Abstract

Oil and gas pipelines play an important role in the energy transportation industry, but metal corrosion can affect the safe operation of pipeline equipment. This study uses CiteSpace software to synthesize and analyze corrosion models and keywords from research institutions, countries, and methods related to pipeline corrosion prediction. The investigation into the mechanisms of pipeline metal corrosion, with a specific emphasis on CO 2 and H2S corrosion, has revealed that several factors influence the process, including temperature, partial pressure, medium composition and the corrosion product film. In addition, the study provides a comprehensive review of pipeline corrosion prediction methods and models. These include traditional empirical, semi-empirical, and mechanism-based prediction models, as well as advanced machine learning techniques such as random forest, artificial neural network model, support vector machine, and dose-response function. Although there are many ways to improve model performance, no universally accepted methods have been established. Therefore, further in-depth research is needed to improve the accuracy of these models and provide guidance for improving the operational safety of pipelines.

1 Introduction

The utilization of pipelines enables the cost-effective and secure transportation of fluids, making them extensively employed in the conveyance of oil and gas (Aamo 2016). The global oil and gas pipeline network had a total length of approximately 3.55 × 106 km as of 2017, with natural gas pipelines accounting for approximately 2.97 × 106 km and oil pipelines covering approximately 5.84 × 105 km. It was projected that by 2023, the combined length of global oil and gas trunk pipelines will reach around 2.15 × 106 km (Hussain et al. 2024). The challenge of corrosion poses a significant threat to pipeline infrastructure, as it can result in its destruction, create safety hazards, and cause environmental pollution during the service life of pipelines. The annual cost of corrosion in China amounts to $276 billion, equivalent to approximately 3.1 % of the GDP (Hou et al. 2017; Li et al. 2015). Looking around the world, the annual global economic impact of corrosion exceeds $4 trillion. The corrosion of pipeline metal in the petrochemical industry can result in the release of hazardous substances (Ren et al. 2018; Shivananju et al. 2013). According to statistical data, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) reported a total of 5,709 significant pipeline incidents that transpired in the United States between 1998 and 2017. Notably, corrosion failure was responsible for approximately 20 % of these occurrences (Peng et al. 2021). Statistics from the European Gas Pipeline Incident Data Group (EGIG) indicated that 25 % of gas pipeline failures were caused by corrosion (Wang et al. 2023b). The harm of corrosion to the pipeline is also reflected in the control of these assets, according to statistics, the replacement cost per kilometer of pipeline is about 643,800 US dollars, facing a lot of investment risk (Hussain et al. 2024). In the United States, Canada, and other countries, regulatory bodies have been established to oversee the oil and gas industry. For instance, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) oversees the interstate natural gas pipeline industry, while the Pipeline Safety Office (OPS) and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), under the Department of Transportation, are responsible for regulating onshore pipelines of hazardous liquids and gases (Papavinasam 2014). The detrimental impact of corrosion cannot be disregarded. Therefore, it is imperative to gain a comprehensive understanding of the corrosion mechanism and behavior, as well as conduct pertinent research on effective monitoring and prediction of corrosion rate.

At present, the research on corrosion prediction has reached a significant level of advancement. In 1974, Legault and Leckie et al. established the quantitative relationship between corrosion rate and chemical composition of 270 steel types (Legault and Leckie 1974) by analyzing 15.5 years of atmospheric exposure data obtained by Larrabee and Coburn (Larrabee and Coburn 1961). The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) adopted this result in 1995 as a guiding standard, ASTM G101-94, to predict the corrosion resistance of steel in atmospheric environments (American Society for Testing and Materials 1995). In the past, laboratory accelerated corrosion tests were commonly used by scholars to predict corrosion conditions. However, this method is severely limited in terms of its ability to accurately reflect metal corrosion conditions in service (Wu et al. 2019). With the advancement of computer technology, significant progress has been made in the application of mathematical models to understand the evolution process of metal corrosion. These models include artificial neural network models (Jiang et al. 2016; Pei et al. 2020), random forest models (Zhi et al. 2021), and support vector machines (Jiménez-Come et al. 2018). However, these digital models often necessitate a substantial number of experimental parameters as a foundation, thereby introducing inherent inaccuracies. Machine learning technology still stays in the laboratory stage, and the lack of field analysis and prediction of pipeline corrosion conditions, resulting in the practical value of these models being slightly insufficient, but also needs to be further explored by researchers (Hussain et al. 2024).

The present study employs CiteSpace (Chen 2005; Chen et al. 2015) to conduct a hotspot analysis of pipeline metal corrosion models, aiming to identify key terms and institutions, thereby uncovering less explored research directions. The focus of this study lies in the investigation of CO2 and H2S corrosion, providing a comprehensive analysis of pipeline corrosion mechanisms. Meanwhile, a review of pipeline corrosion prediction methods is presented, including the principles and methods of various corrosion prediction models. This study aims to enhance innovation and advancement in the domain of pipeline corrosion prediction through a comprehensive review of pertinent methodologies, with the objective of mitigating safety concerns arising from corrosion.

2 Hot spot analysis of corrosion model based on CiteSpace

2.1 Data sources

The data sources include the core database of Web of Science and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) project. In order to avoid information redundancy caused by repeated search and enhance search precision, “corrosion prediction” is employed as the primary keyword in the document retrieval process. It was found that from January 1, 2015 to July 31, 2024, a total of 8,064 papers have been published on Web of Science, and 861 papers have been published on CNKI, which is a key research area within the industry. To enhance the representativeness of the data, additional pipeline materials such as carbon steel X60, X70, and X80 were included as subject terms. The search query “corrosion prediction & (pipeline || carbon steel ||X60 ||X70 ||X80)” was then employed to filter and identify relevant results from the aforementioned dataset. After removing irrelevant literatures, 1,355 and 505 valid literatures were obtained from the Web of Science and CNKI, respectively. Subsequently, the obtained results were imported into the CiteSpace software for conducting data analysis and visualization of the distribution and co-occurrence patterns among countries, research institutions, and authors as keywords.

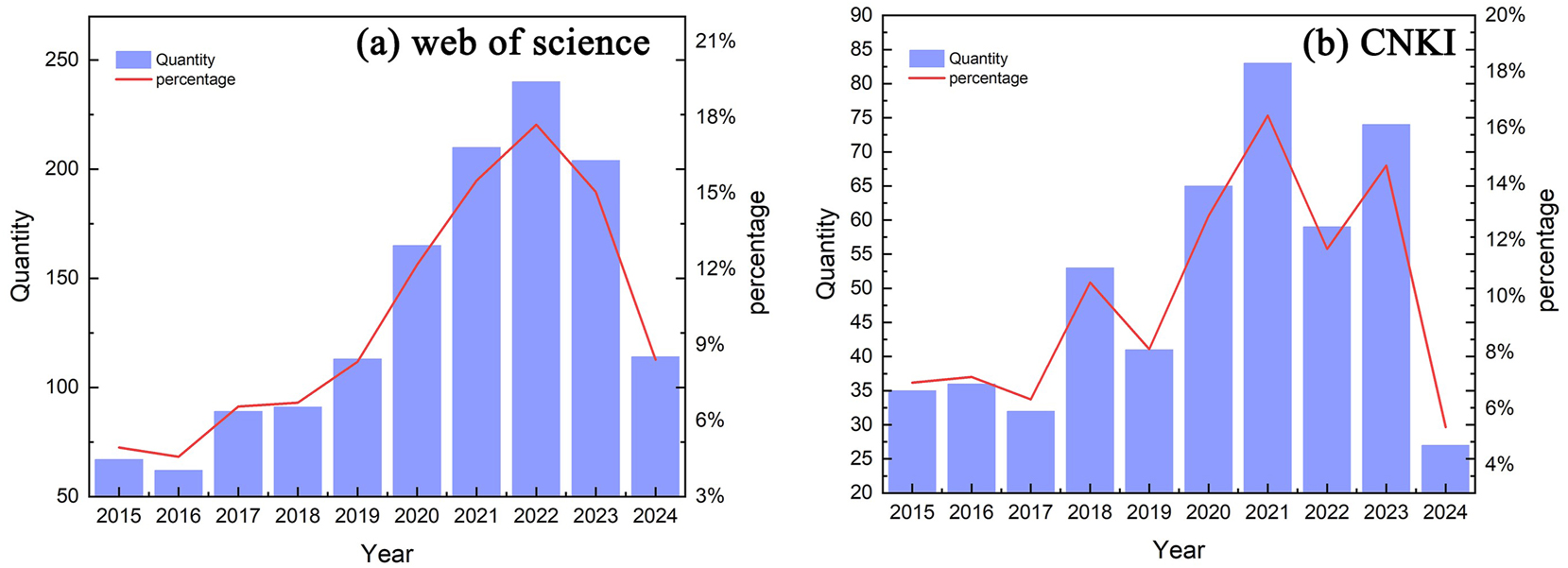

Figure 1(a) illustrates the trajectory of the number of publications retrieved from the Web of Science between January 1, 2015, and July 31, 2024. The figure illustrates a general upward trend in the number of publications, with a minor peak observed in 2017. Notably, during the period from 2020 to 2022, there was a significant surge in publication rates, followed by a slight decline in 2023. Figure 1(b) shows the change in the number of articles retrieved from CNKI from January 1, 2015 to July 31, 2024. The figure shown illustrates significant fluctuations in the total number of cases, with each spike being followed by a decline in the following year. Particularly, two notable peaks were observed in 2018 and 2021, while comparatively lower numbers were reported for 2019 and 2022.

The number of articles retrieved from (a) web of science and (b) CNKI.

2.2 Data analysis

CiteSpace is a knowledge visualization software that enables the analysis and statistical summarization of literature in a specific discipline, considering factors such as authors, institutions, and keywords (Chen 2005; Chen et al. 2015). It generates a visual knowledge map to provide a comprehensive overview of the current information landscape and the developmental trajectory of the field. Moreover, it assists researchers in identifying high-quality literature, cutting-edge research, and future directions. This capability holds great significance in uncovering emerging trends within the field. The software has garnered widespread recognition from scholars both domestically and internationally.

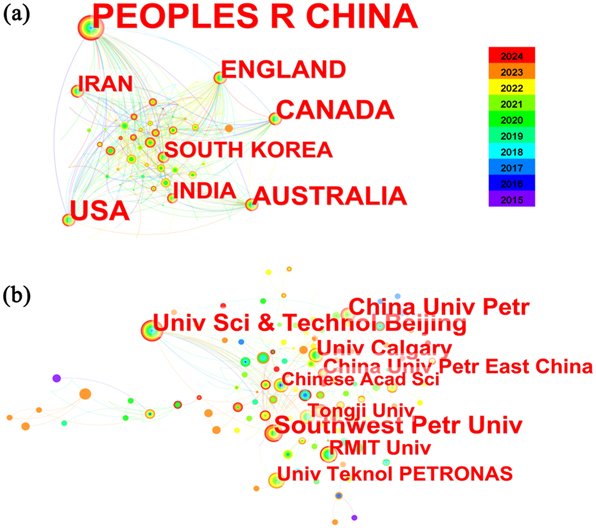

2.2.1 Main research institutions

An analysis of inter-country and inter-institutional partnerships can facilitate an understanding of the manner in which pipeline corrosion prediction models are being researched across countries and institutions. Due to the limitations of CiteSpace in analyzing national and institutional data from CNKI, this paper exclusively presents analysis results derived from Web of Science. The maps of country and institution relationships from January 1, 2015 to July 31, 2024 are depicted in Figure 2(a) and (b), respectively. After comprehensive analysis, a total of 80 countries have contributed to the existing literature on this topic during the period from January 1, 2015 to July 31, 2024. Notably, China, Canada, the United States, Australia, England, South Korea, India and Iran emerged as prominent contributors in this field. The institutional collaboration network map reveals that the institutions with the highest publication count include China University of Petroleum, Southwest Petroleum University, Beijing University of Science and Technology, Malaysia National University of Petroleum Technology, and Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. In a cooperative network, centrality serves as a metric to assess the significance of a node within the network. Based on the graphical representation, it is evident that Southwest Petroleum University and Beijing University of Science and Technology emerge as the most prominent institutions in this institutional cooperative network.

Map of partnerships: (a) Country, (b) institution.

