Esoteric Symbolism in Animated Film Storytelling

-

Fuji Ko

Fuji Ko Fuji Ko (b. 1990) is a PhD student at Nanjing Normal University and is also an English Language instructor at the Yangon University of Education, Myanmar. Her research interests include teaching English to speakers of other languages, cognitive linguistics, and semiotics. Her publications includeWord recognition through word etymology as one of the reading strategies (MA Thesis), “Weaving in Myanmar” (2012) and “How to write a good essay” (2015).

Abstract

Esoteric symbolism of various kinds is dispersed in media for mass communication, and from the semiotic perspective, films, historically the primary medium for motion pictures, are the most powerful weapons for worldwide attraction. In this paper, two famous cartoon animated movies by Disney, Moana and Zootopia, are under analysis. For one thing, they use profound symbols in conveying a message to the audience, especially to children, and for another, their impact on society is wide due to the breadth and diversity of Disney-branded products. Thus, the present paper discusses these two movies using semiotic theories of signs, codes, and symbols, weaving them together to trace the system of communication between the text (here referring to the cinematic texts) and its audience, and especially how a heroine frame is built in the adventure genre. Interpreting the hidden meaning or occult symbolism requires a special kind of knowledge if we aim to convey the essence of the story to our children beyond merely knowing the plot of the film. The films Moana and Zootopia feature a number of interior or hidden elements such as metaphors and allegories, and illuminati or esoteric symbolism, even though they are animated ones.

1 Introduction

Understanding how to interpret events in the environment is crucial to both the physical and mental development of children, as they are young and vulnerable. The initial state of making interpretation of the visual world occurs in childhood, and in that pivotal period, signs act as the conceptual glue that relate a child’s thoughts to the world around it. Once children pick up the signs and make them grow in their daily life, they have the key to open the knowledge bank of the society. Then, the signs become cognitively dominant in their life. In other words, a child can manipulate the signs to represent his or her feelings, thoughts, and behaviors and, vice-versa, the signs can manipulate the child.

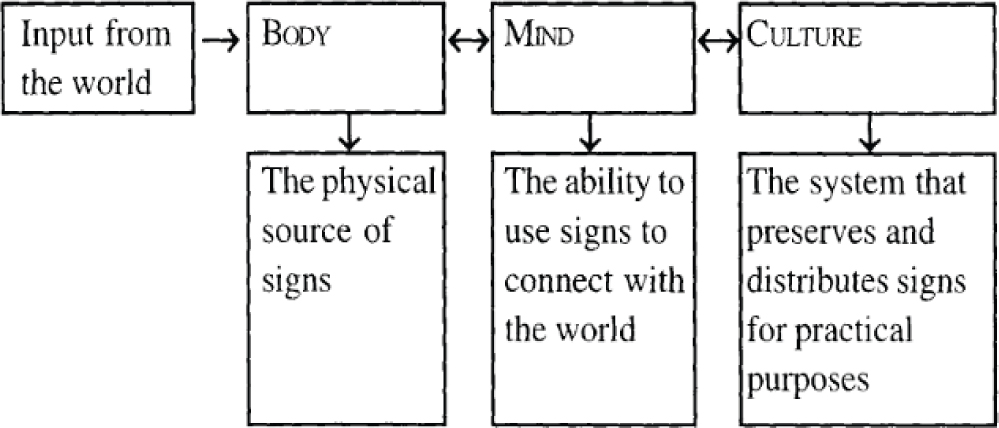

According to the research of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980) and the Russian psychologist L. S. Vygotsky (1896–1934), the nature of the child’s mind is represented by a three-dimensional model of human development. Children develop from a sensory and concrete stage of mind to a reflective and abstract one. When they are around the age of two, they develop representational abilities derived from constant exposure to words and symbols in a cultural context. This is why Vygotsky defined speech as a “microcosm of consciousness” (Vygotsky 1986 : 256).

The interconnection among the body, mind, and culture (Danesi 2004: 18)

1.1 Key semiotic terms used in this paper

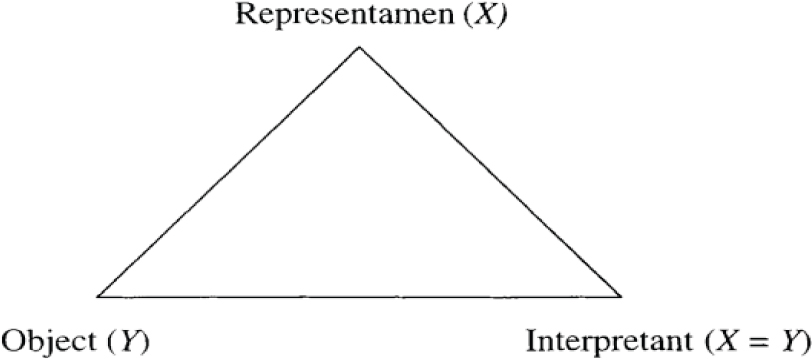

The term “sign” used in this paper reflects the notion of the Peircean sign as follows.

