Abstract

‘Critical Translation in World and Comparative Literature’ outlines a theory of the ‘world work’ as constituted by the source text and all its translations simultaneously. The world work is brought into being by processes that Reynolds calls ‘prismatic translation’, and sees as arising from the interplay of what he calls ‘translationality’ and ‘Translation Rigidly Conceived’. The mode of existence of the world work poses particular challenges for the practice of world and comparative literary study: Reynolds proposes a theory of ‘critical translation’ to meet these challenges, and exemplifies it from the collaborative Prismatic Jane Eyre project.

Which language, or languages, should we employ for our work on comparative and world literatures and cultures? Well, English, obviously – at least for published writing: that is the stance of this new journal, Culture as Text, along with many other publications, academic institutions and university courses worldwide. It is the same in other disciplines and areas of life, from the sciences to business and popular culture, and the pros and cons have been well documented (Altbach 2007; Canagarajah 2002; Tupas 2013, 213–15). On the one hand, the ability to reach and interact with a wide, indeed a world, audience. On the other, the fact that this world is only a particular “world” – a structured arena with United States valuations, practices and points of reference at its centre. In academia, as Theresa Lillis and Mary Jane Curry have shown, journal rankings and impact factors exert a coercive influence, as they have consequences for funding and employment. Achieving high impact entails counting as “international”, and counting as “international” entails being in English: the international readerships that are in fact available in other world languages such as Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese or Swahili are ignored (Lillis and Curry 2010, 9, 18). In our discipline, or disciplines, of Comparative and World Literary and Cultural Studies, the stresses are especially acute. Linguistic and cultural diversity are a fundamental part of what we value and explore; and yet the language and culture that we ourselves embody and promote through our own writing are ever less diverse. What we study contradicts how we study it.

There is no point in rejecting the inevitable: this essay itself, composed almost entirely in standard English (and written from Oxford!) will be a ripe example of the paradox that it critiques. But perhaps it is worth trying to negotiate the terms on which we acquiesce in this self-contradiction. Write “in English” – OK: but what kind of English, with what borders, in what sort of interaction with other languages, generated via what social practices, received by whom and in what ways? I feel these questions nagging me when I consider even an admirable attempt at critical linguistic innovation such as A New Vocabulary for Global Modernism, edited by Erica Hayot and Rebecca L. Walkowitz (Columbia University Press, 2016). Prompted by “the field’s unprecedented expansion”, as “modernist studies now engages with aesthetic objects and expressive culture produced in spaces throughout the world”, the editors offer “a user’s manual … a set of instructions for entering into modernism from a global perspective” (1–2). A series of contributors present reflections on a variety of key critical words, from the expected (“tradition”) to the more quirky (“puppets”), and texts from a multitude of languages and locations are adduced. Nevertheless, I cannot help feeling some unease as I notice that every one of the terms in this “new vocabulary” is English, with all the essays being written in Standard English academic prose and following the familiar norms of the Anglo-American handbook essay. So this is not – and does not pretend to be – a new global vocabulary for global modernism, but is rather a new standard academic English vocabulary; and modernism is not in fact entered “from a global perspective” but rather from North America. Unsurprisingly, since all but one of the contributors are employed by universities in the United States, the implied reader, the one who is most imagined to need this “set of instructions”, is located in the North American academy; and though the book of course can be – and has been – read with profit by people in many different places, with a vast variety of linguistic repertoires, all readers will need to negotiate that interpellated subject position as they enter the book.

If these remarks are obvious – indeed, banal – it shows how far the critical practice I am describing has become the norm. To the many definitions of world literature that have been coined over the last two decades (Shi and Tan 2020, 15–16), should be added another, one so taken for granted that it is seldom or never articulated. World literature is literature written in any language, but written about in an English that obeys the norms of “international”, i.e., Anglo-American, academia. What we are looking at here, and what I am participating in as I write these words, is a vast structure of critical translation.

1 Critical Translation

To see literary-academic writing as translation is to spotlight various of its aspects. Which objects does it choose to focus on, and what kind of representation of them does it provide – or, in the idiom of Translation Studies, which source texts does it select, and what kind of re-writing does it subject them to? What kind of audience does it assume? – the “mythical English [or United States] reader” who has recently been subjected to critique by translators (Hahn et al. 2020; Hur 2022), or a diverse readership with plural linguistic repertoires – the “heterolingual address” envisaged by Sakai (1997, 1–17)? Above all, what kind of language is it using, and how? The old model of translation as operating between separate standard languages, and as subject to a double regime of correctness (correct meaning expressed in correct Standard English) has by now been thoroughly displaced, by the practice of translators as well as the arguments of theorists. Now, it is well recognised that translators draw on complex linguistic repertoires, and can change the target language as they use their creativity to mediate the source text to new readers. I will go into more detail about this shift in understanding below; for the moment, let me just assert that seeing all literary-academic work as translation enables similar developments to be envisaged for the critical language practices that characterise our field of comparative and world literary studies. Language is fluid and active: as A. L. Becker observed back in 1991, “there is no such thing as Language, only continual languaging, an activity of human beings in the world” (34; see Reynolds 2022, 144): so, the languaging of literary-academic writing (i.e., the languaging of critical translation) is open to change.

Scholars working with Arabic, Persian, ancient Egyptian, and Turkic languages provide an instructive example. Three decades ago, Wen-Chin Ouyang set out to overcome the “invisibility” of “medieval Arabic literary criticism”, making its terms again available for use (1997, 5); more recently, Rebecca Ruth Gould’s collaborative research project on “Global Literary Theory” has been excavating “the forgotten tradition of Islamic rhetoric (‘ilm al-balagha) for the contemporary study of literary form” (n.d.). Such terms can illuminate the close study of texts, as with Hany Rashwan’s demonstration that the Arabic rhetorical term “morphological jinās” (i.e., the employment of “two lexical items with the same morphological root but in different grammatical positions”) opens up an appreciation of the aesthetics of ancient Egyptian poetry (2021, 189). Non-English critical vocabulary can also introduce large-scale conceptual change, as when Mohamed-Salah Omri blends the Arabic “tarāfud” with its Latinate analogue, “confluence”, to articulate “an alternative comparative approach to the relationship between literatures”, explaining that “the root (r-f-d) refers to countless meanings, including: rāfid, tributary, which is a river that flows into another and amplifies it; tarfīd which is strengthening; and mirfād, pl. marāfid, in line with mighzār or midrār, which indicates a source of abundance and liquidity”, while “the Arabic meaning is stretched by adding the meaning of reciprocal flowing indicated by the word confluence’” (n.d., 1–2). If the mode of critical translation adopted by A New Vocabulary for Global Modernism is questionably subservient to the norms of standard academic English, these linguistically plural practices bid to change the critical vocabulary with which world literature can be described and understood. Perhaps, through such means as these, the metalanguage of world and comparative literary study might itself become a world and comparative metalanguage: a world vocabulary for world literature.