2.2.2 Keyword analysis

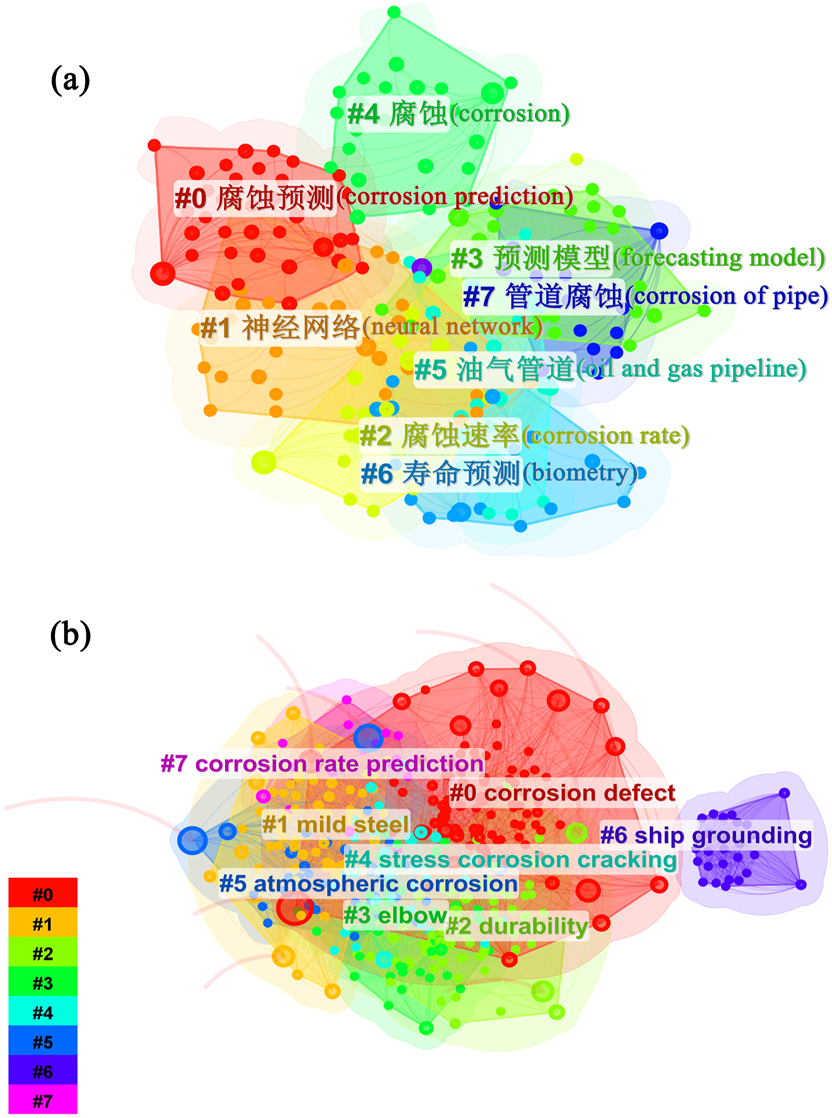

The keyword cluster analysis is shown in Figure 3. Figure 3(a) illustrates that from January 1, 2015 to July 31, 2024, corrosion prediction model research in the field of Web of Science predominantly focuses on keywords such as “corrosion defect”, “mild steel”, “durability”, “elbow”, “stress corrosion cracking”, “atmospheric corrosion”, “ship grounding” and “corrosion rate prediction”. As illustrated in Figure 3(b), the keywords within the CNKI encompass “corrosion prediction”, “neural networks”, “corrosion rate”, “forecasting model”, “corrosion”, “oil and gas pipeline”, “biometry”, and “corrosion of pipeline”.

Keyword cluster analysis diagram: (a) Web of science, (b) CNKI.

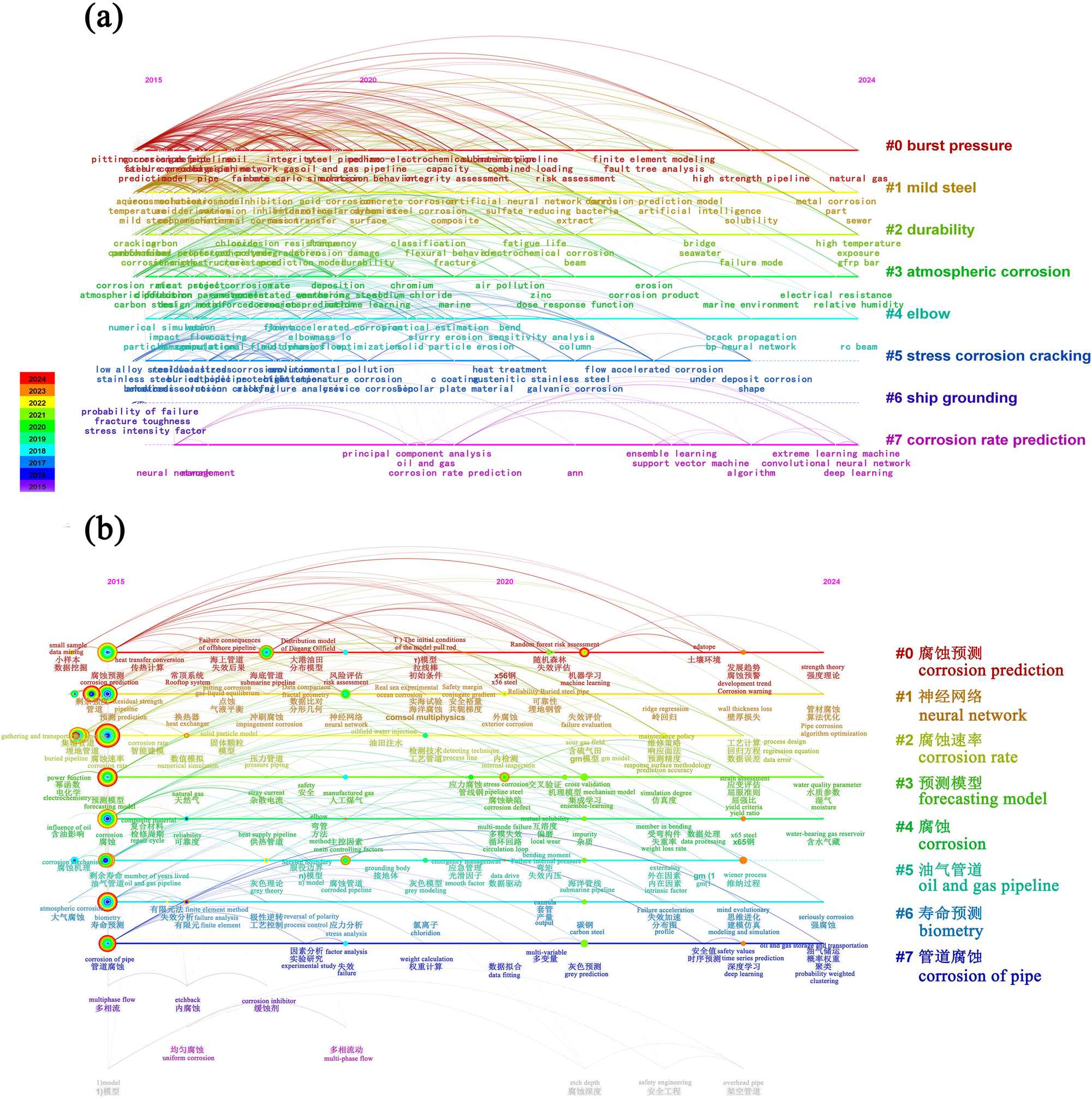

Figure 4(a) and (b) show the time spectra of keyword clustering in the Web of Science and the CNKI from January 1, 2015 to July 31, 2024, respectively. As can be seen through the time mapping, pipeline corrosion has been repeatedly studied over the past decade, in which more studies have been conducted on marine pipelines, with corrosion environments focusing on the atmosphere, soil and marine. Corrosion analysis focuses on corrosion fatigue, stress corrosion cracking, burst pressure and durability, where accelerated corrosion experiments are often used for the above studies. Relevant literature on corrosion prediction has been published since 2015, with corrosion prediction tools such as neural networks, deep learning, and machine learning.

The time spectra of keyword clustering in (a) web of science and (b) CNKI.

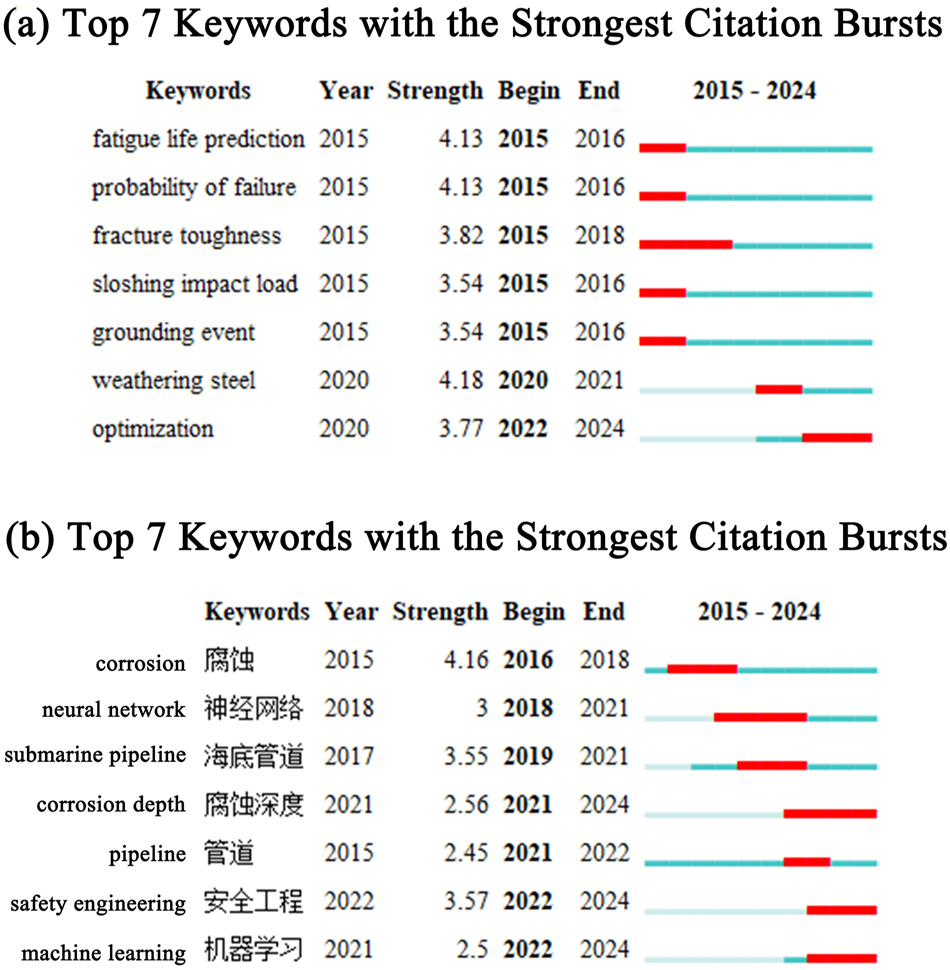

Through the emergent analysis conducted by CiteSpace, we can gain profound insights into the temporal patterns of sudden keyword surges, thereby facilitating a comprehensive understanding of research focal points during each respective time period. The emergent keyword results calculated by CiteSpace for the period from January 1, 2015 to July 31, 2024 are depicted in Figure 5. Figure 5(a) illustrates a significant surge in the number of articles within the Web of Science database, focusing on keywords such as “fatigue life prediction”, “probability of failure”, “sloshing impact load”, and “grounding event” during the period from 2015 to 2016. This observation highlights the emergence of these topics as prominent research areas at that time. Following the year 2020, the primary research focus underwent a shift towards “weathering steel” and “optimization”. As shown in Figure 5(b), the duration of the sudden results obtained from CNKI tends to be longer. The research areas of “pipeline”, “submarine pipeline”, “corrosion” and “neural network” have emerged as the leading directions, while “safety engineering” and “machine learning” have recently gained attention as research hotspots, indicating untapped potential for further exploration.

Top 7 keywords with the strongest citation bursts in (a) web of science and (b) CNKI.

