ChatGPT as a direct formative assessment tool in stoichiometry: correlation with achievement and insights into pre-service science teachers’ perceptions

Abstract

Generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) has become increasingly important in education. However, its application for direct formative assessment represents an emergent area of inquiry. This mixed-methods study investigated the use of ChatGPT for formative assessment in a stoichiometry unit with 38 pre-service science teachers. We examined the relationships between ChatGPT assessment scores (scores produced when students prompted the AI to assess their own answers), final achievement scores, and instructor assessment scores. Spearman’s correlation revealed that ChatGPT assessment scores strongly correlated with final achievement scores (rs = 0.670) and instructor assessment scores (rs = 0.882). To explore the mechanisms underlying the achievement correlation, a qualitative analysis of interviews (N = 13) explored pre-service science teachers’ perceptions. Findings indicated that ChatGPT was perceived as beneficial for providing immediate feedback during the learning process, pinpointing weaknesses requiring attention, and prompting adjustments in learning strategies – a key process in self-regulated learning – potentially explaining the link to achievement. These findings suggest ChatGPT’s potential as a supplementary formative assessment tool, suitable for practical integration into chemistry classrooms.

1 Introduction

Stoichiometry is a fundamental topic in chemistry but is widely regarded as particularly difficult to learn in higher education. 1 , 2 , 3 Its complexity stems from the need to integrate conceptual understanding across microscopic and macroscopic levels while applying calculation principles, unit conversions, and systematic problem-solving. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Students who lack foundational knowledge (e.g., mole concept, unit conversions) often struggle to progress to more complex topics. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 These challenges are especially concerning for pre-service science teachers – undergraduate students enrolled in a teacher education program, who are simultaneously developing their science content knowledge and pedagogical skills. Their incomplete understanding can hinder both their ability to convey this complex content accurately and their capacity to transform content knowledge into effective teaching strategies, potentially affecting the quality of future science education. 16 , 17

Formative assessment plays a crucial role in addressing the challenges of learning stoichiometry by providing timely and specific feedback that helps students identify and begin correcting misconceptions during instruction. 18 , 19 , 20 This correction of misconceptions during instruction is an essential step in a conceptually sequential topic where foundational understanding is critical for subsequent learning. 20 , 21 However, implementing effective formative assessment is often constrained by practical challenges, especially in large classes where providing timely, individualized feedback is difficult due to instructor workload, time limitations, and the complexity of analyzing numerous student responses. 20 , 22

The challenge of providing timely, individualized feedback in formative assessment, especially for complex subjects like stoichiometry, has spurred researchers to explore technological innovations such as Generative Artificial Intelligence (Gen AI). Current literature indicates that Gen AI is a pivotal factor in educational transformation, with broad potential from creating personalized content to reducing instructor workloads. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 However, its most frequently cited capability is providing immediate and personalized feedback, 34 , 35 , 36 a function that is critical for empowering students to more effectively monitor and modify their learning approaches through enhanced self-regulated learning processes. 37 , 38 To investigate this capability within a complex scientific domain, this study explores the use of ChatGPT as a direct instrument for gauging formative understanding in stoichiometry learning. While acknowledging the availability of other Gen AI tools (such as DeepSeek, Gemini, and Grok), ChatGPT (GPT-3.5, free version) was deliberately chosen for this investigation. This decision was based on its practical advantages: high accessibility, inherent user-friendliness, and considerable prevalence among the student population. 39 , 40 , 41 Furthermore, its common presence on students’ mobile phones simplifies its seamless integration into the existing classroom workflow.

Recent studies, such as Usher’s comparison of rubric-informed AI, peer, and instructor feedback on project work, highlight Gen AI’s potential in learning assessments. 42 However, ChatGPT’s specific role as a direct formative assessment tool, particularly in contexts where pre-service science teachers interact with it while learning complex materials like stoichiometry, represents an emergent area of inquiry. Consequently, it remains unclear how receiving immediate feedback to assess understanding at that moment would impact their learning in this context. A key area of concern is the concordance between ChatGPT’s and human instructors’ assessments, especially when ChatGPT assesses understanding without a specific rubric. Critical gaps also exist in understanding the pre-service science teachers’ experience with ChatGPT as a formative assessment tool. This includes understanding their perceptions of its advantages and disadvantages, as well as how they act on the feedback received. Such insights are essential to guide the effective and practical use of this technology in real classroom settings. To address the above-mentioned research gaps, this study aims to investigate the following research objectives (ROs):

RO1: To examine the relationship between the ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores in the stoichiometry unit.

RO2: To examine the relationship between the ChatGPT assessment scores and the instructor assessment scores in the stoichiometry unit.

RO3: To explore the perceptions of pre-service science teachers regarding the use of ChatGPT as a formative assessment tool within the stoichiometry unit, specifically seeking in-depth explanations for the relationship observed in RO1 between ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores.

For clarity, ChatGPT assessment scores refer to the scores students received after inputting their answers and using a standardized prompt requesting the ChatGPT to assess their level of understanding on a percentage scale.

The findings of the study are expected to provide valuable insights to instructors and researchers attempting to effectively utilize Gen AI to support formative assessment in real classroom environments. Furthermore, these perspectives should provide guidance to AI system developers to further improve systems that will better support practical learning and learning processes.

2 Research methodology

2.1 Research design

This study uses a mixed-method research design, in particular an explanatory sequential design. 43 The overall research process is illustrated in Figure 1. The aim was to investigate the use of ChatGPT as a tool for assessing formative understanding in a stoichiometry unit. The initial phase of this research involved collecting quantitative data and using a correlational research design. This phase aimed to examine the relationship between the ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores (RO1), as well as the relationship between the ChatGPT assessment scores and the instructor assessment scores (RO2). These quantitative data were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rs) to determine the magnitude and direction of the relationships between these variables.

Explanatory sequential mixed-methods research design employed in the study.

The subsequent qualitative phase was designed to explain the quantitative findings, focusing specifically on the relationship between ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores as identified in RO1. Semi-structured interviews served as the primary method for exploring pre-service science teachers’ perceptions of utilizing ChatGPT as a formative assessment tool (addressing RO3). The interview transcripts were subjected to thematic analysis to identify key themes reflecting students’ perceptions and experiences. 44 Ultimately, these qualitative findings were integrated to provide in-depth explanations that enrich the interpretation and contextual understanding of the quantitative data.

2.2 Participants

The participants in this study were drawn from a cohort of 62 first-year pre-service science teachers enrolled in the Chemistry for Teachers 1 course within a faculty of education (equivalent to a school or college of education) at a university in Bangkok, Thailand. For clarity, these participants are hereafter referred to as students. The term pre-service science teachers will be retained where their professional context is relevant. The learning activities described in Section 2.3 were a part of the standard coursework for all enrolled students. Prior to the study commencing, all students received an information sheet and consent form outlining the research objectives, procedures, and their rights as participants. It was explicitly stated that participation was voluntary, that students could withdraw their consent for data use at any time without penalty, and that their decision would not affect course grades or standing (see Research Ethics and Informed Consent sections for details).

