Abstract

In September of 2014, the American College of Radiology joined a number of other organizations in sponsoring the 2015 National Academy of Medicine report, Improving Diagnosis In Health Care. Our presentation to the Academy emphasized that although diagnostic errors in imaging are commonly considered to result only from failures in disease detection or misinterpretation of a perceived abnormality, most errors in diagnosis result from failures in information gathering, aggregation, dissemination and ultimately integration of that information into our patients’ clinical problems. Diagnostic errors can occur at any point on the continuum of imaging care from when imaging is first considered until results and recommendations are fully understood by our referring physicians and patients. We used the concept of the Imaging Value Chain and the ACR’s Imaging 3.0 initiative to illustrate how better information gathering and integration at each step in imaging care can mitigate many of the causes of diagnostic errors. Radiologists are in a unique position to be the aggregators, brokers and disseminators of information critical to making an informed diagnosis, and if radiologists were empowered to use our expertise and informatics tools to manage the entire imaging chain, diagnostic errors would be reduced and patient outcomes improved. Heath care teams should take advantage of radiologists’ ability to fully manage information related to medical imaging, and simultaneously, radiologists must be ready to meet these new challenges as health care evolves. The radiology community stands ready work with all stakeholders to design and implement solutions that minimize diagnostic errors.

Introduction

In September of 2014, the American College of Radiology (ACR) joined the College of American Pathologists, the American Society for Clinical Pathology, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The Doctors Company Foundation, the Cautious Patient Foundation, the Kaiser Permanente National Community Benefit Fund at the East Bay Community Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Janet and Barry Lang in sponsoring the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) 2015 report, Improving Diagnosis In Health Care [1]. The NAM, formerly known as the Institute of Medicine (IOM), produced this report as a follow-up to the IOM reports To Err is Human: Building a Safer System (2000) [2] and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (2001) [3]. The major premises of the NAM were that “the occurrence of diagnostic errors has largely been unappreciated in efforts to improve quality and safety in health care” and that “most people will experience one diagnostic error in their lifetime, sometimes with devastating consequences” [1].

As part its sponsorship of the report, the ACR had the opportunity to present a number of existing initiatives from organized radiology to the NAM Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care that demonstrate our specialty’s commitment to establishing a culture of improvement and patient-centered care among radiologists and to developing tools that can be made widely available to all physicians and imaging facilities to reduce errors and improve the care of the patients we serve. A common misconception is that errors in imaging diagnosis are limited to perceptual or cognitive errors when interpreting an imaging examination. To the contrary, however, and perhaps more importantly, errors in imaging diagnosis are not limited to misinterpretation but can occur at any point in the continuum of imaging care. The American College of Radiology believes that the whole process – including having an accurate clinical history, appropriate selection of imaging exam (if any), optimal imaging acquisition, accurate interpretation, actionable reporting, and effective communication including follow-up and treatment planning – can be enhanced to minimize diagnostic errors related to imaging. A framework that is patient-centered rather than physician-centered also reduces the risk of diagnostic error by empowering patients in their medical decision making.

The Imaging Value Chain and Imaging 3.0: radiology’s framework for improving diagnosis in health care

Historically, radiologists have served primarily to ensure satisfactory imaging is obtained, images are appropriately interpreted and a report is rendered for the medical record. However, many radiologists are expanding this more traditional role and are now involved in the imaging care of their patients beginning when imaging is first considered and ending only when our patients and referring physicians fully understand the results and recommendations from their imaging studies. The “Imaging Value Chain” [4], [5], [6] (Figure 1) is a framework that describes this expanding role of radiologists, provides opportunities for radiologists to make significant improvements in the care we provide for our patients and establishes the foundation of the ACR’s Imaging 3.0 patient-focused improvement initiative [7]. Patient experience with imaging typically begins with consideration of whether imaging is necessary to establish or exclude a diagnosis, and when necessary, determining the most appropriate examination. Patients need to be appropriately educated and prepared before arriving for their imaging examinations, and imaging protocols need to be tailored to answer the clinical question informed by the patient’s history and prior imaging examinations. Image acquisition must follow appropriate procedures to avoid exams done on the wrong patient or side or incomplete coverage of anatomy, which may lead to incorrect or delayed diagnoses. Examinations are interpreted by properly qualified and certified physicians and an actionable report is created. Results, including actionable recommendations, are reported to the referring physician, and potentially the patient, in a clear and timely manner to aid and inform treatment planning. The ordering physician then appropriately uses the information from the imaging report and consultation with the interpreting physician, in combination with other clinical information, to formulate a plan for the care of the patient. Results and recommendations must also be clear to our patients with processes in place to ensure appropriate follow-up is obtained. Systematic feedback on imaging physicians’ performance allows physicians to monitor their quality and institute improvements as needed. Diagnostic errors may occur at any step of the process, and guidelines, specialty society resources and technological tools are available to reduce those errors. Figure 1 outlines the questions that should be asked by radiologists and their imaging facilities at each step of the Imaging Value Chain to ensure the care they provide is optimized to reduce diagnostic error. The ACR Imaging 3.0 initiative not only describes how radiologists can harness the resources that are currently available to radiologists but also outlines tools that can be developed and deployed nationally to improve the care we provide for our patients at each of these steps. The premise of the ACR’s Imaging 3.0 initiative is that if radiologists were empowered to use our expertise and informatics tools to manage the entire imaging chain, errors in diagnosis would be reduced and outcomes improved. Our approach in our presentation to the NAM is not unlike that of other reviews of diagnostic errors [8]. We used our Imaging 3.0 initiative as a patient-centered framework to 1) describe sources of diagnostic errors as they relate to diagnostic imaging; 2) list resources for reducing errors, 3) present available evidence about the effectiveness of these resources and 4) make recommendations for improvements to the health care system (Table 1).

