Abstract

The conceptual characterization of word classes has been a central topic in cognitive linguistics since its inception. However, compared to major classes such as nouns and verbs, minor word classes have received less attention. This study discusses the conceptual basis of prepositional phrases, especially focusing on prepositional complements of prepositions (hereafter, PCOPs) – a syntactically irregular but widely-used structure in English (e.g., from within the company, from behind the table, since before the war). The aims of this paper are threefold: (1) to demonstrate the relative prevalence of PCOPs in English through an extensive study of the British National Corpus; (2) to identify two distinct functions of PCOPs – the Emphasis Type and the Search-domain Type; and (3) to characterize the conceptual basis of PCOPs, highlighting the conceptual similarities between PCOPs and (countable) noun phrases, and thus to explain the occurrence of PCOPs in slots where we normally find noun phrases. We also show how the analysis could be extended to another type of nominal prepositional phrases, i.e., prepositional subjects. By explaining the distribution of PCOPs (and prepositional subjects) in this manner, we underscore the necessity of a conceptual characterization of word classes in linguistic research.

1 Introduction

The present paper discusses prepositional complements of prepositions (hereafter, PCOPs), illustrated by examples (1a–d), below.

| The project team was chosen from within the company. |

| Something had crawled from under a bottle of Altbier. |

| …the moon came out from behind a cloud. |

| …it was not completed until after his death. |

As noted in several descriptive grammars of English (Huddleston and Pullum 2002; Quirk et al. 1985), PCOPs are not a typical use of prepositional phrases in that they complement another preposition, when normally of course a noun phrase occupies that slot (e.g., at the desk, in the town and on the day). They are nevertheless widespread in English. We offer a cognitive linguistic explanation as to why PCOPs, despite their syntactic irregularity,[1] are nevertheless perfectly acceptable.

The aims of this paper are threefold. The first aim is to illustrate the widespread use of PCOPs in Present-day English. We carry out extensive research of the British National Corpus (hereafter, BNC; see Aston and Burnard 1998) in order to identify frequent PCOP patterns, identify prepositions appearing in PCOPs, and discuss some general characteristics concerning their usage, including the conceptual domains designated by PCOPs, which previous scholarship has succeeded in doing only partially. The second aim is to discuss, in more detail the functions of PCOPs in their contexts. We identify two distinct functions of PCOPs: the Emphasis Type and the Search-domain Type. The third aim, finally, is to discuss the conceptual basis of PCOPs and to show how this accounts for the acceptability of this syntactically irregular pattern. We will show that there is a common conceptual basis between the two functional types. Moreover, taking a Cognitive Grammar perspective on the semantics of word classes (Langacker 1987) we will demonstrate that PCOPs are conceptually similar to (countable) noun phrases. It is this similarity, we will argue, which motivates the use of PCOPs. We also suggest that prepositional subjects, whilst not the focus of our paper, lend themselves to a similar, conceptually-based analysis. We address these three aims in Sections 3–5, respectively. Section 2 discusses previous studies, identifying typical and less typical uses of prepositions, whilst also giving an overview of how word classes have been analyzed in cognitive linguistics. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the discussion and emphasizing the necessity of (at least partially) conceptual characterizations of word classes.

2 Previous studies

This section starts with a brief review of the basic characteristics of prepositions in Section 2.1. Section 2.2 discusses less typical uses, including PCOPs and prepositional subjects. Section 2.3 summarizes cognitive approaches to word classes.

2.1 Basic characteristics of prepositions

Prepositions are a well-known major word class in English. The definitions from two major dictionaries may serve to illustrate their basic characteristics.

| A word that connects a noun, a noun phrase, or a pronoun to another word, esp. to a verb, another noun, or an adjective (Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary) |

| A function word that typically combines with a noun phrase to form a phrase which usually expresses a modification or predication (Merriam-Webster Dictionary) |

As shown in (2)–(3), one fundamental characteristic of a preposition is to take a noun phrase or a pronoun as its complement, forming a prepositional phrase, and then, to combine it with a verb, a noun, or an adjective. These common patterns are summarized and exemplified in (4).

| Patterns: | {verb/noun/adjective} | + preposition + | {noun/noun phrase/pronoun} |

| complements | |||

| Examples: | refer to the paper, | a friend of mine, | fond of people |

| verb | noun | adjective |

The definition in (3) also shows another characteristic of prepositions: their use in phrases whose function is modification or predication, as in (5), below.

| modification: a pen on the desk, the center of the city, a man in his sixties, |

| predication: He is now at school, She is in hospital, John broke the vase to pieces. |

In (5a), the italicized prepositional phrases modify the preceding noun phrases, while in (5b), the italicized prepositional phrases predicate the state of participants (he, she and the vase), functioning as complements of the verbs. Another use of prepositional phrases is adverbial, as in We met in August, where the underlined prepositional phrase describes the setting of the event described by the clause.

These basic characteristics of prepositions are also captured in the conceptual characterization of word classes offered by Cognitive Grammar. Langacker discusses prepositions as highlighting some aspect of the relation between two entities, the trajector and the landmark,[2] noting that “the prepositional object (e.g., in August; under the bed; with a screwdriver [emphasis original])” expresses “the landmark” (2008: 117). As for the trajector, Langacker argues that “prepositions are indifferent as to the nature of their trajector” (ibid.: 117). When its trajector is a thing (in Langacker’s technical sense of the term, i.e., “a region in some domain”, 1987: 189), the prepositional phrase is classified as adjectival, while when its trajector is a relation (i.e., “a set of interconnected entities”, Langacker 1987: 214), the phrase is regarded as adverbial (see Langacker 2008: 117). Furthermore, he suggests that “the landmark functions as a reference point for purposes of finding [the trajector]” (Langacker 2009: 25). Here, the search domain is defined in relation to this reference point as a limited region within which the trajector can be found (as for the reference point ability, see Langacker 1993).[3]

2.2 Less typical complements of prepositions

Having discussed typical uses of prepositions, we now turn to unusual ones. In Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 598), a preposition is defined as “a word that governs, and normally precedes, a noun or pronoun and which expresses the latter’s relation to another word” (emphasis added). As indicated by the word “normally” in the citation, a preposition can also be followed by constituents that are not noun phrases and pronouns, though less commonly. Some examples from Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 599) are given in (6), below:

| The magician emerged [from behind the curtain]. [PP] |

| I didn’t know about it [until recently]. [AdvP] |

| We can’t agree [on whether we should call in the police]. [interrogative clause] |

| They took me [for dead]. [AdjP] |

While nominal complements may follow all kinds of prepositions, these less typical complements show selectional (or collocational) restrictions: different prepositions license different types of complements.[4] One less typical kind of complement is the main topic of this paper: prepositional complements of prepositions (PCOPs), exemplified by (6a) and (1a–d), above.