In what follows, I gather and present (at the invitation of Culture as Text’s editors) the theoretical gist of contributions I have made to comparative and world literature, and translation studies, in a variety of contexts, notably the volumes Translation: A Very Short Introduction (2016), Prismatic Translation (2019) and Prismatic Jane Eyre: Close-Reading a World Novel Across Languages (2023). I aim to summarise the theory that has been developed piecemeal through those books and, as I do so, to offer a fresh account of world literary works as co-existing in multiple translations, and a new definition of the critical practice that they invite: that is, of critical translation. The argument will develop through the explanation of some terms that I have either coined or stretched, so I will be making my own small contribution to extending the languaging of world and comparative literature (even though the terms in question derive from my own repertoire which is predominantly English and European). However, language and languaging are not only a matter of vocabulary, nor only vocabulary plus a grammar. They are, as Curry and Lillis emphasise, “social practice” (2010, 19), for, as Charles Taylor has put it, summarising the “constitutive-expressive” view of languages that he derives mainly from Herder and Wittgenstein, “a word only has meaning within a lexicon and a context of language practices, which are ultimately embedded in a form of life … To possess language is to be, and to be aware that one is, in social space” (2016, 17, 90). The question of what the linguistic medium of world and comparative literary study could be like, then, bears not only on words and syntax, but on the practices through which they are generated, and the readerships they aim to reach. As we will see, the view of the world work which I will outline enjoins a practice of critical translation that is, not only multilingual, and not only made freely available through websites and open-access publication, but also collaborative and multimodal, activating a plurality of critical perspectives in order to interpret a world work for a world of readers.

2 Prismatic Translation

Translation generates plurality: this is the core idea that the phrase prismatic translation was designed to capture. It is true of literature, where world classics such as 紅樓夢 (Dream of the Red Chamber) or Ἰλιάς (The Iliad) have become world classics through multiple translations; where a first translation of any text into a given language is likely to provoke further, rival translations into that language; and where, thanks to the mechanisms of international circulation, translation into one language also increases the chances of translation into others. It is true of international business, where products are “localised” in different languages for different markets, and of world politics, where treaties are made in parallel language versions. It is true of TV and film, where shows and movies that circulate transnationally are repeatedly re-dubbed or re-subtitled as appropriate. And it is true of any given translational situation, even that of a single translator faced with a single text, for any choice is made from a multitude of possibilities, and any translation, once finished, could immediately be done again, and done differently. So, what is often felt to be the default picture of translation – one text aligned with one other text – needs to be replaced by a picture of multiple texts jostling and interacting with one another, and the dominant metaphor of translation as it has traditionally been conceived – the channel – needs to give way to the prism (Reynolds 2019, 1–3).

When translation is reconceptualized in this way, the medium through which translation happens – language, or languages – needs to be seen differently too. The channel view of translation relies on a simplified and overly rigid view of language difference. It sees translation as operating across languages that are conceived as separate from one another, with the aim of achieving a relationship of meaning that can count as “equivalence”. Naoki Sakai has pointed out that this “representation of translation”, as he calls it, emerges from particular historical circumstances, and embodies a distinct, nationalist ideology:

The particular representation of translation as communication between two particular languages is no doubt a historical construct. Given the politico-social significance of translation, it is no accident that, historically, the regime of translation became widely accepted in many regions of the world, after the feudal order and its passive vassal subject gave way to the disciplinary order of the active citizen subject in the modern nation-state. (Sakai 2006, 76; see Reynolds 2019, 35)

This representation of translation downplays the continuities between signifying practices that have been politically constructed as belonging to “separate languages” – continuities that are very visible when what have been named as different languages are largely mutually intelligible, as with Hindi and Urdu, Bosnian, Serbian and Croatian, or Swedish, Danish and Norwegian. Clearly, translation between mutually intelligible languages cannot fundamentally be a matter of achieving intelligibility (though reading may be somewhat eased by such a translation, especially where different scripts are used, as with Urdu and Hindi). Rather, it is, at root, a matter of asserting difference, of presenting one text as being “in a different language” from another, very similar text, and thereby reinforcing the idea that we are looking at two separate languages rather than a continuum of difference.

In Translation: A Very Short Introduction (2016), I discussed the instance of the Dayton peace agreement, which came at the end of the violent breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Because Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia were establishing their new existence as nation-states, the treaty had to be produced in three, different and parallel language versions (plus English). Louise Askew, a member of the Language Service of the NATO-led multinational Stabilisation Force (SFOR), explains that “three very similar language versions” produced by translation “fed into the divisive ethnic politics in the country”, with translators “contributing to moulding the three standards”, i.e., to deciding what counted as belonging to one language rather than another, and how it should be written (Salama-Carr 2011, 106; see Reynolds 2016, 22). Translation creates and reinforces boundaries within language difference, which then turn into boundaries between what come to be seen as separate languages. Translation creates languages.

This aspect of translation is not confined to special cases such as the Dayton agreement. It is always present, wherever translation is practised. Historically, translation has always collaborated with other processes of standardisation, such as the writing of grammar books and dictionaries (monolingual and bilingual dictionaries are mutually dependent) and the teaching of a particular kind of language in schools. I call this mode of translation Translation Rigidly Conceived, for it tends always to impose a structure, collaborating with the division of language into languages, downplaying the diversity within what are then named as separate languages, and reinforcing the border between them (Reynolds 2016, 18–20). For Robert J. C. Young, in his account to the colonial workings of translation, this is the whole story of translation:

Translation can occur only if both languages have been made proper, have been standardized. Wedded to the written form, translation is sustained by the ideology of discrete unitary languages, assuming and requiring monolingualism, for without that separated distinction the conversion of one language into another would never take place – and would never be needed (Young 2016, 1218; see Reynolds 2019, 36).

However, as I see it, translation always also has a countervailing tendency, one that blurs and disrupts the structure for controlling difference that Translation Rigidly Conceived imposes and maintains. I call this translationality.

3 Translationality

It is always open to a translator to do something different, to alter the language that they are notionally working “in”. This can happen at the level of lexis, as with terms like “man’s-way-planning”, coined by Robert Browning to translate Aeschylus’s word “ανδρόβουλον”, or theory terms, such as the German Romantic “Zeitgeist” or Derridean “différance” that have been carried over into English usage from German and French unchanged in spelling, though of course their significance and connotations have shifted somewhat has they have found their bearings in new contexts of use (Reynolds 2013, 148, 132). It can happen at the level of grammar, as in the development of gender-specific pronouns in Chinese (“他” for “he”, “她” for “she”, and “它” for “it”) in response to translational involvement with European languages during the early- to mid-20th century (Huang 2023, 681–3). And it can happen at the level of idiom and style, flourishing especially in poetry. The collaborative volume Prismatic Translation (2019) is full of instances of writers dissolving boundaries and exploding standard forms in the course of translational processes, from Hsia Yu’s Pink Noise, discussed by Bruno (2019) to the “extreme translations” by Sawako Nakayasu, David Cameron, Christian Hawkey and Jody Gladding, explored by Jacobs (2019).

