Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which typically – although not exclusively – entails development of thrombosis into one or more veins of the (lower) limb(s) and possible embolization in one or both pulmonary arteries, is an important and growing public health concern. The global annual incidence of VTE is approximately 100 per 100,000 person-years among Whites, is slightly higher among Blacks and lower among Asian- and Native-Americans. The incidence of this pathology is also strongly influenced by ageing, increasing by approximately 90-fold from the time of childhood to the elderly. Although some studies described that male gender may be a predisposing factor, definitive data on this aspect are lacking [1].

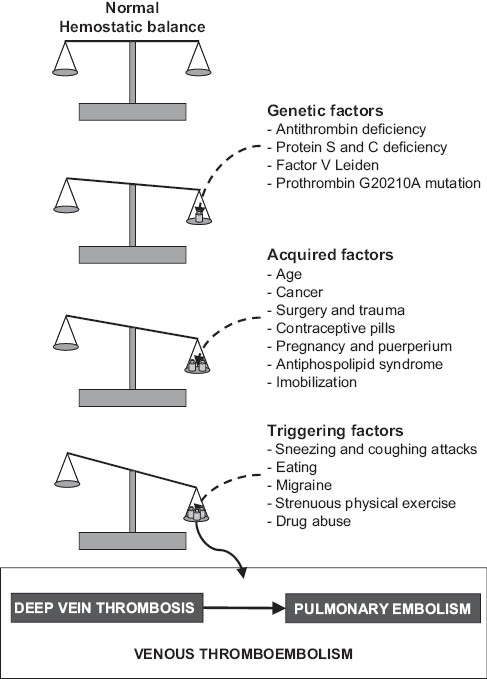

In analogy with another frequent thrombotic disorder, cardiovascular disease [2], the pathogenesis of VTE is complex and substantially multifactorial. In brief, VTE is conventionally thought to develop in a patient with a genetic predisposition [3], in whom an acquired [4] or triggering factor [5] contributes to worsen the baseline impairment of the hemostatic balance towards a highly prothrombotic state [6], which ultimately culminates with onset of venous thrombi followed by potential propagation upward, throughout the venous system (Figure 1).

Pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism.

Due to relative high frequency, substantial genetic background and potentially preventable nature [3], this disease appears well suited for screening strategies that typically entail thrombophilia testing. Indeed, the coagulation laboratory has an enormous potential for investigation of patients with VTE [7], but all these weapons must be used with moderation and intelligence. In the general perspective of values-based reimbursement and accountability of laboratory performance, there is general consensus that a diagnostic test is only useful when it has an influence on clinical management, when it improves the outcome or, preferably, reverses an adverse outcome. Laboratory testing does not come for free. Irrespective of different reimbursement policies across various countries, laboratory testing still places a considerable economic burden on patients and healthcare system as a whole [8], and should hence be based on evidence of clinical efficacy (i.e., improving outcomes) rather than efficiency (i.e., diagnosing diseases). In this issue of the journal, we publish a double-edged sword debate about utility and futility of thrombophilia testing [9, 10]. In this editorial, I will not anticipate the contents of the pro and the counter, but I wish to express some general considerations about the potential benefits and the tangible risks of thrombophilia screening.

A necessary premise, shared with other areas of diagnostic testing, is that indiscriminate screening must be avoided, since this strategy carries a latent risk of identifying a large number of “prothrombotic subjects” by nature of a positive test result, who will never become “patients” (i.e., develop thrombosis throughout their lifetime) due to the low penetrance of most prothrombotic abnormalities. Using Factor V Leiden as an example, only 10% of heterozygous carriers of this polymorphism will develop VTE throughout their lifetime, with varying degrees of severity [11]. So, indiscriminate screening is clearly unacceptable, for a number of clinical (e.g., potential for inappropriate clinical management) and ethical (e.g., psychological distress) reasons. However, there are several elements that support focused testing in selected categories of individuals. It is an analysis of these aspects that are raised by Massimo Franchini, who takes the case in favor of testing [9], and Emmanuel Favaloro, who instead highlights areas of uncertainty and raises reasonable drawbacks against testing [10].

