Abstract

As pivotal elements of academic communication, journal paper titles exhibit distinct disciplinary characteristics that remain under-explored. The present study conducts a systematic comparison between natural sciences and humanities titles through quantitative and qualitative analysis of 1,000 internationally published journal paper titles (500 per discipline). The study finds that titles in natural sciences are, on average, longer. Structurally, natural science journals feature a higher prevalence of noun phrases and full sentences, whereas humanities journals more commonly employ compound phrases. Regarding high-frequency words, prepositions are more likely to appear in titles of natural sciences, while humanities scholars tend to use and to create a juxtaposition to explore the relationships between research contents. For parts of speech, the quantities of verbs and adjectives in natural science titles are substantially greater than those in humanities. Additionally, humanities titles feature more proper nouns, while natural science titles lean towards common nouns as modifiers. These differences demonstrate that scholars from different disciplines adhere to specific norms and conventions that are widely accepted within their respective community of practice. This research enriches our understanding of the disciplinary differences in title construction, and offers practical guidance for academic scholars and enables them to better navigate discipline-specific publication norms.

1 Introduction

In the era of globalization, the landscape of academic communication has undergone a profound transformation. International academic exchanges have broken through national boundaries, and interdisciplinary collaboration is on the rise. In this context, renowned international journal papers stand out as a crucial platform for researchers worldwide to share their findings. English, as the academic lingua franca, dominates research article (RA) publishing in most international journals (Hyland 2016; Lillis and Curry 2010). This poses a significant challenge to non-native English speakers, who are now required to write RAs in a language that is not their mother tongue, making it essential for them to master the nuances of English academic writing (Canagarajah 2020; Flowerdew 2019; Menezes and Monteiro 2022). Amidst these changes, the study of RA titles, especially the differences between natural sciences and humanities, has become crucial. Titles are the first point of contact for readers and play a crucial role in academic communication (Swales 1990; cf. Bhatia 1993), therefore they deserve careful attention by the authors (Singh, Chaudhary, and Suvirya 2009). Considering the interdisciplinary nature of modern research where these two fields often intersect, understanding these title differences is essential for effective cross-disciplinary communication.

Research on RA titles is a relatively nascent field, with its origin dating back to the end of the last century. As Swales (1990) pointed out, the study of RA titles was an under explored area of scholarship at that time. Although subsequent research has identified multiple factors influencing title writing, such as editorial policies, individual researchers’ stylistic preferences, generic variables, and disciplinary variables (Soler 2011), the core literature in this area remains under emphasized. Among these influencing factors, disciplinary differences have attracted a great deal of attention from scholars.

Disciplines are not only fields of study but also distinct language-using communities with their own conventions. Biglan (1973) categorized the academic community into four disciplinary groups: the natural sciences (hard-pure), the humanities and social sciences (soft-pure), the science-based professions (hard-applied), and the social professions (soft-applied). Each group has its unique epistemological norms and language use patterns. When authors write for publication, they must conform to the social rules and disciplinary conventions of their respective fields. However, despite the growing interest in disciplinary variables, in-depth research specifically focusing on the differences between hard-pure and soft-pure sciences in terms of RA titles is still lacking.

This study is designed to fill this research gap. We aim to conduct a comprehensive comparative analysis of the titles of papers published in international journals across the natural sciences and humanities. To achieve this, we have constructed a self-built corpus consisting of 1,000 titles selected from six disciplines: chemistry, physics, and biology representing the natural sciences, and literature, philosophy, and history from the humanities. Through a detailed examination of structural features and lexical choices of titles, we seek to uncover the differences and similarities between these two broad disciplinary areas.

Understanding these differences can facilitate cross-disciplinary communication. It allows scholars from the natural sciences to gain insights into how humanities scholars present their ideas, and vice versa. Moreover, it can reveal the disciplinary conventions and unique academic cultures within each field. For novice writers aspiring to publish their work in international journals, this research can provide practical implications. By understanding the distinct features of RA titles in different disciplines, they can better tailor their writing to meet the expectations of the target journals and enhance their chances of successful publication.

2 Literature Review

In the realm of academic research, the study of journal paper titles has witnessed a remarkable surge in recent years. Scholars have approached this topic from diverse perspectives.

Some researchers have explored the structural dimensions from multiple perspectives. Quantitative analyses (e.g. Letchford et al. 2015; Milojević 2017) identify patterns linked to citation impact, while discourse-based studies (e.g. Hartley 2007; Hyland and Zou 2022) examine rhetorical strategies. Collectively, these works suggest that certain syntactic structures correlate with title effectiveness across disciplines (e.g. Zeng and Liu 2016; Haggan 2004).

Researches on the rhetorical dimensions of titles have also yielded important insights. For example, the studies of (Grant 2013; Hudson 2016; James and Dawn 2016) have shed light on how titles convey meaning and engage readers; Afrida et al. (2015) and Shi and Ren (2010) have demonstrated how titles function as scholarly identity markers. Chen and Liu’s (2023) research further reinforced this perspective. However, these studies predominantly treat titles as homogeneous across disciplines, with limited attention to how rhetorical strategies may differ between the natural sciences and humanities. This oversight suggests that a more nuanced exploration of how titles serve different rhetorical purposes across disciplines is needed.

Similarly, investigations into title-citation relationships (Jacques and Sebire 2010; Jamali and Nikzad 2011; Wei 2017) has established links between title features and citation rates, yet these studies share a comparable limitation. They typically fail to account for fundamental disciplinary differences in both citation practices and epistemological expectations. For example, while Xiao and Zhang (2016) found shorter titles correlate with higher citations in STEM disciplines, this pattern may not apply to social sciences where conceptually rich titles often perform better. Such disciplinary blindness undermines the generalizability of these otherwise valuable findings.

Despite the extensive research on these aspects, a notable limitation persists: most studies do not specifically address the differences between natural sciences and humanities regarding title characteristics. For instance, while Haggan (2004) collected titles from literature, linguistics, and science, the findings suggest differences in pragmatic intent without making a direct comparison between natural sciences and humanities. Similarly, Soler (2007) identified variations in title length and structure between biological and social sciences but did not extend this analysis to a broader comparison.

Further, Xiang and Li (2020) examined titles within linguistics and literature, revealing that even within the same broad disciplinary category, disparities exist. Hao (2024) confirmed disciplinary and generic variations in titles across multiple science disciplines, validating the existence of such differences. This indicates that the differences in title characteristics are more pronounced than previously acknowledged, yet our research aims to focus on the more distinct attributes of natural sciences and humanities titles to offer more targeted insights.

