for estimating the global solar irradiance. Five models have been selected and implemented for the estimation of the diffuse solar irradiance component, and five models have been selected for the estimation of global solar irradiance. The results of the analysis were compared with local experimental measurements for diffuse radiation and global irradiance. There are three tilt angles (0°, 30°, 60°) and a two-axis tracking system has been determent for comparison experiments with the model estimated results. The results showed all the selected models generated an error percentage in both the diffuse and global irradiance investigations.

Introduction

Due to the increasing demand for energy, renewable energy has become increasingly popular. Solar energy has been considered one of the key sources of renewable energy. It can be used directly in the solar collector to heat domestic water, or it can be converted into the most desired form of energy – electrical energy – in photovoltaic (PV) modules and other devices. The energy from the sun reaches the earth surfaces in two ways: directly from the sun without changing direction, or indirectly through air scattering. Climatologists use a variety of techniques to determine irradiance, depending on the kind of solar radiation they are attempting to estimate for the purpose of designing and optimizing solar energy technology, including pyranometers, pyrheliometers, and sunlight recorders. There are three main types of solar radiation: diffuse radiation, direct radiation, and reflected radiation (Duffie, Beckman, and Blair 2020). The intensity of diffuse and total (global) solar radiation is measured on horizontal surfaces, while the intensity of direct (beam) solar radiation is measured in the sun direction. Data on solar radiation is also crucial in designing solar technologies and techniques. Modeling and simulation of solar systems require accurate solar radiation data for performance evaluation (Hassan et al. 2016). Due to the difficulty of measuring diffuse solar radiation and solar radiation beams, most meteorological stations provide a measurement of the global irradiation on the horizontal plane (GHI) only (Yao et al. 2014), but the real solar collectors or PV modules are almost always inclined. The solar components are required in order to evaluate solar radiation incident on the inclined surface. For this reason, many semi-empirical models have been proposed which are capable of estimating solar components on the basis of GHI measurement or on the basis of weather prediction only (Marques Filho et al. 2016). In the literature, there are several studies concentrating on modeling the global solar radiation incident on the oblique surface. Pandey and Katiyar (2009) presented a comparative study of the diffuse component of solar radiation on the oblique surface with a different-angle of inclination for the northern Indian region, and the results show that the Klucher model has a very low percentage error – less than 7% for all inclination angles compared with other models. An analysis using different diffuse solar radiation models for the evaluation of solar energy resources and for the acquisition of an optimum tilt angle depending on diffuse and direct solar radiation for a prospective location in the southern region of Sindh, Pakistan was conducted in (Khahro et al. 2015). The results show that the optimum tilt angle was for spring 21°, summer 0°, autumn 18°, and winter 46°. Kaushika, Tomar, and Kaushik (2014) used an artificial neural network (ANN) model for the estimation of solar radiation components on horizontal and inclined surfaces. Direct solar radiation was estimated by eliminating diffuse solar radiation from global solar radiation. The results obtained were compared to NASA surface meteorological and solar energy, and the set demonstrates a high degree of congruence. An analysis conducted by Padovan and Del Col (2010) demonstrate that an anisotropic model, based on a physical description of diffuse radiation, provides significantly more accurate measurements of global and diffuse solar irradiance on a horizontal and different-angle oblique surface compared to one isotropic and three anisotropic transposition models. In Posadillo and Luque (2009), three distinct models for estimating diffuse solar radiation on an oblique surface were analyzed, as well as methods for calculating beam and ground reflected radiation on an oblique surface. The models showed an underestimation in the calculation of the solar radiation on the inclined surface. The isotropic model behaved worst, while the analyzed anisotropic models performed similarly, and in general better. The establishment of a diffuse solar radiation model for determining the optimum tilt angle of solar surfaces based on a clearness index and relative sunshine duration was carried out in Khorasanizadeh, Mohammadi, and Mostafaeipour (2014). On the basis of the measured data of GHI and DHI for the period (1996–2007), a new correlation has been proposed (El-Sebaii et al. 2010) for the calculation of diffuse radiation incident on horizontal surfaces.

In general, the models for diffuse solar radiation proposed in the literature can be divided into two main categories: linear models (Soares et al. 2004) and polynomial models (Shukla, Rangnekar, and Sudhakar 2015). An interesting study using various empirical models for estimation of solar radiation on an oblique surface based on the average monthly mean value of solar radiation on a daily basis in Bhopal, India was done by K.N. Shukla, Rangnekar, and Sudhakar (2015). The results show that the Hays and Davis models estimated the highest amount of incident solar radiation compared to the other models. Teke, Yıldırım, and Çelik (2015) Demain classified the solar energy modeling techniques as linear, nonlinear, fuzzy logic, and artificial intelligence for estimating solar radiation. According to the proposed classification, the most correlated parameters for solar radiation estimation are sunshine duration, relative humidity, air temperature, solar measuring data measuring time intervals, and geographical parameters such as longitude, latitude, and altitude. Demain, Journée, and Bertrand (2013) evaluate the performance of 14 models transposing 10 min of diffuse irradiation from a horizontal to an inclined surface. The evaluations show that models have widely varied performance according to the sky conditions, and there are large variations for intermediate sky conditions compared to the clear or overcast conditions.

Manju and Sandeep (2019) designed and performed a performance evaluation of a solar PV/thermal system for the estimation of global solar radiation. The new generalized models were developed to estimate the monthly average global solar radiation of 12 Indian regions. The authors used solar radiation data supplied by the World Radiation Data Center (WRDC) for the period of 2000–2014. A statistical study was performed to evaluate the accuracy of the model used to predict global solar radiation, which includes mean bias error, root mean square error, coefficient of determination, mean absolute percentage error, and uncertainty at 94%. As a result, in the lack of measurable data, modeling is a feasible alternative for obtaining solar radiation with projected climatic conditions (Santhakumari and Sagar 2019). By monitoring solar radiation and combining it with geographical and climatic data, researchers have constructed a variety of empirical models. The global and diffuse solar radiation measurements were taken on four vertical surfaces exposed to the north, east, south, and west at Arcavacata di Rende, Italy, as presented by Cucumo et al. (2009). The article presents the mean hourly values of global and diffuse radiation effectiveness that were evaluated for a one-year span. The hourly data was compared to the predictions of several computation models. The comparisons reveal that the discrepancies between the various models for global efficacy are not substantial, and that using a model with a constant value of efficacy produces good forecasts of global radiation. The results demonstrated a new model for the prediction of global and diffuse radiation with an accuracy of 93%. Wu et al. (2021) analyze the potential for global and diffuse solar radiation using Bayesian additive regression trees (BART). The research gathered long-term daily experimental data at four locations in dry and humid climates. Were constructed models with a variety of input combinations and used the Taylor diagram to illustrate performance. The results demonstrated the development of a novel model for forecasting global and diffuse solar radiation using a variety of meteorological variables, including sunlight duration, theoretical sunshine duration, mean temperature, maximum temperature, minimum temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall. BART was determined to be an appropriate approach for measuring global and diffuse solar radiation using climatic factors.