Sources of error, available resources and ACR recommendations.

| Sources of error | Tools and resources | ACR Recommendations to the NAM |

|---|---|---|

| Inappropriate examination requested or appropriate examination not requested | ACR Appropriateness Criteria, Clinical Decision Support for referring physicians and registry reporting | Promote clinical decision support for imaging appropriateness and promote collection and benchmarking quality and improvement data through registry reporting |

| Appropriate screening not performed | ACR Appropriateness Criteria and national specialty society guidelines | Promote appropriate evidence-based screening to facilitate early disease detection |

| Prior imaging history not available | Image sharing technology and personal imaging records | Promote image sharing technologies and personal imaging records to ensure all available imaging data is available to radiologists |

| Inadequate clinical history and information not readily available to radiologists in the EHR | Data mining techniques and other EHR enhancements to make more clinical information readily available to radiologists | Establish a culture of collaboration and improved communication within the health care team and promote improvements in EHR systems for seamless access to patient information within the radiologist’s workflow |

| Inadequate image quality | ACR Practice Parameters and Technical Standards, ACR Accreditation and consistent credentialing for radiologic technologists | Promote state legislative requirements for robust technologist credentialing and promote facility accreditation and adherence to standardized protocols to ensure optimal image acquisition |

| Unnecessary radiation exposure | Image Wisely, Image Gently, CDS tools, and medical physicists | Promote the use of tools such as dose registries optimize protocols to ensure lowest possible radiation exposure |

| Inadequate information available at the time of imaging interpretation and key information not integrated | EHR enhancements to make more clinical information readily available to radiologists, decision support tools for radiologists | Promote EHR systems enhancements to provide information access at the time of interpretation for more accurate and clinically focused interpretation related to clinical diagnosis |

| Physician perceptual and interpretive error | Structured reporting, computer-assisted detection/artificial intelligence | Promote the use of structured reporting templates, the use of informatics tools to improve detection, interpretation and quality of recommendations |

| Interpreting physician knowledge gaps | Adequacy of training, peer learning, computer assisted reporting and decision support for radiologists | Promote informatics enhancements that create a culture of peer learning and the use of radiologist decision support tools to provide more information to radiologists during interpretation |

| Radiologist recommendations not standardized or poorly understood | Evidence-based guidelines from national specialty societies integrated into decision support tools for radiologists | Promote the development of guidelines for standardized recommendations incorporated into structured reports that ensure patients and referring physicians understand findings and recommendations |

| Results not communicated in a timely manner | EHR integrated critical results management tools for notification and managing follow-up recommendations and scheduling | Promote EHR enhancements including development of automated solutions for critical results notifications and reminders for to ensure recommendations are followed |

| Imaging outcomes not readily available or benchmarked to inform quality improvement activities | National data registries such as ACR NRDR aggregate and benchmark data to provide radiologists and their facilities information to monitor and demonstrate quality | Promote the use of clinical data registries to promote quality improvement, peer learning and outcomes reporting |

Decision to image, imaging examination selection and patient scheduling

Reducing diagnostic error in imaging begins with assuring the correct examination is ordered. Inappropriate imaging can lead to over-diagnosis or diagnosis can be delayed if an indicated examination is not obtained. Radiologists have an important role prior to imaging to ensure imaging is appropriate, the correct examination is performed and that patients are educated about their examinations. Misdiagnosis can occur if an examination is ordered and performed when imaging has very low probability of providing impactful information leading to unnecessary radiation exposure, over-diagnosis/treatment or an inappropriate diagnosis that delays or hinders appropriate treatment. Furthermore, if imaging is needed but an inappropriate examination for the clinical circumstances is requested and performed, there may be a need for additional follow-up examinations. And finally, a negative result from an inappropriate examination may lead to a delayed or missed diagnosis. Alternatively, physicians may feel pressure to do less imaging in order to save resources and may not order necessary imaging studies leading to a delayed or missed diagnosis. In cost constrained environments, screening exams for at-risk populations which can lead to early disease detection and improved care may be omitted, and limited access to prior imaging history may lead to unnecessary duplicated studies. Finally, proper patient education and preparation are often key to obtaining an optimal imaging examination, and improper patient preparation can be an additional source of diagnostic error.

A number of resources and tools are available to improve the appropriateness of medical imaging and improve patient experience. Evidence-based decision support tools for ordering physicians not only let ordering physicians know whether an examination is appropriate but they can recommend alternative examinations when the chosen examinations is not the most appropriate. Over the past two decades the ACR developed the ACR Appropriateness Criteria® [9] which are robust evidence-based imaging referral guidelines that are included in the National Guidelines Clearinghouse [10]. The Institute of Medicine’s 2012 report Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path To Continuously Learning Health Care in America [11] recommends, “Decision support tools and knowledge management systems can be included routinely in health care delivery to ensure that decisions are informed by the best evidence”. ACRSelect® [12] is a nationally available clinical decision support (CDS) system that delivers the content of the ACR Appropriateness Criteria® to the clinician at the point of care. The tool integrates with electronic health records (EHR) and order entry systems to provide guidance on image ordering in conjunction with information on patient history and status with little interruption of the clinical workflow of the referring physician. In contrast to the binary prior authorization process offered by radiology benefit management companies, ACRSelect® provides the referring physician other examination options so that the most appropriate imaging examination is obtained. The tool also can initiate a radiologist consultation to supplement the content delivered electronically. The ability to initiate a consultation with a radiologist when the appropriateness score is low allows radiologists to assist in ensuring the correct test is ordered in advance of scheduling. Additionally, ACRSelect® provides information regarding radiation exposure and can link referring physicians with information from the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Choosing Wisely® [13] campaign.

The Radiology Support, Communication and Alignment Network, R-SCAN™ [14], is a collaborative action plan funded by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) through a Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative grant that brings radiologists and referring clinicians together to improve imaging appropriateness based upon a growing list of imaging Choosing Wisely recommendations [15]. R-SCAN delivers immediate access to Web-based tools and CDS technology that help physicians optimize imaging care and prepare for more broad implementation of CDS ahead of the Protecting Access to Medicare Act of 2014 [16] mandate. Additionally, registries and feedback mechanisms under development will soon provide benchmarks to provide feedback to referring physicians. The feedback will be designed as an educational tool for referring physicians and to channel information from referring physician to the guideline development process to facilitate improvements in guidelines. The ACR Appropriateness Criteria have been recognized as a tool professional societies can use to prepare physicians for health reform, and the ACR has actively supported legislative efforts that bring evidence-based decision support tools to the point of care [16], [17].