Through a comprehensive literature analysis study conducted using CiteSpace over the past decade, it is evident that carbon steel-based pipelines have been the primary focus of research, with particular emphasis on investigating their lifespan. The predominant research approach involves conducting accelerated corrosion experiments to observe both metal corrosion fatigue and corrosion behavior. Currently, there is a scarcity of literature on the application of various algorithms for corrosion prediction. Therefore, it is imperative to conduct research on corrosion prediction models. To achieve this, it becomes essential to commence with an exploration of corrosion mechanisms and prediction methods employed in corrosion modeling, followed by a comprehensive review and synthesis of the mechanisms and methods utilized in previous studies.

3 Research on corrosion mechanism of pipeline metal

Under different working conditions, the form of corrosion will be different. The form of corrosion can be divided into localized corrosion, uniform corrosion, pitting corrosion, intergranular corrosion, crevice corrosion, stress corrosion cracking. The type of corrosion failure experienced by metal structures varies according to the service environment and the transport medium. Specifically, in the context of pipeline corrosion, failure types are generally categorized into two primary classifications: external corrosion and internal corrosion. This distinction is crucial for the accurate assessment and mitigation of corrosion risks associated with pipeline integrity and longevity. External corrosion means that the surface of the pipeline is affected by the external environment, while internal corrosion refers to the influence of the medium inside the pipeline.

3.1 External corrosion

The environment of the pipeline usually includes ocean, soil, atmosphere, etc. Due to the specific regular shape and stress of the pipeline, its corrosion characteristics need to be analyzed according to specific environmental conditions.

Seawater is a kind of electrolyte solution rich in oxygen and salt with a certain flow rate. Seawater corrosion is electrochemical corrosion. Temperature, dissolved oxygen, salinity, flow rate and so on are the important factors affecting the external corrosion of pipelines. The effect of temperature is reflected in changing the metal electrode potential, in general, the higher the temperature, the corrosion resistance of the metal decreases. Dissolved oxygen in seawater decreases first and then increases with the increase of depth. Dissolved oxygen in surface seawater is almost saturated, so the corrosion in surface seawater is the most serious. Salinity affects the oxygen content and resistivity of seawater, which in turn affects the corrosion rate. Zhu’s (Zhu et al. 2022) experiments show that when the salt content of seawater is 1.75 %, the corrosion rate of metal pipes reaches its maximum. The influence of flow rate on corrosion is reflected in two aspects. When the flow rate is low, the content of dissolved oxygen increases and the corrosion rate accelerates. When the flow rate exceeds a certain value, the corrosion passivation film on the metal surface is destroyed, greatly accelerating the corrosion rate (Nowell et al. 1982; Wang et al. 2023a).

Soil is also a common service environment for pipelines. Soil contains complex components, including water, salt, microorganisms etc. Different types of corrosion may occur in the soil. Soil resistivity is a measure of soil electrical conductivity index, the higher the soil resistivity, the lower the corrosion rate. The moisture content of soil is one of the important factors affecting the corrosion rate. The wet soil and salts form electrolyte solution, which causes electrochemical corrosion to metals. The degree of soil looseness is directly related to the amount of oxygen content, and also has a great impact on pipeline corrosion. The pH value of the soil is generally in the neutral range, and as the pH value decreases, the corrosion of the soil increases sharply. Microbial corrosion is a kind of electrochemical corrosion. Under the appropriate conditions, pipeline can come into contact with microorganisms, triggering certain chemical reactions that lead to corrosion.

Atmospheric corrosion is mainly related to temperature, humidity, oxygen content and other factors, and is closely related to the season, weather and geographical environment, and the actual corrosion degree is not the same, such as corrosion rates and types.

3.2 Internal corrosion

With the upgrading of pipeline manufacturing technology, the threat of external corrosion to pipeline safety is gradually reduced, and the risk of internal corrosion is becoming more prominent. At present, the research of corrosion mechanism in pipeline mainly focuses on CO2 corrosion and H2S corrosion. In the process of pipeline transportation, natural gas and crude oil usually contain many impurities, CO2 and H2S are common impurities (Ma et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2024a).

3.2.1 CO2 corrosion

CO2 is a naturally occurring substance. During the extraction of oil and gas, CO2 is extracted along with other gases, which can cause corrosion of pipelines (Tantawy et al. 2020). Localized pitting, tuberculation, and platform corrosion are prominent manifestations of CO2 corrosion (Videm and Dugstad 1990). The process of carbon dioxide corrosion is commonly believed to encompass the following stages.

CO2 dissolves in water and reacts to form carbonic acid:

Carbonic acid in the solution reacts with iron, forming corrosion of iron:

Fe(HCO3)2 is unstable at high temperatures and easily breaks down into FeCO3:

CO2 corrosion is affected by temperature, CO2 partial pressure, high chloride concentration, corrosion product film, erosion, among other factors. The aforementioned factors contribute to severe localized corrosion and perforation, thereby posing significant security risks. The prevailing belief is that the primary constituents of the protective film consist of FeCO3, Fe3O4, FeS and oxides derived from alloy elements. The corrosion of CO2 is influenced by temperature, which in turn affects the chemical reaction and characteristics of the corrosion product film. As a result, different environmental conditions and pipeline materials exhibit varying degrees of corrosion. The specific conditions of the corrosion film under different temperature influences are presented in Table 1. Below 60 °C, De Waard (De Waard and Lotz 1995) proposed an empirical formula to describe the impact of CO2 corrosion on carbon steel and low-alloy steel.

where V is the corrosion rate, pCO2 is the partial pressure of CO2, T is the temperature.

Effect of temperature on metal corrosion film (Li Chunfu et al. 2004).

| T (°C) | Main product | Protective film traits | Corrosion characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| <60 | FeCO3 | Soft without adhesion | Smooth metal surface |

| 60–110 | FeCO3 | Somewhat protective | Local corrosion protruding |

| Near 110 | FeCO3 coarse crystal | Thick and loose | High uniform corrosion rate and severe local corrosion |

| >150 | FeCO3、Fe3O4 | Dense adhesion is strong | The corrosion rate is low |

The partial pressure of CO2 is also a critical factor influencing CO2 corrosion. It is widely acknowledged that an elevated pCO2 level leads to an accelerated corrosion rate at a given temperature. The effect of CO2 partial pressure on CO2 corrosion was investigated by Lohodny–Sarc (Lohodny-Sarc 1994), revealing distinct corrosion morphologies of metals under varying CO2 partial pressures, as presented in Table 2. The influence of pH value on CO2 corrosion primarily manifests in the formation of corrosion products. At a pH level around 10, the predominant corrosion products are Fe(HCO3)2 and FeCO3. Conversely, at a pH range of 4–6, FeCO3 is formed as the primary corrosion product. Simultaneously, the pH value exerts an influence on the concentration of H+ ions within the solution. As the pH level escalates, there is a concomitant reduction in the concentration of H+ ions, consequently leading to a decrease in corrosion rate. The presence of oxygen significantly influences the corrosion behavior of carbon steel in CO2 environments. In the absence of a protective film, oxygen greatly accelerates the corrosion rate; however, when a protective film is already formed, its impact on the corrosion rate becomes negligible (Mcintire et al. 1990). In addition, the corrosion rate is significantly influenced by flow velocity. Specifically, a higher flow velocity corresponds to an increased corrosion rate.

Effect of CO2 partial pressure on CO2 corrosion (Lohodny-Sarc 1994).

| CO2 partial pressure | Corrosion characteristics |

|---|---|

| pCO2 > 0.21 MPa | Severe local corrosion |

| 0.21 MPa > pCO2 > 0.0483 MPa | Small hole corrosion |

| 0.0483 MPa > pCO2 > 0.021 MPa | Full uniform corrosion |

| pCO2 < 0.021 MPa | Almost no corrosion occurs |

High chloride concentration is also an important influencing factor. Pessu et al. (2020) explored the influence of chloride ion content on carbon dioxide corrosion of carbon steel, and found that the pitting corrosion was most serious when the chloride ion concentration was 10 % and the temperature was 50–80 °C, but there was a chloride threshold when the temperature was below 30 °C, and the chloride ion concentration had little influence on the corrosion rate. Under ambient temperature and pressure conditions, the presence of Cl− reduces the solubility of CO2 in the medium, thereby slowing down the CO2 corrosion rate in pipelines. However, under high-temperature and high-pressure environments, the high-pressure conditions significantly enhance the adsorption capacity of Cl−, leading to the adsorption of a large amount of Cl− on the surface of carbon steel. The erosive effect of Cl− creates micro-gaps between the corrosion product film and the carbon steel substrate, weakening the bonding force between the corrosion product film and the carbon steel substrate. This process results in the detachment of the corrosion product film, exposing part of the carbon steel substrate directly to the corrosive medium, accelerating the corrosion rate of the substrate, and potentially causing more severe localized corrosion (Chen et al. 2003).

3.2.2 H2S corrosion

The expansion of oil and gas exploration has led to an increase in the size of high H2S content wells, thereby introducing significant corrosion risks to pipeline equipment and oilfield facilities. Consequently, the presence of H2S gas poses both safety hazards and economic losses.

The solubility of H2S in water surpasses that of CO2 and O2, while its corrosion process in aqueous environments can be described as follows (Vakili et al. 2024):

In the context of H2S corrosion, the formation of a compact iron sulfide film exhibits a certain degree of corrosion inhibition, whereas an insufficiently dense film transforms iron sulfide into the cathode and accelerates steel surface corrosion. The electrochemical corrosion of H2S aqueous solution also generates hydrogen as a byproduct, which can compromise the structural integrity of the iron-based matrix and result in hydrogen embrittlement. When the H2S concentration is low, the corrosion products consist of FeS2, FeS, and a minor proportion of Fe9S8. As the H2S concentration increases, there is an elevated presence of Fe9S8 in the corrosion products. The crystal lattice structure of both FeS2 and FeS exhibits greater compactness compared to that of Fe9S8, resulting in superior protective properties for the former.

A.S. Guzenkova et al. (2021) studied the corrosion rate and nature of corrosion in X60 pipeline steel in Samotlor and Usinsk oilfield simulation solution and saturated hydrogen sulfide solution (NACE) medium. It was found that the corrosion rate was the fastest, pH value was the lowest and the number of pitting corrosion was the highest in saturated hydrogen sulfide solution (Table 3).

Influence of different flow media (V = 1 m/s) on the corrosion rate and properties of steel.

| Model medium | Corrosion rate g/(m2·h) | Nature of corrosion |

|---|---|---|

| Samotlor | 1.27 | Surface covered with a coating of dark and straw (orange) color products. Uniform corrosion observed at a specimen surface after corrosion product removal |

| Usinsk | 1.86 | Surface covered with a layer of dark and straw (orange) color products. Specimen surface contains shallow points after corrosion product removal |

| NACE medium according to standard TM 0177-2006 (National Association of Corrosion Engineers 2006) | 2.38 | Dark loose film difficult to remove. Specimen surface contains numerous shallow points after corrosion product removal |

3.2.3 Coexistence of CO2 and H2S

During the transportation of oil and gas, the combined effect of acidic gases such as H2S and CO2 can lead to severe corrosion in pipelines (Farhadian et al. 2023; Hu et al. 2017). In the presence of coexistence of CO2 and H2S, it is widely accepted that H2S can expedite CO2 corrosion through cathodic reactions while mitigating corrosion via FeS precipitation. The predominant influencing factor in the corrosion process is determined by the relative content of these two species. It can be roughly determined who plays a leading role in the corrosion process by

Corrosion in the coexistence of CO2 and H2S.

| Conditions | Dominance | Temperature (°C) | Corrosion products |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

CO2 | <120 | Dense FeS membrane |

|

|

H2S | 60∼240 | FeS film is stable |

| <60 °C or > 240 | FeS film is unstable and porous |

Under the coexistence conditions, variations in pH value, temperature, and flow rate exhibit distinct influences on the corrosion behavior. When the pH value is excessively low, an inadequately sulfur-containing iron sulfide (such as Fe9S8) predominates as the main product, resulting in the formation of a protective film that lacks sufficient protection. Consequently, this phenomenon further accelerates the corrosion rate of steel. The content of FeS2 increases proportionally as the pH value of the solution gradually rises. Consequently, under high pH conditions, a film layer predominantly composed of FeS2 is formed, exhibiting a certain level of steel protection.