It is the ternary model against the background of the previous binary model of Saussurean sign. The dual relation of the previous model, between the signifier (representamen) and the signified (interpretant), becomes more significant and more complete in the new triadic version, as Peirce differentiates the nature of sign into three distinct levels: icon, index, and symbol. For Pierce, the interpretant (signified) can also be regarded as a sign, and in this way the reproduction of signs occurs again and again in the process of semiosis. As Danesi (2004: 6) said, “a sign can now be defined, more precisely, as something that stands to somebody for something else in some respect or capacity”; a sign is the vehicle in the meaning-conveying process. Of over sixty types of signs by Peirce, the most frequent forms of sign occurring in this article are qualisigns, for the signs in the films are generally based on the attributes of the objects or the referents which the director or the storyteller refers to. If semiotics is the study of communication to understand how meaning is made in a given context, this article tries to approach the meaning-making process to see the link among sign, meaning, and the things being referring to in a systematic way, known as semiotic method by Charles Morris.

The Peircean sign (Danesi 2004: 26)

As quoted in Danesi (2004: 9):

American Semiotician Charles Morris (1901–1979), divided semiotic method into: (1) the study of the relations between a sign and other signs, which he called syntactics; (2) the study of the relations between signs and their basic meanings, which he called semantics; and (3) the study of the relations between signs and their users, which he called pragmatics.

Here in this article, the syntactic and semantic nature of the signs are discussed with respect to the language, the dialogues between the characters, and other audio-visual aids such as the colors, symbols, and the sound track. So, it is far beyond the simple notion of sign with three layers of iconicity, indexicality, and symbolism. The second layer of sign somehow can be seen as code, as it is the systematic, modified system of the primary iconicity with human intervention. Such examples can be seen in well-organized verbal and visual systems like language, dress, music, and gesture. Texts and messages are encoded and decoded again and again with the use of code. When the code is firmly embedded in the society, it can be used as a symbol in that system, as the public recognizes it as a part of culture and it leads to the Thirdness property of the sign.

1.2 Research questions

The main objectives of this cinematic semiotic paper are to study what messages mean in the film, how they have been put together with signs to convey the desired message to the audience, and finally the pragmatic function of discovering the impact of the film from the perspective of the audience through movie critics.

The paper tries to trace the answers to these questions by observing the main characters being themselves in their social ambiances using five specific principles, as proposed by Danesi (2004: 46–47):

identifying the basic sign properties behind the observed behaviors (iconicity, indexicality, etc.);

relating these to the culture in question;

documenting and explaining the effects that bodily codes have on individuals;

investigating how these codes are interconnected throughout the semiosphere;

utilizing the findings or techniques of any cognate discipline (anthropology, psychology, etc.) that are applicable to the situation at hand.

Thus, communication theory, which according to Danesi (2004: 11) is “the study of how messages are put together so that they can be exchanged effectively,” plays a crucial part throughout the paper.

2 A brief synopsis of Moana

The general information on the movie Moana described by Rotten Tomatoes (2018a), an online aggregator of professional TV and film reviews, is as follows.

Rating: PG (for peril, some scary images and brief thematic elements)

Genre: Action & Adventure, Animation, Kids & Family

Directed By: Ron Clements, John Musker, Chris Williams (IX), Don Hall

Written By: Jared Bush

In Theaters: Dec 26, 2016 Limited

On Disc/Streaming: Mar 7, 2017

Box Office: $248,752,120

Runtime: 103 minutes

Studio: Walt Disney Pictures

The film recounts the voyage of Polynesian girl, Moana, daughter of the village chief, who sets sail in the vast Pacific Ocean for the sake of her people in the hope of restoring the legendary heart of the earth to its resting place according to the myth of her grandmother. Along her adventure, she is helped by the demigod Maui, who is at first depicted as a villain for stealing the heart of the earth, Te Fiti, but who finally changes into a heroic figure with great power, free from his self-centered egocentric ways. Along their epic journey of daring mission, the teenage girl finds her own identity, changing into the master wayfinder after many ups and downs. The excellent filmmaking team around Ron Clements and John Musker used different approaches to successfully set the model of a heroine for the main character, Moana, and that of a hero for the other protagonist, Maui. Based on modeling systems theory and semiotic analysis by Thomas A. Sebeok and Marcel Danesi, this paper traces how the model of hero for the two main characters is weaved throughout the story.

2.1 Model of the heroine, Moana

Moana, literally meaning ‘the ocean’ in Polynesian language, is the main character, and the heroine conquers her namesake. So, the name of the main character itself becomes the meta-symbol of the tertiary modeling system, as it is the symbol and metaphor in connective form for linking the main character and the ocean. Throughout the story, Moana insists that the ocean chose her for the impossible mission of restoring the heart. But she is the ocean herself and it is not the ocean who chose her, but she herself who chose to take the responsibility of that grave duty for the sake of her people. This can be seen in her dialogue with Maui, the other protagonist, in the story.

Moana: My people…didn’t send me, the ocean did!

Maui: Makes sense… you’re what? Eight? And can’t sail

Moana: It chose me for a reason.

Moana: “I have no idea why the ocean chose me. You’re right. But my island is dying and it’s just me and you.” (Cited in Frankel 2016)

So, the name of the main character, Moana, beyond the horizon of the denotation realm, passing the connotative meaning of voyager, finally becomes the meta-symbol of self through the crystallization process of her destiny as the voyager.