Wang et al. (2018) calibrate and evaluate a simple model for estimating diffuse solar radiation across daily and monthly time frames for Chinese territory. The proposed approach was carried out by utilizing experimental data from the 13th weather station in China. The results showed that the daily approach may be used consistently, but the monthly approach was only effective in the southern region. Using its regional characteristics, the northern region monthly approach was modified. The methods developed can successfully estimate diffuse radiation and are highly applicable in engineering for only two factors, with correct results being provided for all stations. Marques Filho et al. (2016) assessed the intensity of solar radiation in Rio de Janeiro. The main purpose is to monitor the evolution of the solar radiation components (global and diffuse) for the chosen city. For several years, the evolution method was tested using experimental solar radiation data. The study found a significant potential for solar energy at the surface, particularly during the summer. The clearness index and the diffuse solar radiation portion behave similarly in summer and winter. The Angstrom formula accurately represents the monthly average daily value of global solar radiation. In terms of representing the diffuse percentage as a function of the clearness index, the sigmoid logistic function is statistically more significant than other correlation models. Li, Lou, and Lam (2015) examines horizontal global, direct, and sky-diffuse solar radiation data recorded in Hong Kong between 2008 and 2012, summarizes some of the general findings, assesses a mathematical model for estimating direct-normal solar radiation, and computes several climatic variables. The results might contribute to the development of a more trustworthy and complete solar radiation database for future building energy designs and evaluations.

Hassan et al. (2021) estimated the intensity of solar radiation for the region of Iraq. The study was carried out using 15 years of experimental data for solar radiation. The results suggest a polynomial model for predating the optimum tilt angel for maximizing solar radiation for the Iraqi territories. Kaushika, Tomar, and Kaushik (2014) used ANNs to obtain an explicit approach used for the decomposition of solar radiation components directly. The selected computing algorithm estimates global, diffuse, and direct components under clear sky conditions. The differences between these estimations and experimental measurements are mainly caused by random meteorological occurrences described by clearness indexes. In the ANN analysis, the clearness indices and their corresponding solar radiation components are mapped with long-term monthly mean hourly data of weather-related parameters such as mean duration of sunshine per hour, relative humidity, and total rainfall. A comparison of the current ANN approach estimations with NASA meteorology and solar energy data sets reveals good agreement. The worldwide solar radiation on slanted planes was also studied under isotropic and anisotropic sky conditions. The relationship between global, direct, and diffuse solar radiation with regard to optical air mass is used to evaluate the attenuation induced by situational factors evaluated by Dal Pai et al. (2014). The results demonstrated that the decrease in solar radiation with increasing optical air mass was justified by an increase in the chance of solar ray collision with atmospheric elements. The combined study of data from direct and diffuse solar radiation allows for a better understanding of the atmospheric attenuation process, establishing qualitative correlations between absorption, scattering, and reflection processes.

Sanchez-Lorenzo, Calbó, and Wild (2013) present a full description dataset of surface solar radiation in Spain based on the longest series of global solar radiation measurements, most of which began in the early 1980s. In this work the homogeneity of this dataset is particularly important in order to assure the dependability of the trends, which might be altered by non-natural phenomena such as relocations or instrument modifications. Rossi et al. (2018) describe several correlations for solar radiation decomposition components (global, diffuse, and direct). The study presented a database of global solar radiation from three years in Botucatu, Brazil. Furthermore, the influence of climate parameters (cloudiness, water vapor, and aerosols) on the irradiance was evaluated. The Earth obtains the preponderance of its energy in the form of electromagnetic solar radiation. The atmospheric components absorb, reflect, and transmit some of this radiation. The magnitude of solar irradiance fluxes anywhere at site on the Earth is determined by a number of meteorological, astronomical, and geographical parameters, including cloudiness, solar constant, solar elevation, Sun-Earth distance, albedo at ground, sunshine duration, day length, air temperature, relative humidity, precipitation, and coefficients of absorption and diffusion by atmospheric components. Other factors relating to the prediction of solar radiation have been extensively discussed in the literature.

The man objective of the research is to create and evaluate empirical models using newly calculated correlation coefficients for sunlight hours in Polish regions. The study aids in the selection of the best model for each location from a pool of all examined models in order to forecast daily global solar radiation. A detailed statistical analysis was conducted utilizing quantitative statistical indicators to evaluate solar radiation models. Additionally, a global performance indicator was created to rank models based on scaled values of statistical markers. The evaluation process conducted two different types of modeling for the purpose: the first group consists of five different models which are used for estimating the diffuse solar radiation on the basis of information about global solar radiation on a horizontal surface, and the second group of models is used for the estimation of the global solar radiation incident on an inclined surface. This part will be done using six different empirical models: three isotropic models and three anisotropic models. The research novelty is that the accuracy of these models has been determined and evaluated for a number of inclination degrees (0°, 30°, 60°). Additionally, to assess the day-to-day performance of these models, a statistical analysis was conducted utilizing a variety of statistical indicators in order to develop a model for estimating diffuse solar irradiance for the selected site based on experimental data.

Modeling and case of study

Monthly averages of daily solar irradiation on tilted surfaces are essential for various solar energy applications. Solar radiation data at the horizontal surface is generally always accessible for every location. The following summarizes the governing equations for forecasting solar energy.

Solar declination (δ)

The solar declination varies between 23°27 and −23°27 during the winter and summer solstices, and it can be determined for any day n of the year using Cooper (1969) equation (Hassan 2022):

Coordinates in space and time

The latitude and longitude (degrees) of a point on Earth, as well as the altitude z (m) used to indicate the geographical coordinates of that location. Calculate the hour angle (degrees) as follows (Ceran et al. 2021):

where ts is the solar time calculated from the civil local time ts as:

where λ is the longitude in degree, Zc represents the time zone in hours east of GMT and E denotes the time equation, as follows (Jaszczur et al. 2021):

B is calculated based on the day of the year n:

Sun elevation and solar angles

The Sun elevation α (degrees −180°≤ α ≤ 180°) can be calculated by the following formula:

Sun azimuth γ (degrees −180° ≤ γ ≤ 180°) can be determinate as:

where zenith angle θΖ (degrees) can be calculated as:

The incidence angle θ (degrees) is given by:

where β is the slope of the surface (solar panel or PV module).

Extraterrestrial solar radiation

The extraterrestrial normal solar radiation Gon (kW/m2) can be calculated using solar constant Gsc (1.367 kW/m2) and day n of the year (Abbas et al. 2021; Jaszczur et al. 2018):

The horizontal extraterrestrial radiation Go (kW/m2) can determine as:

Diffuse radiation

At each simulation time step, the value of clearness can be expressed as follows:

The global horizontal radiation G consists of two main parts: beam radiation Gb and diffuse radiation Gd. The diffusive radiation component comes equally from almost all the directions and it consists of up to three components (isotropic, circumsolar, and horizon brightening).

The surface position has a direct effect on the beam radiation, but it is negligible in comparison to the diffuse radiation that comes from numerous directions; in actuality, some models assume that it is direction-independent. In most situations, the only global horizontal (total) solar radiation is measured at a given site. The decomposition of the solar radiation components will be used with the five different models presented in Table 1 which utilize the clearness kt or clearness and sun elevation α as a model parameter.