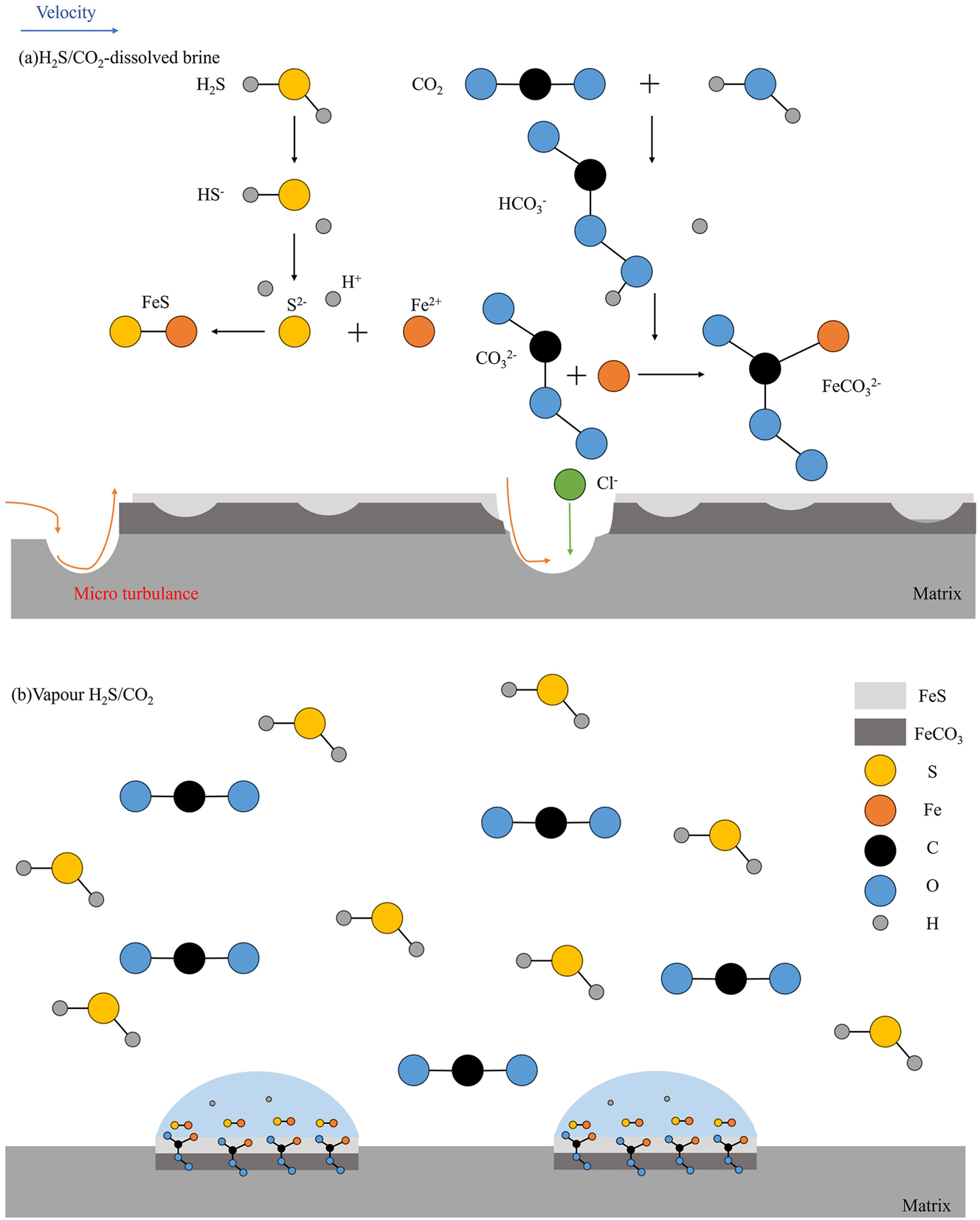

The impact of temperature on H2S and CO2 corrosion is primarily manifested in three distinct aspects (Huang et al. 2023). Firstly, temperature affects the solubility of gases (CO2 or H2S) in the medium. An increase in temperature results in a decrease in solubility, thereby impeding the corrosion process. Secondly, elevated temperatures accelerate the rate of each reaction, thereby promoting the corrosion process. Ultimately, an increase in temperature affects the film-forming mechanism of corrosion products, enabling the film to either impede or facilitate corrosion. The study conducted by Qin et al. revealed that, in the case of X65 steel, the corrosion factors in two different environments (steam of the H2S and CO2, dissolved brine of the H2S and CO2) follow the order of H2S>>CO2 > temperature (Qin et al. 2022). The corrosion mechanism of H2S and CO2 acting together in two environments is illustrated in Figure 6. In the aqueous solution, ionization of CO2 and H2S leads to their combination with Fe2+, resulting in corrosion. Conversely, in the gas phase environment, corrosion predominantly occurs at water location.

Diagrams of H2S and CO2 corrosion mechanisms: (a) In solution and (b) in vapour (Qin et al. 2022).

3.3 Erosion corrosion

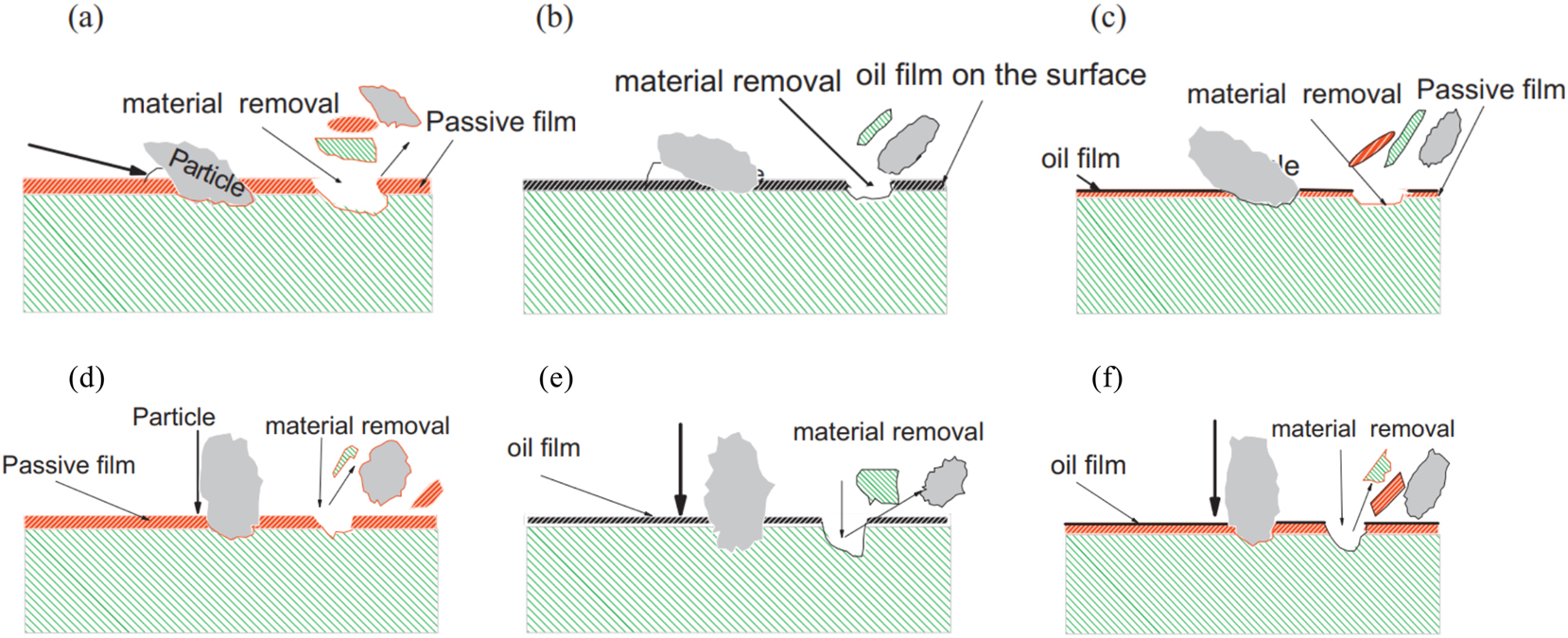

Erosion corrosion poses a significant challenge in the transportation of corrosive substances through pipelines (Stack and Abdulrahman 2012). The tube wall undergoes rapid thinning due to the synergistic effect of erosion corrosion, resulting in significant material loss and posing potential safety hazards (Lu et al. 2011). The erosion corrosion processes are primarily influenced by hydrodynamic parameters, solid particle characteristics, temperature, chemical composition of the corrosive slurry, and mechanical properties of the target material (Shahali et al. 2019; Stack et al. 1999; Xu et al. 2020). Shahali et al. found that the erosion-corrosion rate increased by 104 times compared to the stagnant state, as the impact velocity increased and the surface activity of the corrosive medium increased (Shahali et al. 2019). Stack et al. also arrived at similar conclusions through the construction of an erosion-corrosion map, which effectively demonstrates the functional relationship between applied potential, impact angle, and oil/water content (Stack and Abdulrahman 2012) (Figure 7).

Schematic diagram showing change in mechanism of erosion corrosion for carbon steel at impact angle 15° in (a) water, (b) crude oil and (c) oil/20 % water (Stack and Abdulrahman 2012).

