Abstract

High temperature molten salt corrosion is of utmost importance for selecting and qualifying structural materials for critical applications. Pyrochemical reprocessing of spent metallic fuels of the future fast breeder reactors in India is widely considered. One of the main processes of pyrochemical reprocessing is electrorefining. Electrorefining is generally conducted in LiCl–KCl molten salt at 500–600 °C under an inert atmosphere. Research groups worldwide are involved in developing corrosion resistant materials and investigating the corrosion behaviour of various structural materials for LiCl–KCl applications under different environments. A wide variety of materials, including metals, alloys, intermetallics, single crystals, glass and ceramics, have been investigated in molten LiCl–KCl salt. This review focuses mainly on the corrosion assessment of materials for LiCl–KCl application; a complete literature review with emphasis on the corrosion issues of materials is provided. This paper reviews the corrosion issues of metals and alloys in molten salts and the selection criteria of corrosion-resistant materials for molten salts. Understanding the molten salt corrosion mechanisms and future research scope are also discussed.

1 Molten salts for nuclear power

Nuclear power generation has increased worldwide from its inception, and presently, nuclear power has a share of around 10% of the world’s electricity (WNA October 2021a). Nuclear energy plays a significant role in reducing carbon emissions and adds to the green environment. In 2020, nuclear reactors helped in reducing two billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, which would have been released into the environment by coal fired power stations (WNA October 2021b). In India, a three-stage nuclear power programme was envisaged by Dr. Homi J. Bhabha (Banerjee and Gupta 2017). Presently, India is in the second stage of the nuclear power programme. The second stage includes the Fast breeder reactors to produce more electricity and ensure the availability of fuel for sustaining nuclear power generation for extended periods (Rodriguez and Bhoje 1998; Raj et al. 2002). Reprocessing the once burnt fuel (spent fuel) is vital in a nuclear power programme. The first stage of the nuclear power programme uses natural uranium oxide as fuel. The reprocessing of the fuel is carried out by an aqueous reprocessing route known as PUREX process (Ramanujam 2001). The future Fast breeder reactors using metallic fuels to gain more advantages over oxide fuels are being explored. The spent metallic fuels from the future Fast breeder reactors would be reprocessed through non-aqueous reprocessing known as pyrochemical reprocessing. In pyrochemical reprocessing, molten salts are the driving media for separating fuel elements from the spent fuel (Ackerman 1991).

Molten salts are also used in the molten salt based nuclear power reactors (Serp et al. 2014). Molten salt based reactors were investigated in the early 1960s. Molten salt reactors uses mostly molten fluoride salts as the coolants. Presently, the concept of molten salt reactors mainly focuses on the presence of fuel in the form of dissolved fuel in molten salts and reprocessing the spent fuel online. It is also aimed to use the thorium as fuel along with U and Pu. Due to their inherent advantages, GEN IV molten salt-based reactors are being extensively investigated in the nuclear power programme globally.

2 Pyrochemical reprocessing and choice of materials

After its targeted burn-up in the reactor, the nuclear fuel needs to be replaced with the fresh fuel to maintain the nuclear fission reaction and then power generation. The once burnt fuel is known as spent nuclear fuel. The spent nuclear fuel contains several elements, rare earths, noble metals, actinides, noble gases, other than the fuel elements formed during the process of nuclear fission and its composition depends on the extent of burn-up. The reprocessing of the spent nuclear fuel to recover the useful fissile inventory is a key step in a closed fuel cycle. The reprocessing of the oxide-based spent nuclear fuel is carried out by the aqueous reprocessing route, the PUREX process. However, India’s future fast breeder reactors are expected to use metallic fuels due to added advantages over the oxide fuels (Nagarajan et al. 2008).

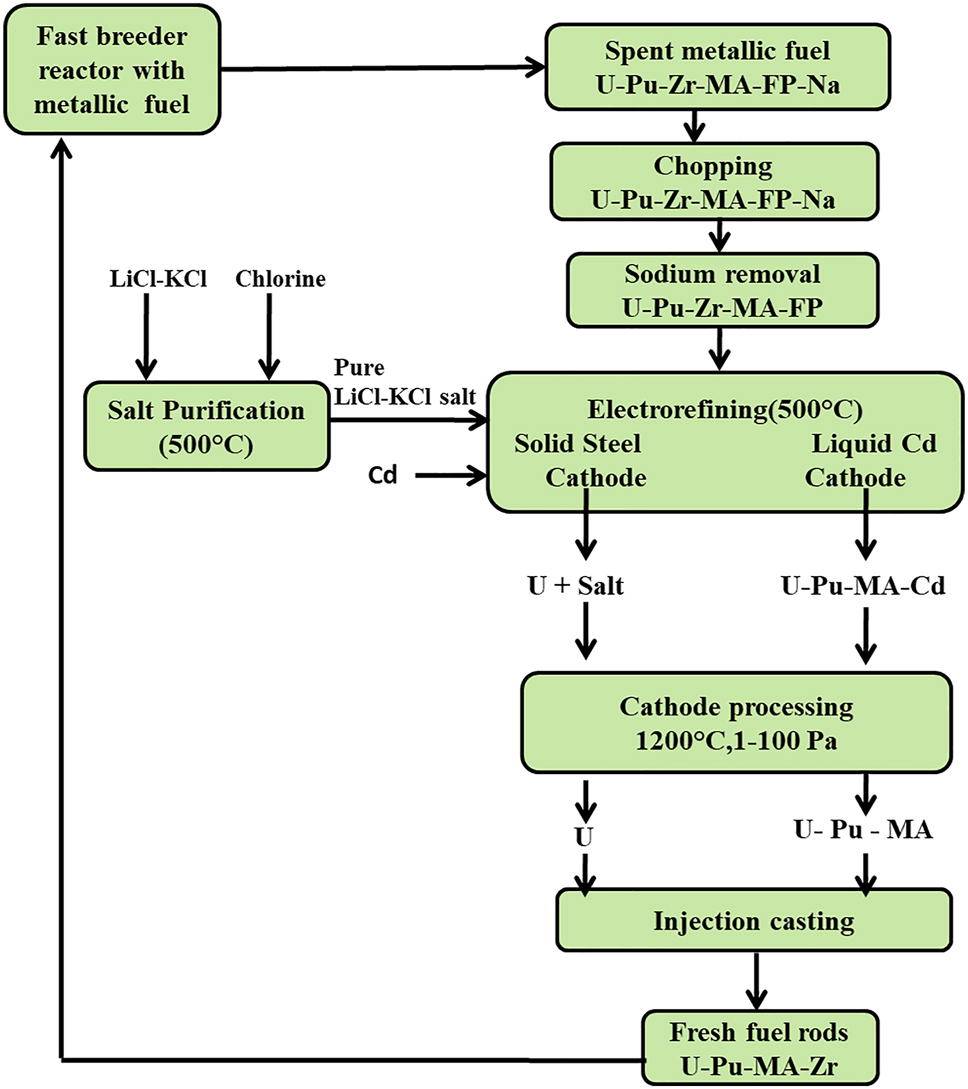

A non-aqueous reprocessing route known as pyrochemical reprocessing is being developed simultaneously to reprocess the spent metallic fuels from the future fast breeder reactors. The pyrochemical separation of the useful fuel elements from the spent nuclear fuel is based on the differences in the chemical stabilities of the respective elements chlorides in the LiCl–KCl eutectic salt medium. The pyrochemical reprocessing involves major unit operations such as salt purification, electrorefining, cathode processing and injection casting, as shown in the schematic (Figure 1). The pyrochemical reprocessing is carried out in hot cells due to the radiation of the spent metallic fuel (OECD-NEA 2004).

Schematic of the major unit operations of the proposed pyrochemical reprocessing of the spent metallic fuels from future fast breeder reactors in India.

The salt purification and electrorefining steps uses the molten eutectic LiCl–KCl salt (44.5:55.5 wt% or 58.5:41.5 mol%). Usually, the eutectic LiCl–KCl salt is purified initially by vacuum drying followed by treatment with Cl2 gas (chlorination). Chlorination is performed by passing chlorine gas over LiCl–KCl salt at 500 °C for about an hour or more based on the quantity of the salt. After the chlorination, the salt was cooled down while purging with argon gas, and the solidified salt molds are stored in the glove boxes. This purified salt is used for the next process step, electrorefining (Nagarajan et al. 2011).

The electrorefining step consists of two cathodes, one solid steel cathode and the other liquid Cd cathode, LiCl–KCl eutectic salt with 5–6 wt% UCl3 as the electrolyte and perforated steel anode basket containing cut pieces of the spent metallic fuel. The complete electrorefining process is carried out in an inert gas atmosphere, especially in an ultra-high pure argon gas atmosphere. The useful fuel elements, U and Pu are separated in this process. Uranium is deposited on the solid cathode, and uranium and plutonium together are deposited on the liquid Cd cathode. The separation of these fuel elements from the rest of the fission product elements occurs mainly due to the variation in the stabilities of the respective element chlorides in the eutectic LiCl–KCl melt (Ackerman 1991).

The obtained cathode deposits from the electrorefining process are further processed to obtain the pure metallic products in a process step called cathode processing. The cathode deposit obtained contains LiCl–KCl–UCl3 salt entrapped in the uranium deposit, which must be removed. The occluded salt and Cd are removed during cathode processing by distillation. The cathode process’s operating temperatures are around 1000–1200 °C. After removing the salt and Cd, the metallic product, mainly U or U and Pu, is further processed to obtain fuel rods for the reactor, namely by Injection casting. In this process, the obtained metallic product will be adjusted for the required fuel composition by adding a sufficient amount of U or Pu freshly and then melted in an induction melting furnace. Once the fuel is in molten state, capillaries will be used to suck the melt into the capillaries to obtain the fuel in the form of fuel rods (IAEA 2021).

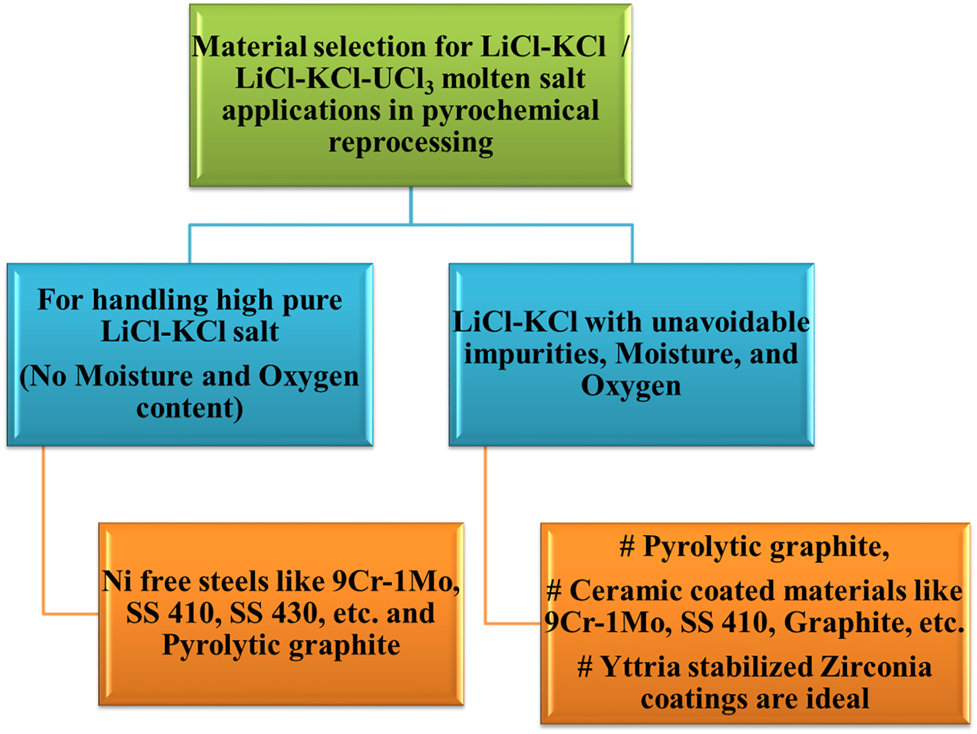

The various materials have been used and proposed for the different unit operations of the pyrochemical reprocessing of metallic fuels. The pyrochemical reprocessing is a batch process, and considering the long term service of these materials without failure for several batch processes, the materials need to be selected cautiously considering the highly radioactive environment. The unit operations, their process environments, probable structural materials and their anticipated corrosion problems are listed in Table 1. Pyrolytic graphite crucibles or YSZ coated high density graphite or alloys are preferred for molten salt applications. For the cathode processing and injection casting processes, yttria coated graphite crucibles with suitable high temperature bond coats are ideal.

Structural materials for the pyrochemical reprocessing of metallic fuel and anticipated corrosion issues.

| Components of main unit operations of pyrochemical process | Process environment | Probable structural material | Anticipated corrosion issues | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salt preparation vessel | LiCl–KCl molten salt, 500 °C, Cl2 gas with moisture and O2 impurities | Pyrolytic graphite (PyG), graphitic materials or alloys with ceramic coatings like yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) are preferred | General molten salt corrosion of alloys and graphite materials except PyG | Kamachi Mudali et al. (2011), Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2022) |

| Electrorefining vessel | LiCl–KCl molten salt, spent metallic fuel containing fission products, U, Zr, Pu, minor actinides, etc. and Cd. 500–600 °C, argon gas | 2.25Cr–1Mo and 9Cr–1Mo are attempted. However, 2.25Cr–1Mo, 9Cr–1Mo and Ni based alloys showed severe dissolution in molten salts. Ceramics mostly YSZ coated graphite or alloys are preferred | General molten salt corrosion, corrosion related to liquid Cd | Kamachi Mudali et al. (2011, 2013, Jagadeesh et al. (2012b), Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2015, 2022, 2017a), Ravi Shankar et al. (2008, 2013b) |

| Cathode process crucible | Metals like U, Pu, U–Zr, U–Pu–Zr etc. based on type of metallic fuel, Cd, LiCl–KCl molten salt, 800–1500 °C, under vacuum | Mostly ceramic coated graphite crucibles. Yttria coating on graphite with proper bond coat is preferred | Coating delamination, reaction of the molten fuel (U or U–Zr, U–Pu–Zr) with the structural material leading to contamination of the fuel | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2020) |

| Injection casting crucible | Metals like U, Pu, alloys U–Zr, U–Pu–Zr etc. 1300–1500 °C, argon gas | Mostly ceramic coated graphite crucibles. Yttria coating on graphite with proper bond coat is preferred | Coating delamination, reaction of the molten fuel (U or U–Zr, U–Pu–Zr) with the structural material leading to contamination of the fuel | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2020) |

The electrorefiner vessel in the integral fast reactor (IFR) metallic fuel reprocessing is made up of low-carbon steel (Burris et al. 1986). Various coatings like alumina, zirconia, yttria, magnesia, HfN, TiC, ZrC, aluminium titanate have been evaluated for the uranium melting applications (Cho et al. 2011; Fredrickson et al. 2022; Holcombe and Powell 1973; Kim et al. 2011; Koger and Banker 1976; de Vasconcelos et al. 2004; Westphal et al. 2008). The authors recently reviewed the ceramic coatings developed and used for high temperature uranium melting applications (Jagadeeswara Rao et al. 2020). The present review focuses on the corrosion issues related to salt purification and electrorefining processes.