These anarchic modes are instances of what I call translationality, formed on the model of ‘fictionality’ and ‘theatricality’ (Reynolds 2016, 23). There have been a few appearances of this word in related literature in recent years. It can be found in medical writing, for instance Douglas Robinsons’s Translationality: Essays in the Translational-Medical Humanities (Routledge, 2019), where “translational medicine” means the development from basic scientific discoveries into medical applications; but the term also has a broader, linguistic use, pointing to the condition of being a translation, and to social issues around translation, as in Albuquerque’s (2019) article “Challenging Lusofonia: Transnationality, translationality, and appropriation in Tulio Carella’s Orgía/Orgia and Hermilo Borba Filho’s Deus no pasto”. As I use it, translationality names the whole range of re-makings of words in other words, both within what is conventionally defined as “a language” and across what are conventionally defined as separate languages. Translationality therefore moves across all kinds of language difference: of idiom, dialect, style, register, voice, and time, as well as of vocabulary and grammar. Whereas the term “intertextuality” points to many different sorts of connection, from allusion to mere contiguity, translationality focuses on the activity of re-making. Whereas Translation Rigidly Conceived downplays the differences within what are defined as separate languages, and reinforces the differences between them, translationality sees difference everywhere in language-use: from its point of view, language is a continuum of difference. All instances of language-use are actually or potentially engaged in translationality, and so translationality also names a quality that inheres in them. A text’s translationality lies in its traces of having been translated, and its disposition to be translated in its turn.

Translationality and Translation Rigidly Conceived (TRC) are in continual tension. According to TRC, translation happens between one language and another, separate one; it can achieve something that counts as equivalence; it can be right or wrong; and it can be finished. According to translationality, translation moves through language difference, breaking down the boundaries between what are named as separate languages, and relishing the variety that can be found within them; equivalence is never sufficient; differences are not errors, but sources of interest; and a translation is never finished, because any part of it can always be rephrased.

The tension varies with different texts and situations. With the translation of a legal document, TRC is likely to dominate, as the anarchic promptings of translationality are kept in check by a professional interpretive community. With a poetic translation of a poem, translationality is likely to be allowed freer rein, with TRC being present only in the claim that what is being written is, in some sense, a translation – i.e. that it has some sort of equivalence to the source text (Reynolds 2020, 133).

Observing the interplay of translationality and TRC enables us to reverse what are taken to be central and marginal in Translation Studies. Usually, poetic translation is seen as a limit case, a deviation from the norm of translation, translation “proper”. However, we can now see that translationality – free re-wording – is part of everyday language use, and poetic translation shares in that freedom. TRC, on the other hand, is a particular discipline superimposed on translationality, regulating meaning in the service of a regime of knowledge production associated with nation-states and their imperial expansion. This view tallies with the historical record, which shows TRC growing along with the development of European nation-states, and spreading worldwide in tandem with colonial and neo-colonial expansion. Translationality is part of the everyday ecology of language everywhere; TRC is a particular linguistic technology.

The interplay between translationality and TRC explains what I call the paradox of translation: that is, the fact that a translation is obviously different from another text (for instance, it is in a different language), while it is taken to be in at least some respects the same: for example, to have the same “meaning”, the same “function”, or the same “voice” (Reynolds 2019, 24). As we have seen, all translations combine some aspects of TRC with some degree of translationality. More specifically, while TRC advances the claim to sameness, translationality continually unravels it (“how about we rephrase it like this, or like this, or like this …”). When the paradox of translation is experienced by a human translator (or, less acutely, a reader of translations) it becomes what I call the agon of translation, to emphasise its conflictual, even painful nature. In the Prismatic Translation volume, I explore the cases of the English poet-translators Elizabeth Barrett Browning and John Dryden, in both of whom the desire to achieve sameness (the inevitable aim of all translation) collides with a recognition of the impossibility of doing so (the inevitable fate of all translation). When Barrett Browning was 24, she translated Aeschylus’s Προμηθεύς Δεσμωτής, Prometheus Bound, and felt “satisfied – tolerably satisfied” with her work. But a decade later her view had changed: “the recollection of this sin of mine, has been my nightmare” (Drummond 2004, 31; Prins 2017, 65; Reynolds 2019, 21). So, in line with the endless potential of translationality, she set about translating the play all over again. With Dryden, the desire and the recognition were in continual oscillation. The starkest instance is when, having spent many years of his life producing his Works of Virgil – one of the masterpieces of poetic translation into English – he wrote: “I have done great Wrong to Virgil in the whole Translation” (Dryden 1956–2000, vol. 5, 335; Reynolds 2019, 30). The interplay of TRC and translationality may be felt as an agon by an individual, but on a broader view it becomes one of the main motors of prismatic translation. The desire to achieve the definitive translation, together with the impossibility of doing so, means that ever more translations have to be produced.

4 Prismatic Translation Exemplified: The Case of Jane Eyre [1]

Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre, written in Yorkshire and first published in London in 1847, has been translated at least 618 times, into at least 68 languages, over an ever-increasing stretch of time (currently 176 years). That is to say, it has been re-written in different words by over 600 people, in different moments and places, with varying cultural and political commitments and concerns, in different publishing conditions, for different audiences (Reynolds et al. 2023, 11). Each of these translations finds something new in Jane Eyre, and makes something new of it: each translation changes what the novel is. Mutatis mutandis, the case of Jane Eyre is that of any literary text that has circulated widely through translation.

As we explore this enormous cloud of plural textuality, this extraordinary record of imaginative engagement, the interplay of translationality and Translation Rigidly Conceived can be seen at its generative work. A first translation is published (say, the first one into French, made by Paul Émile Daurand-Forgues, under the pseudonym “Old-Nick”, and published in a Paris newspaper in 1849), and its freedoms provoke a second, more literal version, by Noémi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, whose existence in turn prompts more and more translations into French, called into being as the language shifts, as the market calls for a new version, or simply as a translator or publisher feels that Jane Eyre should be translated again, and differently. The Old Nick version prompts further translations for another reason: it is abridged so as to be suited to serial publication. So, a Spanish translation of Old Nick’s French is printed in newspapers in Chile, Cuba and Bolivia; German and Swedish translations of Old Nick also swiftly appear (Reynolds et al. 2023, 28–38). The Lesbazeilles-Souvestre translation also nudges other translations to come into being, not only competing French ones but also (for example) the first translation into Italian, done by an anonymous translator or translators and published in Milan in 1904. This Italian translation draws mainly on Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, but also directly on Brontë, as it captures some of the prismatic linguistic possibilities released by the interplay of the English and French source texts (Reynolds et al. 2023, 60).