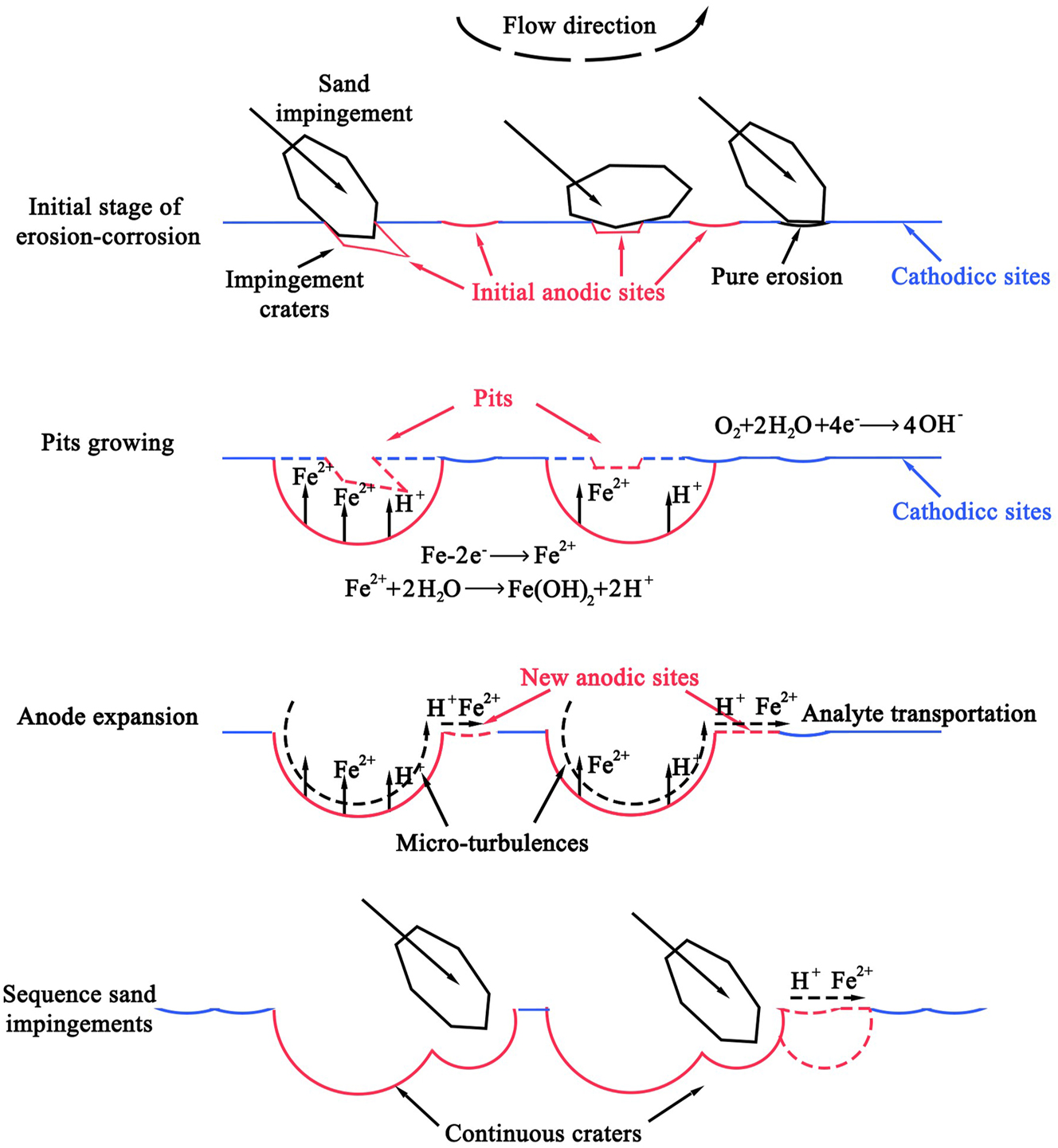

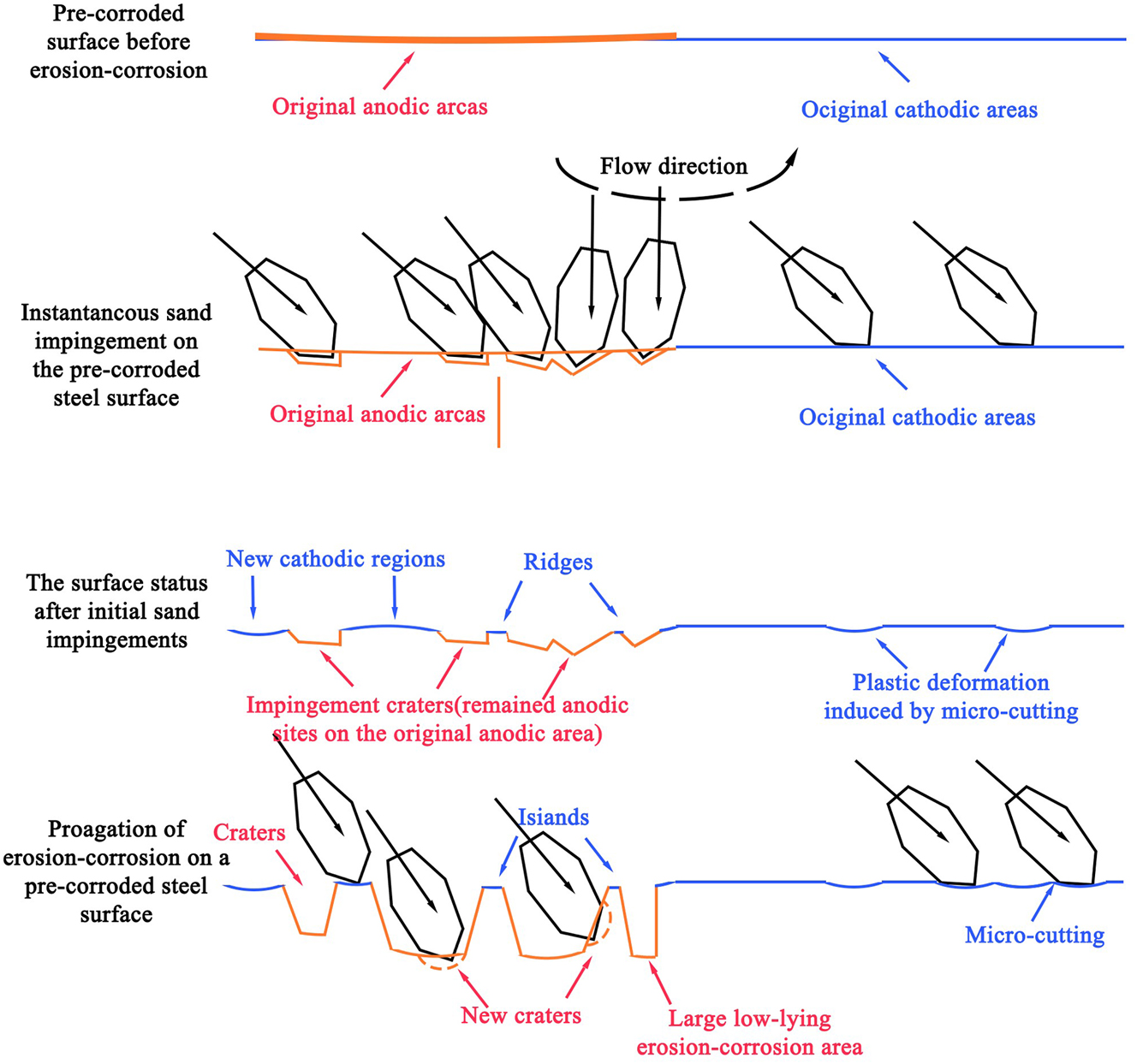

Xu et al. investigated the influence of pre-corrosion on corrosion performance of pipeline steel (Xu et al. 2020). It was found that the biggest influence of pre-corrosion on erosion corrosion is manifested in morphology. Scattered impact craters appear on the surface of finely polished steel and pre-corroded steel with removed rust layer. In an area characterized by a concentrated low-lying erosion-corrosion issue that remains untreated, one would observe closely spaced impact craters on the surface. The corrosion-erosion mechanism of a highly polished steel surface is illustrated in Figure 8, wherein the initial stage reveals the formation of random anodic points on the steel surface. As corrosion progresses, these points evolve into deeper pits that serve as nucleation sites for pitting. The initiation and dynamic process of erosion-corrosion on the pre-corroded steel surface is depicted in Figure 9. Impact from sand grains results in the formation of deep pits primarily in the original anode area, while the original cathode area experiences comparatively lesser impact. As corrosion progresses, impacts gradually extend from the anode area to encompass the cathode area. However, it remains evident that the anode area continues to be predominantly affected.

Schematic diagram of erosion-corrosion damage on the surface of finely polished steel (Xu et al. 2020).

Schematic diagram of the onset and dynamic progression of erosion-corrosion on the surface of pre-corroded steel (Xu et al. 2020).

3.4 Stress corrosion cracking

Stress corrosion cracking (SCC) (Gumerov and Khasanova 2020) uniquely causes parallel axial cracks in pipe walls. In pipeline sections with elastic bending, annular SCC cracks form due to significant longitudinal bending stresses. The outer metal surface cracks and propagates deeply, altering the metal’s structure, while the inner surface remains plastic. Pipe metal is prone to SCC because of its specific service conditions. SCC is often called environmentally assisted cracking (EAC) and has always been of major interest to gas pipeline manufacturers (Dong et al. 2009; Miyoshi et al. 1976; Park et al. 2008; Rosado et al. 2013). Some scholars (Azevedo 2007; Černý and Linhart 2004; Waanders et al. 2002) have studied the chemical gradient present in the oxide layer formed at the crack site. The composition of these oxides shows a gradual transition from metal-rich to oxygen-rich as the distance from the oxide-metal interface increases. This compositional shift emphasizes the dynamic interaction between the metal matrix and the surrounding corrosive environment during SCC. Due to fluctuations in operating pressure, the pipeline is subjected to cyclic stress loads, which can exacerbate SCC-related damage. Under such conditions, the existing cracks gradually expand and new cracks are generated at the same time. This dual mechanism of crack growth and nucleation is significantly accelerated in an environment where the pipeline is increasingly exposed to corrosive substances, highlighting the synergistic effect of mechanical stress and environmental degradation. The cumulative impact of these factors can ultimately lead to a reduction in the structural integrity of pipelines, posing a significant risk to their long-term operational reliability.

The SCC process of crack formation and propagation controlled by hydrogen is called hydrogen-induced cracking stress corrosion process, which is also called hydrogen embrittlement. Hydrogen refers to hydrogen atom, hydrogen gas, its source is that there is a small amount of hydrogen atom inside the material. Second, in the process of stress corrosion, H in the environmental medium enters the crack, or H+/H2O in the corrosive medium obtains electrons and generates hydrogen to penetrate into the matrix, accelerating crack propagation (Dwivedi and Vishwakarma 2018; Eliaz et al. 2002).

4 Corrosion prediction models

According to the corrosion mechanism, numerous scholars have developed corresponding corrosion models for the prediction of corrosion conditions. According to the prediction principle, corrosion prediction models can be divided into three categories: the theoretical analytic formula model considering the main influencing factors (Bachega Cruz et al. 2022; De Waard and Milliams 1991; Dana and Javidi 2021; Zhao et al. 2022), regression equation model based on mathematical statistics analysis (Al-Alaily et al. 2018; Gazenbiller et al. 2021; Zhu et al. 2017) and numerical calculation model based on data mining analysis (Irani M and Hajiloo 2014). Among them, the analytical formula model necessitates corrosion mechanism-based modeling, involving the selection of either empirical models, mechanistic models, or semi-empirical and semi-mechanistic models. Conducting a statistical analysis of the regression equation model entails employing mathematical and statistical techniques to ascertain its accuracy, which is contingent upon both the precision of the data utilized and the appropriate application of statistical methods. Based on the numerical calculation model of data mining analysis, this method primarily involves processing and comprehending the association rules between the data through data mining techniques. The key processing steps encompass data cleansing, data transformation, and data aggregation for summarization. Yao Yong and colleagues contend that corrosion prediction models can be categorized into two primary components: corrosion-time prediction model and corrosion-environment prediction model (Yong et al. 2023). The former primarily utilizes corrosion data at various time points to establish a predictive equation, while the latter incorporates environmental factors contributing to corrosion and integrates corrosion data for constructing a comprehensive prediction model.

The comparison of various machine learning methods is presented in Tables 5 and 6. The GirdSearchCV method was employed by Wang et al. to optimize the XGBoost model, resulting in the development of a hybrid GSCV model. Comparative analysis with other machine learning methods such as back propagation neural network (BP), support vector regression (SVR), decision tree (DT), random forest (RF), and AdaBoost revealed that the GSCV-XGBoost model exhibited superior accuracy in predicting the maximum corrosion depth of pipelines. Yang et al. employed the bagging algorithm to construct an ensemble learner by integrating multiple KNN models for predicting the internal metal corrosion behavior of oil and gas pipelines in small samples (Yang et al. 2023). The results revealed that this approach exhibited significantly lower average absolute error (MAE) compared to conventional methods such as RF.

Comparison of advantages and disadvantages of prediction models.

| Forecasting model | Features | Representative model |

|---|---|---|

| Corrosion-time prediction model | Corresponding to corrosion data at different times, but limited by environmental factors | Function model, grey theory model |

| Corrosion-environmental prediction model | Input related environmental parameters to analyze and predict corrosion, which has strong universality | Artificial neural network prediction model, dose-response function prediction model, random forest model, support vector machine, combinatorial optimization model |

Comparison of characteristics and accuracy of various machine learning methods.

| Model | Characteristics | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Weighting error samples to improve accuracy | 0.95 (Pagadala et al. 2023) 0.98 (Rezaei 2023) 0.92 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| RF | RF is based on bootstrap aggregation | 0.96 (Rezaei 2023) 0.88 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| LR | Use straight lines to describe the relationship between the variables directly (Cherkassky and Ma 2003) | 0.73 (Rezaei 2023) |

| MLR | Multiple linear regression | 0.42 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| DT | DT is less sensitive to outliers | 0.84 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| AdaBoost | AdaBoost can iteratively train a series of weak learners | 0.73 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| CatBoost | CatBoost is a gradient boosting tree algorithm designed to handle categorical features | 0.91 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| KNN | The predicted value is computed by taking the average or weighted average of the target values of the k nearest neighbors | 0.79 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| SVR | SVR is adept at capturing nonlinear relationships between the features and the target value by using kernel functions | 0.79 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

| MLP | MLP is widely used neural network architecture for supervised learning | 0.70 (Wang et al. 2024b) |

4.1 Corrosion prediction model based on theoretical analysis

4.1.1 Empirical model

The earliest proposed empirical models primarily included the Norsok M506 model, which predominantly examined the correlation between temperature, total pressure, pipe wall shear stress, pH, and corrosion rate (Zhao et al. 2022). The accuracy of this model in predicting corrosion rates is higher at high temperatures compared to low temperatures. However, it tends to overestimate pitting, localized corrosion, and other forms of uneven corrosion. Additionally, the calculation of pipe wall shear stress is based on the theory of single-phase flow, indicating that this model is more suitable for scenarios involving uniform corrosion and single-phase flow. The specific formula should be applied to the model in various application scenarios. When the temperature is greater than 300 K, the following formula should be employed:

When the temperature is 288 K use the formula:

When the temperature is 278 K use the formula:

where CRt is corrosion rate, mm/a. Kt is temperature-dependent constant. The fCO2 parameter can be expressed by the formula (12). And other symbols is defined as formula (13)–(17).