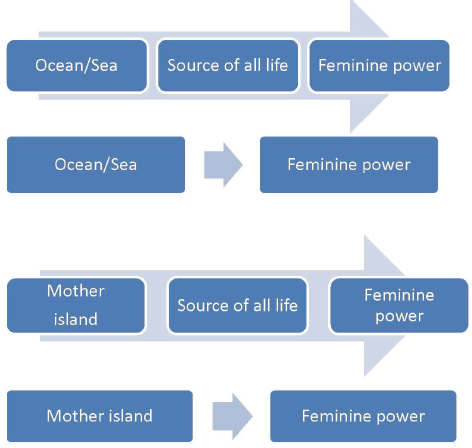

At the beginning of the story, according to the narrator, there was only one ocean until the mother island, Te Fiti, emerged. We can see the sea and the island are used for feminine power and thus become the metaphors of the primary modeling system. The sea is the source of all life and thus has feminine power, and so is the use of motherland for Te Fiti (see Figure 3).

Examples of metaphors used in the film Moana for the primary modeling system (based on Frankel 2016)

Thus, all these things support the feminist heroine theme of the story.

The heart of Te Fiti is an ancient greenstone amulet bearing a spiral carving, which is said to have brought about creation. Its loss leads to environmental destruction, and Moana’s quest is to return the stone and save the world. According to Valerie Frankel (2016) in her discussion of feminine symbolism, the green of the stone represents “immaturity and growth, the fertility and health of the land.” The figure of a spiral over the stone represents the death and the rebirth of the earth (see Walker 1988: 14). Thus, the heart of Te Fiti becomes a distinct symbol, like yin and yang, and the representation of the tertiary non-verbal singularized model, in the story.

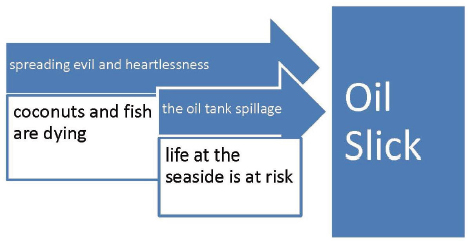

For the eco-conscious aspect of the story, we can see the meta-meta forms of the secondary modeling system as illustrated in Figure 4.

Meta-meta forms of the secondary modeling system in Moana as an eco-conscious story (based Frankel 2016)

The scenes of dying fish and coconuts rotting in the film due to the evil spirit reminds us of oil spills in the real world, which are highlighted in the news with pictures, warning that life at the seaside is at risk. Thus, this metaphorically indicates the issue of our real-world environment being under threat.

As for the narrative structure of the story, the real standout is the music. The lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda succeed in conveying the theme of the entire movie with ultimate optimism. Some parts of the narrative can be streamlined, as the theme songs are to some extent explanatory statements, driving the plot forward.

Altogether the three main songs for the Moana character are in some way verbal composite models of the tertiary modeling system. In the first one, “Where you are,” the lyrics “You must find the happiness where you are,” “The island gives what we need,” and “No one goes beyond the reef” (AZLyrics 2018d) convey the message of hope that Moana’s father has for the safety of his daughter, but they have a reverse effect on Moana. The more he tries to convince his daughter that “there is nothing beyond the reef,” the more intensely the desire is formed in Moana with the idea that “there will be more beyond the reef!” Here, the reef has the connotative meaning of the boundary. Sometimes the protective boundary becomes the hindrance to progress in life.

The second song, “How far I’ll go,” is discussed with the help of Table 1.

Worldwide different versions of “How far I’ll go” (Source: en.wikipedia.org 2018)

| Language | Performer | Title | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch | Vajèn van den Bosch (nl)[32] | “Ooit zal ik gaan” | “Sometime I’ll go” |

|

|

|||

| English | Alessia Cara | “How Far I’ll Go” | |

|

|

|||

| Flemish | Laura Tesoro[33] | “Ooit zal ik gaan” | “Sometime I’ll go” |

|

|

|||

| French | Cerise Calixte[34] | “Le bleu lumière” | “The gleam-blue” |

|

|

|||

| German | Helene Fischer[35] | “Ich bin bereit” | “I am ready” |

|

|

|||

| Japanese | 加藤ミリヤ (Miliyah Kato)[36] | “どこまでも”(“Dokomade mo”) | “To the ends of the earth” |

|

|

|||

| Kazakh | Гулсим Мырзабекова (Gulsim Myrzabekova)[37] | “Бірақ қайда барам” (“Biraq qayda daram”) | “Where do I go” |

|

|

|||

| Mandarin Chinese (China) | 吉克隽逸(“Jike Junyì”; Summer Jike) (zh)[38][39] | “海洋之心” (“Hǎiyáng zhī xīn”) | “The heart of the sea” |

|

|

|||

| Mandarin Chinese (Taiwan) | 阿玲(“Ā Líng”; A-Lin)[40][41] | ||

|

|

|||

| Māori | Maisey Rika[42] | “Tukuna Au” | “I was released” |

|

|

|||

| Polish | Natalia Nykiel[43] | “Pół kroku stąd” | “Half a step away” |

|

|

|||

| Russian | Юлианна Караулова (Yulianna araulova)[44] | “Cepдцe Moё” (“Syerdtse oyo”) | “My heart” |

The above song, “How far I’ll go,” the theme song of the whole movie, is full of metaphors in lines such as “What’s beyond that line, will I cross that line? […] maybe I can roll with mine […] I’ll be satisfied if I play along but the voice inside sings a different song,” “the call is not outside that’s inside you” (Metrolyrics 2018). The word “line” refers to Moana’s fear, and the other words “voice,” “song,” and “call” refer to Moana’s passion, her hope. There are forty-four versions in different languages and even the translation of the song title across languages shows us the primary modeling system of denotative meaning along with the tertiary modeling system with social code (see Table 1).