Cross-language perspectives have also been explored, with Soler (2011) analyzing differences between English and Spanish scientific titles, while Li (2021); Tao and Huang (2010); Wang et al. (2011); Xie (2020) focused on English-Chinese contrasts, highlighting linguistic and disciplinary variations. These studies identified significant differences in title types and subtypes along two key dimensions, suggesting that cultural, linguistic and academic discourse practices collectively influence title formulation.

From a diachronic perspective, researches by Ball (2009), Chen and Liu (2023), Jiang and Jiang (2023), and Milojević (2017) indicate that journal paper titles have evolved over time. For instance, Xiang and Li (2020) noted an increase in title length in linguistics and literature, demonstrating that title characteristics are dynamic. Jiang and Hyland (2023) also confirmed that there is a considerable increase in the length of titles coupled with more interrogative and compound titles in six disciplines in the last 60 years.

Against this backdrop, our study aims to address a critical gap by specifically comparing title conventions between the natural sciences and humanities – categories framed by Biglan’s (1973) typology as “hard pure” and “soft pure” sciences. Drawing on Wenger’s (1998) theory of communities of practice, we posit that these academic fields form unique practice communities with inherent linguistic behaviors in title writing, which are constrained by the socialization and communication the authors have experienced in a particular disciplinary and academic culture (Yang 2025). To test this, we examine a corpus of 1,000 titles from six disciplines: chemistry, physics, biology (natural sciences) and literature, philosophy, history (humanities). Grounded in the premise that academic discursive practices reflect disciplinary socialization (Wenger 1998), our analysis focuses on uncovering how titles encode each field’s disciplinary norms and communicative priorities in terms of structural patterns and lexical choices. Following a detailed comparison of title differences between natural sciences and humanities, this research is expected to provide practical guidance for novice writers navigating discipline-specific publication norms, deepen the understanding of academic language diversity, and enhance communication efficiency within and across the academic communities.

3 Corpus

To conduct a thorough and reliable study on the distinct characteristics of journal paper titles in the fields of natural sciences and humanities, a meticulous data collection strategy was formulated. The overarching goal was to gather a representative sample of titles that would enable us to accurately identify and analyze the differences between the two disciplines.

3.1 Data Collection

In the domain of natural sciences, our journal selection was strictly delimited to those indexed by the Science Citation Index (SCI). This approach helped ensure that the selected journals not only met rigorous academic standards but also represented a broad spectrum of research areas, covering core disciplines of physics, chemistry, and biology (hard pure disciplines). For the humanities, we focused on journals indexed in the Art & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI), with in-depth analysis of classic fields such as literary studies, philosophy, and history (soft pure disciplines).

For each discipline, we carefully handpicked three journals. These journals are highly esteemed and widely recognized as leading publications within their respective fields (see Table 1).

Selected journals (2020–2022) of RA title corpus.

| Natural sciences | ||

|---|---|---|

| Chemistry | Physics | Biology |

| Journal of Organic Chemistry | American Journal of Physics | Journal of Cell Biology |

| USA, ISSN 0022-3263 | USA, ISSN 0002-9505 | USA, ISSN 0021-9525 |

| Journal of the American Chemical Society | The Journal of Chemical Physics | Journal of Theoretical Biology |

| USA, ISSN 0002-7863 | USA, ISSN 0021-9606 | USA, ISSN 0022-5193 |

| Macromolecules | Physical Review E | Cell Reports |

| USA, ISSN 0024-9297 | USA, ISSN 0021-9606 | USA, ISSN 2211-1247 |

| Humanities | ||

| Literature | Philosophy | History |

| New Literary History | Journal of the History of philosophy | Journal of Social History |

| USA, ISSN 0028-6087 | USA, ISSN 0022-5053 | USA, ISSN 0022-8762 |

| ELH | British Journal for the History of Philosophy |

Central European History

|

| USA, ISSN 0013-8304 | UK, ISSN 0960-8788 | USA, ISSN 0008-9389 |

| Life Writing | Philosophy Compass | American Historical Review |

| UK, ISSN 1448-4528 | UK, ISSN 1747-9991 | USA, ISSN 0002-8762 |

We limited our sampling period to the years between 2020 and 2022. This relatively recent time frame allowed us to capture the most current trends and practices in academic writing. For each selected journal, we adopted a multi-stage sampling approach. First, we randomly selected a certain number of issues from the three-year period. To determine the number of issues, we considered the journal’s publication frequency. For monthly journals, we randomly selected 6 to 8 issues, while for quarterly journals, we selected 3 to 4 issues.

From each selected issue, we randomly sampled titles. The sample size for each issue was proportional to the total number of articles it contained. For instance, in an issue with 40 articles, we sampled 5 to 8 titles. This proportional sampling strategy ensured diversity in our sample, encompassing various article types, including original research articles, reviews, and research notes.

Following the sampling procedure, the selected titles were systematically organized into two distinct sub-corpora: natural sciences and humanities. Each title was carefully transcribed to preserve original formatting, including special characters, punctuation, and capitalization. In addition to the title text, we extracted and documented the metadata like the journal name, issue number, publication year, and article type (e.g., research article, review). This metadata enables subsequent quantitative and qualitative analyses, such as examining potential correlations between title characteristics (e.g. length, grammatical structures) and contextual factors like journal reputation, publication frequency, or article type. The resulting corpus contained 1,000 titles (11,016 words in total), equally representing both disciplines, thus allowing for systematic comparison of title characteristics across disciplines.

3.2 Procedure of Data Analysis

Following data collection, we implemented a systematic framework of qualitative and quantitative techniques to examine linguistic features of journal article titles across disciplines. The analysis proceeded through three sequential phases: data preprocessing, structural analysis, and lexical-grammatical analysis, employing both corpus analysis tools and manual coding where appropriate.

To ensure analytical validity, the raw dataset underwent rigorous preprocessing: duplicate entries, non-English titles, and interdisciplinary samples were excluded, resulting in two discipline-specific sub-corpora of equal size (natural sciences: N = 500; humanities: N = 500). Subsequently, all retained titles were standardized through removal of special symbols, normalization of punctuation and case unification. The processed datasets were then imported into AntConc 4.0 to construct parallel corpora for comparative analysis.

Regarding structural analysis, the length of the titles, the presence of specific phrases or clauses, and the overall syntactic patterns were examined. Title length was operationalized as the number of tokens. Using AntCon’s Word List function, total word counts were extracted for each sub-corpus, and average title length was calculated. For example, the title “Self-adaptive real-time time-dependent density functional theory for x-ray absorptions” was coded as 9 tokens. Then based on Haggan’s classification (2004), titles were classified into five primary grammatical structures, i.e. nominal phrase (NP), compound phase (CP), verbal phrase (VP), prepositional phrase (PP) and full-sentence (FS). To ensure the validity, the identification and categorization of grammatical structures are double checked by another independent coder, and we achieved inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.93), with discrepancies resolved through joint review.