As the process of salt purification is carried out at high temperature and in a highly aggressive Cl2 gas environment, moisture, oxygen and other impurities, structural material’s corrosion occurs and this needs to be addressed. The electrorefining process is also a high temperature process where molten LiCl–KCl salt under an argon atmosphere is used. So the structural materials should be capable of holding the melt under these conditions without much corrosion of the materials. Even though the process is carried out under an inert atmosphere or in inert atmosphere glove boxes, a trace amount of moisture or oxygen either in the salt or in the gaseous atmosphere can get ingress. This can lead to the corrosion of the materials containing the molten salt. So it is essential to study the corrosion of various structural materials for their application as containers for the salt purification and electrorefining processes.

3 Purification of LiCl–KCl molten salt

Molten LiCl–KCl salt has been chosen for the electrorefining process for the separation of various fuel elements and other fission products from the spent metallic fuel because of the following properties (Ackerman 1991). The molten LiCl–KCl eutectic salt possesses good thermal stability, high conductivity, low viscosity at high temperatures, wide electrochemical window (better electrochemical stability), low eutectic temperature and of course, the salt is commercially available at a reasonable price (Ackerman 1991; IAEA 2021). However, the electrochemical stability or the electrochemical window of the eutectic salt changes drastically with the purity of the eutectic mixture. The corrosion of the structural materials exposed to molten LiCl–KCl salt is also greatly affected by the purity of the salt. Since LiCl is more deliquescent, preparing a pure LiCl–KCl eutectic mixture is difficult. So it is essential to take utmost care while preparing the eutectic mixture or the hydrolytic decomposition of the salt occurs as the rise in temperature, which further leads to the loss of HCl gas from the system leaving behind the alkali impurities in the eutectic salt (Laitinen et al. 1957).

If the molten salt contains moisture (H2O), upon heating/fusion, it reacts with the chloride ions and produces hydroxide ions, as given in equation (1). The formed hydroxide ions can further react with the metal ions and precipitate them; and also hydroxide ions are reduced early than alkali metal ions, Li+ or K+, and ultimately, the electrochemical window of the melt decreases (Swain et al. 2020).

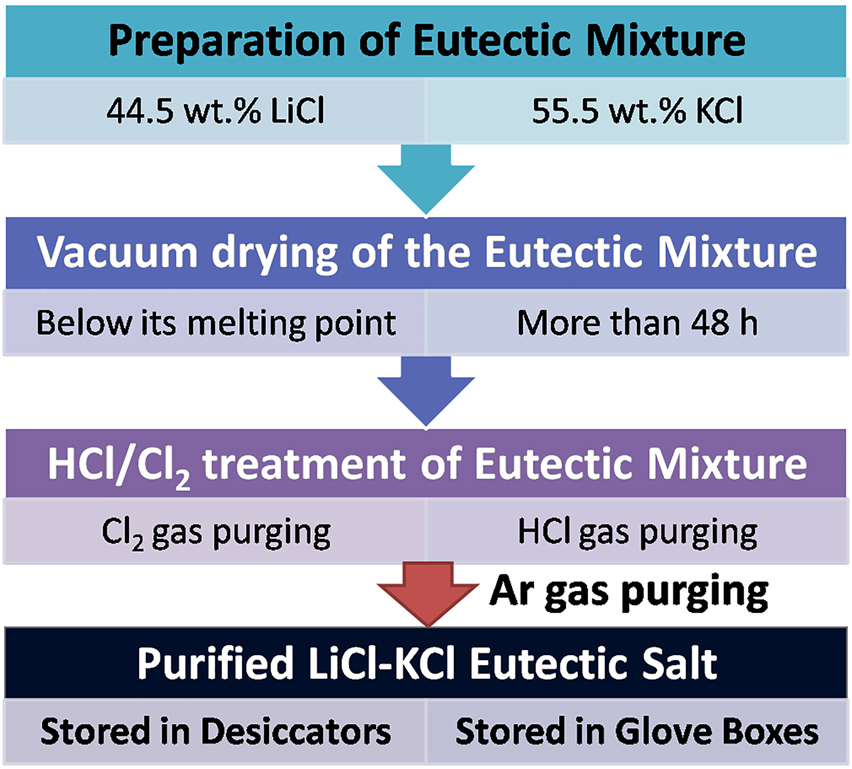

So it is very important to remove the moisture from the fused molten salt to avoid corrosion of materials and maintain the electrochemical stability of the melt for a wide potential region. There are quite a few methods for the purification of LiCl–KCl molten salt is available in the literature. Most methods dealt with removing water and related impurities by vacuum drying, HCl gas purging, Cl2 gas purging, electrolysis, etc. Generally, for research purposes and plant level use, LiCl and KCl salts are dried by vacuum and then used to prepare the eutectic mixture of LiCl–KCl salt. Later the eutectic salt would be treated to completely remove moisture and other impurities. The generally followed purification sequence is illustrated in Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the LiCl–KCl eutectic molten salt purification process.

Laitinen et al. (1957) reported a preparative method for obtaining pure LiCl–KCl salt, which includes drying the eutectic mixture under moderate vacuum, fusion under anhydrous HCl, and removing HCl from the melt by evacuation for about 2–3 h. The pure and impure salts were tested by measuring the residual current by polarographic measurements. Later Maricle and Hume (1960) reported a new method for preparing hydroxide ion-free alkali chloride melts based on Cl2 gas purging with less processing time than Laitinen et al. (1957) method. This new method consists of passing the Cl2 gas through the fused salt melt for about 40 min, followed by argon gas flushing for about 20 min to remove the Cl2 gas without pre-drying of the fused salt. The Cl2 gas reacts with the hydroxide ions (Equation (2)) and eliminates the hydroxide ions.

Raynor (1963) investigated an effective method for the hydroxide ion-free melt using hydrogen chloride gas, and it was found to be effective for the alkali content less. The treatment of fused LiCl–KCl salt with HCl gas after vacuum dry of the salt was found to be better to get pure LiCl–KCl melt. Both the methods by Laitinen et al. (1957) and Raynor (1963) purified the salt with HCl gas. However, different levels of vacuum drying before treatment with HCl gas were used. In Raynor case, the salt mixture was evacuated at 95 °C for 24 h followed by another 24 h evacuation at 200 °C. This salt was further fused with HCl gas at 450 °C for about 2 h followed by purging with dry nitrogen gas for complete removal of the HCl gas. On the other hand, in the purification process reported by Laitinen et al., the salt mixture was vacuum dried for about 6 h at a vacuum level of 0.1–0.2 mm Hg, followed by ball milling to obtain a fine free-flowing powder. This vacuum dried mixture was further treated by evacuation at room temperature for about 3 days, followed by fusion with HCl gas at 500 °C. Later the HCl gas was completely removed by evacuation and purging with Ar gas. More or less, both the processes used same sequence of treatment; however, the extent of vacuum treatment, the amount of salt treated and the experimental setup are different.

Furihata et al. (1978) studied the purification of eutectic LiCl–KCl salt by measuring polarograms at Pt electrode in LiCl–KCl melt having various impurities. The authors used various purification methods, and purified salts to measure the polarograms to ascertain the purification level by observing the residual current. They used various combinations of purification methods, like 20 min Cl2 gas purging followed by 20 min Ar gas purging, 20 min Cl2 followed by 90 min Ar bubbling, 120 min Ar bubbling only, 120 min HCl followed by 130 min Ar bubbling, and 30 min HCl, 60 min Ar bubbling followed by filtration through a Pyrex or silica glass filter. They reported that HCl bubbling, then Ar bubbling followed by filtration was the best method to purify the eutectic LiCl–KCl salt. Zhang et al. (2018) used a high-temperature calcinations process, HCl gas bubbling, followed by potentiostat electrolysis to purify LiCl–KCl molten salt. They compared the impurities in the molten salt before and after the purification process using thermogravimetry, and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry methods. The results indicated that the maximum calcination temperature for removing the volatile impurities from the salt was around 450–650 °C, and the optimum electrolysis potential to remove the metal ion impurities was −2.3 V versus Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Recently Swain et al. (2020) studied the redox behaviour of moisture in LiCl–KCl eutectic melt by cyclic voltammetric studies to find out the best purification procedure of LiCl–KCl eutectic for pyrochemical reprocessing applications. About 19 different LiCl–KCl melts with different contents of moisture have been investigated using the various sequences of treatments in their work and identified the best purification process with the help of cyclic voltammetric studies. The authors at their laboratory used the Cl2 treatment to purify the eutectic melt for their laboratory-scale demonstration of the pyrochemical reprocessing. But with the underlying problems in handling the corrosive and harmful gases like Cl2 and HCl for the purification of the eutectic melt in large scale, the authors attempted to use only vacuum drying for purification. They reported that the eutectic salt, which was vacuum dried at 300 °C for 110 h was similar in purity that of the chlorinated eutectic salt (Swain et al. 2020).

As seen from the above purification processes, mostly chlorine or HCl gas along with vacuum drying was used for the purification of LiCl–KCl salt. As the gases are harmful, HCl and Cl2, the recent work by Swain et al. (2020) provides some methods to avoid the use of these gases in the purification of the salt as they reported a similar extent of purification only by using vacuum drying. In general, the moisture affects to a great extent during the electrorefining process of the pyrochemical reprocessing (Swain et al. 2022). More studies are needed to be focused on in future to ascertain the minimum amount of oxygen, and moisture that can be tolerable for the electrorefining and corrosion processes. It is desirable that the purity of the molten salt should be less than 50 ppm of moisture for the above-said applications. The initial moisture and other impurities like metal ions depend on the preparation, handling and storing conditions of the eutectic melt. So it is essential to purify the salt before using for the intended applications. As seen from the literature about the purification of the salt, the best method for purifying the salt in large quantity would be vacuum drying at 300 °C for longer time. For laboratory scale experiments, one can use the Cl2 of HCl gas purging for purification of the molten salt with proper care.

4 Material performance in molten salts: corrosion studies in molten LiCl–KCl salt

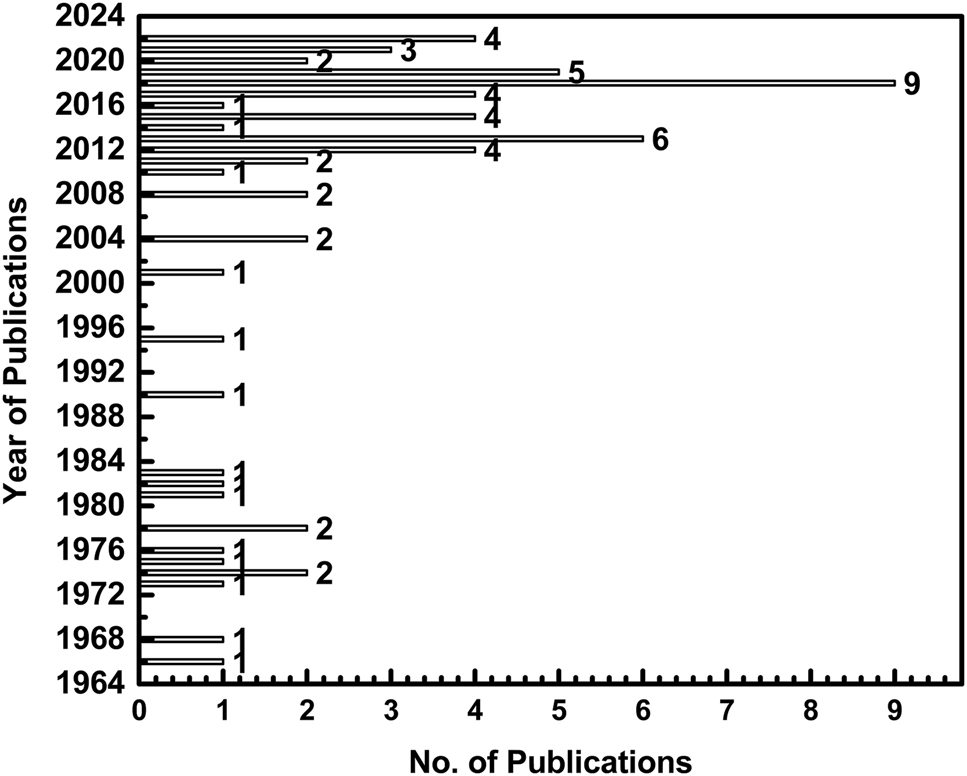

Extensive corrosion studies have been carried out by various authors worldwide for various applications, mainly using molten LiCl–KCl salt and some other salt additives. Full literature primarily focusing on LiCl–KCl molten salt and the corrosion issues of the salt are surveyed in this section up to date. The complete literature search from the Scopus indexing website was carried out by providing the keywords, “LiCl–KCl” and “corrosion”. Every individual literature from the search results were examined and irrelevant literature data was omitted. The complete literature about the corrosion studies of LiCl–KCl molten salts are discussed below in chronological order and material type wise. The bar chart shown in Figure 3 shows literature from 1966 to 2022, and the highest number of publications that appeared in this area are in the last decade. In the recent past, the number of publications dealing with the corrosion in LiCl–KCl molten salts is increasing. The detailed literature surveys about the publications dealing with the corrosion of materials in molten LiCl–KCl salts are discussed. The literature is surveyed in chronological order and provided in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 provides the studies where only LiCl–KCl salt was used, and Table 3 provides the literature where LiCl–KCl salt with additions of various other salts used for corrosion studies. These tables provide the significant findings of those works. As seen from Tables 2 and 3, a wide variety of materials starting from metals, alloys, single crystals, intermetallics, glass and ceramics have been studied in molten LiCl–KCl salt. A detailed account of all these studies, along with their major findings is provided below under the sub-headings of pure metals and non-metals, iron base alloys, nickel base alloys, titanium base alloys and ceramics, glasses and others.