Diffuse part solar radiation models.

| Author | Model (13) |

|---|---|

| Erbs model (Erbs, Klein, and Duffie 1982) |

|

| Orgill and Holands model (Lam and Li 1996) |

|

| Reindl model (Reindl, Beckman, and Duffie 1990) |

|

| Madrid 1 model (Mario 1994) |

|

| Madrid 2 model (Mario 1994) |

|

Incident solar radiation

Direct radiation, diffuse radiation, and reflected radiation make up the total incident solar irradiance on the tilted surface. The diffuse radiation may have up to three components (isotropic, circumsolar, and horizon brightening), whereas the reflected radiation is the light reflected from the earth and surfaces around it. In this research, six alternative models for estimating incident solar irradiance at arbitrarily oriented surfaces are presented in Table 2.

where ρ is the ground reflectance (Albedo), f is the horizon brightening factor, Ai is the anisotropy index and Rb is the ratio of beam radiation on the inclined surface and horizontal surface:

The incidents solar irradiance models.

| Author | Model (14) |

|---|---|

| Liu and Jordan model (1963) (LeBaron and Dirmhirn 1983) |

|

| Koronakis model (1986) (Koronakis 1986) |

|

| Badescu model (2002) (Badescu 2002) |

|

| Hay and Davies model (1981) (Hay and McKAY 1985) |

|

| Reindl et al. Model (1990) (Reindl, Beckman, and Duffie 1990) |

|

| HDKR model (2006) (Erbs, Klein, and Duffie 1982) |

|

Measurement data and a mathematical model

The measurement data of global G and diffuse Gd solar radiation at a horizontal surface was performed by means of two types of pyranometers (Kipp and Zonen CM 21): the first set measured global solar radiation and the second set measured diffuse solar radiation, both located at the AGH University of Science and Technology campus, Kraków, Poland (50.0647°N, 19.9450°E). The pyranometers were equipped with CV2 ventilation units and located on the EKO STR-22 Sun-tracker. Measurements were made every second and then averaged over 5 min and recorded by the COMBILOG 1200 datalogger (Theodor Friedrich).

Results and discussion

Estimation of the diffuse solar radiation Gd

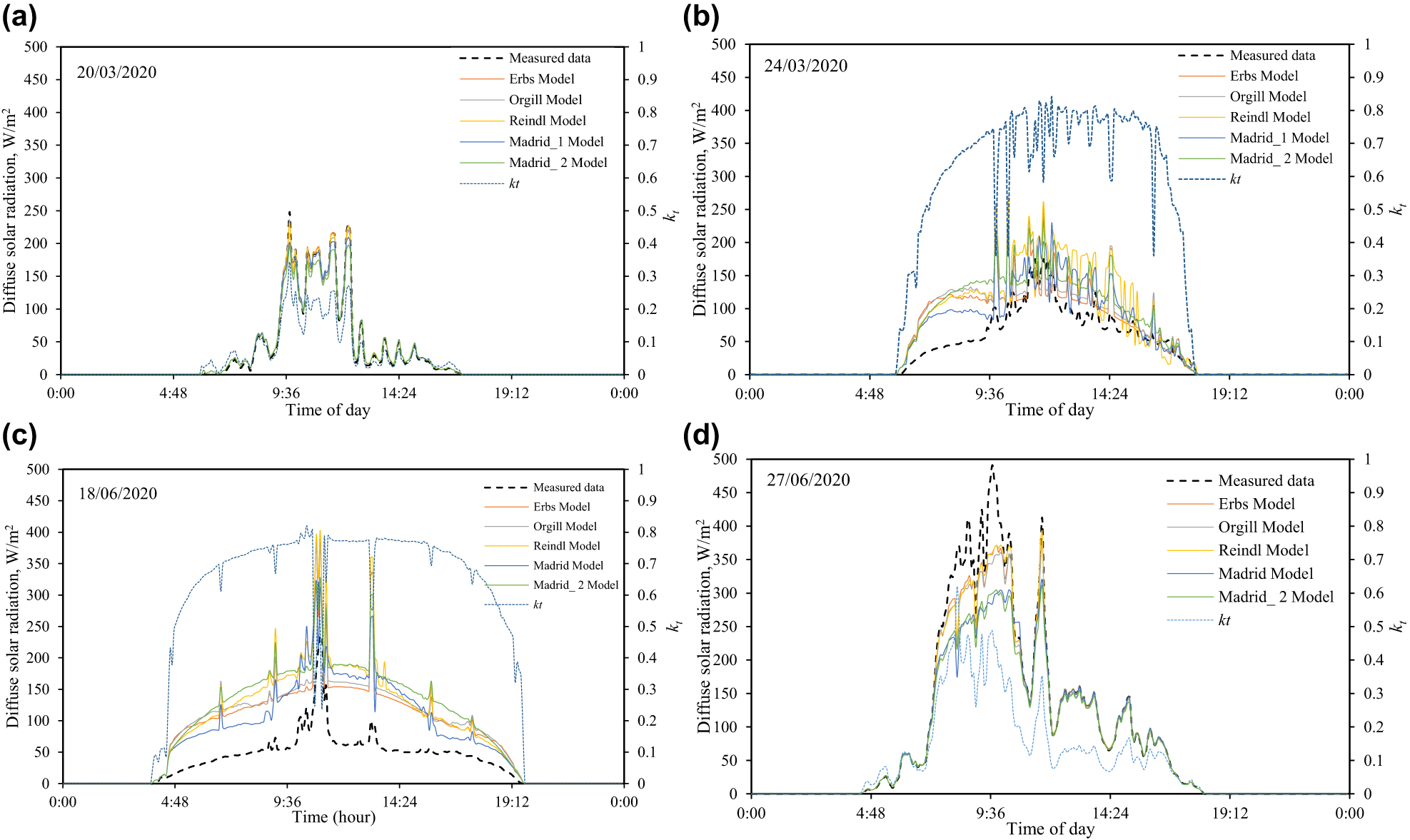

In Figure 1a–d, the comparison of diffuse solar radiation Gd obtained using five mathematical models presented in Table 1 with diffuse irradiation experimental measurement data for six different days representing different seasons of the year 2016 was presented. The results indicated that on cloudy days (low clearance index), almost identical readings are obtained, whereas on sunny days (high clearance index), there is a large discrepancy between all the results. The model Madrid_1 prediction has the smallest discrepancy. However, for almost all parts of the day, the solar radiation Gd is overpredicted. This model was adopted on the basis of measuring solar radiation in Spain, which is considered to be the most accurate for Kraków, while other models have been built based on solar radiation data for different sites on the Earth. The model Madrid_1 will be used to estimate the incident solar radiation in the second part of this paper as the most accurate model.

Solar radiation Gd (diffuse part) calculated with different models and clearness index kt. (a) March 20, (b) March 24, (c) June 18 and (d) June 27 of the year 2020.