In reference grammars of English, discussion of PCOPs is remarkably limited. Most grammars completely exclude them altogether (e.g., Biber et al. 1999; Swan 2005; Carter and McCarthy 2006). Huddleston and Pullum (2002) is one exception, but, although they perhaps provide the most detailed description of PCOPs of all reference grammars, they only note that “the head prepositions are usually from, since, till, and until, and the head preposition only has spatial or temporal meanings” (ibid.: 640). As we show below, this description far from captures the full picture of PCOPs. Moreover, it includes a misrepresentation of the range of possible meanings of the head preposition: in addition to spatial and temporal meanings it can carry a quantity or more abstract meaning as well, as in That adds up to over 50 million a year and He was chosen from within the team, respectively.

PCOPs have also not received much attention in studies other than reference grammars, except in Otani (2015, 2019, 2023) and Otani and Willem (2025). One study that does cover PCOPs is by Jaworska (1986), who combines prepositional subjects and PCOPs in her discussion. She offers the examples of prepositional subjects in (7), below.

| Across the road was swarming with bees. (Jaworska 1986: 355) |

| By air seems to be quite cheap. (Jaworska 1986: 360) |

| Under the chair attracted the cat’s attention. (Jaworska 1986: 357) |

Jaworska (1986: 356) also provides some examples of PCOPs, including the ones in (8), below.

| He crawled out from under the table. |

| Food had been scarce since before the war. |

She argues that prepositional phrases appearing in the subject position and the complement position must be referential, and their “presence must be justified either by the lack of an NP with the same meaning as the PP”, as per (9), below, “or by matters of style” (ibid.: 359).

| Hecrawled out from under the table. |

| *He crawled out from (the) undertable. |

| He crawled out from the table. |

According to Jaworska (1986), (9a) is possible since there is no noun that illustrates the region under the table such as in (9b). In other words, (9a) is possible since the region under the table cannot be straightforwardly illustrated by a noun phrase. We consider Jaworska’s observation to be valuable, but go further than she has, by proposing a reason as to why nouns such as “undertable” do not exist (see Section 4.2). In that respect, our study offers a deeper explanation of the phenomenon of PCOPs.

A prominent characteristic of both prepositional subjects and PCOPs is their occurrence in typical noun phrase positions, Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 646) give the following examples of prepositional subjects:

| Over a year was spent on this problem. (Huddleston and Pullum 2002: 646) |

| Before the end of the week would suit me better (Huddleston and Pullum 2002: 646) |

According to Huddleston and Pullum (2002: 646), “in the case of the [prepositional] subject, the verb is usually be, in either its specifying or its ascriptive sense”, as in (10a), “but a restricted range of other verbs are also possible” as in (10b).

Jaworska (1986: 359) claims that a high degree of precision in terms of the reference of the object of the preposition enhances the ease of interpretation of the sentence, as in the increasingly precise noun phrases in (11a–c), the suggestion being that (b) is easier to interpret than (a), and that (c) is easier than (b). Her observations appear to apply to prepositional subjects; not necessarily PCOPs.

| Until Christmas was planned in detail. |

| Before Christmas was planned in detail. |

| Just before Christmas was planned in detail. |

Descriptions and analyses in previous studies have identified important aspects of the use of prepositional phrases in the irregular subject and prepositional complement positions. However, these accounts have generally been based on invented examples and subjective judgments. In this paper we set out to explain why prepositional phrases may be licensed in these syntactically irregular positions by focusing on authentic, corpus-based examples of PCOPs, but our explanation can be extended to prepositional subjects as well.[5]

2.3 Approaches to word classes

One of the fundamental tenets of cognitive linguistics is that word classes can be characterized conceptually (e.g., Langacker 1987; Talmy 2000). In the generative and structuralist tradition, by contrast, word classes are generally defined in terms of abstract syntactic features such as +/−N and +/−V (e.g., Chomsky 1970) and/or distributional (morphological and syntactic) criteria (e.g., Palmer 1971). However, research in 1980s began characterizing word classes semantically, discursively and conceptually (e.g. Hopper and Thompson 1984; Langacker 1987; Talmy 1985; Wierzbicka 1985). These studies succeeded in offering plausible conceptually-based characterizations of word classes. Langacker (1987), whose work we draw on especially heavily in this study, characterizes nouns as symbolic units whose semantic pole specifies that they are “things”; the semantic pole of verbs, on the other hand, is “process”. For a definition of what exactly he means by “things”, see (36). He actually goes even further, by identifying some surprising conceptual similarities between subcategories often made within the noun and verb categories. Specifically, in pointing to parallels in boundedness and homogeneity, he reveals striking conceptual similarities between mass nouns and imperfective verbs on the one hand, and between count nouns and perfective verbs on the other (Langacker 1987, 2008: 153). Langacker (1987) also provides conceptual characterizations of other typologically less salient word classes – such as adjectives, adverbs, prepositions, and participles – as symbolic units whose semantic poles designate “atemporal relations.[6]” However, compared to nouns and verbs, which have been discussed extensively and in depth, as in Langacker (1991), the conceptual characterization of these other word classes has been less explored.

Croft (2001) has expanded on the conceptualist view of word classes by looking not only at their lexical semantics but also their propositional act function, i.e., the discourse role they (or the phrases they head) play in the context of the wider clause. Thus, nouns are seen not only as object words, but object words used to refer; verbs not just as action words but action words that predicate, and adjectives not just as properties but property words in a modifying function. He also argues that “word classes (and other syntactic structures) are language-specific and construction-specific,” as they are defined distributionally, by the occurrence of the words in a particular construction within a given language. This implies that a single word class may serve different functions depending on the constructions in which they occur (see Croft 2023 for further discussion).

Yet more recent cognitive linguistic research on word classes has focused also on what Langacker labels the other “pole” of the symbolic units represented by word classes: i.e., their phonology. Building on substantial empirical work in psycholinguistics, Hollmann (2012, 2013) conducted psychological experiments to test phonological characteristics of nouns and verbs such as number of syllables, word length, voicing, stress, and so on. He identifies a number of phonologically partially specific sub-schemas of nouns and verbs. These may be more salient than the highly abstract super-schemas of nouns and verbs proposed by Langacker, which lack this phonological detail, but there is no suggestion that those super-schemas may not exist, and in any case the suggestion in Hollmann’s work is that the more specific subschemas share their semantics with those noun and verb superschemas.

Although these studies in cognitive linguistics have supported the hypothesis that word classes can be characterized (at least in part) conceptually, they have tended to focus on the two universally observed categories (i.e., nouns and verbs), and adjectives (for the latter, see also Hollmann 2021). Other word classes such as those that profile atemporal (or non-processual) relations have received less attention. Prepositions are one of these less typical classes. The special uses of this category that we categorize under the label PCOP are the main topic of this paper. We will extend Langacker’s work on other word classes to cover also PCOPs, and in so doing explain why despite their syntactic irregularity they are nevertheless acceptable.