Elsewhere, we can see the agon of translation at work: in South Korea, Yu Jongho (유종호) translated Jane Eyre twice, in 1970 and 2004; and something similar happened in Croatia, where Giga Gračan and Andrijana Hjuit’s 1974 translation was modernized by Gračan in 2008 in response to alterations in the language following the country’s independence in 1991 (Reynolds et al. 2023, 60).[2] This is a stark instance of how the fluidity of language, its continual variability and change, generate translationality, and so nourish prismatic translation. What does it mean to translate a text “into Croatian” – or any language – if what counts as Croatian (or any named language) has permeable borders and is endlessly metamorphosing? Translationality also works across different media: new films and TV adaptations of Jane Eyre have prompted new translations as they have circulated worldwide. Other texts also flow into Jane Eyre translations via the workings of translationality: in Iran, in the late 20th century, as Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould show, the language and style of Persian romance, or “love literature” (adabiyāt-e ʿāsheqāna) appear in the translations (2023). In India, as Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishke Jain discovered, the representation of Mr. Rochester’s first wife, Bertha, in film adaptations and translations is influenced by the “ancient Indian trope of female madness present throughout centuries of classical Indian literature, with its prototype in Princess Ambā from the ancient Hindu epic Mahābhārata” (2023, 118). A contrasting source of prismatic creativity is censorship. Though it aims to restrict the translationality of any text, censorship can also provoke an anarchic inventiveness in translators. Andrés Claro describes this happening in the Spanish translation made, under Franco’s regime, by Juan de Luaces in 1943: Luaces is able to “write between the lines”, preserving the feminist political impulse which the censors endeavoured to repress (2023, 317).

As much work in Translation Studies has cumulatively shown, such metamorphic texts (which is to say, all translations) cannot satisfactorily be understood as deviations from an original that is left unchanged by their existence. Three decades ago, Charles Martindale argued that it makes no sense to ask whether a translator has reproduced what is “there” in the source, since “translations determine what counts as being ‘there’ in the first place” (1993, 93). Sakai has made a similar point: “what is translated and transferred can be recognized as such only after translation” (1997, 5). As Karen Emmerich has summed up this line of thought: “each translator creates her own original” (2017, 13). Let me provide a brief, small-scale example. In Chapter 1 of the novel the young Jane is attacked by her cousin John, and fights back. Adults appear and, as the two children are parted, Jane hears these words: “‘Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!’” What is “there” to be translated? What is a “picture of passion”? Different translators have seen different things. In the anonymous Italian translation of 1904, Jane is “una rabbiosa” (an angry girl). For Mécia and João Gaspar Simões in their Portugues translation of 1941, she is “um monstro” (a monster). In Vera Stanevich’s Russian (1950), Jane is showing “злоба” (“zloba” – “malice”), while in Tala Bar’s Hebrew (1986), the picture is “משולהבת” (“meshulhevet” – “ecstatic”) (Reynolds et al. 2023, 48–50).[3] Any or all of these alternatives may be an accurate representation of what Jane is like at this moment – in fact, they all must be, for they have conjured the picture into being by translating it.

The same is true of all other aspects of a text. Translations do not simply reproduce the “voice” or “tone” or “style” of the source text: they define what those intangible qualities are like. Even at the level of events, of what is “really going on” in a scene or story, translations invent as much as they transcribe. Jane Eyre can therefore no longer be understood as an English novel which translations try (and inevitably fail) to reproduce. It is, rather, an entity that coexists among all the different language versions, and is brought into being by all of them together, for a world of readers. I call this sort of entity a world work (Reynolds et al. 2023, 1, 11–91). The prismatic world work has a complex relationship to canonicity. On the one hand, Jane Eyre is obviously a canonical text, and the economic, political and cultural power of English has contributed to its propagation across languages. On the other hand, each new translation is a re-writing by another person who is usually little known (if not anonymous), and that person makes the novel their own, often abridging it, or shifting its genre or significance, and always leaving the marks of their own imagination. From this point of view, the prismatic translation of the novel is the opposite of a canonising process: it is an unruly unravelling and re-making of Brontë’s text, a release of plural imaginative energies, a massively collaborative venture in which hundreds of ordinary people find self-expression. Different scholarly approaches can make visible different aspects of this complex phenomenon. An approach that is uncritical about translation (for instance, one that conceives of translation as a pale imitation of the source) will see in the multilingual proliferation of Jane Eyres nothing but a symptom of the canonical power of Brontë’s work. But a critical translational approach will recognise the creativity that is, in one way or another, manifest in all translation, and will reveal the complex power dynamics that are in play around any act of translation. A critical translational approach to the prismatic world work will recognise its anti-canonical energies, and therefore aim to have a reparative effect.

5 Critical Translation and Jane Eyre as a World Work

How then should criticism approach a world work such as the world Jane Eyre? It is clear that criticism in this context (and, I would say, in any context) cannot be conceived as some sort of detached intellectual exercise that leaves the object of its attentions unchanged. Rather, like the translations I have mentioned (like all translations), it enters into the translationality of the world Jane Eyre, re-presenting it in a new context, and for new readings. So: it is critical translation. But what kind of critical translation?

The Prismatic Jane Eyre project adopted the following practices which, I suggest, could become principles for the critical translation of any world work.

Collaboration. In order to register the plurality of Jane Eyre as a world work, the process of critical translation had to be collaborative, and include many different language competencies. The volume, Prismatic Jane Eyre: Close-Reading a World Text Across Languages is therefore co-authored by many people as well as me: Andrés Claro, Annmarie Drury, Mary Frank, Paola Gaudio, Rebecca Ruth Gould, Jernej Habjan, Yunte Huang, Eugenia Kelbert, Ulrich Timme Kragh, Abhishek Jain, Ida Klitgård, Madli Kütt, Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos, Cláudia Pazos-Alonso, Eleni Philippou, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, Léa Rychen, Céline Sabiron, Kayvan Tahmasebian and Giovanni Pietro Vitali. Others again were involved in different aspects of the project (See Reynolds et al. 2023, vii–ix).