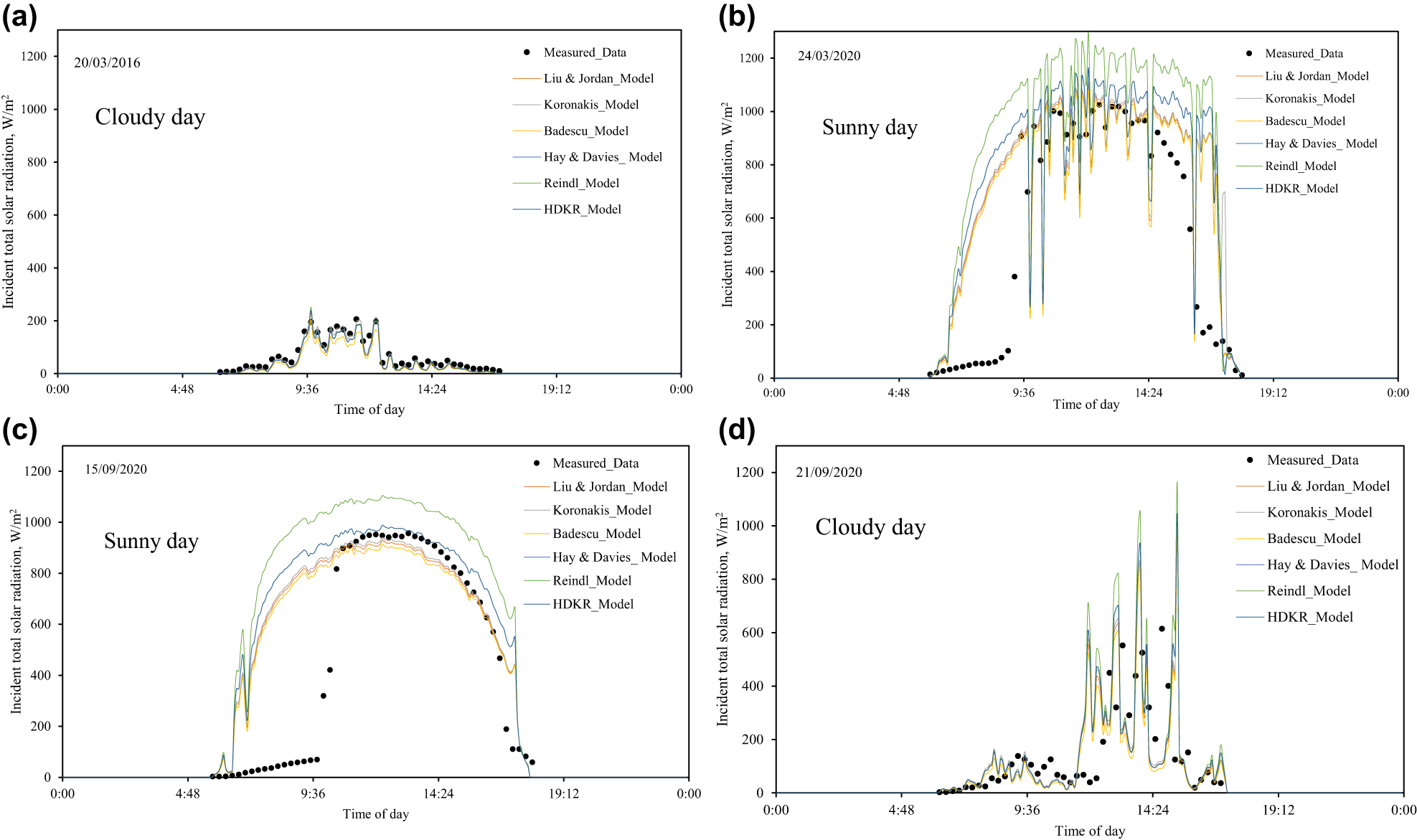

Estimation the incident total solar radiation GT

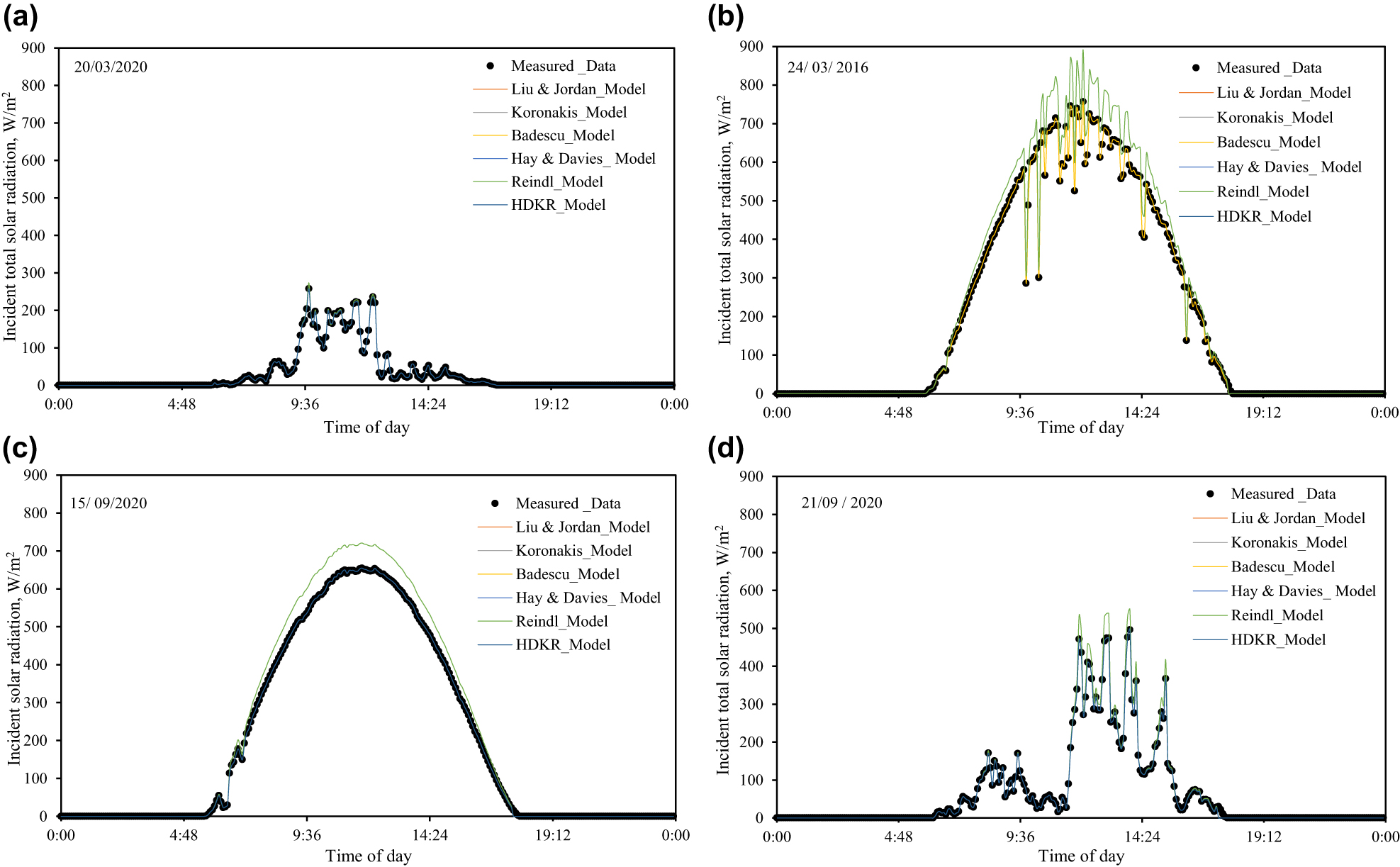

In this section, the incident solar radiation hits a horizontal surface (β = 0°), two inclined surfaces (γ = 20° and β = 30°), and a surface equipped with the two-axis tracking system. For this calculation, the six different models presented in Table 2 have been compared with each other and with the incident solar radiation experimental measurement. It was assumed that the ground reflectance was 0.2. Four different days of the year were selected, representing various types of weather.