3 Initial characterization of PCOPs

This section describes in detail the behavior and meaning of PCOPs in contexts, based on occurrences of PCOPs in the BNC. We present a list of frequent PCOPs in 3.1, while in 3.2 we describe their characteristics, such as their meanings and most common head prepositions.

3.1 Collecting instances of PCOPs

As we have observed, above, PCOPs have not received much scholarly attention; it is therefore not surprising that their different uses have not yet been described. To address this gap in the literature we collected corpus instances of PCOPs, and create a list designed to act as a solid empirical basis for a general overview.[7]

Having differentiated between PCOPs and other sequences of prepositions we can turn to collect examples of PCOPs. To make a list of PCOPs, we searched for them in the BNC and also identified examples in existing scholarship to complement the investigation. The procedure consisted of two steps:[8]

Identify PCOPs from invented examples in existing scholarship, confirming whether they occur in the BNC as well, and including them if that is the case.

In Step 1 we looked for ‘preposition-preposition’ sequences that were headed by 45 basic prepositions (Altenberg and Vago 2010: 65). As a result, we found 114 sequences that appear over 30 times in the BNC. However, these 114 combinations include many false positives of PCOPs. Therefore, we checked all 114 sequences manually, which yielded 38 PCOP types.

Let us look a little more closely at some false positives. Clearly, not all preposition-preposition sequences are instances PCOPs. Specifically, in PCOPs the second prepositional phrase functions as the complement of the first preposition. The structure of PCOPs could be characterized as in (12).

| [PP preposition [PP preposition [NP noun phrase]]] |

This definition excludes preposition-preposition sequences where that head-complement relation does not obtain, as in (13), below.

| I will actually be working to [VP start with] [PP in this area here]. |

| Such diagrams are graphically [VP referred to] [PP as s-plane diagrams]. |

The prepositional phrases in (13a–b) do not function as complements of the prepositions that precede them, as indicated by the brackets; rather, they function as a setting of the sentence in (13a) and an adjunct in (13b). Since the bracketed prepositional phrases are not inseparable parts of the phrases headed by preceding prepositions, they can be used as the focus in the cleft construction, as in (14).

| It is in this area here that I will actually be working to start with. |

| It is as s-plane diagrams that such diagrams are graphically referred to. |

Unlike the examples in (13), PCOPs cannot be used as the focus in the cleft construction since they are inseparable parts of the phrases headed by the prepositions that precede them.

Table 1 shows the results of the manual selection.

38 common PCOP types and their token frequencies found in the BNC.a

| from behind | (610) | from within | (587) | at about | (477) | from under | (472) |

| to about | (333) | from around | (283) | to within | (271) | from among | (233) |

| from across | (217) | for about | (212) | from beneath | (180) | for over | (168) |

| at between | (161) | to between | (155) | for between | (131) | at around | (128) |

| at from | (125) | from between | (115) | from about | (110) | across to | (96) |

| from beyond | (77) | from amongst | (73) | from outside | (73) | about at | (68) |

| from throughout | (67) | from off | (62) | from over | (62) | from on | (58) |

| from before | (53) | with between | (48) | from up | (42) | with about | (40) |

| to over | (39) | from down | (38) | with over | (35) | from beside | (33) |

| to around | (32) | to under | (31) |

-

aSince we only included the 45 basic prepositions mentioned in Altenberg and Vago (2010), we excluded any preposition-preposition sequence headed by like and as, although those can be used prepositionally. We also excluded idiomatic phrases such as How about in the town? and What about in a previous life?

Being based on a corpus search, Table 1 naturally does not include false negative examples; PCOPs that are used less frequently in the BNC are excluded from the list. For example, it does not include some examples mentioned in previous studies such as the example in (1d). In order to link as best as possible with existing scholarship on PCOPs, we collected examples mentioned in Huddleston and Pullum (2002), Jaworska (1986) and Quirk et al. (1985), and checked their occurrences in the BNC. If the examples are attested in the BNC, we added them to the list. Four additional PCOPs were collected in this way: through till, until after, since before and from amongst.

Table 2, below, shows a list of PCOPs that we obtained using our two-step procedure, characterized by broad conceptual domain, viz. space, time, quantity or abstract.

A list of PCOPs categorized by conceptual domain.a

| Space | from behind, from under, at about, from around, from across, from beneath, at from, from about, across to, from outside, from beyond, from over, from throughout, from on, from off, to under, from underneath, from atop, from outside of |

| Time | from before, through till, until after, since before |

| Quantity | to about, to within, for about, for over, at between, to between, for between, at around, from between, with between, with about, to over, with over, to around |

| Abstract | from within, from among, from amongst |

-

aSome PCOPs can have different meanings. For example, to under is characterized as spatial in meaning in Table 2, but it also functions in the quantity domain, as in By 1985 this figure had reduced to under 4 %. In Table 2, the conceptual domains of PCOPs were determined based on their most frequent use.

The results show that the most frequent preposition that is followed by PCOPs is from, and that from is combined with various types of prepositions in PCOPs (Table 2). We therefore also investigated the prepositional phrases that follow from in the BNC. Table 3 summarizes the analysis, capturing prepositions following from, their hits in PCOPs, the total hits of the prepositions in the BNC and (in brackets) their rank among all prepositions in terms of their token frequency, and the two nouns most frequently appearing in these PCOPs.

The head prepositions of POCPs following from in the BNC.

| # | Preposition | Hits in PCOPs in the BNCa | Total hits in the BNC | Top 2 nouns appearing in the PCOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | behind | 610 | 19,073 (33)b | desk, door |

| 2 | within | 587 | 44,420 (21) | party, state |

| 3 | under | 472 | 54,804 (18) | feet, arm |

| 4 | around | 283 | 25,986 (26) | world, Atlantic |

| 5 | among | 233 | 22,439 (29) | member, number |

| 6 | across | 217 | 20,704 (30) | world, country |

| 7 | beneath | 180 | 4,403 (45) | lash, brow |

| 8 | between | 115 | 88,930 (14) | teeth, lips |

| 9 | about | 110 | 150,569(11) | cent, BC |

| 10 | out of | 95 | 46,796 (19) | town, nowhere |

| 11 | beyond | 77 | 10,137 (41) | grave, wall |

| 12 | amongst | 73 | 4,447 (45) | member, list |

| 13 | outside | 73 | 11,186 (39) | area, community |

| 14 | throughout | 67 | 11,451 (40) | Scotland, UK |

| 15 | off | 62 | 29,452 (24) | earth, Florida |

| 16 | over | 62 | 80,369 (15) | per cent, country |

| 17 | before | 53 | 45,272 (20) | war, birth |

| 18 | up | 42 | 22,542 (28) | lane, road |

| 19 | down | 38 | 17,465 (34) | road, valley |

| 20 | beside | 33 | 5,359 (44) | bed, knuckle |

-

aFalse positives were manually excluded from Table 3. bFigures in brackets in the “total hits in the BNC” column show the frequency ranking of each preposition in the BNC. For example, though behind and within are two top prepositions that appear in PCOPs, their frequency ranking among prepositions in the BNC are 33 and 21, respectively.