Literature data obtained from “Scopus” website by using “LiCl–KCl” and “corrosion” as key words.

Literature works related to the corrosion studies in plain LiCl–KCl molten salt.

| Year | Authors | Molten salt system | Studied materials | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Keddy | LiCl–KCl | Ag and Ag coated Pt | Found increase of Ag + ions concentration in the melt and also found the formation of Li–Ag phase on the Ag electrode | Keddy (1966) |

| 1973 | Kovalevski et al. | LiCl–KCl melt | Liquid alloys of Zn with Y and other rare-earth elements, Ce, Nd, La, Dy, Er, Y, Sm and Yb | Measured the standard potentials of all these metals and corrosion rates are calculated. Experimentally also corrosion rates measured. It was observed that the corrosion of the alloys is approximately equal and increased with temperature | Kovalevskii et al. (1973) |

| 1974 | Battles et al. | LiCl–KCl melt | Stainless steels and Armco electromagnet iron and several other materials | Stainless steels and Armco electromagnet iron are found to be compatible with LiCl–KCl electrolyte at 400 °C | Battles et al. (1974) |

| 1975 | Smyrl and Blackburn | Several molten salt systems including pure LiCl–KCl melt in argon atmosphere dry box at 375 °C | Ti–8Al–1Mo–1V alloy | Stress corrosion cracking found to be similar that of aqueous systems with respect to the influence of mechanical microstructure, metallurgical heat treatment. And also found that no effect of hydrogen in the form of H2O and H− in molten LiCl–KCl on crack extension | Smyrl and Blackburn (1975) |

| 1976 | Sharma Ram et al. | Various molten salts including LiCl–KCl | AlN | AlN undergone intergranular attack by Li | Sharma et al. (1976) |

| 1983 | Park | Molten eutectic LiCl–KCl at 450 °C | Armco iron | Observed that during development work on a LiAl/FeS cell system, steel structures were seriously corroded when contact with molten salt | Park (1983) |

| 1990 | Colom and de la Plaza | LiCl–KCl eutectic melt at 400–600 °C | Iridium (Ir) | Observed the anodic dissolution and passivation of Ir. Formation of a porous IrO2 layer is also observed | Colom and de la Plaza (1990) |

| 2008 | Ravi Shankar and Kamachi Mudali | Molten LiCl–KCl eutectic at 600 °C | Type 316L stainless steel and yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) coated 316L SS | Severe corrosion of uncoated 316L SS observed with selective diffusion of Cr and YSZ coated sample performed well in the molten salt for during 1000 h immersion test | Ravi Shankar and Kamachi Mudali (2008) |

| 2008 | Ravi Shankar et al. | Molten LiCl–KCl eutectic at 600 °C | YSZ coated 316L SS and laser re-melted sample | YSZ coatings performed well without coating peel-off for about 500 h. YSZ coating defects eliminated by laser re-melting of the coatings | Ravi Shankar et al. (2008) |

| 2010 | Ravi Shankar et al. | Molten LiCl–KCl eutectic in air for 2 h | EF Ni with and without Ni–W coating, 316L SS, and Inconel 625 alloy | Inconel 625 and coated Ni showed better performance | Ravi Shankar et al. (2010) |

| 2011 | Westphal et al. | LiCl–KCl eutectic | Electrorefiner vessel made of 2.25Cr–1Mo alloy | Corrosion rate found to be “outstanding”, assumed that uniform conditions | Westphal et al. (2011) |

| 2011 | Elkin and Kovalevskii | LiCl–KCl eutectic | Gd and Yb studied by gravimetric and EMF methods | The corrosion rate of Yb was 3–5 times higher than that of Gd | El’kin and Kovalevskii (2011) |

| 2012 | Kovalevskii and Elkin | LiCl (60%)–KCl melt | Studied the effect of temperature and duration of corrosion test on Sm and La | The corrosion rate of Sm is an order of magnitude higher than that of La | Kovalevskii and El’kin (2012) |

| 2012, 2013 | Jagadeesh Sure et al. | In LiCl–KCl eutectic for about 2000 h at 600 °C | HDG and YSZ coated HDG | HDG shown weight loss and YSZ coated HDG shown weight gain and better performance | Jagadeesh et al. (2012a,2013b) |

| 2012 | Barraza-Fierro et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt at various temperatures | Intermetallics of Fe-40 at.%Al with the additions of Li and Cu | Li addition showed increase in corrosion and Cu addition showed reduction in corrosion rate of intermetallics | Barraza-Fierro et al. (2012) |

| 2012 | Wang et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt at 450 °C | 304SS, 316L SS, and Q235A | 316L SS showed better corrosion resistance could be due to the presence of Ni and Mo in the alloy | Wang et al. (2012) |

| 2013 | Ravi Shankar et al. | In LiCl–KCl salt in air for 2 h | Alloy 600, 625, 690 and alloy 800H | Alloy 600 and 690 offered better corrosion resistance than alloy 650 and alloy 800H | Ravi Shankar et al. (2013a) |

| 2013 | Jagadeesh Sure et al. | In LiCl–KCl melt for about 2000h at 600 °C under argon atmosphere | Pyrolytic graphite | Pyrolytic graphite showed excellent corrosion resistance | Jagadeesh et al. (2013c) |

| 2013 | Ravi Shankar et al. | In molten LiCl–KCl eutectic salt at 600 °C | 2.25Cr–1Mo steel, 9Cr–1Mo steel, alloy 600, alloy 625, alloy 690 and YSZ coated samples | YSZ coatings performed well than the uncoated samples. The order of corrosion resistance to molten salt observed as follows Ni based alloys, followed by 9Cr–1Mo steel and 2.25Cr–1Mo steel | Ravi Shankar et al. (2013b) |

| 2013 | Jagadeesh Sure et al. | In LiCl–KCl molten salt at 600 °C for about 3 h | PLD yttria coatings on graphite substrates | Yttria showed better protection in this short duration experiments | Jagadeesh et al. (2013a) |

| 2014 | Jagadeesh Sure et al. | In LiCl–KCl molten salts at 600 °C for 2000 h under high pure argon atmosphere | Low density graphite (LDG), high density graphite (HDG), glassy carbon (GC) and pyrolytic graphite (PyG) | Corrosion resistance of the materials found to be in the following order: LDG < HDG < GC < PyG | Jagadeesh et al. (2014) |

| 2015 | Wang et al. | LiCl–KCl eutectic for 100 h at 550, 650 and 750 °C in air | Polycrystalline Ti3SiC2 | The sample corroded at higher temperatures and showed better performance at 550 °C | Wang et al. (2015) |

| 2015 | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt | Alloy 600, 9Cr–1Mo steel and SS410 under inert and reactive atmospheres for 24 h duration at 500 and 600 °C using TG measurements | Insignificant weight gains observed at 500 °C in both atmospheres. At 600 °C marginally higher weights observed. Molten salt corrosion was more in 9Cr–1Mo steel compared to SS410 followed by alloy 600 | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2015) |

| 2015 | Barraza-Fierro et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt | Fe-40 at.% Al intermetallics with additions of Cu and Li evaluated by electrochemical methods | The additions improved the corrosion resistance of the intermetallic alloy. Reported that the HCl, O2 and OH− are the reduction processes in the corrosion process of these alloys | Barraza-Fierro et al. (2015) |

| 2016 | Jagadeesh Sure et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt at 600 °C for 24 h duration | Laser melted plasma sprayed alumina-40 wt% titania coatings on HDG | Improvement of the coatings after laser re-melting at different laser powers observed | Jagadeesh et al. (2016) |

| 2017 | Barnett | LiCl–KCl molten salt | SS 310, P91 and alloy 625, etc. | Pitting and intergranular corrosion observed in alloy 625. SS 310 and P91 are also corroded | Barnett (2017) |

| 2017 | Sim et al. | LiCl–KCl salt at low temperature in presence of oxygen and moisture | Type 304, type 316 and copper | Pitting corrosion observed at above 60 °C in steels; type 316 showed better corrosion resistant than type 304SS. Cu corrosion was three times more than steels | Sim et al. (2017) |

| 2018 | Ravi Shankar and Kamachi Mudali | LiCl–KCl salt at 600 °C in Cl2 gas bubbling | Inconel alloys 600, 625, 690 and their welds | Alloy 600 and 690 are more corrosion resistant than alloy 625 | Ravi Shankar and Kamachi Mudali (2018) |

| 2018 | Horvath and Simpson | LiCl–KCl molten salt in water bubbled condition | Ni | NiCl2 formed and it further hydrolyzed to NiO | Horvath and Simpson (2018) |

| 2018 | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. | LiCl–KCl salt at 600 °C | YSZ coated HDG with and without SiC interlayer coating | No delamination or failure of the coating observed for both the samples up to 3500 h duration | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2018a) |

| 2019 | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt at 500 °C for 98 h | 9Cr–1Mo steel | 9Cr–1Mo steel corroded by the molten salt and formed intermittent non-protective oxide films over the surface | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2019) |

| 2021 | Magnus et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt | Ti3AlC2 | Selective leaching of Al observed, and further the Ti3C2 converted to Ti3C2Cl2 by chlorination | Magnus et al. (2021) |

| 2022 | Jagadeeswara Rao and Ningshen | LiCl–KCl molten salt at 500 °C for 200 h | 2.25Cr–1Mo alloy | The OCP shifted to noble direction and Rp got increased and the alloy showed intermittent oxide scale formation | Jagadeeswara Rao and Ningshen (2022) |

| 2022 | Wang et al. | EuCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt | T91 | Developed a three electrode corrosion probe for monitoring impurity driven high temperature corrosion. The corrosion rate of T91 was increased with duration of exposure and approached a steady state after 24 h | Wang et al. (2022) |

| 2022 | Chang et al. | EuCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt at 500 °C for 24 h | Haynes C276, Inconel 600, Incoloy 800 and 316L stainless steel | Rapid dissoulution of Fe, Cr and Ni were observed in all the alloys. The corrosion rates of the alloys are found to be 2 orders of magnitude higher than in LiCl–KCl salt due to the presence of 2 wt% EuCl3 | Chang et al. (2022) |

Literature works related to the corrosion studies in LiCl–KCl molten salt containing other ions.

| Year | Authors | Molten salt system | Studied materials | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Chauvin et al. | AgCl–LiCl–KCl eutectic | Ag under both isothermal and non-isothermal conditions | Severe corrosion of Ag observed under non-isothermal condition due to the mass transfer of Ag from hotter regions to colder regions | Chauvin et al. (1970) |

| 1974 | Barbe et al. | Molten dehydrated LiCl–KCl–NaCl eutectic salt | Cu, Al and Al–Cu alloy | Under non-polarized condition, the samples did not corrode for 4 h and under anodic polarization conditions they corroded | Barbe et al. (1974) |

| 1978 | Sharma | LiCl–KCl electrolyte and Li–LiCl–KCl melt | BN cloth | Slight corrosion of BN cloth observed during the charge-discharge cycles tests and severe corrosion observed during static immersion tests in Li–LiCl–KCl melt | Sharma (1978) |

| 1978 | Numata and Haruyama | LiCl–KCl melt with nitrate ions at 500 °C, argon atmosphere | Ni | Corrosion rate observed by both electrochemical measurements and by weight loss measurements are found to be in good agreement and it showed that the corrosion rate of Ni was controlled by diffusion of the nitrate | Numata and Haruyama (1978) |

| 1981 | Bandyopadhyay | LiCl–KCl and LiCl–KCl–FeS2 in argon glove box at 500 °C | Various ceramic coatings including TiN, TiCN, TiB2 combinations of TiC and TiN, etc. | Static corrosion tests showed that none of the coatings being tested in this investigation were found to be completely satisfactory. The CVD-TiC and TiN coatings showed significant promise | Bandyopadhyay (1981) |

| 1981 | Park and Yoon | Molten eutectic LiCl–KCl with and without Li2S at 450 °C | Armco iron | Oxygen content enhanced the corrosion of Armco iron and the effect of moisture was negligible on the corrosion | Park and Yoon (1981) |

| 1982 | Feng and Melendres | LiCl–KCl eutectic melt and with additions of lithium oxide at 375° and 450 °C | Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Mo | Observed characteristic corrosion-passivation behaviour. The anodic corrosion rates are found to be less in pure LiCl–KCl melt and decreased in the order of Fe > Ni > Co > Cu > Mo | Feng and Melendres (1982) |

| 1995 | Tada and Ito | LiCl–KCl eutectic melt containing oxide ion | Ni | Passive oxide film growth was observed. Pitting corrosion due to breakdown of thin oxide film observed | Tada and Ito (1995) |

| 2001 | Dusheiko | LiCl–KCl and LiF–LiCl–LiBr at 350–500 °C | Fe, Ti, Cu, Al sulfides | The solubilities of these metal sulfides determined | Dusheiko (2001) |

| 2004 | Hayashi et al. | LiCl–KCl eutectic melt with NdCl2, NdCl3 and Nd | Pyrex and quartz glass cells | UV and visible spectrophotometric study was made. Black corrosion products were observed on the surface of the glass cells. The corrosion products contained NdOCl | Hayashi et al. (2004) |

| 2004 | Goto et al. | LiCl–KCl–Li3N | ZrN film on Zr | The corrosion resistance of the nitrided layer formed by electrochemical nitriding was identical to that formed by plasma processing | Goto et al. (2004) |

| 2013 | Paek et al. | In UCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt | Mo, graphite and glassy carbon tested | Mo anode corrosion observed; graphite and glassy carbon electrodes performed well in this melt | Paek et al. (2013) |