To expand the applicability of empirical models to multiphase flow scenarios, researchers have sequentially proposed the Jepson model for horizontal slug flow (Karunaratne et al. 2017), the Corpos model (Wang et al. 2022) for multiphase flow pipelines, and the Lafayette model (Luo 2023; Wu 2022) for gas-liquid two-phase flow. These findings demonstrate that the precision of empirical model projections is significantly influenced by the suitability of the experimental context and the fidelity of the data. Furthermore, they underscore the challenges associated with adapting empirical models to accommodate changes in environmental conditions and operational procedures.

4.1.2 Semi-empirical model

Semi-empirical model is a combination of empirical formulas and corrosion mechanisms to achieve a corrosion prediction model that is universally applicable to all types of environments. The initial DeWaard75 model was derived by DeWaard et al., who were the first to investigate semi-empirical models and considered the influence of CO2 partial pressure and temperature based on the carbon steel corrosion mechanism caused by CO2. However, experimental studies revealed discrepancies between predicted values and actual values. To address this issue, subsequent models proposed by DeWaard incorporated correction factors for each considered factor in order to minimize the disparity between predicted and actual values. Ultimately, the comprehensive DeWaard model accounted for pH, temperature, and CO2 partial pressure as influential factors, enabling a more accurate prediction of CO2 corrosion rate on metal surfaces. The most widely used model is the DeWaard95 model, which has the following expression:

where Vr is corrosion rate controlled by reactive activation, mm/a. Vm is corrosion rate controlled by material transfer, mm/a. T is temperature, K.

The DeWaard model, being the most renowned semi-empirical model, has served as a fundamental framework for numerous scholars in their endeavors to formulate novel CO2 corrosion models. The ECE model integrates the IFE ring flow test data with the theoretical foundation of the DeWaard model, while considering the impact of crude oil on corrosion within the model (De Waard and Milliams 1991; De Waard et al. 1995, 2001; Smith et al. 2003). This integration enhances the predictive accuracy of the model, aligning it more closely with real-world pipeline corrosion conditions. Subsequently, BP Company developed the Cassandra model by incorporating the DeWaard model and integrating the film-forming temperature into the framework (Hedges et al. 2000). Considering that a corrosion product film formed at elevated temperatures can confer certain protective properties, this model plays a pivotal role in predicting corrosion protection.

4.1.3 Mechanistic model

The mechanistic model (Nešić 2007) is a system model that integrates thermodynamic and electrochemical analyses, incorporating only a limited number of parameters obtained through rigorous comparisons with experimental data. The mechanistic model not only exhibits a strong reliance on the physical and chemical properties of the system, but also demonstrates robust capabilities for interpolation and extrapolation. However, the existing correction coefficients for mechanistic models often lack sufficient accuracy, making it challenging to ensure the mutual independence of these correction factors. Consequently, this blurs the elucidation of the reaction process within the prediction formula. Therefore, it is of great importance to establish a generalized mechanistic model applicable to corrosion prediction of oil and gas pipelines. Nešić et al. (Nešić 2007) conducted a comprehensive investigation on mechanistic model. The Nešić model (Nesic et al. 1996) incorporates various factors influencing corrosion in actual operating conditions, such as fluid velocity, composition, and temperature. The Nešić model encompasses a wide range of applications, encompassing the dynamic factors of fluids such as velocity and the composition of liquid and gas phases. This comprehensive approach is crucial for accurately predicting changes in metal corrosion rates across diverse operating conditions. Owing to its robustness and extensive applicability, the Nešić model has gained widespread adoption within the oil and gas industry, emerging as an indispensable tool for corrosion prediction in engineering practice.

4.2 Corrosion prediction model with univariate time

4.2.1 Power function model with time change

The main form of this model is:

where A is the corrosion loss of a material in the first year at a certain location, g t is the corrosion time, year. n is the protection performance of corrosion products on materials. C t is the predicted value of corrosion loss at time t.

Due to its reduced number of variables and ease of application, the model was initially preferred; however, during the experiment, it was observed that early corrosion exhibited a more rapid progression, aligning with the power function model. As the duration of corrosion increases, the subsequent corrosion model aligns more closely with a linear model, prompting some scholars to optimize the model by incorporating a power-linear approach (Panchenko and Marshakov 2016). This model is designed to align with the observed reality of corrosion loss. However, following the optimization process, it became evident that certain variables were challenging to ascertain. Furthermore, the exponential function model is more appropriate for the corrosion rate model. In the absence of appropriate cleaning and denoising of the data, the resulting model will exhibit a significant discrepancy between the predicted and actual values.

4.2.2 Grey theory model

The grey theory model is a mathematical framework capable of handling systems characterized by incomplete information and uncertainty. Given the intricate influencing factors and unpredictable effects associated with pipeline corrosion, this model aligns perfectly with its application context. Consequently, scholars have extensively employed this approach in their corrosion research endeavors. In 2007, Ma et al. employed the grey theory to forecast the extent of corrosion on the bottom of storage tanks (Ma and Wang 2007). Wang utilized the GM(1,1) model to forecast the service life of anchor steel under four distinct operating conditions (Wang et al. 2014). Yu et al. established a quality loss prediction model based on grey theory to anticipate metal quality degradation and validated its effectiveness through relative residual error calculations (Yu et al. 2017). Xie and Quan enhanced the smoothness of initial data sequences in order to optimize the GM(1,1) model for predicting the service life of 16Mn steel (Xie and Quan 2020). Liu and Zhang employed an improved GM(1,1) model to simulate corrosion changes in tank bottom plates (Liu and Zhang 2007). The grey theory model was optimized by Jin et al. through background value optimization and translation optimization techniques (Jin et al. 2023). The gray theory model exhibits low data volume requirements, yet demands higher smoothness in the data sequences. Adequate preprocessing of the data is essential when employing gray theory for analysis and prediction.

4.2.3 Markov chain model

The Markov chain is a stochastic approach that facilitates the transition to the target state (Lee et al. 2023), enabling predictions regarding subsequent corrosion conditions based on knowledge of the initial corrosion situation of the material. The utilization of Markov chain models can effectively address the challenges associated with local corrosion and pitting corrosion prediction. The research on corrosion prediction utilizing Markov chain models primarily focuses on investigating pitting states, as these models are well-suited for addressing problems involving interrelated states at different time points, which aligns with the actual situation of pitting phenomena. Andrea Brenna and colleagues employed Markov chains in a predictive model for stainless steel corrosion, utilizing the chemical composition of chlorides as an input variable (Brenna et al. 2017). The algorithm was utilized to calculate the probability of corrosion, enabling accurate assessment of the risk associated with corrosion. Zhang et al. employed Markov chains, inverse Gaussian processes, and gamma processes to simulate the progression of pipeline corrosion (Zhang and Zhou 2014). During the experimental phase, they observed a satisfactory simulation of pipeline corrosion; however, further training with larger sample sizes is necessary before practical application can be considered.

4.3 Corrosion prediction model with environmental factors as variables

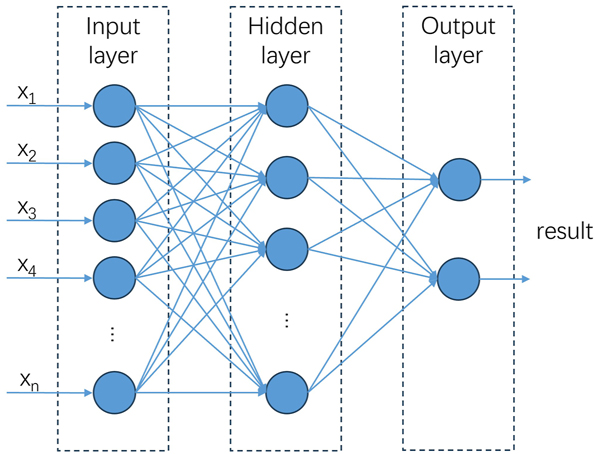

4.3.1 Artificial neural network model

Artificial neural network (ANN) is a common data mining method (Kamrunnahar and Urquidi-Macdonald 2010; Kamrunnahar and Urquidi-Macdonald 2011) (Figure 10). The algorithm possesses the capability to accomplish a nonlinear mapping process between input and output, thereby conferring it with an inherent advantage in elucidating corrosion, which is a prototypical intricate nonlinear phenomenon. Consequently, it currently stands as the most widely employed machine learning technique within the realm of corrosion modeling. Jiang et al. utilized ANN to accurately predict concrete corrosion in sewer systems (Jiang et al. 2016). After a long training period, the corrosion onset time and corrosion rate of the model were found to be very close to those measured in Australian sewers. To investigate the influence of soil heterogeneity on underground pipeline corrosion, Azoor et al. developed and validated ANN using numerical simulations to efficiently generate corrosion profiles with random realizations under various input variable configurations (Azoor et al. 2021). The findings revealed that the spatial variability of saturation significantly affects the size, depth, and occurrence frequency of the largest corrosion pits. The influencing factors of pitting corrosion in Korean steel pipes from 1998 to 2020 were investigated by Kim et al. using ANN (Kim et al. 2023). Their findings revealed the significant roles played by pipe age, soil resistivity, sulfide concentration, and water alkalinity. Given the utilization of ANN in corrosion prediction, scholars have surpassed their reliance on conventional models and are now pursuing more sophisticated and scholarly approaches. Due to the insufficiency of corrosion data and significant variations in corrosion rates across different conditions, traditional models encounter challenges in learning, leading to limited generalization performance. The corrosion rate is influenced by numerous factors, resulting in a highly intricate linear relationship that poses challenges for conventional ANN models to handle. As the inclusion of an increasing number of variables in ANN models becomes prevalent in research, the limited capabilities of traditional ANN for feature selection and extraction may pose a challenge. Consequently, scholars have enhanced the overall model performance through the integration of learning techniques. Shirazi et al. employed artificial neural networks and the imperialist competitive algorithm to successfully forecast the corrosion rate of 3C steel in seawater environments, thus validating the feasibility of this integrated approach (Zadeh Shirazi and Mohammadi 2016).

Basic neural structure of BP network (Zhang et al. 2021).

4.3.2 Dose-response function model

The ISO 9223-1992 standard, released by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in 1992, quantifies the extent of corrosion and corrosion rate across four substrates namely carbon steel, aluminum, copper, and zinc. Subsequently, numerous scholars employed prevailing corrosion theories and mechanisms to establish dose-response functions (DRF) and conducted corresponding investigations. Meanwhile, the ISO has also released the DRF functions pertaining to four categories of substrate materials. The convenience and accuracy of DRF have been acknowledged by corrosion engineers, thereby garnering increased scholarly attention. The DRF function was combined with a competitive algorithm by Panchenko et al. to assess the reliability of predicting first-year corrosion loss of structural metals in corrosive environments for various categories of atmospheric corrosion (Panchenko et al. 2020). The findings demonstrate the relatively robust performance of the DRF function in predicting values. To further assess its reliability, it is recommended to employ the MAPE index. The reliability of two rotation forest models was investigated by Gavryushina et al. in comparison to the DRF function model (Gavryushina et al. 2023). The findings demonstrated that both rotation forest models exhibited superior prediction accuracy and reliability. The limitations of the DRF function in corrosion prediction are evident, necessitating the selection of an appropriate DRF function based on the prevailing environmental conditions (Tables 7 and 8).