Table 3 shows (1) the relative prevalence of PCOPs headed by from in the BNC, (2) the dominance of two-syllable prepositions as heads of PCOPs, and (3) the diversity of noun types that appear within PCOPs. Building on these corpus findings, we now proceed to a general semantic description of PCOPs.

3.2 General semantic characteristics of PCOPs

Our corpus search results identify the following characteristics of PCOPs.

First, as hinted above, the phrases relate to four basic conceptual domains: space, time, quantity, and abstract. In the spatial sense, most PCOPs illustrate a region around the source or goal of a path as in (15).

| She was very nervous at first and would not come out from behind the piano. |

| Over 1,480 guests came from around the world to celebrate the 50th Anniversary … |

| Again there are echoes from across the Atlantic. |

| Patrick pulled his hands out from beneath the covers and … |

| I heard a sound from beyond the door … |

| Ocean floor then switched in Ordovician times from under the Midland Valley to under the Southern Uplands basement … |

In (15), PCOPs as a whole specify the region around their complement noun phrase, while from and to indicate that the region illustrated by PCOPs is either a source or a goal, respectively. Likewise, in the temporal sense, PCOPs illustrate a period either before or after the reference point illustrated by their complement noun phrase, as in (16).

| I’ve watched Liverpool from before the days of Bill Shankly |

| Certainly we shouldn’t re-issue anything until after the next meeting. |

In (16a) the PCOP as a whole illustrates the period in advance of the reference time (the days of Bill Shankly), while in (16b) it illustrates the period following the reference time (the next meeting).

In the quantity sense, the head preposition shows that the quantity described by the complement noun is approximate as in (17a), more than the reference value as in (17b), or within the reference value as in (17c).[11]

| … pregnancies are less viable than infants born with normal weight (i.e., with about 3,000–3,500 grammes) |

| That adds up to over 50 million a year |

| it had swelled to between 500,000 and one million people |

In the abstract sense, the complement of the preposition highlights an abstract thing that delimits a non-physical space where a trajector is found, such as an organization, as in (18), below.

| He was chosen from within the company. |

| So Leonard was called by name from among the congregation. |

This corpus-based analysis has already improved the descriptive accuracy of Huddleston and Pullum (2002): whereas they suggested that prepositional complements can only show spatial and temporal relations, we find two additional uses, which we have labelled “quantity” and “abstract”.

Second, the most typical preposition that takes prepositional complements is from, the preposition showing the source of a path. The frequency of from in this construction surpasses other prepositions for both the total hits and number of types and tokens of prepositions complementing it (see Tables 2 and 3).

The difference in frequency and distribution in PCOPs between from and its antonym, to, is striking. This may reflect the source-goal asymmetry, a universal linguistic tendency (Kopecka and Vuillermet 2021): languages tend to use more complex expressions for sources, and simpler and more ‘straightforward’ expressions for goals. In English, the object noun of motion verbs usually illustrates the goal of the motion while the source of motion needs to be explicitly marked by prepositions. So, the goal of the path is expressed without the preposition to as in sentences such as he moved {under/behind} the table, in which the prepositions under and behind show the goal of the path without to. In contrast, the source of the path of a movement requires explicit marking by from, e.g., He moved from {under/behind} the table. Here, PCOPs, showing the source of the path, are used.

Third, regarding the heads of PCOPs, Table 3 shows that the 14 most frequent prepositions following from are all two-syllable prepositions, with most of them etymologically morphologically complex – the exception being under. Frequent monosyllabic prepositions, such as at, in, and on, do not head PCOPs. In fact, the top 10 most frequent prepositions in the BNC are not found in the top 20 PCOPs complementing from.

Last, but not least, although there are some fixed phrases such as from around the world and from beyond the grave, most examples of PCOPs are highly productive. Table 3 includes the most frequent noun complements of PCOPs but hapax legomena are widely observed in our BNC data. A few examples of this are from behind a ruined byre, from within the TableCurve environment, from under her limp-brimmed woollen hat, and since before the previous Christmas.

In what follows, building on our corpus results, we discuss the fundamental question, hitherto neglected in scholarship on PCOPs: what, in the first place, licenses this on-the-face-of-it unexpected use of prepositions in Present-day English? In order to answer this question, we first zoom in further on the semantics of PCOPs in Section 4, arguing that there is in fact an important two-way distinction between uses, which seems to be independent of the space-time-quantity-abstract meaning differences. We are then in a position to discuss the conceptual basis of PCOPs in Section 5, where we identify an important similarity with (count) nouns, and argue that explains the existence of PCOP constructions.

4 Two types of PCOPs

This section investigates an important two-way distinction between uses of PCOPs, independent of the four-way distinction of conceptual domains identified, above. The two-way distinction may be difficult to observe when studying constructed examples, as those may not show the full breadth of authentic usage. Thus, it is perhaps not surprising that it has not been detected in previous studies, which have not been based on systematic corpus analysis. The distinction is based on the contribution made by the second preposition to the propositional meaning of the whole sentence.

| He was chosen from the company. |

| He was chosen from within the company. |

| A loud noise came from the room. |

| A loud noise came from behind the room. |

The sentences in (19) and (20) show that the preposition from can take both nominal complements, as in (19a) and (20a), and prepositional complements, as in (19b) and (20b). However, the prepositions that are the head of the PCOPs in (19b) and (20b), i.e., within and behind, differ in terms of their role in the propositional semantics of the sentences they occur in. The propositional meaning of the two sentences in (19) does not change when the preposition within is added or deleted: the region profiled by from within the company is the same as in from the company. In contrast, the two sentences in (20) differ in propositional meaning: from behind the room illustrates the particular area that is on the other side of the room, relative to the speaker’s vantage point, while from the room illustrates an unspecified area inside the room. We will call the former type the Emphasis Type and the latter the Search-domain Type. Let us now discuss the use of two types of PCOPs in some more detail.

4.1 Emphasis Type

We label the first type of PCOPs the Emphasis Type, as it highlights the region that is illustrated by their complement noun. With reference to the four meaning types of PCOPs identified in Section 3.2, above, the Emphasis Type can be used in the spatial sense as in (21), the temporal sense as in (22), and the abstract sense as in (23).

| We collected samples from (throughout) the UK . |

| Over 1,480 guests came from (around) the world to celebrate the 50th Anniversary |

| we reprint our favorite fan mail from (throughout) the week . |

| The project team was chosen from (within) the company . |

| … he asked for volunteers from (among/amongst) the considerable number of apprentices in London . |

In the Emphasis Type, the regions illustrated by PCOPs as a whole (italicized) and their complement noun phrases (underlined) correspond. For example, in (21a), the PCOP (throughout the UK) as a whole and its complement noun phrase (the UK) profile exactly the same region, and the sentences express the same proposition with or without the preposition that heads the PCOP. The same applies to (22)–(23).