Studies on clinical decision support for ordering physicians have shown this solution reduces inappropriate utilization [18], [19], which promotes patient safety and should limit over-diagnosis and potential unnecessary workup of benign incidental findings. In contrast to the binary systems of prior-authorization programs used by most radiology benefit management companies, clinical decision support solutions improve the efficiency of referring physicians and can suggest a more appropriate alternative examination if the one initially considered is not the most appropriate [20] likely improving disease detection and early diagnosis. As clinical decision support gains wider acceptance, data on improved patient outcomes as a consequence of imaging decisions will become available.

Radiologists play a key role in disease detection. For many disease processes, imaging is often the best way to establish an early diagnosis in order to begin appropriate management. Multi-center trials have shown that appropriate screening for diseases such as breast cancer, colon cancer and lung cancer can reduce mortality in appropriate populations [21], [22], [23], and further research, including development of non-imaging biomarkers for certain disease processes, may define the populations at greatest risk for other diseases to ensure appropriate use of imaging in early disease detection.

Radiologists from the ACR and the Radiology Society of North America (RSNA) [24] have developed a patient-facing portal, Radiologyinfo.org [25], to provide information about imaging procedures and patient preparation necessary for the procedures. Proper patient preparation is often key to obtaining an optimal imaging examination and reducing diagnostic error. Access to personal imaging records can reduce diagnostic error by providing an imaging history for patients. This helps avoid duplication, limits radiation, and leads to the best follow-up examinations. The RSNA Image Share [26] program is designed to develop personal imaging records and facilitate access of patient imaging information between facilities. ACR TRIAD [27] is built to share images and data between facilities, researchers and clinical data registries. Image Share and TRIAD are examples of how the radiology community is leading efforts to manage the wealth of information we collect on our patients to improve care.

Diagnostic errors may also occur if potentially diagnostic imaging is not requested. Development of data mining and artificial intelligence tools that prompt physicians to consider appropriate imaging may also lead to improved disease detection.

ACR recommendations to the NAM included promoting clinical decision support for imaging appropriateness and collecting and benchmarking quality and improvement data about imaging appropriateness through registry reporting as well as appropriate evidence-based screening based on established guidelines to facilitate early disease detection. Imaging sharing technologies should be embraced so that decision to image can be based on knowledge from prior studies.

Protocol selection and image acquisition

Radiologists prescribe imaging protocols that are based on information provided to us by both our referring physicians and our patients. Inadequate information from these sources as well as limited access to patients’ electronic health records (EHR) may lead to inappropriate or inadequate examinations and delays or errors in diagnosis. Patient safety may also be affected if critical clinical information such as contrast allergy is not available, and patients might be subjected to unnecessary radiation exposure if there is a need to repeat an examination. In addition, patients might need to have their examinations rescheduled if an alternate examination is determined to be more suitable once a full clinical history is obtained, potentially resulting in delayed diagnosis. Additionally, poor image quality often leads to errors in diagnosis. Improper technique, inadequate equipment or image acquisition performed by inadequately trained personnel (for example, non-technologists performing radiographic imaging) may lead to non-diagnostic images which can result in diagnostic errors or repeat imaging procedures. Unfortunately state licensure requirements to ensure adequate training for personnel performing diagnostic imaging examinations are inconsistent and may not be stringent. Moving advanced imaging to the bedside, such as point-of-care ultrasound performed by non-radiologists, may introduce another source for diagnostic error. These examinations may yield poor clinical information resulting in over-diagnosis, under-diagnosis, or unnecessary referrals for additional imaging and more invasive procedures [28]. Finally, government and private insurance payment policy often prevents radiologists from correcting the examination requested by our referring physicians, which can also lead to inadequate examinations [29].

EHRs can be tailored to provide radiologists information on patient clinical and imaging history, allergies and contraindications to assist in protocol selection but need to be integrated with radiology information systems (RIS) to efficiently provide necessary information to radiologists. ACR Practice Parameters and Technical Standards [30] assist in examination design and protocol creation and promote standardization to ensure uniformity of examinations. The pediatric imaging radiation protection campaign, Image Gently [31], provides optimized protocols for pediatric examinations. The ACR Accreditation process [32], with modality specific accreditation programs and image review, establishes standards for image quality and also educates facilities on how to improve. There is evidence that there is improved image quality on examinations that follow accreditation specifications and participate in accreditation programs [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35]. Site accreditation can provide assurance to patients and referring physicians that their facilities are meeting national requirements for adequacy of personnel, image protocols and image quality. Medical physicists should also be considered integral members of care team. They are able to monitor technical parameters that ensure diagnostic quality images are obtained with the lowest possible radiation exposure while ensuring image quality is sufficient to support accurate interpretation and diagnosis. The American Association for Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) [36] recommends protocols to standardize practice across scanners from different manufacturers to optimize image quality while adhering to ALARA (As Low As Reasonably Achievable) [37] radiation exposure principles. While not directly related to improving diagnosis, unnecessary exposure is a patient related error that can arise from the image acquisition process. The Image Gently [31], [38] and Image Wisely [39], [40] campaigns offer ways to mitigate patient risk by optimizing exposure to ionizing radiation. The ACR Dose Index Registry benchmarks imaging facilities against national and regional norms in order to provide guidance for sites in adjusting their computed tomography protocols [41].

Our recommendations to the NAM highlight that although radiologists are the experts in choosing the optimal protocol for imaging examinations, they require appropriate clinical information to inform their decisions. Improvements in EHR system interoperability can create seamless access to patient information within the radiologist’s workflow so that the correct protocol is used and payment policies must allow proper protocolling and not restrict radiologists from using their expertise. Promoting consistent requirements for technologist credentialing in all states and promoting facility accreditation and use of practice parameters can help eliminate poor image quality as a source of diagnostic errors in radiology.