The third song, “We know the way,” reflects the social code of the tertiary cohesive modeling system, showing the history and culture of her ancestors in the lyrics of “Keep our island in our mind […] we are voyagers” (AZLyrics 2018c).

In fact, stories are codes in the secondary modeling system, and they are the composite models of human ideas, emotions, and social and ethical behaviors. In the dialogue between Moana and Sina, Moana’s mother, Sina says “He’s hard on you…because he was you.” This is the meta-meta form in the secondary modeling system, linking the terms he (Moana’s father) and you (Moana) as the same person. In the same dialogue, Sina continues: “Waves like mountains.” This is also a metaphor in the primary modeling system. Throughout the story, maps on the wall of the ancient cave where her ancestors lived and Maui’s tattoos are used in the secondary composite modeling system.

2.2 Model of the hero, Maui

Maui, another chief character, who is “a demigod, steals the cornerstone of all creation, the heart of Te Fiti, resulting in the slow destruction of the ancient Polynesian islands” (Bhave 2016). The most obvious feature of Maui is his tattoos, which represent the secondary composite model depicting the inner voice of Maui. Maui is the symbol of a male character and his character is more human, for he has his own flaws like having a fear of swimming and a quest for love although he possesses supernatural power. The “You are Welcome” song by Maui reveals how proud he is and what his ego is like. Thus, the lyrics, which are in a spoken form, narrate what kind of person Maui is, and in semiotic terms, that text conveying Maui’s character becomes a secondary verbal composite model.

Maui is a witty character who formulates amusing metaphors. He calls Heihei, a friend of Moana’s, a drumstick and a boat snack, and Moana a chicken because she is friends with a chicken. He mocks social media in the lines “When you use a bird to write with, it’s called tweeting.” This text is referred to as abduction in semiotics, the process of best guess inferencing.

Dialogues between Moana and Maui progressively depict the main theme of the story, “The power is not outside but it’s inside you” is stated with respect to changing Maui’s character in the lines below:

Maui: No magic hook… no magic powers…without my hook, I am nothing…

Moana: The gods aren’t the ones who make you Maui, you are.

Maui: Hook or no hook, I am Maui. (Moana 2016)

In these lines, the hook represents power for Maui. So it is a metaphor. The author conveys the intended message through Maui in these lines when Maui teaches Moana sailing:

Maui: The Ocean can’t save you, you have to save yourself.

Maui: It’s called wayfinding, Princess. It’s seeing where you are going in your mind, knowing where you are by knowing where you have been. […] [A] real wayfinder never sleeps. (IMDb 2018)

His greatest achievement in the movie is his brave feat of defeating the lava god at the risk of losing his magic hook and, remarkably, he can change the main character, Moana. Throughout the whole story, Moana asks Maui to come with her, to go to Te Fiti and to restore the heart. But finally she changes her mind, singing different a verse before the climax, that “I am Moana of Motusi. Aboard my boat, I will restore the heart to Te Fiti.” Now she is standing completely on her own feet and this is partly due to Maui.

2.3 Conclusion

Interestingly, the twist of the story is that the lava god, the villain, is also Te Fiti, the earth. She changed into the evil one after losing her heart. This is revealed in the last scene, in Moana’s dialogue with Te Fiti.

Moana: They have stolen the heart from inside you. This is not who you are. You know who you are. (AZLyrics 2018b)

Her heart is restored, and the goddess turns green and loving once again. We can see the colors as representing the positive and negative attributes, and they serve as non-verbal semiotic symbols of the tertiary modeling system.

Leadership attributes are found throughout the story. Regarding Maui, he first misunderstands, thinking that his success will come from stealing the heart, but this causes disaster. So, the message is that sometimes what we think is success is not actually so. Facing the ups and downs in the journey, one common thing found is that fear can hold someone back. The golden key of the movie in terms of the heroic model for the two main characters is, in my view, listening to your inner voice and following your dream. The power is inside you.

3 A brief synopsis of Zootopia

The basic information about Zootopia as recorded by Rotten Tomatoes (2018) is as follows:

Original release date: March 4, 2016

Rating: PG

Genre: Adventure

Director: Byron Howard, Rich Moore

Running time: 108 mins

Budget: $150,000,000

Zootopia, the 55th animated film by The Walt Disney Company, is full of esoteric symbols and supernatural characters. This neo-noir film blended with humor stars a rabbit with charisma, Judy, and an anthropomorphic tricky fox, Nick. From the biggest elephant to the tiniest shrew, the city of Zootopia is a beautiful conurbation of various metropolitan areas for different groups of animals. The city dwellers are intelligent animals with anthropomorphic forms living peacefully with one another. Determined to prove her worth, Judy Hopps becomes the first official bunny cop on the police force. When 14 predator animals go missing, Judy tries to solve the case despite the limitation of time to crack it within 48 hours. Partnering with a con artist fox named Nick Wilde, they successfully uncover the conspiracy. The following section 3.1 is a discussion from a semiotic perspective of the ideas proposed in the article, “Zootopia symbolism” (2016) by Jay Pilon.