Although the head preposition in PCOPs does not change the propositional meaning in this type, it nevertheless makes a contribution to the meaning of the sentence: it serves the communicative (or pragmatic) purpose of emphasizing the regions illustrated by the following complement nouns. For example, in (21a), the sentence does not simply describe the situation where the samples were collected in potentially only a few areas in the UK, but it emphasizes that they were collected from all over the UK. In (21b) the preposition around suggests that guests came from many parts of the bounded region that is the world. Similarly, in (22), the speaker wants to highlight the idea of choosing a particular subset of the fan mail from all the mail received in the entire week, as opposed to perhaps just one or a couple of days. In (23a), the head preposition within emphasizes the boundary that divides the inside and outside of the organization, highlighting that the members were from that particular company as opposed to being external. Likewise, in (23b), the head preposition amongst subtly emphasizes that volunteers were sought from within that group of apprentices rather than from outside that group. Based on the examples in (21)–(23), we could further argue that within the Emphasis Type there are two sub-types: one with emphasis on the boundaries as in (23); the other with emphasis on the full extent/scope of the region as in (21)–(22).

4.2 Search-domain Type

We call the second functional type of PCOPs the Search-domain Type. This type is different from the Emphasis Type in that omission of the head preposition of PCOPs changes the propositional meaning of the sentence. In this type, the region illustrated by the second preposition functions as a search domain within which the target (a prominent entity referred to in the clause) can be found.

The Search-domain Type may be most widely used in its spatial sense, where PCOPs show a source of a path. In (24), the prepositions following from illustrate various spatial regions with respect to their complement nouns.

| Something had crawled from under a stone. |

| Just then the moon came out from behind a cloud. |

| it is useful to refer to theories from outside of sociology |

| He sneaked a glance at her from beneath his brows |

| And it may be that Justin, too, has more to say, from beyond the grave |

| This time it’s the lady from down the road |

The prepositions following from in (24), i.e., the heads of the PCOPs, illustrate the regions or search domains within which the target (underlined) is to be found. The examples also show that the target may but need not be the subject of the clause; for instance, in (24c) the target is theories, which is the object of refer (to).

Turning to why these expressions exist and are used, we note that whilst it would be possible to verbalize the conceptual content of these sentences in ways that avoid PCOPs, those alternatives would typically be longer. For example, compare (24a) to Something had crawled from its space under the stone.

Certain frequent, monosyllabic prepositions such as at, in and on do not usually appear in PCOPs. The reason for this, we suggest, is that when they describe a source of a path, the locations that one might expect to be designated by these prepositions can in fact be inferred without them.

| He wiped off some water from the table. |

| He appeared from the house. |

| She came from the harbour. |

In the examples in (25), the preposition from takes nominal complements, although, semantically, the (underlined) trajectors are interpreted as being “on the table” in (25a), “in the house” in (25b) and “at the harbour” in (25c). The question arises as to why additional prepositions are not required. We suggest that these landmarks all have predictable and salient regions relative to which the events in question can be situated: tables are normally used by placing items on top of them, so the surface area is the most predictable “active zone”, to use Langacker’s term (1987: 271–274). Houses are mostly construed as being made to live inside of. Harbours are centered around sheltered areas of water but may also include other infrastructure such as terminals, warehouses and dry docks, and are therefore typically construed without any clear boundaries. For that reason, we often think of events as happening at them, rather than in them. Thus, since the examples in (25) all involve the most predictable active zones, the prepositions on, in or at are redundant.

In contrast, the regions illustrated by the mostly disyllabic prepositions as in (24) are less predictable from the landmarks. They can therefore not be easily inferred without them. A stone (see example 24a), for example, does not have a single most obvious and predictable function in our everyday experience. Likewise, we do not interact with clouds (24b) in any particularly prototypical or predictable fashion. We suggest that this is the reason why we need PCOPs with specific prepositions when these regions are a source of a path.[12]

Our suggestion concerning ‘predictable regions’ is grounded in Heidegger’s phenomenology. Specifically, Heidegger (1962) argued that we primarily see objects in the world not in isolation, in terms of their physical properties, but rather from the point of view of what we can do with them; their “Zuhandenheit” or ‘readiness-to-hand’ (ibid.: 98). So, a table (as in (25a)), for instance, is a something-I-can-put-something-or-work-on. By contrast, a stone (as in (24a) is less obviously construed as a something-that-something-can-hide-under. Consider that it could just as easily be a something-that-I-can-use-for-hammering, a something-that-I-can-use-as-a-projectile or a something-that-I-can-use-for-building-or-landscaping. Thus, we argue that an entity’s readiness-to-hand helps us understand why on some occasions PCOPs are needed, when in other situations the source requires only a prepositional phrase with a regular nominal complement.

PCOPs can also illustrate the goal of a path, although examples, such as (26), are less frequent:

| then his hand moved to under her chin |

In (26), the preposition following to also identifies with greater precision the region within which the target (his hand) can be found. However, compared to from, the use of to in PCOPs is more restricted in use and some speakers feel that the preposition to in (26) is redundant and makes the sentence sound awkward. The difference in acceptability between (26) and then his hand moved from under her chin, which is not awkward in any way, may reflect the general characteristic of English that prepositional phrases that in isolation describe a location (such as under her chin) are interpreted as goals when they co-occur with movement verbs, including move, go and come.[13] This renders to in (26) unnecessary, and, to some speakers, dispreferred.

The Search-domain function is also widely observed in the quantity sense, as in (27).

| it had swelled to between 500,000 and one million people |

| … pregnancies are less viable than infants born with normal weight (i.e., with about 3,000–3,500 grammes) |

| That adds up to over 50 million a year |

This use is generally classified as adverbial in dictionaries and grammars. However, it seems reasonable to assume that the quantity sense is metaphorically derived from the spatial sense, which is more concrete. The quantity sense of PCOPs profiles the abstract region around the landmark, which in this case is a reference value rather than a physical location. Considering the semantic link between the spatial use and the quantity use, our view is that ignoring the latter based on a suggestion that the forms here function as adverbs not prepositions would impoverish our account of PCOPs.

The Search-domain Type is also observed in the temporal sense, as in (28).

| … as it contains a species of trout which, like the omul in Lake Baikal, has survived from before the last Ice Age … |

| Yet heavy taxes in kind continued until after the end of 1922. |

In (28a), the PCOP allows one to refer to the period before the last Ice Age without needing to resort to a longer verbalization such as from the period before the last Ice Age. The PCOP headed by before illustrates the era before the landmark (the last Ice Age). Likewise, in (28b), the PCOP offers a convenient way to refer to the period after the end of 1922, although PCOP-less alternatives are available, such as Yet heavy taxes in kind continued until the end of 1922 and beyond.