What should be clear to everybody is that thrombophilia testing is only effective in those patients who will benefit from targeted thromboprophylaxis or differential management (e.g., prolonged treatment) under specific clinical or environmental circumstances. Most of these conditions are clearly discussed by Franchini [9], as well as in a recent review of guidelines from Scientific Societies and Working Groups, authored by De Stefano and Rossi [12]. It is also noteworthy, however, that focused (or targeted) screening is nothing but foolproof, and there are additional actual risks of obtaining false-negative and false-positive results, as highlighted by Favaloro [10]. Beside obvious economic considerations in a world with limited resources, the consequences may be deleterious in either circumstance. A false-negative result may encourage the misleading reassurance of a low thromboembolic risk, prevent the use of physical or chemical prophylaxis when otherwise needed, thus exposing the patient to an unethical risk of thrombosis. A false-positive result, which can be due to technical (i.e., “normal” outliers of reference ranges) [13] or clinical (i.e., laboratory testing in patients on anticoagulant therapy) [14] reasons, would instead jeopardize the clinical decision making, with the risk of establishing inappropriate prophylaxis or promoting unjustified lifestyle changes (e.g., avoidance of oral contraceptives in “false-positive” carriers of prothrombotic polymorphisms).

All this said and although it seems maybe pessimistic to conclude that thrombophilia testing generates outcomes that are even worse than not having investigated at all, the take-home message from this fervent debate is that we have not reached an univocal truth so far and – even in this field of diagnostic testing – specific counseling and “personalized” approaches are probably the most clinically efficacious and cost-effective solutions, wherein the various tests should be cautiously requested according to familiar and clinical history, the presence of inherited or acquired risk factors, the type, site and extension of thrombosis, and always weighted against the tangible threat of side effects of anticoagulant therapy.

Conflict of interest statement

Author’s conflict of interest disclosure: The author stated that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

References

1. Montagnana M, Favaloro EJ, Franchini M, Guidi GC, Lippi G. The role of ethnicity, age and gender in venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2010;29:489–96.10.1007/s11239-009-0365-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Lippi G, Franchini M, Targher G. Arterial thrombus formation in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2011;8:502–12.10.1038/nrcardio.2011.91Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Lippi G, Franchini M. Pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism: when the cup runneth over. Semin Thromb Hemost 2008;34:747–61.10.1055/s-0029-1145257Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Favaloro EJ, Franchini M, Lippi G. Coagulopathies and thrombosis: usual and unusual causes and associations. Part V. Semin Thromb Hemost 2011;37:859–62.10.1055/s-0031-1297363Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Lippi G, Franchini M, Favaloro EJ. Unsuspected triggers of venous thromboembolism–trivial or not so trivial? Semin Thromb Hemost 2009;35:597–604.10.1055/s-0029-1242713Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Baskurt OK, Meiselman HJ. Iatrogenic hyperviscosity and thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012;38:854–64.10.1055/s-0032-1325616Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. Laboratory hemostasis: milestones in Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:91–7.10.1515/cclm-2012-0387Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C. Testing volume is not synonymous of cost, value and efficacy in laboratory diagnostics. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:243–5.10.1515/cclm-2012-0502Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Franchini M. The utility of thrombophilia testing. Clin Chem Lab Med. Med 2014;52:495–7.10.1515/cclm-2013-0559Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Favaloro EJ. The futility of thrombophilia testing. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014;52:499–503.10.1515/cclm-2013-0560Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

11. De Stefano V, Rossi E. Testing for inherited thrombophilia and consequences for antithrombotic prophylaxis in patients with venous thromboembolism and their relatives. A review of the Guidelines from Scientific Societies and Working Groups. Thromb Haemost 2013;110:697–705.10.1160/TH13-01-0011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Cohen W, Castelli C, Alessi MC, Aillaud MF, Bouvet S, Saut N, et al. ABO blood group and von Willebrand factor levels partially explained the incomplete penetrance of congenital thrombophilia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32:2021–8.10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248161Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Plebani M, Lippi G. Reference values and the journal: why the past is now present. Clin Chem Lab Med 2012;50:761–3.10.1515/cclm-2012-0089Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Tripodi A. Problems and solutions for testing hemostasis assays while patients are on anticoagulants. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012;38:586–92.10.1055/s-0032-1319769Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Plebani M, Lippi G. Personalized (laboratory) medicine: a bridge to the future. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:703–6.10.1515/cclm-2013-0021Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

©2014 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Editorials

- Inflammatory bowel diseases: where we are and where we should go

- Thrombophilia testing. Useful or hype?