3.1 Zootopia, utopia for animals

The title of the movie is the name of the town, with the term itself serving as the symbol of the tertiary modeling system. The name is coined by blending the two terms “zoo” and “utopia,” making the audience aware of the fact that the city dwellers are not human beings, but animals in a particular civilized society, where predators and prey live harmoniously. The term utopia reflects the idea that it is a unique, near-perfect place to live in. This fact is highlighted throughout the story in the conversation of different characters, in statements like “Anyone can be anything in Zootopia.” According to Pilon (2016), Zootopia city is the figurative new Babylon, a new civilization, where the animals seem to live in harmony. It has five city districts, namely Sahara Square, Tundratown, Little Rodentia, Rainforest District, and the City – the heart of Zootopia under the support of the farming community Bunnyburrow. So, altogether Zootopia is composed of six districts. Throughout the film, six is a popular, recurring number, seen in different parts of the story. The symbolism of the number six partly derives from the Judeo-Christian tradition, where it refers to the selfishness of humans (Ezekiel 7: 25). According to the Pilon’s Gematria analysis, the scattering of the number six can be found in the train number of the regional Zootopia rail, in describing the age of the protagonist, the fox which is 32 (3x2=6), the license plate number of the suspect, 29THD03 (29+03=32, 3x2=6), the city camera number 12 which guides the missing predictor (6+6=12), and the news time of Zootopia Channel (6:01).

The influence of the no. six throughout the movie Zootopia (Pilon 2016)[1]

Another symbolic representation concerns the figures of the lemmings. They wear business suits and work a 9-to-5 day. Based on these observations, Pilon states that the lemmings represent the banking elite of Wall Street.

Another interesting public figure in Zootopia is Gazelle, acted by the singer Shakira. She is the famous entertainer of the megapolis, welcoming each and every animal who comes to Zootopia. As her character only has “one eye,” this can be seen as the udjat, the eye of Ra, thus suggesting that she has the power of Ra (Pilon 2016). Her figure as an anthropomorphic heroine goat dressed in red is frequently addressed as “The Angel With Horns” in the film.

Hopps and Wilde later find an asylum where the missing, now savage mammals have been imprisoned. Once they make public the place of asylum, the two become heroes. But this is not the end of the story. There is something missing in the story: the final question of why these civilized mammals became savage ones, i.e. returned to their primal state. The pair finally gets the answer to that question as they come to know that this is because of a drug made from flowers called “Night Howlers.” There is a secret group behind the plot.

The representation of lemmings as the banking elite in the movie Zootopia (Pilon 2016)

The representation of Gazelle as a goat, played by Shakira (Pilon 2016)

Assistant Mayor Bellwether and the greedy sheep manipulate the drug for their power. The supporters of this secret grouping, the gang of sheep, wear shirts with the symbol of Pan Baphomet. This is an allegory for the secretive nature of Mystery School thinking. This is illustrated in Figures 8 and 9.

The gang of conspirators wearing shirts with the secret sign (Pilon 2016)

The sign of the secret gang (Pilon 2016)

The last symbolic figure used in the story is the “Night Howlers.” They are small blue flowers which are able cause the consumers to lose their minds. This kind of flower can be seen in the movies A Scanner Darkly, Zoolander, and WorldWar Z. The following figure, Figure 10, contrasts Night Howlers in Zootopia with those in another film, A Scanner Darkly.

“Night Howlers” in Zootopia and A Scanner Darkly (Pilon 2016)

3.2 The main character, Judy Hopps, as the heroine frame

Judy Hopps, a rabbit police officer, with the help of Nick Wilde, a red fox who is a street hustler, eventually uncovers a conspiracy involving missing predator civilians and psychotropic drugs. The blue rabbit is the representation of a solder in Christ, like the main character in the film Captain America. Thus, the choice of the color blue as the dress code of the main character is a kind of esoteric trope hiding in plain sight in that plot. Later, the heroine figure of the rabbit is highlighted in her actions and dialogues with other characters in the story. Her mighty attempts to save her friends’ free tickets from the fox tell us that she is unique and brave. She tries against all odds to pursue her dream, even though her parents tell her that there has never been a rabbit police officer in Zootopia. But Judy believes in the Zootopian dream of “Anyone can become anything in Zootopia” and becomes the first rabbit police officer.

Despite her first officer life as a meter maid, Judy tries to help others as much as she can, and this leads to her meeting the male character Nick. We witness her upright nature when she tells Nick that she can’t stand it when people are mistreated for being predators or prey, and walks away with a spring in her step. She is happy to have helped someone in need.

In the spy case of the story, Judy’s wit and bravery can be seen when she manages to control the sly fox and in the adventure of facing the slug boss and Assistant Mayor Bellwether. These lines show Judy’s wit and struggle.

Judy Hopps: Tomorrow’s another day.

Young Hopps: [Referring to Gideon Grey, with determination] Well, he was right about one thing. I don’t know when to quit!

Judy Hopps: With all due respect, sir, a good cop […] is supposed to serve and protect, help the city, not tear it apart. (IMDb 2018b)

Despite her outstanding achievements and courageous acts, she also cannot escape from the stereotype. This fact can be seen in the following lines:

Judy Hopps: Only a bunny can call another bunny “cute.”

Judy Hopps: If there’s one thing we bunnies are good at, it’s multiplying.”

Judy Hopps: Wait. They’re all SLOTHS? You said this was going to be quick!

Nick Wilde: [in mock surprise] Are you saying that because he’s a sloth he can’t be fast? I thought in Zootopia, anyone could be anything. (IMDb 2018b)

To err is human and because of the strict norms of stereotypes she lives in, Judy makes a mistake in her first speech to the public after finding the missing animals.