Dose-response functions for different atmospheric corrosion maps (Huang 2019).

| Area | Dose-response function |

|---|---|

| Swiss |

|

| Istanbul |

|

| Slovakia |

|

| Athens |

|

Dose-response function common parameter symbols.

| Name | Meaning | Unit | Name | Meaning | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | Time | a | [Cl−] | Chloride ion concentration | μg·m−3 |

| T | Temperature | °C | [NO2] | Nitrogen dioxide concentration | μg·m−3 |

| Rh | Relative humidity | % | [O3] | Ozone concentration | μg·m−3 |

| Rain | Total rainfall | mm/year | PM10 | PM concentration(<10 μm) | μg·m−3 |

| [H+] | Precipitation acidity | mg·/L | ML | Corrosion rate | g·m−2 |

| [SO2] | Sulfur dioxide concentration | μg·m−3 | R | Surface thickening | μm |

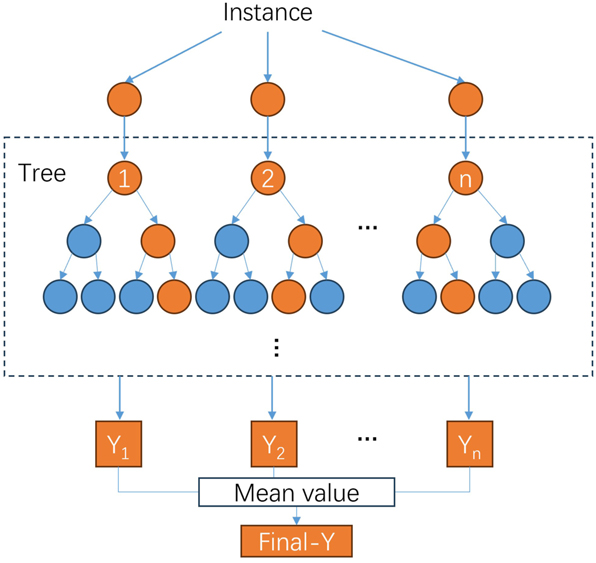

4.3.3 Random forest model

Random forest model is a data-driven ensemble learning model that uses bagging resampling technique and random feature subset to generate multiple relatively independent tree models (Figure 11). The final prediction result of RF is obtained by aggregating the predictions from all tree models for a given input sample. Although the single tree model may exhibit instability and susceptibility to overfitting when applied to small sample data, these issues can be effectively mitigated through the combination method of RF. As an integrated algorithm, RF typically possesses a greater number of layers compared to average shallow models, rendering them more adept at handling data characterized by intricate manifold structures. The advantages of RF lie in their ease of implementation, resistance to overfitting, parallelizability, convergence consistency, insensitivity to noise and lack of need for complicated parameter tuning. RF has consistently demonstrated optimal performance across multiple public datasets, making them widely employed in diverse domains. Moreover, RF can also be employed to assess the significance of variables, thereby offering researchers robust support for investigating the underlying mechanisms of the data. In recent years, RF has been employed by scholars in the field of materials and material corrosion due to their inherent advantages. Aghaaminiha et al. employed diverse algorithmic models to forecast the corrosion rate of carbon steel in the presence of corrosion inhibitors (Aghaaminiha et al. 2021). It is found that the random forest algorithm could achieve the most accurate prediction, with the mean square error ranging from 0.005 to 0.093. Pei et al. employed Cu/Fe sensors to monitor the atmospheric corrosion of carbon steel and utilized a random forest model for predicting the atmospheric corrosion rate of carbon steel (Pei et al. 2020). The findings demonstrated that the RF algorithm outperformed both the support vector machine model and the ANN model in terms of accuracy.

RFR structure (Xinsheng Zhang 2021).

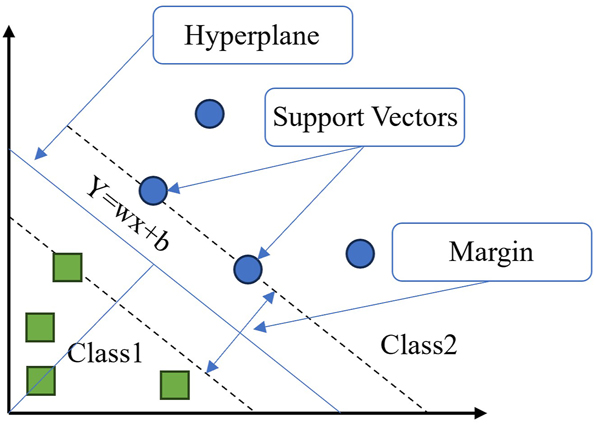

4.3.4 Support vector machine

Support vector machine (SVM) is a type of supervised learning model commonly employed for classification and regression analysis in the field of machine learning (Figure 12). The advantages of this method encompass excellent performance in high-dimensional spaces, the capability to handle small sample sets proficiently, and the ability to effectively address nonlinear problems through the application of kernel functions. SVM can be used to select and extract features that are important for corrosion prediction, as well as to categorize different levels of corrosion states. Jimenez-Come et al. proposed a hybrid SVM-based algorithm for the automatic prediction of pitting behavior in EN 1.4404, aiming to establish a robust model for this purpose (Jiménez‐Come et al. 2018). The study highlighted that the breakdown potential emerges as the primary variable in pitting modeling, while temperature assumes utmost significance in modeling the breakdown potential. The support vector regression-principal component analysis-chaotic particle swarm method proposed by Peng et al. was employed to optimize corrosion prediction models (Peng et al. 2021). The proposed approach is based on the support vector machine model and enhances prediction accuracy through the utilization of chaotic particle swarm optimization. Moreover, it has been observed that this method effectively enhances both the accuracy and interpretability of the model. It has also been argued that the prediction curves of SVM models differ somewhat from the experimental data due to the consistent and smooth input eigenspace transformations of the kernel program (kernel) used in the SVM models (Pagadala et al. 2023).

Schematic diagram of support vector machine (Xu 2023).

5 Summary and outlook

This study analyzes the hot spots in the field of pipeline corrosion prediction. It is found that carbon steel-based pipelines have been the primary focus of research, with particular emphasis on investigating their lifespan. The predominant research approach involves conducting accelerated corrosion experiments to observe both metal corrosion fatigue and corrosion behavior. In this paper, the mechanism of pipeline corrosion is reviewed, and the types of pipeline corrosion failure are summarized. During the investigation of metal corrosion prediction methods, it becomes evident that experience and mechanism-based corrosion prediction models often exhibit limited applicability and necessitate modifications to align with specific working conditions. In subsequent major corrosion prediction methods, the predominant approach is data-driven and relies on algorithms. However, a common challenge encountered is the limited size of training samples, resulting in inadequate predictive accuracy of the model. The phenomenon of corrosion is influenced by multiple factors, and the relationships between these variables exhibit non-linear characteristics. Existing predictive methods lack sufficient capability to address non-linear problems, resulting in limited model interpretability and hindering optimization of the corrosion model. ANN and RF are the primary tools employed in predictive modeling, and their utilization is expected to increase significantly within the corrosion domain in forthcoming years. In the case that the service environment is complex and changeable, which cannot be fully detected and covered, the model is still a relatively economical method to predict corrosion. Furthermore, corrosion prediction will emerge as a prominent research area, offering enhanced strategies for pipeline operation.

Funding source: Annual University Student Research and Innovation Program Project

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2023-A-071

Funding source: Project for Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program

Award Identifier / Grant number: 202310340038

Funding source: Open Research Fund of Henan Key Laboratory of Infrastructure corrosion and protection

Award Identifier / Grant number: HNICP202405

Funding source: General Research Project of the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education

Award Identifier / Grant number: Y202353929

Acknowledgments

This paper acknowledges the support provided by the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education, Zhejiang Ocean University, and the Henan Key Laboratory of Infrastructure corrosion and protection.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: General Research Project of the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education [Grant no. Y202353929]; Annual University Student Research and Innovation Program Project [Grant no. 2023-A-071]; Project for Undergraduate Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program [Grant no. 202310340038]; Open Research Fund of Henan Key Laboratory of Infrastructure corrosion and protection [Grant no. HNICP202405].

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Aamo, O.M. (2016). Leak detection, size estimation and localization in pipe flows. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 61: 246–251, https://doi.org/10.1109/tac.2015.2434031.Search in Google Scholar

Aghaaminiha, M., Mehrani, R., Colahan, M., Brown, B., Singer, M., Nesic, S., Vargas, S.M., and Sharma, S. (2021). Machine learning modeling of time-dependent corrosion rates of carbon steel in presence of corrosion inhibitors. Corros. Sci. 193: 109904, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2021.109904.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Alaily, H.S., Hassan, A.A.A., and Hussein, A.A. (2018). Use of extended finite element method and statistical analysis for modelling the corrosion-induced cracking in reinforced concrete containing metakaolin. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 45: 167–178, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjce-2017-0298.Search in Google Scholar

American Society for Testing and Materials (1995). Standard guide for estimating the atmospheric corrosion resistance of low alloy steels. (ASTM G101-1995).Search in Google Scholar

Azevedo, C.R. (2007). Failure analysis of a crude oil pipeline. Eng. Fail. Anal. 14: 978–994, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2006.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

Azoor, R., Deo, R., Shannon, B., Fu, G., Ji, J., and Kodikara, J. (2021). Predicting pipeline corrosion in heterogeneous soils using numerical modelling and artificial neural networks. Acta Geotech. 17: 1463–1476, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-021-01385-5.Search in Google Scholar

Bachega Cruz, J.P., Veruz, E.G., Aoki, I.V., Schleder, A.M., De Souza, G.F.M., Vaz, G.L., De Barros, L.O., Orlowski, R.T.C., and Martins, M.R. (2022). Uniform corrosion assessment in oil and gas pipelines using corrosion prediction models – Part 1: models performance and limitations for operational field cases. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 167: 500–515, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2022.09.034.Search in Google Scholar

Brenna, A., Bolzoni, F., Lazzari, L., and Ormellese, M. (2017). Predicting the risk of pitting corrosion initiation of stainless steels using a Markov chain model. Mater. Corros. 69: 348–357, https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.201709753.Search in Google Scholar

Černý, I. and Linhart, V. (2004). An evaluation of the resistance of pipeline steels to initiation and early growth of stress corrosion cracks. Eng. Fract. Mech. 71: 913–921, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-7944(03)00011-0.Search in Google Scholar

Changfeng Chen, M.L., Zhao, G., Bai, Z., Yan, M., and Yang, Y. (2003). The EIS analysis of cathodic reactions during CO2 corrosion of N80 steel. Acta Metall. Sin.: 94–98.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, Y., Chen, C., Liu, Z., Hu, Z., and Wang, X. (2015). The methodology function of CiteSpace mapping knowledge domains. Stud. Sci. Sci. 33: 242–253.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, C. (2005). CiteSpace II: detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 57: 359–377, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317.Search in Google Scholar

Cherkassky, V. and Ma, Y. (2003). Comparison of model selection for regression. Neural Comput. 15: 1691–1714, https://doi.org/10.1162/089976603321891864.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Dana, M.M. and Javidi, M. (2021). Corrosion simulation via coupling computational fluid dynamics and NORSOK CO2 corrosion rate prediction model for an outlet header piping of an air-cooled heat exchanger. Eng. Fail. Anal. 122: 105285, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2021.105285.Search in Google Scholar

De Waard, C., L.U. and Milliams, D.E. (1991). Predictive model for CO2 corrosion engineering in wet natural gas pipelines. Corrosion 47: 976–985, https://doi.org/10.5006/1.3585212.Search in Google Scholar

De Waard, C. and Lotz, U. (1995). Prediction of CO2 corrosion of carbon steel. NACE International, Houston USA.Search in Google Scholar

De Waard, C., Lotz, U., and Dugstad, A. (1995). Influence of liquid flow velocity on CO2 corrosion: a semi-empirical model. NACE International, Houston, TX (United States).10.5006/C1995-95128Search in Google Scholar

De Waard, C., Smith, L., Bartlett, P., Cunningham, H., and Italy. (2001). Modelling corrosion rates in oil production tubing. Eurocorr: Riva del Garda 254.Search in Google Scholar

Dong, C.F., Li, X.G., Liu, Z.Y., and Zhang, Y.R. (2009). Hydrogen-induced cracking and healing behaviour of X70 steel. J. Alloys Compd. 484: 966–972, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.05.085.Search in Google Scholar

Dwivedi, S.K. and Vishwakarma, M. (2018). Hydrogen embrittlement in different materials: a review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43: 21603–21616, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.09.201.Search in Google Scholar

Eliaz, N., Shachar, A., Tal, B., and Eliezer, D. (2002). Characteristics of hydrogen embrittlement, stress corrosion cracking and tempered martensite embrittlement in high-strength steels. Eng. Fail. Anal. 9: 167–184, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1350-6307(01)00009-7.Search in Google Scholar