4.3 Motivations for using the two types of PCOPs

The discussion in Section 4.1 and 4.2, above, has demonstrated that the use of the two types of PCOPs is functionally motivated.

In the Emphasis Type the preposition that heads the PCOP is not necessary from the point of view of the propositional semantics of the sentence. However, adding it to create an instance of this syntactically irregular pattern enables the speaker to emphasize the full extent and/or boundaries of the concept designated by the object of the preposition.

For the Search-domain Type, inspired by Heidegger’s notion of “Zuhandenheit” or ‘readiness-to-hand’ (1962: 98), we suggested that the real-world function of objects (e.g., stones) that complement the prepositions in PCOPs are not sufficiently predictable for the preposition that heads the PCOP to be omitted. This is in contrast to sentences with landmarks which we interact with in more predictable ways (e.g., tables). If the event described by such sentences involves an interaction with a predictable active zone, then there is no need to add an additional preposition to form a PCOP (see the examples in (25)). Furthermore, we observed that PCOPs may offer economical ways to express the relevant spatial region in which the trajector is to be located, compared to wordier alternatives: compare Something had crawled from under a stone (= (24a)) to Something had crawled from its space under the stone.

The characteristics of the two types are summarized as in Table 4:

Summary of two functions of PCOPs.a

| Motivation | Impact of removing preposition on propositional meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Emphasis Type | Pragmatic motivation | No change in meaning |

| Search-domain Type | Semantic motivation and/or economy of effort | Change in meaning |

-

aNote that there is no one-to-one relation between each preposition and the two functional types of PCOPs. Prepositions such as across have both functions as in (1) below.

(1) a. Over 300 amateur golfers from across the United Kingdom. [Emphasis Type] b. She called out to me from across the room. [Search-domain Type]

The focus of this paper is on PCOPs rather than other syntactically irregular uses of prepositions. However, we will note here briefly that prepositional subjects, seem to only have the Search-domain function – or some version of it. The examples in (7) and (10), repeated below as (29), are similar to Search-domain PCOPs in that omitting the preposition changes the propositional meaning.

| Across the road was swarming with bees. |

| By air seems to be quite cheap. |

| Under the chair attracted the cat’s attention. |

| Over a year was spent on this problem. |

| Before the end of the week would suit me better. |

The prepositional phrases identify a region but instead of pointing to where some phrase-external target is to be found, there is no target outside the prepositional phrase, it being the most salient referent of the clause.

Another difference between PCOPs and prepositional subjects is that the latter do not seem to be limited to the four functions of Space, Time, Quantity and Abstract identified for PCOPs (see Section 3.1, above). For instance, example (29b), above, shows that the prepositional subject can designate means.

Since PCOPs and prepositional subjects have different functions, we suggest that these constructions are not merely positional variants of a single nominal prepositional phrase construction, or of prepositional phrases more broadly. The two functions are characteristics of PCOPs rather than general characteristics of (nominal) prepositional phrases. From a usage-based perspective, this implies that PCOPs may have a degree of psychological independence from nominal prepositional phrases or prepositional phrases more generally. This aligns with Croft’s suggestion that word classes are ultimately construction-specific (2001, 2022), yielding a rather larger set of categories than what is typically suggested in reference grammars of English.

5 Conceptual basis of PCOPs

In this section we explain the conceptual motivation for the use of PCOPs – whose existence, once again, is syntactically irregular as prepositions are normally complemented by noun phrases. We do this by offering a conceptual characterization of PCOPs based on image schemas[14] (Section 5.1). We visually illustrate the image schemas of the two types of PCOPs separately and then show the similarity shared by the two types. That shared conceptual characterization launches us into a discussion of the similarity between PCOPs and noun phrases. And it is this similarity, we argue (Section 5.2), that licenses the occurrence of these prepositional phrases as complements of prepositions.

5.1 Conceptual characterization of PCOPs

Despite the distinction between the two types of PCOPs, the Emphasis Type and the Search-domain Type (see Sections 4.1 and 4.2, respectively) they share an important conceptual similarity: they emphasize a specific region. Here, we start with the conceptual characterization of the Emphasis Type.

Consider the examples in (30), where the preposition from takes a nominal complement in (30a) and a PCOP in (30b).

| He was chosen from the company. |

| He was chosen from within the company. |

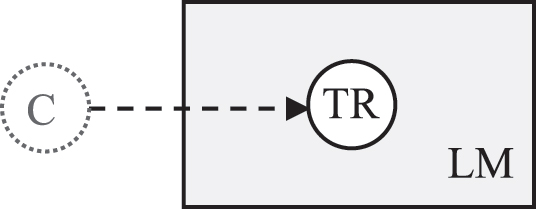

In line with what we have observed above, examples (30a) and (30b) are propositionally identical yet there is a nuanced difference in conceptualization. The preposition within in (30b) emphasizes the boundary, or the notion that the trajector (he) was chosen from within a particular organization as opposed to externally. Therefore, the situations illustrated by (30a) and (30b) can be illustrated as in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. Both figures show that the trajector (he), which was located in the landmark (the company), was picked up from inside of the landmark by the backgrounded chooser (abbreviated as C). The difference is that the boundary in Figure 2 is in bold, to represent the salience of the boundary of the landmark arising from the additional preposition in (30b).

The TR is chosen from the LM.

The TR is chosen from within the LM.

Similar visual representations could be drawn for the other examples of the Emphasis Type presented in Section 4.1.

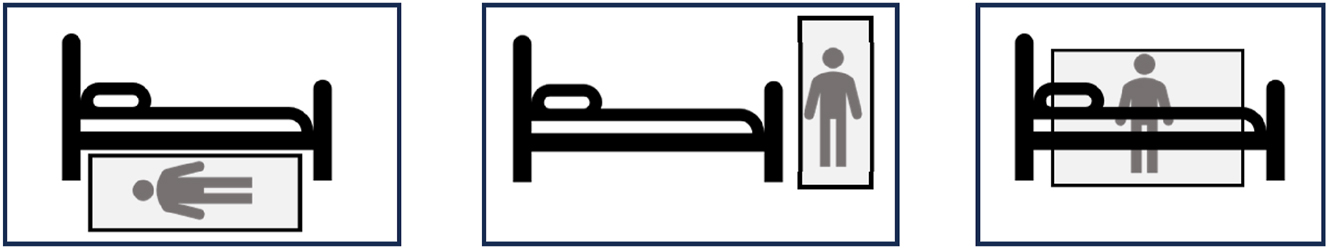

Moving on to the Search-domain type, consider the examples in (31):

| He appeared from under the bed. |

| He appeared from beside the bed. |

| He appeared from behind the bed. |

In these examples, the prepositional heads of the PCOPs, under, beside and behind point to the relevant regions with respect to the landmark (the bed), i.e., the specific regions where the trajector (he) is to be found. The situations described by (31) are illustrated in Figure 3, below.