Interpretation and reporting

Physicians’ failure to detect a significant imaging finding may also lead to errors in diagnosis. This is more frequent when a structured analysis of the imaging procedure is not followed, and can be minimized by use of structured reporting formats. Additionally, a physician may perceive an abnormality but incorrectly conclude it is a benign finding, or conversely, a benign finding may be misinterpreted as clinically significant leading to over-diagnosis and unnecessary additional care and patient anxiety. The volume of available medical information and evidence-based guidelines is increasing rapidly, and physicians without access to up-to-date clinical guidance or patient specific information from the patient’s medical record may misinterpret what they observe. A physician may suggest an incorrect diagnosis or be unaware of appropriate evidence-based recommendations for follow-up, lack of access to prior examinations may also result in a diagnostic error. For example, having an older study showing that a lesion is stable over time would likely indicate benign disease. Even with accurate detection and interpretation, incomplete or ambiguous reporting may result in inadequate or inconsistent recommendations for our referring physicians and patients and impede appropriate care or lead to errors in diagnosis.

With advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, computer-aided detection (CAD) may play an increasingly important role in improving disease detection and characterization. Machine learning will be valuable to radiologists in assisting in discovery, quantification and characterization of lesions and in providing opportunities for radiologists to take on a larger role in information interpretation, integration and communication. Lexicons and algorithms, such as the BI-RADS® system [41], [42], can provide a common format structured for reports, evidence-based recommendations based on the imaging findings, a communication system for referring physicians and patients, a critical result management system, and a quality monitoring framework with registry reporting. Peer review programs with emphasis on peer learning help radiologists identify incorrect interpretations or recommendations and suggest areas for educational focus. Future advancements in peer review programs might include self-assessment cases embedded in the daily workflow to help guide the educational activities of the interpreting physicians. Standardized reporting and standardized templates ensure complete evaluation of the imaging examination and can assist many aspects of interpretation and reporting. Recommendations on the appropriate management of actionable findings use evidence-based guidelines to standardize specific diagnoses that require immediate attention thus ensuring prompt communication of the findings to appropriate members of the patient care team. Additionally, evidence-based guidelines on appropriate management of incidental findings promote appropriate and standardized management of incidentally detected abnormalities, many of which will not be clinically significant. EHR enhancements can ensure appropriate members of the care team are notified and registries can create reminder systems to ensure appropriate follow-up is obtained. Development of computer-assisted reporting tools, which are best understood as decision support tools for radiologists, is well underway within the ACR and at a number of academic practices. ACR Assist™ [43] is a clinical decision support framework designed to provide structured guidance to radiologists in a manner that incorporates evidence-based clinical guidance into the radiology workflow. The core clinical components that comprise ACR Assist™ content include structured classification and reporting taxonomies such as the ACR Reporting and Data Systems (RADS) (LI-RADS [44], PI-RADS [45], and Lung-RADS [46]) and care pathways and algorithms such as those found in the ACR Incidental Findings White Papers [47] and classification and communication recommendations for actionable findings [48]. The ACR “RADS” define standardized categories to be included in imaging reports for a variety of clinical conditions and examinations. They offer guidance and structured reporting templates for management recommendations that are generally supported by lexicons and example images to define and describe standard terminology. Appendix 1 provides summaries of current and developing ACR resources for integration into ACR Assist™. The goal of ACR Assist™ is to provide this content in a structured, vendor-neutral manner that allows our radiology reporting platforms to provide this guidance to radiologists during interpretation and reporting. Considerable evidence indicates tools that improve physicians’ knowledge gaps, inform structured report templates and bring clinical information and guidelines for recommendations to the reporting platform can decrease diagnostic error. Access to prior images reduces the rates of false positives and unnecessary follow-up imaging [49], and peer-review and peer-learning improve interpretation quality [50]. Of the RADS tools, diagnostic accuracy has been studied most using BI-RADS® which has consistently been shown to improve accuracy and the quality of interpretations in breast imaging [49], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56].

To reduce the risk of diagnostic error in imaging interpretation and reporting, the ACR recommends that image interpretation should be performed by appropriately trained physicians who maintain their skills with education and quality improvement activities. The risk of misdiagnosis and overuse of resources associated with moving advanced imaging studies to the bedside that are subsequently interpreted by physicians with limited training should also be considered as care pathways change due to more universal access of imaging equipment. Additionally, we support a number of enhancements to EHR systems that will deliver in depth patient information to the radiologist at the time of interpretation to improve diagnostic accuracy and diminish errors. Furthermore, widespread adoption of point-of-care radiologist decision support systems and computer-assisted reporting tools (such as ACR Assist™) will significantly reduce variation in radiologists’ recommendations and likely reduce diagnostic errors. Payment policy incentives through the Medicare Quality Payment Program [57] could promote continuous physician learning through enhanced educational opportunities, inform deficiencies and provide pathways for targeted education.

Communication of results and recommendations

Incomplete, unclear, or non-standardized communication in radiology reports may lead to misinterpretation of the results by referring physicians and patients leading to either inappropriate treatment or lack of treatment. Delayed reports, particularly for urgent conditions, may result in delayed diagnosis and treatment, and lack of communication of the imaging findings to the patient may hinder appropriate implementation of therapy or follow-up. Direct patient communication from radiologists through patient portals and radiology consultation services allows patients to receive information about their medical imaging studies and empowers them to be more involved in their imaging care which will lead to better compliance with recommendations for follow-up [58].

The ACR Practice Parameter For Communication Of Diagnostic Imaging Findings [59] defines optimal communication of diagnostic imaging findings to ensure transmission of critical diagnostic information to the ordering physician. However, communication tools embedded in the workflow of both radiologists and referring physicians will better ensure accurate communication of actionable findings. In addition to the “RADS” reporting formats previously discussed, the radiology community is developing standardized terminology to describe clinical indications, imaging procedures and findings. Standardizing the terminology in radiology reports should reduce ambiguity for treating physicians and will allow interoperability of informatics tools from decision support for the ordering physician to registry reporting of actionable findings. There are a number of available tools and resources to assist radiologists in standardizing communication. Structured report templates have been developed by the RSNA [60] and individual radiology departments and practices. As discussed above, computer-assisted radiology reporting tools can integrate the contents of RADS and recommendations for managing incidental and actionable findings into the physician workflow through our reporting platforms to improve clarity and consistency of radiologists’ communication. Standard lexicons such as RADLEX Playbook [61] and ACRcommon™ [62] help synchronize patient data contained in disparate systems such as EHRs, clinical decision support systems, radiology reporting platforms and clinical data registries. Informatics initiatives will allow structured reporting templates to integrate RADS and other guidelines into radiology reporting tools to help standardize communication.