For the final data analysis, data were included only from students who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) remained enrolled in the course throughout the instructional period and (2) completed all 10 learning processes. A total of 38 students who met these criteria also provided signed voluntary informed consent for their data to be used in the study. Therefore, the complete dataset from these 38 students was used for the final analysis. Detailed demographics of the students are presented in Supplementary Information (Section S3).

For the qualitative phase, students from the main cohort of 38 were invited to voluntarily participate in semi-structured interviews. From those who provided prior consent and were available, students were purposefully selected using a maximum variation strategy to capture diverse perspectives in terms of achievement level and gender. The final number of interview participants was determined during data collection based on thematic saturation (see Section 2.5 for details).

2.3 Learning design and ChatGPT integration

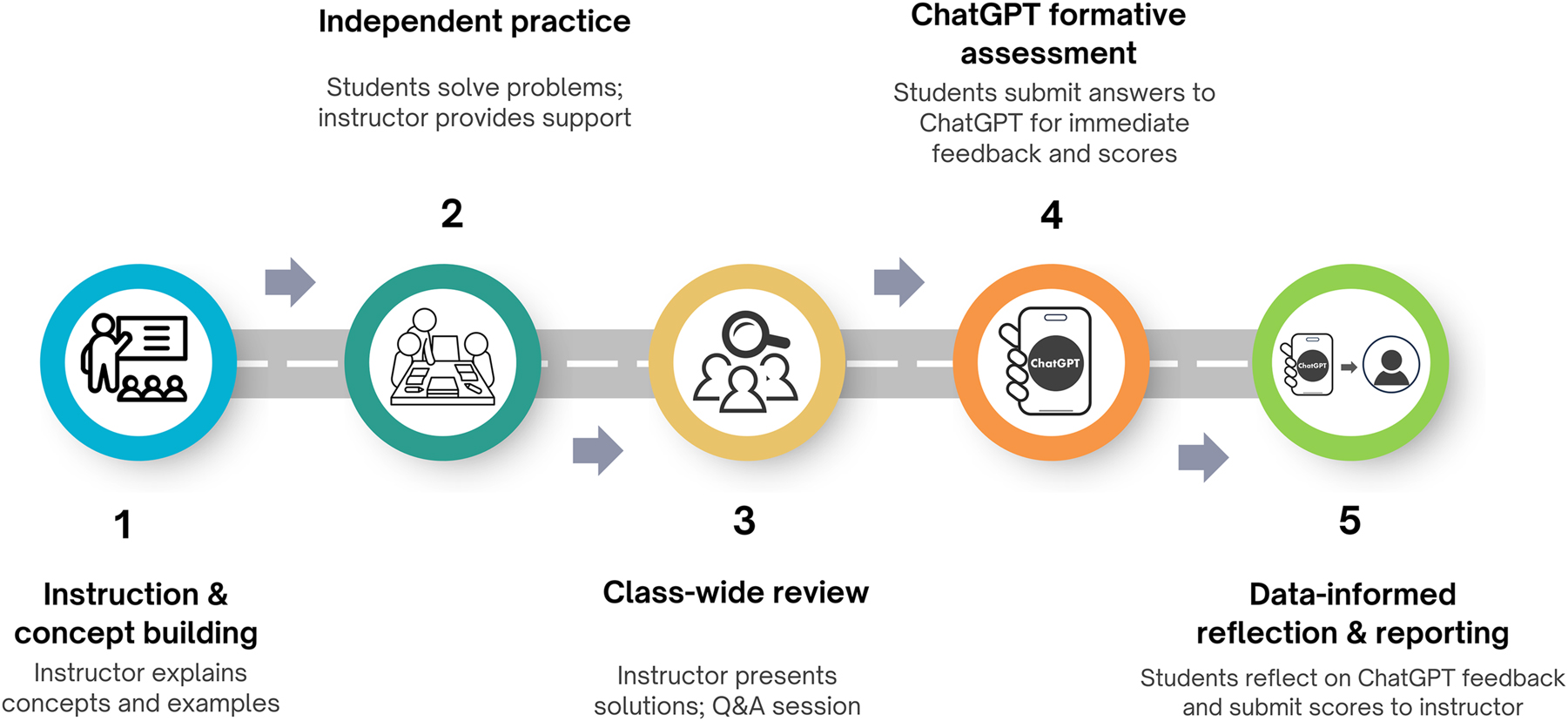

The instructional method employed for the stoichiometry unit was a structured learning process grounded in the principles of formative assessment. 45 , 46 This approach emphasizes the continuous monitoring of learner understanding and the provision of individualized feedback to enhance learning throughout the instructional process. The stoichiometry unit’s instructional content was primarily based on the textbook chemistry, 47 adapted to align with the Thai higher education curriculum context. This content was divided into 10 distinct subtopics. For each subtopic, the instructor established clear Lesson Learning Outcomes (LLOs) to define specific learning objectives and ensure that they are consistent with the course learning outcomes (a detailed description of LLOs is provided in Table S1, Supplementary Information). This five-step ChatGPT-enhanced formative assessment process is illustrated in Figure 2 (detailed descriptions of each step are provided in Section S2 of the Supplementary Information). For each of the 10 subtopics, the learning process began with Instruction & Concept Building, followed by Independent Practice and a Class-wide Review.

ChatGPT-enhanced formative assessment learning process for stoichiometry unit.

The final two steps centered on the ChatGPT interaction. In the fourth step, ChatGPT Formative Assessment, students were first presented with a distinct set of formative conceptual understanding assessment questions. They then submitted their answers to these questions to ChatGPT using the following standardized prompt:

Assess what percentage I understand for each question, provide suggestions for each, and assess my overall understanding percentage for this topic, offering recommendations for learning improvement.

A key methodological choice was the deliberate exclusion of a specific scoring rubric from the prompt given to ChatGPT. This was to ensure that the AI’s assessment was an authentic assessment based on its internal models, rather than a test of its ability to follow prescribed criteria. This approach allowed for a genuine benchmark of its Large Language Model (LLM) capabilities against human assessment.

In the final step, Data-Informed Reflection & Reporting, students used the ChatGPT-generated feedback and scores to reflect on their understanding and were required to report their scores and submit screenshots of the entire interaction via a designated Google Form. This five-step learning process was repeated for each of the 10 subtopics over a four-week instructional period. It should be noted that this instructional design did not involve instructor-led reteaching of a subtopic. Instead, the formative adjustment was designed to occur at the student level, where students were expected to use the Gen AI feedback to self-regulate and adapt their understanding and learning strategies. Upon completion of all 10 learning processes, all participating students undertook the final achievement test.