Judy starts her speech simply, stating that all the savage mammals struck by the affliction are predators, but when the press ask why, she speculates that it could be something to do with their DNA. As predators, the inflicted may have reverted back to their primal origins. Moreover, although she believes herself to be unprejudiced, she carries fox repellent with her all through the story, revealing that foxes are to her mind cunning creatures to be wary of, but at the end of the story she confesses her misunderstanding, seeing the truth and providing the conclusion for the story. Awakening from a stereotypic culture is not a task that can be accomplished overnight, as we are used to the customs and norms of society, and thus this will be a long battle to fight. This fact is shown in Judy’s second speech as follows:

When I was a kid, I thought Zootopia was this perfect place where everyone got along and anyone could be anything. Turns out, real life’s a little bit more complicated than a slogan on a bumper sticker. Real life is messy. We all have limitations. We all make mistakes, which means…hey, glass half full! We all have a lot in common. And the more we try to understand one another, the more exceptional each of us will be. But we have to try. No matter what type of animal you are, from the biggest elephant to our first fox, I implore you: Try. Try to make a difference. Try to make the world better. Try to look inside yourself and recognize that change starts with you. It starts with me. It starts with all of us. (IMDb 2018b)

3.3 The main character Fox

As the blue rabbit’s partner, Nick Wilde, a red fox and street hustler, gingers up the detective plot in an amusing way. The choice of red for the fox is particularly suitable from a religious perspective as well. In occult terms, red has a connection with the period of “Jacob’s Trouble,” the time when the church will be persecuted (see Jeremiah 30: 7), which also has parallels with legends of the North American Hopi people.

Nick, unlike Judy, is practical and witty, and in conversation, we can see his attitude that the city is not a magical land where dreams come true and a meter maid can never be a real cop.

Nick Wilde: Everyone comes to Zootopia thinking they could be anything they want. But you can’t. You can only be what you are. Sly fox. Dumb bunny. (IMDb 2018b)

He gives his friend a lot of names, which are metaphors of the secondary modeling system, meta-metaphors, because they are somehow connected with the quality or the situation of the context. This can be seen in the following lines.

Nick Wilde: Hey, it’s Officer Toot-toot!

Nick Wilde: What happened, meter lady?

Nick Wilde: Hey, Carrots, you’re gonna wake the baby. I gotta get to work.

Nick Wilde: It’s called a hustle, sweetheart. (IMDb 2018b)

Moreover, he is also smart. Every time the main character gets lost, he finds the way for her. The following lines show that fact.

Nick Wilde: I think you said plenty.

Judy Hopps: What do you mean?

Nick Wilde: [saddened] Clearly there’s a biological component? That these predators may be reverting back to their primitive savage ways? Are you serious?

Judy Hopps: I just stated the facts of the case! I mean, it’s not like a bunny can go savage.

Nick Wilde: Right. But a fox could, huh?

Judy Hopps: Nick stop it! You’re not like them.

Nick Wilde: [getting angered] Oh, so there’s a them now?

Judy Hopps: You know what I mean! You’re not that kind of predator.

Nick Wilde: The kind that needs to be muzzled? The kind that makes you believe that you need to carry around fox repellent? Yeah, don’t think I didn’t notice that little item on the first time we met. So let me ask you a question: Are you afraid of me? You think I might I might go savage? You think that I might try to…

Nick Wilde: Whatever you do, do not let go! (IMDb, 2018b)

In fact, he too is the victim of stereotype and has lost his dream. We can see his pain in these lines:

Young Nick: [Undergoing Junior Ranger Scout initiation by flashlight] I – Nicholas Wilde – promise to be brave, loyal, helpful, and trustworthy!

Junior Ranger Scout 1: Even though… you’re a fox? (IMDb 2018b)

3.4 The other animals in Zootopia

In the beginning of the story, young Judy Hopps is attacked by a red fox called Gideon Grey, who mocks her dream of being a cop, claiming it is a job only for big herbivores and carnivores, but later the fox regrets his misdeeds and apologizes to Judy. The interesting thing to note here is the choice of the name of the character in the story. The name Gideon coincides with the biblical name Gideon from the Torah’s “Book of Judges” to emphasize the power of forgiveness and repentance.

We can see the link between the animals and their names in the story. The mayor lion is Lionheart, the chief officer Bogo is a buffalo, the missing animal otter’s name is Emmitt Otterton, and the yak’s name is Yax. However, the reversed relation can be found in the animal and its job in that DMV is managed by a sloth and the thug boss, Mr. Big, is just a shrew. The pudgy desk sergeant, a cheetah named Benjamin Clawhauser, demonstrates that the symbol of stereotyping is not always correct. Despite being a cheetah, he is funny, cute, and only interested in playing games and eating donuts. Except for Judy, all the other officers are elephants, rhinos, hippos, and bears, and this illustrates the fact that there is somehow discrimination.

The following are the extracts of dialogue which reflect stereotypy.

Gideon Grey: Nice costume, loser! What crazy world are you living in where you think a bunny could be a cop?

Chief Bogo: Life isn’t some cartoon musical where you sing a little song and all your insipid dreams magically come true. So let it go.

Chief Bogo: [from trailer] It’s not about how badly you WANT something. It’s about what you are capable of!

Mr. Big: We may be evolved, but deep down we are still animals.

Nick Wilde: That if the world’s only going to see a fox as shifty and untrustworthy, there’s no point in being anything else.