Proper interpretation without effective communication provides little value to patients and referring physicians. Clarity, consistency, completeness, and timeliness of communication are essential to reporting findings and recommendations with minimal error and variation. Workflow integration using informatics tools to bring evidence-based decision making to the point of care and interpretation is a critical component of communicating radiological findings and is key to minimizing diagnostic errors. Patient access to their imaging reports via web based portals can ensure communication but must be balanced with the referring providers’ need to put imaging findings in proper context with other clinical information.

Developing an infrastructure to reduce error

Reducing errors in diagnosis is contingent on having systems that collate data and track patient outcomes. Clinical data registries allow physicians to monitor their quality improvement activities and take steps to reduce diagnostic errors. Measuring physician quality is a stated goal of the Medicare Quality Payment Program (QPP) [57] that is a pay-for performance program that requires physicians to submit data on quality. Bonuses or payment reductions are tabulated based on performance against various quality and improvement metrics [57]. For essentially all of the quality and improvement measures in the QPP, CMS recommends reporting through Qualified Clinical Data Registries. The ACR National Radiology Data Registry (NRDR) program is a collection of CMS Qualified Clinical Data Registries designed to assist radiologist performance improvement and data reporting to the QPP. Registries in the NRDR program are being updated so they are able to collect data in real time through the EHR, imaging equipment, the reporting platforms or the PACS and are available to enrolled radiology facilities and physicians to monitor key metrics, benchmark performance relative to other facilities and practices, and improve overall performance. Dashboards as part of a quality management framework can identify the aspects of radiological care that are most meaningful to monitor for improved diagnostic performance.

Establishing a culture of optimal radiological care

There are cultural issues in our health care system that contribute to error in diagnosis. In the past, radiologists have been generally removed from the referring physicians’ decisions to order diagnostic imaging and because almost all outcome metrics are contingent on the treatment pathways and other aspects of care that occur after a diagnosis is made, radiologists have not been part of the development of outcomes metrics. Better integration of radiologists into the health care team provides opportunities to ensure interpretations are performed in the context of the patients’ clinical conditions, radiologists’ recommendations are understood by referring physicians and patients and that appropriate actions are taken. We believe that the informatics tools described above can be leveraged to accelerate this shift in the culture of medical care surrounding diagnostic imaging.

Campaigns such as the RSNA Radiology Cares: The Art of Patient Centered Radiological Care [61] provide the imaging community with concrete examples of how radiologists can lead a culture shift toward patient-centered imaging care. The ACR Imaging 3.0 initiative is a strategy to enhance radiologists’ roles in optimizing the value of imaging in medical care including minimizing diagnostic errors. Imaging 3.0 [7] has three key components that 1) promote a culture shift and awareness not only with our specialty but also within the entire medical community to leverage the value that radiologists provide beyond interpretations throughout the entire imaging care episode; 2) develop and promote informatics and other tools that will maximize the opportunities for appropriate use of imaging, accurate interpretations of imaging studies with appropriate recommendations and fail safe communications mechanisms so that diagnosis and appropriate therapy is not delayed; and 3) foster collaborations beyond radiology to align incentives not only within the house of medicine but also with payers and federal policy makers to provide optimal care for patients because without a shared vision to do what’s best for our patients, meaningful change will be slow to occur.