| 2015 | Hofmeister et al. | LiCl–KCl–CsCl ternary molten salt | Stainless steels and single crystal super alloys | Severe intergranular corrosion of low carbon steel was observed. The single crystal Ni based super alloy showed better performance for up to 27 h | Hofmeister et al. (2015) |

| 2017 | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. | UCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt at 600 °C up to 2000 h. | YSZ coated 9Cr–1Mo steel; uncoated 9Cr–1Mo steel | Uncoated 9Cr–1Mo severely corroded. No delamination of the YSZ coating observed | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2017b, 2017a) |

| 2018 | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. | UCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt in inert and reactive atmospheres | SS410, 2.25Cr–1Mo and 9Cr–1Mo steel | Cr depletion and Cr rich corrosion products formation observed. Corrosion more in 9Cr–1Mo steel than 2.25Cr–1Mo steel followed by SS410 at 600 °C | Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2018b) |

| 2018 | Madhura et al. | UCl3–LiCl–KCl salt at 600 °C for about 2000 h | Pyrolytic graphite | Pyrolytic graphite showed excellent corrosion resistant | Madhura et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | Kazakovtseva et al. | NdCl3–LiCl–KCl melt at 500 °C | 12Kh18N10T steel | Corrosion rate was varied with the amount of NdCl3 and with temperature | Kazakovtseva et al. (2018) |

| 2018 | Kumar et al. | LiCl–KCl–Na2SO4 molten salt at 700 °C under Ar, O2, O2-0.1%SO2 atmospheres | Ni alloys (Ni, β-NiAl, β-NiAl/Cr) | Corrosion resistance of Ni alloys was affected by nature of gaseous atmosphere and alloying elements (Al and Cr) | Kumar et al. (2018a) |

| 2019 | Karfidov and Nikitina | LiCl–KCl melt + LaCl3 | Ni | Corrosion rate increased with temperature and decreased with the content of LaCl3 in the melt | Karfidov and Nikitina (2019) |

| 2019 | Nikitina et al. | LiCl–KCl salt with additions of CeCl3, NdCl3 and UCl3 at 500–650 °C for 100 h | 16Cr12MoWSVNbB (EP-823) steel | Fe found to be dissolved more than Cr and Mn. Intergranualar corrosion observed in UCl3 containing melt | Nikitina et al. (2019) |

| 2019 | Osipenko et al. | LiCl–KCl–CsCl eutectic melt in the temperature range of 300–400 °C | Technetium (Tc) | Corrosion potential of Tc found to be lies between 0.158 V and −0.038 V versus Ag/AgCl | Osipenko et al. (2019) |

| 2020 | Jagadeeswara Rao and Ningshen | LiCl–KCl–UCl3 for 24 h by TG under inert and reactive atmospheres at 500 and 600 °C | 2.25Cr–1Mo, 9Cr–1Mo and SS410 | Higher weight gain observed for 2.25Cr–1Mo in inert atmosphere and in reactive atmosphere SS410 and 9Cr–1Mo steel showed more weight gain at 500 and 600 °C, respectively | Jagadeeswara Rao and Ningshen (2020) |

| 2020 | Kazakovtseva et al. | LiCl–KCl molten salt containing Nd3+ and Ce3+ | Mo | Mo showed uniform corrosion. Mo corrosion was less in presence of Nd3+ and Ce3+ ions | Kazakovtseva et al. (2020) |

| 2021 | Jiaqi et al. | LiCl–KCl–MgCl2 melts | Ni | More corrosion of Ni observed by the addition of MgCl2 and also MgO formation was observed on the Ni electrode | Jiaqi et al. (2021) |

| 2022 | Gardner et al. | LiCl–KCl eutectic salt with NaCl | Stainless steel | Corrosion of stainless steel in NaCl–LiCl–KCl melt decreased compared to LiCl–KCl salt due to change in the deliquescence of the salt | Gardner et al. (2022) |

4.1 Pure metals and non-metals

Keddy (1966) studied the corrosion nature of ultra-pure silver (Ag) and Ag plated platinum (Pt) electrode in molten LiCl–KCl salt in an argon atmosphere. The corrosion studies revealed the increase of Ag+ ion concentration in the melt and also evidenced the formation of Li–Ag phase on the Ag electrode (Table 2). Chauvin et al. (1970) studied the corrosion of Ag in a molten medium of AgCl–LiCl–KCl eutectic at 500 °C under both isothermal and non-isothermal conditions (Table 3). The corrosion of Ag in the isothermal condition was low, and under non-isothermal conditions, corrosion is severe due to mass transfer of Ag from hotter regions to colder regions. They reported the dissolution of Ag in the hot zone and deposition at the colder zones. Kovalevskii et al. (1973) investigated the corrosion of liquid alloys of zinc with Y and with other rare-earth elements in LiCl–KCl melt and reported their potentials and corrosion behaviour. It was observed that the corrosion of the alloys is approximately equal and increased with temperature. Battles et al. (1974) carried out the corrosion test of numerous materials including Type 304SS, Type 316 SS, Type 347 SS, Type 430 SS, Fe, Armco electromagnet iron, and ceramics like yttria, calcia, thoria, berriliya, etc. in LiCl–KCl melt at 400 °C and 500 °C for battery applications. Stainless steels and Armco electromagnet iron are found to be compatible with LiCl–KCl electrolyte and Yttria fabric shown good compatibility with lithium. The corrosion behaviour of copper, aluminium and Al–Cu alloy in molten dehydrated LiCl–KCl-NaCl eutectic at 450 °C was reported by Barbe et al. (1974). It was reported that under non-polarized conditions, the samples did not corrode for 4 h and under anodic polarization conditions they corroded (Table 3). The electrochemical corrosion behaviours of Nickel in LiCl–KCl melt with nitrate ions at 500 °C under argon atmosphere studied by Numata and Haruyama (1978). They reported that the corrosion rate of Ni was controlled by diffusion of the nitrate ions and showed that the corrosion rate obtained by the polarization resistance method and weight loss method are in good agreement.

Park and Yoon (1981) also studied the effect of oxygen and moisture on the corrosion of Armco Iron in LiCl–KCl salt with and without Li2S. The presence of oxygen found to enhance the corrosion of Armco iron and moisture did not have much effect on corrosion (Table 3). Feng and Melendres (1982) studied the anodic polarization of Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Mo in molten LiCI–KCI eutectic melt with lithium oxide at 375 and 450 °C. The anodic corrosion rates are found to be less in pure LiCl–KCl melt and decreased in the order of Fe > Ni > Co > Cu > Mo. Passivation behaviour was observed in the case of LiCl–KCl–Li2O melt. Park (1983) studied the corrosion of Armco iron in molten eutectic LiCl–KCl at 450 °C during the LiAl/FeS cell system development (Table 2) and reported the anodic dissolution of ARMCO Iron in LiCl–KCl salt. The moisture contamination of salt did not alter the corrosion, but oxygen impurity influences the corrosion of Armco Fe. Colom and de la Plaza (1990) reported the anodic dissolution behaviour of Iridium in LiCl–KCl melt at 400–600 °C probed by cyclic voltammetry, potentiodynamic measurements and observed that anodic dissolution and passivation. Passive oxide film formation and pitting corrosion of nickel in LiCl–KCl eutectic melt having oxide ions was reported by Tada and Ito (1995). This passivation was called as underpotential passivation due to formation at more negative potentials.

The corrosion of gadolinium (Gd) and ytterbium (Yb) in molten eutectic of LiCl–KCl salt was studied by gravimetric and EMF methods in the temperature range of 400–700 °C under argon gas atmosphere by El’kin and Kovalevskii (2011). It was reported that the corrosion rate of Yb was 3–5 times higher than that of Gd in LiCl–KCl melt. Similarly Kovalevskii and El’kin (2012) also studied the effect of temperature and duration of corrosion test on the corrosion of samarium (Sm) and lanthanum (La) in LiCl (60%)–KCl melt in the temperature range of 400–700 °C under argon gas flow. They reported that the corrosion rate of Sm is an order of magnitude higher than that of La in the molten salt (Table 2). Paek et al. (2013) observed the corrosion of Mo electrode when used as an anode during the electrolysis process in UCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt in argon filled glove box containing less than 2 ppm of water and oxygen at 500 °C. It was reported that the glassy carbon and graphite electrodes performed well as an anode materials for the electrowinning process of pyroprocessing. The effect of water bubbled along with argon gas into LiCl–KCl molten salt on the corrosion behaviour of Ni was studied by electrochemical techniques by Horvath and Simpson (2018) at 500 °C. OCP was found to be increased as the water bubbling continued and formation of NiCl2 was evidenced and also the hydrolysis of NiCl2 to NiO was observed which resulted in the plateau of OCP. Karfidov and Nikitina (2019) studied the effect of 0.5–2 mol% LaCl3 on the molten salt corrosion of nickel in LiCl–KCl melt in the temperature range of 500–800 °C in air atmosphere. They reported that the corrosion rate increased with temperature and decreased with the content of LaCl3 in the melt, which is due to the inhibition effect of LaCl3.

Corrosion potential of technetium (Tc) in LiCl–KCl–CsCl eutectic melt was determined by Osipenko et al. (2019) in the temperature range of 300–400 °C in argon atmosphere glove box with less than 3 ppm of oxygen and less than 1.2 ppm of moisture. It was reported the potential lies between 0.158 V and −0.038 V versus Ag/AgCl within the studied temperature range. The corrosion of Mo in LiCl–KCl molten salt containing Nd3+ and Ce3+ has been studied using electrochemical methods at 500 °C by Kazakovtseva et al. (2020) and estimated the rate of metal corrosion by gravimetric experiments. Mo has undergone uniform corrosion in the melt, and the corrosion was higher in the melt without Nd3+ and Ce3+ ions. These Nd3+ and Ce3+ ions act as anodic type shielding inhibitors; hence, less corrosion of Mo in the presence of these ions. The Ni electrode corrosion in LiCl–KCl–MgCl2 melts has been studied under an argon atmosphere by both immersion and electrochemical experiments by Jiaqi et al. (2021) (Table 3). The corrosion of Ni got more prominent by the addition of MgCl2, and MgO formation was observed on the Ni electrode surface. It was also found out the serious effects of water present in the salt on the electrochemical reactions during corrosion of Ni.

Jagadeesh et al. (2013c) tested pyrolytic graphite in molten LiCl–KCl salt by immersion studies for about 2000 h at 600 °C under argon atmosphere, and concluded that the excellent corrosion resistance of the highly dense pyrolytic graphite. The corrosion behaviour of different types of carbon materials like low density graphite (LDG), high density graphite (HDG), glassy carbon (GC) and pyrolytic graphite (PyG) have been studied in LiCl–KCl molten salts at 600 °C for 2000 h under high pure argon atmosphere by Jagadeesh et al. (2014). LDG and HDG are severely attacked by molten salts, and the penetration of the salt into GC and PyG was insignificant. The corrosion resistance of these materials in LiCl–KCl salt were found to be in the order low density graphite < high density graphite < glassy carbon < pyrolytic graphite (Table 2). The corrosion of the highly oriented graphitic material, pyrolytic graphite in molten UCl3–LiCl–KCl salt at 600 °C for about 2000 h was evaluated by Madhura et al. (2018) and reported the excellent corrosion resistance of the pyrolytic graphite. The authors also reported a marginal increase in structural dis-orderness of PyG evident from Raman analysis. The absence of molten salt on the PyG surface after exposure is also confirmed by XPS analysis.