Bellwether: Fear always works, and I’ll dart every predator in Zootopia to keep it that way. (IMDb 2018b)

3.5 Conclusion

Beyond the scope of fantasy films aimed at children, Zootopia conveys a special message to the audience based on the plot of the fantasy city where both predators and prey live together in harmony. It emphasizes the fact that discrimination is wrong, but stereotypes are stereotypes for a reason, and it’s not easy for members of a despised class to overcome it, so we need to be patient.

According to Seitz (2016), Zootopia is constantly asking its characters to look past species stereotypes. Thinking it in an alternative way, Zootopia resembles the actual outer world around us. We can see the fact that members of certain social classes who have power in society in respective sectors (police, businesspeople, city bureaucrats) are like “predators” and those who lack this kind of power due to different circumstances or their professions turn into “prey.” In this sense, Zootopia can rubber-stamp whatever worldview parents want to pass on to their children. All in all, it invites children and parents to talk about nature versus nurture, and the origins and debilitating effect of stereotypes.

4 Findings and discussion

Danesi (2004: 21) remarks, “Codes guide interpretation in a context. In semiotics, the term context is defined as the environment, situation, or process – physical, psychological, and social – in which interpretation unfolds.” Codes are crucial as they are signals that enable us to study a particular culture, the conceptual dynamic framework of closely related systems formed by the collection of contexts. For Danesi, codes are the “organizational grids” in the cultural framework.

The complementary nature of human beings and the cultural system can be seen in the terms introduced by Giambattista Vico, as described by Danesi (2004: 42).

The Neapolitan philosopher Giambattista Vico (1688 –1744) termed these the fantasia and the ingegno. The former is the capacity that allows human beings to imagine literally anything they desire freely and independently of biological or cultural processes; it is the creative force behind new thoughts, new ideas, new art, new science, and so on. The latter is the capacity to convert new thoughts and ideas into representational structures – metaphors, stories, works of art, scientific theories, etc. So, although human beings are indeed shaped by the cultural system in which they are reared, they are also endowed with creative faculties that allow them to change that very system.

Thus, we can say that semiotic codes, including language, metaphors, and symbols, are mental codes and they are also the weapon in nurturing the children to become thoughtful individuals, which is necessary to do for the next generation to become a more civilized society with innovated and renovated power.

Children are young in body, mind, and personality, which undergo constant growth day by day. Stories provide comprehensible input for the children to make sense of the real world around them. With the help of stories, children can see the events around them have a plot. They can compare the people around them to the characters in the story and guess the consequences of their actions. They can see that the feelings and thoughts of the people are bound to the background knowledge they have, based on the places they live in, and in this way, setting plays the crucial role in human life. Thus, stories can shape the children to become mature persons in their adult stage, as stories can sow the seed of observation in their mind.

Another advantage of the stories is that they have illustrations and they can strengthen metaphorical reasoning, a kind of semiotic strategy for building concrete knowledge from abstract entities.

According to Algirdas Julien Greimas (1917–1992), a semiotician and powerful influencer in the study of narrative, the stories of different cultures have the basic structure of narrative. According to him, the constituents of the stories called actants, such as characters, motifs, themes, settings, etc. have a similar nature across diverse cultures. Danesi (2004: 144) describes the basic structure of narrative by Greimas as follows.

A subject (the hero of the plot) who desires

an object (a sought-after-person, a magic sword, etc.)

and who encounters

an opponent (a villain, a false hero, a trial situation, etc.)

and then finds

a helper (a donor) who then gets an object from

a sender (a dispatcher) and gives it to

a receiver and the action unfolds accordingly until a

resolution manifests or does not manifest itself, leading to

different kinds of endings

This kind of plot structure can be found in both Moana (myth: the story of ancient gods and the origins of the universe) and Zootopia (mythology: mythical thinking in a modern context). Moana can be classified as a cosmogenic myth with anthropomorphic gods, as the plot explains how the earth came to exist. Zootopia is a detective story mixed with modern-day rational-scientific thinking. Myths and mythology are valuable for children for imparting metaphysical knowledge of the values and morals of the society. In other words, they are the starting points of different cultures in different societies. Myths can be compared across cultures to see the similarities and differences among them and to understand people’s behaviors in different societies.

The following table shows the character analysis of the two stories Moana and Zootopia by using the basic structure of narratives by Greimas.

The basic elements of narratives in Moana and Zootopia

| Elements of the narratives | Moana | Zootopia |

|---|---|---|

| A subject (the hero of the plot) | Moana | Judy Hopps |

| An object (a sought-after-person, a magic sword, etc.) | The heart of Te Fiti (earth) | Discrimination (stereotypes) |

| An opponent (a villain, a false hero, a trial situation, etc.) | Lava God | Assistant Mayor ( Ms. Bellwether) |

| A helper (a donor) | Maui (demigod) | Nick Wilde ( Red Fox) |

| A sender (a dispatcher) | The Ocean | ? [Nick Wilde ( Red Fox)] |

| A receiver | Te Fiti (the earth) | Zootopia ( the land of animals with no discrimination) |

Danesi (2004: 141) writes, “The penchant for stories is an undeniable fact for human beings as people all over the world cannot help but think even of their own lives as stories and proceed to describe them as such […] storytelling is as fundamental to human psychic life as breathing is to physical life.” Storytelling is an art. It is not simply recounting the events, but gets the audience to interpret them holistically as a sign, a code, or a symbol. In a semiotic sense, if X is the narrative text containing a plot, “macro-referent,” then the interpretation of X can be called Y, subtext, the meaning extracted from the main text.