2.4 Instruments

The instruments employed in this research included (1) a 30-item multiple-choice stoichiometry achievement test, (2) 10 sets of formative conceptual understanding assessment questions, and (3) a semi-structured interview protocol. The development, validation, and reliability details for each instrument are fully documented in the Supplementary Information (Sections S4–S6), which also includes the complete interview protocol and examples of the formative conceptual understanding questions.

2.5 Data collection

The quantitative data for RO1 and RO2 were gathered during the four-week instructional period. The ChatGPT assessment scores were collected via designated Google Forms after each of the 10 learning processes described in Section 2.3. Upon completion of the entire instructional period, the final achievement scores were collected from all participants.

To fulfill RO2, student responses to the formative conceptual understanding assessment questions (captured as screenshots of their interactions with ChatGPT and subsequently collected via Google Forms) were assessed by three chemistry instructors (the course instructor and two external chemistry instructors). Each expert independently assessed responses using an identical scoring rubric developed by the course instructor. To establish Inter-Rater Reliability (IRR), the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was calculated (two-way mixed effects, absolute agreement). The ICC for average measures (N = 3 raters) was 0.973 (95 % CI [0.951, 0.985], p < 0.001), indicating excellent inter-rater reliability. 48 After high IRR was confirmed, the scores assigned by each instructor based on the rubric were converted into percentages. For each student, the percentage scores from the three experts were then averaged. This final averaged percentage value represented the instructor assessment score and was then employed in the correlation analysis against the ChatGPT assessment score to fulfill RO2.

Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews. As described in Section 2.2, data collection and preliminary analysis were conducted concurrently in an iterative process. Interviewing continued until thematic saturation was reached, which was determined when no new significant themes emerged from the data after the 13th interview. 49 The interviews were conducted face-to-face using a semi-structured protocol, with probing techniques employed to encourage open sharing. Each session lasted approximately 40–45 min, was audio-recorded with permission, and was subsequently transcribed verbatim for analysis. In total, 13 students participated in the interviews, comprising high-achieving (n = 4), medium-achieving (n = 5), and low-achieving students (n = 4) based on their midterm scores, with seven males and six females.

2.6 Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis began with testing the normality of the data distribution for the primary variables. These variables included the ChatGPT assessment scores, final achievement scores, and the instructor assessment scores. This assessment was conducted utilizing the Shapiro-Wilk test. The results indicated that the distributions for all three variables significantly deviated from normality (p < 0.05). Based on this finding of non-normality, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) was chosen to analyze variables according to RO1 (relationships between ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores) and RO2 (relationship between ChatGPT assessment scores and instructor assessment scores). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Data from semi-structured interviews were analysed using thematic analysis, following the six-phase approach outlined by Braun and Clarke, 44 , 50 to explore pre-service science teachers’ perceptions (RO3). This method was chosen for its flexibility in systematically identifying themes from qualitative data. The process involved (1) data familiarization (including transcription and repeated reading), (2) generating initial codes across the dataset, (3) searching for potential themes, (4) reviewing and refining those themes, (5) defining and naming the final themes, and (6) producing the final analysis. The analytical process was rigorous and iterative, occurring concurrently with data collection as described in Section 2.5. After an initial set of interviews was transcribed, the three researchers independently generated initial codes. The team then convened to compare these early codes, discuss discrepancies, and develop a preliminary codebook. This codebook was applied to the initial transcripts and then progressively refined as more interviews were conducted and analysed. This iterative cycle of independent coding, team discussion, and codebook refinement continued throughout the data collection period, ensuring that the final themes were robust interpretations grounded in the participants’ collective experiences. Further details on data organization and the consensus-building procedure are provided in Supplementary Information (Section S7).

3 Results

3.1 Quantitative results

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients that explain the relationships between the main variables in the study are shown in Table 1. For the first objective, the correlation between the ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores in the stoichiometry unit was analyzed via Spearman’s correlation. A strong positive correlation (rs = 0.670, p < 0.001) was found, indicating that students with higher ChatGPT assessment scores – reflecting a greater formative understanding – tended to perform better on the final achievement test.

Spearman’s correlations between ChatGPT assessment scores, final achievement scores, and instructor assessment scores.

| Variables analyzed | Final achievement scores | Instructor assessment scores |

|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT assessment scores | 0.670** | 0.882** |

-

**Correlations are statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Regarding the second research objective, which explored the relationship between assessment outcomes from ChatGPT and those from human instructors, the analysis found that the ChatGPT assessment scores demonstrated a very strong, statistically significant positive correlation with the instructor assessment scores (rs = 0.882, p < 0.001) (see Table 1). This result indicates a high degree of agreement between the formative assessment of understanding conducted through ChatGPT and the assessment conducted by human instructors.

3.2 Qualitative results

Thematic analysis was conducted on the interview data, exploring pre-service science teachers’ perceptions regarding the use of ChatGPT as a formative assessment tool within the stoichiometry unit. The primary aim of this analysis was to provide in-depth explanations for the observed correlation between the ChatGPT assessment scores and the final achievement scores. This analysis revealed four key themes, as follows:

3.2.1 Theme 1: perceived utility of ChatGPT for personalized diagnosis and learning enhancement

Students identified ChatGPT’s primary utility as a powerful tool for personalized diagnosis that provided immediate, actionable feedback. This capability allowed them to instantly identify and understand their errors, guiding subsequent review, as illustrated by the following students (S):

S08 (medium-achieving): “…if we answer a question incorrectly, ChatGPT tells us right away where we went wrong and suggests what to adjust to make the answer 100% correct…”

S02 (high-achieving): “ChatGPT gives immediate results showing where the mistake is, allowing me to correct misunderstandings right away.”

These statements indicate that students valued ChatGPT’s ability to serve as a diagnostic tool, identifying gaps in understanding (S05, S08), and to provide rapid feedback (S02). This ability was perceived as stimulating review (S06) and fostering more targeted and personalized learning experiences. Ease of access was another factor students perceived as beneficial (S01). Additional representative quotes are presented in supplementary Table S3.

3.2.2 Theme 2: limitations and reliability concerns of ChatGPT as an assessment tool

While acknowledging ChatGPT’s utility, students also voiced significant concerns regarding its accuracy, reliability, and limitations as an assessment tool, impacting their trust. Key limitations centered on two main areas:

Firstly, assessment accuracy was a prominent concern, particularly for stoichiometry problems involving calculations and chemical complexities. Students perceived ChatGPT as overly strict on minor details like decimal places, contrasting with instructor flexibility.

S05 (medium-achieving): “ChatGPT… is sometimes strict about the decimal places in the answer, unlike the instructor who focuses more on the thought process.”