For lexical-grammatical analysis, we compared the frequency distribution of technical terms in natural sciences versus abstract/culturally-loaded words in humanities using AntConc’s word list feature. The top 10 high-frequency words (including both function words and contents words) from each sub-corpus were extracted, then their syntactic distributions were analyzed. Subsequent part-of-speech (POS) tagging was performed using TreeTagger 3.2.2 tool, achieving 95.4 % accuracy according to manual validation (inter-annotator agreement κ = 0.91). The tagged corpus enabled quantitative comparison of POS categories (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs), revealing significant disciplinary differences in their proportional distributions across title constructions.

The annotated datasets were systematically organized in structured spreadsheets (Microsoft Excel) to facilitate statistical analysis. Using SPSS 20.0, we conducted chi-square tests (α = 0.05) to examine whether the observed differences in grammatical structure frequencies and POS distributions between disciplines were statistically significant. These quantitative findings were subsequently triangulated with qualitative interpretations to explore potential disciplinary conventions underlying the observed variations.

By conducting these detailed qualitative and quantitative analyses on the carefully selected sample titles, we were able to comprehensively compare the titles of natural sciences and humanities. The results of these analyses provided valuable insights into the distinct characteristics and functions of titles in these two broad academic fields, helping us understand how disciplinary differences are reflected in the language of journal paper titles, demonstrating unique community practice with natural sciences and humanities respectively.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 Structural Features

4.1.1 The Length of Titles

In general, the majority of international academic journals have guidelines regarding the title writing, especially the word count of article titles. For example, the London Mathematical Society demands fewer than 12 words, and Journal of the National Cancer Institute requires no more than 14 words (Liu 2017). These differences in guideline adherence and possibly other pressures on title create practical problems for authors (Kerans et al. 2020). Though it is a rigid requirement for each different journal, the discipline also plays an important role in determining how scholars name their RAs.

Hyland and Zou (2022) pointed that title length is important for the retrieval and the eventual citation of articles. The longer the title is, the more information it reveals to its readers. After a careful examination of titles in the corpus, we have noticed some interesting features about the length of titles in natural sciences and humanities, both similarities and differences could be found.

As shown in Table 2, the average length of natural science titles is longer than that of humanities, which is consistent with previous studies (Haggan 2004). Moreover, the longest title (29 words) and the shortest one (1 word) are both from humanities. For instance, “Sufficientarianism” is the shortest one in humanities, while “Nonconjugate Quantum Subsystems” is the shortest in natural sciences, referring to a philosophical and a physical term respectively. However, neither of these titles gives enough information to their readers, thus are not being viewed as a good title, and the number of such titles are not quite big in our corpus.

Word length of titles.

| No. of titles | No. of words | Average title length | The longest | The shortest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural sciences | 500 | 6105 | 12.21 | 25 | 3 |

| Humanities | 500 | 4911 | 9.82 | 29 | 1 |

Xiang and Li (2020) found that the average length of RA titles in linguistics and literature has increased. Our study also shows that the average length of humanities titles is shorter than those in natural sciences, but we further explore the reasons from the perspective of disciplinary research focus and writing norms. As Milojević (2017) pointed out, discipline is the strongest determinant for the average length of titles and the occurrence of different forms of titles. It suggests that authors belonging to different disciplines need to comply with the norms set in their respective fields. In natural sciences, the title is predominantly centered on phenomena, processes, or relationships in the physical world. This is largely because natural sciences are dedicated to exploring and understanding the objective aspects of our surroundings. For example, the title, “Temperature Robustness in Arabidopsis Circadian Clock Models Is Facilitated by Repressive Interactions, Autoregulation, and Three-Node Feedbacks”, reveals under what conditions (repressive interactions, autoregulation, three-node feedbacks) this biological phenomenon (temperature robustness) occurs. Such detailed information leads to a relatively lengthy title. In addition, titles in natural sciences often highlight the discovery, explanation, or application of scientific principles. In many cases, they are designed to communicate new findings or validate existing hypotheses, enabling fellow scientists to quickly recognize the significance of the research and its contribution to the field. The title “A Dichotomy in Cross-Coupling Site Selectivity in a Dihalogenated Heteroarene: Influence of Mononuclear Pd, Pd Clusters, and Pd Nanoparticles – the Case for Exploiting Pd Catalyst Speciation” examplifies this perfectly. Through its precise terminology, it not only locates the study within catalysis niche, but also challenges prior assumptions and highlights a novel discovery, efficiently conveying the research value to peers.

On the other hand, researches in humanities center neither on experimental design nor fixed objective results (Xiang and Li 2020). As a result, titles in humanities are notably diverse and often more flexible compared to those in natural sciences, hence usually shorter. For example, in literary studies, a title such as “Who Bought Paris? Hope Mirrlees, the Hogarth Press, and the Circulation of Modernist Poetry” exemplifies the use of interrogative phrasing to foreground a research question. By directly imposing a question, this style of title not only captures attention and sparks curiosity but also explicitly signals the central inquiry of the study, the dynamics of poetry circulation through specific cultural channels. Metaphorical or allusive expressions are also frequently employed in humanities titles to add artistic and cultural connotations. A title like “A Wrinkle in Medieval Time: Ironing out Issues Regarding Race, Temporality, and the Early English” uses the metaphor of issues regarding race, temporality and the early English being a wrinkle in Medieval Time, conveying the idea that there are many serious problems about early English study. These diverse structural features in humanities titles reflect the nature of the humanities disciplines themselves, which focus on human experiences, cultures, thoughts, and interpretations. They aim to attract a wide range of readers by offering unique perspectives and inviting them to engage in in-depth thinking about various aspects of human life and society.

4.1.2 Grammatical Structures of Titles

The formulation of a title exerts a significant influence on the conveyance of the title’s information and serves as a manifestation of the author’s writing stance. Consequently, a comparative examination of the disparities in the title structures between natural sciences and humanities journals has the potential to disclose the impact of subject variables on the process of title composition. Following Haggan’s (2004) classification, the study focused on the five main grammatical structures of titles: nominal phrase (NP), compound phase (CP), verbal phrase (VP), prepositional phrase (PP) and full-sentence (FS). The distribution of different grammatical structures is shown in Table 3. The further chi-square test showed significant differences (χ2= 242.4, p < 0.05) in grammatical structures between RA titles in natural sciences and humanities.