Collaboration also at the level of conceptualisation. To avoid funneling the plurality of the world Jane Eyre into a single explanatory point of view (which would inevitably be coercive and misrepresentative) our explanatory frames also had to be arrived at collaboratively, and to retain some multiplicity. So, many participants’ ideas fed into the metalanguage that I generated for the project; and, in the volume Prismatic Jane Eyre, that metalanguage is itself put in dialogue with others, developed by other co-authors. For example, Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain draw on Indian knowledge traditions to develop an alternative language for the phenomena that I point to with “prismatic translation”, “world work” and the other terms:

An anurūpaṇ (अनुरूपण adaptation) or anuvād (अनुवाद translation) is a pariṇāmī paryāy (परिणामी पर्याय transformed modality) derived from the dravya (द्रव्य substance) of a srot pāṭh (स्रोत पाठ source text) through dravyārthik samatulyatā (द्रव्यार्थिक समतुल्यता substantive equivalence) in a kathātmik vyākhyā (कथात्मिक व्याख्या narrative interpretation) instantiating a sāhityik prakār (साहित्यिक प्रकार literary type) (Kragh and Jain 2023, 146)

Kragh and Jain define a quality of Janeyreness that persists through the film adaptations and written versions and translations that they study (2023, 147). Though it was developed to describe the complex reception of Jane Eyre in India, this explanatory frame can equally be brought to bear in other contexts.

Multilingual close reading. If Jane Eyre as a world work inheres in all its translations together, then they should all be read together. Clearly, this is impossible: like other aspects of the project, it shows the necessity of principle vii below – “acceptance of incompleteness”. However, what we can do is read, not all, but many translations together, by selecting passages, key words and stylistic and grammatical features to focus on. In Prismatic Jane Eyre, participants chose the translations that interested them, and we agreed on the features to explore. One productive line of enquiry involved tracing key words – words like “plain”, “passion”, “slave”, “walk” and “wander” – as they recur throughout the text and its translations (also tracking related words as they form different patterns of significance in the different languages). Here is a snapshot of one instance of one such word, “passion”, as it appears in the scene I described above. Start from the English line that appears at the centre of this array, and let your eyes jump up and down between the successive translations (Reynolds et al. 2023, 48–50):[4]

D2015 hidsighed [hot-temperedness]

Por2011 Mas onde é que já se viu uma fúria destas?! [Have you ever seen such a fury?]

It2010 Si è mai vista una collera simile? [Did you ever see an anger like it?]

F2008 une telle image de la colère [such an image of anger]

K2004 꼴[{Kkol} face]

He1986 ראיתם פעם תמונה משולהבת כזאת [{ra’item pa’am temuna meshulhevet ka-zot} Did you ever see such an ecstatic picture?]

It1974 Si è mai vista una scena così pietosa? [Have you ever seen such a pitiful scene?]

F1964 semblable image de la passion! [similar image of passion!]

Sp1941 ¡Con cuánta rabia! [With so much rage!]

Por1951 Se já se viu uma coisa destas! … É uma ferazinha! [Have you ever seen a thing such as this one? … She’s a little beast!]

R1950 Этакая злоба у девочки! [{Ėtakaia zloba u devochki} What malice that child has!]

F1946 pareille image de la colère [such an image of anger]

Por1941 Onde é que já se viu um monstro destes?! [Have you ever seen a monster such as this one?]

F1919 pareille forcenée [such a mad person/a fury]

R1901 Видѣлъ-ли кто-нибудь подобное бѣшенное созданіе! [{Vidiel li kto-nibud’ podobnoe bieshennoye sozdaníe} Has anyone seen such a furious (lit. driven by rabies) creature!]

Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!

R1849 Кто бы могъ вообразить такую страшную картину! Она готова была растерзать и задушить бѣднаго мальчика! [{Kto by mog voobrazit’ takuiu strashnuiu kartinu! Ona gotova byla rasterzat’ i zadushit’ biednago mal’chika} Who could have imagined such a terrible sight/picture! She was ready to tear the poor boy apart and strangle him!]

It1904 Avete mai visto una rabbiosa come questa? [Have you ever seen a girl as angry as this one?]

Por1926 Já viu alguem tal accesso de loucura ! [Has anyone ever seen such a madness fit?]

He1946 הראה אדם מעולם התפרצות כגון זו? [{hera’e adam me-olam hitpartsut kegon zo} Has anyone ever seen an outburst like that one?]

Sp1947 ¿Habráse visto nunca semejante furia? [Have you ever seen such fury?]

It1951 Non s’è mai vista tanta prepotenza! [I’ve never seen such impertinence]

Sl1955 jeza [fury]

Sl1970 ihta [stubbornness]

A1985 "هل قدر لأي امرئ أن يرى مثل هذا الانفعال من قبل؟" [{hal quddira li ayy imriʾ an yarā mithla hadha al infiʿāl } Was anyone ever destined to see such a reaction]

R1998 Просто невообразимо, до чего она разъярилась! [{Prosto nevoobrazimo, do chego ona raz’’arilas’!} It simply passes imagination how furious she is]

He2007 ראיתם פעם פראות כזאת?! [{ra’item pa’am pir’ut ka-zot ?} Did you ever see such wildness?!]

Sp2009 -¡Habrase visto alguna vez rabia semejante! [Have you ever seen such rage!]

Pe2010 تا حالا چنین خشم و عصبانیتی از کسی ندیده بودیم [{tā hālā chunīn khashm va ʿasabāniyatī az kasī nadīda būdīm} We had not seen such a rage and anger]

T2011 སྨྱོན་མ་འདི་འདྲ་སུས་མཐོང་མྱོང་ཡོད་དམ [{smyon ma ’di ’dra sus mthong myong yod dam} Has anyone ever seen such a crazy woman?]

D2016 raseri [anger, wrath]

The back-translations give readers an idea of the senses that have been made of the word “passion”, here, in languages they do not know.

Multimodal presentation. The array shown above is perhaps hard to read, and certainly there is a tension between the static mode of presentation and the metamorphic translational energies that it is meant to illustrate. Print, with its attachment to standardization of grammar, spelling, punctuation and publisher’s style, has always been the ally of Translation Rigidly Conceived; on the other hand, speech, handwriting and animation are more supportive of translationality. So we also presented our explorations of verbal metamorphoses as animations: they can be found on Github (https://github.com/Prismatic-Jane-Eyre) and Oxford University’s Sustainable Digital Scholarship platform (https://www.sds.ox.ac.uk/home). In general, critical translation should be interested in the affordances of different media for providing new kinds of critical insight and experience.