Other reported inaccuracies included instances of ChatGPT overestimating understanding or failing to detect errors such as missing units (S01, S02, S10). Furthermore, the issue of discrepancies between the methods or formulas utilized by ChatGPT compared to those explicitly taught during classroom instruction was identified as another limitation. One student (S07) noted that such differences could potentially lead to confusion or a lack of understanding regarding the solution steps presented by the Gen AI.

Secondly, students encountered technical reliability and usability challenges. Common issues included processing delays, system errors, or interruptions during use (S03, S06, S11), leading to wasted class time. Usability constraints, such as typed text disappearing when switching applications, also created difficulties.

S13 (low-achieving): “When I was doing a calculation… I had to swipe away… and then when I came back, the text I had already typed was completely gone.”

These identified limitations in both assessment accuracy and technical reliability (see Table S4, Supplementary Information for additional illustrative quotes) necessitated more critical usage and accuracy checks by students, potentially impacting their confidence in the tool.

3.2.3 Theme 3: ChatGPT’s impact on confidence, self-reflection, and learning strategies.

Analysis of the interview data revealed that ChatGPT was more than a feedback tool; it acted as a significant catalyst for students’ internal learning processes. The interaction influenced their behaviors in three key ways: it boosted their academic confidence, triggered critical self-reflection, and stimulated concrete adaptations to their learning strategies.

Firstly, students reported that receiving affirmation from ChatGPT for correct answers directly boosted their confidence in what they had learned (S12, S03, see Table S4, Supplementary Information for illustrative quotes).

The second aspect was that assessment outcomes functioned as a catalyst for self-reflection. When students encountered errors or received an unsatisfactory percentage generated by ChatGPT, they tended to revisit and reconsider their level of understanding and did not overlook areas where they lacked comprehension (S06, S10; see Table S5). For example, S07 (medium-achieving) stated:

I went back to review the points where I didn’t do well… I consider it an important turning point that made me adjust my own way of learning.

Thirdly, and significantly, assessment results from ChatGPT stimulated adaptations in learning strategies. Many students reported utilizing the provided feedback to plan their reading more effectively, focus practice on weaker topics, and shift their learning orientation from rote memorization towards achieving a deeper understanding of underlying thought processes.

S03 (high-achieving): “Before… I usually wouldn’t know where to start reading… but once ChatGPT helped assess my understanding, I could make my reading more targeted…”

S08 (medium-achieving): “So, I then used that to adjust my studying, like reading more books, practicing the problems again where I made mistakes…”

3.2.4 Theme 4: students’ perceptions of the relationship between ChatGPT assessment and final achievement

A key interview finding was students’ perceived connection between ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores. The majority viewed ChatGPT’s assessment as a preliminary indicator of their understanding and potential exam performance. Some noted a close alignment between AI-assessed scores and exam results (e.g., S03), exemplified by S12 (low-achieving), whose exam performance on calculation problems mirrored ChatGPT’s prior assessment.

S12 (low-achieving): “There is a relationship, yes. Like for the stoichiometry topic… the parts that were calculations, I answered incorrectly very often, and then during the actual exam, it turned out exactly like that. Meaning, I understood the theory but messed up on the calculations. It matched exactly what ChatGPT had assessed.”

However, students also recognized this relationship was not perfectly consistent, attributing discrepancies to other factors. Crucially, their own effort and active use of feedback were seen as key variables influencing alignment.

S04 (high-achieving): “I really used the information and feedback from ChatGPT to actually build upon it – meaning, it wasn’t just looking at the percentage and letting it pass, but using it as a guide for fixing my own weak points… which, I think, having the discipline to review and the determination to improve my learning based on the feedback received, those are important variables that made the results end up being quite aligned.”

Moreover, other factors such as the students’ psychological state, stress levels, or test anxiety (S09, S10) were also identified as potential variables contributing to inconsistencies between the two sets of assessment scores (additional examples in Table S6). These perspectives reveal a nuanced understanding among students: while they clearly perceived ChatGPT as a valuable assessment tool, they also recognized that its effectiveness was mediated by their own actions, preparedness, and other complex factors.

4 Discussion

4.1 Explaining the relationship between ChatGPT assessment and achievement through pre-service science teacher perceptions

The strong positive correlation between the ChatGPT assessment scores and final achievement scores (rs = 0.670) indicates that students who achieved higher assessment scores from ChatGPT during instruction also tended to score higher on the final achievement test. With Spearman’s coefficient of determination (rs2 = 0.45), approximately 45 % of the variance in final achievement scores was associated with ChatGPT score variance, signifying its role as an important indicator, although other factors account for ∼55 %. This strong positive correlation suggests ChatGPT demonstrates considerable capability in assessing student understanding in ways that align with final achievement outcomes. This finding is consistent with recent research by Chang and Chien, 51 who also found a positive relationship between scores from a Gen AI-powered quiz platform and post-learning achievement in a programming course.

While correlation does not imply causation, qualitative data from thematic analysis of pre-service science teacher interviews offered in-depth explanations for potential mechanisms underlying this quantitative relationship (addressing RO3), as detailed below.

Firstly, the capability of ChatGPT to provide immediate diagnosis and feedback (Theme 1) was a significant factor. Students reported that the rapid identification of their conceptual misunderstandings (S08, S02) was highly beneficial. This enabled them to confront their errors and begin the process of conceptual correction before a misunderstanding could become more entrenched. This process, where immediate feedback directly fuels conceptual change, not only aligns with the core principles of effective formative assessment 45 but is also consistent with existing research on Gen AI’s capacity to deliver timely, adaptive feedback that can effectively diagnose specific student weaknesses. 52 , 53 , 54

Secondly, ChatGPT’s influence in stimulating key processes of Self-Regulated Learning (SRL), specifically self-review and the adjustment of learning strategies (Theme 3), provides another explanatory mechanism. Assessment results from ChatGPT prompted self-reflection and self-evaluation. When students received unsatisfactory scores, they tended to monitor their understanding, re-analyze areas of difficulty, and begin the process of correcting misconceptions to deepen comprehension (S06, S07, S10) – core SRL components. 55 , 56 Moreover, a significant influence involved fostering strategy adaptation; students utilized ChatGPT’s feedback and scores to inform study planning and enhance review effectiveness (S03, S08), often focusing practice on personal weaknesses. Such adjustments potentially facilitated a shift from rote memorization towards genuine conceptual understanding, aligning with research linking adaptive strategy use post-assessment to enhanced comprehension. 57 , 58 Therefore, ChatGPT appeared to act as a technological scaffold supporting multiple facets of SRL: 37 , 59 students used its feedback for self-monitoring and evaluation, leading to strategic planning and behavioral adaptation. This AI-supported SRL process confirms Gen AI’s potential in fostering crucial learning skills 59 , 60 , 61 and serves as a key mechanism linking formative assessment to final learning achievement.