The incident total solar radiation GT on a horizontal surface (β = 0°) is presented and compared with experimental measurements in Figure 2a–d. It was revealed that the Hay and Davies model and Reindl et al. model are not consistent and overpredict GT, whereas all other models predict the same value as the input data value. In the case of β = 0 and no additional reflectance (as in a horizontal case), G should be equal to GT. That is more pronounced on clear days, but the difference is always recorded.

The incident solar radiation GT on a horizontal surface (β = 0ο). (a) March 20, (b) March 24, (c) September 15 and (d) September 21 of the year 2020.

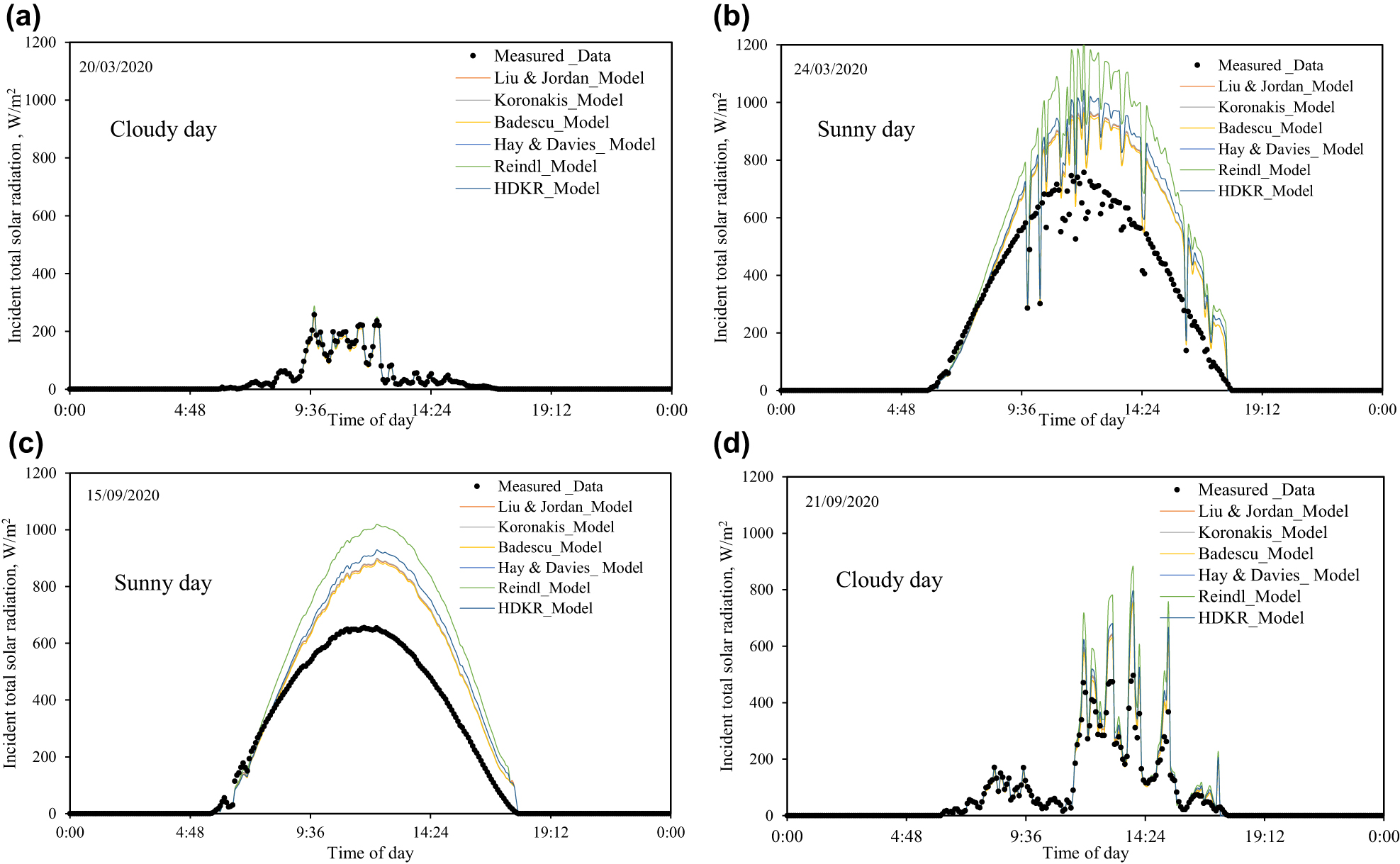

The numerical results for the surfaces inclined (γ = 20°, β = 30°) are presented in Figure 3a–d. As before, the Hay-Davies model and the Reindl et al. model predict the highest value of incident radiation GT in a similar manner, while the HDKR model predicts a slightly lower value. The models Liu and Jordan, Badescu, and Koronakisi predict very similarly, but their value is the lowest when compared to the other models. For clear days, all models predict the solar radiation GT at about 10–40% higher than the experimental measurement (β = 0°).

The incident solar radiation GT on an inclined surface (γ = 20ο, β = 30ο). (a) March 20, (b) March 24, (c) September 15 and (d) September 21 of the year 2020.