Farhadian, A., Zhao, Y., Naeiji, P., Rahimi, A., Berisha, A., Zhang, L., Rizi, Z.T., Iravani, D., and Zhao, J. (2023). Simultaneous inhibition of natural gas hydrate formation and CO2/H2S corrosion for flow assurance inside the oil and gas pipelines. Energy 269: 126797, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2023.126797.Search in Google Scholar

Gavryushina, M.A., Marshakov, A.I., and Panchenko, Y.M. (2023). Application of the random forest algorithm of corrosion losses of aluminum for the first year of exposure in various regions of the world. Protect. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 59: 85–95, https://doi.org/10.1134/s2070205123700259.Search in Google Scholar

Gazenbiller, E., Arya, V., Reitz, R., Engler, T., Oechsner, M., and Höche, D. (2021). Statistical analysis of AA-1050 localized corrosion in anhydrous ethanol. Corros. Sci. 179: 109137, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.109137.Search in Google Scholar

Gumerov, A.K. and Khasanova, A.R. (2020). Stress corrosion cracking in pipelines. IOP Conf. Series: Mater. Sci. Eng. 952, https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/952/1/012046.Search in Google Scholar

Guzenkova, A.S., Artamonova, I.V., Guzenkov, S.A., and Ivanov, S.S. (2021). Steel corrosion in hydrogen sulfide containing oil field model media. Metallurgist 65: 517–521, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11015-021-01185-y.Search in Google Scholar

Hedges, B., Paisley, D., and Woollam, R.C. (2000). The corrosion inhibitor availability model. NACE Corrosion, Orlando.10.5006/C2000-00034Search in Google Scholar

Hou, B., Li, X., Ma, X., Du, C., Zhang, D., Zheng, M., Xu, W., Lu, D., and Ma, F. (2017). The cost of corrosion in China. Npj Mater. Degrad. 1: 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-017-0005-2.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, Y., Guo, P., Yao, Z., Wang, Z., and Sanni, O. (2017). Corrosion behavior of drill pipe steel in CO2-H2S environment. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 12: 6705–6713, https://doi.org/10.20964/2017.07.81.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, X., Zhou, L., Li, Y., Du, Z., Zhu, Q., and Han, Z. (2023). The synergistic effect of temperature, H2S/CO2 partial pressure and stress toward corrosion of X80 pipeline steel. Eng. Fail. Anal. 146: 107079, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107079.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, J. (2019). Mapping the atmospheric corrosion level of southern power grid. Establishment of dose-response function and optimization of mapping method, Master Degree. South China University of Technology, Shenzhen.Search in Google Scholar

Hussain, M., Zhang, T., Chaudhry, M., Jamil, I., Kausar, S., and Hussain, I. (2024). Review of prediction of stress corrosion cracking in gas pipelines using machine learning. Machines 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/machines12010042.Search in Google Scholar

Irani M, C.R. and Hajiloo, M. (2014). Application of data mining techniques in building predictive models for oil and gas problems: a case study on casing corrosion prediction. Int. J. Oil, Gas and Coal Technol. 8: 369, https://doi.org/10.1504/ijogct.2014.066304.Search in Google Scholar

Jiang, G., Keller, J., Bond, P.L., and Yuan, Z. (2016). Predicting concrete corrosion of sewers using artificial neural network. Water Res. 92: 52–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.01.029.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Jiménez-Come, M.J., De La Luz Martín, M., and Matres, V. (2018). A support vector machine-based ensemble algorithm for pitting corrosion modeling of EN 1.4404 stainless steel in sodium chloride solutions. Mater. Corros. 70: 19–27, https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.201810367.Search in Google Scholar

Jin, W.B., Xiong, X.W., Fan, C.Y., and Kong, X.W. (2023). Corrosion depth prediction of pipeline based on improved gray model. Pet. Sci. Technol. 41: 802–817, https://doi.org/10.1080/10916466.2022.2069120.Search in Google Scholar

Kamrunnahar, M. and Urquidi-Macdonald, M.J.C.S. (2010). Prediction of corrosion behavior using neural network as a data mining tool. Corros. Sci. 52: 669–677, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2009.10.024.Search in Google Scholar

Kamrunnahar, M. and Urquidi-Macdonald, M. (2011). Prediction of corrosion behaviour of alloy 22 using neural network as a data mining tool. Corros. Sci. 53: 961–967, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2010.11.028.Search in Google Scholar

Karunaratne, M.S.A., Jepson, M.A.E., Simms, N.J., Nicholls, J.R., and Thomson, R.C. (2017). Modelling of microstructural evolution in multi-layered overlay coatings. J. Mater. Sci. 52: 12279–12294, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-017-1365-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Kim, K., Kang, H., Kim, T., Iseley, D.T., Choi, J., and Koo, J. (2023). Influencing factors analysis for drinking water steel pipe pitting corrosion using artificial neural network. Urban Water J. 20: 550–563, https://doi.org/10.1080/1573062x.2023.2198996.Search in Google Scholar

Larrabee, C. and Coburn, S. (1961). Experience with blast-furnace slag as an aggregate in reinforced concrete. Corrosion 17: 155t–156t.10.5006/0010-9312-17.4.79Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J., Jeon, C.-H., Shim, C.-S., and Lee, Y.-J. (2023). Bayesian inference of pit corrosion in prestressing strands using Markov chain Monte Carlo method. Probab. Eng. Mech. 74: 103512, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.probengmech.2023.103512.Search in Google Scholar

Legault, R. and Leckie, H.P. (1974). Effect of alloy composition on the atmospheric corrosion behavior of steels based on a statistical analysis of the Larrabee-Coburn data set. In: Corrosion in Natural Environments. ASTM International, West Conshohocken.10.1520/STP32171SSearch in Google Scholar

Li Chunfu, W.B., Zhang, Y., and Pingya, L. (2004). Research progress of co2 corrosion in oil/gas field exploitation. J. SW. Pet. Inst.: 42–46+87.Search in Google Scholar

Li, X.G., Zhang, D.W., Liu, Z.Y., Li, Z., Du, C.W., and Dong, C.F. (2015). Materials science: share corrosion data. Nature 527: 441–442, https://doi.org/10.1038/527441a.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Liu, S.M. and Zhang, G.Y. (2007). An improved grey model for corrosion prediction of tank bottom. Prot. Met. 43: 407–412, https://doi.org/10.1134/s0033173207040157.Search in Google Scholar

Lohodny-Sarc, O. (1994). Corrosion inhibition in oil and gas drilling and production operations. IOM, CI (UK) 1994: 104–120.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, B.T., Luo, J.L., Guo, H.X., and Mao, L.C. (2011). Erosion-enhanced corrosion of carbon steel at passive state. Corros. Sci. 53: 432–440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2010.09.054.Search in Google Scholar

Luo, W. (2023). Research on metal pipeline corrosion early warning by integrating knowledge graph and neural network, Master Degree. Xi’an Shiyou University, Xi’an.Search in Google Scholar

Ma, F.Y. and Wang, W.H. (2007). Prediction of pitting corrosion behavior for stainless SUS 630 based on grey system theory. Mater. Lett. 61: 998–1001, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2006.06.053.Search in Google Scholar

Ma, H.A., Zhang, W.D., Wang, Y., Ai, Y.B., and Zheng, W.Y. (2023). Advances in corrosion growth modeling for oil and gas pipelines: a review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 171: 71–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2022.12.054.Search in Google Scholar

Mcintire, G., Lippert, J., and Yudelson, J. (1990). The effect of dissolved CO2 and O2 on the corrosion rate of iron. Corrosion 46: 91–95, https://doi.org/10.5006/1.3585085.Search in Google Scholar

Miyoshi, E., Tanaka, T., Terasaki, F., and Ikeda, A. (1976). Hydrogen-induced cracking of steels under wet hydrogen sulfide environment. J. Eng. Ind. 98: 1221–1230, https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3439090.Search in Google Scholar

National Association of Corrosion Engineers (2006). NACE medium according to Standard TM 0177.Search in Google Scholar

Nesic, S., Postlethwaite, J., and Olsen, S. (1996). An electrochemical model for prediction of corrosion of mild steel in aqueous carbon dioxide solutions. Corrosion 52: 280–294, https://doi.org/10.5006/1.3293640.Search in Google Scholar

Nešić, S. (2007). Key issues related to modelling of internal corrosion of oil and gas pipelines – a review. Corros. Sci. 49: 4308–4338, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2007.06.006.Search in Google Scholar

Nowell, A.R.M., Hollister, C.D., and Jumars, P.A. (1982). High energy benthic boundary layer experiment: HEBBLE. Eos, Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 63: 594–595, https://doi.org/10.1029/eo063i031p00594.Search in Google Scholar

Pagadala, N.D., Jaiswal, J., and R, R. (2023). Machine learning based corrosion prediction of as cast Mg-Sn alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Today Commun. 35: 106108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106108.Search in Google Scholar

Panchenko, Y.M. and Marshakov, A.I. (2016). Long-term prediction of metal corrosion losses in atmosphere using a power-linear function. Corros. Sci. 109: 217–229, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2016.04.002.Search in Google Scholar

Panchenko, Y.M., Marshakov, A.I., Nikolaeva, L.A., and Igonin, T.N. (2020). Evaluating the reliability of predictions of first-year corrosion losses of structural metals calculated using dose-response functions for territories with different categories of atmospheric corrosion aggressiveness. Protect. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 56: 1249–1263, https://doi.org/10.1134/s207020512007014x.Search in Google Scholar

Papavinasam, S. (2014). Corrosion control in the oil and gas industry. Gulf Professional Publishing, Burlington.10.1016/B978-0-12-397022-0.00002-9Search in Google Scholar

Park, G.T., Koh, S.U., Jung, H.G., and Kim, K.Y. (2008). Effect of microstructure on the hydrogen trapping efficiency and hydrogen induced cracking of linepipe steel. Corros. Sci. 50: 1865–1871, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2008.03.007.Search in Google Scholar

Pei, Z., Zhang, D., Zhi, Y., Yang, T., Jin, L., Fu, D., Cheng, X., Terryn, H.A., Mol, J.M.C., and Li, X. (2020). Towards understanding and prediction of atmospheric corrosion of an Fe/Cu corrosion sensor via machine learning. Corros. Sci. 170: 108697, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2020.108697.Search in Google Scholar

Peng, S., Zhang, Z., Liu, E., Liu, W., and Qiao, W. (2021). A new hybrid algorithm model for prediction of internal corrosion rate of multiphase pipeline. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 85: 103716, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2020.103716.Search in Google Scholar

Pessu, F., Barker, R., and Neville, A. (2020). CO2 corrosion of carbon steel: the synergy of chloride ion concentration and temperature on metal penetration. Corrosion 76, https://doi.org/10.5006/3583.Search in Google Scholar

Qin, M., Liao, K., He, G., Zou, Q., Zhao, S., and Zhang, S. (2022). Corrosion mechanism of X65 steel exposed to H2S/CO2 brine and H2S/CO2 vapor corrosion environments. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 106, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2022.104774.Search in Google Scholar

Ren, L., Jiang, T., Jia, Z.-G., Li, D.-S., Yuan, C.-L., and Li, H.-N. (2018). Pipeline corrosion and leakage monitoring based on the distributed optical fiber sensing technology. Measurement 122: 57–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.measurement.2018.03.018.Search in Google Scholar

Rezaei, A. (2023). Prediction of hot corrosion behavior of Inconel 617 via machine learning. Anti-Corros. Methods and Mater. 71: 38–46, https://doi.org/10.1108/acmm-07-2023-2854.Search in Google Scholar

Rosado, D.B., Waele, W.D., Vanderschueren, D., and Hertelé, S. (2013). Latest developments in mechanical properties and metallurgical features of high strength line pipe steels. Int. J. Sustain. Construct. Des. 4: 1–10, https://doi.org/10.21825/scad.v4i1.742.Search in Google Scholar

Shahali, H., Ghasemi, H.M., and Abedini, M. (2019). Contributions of corrosion and erosion in the erosion-corrosion of Sanicro28. Mater. Chem. Phys. 233: 366–377, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.05.051.Search in Google Scholar

Shivananju, B.N., Kiran, M., Nithin, S.P., Vidya, M.J., and Asokan, S. (2013). Real time monitoring of petroleum leakage detection using etched fiber Bragg grating. Int. Conf. Opt. Precis. Eng. Nanotechnol.: 548–552.10.1117/12.2021077Search in Google Scholar