Crucially, the significance of this pre-service science teacher cohort is central to the study’s findings, particularly regarding the affective and motivational dimensions of their SRL. 62 The feedback from ChatGPT functioned as a powerful emotional driver precisely because the process was not merely about academic performance but was deeply intertwined with their emerging professional identities. This is powerfully articulated by student S08, who viewed unsatisfactory performance not as a simple academic setback, but as a direct challenge to their future role as a teacher:

“…if I can’t solve these problems, but I’m going to become a teacher, what on earth will I teach my students in the future? So, because of that, I just have to try harder; I have to practice more.”

This quote reveals a unique motivational mechanism where their professional identity fueled a commitment to self-improvement. 63 , 64 For this specific cohort, therefore, the entire formative assessment loop was contextualized by their developing identity, providing a compelling explanation for the study’s findings that may not manifest in other student populations.

The final point contributing to this explanation relates to students’ perception of the connection between ChatGPT assessment scores and their final achievement scores (Theme 4). Most students personally perceived this relationship, often viewing ChatGPT’s assessment as a preliminary indicator of their understanding and potential exam performance. Their concrete examples of this consistency provide experiential validation, lending weight and meaning to the statistical correlation, demonstrating it as an observable and meaningful phenomenon for learners. This perceived connection may then motivate students to engage seriously with ChatGPT’s formative assessment and diligently utilize its feedback (Theme 3) due to the potential link to exam scores. This aligns with findings by Dahri et al. 65 and Amin et al. 66 on trust and confidence in Gen AI accuracy influencing feedback use, and with Uppal and Hajian 67 on perceived AI utility correlating with better outcomes. However, students were also cognizant of other factors influencing their exam scores, including personal effort and preparation (S04, S11), test-taking conditions like stress (S09, S10), and potentially the inherent limitations of the AI assessment itself, such as perceived inaccuracies or discrepancies in its assessment methods (as discussed in Theme 2). This awareness corresponds with the coefficient of determination (rs2 = 0.45), which indicated that ∼45 % of the variance in final achievement scores was associated with ChatGPT score, confirming other personal, contextual and tool-related factors contribute ∼55 %. Thus, while Theme 4’s learner perception may not be the primary driver, it likely plays an important supporting role by providing experiential validation, adding meaning to the assessment, and reinforcing motivation.

Synthesizing these mechanisms reveals the cohesive logic behind the observed correlation. The immediate, diagnostic feedback from ChatGPT (Theme 1) acted as a catalyst for an active cycle of SRL (Theme 3), amplified by the students’ perception of the value of this process for their final performance (Theme 4). Students who fully engaged in this motivation-enhanced feedback loop were empowered to build a more robust conceptual understanding – rather than ChatGPT being the direct origin of that understanding. This deeper understanding is the common underlying factor, meaning high ChatGPT scores and strong final test results should be viewed as parallel outcomes of the same successful learning process. Therefore, the ChatGPT assessment score functions as a powerful indicator of final achievement, not because it directly causes improved performance, but because it effectively captures the artifact of a successful, self-aware, and self-regulated learning process.

4.2 Agreement between ChatGPT and instructor assessments

Analysis of the ChatGPT assessment scores and the instructor assessment scores revealed a very high positive correlation (rs = 0.882), indicating a very high level of agreement. However, interpreting this correlation requires considering fundamental differences in assessment processes: human instructors used an explicitly defined scoring rubric, whereas ChatGPT leveraged its LLM capabilities and a standardized prompt, without this specific rubric. This high agreement is therefore particularly remarkable. A possible factor contributing to this level of agreement may be the nature of the formative assessment questions and expected answers. The questions, while primarily in short-answer or well-defined answer formats, were designed to assess conceptual accuracy and response completeness. These are dimensions that both sophisticated LLMs and human instructors may be capable of assessing with considerable alignment. 29 , 68 This implies ChatGPT can capture an overall assessment of understanding largely consistent with human assessment. This aligns with Fernández et al., 69 who found a positive rubric-free ChatGPT-human correlation for university entrance exams, and Morjaria et al. 29 for medical short answers. Therefore, this study contributes additional supporting evidence that ChatGPT, even without explicit rubrics, demonstrates considerable potential for performing human-consistent assessments. This outcome also resonates with the broader educational technology trend of reducing instructor workload. 42 , 70 , 71

It is noteworthy that this correlation (rs = 0.882) was considerably higher than the correlation with final achievement scores (rs = 0.670). This difference is likely because the former comparison involved both AI and instructors assessing the exact same set of formative, open-ended conceptual questions, enabling a direct comparison of assessment capabilities. In contrast, the latter comparison involved different instruments – the formative questions versus a summative, multiple-choice achievement test – which measure broader cumulative knowledge influenced by additional factors beyond formative assessments.

While the level of agreement between the two assessment formats was very high (rs = 0.882), qualitative interview data provided valuable perspectives on students’ perceptions of ChatGPT’s capabilities, highlighting perceived limitations and accuracy concerns (Theme 2). Specifically, students noted issues such as excessive strictness with calculation details (e.g., decimals, S05), perceived overestimation of understanding (S02), failure to identify errors like missing units (S10), or ChatGPT utilizing different problem-solving methods (S07). Given the very high overall correlation, the impact of these reported limitations on understanding assessment scores may be limited. Nevertheless, these perceived shortcomings clearly reflect areas where AI systems could be further developed to achieve flexibility and contextual understanding in specialized domains like chemistry, approaching that of human instructors. 72 , 73

5 Conclusions

This mixed-methods study examined ChatGPT’s role as a formative assessment tool in a university stoichiometry unit. Quantitative findings showed strong correlations between ChatGPT assessment scores and both final achievement (RO1) and instructor assessment scores (RO2). Qualitative insights (RO3) revealed that ChatGPT served as a powerful learning scaffold, delivering immediate feedback that initiated cycles of self-reflection and strategic adaptation – processes uniquely fueled by pre-service science teachers’ emerging professional identities. Students also viewed ChatGPT’s assessment as a meaningful indicator of exam performance, further explaining the strength of the observed correlations.

While this study employed stoichiometry as the research context, its findings reveal fundamental principles of Gen AI-driven formative assessment that transcend disciplinary boundaries. The core mechanism – immediate feedback stimulating self-regulated learning (SRL) – is not content-specific but a universal pedagogical process. Stoichiometry served as a robust exemplar of conceptually demanding content, making it an ideal case to test this mechanism. Therefore, these findings position our work not as a chemistry-specific intervention but as a broadly applicable framework where AI-enhanced assessment can improve learning outcomes across complex domains, offering a transferable model for diverse disciplines.

6 Limitations of this study and future research

The findings derived from this study are subject to several key limitations, which consequently highlight potential directions for future research endeavors, as outlined below.