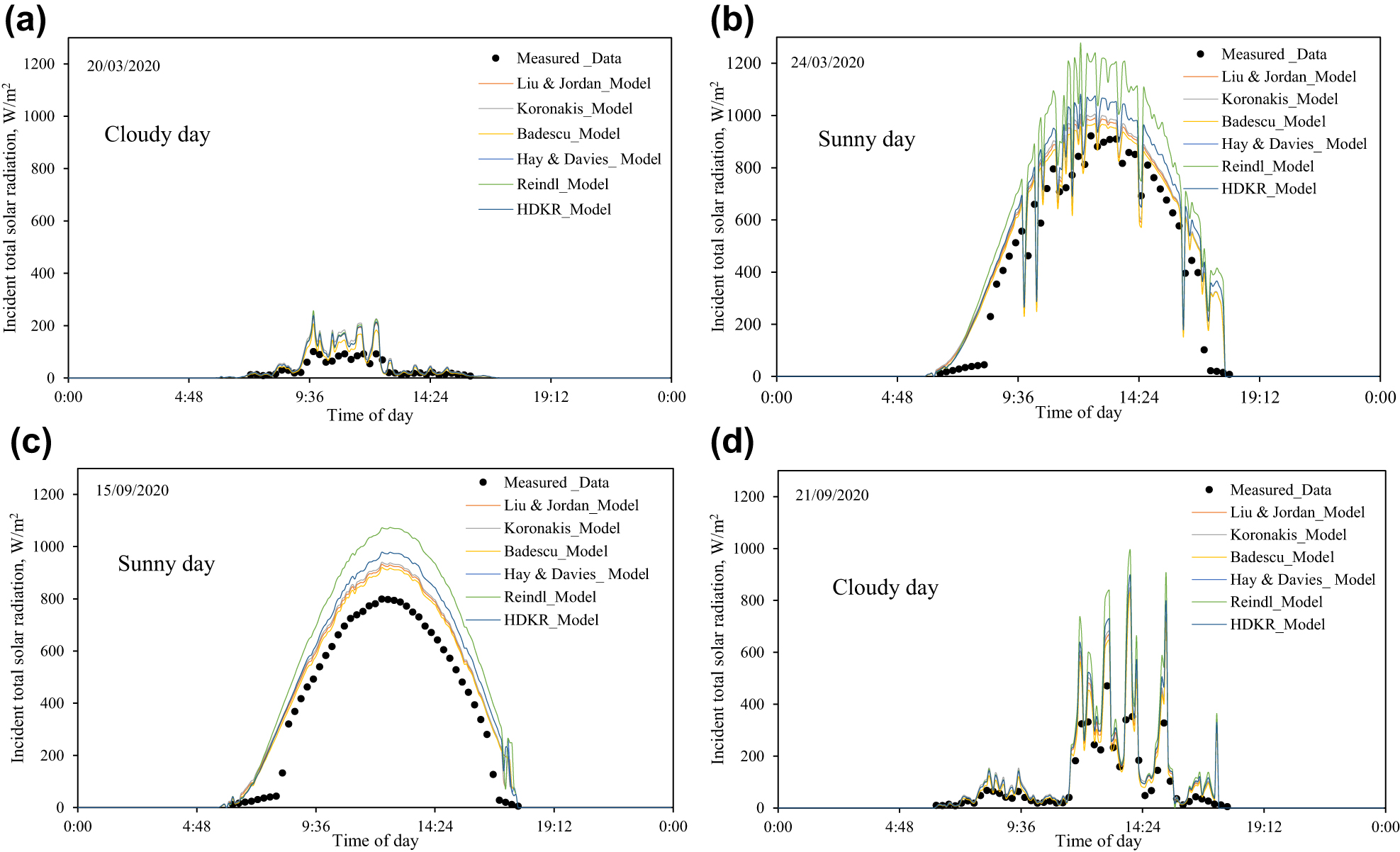

The results for the surfaces inclined (γ = 20°, β = 60°) are presented in Figure 4a–d. This angle is close to the optimal angle for Kraków. The models performed similarly, but the model values for clear days were significantly overpredicted in reference to the experimental measurement.

The incident solar radiation GT on an inclined surface (γ = 20ο, β = 60ο). (a) March 20, (b) March 24, (c) September 15 and (d) September 21 of the year 2020.

A tracking system is typically used in order to achieve maximum absorbance of incident solar radiation. In this part, experimental measurements of incident irradiation performed on the two-axis tracking system have been compared with numerical results. In this tracking system, both angles (γ and β) were not fixed but varied, following the sun position. It can be seen from Figure 5a–d that for cloudy days, all models performed similarly, whereas for clear days, Hay and Davis and Reindl et al. models overpredict experimental measurements. It has to be noticed that due to modules’ shadowing, measured incident solar radiation is much lower until about 10 a.m. than model predictions.

The incident solar on oblique with two-axis tracking system. March 20, (b) March 24, (c) September 15 and (d) September 21 of the year 2020.

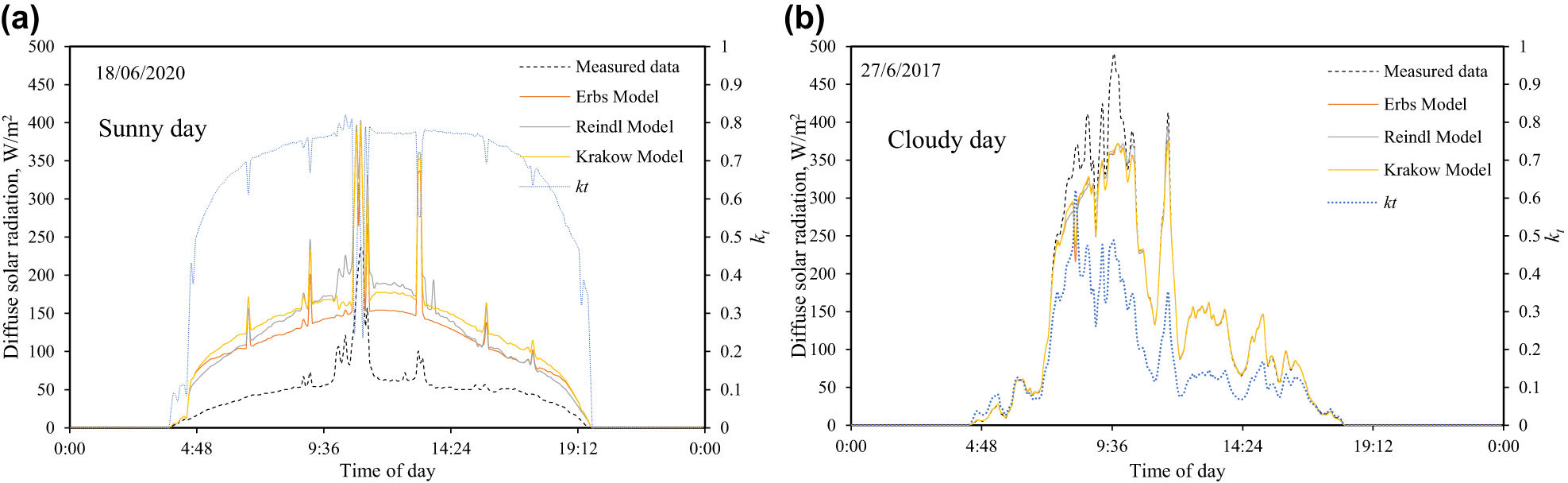

Diffuse correlation for Krakow

On the basis of long-period data for Poland (Polish ministry of energy), the local model for diffusive radiation estimation (Eq. (13)) has been proposed. In Figure 6a and b, diffuse solar radiation is presented, including a new correlation. It can be seen that the new correlation based on the local data gives values similar to the values predicted using other models, and for clear days, the discrepancy in reference to the experimental measurement is still significant.

Estimation the diffuse solar radiation with different and created model. (a) June 18 and (b) June 29 of the year 2020.

Conclusions

In the paper, estimation of the diffuse part of the total radiation based on the global solar radiation using five different models was conducted. Then the best model has been selected for use in the second part, which analyses the estimation of the incident solar radiation on an inclined surface using six isotropic and anisotropic models. All results are compared with each other as well as with the experimental measurements conducted for the horizontal surface, two inclined surfaces (γ = 20°, β = 30°), and two vertical surfaces (γ = 20°, β = 60°) and the two-axis tracking system. The results illustrate that the Madred_1 model is the most accurate in diffuse part estimation based on GHI measurement, and this model was selected for incident radiation calculation.