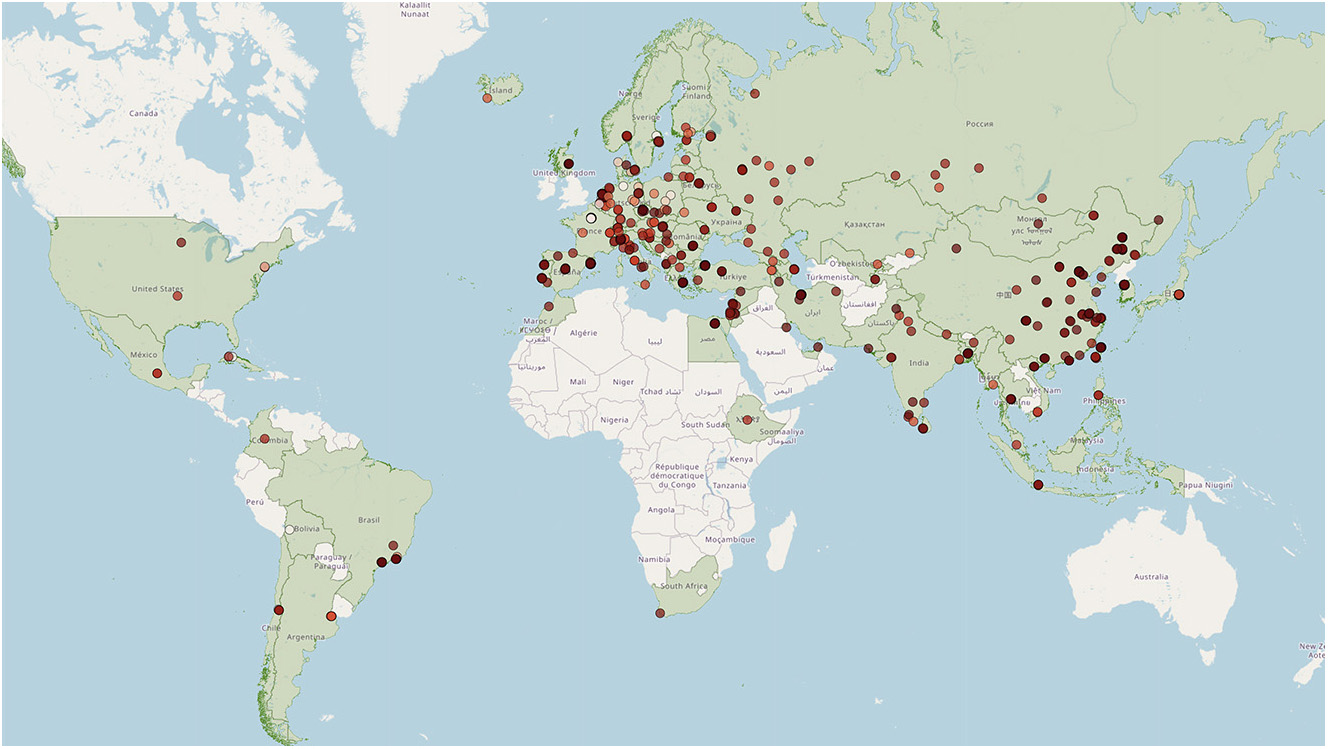

Interactive mapping. After we had searched for Jane Eyre translations, not only in the high-level (and quite unreliable) global databases such as WorldCat and Index Translationum, but also in national and local library catalogues, and bookshops, we assembled all the data into a spreadsheet which was useful but hard to read: so many lines, so many columns; so many hundreds of translations, by a plethora of different people and publishers, in so many moments and locations. So, led by the project’s Digital Humanities expert, Giovanni Pietro Vitali, we used the data to form interactive maps. Figure 1 is a zoomed-out screenshot of our simplest kind of map, the “General Map”: each dot shows the place of publication of a translation of Jane Eyre; the darker the dot, the more recent the publication. The impression this screenshot gives of the distribution of Jane Eyre translations is very partial, for many older dots are hidden by later ones; nevertheless, some significant facts can be seen, for instance the absence of Jane Eyre translations from most African countries, and the large number of translations in East Asia.

Prismatic Jane Eyre: the General Map, zoomed out to provide a snapshot of the global distribution of Jane Eyre translations. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali. © OpenStreetMap contributors. https://prismaticjaneeyre.org/maps/.

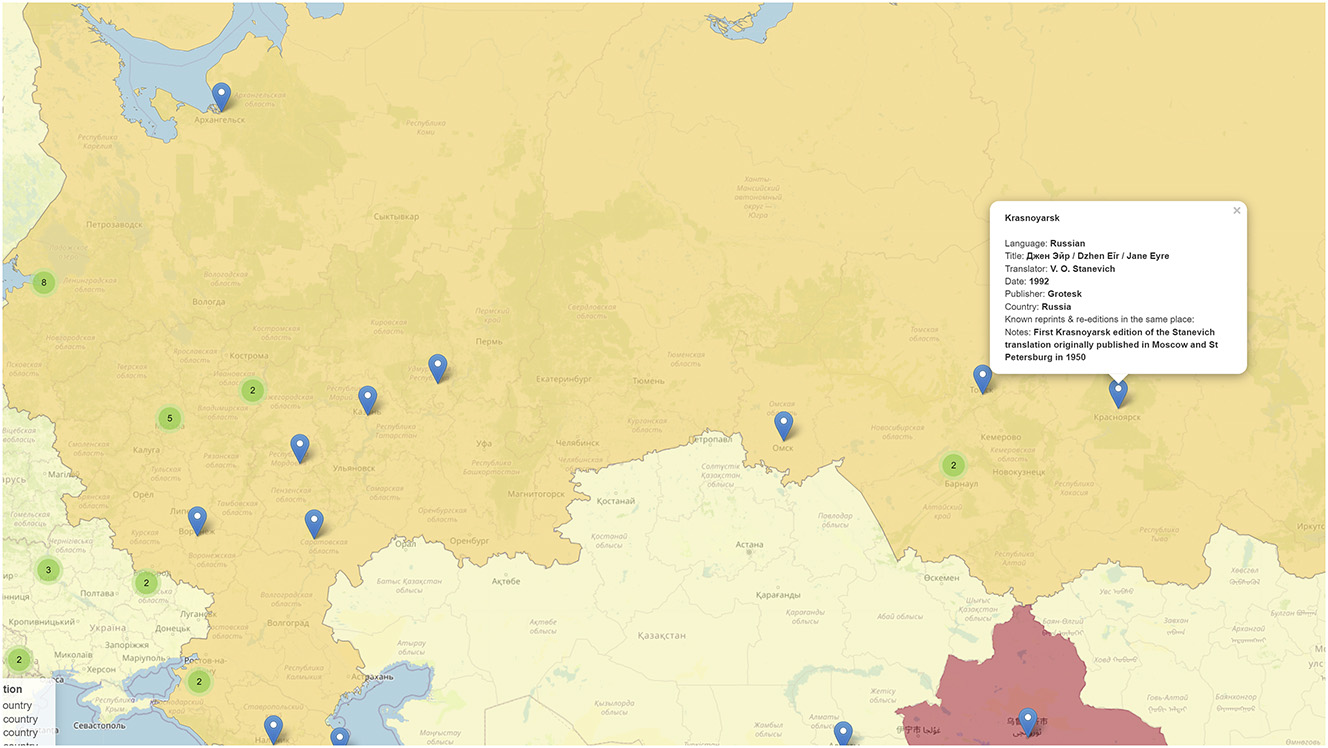

The maps enable us to move around and zoom in to investigate such phenomena. Figure 2 shows the same data in a different configuration, the “World Map”, zoomed in to show the 1992 Krasnoyarsk publication of a Russian translation by V. O. Stanevich.