4.2 Iron based alloys

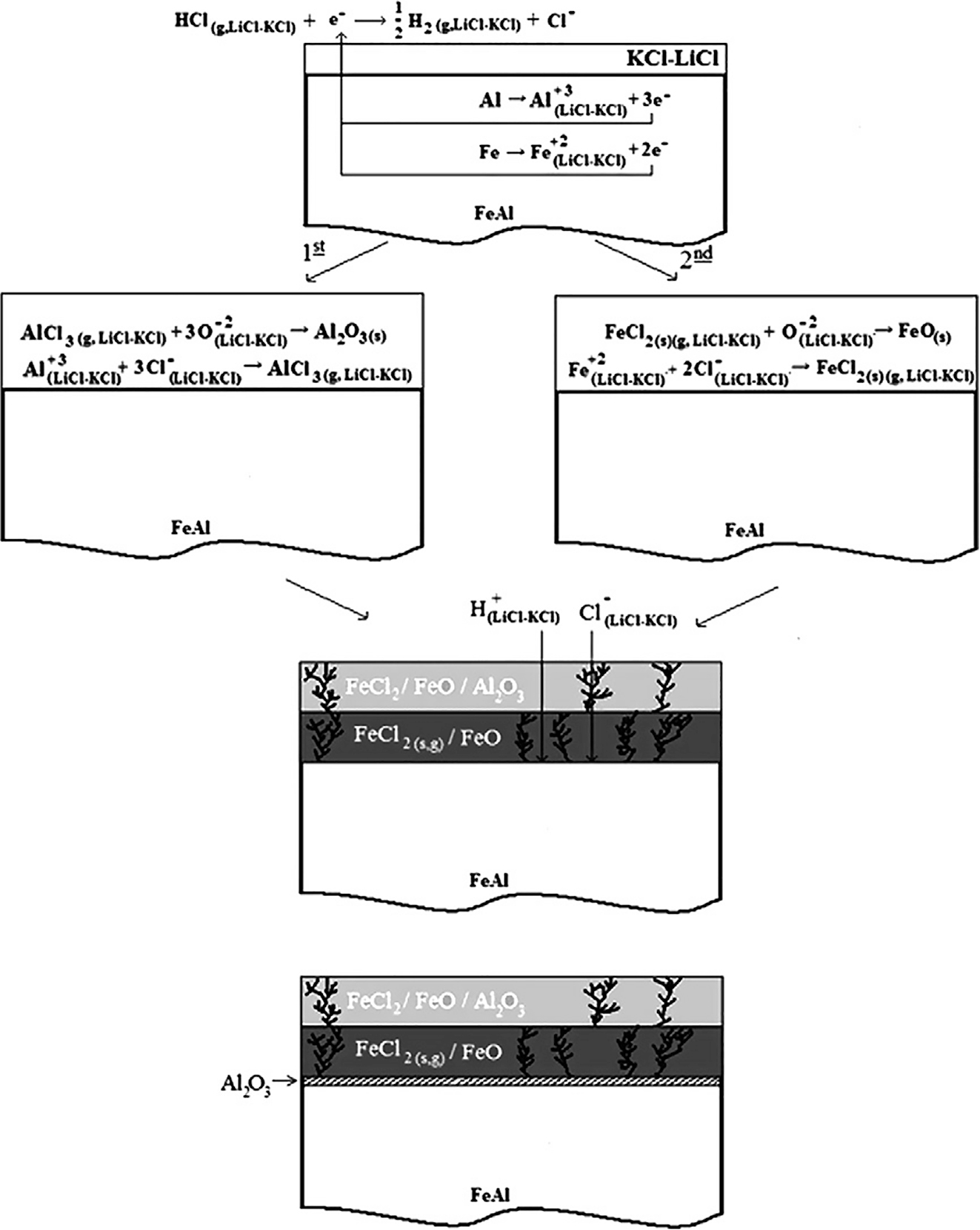

Westphal et al. (2011) evaluated the corrosion of 2.25Cr–1Mo alloy for electrorefiner vessel in LiCl–KCl eutectic in pyrometallurgical processing. The weight loss data of the electrorefiner vessel made up of 2.25Cr–1Mo alloy, used in LiCl–KCl eutectic with uranium containing the transition metal impurities revealed the corrosion rate is “outstanding”, assuming uniform conditions (Table 2). Barraza-Fierro et al. (2012) was studied the corrosion of intermetallics Fe-40 at% Al in LiCl–KCl molten salt at 450, 500 and 550 °C in air atmosphere, and evaluated the effect of Cu and Li additions on the corrosion behaviour. The authors reported that the addition of Li slightly increased the corrosion rate of the intermetallic, and Cu additions improved the corrosion resistance of the intermetallics in LiCl–KCl molten salts. The authors suggested a four-stage corrosion mechanism of Fe–Al intermetallic in LiCl–KCl melt as depicted in Figure 4. The first step is the free corrosion of the intermetallic when in contact with the salt, in the second step, the formation of alumina followed by iron oxides from their respective chlorides occurs, this second step leads to the formation of another sub-layer in the third step consists of FeO and it allows the entry of H+, Cl− and O2− from the melt. In the last step these entry of the oxidants led to the formation of thick alumina layer at the alloy and top oxide layer interface. Wang et al. (2012) studied corrosion resistance of steel materials, 304SS, 316L SS, and Q235A, in LiCl–KCl molten salt at 450 °C in argon atmosphere by Tafel curves and EIS measurements and also by weight loss measurements. It was reported that 316LSS showed better corrosion resistance among other alloys, which could be due to the presence of Ni and Mo in alloy 316L SS.

Corrosion mechanism schema proposed for Fe–40 at.% Al intermetallics into electrolytic medium of LiCl–55 wt% KCl eutectic salt. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (Barraza-Fierro et al. 2012).

The corrosion properties of stainless steels, X2CrNi18-9 and Ti-stabilized stainless steel X6CrNiTi18-10 and single crystal Ni based superalloy, CMSX-4, have been investigated in LiCl–KCl–CsCl ternary molten salt at 400, 500 and 600 °C for 1, 3, 9 and 27 h and at 800 °C for 3 h by Hofmeister et al. (2015). They reported the severe intergranular corrosion of low carbon steel, and protection of Ti-stabilized high carbon steel from molten salt corrosion by the formation of Cr2O3 passive layer for shorter exposure times and at below 500 °C. However, the single-crystal Ni-based superalloy was found to be corrosion-resistant in this ternary molten salt at the studied temperatures for a maximum of 27 h duration. Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2015) studied the corrosion behaviour of Alloy 600, 9Cr–1Mo steel and SS410 in LiCl–KCl molten salt by thermogravimetry at 500 and 600 °C for about 24 h in inert argon, and reactive (10% oxygen + argon) atmospheres. The authors found that insignificant weight gains for the studied alloys, namely Alloy 600, 9Cr–1Mo steel, and stainless steel 410 at 500 °C in both atmospheres. But reported slightly higher weight gain in case of Alloy 600 than 9Cr–1Mo steel and SS 410 at 600 °C. The weight gains were found to be higher in reactive atmosphere compared to inert atmosphere. The study revealed the Cr-depletion and Cr-rich regions on the alloy surfaces with the formation of LiCrO2 corrosion layer. The study concluded that the molten salt corrosion was more in 9Cr–1Mo steel compared to SS410 followed by Alloy 600.

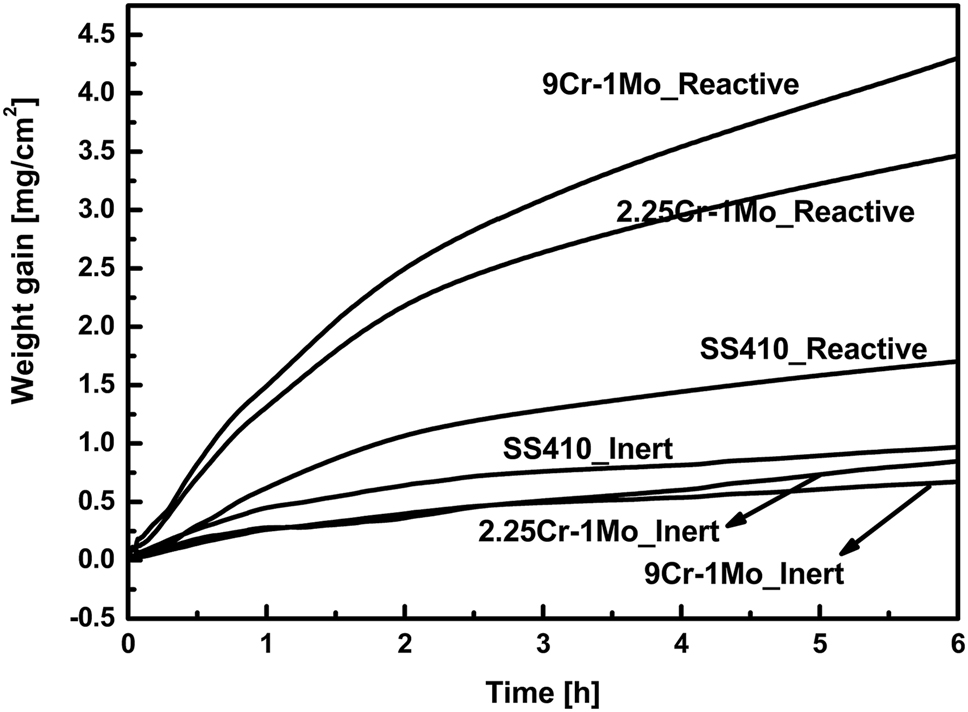

The effect of Cu and Li additions on the hot corrosion Fe-40 at.% Al intermetallics exposed to molten LiCl–KCl salt was investigated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, transmission line modeling, and cathodic polarization at 450, 500 and 550 °C for 60 and 720 min by Barraza-Fierro et al. (2015). The authors concluded that both the additions of the alloys improved the corrosion resistance of the Fe–Al intermetallic alloy. They reported that the HCl, O2 and OH− are the reduction processes in the corrosion process of these alloys. Sim et al. (2017) studied the corrosion of stainless steels, type 304, type 316 and copper in LiCl–KCl salt at low temperatures, 30 °C, 40 °C, 60 °C and 80 °C for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h in the presence of oxygen and moisture. It was observed that pitting corrosion occurred on stainless steels at a temperature above 60 °C, and copper corrosion was found to be three times more than stainless steels at low temperatures. Type 316 SS exhibited better corrosion resistance than type 304 during these studies in LiCl–KCl salt. The corrosion attack of UCl3–LiCl–KCl on the structural alloys has been studied by thermogravimetry at 500 and 600 °C by Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2018b). The alloys, SS410, 2.25Cr–1Mo and 9Cr–1Mo steel showed insignificant weight gain in inert argon atmosphere and marginal weight gain in reactive oxygen (10%) containing argon atmosphere during the exposure to molten salt for about 6 h duration as shown in Figure 5. In a reactive atmosphere at 600 °C, 9Cr–1Mo showed more weight gain than 2.25Cr–1Mo, followed by SS410. The corrosion of these alloys indicated the Cr depletion and Cr rich corrosion products formation. It was observed that the corrosion attack was more in 9Cr–1Mo steel than 2.25Cr–1Mo steel followed by SS410 at 600 °C. Intermittent Fe-based oxides were observed on the surface of these alloys after exposure to molten chloride salts.

The weight changes recorded by thermogravimetry of SS410, 9Cr–1Mo steel and 2.25Cr–1Mo immersed in LiCl–KCl–UCl3 molten salt under Ar and Ar + O2 atmospheres at 600 °C. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (Jagadeeswara Rao et al. 2018b).

Kazakovtseva et al. (2018) studied the corrosion of 12Kh18N10T steel in LiCl–KCl with the addition of 0.2–5 mol% NdCl3 at 500 °C for nitride spent nuclear fuel processing applications. The corrosion rate was significantly varied with the amount of NdCl3. Higher corrosion rate was observed for lower NdCl3 concentration and higher concentrations of NdCl3 (1 mol% and above), the corrosion rate was less due to the formation of protective neodymium salts. The cause of corrosion under these conditions was the dissolution of microgalvanic steel-carbide couples and interaction between steel and Nd cations. Similarly, the effect of CeCl3, NdCl3 and UCl3 content in LiCl–KCl salt on the corrosion of 16Cr12MoWSVNbB (EP-823) steel were investigated by Nikitina et al. (2019) at 500–650 °C for a duration of 100 h in argon atmosphere. It was reported that Fe showed more dissolution compared to Cr and Mn from the alloy during corrosion tests, and they also reported that the presence of UCl3, had a major impact on the corrosion of the alloy and reported the corrosion rates. Intergranular corrosion was observed in the melt containing UCl3; and both CeCl3 and NdCl3 containing melts showed little inhibition effect.

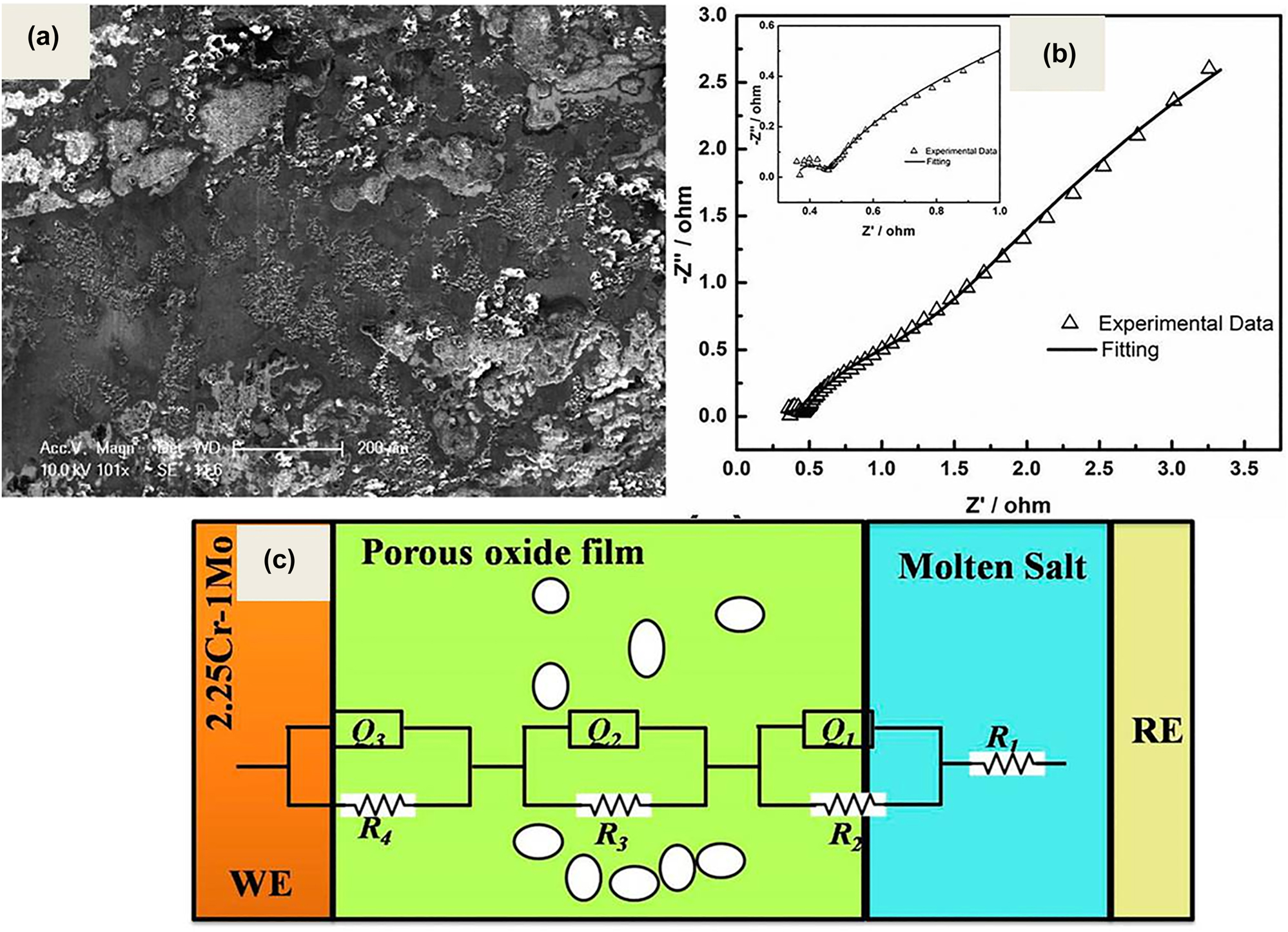

Electrochemical monitoring of the corrosion behaviour of 9Cr–1Mo steel in LiCl–KCl molten salt at 500 °C for duration of 98 h in argon atmosphere has been reported by Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2019). The open circuit potential, linear polarization and electrochemical impedance measurements were used to monitor the corrosion of 9Cr–1Mo and reported that the alloy corroded by the molten salt and formed intermittent non-protective oxide films over the surface, as seen from the SEM image in Figure 6a. The surface oxides are of mostly Fe and Cr oxides, and the depletion and enrichment of both Cr and Mo was observed. Jagadeeswara Rao and Ningshen (2020) studied the corrosion of 2.25Cr–1Mo, 9Cr–1Mo and SS410 in UCl3 containing molten LiCl–KCl for about 24 h using thermogravimetry under inert (argon) and reactive (argon + 10%O2) atmospheres at 500 and 600 °C. It was reported that the weight gain was higher in 2.25Cr–1Mo in an inert atmosphere, and reactive atmosphere; SS410 and 9Cr–1Mo steel showed higher weight gains at 500 and 600 °C, respectively. The oxide scales formed on these alloys were found to be α-Fe2O3, γ-FeOOH, Fe3O4, Cr2O3 and FeCr2O4. The corrosion property of 2.25Cr–1Mo alloy was carried out by electrochemical measurements while exposing the alloy to LiCl–KCl molten salt for about 200 h at 500 °C in argon atmosphere by Jagadeeswara Rao and Ningshen (2022). The authors reported that the open circuit potential shifted towards noble direction and the polarization resistance increased and the alloy showed intermittent oxide scale formation. The intermittent oxide scale formation was supported by impedance data, where it showed three time constants indicating the intermittent oxide scale formation. Figure 6b shows the Nyquist plot recorded at 90 h during immersion in molten salt and its fitting data using the equivalent circuit shown in Figure 6c. Gardner et al. (2022) studied the effect of deliquescence of LiCl–KCl eutectic salt by the addition of NaCl on the corrosion of stainless steel in a humid air environment for the interim waste salt storage applications. They reported that the deliquescence of the eutectic salt of LiCl–KCl was decreased by the addition of about 89 mass% of NaCl which further decreased the corrosion of stainless steel compared to LiCl–KCl eutectic salt alone.