Firstly, a primary limitation stems from the study’s reliance on a specific version of the AI – the free, commercial ChatGPT-3.5 – and its inherent operation without an explicit, researcher-defined scoring rubric. This model’s performance constraints directly influenced the research design, restricting question formats primarily to short-answer types, which could not fully assess complex problem-solving steps. These limitations were also reflected in the qualitative findings, where students noted shortcomings such as inconsistent assessment of procedural details like unit usage or decimal strictness. Therefore, the findings might differ from those obtained with newer, subscription-based AI models with enhanced capabilities, and a potential novelty effect may have also influenced student perceptions. Future research should investigate the performance of different AI versions and focus on developing feedback approaches that align more effectively with specific instructional contexts. Longitudinal studies are also recommended to ascertain sustained effects of AI integration and track changes in student perceptions/behaviors with increased familiarity.

Secondly, the use of a commercial third-party tool (ChatGPT) raises significant data privacy considerations. Although participants were explicitly instructed not to include personally identifiable information, their academic work was still processed on external servers beyond the researchers’ control. This remains an inherent ethical limitation when employing public-facing AI in educational research. Future studies could mitigate this by exploring the use of institutional AI models where data privacy and security can be more rigorously controlled.

Thirdly, the study’s design may be subject to a self-selection bias. As participation in the ChatGPT activities was a course requirement, and research inclusion required voluntary informed consent, the final sample consists of participants who were ultimately willing to engage with the technology and the research process. Therefore, the findings related to student perceptions (RO3) may not fully capture the perspectives of students who would be unwilling to use ChatGPT in an educational setting. The views of this unwilling cohort could differ significantly, which may limit the transferability of these findings to other student groups or contexts where students may be less willing to engage with AI technologies.

Finally, while the core pedagogical mechanisms identified in this study are believed to be broadly applicable, the findings are based on a specific cohort of pre-service science teachers in a chemistry context. Future research should seek to validate these findings across diverse student populations and academic disciplines to empirically establish the generalizability proposed in the conclusion.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Faculty of Education, Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University (SSRU) for their substantial support with resources, personnel, and a research-conducive environment. We also extend our deep appreciation to the undergraduate pre-service science teachers who participated in this study, particularly those who contributed their time and insights during the interviews. Their willingness to participate was instrumental to the successful completion of this study.

-

Research ethics: This research was conducted in strict accordance with established ethical standards. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University (SSRU EC) on 27 January 2025 (Approval Code: COE 2–041/2025). All personally identifiable information pertaining to the participants was maintained in strict confidence and securely protected throughout the research process.

-

Informed consent: All individuals participating in this research provided voluntary Informed consent. Participants were explicitly informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without incurring any penalty or negative consequences. A translated copy of the full Information Sheet and Consent Form provided to participants is available in the Supplementary Information (Section S10).

-

Author contributions: J.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing–Original Draft, Writing–Review & Editing, Supervision. S.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation. M.I.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing–Review & Editing. P.C.: Investigation, Data Curation, Validation, Writing–Original Draft, Writing–Review & Editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: During the preparation of this manuscript, Gemini (version 2.5 Pro) was employed solely to improve language clarity, grammar, and readability. AI tools were not involved in data analysis, interpretation, or the development of academic content. As the authors, we take full responsibility for the content and accuracy of this published research.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: The raw datasets generated and analysed during the current study (e.g., individual student responses, full interview transcripts) are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and participant confidentiality. Aggregated participant demographic data are presented within the main manuscript. Representative anonymized participant quotes illustrating key findings are included in both the main manuscript and the accompanying Supplementary Information. Further anonymized datasets supporting the study’s conclusions are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, subject to Institutional Review Board approval where necessary.

References

1. Marais, F.; Combrinck, S. An Approach to Dealing with the Difficulties Undergraduate Chemistry Students Experience with Stoichiometry. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2009, 62, 88–96. https://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/sajc/v62/17.pdf (accessed 2025-05-21.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Hosbein, K.; Walker, J. Assessment of Scientific Practice Proficiency and Content Understanding Following an Inquiry-based Laboratory Course. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99 (12), 3833–3841. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.2c00578.Suche in Google Scholar

3. Rosa, V.; States, N. E.; Corrales, A.; Nguyen, Y.; Atkinson, M. B. Relevance and Equity: Should Stoichiometry be the Foundation of Introductory Chemistry Courses? Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2022, 23 (3), 662–685. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1RP00333J.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Johnstone, A. H. Teaching of Chemistry-Logical or Psychological? Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2000, 1 (1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1039/A9RP90001B.Suche in Google Scholar

5. Talanquer, V. Macro, Submicro, and Symbolic: the Many Faces of the Chemistry “Triplet”. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2011, 33 (2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690903386435.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Huddle, P. A.; Pillay, A. E. An In-depth Study of Misconceptions in Stoichiometry and Chemical Equilibrium at a South African University. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1996, 33 (1), 65–77. 2-N https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199601)33:1<65::AID-TEA4>3.0.CO.10.1002/(SICI)1098-2736(199601)33:1<65::AID-TEA4>3.3.CO;2-USuche in Google Scholar

7. Sanger, M. J. Evaluating Students’ Conceptual Understanding of Balanced Equations and Stoichiometric Ratios Using a Particulate Drawing. J. Chem. Educ. 2005, 82 (1), 131–134. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed082p131.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Furió, C.; Azcona, R.; Guisasola, J. The Learning and Teaching of the Concepts Amount of Substance and Mole: a Review of the Literature. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2002, 3 (3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1039/B2RP90023H.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Özmen, H.; Ayas, A. Students Difficulties in Understanding of the Conservation of Matter in Open and Closed-System Chemical Reactions. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2003, 4 (3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1039/B3RP90017G.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Schmidt, H.-J.; Jignéus, C. Students’ Strategies in Solving Algorithmic Stoichiometry Problems. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2003, 4 (3), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1039/B3RP90018E.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Gulacar, O.; Bowman, C. R. Determining what Our Students Need Most: Exploring Student Perceptions and Comparing Difficulty Ratings of Students and Faculty. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2014, 15 (4), 587–593. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RP00055B.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Mandina, S.; Ochonogor, C. E. Recurrent Difficulties: Stoichiometry Problem-Solving. Afr. J. Educ. Studies Math. Sci. 2018, 14 (1), 25–31; https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/95125. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Bopegedera, A. M. R. P. Preventing Mole Concepts and Stoichiometry from Becoming “Gatekeepers” in First Year Chemistry Courses In Enhancing Retention in Introductory Chemistry Courses: Teaching Practices and AssessmentsACS Symposium Series 1330; Hartwell, S. K.; Gupta, T., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2019, pp. 121–136.10.1021/bk-2019-1330.ch008Suche in Google Scholar