Prismatic Jane Eyre: The World Map, zoomed in to show the 1992 publication of Stanevich’s 1950 Russian translation in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali. Maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors.

Creating maps allows us to see the data in new ways: it makes it legible, and thereby raises questions (for instance: why so many translations in East Asia? Why so few in Africa?) It also requires us to ask, what exactly counts as a translation for the purposes of a map? The Stanevich translation (researched by Eugenia Kelbert) was republished in many different locations across the Soviet Union: this, and other similar instances, led us to show on the map, not only the first publication of a given translation, but also its republication in different locations. We call both kinds of publication an “act of translation”, for republication in a different location continues the work of translation in its root, etymological sense (transfer to a new place), making the text available to new readers. As Franco Moretti was the first to show, maps can be a key part of critical translational practice (2013). Working with a variety of interactive maps avoids the problem – inherent to the static map – of enshrining a single world view.

Grounded, individual readings. In dialogue with the flexible and partial multilingual close readings of the world Jane Eyre, and with the mobile visualisations in the maps, participants wrote contributions to the volume focused on particular locations, languages and issues. Some have been mentioned above; among the others are Eleni Philippou discovering that the first translation in Greece was part of a British Council programme of Cold War cultural diplomacy (2023); Andrés Claro showing how translations of Jane Eyre entered into feminist and anti-colonial movements in South America in the mid-20th century (2023), and Madli Kütt showing how the distinctive grammar of Estonian, with its avoidance of first-person forms, leads to a more diffuse narratorial presence in the narrative (2023). As can be seen, the scope of the essays ranges from cultural history to close textual analysis, in accordance with the interests of their authors; and the same is true of the whole range of contributions in the open-access volume, whether they focus on Chinese, Portuguese, Arabic, Slovenian or the many other languages and contexts that are explored. This rooting of the project in the local follows the example set by Karima Laachir, Sara Marzagora and Francesca Orsini to foreground “subjectivity and positionality”, for the reason that “‘the world’”, in world literature, is “not a given but is produced by different, embodied and located actors” (2018, 94–5). Prismatic Jane Eyre adds one further point, drawn from the perspective of critical translation. The scholars doing the work of criticism are themselves positioned, and possessed of subjectivities, and construct different worlds accordingly, in collaboration with the material on which they work. A critical translational treatment of a world work therefore needs to embrace the different worlds projected by its participants.

Acceptance of incompleteness. Of the more than 600 translations of Jane Eyre, only perhaps 80 receive detailed discussion in Prismatic Jane Eyre; of the 68 or more languages in which Jane Eyre as a world work co-exists, only about 20 are treated at length in the volume. Even in the more encyclopaedic aspects of the project – the gathering of data, and the maps – there will no doubt be errors and omissions. And so it should be, for a fundamental aspect of world works such as Jane Eyre is that they are too large and varied to be grasped as an object of knowledge. The work of critical translation is, then, not only to enter into a world work from whatever points of view are available, and not only to articulate what is most salient from those points of view, but also to register the absent presence of what has not been articulated. The world work is larger than the critical translation of the world work; just as world literature is vaster than the study of world literature.

6 The Translationality of Critical Translation

World works pose challenges to scholarship and criticism. Defining what we do as critical translation gives us some ways of meeting those challenges. I have outlined my theory of the world work, and described the processes of critical translation that were developed in response to the case of the world Jane Eyre. To see how they turned out in practice, please go to the large, open access, collaborative volume Prismatic Jane Eyre: Close-Reading a World Novel Across Languages (2023). However, the point of this essay has been to make the theory of the world work, and the principles of critical translation, readily available to be re-used and re-made for other texts and contexts; that is, to be critically translated in their turn. To see what we do as critical translation is to place emphases on the kind of representation we offer of the texts that we discuss, on the range of readers and readings that our work is open to, and above all on our own languaging, including the collaborative or other processes through which it comes into being. It is to underline that comparative and world literature studies do not just research a world of languaging, they also create one. Through our practices of critical translation, we can determine what that world is like.

About the author

Matthew Reynolds is Professor of English and Comparative Criticism, University of Oxford, and a Tutorial Fellow of St Anne’s College.

References

Albuquerque, Severino J. 2019. “Challenging Lusofonia: Transnationality, Translationality, and Appropriation in Tulio Carella’s Orgía/Orgia and Hermilo Borba Filho’s Deus no pasto.” Journal of Lusophone Studies 4 (1): 186–207. https://doi.org/10.21471/jls.v4i1.304.Search in Google Scholar

Altbach, Philip G. 2007. “The Imperial Tongue: English as the Dominating Academic Language.” Economic and Political Weekly 42 (36): 3608–11.Search in Google Scholar

Becker, A. L. 1991. “Language and Languaging.” Language and Communication 11 (1): 33–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-5309(91)90013-l.Search in Google Scholar

Bruno, Cosima. 2019. “Translation Poetry: The Poetics of Noise in Hsia Yu’s Pink Noise.” Reynolds 2019: 173–89.10.2307/j.ctv16km05j.13Search in Google Scholar

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. 2002. A Geopolitics of Academic Writing. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.10.2307/j.ctt5hjn6cSearch in Google Scholar

Claro, Andrés. 2023. “Representation, Gender, Empire: Jane Eyre in Spanish.” Reynolds and Others 2023: 315–93.10.11647/obp.0319.09Search in Google Scholar

Drummond, Clara. 2004. “Two Translations of Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound by Elizabeth Barrett Browning.” PhD diss., Boston University School of Arts and Sciences.Search in Google Scholar

Dryden, John. 1956–2000. The Works, Vol. 20, edited by E. N. Hooker, H. T. Swedenberg, and Vinton A. Dearing. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Emmerich, Karen. 2017. Literary Translation and the Making of Originals. New York and London: Bloomsbury.10.5040/9781501329944Search in Google Scholar

Gould, Rebecca Ruth. n.d. “Global Literary Theory: The Project.” https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/lcahm/departments/languages/research/projects/globallit/project.aspx (accessed July 16, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Hahn, Daniel, Jen Wei Ting, Anton Hur, and Somrita Urni Ganguly. 2020. “Who is this Mythical English Reader?” National Centre for Writing. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J8oFttUu2bI (accessed September 29, 2020).Search in Google Scholar

Hayot, Eric, and Rebecca L. Walkowitz, eds. 2016. A New Vocabulary for Global Modernism. New York: Columbia University Press.10.7312/hayo16520Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Yunte. 2023. “Proper Nouns and Not So Proper Nouns: The Poetic Destiny of Jane Eyre in Chinese.” Reynolds 2023: 683–701.10.11647/obp.0319.19Search in Google Scholar