Electrochemical monitoring of corrosion behaviour of alloys in LiCl-KCl molten salt: (a) SEM image of the 9Cr–1Mo steel after exposure to molten LiCl–KCl salt for 98 h; reprinted with permission of Elsevier (Jagadeeswara Rao et al. 2019); (b) Nyquist plot of 2.25Cr–1Mo at 90 h immersion in LiCl–KCl salt along with its fitting; (c) pictorial representation of the various equivalent circuit elements used for impedance data fitting of figure (b); reprinted with permission from Taylor & Francis Ltd. (Jagadeeswara Rao and Ningshen 2022).

Recently, Wang et al. (2022) developed a three electrode corrosion probe for monitoring impurity driven high temperature corrosion of T91 by europium in LiCl–KCl molten salt. Pitting corrosion of T91 was observed, and they reported that the corrosion rate of T91 was increased with the duration of exposure and approached a steady state after 24 h.

4.3 Nickel based alloys

The corrosion of electroformed nickel (EF Ni) with and without nickel–tungsten (Ni–W) coating, 316L SS, and INCONEL 625 (Alloy 625) in molten LiCl–KCl salt in air for about 2 h was carried out by Ravi Shankar et al. (2010) at 400, 500 and 600 °C. The INCONEL 625 alloy showed superior corrosion resistance than other alloys, and the coated EF-Ni showed better performance than the uncoated EF-Ni in LiCl–KCl molten salt system. The authors reported that the formation of Cr-rich compound and the spallation could be the reason for the observed corrosion behaviour of INCONEL 625 and 316L. The better corrosion resistance of EF Ni–W was due to the formation of W-rich NiO layer. The corrosion behaviour of Ni based alloys like alloy 600, 625, 690 and alloy 800H have been studied in LiCl–KCl salt under air atmosphere for 2 h duration. Alloy 600 and 690 offered better corrosion resistance than alloy 650 and alloy 800H, and the presence of Mo in alloy 625 is not advantage for molten salt applications (Ravi Shankar et al. 2013a). The corrosion rates of all these materials in LiCl–KCl salt showed the increase of corrosion rate with temperature. Also, alloy 800H showed the highest corrosion rate compared to other alloys studied. Ravi Shankar and Kamachi Mudali (2018) studied the effect of Cl2 gas bubbling on the molten salt corrosion of INCONEL alloys 600, 625, 690 and their welds at 600 °C in LiCl–KCl melt. The authors reported that alloy 600 and 690 are more corrosion resistant than alloy 625, alloy 600 showed intergranular corrosion and alloy 625 showed interdendritic corrosion. Alloy 690 showed uniform corrosion in LiCl–KCl melt under Cl2 gas bubbling.

Kumar et al. (2018a) studied the effect of gaseous environments (Ar, O2, O2-0.1%SO2) on the behaviour of Ni alloys (Ni, β-NiAl, β-NiAl/Cr) in LiCl–KCl–Na2SO4 molten salt at 700 °C. It was clearly showed the effect of the gaseous environment surrounding the molten salt on the corrosion. In the oxidizing environment, Ni degraded quickly due to the instability of the NiO and showed that the formations of oxides during molten salt corrosion depending on the gaseous atmosphere. The additions of Al and Cr enhanced the corrosion resistance of the alloy in oxidizing environments.

4.4 Titanium based alloys

The stress corrosion cracking behaviour of the Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V studied in several molten salt systems (13 systems) including pure LiCl–KCl melt, nitrates, bromides, iodides, hydroxides and fluorides melts at different temperatures ranging from 80 to 450 °C in the open air and dry box conditions by Smyrl and Blackburn (1975). They reported that the influence of mechanical microstructure, metallurgical heat treatment on SCC are similar to that observed in aqueous systems and found that no effect of hydrogen in the form of H2O and H− in molten LiCl–KCl on crack extension. Wang et al. (2015) studied the hot corrosion behaviour of polycrystalline Ti3SiC2 in a eutectic mixture of LiCl–KCl salts for 100 h at 550 °C, 650 °C and 750 °C in air. They observed the better performance of polycrystalline Ti3SiC2 at 550 °C, and it corroded at higher temperatures by forming corrosion products such as TiO2 and Li2TiO3. It was concluded that the material exhibited better corrosion resistant at 550 and partially resistant at 650 and 750 °C due to the formation of protective oxide films. Magnus et al. (2021) reported the high temperature corrosion behaviour of Ti3AlC2 in LiCl–KCl molten salt under dry air atmosphere at 600 °C and reported the susceptible nature of the Ti3AlC2 to chloride salt and found that the selective leaching of Al from the matrix leaving behind the Ti3C2, and further the Ti3C2 converted to Ti3C2Cl2 by chlorination.

4.5 Ceramics, glasses and others

Sharma et al. (1976) studied the compatibility of AlN in LiCl–KCl saturated with Li, molten Li, Li saturated LiF–LiCl–KCl, molten 30 wt% Li2S–S and molten S at 400 °C for about 10,000 h, and LiCl saturated with Li and Cl2 saturated LiCl at 650 °C for up to 1430 h. They reported that no attack of AlN observed at 400 °C and AlN undergo an intergranular attack by Li at 650 °C. Sharma (1978) investigated the compatibility of BN cloth as a separator in lithium/iron sulfide cells at temperatures of 427–477 °C. The cloth was tested by placing it in LiCl–KCl electrolyte and carrying out charge-discharge cycles. During the charge–discharge cycles, slight corrosion of BN cloth and on static immersion tests in Li–LiCl–KCl melt severe corrosion was observed. Bandyopadhyay (1981) studied various ceramic and metallic coatings like CVD coatings of TiC, TiN, TiCN, TiB2 and rf-sputtered coatings of Cr, Mo, MoS2, MoSi2, Cr + TiN and TiC + TiN for Li-based battery cells by both in-cell and static corrosion tests in LiCl–KCl containing FeS2. Coatings performed well in the in-cell tests than the static corrosion tests. CVD TiC and TiN coatings showed better performance in these melts.

The corrosion of the Pyrex glass cells by the effect of Nd2+ ions in LiCl–KCl was observed during the UV–visible spectrophotometric measurements by Hayashi et al. (2004). The corrosion-resistant of the ZrN films obtained by plasma nitriding and electrochemical nitriding processes in LiCl–KCl melt has been studied at 450 °C by cyclic voltammetry by Goto et al. (2004). The thickness and N concentration of the nitride film found to be increased with the application of more positive potentials. Dusheiko (2001) reported the solubilities and degradation of cathodic sulfide materials like Fe, Ti, Cu, Al sulphides in LiCl–KCl and LiF–LiCl–LiBr melts for high temperature lithium batteries and concluded that the deterioration of these cathodic materials could be the principal cause for power sources self-discharge.

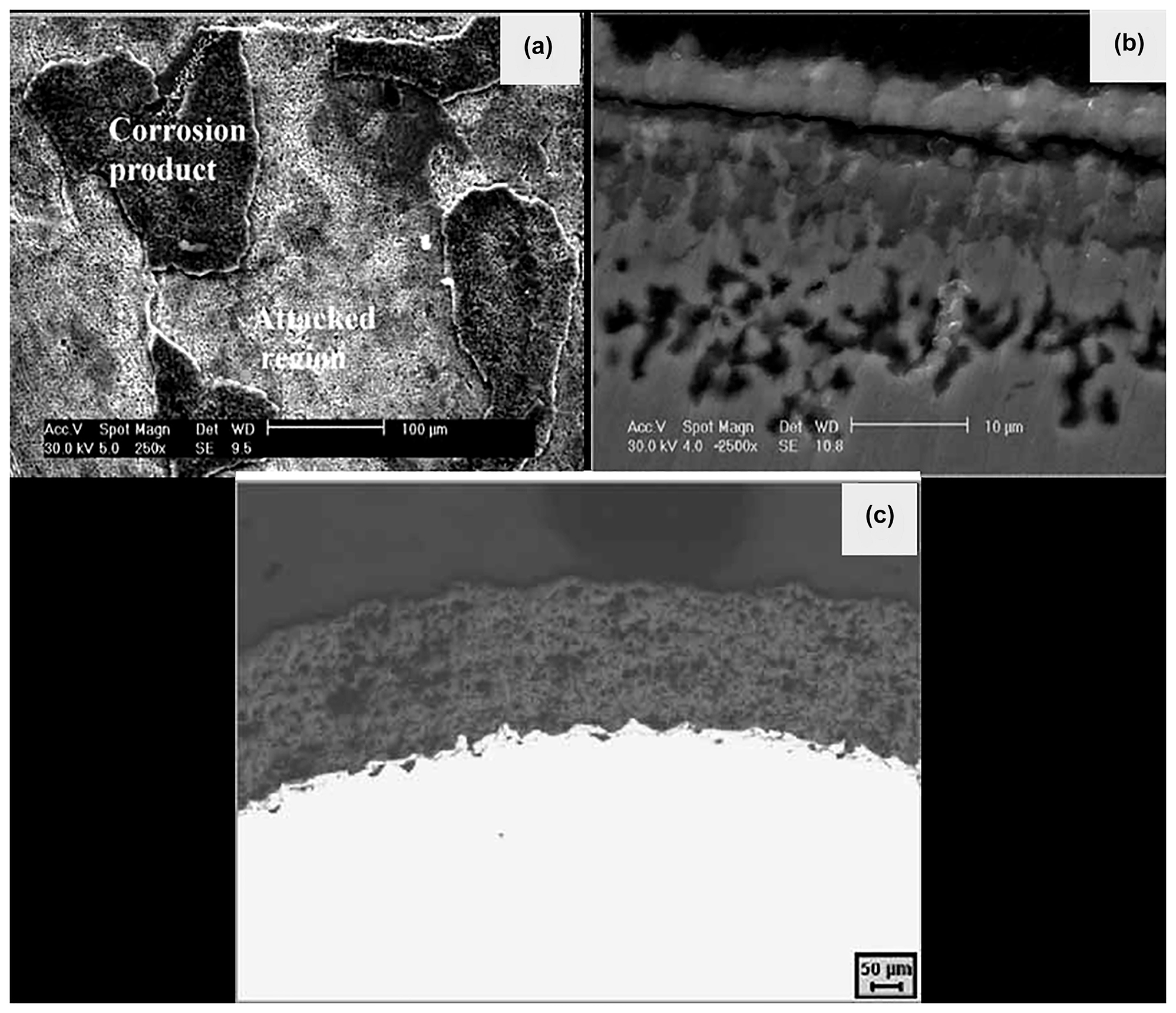

Ravi Shankar and Kamachi Mudali (2008) reported the corrosion behaviour of type 316L stainless steel in LiCl–KCl eutectic melt at 600 °C for about 250 h duration, and yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) coated 316L SS exposed for 1000 h to LiCl–KCl salt in argon atmosphere. They concluded that the severe corrosion of uncoated 316L SS sample (Figure 7) with selective diffusion of Cr to the top surface led to voids formation and also the formation of chromium compounds. The YSZ coated sample showed better corrosion resistance than the uncoated 316L SS. The SEM image of the 316L SS after exposure to molten salt, as shown in Figure 7a, indicates the formation of corrosion products and attacked (dissolution) regions. Dissolution and diffusion of elements in the alloy during corrosion led to the formation of voids, as seen from Figure 7b, and YSZ coated sample cross-section image (Figure 7c) indicated the better performance of the coating. Ravi Shankar et al. (2008) studied the corrosion behaviour of plasma sprayed yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ) coatings on type 316L stainless steel in LiCl–KCl salt at 600 °C for durations of 5, 100, 250 and 500 h in argon gas atmosphere. They also attempted the laser re-melting of the YSZ coating to consolidate the pores in the coating. They reported that the YSZ coated 316L SS did not show any corrosion attack and performed well. The laser melting of the coating resulted in large grains with segmented cracks while the coating defects reduced.

Corrosion behaviour of 316L SS in LiCl-KCl salt at 600 °C: (a) SEM image of the 316L SS exposed to molten LiCl–KCl eutectic salt for 25 h; (b) cross-section image of the corroded 316L SS for about 250 h, and (c) cross-section image of the YSZ coated 316L SS exposed to LiCl–KCl for about 1000 h. Reprinted with permission from John Wiley & Sons (Ravi Shankar and Kamachi Mudali 2008).