Distribution of grammatical structures of titles.

| Natural science | Humanities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| NP | 321 | 64.2 | 184 | 36.8 |

| CP | 70 | 14.0 | 292 | 58.4 |

| VP | 28 | 5.6 | 19 | 3.8 |

| PP | 4 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.6 |

| FS | 77 | 15.4 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Total | 500 | 100 | 500 | 100 |

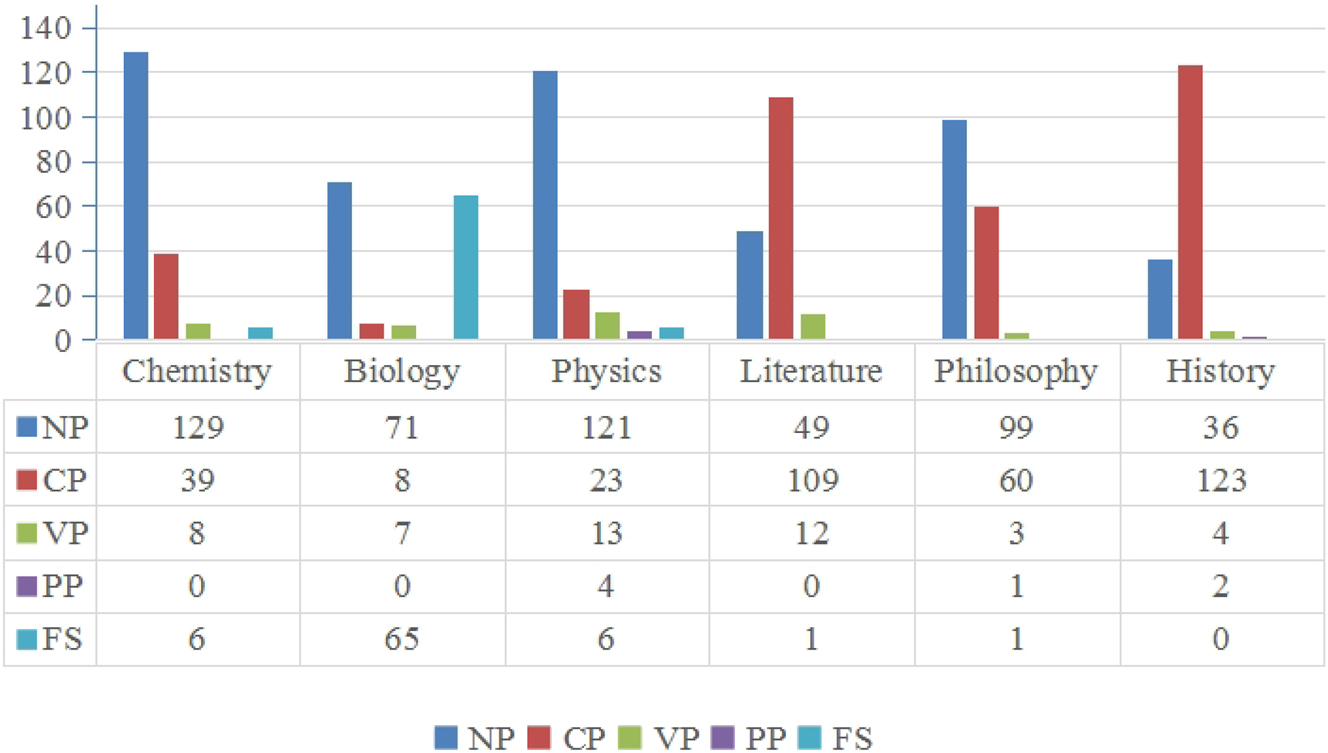

In agreement with previous studies on RA titles (Haggan 2004; Soler 2007; Wang and Bai 2007; Xie 2020), our counts shows that both natural sciences and humanities do not prefer PP titles, accounting for 0.8 % and 0.6 % respectively. The most favorite structure in natural sciences goes to NP, up to 64.2 %, while in humanities, CP gains the most popularity, accounting for 58.4 %. A more detailed illustration of different structural patterns across six disciplines from natural sciences and humanities is presented in Figure 1.

Structural pattern of titles across six disciplines.

As shown in Figure 1, the NP titles are most commonly used in natural sciences, and are observed in every discipline in our corpus. NP titles are noun-centered, free of sentence structure, which can simplify titles in the natural sciences, thus making them less redundant. For example, titles like “Experimental Study on the Conductivity of Nanomaterials” and “Continuous Flow Generation of Acylketene Intermediates via Nitrogen Extrusion” clearly convey that the research involves conducting experiments or undergoing specific procedures. This structure helps readers immediately recognize the methodology used in the research and the general area of focus. While in humanities, the NP titles are used to reveal the content of RA, as in titles like “The Gospel of Creativity” and “The Stoic Comedy of Elizabeth Bishop and Buster Keaton”. Besides, humanities writers tend to use multi-noun structures. We see a title like this, “Japan, the Ambiguous, and My Fragile, Complex and Evolving Self”. Only conjunctions and punctuation have been used to juxtapose five nouns, implying that they are somehow related. However, these titles can never been found in natural sciences, for it does not show any internal relationship among the nouns presented.

The CP title typically employs two-part structure connected by colons (most prevalent), dashes, or occasionally question marks, with periods being increasingly rare in contemporary practice. Compound headings attracted attention as early as the early 1980s. Dillion first discussed the use of colons in the RA titles, arguing that the colons in titles were the main characteristics of academic publications (cited in Liu 2017). As shown in Table 3, CP titles are most welcomed in humanities, and various compound titles are observed in our corpus. For example, the use of question marks in the title “Thales – The ‘First Philosopher’? A Troubled Chapter in the Historiography of Philosophy” is aimed to questioning purposes, activating curiosity of readers towards the research. Colons, dashes, and periods are also employed to structure relationship between title elements. For instance, “Assessing the Neoliberal Kunstlerroman:‘Creative’ Self-Realisation and the Art World in Michael Cunningham’s By Nightfall” uses a colon to separate its theoretical framework (neoliberal artist-novel) from its textual analysis (self-realization critique), while single quotation marks problematize the term ‘creative’, demonstrating how punctuation guides precise scholarly reading. Overall, by using different compound structure, titles in humanities offer a window into the rich tapestry of human experiences, cultures, and ideas, encouraging readers to engage in deep thinking and interpretation, and to view the world from diverse humanistic perspectives.

VP titles rank both the third in natural sciences and humanities. VP titles begin with a verb, followed by one or more noun phrases as an object, and may also use a prepositional phrase as a postmodifier. Such titles are not highly represented in all structures, as shown in the Table 3, with natural sciences accounting for only 5.6 % and the humanities 3.8 %. As Thompson (1993: 185) observed, whereas nominal groups combine grammatical and lexical items to encode multiple semantic functions (e.g. identity, qualities, classification, etc.), verbal groups are lexically streamlined, with their core meaning residing solely in the main verb, which express the Event. For example, titles like “Using a Smartphone Camera to Explore Ray Optics beyond the Thin Lens Equation” and “Exploiting Sodium Coordination in Alternating Monomer Sequences to Toughen Degradable Block Polyester Thermoplastic Elastomers” in natural sciences explicitly encode both the research methodology (smartphone-based experimentation, sodium coordination manipulation) and the scientific objective (extending optical theory, enhancing polymer toughness) within a single action-oriented syntactic frame. On the other hand, VP titles in humanities are typically prioritize conceptual engagement. Titles like “Recovering Franz Kafka’s Asbestos Factory” and “Revisiting the criticisms of rational choice theories” focus primarily on signaling the research domain (Kafka studies, political theory) and intellectual intervention (recovery, critique), often leaving methodological approaches implicit in the argumentation.