Image schemas of the sentences he appeared from {under/beside/behind} the bed.

Although the image schemas in Figures 2 and 3 might not appear similar at first sight, a close look reveals a key common characteristic: in both cases, PCOPs designate a bounded region within which the trajector is to be found. The Emphasis Type highlights the boundary and/or extent of the landmark itself, with the Search-domain Type illustrating the relevant region relative to the landmark, but – crucially – both types profile a bounded region.

This conceptual characterization of PCOPs is supported by evidence from acceptability judgments of sentences with prepositions that highlight boundedness to a greater or lesser degree. Examples (32)–(33) show that PCOPs become more acceptable if we replace relatively abstract (monosyllabic) prepositions with (multisyllabic or complex) prepositions with meanings that increase the salience of the boundaries of their nominal complements:

| He appeared from {inside/*in} the house. |

| He was chosen from {within/*in} the group. |

| We collected samples from {throughout/*through} the UK. |

| He pulled up the wooden chair from {beside/?by} the bed … |

| He appeared from {?on top of/??on} the hill. |

| He came from {?in front of/*in} the garden. |

The different acceptability and grammaticality of the pairs of truth-conditionally equivalent prepositions in the examples above suggests that the acceptability of PCOPs increases when the boundary illustrated by PCOPs is more highlighted.

We further note that PCOPs only illustrate a location (i.e., a static region), while many prepositional phrases that can function as PCOPs may illustrate paths when used in other contexts. The examples in (34) demonstrate that even prepositional phrases headed by over and beyond always show a location when they appear in PCOPs.

| He came from over the bridge. |

| This showed that the radiation must come from beyond the Solar System |

| Follow the trail that leads over the bridge, then continue into the meadow on the other side. |

| Scientists hope that future spacecraft will journey beyond the Solar System, reaching out toward distant stars. |

(34a) means ‘he came from the other side of the bridge.’ Here, the region illustrated by the PCOP is bounded by one of its sides, namely, the edge of the bridge. In (34b), the PCOP, beyond the Solar System, illustrates the area outside of the Solar System. Here, the beyond phrase shows a static region. The examples in (34) demonstrate that even the prepositional phrases headed by over and beyond always show a location when they appear in PCOPs. Compare these examples to (35), where the over and beyond phrases do not complement another preposition, and describe a path rather than a static region.

We conclude this section by illustrating how PCOPs are integrated into larger prepositional phrases through grammatical valence relationships, where they function as complements. Figure 4 presents the compositional path leading to a higher-level prepositional phrase containing a PCOP of the Emphasis Type, while Figure 5 illustrates the path for the Search-domain Type.

Compositional path to the higher structure in Emphasis Type.

Compositional path to the higher structure in Search-domain Type.

Figures 4 and 5 clearly demonstrate conceptual similarity between the two PCOP types: (1) the superordinate prepositional phrases containing PCOPs are combined from two prepositional phrases; (2) within the larger structure, the PCOP specifies the region where the trajector is found; and (3) this region is specified relative to a landmark. In the Emphasis Type, the region overlaps with and emphasizes the landmark itself. In the Search-domain Type, it specifies a particular area in relation to the landmark.

5.2 PCOPs from a cognitive and functional perspective

We can now address the fundamental question as to why PCOPs appear in the position usually reserved for noun phrases. In response to this question, we point to our conceptual characterization of PCOPs, which suggests that they are similar in this regard to nouns or noun phrases, as analyzed in Cognitive Grammar:

| A noun, for example, is a symbolic structure whose semantic pole instantiates the schema [THING]; or to phrase it more simply, a noun designates a thing. … I propose that a thing is properly characterized as a region in some domain, i.e., every nominal predication designates a region. Count nouns represent a special but prototypical case, in which the designated region is specifically construed as being bounded in a primary domain. (Langacker 1987: 189) |

Thus, the Cognitive Grammar definition of (count) nouns corresponds to the conceptual characterization of PCOPs that we proposed in the previous section: highlighting a bounded region. Given that prototypical complements of prepositions are nouns, it is plausible that the acceptability of PCOPs increases as their conceptual characteristics become more similar to those of noun phrases.

Although PCOPs are often regarded as syntactically irregular in reference grammars of English, they are neither atypical nor anomalous from a cognitive semantic perspective. On the contrary, their existence is expected within the framework of Cognitive Grammar. As illustrated in the image-schematic diagrams, the bounded regions designated by PCOPs are construed as things in Cognitive Grammar terms, given that a thing is defined as a region in some domain.[15]

The examples below show that nominal phrases and PCOPs occupy the same syntactic slot, both indicating spatial regions.

| He came from the bridge. (from + NP) |

| He came from the bottom of the bridge. (from + NP) |

| He came from the top of the bridge. (from + NP) |

| He came from across the bridge. (from + PP) |

| He came from under the bridge. (from + PP) |

| He came from behind the bridge. (from + PP) |

In (37)–(39), various bounded spatial locations related to the bridge are expressed: Its entirety is expressed by noun phrase in (37), its internal parts by the noun phrases in (38), and the locations around it by the prepositional phrases in (39).

We can now turn briefly to prepositional subjects. We have not done a corpus search for examples, as they are not the focus of this paper. However, we suggested above that their function is very similar to the Search-domain type, as defined for PCOPs. Given, therefore, that they highlight a bounded region as well, we suggest that therein lies the reason as to why they are licensed: just like PCOPs they are conceptually very similar to nouns and noun phrases.

A distributionalist definition of word classes, or one organized in terms of abstract features (compare the discussion in Section 2.1), does not straightforwardly provide any explanation as to why prepositional phrases can appear in this slot, normally occupied by noun phrases. In contrast, a conceptual characterization of word classes does explain why these two classes may display similarities in their syntactic behavior. Overall, the acceptability of PCOPs underlines not only the feasibility but in fact the necessity of a (at least partially) conceptual characterization of word classes.