Hur, Anton. 2022. “The Mythical English Reader.” In Violent Phenomena: 21 Essays on Translation, edited by Kavita Bhanot, and Jeremy Tiang. London: Tilted Axis Press.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, Adriana X. 2019. “Extreme Translation.” Reynolds 2019: 156–72.10.2307/j.ctv16km05j.12Search in Google Scholar

Kragh, Ulrich Timme, and Abhishek Jain. 2023. “Jane, Come with Me to India: The Narrative Transformation of Janeeyreness in the Indian Reception of Jane Eyre.” Reynolds and Others 2023: 94–191.10.11647/obp.0319.04Search in Google Scholar

Kutt, Madli. 2023. “‘Beside Myself; or Rather Out of Myself’: First Person Presence in the Estonian Translation of Jane Eyre.” Reynolds and Others 2023: 797–827.10.11647/obp.0319.24Search in Google Scholar

Laachir, Karima, Sara Marzagora, and Francesca Orsini. 2018. “Significant Geographies: In Lieu of World Literature.” Journal of World Literature 3: 290–310. https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00303005.Search in Google Scholar

Lillis, Theresa, and Mary Jane Curry. 2010. Academic Writing in a Global Context: The Politics and Practices of Publishing in English. London and New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Martindale, Charles. 1993. Redeeming the Text: Latin Poetry and the Hermeneutics of Reception. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Moretti, Franco. 2013. Distant Reading. London: Verso.Search in Google Scholar

Omri, Mohamed-Salah. n.d. “Towards a Theory of Literary Tarāfud/Confluency: On the Poetics and Ethics of Comparison.” https://static1.squarespace.com/static/606065e8389f920b258d60fc/t/60a66658cc1bab2f8caad0eb/1621517917725/Trans.Tarafud+M-SO+Sep20EdietdOmriOct20.finalClean.pdf%5B46%5D.pdf (accessed July 16, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Ouyang, Wen-Chin. 1997. Literary Criticism in Medieval Arabic Islamic Culture: The Making of a Tradition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9781474471497Search in Google Scholar

Philippou, Eleni. 2023. “Commissioning Political Sympathies: The British Council’s Translation of Jane Eyre in Greece.” Reynolds and Others 2023: 395–425.10.11647/obp.0319.10Search in Google Scholar

Prins, Yopie. 2017. Ladies’ Greek: Victorian Translations of Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.23943/princeton/9780691141893.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Rashwan, Hany. 2021. “Against Eurocentrism: Decolonizing Eurocentric Literary Theories in the Ancient Egyptian and Arabic Poetics.” Howard Journal of Communications 32 (2): 171–96, 189. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2021.1879695.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Matthew. 2013. Likenesses: Translation, Illustration, Interpretation. Cambridge: Legenda.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Matthew. 2016. Translation: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/actrade/9780198712114.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Matthew, ed. 2019. Prismatic Translation. Cambridge: Legenda.10.2307/j.ctv16km05jSearch in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Matthew. 2020. “Prismatic Translation.” In Creative Multilingualism: A Manifesto, edited by Katrin Kohl, Rajinder Dudrah, Andrew Gosler, Suzanne Graham, Martin Maiden, Wen-Chin Ouyang, and Matthew Reynolds. Cambridge: Open Book.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Matthew. 2022. “Translanguaging Comparative Literature.” Recherche Littéraire/Literary Research 38: 141–53.Search in Google Scholar

Reynolds, Matthew, Andrés Claro, Annmarie Drury, Mary Frank, Paola Gaudio, Rebecca Ruth Gould, Jernej Habjan, et al.. 2023. Prismatic Jane Eyre: Close-Reading a World Novel Across Languages. Cambridge: Open Book.10.11647/OBP.0319Search in Google Scholar

Robinson, Douglas. 2019. Translationality: Essays in the Translational-Medical Humanities. London and New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Sakai, Naoki. 1997. Translation and Subjectivity: On “Japan” and Cultural Nationalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.Search in Google Scholar

Sakai, Naoki. 2006. “Translation.” Theory, Culture & Society 23 (2–3): 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276406063778.Search in Google Scholar

Salama-Carr, Myriam. 2011. “Interpreters in Conflict – The View from Within: An Interview With Louise Askew.” Translation Studies 4 (1): 103–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2011.528685.Search in Google Scholar

Shi, Flair Donglai, and Gareth Guangming Tan, eds. 2020. World Literature in Motion: Institution, Recognition, Location. Stuttgart: ibidem.Search in Google Scholar

Tahmasebian, Kayvan, and Rebecca Ruth Gould. 2023. “The Translatability of Love: The Romance Genre and the Prismatic Reception of Jane Eyre in Twentieth-Century Iran.” Reynolds and Others 2023: 451–91.10.11647/obp.0319.12Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, Charles. 2016. The Language Animal: The Full Shape of the Human Linguistic Capacity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674970250Search in Google Scholar

Tupas, T. Ruanni F. 2013. “Afterword: Crossing Cultures in an Unequal Global Order: Voicing and Agency in Academic Writing in English.” In Voices, Identities, Negotiations, and Conflicts: Writing Academic English Across Cultures, edited by Phan Le Ha, and Bradley Baurain Bingley, 213–20. Bingley: Emerald Group.10.1108/S1572-6304(2011)0000022015Search in Google Scholar

Young, Robert J. C. 2016. “That Which is Casually Called a Language.” PMLA 131 (5): 1207–21. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2016.131.5.1207.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter on behalf of Shanghai Jiao Tong University

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction

- Research Articles

- Is Decoloniality a New Turn in Postcolonialism?

- Critical Translation in World and Comparative Literature

- Cultural Studies, Big Data, Scalability: Benjamin Versus Bourdieu

- Europe in Literature

- The Internationalization of Left-Wing Terrorism and Counter-terrorism. The Role of the Past in Debates About Security and Liberty in Western Europe, 1968–1978

- Auschwitz Survivor and Nobel Prize of Peace, Élie Wiesel as Theologian

- Globalization and the Miracle of Shenzhen: From Localizing the Global to Globalizing the Local

- Miscellaneous

- Narrative, Imagination and Migration in the Southern Hemisphere: An Interview with Professor Elleke Boehmer

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Introduction

- Research Articles

- Is Decoloniality a New Turn in Postcolonialism?

- Critical Translation in World and Comparative Literature

- Cultural Studies, Big Data, Scalability: Benjamin Versus Bourdieu

- Europe in Literature

- The Internationalization of Left-Wing Terrorism and Counter-terrorism. The Role of the Past in Debates About Security and Liberty in Western Europe, 1968–1978

- Auschwitz Survivor and Nobel Prize of Peace, Élie Wiesel as Theologian

- Globalization and the Miracle of Shenzhen: From Localizing the Global to Globalizing the Local

- Miscellaneous

- Narrative, Imagination and Migration in the Southern Hemisphere: An Interview with Professor Elleke Boehmer