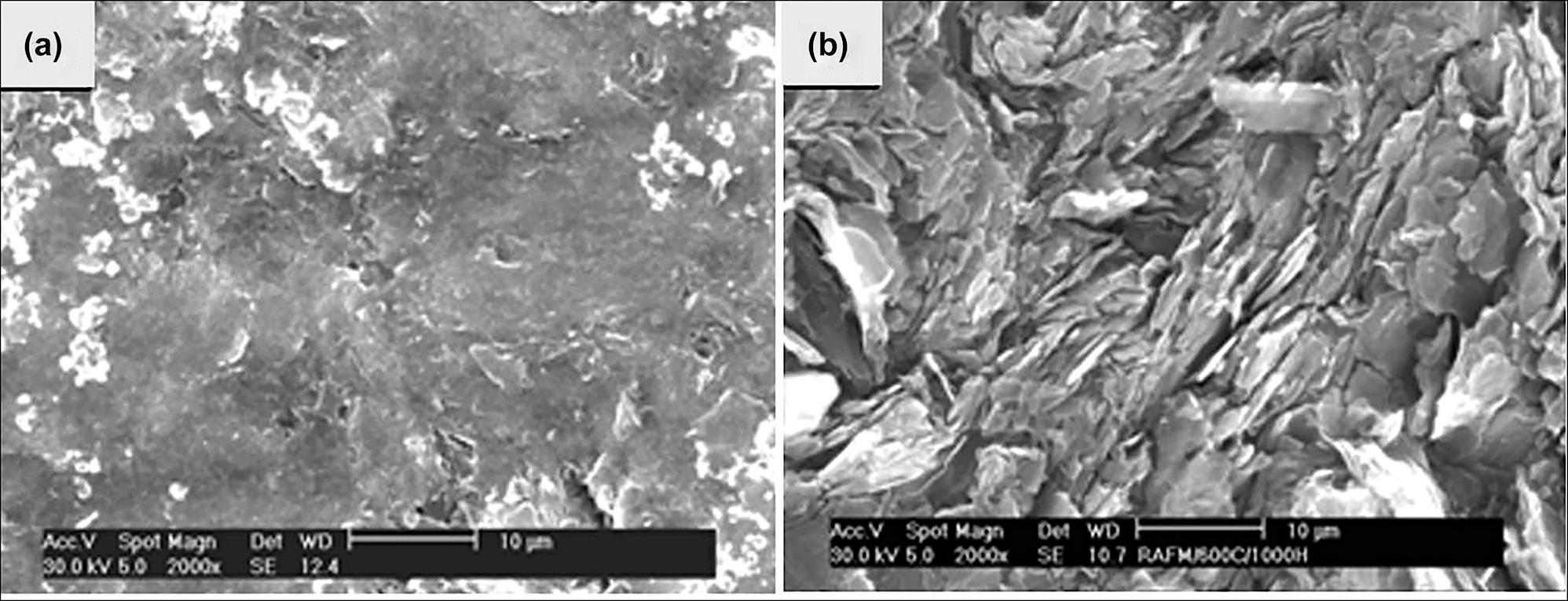

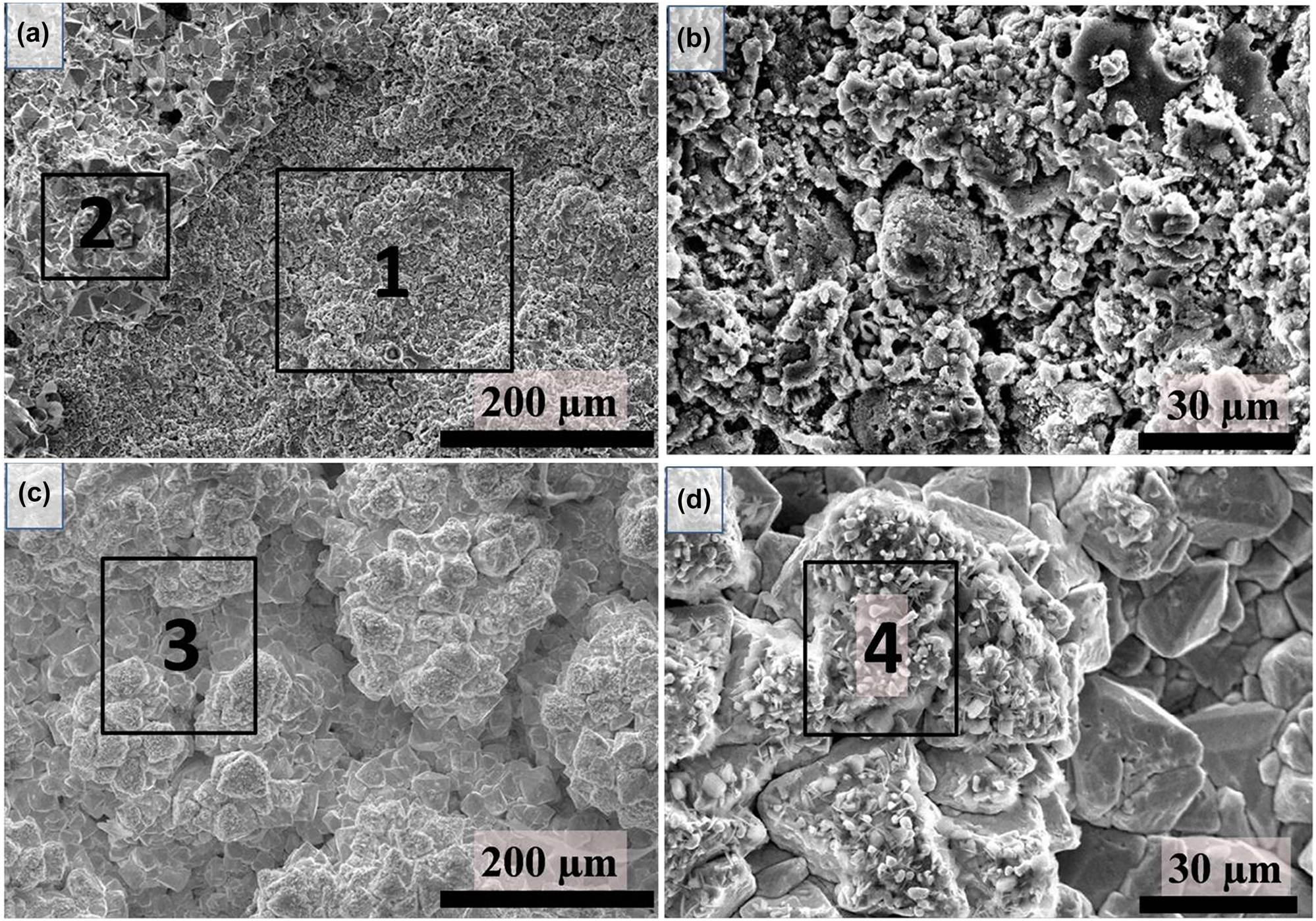

The corrosion studies of high density graphite (HDG) and plasma spray YSZ coated HDG in LiCl–KCl salt were carried out by Jagadeesh et al. (2012a, 2013b) for about 2000 h duration at 600 °C in argon atmosphere. The authors reported weight loss of HDG and weight gain of YSZ coated HDG during corrosion test in molten salts and concluded that YSZ coated HDG showed excellent corrosion resistance to molten LiCl–KCl salt. The surface attack of the HDG can be visualized in the SEM images (Figure 8) of the HDG surface before and after 2000 h immersion in LiCl–KCl salt. It clearly shows the removal of graphite particles from the surface due to the salt penetration into the pores of the graphite material. Jagadeesh et al. (2013a) studied the corrosion behaviour of yttria coatings developed by pulsed laser deposition on high density graphite in LiCl–KCl molten salt at 600 °C for about 3 h in argon atmosphere. It was reported that yttria coating offered better protection to HDG from the attack by molten salt during these short-time exposure to molten salts studies.

SEM images of (a) as received and (b) corrosion tested HD graphite in molten LiCl–KCl salt at 600 °C for about 2000 h. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier (Jagadeesh et al. 2012a).

Jagadeesh et al. (2016) studied the corrosion behaviour of laser melted plasma-sprayed alumina-40 wt% titania coatings on HDG in LiCl–KCl molten salt at 600 °C for about 24 h duration in argon atmosphere. The authors reported the improvement of corrosion-resistant of the coatings after laser melting at various laser powers ranging from 6.4 to 8 W.

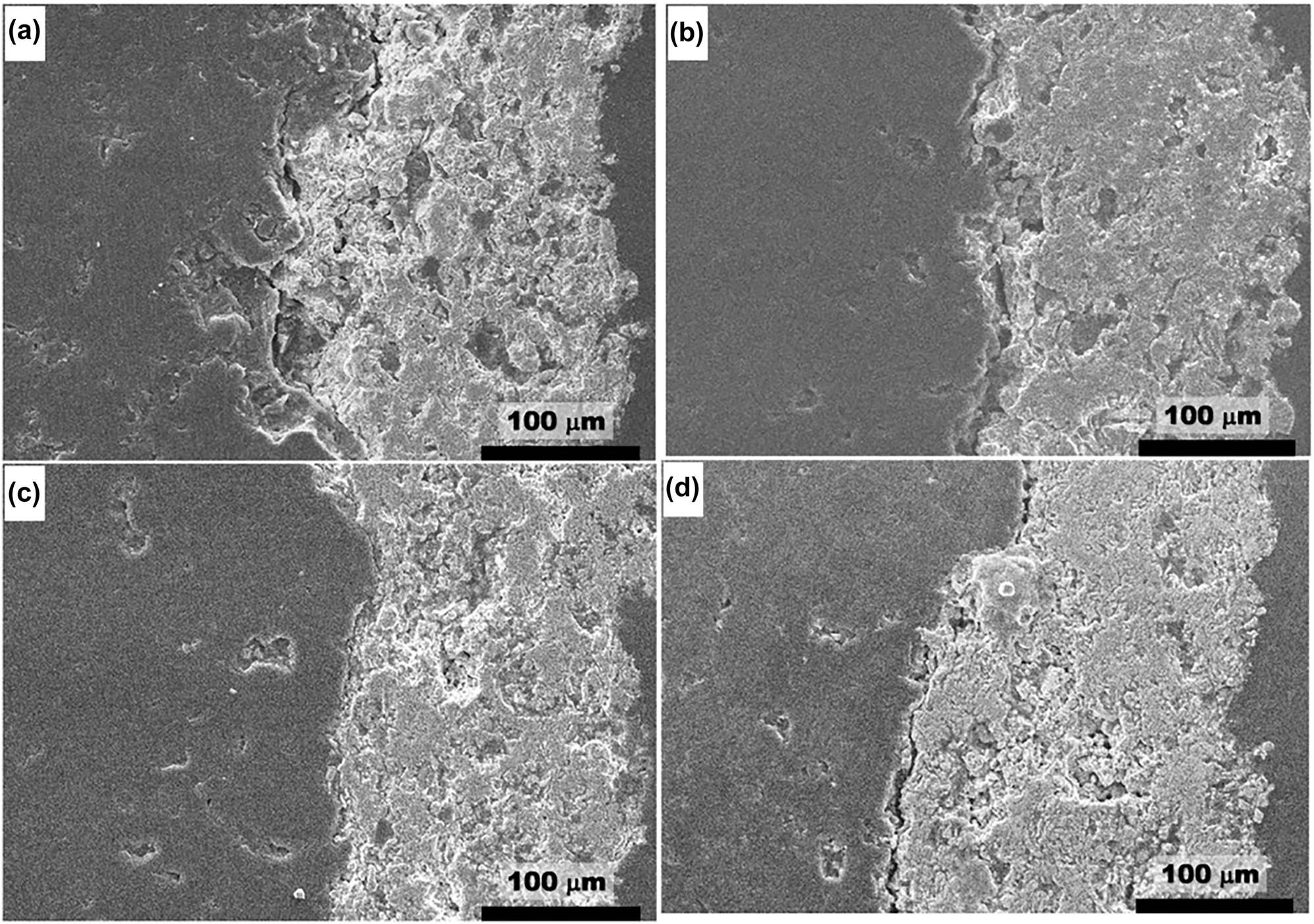

Barnett (2017) tested high temperature corrosion of engineering alloys in molten chlorides, LiCl–KCl, and reported that the main attack by molten salts occurred at the salt-air interface in the splash zone. The author observed that Alloy 625 corroded by pitting and intergranular attack by molten salt. Stainless steel 310, P91 and alloy 625 were corroded heavily in this molten chloride salt. Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2017b) studied the corrosion behaviour of 9Cr–1Mo steel coated with plasma sprayed YSZ coatings in UCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt at 600 °C for durations of 100, 500, 1000 and 2000 h. It was reported that even for exposure up to 2000 h duration, there is no delamination or deterioration of the YSZ coating in molten salts. Figure 9 shows the surface morphology of YSZ coated 9Cr–1Mo after exposure to molten salt for 1000 and 2000 h duration. There is no attack of molten salt seen, the surface was dense without any cracks in the coating, and some salt deposits were seen (Figure 9). The EDS elemental analysis of these deposits confirmed the presence of uranium, indicating the presence of UCl3. In this melt, the authors also studied the uncoated 9Cr–1Mo steel, and reported severe corrosion of 9Cr–1Mo without coating (Jagadeeswara Rao et al. 2017a).

Surface morphology images YSZ-coated 9Cr–1Mo steel after exposure to UCl3–LiCl–KCl molten salt at 600 °C for (a) and (b) 1000 h; (c) and (d) 2000 h. Reprinted with permission from Springer Nature (Jagadeeswara Rao et al. 2017b).

The high temperature corrosion of YSZ coated HDG in molten LiCl–KCl salt at 600 °C was tested by immersion studies for durations ranging from 50 to 3500 h in argon atmosphere by Jagadeeswara Rao et al. (2018a). The plasma sprayed YSZ coated HDG rods with and without SiC interlayer coating were tested for a maximum duration of 3500 h and found no delamination or failure of the coating for both the samples. The SEM cross-section images of the coated samples after the corrosion test (Figure 10) show no loss of the coating observed even after 3500 h exposure, and also the top surface is still rough, as seen in the cross-section image. YSZ coating proved to be the best coating for the molten LiCl–KCl applications.

SEM cross-section images of the YSZ coated HDG rods with SiC interlayer coating after exposure to molten salt: (a) Exposed for 50 h; (b) for 500 h; (c) for 2000 h and (d) for 3500 h duration. Reprinted with permission from Springer Nature (Jagadeeswara Rao et al. 2018a).