PP titles adopt an initial preposition followed by a nominal group. This structure aligns with Halliday and Martin (1993: 213) observation that prepositional phrases lack the logical Head-Modifier structure typical of nominal/verbal groups. Due to this grammatical constraint, where prepositions primarily denote relational rather than substantive meaning, PP titles struggle to encode self-contained research claims. Consequently, they remain statistically marginal in academic titling, accounting for merely 0.8 % of natural science journals and 0.6 % of humanities journals in our corpus. Despite its structural constraints, authors in natural sciences strategically leverage prepositions to achieve functional precision. Titles like “On levitation by blowing” and “Toward Comprehensive Exploration of the Physisorption Space in Porous Pseudomaterials Using an Iterative Mutation Search Algorithm” use directional prepositions (on/toward) to establish the study’s conceptual parameters, while the subsequent nominal groups encode methodological specifies (blowing techniques, iterative mutation search algorithm). This dual functionality allows scientific PP titles to compensate for their grammatical limitations. In contrast, the humanities employ PP titles like “On Sylvia Wynter and Feminist Theory” and “On Acknowledgments” in their more prototypical form. The preposition on here functions primarily as a topical marker, signaling the subject of inquiry without attempting to bundle methodological or theoretical complexity. It is the reflection of humanistic scholarship’s traditional emphasis on interpretive focus rather than procedural transparency.

FS headings are characterized by their SVO or SV structure, which includes both declarative and interrogative sentences. Full sentence construction allows researchers to present the general findings of their research both conclusively and synthetically in one sentence (Soler 2007: 98). A substantially larger proportion of this structural pattern is observable in the natural sciences as compared to the humanities. Consider the following representative examples extracted from natural sciences journals: “Tension Promotes Kinetochore-Microtubule Release by Aurora B Kinase” and “ZNF416 is a Pivotal Transcriptional Regulator of Fibroblast Mechanoactivation”. These titles effectively communicate highly precise details concerning the research scope, central focus, and methodological approach. This clarity facilitates seamless communication among researchers within the discipline, allowing them to swiftly gauge the pertinence of a given study to their own ongoing research efforts. In other words, such titles serve as a sort of shorthand that cuts through the complexity, enabling professionals to quickly identify whether a particular piece of research might hold value for them, thereby streamlining the process of knowledge dissemination and collaboration in the scientific community.

As Figure 1 further illustrates, FS structures mainly appear in biology, which is consistent with Soler’s study (2007). In our study, 65 out of 73 FS titles are from biology. In modern biology, there is a prevalent preference for verb-dominated expressions. The employment of the active voice, which serves to emphasize the key points, effectively conveys the author’s unwavering confidence in their research findings. FS titles are adept at stating and accentuating a distinct idea or conclusion, thereby facilitating clear communication within the scientific community. What’s more, being good at using tenses can also avoid misunderstandings when a particular idea is subsequently refuted or disproven (Zeng and Liu 2016). This is of particular significance in academic and scientific communication, where the accurate conveyance of information over time is crucial to maintaining the integrity and clarity of the discourse. Scholars from natural sciences are able to employ such titles to signify the temporal context of their research outcomes. However, it is essential to note that in situations where research findings are found to be inconsistent or contradictory, the inappropriate application of the present tense within titles has the potential to sow confusion within the academic community.

Conversely, in the field of humanities, there is a greater propensity to utilize interrogative forms to render headlines more engaging and thought-provoking. This interrogative mode of expression is an established and acceptable linguistic convention among members of the humanities speech community, as it serves to incite readers to engage in anticipatory contemplation. For example, such titles like “What is the true meaning of justice in a pluralistic society?” and “Why do we keep revisiting the classics in different eras?” are often seen in humanities. Nevertheless, such an expression holds relatively little significance within the natural sciences domain and is likely to be disregarded or excluded, given the distinct nature of scientific communication and the emphasis on objective, declarative statements.

4.2 Lexical Choices

4.2.1 High-Frequency Words

It is commonly acknowledged that high-frequency words have distinct stylistic specificity (Xiao and Zhang 2016). Natural sciences and humanities journals, belonging to different communities of practice, possess their own sets of terms and concepts. Certain common vocabulary items might carry discrepant definitions across different disciplines, and moreover, a multitude of newly coined words are exclusive to a particular field. The members within these communities continuously employ such specialized words, thereby fortifying the bonds among themselves and generating unique linguistic resources during their interactions. In light of this situation, crafting a title requires integrating subject-specific characteristics. This helps meet disciplinary norms, standardize vocabulary usage, and improve communication clarity within the academic community.