Conclusions

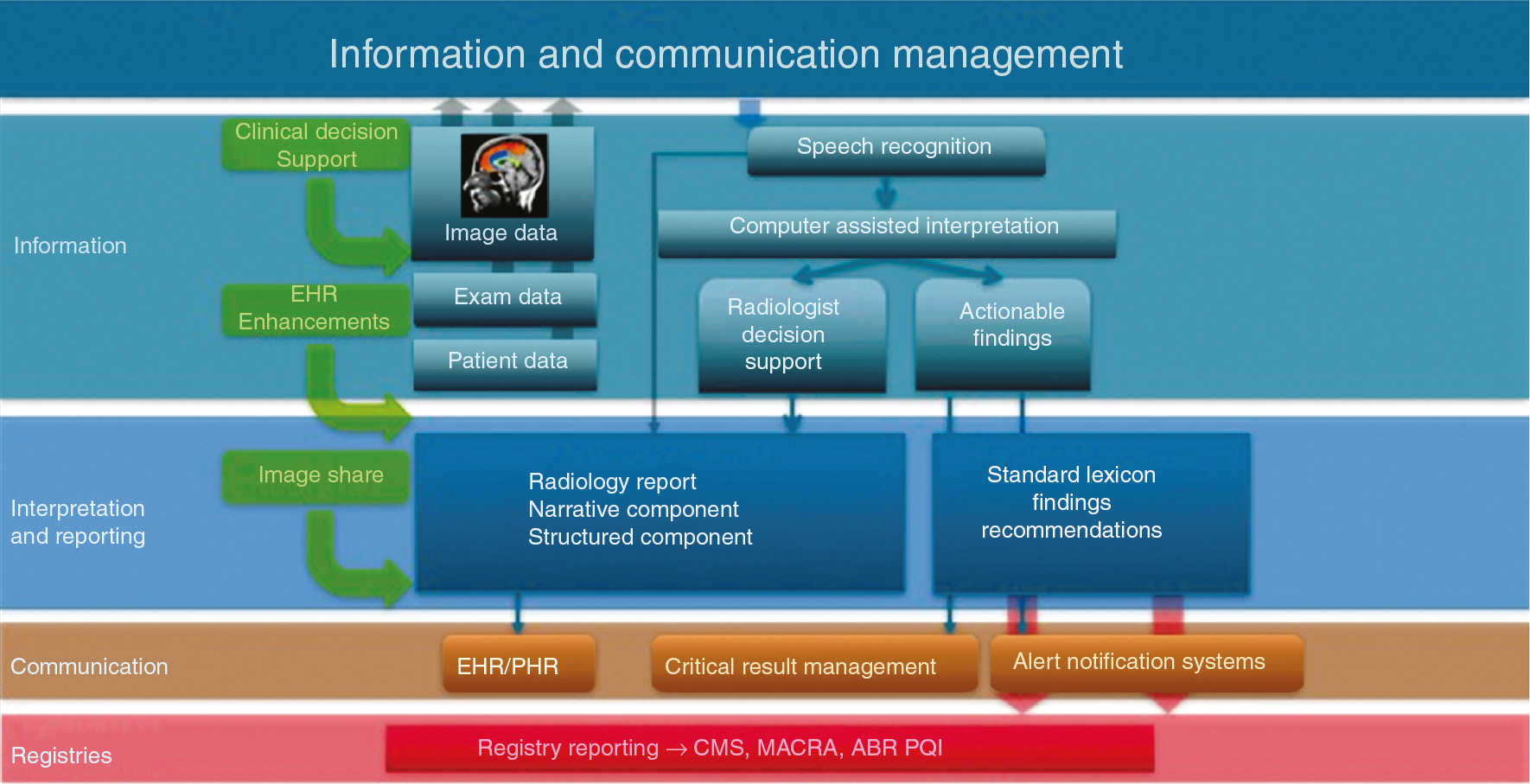

Diagnostic errors in imaging are commonly considered to result only from failures in perception or cognitive error resulting in misinterpretation of a perceived abnormality on an imaging examination. In fact, in the report, the NAM emphasizes that optimization of information gathering, integration and interpretation are critical to improving diagnosis in health care. Their recognition that the diagnostic process is a “dynamic team-based activity” and their recommendation to support inter-professional teamwork early on in the process matches our approach in expanding radiologists’ traditional role in the diagnostic process [1]. The NAM recommendations highlight the understanding that diagnostic errors in imaging can occur at any point on the entire continuum of imaging care from when imaging is first considered until the results and recommendations are fully understood by the referring physicians and patients, and opportunities for improvement exist at each step in the Imaging Value Chain. Successful aggregation, dissemination and communication of all information related to imaging is critical so that the health care team can establish the correct diagnosis and patients can have all of the information they need to make informed decisions about their care. The ACR Imaging 3.0 initiative underscores the premise that radiologists are in a unique position to be the gatherers, aggregators, brokers and disseminators of the that information, and that if radiologists are empowered to use our expertise and informatics tools to manage the entire imaging chain, errors in diagnosis would be reduced and patient outcomes improved. Heath care teams should expand the role of radiologists beyond disease detection and image interpretation to take full advantage of radiologists’ ability to aggregate, collate and disseminate information and simultaneously radiologists must step up to meet this new challenge. Effective communication (Figure 2) between members of the health care team and our patients is necessary to ensure appropriate imaging is requested and consistent, accurate and impactful standardized reports result in improved patient care. This is critical to reducing diagnostic error. The radiology community is firmly committed to quality improvement and stands ready to work with all stakeholders to design, implement and disseminate solutions to minimize errors in diagnosis.

Information and communication management.

Adapted from Keith Dryer, DO and used with permission.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Disclosure statement: The American College of Radiology is a nonprofit national medical specialty society. However, some of the examples of the resources available to physicians and health care systems included in this review such as Accreditation and ACRSelect are only available commercially and the ACR derives financial benefit from the sale of those products. There may be other tools that can accomplish similar functions and this review is not meant to promote ACR resources over those of other vendors.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Appendix 1: Radiologist decision support tools

Reporting and Data Systems (RADS)

Currently in place

BI-RADS® includes definitions of assessment categories that are associated with different probabilities of malignancy for breast cancer, management recommendations, lexicon of standard terms, and atlas of example images. BI-RADS® includes three breast imaging modalities - mammography, ultrasound and MRI. The recently released 5th Edition is available as print and e-books, and is licensed to vendors for implementation in reporting systems.

C-RADS includes standardized reporting, risk assessment and management tool for colorectal and extra-colonic CT findings.

CAD-RADS™ includes standardized reporting through a decision- making tool for patient management and patient outcomes. CAD-RADS is a multi-society, multi-disciplinary system that improves the communication of coronary CT angiography (CTA) findings to referring physicians.

LI-RADS® includes assessment categories, management recommendations, lexicon of terms, and atlas of images for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). LI-RADS covers CT and MRI; the section on ultrasound is in early stages of planning. This is available freely under a creative commons license for non-derivative non-commercial use.

Lung-RADS™ includes assessment categories and management recommendations for CT screening for lung cancer. The Atlas and lexicon are in early stages of development. This is freely available with creative commons license for non-derivative commercial use to encourage more systems to implement it.

PI-RADS v2 includes assessment categories, management recommendations, lexicon,

and atlas for MRI for prostate cancer.

TI-RADS includes a lexicon, assessment categories, and guidance recommendations for thyroid nodules in ultrasound imaging.

In development

NI-RADS is in early stages of development and will provide surveillance and management recommendations for patients with head and neck cancer.

O-RADS is in early stages of development and will provide a lexicon, assessment categories, and risk stratification for ovarian and adnexal masses.

TBI-RADS is in early stages of development and will assess the severity of brain trauma and provide management recommendations.

Planned/considered

Spine-RADS for spine imaging

Possibly Gen-RADS to cover all imaging without any specialized guidance, and not covered by actionable or incidental findings

Incidental findings papers

Published

Managing Incidental Findings on Abdominal CT [46]

In process:

Management of Incidental Adrenal Masses: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee

Management of Incidental Liver Masses: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee

Management of the Incidental Pancreatic Cyst: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee

Management of the Incidental Renal Mass on CT: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee

Management of Incidental Findings on Thoracic CT: White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee

References

1. NAM Report. Improving diagnosis in health care (2015). Available at: https://www.nap.edu/read/21794/chapter/1. Accessed 7 Mar 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

2. IOM Report. To err is humnan: building a safer system (2000). Available at: https://www.nap.edu/read/9728/chapter/1. Accessed 7 Mar 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

3. IOM Report. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century (2001). Available at: https://www.nap.edu/read/10027/chapter/1. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Enzmann DR. Radiology’s value chain. Radiology 2012;263:243–52.10.1148/radiol.12110227Suche in Google Scholar