- Reviews

- Inflammatory bowel diseases: from pathogenesis to laboratory testing

- Crohn’s disease specific pancreatic antibodies: clinical and pathophysiological challenges

- Point/Counterpoint

- The utility of thrombophilia testing

- The futility of thrombophilia testing

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Identification of an 18 bp deletion in the TWIST1 gene by CO-amplification at lower denaturation temperature-PCR (COLD-PCR) for non-invasive prenatal diagnosis of craniosynostosis: first case report

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Agreement of seven 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 immunoassays and three high performance liquid chromatography methods with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- First trimester pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and human chorionic gonadotropin-beta in early and late pre-eclampsia

- S100B blood level measurement to exclude cerebral lesions after minor head injury: the multicenter STIC-S100 French study

- NGAL, L-FABP, and KIM-1 in comparison to established markers of renal dysfunction

- Value-added reporting of antinuclear antibody testing by automated indirect immunofluorescence analysis

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- A fit-for-purpose approach to analytical sensitivity applied to a cardiac troponin assay: time to escape the ‘highly-sensitive’ trap

- Diabetes

- A simple and precise method for direct measurement of fractional esterification rate of high density lipoprotein cholesterol by high performance liquid chromatography

- Infectious Diseases

- Detection of unamplified HCV RNA in serum using a novel two metallic nanoparticle platform

- Increased plasma arginase activity in human sepsis: association with increased circulating neutrophils

- Corrigendum

- The relationship between estimated average glucose and fasting plasma glucose

- Letter to the Editors

- The obsessive-compulsory clinical pathologist

- Prism effect of specimen receiving – generation of fundamentals for the smooth progress of analytical processing

- Preanalytical errors: the professionals’ perspective

- Corrected reports in laboratory medicine in a Chinese university hospital for 3 years

- Comparison of an enzymatic assay with liquid chromatography-pulsed amperometric detection for the determination of lactulose and mannitol in urine of healthy subjects and patients with active celiac disease

- Effect of freezing-thawing process on neuron specific enolase concentration in severe traumatic brain injury sera samples

- Undetected creatinine levels

- The effect of centrifugation on three urine protein assays: benzethonium chloride, benzalkonium chloride and pyrogallol red

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Editorials

- Inflammatory bowel diseases: where we are and where we should go

- Thrombophilia testing. Useful or hype?

- Reviews

- Inflammatory bowel diseases: from pathogenesis to laboratory testing

- Crohn’s disease specific pancreatic antibodies: clinical and pathophysiological challenges

- Point/Counterpoint

- The utility of thrombophilia testing

- The futility of thrombophilia testing

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Identification of an 18 bp deletion in the TWIST1 gene by CO-amplification at lower denaturation temperature-PCR (COLD-PCR) for non-invasive prenatal diagnosis of craniosynostosis: first case report

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Agreement of seven 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 immunoassays and three high performance liquid chromatography methods with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- First trimester pregnancy-associated plasma protein A and human chorionic gonadotropin-beta in early and late pre-eclampsia

- S100B blood level measurement to exclude cerebral lesions after minor head injury: the multicenter STIC-S100 French study

- NGAL, L-FABP, and KIM-1 in comparison to established markers of renal dysfunction

- Value-added reporting of antinuclear antibody testing by automated indirect immunofluorescence analysis

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- A fit-for-purpose approach to analytical sensitivity applied to a cardiac troponin assay: time to escape the ‘highly-sensitive’ trap

- Diabetes

- A simple and precise method for direct measurement of fractional esterification rate of high density lipoprotein cholesterol by high performance liquid chromatography

- Infectious Diseases

- Detection of unamplified HCV RNA in serum using a novel two metallic nanoparticle platform

- Increased plasma arginase activity in human sepsis: association with increased circulating neutrophils

- Corrigendum

- The relationship between estimated average glucose and fasting plasma glucose

- Letter to the Editors

- The obsessive-compulsory clinical pathologist

- Prism effect of specimen receiving – generation of fundamentals for the smooth progress of analytical processing

- Preanalytical errors: the professionals’ perspective

- Corrected reports in laboratory medicine in a Chinese university hospital for 3 years

- Comparison of an enzymatic assay with liquid chromatography-pulsed amperometric detection for the determination of lactulose and mannitol in urine of healthy subjects and patients with active celiac disease

- Effect of freezing-thawing process on neuron specific enolase concentration in severe traumatic brain injury sera samples

- Undetected creatinine levels

- The effect of centrifugation on three urine protein assays: benzethonium chloride, benzalkonium chloride and pyrogallol red