The models for the estimation of solar radiation show that incident solar radiation is higher when the surface is inclined, and the maximum irradiation is obtained for the two-axis tracking system. It was revealed that not all models are consistent and do not predict primary data if β = 0°. The isotopic models estimated lower solar radiation on cloudy days and executed higher results on sunny days, as shown in Figures 2–5. This may be so due to additional circumsolar components in the diffuse radiation fraction in these models, compared with isotropic models. The analysis shows that the Reindl et al. and Hay & Davies models predicted the highest values of solar radiation for all inclinations and for the tracking system among all isotropic and anisotropic sky models. This is due to individual consideration of diffuse components in the models and to the incorporation of a modulating factor which is multiplied by the horizon brightening term. The models proposed by Liu and Jordan, Badescu, and Koronakis predicted the lowest values; the Badescu model predicted the lowest value compared with isotropic and anisotropic models. This is due to the use of a cosine factor at the oblique angle, which produces a lower value of diffuse radiation. In conclusion, the isotopic models predict a higher value than anisotropic models in sunny weather and clear skies, but in any case, for clear days, all models overpredict experimental measurements.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Abbas, M. K., Q. Hassan, M. Jaszczur, Z. S. Al-Sagar, A. N. Hussain, A. Hasan, and A. Mohamad. 2021. “Energy Visibility of a Modeled Photovoltaic/diesel Generator Set Connected to the Grid.” Energy Harvesting and Systems, https://doi.org/10.1515/ehs-2021-0022.Search in Google Scholar

Badescu, V. 2002. “A New Kind of Cloudy Sky Model to Compute Instantaneous Values of Diffuse and Global Solar Irradiance.” Theoretical and Applied Climatology 72 (1): 127–36, https://doi.org/10.1007/s007040200017.Search in Google Scholar

Ceran, B., A. Mielcarek, Q. Hassan, J. Teneta, and M. Jaszczur. 2021. “Aging Effects on Modelling and Operation of a Photovoltaic System with Hydrogen Storage.” Applied Energy 297: 117161, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117161.Search in Google Scholar

Cooper, P. I. 1969. “The Absorption of Radiation in Solar Stills.” Solar Energy 12 (3): 333–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092x(69)90047-4.Search in Google Scholar

Cucumo, M., A. De Rosa, V. Ferraro, D. Kaliakatsos, and V. Marinelli. 2009. “Experimental data of global and diffuse luminous efficacy on vertical surfaces at Arcavacata di Rende and comparisons with calculation models.” Energy Conversion and Management 50 (1): 166–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2008.08.032.Search in Google Scholar

Dal Pai, A., J. F. Escobedo, D. Martins, and É. T. Teramoto. 2014. “Analysis of Hourly Global, Direct and Diffuse Solar Radiations Attenuation as a Function of Optical Air Mass.” Energy Procedia 57: 1060–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2014.10.091.Search in Google Scholar

Demain, C., M. Journée, and C. Bertrand. 2013. “Evaluation of Different Models to Estimate the Global Solar Radiation on Inclined Surfaces.” Renewable Energy 50: 710–21, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2012.07.031.Search in Google Scholar

Duffie, J. A., W. A. Beckman, and N. Blair. 2020. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes, Photovoltaics and Wind. John Wiley & Sons.Search in Google Scholar

El-Sebaii, A. A., F. S. Al-Hazmi, A. A. Al-Ghamdi, and S. J. Yaghmour. 2010. “Global, Direct and Diffuse Solar Radiation on Horizontal and Tilted Surfaces in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.” Applied Energy 87 (2): 568–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2009.06.032.Search in Google Scholar

Erbs, D. G., A. Klein, and A. Duffie. 1982. “Estimation of the Diffuse Radiation Fraction for Hourly, Daily and Monthly-Average Global Radiation.” Solar Energy 28 (4): 293–302, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092x(82)90302-4.Search in Google Scholar

Hassan, Q. 2022. “Evaluate the Adequacy of Self-Consumption for Sizing Photovoltaic System.” Energy Reports 8: 239–54, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.11.205.Search in Google Scholar

Hassan, Q., M. Jaszczur, M. Mohamed, K. Styszko, K. Szramowiat, and J. Gołaś. 2016. “Off-grid Photovoltaic Systems as a Solution for the Ambient Pollution Avoidance and Iraq’s Rural Areas Electrification.” Web of Conferences 10: 00093, https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20161000093.Search in Google Scholar

Hassan, Q., M. K. Abbas, A. M. Abdulateef, J. Abdulateef, and A. Mohamad. 2021. “Assessment the Potential Solar Energy with the Models for Optimum Tilt Angles of Maximum Solar Irradiance for Iraq.” Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 4: 100140, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscee.2021.100140.Search in Google Scholar

Hay, J. E., and D. C. McKAY. 1985. “Estimating Solar Irradiance on Inclined Surfaces: A Review and Assessment of Methodologies.” International Journal of Solar Energy 3 (4–5): 203–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/01425918508914395.Search in Google Scholar

Jaszczur, M., Q. Hassan, J. Teneta, K. Styszko, W. Nawrot, and R. Hanus. 2018. “Study of Dust Deposition and Temperature Impact on Solar Photovoltaic Module.” Web of Conferences: 240: 04005, https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201824004005.Search in Google Scholar

Jaszczur, M., Q. Hassan, A. M. Abdulateef, and J. Abdulateef. 2021. “Assessing the Temporal Load Resolution Effect on the Photovoltaic Energy Flows and Self-Consumption.” Renewable Energy 169: 1077–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.01.076.Search in Google Scholar

Kaushika, N. D., R. K. Tomar, and S. C. Kaushik. 2014. “Artificial Neural Network Model Based on Interrelationship of Direct, Diffuse and Global Solar Radiations.” Solar Energy 103: 327–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2014.02.015.Search in Google Scholar

Khahro, S. F., K. Tabbassum, S. Talpur, M. B. Alvi, X. Liao, and L. Dong. 2015. “Evaluation of Solar Energy Resources by Establishing Empirical Models for Diffuse Solar Radiation on Tilted Surface and Analysis for Optimum Tilt Angle for a Prospective Location in Southern Region of Sindh, Pakistan.” International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 64: 1073–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2014.09.001.Search in Google Scholar

Khorasanizadeh, H., K. Mohammadi, and A. Mostafaeipour. 2014. “Establishing a Diffuse Solar Radiation Model for Determining the Optimum Tilt Angle of Solar Surfaces in Tabass, Iran.” Energy Conversion and Management 78: 805–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2013.11.048.Search in Google Scholar

Koronakis, P. S. 1986. “On the Choice of the Angle of Tilt for South Facing Solar Collectors in the Athens Basin Area.” Solar Energy 36 (3): 217–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092x(86)90137-4.Search in Google Scholar