14. Gulacar, O.; Mann, H. K.; Mann, S. S.; Vernoy, B. J. The Influence of Problem Construction on Undergraduates’ Success with Stoichiometry Problems. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 867. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120867.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Kimberlin, S.; Yezierski, E. Effectiveness of Inquiry-based Lessons Using Particulate Level Models to Develop High School Students’ Understanding of Conceptual Stoichiometry. J. Chem. Educ. 2016, 93 (6), 1002–1009. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.5b01010.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Adu-Gyamfi, K. Pre-Service Teachers’ Conception of an Effective Science Teacher: the Case of Initial Teacher Training. J. Turk. Sci. Educ. 2020, 17 (1), 40–61. https://doi.org/10.36681/tused.2020.12.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Frågåt, T.; Henriksen, E.; Tellefsen, C. Pre-Service Science Teachers’ and In-service Physics Teachers’ Views on the Knowledge and Skills of a Good Teacher. Nord. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2021, 17 (3), 277–292. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.7644.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract 1998, 5 (1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Black, P.; Wiliam, D. Developing the Theory of Formative Assessment. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account 2009, 21 (1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Morris, R.; Perry, T.; Wardle, L. Formative Assessment and Feedback for Learning in Higher Education: a Systematic Review. Rev. Educ. 2021, 9 (3), e3292. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3292.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Sortwell, A.; Trimble, K.; Ferraz, R.; Geelan, D. R.; Hine, G.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Xuan, Q.; Gkintoni, E. A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses on the Impact of Formative Assessment on K-12 Students’ Learning: toward Sustainable Quality Education. Sustainability 2024, 16 (17), 7826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16177826.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Panadero, E.; Yang, M.; Yang, L.; Lao, H. A. Systematic Review on Factors Influencing Teachers’ Intentions and Implementations Regarding Formative Assessment. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract 2021, 28 (3), 228–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2021.1884042.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Mittal, U.; Sai, S.; Chamola, V.; Sangwan, D. A Comprehensive Review on Generative AI for Education. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 142733–142759. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3468368.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Ogunleye, B.; Zakariyyah, K. I.; Ajao, O.; Olayinka, O.; Sharma, H. A Systematic Review of Generative AI for Teaching and Learning Practice. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 636. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14060636.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Yuriev, E.; Wink, D. J.; Holme, T. A. The Dawn of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Chemistry Education. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (8), 2957–2959. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00836.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Urban, M.; Děchtěrenko, F.; Lukavský, J.; Hrabalová, V.; Svacha, F.; Brom, C.; Urban, K. Chatgpt Improves Creative Problem-Solving Performance in University Students: an Experimental Study. Comput. Educ. 2024, 215, 105031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2024.105031.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Clark, T. M. Investigating the Use of an Artificial Intelligence Chatbot with General Chemistry Exam Questions. J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100 (5), 1905–1916. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c00027.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Gonçalves Costa, G.; Nascimento Júnior, J. D.; Mombelli, M. N.; Girotto Júnior, G. Revisiting a Teaching Sequence on the Topic of Electrolysis: a Comparative Study with the Use of Artificial Intelligence. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (8), 3255–3263. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00247.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Morjaria, L.; Burns, L.; Bracken, K.; Levinson, A. J.; Ngo, Q. N.; Lee, M.; Sibbald, M. Examining the Efficacy of Chatgpt in Marking Short-Answer Assessments in an Undergraduate Medical Program. Int. Med. Educ. 2024, 3 (1), 32–43. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime3010004.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Zhang, S. Chatgpt Assisted Teachers in Improving Formative Assessment. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 40, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.54097/qz3kbj17.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Pesovski, I.; Henriques, R.; Trajkovik, V. Generative AI for Customizable Learning Experiences. Sustainability 2024, 16 (7), 3034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16073034.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Tran, T.; Du, Z. Artificial Intelligence in Education: a Systematic Literature Review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124167.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Ratniyom, J.; Panmas, W.; Rattanakorn, P.; Tientongdee, S. Generative AI-Assisted Phenomenon-based Learning: Exploring Factors Influencing Competency in Constructing Scientific Explanations. Eur. J. Educ. Res 2025, 14 (4), 1087–1103. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.14.4.1087.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Zheng, W.; Tse, A. W. C. The Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence-based Formative Feedback on the Mathematical Motivation of Chinese Grade 4 Students: a Case Study. Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Teach. Assess. Learn. Eng. (TALE) 2023, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE56641.2023.10398319.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Lee, S. S.; Moore, R. L. Harnessing Generative AI (Genai) for Automated Feedback in Higher Education: a Systematic Review. Online. Learn. J. 2024, 28 (3), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v28i3.4593.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Liao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Luo, H. Design and Implementation of an Ai‐Enabled Visual Report Tool as Formative Assessment to Promote Learning Achievement and Self‐Regulated Learning: an Experimental Study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55 (3), 1253–1276. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13424.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Lim, L.; Bannert, M.; van der Graaf, J.; Singh, S.; Fan, Y.; Surendrannair, S.; Rakovic, M.; Molenaar, I.; Moore, J.; Gašević, D. Effects of Real-Time Analytics-based Personalized Scaffolds on Students’ Self-Regulated Learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107547.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Afzaal, M.; Zia, A.; Nouri, J.; Fors, U. Informative Feedback and Explainable AI-Based Recommendations to Support Students’ Self-Regulation. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2024, 29 (1), 331–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09650-0.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, L.; Shadiev, R.; Li, Y. Chatgpt’s Capabilities in Providing Feedback on Undergraduate Students’ Argumentation: a Case Study. Think. Skills Creat. 2024, 51, 101440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2023.101440.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Chan, C. K. Y.; Hu, W. Students’ Voices on Generative AI: Perceptions, Benefits, and Challenges in Higher Education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20 (1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-023-00411-8.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; Krusche, S.; Kutyniok, G.; Michaeli, T.; Nerdel, C.; Pfeffer, J.; Poquet, O.; Sailer, M.; Schmidt, A.; Seidel, T.; Stadler, M.; Weller, J.; Kuhn, J.; Kasneci, G. Chatgpt for Good? on Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Usher, M. Generative AI Vs. Instructor Vs. Peer Assessments: a Comparison of Grading and Feedback in Higher Education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2025, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2025.2487495.Suche in Google Scholar

43. Creswell, J. W.; Plano Clark, V. L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2018.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3 (2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Wiliam, D.; Thompson, M. Integrating Assessment with Learning: what Will It Take to Make It Work? In The Future of Assessment: Shaping Teaching and Learning; Dwyer, C. A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, 2008; pp. 53–82.10.4324/9781315086545-3Suche in Google Scholar