The plot is the systematic weaving of different signs with each character such as for a personality type – the hero, the coward, the lover, the friend, and so on. In addition to that, the readers cannot neglect the setting, the location where the story happens, and the time when the story takes place. In understanding the background of the story, the readers can grasp the general idea of the context, and this leads to the understanding of the culture of the given society. Communication, in semiotic terms, becomes a complex process of identifying, as it comprises a variety of elements. A complete comprehension process as only one fragment in the communication system can happen only when the semiosis circle (the understanding of a piece of information) spins around at least once between the two interlocutors in the context. This can be seen in the following diagram in Figure 11.

Semiosis circle

About the author

Fuji Ko Fuji Ko (b. 1990) is a PhD student at Nanjing Normal University and is also an English Language instructor at the Yangon University of Education, Myanmar. Her research interests include teaching English to speakers of other languages, cognitive linguistics, and semiotics. Her publications include Word recognition through word etymology as one of the reading strategies (MA Thesis), “Weaving in Myanmar” (2012) and “How to write a good essay” (2015).

References

AZLyrics. 2018a. Dwayne Johnson lyrics: You’re welcome. https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/dwaynejohnson/yourewelcome.html (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

AZLyrics. 2018b. Moana cast lyrics: Know who you are. https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/moanacast/knowwhoyouare.html (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

AZLyrics. 2018c. Moana cast lyrics: We know the way. https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/moanacast/weknowtheway.html (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

AZLyrics. 2018d. Moana cast lyrics: Where you are. https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/moanacast/whereyouare.html (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Bhave, Nihit. 2016. Movie reviews: Moana movie review. The Times of India December 1. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/english/movie-reviews/moana/movie-review/55723134.cms (assessed 6 June 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Chandler, Daniel. 2007 [2002]. Semiotics: The basics. 2nd edn. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203014936Suche in Google Scholar

Danesi, Marcel. 2006 [2004]. Messages, signs, and meanings. 3rd edn. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Eco, Umberto. 1976. A theory of semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University.10.1007/978-1-349-15849-2Suche in Google Scholar

Frankel, Valerie Estelle. 2016. Pop culture: Moana and Feminine Symbolism. Valerie Estelle Frankel’s pop culture blog December 3. https://valeriefrankel.wordpress.com/2016/12/03/moana-and-feminine-symbolism/ (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

IMDb. 2018a. Moana (2016). http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3521164/plotsummary (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

IMDb. 2018b. Zootopia (2016) quotes. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2948356/quotes (accessed 16 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

IMDb. 2018c. Zootopia (2016). http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2948356/plotsummary?ref_=tt_stry_pl (accessed 15 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Lotman, Jurij & Mark E. Suino (trans.). 1981 [1976]. Semiotics of cinema. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.Suche in Google Scholar

Moana. 2016. Ron Clements, John Musker, Don Hall & Chris Williams (Directors). USA: Walt Disney Animation Studios & Walt Disney Pictures.Suche in Google Scholar

Metrolyrics. 2018. Auli’i Cravalho – How Far I’ll Go Lyrics. http://www.metrolyrics.com/how-far-ill-go-lyrics-aulii-cravalho.html (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Pilon, Jay. 2016. Zootopia symbolism – Gematria study & illuminati symbolism. Gematriacodes March 5. https://gematria.codes/tag/zootopia-symbolism/ (accessed 15 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Rotten Tomatoes. 2018a. Moana. https://www.rottentomatoes.com/rn/moana_2016/ (accessed 6 June 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Rotten Tomatoes. 2018b. Zootopia – 2106. https://www.rottentomatoes.com/rn/zootopia/ (accessed 15 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Sebeok, Thomas A. and Marcel Danesi. 2000. The forms of meaning: Modeling systems theory and semiotic analysis. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110816143Suche in Google Scholar

Seitz, Matt Z. 2016. Zootopia reviews. Roger Ebert’s Journal March 4. https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/zootopia-2016/ (accessed 7 January 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

The Walt Disney Company. 2018. About The Walt Disney Company. https://thewaltdisneycompany.com/about/ (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Vygotsky, Lev. 1986. Thought and language. Alex Kozulin (ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Walker, Barbara G. 1988. The woman’s dictionary of symbols and sacred objects. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.Suche in Google Scholar

Wikipedia. 2018. How Far I’ll Go. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/How_Far_I%27ll_Go (accessed 14 February 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Wilkinson, Alissa. 2016. Disney’s Moana tells an emotional, funny story worthy of its luminous heroine. Vox November 24. https://www.vox.com/culture/2016/11/22/13713820/moana-review-disney-dwayne-johnson-lin-manuel-miranda/ (accessed 9 January 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2018 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Cultural Signs and Sign Theories

- Reclassification of Signs

- Semiotic Processing in Working Memory

- Example, Metaphor, and Parallelism in the Object

- “Is it useful to talk to other cancer patients?”

- Narrating Near-Death Experience

- Esoteric Symbolism in Animated Film Storytelling

- Perceiving Humor in Traditional Chinese Peking Opera

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Cultural Signs and Sign Theories

- Reclassification of Signs

- Semiotic Processing in Working Memory

- Example, Metaphor, and Parallelism in the Object

- “Is it useful to talk to other cancer patients?”

- Narrating Near-Death Experience

- Esoteric Symbolism in Animated Film Storytelling

- Perceiving Humor in Traditional Chinese Peking Opera