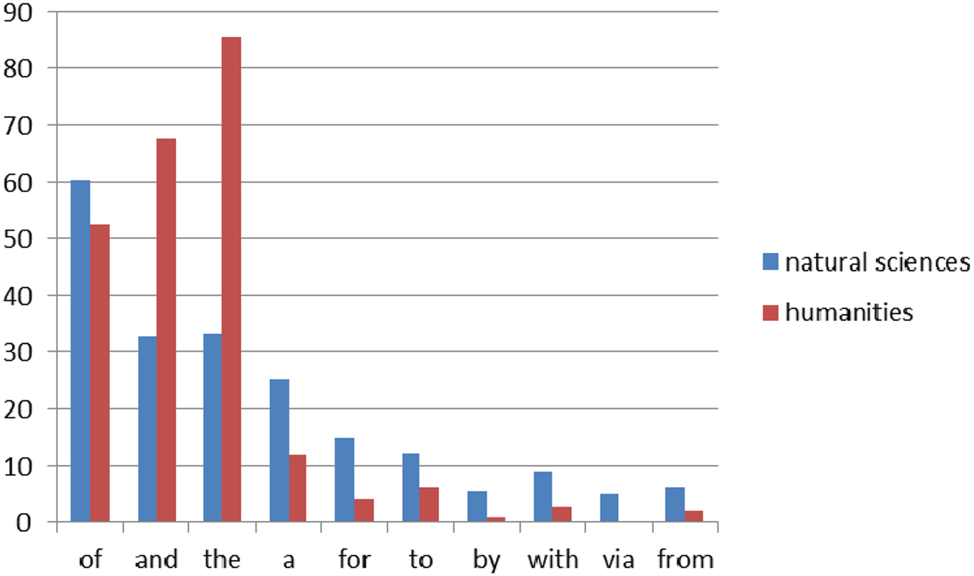

We used Concordant to search for the function and content words used in titles in natural sciences and humanities, and the distributions are shown in Figure 2 and Table 3. As the total number of words in two sub-corpora is not in parallel, we converted the original frequencies into frequencies per thousand words to eliminate the influence of corpus size. As we can see in Figure 2, the occurrence rate of words exhibits distinct disciplinary characteristics. The top 10 function words in our corpus include 7 prepositions (of, for, via, from, to, by, with), 2 articles (the, a), and 1 conjunction (and). Comparative data reveal that prepositions are more likely to appear in the titles of natural sciences. This is mainly because authors in this field need to express specific research methods, conditions, scopes, and results. For instance, four prepositions are used concurrently in “Development of a Concise and Robust Route to a Key Fragment of MCL-1 Inhibitors via Retrospective Defibrillation”, a title from natural sciences.

Distribution of function words (frequency per 1,000 words).

Moreover, the reason why the occurrence of NP titles in natural sciences is significantly higher than those in humanities (as shown in Table 3) is partly due to prepositions facilitating the nominalization of titles through their functions of introduction, transformation, and marking (Xiao and Zhang 2016). In contrast, writers in humanities are more likely to use “and” to create a juxtaposition to explore the relationships between research contents, such as in “Ecological limits: Science, justice, policy, and the good life”.

Regarding the articles, “the” is used much more frequently in humanities than in natural sciences, while “a” appears more often in titles of natural science papers, which is consistent with Nagano’s (2015) study, who has found that hard and soft sciences are quite different in their patterns of direct article use. In English grammar, “the” is typically used before specific persons, books, phenomena, places, times, etc., which are the common subjects of study in the humanities. The definite article can be found in almost every title, like in “Naming Plantations: Toponyms and the Construction of the Plantation system in the English Atlantic”. On the other hand, “a” is used before an abstract or material noun with a modifier to emphasize a particular quality or class. For example, “a” modifies “Intermediate” and “Electrocatalyst” in “A Spectroscopically Observed Iron Nitrosyl Intermediate in the Reduction of Nitrate by a Surface-Conjugated Electrocatalyst” from natural sciences.

Table 4 presents a selection of high-frequency content words prevalent in both the natural sciences and the humanities. The significant disparity in the vocabulary utilized across these two fields strongly suggests that each discipline possesses its distinct set of language resources. Upon close examination of the corpus, it becomes evident that the majority of high-frequency words appearing in the titles of humanities journals are closely associated with temporal concepts (such as history, early, century, war). In contrast, the high-frequency words in natural science titles tend to embody the inherent nature of the discipline (like dynamics, catalyzed, quantum), or signify the research methodologies (for example, model, synthesis) and the objects under investigation (such as effect). This clear differentiation not only reflects the diverse subject matter but also the unique ways in which knowledge is constructed and communicated within each domain.

Content words in natural sciences and humanities.

| Natural sciences | Humanities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Word | Frequency per. 1,000 | Word | Frequency per. 1,000 |

| Synthesis | 6.55 | History | 6.11 |

| Model | 4.26 | Early | 4.68 |

| Dynamics | 4.10 | Philosophy | 4.07 |

| Effect | 3.77 | Century | 3.87 |

| Catalyzed | 2.95 | War | 3.26 |

| Quantum | 2.78 | Ethics | 3.05 |

4.2.2 The Usage of Words of Different Parts of Speech

Besides the differences in terms of high-frequency words used in titles, we further investigate the words of different POS used in titles from these two domains. The result is shown in Table 5. A significant difference is found in POS usage between natural sciences and humanities titles (χ2 = 30.13, p < 0.05), confirming the pattern is statistically reliable.

Words of different parts of speech (frequency per 1,000).

| Natural sciences | Humanities | |

|---|---|---|

| Verbs | 52.42 | 28.30 |

| Nouns | 567.90 | 596.62 |

| Adjectives | 106.47 | 45.61 |

| Adverbs | 6.88 | 7.33 |

As shown in Table 5, the quantities of verbs and adjectives present in the titles of natural sciences are substantially greater than those in humanities. In academic arenas, the annual output of natural science papers is voluminous, dwarfing that of humanities papers by a significant margin. Concurrently, the retrieval of papers predominantly occurs via Internet search engines. This implies that the more keywords a title incorporates, the higher the likelihood of the paper being discovered by those with relevant interests. Within the context of journal papers, the interaction among natural science authors extends beyond mere academic exchange; it is also marked by intense competition. This competitive dynamic directly manifests in their strategic title construction, where authors employ multiple adjectives and verbs to precisely characterize their work. In the title “Development of a Concise and Robust Route to a Key Fragment of MCL-1 Inhibitors via Stereoselective Defluoroborylation”, the author uses three modifiers (concise, robust and stereoselective) simultaneously to outline both the methodological approach and the significance of the findings. In contrast, such a competition-fueled phenomenon is far less pronounced in the realm of humanities journal papers. Here, the focus seems to lie more on the conveyance of ideas in a relatively straightforward manner, perhaps due to the nature of the subject matter, which often centers on interpretations, analyses, and discussions that do not require the same level of highly specific terminological precision as in the natural sciences.

Firstly, with regard to verb usage, papers published in natural science journals exhibit a distinct pattern. Not only do they employ verbs to construct complete sentences as titles, but they also frequently resort to gerunds or the past tense of verbs to modify key or central words. Take, for instance, the title “Benchmarking Isotropic Hyperfine Coupling Constants Using (QTP) DFT Functionals and Coupled Cluster Theory”. In this heading, several verbs in such forms (benchmarking, coupling, using, coupled) are strategically incorporated. In contrast, scholars specializing in humanities also use gerunds when devising titles, as exemplified by “Reading Objects, Watching YouTube, Writing Biography, and Teaching Life Writing: Student Engagement When Learning Online During Covid-19”.

Secondly, titles in both natural sciences and humanities include a large number of nouns, with a similar frequencies per 1,000 words in our corpus (see Table 5). However, the usage of nouns present different pictures in two sub-corpora. For example, proper nouns surface more prevalently in the humanities domain. As we can see in the title “The Right to a Favor: International Scholarships, Clientelism, and the Class Politics of Merit in Post-Revolutionary Mexico” from humanities, multiple proper nouns (the Right to a Favor, International Scholarships, Clientelism, Class Politics, Post-Revolutionary Mexico) are featured. Conversely, the natural sciences lean more towards common nouns, which are often employed as modifiers. Consider the example “Time-resolved Electronic Sum-frequency Generation Spectroscopy with Fluorescence Suppression Using Optical Kerr Gating”. Here, five common nouns (sum-frequency, generation, spectroscopy, fluorescence, suppression) are utilized. This disparity indicates that authors in the humanities tend to focus on specific individuals or entities, while those in the natural sciences direct their attention to broader categories or groups of people or things.