46. Williams-McBean, C. T. Contextual Considerations: Revision of the Wiliam and Thompson (2007) Formative Assessment Framework in the Jamaican Context. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26 (9), 2943–2969. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.4800.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Silberberg, M. S.; Amateis, P. G. Chemistry: The Molecular Nature of Matter and Change, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

48. Koo, T. K.; Li, M. Y. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15 (2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Rahimi, S.; khatooni, M. Saturation in Qualitative Research: an Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv 2024, 6, 100174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2024.100174.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Teaching Thematic Analysis: Overcoming Challenges and Developing Strategies for Effective Learning. Psychologist 2013, 26 (2), 120–123. https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/937596 (accessed 02 22, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

51. Chang, C. K.; Chien, L. C. T. Enhancing Academic Performance with Generative AI-Based Quiz Platform. IEEE Int. Conf. Adv. Learn. Technol. (ICALT) 2024, 193–195. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT61570.2024.00062.Suche in Google Scholar

52. Limna, P.; Kraiwanit, T.; Jangjarat, K.; Klayklung, P.; Chocksathaporn, P. The Use of Chatgpt in the Digital Era: Perspectives on Chatbot Implementation. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2023, 6 (1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2023.6.1.32.Suche in Google Scholar

53. Mai, D. T. T.; Da, C. V.; Hanh, N. V. The Use of Chatgpt in Teaching and Learning: a Systematic Review Through SWOT Analysis Approach. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1328769. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1328769.Suche in Google Scholar

54. Monib, W. K.; Qazi, A.; Mahmud, M. M. Exploring Learners’ Experiences and Perceptions of Chatgpt as a Learning Tool in Higher Education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30 (1), 917–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13065-4.Suche in Google Scholar

55. Zimmerman, B. J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: an Overview. Theory Pract 2002, 41 (2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Ng, D. T. K.; Tan, C. W.; Leung, J. K. L. Empowering Student Self-Regulated Learning and Science Education Through Chatgpt: a Pioneering Pilot Study. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2024, 55 (4), 1328–1353. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13454.Suche in Google Scholar

57. Dunlosky, J.; Rawson, K. A.; Marsh, E. J.; Nathan, M. J.; Willingham, D. T. Improving Students’ Learning with Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions from Cognitive and Educational Psychology. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2013, 14 (1), 4–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612453266.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Hooda, M.; Rana, C.; Dahiya, O.; Rizwan, A.; Hossain, M. S. Artificial Intelligence for Assessment and Feedback to Enhance Student Success in Higher Education. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022 (1), 5215722. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5215722.Suche in Google Scholar

59. Wang, W.-S.; Lin, C.-J.; Lee, H.-Y.; Huang, Y.-M.; Wu, T.-T. Enhancing Self-Regulated Learning and Higher-Order Thinking Skills in Virtual Reality: the Impact of ChatGPT-Integrated Feedback Aids. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30 (14), 19419–19445; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-025-13557-x.Suche in Google Scholar

60. Chang, D. H.; Lin, M. P. C.; Hajian, S.; Wang, Q. Q. Educational Design Principles of Using AI Chatbot that Supports Self-Regulated Learning in Education: Goal Setting, Feedback, and Personalization. Sustainability 2023, 15 (17), 12921. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151712921.Suche in Google Scholar

61. Wu, T. T.; Lee, H. Y.; Li, P. H.; Huang, C. N.; Huang, Y. M. Promoting Self-Regulation Progress and Knowledge Construction in Blended Learning via Chatgpt-based Learning Aid. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2023, 61 (8), 1539–1567. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331231191125.Suche in Google Scholar

62. Yin, J.; Goh, T.-T.; Hu, Y. Interactions with Educational Chatbots: the Impact of Induced Emotions and Students’ Learning Motivation. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21 (1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00480-3.Suche in Google Scholar

63. Suárez Vázquez, A.; Suárez Álvarez, L.; del Río Lanza, A. B. Is Comparison the Thief of Joy? Students’ Emotions After Socially Comparing Their Task Grades, Influence on Their Motivation. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21 (2), 100813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100813.Suche in Google Scholar

64. Lu, Y.; Ma, N.; Yan, W.-Y. Social Comparison Feedback in Online Teacher Training and Its Impact on Asynchronous Collaboration. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2024, 21 (1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00486-x.Suche in Google Scholar

65. Dahri, N. A.; Yahaya, N.; Al-Rahmi, W. M.; Vighio, M. S.; Alblehai, F.; Soomro, R. B.; Shutaleva, A. Investigating AI-Based Academic Support Acceptance and Its Impact on Students’ Performance in Malaysian and Pakistani Higher Education Institutions. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29 (14), 18695–18744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12599-x.Suche in Google Scholar

66. Amin, M. A.; Kim, Y. S.; Noh, M. Unveiling the Drivers of Chatgpt Utilization in Higher Education Sectors: the Direct Role of Perceived Knowledge and the Mediating Role of Trust in Chatgpt. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30, 7265–7291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13095-y.Suche in Google Scholar

67. Uppal, K.; Hajian, S. Students’ Perceptions of Chatgpt in Higher Education: a Study of Academic Enhancement, Procrastination, and Ethical Concerns. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2025, 14 (1), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.14.1.199.Suche in Google Scholar

68. Sreedhar, R.; Chang, L.; Gangopadhyaya, A.; Shiels, P. W.; Loza, J.; Chi, E.; Gabel, E.; Park, Y. S.; Comparing Scoring Consistency of Large Language Models with Faculty for Formative Assessments in Medical Education. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2025, 40 (1), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-024-09050-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69. Fernández, A. A.; López-Torres, M.; Fernández, J. J.; Vázquez-García, D. Chatgpt as an Instructor’s Assistant for Generating and Scoring Exams. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (9), 3780–3788. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00231.Suche in Google Scholar

70. Hashem, R.; Ali, N.; El Zein, F.; Fidalgo, P.; Abu Khurma, O. AI to the Rescue: Exploring the Potential of Chatgpt as a Teacher Ally for Workload Relief and Burnout Prevention. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2024, 19, 23. https://doi.org/10.58459/rptel.2024.19023.Suche in Google Scholar

71. Lu, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Longhai, X.; Mingzhu, Y.; Jue, W.; Zhu, X. Can Chatgpt Effectively Complement Teacher Assessment of Undergraduate Students’ Academic Writing? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2024, 49 (5), 616–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2024.2301722.Suche in Google Scholar

72. Alasadi, E. A.; Baiz, C. R. Multimodal Generative Artificial Intelligence Tackles Visual Problems in Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101 (7), 2716–2729. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00138.Suche in Google Scholar

73. Uçar, S.-Ş.; Lopez-Gazpio, I.; Lopez-Gazpio, J. Evaluating and Challenging the Reasoning Capabilities of Generative Artificial Intelligence for Technology-Assisted Chemistry Education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2025, 30 (8), 11463–11482; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13295-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/cti-2025-0048).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.