Lam, J. C., and D. H. Li. 1996. “Correlation between Global Solar Radiation and its Direct and Diffuse Components.” Building and Environment 31 (6): 527–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-1323(96)00026-1.Search in Google Scholar

LeBaron, B., and I. Dirmhirn. 1983. “Strengths and Limitations of the Liu and Jordan Model to Determine Diffuse from Global Irradiance.” Solar Energy 31 (2): 167–72, https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092x(83)90078-6.Search in Google Scholar

Li, D. H., S. W. Lou, and J. C. Lam. 2015. “An Analysis of Global, Direct and Diffuse Solar Radiation.” Energy Procedia 75: 388–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.399.Search in Google Scholar

Manju, S., and M. Sandeep. 2019. “Prediction and Performance Assessment of Global Solar Radiation in Indian Cities: A Comparison of Satellite and Surface Measured Data.” Journal of Cleaner Production 230: 116–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.108.Search in Google Scholar

Mario, H. M. 1994. “Caracterización de la radiación solar para aplicaciones fotovoltaicas en el caso de Madrid.” Doctoral diss., Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.10.1016/0038-092X(83)90078-6Search in Google Scholar

Marques Filho, E. P., A. P. Oliveira, W. A. Vita, F. L. Mesquita, G. Codato, J. F. Escobedo, and J. R. A. França. 2016. “Global, diffuse and direct solar radiation at the surface in the city of Rio de Janeiro: Observational characterization and empirical modeling.” Renewable Energy 91: 64–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2016.01.040.Search in Google Scholar

Padovan, A., and D. Del Col. 2010. “Measurement and Modeling of Solar Irradiance Components on Horizontal and Tilted Planes.” Solar Energy 84 (12): 2068–84, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2010.09.009.Search in Google Scholar

Pandey, C. K., and A. K. Katiyar. 2009. “A Note on Diffuse Solar Radiation on a Tilted Surface.” Energy 34 (11): 1764–9, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2009.07.006.Search in Google Scholar

Polish ministry of energy. Also available at http://mib.gov.pl/.10.1016/j.renene.2016.01.040Search in Google Scholar

Posadillo, R., and R. L. Luque. 2009. “Evaluation of the Performance of Three Diffuse Hourly Irradiation Models on Tilted Surfaces According to the Utilizability Concept.” Energy Conversion and Management 50 (9): 2324–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2009.05.014.Search in Google Scholar

Reindl, D. T., W. A. Beckman, and J. A. Duffie. 1990. “Diffuse Fraction Correlations.” Solar Energy 45 (1): 1–7, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-092x(90)90060-p.Search in Google Scholar

Rossi, T. J., J. F. Escobedo, C. M. dos Santos, L. R. Rossi, M. B. P. da Silva, and E. Dal Pai. 2018. “Global, Diffuse and Direct Solar Radiation of the Infrared Spectrum in Botucatu/SP/Brazil.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 82: 448–59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.09.030.Search in Google Scholar

Sanchez-Lorenzo, A., J. Calbó, and M. Wild. 2013. “Global and Diffuse Solar Radiation in Spain: Building a Homogeneous Dataset and Assessing Their Trends.” Global and Planetary Change 100: 343–52, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.11.010.Search in Google Scholar

Santhakumari, M., and N. Sagar. 2019. “A Review of the Environmental Factors Degrading the Performance of Silicon Wafer-Based Photovoltaic Modules: Failure Detection Methods and Essential Mitigation Techniques.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 110: 83–100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.04.024.Search in Google Scholar

Shukla, K. N., S. Rangnekar, and K. Sudhakar. 2015. “Comparative Study of Isotropic and Anisotropic Sky Models to Estimate Solar Radiation Incident on Tilted Surface: A Case Study for Bhopal, India.” Energy Reports 1: 96–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2015.03.003.Search in Google Scholar

Soares, J., A. P. Oliveira, M. Z. Božnar, P. Mlakar, J. F. Escobedo, and A. J. Machado. 2004. “Modeling Hourly Diffuse Solar-Radiation in the City of São Paulo Using a Neural-Network Technique.” Applied Energy 79 (2): 201–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2003.11.004.Search in Google Scholar

Teke, A., B. Yıldırım, and O. Celik. 2015. “Evaluation and Performance Comparison of Different Models for the Estimation of Solar Radiation.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 50: 1097–107, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.05.049.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, H., F. Sun, T. Wang, and W. Liu. 2018. “Estimation of Daily and Monthly Diffuse Radiation from Measurements of Global Solar Radiation a Case Study across China.” Renewable Energy 126: 226–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.03.029.Search in Google Scholar

Wu, W., X. Tang, J. Lv, C. Yang, and H. Liu. 2021. “Potential of Bayesian Additive Regression Trees for Predicting Daily Global and Diffuse Solar Radiation in Arid and Humid Areas.” Renewable Energy 177: 148–63, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.05.099.Search in Google Scholar

Yao, W., Z. Li, Y. Wang, F. Jiang, and L. Hu. 2014. “Evaluation of Global Solar Radiation Models for Shanghai, China.” Energy Conversion and Management 84: 597–612, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2014.04.017.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Progress in smart industrial control applied to renewable energy system

- Multi-level energy efficient cooperative scheme for ring based clustering in wireless sensor network

- Optimizing of hybrid renewable photovoltaic/wind turbine/super capacitor for improving self-sustainability

- Feasibility study of a self-consumption photovoltaic installation with and without battery storage, optimization of night lighting and introduction to the application of the DALI protocol at the University of Ibn Tofail (ENSA/ENCG), Kenitra – Morocco

- Regenerative shock absorber using cylindrical cam and slot motion conversion

- Energy efficiency measures and technical-economic study of a photovoltaic self-consumption installation at ENSA Kenitra, Morocco

- The investigation of ferro resonance voltage fluctuation considering load types and damping factors

- Review

- Methods for estimating lithium-ion battery state of charge for use in electric vehicles: a review

- Research Articles

- Experimental investigation for the estimation of the intensity of solar irradiance on oblique surfaces by means of various models

- Statistical investigation of pivotal physical and chemical factors on the performance of ceramic-based microbial fuel cells

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Progress in smart industrial control applied to renewable energy system

- Multi-level energy efficient cooperative scheme for ring based clustering in wireless sensor network

- Optimizing of hybrid renewable photovoltaic/wind turbine/super capacitor for improving self-sustainability

- Feasibility study of a self-consumption photovoltaic installation with and without battery storage, optimization of night lighting and introduction to the application of the DALI protocol at the University of Ibn Tofail (ENSA/ENCG), Kenitra – Morocco

- Regenerative shock absorber using cylindrical cam and slot motion conversion

- Energy efficiency measures and technical-economic study of a photovoltaic self-consumption installation at ENSA Kenitra, Morocco

- The investigation of ferro resonance voltage fluctuation considering load types and damping factors

- Review

- Methods for estimating lithium-ion battery state of charge for use in electric vehicles: a review

- Research Articles

- Experimental investigation for the estimation of the intensity of solar irradiance on oblique surfaces by means of various models

- Statistical investigation of pivotal physical and chemical factors on the performance of ceramic-based microbial fuel cells