Thirdly, titles in natural sciences employ a greater number of adjectives. This is primarily to enhance the modification of central terms and to convey precise information. For instance, in the title “Cytokine Responsive Networks in Human Colonic Epithelial Organoids Unveil a Molecular Classification of Inflammatory Bowel Disease”, the term “organoids” is meticulously modified by “human”, “colonic”, and “epithelial”.

Finally, when it comes to adverbs, there is relatively little variation in their frequency of appearance across the two fields. This suggests that adverbs play a somewhat similar, and perhaps less prominent, role in both the natural sciences and the humanities in the context of title formulation. Overall, these differences in the usage of different parts of speech mirror the unique characteristics and requirements of each academic discipline.

5 Conclusions

Through a corpus-based comparison of the journal paper titles in natural sciences and humanities, this study has identified substantial differences in their structural features and lexical choices. Natural science titles, on average, are longer. Structurally, noun phrases and full sentences are more prevalent in natural science journals, while humanities journals lean towards compound phrases. Divergent patterns in high-frequency word usage and parts of speech further underscore the unique characteristics of each discipline. These disparities are rooted in the distinct disciplinary cultures and established norms of natural sciences and humanities. Belong to two unique practice communities, scholars from natural sciences and humanities are demonstrating distinct linguistic behaviors in title writing, adhering to their own disciplinary conventions, research methodologies, target audiences, and epistemological frameworks, thereby reflecting their unique communication requirements and intellectual emphases.

This research has significantly enhanced our understanding of disciplinary language differences. By examining the structural and lexical aspects of titles in both fields, we have clearly grasped how natural sciences and humanities communicate research content differently. This understanding equips linguists and scholars to better appreciate the diversity of academic language, recognize the unique intellectual foci of each discipline, and provides valuable insights for academic writing and publishing.

In the context of the evolving academic landscape, interdisciplinary research is on the rise. The findings of this study offer a solid foundation for researchers engaged in interdisciplinary projects that span the natural sciences and humanities. Understanding the language norms of each field is essential for seamless cross-disciplinary communication. This ensures accurate dissemination of research findings and the integration of scientific and humanistic perspectives, thus facilitating the development of interdisciplinary research.

Publishers, too, can benefit greatly from this knowledge. With an understanding of these language differences, they can more effectively organize and promote academic works to the appropriate readership. Whether it’s categorizing natural science papers based on methodological and topical similarities or marketing humanities works with attention-grabbing titles, publishers play an indispensable role in connecting authors with their target audiences, further contributing to the vibrant exchange of academic knowledge.

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, there are limitations. Our corpus is limited to six disciplines and a specific time frame (2020–2022), which may not fully represent the entire spectrum of natural sciences and humanities. Future research could expand the corpus to include more disciplines and a longer time period for a more comprehensive understanding of the differences in journal paper titles.

References

Afrida, H., P. Ayu, and H. W. Dwi. 2015. “Rhetorical Sentences Classification Based on Section Class and Title of Paper for Experimental Technical Papers.” Journal of ICT Research and Applications 9 (3): 288–310. https://doi.org/10.5614/itbj.ict.res.appl.2015.9.3.5.Suche in Google Scholar

Ball, R. 2009. “Scholarly Communication in Transition: The Use of Question Marks in the Titles of Scientific Articles in Medicine, Life Sciences and Physics.” Scientometrics 79 (3): 667–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-007-1984-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Bhatia, V. K. 1993. Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Biglan, A. 1973. “Relationships between the Subject Matter Characteristics and the Structure and Output of University Departments.” Journal of Applied Psychology 57 (2): 204–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0034699.Suche in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, S., M. J. Crawford, N. Ducker, N. Madarbakus-Ring, and A. Lawson. 2020. “Transnational Work and Translingual Practices: Toward a Paradigm Shift in Academic Communication.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 43: 100811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100811.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, X., and H. Liu. 2023. “Academic “Click Bait”: A Diachronic Investigation into the Use of Rhetorical Part in Pragmatics Research Article Titles.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 66: 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2023.101306.Suche in Google Scholar

Flowerdew, J. 2019. “The Linguistic Disadvantage of Scholars Who Write in English as an Additional Language.” Language Teaching 52 (2): 249–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Grant, M. 2013. “Editorial: What Makes a Good Title?” Health Information and Libraries Journal 30 (4): 259–60.Suche in Google Scholar

Haggan, M. 2004. “Research Paper Titles in Literature, Linguistics and Science: Dimensions of Attractions.” Journal of Pragmatics 36 (2): 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-2166(03)00090-0.Suche in Google Scholar

Halliday, M. A. K., and J. R. Martin. 1993. Writing Science: Literacy and Discursive Power. Washington, D.C.: The Falmer Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hao, J. 2024. “Titles in Research Articles and Doctoral Dissertations: Cross-Disciplinary and Cross-Generic Perspectives.” Scientometrics 129 (4): 2285–307, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-024-04941-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Hartley, J. 2007. “Planning that Title: Practices and Preferences for Titles with Colons in Academic Articles.” Library & Information Science Research 29 (4): 553–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2007.05.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Hudson, J. 2016. “An Analysis of the Titles of Papers Submitted to the UK REF in 2014: Authors, Disciplines, and Stylistic Details.” Scientometrics 109 (2): 871–89, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-2081-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Hyland, K. 2016. “Academic Publishing and the Myth of Linguistic Injustice.” Journal of Second Language Writing 31 (1): 58–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2016.01.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Hyland, K., and H. Zou. 2022. “Titles in Research Articles.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 56 (2): 101094, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101094.Suche in Google Scholar

Jacques, T., and N. Sebire. 2010. “The Impact of Article Titles on Citation Hits: An Analysis of General and Specialist Medical Journals.” JRSM Short Reports 1 (1): 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1258/shorts.2009.100020.Suche in Google Scholar

Jamali, H., and M. Nikzad. 2011. “Article Title Type and its Relation with the Number of Downloads and Citations.” Scientometrics 88 (2): 653–61, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0412-z.Suche in Google Scholar

James, M. C., and P. Dawn. 2016. “Do Scholars Follow Betteridge’s Law? the Use of Questions in Journal Article Titles.” Scientometrics 108 (3): 1119–28.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang, F., and K. Hyland. 2023. “Titles in Research Articles: Changes across Time and Discipline.” Learned Publishing 36: 239–48.Suche in Google Scholar