5. Boland GW. How we do Imaging 3.0: Value-Added Matrix. Radiology Leadership Institute, 2014. Available at: https://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/PDF/Economics/Imaging3/CaseStudies/ValueAdded-Matrix.pdf?la=en. Accessed 28 May 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Boland GW, Duszak R, McGinty G, Allen B. Delivery of appropriateness, quality, safety, efficiency and patient satisfaction. J Am Coll Radiol 2014;1:7–11.10.1016/j.jacr.2013.07.016Suche in Google Scholar

7. Imaging 3.0. 2014. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Advocacy/Economics-Health-Policy/Imaging-3. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Schiff GD, Kim S, Abrams R, Cosby K, Lambert B, Elstein AS, et al. Diagnosing diagnosis errors: lessons from a multi-institutional collaborative project. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, Lewin DI, editors. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation (Volume 2: Concepts and Methodology). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

9. ACR Appropriateness Criteria®. 2014. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Appropriateness-Criteria. Accessed 7 Mar 2014, 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

10. National Guideline Clearinghouse. 2014. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America; 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

12. ACRSelect. National Decision Support Company, 2014. Available at: http://www.acrselect.org/. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Choosing Wisely. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

14. RSCAN. Available at: https://rscan.org. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Transforming Clinical Practice Iitiative. Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Transforming-Clinical-Practices/. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Protacting Access To Meadicare Act of 2014 H.R. 4302. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/4302. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) H.R. 2. Available at: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/hr2. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Vartanians VM, Sistrom CL, Weilburg JB, Rosenthal DI, Thrall JH. Increasing the appropriateness of outpatient imaging: effects of a barrier to ordering low-yield examinations. Radiology 2010;255:842–9.10.1148/radiol.10091228Suche in Google Scholar

19. Sistrom CL, Dang PA, Weilburg JB, Dreyer KJ, Rosenthal DI, Thrall JH. Effect of computerized order entry with integrated decision support on the growth of outpatient procedure volumes: seven-year time series analysis. Radiology 2009;251:147–55.10.1148/radiol.2511081174Suche in Google Scholar

20. Lee DW, Rawson JV, Wade SW. Radiology benefit managers: cost saving or cost shifting?. J Am Coll Radiol 2011;8:393–401.10.1016/j.jacr.2010.11.016Suche in Google Scholar

21. Tabár L, Vitak B, Chen HH, Yen MF, Duffy SW, Smith RA. Beyond randomized controlled trials. Cancer 2001;91:1724–31.10.1002/1097-0142(20010501)91:9<1724::AID-CNCR1190>3.0.CO;2-VSuche in Google Scholar

22. Johnson CD, Chen MH, Toledano AY, Heiken JP, Dachman A, Kuo MD, et al. Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1207–17.10.1056/NEJMoa0800996Suche in Google Scholar

23. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;2011:395–409.10.1056/NEJMoa1102873Suche in Google Scholar

24. Radiology Society of North America. 2014. www.rsna.org. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

25. RadiologyInfo.org. 2014. Available at: http://www.radiologyinfo.org/. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

26. RSNA Image Share. 2014. Available at: https://www.rsna.org/Image_Share.aspx. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

27. TRIAD ACR Image and Information Exchange. 2014. Available at: https://cr-triad4.acr.org/TriadWeb4.0/. Accessed 21 Oct 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Allen B, Van Carrol L, Hughes DR, Hemingway J, Duszak R, Rosenkrantz AB. Downstream imaging utilization after emergency department ultrasound interpreted by Radiologists versus Nonradiologists: a medicare claims-based study. J Am Coll Radiol 2017;14:475–81.10.1016/j.jacr.2016.12.025Suche in Google Scholar

29. 42 CFR §410.32 Diagnostic x-ray tests, diagnostic laboratory tests, and other diagnostic tests: Conditions. Available at: http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=&SID=254509137be888d7af0a26624387db67&mc=true&n=sp42.2.410.b&r=SUBPART&ty=HTML#se42.2.410_132. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Practice Parameters and Technical Standards. 2014. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Standards-Guidelines. Accessed 20 Oct 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Image Gently. 2017. Available at: http://imagegently.org/. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

32. ACR Accreditation. 2017. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Accreditation. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Hobson MA, Soisson ET, Davis SD, Parker W. Using the ACR CT accreditation phantom for routine image quality assurance on both CT and CBCT imaging systems in a radiotherapy environment. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2014;15:4835.10.1120/jacmp.v15i4.4835Suche in Google Scholar

34. Destouet JM, Bassett LW, Yaffe MJ, Butler PF, Wilcox PA. The ACR’s Mammography Accreditation Program: ten years of experience since MQSA. J Am Coll Radiol 2005;2:585–94.10.1016/j.jacr.2004.12.005Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Weinreb J, Wilcox PA, Hayden J, Lewis R, Froelich J. ACR MRI accreditation: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. J Am Coll Radiol 2005;2:494–503.10.1016/j.jacr.2004.11.004Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. American Association for Physicists in Medicine (AAPM). 2014. Available at: http://www.aapm.org/. Accessed 21 Oct 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

37. ALARA. NRC Glossary. 10 CFR §20.1003 Definitions. Available at: https://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/cfr/part020/part020-1003.html. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Goske MJ, Applegate KE, Boylan J, Butler PF, Callahan MJ, Coley BD, et al. The Image Gently campaign: working together to change practice. Am J Roentgenol 2008;190:273–4.10.2214/AJR.07.3526Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Image Wisely. 2014. Available at: http://imagewisely.org/. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Brink JA, Amis ES Jr. Image Wisely: a campaign to increase awareness about adult radiation protection. Radiology 2010;257:601–2.10.1148/radiol.10101335Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

41. ACR Dose Index Registry. Available at: https://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/National-Radiology-Data-Registry/Dose-Index-Registry. Accessed 28 May 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

42. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas. 2013. Available at: http://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Resources/BIRADS. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

43. ACR Assist. Available at: https://www.acr.org/Advocacy/Informatics/Systems-and-Tools/ACR-Assist. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Li-RADS. Available at: https://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Resources/LungRADS. Accessed 7 Mar 2017Suche in Google Scholar

45. PI-RADS. Available at: https://www.acr.org/∼/media/ACR/Documents/PDF/QualitySafety/Resources/PIRADS/PIRADS%20V2.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2017Suche in Google Scholar