The corrosion behaviour of 2.25Cr–1Mo steel, 9Cr–1Mo steel, Ni-based alloy 600, Ni-based alloy 625, Ni-based alloy 690 and partially stabilized yittria (PSZ) coated materials in molten LiCl–KCl eutectic salt at 600 °C in argon atmosphere was studied by Ravi Shankar et al. (2013b). Based on the weight loss observations during the corrosion, it was reported that the PSZ coatings showed better corrosion resistance compared to Ni based alloys, followed by 9Cr–1Mo steel and 2.25Cr–1Mo steel and observed preferential leaching of Cr. Kumar et al. (2018b) studied the electrochemical nature of molten sulfates in LiCl–KCl–Na2SO4 at 700 °C at W, Pt and glassy carbon working electrodes to know about the melts oxidizing power on corrosion of metals. The authors reported that presence of stronger oxidants such as O2 and SO3 under oxidizing atmosphere, and the reduction of these oxidants occur at more positive potentials than sulfate ions leading to the corrosion of metals or alloys exposed to the salt.

Chang et al. (2022) recently reported the effect of EuCl3 on the corrosion of Haynes C276, Inconel 600, Incoloy 800 and 316L stainless steel in molten LiCl–KCl salt at 500 °C by static immersion experiments for 24 h duration and also by electrochemical measurements in Ar filled glove box with less than 0.01 ppm of moisture and 1 ppm of oxygen. Rapid dissolution of Fe, Cr and Ni were observed in all the alloys. The corrosion rates of the alloys are found to be 2 orders of magnitude higher than in LiCl–KCl salt due to the presence of 2 wt% EuCl3.

Guo et al. (2018) reviewed the corrosion studies of various materials in molten fluoride and molten chloride salts for nuclear applications. The review dealt with the molten salt properties, molten salt corrosion fundamentals, molten salt corrosion of materials in fluoride and chloride salts and corrosion mitigation.

The key findings from the above literature review and from Tables 2 and 3 are as follows: the corrosion of materials under non-isothermal condition was higher compared to isothermal studies; in most of the cases it was observed that dissolution of the alloying elements at the hot zone and redeposition at the colder zones, which led to the formation of corrosion product regions along with dissolution regions on the exposed alloys; it was also found that the increase of molten salt corrosion with increase of temperature. Stress corrosion cracking was also observed in some cases like in Ti–8Al–1Mo–1V (Table 2); it was also reported that an increase of molten salt corrosion with the presence of O2 in the melt/atmosphere (Table 3); in several studies, it was observed that the non-protective nature of the initially formed oxide layers during molten salt corrosion, however, in oxide ions rich melts like in LiCl–KCl–Li2O, passivation of the metals/alloys were observed (Table 3); pitting corrosion (Table 2) was also observed in Ni, Ni based alloys and in stainless steels exposed to molten salts containing oxide ions at different temperatures; the presence of Ni and Mo found to be advantages in 316L SS against molten salt corrosion. However, it was reported that the presence of Mo in alloy 625 is inferior against molten salt corrosion; among the graphite materials, pyrolytic graphite showed better corrosion resistant against molten salt corrosion; intergranualar corrosion, pitting corrosion was observed in case of nickel based alloys. The molten salt corrosion behaviour of yttria, alumina and YSZ ceramic coatings on different structural materials has been reported. It was reported that YSZ coatings showed better corrosion resistance against molten LiCl–KCl salt. Limited studies have been carried out on the corrosion behaviour of intermetallics, lanthanides and the effect of the addition of various cations in the melt as seen from Tables 2 and 3 (Barraza-Fierro et al. 2012, 2015; Chang et al. 2022; El’kin and Kovalevskii 2011).

5 Understanding the corrosion of molten LiCl–KCl salts

As evidenced from the Gibbs energy of formation of various metals chlorides, the alkali and alkaline earth metal chlorides are thermodynamically favoured over the transition metal chlorides. Most of the alloys of the structural materials are made of transition metals (Sridharan and Allen 2013). So it is not expected that the metals would react with the LiCl–KCl salt and forms their corresponding metal chlorides. Hence, theoretically, no corrosion should occur when an alloy or metal is exposed to molten LiCl–KCl eutectic salt. However, corrosion occurs in real applications. The corrosion of various alloys in molten chloride salts could be due mainly to impurities (Fernández and Cabeza 2020; Sridharan and Allen 2013). The impurities in the molten chloride salts can be moisture, dissolved oxides or metal ion impurities. Generally, the corrosion of the alloys in molten salts or any other medium will be controlled by the presence of oxidants. The presence of oxidants like H2O, OH−, O2 and H+, are mainly attributed to the corrosion of materials by molten chlorides salts. These oxidant impurities in the molten salts can appear during the synthesis of the salts and can also be from the storage of molten salts. These oxidants can enter the molten salts during storage through the environment or from storage container materials. So the molten salt corrosion is led by the impurities present in the salt but not purely from LiCl–KCl salt. Thereby, various methods are available to purify the molten salts before their use. So one needs to ensure the molten salts are synthesized and stored with proper care, and are purified to remove the maximum extent of impurities like moisture, other metal ions, etc. before use. Also, one must ensure that the chloride molten salts are used in an inert gas atmosphere with fewer impurities, like oxygen, moisture, etc.

In general, molten salt corrosion of structural materials is an electrochemical process. During molten salt corrosion of metals, anodic dissolution of the metals or alloying elements and cathodic reductions of the various oxidant impurities occurs simultaneously (Guo et al. 2018). The oxidants are also other metal ions present in the molten salt (like elements from structural materials, fission products, etc.). So the overall corrosion reaction can be written as given below in equation (3).

where M represents metal, Ox and Red represents oxidant (impurities) and reductant, respectively. To occur the reaction spontaneously (corrosion of metal), the Gibbs free energy of the net reaction should be negative. The following equation (4) provides the relation between the thermodynamic quantity, Gibbs free energy (ΔG) and electrochemical parameters, E.

where, ΔG, n, F are the Gibbs free energy change of the net reaction, number of electrons exchanged in the reaction and Faraday constant, respectively. E represents the reduction potentials difference between cathodic and anodic half-reactions (Ec − Ea). If E is positive, then the Gibbs free energy will be negative, and the overall reaction occurs spontaneously in the forward direction (corrosion). For E to become positive, Ec should be positive. Hence, the cathodic half-reaction would control the overall direction of the net reaction, corrosion reaction. As mentioned earlier, the reduction reactions of the oxidants (impurities) present in the molten salt are responsible for the extent of corrosion of materials in these salts. If the impurities are foreign metal ion impurities present in the melt, then the knowledge of the reduction potentials of those metal/metal ion helps in finding out the extent of corrosion. If the metal ion impurity’s reduction potential is more positive, the exposed alloy to the molten salt would corrode because of more cathodic reactions.

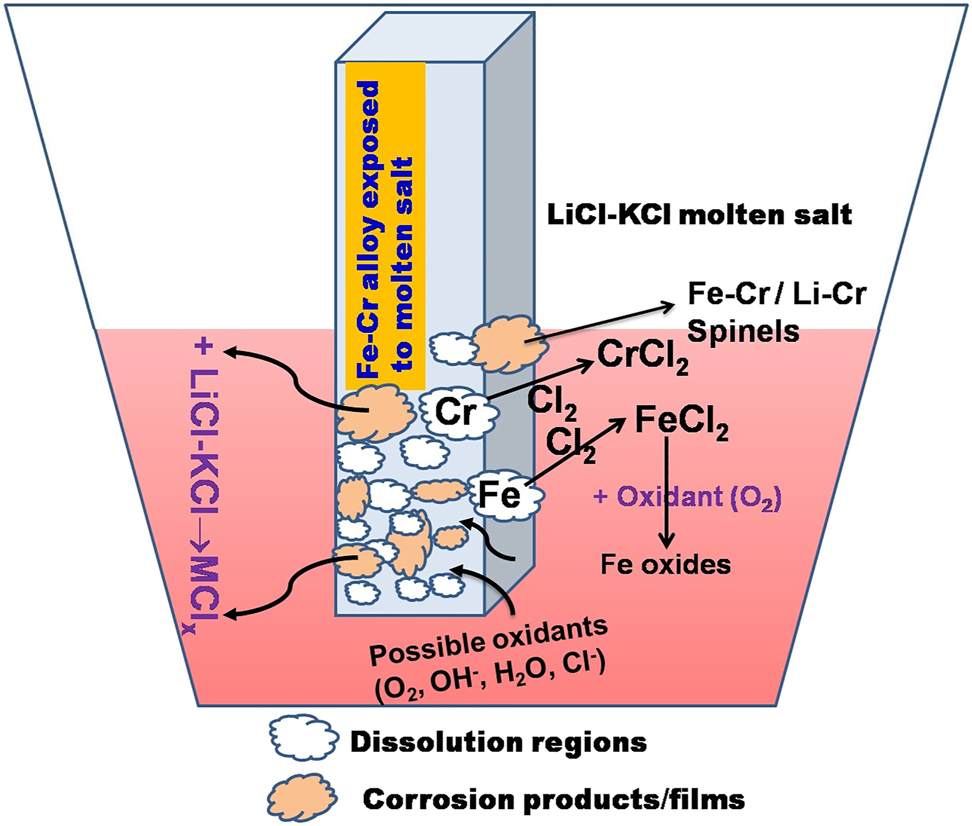

Generally, in molten salts, the corrosion occurs in two main ways (i) oxidation of the constituent elements of the alloy and (ii) dissolution of the alloying elements in the molten salts. If the salt contains a more oxidizing environment, the first process occurs and forms some oxide layers over the surface. But it was seen that these passive oxide films were unstable. These films are further attacked by molten salts. On the other hand, the metal dissolves in the form of metal chlorides. Dissolution of the specific alloying elements was observed as the primary corrosion in molten chloride salts at high temperatures (Kane 2003). In addition to this, the leaching (dissolution) of the alloying elements was observed, followed by deposition of the same by forming corrosion products at other places of the alloy surface due to the thermal gradient in the molten salt. The alloying elements that are less noble than other metals dissolve at hotter regions compared to the colder regions and redeposit or collect in colder regions, which can lead to the fouling of the system (Harper and Lai 2001). The corrosion process of a typical Fe–Cr alloy by molten salts is depicted in Figure 11.

Typical corrosion processes occur at the alloy when exposed to molten LiCl–KCl eutectic salt at high temperatures.

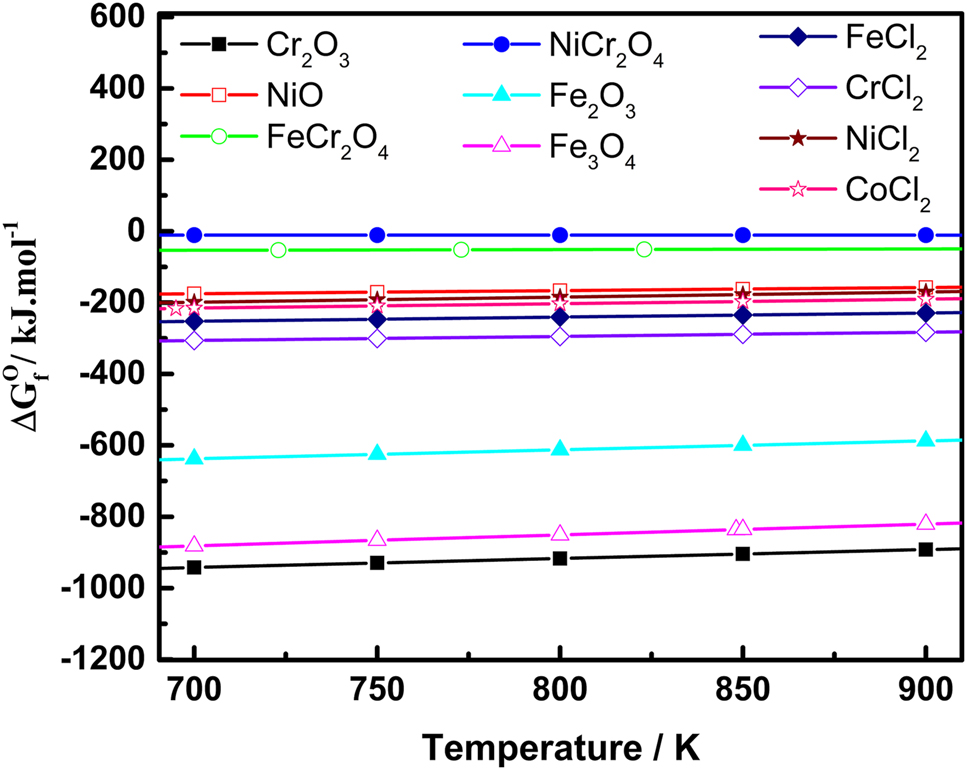

Figure 12 provides the standard Gibbs free energy of formation of various types of products at different temperatures. The Gibbs free energy data has been calculated by using FactSage software for some of the reactions. All the possible reactions given in the Figure 12 showed negative Gibbs free energy of formation. This indicates the possibility of formation of these compounds during corrosion process, if the corresponding reactants and conditions exist. There is a feasibility of formation of oxides and spinels if the atmosphere or the molten salt contains oxidants like O2. Also there is a possibility of formation of the metal chlorides as shown in the Figure 12. The reaction with a higher negative Gibbs free energy value has more tendencies to react than the reaction having less negative Gibbs free energy. Hence, it is more possible to form chromium oxide compared to iron and other oxides in the alloys containing Cr and Fe. The Gibbs free energy of formation of these compounds at 600 °C is provided in Table 4 along with their reactions of formation. As seen from Table 4, most of the reactions are feasible at 600 °C, and obviously, there is a more chance of formation of these compounds if the corresponding reactants available in the melt. As discussed, if oxygen exists in the system, the exposed alloy forms the oxides of the corresponding elements based on the type of alloy. For example, most steels form Fe2O3, Fe3O4 and Cr2O3 initially. But these oxides further react and form the less stable compounds like LiCrO2, etc. or these oxides can react and forms the corresponding metal chlorides.

The standard Gibbs energy of formation of various compounds at different temperatures.

The standard Gibbs energy of formation of various compounds at 600 °C.

| Reaction |