Jiang, G., and Y. Jiang. 2023. “More Diversity, More Complexity, but More Flexibility: Research Article Titles in TESOL Quarterly, 1967–2022.” Scientometrics 128 (7): 3959–80, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04738-x.Suche in Google Scholar

Kerans, M., J. Marshall, A. Murray, and S. Sabaté. 2020. “Research Article Title Content and Form in High-Ranked International Clinical Medicine Journals.” Journal of English for Specific Purposes 60 (6): 127–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2020.06.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Letchford, A., H. S. Moat, and T. Preis. 2015. “The Advantage of Short Paper Titles.” Royal Society Open Science 2 (8): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150266.Suche in Google Scholar

Li, Z. 2021. “A Comparative Study on the Lexico-Syntactic Features of Titles of Social Science Journal Articles in Chinese and English.” Journal of Huaqiao University (Philosophy & Social Sciences) (2): 154–64.Suche in Google Scholar

Lillis, T., and M. J. Curry. 2010. Academic Writing in a Global Context: The Politics and Practices of Publishing in English. Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Liu, Y. 2017. Features of English Academic Titles: A Corpus-based Study. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Menezes, V., and M. Monteiro. 2022. “Linguistic Injustice in Academic Publishing: A Systematic Review.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 56 (2): 101097, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2022.101097.Suche in Google Scholar

Milojević, S. 2017. “The Length and Semantic Structure of Article Titles–Evolving Disciplinary Practices and Correlations with Impact.” Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analysis 2 (2): 1–10, https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2017.00002.Suche in Google Scholar

Nagano, R. L. 2015. “Research Article Titles and Disciplinary Conventions: A Corpus Study of Eight Disciplines.” Journal of Academic Writing 5 (1): 133–44. https://doi.org/10.18552/joaw.v5i1.168.Suche in Google Scholar

Shi, S., and Y. Ren. 2010. “Structures and Pragmatic Functions of Titles of Linguistics Academic Articles: Investigation and Analysis.” Foreign Language Teaching 31 (4): 24–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Singh, S., R. Chaudhary, and S. Suvirya. 2009. “Scientific Precision in Titles of Research Papers Published in Three Dermatology Journals.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 60 (3): 7–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.11.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Soler, V. 2007. “Writing Titles in Science: An Exploratory Study.” English for Specific Purposes 26 (1): 90–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.08.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Soler, V. 2011. “Comparative and Contrastive Observations on Scientific Articles Written in English and Spanish.” English for Specific Purposes 30 (1): 124–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2010.09.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Swales, J. 1990. Genre Analysis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Tao, J., and D. Huang. 2010. “A Corpus-Based Comparative Study on English Titles of Academic Journal Papers: From the Dual Dimensions of Disciplines and Cultures.” Contemporary Foreign Languages Studies 1 (9): 34–9 + 62.Suche in Google Scholar

Thompson, D. 1993. “Arguing for Experimental Facts in Science. A Study of Research Article Results Section in Biochemistry.” Written Communication 10 (1): 106–28, https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088393010001004.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, Y., and Y. Bai. 2007. “A Corpus-Based Syntactic Study of Medical Research Articles.” System 35 (3): 388–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.01.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Wang, L., L. Wang, W. Yong, F. Zhang, Z. Liu, J. Ding, et al.. 2011. “A Corpus-Based Textual Comparative Study on English Titles of Chinese and American Medical Journals.” Chinese Journal of Scientific and Technical Periodicals 22 (5): 784–7.Suche in Google Scholar

Wei, R. 2017. “A Study on the Correlation between the Features of Paper Titles and Their Citations.” Journal of the China Society for Scientific and Technical Information (11): 1148–56.Suche in Google Scholar

Wenger, E. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Xiang, X., and J. Li. 2020. “A Diachronic Comparative Study of Research Article Titles in Linguistics and Literature Journals.” Scientometrics 122 (2): 847–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03329-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Xiao, G., and Z. Zhang. 2016. “A Multi-Dimensional Study on the Features of English Titles of Scientific and Technological Papers: Taking 100 Highly Cited Papers in SCI as Examples.” Chinese Journal of Scientific and Technical Periodicals 27 (10): 1055–60.Suche in Google Scholar

Xie, S. L. 2020. “English Research Article Titles: Cultural and Disciplinary Perspectives.” SAGE Open 10 (2): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020933614.Suche in Google Scholar

Yang, Y. 2025. Unveiling the Construction of Disciplinary Identity of Applied Linguistics in the Chinese Context: A Diachronic Analysis. Hill Publishing Company.Suche in Google Scholar

Zeng, W., and P. Liu. 2016. “Inspirations of Analogical Corpus Analysis for the Writing and Translation of Titles and Abstracts: Taking Original Scientific Research Papers in Nature and Science as Examples.” Chinese Journal of Scientific and Technical Periodicals 27 (2): 223–9.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Shanghai International Studies University

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Research on the Semantic and Pragmatic Reasoning of Chinese Hyperbolic Numerical Idioms Based on the Bayesian Model

- Compilation and Analysis of a Parallel English-Arabic Corpus of Stand-Up Comedy Shows Subtitles

- Stance Markers in Industry Report: A Corpus-Based Study of the Deloitte Art & Finance Report

- The Reception of Auteurs: Data Mining Reviews of Wes Anderson’s Films

- Balanced or Biased? Voice Engagement in Australian News Media’s Communication of China

- Differences in Journal Paper Titles between Natural Sciences and Humanities: A Corpus-based Analysis

- Mental Distress in English Posts from r/AmITheAsshole Subreddit Community with Language Models

- Modelling Differences in Multiword Expression Use Across Proficiency Levels in a Test of Spoken English

- Book Reviews

- Di Cristofaro, M: Corpus Approaches to Language in Social Media

- L. S. Ming and C. Sin-wai: Applying Technology to Language and Translation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Research on the Semantic and Pragmatic Reasoning of Chinese Hyperbolic Numerical Idioms Based on the Bayesian Model

- Compilation and Analysis of a Parallel English-Arabic Corpus of Stand-Up Comedy Shows Subtitles

- Stance Markers in Industry Report: A Corpus-Based Study of the Deloitte Art & Finance Report

- The Reception of Auteurs: Data Mining Reviews of Wes Anderson’s Films

- Balanced or Biased? Voice Engagement in Australian News Media’s Communication of China

- Differences in Journal Paper Titles between Natural Sciences and Humanities: A Corpus-based Analysis

- Mental Distress in English Posts from r/AmITheAsshole Subreddit Community with Language Models

- Modelling Differences in Multiword Expression Use Across Proficiency Levels in a Test of Spoken English

- Book Reviews

- Di Cristofaro, M: Corpus Approaches to Language in Social Media

- L. S. Ming and C. Sin-wai: Applying Technology to Language and Translation