46. Lung-RADS. Available at: https://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Resources/LungRADS. Accessed 7 Mar 2017Suche in Google Scholar

47. Berland LL. Overview of white papers of the ACR incidental findings committee ii on adnexal, vascular, splenic, nodal, gallbladder, and biliary findings. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:672–4.10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.012Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Larson PA, Berland LL, Griffith B, Kahn CE, Liebscher LA. Actionable findings and the role of IT support: report of the ACR Actionable Reporting Work Group. J Am Coll Radiol 2014;11:552–8.10.1016/j.jacr.2013.12.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

49. Abramovici G, Mainiero MB. Screening breast MR imaging: comparison of interpretation of baseline and annual follow-up studies. Radiology 2011;259:85–91.10.1148/radiol.10101009Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

50. Iyer RS, Swanson JO, Otto RK, Weinberger E. Peer review comments augment diagnostic error characterization and departmental quality assurance: 1-year experience from a children’s hospital. Am J Roentgenol 2013;200:132–7.10.2214/AJR.12.9580Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Bent CK, Bassett LW, D’Orsi CJ, Sayre JW. The positive predictive value of BI-RADS microcalcification descriptors and final assessment categories. Am J Roentgenol 2010;194:1378–83.10.2214/AJR.09.3423Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Heinig J, Witteler R, Schmitz R, Kiesel L, Steinhard J. Accuracy of classification of breast ultrasound findings based on criteria used for BI-RADS. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008;32:573–8.10.1002/uog.5191Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Hille H, Vetter M, Hackeloer BJ. The accuracy of BI-RADS classification of breast ultrasound as a first-line imaging method. Ultraschall in der Medizin 2012;33:160–3.10.1055/s-0031-1281667Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Mahoney MC, Gatsonis C, Hanna L, DeMartini WB, Lehman C. Positive predictive value of BI-RADS MR imaging. Radiology 2012;264:51–8.10.1148/radiol.12110619Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

55. Sohns C, Scherrer M, Staab W, Obenauer S. Value of the BI-RADS classification in MR-Mammography for diagnosis of benign and malignant breast tumors. European radiology 2011;21:2475–83.10.1007/s00330-011-2210-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

56. Tozaki M, Igarashi T, Fukuda K. Positive and negative predictive values of BI-RADS-MRI descriptors for focal breast masses. Magn Reson Med Sci 2006;5:7–15.10.2463/mrms.5.7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Medicare Quality Payment Program. Available at: https://qpp.cms.gov. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

58. Mangano MD, Bennett SE, Gunn AJ, Sahani DV, Choy G. Creating a patient-centered radiology practice through the establishment of a diagnostic radiology consultation clinic. Am J Roentgenol 2015;205:95–9.10.2214/AJR.14.14165Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

59. ACR Practice Parameter For Communication Of Diagnostic Imaging Findings. Available at: https://www.acr.org/∼/media/C5D1443C9EA4424AA12477D1AD1D927D.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

60. Radiology Reporting Initiative. 2014. Available at: https://www.rsna.org/Reporting_Initiative.aspx. Accessed 21 Oct 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

61. RADLEX Playbook. Available at: https://www.rsna.org/RadLex_Playbook.aspx. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

62. ACRcommon. Available at: http://www.acrinformatics.org/ACR-Common. Accessed 7 Mar 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

63. Radiology Cares: The Art of Patient-Centered Practice. 2014. Available at: http://rsna.org/radiology_cares/. Accessed 21 Oct 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

64. Heller MT, Harisinghani M, Neitlich JD, Yeghiayan P, Berland LL. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, part 3: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on splenic and nodal findings. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:833–9.10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.020Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Khosa F, Krinsky G, Macari M, Yucel EK, Berland LL. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, Part 2: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on vascular findings. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:789–4.10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

66. Patel MD, Ascher SM, Paspulati RM, Shanbhogue AK, Siegelman ES, Stein MW, et al. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, part 1: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on adnexal findings. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:675–81.10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

67. Sebastian S, Araujo C, Neitlich JD, Berland LL. Managing incidental findings on abdominal and pelvic CT and MRI, Part 4: white paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee II on gallbladder and biliary findings. J Am Coll Radiol 2013;10:953–6.10.1016/j.jacr.2013.05.022Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

68. Hoang JK, Langer JE, Middleton WD, Wu CC, Hammers LW, Cronan JJ, et al. Managing incidental thyroid nodules detected on imaging: white paper of the ACR Incidental Thyroid Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:143–50.10.1016/j.jacr.2014.09.038Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Improving diagnosis in radiology – progress and proposals

- Reviews

- Improving diagnosis in health care: perspectives from the American College of Radiology

- The role of radiology in diagnostic error: a medical malpractice claims review

- Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad

- Perceptual errors in pediatric radiology

- 256 Shades of gray: uncertainty and diagnostic error in radiology

- Using Bayes’ rule in diagnostic testing: a graphical explanation

- X-ray art images: objects from nature

- Mini Review

- Assigning responsibility to close the loop on radiology test results

- Opinion Papers

- Information overload: when less is more in medical imaging

- Radiology education: a radiology curriculum for all medical students?

- Letter to the Editor

- Demonstration Collaborative project to reduce emergency department radiologic diagnostic errors

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Improving diagnosis in radiology – progress and proposals

- Reviews

- Improving diagnosis in health care: perspectives from the American College of Radiology

- The role of radiology in diagnostic error: a medical malpractice claims review

- Medical errors, malpractice, and defensive medicine: an ill-fated triad

- Perceptual errors in pediatric radiology

- 256 Shades of gray: uncertainty and diagnostic error in radiology

- Using Bayes’ rule in diagnostic testing: a graphical explanation

- X-ray art images: objects from nature

- Mini Review

- Assigning responsibility to close the loop on radiology test results

- Opinion Papers

- Information overload: when less is more in medical imaging

- Radiology education: a radiology curriculum for all medical students?

- Letter to the Editor

- Demonstration Collaborative project to reduce emergency department radiologic diagnostic errors

![Figure 1: Framework for patient experience with imaging and potential for diagnostic errors.Source: Based on the Imaging Value Chain [4], [5], [6].](/document/doi/10.1515/dx-2017-0020/asset/graphic/j_dx-2017-0020_fig_001.jpg)