6 Conclusions

In this paper we have carried out corpus-based research of PCOPs, combined with careful qualitative analysis of authentic usage patterns. This has yielded an overview of the relatively widespread use of PCOPs in Present-day English, including the types of prepositions appearing in PCOPs and the identification of the strong tendency for prepositions appearing in the head of PCOPs to be disyllabic rather than monosyllabic. Improving on previous accounts, we observed that PCOPs may relate to four conceptual domains: space, time, quantity and abstract. We then discussed the functions of PCOPs, classifying them into two types: the Emphasis Type and the Search-domain Type. We have shown how the use of each of these is functionally motivated. In the Emphasis Type, the addition of a preposition – whilst not necessary from a truth-conditional semantics perspective – allows speakers to highlight the full extent or boundaries of a relevant region. In the Search-domain Type, by contrast, we argued that Heidegger’s notion of “Zuhandenheit” or ‘readiness-to-hand’ (1962: 98) may help us understand the construal of entities described by the complements of prepositions in the PCOPs. Specifically, less predictable real-world functions of these entities may necessitate the addition of the second preposition. Additionally, PCOPs can provide a more economical way to express spatial relations compared to alternative phrasing. We noted in passing that prepositional subjects – not the focus of our paper – may relate to another conceptual domain, i.e., means, and that their function can be characterized in Search-domain terms as well.

Subsequently, we analyzed the common conceptual basis of the two types of PCOPs in terms of Cognitive Grammar. Although they are functionally distinct to a degree, they share the function of designating a bounded region. Importantly, from the point of view of the question around the syntactically irregular distribution of PCOPs, their conceptual characterization corresponds to that of noun phrases. We argue that this similarity licenses PCOPs. We also propose that prepositional subjects can be accounted for in the same manner.

In terms of a theoretical contribution, this paper has underlined not only the feasibility but the necessity of a conceptual characterization of word classes. Moreover, we have demonstrated the importance of studying grammar from the point of view of semantics, pragmatics and to a limited degree also phonology: we have drawn on all these levels in our account of PCOPs. On a descriptive level our detailed analysis of PCOPs represents a notable contribution as well, as this phenomenon had thus far been almost completely ignored in reference grammars of English and other scholarship.

Funding source: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

Award Identifier / Grant number: Grant-in-Aid for Fund for the Promotion of Joint I

-

Research funding: This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Fund for the Promotion of Joint I from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

-

Data availability: The data are available at https://osf.io/x9m8c/.

References

Altenberg, Evelyn P. & Robert M. Vago. 2010. English grammar: Understanding the basics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511794803Suche in Google Scholar

Aston, Guy & Lou Burnard. 1998. The BNC handbook: Exploring the British national corpus with SARA. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad & Edward Finegan. 1999. Longman grammar of spoken and written English. London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Carter, Ronald & Michael McCarthy. 2006. Cambridge grammar of English: A comprehensive guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1970. Remarks on nominalization. In Roderick A. Jacobs & Peter S. Rosenbaum (eds.), Readings in English transformational grammar, 184–221. Waltham, MA: Ginn.Suche in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 2001. Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198299554.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 2022. Morphosyntax: Constructions of the world’s languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316145289Suche in Google Scholar

Croft, William. 2023. Word classes in radical construction grammar. In Eva van Lier (ed.), The Oxford handbook of word classes, 213–230. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198852889.013.48Suche in Google Scholar

Fillmore, Charles J., Paul Kay & Mary C. O’Connor. 1988. Regularity and idiomaticity in grammatical constructions: The case of let alone. Language 64. 501–538. https://doi.org/10.2307/414531.Suche in Google Scholar

Hawkins, Bruce W. 1984. The semantics of English spatial prepositions. PhD Dissertation. San Diego: University of California.Suche in Google Scholar

Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and time. Transl. by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.Suche in Google Scholar

Hollmann, Willem B. 2012. Word classes: Towards a more comprehensive usage-based account. Studies in Language 36(3). 671–698. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.36.3.08hol.Suche in Google Scholar

Hollmann, Willem B. 2013. Nouns and verbs in Cognitive Grammar: Where is the ‘sound’ evidence? Cognitive Linguistics 24. 275–308. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2013-0009.Suche in Google Scholar

Hollmann, Willem B. 2021. The ‘nouniness’ of attributive adjectives and ‘verbiness’ of predicative adjectives: Evidence from phonology. English Language & Linguistics 25(2). 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1360674320000015.Suche in Google Scholar

Hopper, Paul J. & Sandra A. Thompson. 1984. The discourse basis for lexical categories in universal grammar. Language 60(4). 703–752.10.1353/lan.1984.0020Suche in Google Scholar

Huddleston, Rodney & Geoffrey K. Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781316423530Suche in Google Scholar

Jaworska, Ewa. 1986. Prepositional phrases as subjects and objects. Journal of Linguistics 22(2). 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022226700010835.Suche in Google Scholar

Johnson, Mark. 1987. The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226177847.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Kopecka, Anetta & Marine Vuillermet. 2021. Source-goal (a)symmetries across languages. Studies in Language 45(1). 2–35. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.00018.kop.Suche in Google Scholar

Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.10.7208/chicago/9780226471013.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundation of cognitive grammar, vol. 1. Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 1991. Foundations of cognitive grammar, vol. 2. Descriptive application. Stanford: Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 1993. Reference-point constructions. Cognitive Linguistics 4(1). 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1993.4.1.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 2008. Cognitive grammar: A basic introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195331967.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Langacker, Ronald W. 2009. Reflections on the functional characterization of spatial prepositions. Belgrade English Language and Literature Studies 1(1). 9–34. https://doi.org/10.18485/bells.2009.1.1.Suche in Google Scholar

Otani, Naoki. 2015. Zenchishiku no Hogo Toshite Mochiirareru Zenchishiku no Meishiteki Youhou ni Tsuite [Prepositional phrases as complements of prepositions]. JELS 32. 98–104.Suche in Google Scholar

Otani, Naoki. 2019. From ni Kouzokusuru Zenchishiku no Hogoku Youhou ni Tsuite [A corpus-based analysis of prepositional complements of the preposition from]. JELS 36. 134–140.Suche in Google Scholar

Otani, Naoki. 2023. A cognitive sociolinguistic study of prepositional complements of prepositions in English, Paper presented at the 16th International Cognitive Linguistics Conference (ICLC16), Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, 7–11 August.Suche in Google Scholar

Otani, Naoki & WillemB. Hollmann. 2025. Prepositional phrase complements of prepositions: A cognitive grammar explanation. In paper presented at the 17th International Cognitive Linguistics Conference (ICLC17), Buenos Aires, 14–18 July.Suche in Google Scholar

Palmer, Frank. 1971. Grammar. Harmondsworth: Penguin.Suche in Google Scholar

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech & Jan Svartvik. 1985. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman.Suche in Google Scholar

Swan, Michael. 2005. Practical English usage, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Talmy, Leonard. 1985. Lexicalization patterns: Semantic structure in lexical forms. In Timothy Shopen (ed.), Language typology and syntactic description, 3, 57–149. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Talmy, Leonard. 2000. Toward a cognitive semantics, vol. 1. Concept structuring systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/6847.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Wierzbicka, Anna. 1985. Oats and wheat: The fallacy of arbitrariness. In John Haiman (ed.), Iconicity in syntax, 311–342. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins.10.1075/tsl.6.16wieSuche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.